Public participation in the Scottish Parliament: Understanding the core principles of deliberative democracy and creating a framework for measuring impact

This report is the result of a SPICe academic fellowship in which Dr Ruth Lightbody, Glasgow Caledonian University, responds to one of the recommendations from the 2022 Citizens' Panel on Public Participation in the Scottish Parliament, that the organisation ‘Build a strong evidence base for deliberative democracy to determine its effectiveness and develop a framework for measuring impact’. The work sets out core principles and a practice framework with several recommendations for the Parliament, and has been carried out in partnership with both the Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe) and the Scottish Parliament's Participation and Communities Team (PACT).

Summary

In February 2022, the Citizen Participation and Public Petitions Committee agreed to launch an inquiry into Public Participation in the work of the Scottish Parliament. As part of this, it asked a group of 19 randomly selected people from across Scotland, who were broadly representative of Scotland's population, to come together as a Citizens' Panel to answer the question "How can the Scottish Parliament ensure that diverse voices and communities from all parts of Scotland influence our work?". The panel came up with 17 recommendations in December 2022, and the Committee took further evidence around these recommendations.

The Committee set out its vision for embedding deliberative democracy in the work of the Scottish Parliament in its final report in September 2023, agreeing to the majority of the panel's recommendations, at least in principle. Most significantly, the Committee concluded that the Parliament should use Citizens' Panels more regularly to help committees with scrutiny work, and made several recommendations for pilot and preparatory work, with certain guiding principles (see Section 4). The expectation is that, by the end of Session 6 (May 2026), the Committee will recommend a model that the Parliament can use after the 2026 election.

This report is the result of a SPICe academic fellowship in which Dr Ruth Lightbody, Glasgow Caledonian University, was asked to to respond to one of the recommendations from the Panel to 'Build a strong evidence base for deliberative democracy to determine its effectiveness and develop a framework for measuring impact’' The work has been carried out in partnership with both the Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe) and the Scottish Parliament's Participation and Communities Team (PACT).

This report sets out:

A background to deliberative democracy, both in the wider context and within the Scottish Parliament, along with detail on current practice in the Parliament and case study examples of past work.

A set of proposed core principles for the use of deliberative approaches in the Scottish Parliament, along with recommendations on a proposed framework for evaluating the use core principles in practice.

Suggestions on how to best build a strong practice repository and evidence base for the use of deliberative methods.

Several conclusions are drawn on the essential foundations of a successfully embedded approach to using deliberative democracy:

Political actors (MSPs) must show willingness to engage and show evidence of using recommendations moving forward.

Work must be ongoing to ensure activities are inclusive with proactive efforts to support wide ranging engagement. This requires a recognition that many individuals need support to engage.

Openness and transparency are key to developing public trust and public engagement so making processes transparent, and feeding back in a timely manner to participants is essential.

Deliberative processes will not always result in change, but the policy scrutiny it affords is designed to improve policy, by making scrutiny more transparent, and decisions more robust and sustainable. Expectations of participants and political actors should be managed.

Evaluation is paramount for gauging impact, experience and improving practice. Robust evaluation contributes to legitimacy and accountability. Furthermore, evaluation ensures the deliberative practice is doing what it is designed to do.

Common sense must be used for resourcing evaluation. The amount of resources (time, money etc.) should be proportionate to the process.

Timing is paramount for the success of a deliberative initiative and an ill-timed process (i.e. too late in the wider scrutiny process) can be a futile exercise. The timing of the activity in terms of accessibility for participants should also be considered.

The deliberative process must be proportionate and relevant to the topic. PACT has drawn together a useful toolkit of different deliberative methods and facilitation methods which can help the user identify what is right for their needs.

Any deliberative process should ensure that its members are supported and empowered. Facilitators and external expert must also receive support and transparency from organisers.

The core principles set out are not exhaustive, and their application must be proportionate to the deliberative process. It may not be possible to achieve all principles all in one process but adhering as closely as possible will ensure that the purpose of the process is met, and participants are valued.

Overarching recommendations for the Scottish Parliament are that:

More work must be done to build an evidence base on the use of deliberative approaches. Building a repository of cases studies will provide a long-standing and useful resource on knowledge and good practice, and highlight areas to grow. It will facilitate a national conversation and excite international interest from policy makers, practitioners, academics, and the public.

Upholding the core principles of inclusiveness and transparency is essential for facilitating the other principles – specifically public scrutiny and input – and a public facing database of current activity in the Scottish Parliament would go a long way to doing this and improving relationships between the Parliament and the public, ultimately increasing trust. Indeed, not displaying this work undervalues the commendable work happening in the Parliamentary service.

More resources could be made available to undertake the not insubstantial task of applying this framework to existing case studies to build a practice base. Learning from existing practice on how processes can be improved is a cheaper and quicker way than holding more processes without learning from the previous ones.

The development of a PACT practice toolkit, which will be a useful guide for politicians and practitioners, should be prioritised.

1: Introduction

Citizen Participation has been a growing theme in democratic practice in recent years, to the extent that it has now become an area of scrutiny, as well as a growing area of practice.

In February 2022, the Citizen Participation and Public Petitions Committee agreed to launch an inquiry into Public Participation in the work of the Scottish Parliament. As part of this, it asked a group of 19 randomly selected people from across Scotland, who were broadly representative of Scotland's population, to come together as a Citizens' Panel to answer the question "How can the Scottish Parliament ensure that diverse voices and communities from all parts of Scotland influence our work?". The Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe) acknowledged at the time that an inward-looking scrutiny focus was novel in the Scottish Parliament.

The panel came up with 17 recommendations in December 2022, and the Committee took further evidence around these recommendations, which SPICe supported by looking at examples of practice similar to the Panel's suggestions, and deliberative processes in other legislatures.

The purpose of this report is to respond to one of the recommendations from the Panel to 'Build a strong evidence base for deliberative democracy to determine its effectiveness and develop a framework for measuring impact'.

This report starts in Section 2 by providing a brief overview of deliberative democracy. It then focuses on the background of the public participation activity happening in the Scottish Parliament in Section 3. Section 4 introduces the key principles for deliberative practice, and Section 5 sets out a framework to apply when evaluating practice against core principles. Section 6 provides a toolkit of evaluation measurements, providing detail on when and how these methods can be used.

Section 7 signposts further resources including overviews of practices, case studies, facilitation methods and evaluation tools in and around the Scottish Parliament. It does so for two reasons, first for openness and transparency, in a willingness from the Scottish Parliamentary service to evaluate its own work. And second to develop a toolkit for good practice and produce a handbook to support organisers hoping to utilise participatory and deliberative practice to improve their own evaluation

Finally, the last section sets out recommendations for applying the evaluation framework and highlights area for future work.

2: Deliberative democracy background

Deliberative democracy is a form of democracy that emphasises communication, in particular the use of reasoned dialogue and deliberation as the foundation for informed policy and decision-making. Deliberative democrats argue that the process of decision-making is just as important as the outcome (see Warren 20021, Dryzek 20102). Ideally, the core principles for embedding deliberative approaches should reflect the founding principles of the parliament - openness, accountability, the sharing of power and equal opportunities (Elstub et al. 20213, Davidson et al. 20114). According to Bussu (et al. 20225), embeddedness is the capacity for a process to be flexible, to work with other processes, but to be embedded it must have ‘rootedness’, it must be established, and an accepted means of participating by the public and their representatives.

For deliberative and participatory democracy to be impactful, it is important to examine how these principles are being operationalised throughout the public policy decision-making process. As Williamson and Barrat (2022) say:

Deliberative methods must become normative tools within the policy cycle and deliberative initiatives properly resourced and planned. Such initiatives must be transparent, auditable and accountable to ensure that participant selection is appropriate, evidence is not biased and outcomes not dictated or predetermined. It is vital, too, that the cycle of participation is always closed by providing feedback on what actions have resulted from the recommendations and by building public engagement into the process.

For citizens, these deliberative initiatives are a learning experience and their design must reflect not only appropriate onboarding but also space for "just-in-time" learning. Good facilitation is vital to steer debate and ensure that all voices are heard, and recruitment must ensure that minority voices are present, listened to and respected. It is vital at this relatively early stage of deliberative democracy to increase opportunities for learning and evaluation – both within organisations and as a shared body of knowledge for all.” Mapping deliberative democracy in Council of Europe

Williamson, A., & Barrat, J. (2022). Mapping Deliberative Democracy in Council of Europe Member States. Prepared for the Division of Elections and Participatory Democracy, Department of Democracy and Governance, Council of Europe. Retrieved from https://rm.coe.int/-mapping-deliberate-democracy/1680a87f84 [accessed 24 February 2024]

As highlighted in the OECD's Deliberative Democracy Database (launched in 2023) the "deliberative wave" has been building since 1979, which accelerated in 2010.

2.1: Deliberative and participatory practice in the Scottish Parliament - Background

Engagement has been a long-standing feature of the Scottish Parliamentary service, but in recent years this has expanded to include more participatory and deliberative practice. It has also become a more formalised process, which is expected to continue and grow in the coming years. Aiming to build a practice and governance framework requires some reflection on the history of participation in the Parliament, and the current structures in place.

The Commission on Parliamentary Reform, in 2017, highlighted the importance of engaging the public in parliamentary processes and recommended that "The Parliament should establish a dedicated team whose main purpose is to support (and challenge) committees to undertake more innovative and meaningful engagement".

The Committee Engagement Unit was formed soon afterwards and became the Participation and Communities Team at the start of Session 6 of the Scottish Parliament in 2021, which coincided with the name and remit of the Public Petitions Committee being expanded to include Citizen Participation.

In parallel, the Scottish Parliament Corporate Body's Strategic Plan for Session 6 includes a commitment to "embedding deliberative democracy in the work of the Parliament".

Since the development of specialised services to support participation in the Scottish Parliament, several high-profile engagement and deliberative activities have taken place. This has included citizens' panels on primary care (2019) and COVID-19 (2021), and a citizens' jury on land management (2019). Further detail and more recent practice is set out in Section 3:2: Case studies.

Pre-Commission on Parliamentary Reform

It's useful, in looking forward, to also look back at the past practice which the Parliament can learn from. This helps to frame more recent work, but also helps to demonstrate the long-term expertise that the Parliamentary service has in the field.

Since its inception, the Scottish Parliament has always had services to support:

Public engagement and outreach, which includes both inward and outward education visits, public exhibitions and tours of the Parliament, and a public information service.

Committee consultation and evidence-taking, both formal (through ‘calls for views’ on inquiries and in committee meetings), and informal, through committee visits and stakeholder engagement such as focus groups.

Events in the Parliament, both sponsored by Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) and Committees, and those held to celebrate milestone occasions such as the session opening and Parliamentary anniversary events. There have also been visiting exhibitions and the annual Festival of Politics, all of which give people an opportunity to spend time in the Parliament building.

Separate to activities driven by Parliamentary business, MSPs connect with constituents in their role, and often use the Parliament building for this. Cross-party groups also meet in the Parliament building

Expanding engagement capacity

In Session 4 of the Scottish Parliament (2011-2016), the Parliament Day initiative focused on "taking the Parliament out of Edinburgh and into communities across Scotland.". Fourteen Parliament Days took place between November 2012 and December 2015.

At this point, the capacity within the outreach staffing resource was increased to support this work, and outreach officers were more formally integrated into the wider committee support teams (which includes clerks, SPICe researchers and media/communications specialists).

Additional outreach support for activities outside of Parliament Days facilitated committee factfinding and engagement trips, such as the Equal Opportunities Committee's visit to Islay in 2015 as part of its inquiry into Age and Social Isolation, or the Rural Economy and Connectivity Committee's visits to Orkney, Mull, Lewis and Harris as part of the Islands (Scotland) Bill scrutiny process in 2017.

Means for engaging digitally, such as using online surveys, were supported by the Parliament's internal research service. An early example would be the public survey onthe Marriage and Civil Partnership (Scotland) Bill in 2013. In 2017, a cross-organisation working group was established to explore the use of digital engagement tools, which led to the adoption of the consultation platform Citizen Space (by Delib) for use in all committee calls for views in 2021.

The majority of these services are now primarily delivered and supported by the Participation and Communities Team, in collaboration with colleagues from clerking, research, communications and public information services. With the expansion in services, there has been an increase in capacity to deliver deliberative activities, which are typically more involved and resource-intense than engagement activities like tours and visits, and participation activities like consultations, surveys and focus groups.

2.3: Inquiry into Public Participation

The Citizen Participation and Public Petitions Committee agreed to launch an inquiry into Public Participation in the work of the Scottish Parliament in February 2022. This included a representative sample of 19 people, randomly selected from across Scotland, to come together as a Citizens' Panel to answer the question "How can the Scottish Parliament ensure that diverse voices and communities from all parts of Scotland influence our work?". An inward-looking scrutiny focus was novel in the Scottish Parliament and in many ways trailblazing innovative practice for others to build on.

The panel came up with 17 recommendations in December 2022, and the Committee took further evidence around these recommendations, which SPICe supported by looking at examples of practice similar to the Panel's suggestions, and deliberative processes in other legislatures.

Embedding deliberative democracy

The Committee set out its vision for embedding deliberative democracy in the work of the Scottish Parliament in its final report in September 2023, agreeing to the majority of the panel's recommendations, at least in principle. Most significantly, the Committee concluded that the Parliament should use Citizens' Panels more regularly to help committees with scrutiny work, and made several recommendations for pilot and preparatory work, with certain guiding principles (see Section 4). The expectation is that, by the end of Session 6 (May 2026), the Committee will recommend a model that the Parliament can use after the 2026 election.

The literature is clear that deliberative processes should embody some aspects, if not all, of the following democratic norms: inclusivity, transparency, popular control and considered judgement, and the institutional goods of efficiency and transferability (Smith 20091). These norms arguably align with the Scottish Parliament's founding principles. Deliberative democrats have long acknowledged that not all democratic institutions can do all these things but, by combining various mechanisms, deliberative democrats believe that each will fulfil a different but equally vital role in the democratic process (Elstub 20142). In adopting a framework to guide the core principles, the central issues of equality, inclusivity and diversity must be considered so that these processes are accessible, representative of Scotland's rich and diverse population, and built into the political culture in Scotland (Lightbody 20233). Most literature and practice-based research highlights that the impact of deliberative processes should be measured through multiple means (see Boswell et al. 20234, Demski and Capstick 20225, Elstub et al. 20216, Deligiaouri and Suiter 20217, Bächtiger and Parkinson 20198, Michels and Binnema 20199), for example by exploring:

How such processes shape policy

How they impact on civil society

How transparent they are

How they empower the public

How transparent they make the political system

If they lead to power-sharing, power transfer and/or partnerships between various actors

How well they into link with other political processes (parliamentary committees, referendums)

How they contribute to the deliberative quality of other processes

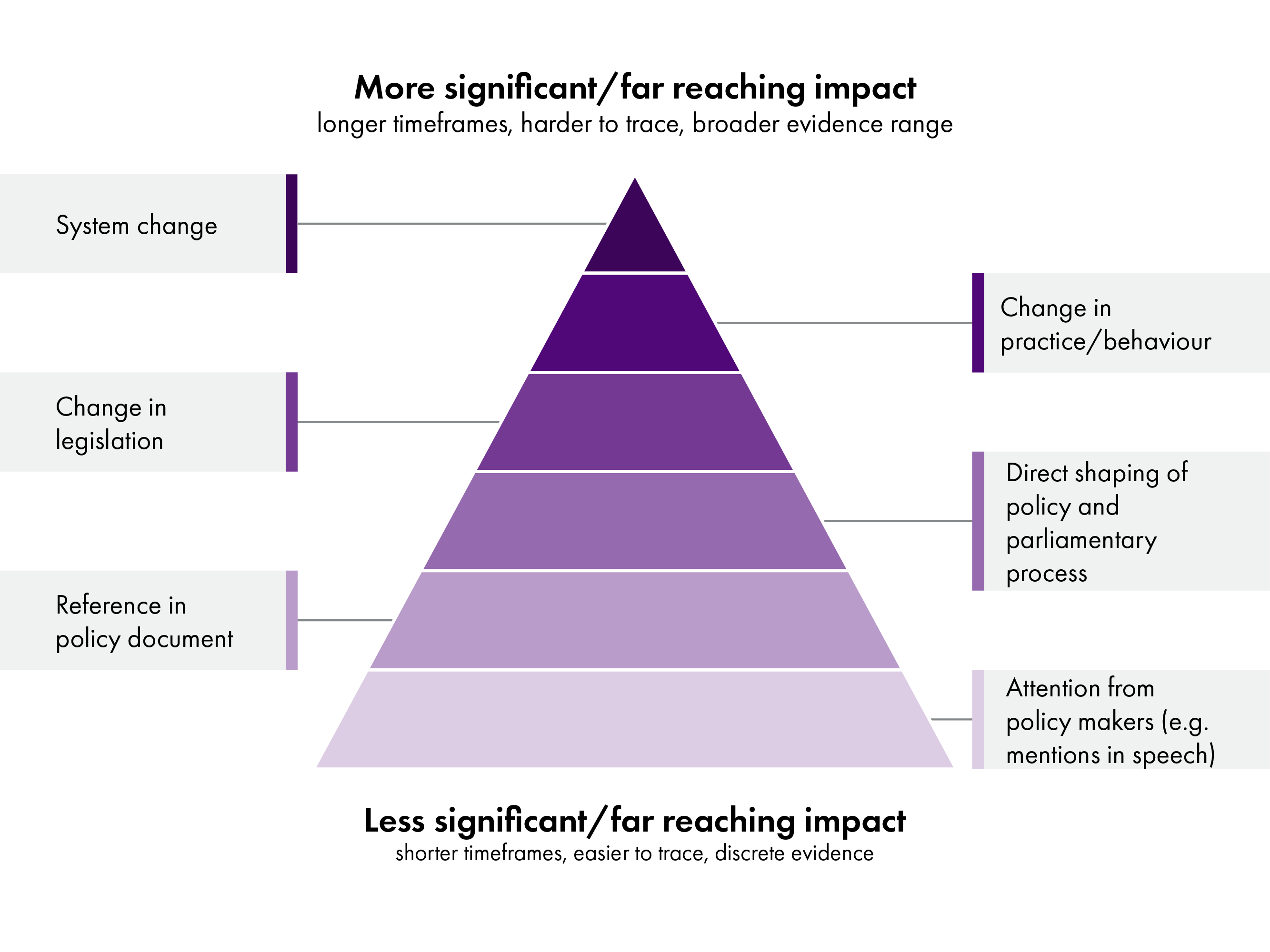

The figure below, adapted from Demski and Capstick 20225, shows how the impact of deliberative processes can be measured over time. This can be seen in more detail in the table in Annex 1.

There is a cacophony of 'deliberative' guides, toolboxes, case studies and research publicly available now which has been a result of the so-called deliberative turn (OECD 202111). And yet, what is less common is specific research on Parliamentary application of deliberative methods, and how to effectively evaluate and understand the impact of this work.

3: Current deliberative practice in the Scottish Parliament

One aim of this research project is to support the Citizen Participation and Public Petitions Committee in its aim of suggesting a set of practice principles and a governance and accountability framework which can be applied across all of these activities. Although there are currently a set of fixed processes, these are not part of a wider delivery structure, and there are no static evaluation and review processes in place.

As noted, the Committee Engagement Unit in the Scottish Parliament service was formed following the recommendation of the Commission on Parliamentary Reform in 2017, and has since expanded to become the Scottish Parliament's Participation and Communities Team (PACT).

This section focuses on the types of work done to date by PACT by taking examples from the practice history and sets out the current process for the use of deliberative practice. Note that because of the scope of this project, the focus is solely on deliberative practice, but this only forms part of the role and responsibilities of this service.

Deliberative activities have typically taken place to support the work of committees. The Scottish Parliament currently has 15 committees, most of whom focus on specific areas of policy. These committees will be responsible for the scrutiny of legislation and policy, which typically takes the form of an inquiry process. Some of this work will be allocated to committees, i.e., in the form of a draft Bill, others will be determined by Scottish Government timetables (such as scrutiny of the Budget), and other inquiries will be proactively pursued by committees.

Each committee has a 'Participation plan' created by the Community/Participation Specialist working in the wider committee support team. Design of the participation and who will lead on activities varies from Committee to Committee. Key functions include:

Community Participation - Working with partners, including third sector interfaces regionally, and other local and national voluntary and charitable organisations who work with the communities PACT and the committees want to reach.

Relationship development – PACT has its own Customer Relationship Management CRM system to send out requests, send regular newsletters on upcoming opportunities to participate and highlight key work completed. PACT has held two annual conferences inviting these partners to the Parliament to share practice, network and develop relationships. These conferences have included input and support from other offices, including SPICe, clerking and communications.

Specialised team – The team currently has five community participation specialists, all with experience of working with and for a range of communities across Scotland, bringing their own expertise and networks. In addition, two participation specialists focus on the development of digital and deliberative methods, as well as ongoing support for any other Parliamentary business where participation is requested.

3.1: Committee inquiry process

Committee inquiries will typically begin with a scoping stage. At this point, the committee clerks will work with researchers in SPICe, participation specialists and communications officers to present options to the committee of how an inquiry could be focused, and how it might take place. This might also include consultation with external stakeholders and experts and will include consideration of the Committee's anticipated work programme.

Part of this process will include considering whether participation would support the scrutiny process, if it is appropriate, and what form it might take. Proposals and the design of participation and deliberative activities will then be taken to the committee for discussion and agreement.

The process from there will vary depending on the anticipated costs and competing bids for activities to take place. In most instances, the approval process will fall to Committee Office leadership. On occasion, where a panel is expected to feed into strategic aims, approval from the Conveners Group (the strategic group made up of all committee conveners and chaired by the Presiding Officer). Should committees wish to meet formally outside of Holyrood, or travel abroad as part of factfinding, Convenors Group approval must be sought. To support the decision-making process, a payment for participation policy was agreed by the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body on 22 Feb 2024 and will come into force on 1 April 2024, and a commissioning form for all PACT work is in development.

With Committee and, where needed, financial agreement, delivery will be driven by the Participation and Communities Team, but typically with regular and sustained input from colleagues in other teams. The model of delivery, and evaluation, will vary depending on the process being used and the situation.

Within these processes, there a suite of techniques used, including the involvement of external partners and stakeholders. These are explored in Section 7 and Annex 3 of this research briefing. The following section gives examples that show the wider context of how deliberative techniques have been applied.

3.2: Case studies

The following sections outline examples of deliberative processes used to date in the Scottish Parliament.

Citizen's juries/panels

In March 2019 the first ever citizens' jury to be hosted by the Scottish Parliament considered the question of how funding and advice for land management should be designed to help improve Scotland's natural environment. Over one weekend, the 21 members of the jury heard from a range of experts about the topic and worked together to come up with a set of principles that the Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform (ECCLR) Committee should consider when exploring the issue of funding for land management and environmental impact. The jury also came to a consensus on preferred aspects for a new funding model. As is the case for later citizens' jury/panel activities, the Sortition Foundation was commissioned to recruit a random stratified sample broadly representative of the Scottish population (as at the 2011 Census), and an expert steering group was used to agree the final question being posed to the jury and ensure that the process was fair, credible and transparent.

In early-2019, the use of three public panels covering the west, north and east of Scotland and formed the first half of the Health and Sport Committee's inquiry into primary care. The Sortition Foundation recruited a randomly selected and stratified sample for each panel, and each panel went through a two-day learning and deliberative process on a citizens' panel model. Each panel came up with suggested themes and priorities for the future of primary care. The panel process was independently evaluated by Dr Stephen Elstub, and alongside a public survey and submission form the Scottish Youth Parliament, the findings went on to inform the focus of the second half the Committee's inquiry.

In 2021, a fully virtual citizens' panel on COVID-19 was held over four Saturdays. 18 panel members, recruited with the help of the Sortition Foundation, took part across all four sessions. The findings were used to support the COVID-19 Recovery Committee's work to scrutinise the Scottish Government's response to the COVID-19 pandemic at a time when the health protection measures put in place to respond to COVID-19 continued to have a considerable impact on all people in Scotland.

In Autumn 2022, as referenced elsewhere in this paper, a citizens' panel took place over two weekends to answer the question "How can the Scottish Parliament ensure that diverse voices and communities from all parts of Scotland influence our work?". The panel's 19 recommendations were then explored with further evidence-taking before being (for the most part) endorsed by the Citizen Participation and Public Petitions Committee, who agreed with the panel that the Parliament should aim to institutionalise deliberative democracy.

In February and March 2024 a People's Panel was formed to carry out post-legislative scrutiny of the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009. Participants produced a set of recommendations, which, at the time of this report being published, were soon to be incorporated in a report and then presented to the Net-Zero, Energy and Transport Committee. It is intended that the recommendations will feed directly into the Committee's scrutiny of the Climate Change (Scotland) Act. This panel is in part a pilot supporting the Citizen Participation and Public Petitions Committee's aspirations, in which it requested that two people's panels take place, one on post-legislative scrutiny and another on a topic of current interest. The latter of these panels will take place in late-2024.

Digital engagement

In 2019-20, the digital platform Your Priorities was used to inform the Local Government and Communities Committee's scoping of work into community wellbeing. Over 600 people contributed to the discussion and prioritised ideas, and, combined with the input of 65 people across five community-based sessions, this gave the Committee a clear steer on where to focus scrutiny. The outcome was the Committee's decision to carry out post-legislative scrutiny on the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015.

Your Priorities was used again in early-2023 to prioritise and gather further evidence on the recommendations made by the Citizens' Panel on Public Participation.

The platform has also been used to support committees to scope inquiries with the public; crowdsource questions to be put to the Scottish Government in Committee meetings; enable the public to comment on and discuss legislation; and provide feedback on government implementation of policy.

The use of Citizen Space for written submissions has supported an increase in submissions and has allowed Committees to vary their approach to receiving written evidence.

Other deliberative and participative practice

As part of its pre-budget scrutiny for the 2024-25 budget, the Equalities, Human Rights and Civil Justice Committee commissioned 12 members of an existing external citizens' panel to explore the human rights implications of the Budget from an intersectional and ethnic minority perspective. Following half-day education and discussion sessions, the panel came up with six questions for the Scottish Government. In October 2023, members of the panel gave evidence to the Committee, then the Committee asked the panel's questions verbatim to the Minister for Equalities, Migration and Refugees. The outcomes supported the Committee's exploration into the use of participation and deliberation in budget scrutiny and demonstrated the impact of smaller scale participation on the scrutiny process.

The Health, Social Care and Sport Committee ran a series of lived experience panels with groups of stake holders to support post-legislative scrutiny of the Social Care (Self-directed Support) (Scotland) Act 2013. Participants from five informal engagement workstreams were asked to develop a set of recommendations for the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee on what it should focus on in phase two of its scrutiny, and presented these to the Committee in February 2024.

From 2017-2020 the Young Women Lead Committee, a committee of 30 young women between ages 14 and 30 who live in Scotland, was run in partnership with the Scottish Parliament. The Committee is part of Young Women Lead (YWL), a leadership programme which focuses on increasing political participation. In each year, the YWL Committee held its own inquiry in the Parliament, and relevant Parliamentary subject committees have followed this up. In 2017-18, the Committee explored sexual harassment in schools. In 2018-19, the focus was on issues affecting the participation of young women in sport and physical activity. And in 2019-20, the Committee looked into the transition from education to employment for young women in Scotland from ethnic minorities. Consideration is currently being given to how to reintroduce Young Women Lead in the Parliament.

Activities ongoing at the time of writing

From January 2024 onwards the Local Government, Housing and Planning Committee is running a series of lived experience housing panels in order to inform its scrutiny of legislative proposals concerning the private rented housing sector.

4: Proposed core principles for practice

In response to recommendation 8 from the Citizens' Panel on Public Participation to Build a strong evidence base for deliberative democracy to determine its effectiveness and develop a framework for measuring impact, the next section is designed to support this strategic path towards institutionalising deliberative democracy by first considering what the core underlying principles of a deliberative democracy approach in the Scottish Parliament might be; and how these principles might be reflected in both a governance process (with or without legislation), and in a monitoring and evaluation framework which uses clear and measurable outcomes to understand impact.

Here, it is important to recognise that the future shape of the Parliament's deliberative democracy model will continue to evolve, but it is possible at this stage to commit to the aims below which underpin the principles and guide the process of developing an evaluation model. Based on the Panel's recommendations and its own subsequent factfinding, the Citizen Participation and Public Petitions Committee recommended:

That deliberative democracy should complement the existing model of representative democracy and be used to support the scrutiny process.

That the way in which deliberative methods are used, from recruitment through to reporting and feedback, should be transparent and subject to a governance and accountability framework.

That the deliberative methods used should be proportionate and relevant to the topic, and the scrutiny context.

That participants in deliberative democracy should be supported, empowered and given feedback on how their recommendations are used.

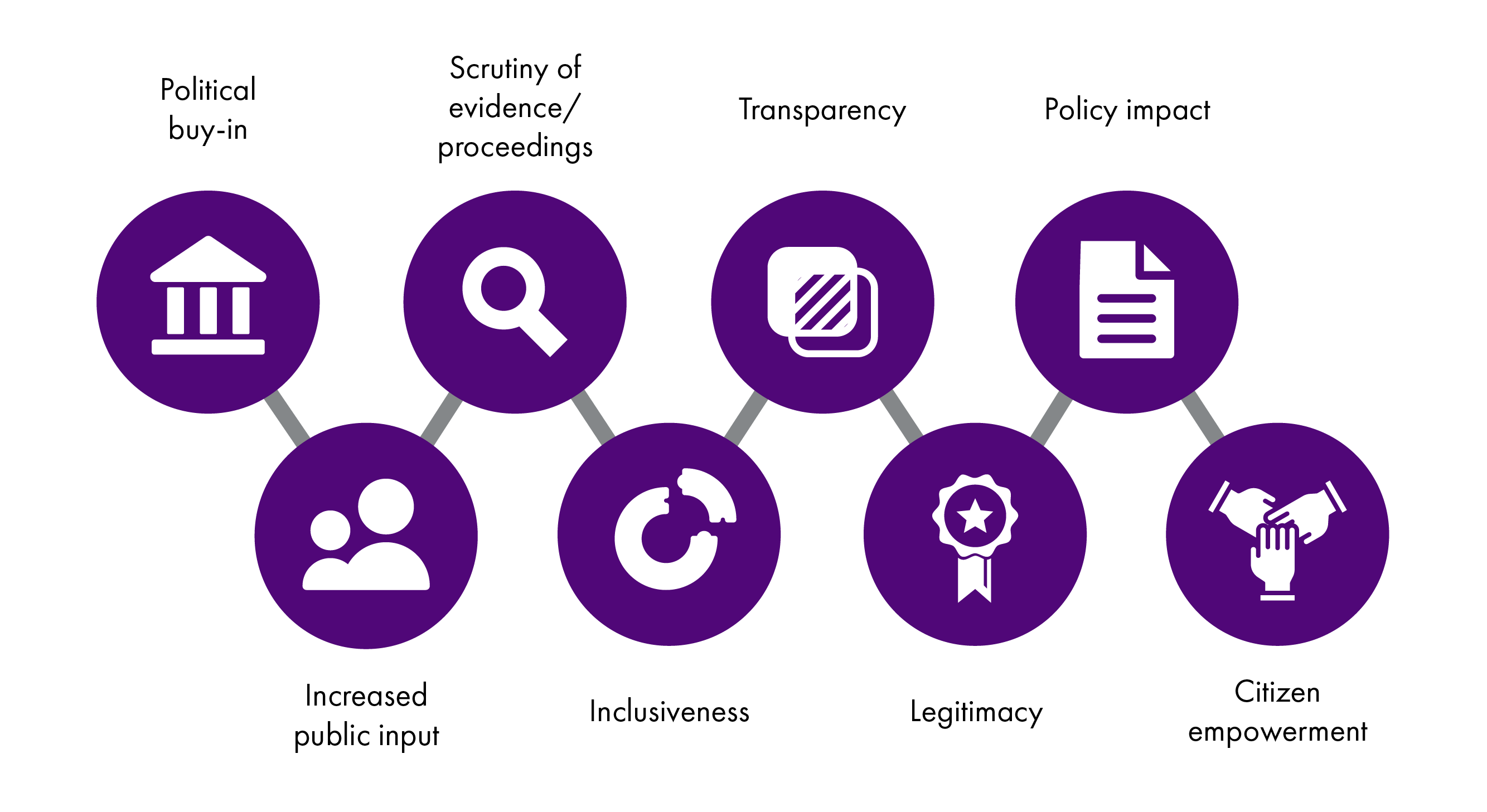

The core principles (figure 2, below) have been identified with the above recommendations in mind and developed through a scoping review of the deliberative material, both practice based and theory based, as well as from reviewing the documents from the Citizens' Panels. They have also been informed by the expertise and knowledge of PACT and SPICe Senior Researchers, and through academic application.

Vitally though, while democratic norms and key principles have been set out in Section 2 from the deliberative democracy literature, they have been adapted here specifically for use as part of an internal parliamentary scrutiny process and not an external deliberative institution. This distinction is important, as most existing examples of deliberative practice are driven from an executive level, rather than from a scrutiny perspective.

For this reason, some principles have been subsumed under different headings in order to ensure it is conducive to achieving the recommendation of the Citizens' Panel but with the recognition that it must work within the representative democratic framework of the Scottish Parliament. Within internal deliberative scrutiny processes, partnerships are likely to be built through political buy-in and public input rather than power-sharing and public led initiatives (although the public may still have the opportunity to set agenda and highlight important issues).

Furthermore, the quality of deliberation, while important, it is not deemed more important than reaching decisions, therefore principles like quality of discourse and considered judgement would be included under effective scrutiny and citizen empowerment.

The key principles and interactions with evaluation areas are explained below:

Political buy in. This principle refers to the support and commitment needed from the policy actors for the adoption of deliberative practice in policy design, not in theory but in practice. This includes a willingness to engage with the processes connected with their policy areas, to accept the resultant recommendations and outcomes, or to offer explanations as to why they cannot accept the recommendations. Processes which are explicitly supported or initiated by politicians are more likely to be 'successful' i.e. have political impact because it has political buy-in. In addition, politicians witnessing the scope of public input and their capabilities will improve relations and assure politicians that public input is valuable (see Michels and Binnema 20191, Caluwaerts & Reuchamps 20162).

Public input. Public input is the ability of citizens to operate alongside government officials and public authorities. Citizens are also more likely to accept decisions, even when they go against their own views, when those affected by them are involved in decision-making. This links with the willingness of the public to be involved, to know what is going on and to trust in the process. To witness decisions doesn't necessarily need to come from participation, and the Parliament and media have a role in making proceedings transparent and open (see Esaiasson et al. 20193; de Fine Licht et al. 20144; Clayton et al. 20195; Rasmussen and Reher 20226).

Scrutiny. Scrutiny of proceedings or evidence can have myriad of meanings. It can include scrutiny of the effectiveness of policy design (looking for strengths, weaknesses, good or bad practice, or gaps), implementation (impact assessment of policy), cost effectiveness of policy, and/or scrutinising from a particular standpoint – i.e. applying a gender analysis and mainstreaming the policy. Evidence can be presented orally, written, and/or digitally etc. Scrutiny can be undertaken by fact checking and evidence formation, asking questions and deliberating over possible outcomes and impacts, and being supported by experts to do this. The importance of capacity building and up-skilling participants ensures they are prepared and supported to be critical participants, able to apply considered judgement to proceeding, which can only be determined through the understanding of technical details by the relevant participating citizens. Drawing on lived experience and local knowledge can offer a valuable degree of scrutiny too. The chair or facilitator will be key to the independence and effectiveness of the scrutiny that takes place by guiding the agenda and ensuring evidence is robust (see Roberts et al. 20207, Geddes 20198). The use of an independent expert stewarding board in the design of activities also supports this aim.

Inclusiveness. It is vital that a process considers limits to inclusion and areas of exclusivity. How accessible proceedings are and how equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) considerations are implemented are key to the quality of process. External and internal inclusion enable us to consider where the key areas need to be focused. External inclusion refers to the ability to access a process, whereas internal inclusion refers to the quality of interaction and communication once the process is underway (see Young 20009, Lightbody 201710).

Transparency and openness. The public understands how the issue being considered has been selected, who is organising the proceeding, how decisions about the proceeding are being made and finally, how the outcome of proceedings will affect political decisions. Bringing the Parliament and its work closer to the public, opening up the scrutiny process and engaging them in policy scrutiny, supporting groups of people to engage with the policy process in a longer process, and supporting their understanding of policy through upskilling (O'Hagan 201711) will accommodate openness and trust. People will have the opportunity to become more aware of what is happening and how the Parliament and policy process works.

Legitimacy: The legitimacy of any democratic process is key to ensuring that the process is respected, and that the outcomes are seen as valid and democratic, which ensures that all actors are prepared to comply with those rules. While the deliberative processes will not be able to draw legitimacy from elections, they can draw legitimacy by following procedure, including factual and robust evidence, reasoned and informed deliberation, being open and transparent, and undergoing a robust evaluation process, but further to this, they must be perceived as legitimate by both the public and the political actors (Sandover et al. 202112, Moulds 201913).

Policy impact: Most research indicates that policy change is a vital test of impact. Policy response can include changes to policy and legislation and resulting action and/or amendments in the policy area. Therefore, policy response may mean clear change in policy design and implementation. It can also include changes to political debate/positions on issues as well. But, importantly, it can also mean no change, if the deliberative process indicates this is necessary. Therefore, measuring policy impact may include evaluating the capacity to shape and improve policy through policy responsiveness (see figure 1, Demski and Capstick (202214). Within a scrutiny context, it is more challenging to aaffect policy change and assure participants that their aspirations will be met, as the Scottish Parliament and its Committees are not the enactors of policy. Rather, impact might be visible within the content, tone and strength of the committees’ recommendations for the Scottish Government, their follow-up of these recommendations, and the changing tone of debate. Paramount in these instances is a clear demonstration that citizens' voices have been heard and reflected in the committees’ own decision-making process. One area where impacts may be more visible is during the legislative process, where committees and the Parliament as a whole play a greater role in the design and implementation approach to policy.

Citizen empowerment: This explores the longer-term public input on the proceedings of parliamentary committee work, on the way laws are debated in the Parliament, the link between law makers and people of Scotland, the creation of a culture of scrutiny by an engaged citizenry.

Deciding on the type of impact framework that would work for Scotland's geopolitical sphere, which can capture all the various working parts requires an understanding of all the different types of assessments and how they work currently. Therefore, this is not an exhaustive list but an important start in developing a framework which can be adapted and applied flexibly. It is also important to recognise that the internal deliberative practices would be aligned, coupled and linked with other democratic processes, so they would not be expected to achieve all principles at the same time and to the same extent.

5: Framework for evaluating core principles

The following section suggests questions and areas to consider when evaluating whether the core principles are evident. Not all these questions will be applicable in all processes but can offer a useful starting point.

Political buy-in

Have politicians and civil servants been willing to enter into these conversations and commit to the process?

How do policy makers use this evidence?

How do they engage with the process?

How supportive are they?

How do petitions, consultations, deliberative processes etc. impact on or feature in parliamentary comments, motions, bills etc.

Increased public input

Is there a willingness to engage with the process?

Is there anyway of including the media?

Do evaluations and consultations indicate that trust is increasing?

Are participants supported throughout and after the process?

Does the public remain engaged with Parliament following the process?

Is there an increased interest or engagement with the Scottish Parliament?

Scrutiny of evidence/proceedings

How is the quality of evidence been assured? (has it been fact checked? etc)

Does the process support members to question and hold policy makers and the policy process to account?

Is there support to develop participant's skills to scrutinise evidence?

How is the evidence presented? (consider the accessibility, readability or if orally, time for questions/reflections?

Who are the experts and who recruited/invited them? (links with policy change/impact)

Inclusiveness

What checks have been put in place to assure process is inclusive?

What accessibility issues were identified and how were they dealt with/overcome?

Who identified accessibility issues? Were participants able to highlight accessibility issues themselves?

How is it linked with other processes to widen participation?

Transparency

Does the process make the parliament more transparent? (perception)

Does it clarify roles and responsibilities for policy issue action?

Is the wider public aware that the process is taking place?

Is how the outcome/outputs will be used known to the participants, wider public and political actors?

How might wider public, political actors, groups feed in if required?

Legitimacy

Does it follow rules, advised best practice?

How legitimate is it viewed to be? (by public, by political actors)

Has it increased trust in the policy process? (by public, by political actors)

(how) is it being externally evaluated?

Policy impact

Has it improved the policies and policy making process?

Who listens and responds to output?

Have there been changes to (or new) political coalitions, networks, or cross-party collaborations engaging with processes?

If there has been no change, are there reasons for this and are the participants satisfied with these reasons?

Citizen empowerment

How do participants feel following the process? (reflection) how do they view the fairness, impact, legitimacy etc.)?

How does wider public feed into these processes?

Is there an increased uptake in participation and engagement with parliament?

Is there an increased awareness and trust in processes?

How does the process influence, shape or feed into civil society, how do civil society and media/other groups make use of outputs/recommendations?

6: Toolkit for evaluating deliberative practice

Evaluating a deliberative process fulfils several purposes.

Evaluation can:

Strengthen key actors' (such as citizens and politicians) value and trust in the process.

Ensure quality and neutrality of process is adhered to – committing to a transparent process.

Improve outputs and outcomes by increasing legitimacy and understanding.

Help organisers to learn and develop best practice.

Give public trust in parliament (OECD 20211).

The OECD recommends that evaluation is undertaken by independent bodies. They consider this to be salient for longer events (over four days) or more complex/politically sensitive processes. Evaluation undertaken by trained evaluators, who are experts in process, can be objective and fair. Actors and groups are considered independent if they have not been involved in the process or are politically conflicted.

If this is not possible then self-reporting can be necessary and is particularly suitable for shorter processes. This includes feedback from the members involved – usually anonymously – and can also include organisers, facilitators and expert contributors. These actors can offer solutions or recommendations in moving forward. Members of Parliament, parliamentary staff and individuals can be trained relatively easily to do this. Another option is opening the process up for the wider public, peers and political actors to observe and evaluate the process.

It is key to remember that there are many methods to evaluate deliberative processes and many aspects of the deliberative process that require evaluating, including the quality of deliberation, transformation of preferences, consensus, equal participation and quality of output which have not necessarily been included under these principles.

The following table concentrates on tools for evaluating deliberative practice within Parliament. Where external stand-alone processes may prioritise deliberative capacity and have wider scope or impact, here we prioritise the ability to evaluate the core principles set out in figure 2. The exact metrics will depend on the scale and duration of the process, and its purpose. It may be appropriate to discuss evaluation priorities and metrics with the participants, evidence-givers and facilitators or even the wider public to assure that the evaluation is evaluating what they would like it to i.e. what do they feel to be important? The following evaluation methods are recommended by many key researchers and organisations (including but not limited to Warburton et al. 20072, Michels and Binnema 20193, OECD 20211, Demski and Capstick 20225, Curato et al. 20236) and collated and adapted here for Parliamentary proceedings.

| Text Analysis | |

|---|---|

| What does this entail? | Text-as-data methods, such as natural language processing and machine learning, enables researchers to extract insights from unstructured text data such as policy documents, speech analysis and media analysis. |

| Which principles can this method evaluate? | Scrutiny, political buy-in, public inputThis form of text analysis can determine the deliberative quality of discourse which can help identify the level and quality of scrutiny and engagement with process by politicians and publicDiscourse initiation and impact, such as analysing the use of public consultations on parliamentary proceedings public input, media coverage and scope |

| Who would do this? | Usually external evaluators but can be carried out internally by academics, practitioners, researchers, familiar with using the software |

| How suitable is it for my reaching my goals? | Identifying how speech or comments influence parliamentary or committee conversations. For optimal results, use with other evaluation processes.There are multiple means of undertaking text analysis. One popularised by Steiner (20127) Discourse Quality Index explores the deliberative quality of speech. This has been used in studies such as Davidson et al. (20178) looking at deliberative in the UK leader debates but other text-based analysis can trace if the deliberative content appears in policy documents or is discussed in Parliament |

| How do I get started? Essential readings and links | Bächtiger, A., Gerber, M. and Fournier-Tombs, E. (2022)9Policy analysis can be a useful tool to measure change and impact to policy. This article is a useful introduction to policy analysis with deliberation:Fischer, F. and Boossabong, P.(2018)10 Wagenaar, H. (2022)11 |

| Examples of text analysis in studies | Davidson, S., Elstub,S., Johns, R. and Stark, A. (2017)8.Chalmers, A. and Aiton, A. (2023)13Fraccaroli, N. Alessandro Giovannini, Jean-François Jamet (2020)14 |

| Observation | |

|---|---|

| What does this entail? | Surveys, interviews, focus groupsWill often be undertaken before and after event in order to measure changes of opinion, feelings and perspectives over a period of time. This can measure perspective change but can also give insights into the quality of process from the perspectives of participants, committee members organiser and facilitators. |

| Which principles can this method evaluate? | Important for measuring short- and long-term impact. Political buy-in, public input, inclusiveness, transparency, effectiveness of scrutiny and accountability, and legitimacy, policy change/shaping and citizen empowerment |

| Who would do this? | Usually experts: academics and practitioners will conduct interviews or focus groups. Surveys can be self-completing but they will need to be designed and provided for participants |

| How suitable is it for my reaching my goals? | Survey have the benefit of being anonymous therefore participants may feel more able to report more freely. Surveys can also be used to gauge how the wider public viewed the process.Interviews and focus groups are a source of rich data but can be time consuming. For bigger deliberative processes, they are a rich source of data. For smaller processes, they may be time consuming and asking too much of participants. |

| How do I get started? Essential readings and links | Gastil, J. (2022)15OECD (2021)1Talpin, J. (2019)17 |

| Examples in studies | Curato, N., Chalaye, P., Conway-Lamb, W., De Pryck, K., Elstub, S., Morán, A., Oppold, D., Romero, J., Ross, M., Sanchez, E., Sari, N., Stasiak, D., Tilikete, S., Veloso, L., von Schneidemesser, D., and Werner, H. (2023)6 |

| Self-evaluation/self-reporting | |

|---|---|

| What does this entail? | Self-evaluation can be undertaken by participants and organisers. This can include note taking, reflective diary entries and self-evaluation surveys. These will often be used where funds do not allow for external evaluation or short processes. Many longer processes will include self-evaluation surveys for participants in addition to the external reports. |

| Which principles can this method evaluate? | Political buy-in, public input, inclusiveness, transparency, effectiveness of scrutiny and accountability, and legitimacy, policy change/shaping and citizen empowerment. But as above, not as robust or rigorous as external evaluated methods but can be very useful |

| Who would do this? | Those involved – participants, organisers, facilitators. |

| How suitable is it for my reaching my goals? | It can be an effective way to reflect on practice and hear back from those involved. It is cheaper than getting external evaluators in and can be an efficient way to evaluate the process.Participants are very able evaluators of how effective and accessible they found a process. Organisers can find it difficult to be objective but insights into their experience can be a useful reflective tool, especially if they follow a set impact measurement tool to undertake the evaluation.Any self-evaluation is at risk of being subjective, yet all valuation will be from the viewpoint of the person doing it. |

| How do I get started? Essential readings and links | OECD (2021)1 |

| Examples in studies | Knobloch, K.R., Gastil, J., Reedy, J. & Cramer Walsh, K. (2013)20 |

7: Evidence, case studies and repositories

While this report looks at the deliberative practices in the Scottish Parliament and sets out a suggested framework for evaluating the principles in practice, it is key to connect that with the wider work of the Parliament. More repositories and databases are popping up (see OECD, Participedia, LATINNO and on a smaller scale the Scottish Poverty and Inequality Research Unit's Local Directory) and it would be wise for the Scottish Parliament to follow suit, and for it to lead the charge for Parliamentary transparency and development of databases. Building a repository of cases studies will provide a long-standing and useful resource on knowledge and good practice, and highlight areas to grow. It will facilitate a national conversation and excite international interest from policy makers, practitioners, academics, and the public.

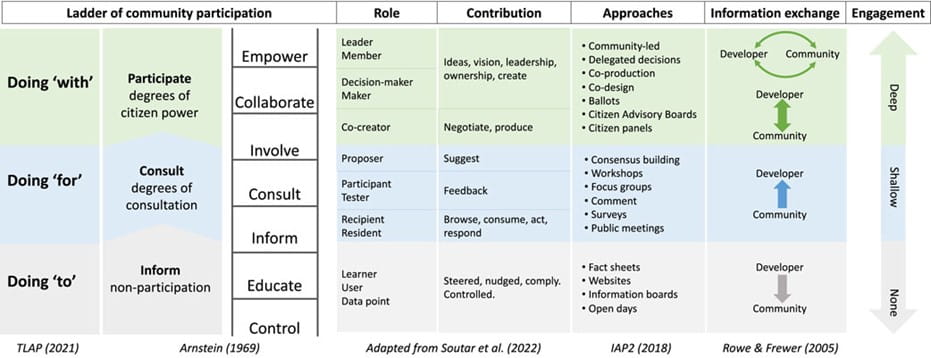

In Annex 3 we start to build such a resource. Using Roberts et al. (2023)1 schematic ladder of participation (in Annex 2) we map different participatory processes which have taken place in or with parliamentary members. Here, PACT has begun work on detailing the different type of work happening, highlighting where processes work 'with', 'for' and 'to' citizens. For different aims, issues and outcomes, different processes will work and while it is not always appropriate to power-share or for processes to be citizen driven, sometimes it is. PACT shows examples of where there are opportunities to work 'with' citizens (i.e. People's Panels), but also to work 'for' them (Inquiries and Committees) and sometimes to be doing outreach 'to' the public (one-way information campaigns and educative sessions).

Combining these practices and mapping good practice is fundamental to achieving the principles set out in this report and delivering wider civic engagement and longer deliberative practice through up-skilling. Ultimately participatory and deliberative processes aim to develop a critical body of citizenry capable of recognising credible sources, unpacking government information, empowering citizens to scrutinise the policy process and the work of the Parliament.

8: Recommendations

Work is evolving and ongoing in this area and we should not assume this to be an end point. The principles for this type of deliberative practice will not necessarily be the same for deliberation happening elsewhere, such as large and national Citizens' Assemblies or activities at a community level. However, a series of recommendations can be made from the evidence to date, and here we set out a summary of the main recommendations and future work.

8.1: Principles

Political buy-in is complex to measure. Political actors (MSPs) must show willingness to engage and show evidence of using recommendations moving forward. Tokenistic gestures of engagement will only succeed in breaking down relations between the public and Parliament.

Barriers to engaging with these sorts of processes exist, which impacts on public input and inclusiveness. Work must be ongoing to ensure activities are inclusive with proactive efforts to support wide ranging engagement. This requires a recognition that many individuals need support to engage. Barriers are multifaceted, and practitioners should learn from past recruitment and let participants feedback about what has helped them to participate. Crucially, they should also give opportunity to those that cannot participate to feedback about the challenges they faced in participating. (see Public participation in the Parliament report Key Message 8)

Openness and transparency are key to developing public trust and public engagement so making processes transparent, and feeding back in a timely manner to participants is essential. The Citizen's Panel's recommendation 12 recommends nine months after an activity as a default time to feedback and update participants, but there is also merit in ensuring the wider public is abreast of activities and can stay informed if they wish to.

Deliberative processes will not always result in change, but the policy scrutiny it affords is designed to improve policy, by making scrutiny more transparent, and decisions more robust and sustainable. Expectations of participants and political actors should be managed.

There are key areas to remember when putting this framework into practice, which the next section explores.

8.2: Putting an evaluation framework into practice

Evaluation is paramount for gauging impact, experience and improving practice. Robust evaluation contributes to legitimacy and accountability. Furthermore, evaluation ensures the deliberative practice is doing what it is designed to do.

Common sense must be used for resourcing evaluation. The amount of resources (time, money etc.) should be proportionate to the process. Previous external evaluation contracts for citizens’ panels have run to £5000-6000 per panel, not including the internal resource required to recruit and manage an evaluation contract, the use of this approach should be proportional, and the requirement for use clear. A small, day long process could be evaluated internally, depending on the policy area, and a longer event (four days) would require more time and a more robust evaluation process using external actors, such as practitioners and critical friends.

It is vital to consider the timing of the deliberative activity. Timing is paramount for the success of a deliberative initiative and an ill-timed process (i.e. too late in the wider scrutiny process) can be a futile exercise. The timing of the activity in terms of accessibility for participants should also be considered. For instance, consider using evening and weekends to support wider participation. The overall delivery of a deliberative process is key in order to manage expectations and feasibility. This should include allowing enough time to hold steering groups, secure participation of experts, prepare materials, and for development of any panel-commissioned sessions between activity days. Therefore, when considering the use of a deliberative process, timing is key.

The deliberative process must be proportionate and relevant to the topic. PACT has drawn together a useful toolkit of different deliberative methods and facilitation methods which can help the user identify what is right for their needs.

Any deliberative process should ensure that its members are supported and empowered. This can be achieved by adhering to the principles and ensuring the members know what the outcomes might be and how they will be used. In addition, facilitators and any experts who are brought in to contribute to the process must also receive support and transparency from organisers.

The core principles are not exhaustive, and their application must be proportionate to the deliberative process. It may not be possible to achieve all principles all in one process but adhering as closely as possible will ensure that the purpose of the process is met, and participants are valued.

8.3: Overarching recommendations

Based on the findings of the research the following sets out recommendations for future work:

More work must be done to build an evidence base on the use of deliberative approaches. The Scottish Parliament is doing some innovative and world leading work round participation and deliberation and a space to catalogue this, such as a repository, is a useful practice-based tool for other Parliaments.

Building a repository of cases studies, knowledge and good practice, and areas to grow will provide a long-standing and useful resource and facilitate a national conversation and international interest from policy makers, practitioners, academics, and the public.

Upholding the core principles of inclusiveness and transparency is essential for facilitating the other principles – specifically public scrutiny and input – and a public facing database of current activity in the Scottish Parliament would go a long way to doing this and improving relationships between the Parliament and the public, which will increase trust. Indeed, not displaying this work undervalues the commendable work happening in the Parliamentary service.

More resources could be made available to undertake the not insubstantial task of applying this framework to existing case studies to build a practice base. Learning from existing practice on how processes can be improved is a cheaper and quicker way than holding more processes without learning from the previous ones.

The development of PACT's toolkit, which will be a useful guide for politicians and practitioners, should be prioritised.

Annex 1 - Measuring the impact of deliberative processes

| Type of impact | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Area of impact | Instrumental impacts:Changes to how things work and what happens: policies, behaviour, practice | Conceptual Impacts:Changes to how people think: knowledge,understanding, attitudes | Capacity-building impacts:Changes to what people do: skills development, ability, confidence |

| Policy: Effects on public policy and political decision-makingKey actors: policy-makers, politicians, parliamentarians, civil servants, advisory bodies | Changes to policy and legislation, and resulting actionChanges to political debate/positions on issue | Changes to policy-makers knowledge and understanding of diverse public perspectives on policy issueChanges to policy-makers understanding of and attitudes towards issue and issue related actionClarification of roles and responsibilities for policy issue action | Capacity-building focused on specific policy recommendations and policy areasCapacity-building to improve understanding of and integrating public perspectives into policy issuesChanges to (or new) political coalitions, networks, or cross-party collaborations |

| Social: Effects on public discourse and public, business and civil society engagementKey actors: public, media, businesses and third-sector organisations | Changes to public action/behaviour changeChanges to media practices and coverage on issues and actionChanges to policies and practices in businesses and organisations | Changes to key actors' knowledge and understanding of diverse perspectives on policy issuesChanges to key actors understanding of and attitudes towards policy issue and related actionClarification of roles and responsibilities for policy action | Capacity-building in the media to support new formats and ways of communicating about policy issue (and public perspectives)Capacity-building within business and third-sector organisations to support new initiativesCapacity-building focused on enabling key groups in society to participate in decision-making |

| Systemic: Effects on democratic systems and systems-thinking | Changes to democratic systems/forms of GovernanceSystems-thinking embedded in decision-making and governance | Changes to understanding of and attitudes towards the use of deliberative processesChanges to understanding of policy issue challenging more foundational aspects of societyIncreased trust and sense of empowerment among public | Capacity-building focused on the use of deliberative processes and new forms of governanceCapacity-building focused on addressing policy issue from a systems perspective |

Annex 2 - Ladder of community participation

(Roberts et al. 2023)1

Annex 3 - Examples of PACT practice and delivery aligned with Roberts et al’s Ladder of Community Participation

The tables in this section show PACT activity to date, mapped out against Roberts et al's Ladder of Community Participation. This is not an exhaustive list of activity, or a fixed format, rather it aims to demonstrate how PACT work might be set out in a repository of practice as per the repost section 'Evidence, case studies and repositories' and recommendations on 'Evaluating deliberative practice'.

Each table represents a different step on the ladder - doing 'to', doing 'for', and doing 'with'

| Area of activity | Approaches | Why do we deliver this? | Role and Contribution of Participant | Review process and outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parliamentary Awareness (PA) | Description: Bespoke PA sessions are designed around the Parliamentary business that has motivated a session or on request from a group/org. This may be before consultation on a Bill or Inquiry for a community group that have had no prior engagement with the Parliament before.Approaches: These sessions are largely delivered by our Community Participation Specialists and are either in person or online sessions. They will consist of:

| PACT have identified that general education around what the Scottish Parliament does, and our team's role in the Parliament, is necessary to initially engage groups to have the confidence and knowledge to participate. Barriers to participation are removed by offering general information on the processes of the Parliament, an opportunity to ask questions and raise concerns, and explain why groups/participants are being consulted for their views by providing: information, trust building opportunities, and expectations management of the Parliamentary system and processes. | Role: LearnerContribution: Non-participatory, however, as part of wider committee work PA sessions enable participants to ask questions and clarifications on how their participation will contribute to the outcomes. | Review is minimal for PA as it can be very light touch, one off events, and therefore challenging to gather feedback from.In general, the most common challenge for participants first engaging with PACT is understanding the difference between the Scottish Parliament and the Scottish Government.An outcome of PA is setting the context for participants to enable them to contribute with confidence.The responsibility for delivering this type of engagement does not just sit with the PACT team and includes; visitor services, education and public information. |

| Area of activity | Approaches | Why do we deliver this? | Role and Contribution of Participant | Review process and outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Committee Inquiry or Bill PACT support | Description:PACT deliver opportunities for communities and seldom heard voices to contribute to the work of committees including; Bills, Inquiries and Committee Business Planning.Approaches:The team have a range of specialist skills in community and public engagement that ensure committee and parliamentary work involves a range of voices. PACT also manage its own database of regional and topic specific contacts. Across the team there is regional connection with Third Sector Interfaces across Scotland. Participation can take place face to face as well as digital (using our online dialogue tool Your Priorities).There are varying timescales for delivery of work from 3 weeks to up to 6 months, dependent on the type of bill or inquiry the committee is pursuing. Working with committees and other Scottish Parliament support services from the outset of the inquiry/bill ensures that needs of both the committee and participants are met during the process. | As a service team we provide the dedicated support and skills provision to ensure that consulting with a range of communities is trauma informed, considers safeguarding requirements and is accessible for a range of needs.Consistent feedback from participants, Members and other Scottish Parliament support services through PACT's evaluation highlights the necessity to have dedicated support to facilitate witnesses/participants to bring vital views for committee consideration. | Role: participants are provided with a space to contribute and share their views, ideas and experiences with Members and committees. The consultation may be with individuals or representatives of communities of interest through organisations.Contribution: participants and relevant organisations contribute their lived experiences through a range of methods including; focus groups, round tables, informal discussions with Members, and workshops designed for consensus building. | Evaluation Survey: this is sent to the participants, Members and other Scottish Parliament support services once the work is completed. PACT collect survey data and report on a quarterly and annual basis to measure whether all stakeholders felt safe, supported and assess the quality of the participation experience. Most evaluation work is done immediately after completion of work as capacity does not allow for extensive follow up post the completion of work.Reflective practice: for larger pieces of work the team will have verbal reflective practice sessions with all support teams involved in the work. Outputs from these sessions are incorporated into quarterly and annual reports.PACT reports: any outputs from Your Priorities/digital participation are analysed and compiled in a report for the committee and/or SPICe to incorporate into wider committee reports. Notes from in-person sessions are usually sent to groups for review and clarifications before being published on the committee webpage.Outcomes and outputs: dependant on the size and length of piece of work, generally, participants will be sent any final reports, invited to formal committee meetings to hear results of inquiries etc., and will be informed of any follow up outputs via email. |

| EXAMPLE OF PRE-INQUIRY COMMITTEE SUPPORTSocial Justice and Social Security Committee: Child Poverty and Parental Employment Inquiry 2022 | Using a community engagement approach was central to the success of this visit, for example, long term relationships with Uist Council for Voluntary Organisations and other local organisations.It enabled us to work quickly to collaborate on the delivery of a series of community meetings on a sensitive and private issue in a rural and remote area. | The engagement was part of a pre inquiry scoping exercise undertaken by the Committee. The purpose was to understand on a local level the implications of living in different areas such as rural, island and urban environments; exploring the barriers and challenges in terms of child poverty and parental employment, and, to hear about local approaches. Participants were consulted in a series of focus groups.This approach allowed Members to deep dive into the issues, local infrastructure, and landscape. | Feedback from participants included:"I found the whole engagement was well put together, the group of individuals there gave a wide variety of experiences and information that presented the struggles facing families in our community. It was refreshing to (be) felt heard when discussing this topic and gave me hope that this might mean some actual change in provision and support for parents. I look forward to hearing more on how this enquiry progresses, and would be more than happy to be involved in anyway I can as it does." (Parent from Uist)"….Face to face and being able to show the team the place we operate and live from and the discussion format was helpful." (Third Sector organisation)Feedback from Members included:"….the activities added value - understanding the geographical context of both visits" (MSP) | Survey post participation and participants were sent updates and a final report that was published for the Committee on the inquiry. |

| EXAMPLE OF COMMITTEE INQUIRY SUPPORTConstitution, Europe, External Affairs and Culture Committee: Culture in Communities Inquiry 2022 | The Constitution, Europe, External Affairs and Culture Committee wanted to engage communities across Scotland to explore 'culture in communities'; exploring infrastructure, who decides on ‘culture’ in a local area, and any barriers to participation. We engaged with key stakeholders in three localities to arrange visits with Members of the Committee and a series of round table conversations at each location to explore the themes to date of the inquiry. | Working closely with a range of key partners in each locality, PACT co-designed round tables with organisations to bring a range of community voices to the table and facilitate a comfortable and supportive environment for them to engage with Members.Responses to the question of why you participated on the post evaluation survey included:"To be able to highlight both the success and challenges of running a small arts-led group in an island context. To hopefully give the committee a clearer picture of the wide-range of activity that takes place, and its impact and benefits across the community, but at what cost - minimal financial resources and huge volunteer commitment." (Orkney participant) | Participants were consulted in a series of workshops and round tables.Feedback included:"the round table format was good and allowed a free flow of conversation and a chance for all voices to be heard. Wouldn't want a larger number of attendees - seemed that it was a good balance of committee members and contributors.”"(Edinburgh participant)Comments from the evaluation highlight some of the challenges of understanding the impact of participation: the report is not published until three months after the engagement and therefore those consulted are not clear on the outputs/outcomes. | Surveys were sent approximately two weeks after all engagement activity had been completed. Notes taken from the round tables were sent to all participating organisations for sign off and then incorporated into a wider inquiry report for the committee. On completion of the report, which was presented and discussed in a formal committee meeting, it was shared with all organisations involved. |

| Area of activity | Approaches | Why do we deliver this? | Role and Contribution of Participant | Review process and outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partnership Development | Description: PACT work with a range of community, third sector, charity and democratic sector partners across Scotland and internationally. PACT has a range of audiences to reach and utilises key contacts with organisations and services to connect with these audiences, as highlighted above, to ensure the team is continually developing and reaching the need of a range of participants. Approaches: Partnership development can be in the form of distinct projects or regular meet ups. PACT design and deliver an annual ‘Third Sector Conference’ in the Parliament to keep regular update and networking with key stakeholders. | This work is vital to ensuring that PACT incorporates continuous improvements into its planning and assists with planning objectives and strategic need for the team.It ensures that any work that PACT is commissioned to deliver for Committees, for example, is if high quality due to the existing working relationships with relevant organisations and services across Scotland. | Role and contribution: Participants and organisations are involved through a range of projects.This partnership working involves collaboration and co-design with the organisations and their stakeholders.Current partnership development projects include:

| Review processes will be bespoke to the project or piece of work delivered.A key outcome is the continued linking and partnership with relevant organisations to ensure that any parliamentary work delivered by the team will be of high quality due to existing professional relationships with relevant organisations and services. |