Right to Addiction Recovery (Scotland) Bill

The Right to Addiction Recovery (Scotland) Bill aims to establish a right for people diagnosed with a drug and/or alcohol addiction to receive a treatment determination and treatment. The Bill would also allow people diagnosed as having a drug and/or alcohol addiction to participate in the decision making about their treatment. This briefing outlines the proposals in the Bill and a summary of the views expressed in the written evidence received by the Health and Sport Committee.

Summary

The Right to Addiction Recovery (Scotland) Bill is a Member's Bill which was introduced in the Scottish Parliament, on 15 May 2024, by Douglas Ross MSP.

Alongside the Bill and Explanatory Notes a Policy Memorandum, a Financial Memorandum, a Delegated Powers Memorandum and a Statement of Legislative Competence were published. An Equality Impact Assessment was also published.

In Scotland, there are long-standing and serious issues associated with drug and alcohol use. Furthermore, these problems are concentrated in the most deprived communities, where health inequalities and social exclusion impact on the experience of people and access to services 1.

The Bill seeks to give people diagnosed as having a drug or alcohol addiction, by a relevant professional, a right to receive a treatment determination and be provided with treatment, as soon as is practicable, and within three weeks at most2.

The Policy Memorandum states:

The Bill will give people diagnosed as having an addiction to alcohol and/or drugs access to the treatment that is most appropriate for them, and enable them to be informed and supported and involved in the decision making process.

The Health, Social Care and Sport Committee launched its call for views on the Bill on 01 November 2024 and it closed on 20 December 2024. 122 responses were received by the deadline.

The key themes raised in the written evidence focused around:

Scope and extent of the Bill

Person centred approach

Clinical decision making

Harm reduction and absence based treatment

Access to services

Unintended consequences

Implementation and enforcement

Standards and regulation of services

Drafting suggestions

Financial implications

The Health, Social Care and Sport Committee has also held an informal session with individuals with lived or living experience of substance use in conjunction with a number of third sector partners. The Committee will continue its scrutiny of the Bill by taking oral evidence from professional and stakeholder groups, the Minister for Drugs and Alcohol Policy, and Douglas Ross MSP (the Member in Charge), before publishing its Stage 1 Report. More information is available on the Committee's webpageand the Bill page on the Scottish Parliament's website.

Introduction

The Right to Addiction Recovery (Scotland) Bill is a Member's Bill which was introduced in the Scottish Parliament, on 14 May 2024, by Douglas Ross MSP. Annie Wells MSP is the additional member in charge. The Bill, as introduced, seeks to make provision about the rights of persons addicted to drugs and/or alcohol to receive treatment for addiction. The Explanatory Notes state:

The Bill provides for a right for anyone diagnosed as having a drug and/or alcohol addiction to receive a treatment determination and for the person to be provided with that treatment as soon as reasonably practicable and no later than three weeks from the date of the determination.

The Bill provides that the Scottish Ministers must secure the delivery of all of these rights and obliges them to make regulations setting out how they will fulfil that duty. In doing so, it gives the Scottish Ministers the power to confer functions on health boards, special health boards, the Common Services Agency [also known as NHS National Services Scotland (NSS)], local authorities and integration joint boards.

The Bill also requires the Scottish Ministers to prepare a code of practice to go alongside these regulations.

The Bill enables a person who has been diagnosed as having a drug and/or alcohol addiction to participate in the decision-making process about their treatment [...] The Bill also requires the Scottish Ministers to report annually to the Parliament on progress made towards achieving the provision of the treatments under this Bill.

The Bill requires the Scottish Ministers, before preparing a report, to consult representatives of patients and people with lived experience of drug and/or alcohol addiction, as well as health boards, special health boards, the Common Services Agency, local authorities and integration joint boards.

Alongside the Bill and Explanatory Notes a Policy Memorandum, a Financial Memorandum, a Delegated Powers Memorandum and a Statement of Legislative Competence were published. An Equality Impact Assessment was also published.

Prior to the Bill being introduced in Parliament, Douglas Ross MSP undertook a consultation on a proposal for a Bill to give those addicted to drugs and/or alcohol the right to access the necessary addiction treatment they require. This received 195 responses and a Consultation Summary was published.

Current situation

In Scotland, there are long-standing and serious issues associated with drug and alcohol use. Furthermore, these problems are concentrated in the most deprived communities, where health inequalities and social exclusion impact on the experience of people and access to services 1. Public Health Scotland (PHS) has said:

There is an urgent need to address the adverse consequences of harmful alcohol consumption on people's health, families, communities and public services.

The Scottish Government has six public health priorities. Priority 4 is A Scotland where we reduce the use of and harm from alcohol, tobacco and other drugs.

Scale of the issue

Alcohol consumption and binge drinking are a "deep seated part of the Scottish culture"1. Public Health Scotland (PHS) has estimated that, in Scotland, 22% of adults drink at levels that increase their risk of breast cancer and other cancers, stroke, heart disease and type 2 diabetes2.

In relation to drug use, the pattern of drug use in Scotland is changing1. The Rapid Action Drug Alerts and Response (RADAR) quarterly report(October 2024), identified the following key trends:

Polysubstance use continues to drive the majority of harms, with high-risk combinations frequently involving cocaine, gabapentinoids, benzodiazepines (notably diazepam and bromazolam) and opioids

Emerging synthetic drugs such as potent nitazene-type opioids and xylazine are increasingly reported in harms

Cocaine continues to be the most common substance in both post-mortem toxicology and the ASSIST emergency department project

Contamination of drugs remains prevalent, with substances often not containing what the purchaser intended; this spans across drug types, including powders, vapes and pills (even in apparent medicines like those in blister packs)

It is estimated that, in Scotland (2019/20), there were 47,100 people with opioid dependence aged 15 to 64 years (a prevalence of 1.32%)4. The term opioid refers to a group of natural, semi-synthetic and synthetic compounds that act on opioid receptors in the brain (for example, morphine or methadone)5.

Drug and alcohol harms and deaths

In its recent report on Alcohol and Drug Service, Audit Scotland said:

The number of people dying in Scotland because of alcohol or drug use remains high compared with other parts of the UK and Europe. This is despite improved national leadership and increased investment in alcohol and drug services.

Official drug misuse death statistics are published annually by National Records of Scotland (NRS). NRS reported that 1,172 people died due to drug misuse in 2023. This is the second lowest number of drug misuse deaths since 2017, with 2022 seeing the lowest number. However, drug misuse deaths are still much more common than they were in 2000 (292).

.jpeg)

In 2022, the rate of drug poisoning deaths in Scotland was more than double the rates of other UK countries. Scotland had the highest rate of drug poisoning death (22.7 per 100,000) followed by Wales (11.0), Northern Ireland (8.3) and England (8.3).

Information is also published on indicators of harm. Primarily, naloxone administrationi, drug-related attendances at emergency departments, drug related hospital admissions, and suspected drug deaths (using Police Scotland's published quarterly information)1. The most recent publication reported that for the 12-week period (2 September to 24 November 2024), there were 215 suspected drug deaths, 10% lower than in the previous 12-week period (238). This was 20% lower than the same period in 2022 (268) and 15% lower than in 2023 (254).

In relation to alcohol-specific deaths, there were 1,277 alcohol-specific deaths registered in Scotland in 2023. This is the highest number since 2008. Male deaths continue to account for around two thirds of alcohol-specific deaths.

Scotland had the highest rate of alcohol-specific deaths (22.6 per 100,000) of the UK countries, followed by Northern Ireland (18.5), Wales (17.7) and England (15.0)2.

.jpeg)

A broader look at alcohol harms is produced Public Health Scotland in its Alcohol Consumption and Harms Dashboard, which reports on variables including inpatient hospital stays, consumption, crime and homelessness.

A focus on prevention

Since the recommendations of the Christie Commission (2011) there has been an understanding of the importance of prioritising prevention, reducing inequalities and promoting equality. The Christie report raised the need to shift from dealing with the consequences of social problems to preventing them from arising in the first place. It argued that as well as leading to better long-term outcomes, a more preventative agenda should also reduce the overall cost of public services through avoiding more severe problems and higher costs later on1.

Population health framework

In a statement on a vision for health and social care (June 2024) the Cabinet Secretary for Health and Social Care announced:

We are developing a Population Health Framework, taking a cross-government, cross-sector approach to improve the key building blocks of health.

COSLA has said that, in this 10-year plan, the Scottish Government intends to prevent problems before they arise by addressing the primary drivers of population health. It is expected to be published in Spring 2025.

Legislative framework

The main legal framework for the NHS in Scotland is the National Health Service (Scotland) Act 1978. This places a duty on Scottish Ministers to promote health improvement and to provide a range of services via health boards.

Generally, legislation does not specify a right to a particular service or treatment. There is provision in the National Health Service (Scotland) Act 1978 for health boards to provide specific services on behalf of Ministers (such as primary care, pharmacy services) but neither the 1978 Act or the Patient Rights (Scotland) Act 2011 give people a 'right' to treatments as specific as drug or alcohol rehabilitation.

Under the Patient Rights (Scotland) Act 2011, Scottish Ministers are required to publish a Charter of Patient Rights and Responsibilities this summarises the rights and responsibilities of people who use NHS services and receive NHS care in Scotland. This includes:

I have the right to safe, effective, person-centred and sustainable care and treatment that is provided at the right time, in the right place, and by the most appropriate person.

Under the Charter of Patient Rights and Responsibilities people also have the right to ask for a second opinion before making a decision about their care and treatment. They also have the right for their needs, preferences, culture, beliefs, values and level of understanding to be taken into account and respected when using NHS services. Although, health boards must also consider the rights of other patients, medical opinion, and the most efficient way to use NHS resources1.

However, it is worth noting that Section 20 of the Patient Rights (Scotland) Act 2011 restricts the potential for legal action relating to the Act's provisions. Although the rights within the Act are not legally enforceable, a patient can seek a declaratory judicial review. This is an authoritative statement that an individual or body has a specific right or duty. It is useful where the petitioner wants to establish that a particular right exists, or that a particular status applies, which has been doubted or denied.2

Alcohol and drug services in Scotland

Treatment and support services for drugs and alcohol is devolved to Scottish Ministers. Currently, Integration Authorities receive around 70% of all alcohol and drug funding and have delegated responsibility for providing local alcohol and drug services, coordinated by Alcohol and Drug Partnerships (ADPs).

There are 30 Alcohol and Drugs Partnerships (ADPs) in Scotland (Clackmannanshire and Stirling are counted as one partnership as is Mid and East Lothian). ADPs are a partnership of health and social care partnerships, health boards, local authorities, Police Scotland, Scottish Prison Service, third sector, community groups and people with lived and living experience. They are responsible for commissioning and developing local strategies for tackling problem alcohol and drug use and promoting recovery, based on an assessment of local needs1. In 2015, ADP funding was transferred from the Scottish Government's justice directorate to health.

In 2019, the Scottish Government and COSLA agreed to a Partnership Delivery Framework to Reduce the Use of and Harm from Alcohol and Drugs. This set out a shared ambition for ADPs and indicated that local areas should have:

A strategy and clear plans to achieve local outcomes to reduce the use of and harms from alcohol and drugs

Transparent financial arrangements

Clear arrangements for quality assurance and quality improvement

Effective governance and oversight of delivery.2

Information on the activity undertaken by ADPs can be found in the report on the ADP Annual Survey 2023/24. This includes information on actions to meet the outcomes of the national mission to reduce drug related deaths and harms and cross-cutting priorities (see section on ongoing and forthcoming Scottish Government work).

In March 2024, the Scottish Government published results of a mapping exercise to identify potential providers of services (including detoxification and stabilisation) for people who use alcohol and/or drugs in Scotland and in September 2024, a report on residential rehabilitation bed capacity was published.

Waiting times for specialist drug and alcohol treatment services

The Scottish Government has set a standard that 90% of people referred for help with problematic drug or alcohol use will wait no longer than three weeks for specialist treatment that supports their recovery. The three-week period covers the time from referral to treatment beginning and includes an initial assessment.

DAISy is the national database that holds data about drug and alcohol services. PHS uses this to report on drug and alcohol treatment waiting times and initial assessments for specialist drug and alcohol treatment.

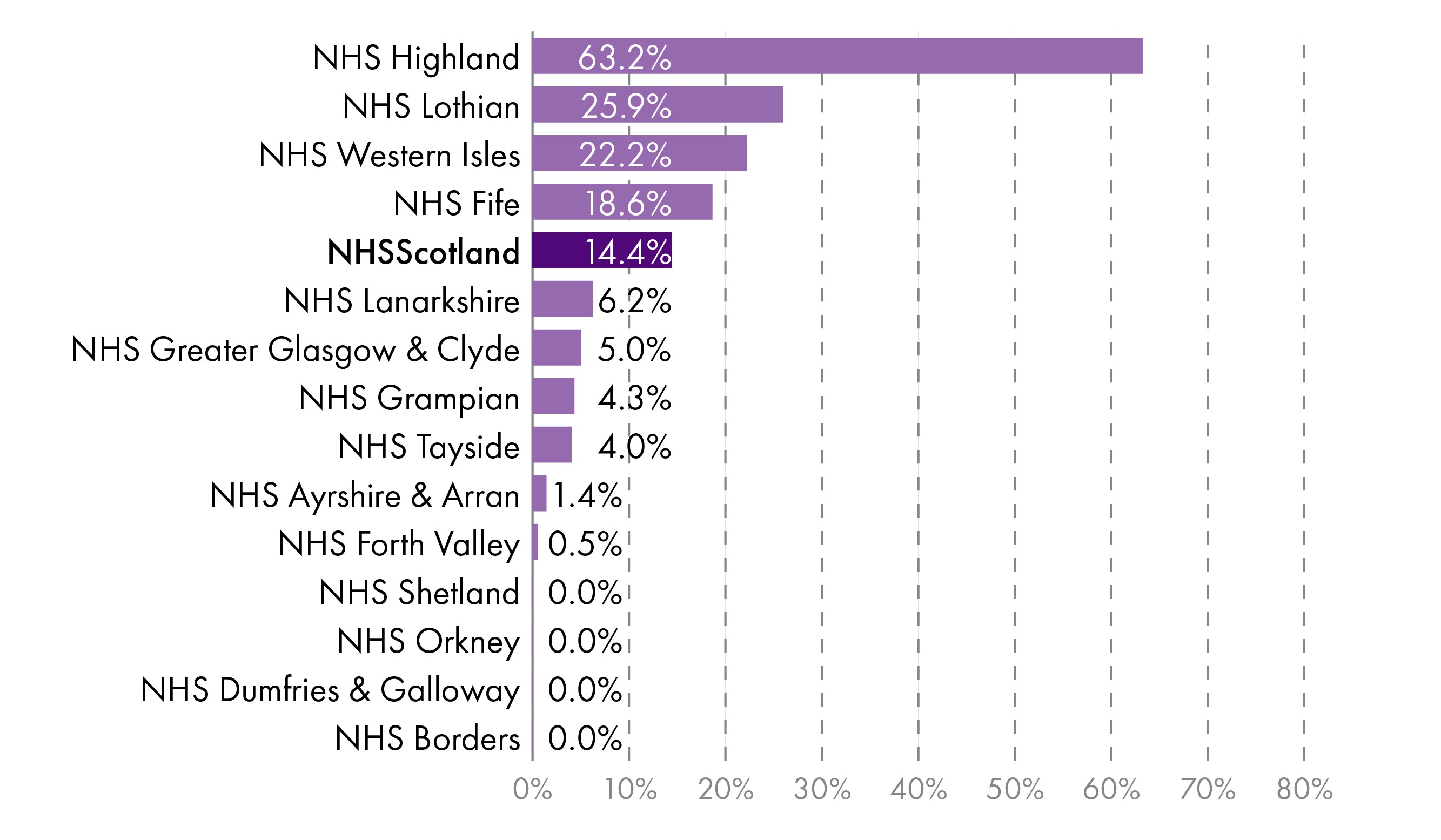

The recent Audit Scotland report found waiting times for specialist treatment vary across Scotland and key Scottish Government targets are not being met by some NHS boards. The most recent PHS publication reported that during the quarter ending 30 September 2024:

10,919 referrals were made to community-based specialist drug and alcohol treatment services: 5,493 (50.3%) were for problematic use of alcohol, 3,910 (35.8%) for problematic use of drugs, and 1,516 (13.9%) for co-dependency (use of both alcohol and drugs).

7,454 referrals to community-based services started treatment. Of these, 6,976 (93.6%) involved a wait of three weeks or less. Four NHS Boards did not meet the Standard (Lothian, 89.8%; Western Isles, 89.3%; Shetland, 78.9%; Highland, 72.3%).

Nationally, the Standard was met for referrals to community-based services across all substances: drugs (95.6%), alcohol (92.6%) and co-dependency (92.2%).

1,004 referrals were made to prison-based services. Of these, 816 (81.3%) were for people seeking help for problematic use of drugs.

357 referrals to prison-based services started treatment. Of these, 342 (95.8%) involved a wait of three weeks or less (alcohol, 100.0%; co-dependency, 97.7%; drugs, 94.7%).

2,239 community-based service referrals had not started treatment. Of these, 323 (14.4%) involved a wait of more than three weeks.

31 prison-based service referrals had not started treatment. Of these, 13 (41.9%) involved a wait of more than three weeks1

The Scottish Government does not hold information on the number of people who have requested residential rehabilitation. In evidence to the Criminal Justice Committee, Health, Social Care and Sport Committee, and Social Justice and Social Security Committee (Joint meeting),Maggie Page, Scottish Government, said:

We do not have robust data or statistics on the number of people who have requested residential rehab. I think that, once we started to unpick that, we would find it quite difficult to measure it accurately.

Opioid substitution therapy

Opioid Substitution Therapy was prescribed to an estimated minimum of 29,470 people in Scotland (in the 12-month period ending 30 June 2024). The NHS Board areas with the highest estimated numbers of people prescribed Opioid Substitution Therapy were Greater Glasgow and Clyde (8,579), Lothian (4,570) and Lanarkshire (3,032)1.

Funding for drug and alcohol services

The Scottish Government publishes information on funding allocations to NHS Boards to support the delivery of alcohol and drug services.

| NHS Health Board | Funding allocation, £ |

|---|---|

| Ayrshire & Arran | £7,838,796 |

| Borders | £2,281,445 |

| Dumfries & Galloway | £3,180,173 |

| Fife | £7,127,915 |

| Forth Valley | £5,785,410 |

| Grampian | £10,469,033 |

| Greater Glasgow & Clyde | £28,110,021 |

| Highland | £6,283,912 |

| Lanarkshire | £11,974,163 |

| Lothian | £18,098,346 |

| Orkney | £699,281 |

| Shetland | £807,004 |

| Tayside | £9,403,128 |

| Western Isles | £893,944 |

| Total | £112,952,570 |

The Scottish Government also funds a cross-government action plan intended to increase residential capacity, public health surveillance and research, operating costs, alcohol harms and for the National Collaborative. It also provides funding to the Corra Foundation to distribute to local grass roots and third sector organisations that provide services, and to third sector partners1. However, it can be difficult to measure the overall costs of tackling alcohol and drug harm across Scotland's public and third sectors2.

The Auditor General for Scotland has spoken of the importance of evaluating spending:

I will repeat the point that the evaluation of spending is the most important part that needs to happen now, to make the biggest difference in service provision and achieve a system that is flexible, gets the right balance between drugs and alcohol services and is preventative at its heart. Working with a wide range of partners in this system will give people the best chance of getting better outcomes than we see now.

Clinical guidelines for drug and alcohol use and treatment

The UK Government publishes Drug misuse and dependence: UK guidelines on clinical management. This is often called "The Orange Book" and provides guidance on the clinical management of drug use. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has published guidelines on:

Drug misuse prevention: targeted interventions (NG64)

Coexisting severe mental illness and substance misuse: community health and social care services (NG58)

Needle and syringe programmes (PH52)

Coexisting severe mental illness (psychosis) and substance misuse: assessment and management in healthcare settings (CG120)

Drug misuse in over 16s: opioid detoxification (CG52)

Drug misuse in over 16s: psychosocial interventions (CG51)

NICE has also published a guideline on alcohol-use disorders, which makes recommendations on the diagnosis, assessment and management of harmful drinking (high-risk drinking) and alcohol dependence in adults and in young people aged 10 to 17 years1. The former UK Government consulted on UK clinical guidelines for alcohol treatment and new clinical guidelines on alcohol treatment are expected to be published shortly. The aim of the guidelines is to promote and support good practice and improve quality of service provision, resulting in better outcomes2.

Ongoing and forthcoming Scottish Government work

The Scottish Government published Rights, Respect and Recovery, a strategy to prevent and reduce alcohol and drug use, harm and related deaths, in 2018. The same year, it also published its Alcohol Framework for preventing alcohol harm, which contained 20 policy actions. More recently, in January 2021, the First Minister announced a national mission to reduce drug related deaths and harms.

The aim of the national mission was to save and improve lives through:

fast and appropriate access to treatment and support through all services

improved front-line drugs services (including third sector)

services in place and working together to react immediately and maintain support for as long as needed

increased capacity in and use of residential rehabilitation

more joined-up approach across policies to address underlying issues

In August 2022, the Scottish Government published the National Drugs Mission Plan: 2022-2026 which included six outcomes:

Fewer people develop problem drug use

Risk is reduced for people who take harmful drugs

People at most risk have access to treatment and recovery

People receive high quality treatment and recovery services

Quality of life is improved to address multiple disadvantages

Children, families and communities affected by substance use are supported

The Scottish Government notes that the work of the mission was supported by the Drug Deaths Taskforce, and is currently supported by the Residential Rehabilitation Development Working Group and a National Collaborative representing the views of those with lived and living experience, the National Mission Oversight Group and a number of working groups.

An annual report was published in August 2024, this included information on progress towards cross cutting priorities, and each of the outcomes, including on meeting the Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT) Standards, community-based opioid substitution therapy and residential rehabilitation.

In an evaluation of the national mission on drug deaths PHS reported that positive impact of the national mission included the provision of additional funding, progress towards strengthening treatment systems, improved accountability and increased visibility of the needs of individuals affected by drugs. Unintended negative consequences included the loss of focus on alcohol-related harms and unhelpful pressure in the system, and the risk that the scope to have a genuine learning and improvement culture around drugs in Scotland is undermined. Missed opportunities included insufficient focus on resourcing, supporting the workforce, prevention and wider system determinants, non-opioid drug use and polydrug use, and no fundamental rethinking of models of working.

In January 2023, the Scottish Government responded to the Scottish Drug Deaths Taskforce, final report Changing Lives. Since then a number of reports have been produced including:

A caring, compassionate and human rights informed drug policy for Scotland

Analysis of the progress made against the National Mission in the Annual Monitoring Report 2022-23

A Safer Drug Consumption Facility ('The Thistle') opened in Glasgow in January 2025. This is a supervised healthcare settings where people can inject drugs, obtained elsewhere, in the presence of trained health and social care professionals in clean, hygienic environments.

Charter of Rights for People Affected by Substance Use

The National Collaborative launched its Charter of Rights for People Affected by Substance Use and Toolkit, on 11 December 2024. This aims to support people affected by substance use to realise the human rights which belong to them. It also hopes to support service providers understand and implement these rights and shift the power and change the culture from criminalisation and stigma towards a public health and human rights approach.

The key rights are drawn from the Human Rights Act (1998) and international law. The Charter acknowledges the rights established by the Human Rights Act are enforceable by Scottish tribunals and courts. Others rights need to be incorporated in to UK and Scottish law to be put into practice legislatively i. It goes on to state that "Once the proposed Scottish Human Rights Bill becomes law these internationally recognised rights will also become enforceable in our tribunals and courts".

Although not included in the most recent Programme for Government, the Scottish Government has said that it is still committed to taking forward the Human Rights Bill, but not until the next Parliamentary session. A detailed discussion can be found in the SPICe blog The Human Rights Bill – why has the Scottish Government not legislated and what happens next?

The rights set out in the Charter of Rights for people affected by substance use are:

Right to life

Right to the highest attainable standard of mental and physical health

Right to an adequate standard of living

Right to private and family life

Right to a healthy environment

Freedom from torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment

Freedom from arbitrary arrest or detention

The Charter also outlines people's right to give positive or negative feedback about their care and support and have this listened to and to complain about services. The UN has backed the International Guidelines on Human Rights and Drug Policy.

National Mental Health and Substance Use Protocol

There has also been work to implement a good practice protocol for how mental health and substance use services should work together. There are five components:

Whole system planning and delivery

Joint decision making, joint working and transitions

Leadership and culture change

Quality management system

Enabling better care

Stigma Action Plan

The Scottish Government published a stigma action plan in January 2023. This states that:

Stigma can involve negative assumptions, prejudice and discrimination against someone based on a characteristic, condition or behaviour. It is not based on fact or evidence. In the case of substance use, it is often rooted in moral judgements about the 'wrongness' of what is assumed to be a choice.

It sets out a number of actions for the Scottish Government and the development of an accreditation scheme which will include commitments to take defined and measurable actions to challenge and remove structural stigma.

National service specification for alcohol and drug services

The Scottish Government is developing a national specification for alcohol and drug services. This is intended to be the first stage in developing national standards and regulation. It is hoped the national specification will provide clarity on the range of substance use support services which should be available in local areas. It is expected to be published in early 2025.

In response to Parliamentary Question S6W-31486, the Cabinet Secretary for Health and Sport said:

The national specification is the first stage of developing national standards and regulations for substance use services. The specification will outline the types of services which should be made available within all local areas. The second phase will be the development of standards which services will be expected to meet and the third phase will be the development of regulations on the basis of which services will be inspected. It is hoped that the regulations will be published by 2028.

Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT) standards

Standards for services providing drug treatment came into force in April 2022. In Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT) standards: access, choice, support the Scottish Government said:

There is good evidence that the health of individuals with opioid dependence is safeguarded while in substitution treatment. Evidence also indicates that it is important to consider medication choice and that optimum dose for an individual is critical to achieving positive outcomes.

The 10 standards are:

All people accessing services have the option to start MAT from the same day of presentation

All people are supported to make an informed choice on what medication to use for MAT, and the appropriate dose

All people at high risk of drug-related harm are proactively identified and offered support to commence or continue MAT

All people are offered evidence based harm reduction at the point of MAT delivery.

All people will receive support to remain in treatment for as long as requested

The system that provides MAT is psychologically informed (tier 1); routinely delivers evidence-based low intensity psychosocial interventions (tier 2); and supports individuals to grow social networks

All people have the option of MAT shared with Primary Care

All people have access to independent advocacy and support for housing, welfare and income needs

All people with co-occurring drug use and mental health difficulties can receive mental health care at the point of MAT delivery

All people receive trauma informed care1

The Scottish Government's annual report stated that in 2023-24, all local areas reported good progress against their implementation plans for MAT standards. PHS publishes a benchmarking report. The most recent report found that for 2023/24:

MAT standards 1–5, 90% have been assessed as fully implemented

MAT standards 6–10, 91% were assessed as implementation is beginning

Evidence of sustained implementation and ongoing monitoring was allocated to two ADPs for MAT standard 4 and one ADP for for MAT standard 3.

The report also includes some experiential feedback to provide information on the outcomes of implementation.

The Scottish Government's residential rehabilitation programme

The Scottish Government's Residential Rehabilitation programme, launched in 2021, intended to improve access to residential rehabilitation. The Scottish Government's aim was to ensure that residential rehabilitation is available to everyone who wants it, and for whom it is deemed clinically appropriate, at the time they ask for it, in every part of the country.

The Scottish Government set two targets:

to increase residential rehabilitation bed capacity in Scotland by 50% to 650 beds by 2026

to increase the number of individuals publicly funded to go to rehabilitation by 300% to 1,000 per year by 2026.

Prior to 2021 there was a lack of robust Scotland-wide baseline data on who was accessing rehabilitation1. Information on statutory funded residential rehabilitation placements since 1 April 2021 is published by Public Health Scotland. Between 1st April 2021 and 30th September 2021, there were 212 approved residential rehabilitation placements2.

PHS published the first evaluation report into the programme in February 2024 and subsequently information on the number of individuals starting a residential rehabilitation placement between 2019 and 2023. This found that the residential rehabilitation programme (in the period until 2022/23) had coincided with a substantial increase in access to publicly funded residential rehabilitation in Scotland and a slight increase in the total number of individuals accessing rehabilitation, noting that the main change (in the period until 2022/23) has been the source of funding. In December 2024 PHS concluded that, based on available data, the Scottish Government reached its target of 1,000 individuals publicly funded to go to residential rehabilitation in the financial year 2022/233.

A number of programmes including the Residential Rehabilitation Rapid Capacity Programme, prison to rehab pathway, dual housing support fund and the additional placement fund have supported the expansion of residential rehabilitation beds. This is alongside work being done to support ADPs such as the pathways to recovery projectand the National Commissioning Framework4.

The Scottish Government has published a dedicated website https://rehab.scot/which provides a directory or rehabilitation services.

Drugs and Alcohol Workforce Action Plan

The Scottish Government's Drugs and alcohol workforce action plan 2023 to 2026 sets out a number of actions to address challenges experienced by the drugs and alcohol sector's workforce. It is focused around the five pillars of plan, attract, train, employ and nurture. It made a number of commitments including to undertake a comprehensive workforce mapping exercise, develop a learning pathway and capture the views of the workforce through an online survey. Audit Scotland has said "progress in putting some key national strategies into practice, such as implementing a workforce plan and alcohol marketing reform, has been slow"1.

The Scottish Government has also established a Workforce Expert Delivery Group which provides oversight and advice on the delivery of actions outlined in the Action Plan. The Scottish Government intends to publish a Drugs and Alcohol Workforce Knowledge and Skills Framework in early 2025. This will be complemented by the online workforce learning directory, which aims to facilitate access to training resources and support development of the knowledge and skills identified.

The Scottish Government also hopes to support increased workforce recruitment and retention of people with lived and living experience through the launch of Employability Toolkits and the ‘Guiding Principles’ for supporting employees with lived and living experience of problematic substance use2.

Alcohol brief interventions

Scotland has had a programme to implement alcohol screening and brief interventions since 2008. The Scottish Government commissioned PHS to review the Alcohol Brief Intervention programme. The review made the following recommendations for the Scottish Government (October 2024):

Reaffirm its commitment to the programme and its reorientation to flexible, evidence informed conversations about alcohol

Set out the steps by which its vision of embedding conversations about alcohol can be achieved over 10 years

Seek engagement and leadership from the Chief Medical Officer, the Chief Nursing Officer, the Royal College of Midwives and other relevant professional organisations to normalise conversations about alcohol

Recent Scottish Parliament consideration

Drug and alcohol addiction has been discussed in the Scottish Parliament on a number of occasions. On 12 September 2024, Neil Gray MSP, Cabinet Secretary for Health and Social Care made a Ministerial Statement on the national mission to reduce deaths and improve the lives of people impacted by drugs and alcohol. In this he announced forthcoming alcohol treatment guidelines to provide support for alcohol treatment, similar to the medication assisted treatment standards for drugs.

A debate on S6M-10032 investing in Alcohol Services to Reduce Alcohol Related Harm in Scotland was held on 26 July 2023. More recently, there was a Ministerial Statement on Implementing the Medication Assisted Treatment Standards.

Public Audit Committee

The Public Audit Committee undertook an evidence session with Audit Scotland, in November 2024, on the report Alcohol and drug services. This report made a number recommendations including around the accountability of ADPs, funding for tackling alcohol and drug related harm and identifying ways of developing more preventative approaches to tackling alcohol and drug problems. The full list of recommendations can be found in Annex A. It also heard from the Scottish Government and PHS on issues raised and wrote to the Auditor General for Scotland.

Previously the Committee took evidence from the Auditor General for Scotland on the report Drug and alcohol services briefing, which was published on 8 March 2022. Following this session the Committee wrote to the Criminal Justice, Health, Social Care and Sport and Social Justice and Social Security Committees to draw their attention to key issues arising from the evidence session and to help inform any future work on drug and alcohol services.

Joint meetings of the Criminal Justice Committee, Health, Social Care and Sport Committee and Social Justice and Social Security Committee

The Criminal Justice Committee, Health, Social Care and Sport Committee and Social Justice and Social Security Committee have met jointly on a number of occasions from February 2022 to consider the progress made on the implementation of the recommendations of the Scottish Drug Deaths Taskforce. At the meeting on 14 November 2024, the Committees took evidence on tackling drug deaths and drug harm from the Cabinet Secretary for Health and Social Care and Scottish Government officials. On 20 February 2025, the Committee took evidence from Members of the People's Panel and then from Neil Gray, Cabinet Secretary for Health and Social Care and Scottish Government officials.

People's panel on reducing drug deaths in Scotland and tackling problem drug use

The Scottish Parliament established a people's panel to consider the question ‘What does Scotland need to do differently to reduce drug related harms? The panel was made up of 25 people from across Scotland who are broadly representative of the Scottish population they have worked together to scrutinise the issue. The final report was published on 21 January 2025.

It made 19 recommendations:

The Human Rights Bill needs to be passed by Parliament before the Parliamentary session ends and should incorporate the Charter of Rights for People Affected by Substance Use (published December 11, 2024).

More people with lived experience should provide ongoing support and aftercare in the statutory workforce.

There needs to be appropriate anti-stigma training for staff across all public bodies, and Alcohol and Drug Partnerships led by and delivered by those with lived/living experience.

The pay and fair working conditions of people with lived experience needs to be equitable with that of equivalent public sector workers in the drug and alcohol field.

All services should be able to refer to each other e.g. police, courts, third sector and NHS.

There needs to be continuation and consistency of de-penalising minor drug offences and not imprisoning people for short periods.

The three committees should consider further action to look at the increase of drug supply in the prison sector.

There needs to be a well-publicised single point of access for specialised advice & support relating to alcohol and drug problems.

There needs to be Scottish Government action to ensure all public and third sector services are enabled and supported to share information including the justice system.

There needs to be a guaranteed and protected five year minimum period of funding for community and third sector services, including assessment and evaluation.

The MAT standards should be extended to cover all drugs causing harm.

Drug education should be included in the mainstream curriculum (curriculum for excellence) from P5 – P7 and onwards.

In order to ensure drug harm education is properly implemented in the curriculum there needs to be engagement with parents, guardians, carers and the teaching profession regarding age-appropriate content and application.

There needs to be financial support and provision for external organisations such as CREW & Clued Up to support education in schools and outreach in communities to encourage peer learning on drug harm issues. T

Where evidence proves positive outcomes, relevant services should move from a zero tolerance approach to a high tolerance approach, where appropriate for each individual.

There needs to be an equitable expansion of employability support for people in recovery including mainstream courses and apprenticeships that includes more sectors.

There needs to be continued support for people in recovery, such as supported temporary accommodation and key workers, following referral to services.

There needs to be urgent examination of the issues around poverty - including but not limited to homelessness and those suffering financial deprivation as a result of life changing events - with input from all relevant agencies including third sector and input from a people’s panel.

There needs to be an additional public awareness campaign on the distribution and use of naloxone.

In response to the report the Scottish Government said:

We have carefully considered each of the People’s Panel recommendations in turn. I am pleased to say that we support all the recommendations and would note that the majority of the recommendations are already being undertaken within our current National Mission and cross-government programmes of work. For recommendations that we accept in principle, but are not already being progressed, we will incorporate them into considerations for our post-National Mission planning.

The Right to Addiction Recovery (Scotland) Bill's provisions in detail

The Right to Addiction Recovery (Scotland) Bill1 seeks to make provisions about the rights of people addicted to drugs and/or alcohol to receive treatment. The Bill is divided into eleven sections. Sections 1 to 3 focus on a right to recovery. Sections 4 to 6 place duties on Scottish Ministers and Sections 7 to 11 include the final provisions.

Right to recovery

The Bill would seek to give people diagnosed as having a drug or alcohol addiction, by a relevant professional, a right to receive a treatment determination and be provided with treatment. Section 9 of the Bill defines a relevant health professional as a medical practitioner, nurse independent prescriber or a pharmacist independent prescriber.

Section 1 of the Bill provides that the patient is to be offered the treatment deemed appropriate by a relevant health professional. The Bill lists a non-exhaustive list of treatments, but states:

"treatment" includes any service or combination of services that may be provided to individuals for or in connection with the prevention, diagnosis or treatment of illness.

Section 2 of the Bill details the procedure for determining treatment. It outlines that the health professional must explain the treatment options available, provide information to and involve the patient in the decision making process. It makes provision for the patient to request a specific treatment and that the appropriateness of this treatment must be considered by the health professional.

The Policy Memorandum notes:

The Member would intend that this approach should then begin a holistic process based around a clear plan for the person seeking to recover from alcohol and/or drug addiction

Section 2 provides that if the health professional deems no treatment is appropriate, or if the treatment requested by the patient is not appropriate, they must provide the patient with a written statement.

This section of the Bill would also give the patient the right to consult another health professional for a treatment determination.

The Policy Memorandum notes:

It is envisaged that, where a person has been diagnosed they will normally have a treatment prescribed by the individual that diagnoses them. The Member considers that this will usually be a General Practitioner or Nurse Practitioner who would be authorised to prescribe any of the treatments in the list set out in the Bill.

The Policy Memorandum also points out:

It is important to note that there are numerous existing processes for receiving treatment that are not initiated by a formal diagnosis by a health professional, including, for example, processes that involve self-referral, and processes where individuals are referred for treatment by individuals such as social workers where treatment commences without a formal diagnosis by a health professional. The purpose of this Bill is to give people a right to treatment following on from a diagnosis of drug and/or alcohol addiction. Therefore, for individuals who access treatment through these various existing routes not involving a relevant health professional and for whom treatment is working well and progressing, the Bill would not affect this.

Section 3 of the Bill focuses on the provision of treatment. It outlines that treatment should be made available as soon as is reasonably practicable and no later than three weeks after the determination is made.

The Policy Memorandum notes:

The Bill also establishes a timescale to begin treatment of, at most, three weeks after being prescribed it but earlier if practicable [...] The Member considers that the key to addressing the level of alcohol and drugs deaths in Scotland lies in ensuring that patients do not have to wait for treatment which may potentially save their lives. For that reason, the Bill explicitly places in statute the requirement for treatment to commence no later than three weeks after the treatment determination being made.

Section 3 of the Bill also states that the treatment could not be refused unless it is considered in the view of another relevant health professional that it is not in the best interest of the patient. Section 3 of the Bill provides a non-exclusive list of reasons that can not be used to refuse treatment.

Duties of Scottish Ministers

Section 4 of the Bill seeks to place a duty on the Scottish Government to secure delivery of the rights established by the Bill.

Section 5 of the Bill places a duty on Scottish Ministers to report to Parliament annually on progress to meeting the requirements of the Bill. This would include information broken down by health board and would include information on the:

number of patients that had received a treatment determination

type of treatment

number of patients receiving treatment, by treatment

number of people who are not receiving treatment despite treatment determination being made

average waiting times by treatment

longest waiting time by treatment

number of patients that had received a written statement

number of patients who have sought a second opinion

In preparation of the report Scottish Ministers must consult people with lived experience of drug or alcohol addiction, people representing the interests of patients and health boards (and the Common Services Agency NHS National Services Scotland), local authorities and integration joint boards (integration authorities).

Section 6 of the Bill relates to a code of practice, which would outline the duties placed on health boards (and the Common Services Agency NHS National Services Scotland), local authorities and integration joint boards (integration authorities).

Final provisions

Sections 7 to 11 of the Bill cover ancillary provisions, regulation making powers, interpretation, commencement and short title.

Financial memorandum

The Financial Memorandum1 (FM) which accompanies the Bill estimated the cost of increased provision of treatment for drug and alcohol addiction, promoting awareness and understanding, reporting to Parliament, producing a code of practice, staff training.

| Costs | Year 1 cost per annum (low) | Year 1 cost per annum (high) | Ongoing cost per annum(low) | Ongoing cost per annum (high) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cost of increased provision of drug and alcohol treatments | £28,500,000 | £38,000,000 | £28,500,000 | £38,000,000 |

| Promoting awareness and understanding | £256,268 | £256,268 | £0 | £156,268 |

| Reporting to Parliament (including consultation) | £53,055 | £53,055 | £53,055 | £53,055 |

| Code of practice | £10,200 | £10,200 | £0 (in a year where revision to the Code is not required) | £10,200 (in a year where notable revision to Code is required) |

| Staff training | £200,000 | £200,000 | £0 | £0 |

| Total | £29,019,523 | £38,519,523 | £28,553,055 | £38,219,523 |

The FM notes that these costs would be incurred by a number of organisations namely, health boards, ADPs and the Scottish Administration.

The FM also notes:

The Member believes that the thorough implementation of the Bill, including the sustained investment envisaged, will lead to significant longer-term savings.

The FM refers to an independent review of drugs in England, carried out by Dame Carol Black, which called for “significant investment in this area”, and argued that:

[...] the payoff is handsome: currently each £1 spent on treatment will save £4 from reduced demands on health, prison, law enforcement and emergency services.2

The Presiding Officer has decided under Rule 9.12 of Standing Orders that a financial resolution is required for this Bill. Only the Scottish Government can propose a Financial Resolution. This usually happens at the end of Stage 1 proceedings and Stage 2 can not take place until the Financial Resolution is agreed.

Health, Social Care and Sport Committee call for views

The Health, Social Care and Sport Committee launched its call for views on the Bill on 01 November 2024 and it closed on 20 December 2024. The call for views asked eight questions:

The Bill focuses on drugs and alcohol addiction. To what extent do you agree or disagree with the purpose and extent of the Bill?

What are the key advantages and/or disadvantages of placing a right to receive treatment, for people with a drug or alcohol addiction, in law?

Section 1 of the Bill defines “treatment” as any service or combination of services that may be provided to individuals for or in connection with the prevention, diagnosis or treatment of illness including, but not limited to: residential rehabilitation, community-based rehabilitation, residential detoxification, community-based detoxification, stabilisation services, substitute prescribing services, and any other treatment the relevant health professional deems appropriate. Do you have any comments on the range treatments listed above?

Section 2 of the Bill sets out the procedure for determining treatment. It states that a healthcare professional must explain treatment options and the suitability of each to the patient's needs; that the patient is allowed and encouraged to participate as fully as possible in the treatment determination and will be provided with information and support. The treatment determination is made following a meeting in person between the health professional and the patient and will take into account the patient's needs to provide the optimum benefit to the patient's health and well-being. Do you have any comments on the procedure for determining treatment?

Are there any issues with the timescales for providing treatment, i.e. no later than 3 weeks after the treatment determination is made?

Is there anything you would amend, add to, or delete from the Bill and what are the reasons for this?

Do you have any comments on the estimated costs as set out in the Financial Memorandum?

Do you have any other comments to make on the Bill?

122 responses were received by the deadline. 41% responses (50) were from organisations, including health boards, third sector organisations, ADPs and Royal Colleges. Any late submissions received have not been included in this paper.

Key issues raised in the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee's call for views

The following section explores some of the key issues raised by the respondents to the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee's call for written evidence. The majority of respondents (74%:n=78) said they strongly agreed or agreed with the purpose and extent of the Bill. However, of these only 15 responses came from organisations. The majority of organisations said that they disagreed with the with the purpose and extent of the Bill.

.jpeg)

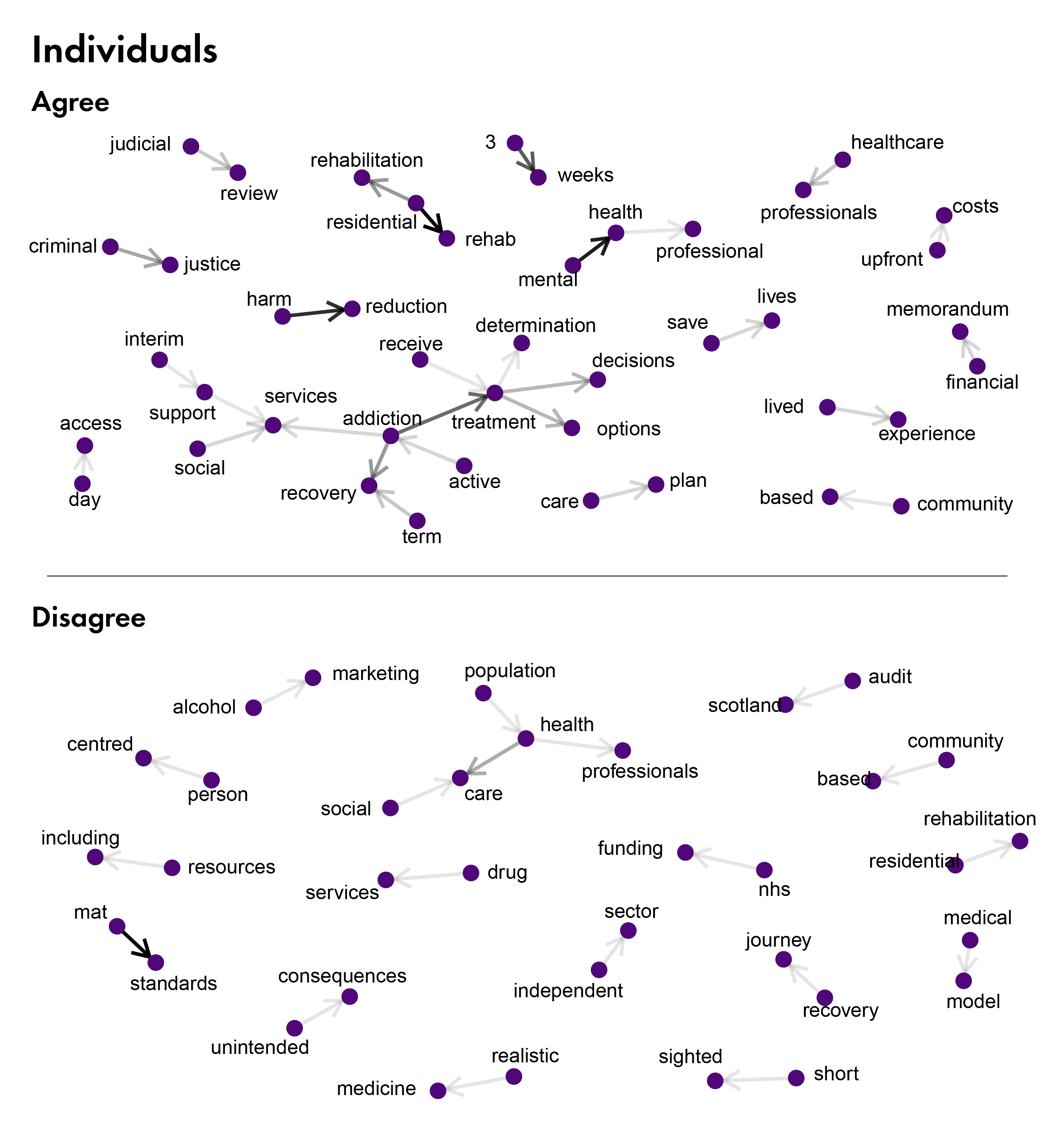

The themes raised in written submissions by individual respondents varied from those raised by organisations. The diagrams in Annex B show the key terms analysed by whether people/ organisations said they agreed or disagreed with the purpose and extent of the Bill.

Individuals in favour of the Bill highlighted residential rehabilitation, harm reduction, lived experience and mental health and timescales. Whereas, those who disagreed with the Bill had more of a focus on population health.

Organisations in favour of the Bill highlighted treatments options,recovery, journeys also timescales, lived experience and residential rehabilitation and harm reduction. Whereas, those who disagreed with the Bill had more of a focus on treatment options, human rights, mental health and professionals, MAT standards, residential rehabilitation and trauma informed approaches.

Scope and extent of the Bill

Many submissions welcomed the focus of the Bill on substance use and the ability of people who use substances being able to access appropriate and timely treatment. Some respondents made suggestions regarding the scope and extent of the Bill. Scottish Health Action on Alcohol Problems (SHAPP) commented that the aim of the Bill, to ensure everyone had access to the necessary drug and alcohol addiction treatment, was "laudable". But SHAPP considered that this would require investment, resource, training, systems change and cultural shift and a right in itself wouldn't necessarily drive the systematic action required. NHS Lothian (Public Health and Health Policy) welcomed a right to receive treatment for all patients. It went on to note:

[...] this is something that should already be provided as part of existing Human Rights and through the Patient's Rights Act, as well as being part of Realistic Medicine and the professional duties of care of those working in substance use and related services.

The Scottish Drugs Forum went further and stated that it believed that the Bill would not endow NHS patients with a drug or alcohol addiction a right to treatment:

The Bill does not offer people presenting to substance use treatment services any practical change which would make the availability of treatment more likely, more timely, or that would empower them in the process of treatment determination.

Scottish Families Affected by Alcohol and Drug said that it considered that "the required improvements to the treatment and care system can be made through full implementation and funding of existing legislation, policies, guidance and improvement mechanisms".

A number of submissions spoke of areas where the Bill could be extended. For example, Perth and Kinross ADP believed that the Bill overlooked the need for consistent recovery support for people transitioning from prison to community rehabilitation.

The Scottish Women's Convention stated that it was disappointed that gambling was not included in the Bill and referenced work undertaken with the Alliance into women's experiences of gambling addiction. The Evangelical Alliance Scotland would like to see the Bill expanded to include gambling and pornography addiction. They note that these addictions have impacts on mental health, finances, and relationships.

A number of submissions including Angus ADP reflected on similarities with the current MAT standards:

The right to access to treatment as set out in the Bill very much duplicates a small element of the more comprehensive standards set out in MAT standards, which Scottish Government has recently made clear should be extended to other substances beyond management of opiate use with OST [opioid substitution therapy], which is welcomed.

Both Social Work Scotland and Angus ADP suggested that "a major disadvantage of this Bill is that it does not give explicit consideration to polysubstance use".

Prevention/ holistic approach

The importance of prevention was raised in a number of responses. The Royal College of Psychiatrists in Scotland believed that there is a need to:

[...] tackle the drivers of addiction, and the significant barriers people with addiction face in relation to accessing treatment and support. Poverty and deprivation have been identified as key drivers of addiction in Scotland, with the likelihood of dying from a drugs-related death being nearly 16 times higher for those from the most deprived areas than the least deprived areas in Scotland.

Respondents also spoke of the link between mental health issues, trauma and addiction and highlighted the importance of linking treatment services with mental health services to help address underlying issues and improve outcomes. The importance of secure and suitable housing was also raised. Aberdeenshire HSCP noted the importance of services not exclusively delivered by the NHS such as mental health, psychological, social and emotional support. Aberdeen ADP referred to the MAT benchmarking report which highlighted the risk that focusing on treatment and de-prioritising social needs (housing and welfare) or needs in relation to support (e.g. with child protection or removal) can mean that people's underlying needs are not met at the earliest stage. This was echoed by Dundee ADP who said:

Individuals affected by substance use often require a much wider range of help and support, alongside and at the same time, as addressing their addiction issues. It is also important to recognise the need for a gendered and trauma-informed approaches to treatment / support. This wider approach to the needs of individuals is already addressed via the MAT standards and the focus on mental health / trauma-informed support. This Bill does not add anything to the requirements.

Orkney ADP spoke of the importance of having a holistic approach:

[...] medical detoxification alone is not helpful. We need to address other issues including environmental, current and historic trauma and other psychological issues

It went on to say:

This Bill takes an overly reductionist approach to recovery, placing the person at the centre of their ‘illness’ and hailing ‘treatment’ as the solution. We cannot just treat the symptoms of problematic alcohol or other drug use, we need to ensure that treatment addresses the range of issues at play, beyond the person – something this Bill has chosen to ignore.

NHS Lothian also highlighted the need greater focus on prevention to made reference to the recent Audit Scotland report, noting:

The report does not recommend the need for a Drug and Alcohol Addiction Rights Bill, however, it does recommend that the Scottish Government must ‘identify ways of developing more preventative approaches to tackling Scotland's long history of alcohol and drug problems, to target people at risk of harm before problems with substance use develop’. Addressing this recommendation is likely to be a more effective use of limited public resource than the currently proposed Bill.

Medical model

Building on the need for a focus on prevention, a number of organisational responses raised their concerns that the Bill used a medical model of substance use. Some respondents, including the Alternatives Safe As Houses Residential Recovery Project, considered that the Bill should place more focus on the "psychosocial approaches and the underlying social issues of poverty, deprivation and trauma in alcohol and drug use". In its written submission it said:

The medical model of diagnosis and treatment as proposed is flawed. Working with people affected by alcohol and drugs requires a wider skill base incorporating trust, partnership, relationships, family and social environment, trauma and understanding. To reduce this to diagnosis and treatment is limited and fails to incorporate the wider social and environmental factors influencing individual behaviours.

Orkney ADP agreed with this analysis of the Bill and said:

The treatments listed are very medical orientated and does not take into account the fact that often drug and alcohol problems are closely linked to environmental factors (poverty, deprivation, trauma, physical health etc). Without taking into account all these factors and solely focussing on medical treatment it is unlikely for stability to be achieved causing more harm to the individual.

This view was also ecohed by the a number of ADPs and Health Boards, including Perth and Kinross ADP, which said that the Bill focused on the medical model of treatment rather than addressing the wider socio-economic issues and NHS Tayside who said:

The Bill focusses on a very medicalised model of support for people who use substances. It does not recognise the very significant wider needs for psychosocial support that people who use substances often present and which are fundamental to meaningful recovery. This can include needs around mental health, dealing with trauma, unstable and unsafe housing, vulnerability to exploitation, financial crisis and many other. Interventions across all these areas are required to deliver a holistic, person centred response most likely to lead to positive change in terms of stabilisation and recovery.

Human rights approach

Many of the submissions commented on the importance of ensuring a human rights approach was taken. Falkirlk ADP said that "by framing addiction recovery as a legal right, the Bill aligns with a human rights-based approach, reducing stigma and emphasising that addiction is a health issue, not a moral failing".

Respondents also spoke of the importance of involving people with lived and living experience in service planning and delivery of service. The Jericho Society said that it supports the involvement of lived and living experience. Reform UK supported the Bill as they believe that it would guarantee access to treatment and empower individuals.

Many respondents supported people being involved in the decision making about their treatment. Harbour Ayrshire said that the procedure for determining treatment as set out in the Bill is comprehensive and person centred. The Salvation Army welcomed the importance places on the patient's participation in the process and the need for explanation and good communication. One individual respondent said:

We need to empower people to have a voice in their own treatment with as much information and support as possible.

However, some respondents questioned the role of the individual in decision making about their treatment. In its submission, the Scottish Recovery Consortium raised concerns from individuals with lived experience "about provisions in the Bill that prioritise health professionals’ authority over the individual's voice, rather than establishing mechanisms for shared decision-making diagnosis and treatment decisions or sufficient client autonomy". Dundee ADP said:

The Bill does not empower individuals seeking treatment, as decision-making about treatment largely sits with the Health Professional.

Many organisational submissions (such as, NHS Tayside) referred to the Charter of Rights for People Affected by Drugs and Alcohol and were supportive of the new charter. :

The Charter of Rights for People who Use Substances [...] embeds a Human Rights approach in provision of substance use services and supports and has been developed very much with people with lived and living experience. The Bill should take account of this, ensuring that those Rights are reflected in its language and approach, especially around decision making.

Scottish Families Affected by Alcohol and Drugs focused on a need to make progress around human rights but suggested that the Bill as proposed was not the best way to progress this:

There is much progress to be made around upholding the human rights of people affected by substance use, involving families within treatment, and supporting families in their own right – as has already been identified in previous policies. The Scottish Government has already expressed its support for the National Charter of Rights for People Affected by Substance Use, and it is essential that they deliver on this commitment.

Person centred care

Some respondents highlighted the importance of having a person centred approach and considered that an individual's involvement in a treatment decision would be a positive move. Others considered that the Bill would not result in person centred support. NHS Tayside said:

It is questionable whether a legal approach to improving access should be the preferred approach to this issue, and setting legally defined limits around the timing of access to supports does nothing to ensure that those supports are of high quality, are holistic and person centred, and reflect the rights of the individual.

This was echoed by Turning Point Scotland:

The need for a diagnosis, the imbalance of power between the person and the health professional, and the timescales for treatment are all representative of a shift away from the person-centred care we advocate for.

The Royal College of Psychiatrists in Scotland said: "there is no focus on quality of care, person-centred care or trauma-informed care provided throughout the Bill, and this is a major issue which requires addressing".

Alternatives Safe As Houses Residential Recovery Project believed that:

There should be an emphasis on empowerment of the individual, encouraging the self determination of Recovery and a recognition of the Human Rights approach in working with people

Other issues raised, included the need to focus on the aftercare people received following treatment. Some respondents commented on the importance of support following residential rehabilitation. Others spoke of the need to monitor prescription medicines that can be addictive and the need to address underlying issues such as neurodiversity.

Advocacy

Some individual respondents highlighted the need for advocacy. Examples were given of people not being able to access mental health support as a result of their addiction. The Scottish Women's Convention noted that advocacy services was a key omission from the Bill. It suggested the inclusion of an independent advocacy service for those seeking addiction recovery. The Scottish Drugs Forum also highlighted that there is no mention of a need for independent advocacy in the Bill.

Some respondents commented that people accessing services do not have adequate information prior to starting treatment. A number of individual respondents highlighted the importance of peer support and the importance of involving people with lived experience in delivering treatment services.

Family and carer involvement

Many submissions from family members of those experiencing drug and alcohol addiction highlighted the important role they can play in supporting recovery. This was an area where respondents would be keen to see the Bill developed further. Falkirk ADP said:

Families are often overlooked as part of current treatment methods, and should be supported and informed by relevant clinical or support staff of the treatment process. The Bill overlooks any rights that a family member may need to be entitled to, specifically around information sharing and access.

Alternatives Safe As Houses Residential Recovery Project considered that the Bill should have more of a focus on psychosocial support and noted that "family interventions are missing". Scottish Families Affected by Alcohol and Drugs said that the absence of family members from the Bill brought about concerns around how family members would be involved in the treatment determination and treatment process. It went on to say:

We are extremely concerned at how the absence of any mention of families in the Bill would interfere with ongoing work towards embedding family inclusive practice within services, ensuring families can participate in decision-making that affects them, and upholding carers’ rights. The participation of families can also be an important driver for participation, engagement and improved treatment outcomes for patients themselves.

The Scottish Women's Convention reported that women want improved consideration of family members when developing treatment plans and that there should be a specific inclusion of consultation with family members and/ or close friends who provide care for those with addictions.

Dundee ADP and Orkney ADP said that the Bill does not acknowledge or address the issues of the impact of substance use on family members and children and that more needs to be included around safeguarding and support for family members.

Clinical decision making

A number of organisational submissions commented on the Bill's potential impact on clinical decision making. One area of concern that was raised by a number of organisations, including NHS Fife (Department of Public Health), related to the freedom of the clinician to make decisions about care and treatment:

It is critically important that the Clinician providing care for people with drug or alcohol addiction has the freedom to deliver the care and treatment that is necessary for the individual with a timeline that will support and enable recovery. Creating a law that determines how the Clinician will deliver care may not be in the best interest of the patient [...] Our concern is that imposing a prescriptive list of “treatments” and timeline for all patients has the potential to cause harm and constrains clinical decision making.

Scottish Drugs Forum said "the process proposed in the Bill bears little resemblance to professional practice and does not take account of the lived reality of living with a drug or alcohol problem. The idea that a health professional can make a referral for treatment following a meeting with a patient is very simplistic".

Some submissions highlighted potential issues with staff knowledge and training around treatment options and rehabilitation, in particular GPs and primary care services. Falkirk ADP said:

Primary Care Health Professionals are not given enough training around substance use disorders and may not be fully aware of the underlying issues presenting. This could lead to missed, incorrect or inappropriate referrals, which may harm relationships between patients and providers.

The Law Society of Scotland raised concerns about compelling a health professional to explain all the treatment options. It understands that Montgomery v Lanarkshire Health Board (2015) found that a doctor does not have to discuss a treatment option which is, in their opinion, inappropriate. The Law Society of Scotland noted that the Supreme Court decision McCulloch and Others v Forth Valley Health Board (2023) clarified the law relating to treatment options, stating that a doctor is not required to tell a patient about all treatment options but only those which in the doctor’s clinical judgement, supported by a reasonable body of medical opinion, are appropriate.

The same concern was raised by the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) Scotland who said:

We do not believe that there is any benefit to medical professionals having to list and explain all the options listed within the Bill, particularly if they are judged to provide no benefit to the patient given their personal circumstances. Mandating health professionals to discuss options which offer no benefit to the patient has the potential to create confusion by providing information that is not relevant to in a given situation.

Role of the third sector

A number of respondents highlighted that there should be a role for the third sector in developing treatment plans. Change Grow Live raised concerns about the decision making process set out in the Bill, in particular that the relevant health care professionals, by definition within the treatment sector currently, are NHS Scotland staff. NHS Tayside said:

The Bill requires an assessment from a ‘healthcare professional’, but substance use services are delivered in partnerships between health, social care and third sector, all of whom deliver skilled assessment at different levels and across different client groups and may determine care and support needs alongside their own clients.

Diagnosis

One of the most contentious parts of the Bill is around the need for a diagnosis for addiction before a person recieves a treatment determination and treatment. PHS focused on the definitions of addiction:

The Bill describes the rights holders as anyone diagnosed as having a drug or alcohol addiction. The term addiction is a contested term. Amongst duty bearers expected to implement the legislation, there could be differences in interpretation of the term addiction.

The Scottish Drugs Forum notes that ambiguity in terms of diagnosis could lead to health professionals refusing all treatment or wider support to someone who may be experiencing significant health and social consequences of their substance use. It goes on to say "The Bill not only proposes nothing for people in this situation, it legitimises this response".

Many organisational responses to the call for views raised concerns about the need for a diagnosis in order to receive a treatment determination and subsequent treatment. One respondent said that the use of the term "diagnosis" is not in keeping with working in partnership with people seeking recovery. Others believed that the need to obtain a diagnosis would limit the number of people being able to receive treatment. NHS Lothian said: "The requirement for a formal diagnosis of addiction prior to a right to access treatment, which may exclude many of those in need, should be removed". This was also the view of SHAPP, which considered all people who would benefit from alcohol services and treatment have a right to treatment, not just people who are diagnosed as "addicted" or dependent. Alcohol Focus Scotland also made this point:

[...] the current definition in the Bill risks excluding individuals who are not clinically diagnosed as being alcohol ‘dependent’ (presumably relying on ICD-11 as the identifiable criteria, though this is not explicitly stated in the Bill) but still need treatment and support.

With You said:

We are concerned that the description of addiction used in the Bill risks preventing some people from seeking the support they need. People have the right not to be defined as “having an addiction” or “being diagnosed with an addiction”. Furthermore, many people who access our services will not want, and should not be defined by ‘an addiction’ and may instead just require some help, support or advice to change their relationship with alcohol and/or drugs. For the Bill to have a real and significant impact, it will need to be broadened to ensure all people, and not just those “diagnosed with an addiction”, can have a right to treatment.

Social Work Scotland believed that the need to seek a diagnosis may be stigmatising.

We have significant concerns about the fact that a person is required to seek the label of “addict” in order to access treatment. We believe that this can be stigmatising and, for many who do not see themselves as being “addicted”, will be a barrier to accessing support. For others who want treatment, there may be loss of agency and a sense of disempowerment if they have to seek out a label of “addict”.

Turning Point Scotland outlined a move by the sector to lower thresholds for access.

There is rarely any need for a ‘diagnosis’ before someone can access treatment and support, and that access should not be delayed while such a diagnosis is made. While the sector has recognised and is pushing for lower threshold services, that people can access when they need to, this Bill risks creating a barrier to treatment and support.

The Evangelical Alliance Scotland suggested that access to treatment should be available through self referral.

Service provision and complex treatment journeys

Many submissions commented on the complex treatment/ recovery journeys people have. The Church of Scotland welcomed the holistic approach in the Bill and the recognition that there needs to be a comprehensive continuum of services available.

However, SHAPP commented that it is not clear how the Bill relates to statutory services, such as GPs, practice nurse, addiction nurses, hospital based addiction teams, addiction psychiatrists and addiction workers. Its submission notes that "it is not clear how the right in the Bill would interact with the reality of complex treatment journeys". Perth and Kinross ADP noted that the processes described in the Bill "feels outdated, paternalistic and health- centric, in its failure to include broader recovery models".

The Royal College of Psychiatrists in Scotland spoke of siloed services in the current landscape and the potential impact of the Bill:

Consideration must be given to how the centralisation of addiction treatment under the Right to Recovery Bill could impact existing issues of siloed working and the overall quality of patient outcomes. Currently, a lack of coordination between services often leads to fragmented care, with individuals falling through the gaps between mental health, addiction, and social support systems [...] Centralising addiction treatment may risk further entrenching these silos, particularly if clear mechanisms for coordination between services are not established. For example, patients with dual diagnoses or complex needs may struggle to navigate between centralised addiction services and other critical care providers, such as mental health teams or housing support. Without a robust framework for collaboration, this fragmentation could worsen, undermining the goal of improving access and outcomes.

Patient safety

The Royal College of Psychiatrists in Scotland raised its concerns around patient safety