Promoting Healthy Ageing in Scotland

This briefing discusses the strong influence that lifestyle and environment can have on healthy ageing, current policies to encourage healthy ageing in Scotland, and emerging anti-ageing drugs that could be used to promote healthy ageing and reduce age-related disease burden in the future.

Executive Summary

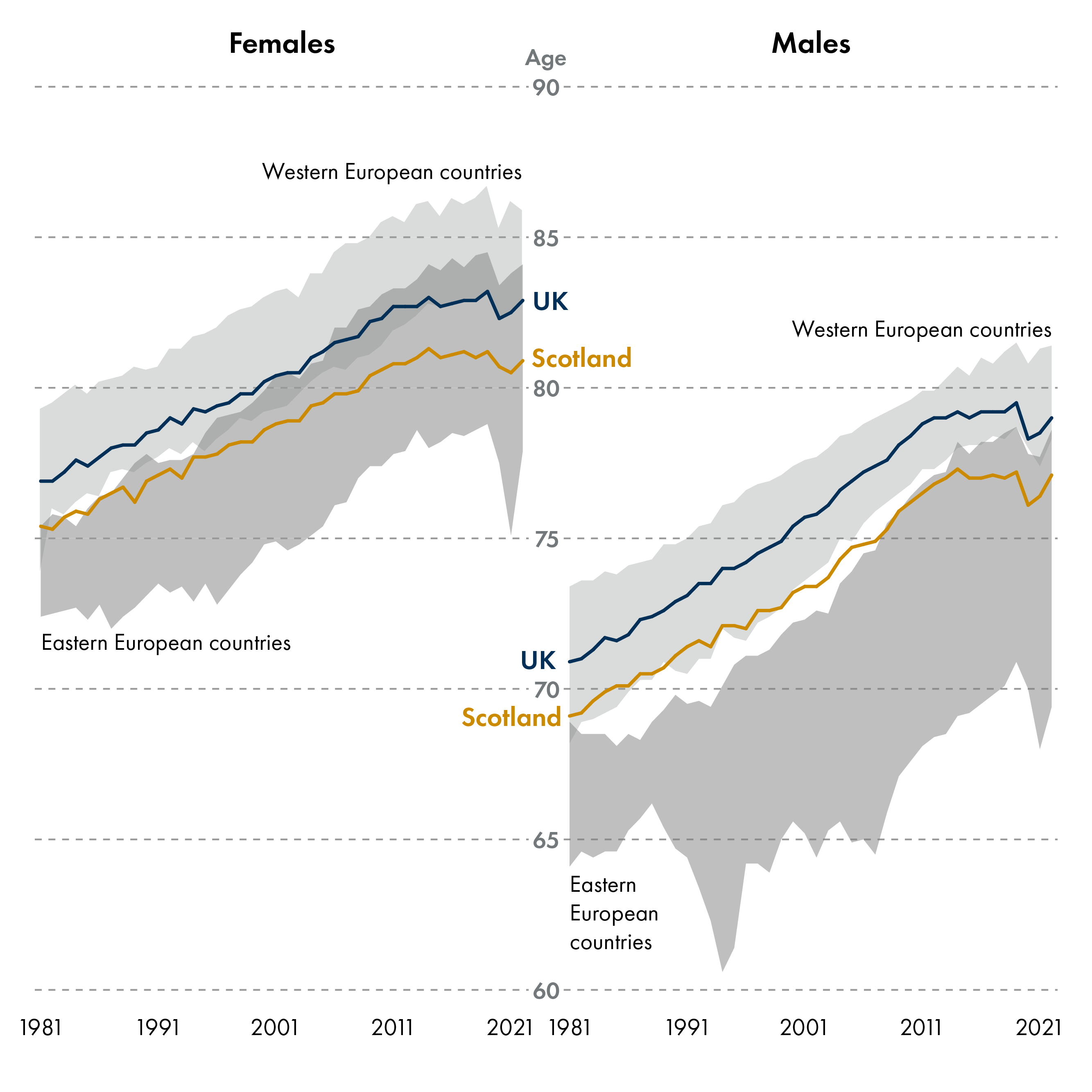

Scotland's population is ageing, and now has more than a million people aged 65 and over. Ageing gradually diminishes health and increases disease risk, yet the rate of ageing varies among individuals. Accelerated ageing leads to decreased healthy life expectancy, meaning a larger portion of the life is spent in poor health – creating a higher healthcare burden and reduced quality of life. Scotland has a low life expectancy and healthy life expectancy compared to the rest of the UK and the lowest life expectancy of all Western European countries. Men and women living in the most deprived areas in Scotland live 17 and 21 fewer years in good health respectively than those in the most affluent areas1. The latest Chief Medical Officer for Scotland Annual Report 2024-2025 focused on the broader societal benefits of promoting healthy ageing.

Ageing Population and Healthy Life Expectancy: Scotland's population is not ageing healthily compared to the rest of the UK and Western European countries, creating a higher healthcare burden and reduced quality of life.

Health Inequalities: Life expectancy and healthy life expectancy vary by gender, region, and socio-economic background.

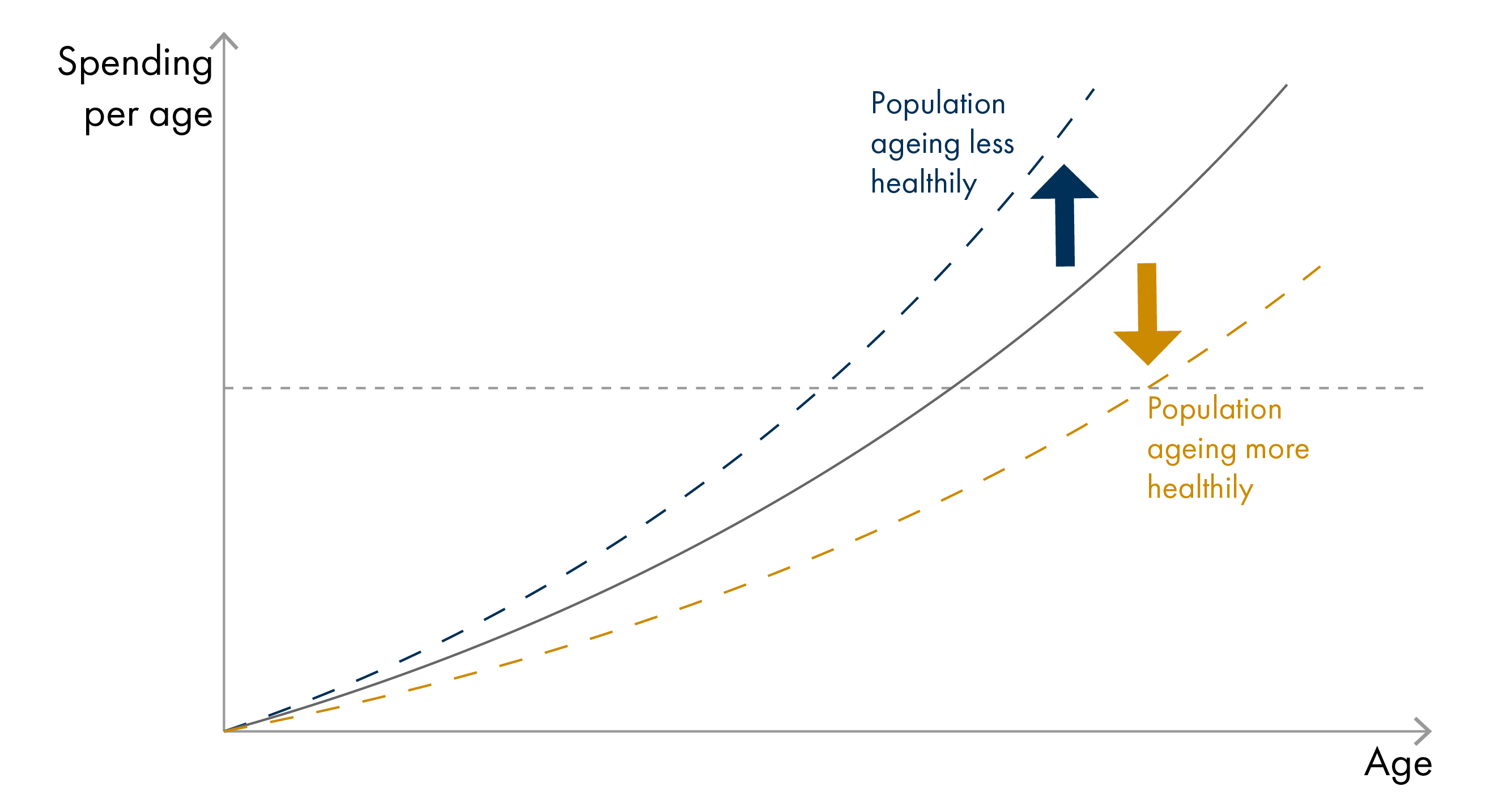

Economic Impact: An ageing population is projected to lead to increased healthcare spending, increased caring responsibilities, and an older workforce. Projections show significant future budget pressures, which could be reduced by promoting healthy ageing.

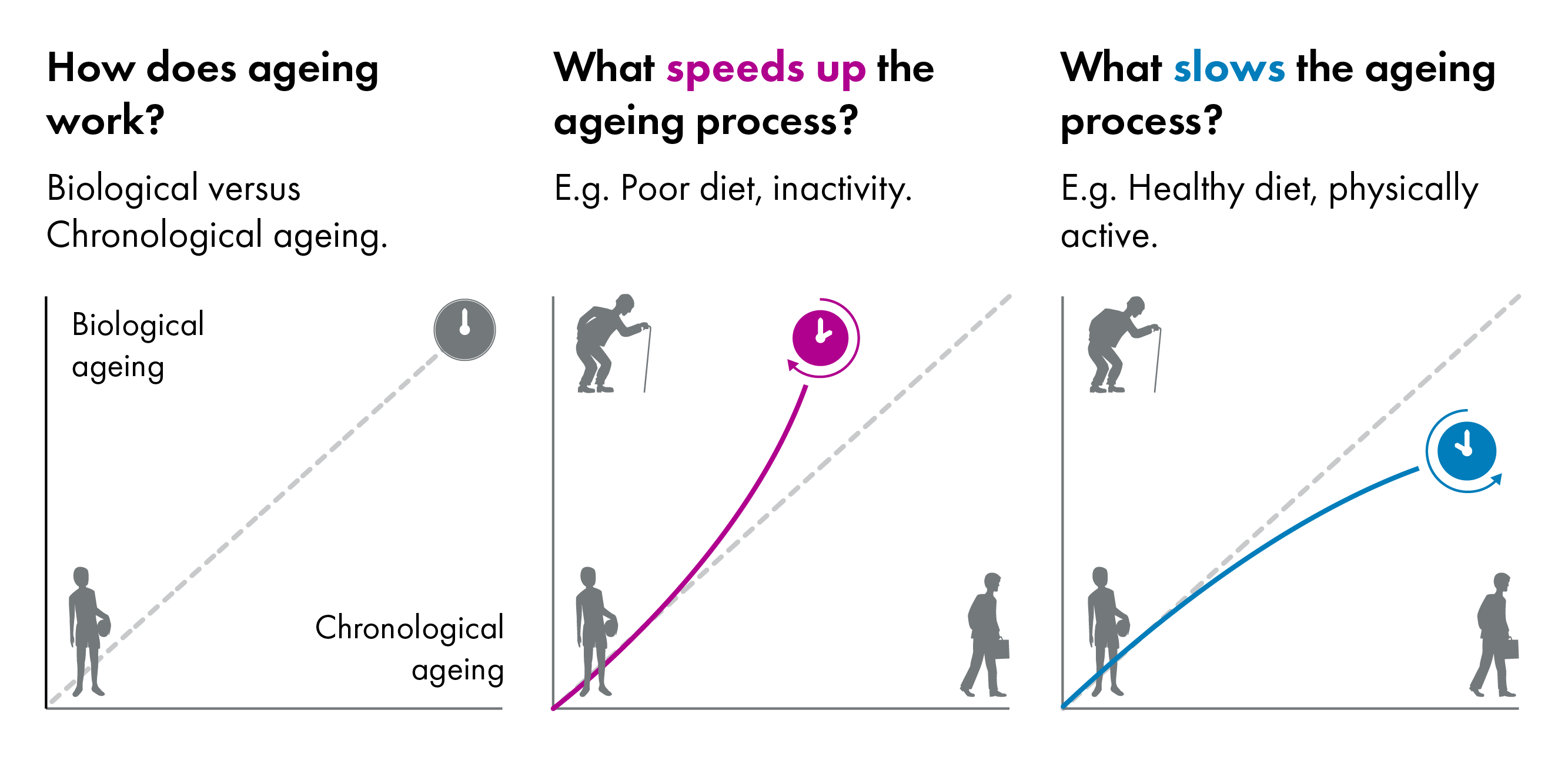

The Ageing Process: Chronological age measures the number of years since birth, while biological age describes the rate that the body itself is ageing. Research into the factors that accelerate ageing has uncovered key biological mechanisms that underpin the ageing process.

Environmental and Lifestyle Factors: Healthy ageing is affected by environmental and lifestyle factors more than genetics, emphasising the importance of a healthy diet, physical activity, and social connections to maintain good health into old age.

Emerging Anti-Ageing Approaches: Research into anti-ageing drugs show promise in extending healthy life expectancy by targeting biological ageing processes, but further investment is needed to boost their discovery and development.

Public Health Strategies: Strategies to promote healthy ageing include increasing physical activity, improving nutrition, and reducing social isolation. Initiatives such as Scotland's Population Health Framework aim to improve life expectancy and reduce health inequalities.

Authors

Dr. Joy Edwards-Hicks is a Principal Investigator in the field of immunometabolism at the University of Edinburgh's Institute for Regeneration and Repair. Her work focuses on how metabolic processes influence immune cell function, particularly in the context of ageing and inflammation. Dr. Erin Brown is a Research Technician in the Edwards-Hicks laboratory currently working on how fats influence immune cell function.

Scotland's Population is Ageing

Scotland's population is ageing. In 2024, 1 in 5 people were aged 65 and over (compared to 1 in 8 people in 1980), and this increase is projected to continue until 2047 as the youngest of the ‘baby boom’ generation reach their 80s.

The change in population structure is driven by two main factors: fertility and mortality. Over the past 50 years there has been a steady increase in life expectancy, while the number of births has been declining. While living for longer is positive, the increased life expectancy is not necessarily coupled to increased healthy life expectancy, meaning that people are often faced with an extended period living in poor health.

Migration also impacts on population structure. As people moving to Scotland through international migration tend to be younger, this partially offsets ageing trends.

This section explores the data on life expectancy and healthy life expectancy and the potential social and economic costs of an ageing population, and the positive impact that a healthy older population could have for society.

Life Expectancy and Healthy Life Expectancy

Life Expectancy

Life expectancy is the average number of years someone is expected to live from birth. It is calculated based on the average age of death among people with similar characteristics, such as current age group, sex, and where they live. How long someone is expected to live from birth is an important way to identify and compare trends in death rates across different populations, regions within a country and between nations. Examining these patterns provides valuable insights into the overall health and wellbeing of a country’s population, as well as pinpointing specific areas or groups where certain factors are leading to shorter lifespans.

Healthy Life Expectancy (HLE)

Healthy Life Expectancy (HLE) is closely related to life expectancy. It is the average number of years that someone can expect to live in good general health, based on self-reported health status. For example, while someone may live to the age of 75, they might begin experiencing long-term health issues from the age of 55, spending the final 20 years of their life in poorer health. In this case, their HLE refers to the number of years (55) they were predicted to live in good health before these conditions emerged.

HLE is determined for different populations by combining estimated life expectancy with health data from the APS. While life expectancy estimates how long populations might live, HLE provides broader insights into the overall health of a population. It reflects the proportion of individuals within a population who report they are in good health at a given agei.

While caution is needed in the comparison of life expectancy and HLE from small sample groups (e.g. unemployment by age band), both of these measures are crucial for understanding and addressing health inequalities across region, gender, ethnicity, and socio-economic background1. Importantly, understanding health inequalities informs health policy and delivery of public services.

Geographical Differences in Life Expectancy and Healthy Life Expectancy

Gender Differences in Life Expectancy and Healthy Life Expectancy

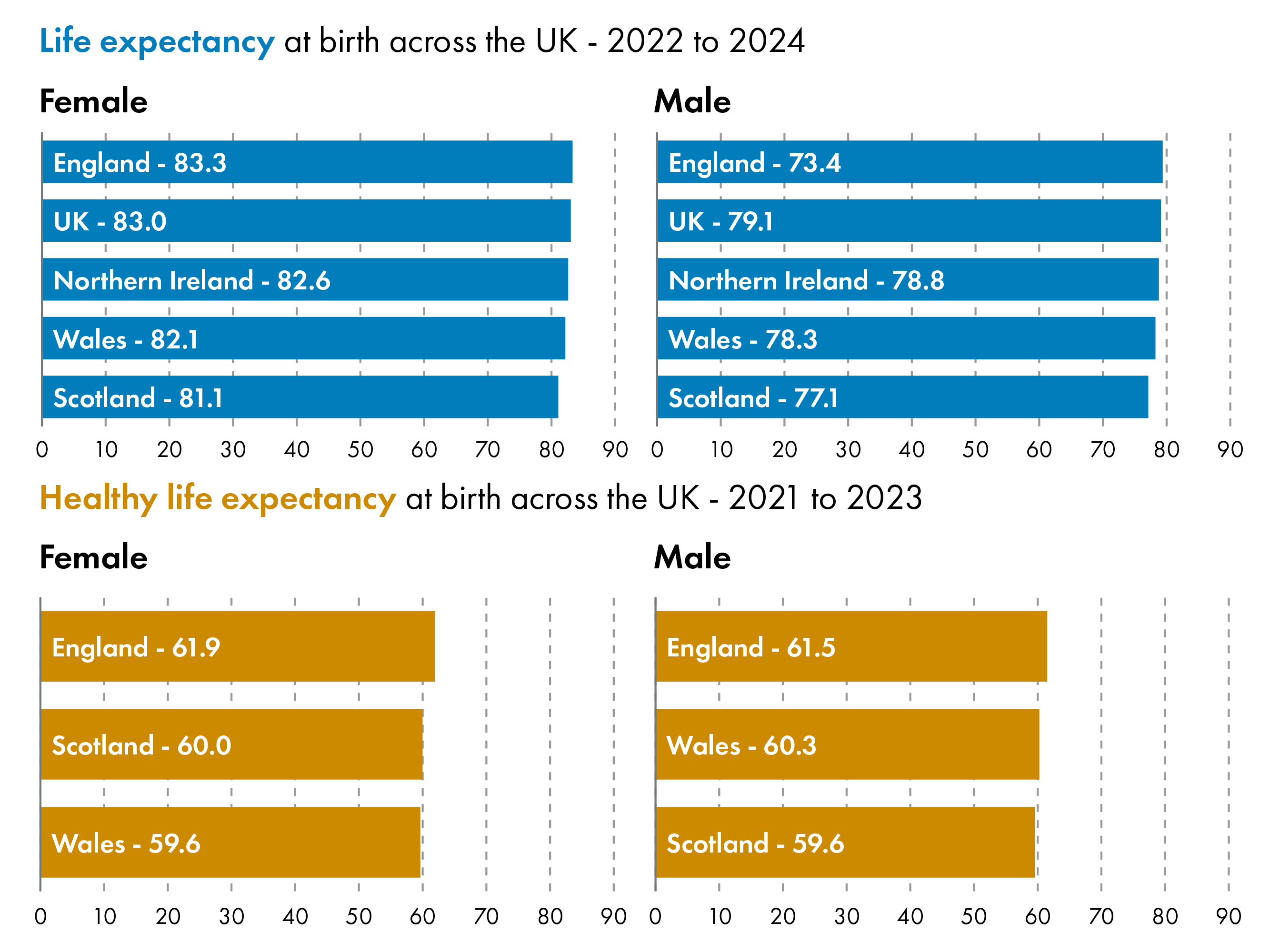

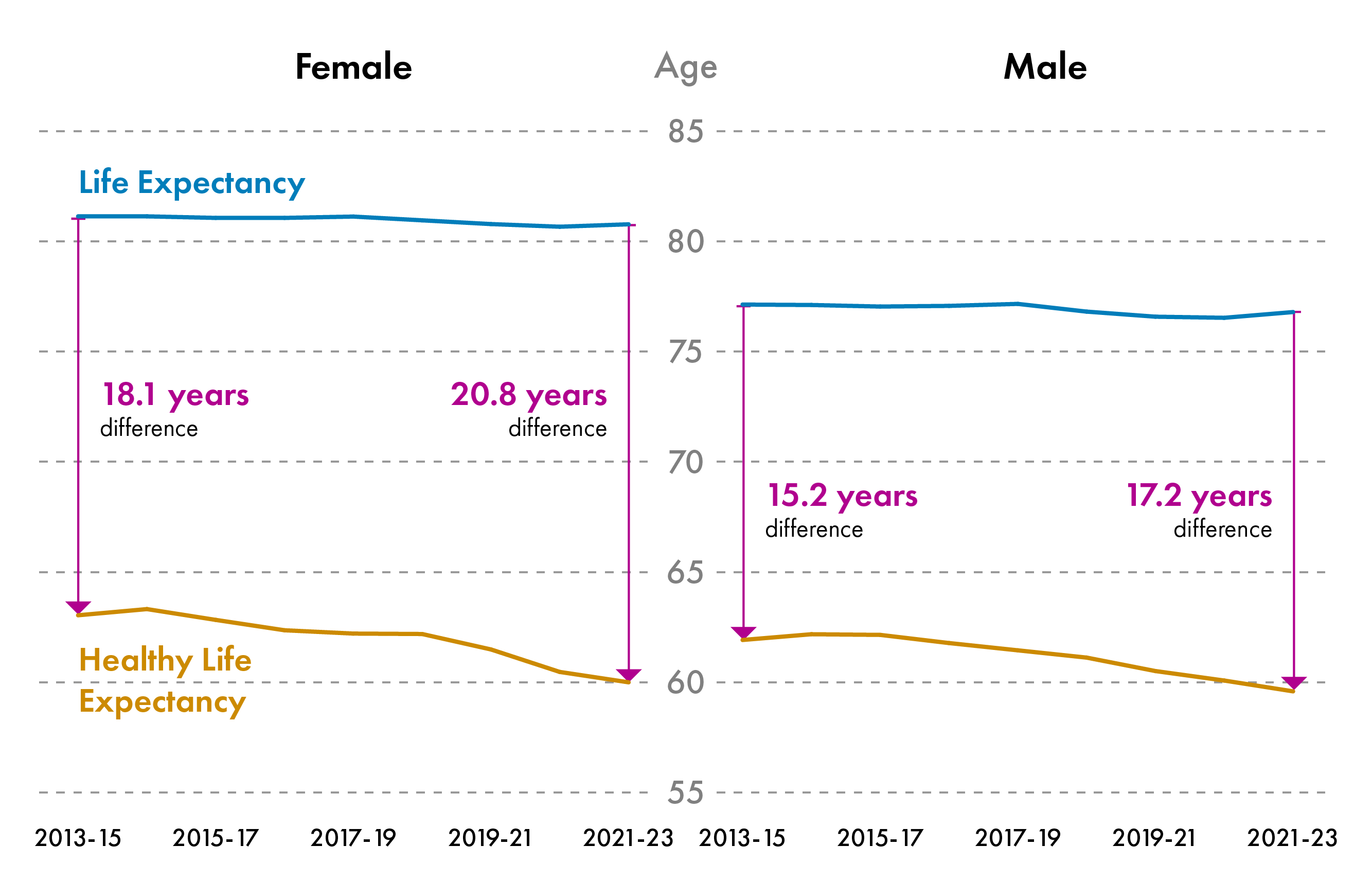

There are gender differences in life expectancy and healthy life expectancy in Scotland.In 2022-2024, Life expectancy at birth was 81.1 years for females and 77.1 years for males. Healthy life expectancy at birth was 60.0 years for females and 59.6 years for males.

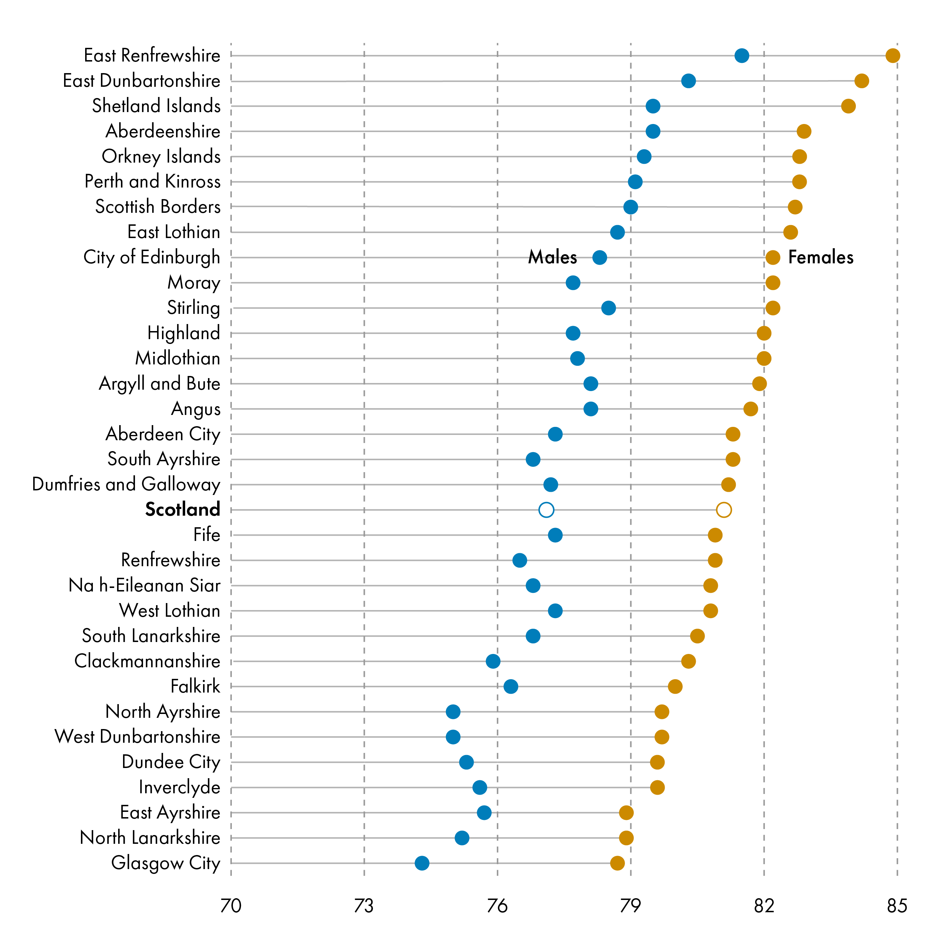

Female life expectancy was higher than male life expectancy in every local authority area across Scotland. Life expectancy was highest in East Renfrewshire at 84.9 (±0.6) years for females and 81.5 (±0.7) years for males. Life expectancy was lowest in Glasgow City, at 78.7 (±0.3) years for females and 74.3 (±0.3) years for malesi.

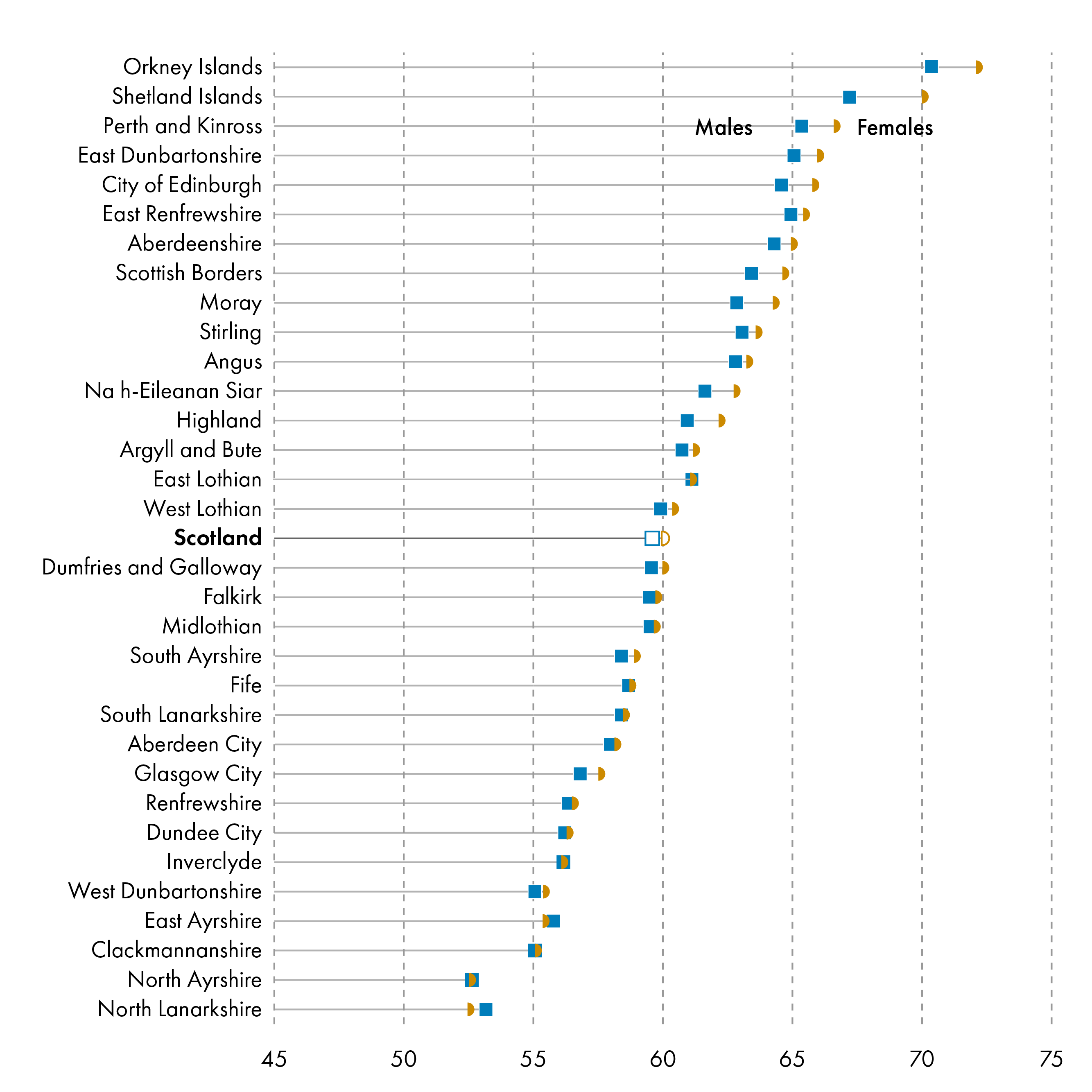

Healthy life expectancy was similar between males and females across local authority areas.

Since 2013, healthy life expectancy has been declining for males and females in Scotland, while life expectancy has remained constant between 2013-2023. The gap between life expectancy and healthy life expectancy is greater for females. It has been increasing over time for females and males in Scotland, meaning that people are living for longer in poor health. In 2021-23, females were expected to live 20.8 years in poor health compared to 18.1 years in 2013-15. Males were expected to live 17.2 years in poor health in 2021-23 compared to 15.2 in 2013-15. This means that females spend a greater proportion of their life in poor health than males.

Socio-economic Differences in Life Expectancy and Healthy Life Expectancy

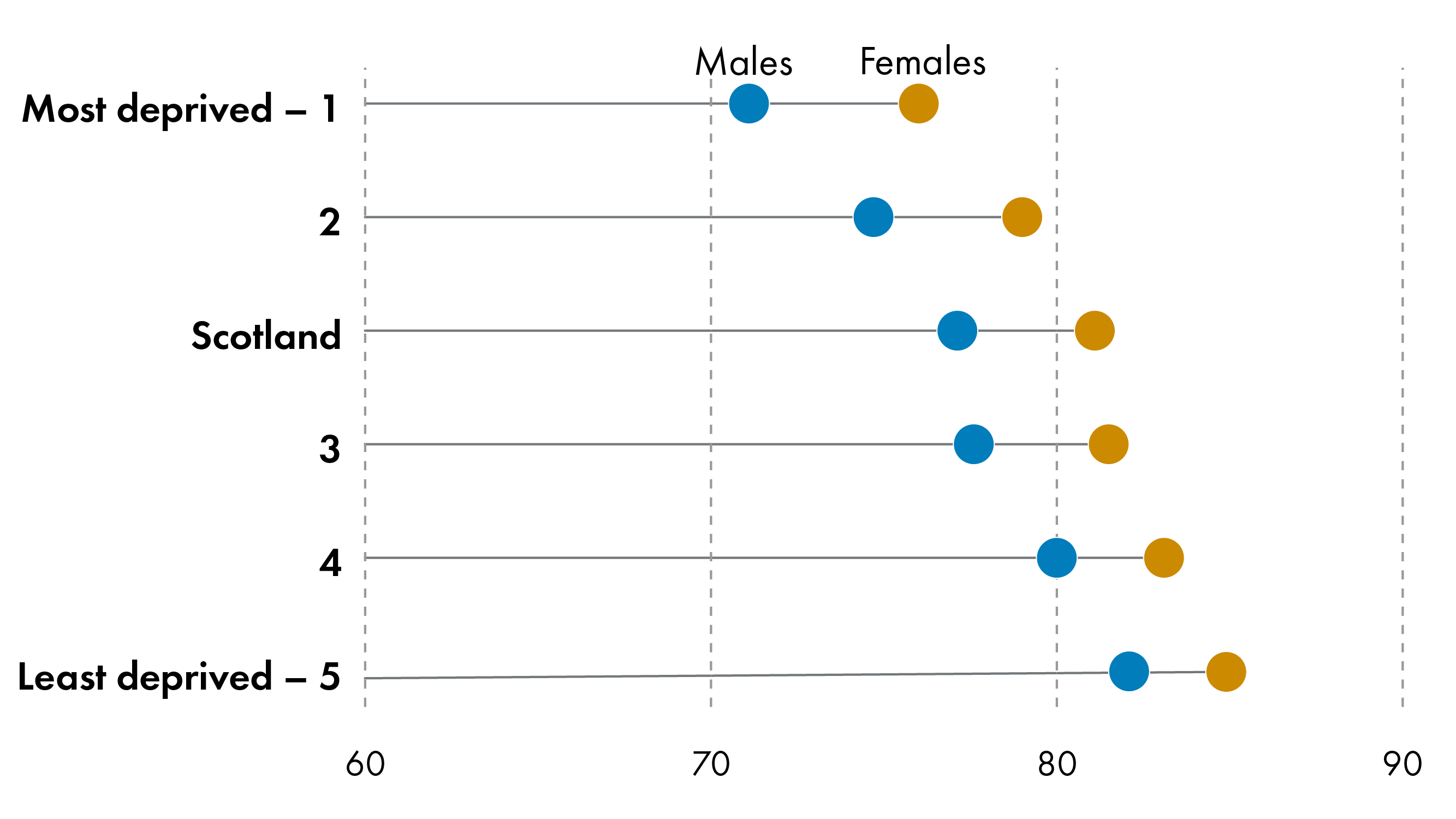

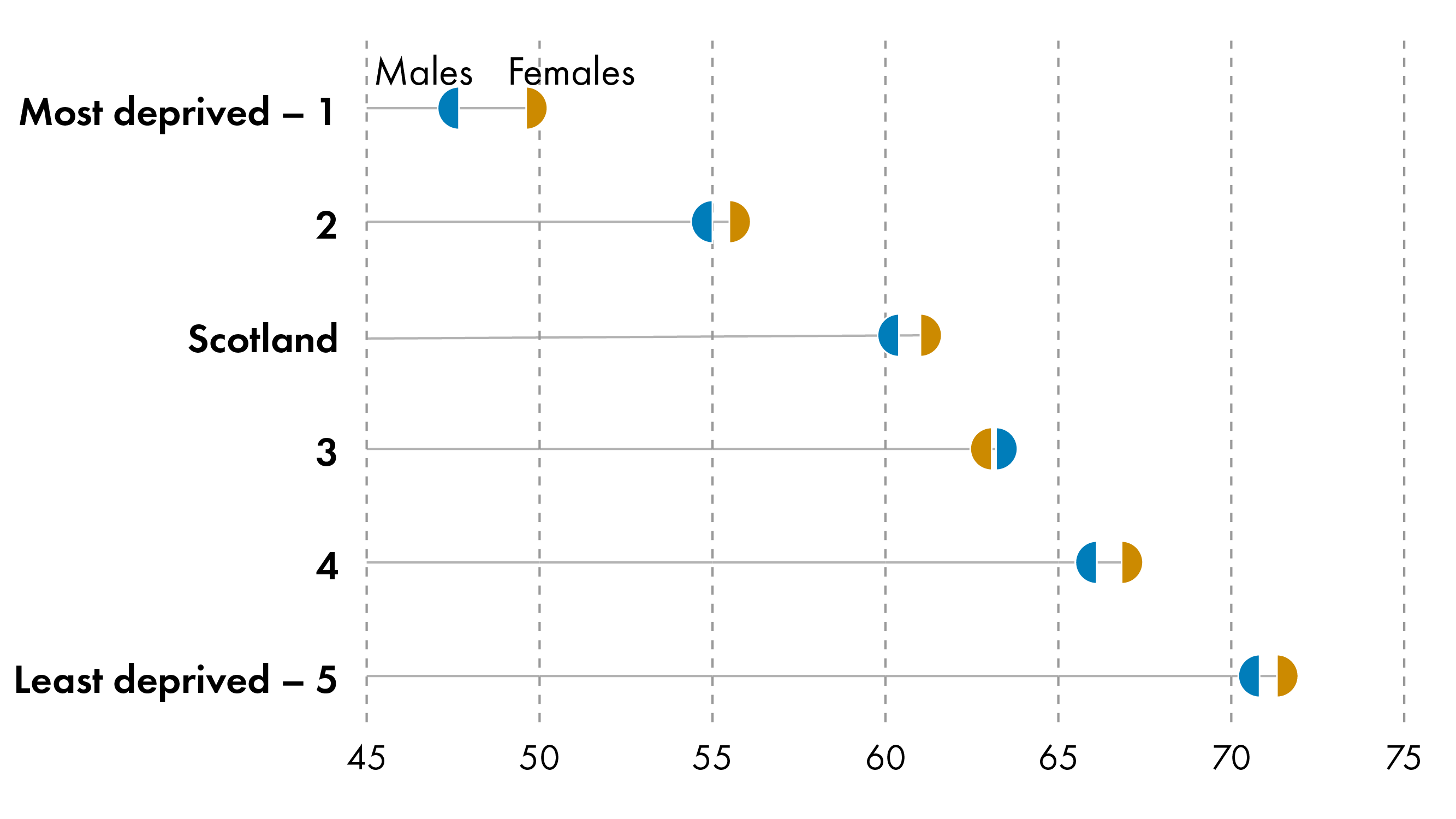

Life expectancy also varies significantly by deprivation. Socio-economic deprivation correlates with reduced life expectancy and healthy life expectancy in Scotland.

People living in the most deprived areas in Scotland can expect to live fewer years - 10 for male and 13 for female - and many more of these years- 23 for male and 24 for female - can be expected to be spent in poor health compared to those living in the least deprived areas- a drastic health inequality.

The Cost of an Ageing Population

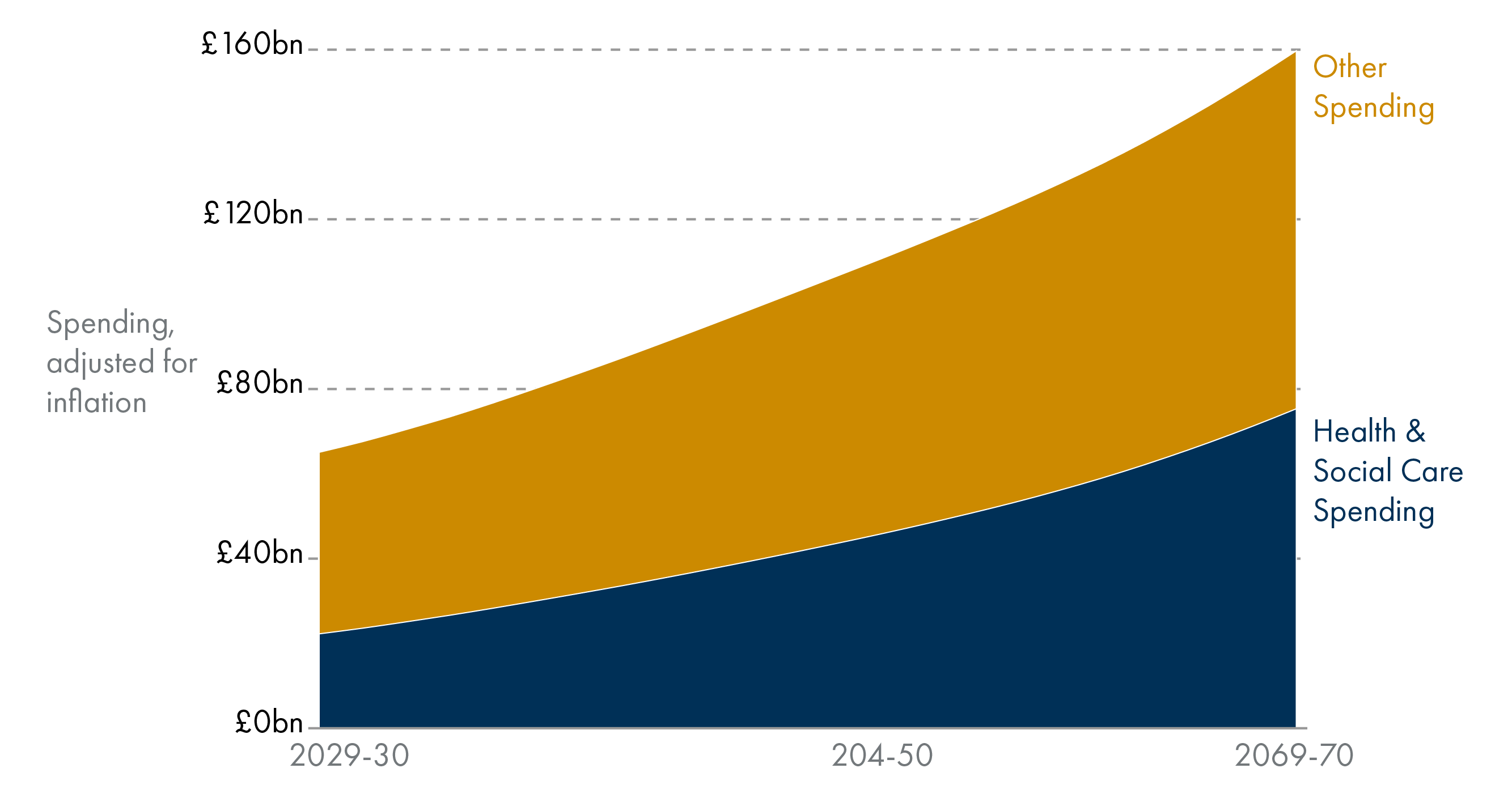

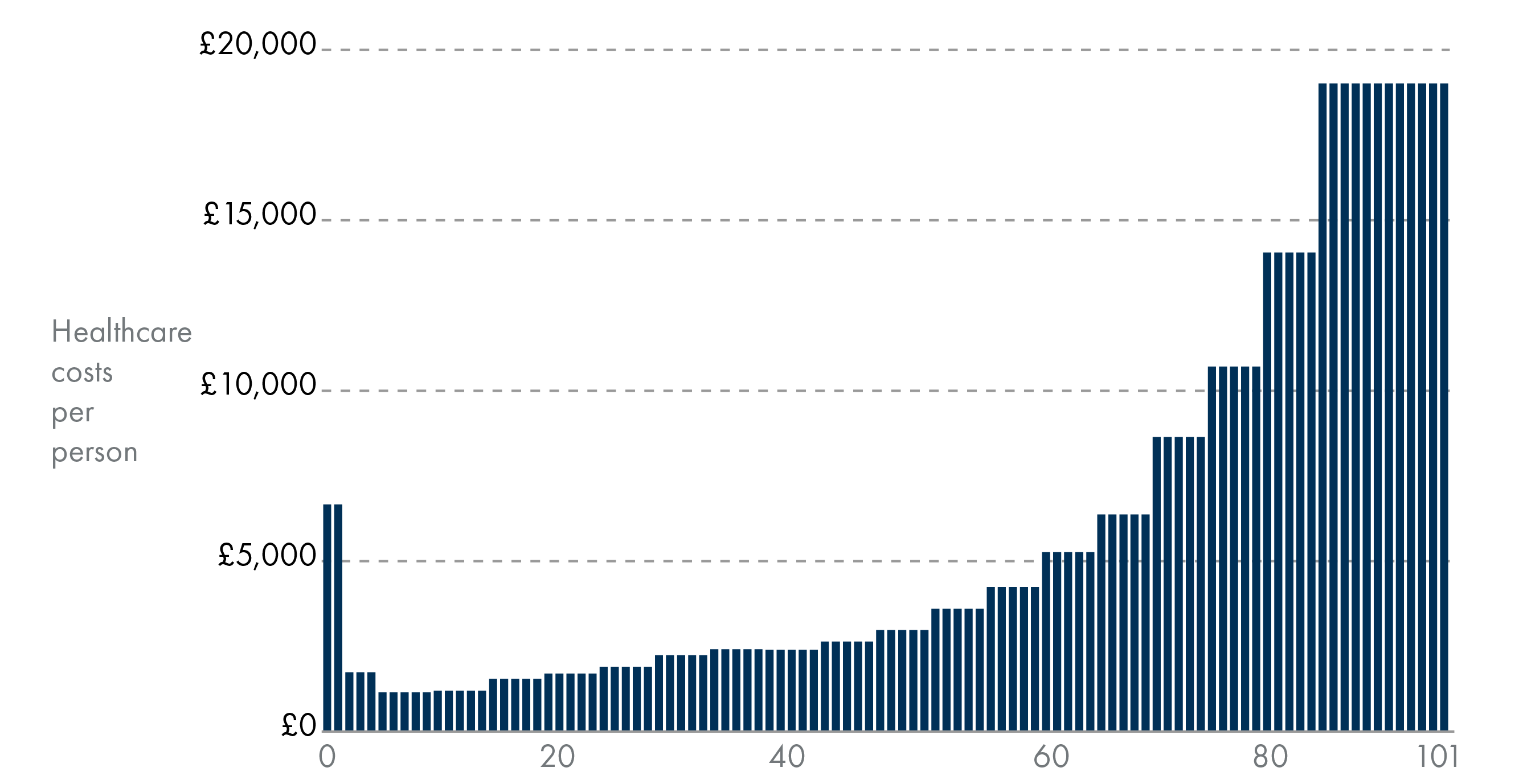

The OBR forecasts that "on current policy settings" the fiscal challenges posed by an ageing society would push borrowing above 20 per cent and debt above 270 per cent of GDP by the early 2070s. Health spending is the largest part of the Scottish Budget and has been growing faster than any other portfolio area1. As Scotland's population is ageing and older people tend to have higher healthcare costs, the amount of health and care expenditure is expected to continue to rise, leading to budget pressures in the future.

Promoting healthy ageing in Scotland is key to reducing health and social care expenditure, and increasing the amount of people who remain active in the labour market and wider economy. Increasing ill health in the population could negatively affect income tax revenue, through rising inactivity, and people in work with a work-limiting illness working fewer hours2.

Health and social care spending is projected to grow as a share of the budget. Based on current trends, health and social care spending is projected to rise from around 40 per cent of Scottish devolved public spending in 2029-30 to almost 55 per cent in 2074-75.

Health and social care expenditure tends to be higher for older age groups. Health spending tends to rise with age, meaning an ageing population could lead to more health spending in the future. Health and social care spending will grow as a share of the budget.

An ageing population brings broader socio-economic costs beyond healthcare, including higher social security (pensions) and social care spending, significant economic losses from unpaid carers leaving work, and reduced labour force participation due to older age and illness2.

The Scottish Fiscal Commission has suggested that improvements to population health could ease fiscal pressures. Healthcare spending could be reduced and people could work for longer, reducing strain on pensions and supporting economic growth. In support of this, the UK Government Economic Affairs Committee report ‘Preparing for an ageing society’ concluded:

The Government response to the rise in the old-age dependency ratio seems primarily focused on improving productivity. The difficulties successive governments have had in raising productivity, as well as the scale of the fiscal challenge of an ageing society, mean that this cannot be the sole policy focus.

According to the compression of morbidity hypothesis, improved population health could also postpone the onset of chronic illness, with morbidity becoming ‘compressed’ into shorter periods just before death. This could lead to reduced healthcare spending. Several studies have confirmed that it is not age per se, but time-to-death, particularly the final year of life, that is a stronger driver of healthcare expenditures. People dying at younger ages (<70 years) have higher healthcare costs, mainly due to increased hospital care, while living for longer is not necessarily a burden on the healthcare system (provided that good health is maintained).

The Ageing Process

Ageing describes a gradual decline in physiological health across an individual's life span, ultimately leading to decreased physical and mental abilities, a growing risk of disease, and eventually death. Healthy ageing can be defined as surviving to the age of 70 years without the presence of 11 major chronic diseases and with no impairment to cognitive function, physical function or mental health12.

Major chronic diseases associated with ageing include cancer, diabetes, myocardial infarction, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, stroke, kidney failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Parkinson's disease, multiple sclerosis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

The rate and type of physiological decline during ageing varies between individuals. While changes such as skin wrinkles and grey hair are well known, ageing can affect many systems of the body, which can causes system-specific clinical problems.

Cardiovascular system

The cardiovascular system includes the heart, blood vessels and blood which works to deliver oxygen around the body.

Age related physiological changes:

Thickening of artery walls

Stiffening of vessels and veins

Increased blood pressure

Maximum heart rate declines

Examples of associated clinical problems:

Changes to normal heart rhythm

Pooling of blood in lower body, particularly legs, causing pain and swelling

Endocrine system (hormones)

The endocrine system is involved in producing hormones (chemical messengers) which regulate functions including metabolism, stress, and reproduction.

Age related physiological changes:

Altered reproductive hormone levels

Menopause in women

Increased levels of insulin

Reduced levels of growth hormone

Reduced levels of thyroid hormones

Examples of associated clinical problems:

Tolerance to glucose is altered

Increased risk of developing insulin resistance (a feature of type 2 diabetes)

Increased breakdown of bone tissue

Gastrointestinal and metabolic system

The gastrointestinal system involves ingestion, digestion, absorption of necessary nutrients and the expulsion of waste. The metabolic system is a feature of this where the body converts our food into energy.

Age related physiological changes:

Slower emptying of the stomach

Raised stomach acidity (pH)

Reduction in liver size

Reduced basal metabolic rate (how many calories your body burns at rest)

Lower energy needs

Examples of associated clinical problems:

Increased risk of acid reflux

Lower absorption of key micronutrients

Reduction in appetite

Constipation

Haematological system (blood)

The haematological system transports oxygen and nutrients around the body while also being important for fighting infection and responding to injury.

Age related physiological changes:

Iron stores decline

Immune cell number is reduced and function is altered

Reduction in the number of stem cells

Examples of associated clinical problems:

Increased risk of bleeding

Slower production of new red blood cells

Increased risk of blood clotting

Immune system

The immune system is the body's line of defence against infection and some diseases. It includes various immune cells and organs including the lymph nodes. The immune system is split into two types: innate immunity and adaptive immunity.

The innate immune system is considered non-specific and responds quickly to infection. The adaptive immune system is a highly targeted response that initially takes time to develop, but will 'remember' a pathogen if encountered again and respond rapidly.

Age related physiological changes:

Function of innate immune cells is reduced

Adaptive immune cells become less effective at responding to infections

Shrinking of the thymus – an organ which is important for producing a type of adaptive immune cell

Increase presence of chronic low-grade inflammation

Examples of associated clinical problems:

Increased risks of infection

Slower recovery from illness

Increased risk of developing autoimmune disorders (e.g. Rheumatoid Arthritis)

Less responsive to vaccines

Increased cell senescence (presence of cells which no longer make new copies but do not die)

Vaccines use harmless parts of pathogens to prime the adaptive immune system, and are important for improving immune defence in people aged over 65 years old.

Musculoskeletal system

The musculoskeletal system includes the muscles, joints, and bones and collectively these help us to move freely and provide structure to our body.

Age related physiological changes:

Declines in muscle mass and strength

Slower recovery of muscles

Increased fat mass

Loss of bone mass

Reduction in joint cartilage

Examples of associated clinical problems:

Osteopenia and osteoporosis – low bone density

Osteoarthritis – cartilage between joints is worn down

Nervous system

The nervous system is the control centre of the body which acts by signals being released from the brain, which can then instruct other areas of the body.

Age related physiological changes:

Loss of neurons (nerve cells)

Production of neurotransmitters (brain signals) is reduced

Speed of cognitive and physical tasks declines

Examples of associated clinical problems:

Shrinking of the brain

Slower reaction times

Difficulties with memory, attention and quick thinking

Changes in mood

Impaired vision

Loss of hearing, particularly high tone sounds

Skin

The skin is the largest organ of the body and provides protection from infection and injury but also helps to regulate body temperature.

Age related physiological changes:

Loss of skin elasticity

Barrier function of the skin is reduced

Changes to the structure and composition of hair fibres

Examples of associated clinical problems:

Wrinkles and changes to skin pigmentation

Less effective at healing wounds

Increased skin injuries (e.g. bruising)

Changes to body temperature

An in-depth explanation of the physiology of ageing can be found here.

Measuring Ageing

While chronological age measures the number of years since birth, biological age describes the rate that the body itself is ageing1. Growing evidence suggests people biologically age at different rates, affecting their quality of life2 and disease-risk.

The pace at which an individual biologically ages is influenced by a combination of personal characteristics, their physical environment, social interactions, and, to a lesser extent, their genetic make-up3.

People who biologically age at a slower rate will generally experience good health and a higher quality of life in older chronological age. People who biologically age at a faster rate will generally experience a deterioration in health and increased risk of age-related disease and frailty in older chronological age.

Ageing has been shown to be a non-linear and non-consistent process, with recent research demonstrating two dramatic 'bursts' of ageing at 44 and 60 years of age5. The first stage (mid-40s) primarily impacted molecules associated with cardiovascular health and the way in which the body breaks down alcohol, caffeine, and fats. The second stage (early 60s) was found to feature changes in molecules governing immune function, carbohydrate metabolism, and kidney function. Molecules linked to skin and muscle ageing changed across both time points. How the rate of ageing impacts these two phases of ageing is currently unknown.

Scientists have developed many ways to measure biological age that range from simple measures, such as grip strength or standing on one leg, to complex measures taken from blood samples such as DNA, RNA, proteins, and metabolites.

Ageing Clocks

Measures that affect the biological hallmarks of ageing can be used to generate computational models called ageing clocks that quantify a person's biological age. The first ageing clocks modelled epigenetic alterations (changes in gene function, without changes to the base sequence of DNA)12. Ageing clocks have now been built from many different types of data3. Ageing clocks can estimate the rate of ageing, which is the difference between a person's chronological age and their clock biological age.

Ageing clocks can be used to test the efficacy of anti-ageing interventions that aim to "rewind the clock" by targeting the biological hallmarks of ageing4. Lifestyle modifications, such as eating healthily56 or increasing physical activity78, have been shown to slow the rate of ageing calculated with ageing clocks in human clinical trials. A recent study linked creative engagement to protective brain health during ageing, as measured by "brain clocks"9. Researchers identified a disparity in brain age as compared to chronological age in creative experts (e.g. tango dancers, musicians, visual artists, and gamers), particularly in regions of the brain most vulnerable to neurodegeneration9.

Early results from human clinical trials suggest that ageing clocks can be used to test the efficacy of anti-ageing drugs with the potential to reverse biological ageing11; however, larger trials are needed to confirm these observations (discussed here).

Current research on ageing clocks is utilising recent developments in artificial intelligence and deep neural networks to better capture the intricate nuances of ageing1213. These clocks enable the quantification of biological age from many different biological age measures, and can include longitudinal measures, increasing the accuracy of biological age calculations.

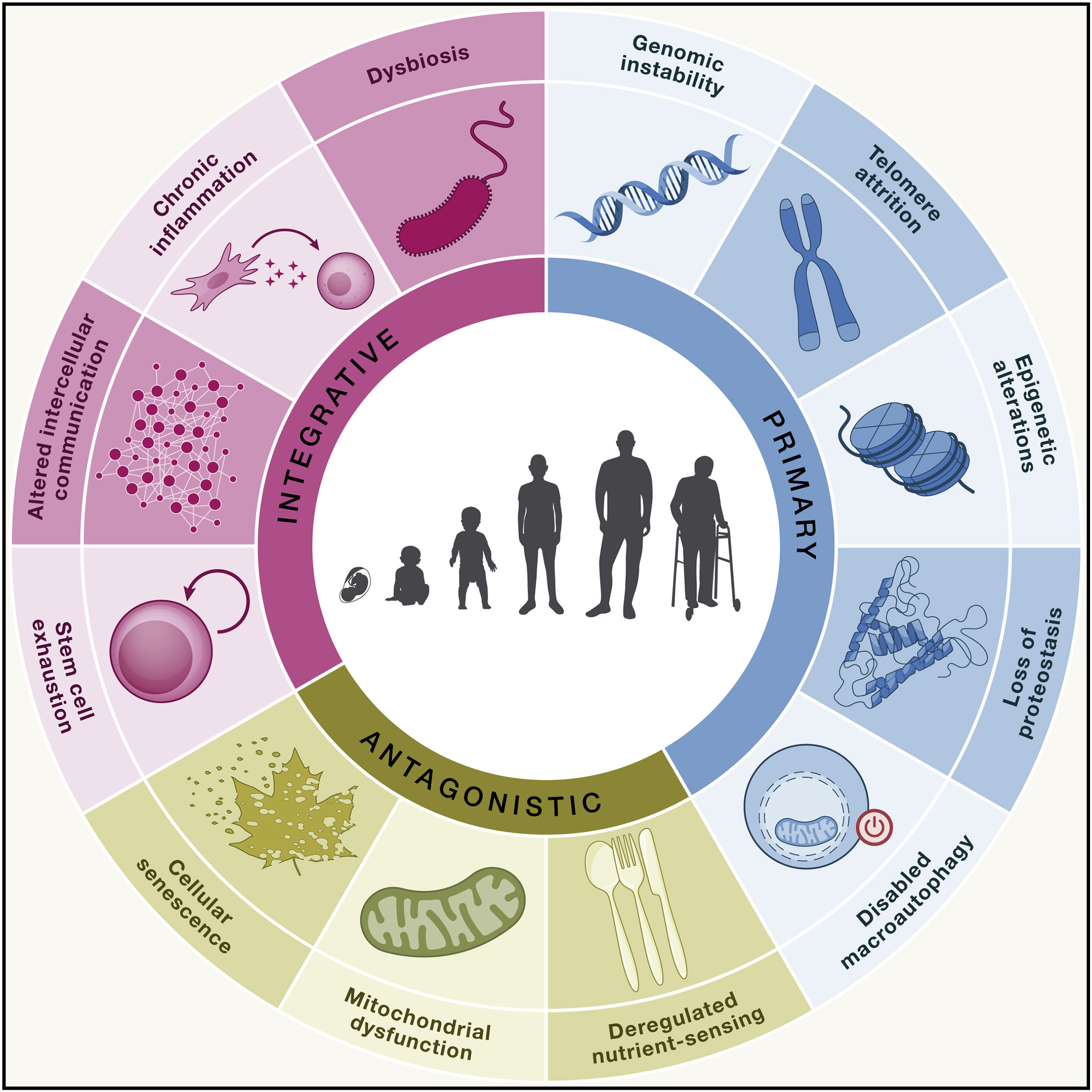

Biological Hallmarks of Ageing

At the biological level, ageing is caused by the accumulation of a wide variety of molecular and cellular damage over time.

12 distinctive biological hallmarks of ageing have being described (and recently an additional two have been suggested1), with each hallmark fitting the following criteria2:

The hallmark must occur in the naturally ageing body

Accelerating the hallmark should also accelerate ageing

Slowing it down or getting rid of the hallmark should slow ageing down and improve overall health

1. Genomic instability

Over the life course, instruction manuals within each cell (encoded in DNA) accumulate damage from external (e.g. UV radiation from the sun) and internal factors (e.g. errors during cell division). Accumulating errors caused by genomic instability is also a hallmark of cancer, a disease strongly associated with age.

2. Telomere attrition

A telomere is a protective cap found on the end of chromosomes (compact structures that contain our cells information). As cells make new copies of themselves, a small section of the telomere is lost. This means that over time, these protective structures shrink. Telomerase is an important enzyme that can help prevent shortening, but most cells in the human body do not contain telomerase. Therefore, when telomeres become too short the cell is no longer able to make new copies. Under normal circumstances this would cause the cell to die, however it can also cause them to become senescenti2.

3. Epigenetic alterations

Epigenetic alterations (e.g. DNA methylation patterns) are changes to the instruction manuals within each cell in the body that are caused by a person's environment and habits. Epigenetic changes do not change the sequence of DNA bases, but they can change how a DNA sequence is read. Examples of environmental influences that affect epigenetic patterns include smoking, alcohol consumption, dietary choices, exercise, and stress. These factors can cause certain instructions to be switched on or off, which in turn can lead to changes in the way our cells behave.

Epigenetic alterations during ageing impact the development and progression of several age-related human pathologies, such as cancer, neurodegeneration, metabolic syndrome, and bone diseases2.

The impact of epigenetic alterations on health can be either positive or negative depending on the environmental stimulus. Exercise induces epigenetic changes associated with decreased risk of metabolic disease6. In comparison, smoking induces epigenetic changes that promote the risk of developing several diseases including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)7. Vaping has also be found to induce similar epigenetic changes as those seen with traditional cigarettes, suggesting continued risk of developing pulmonary diseases8.

As epigenetic changes are mostly considered to be reversible, promoting healthy living is a key area for improving age-associated health outcomes.

4. Loss of proteostasis

Proteostasis is the process of monitoring the number, shape, and function of our proteins 9. This is essential for cells to function and survive normally. During ageing, proteostasis becomes less efficient which results in an increased number of damaged or misshapen proteins (each protein has a specific folding pattern)2. These damaged proteins can join together to form aggregates, which have been shown to block cellular function, contributing to the progression of various diseases such as Parkinson’s disease 11. Targeting the formation of these aggregates has been identified as a promising target for therapeutic intervention2.

5. Disabled macroautophagy

Macroautophagy is a cellular process where the insides of a cell are broken down and recycled. The process of a cell eating itself allows damaged parts to be reused but can also provide cells with energy when they are experiencing stress 13. During ageing, macroautophagy naturally declines and it is thought that this may be caused by macroautophagy instructions being switched off, cells no longer sensing nutrients properly, or mistakes occurring during the macroautophagy process. This can cause cells to retain damaged parts which can become toxic to the cell itself but can also lead to the cell producing signals that trigger low grade chronic inflammation.

Calorie restriction and GLP-1 medicines have been shown to boost macroautophagy1415.

6. Deregulated nutrient sensing

Nutrient sensing is an important process, where cells can recognise and react to nutrients in their environment. This allows the body to regulate metabolism, which refers to how energy from food is processed, stored, and used to support essential functions such as growth, repair, and movement. Nutrient sensing ensures the body is able regulate itself during normal day-to-day conditions but also during periods of food abundance or scarcity 16.

There are two key signalling pathways that are triggered when the body senses available nutrients including mTOR and IGF-1 17. Under normal physiological conditions, these pathways help control metabolic processes such as glucose uptake, fat storage, and protein synthesis. Studies have shown that ageing is accelerated the more these signalling pathways are activated. This is thought to be caused by these pathways being either constantly ‘switched on’ and/or due to these pathways becoming less responsive to available nutrients2. When nutrient sensing becomes deregulated, the normal metabolic balance is disrupted. This can lead to inefficient energy use, increased fat accumulation, and reduced ability to repair cellular damage19 .

Elderly people are susceptible to viral respiratory infections. Treating elderly volunteers with a metabolic inhibitor (targeting mTOR) improved their response to the influenza vaccine20 and reduced viral respiratory infections the following winter21, highlighting a key link between deregulated nutrient sensing and immune system function during ageing.

Individuals from deprived areas can be metabolically disadvantaged as a result of lack of accessibility to healthy food options and reduced levels of activity14. Over time, these metabolic imbalances place stress on cells and tissues, accelerating the rate of ageing. Socio-economic deprivation has been associated with an increased incidence of infection and poorer clinical outcomes during influenza pandemics and the COVID-19 pandemic23.

7. Mitochondrial dysfunction

Mitochondria are highly dynamic organelles that are vital for maintaining cellular energy balance through the synthesis of Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP) - the energetic currency of the cell. Mitochondrial dysfunction occurs when mitochondria fail to function normally, and this can be driven by changes to the mitochondria’s specific set of instructions, inefficient monitoring processes, cellular senescence, and increased production of reactive oxygen species 24. Mitochondrial dysfunction can impact a cell's metabolism, growth, and survival. Studies in mice have suggested mitochondrial dysfunction in immune cells can accelerate ageing and senescence across multiple organs and tissues 25. The specific factors that cause mitochondrial function during ageing are currently unknown.

8. Cellular senescence

Cellular senescence is a state in which cells are no longer able to divide but continue to survive and release harmful molecules, known as the senescent-associated secretory phenotype (SASP)26. The SASP acts on the local tissue environment, but it can also spread throughout the body and impact cells and tissues at a distance27.

Cellular senescence can be caused by various stressors including persistent damage to cell instructions or telomere dysfunction2.

Scientists have found several biomarkers for senescent cells including senescence-associated-β-galactosidase activity, increased levels of proteins which slow or stop the cell-cycle, and increased levels of cell survival proteins2. These biomarkers are an area of interest for therapeutic intervention, leading to the creation of senolytic drugs that selectively clear senescent cells in an effort to prevent age-related diseases.

9. Stem cell exhaustion

Stem cells are specialised cells that have the capacity to develop into various cell types. They are known to play important roles in tissue maintenance and repair 30. Progressive loss of stem cell number and function is referred to as stem cell exhaustion and it can be caused by various other age associated hallmarks such as telomere attrition, epigenetic alterations, genomic instability, and pro-inflammatory signals received from senescent cells2.

In 2012, Shinya Yamanaka won a share of a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering amix of proteins that reprogrammed adult cells into pluripotent stem cells. In 2023, two independent research teams demonstrated that this mix of proteins could be used to reverse ageing in mice, including restoration of age-associated epigenetic changes. More research is needed into the mechanism of the protein mix before this can be tested in humans.

In elderly humans, stem cell exhaustion has been linked to declines in tissue repair and musculoskeletal diseases32. Loss of specialisation abilities and increased levels of senescence proteins is found in stem cells from older donors 33. These differences were found to impact new bone formation33, and has therefore been linked to the development and progression of osteoporosis - a common disease in ageing women.

10. Altered intracellular communication

Cells undergo constant communication with other cells and tissues to ensure the coordination and maintenance of the body. This communication allows cells to grow, repair damage, and be removed when they are no longer functioning properly. Intracellular communication can occur in cells in close contact or with cells at a distance by various signalling pathways, such as the production of chemical messengers. During ageing, there are low levels of continuous inflammation (see below: chronic inflammation) which can influence a cells behaviour leading to the release of damaging or inappropriate signals2.

Cellular communication can also be disrupted in aged individuals by the increased presence of senescent cells. Normally, the immune system aims to identify and remove these damaged or senescent cells. However, altered intracellular signalling during ageing can impair this process, meaning the immune system does not efficiently clear these cells. As a result, senescent cells accumulate and continue to send harmful signals that promote inflammation, tissue damage and disease (see: cellular senescence).

11. Chronic inflammation

Inflammation is a regulated local response to injury or infection, but chronic inflammation, also referred to as "inflammageing", is a persistent, low-grade version of inflammation associated with ageing36. Inflammageing can impair the body’s ability to effectively respond to infections and repair damaged tissues, while simultaneously exposing tissues to prolonged stress and contributing to senescence36.

Individuals from lower socio-economic backgrounds are more likely to experience long-term stress, poorer diet quality, and reduced access to healthcare14. Over time, these factors can accelerate inflammageing, contributing to health inequalities and increasing the risk of age associated diseases later in life14.

Chronic inflammation is closely linked to the other hallmarks of ageing, including genomic instability, defective macroautophagy, epigenetic alterations, deregulated nutrient sensing and cellular senescence2.

12. Dysbiosis of gut microbiota

Living within the gut are trillions of microbes (bacteria, viruses, fungi, and microorganisms) which form a complex ecosystem called the microbiota to support gut health, metabolism, and immune function. Over recent years, the importance of gut health for overall health has been realised, as individuals with higher gut biodiversity, influenced by a diverse and healthy diet, have positive associations with health 41.

There are changes to the gut microbiota and eating habits across the lifecourse. In older individuals, or those who consume a nutrient poor diet, the number of healthy gut microbiota declines while the number of harmful gut microbiota increases2. This leads to an imbalance known as dysbiosis. In response, signals are produced which can drive local and whole-body inflammation, in turn contributing to other hallmarks of ageing2.

Dysbiosis of gut microbiota has been linked to various diseases including gastrointestinal (e.g. inflammatory bowel disease), neurological (e.g. Alzheimer’s disease) and metabolic (e.g. obesity) disease, as well as frailty in the elderly4445. The link between gut and cognitive health is an emerging area of interest and shows great promise in being a modifiable risk factor (e.g. through dietary intervention) to minimise cognitive decline 46. Excessive consumption of total and processed meat has been associated with cognitive impairment 47, and Public Health Scotland reported people from the most deprived socio-economic groups consumed more red and red processed meat (44%) compared with the least deprived socio-economic group (31%), contributing to the health-related disparities observed across socio-economic groups.

Recently suggested hallmarks

13. Extracellular matrix changes

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is a complex non-cellular network that surrounds cells within tissues to provide structural support, helps to organise cells and aids cellular communication 48. During ageing, the ECM undergoes breakdown, compositional and biomechanical changes which ultimately impacts the way our cells and tissues behave 1. This can lead to the development of senescent cells which in turn can promote further ECM changes through the release of inflammatory and tissue remodelling factors, creating a ongoing cycle of damage 50.

During ageing, the ECM is subject to increased ‘stiffness’51. This occurs due to the accumulation of altered structural proteins and less efficient tissue repair. Increased ECM stiffness changes the physical environment of cells, impairing their ability to sense and respond appropriately to mechanical cues48. The progression of cardiovascular, kidney, and pulmonary diseases has been attributed in part to ECM changes due to their role in disrupting normal tissue function51.

For ECM changes to be confirmed as a hallmark of ageing, more research is needed to test whether modifying the ECM slows ageing down and improves overall health.

14. Social isolation

The presence of healthy and meaningful social relationships is being recognised as an indicator of good quality living and has significant links to better mental health outcomes. Social isolation occurs when there is a lack of meaningful social connections, and it can be coupled with lacking a sense of ‘belonging’. Social isolation has been shown to accelerate biological ageing in older adults54, and has been associated with mortality even after other contributing factors such as baseline physical health have been accounted for 55. Integrating strong social connections is a common thread mentioned among centenarians 1457, linking social connections to healthy ageing.

The Benefits of an Ageing Population

As outlined in the Chief Medical Officer for Scotland Annual Report 2024-2025 there are benefits of an ageing populations and broader societal benefits of promoting healthy ageing . Old age is a meaningful time in people's lives, often giving them time to connect with their spouse, friends, and family; learn new skills; and pursue personal interests. Older people contribute to intergenerational communities through their experience, wisdom and skills. People aged over 50 years old are the most likely to volunteer, vote and provide unpaid care, including childcare that supports the economic contributions and well-being of younger generations. However, caring responsibilities is also one of the main factors limiting people's participation in the workforce.

A recent report published by the UK Parliament Economic Affairs Committee found no evidence of systematic differences between older and younger workers as far as productivity is concerned in the majority of types of work. Furthermore, an older workforce might have additional benefits, for examples older people have been shown to form strong relationships that can support younger colleagues through their experience, coaching and mentorship. By 2035, workers over 50 years old are projected to generate nearly 40% of all earnings, suggesting that older workers will make an important contribution to the workforce.

Despite the benefits of an ageing population, personal barriers such as poor health, and environmental barriers such as a lack of public services, shortages in suitable housing, and ageism can hamper the continued participation of older individuals in society. Recent findings suggest that self-directed age discrimination can also hamper decision making in older workers, for example by mistakenly perceiving ageism in colleagues.

The UN Decade of Healthy Ageing (2021–2030) aims to give everyone the opportunity to add life to years by focusing on four key action areas:

Change how we think, feel and act towards age and ageing.

Ensure that communities foster older people's abilities.

Deliver person-centred integrated care and primary health services that respond to older people's needs.

Provide access to long-term care for older people who need it.

Health Inequalities in Healthy Ageing

As explored earlier in this briefing significant health inequalities exist in healthy ageing and healthy life expectancy. The Scottish Government and the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities (COSLA) have outlined their long-term collective approach to improving Scotland’s health and reducing health inequalities for the next decade, in the joint publication Scotland's Population Health Framework. This has the aim:

By 2035 we will improve Scottish life expectancy whilst reducing the life expectancy gap between the most deprived 20% of local areas and the national average

The initial priorities of the framework are:

Embedding Prevention in our Systems

Improving Healthy Weight

The framework advocates for a life course approach which recognises that "actions that improve the building blocks of health will create health, not just prevent disease. Activities which strengthen the building blocks of health make a difference across the life course, from pre-birth to adolescence to working-age and older age".

It goes on to note that "adopting a life course approach is about addressing the protective and risk factors relevant to health and wellbeing at each stage of life. Such an approach recognises the importance of focusing and tailoring different health and wellbeing efforts to improve population health and reduce inequalities at all ages".

The evidence paper for the Population Health Strategy advocates for an whole system approach, which recognises that there is no single solution to address complex public health issues and that a coordinated and collaborative approach is needed. It goes on to note that "evidence shows that structural interventions – designed to address the complex system of influences that shape behaviours and improve the circumstances in which people live – are the most effective in improving health and reducing health inequalities".

Despite there being limited evidence to suggest that individual behavioural interventions have an impact on health outcomes at a population level, it does note that "evidence shows that where the risks associated with specific behaviours are particularly high (e.g. smoking, poor diet, and alcohol misuse), or where habitual behaviours create resistance to change, it is important to consider the cumulative effect of policies".

Healthy Ageing

Although a person's genetic make-up plays a role in healthy ageing, a much greater contributor is their physical and social environment, as well as their personal characteristics1. The environment that people live in as children (and even as a foetus) strongly affects how they age over their life course1. Health inequalities during ageing arise due to the strong environmental impact on the rate of biological ageing, including where a person lives, their income, access to nutritious foods and physical activity opportunities3.

The goal of healthy ageing is to increase the number of years spent in good health, which can improve people's quality of life, their capacity to work, and their ability to remain active in the economy, while easing strain on the NHS.

Healthy ageing challenges the traditional view that ill health and disability during ageing are inevitable, as demonstrated by many examples of healthy people in their 90s and 100s4.

Experts have highlighted the need for policy interventions that support active and disease-free ageing, encourage independence in later life, maintain brain health and reduce social isolation.

There are a number of interventions, such as good nutrition and physical activity, that help people age well. The basis for these recommendations is considered in more detail below.

Eating Well

A healthy diet throughout life positively affects the hallmarks of ageing and is a key determinant of healthy ageing12. Dietary lifestyles determined during childhood and maintained in adulthood strongly affect healthy life expectancy 34. However, the quality of diet in older age is also an important determinant of health, well-being, functional ability, mobility and independence.

Eating more fruits, vegetables, whole grains, unsaturated fats, nuts, legumes and low-fat dairy products was linked to healthy ageing in a recently published study following more than 105,000 people over 30 years in the US. As well as analysing individual dietary components (e.g. fruits), the study measured adherence to eight dietary patterns, including the Mediterranean Diet, Alternative Healthy Eating Index, and Planetary Health Diet Index, which were all positively associated with healthy ageing. Diets with more trans fats, sodium, sugary beverages and red or processed meats were linked to unhealthy ageing. Similar associations between dietary patterns and healthy ageing have also been reported in France5 and Australia6, although there are variations in the study designs.

Eating a healthy diet is very important for older adults, who are at higher risk of malnutrition - deficiencies or excesses in nutrient intake, imbalance of essential nutrients, or impaired nutrient utilisation. In Scotland, at least 1 in 10 older people are at risk of or are living with malnutrition. Prevalence of malnutrition is higher in women, people aged over 80 years, and people affected by chronic illness7.

The double burden of malnutrition consists of both under-nutrition (leading to frailty) and over-nutrition (leading to overweight and obesity), which is being increasingly recognised in older people. Malnutrition in older people can lead to frailty, delirium, decreased immune function, muscle wastage, hypothermia, osteoporosis, cognitive impairment, lowered quality of life, and premature mortality89. Many pre-existing conditions are exacerbated by malnutrition10.

A focus of the Scottish Government is to "develop a whole system approach to improve food environments; ensure a healthy, balanced diet is accessible and affordable to all; and improve population levels of healthy weight". How these policies affect people at different stages of the life course will need to be evaluated to establish whether specific policies are needed to improve healthy eating in older adults.

Eat Well Age Well

Eat Well Age Well is a national project funded by the Scottish Government and People's Postcode Lottery aimed at preventing, detecting, and treating malnutrition among older people living at home in Scotland. The project offers training, information on screening for malnutrition, and has developed resources, including an Eat Well Age Well Advice Line and Malnutrition Toolkits11.

Eat Well Age Well is run by the charity Food Train, which has been working with older adults in Scotland offering practical help to eat well, age well and live well at home for longer.

It advocates for:

Ring-fenced Funding for Community-Based Food Access for Older People

A Right to Food for Older People

Investment in Volunteers and Community-Led Support

The launch of a National Malnutrition Prevention and Screening Programme

The involvement of older people in food and health policy design

Reducing Obesity

Obesity is one of the leading causes of poor health across the life course, contributing to age-related diseases and premature death. Obesity and ageing are interrelated public health concerns; however, they are not currently considered as such. Obesity accelerates the biological hallmarks of ageing across all age groups123. It is thought that increased low-grade inflammation and oxidative stress in obese individuals leads to the accumulation of DNA damage and cell senescence, thereby accelerating the ageing process.

In children and young adults, obesity has been linked to early development of age-associated diseases such as type II diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and some cancers456. In older adults, obesity has been shown to exacerbate mobility limitations, cognitive decline, and reduced quality of life6.

Keeping Active

Engaging in regular moderate-intensity physical activity mitigates multiple hallmarks of ageing and encouraging physical activity is a key strategy for promoting healthy ageing across the life course1.

Physical inactivity (doing less than 30 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity per week) is recognised as a leading cause of premature death in Scotland and a leading modifiable risk factor for non-communicable diseases such as cardiovascular disease and cancer2. An estimated 11,474 disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), a key proxy for measuring unhealthy ageing, are attributable to physical inactivity2. Physical inactivity increases with age, and is particularly high in older women (over 75 years)4. The cost of physical inactivity to the NHS in Scotland is estimated at more than £77 million per year, or around £14.60 per person living in the country5.

More than 80% of premature deaths and DALYs are due to the 'very low' physical activity category - those doing less than 30 mins/week of moderate physical activity per week, highlighting the necessity of targeting these individuals with specific interventions2.

A recently published study that followed 13,547 elderly women in the US over 10-years found achieving more than 4000 steps per day (less than 2 miles) on 1-2 days per week was associated with a significantly lower risk of death and lower risk of cardiovascular disease, compared with not reaching this level on any day7. They found a 26% reduction in mortality if people took more than 4,000 steps one or two days per week, and a 40% reduction if people completed the steps less than three days per week7. These findings indicate that small changes to the amount of exercise per week in the most physically inactive individuals could have major benefits to non-communicable disease risk and premature death.

To ensure participation in physical activity in older individuals, a life course approach is needed to set good habits early, maintain good habits through middle-age, and prevent age-associated physical changes such as loss of muscle strength, bone health and the ability to balance. In Blue Zones, regions with a high concentration of centenarians, people were found to have high level of physical activity that was incorporated into their daily routines9.

Participation in physical activity and sports during early childhood and adolescence are important predictors of adulthood physical activity or inactivity10. Pregnancy, menopause, retirement, becoming a carer, and hospitalisation have all been suggested as important periods for change in physical activity behaviour11. Research into the specific barriers that individuals face at these life-stages is needed to establish public health efforts to remove such barriers.

To improve physical activity in older individuals a shift in policy and practice is needed. Older individuals have specific physical activity needs. Activities that improve strength, balance and flexibility are particularly critical in older individuals as they help maintain physical function and reduce the risk of falls. In Scotland,30% of people aged 65 and over will fall at least once a year, rising to 50% for those aged 80 and over. Loss of muscle strength is the primary limiting factor for functional independence, rather than aerobic physical activity12. However, the majority of physical activity in individuals aged over 65 years is from walking, which is not recommended by the UK Chief Medical Officer's activity guidelines as a strengthening activity. This is a particular challenge for women who on average have lower muscle strength than men and fall below important thresholds of strength needed for independence earlier1314.

Recent research from Age Scotland found “health issues, feeling unfit, fear of injury, lack of time, cost concerns, embarrassment and intimidation” were cited as barriers to older people undertaking exercise. Effective promotion of exercise and sport participation should consider these barriers and what motivates older people to exercise, which has been shown to differ between young and old adults15. A tailored exercise campaign to specific age groups and genders could be a relatively cost-effective way to increase physical activity in Scotland.

Maintaining Social Connections

Loneliness and social isolation are significant issues in Scotland, affecting about 1 in 10 individuals. Social isolation has been shown to accelerate biological ageing in older adults1, and has been proposed as a hallmark of ageing2. Reducing social isolation may be important for achieving healthy ageing; however, there is conflicting evidence on whether loneliness and social isolation are causally associated with unhealthy ageing.

Social isolation: the lack of social contacts and having few people to interact with regularly

Loneliness: the distressing feeling of being alone or separated3

While loneliness and social isolation can affect anyone at any point in their life, older adults are particularly susceptible, often due to factors like declining physical strength, losing their central role in the family, retirement, the loss of loved ones, or health challenges3. A combination of these factors can lead to people spending an increasing amount of time alone as they get older. People aged 60 and over were also disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 pandemic as they experienced the biggest increase in loneliness compared to other age groups. Social isolation affects reliance on health and social care services5. Older people living alone have been reported to be more likely to access emergency care services (50%), and be more likely to have more than 12 GP appointments over a year (40%)6, demonstrating an increased healthcare burden.

The impact of loneliness and social isolation on physical and mental health across the life course is incompletely understood. Several studies observational have suggested that loneliness is associated with an increased risk of age-associated diseases, including cardiovascular disease, stroke, and dementia; and can increase the risk of frailty and early mortality78. However, a recent UK Biobank study found that while loneliness was linked to increased risk for 30 out of 56 diseases, loneliness was only causally linked to 6 diseases (hypothyroidism, asthma, depression, psychoactive substance abuse, sleep apnoea and hearing loss). These findings suggest that loneliness does not directly cause diseases such as cardiovascular disease. Further research will improve understanding of causality.

To tackle loneliness and social isolation in Scotland, the Scottish Government developed a national strategy, A Connected Scotland, in 2018. While most of the priorities focus on a whole population approach to tackle social isolation and loneliness, older adults are specifically mentioned in Priority Three, which aims to promote physical activity in older adults to help maintain mobility and self-sufficiency for longer. In support of this, research suggests involvement in physical activities including sport can have a significant positive effect on loneliness and social isolation910.

Reducing Alcohol Consumption

Consumption of alcohol has been strongly linked to biological ageing in studies carried out in the UK and US. Considering the impact of Scotland's alcohol consumption on the rate of biological ageing is essential given the 2025 report from Public Health Scotland stating "people in Scotland are drinking 50% above safe limits, with more deprived communities hit hardest".

The type, frequency, and quantity of alcohol consumption affects the rate of biological ageing. Precisely how alcohol affects biological ageing is unknown; however, researchers at the University of Oxford found that the more people drank, the shorter their telomeres - one of the hallmarks of ageing. It is thought that alcohol increases the levels of oxidative stress and inflammation, leading to DNA damage and telomere shortening. A study using data from UK Biobank and Generation Scotland found that alcohol consumption positively associated with two DNA methylation-based ageing clocks.

While alcohol consumption generally impacts biological ageing, spirits had an approximately two and a half times greater effect than beer consumption. Daily consumption of spirits for five years was associated with a four-month acceleration in biological ageing, while one episode of binge drinking (consuming five or more drinks on the same occasion) was associated with a month and a half acceleration in biological ageing. Consumption of wine did not affect biological age; however, a recent study on 2.4 million participants linked consumption of any alcohol (including wine) to increased risk of dementia. Given the strong association between age and dementia this study indicates that more research into the impact of wine consumption on biological age is warranted.

Emerging Anti-Ageing Drugs

Geroscience is a scientific field that studies the fundamental biology of ageing. The ultimate goal of geroscience is to accelerate research into the basic mechanisms driving ageing, which could lead to the development of anti-ageing drugs. The use of anti-ageing drugs would mark a paradigm shift: from treating each age-related medical condition separately, to treating these conditions together, by targeting ageing itself.

If successfully implemented, geroscience-informed interventions could reduce strain on the NHS, boost workforce productivity, attract investment and reduce health inequalities.

Limitations to the discovery and development of new anti-ageing drugs were recently explored in a report by the Royal Society, which highlighted four key areas where more effort is required to ensure the benefits of ageing research can be realised across the UK.

Geroscience research must be:

(1) Bolstered by a collaborative and interdisciplinary research and innovation ecosystem focussed on the ageing process as a whole, that can spur change and catalyse progress.

(2) Fuelled by ambitious and long-term funding to attract talent and foster innovation.

(3) Enabled by an agile and innovative regulatory framework for drug design and clinical trials, streamlining the path from laboratory discovery to patient treatment.

(4) Accompanied by shifts in policy to fully translate the UK’s scientific strengths into people’s lives.

Scotland has an international reputation for the quality of its Life Science research, with particular strengths in human health. Life Sciences is one of the country’s most productive and high growth sectors, showing 10% growth year-on-year during the past decade1. How Life Science expertise can be leveraged in Scotland to support geroscience research and development is yet to be explored.

This section will discuss drugs currently in human clinical trials that have the potential to slow biological ageing and the onset of age-associated diseases.

Metformin

Metformin, a drug prescribed in tablet-form to patients with type II diabetes for 60 years, is now being investigated for its efficacy in slowing the rate of ageing. Metformin has been considered the front-line therapy for type II diabetes since the 1990s due to its safety and efficacy1. One of the most influential findings supporting metformin’s anti-ageing potential came from a 2014 study by Bannister et al. 2. In this study, individuals with type II diabetes given Metformin monotherapy were show to have lower overall mortality, particularly in those aged 71-74 years old, than the general population. Further observational studies suggested that patients with type II diabetes treated with Metformin had decreased risk of heart disease and cancer incidence; and improved brain function3.

The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (clinical trial) demonstrated reduced risk of heart disease in patients with type II diabetes allocated to Metformin compared with conventional treatment4. Investigations into whether Metformin could benefit non-diabetic individuals are now underway. A recent study on Metformin supplementation to aged non-human primates revealed a significant slowing of ageing indicators, particularly improving brain ageing5. In the US, the Targeting Aging with Metformin (TAME, n=3000 people) trial, is now in its preparatory stage to explore the role of Metformin on healthspan and lifespan in individuals aged between 65-79. Unlike traditional clinical trials focussed on single diseases, TAME aims to delay the onset of various ageing-related diseases, such as stroke, cancer and dementia, as well as decline in mobility and cognitive function. If successful, the trial could provide proof of concept that ageing can be treated as a stand-alone medical condition.

GLP-1 medicines

Initially developed for type II diabetes then obesity, GLP-1 medicines are emerging as promising agents in broadly preventing age-related diseases, including coronary heart disease, chronic kidney disease, liver disease, and neurodegenerative disease1. They work by mimicking the hormone GLP-1, which increases insulin secretion and improves glucose metabolism. GLP-1 medicines slow gastric emptying, which makes people feel fuller and reduces their appetite, leading to weight loss. In many clinical trials, people lost 15-20% of their body weight, a clinically meaningful amount2.

Three medicines are approved for use in NHS Scotland for managing weight in the treatment of obesity:

Liraglutide (Saxenda®)

Semaglutide (Wegovy®)

Tirzepatide (Mounjaro®)

Beyond diabetes and obesity management, the anti-inflammatory effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists may mitigate chronic inflammation, a key factor in age-related diseases3. Recent results from the SELECT trial have shown statistically significant reductions in cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality. Further analysis of SELECT trial data suggested that GLP-1 medicines may also benefit kidney-related outcomes, including reductions in albuminuria, slower declines in estimated glomerular filtration rate, and a decreased risk of end-stage kidney disease in patients with and without diabetes4. In a recent phase 2b clinical trial on 169 participants with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease, Liraglutide was shown to slow aspects of cognitive decline potentially by reducing inflammation, lowering insulin resistance and the toxic effects of Alzheimer’s biomarkers or improving how the brain’s nerve cells communicate5.

As many age-associated diseases are linked to metabolic health, GLP-1 receptor agonists could broadly extend healthy life expectancy; however, more studies are needed to confirm these initial observations and balance the side effects of these drugs.

GLP-1 receptor agonists, while beneficial for several markers of metabolic health, present several risks that require careful consideration. Evidence suggests the type of weight being lost with GLP-1 could be different to calorie restriction alone, with a disproportionate loss of muscle (measured by decreases in fat-free mass)6. The importance of maintaining skeletal muscle mass during ageing is being increasingly recognised, and the long-term consequence of GLP-1 medicines on muscle health has not yet been investigated. Common side effects of GLP-1 medicines include gastrointestinal issues such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhoea. Rarer but more serious concerns involve the potential risk of pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas) and gallbladder-related disorders. There is also a small but noteworthy risk of thyroid tumours, which needs monitoring. In addition to the potential for side-effects while taking GLP-1 medicines, rapid weight regain after treatment discontinuation and associated reversal of cardiometabolic improvements, as compared to behavioural weight loss programs, highlight the need for long-term, individualised strategies to sustain clinical benefits78.

Shortages of GLP-1 medicines have previously impacted patient care, leading to concerns that these medications should be reserved for patients with type II diabetes9. To ensure fair distribution and treatment safety, increased production, stable supply chains, and strategies to mitigate shortages are needed.

The Scottish Government has recently published data on the use of weight loss medication (e.g., Ozempic, Wegovy, Mounjaro). It found that 6% of respondents reported using weight loss medication for any reason in the past 12 months, and that the majority of respondents had obtained it privately (71%).

The potential for misuse, especially in non-diabetic populations seeking weight loss for aesthetic or cosmetic purposes, poses a significant concern. The UK medicines regulator has not assessed the safety and effectiveness of these medicines in non-overweight/obese/diabetic individuals10. It is crucial for healthcare providers to weigh these risks against the benefits and to monitor patients closely during treatment.

Current barriers to the widespread adoption of GLP-1 medicines include the cost and availability of medicines across the UK.

Senolytics

Senolytics are a class of drugs that selectively eliminate senescent cellsi. Around 80 senolytics are known, but only two have been tested in humans: a combination of dasatinib and quercetin.

Although senescent cells have a variety of beneficial roles in the body (such as wound healing), during ageing these cells accumulate to excess and contribute to disease through the secretion of molecules including pro-inflammatory cytokines1. Pro-inflammatory cytokines can trigger normal cells all over the body to become senescent1. Senescence in immune cells weakens the immune system and reduces its ability to clear senescent cells, creating a vicious cycle of inflammation and senescence1.

Persistent elevated levels of inflammation can lead to organ damage and development of age-related disease. Conversely, centenarians have been found to have strong anti-inflammatory abilities, suggesting that long-lived people are able to avoid age-associated inflammation45.

This phenomenon of low-grade, chronic damage resulting from increased inflammation levels within the body is now considered a hallmark of ageing and is called ‘inflammageing’6.

Removal of senescent cells using senolytics is being explored as a treatment for age-associated disease or situations where people have increased numbers of senescent cells. Overaccumulation of senescent cells can also occur in situations of high stress, such as cancer treatment with chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Childhood cancer survivors were shown to age decades faster with increased frailty measured by walking speed7. Senolytics are now being explored in childhood cancer survivors to see if they can reduce frailty by clearing senescent cells7.

In the context of ageing, senolytics drugs have shown promising results in the clearance of senescent cells and associated disease risk in animal models9. In humans, clearance of senescent cells has also been reported10.

However, more research into the efficacy and safety of senotherapeutics is needed from clinical trials11. It is important to check the specificity of senolytics in killing senescent cells to ensure there are no systemic effects and side effects. Ongoing research aims to build on the first generation of senolytics drugs to enhance tissue targeting, reduce off-target toxicity, and improve how the body interacts with the drugs11.