Equalities and Human Rights Committee

Age of Criminal Responsibility (Scotland) Bill Stage 1 Report

Executive Summary

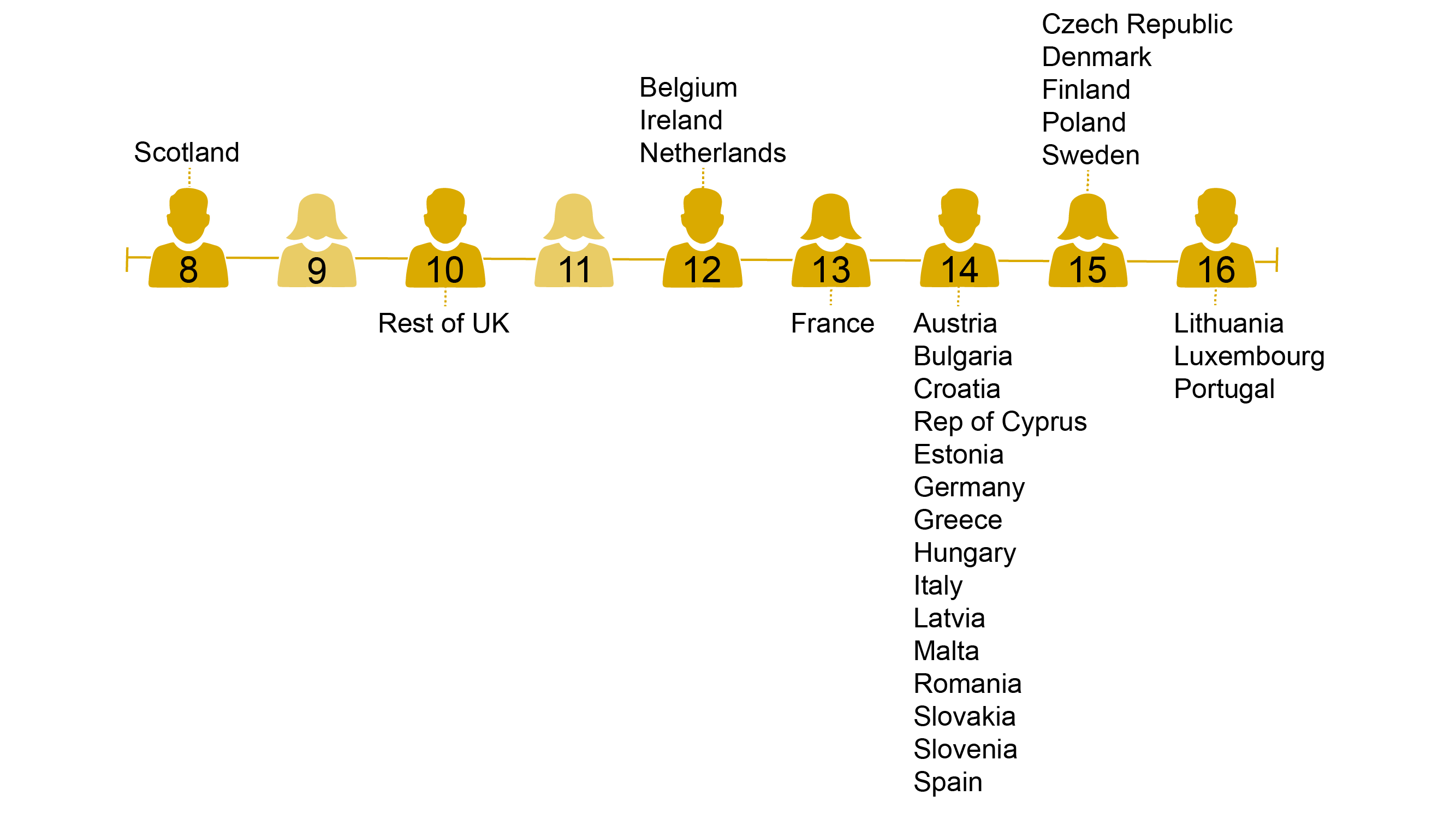

At eight years old, Scotland currently has the youngest age of criminal responsibility in Europe.

In 2010 the Criminal Justice and Licensing (Scotland) Act raised the minimum age of criminal prosecution in Scotland to 12. This meant that children under the age of 12 could no longer be prosecuted through the adult courts.

The disparity between the age of criminal responsibility and the age of criminal prosecution, however, meant that children aged eight-11 years could still obtain a conviction via a Children’s Hearing, either by admitting or having an offence ground established via a proof hearing at the Sheriff Court.

Any convictions gained at that age had the potential to appear on a higher level Disclosure check or PVG scheme record later in the child’s life, potentially preventing them from moving on from an incident in childhood or restricting their ability to undertake the training course or career of their choice.

Scotland has faced repeated criticism from human rights bodies, such as the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, for its low age of criminal responsibility. The UN Committee has suggested that 12 is the absolute minimum age that is internationally acceptable. It has urged states who have signed up to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, including the UK, to progressively increase this.

There have been repeated attempts to raise the age of criminal responsibility in Scotland, most recently via the Criminal Justice (Scotland) Bill (now 2016 Act). At the time, Michael Matheson, then Cabinet Secretary for Justice, suggested that in order to raise the age, there would need to be certainty around the Disclosure of criminal records, the use of forensic samples, police investigatory powers and the rights of victims.

In 2015, the Scottish Government announced the formation of a short-life Advisory Group to explore the implications of a potential increase in the age of criminal responsibility. The Advisory Group was comprised of representatives from a range of bodies, including the Crown Office Procurator Fiscal Service, youth justice bodies, victims’ organisations, children’s organisations and children’s rights bodies.

The Advisory Group published their report in February 2016. The report was published alongside a detailed Children’s Rights and Wellbeing Impact Assessment and research by the Scottish Children’s Reporter Administration, which examined the number and nature of offences for which children aged eight-11 years were currently being referred to the Children’s Reporter. A commitment to legislate to increase the age of criminal responsibility followed soon afterwards.

Following publication of the Advisory Group’s report, the Scottish Government issued a public consultation on raising the age of criminal responsibility to 12. Analysis of the consultation results found that found that 95% of those responding to the consultation favoured increasing the age of criminal responsibility to 12 or older.

The Age of Criminal Responsibility (Scotland) Bill was introduced to the Scottish Parliament on 13 March 2018. The Bill seeks to raise the age of criminal responsibility to 12; makes a number of provisions relating to police powers to investigate an incident of harmful behaviour by a child under 12; changes to Disclosure processes and the release of non-conviction information (known as ‘other relevant information’) for under 12s and information for victims of harmful behaviour. The Bill makes clear that no behaviour by a child under the age of 12 can be regarded as ‘criminal’.

We issued a call for evidence on 27 April 2018 and received 41 submissions. Thirty-nine responses commented on the age. There was, however, significant disagreement about where the new age of criminal responsibility should sit. Whilst all supported a move to a minimum 12 years old, others felt that the age needed to be set above 12, with various stakeholders recommending that it be set at 14, 16 or even 18 years old.

In our oral sessions, the majority of stakeholders queried whether a move to 12 was ‘progressive’ or likely to meet Scotland’s international human rights commitments (as suggested by the Bill’s Policy Memorandum). They pointed out that increasing the age to 12 would only achieve the minimum internationally acceptable age, as defined by the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child. Such a move would also only just lift Scotland off the bottom of the EU league table.

The Age of Criminal Responsibility (Scotland) Bill aims to right a wrong in the way that younger children in Scotland have been treated in the youth justice system in Scotland. The evidence of harm caused by treating children as ‘offenders’ from such a young age is clear.

The Edinburgh Study on Youth Transitions clearly demonstrates that involvement in formal processes doesn’t stop harmful behaviour, rather it is much more likely to lead to further harm. For those who manage to move on from early childhood behaviour, the current disparity between the age of criminal responsibility and the age of criminal prosecution has led to incidents in early childhood following them well into adulthood, in some cases severely restricting educational and employment opportunities.

We recognise that the approach taken by the Scottish Government towards this Bill is grounded in the desire to make significant improvements to the ways in which adults respond to younger children’s behaviour.

Where that behaviour is serious in nature and the harm caused to others is great, then the Bill seeks a balance between managing any risk that child might still pose with a better understanding of the reasons behind that behaviour. The Bill recognises that in addressing that trauma, the child has the best chance to move on from early behaviour and have the same chance to succeed as any other child.

This approach is evident throughout the Bill and is clear that much thought has gone into the way in which the Bill has been framed.

We struggled, however, to reach a shared view on whether 12 was a sufficiently high age to achieve the outcomes sought. Some Members felt that if a move to 12 years old could deliver significant improvements to children’s outcomes, then why should the same opportunities not be afforded to a young person of 14, 16 or even 18?

We also found it difficult to reconcile the desire to allow children to move on from early childhood behaviour with some of the police powers created in the Bill. We heard evidence from those who had experience of youth justice processes at a young age, who described feeling scared, confused and unable to understand what was going or unable to have their voice heard. As such we have sought further clarity in this area.

Whilst there are some investigative measures that clearly acknowledge the fact that these are young children, for example, the inclusion of an Advocacy Worker, there are issues in relation to where such interviews may be held and what constitutes a ‘child-friendly’ environment. We have asked for further detail on these provisions.

The Bill also seeks to ensure the child has a voice in proceedings. This is most welcome. However, we note that this is not applied consistently throughout the Bill. There are some circumstances in which there is a duty to explain to children what is happening in an age appropriate way and there are some circumstances where, even if the child has a right not to answer questions, the power imbalance between a police officer and a young child is likely to lead to that right being rarely exercised. We have highlighted the need for more guidance in this area. In addition, we have asked for information on the process to be in a child-friendly format and to take account of the needs of children with additional support needs, including speech, language and communication difficulties and hidden disabilities, such as autism.

In relation to our consideration of the ‘‘place of safety’’ provisions in the Bill, we believe that this has uncovered a much broader issue, in relation to the availability of suitable places throughout Scotland. Police Scotland indicated their estate simply wasn’t designed for children. We were concerned that the use of police cells, as ‘places of safety’ still occurred.

We heard distressing evidence from Lynzy Hanvidge, a care-experienced policy ambassador with Who Cares? Scotland, who was held in a police cell overnight at the age of 13. We were struck with the unfairness of her experience, where on the very night she was taken into care, she acquired her first police charge. We were impacted by her description of how her trauma had bred further trauma and that this Bill, as currently drafted, would not have avoided this situation because she was aged 13 years old.

We heard evidence that it is children who are most traumatised who are also the most likely to become involved in serious harmful behaviour. We also heard that children receiving support to address the root causes of that behaviour, which may be trauma-related, were significantly less likely to repeat those harmful behaviours.

As such, we believe that many of the investigative functions outlined in the Bill could be dealt with through existing child protection procedures and through welfare-based processes. This would ensure it was still possible to establish ‘the truth of the matter’, for example, via a Joint Investigative Interview, and it would still be possible to assess any ongoing risk the child might pose to themselves or others. However, the process would feel different and the focus would be on the needs of the child, rather on what that child was believed to have done.

If the premise is that a child under 12 cannot be held criminally responsible in Scotland, then they cannot be made to feel as if they are

In relation to search powers, we are mindful of the statutory Code of Practice on Stop and Search and the provisions made for children and young people in Chapter 7 of that code. We consider comprehensive guidance is required to take account of the powers under the Bill.

We recognise the Bill achieves significant progress in a number of areas. The focus on Disclosure, and in particular on non-conviction information (‘other relevant information’), is very welcome, as is the creation of the Independent Reviewer role. We also recognise the potential for the Disclosure principles in this Bill to be applied more widely to under 18s and warmly welcome this.

Raising the age of criminal responsibility in Scotland will bring benefits not just to children and young people, but to Scotland as a whole. It fits within Scotland’s wider context of being a trauma-informed nation, and recognises that dealing with the root causes of harmful behaviour supports the child to move on from harmful behaviour, but also lessens the odds of that behaviour being repeated.

We recognise that victims’ rights are fundamental to this whole process, but rather than taking rights away from victims, we see this Bill as an opportunity to think more widely about what is required and to put in place the right support at the right time.

We agreed with the general principles of the Bill.

Introduction

The Age of Criminal Responsibility (Scotland) Bill was introduced by the Deputy First Minister, John Swinney MSP to the Scottish Parliament on 13 March 2018. The Bill was referred to the Equalities and Human Rights Committee as lead committee for consideration. We are required to report to the Scottish Parliament on the general principles of the Bill.

Purpose of the Bill

The main purpose of the Bill is to raise the age of criminal responsibility in Scotland from eight to 12, to align it with the current minimum age of prosecution. Age of criminal responsibility is the age below which a child is deemed to lack capacity to commit a crime.

In policy terms the Bill’s objective is to better protect children from the harmful effects of early criminalisation, while ensuring that incidents of harmful behaviour by those aged under 12 can continue to be effectively investigated and responded to. Harmful behaviour involving children under 12 will continue to be fully investigated to find the facts of what happened and to ensure that victims and others affected by that behaviour continue to be protected.

The Policy Memorandum states that “Scotland’s current age of criminal responsibility (ACR), at age eight, is the lowest in Europe. With this Bill, all children in Scotland under 12 will know that they cannot be treated as a criminal who has committed an offence. They will no longer be left with a criminal record for any behaviour under that age".

In relation to the number of children and young people who will be affected by the Bill, the Policy Memorandum explains the context in which legislative change is being proposed and that the number of under 12s offending is “small and reducing”. Figures from Scottish Children’s Reporter Administration (SCRA)indicate around 204 children will be impacted by the Bill.

| Year | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of offence ground referrals for children aged eight to 11 | 212 | 213 | 210 | 204 |

Regarding the type of offending behaviour in this age group, the Policy Memorandum states it is “minor to moderate in nature and impact” and recognises the link between early offending and adverse childhood experiences, stating that a “disproportionate number of the under-12s currently dealt with for offending concerns have faced significant prior disadvantage and multiple adversity in early childhood”.

Legislative Background

A summary of how the law currently operates is noted below:

children under the age of eight - lack the legal capacity to commit an offence, cannot be prosecuted in the criminal courts and can only be referred to the children's hearings system on non-offence grounds

children aged between eight and 11 - cannot be prosecuted in the criminal courts but can be referred to the children's hearings system on both offence and non-offence grounds

children aged between 12 and 16 can be prosecuted in the criminal courts (subject to the guidance of the Lord Advocate) or referred to the children's hearings system on both offence and non-offence grounds

More detail on the legislation the Bill amends can be found in the Explanatory Notes which accompany the Bill.

Historical context and development of the policy approach

The current age of criminal responsibility was set by section 14 of the Children and Young Persons (Scotland) Act 1932.

Scottish Law Commission

The Scottish Law Commission undertook a review of the Age of Criminal Responsibility and laid its report before the Scottish Parliament on January 2002.

UN Committee on the Rights of the Child

In 2007, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child published their General Comment 10 on Children’s Rights in Juvenile Justice. This General Comment was designed to aid interpretation of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) and provide a clear steer in terms of how signatories to the Convention should approach offending behaviour by children.

In looking at the various ages of criminal responsibility in use by signatory countries, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child contrasted those with a ‘very low level of 7 or 8 years old’ with those with a ‘commendable high level of 14 or 16’. The General Comment also suggested that 12 should be the minimum internationally acceptable age of criminal responsibility.

Attempts to raise the age of criminal responsibility

Over the years there have been a number of attempts to raise the age of criminal responsibility. The most recent attempt to raise the age took place in 2015, when the Criminal Justice (Scotland) Bill (now 2016 Act) was progressing through the Scottish Parliament. An amendment was tabled by Alison McInnes MSP at Stage 2 of the Bill’s consideration. This proposed raising the age of criminal responsibility to 12 to bring it into line with the age of criminal prosecution. Then Cabinet Secretary for Justice, Michael Matheson, argued that raising the age of criminal responsibility was not straightforward and that “the minimum age of criminal responsibility is a substantial and complex issue”. He suggested that there were “significant underlying issues on the disclosure of criminal records, use of forensic samples, police investigatory powers and the rights of victims”. The Amendment was not agreed to.

The Cabinet Secretary subsequently announced the creation of an independent advisory group, the Minimum Age of Criminal Responsibility Advisory Group "the Advisory Group" tasked with examining “the underlying issues in respect of disclosure of criminal records, forensic samples, police investigatory powers, victims and community confidence taking account of the minimum age of prosecution, the role of the children's hearings system, and UNCRC compliance”.

A further amendment was tabled by Alison McInnes MSP at Stage 3 of the Bill. This was not agreed to, however, as there was a concern from some MSPs that it would pre-empt the findings of the Advisory Group.

Independent Advisory Group on the Minimum Age of Criminal Responsibility

The Independent Advisory Group on the Minimum Age of Criminal Responsibility was created in September 2015 and comprised of organisations working in the Crown Office Procurator Fiscal Service, the Scottish Children's Reporter Administration, bodies working in youth justice, children's organisations, victims’ organisations and children's rights groups.

The Advisory Group was tasked with looking at the areas previously set out by the Cabinet Secretary, with a particular focus on:

The way in which any ongoing risks posed by a younger child's harmful behaviour should be managed.

The implications of removing the ability to refer a child under the age of 12 on offence grounds to the Children's Hearings System.

The impact an increase in the age of criminal responsibility would have on Police Scotland's ability to investigate incidents and establish what had happened and who was responsible (even if their age meant that they were not held criminally responsible).

Changes required to the Disclosure system to allow younger children to move on from an incident of harmful behaviour. This also encompassed the weeding and retention of non-conviction information held by the police.i,

The Advisory Group published its report in March 2016 and made a number of key recommendations:

The Scottish Government and Scottish Parliament should take early action to raise the age of criminal responsibility to 12 years

Reform should mark a clear departure from the involvement of young children under 12 in criminal procedures or in disclosure systems

That there is appropriate and effective support available to those victims affected by harmful behaviour

That any non-conviction information relating to children under 12 at the time of an incident, which is, in exceptional circumstances, then submitted to the Police or other government bodies for inclusion on an Enhanced Disclosure or PVG Scheme Record, should undergo independent ratification before release

In the most serious circumstances, a power should be created to allow the police to take a child to a ‘‘place of safety’’, to allow enquiries to be made in relation to the child's needs, including where the support of a parent or carer is not forthcoming

In the most serious circumstances, a power should be created to allow for the interview of children, with appropriate safeguards, including where the support of a parent or carer is not forthcoming. Those safeguards should be based on the principles of Child Protection Procedures and Joint Investigative Interviews

That a power should be created to allow for forensic samples to be obtained in exceptional circumstances and to establish "the truth of the matter". This would allow a child to either prove their innocence or enable support to be put in place to prevent such harmful behaviour being repeated.

The report was published alongside a comprehensive Children's Rights and Wellbeing Impact Assessment and research from the Scottish Children's Reporter Administration (SCRA), examining the current behaviours of eight-11 year olds being referred to the Children's Reporter on offence grounds.

Immediately following the publication of the Advisory Group’s report, the Scottish Government issued a consultation asking if the age of criminal responsibility should be raised to 12. The consultation ran from March-June 2016. An analysis of consultation responses was published in December 2016vi.

This analysis found that 95% of those responding to the consultation favoured increasing the age of criminal responsibility to 12 or older.

Consideration of the Bill

The Bill is in five parts:

Part 1 deals with raising the age of criminal responsibility

Part 2 relates to disclosure of convictions and other information

Part 3 deals with the provision of information to victims

Part 4 relates to the investigatory and other powers of the police

Part 5 includes final provisions

This report covers the sections of the Bill which have provoked discussion during our consideration of the Bill. It does not therefore comment on all sections of the Bill. The report also sets out our conclusions and recommendations.

The costs associated with the Bill and the findings of the Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee have formed part of this Committee’s scrutiny of the Bill and are considered further below (see paragraphs 35-41).

Participation and engagement

We issued a call for evidence between 27 April and 6 July 2018. It sought views on the Bill’s provisions and gathered 41 written submissions. Submissions were received from local authorities including children's services and social work services, organisations representing looked-after children and other children-centred groups, advocacy services, victims, as well as equality and inclusion groups, the legal profession, the Police, the Children and Young People's Commissioner for Scotland, the Care Inspectorate and those involved with the Children's Hearing system, and a few individuals.

We took oral evidence from six panels of stakeholder witnesses and held a further panel with Maree Todd, Minister for Children and Young People, and her officials.

The evidence sessions took place on the following dates (key areas of discussion in brackets):

6 September 2018 (Children's Hearings, youth justice and the impact of current processes on children and young people)

20 September 2018 (Police powers, advocacy and victims’ rights)

27 September 2018 (Disclosure, children's rights and trauma-informed practice)

4 October 2018 (Minister for Children and Young People and officials)

Stakeholder engagement

To assist our considerations, it was important we engaged with a wide range of stakeholders, particularly children and young people and those who had experience of the youth justice system.

To increase participation, and to bring this topic to the attention of a broader section of young people, we developed an Age of Criminal Responsibility (Scotland) Bill toolkit, which was used as the basis of Parliament outreach school visits across Scotland and also widely publicised via social media to encourage teachers to hold a discussion on the topic. Schools said they really appreciated the opportunity to be involved in something real. Details of the schools participating and key findings arising from this work are included in Appendix A to this report.

In addition, we carried out a number of fact-finding visits to inform our work. These included visits to three secure accommodation units: Edinburgh Secure Services Howdenhall, Edinburgh; Kibble Group Secure Unit, Paisley; and St Mary’s Kenmure Secure Unit, Bishopbriggs; where we had an opportunity to speak with young people who had experience of the youth justice system. We would like to express our thanks to the young people who so candidly shared their difficult experiences, and their thoughts on how the system could be improved. We also spent time with the staff learning about their trauma‑informed approach to young people and the challenges of providing a secure accommodation service. We thank those who made these visits possible and provided valuable background to the issues we are considering.

Also, we are grateful to the Scottish Children’s Reporter Administration for facilitating our observations of Children’s Hearings and to the children and young people who consented to this. This brought to life the hearings process which supports child protection and youth justice.

Finally, we partnered with the Scottish Youth Parliament at their sitting in Kilmarnock in October 2018, to produce a workshop on disclosure and non‑conviction information. Again, we would like to thank the Members of the Youth Parliamentii who participated in this workshop and who contributed to our thinking in this area.

We would like to thank everyone who took the time to contribute to our consideration of the Bill, whether that was through written submissions, oral evidence, consultation events, visits or informal meetings. We recognise that this Bill has the potential to change many children’s lives and allow them to move on from incidents that would otherwise have negatively impacted upon their life chances for years to come.

Consideration by other Committees

Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee

In addition to our consideration of the Age of Criminal Responsibility (Scotland) Bill, the Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee (DPLRC) considered the Bill’s delegated powers on 15 May, 4 September and 11 September.

At its meeting on Tuesday 15 May, the DPLRC agreed to write to the Scottish Government to raise questions in relation to five of the delegated powers in the Bill.

The DPLRC subsequently produced a report with a series of recommendations which we note.

These recommendations focus primarily on section 19 of the Bill (in respect of how the functions of the Independent Reviewer role created by section 6 of the Bill can be modified) and section 67 (in respect of an omission to the ancillary powers of the Bill).

We note the findings of the DPLRC, which suggest that the regulation-making powers in section 19 of the Bill are currently too broad and ill-defined.

Additionally, we note the DPLRC recommendation to amend this section to ensure that the circumstances under which the Independent Reviewer’s remit can be changed are both limited and transparent.

As the Scottish Government has already indicated to the DPLRC their intention to bring forward an amendment at Stage 2 of the Bill’s consideration to address the concerns raised around ancillary powers, we note this commitment.

Finance and Constitution Committee

The Finance and Constitution Committee invited views until 18 June 2018 and received one submission, from the Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service (SCTS). The Committee agreed that it would give no further consideration to the Financial Memorandum.

SCTS provided the Bill team with costs set out in paragraph 22 of the Financial Memorandum on the understanding that the SCTS would “receive, at a later date, the full detail of the Bill in order to properly assess its financial impact.”.

An estimate of costs was provided by SCTS on the basis of uncontested civil application. This costing was caveated that it took no account of the increased costs to the SCTS should such applications become contested. On the new appeal to the sheriff under section 15 of the Bill or appeals under Part 4 of the Bill, SCTS advised they were not given the opportunity to provide cost estimates.

SCTS goes on to acknowledge, however, that given both applications and appeals (under Parts 2 and 4 of the Bill) are civil proceedings, SCTS are of the view that the Scottish Government’s policy of full cost recovery (including judicial costs) would apply and on this basis any additional costs to SCTS would be met through existing or amended court fees.

We note the concerns of SCTS and intend to make no further recommendations in this regard.

Financial Memorandum

We considered the figures provided in the Financial Memorandum accompanying the Bill.

We are generally content with the Financial Memorandum. However, we note that depending on the final approach taken to Advocacy Provision and "Places of safety", there may a financial impact at later amending stages of the Bill.

These are outlined in the relevant sections of this report:

Advocacy Provision:paragraphs 336-362

"Place of safety":paragraphs 270-298

Part 1 - Age of Criminal Responsibility

Part 1, sections 1 to 3, make provision for the age of criminal responsibility in Scotland to be raised to 12.

The Explanatory Notes which accompany the Bill explain that section 1 raises the age of criminal responsibility to 12 and, when taken together with sections 2 and 3, ensure that from the date new section 41 comes into force, no child will be prosecuted, or referred to a children's hearing on the basis of the offence ground in relation to pre-12 behaviour. This applies regardless of whether the child's behaviour occurred before or after the change in the age of criminal responsibility.ii

After new section 41 comes into force, where a child who is referred to a children's hearing, for behaviour that occurred while the child was aged eight to 11 and which would previously have constituted an offence, the child will not necessarily be dealt with any differently in terms of whether a compulsory supervision order is made (and, if so, the measures authorised by the order). The Explanatory Notes further explain that, “This is because, as already noted, the child's welfare is already the paramount consideration in determining what action should be taken in response to the child's behaviour, not the grounds on which the child is referred”.iii

Setting the age of criminal responsibility at 12

The Policy Memorandum states that the Scottish Government considered raising the age of criminal responsibility above 12, possibly to 14, but rejected this on the basis that “No child under 12 is currently responded to in the adversarial criminal justice system, or subject to punitive sanctions. Instead, they are responded to using a welfare based approach in the children's hearings system".

Thirty-nine out the 41 responses received to our call for evidence took a view on the age of criminal responsibility (ACR). Out of those 39, 15 respondents (roughly 38%) agreed that 12 was the appropriate age at which to set the ACR. A further 20 respondents (51%) agreed that the ACR should be raised to 12 for now, but with a view to considering increasing the ACR further in future. In summary, this indicates there was a desire amongst stakeholders to increase the age of criminal responsibility to 12 years old now with the majority of both written and oral contributors signalling a desire to go still further.

We noted that in the past Scotland's welfare-based system for dealing with youth justice issues was cited as a potential reason for any reluctance to increase the age. Malcom Schaffer of the Scottish Children's Reporter Administration believed “The children's hearing system has almost been getting in the way of looking at proper reform by lulling us into complacency. We have not recognised the sort of criminalisation effects that an appearance at a hearing for committing an offence can have, particularly in terms of disclosure.”ii

Inconsistencies in Scots Law

One of the reasons provided in the policy memorandum as to why 12 was an appropriate age was that age 12 already has significance in Scots law. For example, children aged 12 and over can make a will, and consent to or veto their own adoption. Also, children aged 12 or over were presumed to have sufficient understanding to express views on matters such as future arrangements for their own care in private law proceedings, to form a view to express at a children's hearing, and to instruct a solicitor.

Several submissions emphasised significant inconsistencies in the way in which children and young people are currently treated.

North Ayrshire Health and Social Care Partnership commented that “….legislation and government policies governing the rights of children is very muddled."

In relation to a child’s maturity, the Scottish Association of Social Work highlighted differing assumptions, stating that “…should the proposed MACR [minimum age of criminal responsibility] be enforced, a child of 12 can be charged and receive a criminal record at the age of 12, despite not being considered sufficiently mature enough to make decision about their sexual behaviour, or drink alcohol.”

While David Orrvi noted that Scotland’s approach towards children and young people meant that whilst some protections were extended to the age of 25vii, others assumed adulthood at 16viii, stating that “there is a wider and urgent debate required as to what is meant by a 'child' in numerous pieces of legislation. … There are legislative inconsistencies at present which have created a confusing picture.”ix

Pointing to a stark example, Dr Claire McDiarmid, Deputy Head of the School of Law at the University of Strathclyde, stated a child can be held criminally responsible for their actions before a court at the age of 12, whilst being considered insufficiently mature to sit as a juror in that same court until the age of 18.x

Age 12 and international human right standards

According to the Policy Memorandum, age 12 reflects “Scotland's progressive commitment to international human rights standards”. It also states that “Having the lowest ACR in Europe tarnishes Scotland's reputation internationally”. Raising the age of criminal responsibility to 12 would, the Memorandum said, give clearer effect to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) and responds positively to criticisms from the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child. The European Convention on Human Rights does not require a particular age of criminal responsibility to be set by member states, although the Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly, resolution recommended a minimum age of criminal responsibility of at least 14 years of age, while establishing a range of suitable alternatives to formal prosecution for younger offenders.

Scotland (as part of the UK) currently has the lowest age of criminal responsibility amongst European Union member states, with the rest of the UK (England, Wales and Northern Ireland) having a slightly higher age at 10. In fact, it is understood from the Children and Young Peoples Commissioner that it is the lowest age of criminal responsibility in the worldxv.

If, as the Bill proposes, the age of criminal responsibility is raised to 12, Scotland would have a higher age than the rest of the UK and would place Scotland at the same level as Belgium, Ireland and the Netherlands, but this would still be amongst the lowest in Europe.

Bruce Adamson, Children and Young People's Commissioner Scotland, referred to United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child consideration of the matter in 2007, which concluded “12 was the absolute minimum age acceptable in international law at that point”. He explained there was a danger in assuming that age 12 would still be considered acceptable today:

“It specifically said that no one should lower that age to 12, which was never intended as a target but the absolute minimum with immediate effect in 2007. Any country where the age was already 12 in 2007 needed to raise it progressively. Even 10 years ago, the committee said that a higher age of criminal responsibility—for instance, 14 or 16—contributes to a better juvenile justice system…I am very confused about why we are talking about 12."xvi

Professor Susan McVie, University of Edinburgh, questioned whether age 12 represented a progressive commitment to international human rights standards.xvii

Professor Elaine Sutherland, University of Stirling, considered it also important to look at article 40 of UNCRC, which “talks about how children ought to be treated when they come into contact with the criminal justice system” and “emphasises the importance of reintegrating the child into society”. She described the Bill as “positive” and “going in the right direction”.xvi

Maree Todd, Minister for Children and Young People (the Minister) emphasised that she was keen to hear views but it was her view that the age proposed was the right one, commenting:

“It is supported by the majority of respondents to our consultation and in the written evidence received by the committee. It is the age at which there is shared professional and public confidence in our proposals.”xix

Raising the age of criminal responsibility beyond 12

A key area raised in evidence was whether the age of 12 was high enough. This was closely followed by what age, beyond 12, should the age of criminal responsibility be set at.

Responses to our call for views showed that of the 39 responses, twenty (51%) respondents agreed that the ACR should be raised to 12 but with a view to considering increasing the ACR further in future, with a further 4 (10%) respondents stating that the ACR should be raised further by the Bill either to 16 or 18. This demonstrates 62% would like to see the age raised beyond 12.

Identifying an age higher than 12

Some stakeholders expressed frustration at what they perceived to be a lack of ambition by the Scottish Government in only raising the age to 12.

The Policy Memorandumi provides a table of ages of criminal responsibility currently in use across the EU. Based on the table, UK aside, fifteen countries have an ACR of 14, five at 15, three at 12 and 16, one at 13 This is reproduced below.

Duncan Dunlop, Chief Executive of Who Cares? Scotland, suggested that a move to 12 wasn't enough. He stated, “this is not making Scotland the best place in the world to grow up in; it is just about getting us on a par with the worst places in Europe”ii. Furthermore, he said “the involvement of the police and in fact – bizarrely – the justice system means that people are more likely to continue offending. We have to look at a different approach and we should seize this opportunity. The age of 12 is really nothing”ii.

Police Scotland suggested, however, that 12 was the most appropriate age, stating “whilst we understand the debate regarding setting the age of criminal responsibility at a higher age, we are mindful that the nature of children’s actions and the prevalence of that behaviour changes as the age group increases to 12 and above.” iv

Howard League Scotland (HLS) suggested that “the UN Committee makes the case that a MACR of 14 or 16 sits well with the UNCRC. While HLS welcomed the introduction of legislation to raise the minimum age in line with the current minimum age for prosecution, we urge the Scottish Parliament to adopt the higher age of at least 16, in the interests of promoting a forward-thinking and fair system of justice for young people in Scotland.”v

Malcolm Schaffer, Head of Practice and Policy at the Scottish Children’s Reporter Administration, suggested that increasing the age to 12, and bringing the age of criminal responsibility into line with the age of prosecution, was "an easy one to crack in terms of the legislative impact"vi. He went on to acknowledge, however, that an increase to 16 would be desirable, but that an increase to a higher age would require further work to "identify any potential gaps in powers"vii, including the need to think about "the implications for the case of somebody who commits a very serious and significant offence at the age of 15 years and 11 months. If the powers in the hearing system last only until the age of 18, but there is still a need for support after that, how will that support be provided?"viii

Bruce Adamson, the Children and Young People’s Commissioner Scotland drew attention to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child:

“Children are children up to the age of 18 and the question should not be how to justify raising the age from eight to 12, but how we justify treating children under 18 in a criminal manner. There may well be justifications, but the starting point for our discussions needs to be 18 and we need to be looking at 14 or 16 as the norm, internationally.”ix

Age of criminal responsibility international trends

Comparing progress internationally, Bruce Adamson, observed that “The dominant international trend in MACRs has been upwards. Between 1989 and 2008, 41 countries raised their MACR and 23 countries proposed to…”x

He went on to express concern that an increase to 12 would do little to improve the UK and devolved governments’ standing in an international human rights context, stating that “a MACR of 12 will bring Scotland ahead of only Switzerland, England, Wales and Northern Ireland, and in line with a small group of European countries, one of which is considering raising it to 14 years.xi The most common MACR in Europe is 14, while for the Nordic countries, the MACR is 15 years.”xii

In considering the approach to children and young people Juliet Harris, Together, advised Scotland to look at, countries such as Norway, Sweden and Iceland, which all have an age of criminal responsibility of 15.xiii

In response to the international evidence the Minister urged caution:

“When you look at other countries, it is clear that you cannot make direct comparisons between countries because the headline age does not capture the nuance. The age means different things in different countries. In Scotland, beyond the age of 12, the vast majority of children will continue to be dealt with by the children’s hearings system and not by the criminal justice system. That is vital to understand. Cultural context is also important. We will have the highest age of criminal responsibility within the United Kingdom.” xiv

She pointed to Luxembourg as an example, which had “a headline age of 18, but there are real idiosyncrasies in that...children who are under 16,… although they nominally have a criminal age of responsibility of 18, have to be dealt with in a youth court and the youth court can impose penal measures, including deprivation of liberty and solitary confinement for up to 10 days. There is no age limit on that. I therefore do not think that it is useful to look just at the headline age.”

Comparative studies of other countries approach

In 2016, to accompany the Advisory Group on the Minimum Age of Criminal Responsibility's report, the Centre for Youth and Criminal Justice produced a series of case studies exploring the ways in which other countries approached the minimum age of criminal responsibility. This included analysis of how the age operated in Germany, the Republic of Ireland, New Zealand, Portugal and Sweden.

These case studies set out how the age of criminal responsibility was applied in each country and what, exceptions, if any, were put in place to deal with seriously harmful behaviour.

More recent comparative data and analysis can also be found on the Child Rights International Network website.

Commenting on the international approaches, Professor Susan McVie, Chair of Quantitative Criminology of the School of Law at the University of Strathclyde, suggested it was unhelpful for countries to put in place exceptions to the minimum age of criminal responsibility to allow for very serious behaviour to be dealt with via an adult court. She suggested Scotland should take a different approach, stating “some countries put in place caveats on the age of criminal responsibility, but I think that is dangerous….If the principle is that we want to protect and support our young people, we have to accept that sometimes they do bad things, even though that is relatively rare.”xviii

Cognitive Development

We heard from a range of professionals that children’s brains often did not fully mature until much later in life, with full emotional maturity not being achieved until the late teens or even up to the age of 25.

North Ayrshire Health and Social Care Partnership suggested that “the way a child’s brain processes information is very different to that of an adult, with marked differences in their ability in areas such as social reasoning, self-control, problem-solving and consequential thinking”i.

Children 1st observed that “Not all children mature at the same rate and some understand and interpret consequences and processes differently to others.”ii

An example of this might be a child who pushes another child in anger. The child is likely to understand on a basic level that pushing another child is wrong. However, the consequences of such an action could range from the very minor (e.g. a scraped knee) up to the very serious (e.g. if the child falls and hits their head).

The Centre for Youth and Criminal Justice advised that “for children growing up in families and communities where others around them are engaged in criminal and harmful behaviours, it can be extremely difficult, if not impossible, for them to understand what criminal behaviour is and also to be able to exercise choice over what they do.”iii

Legal Defence on the basis of criminal incapacity

A small number of stakeholders considered there was merit in introducing a legal defence of criminal incapacity for children over the age of 12, but under 16 or 18 years old.

Dr Claire McDiarmid suggested that “One possible way….might be to make provision for a defence for young people aged over 12 but under a specified higher age (which could be 16, 18 or 25 depending on the criteria applied) to have a defence which they could plead to a criminal charge where they do lack criminal capacity….This has the advantage of allowing the certainty of an age of criminal responsibility alongside the provision of a safety net for those older young people who need, and merit, it.”iv

The Centre for Youth and Criminal Justice highlighted an example from Germany “which has an age of criminal responsibility of 14 but children between the ages of 14-18 can only be held responsible if they are “morally and mentally mature when the offence took place;…can realise the unlawfulness of his/her behaviour and act according to that realisation”,vi.

The Centre suggested that a similar set of provisions could be applied in Scotland and that “we believe that including these additional tests to the proposed legislation would be a sensible and just approach which takes into account the issues of free will; trauma, adversity and poverty; and brain development, maturity and understanding, as raised above".

Gerard Hart of Disclosure Scotland suggested, however, that such a test was unnecessary and that the way in which the Bill had been constructed did not rely on a capacity test, stating “the reasons for that are, first, that there may not be an easy way to agree on a test that could be scientifically validated and, secondly, that there would also be a difficulty with subjectivity, given the huge complexity of each individual child's story, their background and their behaviour”vii.

He went on to suggest that under the current arrangements for dealing with a child’s behaviour “the establishment of capacity, culpability and vulnerability is already done” and that any child appearing in front of a Children's Hearing will “already be subject to those protections”vii.

Participation and Protection Rights

Several stakeholders indicated that understanding the distinction between rights that are participation rights and those that are protection rights, was crucial in relation to how children and young people’s harmful behaviour was approached.

Bruce Adamson, the Children and Young People’s Commissioner Scotland explained that “the rights in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and the broader framework are often grouped into rights for survival, development, participation and protection. Participation and protection rights are really important. The idea is that, from a very young age, children have the right to be involved in decisions that affect them not just directly but at a societal level...i His written evidence stated that protection rights need to stay with children and young people until they are 18. The starting point is that a protection right, such as not being criminalised for actions, applies until 18, and the decision to lower that age needs justification.ii

The Centre for Youth and Criminal Justice also suggested that “it is entirely appropriate that as children mature they are given greater rights to exercise autonomy and make choices about their lives, so there needs to be a tiered approach” whilst acknowledging that “criminal responsibility, however, needs careful consideration, because holding a child solely, exclusively and criminally responsible can have long-term and profound consequences”iii.

Chris McCully of the Criminal Justice Voluntary Sector Forum, however, suggested “the fundamental basis of human rights is not what is politically acceptable, but what is right. After all, that is why they are called rights, and if you want to take them seriously, you enforce them, regardless of the political consensus”iv.

The Minister acknowledged that there were differing views on what the right age should be:

Our distinct children’s hearings system plays a critical role in addressing and responding to children’s behaviour. It provides a flexible, child-centred and welfare-based framework for exploring and addressing the harmful behaviours that some children and young people engage in. It is where decisions are taken to safeguard and promote the child’s welfare. The system focuses on the needs of children, whether they are perpetrators or victims with broader needs. the committee. It is the age at which there is shared professional and public confidence in our proposals.v

An incremental approach to raising the age

Several stakeholders expressed a desire to increase the age incrementally, and suggested a review mechanism would provide a means of doing so.

Claire Lightowler, Director, Centre for Youth and Criminal Justice, University of Strathclyde, was keen we explored ways to raise the age of criminal responsibility higher than 12, because “a child could grow up in a criminal family in a criminal community and they might be exploited. Serious organised crime groups target vulnerable children... A child can be sexually exploited and then be used to commit a range of drug offences. What are we doing when we hold children who are in those circumstances criminally responsible?”vi.

Professor Elaine E Sutherland considered 12 a compromise solution and that “rather than jeopardising what is undoubtedly progress, it may be prudent to accept raising the age to 12 for now. The matter can always be revisited in the future.”vii

Orkney Islands Council believed “there is a clear case to raise the age of criminal responsibility to 16 but that is some way off in terms of public support or political appetite to pursue given the challenges to get to 12 years.”viii

This view was shared by Detective Chief Superintendent Boal of Police Scotland who suggested “whether the age increases to 12 or higher, it has to be recognised and accepted that it must have societal buy-in”ix.

Community Justice Scotland suggested that ‘the ACR should be subject to review by Parliament within a designated period - on the basis of evidence – to access how appropriate the current ACR proposal is.”x

A similar view was expressed by Social Work Scotland, suggesting that “there should be a clause inserted into the Bill which would require a review of the legislation within 3 years with a view to incrementally raising the age until all children are afforded protected status in the criminal justice system.”xi

Maggie Mellon, Howard League Scotland, counselled against taking such an approach, stating “Scotland set the age of criminal responsibility at 8 in 1937. In 1964, Lord Kilbrandon said that there was no clinical evidence to suggest that that had made any sense at all: we were calling for the age to be higher in 1964. In considering review, the committee should bear it in mind that it might take 100 years for evidence to come back, despite there being lots of international evidence showing different thinking about the age of childhood and youth”xii.

The Minister said that “the UNCRC advises us to keep further reform in this area on the agenda and we definitely will. Future moves have to follow the evidence. We would need to be sure that the move to age 12 had worked well. The public would have to have confidence in what we are doing.”xiii

She was “very interested in hearing the committee's views on what would be a reasonable length of time for letting the system bed in and be tested and what we might need to monitor in the interim period so that we can have confidence about moving from the age of 12.”xiii

Conclusion on an incremental approach to raising the age

In considering this suggestion, we received no comprehensive details about how this would work in practice.

A review mechanism could, we understand, take one of several forms. We agreed that a review should take place, and that it should look at whether the legislation had improved outcomes for young people. Some Members felt this review should be used as an opportunity to increase the age of criminal responsibility still further. A review provision could set a timescale in the Bill for the issue to be revisited in future or it could cause the Bill to expire after a specified time period - forcing Parliament to revisit this. In the meantime, further work could be undertaken to examine the changes needed to make an increase beyond 12 a reality, in the same way the Advisory Group had looked at raising the age from eight-12 years. It is also noted a review could combine a number of these factors.

We consider there are inherent risks in pursuing the option of a review mechanism; for example, any review could overlap with the end of one Parliamentary session and the beginning of another.

Much of the work in identifying what a ‘non-criminalising’ approach towards harmful behaviour would look like in Scotland has already been done in the context of drafting this Bill. As such, we see no merit in repeating that exercise.

Conclusions on the age of criminal responsibility

From the Scottish Government’s consultation, our call for views, and some of our witnesses’ testimony, the age of criminal responsibility as set out in the Bill appears to be a publicly acceptable age.

We note the Scottish Government’s view that the Bill’s proposals have both “professional and public confidence”.

Whilst public opinion may be a factor in considering the age at which the age of criminal responsibility should be set, it should not, we believe, be the only driver for change. Welfare and the protection of the child should be paramount.

We heard evidence that children and young people who ended up in the youth criminal justice system had in most cases experienced trauma in their life. Once exposed to the criminal justice system, children tend to continue within it and move on to become part of the adult offending system. Professionals were clear having a trauma-informed approach rather than criminalising resulted in better outcomes for children and young people.

We recommend that, in future, the way in which any decisions are made about very serious harmful behaviours by all children, whether criminally responsible for their actions or not, must start from a need to approach this from a trauma-informed perspective. We ask the Scottish Government and other relevant public authorities to amend any supporting guidance and training materials to make this clear for all operational staff.

The Scottish Government argued that 12 is a good fit with the way in which Scotland approaches children and young people’s decision-making under the law e.g. instructing a solicitor or making a will. Evidence highlighted, however, a significant number of inconsistences in relation to the treatment of children under Scots law. In addition, these rights fall into the basket of participation rights, and not protection rights under the UNCRC which should follow a young person until they are 18. Some Members therefore feel this reasoning is not particularly robust.

We also know from our inquiry into Human Rights and the Scottish Parliament that work has started on an audit of the Scottish Government’s compliance with the UNCRC to assist in its commitment to incorporate children’s rights and that will, we expect uncover a number of inconsistences in the way children and young people are treated under Scots law.

We ask the Scottish Government, prior to Stage 1 debate on the Bill, for an indication of when this audit will be completed, whether the age of criminal responsibility will form part of this work, and the timescale for incorporating the UNCRC.

Work on incorporation of the UNCRC also raises an important issue around reconciling the age of criminal responsibility proposed in the Bill -12 - with international human rights standards. Article 1 of UNCRC states that a child is a child up to the age of 18. Given its commitment to incorporate UNCRC, we suggest it should be the benchmark by which the Scottish Government tests its new policy and legislative proposals.

While we also understand 12 would meet the minimum international standard, we also note the General Comment setting this standard was made in 2007 and the international direction of travel is upwards. Fifteen European countries have an age of criminal responsibility of 14. The minimum age of 12 would just put us on the ‘floor’ amongst other European countries - it is the de minimis position – and, some Members feel, this is out of step with the Scottish Government’s objective to be a fairer Scotland and to lead in human rights.

Allied to the points made above, we considered whether we are doing enough to protect our children and young people. As we outlined above, there is a clear distinction between children and young people’s participation rights and those that are protection rights. We refer in particular to Bruce Adamson’s comments, “Protection rights need to stay with children and young people until they are 18. The starting point is that a protection right, such as not being criminalised for actions, applies until 18, and the decision to lower that age needs justification.”i

The Minister said, “the bill represents a balanced, thoughtful and ambitious reform package for Scotland” ii. The Scottish Government argues age 12 is appropriate because it has public confidence, is a natural jumping-off point in childhood i.e. primary school age. This legislation and in its current form would assist only around 200 of Scotland's children each year.

Because the Advisory Group’s work was predicated on the impact on eight-11 years olds, we do not consider the Scottish Government focused sufficiently on exploring the options for setting a higher age of criminal responsibility, even though child development research, international precedent and international human rights standards support a higher age of criminal responsibility. Our evidence showed that research on developmental psychology shows development is at different rates in different children and that the necessary intellectual development to understand the consequences of their actions might not come through till the mid-teens. Therefore, the focus on pre-teens will not address this point.

We do recognise however, that much of the Advisory Group’s work in identifying what a ‘non-criminalising’ approach towards harmful behaviour would look like in Scotland has already been done in the context of drafting this Bill and some Members believe this could be extended to other age groups.

We heard evidence that there are significant reasons as to why the age of criminal responsibility should be higher than 12.

Some Members were therefore not convinced the Scottish Government has provided robust enough evidence to be confident there is sufficient justification to set the age as low as 12 and called into question whether the Bill as currently drafted is ambitious enough in human rights terms and for the protection of Scotland’s children

We wish to see progress on the protection of children and young people in Scotland, and so we agree with increasing the age of criminal responsibility to 12, as set out in the Bill.

Some Members, however, consider the Scottish Government has missed an opportunity to realise and protect the rights of more children and young people in Scotland by setting the new age of criminal responsibility at 12.

Children's Hearings

Section 3 of the Bill makes provision for the removal of the offence ground for all children under the age of 12 in a Children's Hearing. This means that in future, children's behaviour in that age group will only be able to be dealt with via a referral to the Children's Hearings system on care and protection grounds.

In 2016, The Scottish Children's Reporter Administration produced researchi which examined the circumstances surrounding children aged eight-11 years (i.e. above the current age of criminal responsibility, but below the age of criminal prosecution) being referred to a Children's Hearing on offence grounds.

The research looked at a sample of 100 children aged eight to 11 years old who were referred to the Reporter in 2013-14.

The report found that:

39% of children had disabilities and physical and/or mental health problems.

There were recorded concerns about educational achievement, attendance or behaviour in school for 53% of those children.

A quarter (25%) had been victims of physical and/or sexual abuse

75% had service involvement for at least a year, and over half had been involved with services for at least five years.

75% had previous referrals to the Reporter. Seventy children had been referred on non-offence grounds and five on offence grounds. Twenty-six children were on Compulsory Supervision Orders (CSO) at the time of the offence referral incident in 2013-14i.

The report therefore established a clear link between younger children’s welfare needs and harmful behaviour.

It was on the basis of this research, and on the recommendation of the Advisory Group, that a decision was made not to create a new ground for referral for children whose behaviour is currently dealt with via an offence ground.

This point was largely welcomed by those responding to our Call for Evidence, given that it clearly linked harmful behaviour with trauma occurring in a child’s life.

One concern raised with us related to how a move away from offence grounds would impact upon the burden of proof used to establish a child’s involvement in an incident.

Professor Elaine E. Sutherland explained that “Where non-offence grounds of referral are not accepted by the child or the relevant persons, establishing them before the sheriff requires proof on the balance of probabilities, rather than the higher criminal standard. That would be the case even if the substance of the allegation against the child related to harmful behaviour that would previously have been criminal. Thus, what would once have required proof beyond reasonable doubt in the past would only have to be established on the balance of probabilities under the proposed legislation.”iii

Furthermore, she stated that “since the disposal – what actually happens to the child – is decided on the basis of the child’s welfare, the difference in the standard of proof may not seem important. However, the substance of the proven allegations could be recorded and retained for the purpose of future disclosure. As a result the child’s (formerly criminal, now harmful) behaviour might follow him or her into adult life, being disclosed to a prospective employer without the child having the protection afforded to all other persons in respect of criminal conduct of having that conduct proved beyond reasonable doubt.”iv

Professor Sutherland suggested a potential solution to deal with this issue would be to create a new ground of referral. It could cover conduct that would have been criminal, but for the child’s age, and require proof beyond reasonable doubt in disputed cases. Such a ground for referral, could be:

the child has behaved in a manner which had they been twelve years of age or over which would require by law to be prosecuted on indictment or which are so serious as normally to give rise to solemn proceedings on the instructions of the Lord Advocate in the public interest.iii

In relation to the concern that a lesser standard of proof could impact on a child’s life chances through disclosure, Gerard Hart, Disclosure Scotland, provided assurance that the independent reviewer (see para 172) “will work to statutory guidance that ministers will produce, which will set out the parameters within which the role will be discharged”. He went on to say, “the independent reviewer will be a much faster way to get the matter sorted out. It will also allow us to provide guidance, which will help to make the process much clearer for everyone concerned” and that it “should be a guidance document that provides a wide range of advice”vi.

Simon Poutain, an Independent Monitor for the Disclosure and Barring Service, said “the list in the bill of people from whom the reviewer may request information is useful, because it includes not only the statutory partners—as happens in the parts of the country where I work—but “any other person” who is considered relevant, which could include the victim or medical teams and so on”vii.

Conclusion on children's hearings

We recognise that the change in the standard of proof is likely to have an impact on children aged eight-11 years old who might otherwise have been referred to a Children’s Hearing on offence grounds.

Also, we recognised that decisions about children under the current age of criminal responsibility (i.e. under eight years old), were already based on this civil standard of proof (as the child could not be found guilty of an offence).

Creation of an Independent Reviewer, would, we consider, guard against children aged eight-11 years having information about behaviour they denied included on a higher level Disclosure or PVG scheme record. On this basis, we do not feel it necessary to create a new ground for referral.

We consider there is merit in the Scottish Government considering carefully the issue of any change to the burden of proof in its wider work around the PVG review and Disclosure to ensure that children aged eight-11 are not negatively impacted by this change. We ask the Scottish Government to provide us with an assurance this issue will be included into its wider work in advance of the Stage 1 debate. Additionally, we ask the Scottish Government to provide an update on progress prior to Stage 2 consideration of the Bill

We recommend that when the Scottish Government creates the guidance for the Independent Reviewer that this change to the burden of proof is specifically referenced, and that the applicant’s right to make representations to the Independent Reviewer should be made explicit in accompanying guidance.

Part 2 - Disclosure of convictions and other relevant information rleating to time when a person is under 12

Part 2 of the Bill, sections 4 to 21, deals with issues around the disclosure of information relating to a child’s convictions and behaviour when they were under the age of 12.

In the Explanatory Notes accompanying the Bill, it is states that “Section 4 of the Bill changes the position in relation to convictions acquired prior to the change in the age of criminal responsibility. It amends the definition of “conviction” in sections 112 and 113A of the 1997 Act so as to exclude convictions for offences committed whilst a person was aged eight to 11”ii.

The effect of this is that the provisions in this Bill will apply retrospectively, i.e. that any conviction information relating to children aged eight-11 years at the time of the offence (whether before or after the provisions of this Bill comes into effect), can no longer be described as a ‘conviction’ and cannot be disclosed via a higher level Disclosure or PVG Scheme Record.”iii

Section 5 of the Bill still makes provision, however, for the release of non-conviction information (other relevant information) relating to behaviour under the age of 12. This provision is only to be used in exceptional circumstances and safeguards have been put in place to ensure that this is the case (these are explained in the section headed ‘Independent Reviewer’).

ORI (‘other relevant information’) – current processes

At present, the discretion to include such non-conviction information, known as ‘other relevant information’ or ‘ORI’ on a person's higher level Disclosure certificate or PVG Scheme Record lies with the Chief Constable of Police Scotland.

Gerard Hart of Disclosure Scotland provided a definition of ORI as “a paragraph of text that can relate to matters that never went to court and were not tested in that way but which the chief constable reasonably believes to be pertinent to the kind of work that the individual is seeking to do or the vulnerable group that the individual is seeking to work with. That could happen with an enhanced disclosure in relation to a specific post, or with a protection of vulnerable groups disclosure in relation a whole vulnerable group—children or protected adults.”i

The key difficulties identified with the current system is that children are often not aware that this information is being recorded at the time or what the likely implications of that might be. ORI can sometimes be recorded without context, making it difficult to assess if there is any ongoing risk and, whilst the information may be weeded out from Police Scotland’s systems over time, there is still the potential for it to be held indefinitely. There is also no clear process in place to allow a person to challenge the inclusion of such information or its relevancy to the training or employment opportunity they may be seeking to undertake.

The Advisory Group on the Minimum Age of Criminal Responsibility recommended that "there should be a strong presumption against the Police including non-conviction information on disclosures about conduct that occurred under the age of 12." It further recommended that in future, ORI relating to behaviour under the age of 12 "ought to occur only when absolutely necessary for public protection and should be subject to independent ratification by a party other than the Chief Constable before disclosure takes place."

Bruce Adamson, Children and Young People’s Commissioner Scotland, suggested that weeding and retention processes also required to be more closely examined stating. “In order to fully understand the rights implications and the proportionality of these measures, there needs to be greater clarity around what is recorded as ORI and how long it will be retained for. There is a need for clear guidance and rules to govern practice in this area, and there should be a strong presumption that information should be recorded and retained about children under 12 only where there is a clear welfare/best interest rationale for doing so.”v

It is important to note that the provisions of the Bill do not prevent the recording of information by Police Scotland, but rather its release.

Disclosure of information relating to under-12s

We understand recent legislative changes have impacted on the number of people having information disclosed about their behaviour under the age of 12.

Gerard Hart of Disclosure Scotland, advised the PVG review consultation has just closed and that “the proposals would free most children, most of the time, from the longitudinal consequences of disclosure of their criminal record”i

Gerard Hart also stated that "in 2016 and 2017, in the whole of Scotland, there were fewer than five cases in which conduct by children under the age of 12 was the subject of disclosure at a later date. In 2014 and 2015, the figures were 53 and 27, respectively. The reason for that drop was that the Government introduced the Police Act 1997 and the Protection of Vulnerable Groups (Scotland) Act 2007 Remedial Order 2015, which introduced a rules list, an always list and new protections, particularly for young people, by getting rid of minor and trivial matters from subsequent disclosure".ii

Police Scotland suggested that "it should be noted that Police Scotland’s analysis has revealed that there have been no disclosures or cases for those under 12". iii

In examining the provisions in Part 2 of the Bill, we noted the Advisory Group’s recommendation that any person independently verifying a decision to release information relating to under 12s, should also have a role in ensuring that young people under the age of 18 could move on from childhood behaviour.

As such, we welcome the Scottish Government’s commitment to consider this further via the Management of Offenders (Scotland) Bill (which is being considered at Stage 1 by the Justice Committee) and in relation to the review of the Protection of Vulnerable Groups (PVG) scheme, which has just been consulted on.iv

We ask that the Scottish Government to provide us with a progress update in relation to both the Management of Offenders (Scotland) Bill and the review of the Protection of Vulnerable Groups (PVG) scheme, prior to Stage 2 consideration of the Bill.

Independent Reviewer

As previously stated, currently the decision about whether to release non-conviction information relating to a child’s behaviour under the age of 12 lies with the Chief Constable of Police Scotland.

However, the Advisory Group on the Minimum Age of Criminal Responsibility recommended in their report that, in order to ensure that such information was released only exceptionally, it should be independently verified by another person before doing so.

This process of independent verification will create a new role of Independent Reviewer in Scotland. Sections 6 to 8 of the Bill provide for the appointment of an independent reviewer.

Provisions relating to functions of the independent reviewer are set out in sections 9 to 19, with the process for review covered in sections 9 to 15. The independent reviewer will be able to seek information from a range of people about the child’s (or young person’s or adult’s - depending on when a higher level Disclosure certificate or PVG scheme record was sought) current circumstances, allowing the applicant to make representations and for an accurate assessment of future risk to be formed, before any decision is taken whether to release information.

The concept of independent verification for these purposes is new in Scotland. However, the role has been modelled on the existing roles of Independent Monitor in England and Wales and the Independent Reviewer in Northern Ireland (who have, until recently, been the same person).

Whilst the remits in other jurisdictions may vary from that envisaged for the Independent Reviewer in Scotland, the basic principle behind them is the same. That is, that a person’s childhood behaviour should not negatively impact on their future life chances, save for in a very few exceptional cases, for example, where a child’s behaviour might pose a continuous risk either to themselves or to the wider public.

Simon Pountain, who was then both the Independent Monitor for England and Wales and the Independent Reviewer in Northern Ireland, explained how his work impacted upon children and young people. A lot of the work in Northern Ireland, he explained, involved people around the ages of 13, 14 and 15 who were in care and offended over a short period, but who have not offended since. Cases arose when those people applied to work with vulnerable groups later in life. He considered whether the information was relevant on the basis of whether the removal of the information would impact on the safeguarding of vulnerable people. If it would not, then the information should be removed.ii

Simon Pountain said that in many cases the way in which an incident is presented can sometimes be misleading. He gave an example, “an algorithm might determine that certain offences are so serious that they need to be disclosed but, under sexual offences, there could be indecent behaviour and, although the title of that offence sounds like it should be disclosed, it could cover something as simple as urinating in the street, which might not be relevant to the work that someone is applying for. Objectively looking at the issue rather than just looking at the title of the offence could work when we consider children between different ages”iii.

He went on to explain that in Northern Ireland 87% of the offences that he saw were deleted from the criminal records.iv

The role that the Bill envisages for the Independent Reviewer in Scotland for children under the age of criminal responsibility will differ from the roles in England, Wales and Northern Ireland in that it will require the Reviewer to decide whether the inclusion of non-conviction information relating to an incident before the age of 12 on a higher level Disclosure or PVG scheme record is appropriate, before that information is released.

What that means in practice is that if the Independent Reviewer in Scotland finds that a piece of information should not be disclosed for a particular purposev then it will not enter the public domainvi. For example, it will not be disclosed to educational establishments or potential employers and the person will be able to move on from that behaviour with the same options and opportunities available to them as if the behaviour had never happened.

In England, Wales and Northern Ireland, the information about childhood behaviour and convictions may already have appeared on a person’s record and the appeal to the Independent Monitor or Independent Reviewer usually relates to a request to remove such information from a person’s record. This might be, for example, where it was an isolated incident or where a substantial period has passed since it took place.