Scottish Budget 2026-27

This briefing considers the Scottish Government's spending and tax plans for 2026-27. More detailed presentation of the budget figures can be found in our budget spreadsheets. Infographics and supporting analysis provided by Andrew Aiton, Kayleigh Finnigan, Fraser Murray and Maike Waldmann.

Executive Summary

The Scottish Budget 2026-27 is the final budget of the 6th session of the Scottish Parliament, and like last year comes in the context of a minority SNP Government.

While the parliamentary arithmetic suggests that the Scottish Government will require support from at least one other party to pass the budget, the Labour party has indicated that they intend to abstain. With only 4 months left until the next Scottish election, it therefore seems likely that Parliament will pass the Budget.

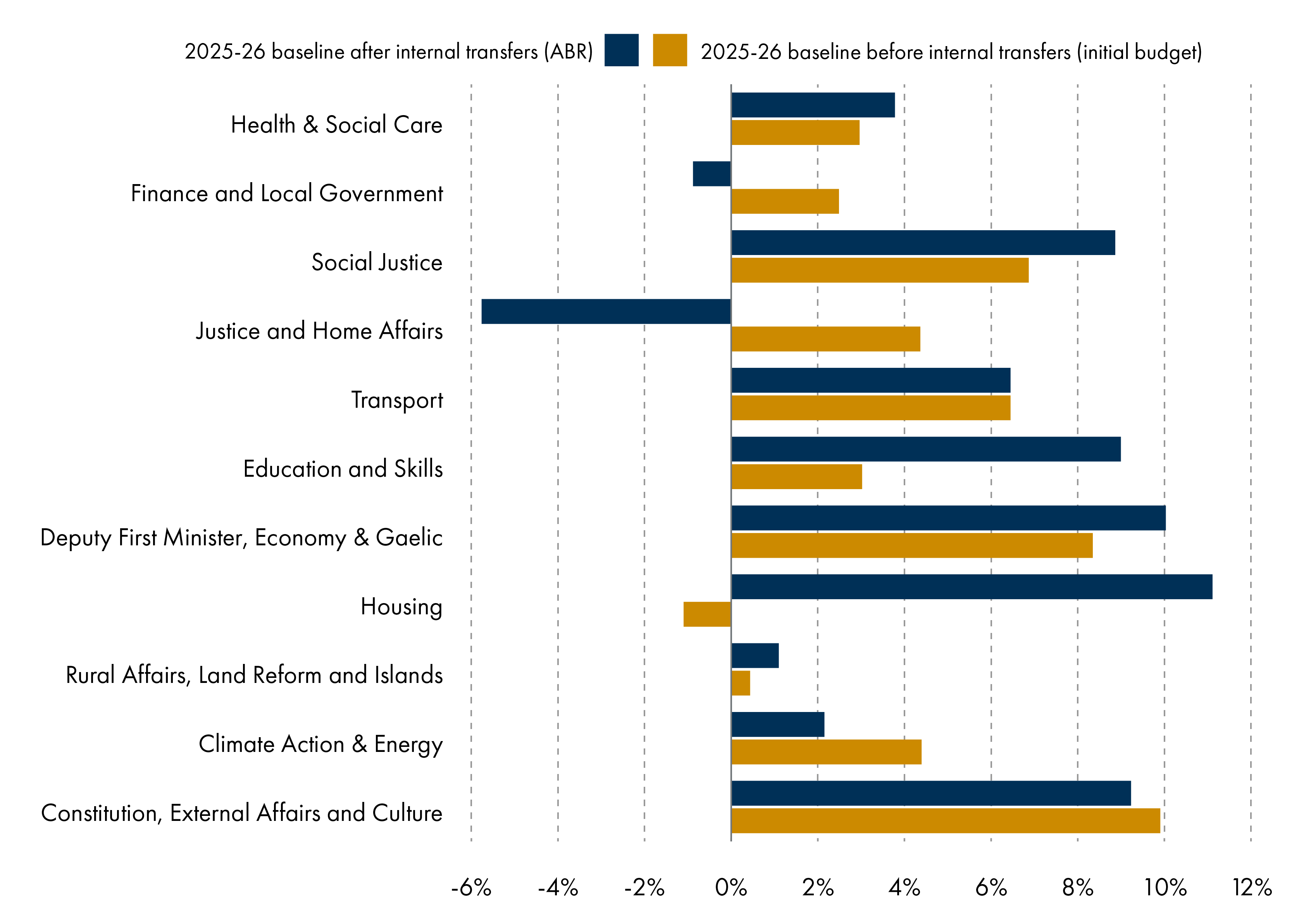

Like last year, the Scottish Government has opted to present the Budget using the 2025-26 Autumn Budget Revision (ABR) as the baseline. While it is helpful to compare spending plans to the most up to date position for the current financial year, the picture is complicated by the routine transfers that occur between some portfolios. The Scottish Government has made some progress in ‘baselining’ these to reduce distortions, but care still needs to be taken to understand the impact that in-year transfers have on figures.

Some minor changes to taxation policy

The Scottish Government announced some relatively minor changes to taxation. The starter and basic bands will be increased by 7.4%, which will reduce the amount of tax paid by the majority of taxpayers. The result of this change is small however, worth a maximum of £31.75 per year. This change, on current forecasts, suggests that 55% of taxpayers will pay less than they would under the rest of the UK (rUK) income tax regime – although the difference for most is also small at a maximum of £40 per year. Higher rate taxpayers will continue to pay more income tax in Scotland than they would in the rUK. The Scottish Government have stuck to their commitment to not increase tax rates.

The Budget also signals some policy measures intended for future financial years. The first is a commitment to introduce Air Departure Tax (ADT) in April 2027 – 10 years after the Scottish Parliament passed the Air Departure Tax (Scotland) Act. This also includes a pledge to introduce a private jet surcharge, but no details of the rates of this tax or how much it will raise are set out.

Similarly, the Budget includes a pledge to introduce two new bands of council tax. These will be payable on properties valued at above £1 million or £2 million, based on an up-to-date valuation. Receipts from this will be retained by local authorities, but like ADT it will not be implemented until 2028.

A further future proposal is to pay a higher rate of Scottish Child Payment for babies under 1, proposed for introduction in 2027-28.

Social security spending is the biggest winner in 2026-27

While total resource funding in the 2026-27 Budget is forecast to grow by 1.1% compared to last year, most of this increase is accounted for by social security spending. Once this is stripped out, resource funding for public services is set to increase by a much smaller 0.2% year-on-year. This largely reflects existing policy and forecast expenditure. [Note, various definitions can be used and these calculations are based on those used by the Scottish Fiscal Commission.]

It was confirmed that, in 2026-27, devolved benefit payments will increase in line with the September 2025 CPI inflation rate of 3.8%. The only significant policy announcement on social security was a decision to increase the Scottish Child Payment to £40 per week (it was £27.15 per week in 2025-26) for children under the age of one. As noted above, this will take effect in 2027-28, so it is not a cost in the 2026-27 Budget. The SFC forecasts that parents of 12,000 children will benefit from this, at a cost of around £7 million per year.

Local government allocations grow ahead of inflation

The local government revenue settlement sees a real terms increase of £419 million (+2.9%) when the Budget is compared to last year’s Budget document (as is usual for the local government budget). A smaller proportion of the settlement is ring-fenced for specific purposes or transferred in-year from other portfolios. This is something that councils will welcome as it increases local flexibility.

However – and there is always a “however” with local government funding – the increase in 2026-27 falls far short of what COSLA called for in December. They campaigned for a revenue settlement of £16 billion in 2026-27, including an additional £750m for social care.

The Budget is accompanied by some long-awaited medium-term plans

The Scottish Government has published a first Scottish spending review since 2022, and a new four-year Investment Delivery Plan, as well as launching a consultation on a new 10-year Infrastructure Investment Plan. These are welcome publications which increase understanding of the Scottish Government’s priorities, and the fiscal context. Although with May’s election looming, the next Scottish Government may have different priorities and adopt different plans.

The detail in the spending review is variable however. While some portfolios are shown down to level 4 (the most granular spending plans), local government plans are provided to level 3, while others only show level 2 such as Education and Transport.

A longer-term profile for third sector funding will also be a welcome development for the sector, which has repeatedly highlighted the challenges that short-term funding agreements present for service delivery. Indicative health board budgets for three years are also provided.

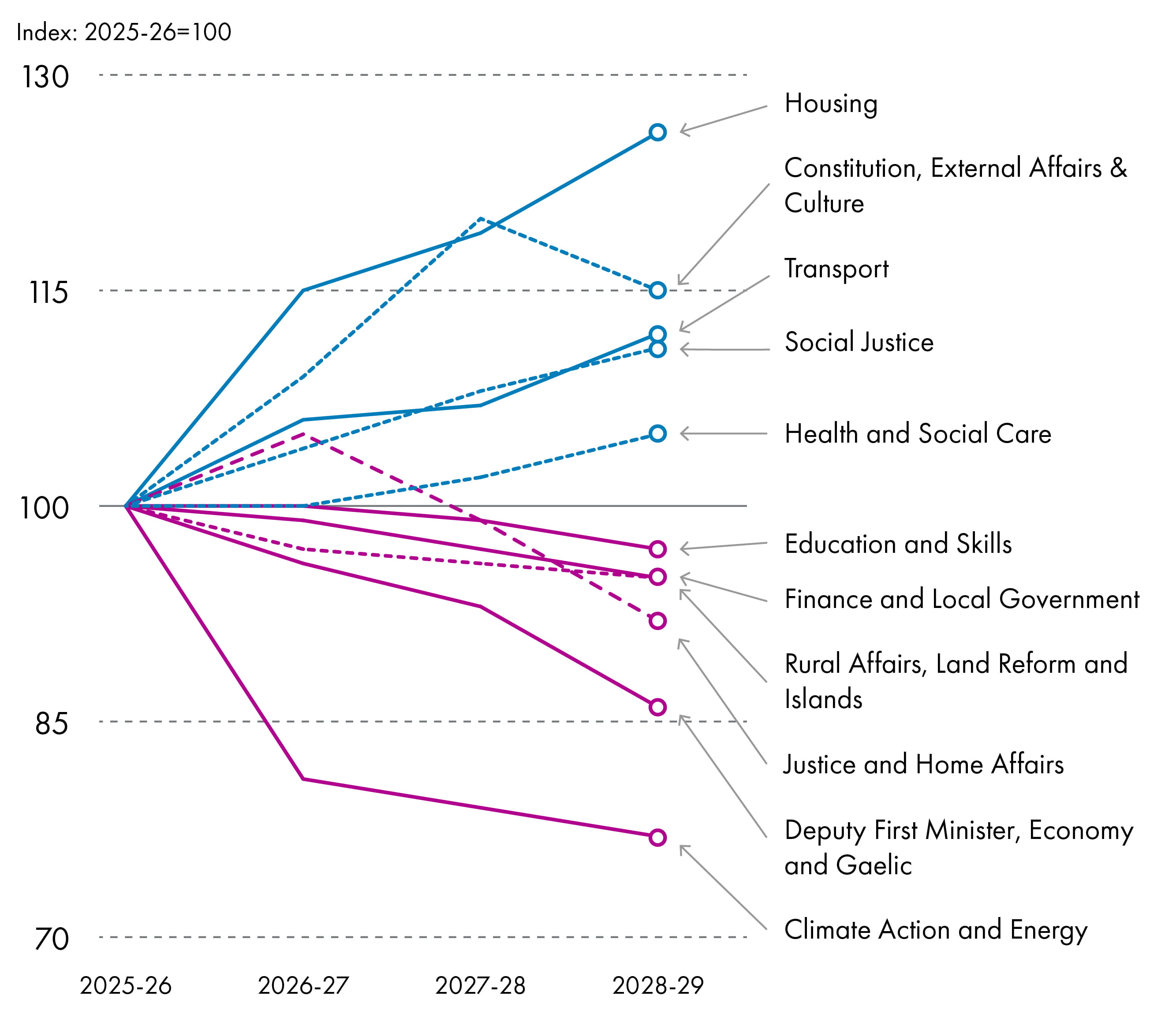

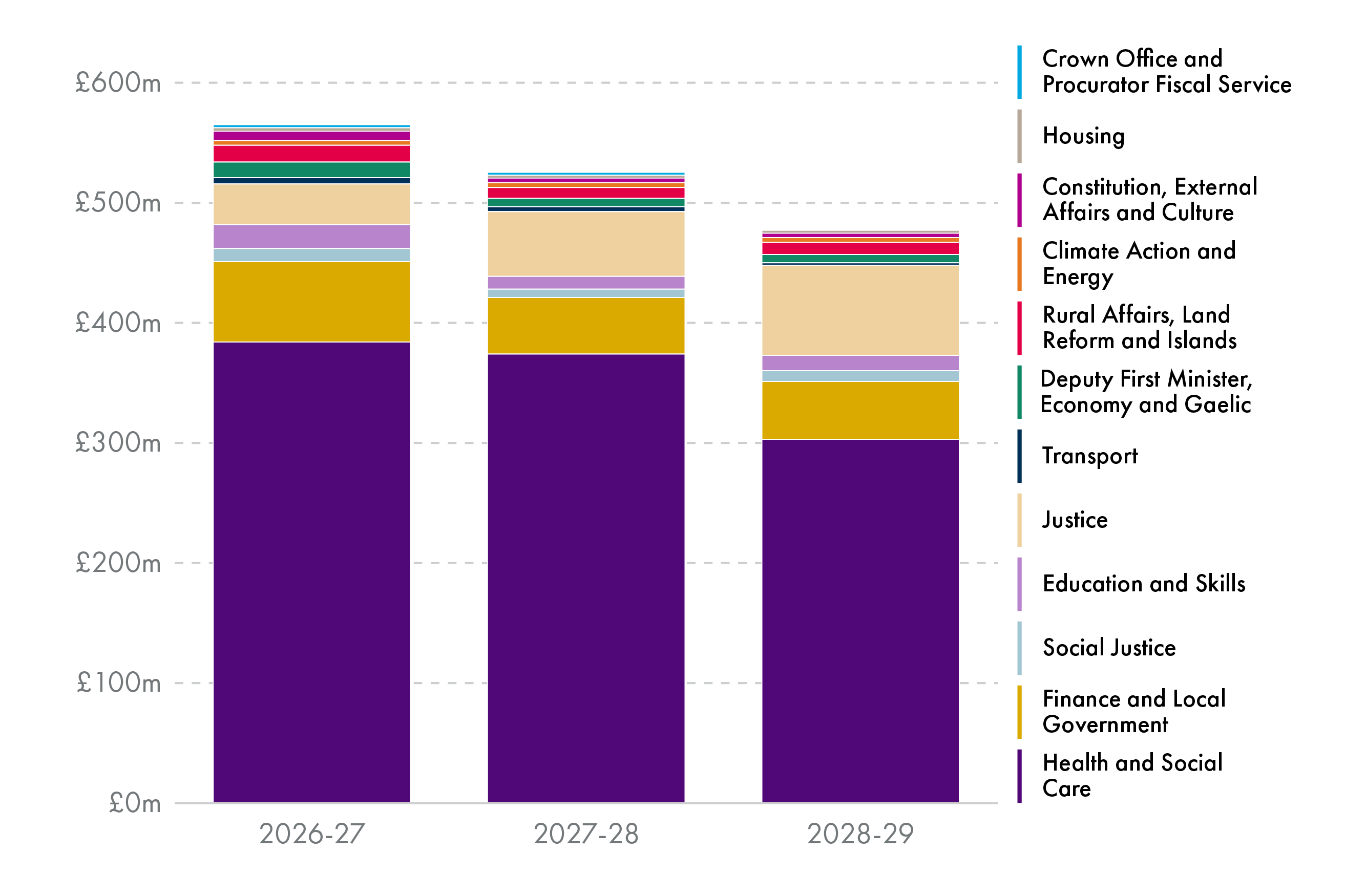

The analysis shows that housing is set to see the strongest growth, increasing by 26% over the spending review period. Constitution, External Affairs and Culture also grows strongly, in the first two years, reflecting a number of important events being hosted in Scotland. Transport, social justice and health and social care also see positive real terms growth throughout the period. Other areas see real terms reductions over the spending review period, with Climate Action and Energy seeing the largest fall of 23% over the three-year period.

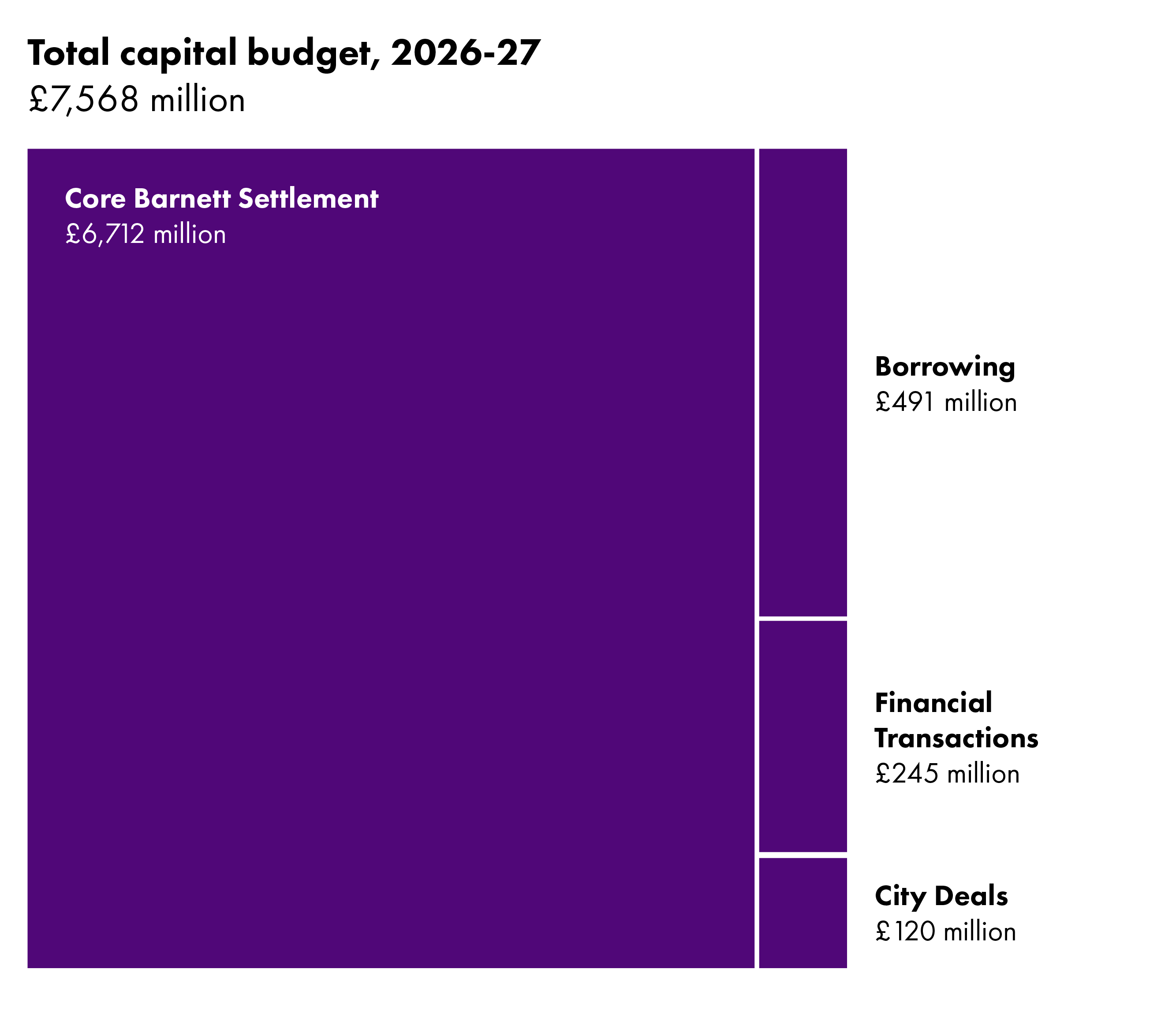

The outlook for capital funding is particularly restricted

Compared to the 2025-26 Autumn Budget Revision (ABR) position, the capital budget is 0.3% smaller in real terms in 2026-27. The two largest portfolios by share of the capital budget both have an increased allocation; the Transport capital budget increases by 8% in real terms, and Housing by 17% in real terms.

The Scottish Government has indicated that it intends to launch a £1.5 billion Bond programme during the next parliament. £2.1 million is allocated in the 2026-27 Budget for preparatory work.

Non-domestic rates (NDR) relief

A key issue in recent budgets has been the extent to which relief for businesses from NDR liabilities match reliefs announced by the UK Government for England. There has been particular interest this year as Scotland, like England and Wales, is currently undergoing a revaluation of rateable values.

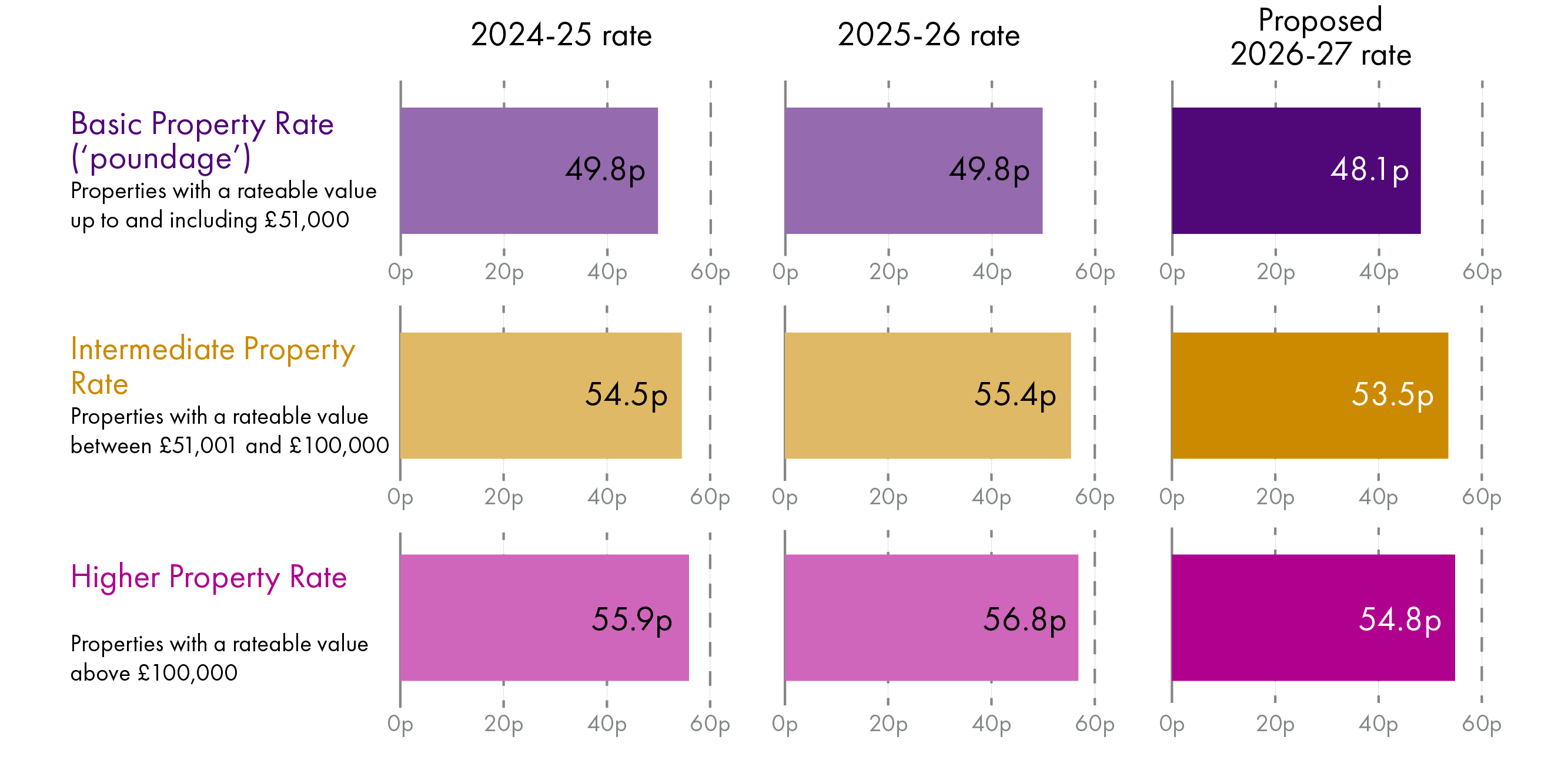

The 2026-27 Budget includes measures aimed at softening some of the impacts of the 2026 revaluation, with the Government reducing the Basic Property Rate (for properties with a rateable value up to and including £51,000) from 49.8p to 48.1p. Similar reductions are proposed for the Intermediate and Higher Property Rates.

The Budget includes a new 15% NDR relief from April 2026 to March 2029 for Retail, Hospitality or Leisure (RHL) premises liable for either the basic or Intermediate Property Rates. This could help up to 37,000 properties (subject to the cap of £110,000 per ratepayer) and will reduce the NDR bills of beneficiaries by around £36 million in 2026-27. The Budget also extends and expands the 100% relief for three more years for RHL properties on islands and some remote areas (capped at £110,000 per business per year).

How these reliefs compare to those announced by the UK Government (for NDR payers in England) at the Autumn Budget Statement will undoubtedly be explored over the coming weeks, as well as how the Scottish Government might respond to any further measures announced for England.

Transparency remains a challenge

There have been some positive developments, such as the baselining of some of the regular internal transfers that can make comparisons over time difficult. However, some of the headline policy decisions highlighted by the Cabinet Secretary are difficult to match to the published figures.

The £70 million uplift in funding for colleges has been welcomed by the sector, given the challenging financial settlements faced in recent years. However, it is difficult to identify how this figure has been arrived at from the published documents – you have to compare college funding on a year-to-year basis (not to the ABR like the rest of the budget), and you have to exclude the significant £30.3 million investment in the Dunfermline campus in 2025-26.

Similarly, the references to “frontline spending” in health do not match any definitions used in the published budget figures, creating challenges for following the statements relating to this budget. Health is still the largest area of spending in the Scottish budget and some of the additional funding this year will be required to meet pay deals agreed for the NHS.

Context for Scottish Budget 2026-27

The Scottish Budget 2026-271 was published on 13 January 2026 and presents the Scottish Government’s proposed spending and tax plans for the next financial year. The publication signals the start of a period of Parliamentary scrutiny culminating in MSPs voting on these proposals in February 2026. Like last year, the Scottish Government now operates as a minority, so in theory will require support from at least one other party to get its Budget passed. However, the Labour party has indicated that they intend to abstain, which if they do would mean that SNP votes alone would be sufficient to pass the Budget. While nothing will be certain until the vote, this suggests that there may be less pressure on the Cabinet Secretary to agree deals to secure support from other parties than was the case last year.

Due to a later than expected UK Budget2, which took place on 26 November 2026, this Scottish budget has also been published later than normal. This necessitates a shortened period for Parliamentary scrutiny, with Stage 3 scheduled for 25 February.

While there is an election only four months away and therefore a chance of a change of government, this is also the first Scottish budget since the UK spending review3 was published in June 2025. With greater certainty as to their funding position for the medium term, the Scottish Government has also published a Scottish Spending Review and an Infrastructure Delivery Plan alongside the budget, setting out medium term spending plans and priorities.

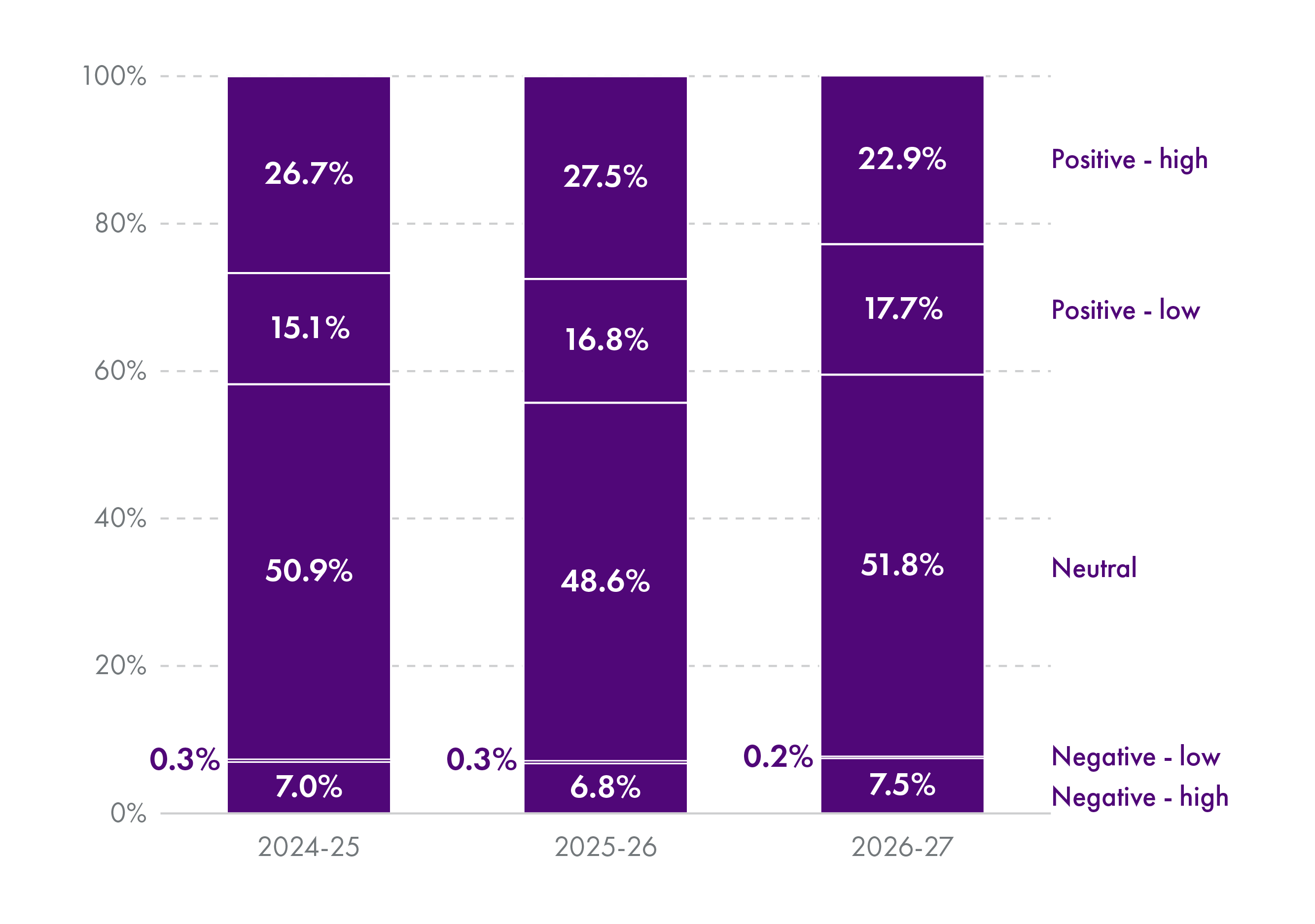

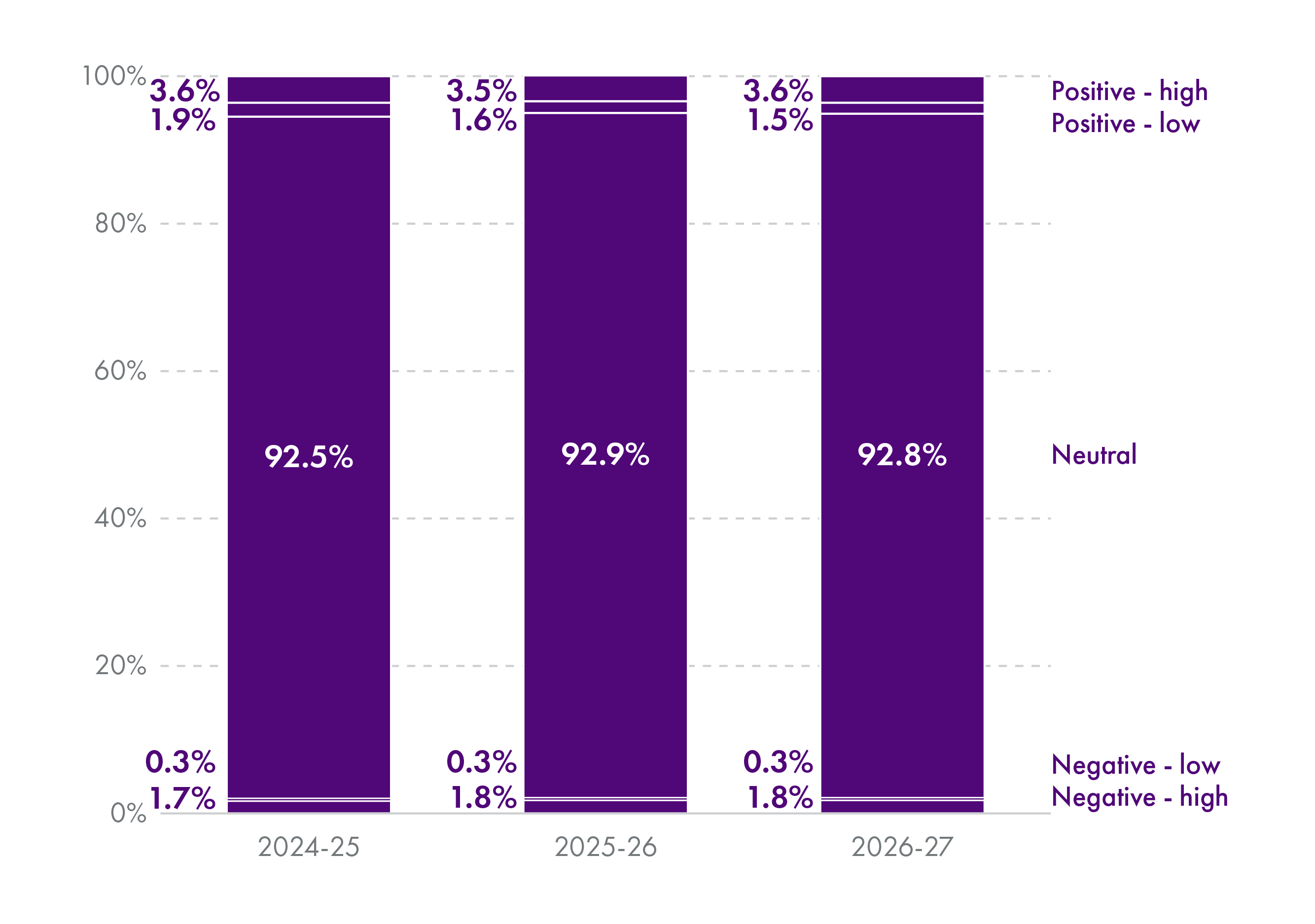

The Budget incorporates devolved tax forecasts undertaken by the Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC). As well as producing point estimates for each of the devolved taxes for the next five years, the SFC is also mandated to produce forecasts for Scottish economic growth and spending forecasts for devolved social security powers. The SFC forecasts4 are considered in greater detail later in this briefing.

Baseline issue

As with last year, the Scottish Government has opted to present the Budget using the 2025-26 Autumn Budget Revision (ABR) as a baseline. This matters as there can be considerable changes to portfolio allocations throughout a financial year, as explained in more detail in a recent SPICe blog.

While some of these changes reflect evolving priorities, or additional resources becoming available, some of the significant transfers occur routinely each year. For example, funding for social care is presented under Health and Social Care in the original budget, and then routinely transferred during the year to the Local Government portfolio, as local authorities are responsible for the delivery of social care.

What this means is that comparing portfolio allocations from the Budget to allocations from the 2025-26 ABR might be misleading, depending on the impact of these transfers. This is an issue that the Finance and Public Administration Committee has raised with the Scottish Government. Table 4.15 in the Budget document shows the difference this can make; taking the ‘headline’ Local Government budget figure would show a decrease of 1.9% in cash terms, as the 2025-26 ABR figure includes transfers from other portfolios such as Education and Health, but the 2026-27 Budget does not. Removing these transfers means the cash terms increase is +3.0%. For local government, this is explained in the main body of the document, but for other portfolio areas, it is harder to unpick the detail.

Table A.09 of the main document shows the effect of routine in-year transfers and the impact of the choice of baseline is illustrated in the chart below, which shows that for some portfolio areas it makes a significant difference.

The Scottish Government has also published an ‘additional budget disclosures’ document which sets out the impact of in-year budget changes over the last three years, but it is not easy to interpret or understand all the reasons for the changes.

The Scottish Government has made some progress in this area by baselining some routine transfers, but the remaining transfers can still distort comparisons. The SFC notes that:

While the Scottish Government has continued to improve the presentation of spending in the Budget including publishing the data showing which transfers have not been baselined, there are still further improvements to be made. We continue to recommend that all routine Budget transfers should be contained from the outset in the spending portfolio to which they will ultimately move.

Budget overview

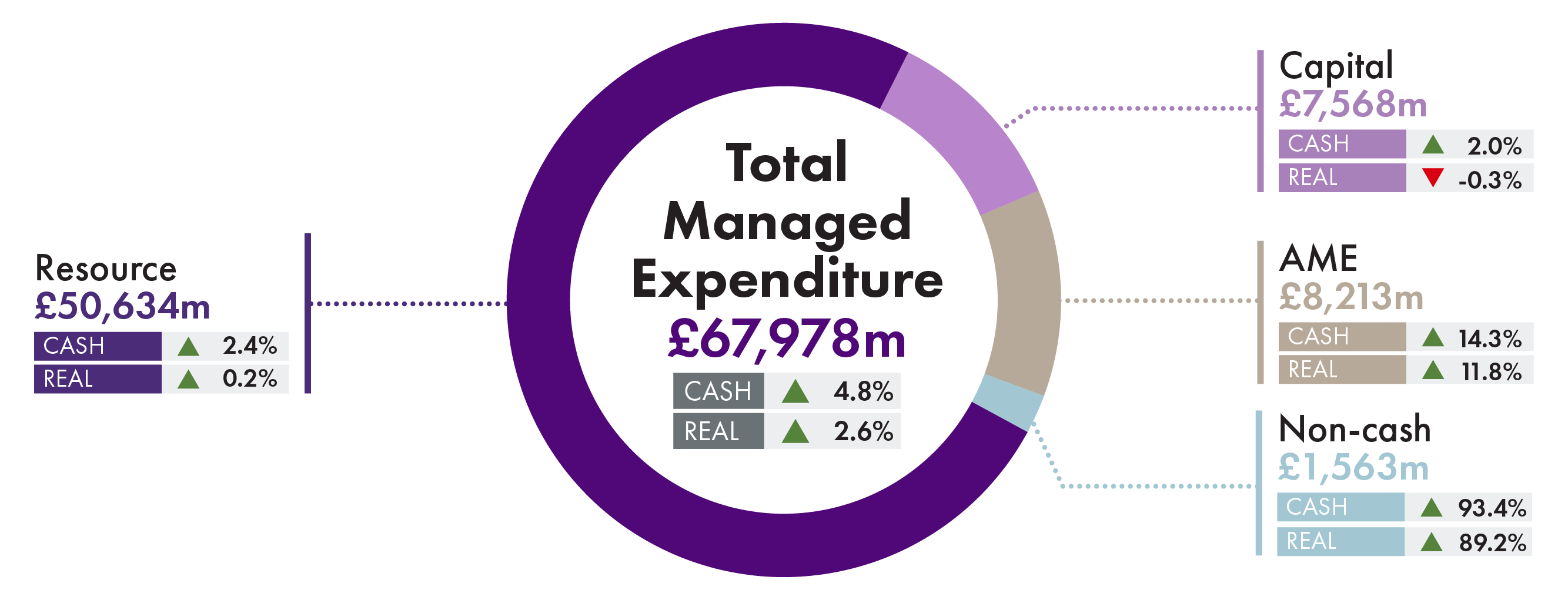

The total budget for 2026-27 is £67,978 million, made up as shown in Figure 2.

Total Managed Expenditure (TME) comprises Resource, Capital, non-cash Resource and Annually Managed Expenditure (AME). Resource (which covers day-to-day expenditure) and capital (covering spending on buildings and physical assets) are the elements of the budget over which the Scottish Government has discretion.

As shown in Figure 2, the budget document shows (based on the ABR baseline for 2025-26) that resource is due to increase by 2.4% in cash terms in 2026-27 and capital is set to increase by 2.0% . In real terms, resource is increasing by 0.2% and capital is reducing by 0.3%.

AME is expenditure which is difficult to predict precisely, but where there is a commitment to spend or pay a charge, for example, pensions for public sector employees. Pensions in AME are fully funded by HM Treasury, so do not impact on the Scottish Government's spending power. AME increases significantly next year due to the costs of managing the Teachers and NHS Pension schemes and changes related to the treatment of Police pensions. This is a UK funded AME line and does not arise from any Scottish Government decision or impact on the discretionary spending power of the Scottish budget. Non-Domestic Rates income is also classed as an AME item in the budget and forms part of local government spending.

The non-cash increase is largely explained by the “Resource Accounting and Budgeting” (RAB) charge related to the provision of student loans. The RAB charge reflects current economists’ estimations on future loan write-offs and interest subsidies. As with AME, changes to this budget line are technical non-cash adjustments and do not affect discretionary spending.

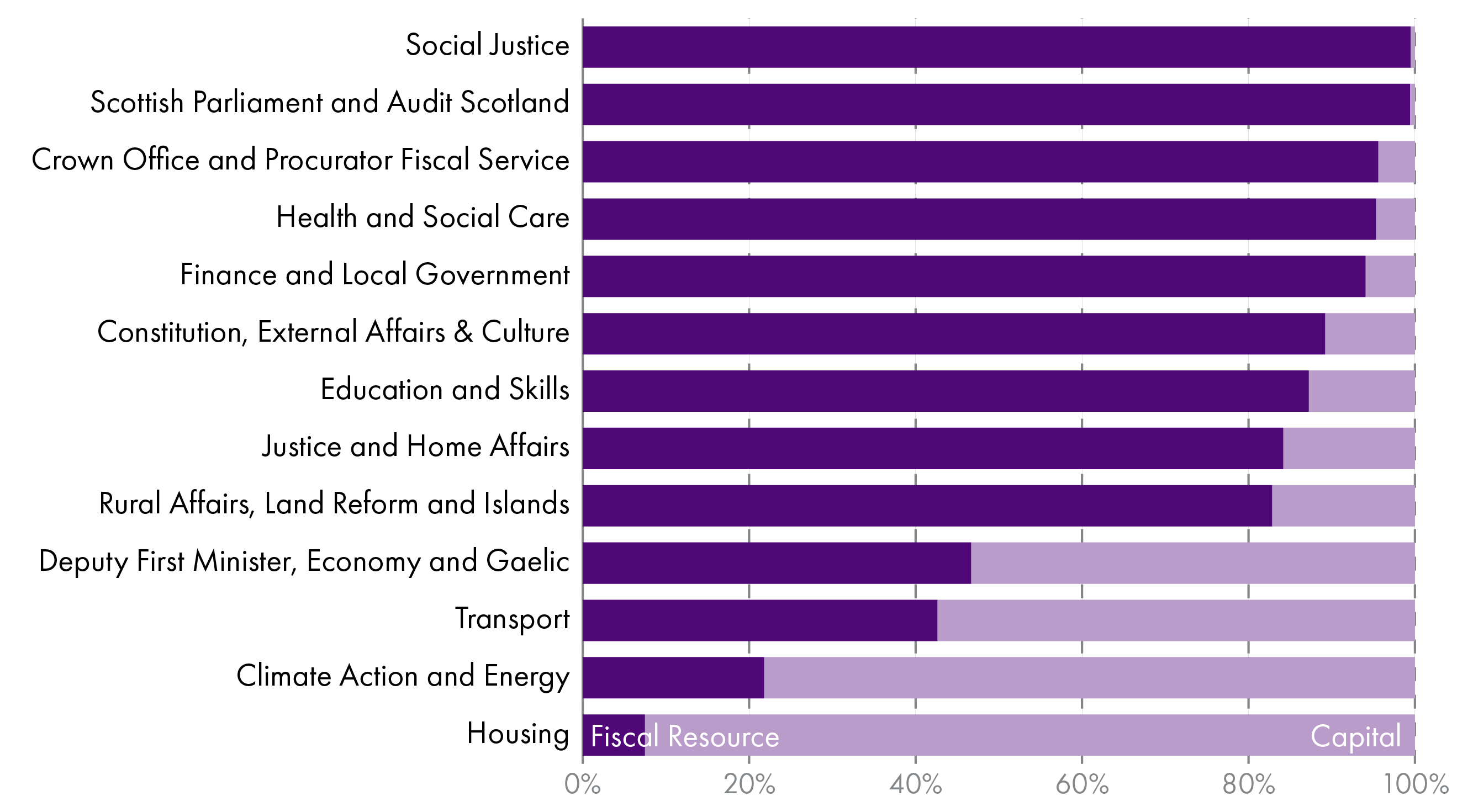

Figure 3 below shows the split between resource and capital by portfolio. This shows that most portfolios are heavily weighted towards funding day-to-day spending commitments (the resource budget).

The Housing, Climate Action and Energy and Transport portfolios have the highest proportion of their budget comprising capital spending. This will include projects to progress towards affordable housing targets, net zero, rail and roads investment and capital investment by Scottish Water. The Deputy First Minister, Economy and Gaelic portfolio also includes significant capital spending on areas like digital connectivity, cities and investment by the Scottish National Investment Bank (SNIB).

Scottish Spending Review

Alongside the 2026-27 Budget, the Scottish Government published its first spending review since the 2022 resource spending review.

With a Scottish election scheduled for May, it will be for the next government to make spending decisions throughout this spending review period. If a new government has different priorities then it is likely to make changes, however the financial realities mean that any different priorities would have to be delivered in the same challenging fiscal context. Commenting on the plans for a Scottish Spending Review, the SFC noted that:

The Scottish Spending Review … will determine the trajectory of public spending over the next Parliamentary term and it must provide a meaningful basis for informed debate on the public finances during and after the election.

Closing the fiscal gap will require all parties in this Parliament and the next to work together to address the fiscal challenges and any debate around new spending plans, changes to social security policy or tax changes needs to consider the broader public finances.

The document provides some detail on portfolio resource allocations over the next three years, and capital over the next four years, mirroring the period covered by the UK Government’s spending review published in June 2025. The level of detail provided varies by portfolio – some are down to level 4 (including aspects of health and social care), local government plans are provided to level 3, while others only show level 2 such as Education and Transport.

So, while this provides some welcome detail, it is patchy – for example, for health, the indicative budgets for individual health boards will be welcome, but there is a notable gap in terms of the detail of other areas of the health budget that do not get directed to health boards, such as GP funding.

A longer-term profile for third sector funding will also be a welcome development for the sector, which has repeatedly highlighted the challenges that short-term funding agreements present for service delivery. Setting out a three-year budget for third sector infrastructure funding, the Scottish Government states that “this Spending Review supports our commitment to Fairer Funding for the Third Sector.”

Figure 4 below sets out the real terms growth rates for each portfolio, as set out in the spending review. The base year uses the 2025-26 Autumn Budget Revision data included in the budget document, but to make the data comparable to the spending review profile there are two changes. We have used Table A.09 from the Budget document to remove the internal transfers which would otherwise increase the ABR baseline, and we have also removed all AME and non-cash allocations from the 2025-26 baseline, apart from non-domestic rates, to match the presentation in the spending review as closely as possible.

The analysis shows that housing is set to see the strongest growth, increasing by 26% over the spending review period. Constitution, External Affairs and Culture also grows strongly, in the first two years, reflecting a number of important events being hosted in Scotland. Transport, social justice and health and social care also see positive real terms growth throughout the period. Other areas see real terms reductions over the period, with Climate Action and Energy seeing the largest fall of 23% over the period.

One area that the spending review provides little detail on is the process. In the build up to the review, there was some discussion about whether this would be a ‘zero based’ review or not, as the recent UK Spending Review was. A ‘zero based review’ involves portfolios having to justify all spending, rather than taking the previous year’s spending plans as a starting point. The intention is that such a robust approach of challenging all spending will identify efficiencies, and ensure resources are being focused on the Government’s strategic priorities.

In evidence to the Finance and Public Administration Committee in September 2025, the Fraser of Allander Institute suggested that:

The issue is the amount of time that the Scottish Government will have for conducting that review and whether it will be enough to conduct a full zero-based review. My view, from looking at how long the Government will have to actually conduct any review, is that it is not enough.

The lack of any detail on the methodology underpinning the spending review will do little to ease these concerns.

Turning to what is in the spending review, in the foreword the Cabinet Secretary states that:

We are clear about the priorities we will deliver: eradicating child poverty; growing the economy; tackling the climate emergency; and ensuring high quality, sustainable public services. This Spending Review aligns multi-year portfolio spending plans and investments to these outcomes, supporting our public bodies and other delivery partners.

We will look at what the proposed allocations in the spending review tell us about these four priorities.

Eradicating child poverty

The Scottish Government highlights eradicating child poverty as its top priority, and highlights the progress made so far in reducing rates of relative poverty.

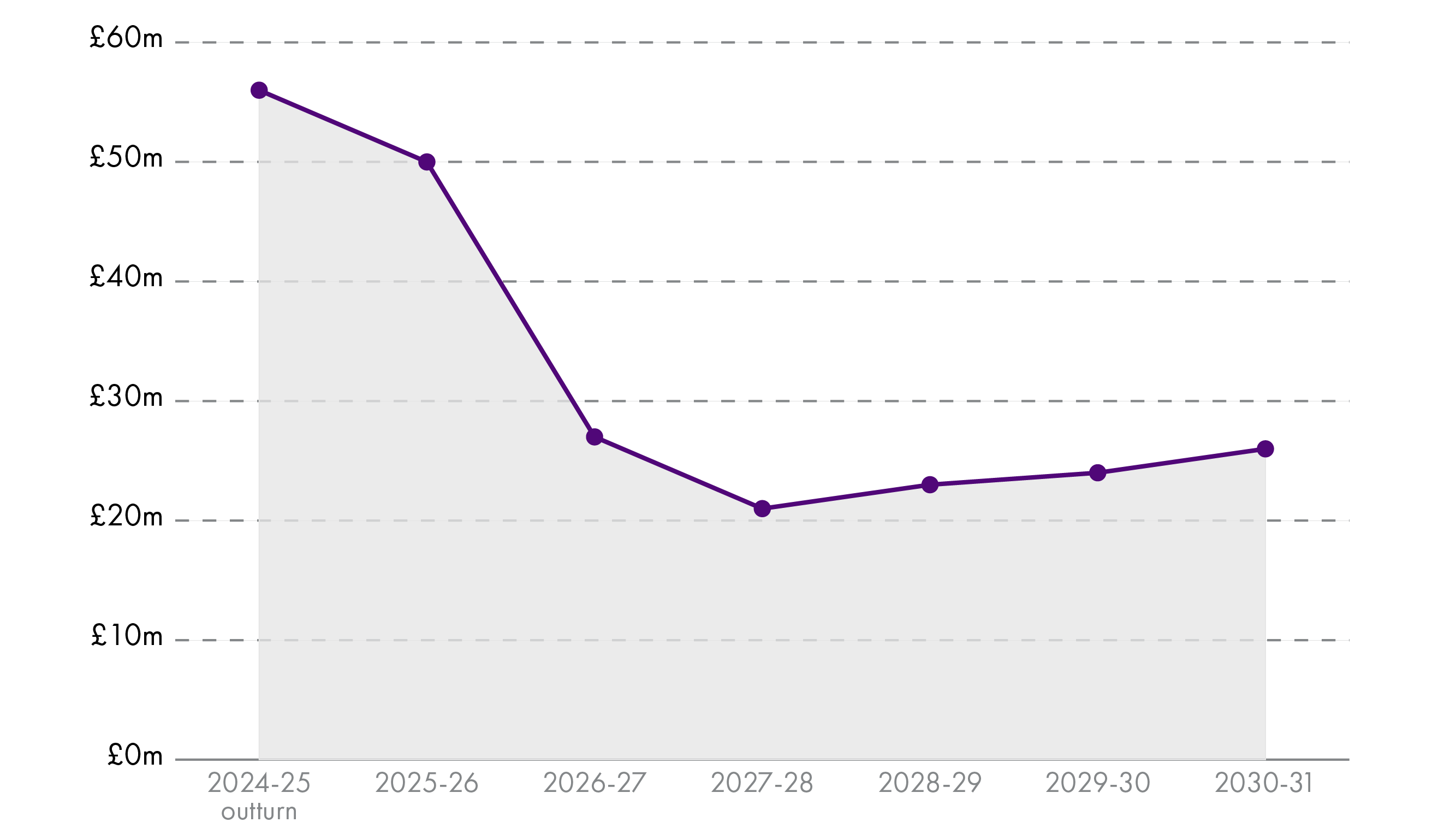

The 2026-27 Budget identified increased spending on measures targeted at ‘tackling child poverty’, growing from just under £60 million in 2025-26 to £163 million in 2026-27 to support the upcoming third plan in 2026. The spending review broadly maintains this increased level of spending.

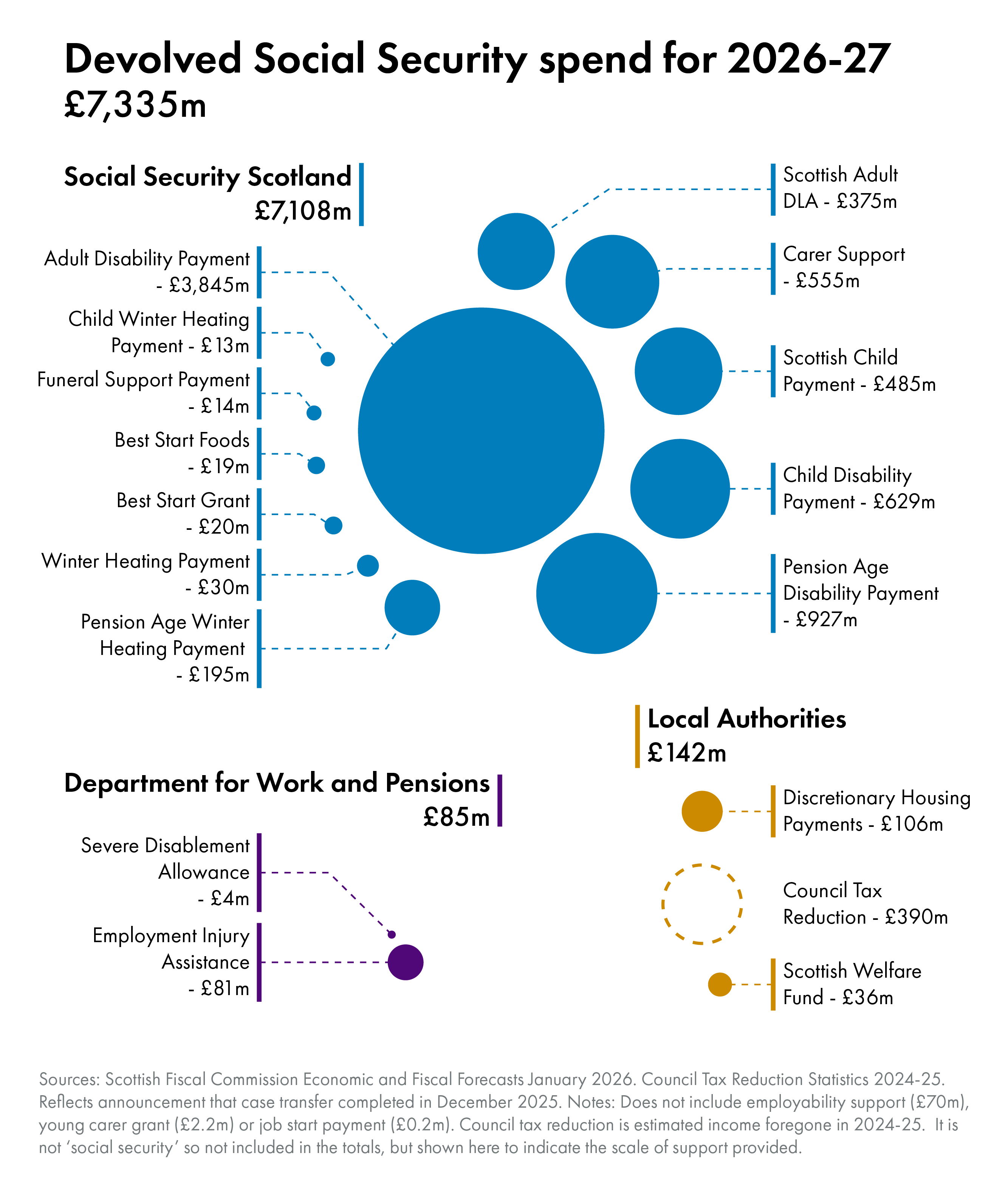

Growing spending on social security has been a feature of recent budgets, and this is set to continue over the spending review period, rising from £6.8 billion in the 2025-26 Autumn Budget Revision to £8.1 billion by 2028-29. The spending review provides a breakdown of this planned spending to level 3, which lists spending on individual benefits. The largest contributors to the increase are expected to be the adult disability payment (increasing from £3.4 billion in 2025-26 to £4.6 billion in 2028-29), and pension age disability payment (increasing from £853 million to £1,009 million in 2028-29). Benefits specifically targeted at children (Child Disability Payment, Child Winter Heating Payment and Scottish Child Payment) are also set to see increased levels of expenditure.

Another clear ‘winner’ of the proposed spending review allocations is the housing budget. The affordable housing programme aims to help reduce child poverty and contributes to significant growth in the Housing and Building Standards level 2 budget, which reaches £924 million by 2028-29. Unfortunately, the housing portfolio is one which is only shown to level 2 so we have limited granularity on the funding allocations here.

Growing the economy

While growing the economy is highlighted as a priority by the Scottish Government, the allocations to key bodies tasked with economic development do not suggest this is a particular priority.

The enterprise agencies face a particularly tight settlement, with real terms cuts in each year. The Scottish Government pledge that they will meet the promise of capitalising the Scottish National Investment Bank with £2 billion in capital funding over its first ten years, but the spending review sets out a flat cash settlement in each year.

Funding for city and regional growth deals also reduces over the period. The 12 deals were agreed at different times for 10- or 15-year periods, and so fluctuations in the spending profile are expected. Some of the earlier deals are also approaching their end, which might contribute to lower spending in the later years of the spending review.

In their report on Scotland’s City and Regional Growth Deals, the Economy and Fair Work Committee highlighted the lack of transparency on the future profile of spending, stating:

the Committee recommends that the Scottish Government clearly sets out its expenditure on growth deals in the annual budget to allow for proper scrutiny. The Committee also asks the Scottish Government to publish a longer-term forecast of its anticipated spend profile on growth deals. Further, it would be helpful to show disaggregated Scottish Government and UK Government contributions to growth deals in the level 4 budget spreadsheet, setting out the contribution to each deal.

The Scottish Government’s response noted that it was ‘exploring’ options for providing annual updates on funding for city and regional growth deals.

The Scottish Government states that employability funding will support 22,000 into work. Growing the workforce and therefore the tax base is one key way that the Scottish Government can improve the performance of devolved taxes and therefore ease the pressure on public funding. However, the employability budget is flat in cash terms.

One area of growth within the Deputy First Minister, Economy and Gaelic Portfolio is for tourism, which nearly doubles in cash terms. Funding for major events is a significant factor – in 2027 Scotland will host the Tour de France Grand Depart, and in 2028 Scotland, along with England, Wales and the Republic of Ireland, will host men’s football European Championships.

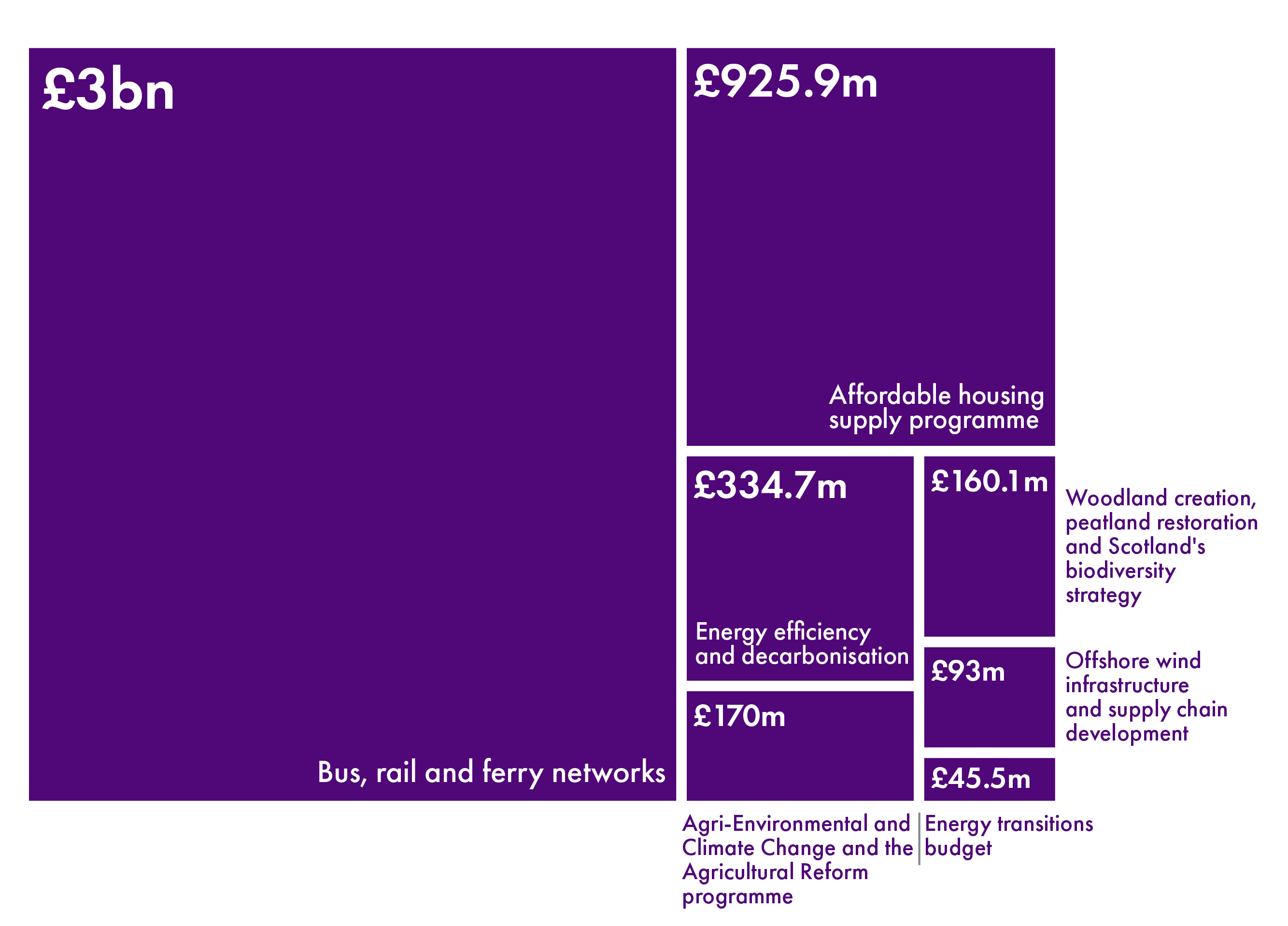

Tackling the climate emergency

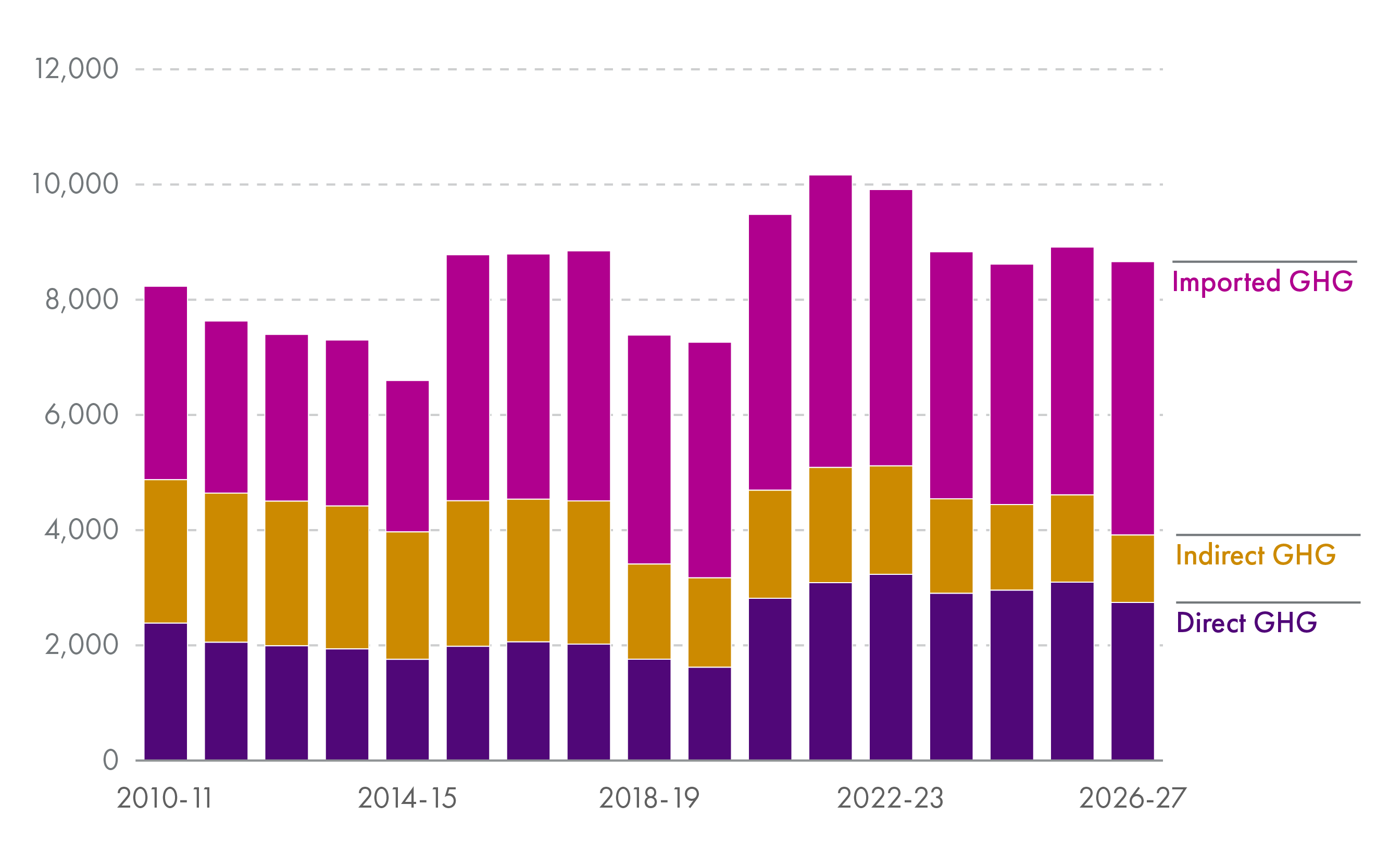

The spending review covers much of the first Carbon Budget period. According to the draft Climate Change Plan, in this period Scotland’s emissions will need to be around 57% lower than 1990 levels on average, compared with the current reduction of around 51% compared to 1990. Within this, transport, residential and public buildings, and business and industrial processes all need to make significant progress in reducing emissions.

The Cabinet Secretary highlighted that over £5 billion in funding in the 2026-27 Scottish Budget would have a positive impact on the Scottish Government’s climate goals. A significant part of this spending relates to the provision of public transport services. We look at this in more detail in the climate change section of the briefing.

The Climate Action and Energy Portfolio is described in the spending review as ‘play[ing] a critical role’ in responding to the climate emergency. However, over the spending review period the allocation to this portfolio is largely flat in cash terms.

Within this, the budget for offshore wind falls from £137 million in the Autumn Budget Revision to the 2025-26 Budget, to £61.7 million by 2028-29. This budget aims to support the development of the offshore wind supply chain, in the context of the significant developments expected through Scotwind during the spending review period. TheScottish Government aims to grow offshore wind capacity to between 8 and 11 GW by 2030, which will require a significant increase from the 4.3 GW of installed capacity as of Q3 2025.

The energy transitions budget aims to support industrial decarbonisation, supporting the development of carbon capture and storage, and supporting the Just Transition in Grangemouth. The level 2 budget grows to £81.6 million in the final year, however this follows successive declines to just over £40 million per year in 2026-27 and 2027-28.

Sustainable public services

The Scottish Government notes that, as set out in in the public sector reform strategy, reducing the overall rates of poverty could reduce public spending by £2.9 billion. The spending review commits to piloting an approach to tracking preventative spend across the Scottish Budget in 2026.

The Spending Review also sets out some more detail on how the £1.5 billion public sector efficiencies and reforms are to be achieved. Health and social care reform will do the heavy lifting, with over £1 billion of the total planned savings to come from this sector. There is repeated reference to the intent to “protect” or “free up” investment in frontline services through the reforms.

NHS Boards will have to achieve recurring annual savings equivalent to 3% of their baseline revenue resource limit. The latest Audit Scotland report, covering the 2024-25 financial year, shows that boards achieved recurring savings of 2.2%, so meeting this target will require an improvement.

The Fraser of Allander Institute notes that some of the planned efficiencies will be challenging to deliver, stating that:

The area that looks like it has taken the biggest clobbering though is the justice system. It does not seem credible that such large cuts can be made to this area without impacts on services.

We discuss public sector reform in more detail elsewhere in the briefing.

Scottish Budget funding

Funding for the 2026-27 Scottish Budget is set to be 1.3% higher in real terms than 2025-26, totalling £61.7 billion. This excludes non-discretionary spending, which comprises non-cash items and annually managed expenditure (AME).

Funding is £698 million higher than had been forecast by the Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) in June 2025.

| £ million (nominal terms) | 2025-26 | 2026-27 | 2027-28 | 2028-29 | 2029-30 | 2030-31 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total funding | 59,536 | 61,677 | 62,968 | 64,583 | 66,731 | 68,420 |

| Real terms growth rate | - | 1.3% | 0.1% | 0.7% | 1.5% | 0.6% |

| Resource funding | 52,340 | 54,109 | 55,420 | 57,018 | 59,120 | 60,909 |

| Real terms growth rate | - | 1.1% | 0.4% | 1.0% | 1.8% | 1.1% |

| Resource funding for public services | 45,582 | 46,704 | 47,532 | 48,718 | 50,362 | 51,683 |

| Real terms growth rate | - | 0.2% | -0.2% | 0.6% | 1.5% | 0.7% |

| Capital funding | 7,196 | 7,568 | 7,548 | 7,565 | 7,611 | 7,511 |

| Real terms growth rate | - | 2.9% | -2.2% | -1.6% | -1.2% | -3.2% |

Note: Non-discretionary spending comprises non-cash items and annually managed expenditure (AME). Resource funding for public services is total resource funding minus forecasted spending on social security.

Resource funding overall is set to grow by 1.1% in real terms in 2026-27, with much of this increase taken up by higher social security spending. Once social security is stripped out, resource spending for public services is forecast to grow by 0.2% in real terms compared with 2025-26.

Compared with the SFC’s June 2025 forecasts, the biggest single addition to resource funding is £297 million through the Block Grant, as a result of decisions at the November 2025 UK Budget. However, worsening income tax forecasts reduce funding for the Scottish Budget by £345 million compared with what had been forecast in June 2025.

The capital budget is set for a boost of 2.9% in 2026-27 compared to the 2025-26 Budget position, but the outlook for the following four years appears tight (see Table 1).

The outlook for Scotland’s economy

The SFC provides economic and fiscal forecasts alongside the Scottish Budget. These tell us about the current state of, and future outlook for, Scotland’s economy. These are useful in themselves, but they also directly impact the Scottish Budget. This is because the forecasts underpin the devolved tax revenues and social security spending in the budget.

This section sets out what the SFC is forecasting on GDP, productivity, inflation, the labour market and earnings. More detail can be found in the SFC’s January 2026 Economic and Fiscal Forecasts.

GDP

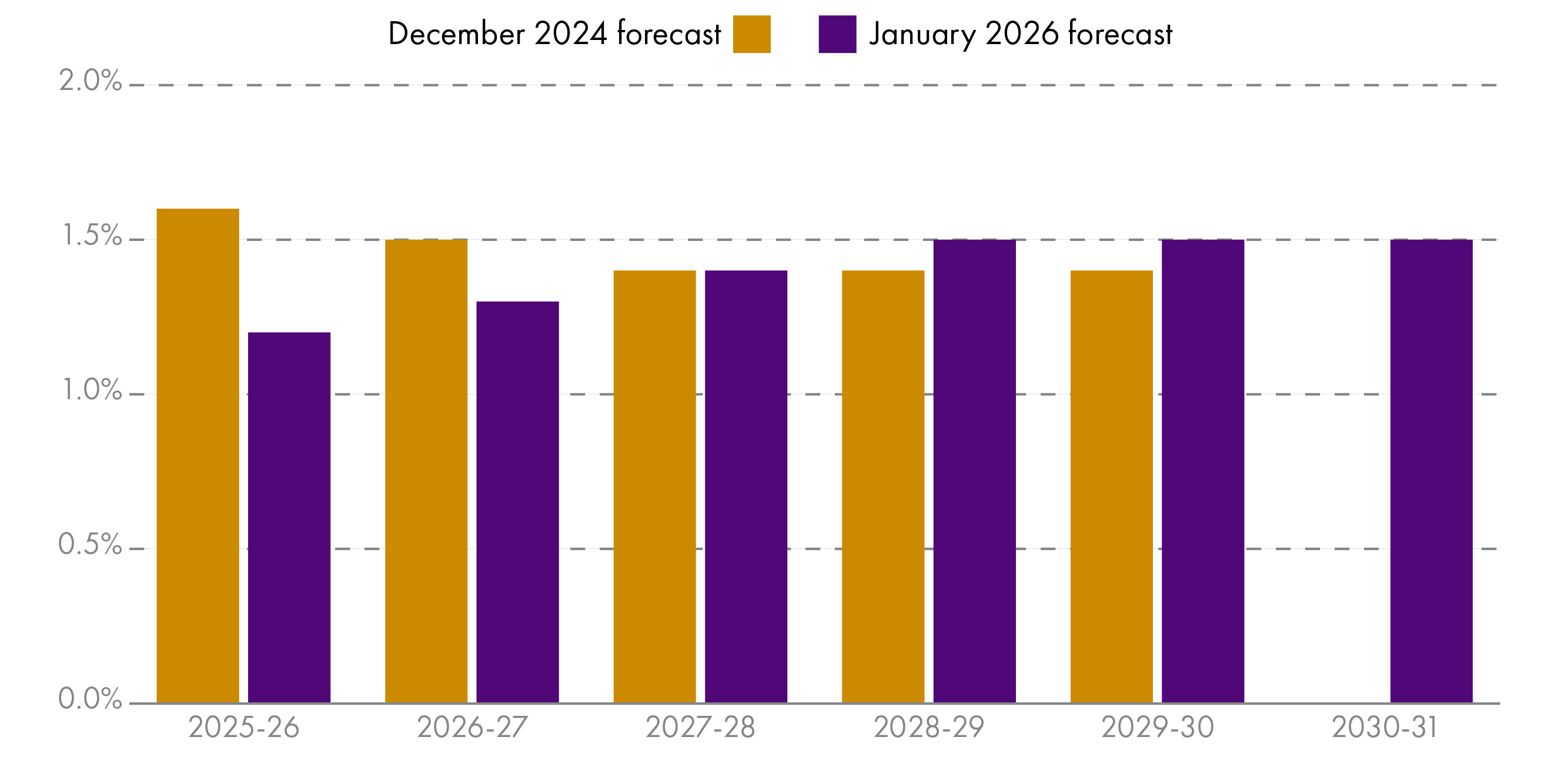

The SFC’s forecasts for Scottish GDP growth remain largely unchanged compared with previous forecasts.

Outturn data on GDP at the end of 2024 was lower than anticipated, which the SFC attributes to “global instability and higher consumer and business costs”. This means that GDP forecasts over the second half of this decade start from a slightly lower base.

But projected year-on-year growth rates are almost exactly the same, rising from 1.3% in 2026-27 to 1.4% in 2027-28 and 1.5% in each of the three remaining years of the forecast period. This puts Scotland’s growth trajectory on a path that is very similar to the OBR’s projections for the UK. By historical standards, these growth projections are unremarkable and around one percentage point per year lower than in the decade leading up to the 2008-09 financial crisis.

Productivity

Productivity is a measure of outputs for a given amount of inputs. An economy’s productivity performance matters because there is a strong link between increasing this metric and growing real wages and living standards over the long term. Economists have likened productivity to the economy’s ‘speed limit’.

Since the 2008-09 financial crisis, productivity growth in Scotland, the UK and much of Europe has slowed. What was initially billed as a slow recovery from the financial crisis has become the ‘new normal’. This has led to the OBR downgrading its forecasted productivity growth for the UK. The SFC is now forecasting a similar downgrade for Scotland (a reduction of 0.3 percentage points by 2029-30 to 0.9% growth per year).

This does not mean Scotland’s economic performance has suddenly worsened. Rather, the SFC’s forecasts have been brought more in line with recent data. However, the result is that the SFC’s economic forecasts are worse than would otherwise have been the case. Furthermore, the downgrade to projected productivity performance relates to longer-term economic trends, not one-off events, meaning that the impact of this productivity downgrade will filter through to future years’ economic forecasts too.

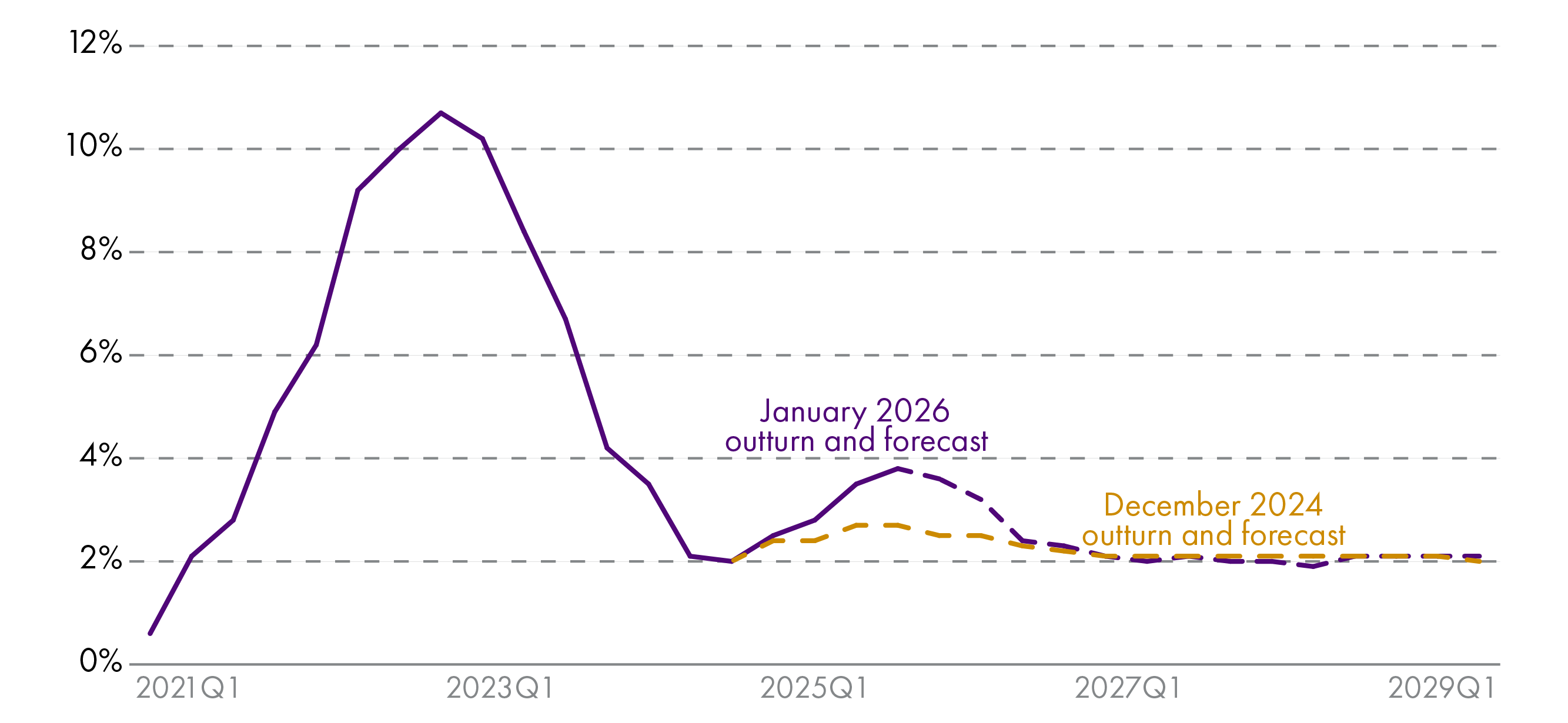

Inflation

High inflation has been a key factor in recent years’ budgets. Rising prices have put pressure on budgets for households and government departments alike, but have also been accompanied by high nominal earnings growth and a higher tax take, due to fiscal drag.

Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation is now at more ‘normal’ levels. During 2025-26, it has been slightly higher than the SFC had forecast, primarily due to higher food and services inflation. However, the SFC still forecasts that inflation will fall back to the Bank of England’s 2% target by 2027-28 after a period of elevated inflation since 2022.

Labour market and earnings

The SFC’s forecasts for Scotland’s labour market are in line with previous forecasts, although there is a slight worsening in the short term, which the SFC attributes to economic uncertainty and higher labour costs weighing on business confidence and labour demand.

Unemployment is forecast to oscillate around its structural trend of 4.1%. Employment is forecast to grow by 0.3% in each of the next three years, which the SFC says is in line with population growth.

Interestingly, economic inactivity (which measures those who are neither working nor looking for work) has now returned to close to its pre-pandemic levels. However, the composition of the economically inactive population has changed. Fewer people are economically inactive for reasons such as looking after family or home, but more people are economically inactive due to ill health.

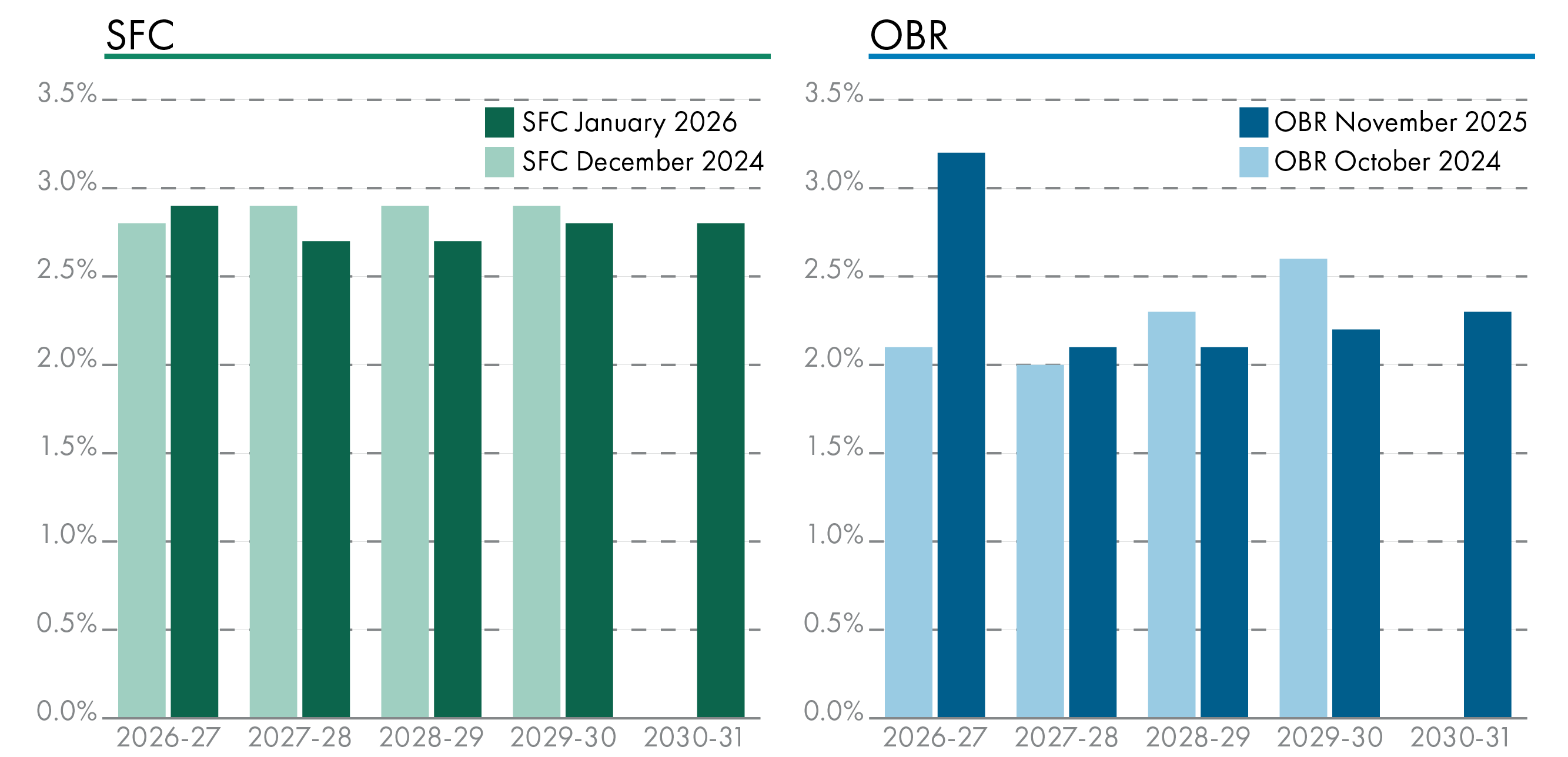

Perhaps the most substantive element of this part of the SFC forecasts is projected earnings growth, partly because it tells us about people’s material standard of living, but also because it feeds through to forecasted tax revenues for the Scottish Government.

Forecasted nominal earnings growth has remained broadly stable at 2.9% in 2026-27 and 2.7% in the two following years. The impact of lower productivity growth on projected earnings is partly offset by higher inflation in the short term.

However, the OBR’s forecasts for UK earnings growth have increased from 2.1% to 3.2% in 2026-27. The result is that earnings growth in Scotland in 2026-27 is forecast to be slightly lower than the UK average, for which the SFC highlights relatively weak earnings growth in the North East of Scotland.

This change to the outlook for relative earnings growth between Scotland and the UK matters because it affects the forecasted income tax net position. The result of the upward revision to the OBR’s forecasts for UK earnings is a lower than previously forecast income tax net position for 2026-27 of £969 million versus £1,314 million in previous forecasts.

It is worth noting here that the OBR continues to forecast lower earnings growth for the UK than the SFC forecasts for Scotland from 2027-28 – a continuation of a trend since December 2022. In each year since then, the OBR has upgraded its forecasted UK earnings to be more in line with the SFC forecasts for Scotland. This is important because if this trend continues, then future income tax net positions would not be as positive as currently forecast, meaning that funding for future Scottish budgets may be lower than currently planned for.

Portfolios at a glance

This section of the briefing gives an overview of each portfolio budget at a glance. Within each portfolio, we set out a breakdown of the budget, the change in the overall portfolio since the 2025 Autumn Budget Revision and compared to the Scottish Budget as a whole, the five largest level 3 budget lines, and the five largest changes at level 3.

These breakdowns are listed in order of size from the largest to the the smallest. Note that only Cabinet Secretary portfolios are included, meaning that those covering administrative function are not (Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service, Scottish Government and Scottish Parliament and Audit Scotland).

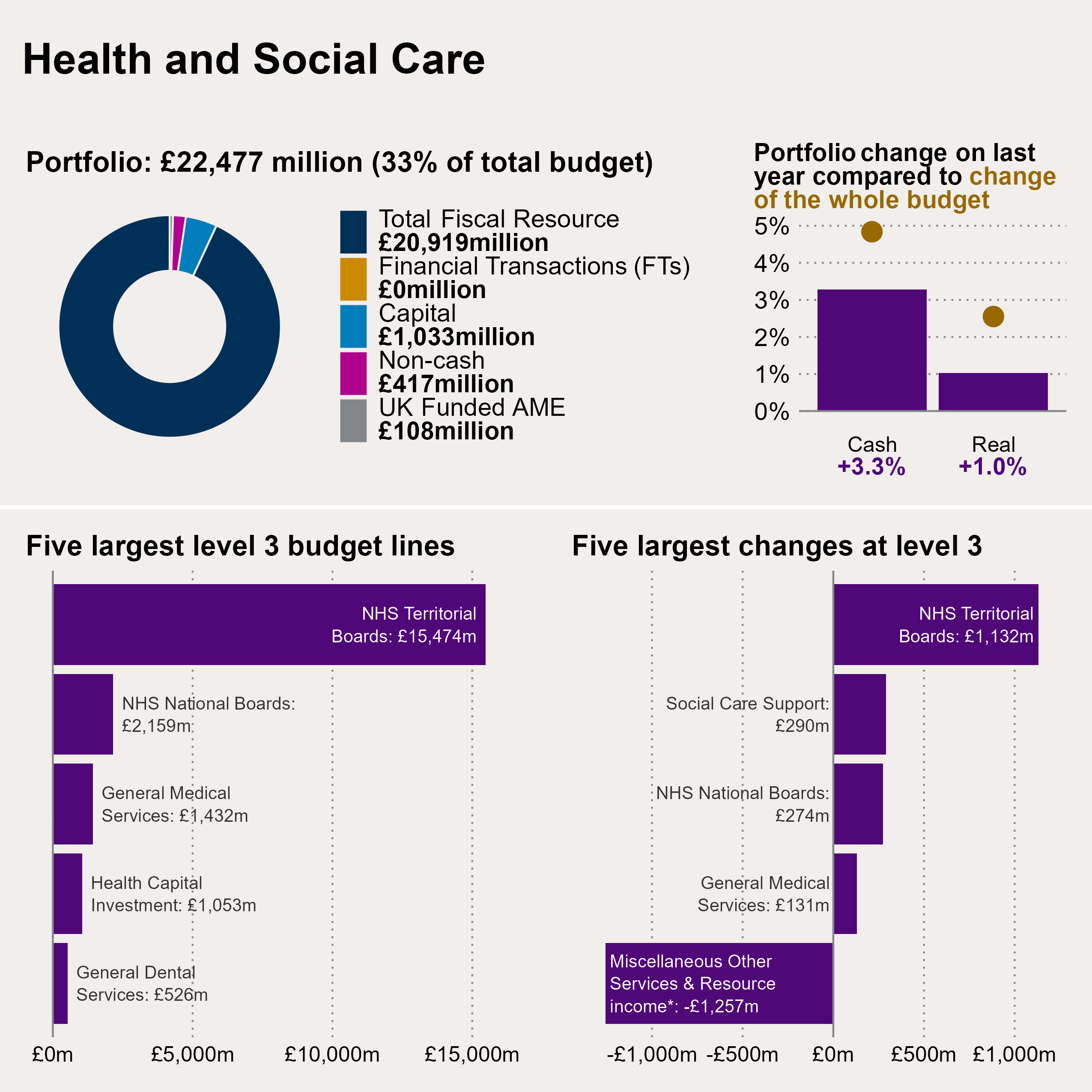

Health and Social Care

The Health and Sport portfolio remains the largest across the Scottish budget, at just under £22.5 billion, and increases by 1% in real terms when compared to Autumn Budget Revision 2025-26 figures.

There is a £1.4 billion uplift for health board budgets, a 6.3% real terms increase on ABR 2025-26 funding, though much of this beyond a 2% baseline uplift will go towards pay settlements and other reforms as part of the pay settlements.

Capital Funding for Health and Social Care has fallen by 6.6% in real terms from the ABR 2025-26 baseline.

The Spending Review 2026 sets out plans for overall health budget increases of 3.8% and 4.9% over 2027-28 and 2028-29 respectively, but more modest health board increases of 2.6% and 2%.

There is evidence of investment in preventative measures and service reform in funding for sport and activities, education and training, digital health and care, quality and improvement and mental health services.

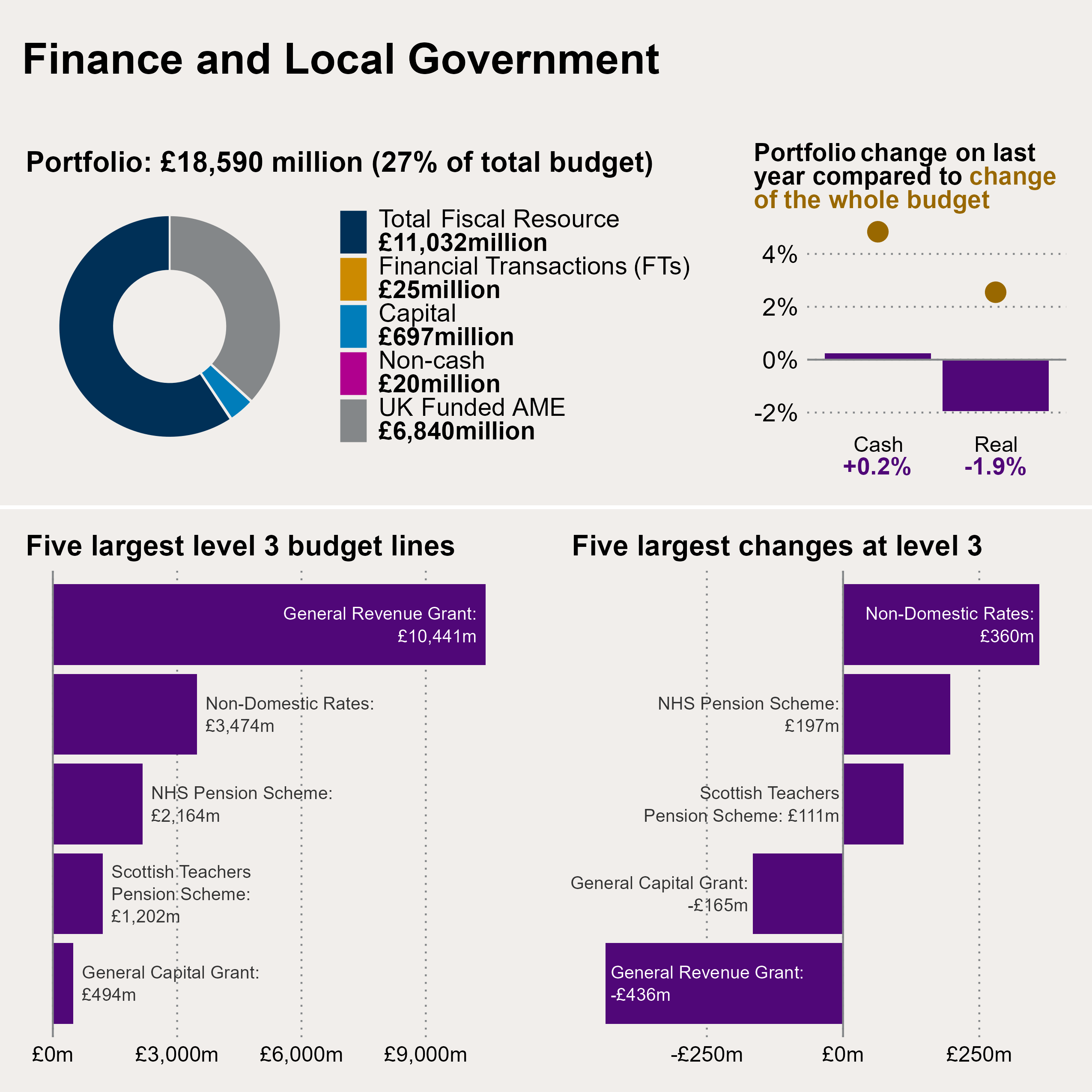

Finance and Local Government

This portfolio accounts for just over a quarter (27%) of the total Scottish Budget, with the vast majority accounted for by funding for local government. Local government receives significant in-year allocations of funding, so the apparent reductions in budget for this portfolio should be interpreted with caution.

Non-Domestic Rates (NDR) are an important source of revenue for local government, at around £3.5 billion in 2026-27. The amount of NDR going to local government increases significantly over the year (up £360 million), reflecting a revaluation of non-domestic properties taking effect. NDR revenues are included under the “UK Funded AME” category, along with NHS and teacher pension schemes.

The largest reduction in this portfolio area is in the local government’s General Revenue Grant, when comparing 2025-26 Autumn Budget Revision (ABR) figures with the Budget. However, when comparing the 2025-26 Budget with the 2026-27 Budget, the General Revenue Grant actually increases by 10% in cash terms.

This difference illustrates the extent to which local government receives additional funding in-year, and the challenges in making comparisons between years depending on the baseline used. This is explained in more detail in the Local Government section of the briefing.

The 2026-27 Budget provides a General Capital Grant of £494 million for local government, which is a 27% reduction in real terms on 2025-26 when using the ABR baseline. Again, this comparison is affected by the baseline used, with a smaller 13% reduction when a budget-to-budget comparison is used.

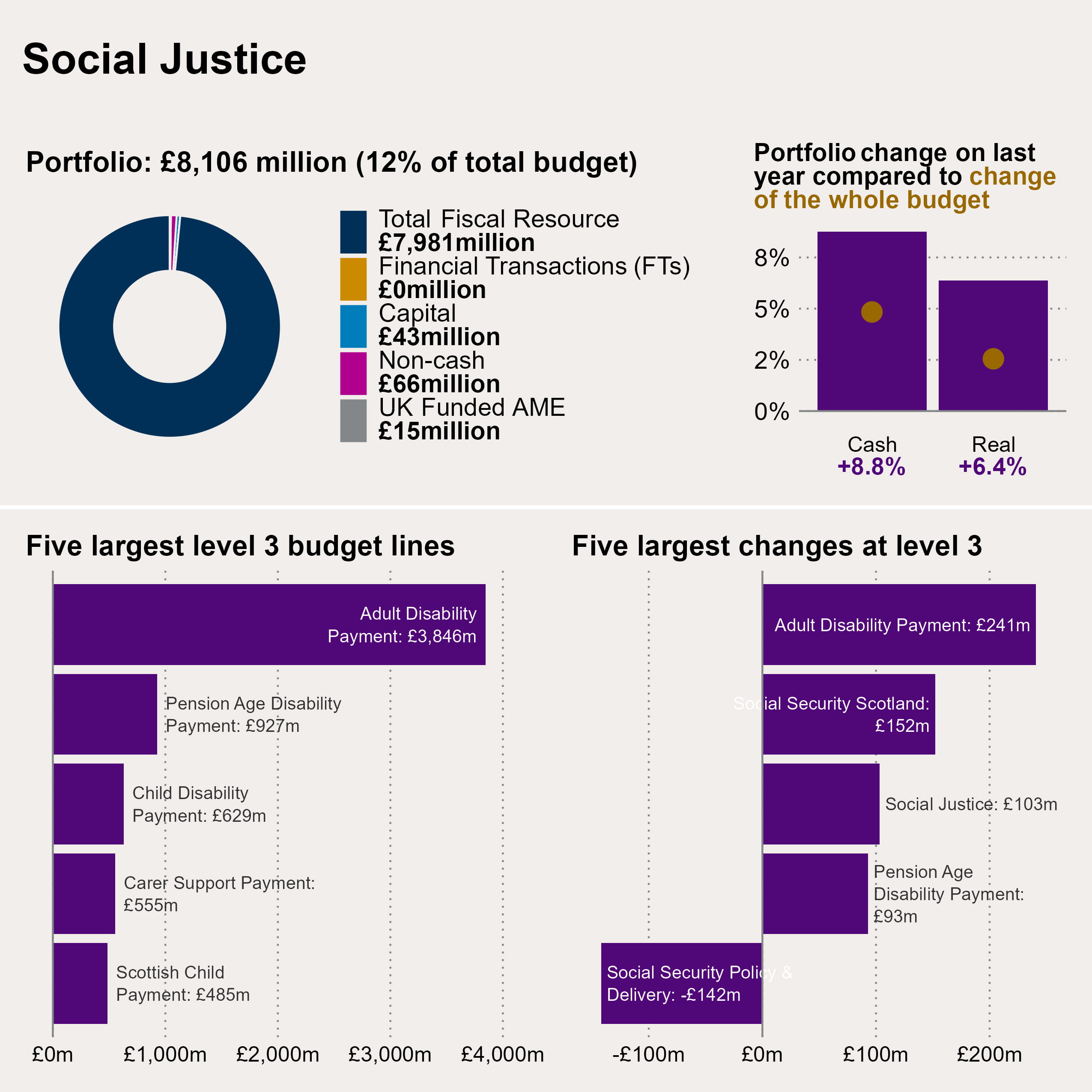

Social Justice

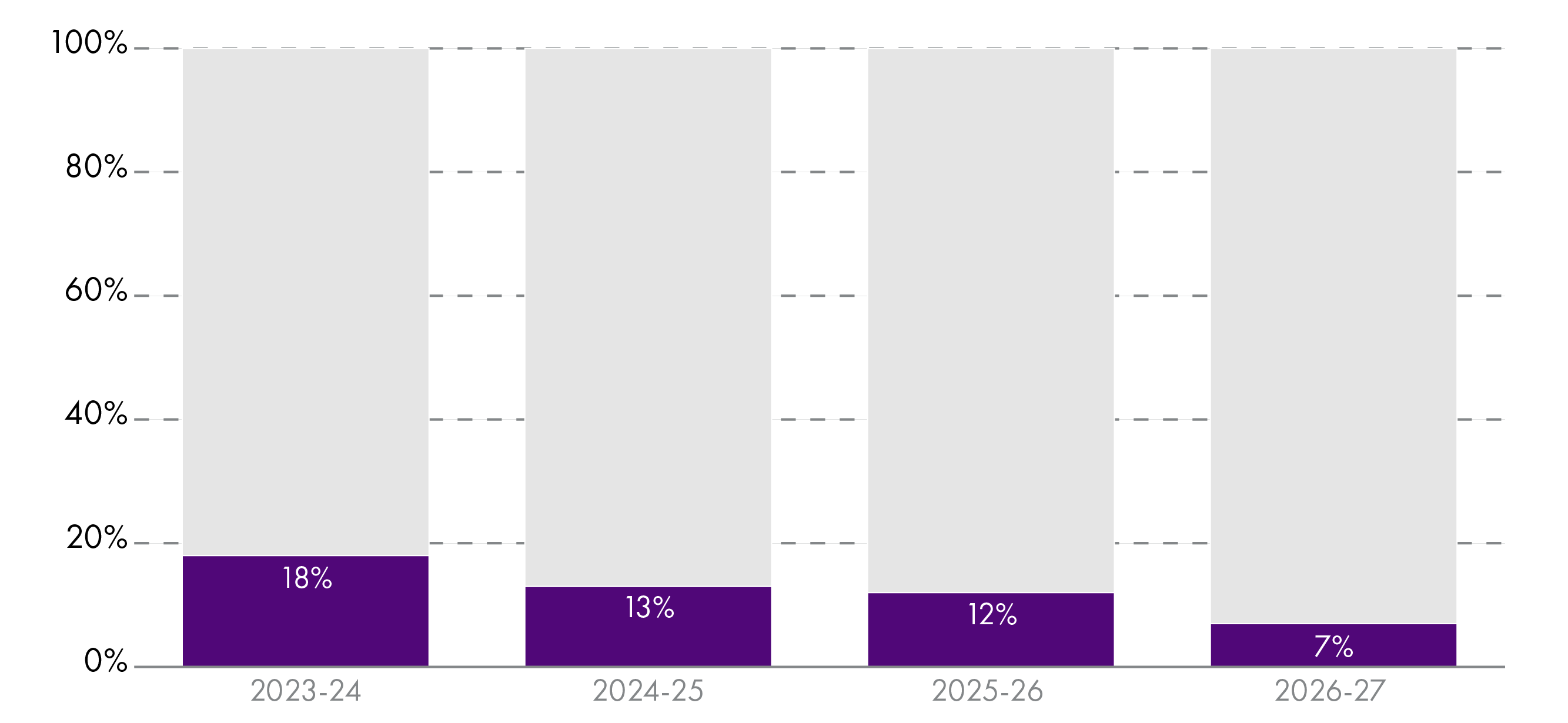

The Social Justice budget predominantly funds devolved benefits spending. In real terms, it is set to rise by 6.4%, which is two-and-a-half times as fast as the overall budget growth in 2026-27.

Spending on Social Justice was 14.1% of the total resource budget in 2024-25. In 2026-27, it is set to be 15.8% of the resource budget. The three-year Scottish Spending Review implies that social security spending will account for a growing share of total spending.

Increased spending on the Adult Disability Payment is the single largest year-on-year increase, driven by higher caseloads. The announced increase in the Scottish Child Payment (SCP) for under-ones will not take effect until 2027-28 and will only have a modest impact on costs (around £7 million per year).

Spending on devolved benefits above UK Government equivalent-spending and on benefits unavailable in the rest of the UK (e.g. the SCP) do not attract Block Grant funding from the UK Government. This must be funded from within the Scottish budget and is forecast to reach £1 billion in 2026-27.

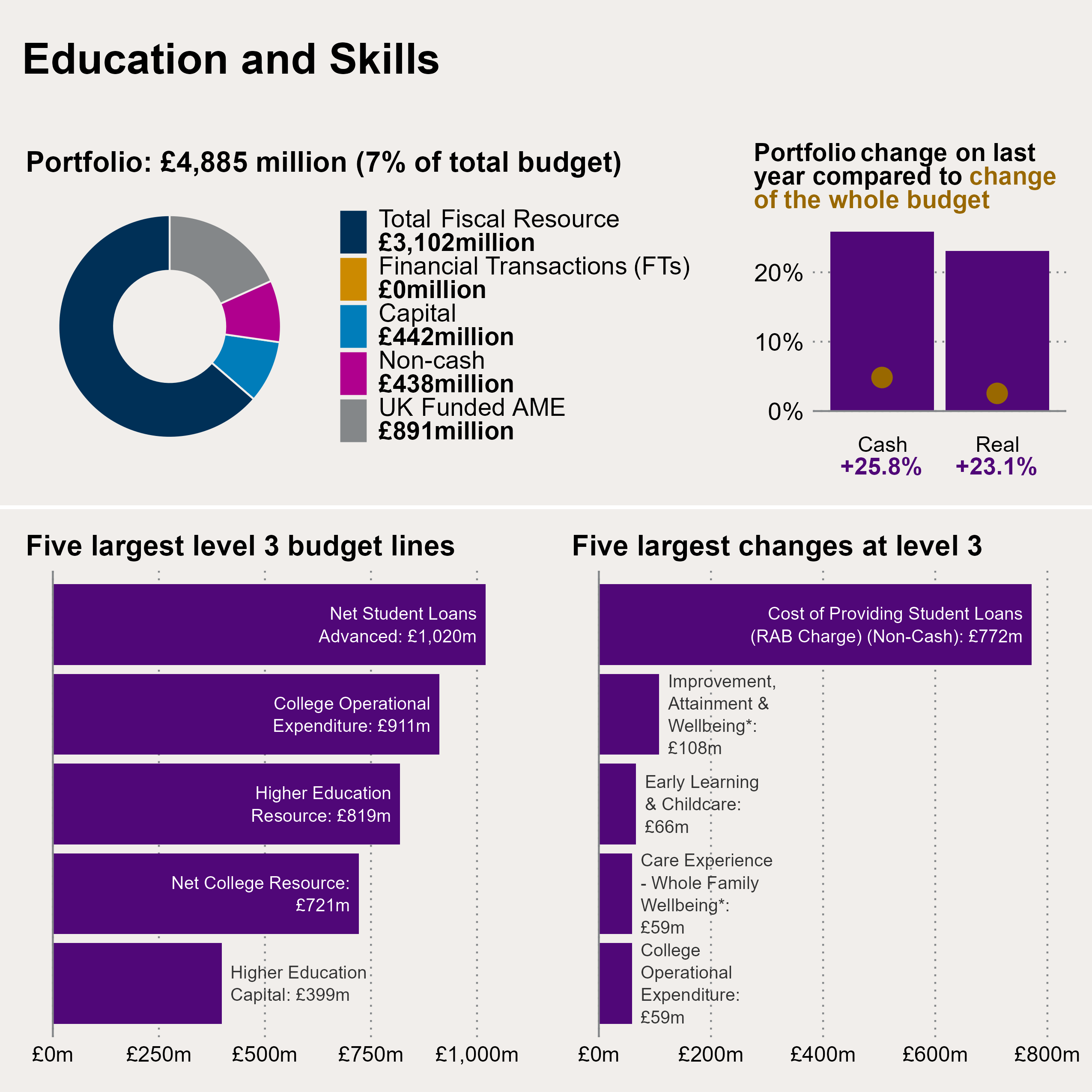

Education and Skills

The Education and Skills portfolio sees a cash terms increase of 25.8% from £3,882 million to £4,885 million between the 2025-26 ABR and 2026-27 Budget. This equates to a real terms increase of 23.1%. However, the use of the ABR baseline makes a significant difference. When compared to the 2025-26 Budget, the increase is 15.2% in cash terms and 12.7% in real terms.

Whilst the Education and Skills portfolio shows an increase overall, it does include a decrease in overall capital (including financial transactions) of -3.9% in cash terms and -6.0% in real terms.

The Scottish Government says college funding will rise by £70 million in 2026‑27—a 10% increase, but a figure that cannot be replicated from the published budget figures. The Scottish Government has confirmed that this calculation is based on excluding funding for the Dunfermline Learning Campus from the figures.

The significant increase in the RAB charge relating to student loans is a non-cash figure which does not affect discretionary spending.

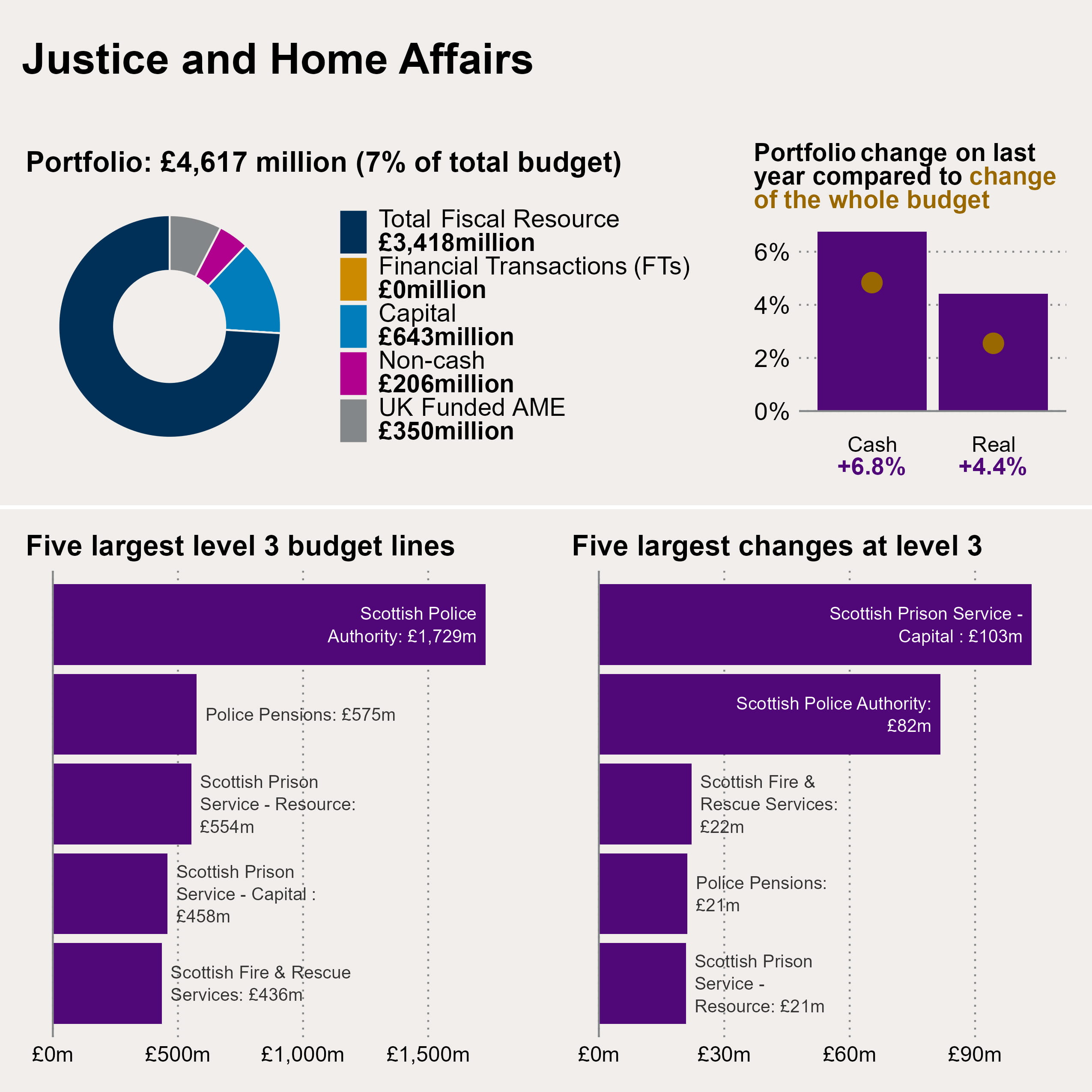

Justice and Home Affairs

The Justice and Home Affairs Portfolio is allocated £4.6 billion in the 2026-27 Budget, which is 7% of the total budget. Resource funding comprises the majority (74%) of this funding, but there is also a significant capital allocation of £643 million, and £350 million UK Funded AME which relates to police and fire pensions.

The largest level 3 budget allocation within the portfolio is to the Scottish Police Authority. The 2026-27 Budget provides £1.7 billion, which is an increase of £81 million since the 2025-26 Autumn Budget Revision position.

While Police Pensions are the second largest allocation, this is not an area the Scottish Government has much discretion. The Scottish Government funds employer contributions from its resource budget, but following a reclassification announced in the 2025 UK Budget the balancing payments are now funded by UK-funded AME. This means the Scottish Government will no longer need to fund balancing payments.

The Scottish Prison Service capital budget is set to grow significantly, by £103 million in 2026-27. This increase is largely to fund HMP Glasgow and HMP Highland capital projects.

The Criminal Justice Committee in its pre-budget report, made specific recommendations for the level of funding for the five public justice bodies within the portfolio (Police Scotland, Scottish Fire and Rescue Service, Scottish Prison Service, Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service, and the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service (COPFS)). Of the five, only COPFS received a total budget settlement of the size requested.

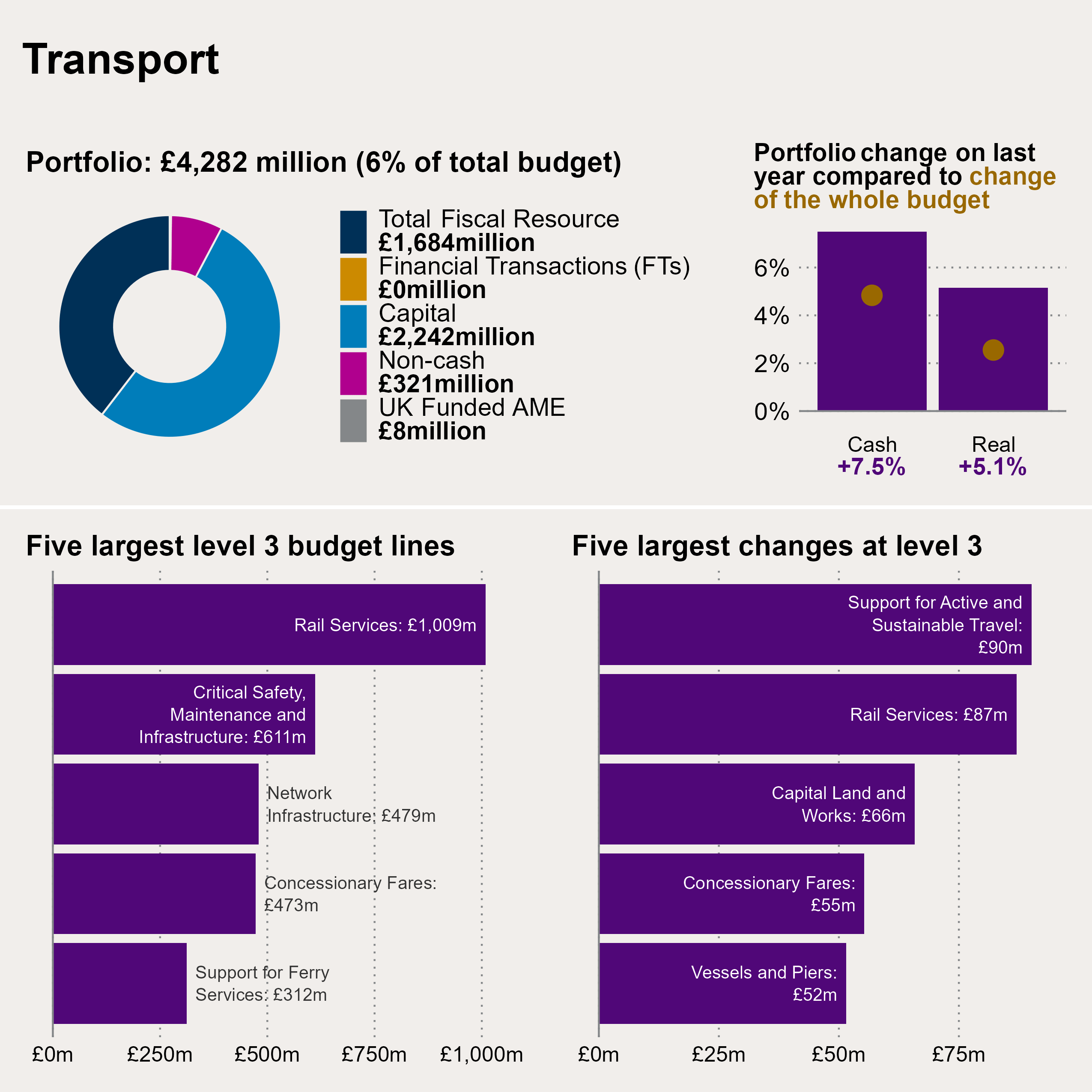

Transport

The Transport portfolio accounts for the largest share of total capital spending (31.3% of the capital budget), with an 8% real terms increase in the transport capital budget from 2025-26 to 2026-27.

This year’s Budget allocated £223 million to Capital Land and Works (for design, development and delivery of trunk road schemes), a significant change of 41.8% compared to 2025-26 Budget. This largely reflects more sections of the A9 dualling programme entering delivery stage. The Transport Secretary confirmed the remaining sections of the programme will be delivered using capital funding, rather than via a public-private partnership.

The budget for Rail Services is up 7% in real terms. This includes funding for the ScotRail and Caledonian Sleeper passenger rail services as well as funding for permanent removal of peak fares.

This year’s budget saw additional funding for affordable and accessible public transport (up 63% in real terms). This includes the Active Travel Infrastructure Fund and Bus Infrastructure Fund.

The Scottish Government increased the Concessionary Fares budget with a additional funding of £55 million. This includes a pilot scheme for a £2 bus fare cap in the Highland and Islands, free bus travel for under 22s and Older and Disabled People Schemes.

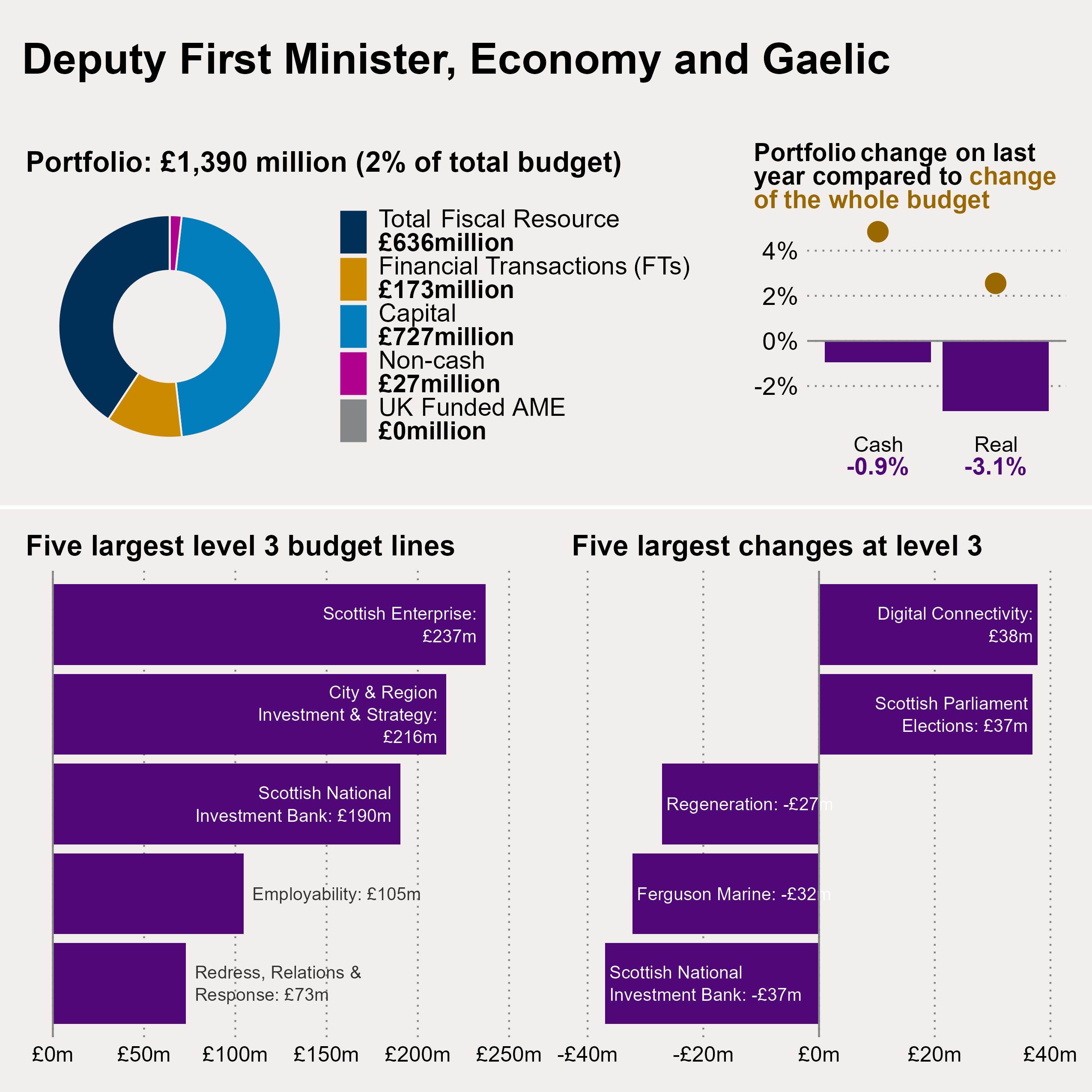

Deputy First Minister, Economy and Gaelic

When compared with Autumn Budget Revision 2025-26 figures portfolio capital funding has decreased by 11.1% in real terms whilst resource funding has increased by 7.6% in real terms. Meanwhile, overall capital funding has decreased –0.3% whilst resource funding has increased 0.2%.

The largest percentage increases in the 2026-27 Budget relate to Major Events (up 245% in real terms) and Government Business and Constitutional Relations Policy and Co-ordination (up 588% in real terms). This is due to a number of events including the 2027 Tour de France Grand Depart, EURO 2028 and Local Government and Parliamentary Elections.

Innovation, Entrepreneurship and International Trade and Investment shows a substantial increase of 28% in real terms, largely to support the Techscaler programme.

Digital Connectivity also sees a large increase (111% in real terms) which largely reflects the fact that one-off income was received in 2025-26 as part of the Gainshare agreement with BT. Elsewhere in this budget line, spending as part of the R100 broadband programme has declined.

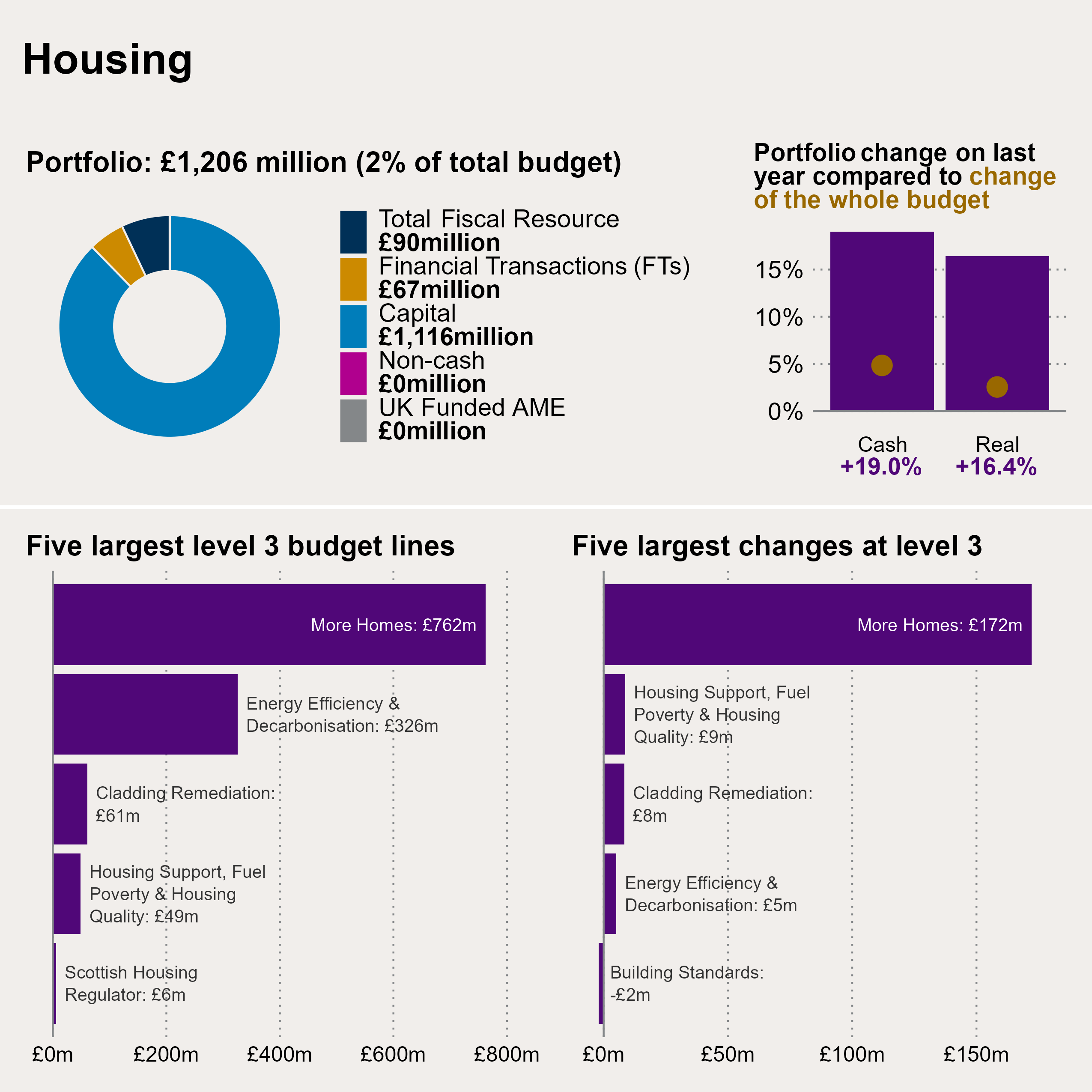

Housing

The Housing portfolio budget line is increasing by 19% in cash terms (16.4% in real terms), much faster than the overall increase in the Scottish budget.

This is largely driven by a £172 million increase in the “More Homes” budget line, which is one part of the budget for delivering more affordable homes in Scotland. The Scottish Government is planning to deliver 110,000 affordable homes by 2032.

There is also money in the Local Government settlement that is aimed at supporting delivery of the affordable homes target. This budget (the “Transfer of Management Development Fund”) totals £92.2 million in 2026-27, unchanged from the previous two financial years.

The Spending Review published alongside the 2026-27 Budget also identifies further growth in the Housing budget, with investment totalling £5.3 billion over the next four years across the portfolio. Again, this is faster growth than in other budget areas. Within this total, £4.1 billion is aimed at delivering 36,000 affordable homes over the Spending Review period.

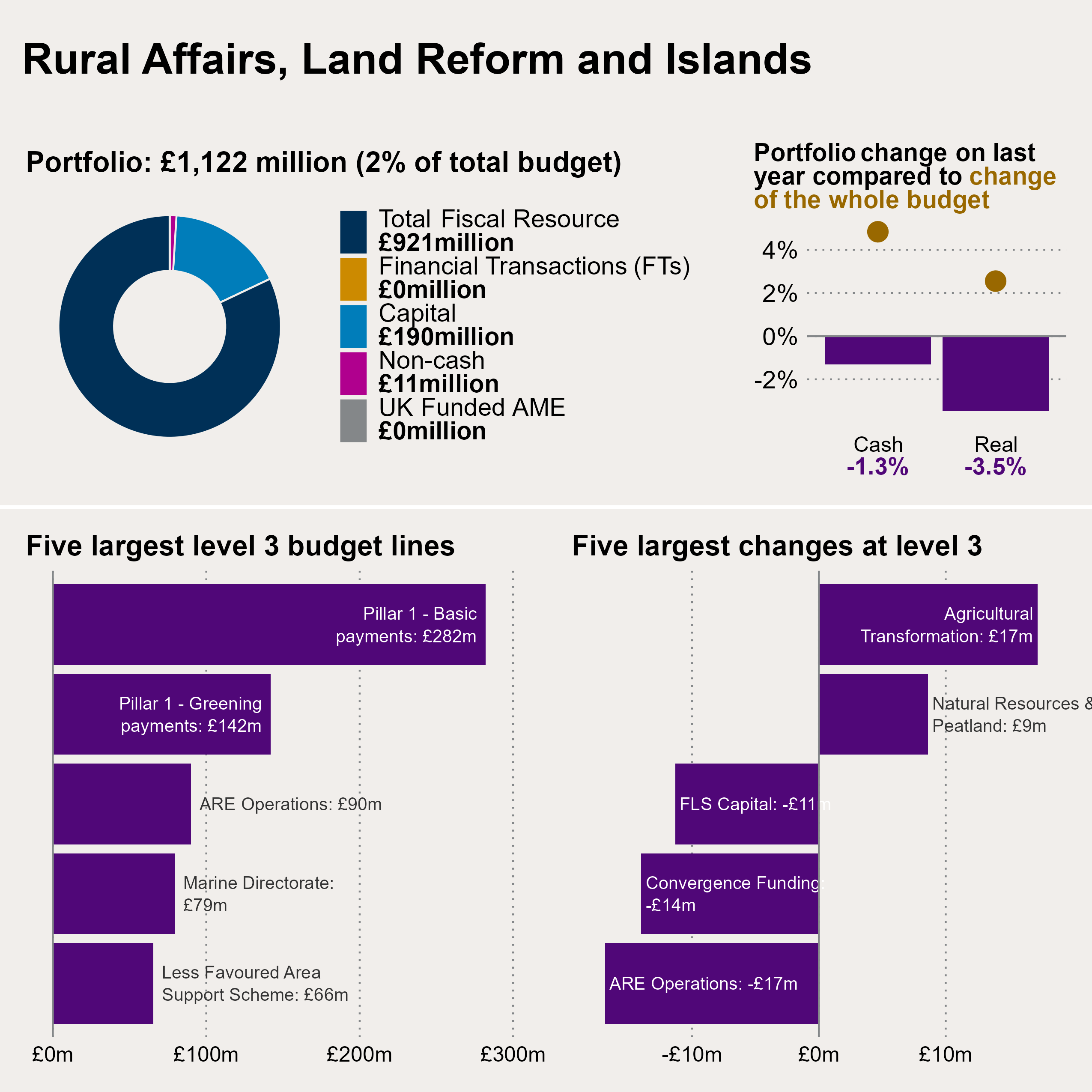

Rural Affairs, Land Reform and Islands

Last year, the RALRI budget was the only portfolio to see a nominal terms decrease. It is set to be reduced in nominal terms again, which means its spending power will continue to be eroded by inflation.

The major support schemes for farmers continue to be broadly frozen in cash terms. There is more funding for the Crofting Commission, the food and drink industry, the marine environment, and Edinburgh’s Botanic Gardens; with less funding for Islands, land reform, national parks and research – but all these year-to-year changes are individually within £5 million.

In the capital budget, peatland restoration is set to receive a £6.5 million boost. Steep reductions for Forestry and Land Scotland (£11.3 million or 88% in cash terms) are partly offset by Scottish Foresty’s funding for woodland creation increasing by £5.6 million. However, even this remains around a third (£17.3 million) lower than was proposed in the 2023-24 budget.

The apparent increase in ‘Agricultural Transformation’ is expected to largely net off against the decrease in ‘Convergence Funding’, as money is intended to be transferred between these budget lines in-year.

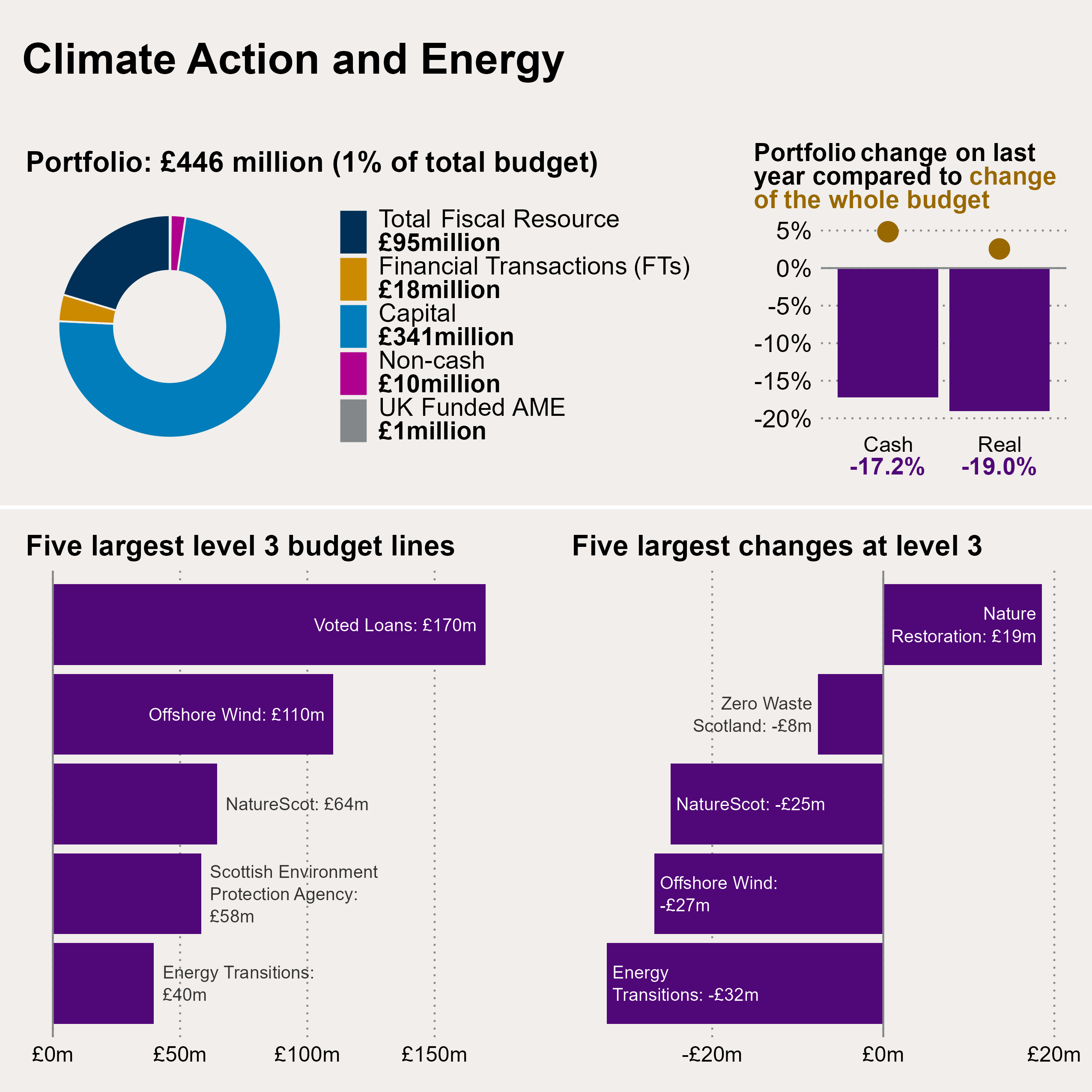

Climate Action and Energy

The Climate Action and Energy portfolio sees the largest percentage decline of all the portfolios (19.0% in real terms). This is a capital-heavy portfolio, which provides funding to support decarbonisation and clean energy, as well as funding for public bodies including Scottish Water, SEPA, NatureScot, and Zero Waste Scotland.

The largest level 3 budget line is the £170 million in voted loans – this is the funding that the Scottish Government provides to Scottish Water to cover their investment programme, and is unchanged on last year.

While offshore wind is the second largest level 3 allocation within the Climate Action and energy portfolio, funding declines by £27 million. This is largely due to a £31 million reduction in the capital funding, which the Scottish Government suggests is to reflect market demand, partly offset by an increase in funding to deliver a new skills action plan.

The largest reduction in funding is to the energy transitions budget, with a reduction of £32 million. This funding is to support industrial decarbonisation, including support for carbon capture, utilisation and storage, and for the just transition in Grangemouth. The Scottish Government states that this reduction in funding is consistent with the draft Climate Change Plan published in November 2025.

The budget for nature restoration increases by £19 million in 2026-27 – this however is largely due to the baseline comparison issue discussed elsewhere in this briefing. In the Autumn Budget Revision, funding is transferred to partner organisations from this Budget, so the ABR position is lower than the opening budget. So, while the budget appears to increase, the Scottish Government explains that this maintains the opening budget position from 2025-26.

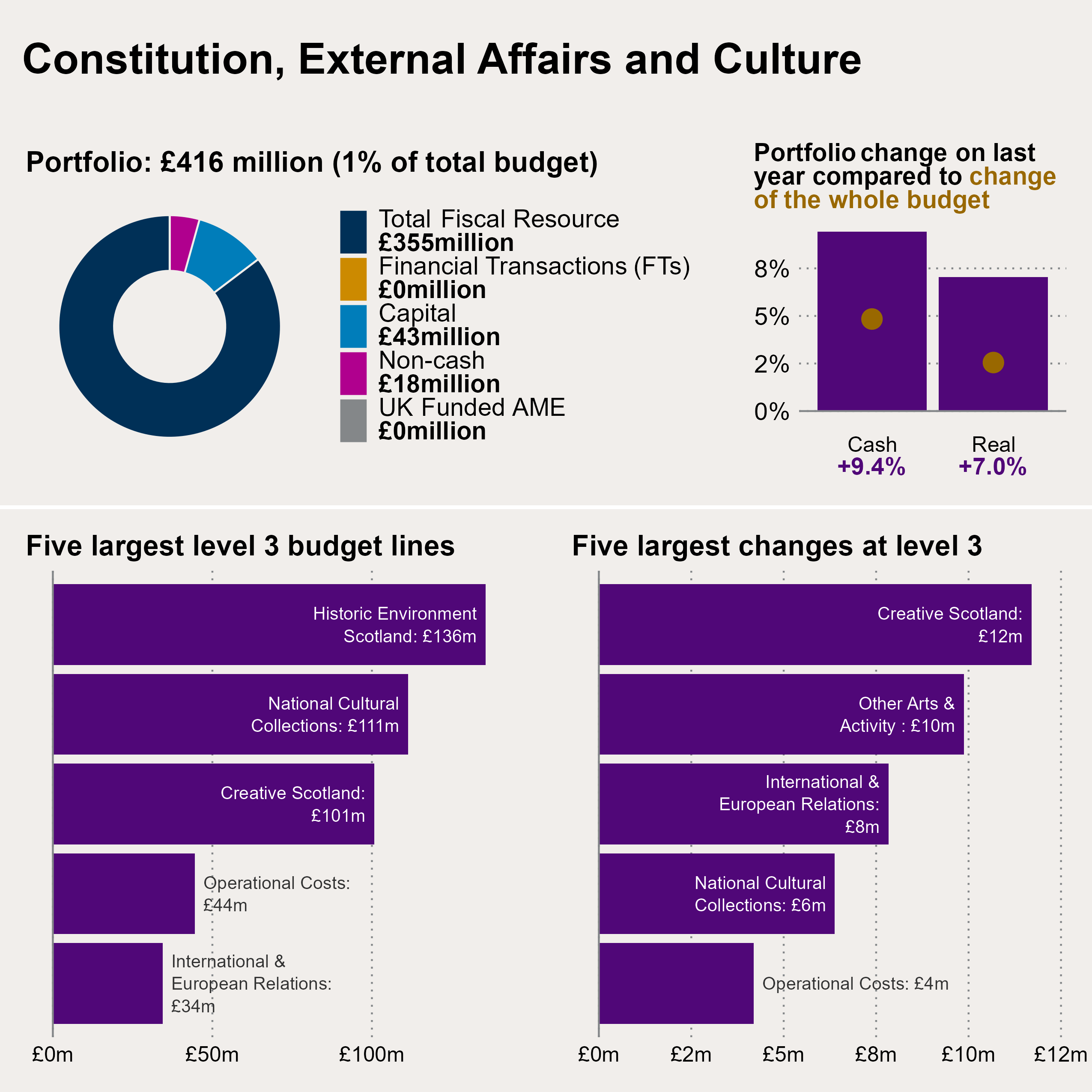

Constitution, External Affairs and Culture

This year’s budget allocated £415.8 million to the Constitution, External Affairs and Culture portfolio. This is an increase of 7% in real terms when compared to Autumn Budget Revision 2025-26 figures.

When comparing the Creative Scotland 2026-27 Budget to the Autumn Budget Revision 2025-26 figures, the budget increases by 13% cash terms. However, when comparing the 2025-26 Budget with the 2026-27 Budget, Creative Scotland has seen a larger increase in its budget of £20 million, bringing the total funding pot for Creative Scotland for 2026-27 to just over £100 million (this is a 26% increase in cash terms). This difference illustrates how some budgets can change significantly through the financial year and the impact that the choice of baseline makes.

Ahead of the 2025-26 budget, Historic Environment Scotland agreed a new funding model with the Scottish Government. One component of this is that they accept an accumulating decrease in Scottish Government grant-in-aid (GIA) of £2 million per annum each year for five years.

The International and European Relations budget has seen a 27% real terms increase. This includes £3 million to support the International Development budget which increases to £16 million. This increased funding implements the commitment in the Programme for Government (May 2025) to grow the international development fund to £15 million per annum and providing £1 million for humanitarian crises.

Local Government

The problem of what to compare Budget 2026-27 to is perhaps most obvious when considering the local government portfolio. The Budget document presents 2026-27 plans alongside Autumn Budget Revision (ABR) figures for 2025-26, reflecting requests from the Parliament’s Finance and Public Administration Committee that the baseline should reflect the latest budget position. However, for some budget areas, including the local government budget, this is problematic, as there are always transfers to local government in-year. Many of these are included in the ABR but not the Budget, and the ABR for 2026-27 won’t be published until much later in the year. As such, comparisons of Budget with ABR can be misleading as the baseline will reflect in-year transfers, while the Budget won’t.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies contacted SPICe before the publication of this briefing in relation to Budget-to-Budget comparisons of local government funding. They make the point that a Budget-to-Budget comparison “flatters the actual change in spending power of councils” (personal correspondence). This is because the Budget 2025-26 figures do not include additional funding that was formally confirmed in the 2026 ABR to cover Employer NICs costs and pay deals – costs which are recurrent and will have to be funded by the initial Budget allocations for 2026-27. As such, this section includes analysis of Table A.09 in the Budget document which sets out the most recent position for 2025-26, minus transfers that have not been baselined.

Revenue allocation

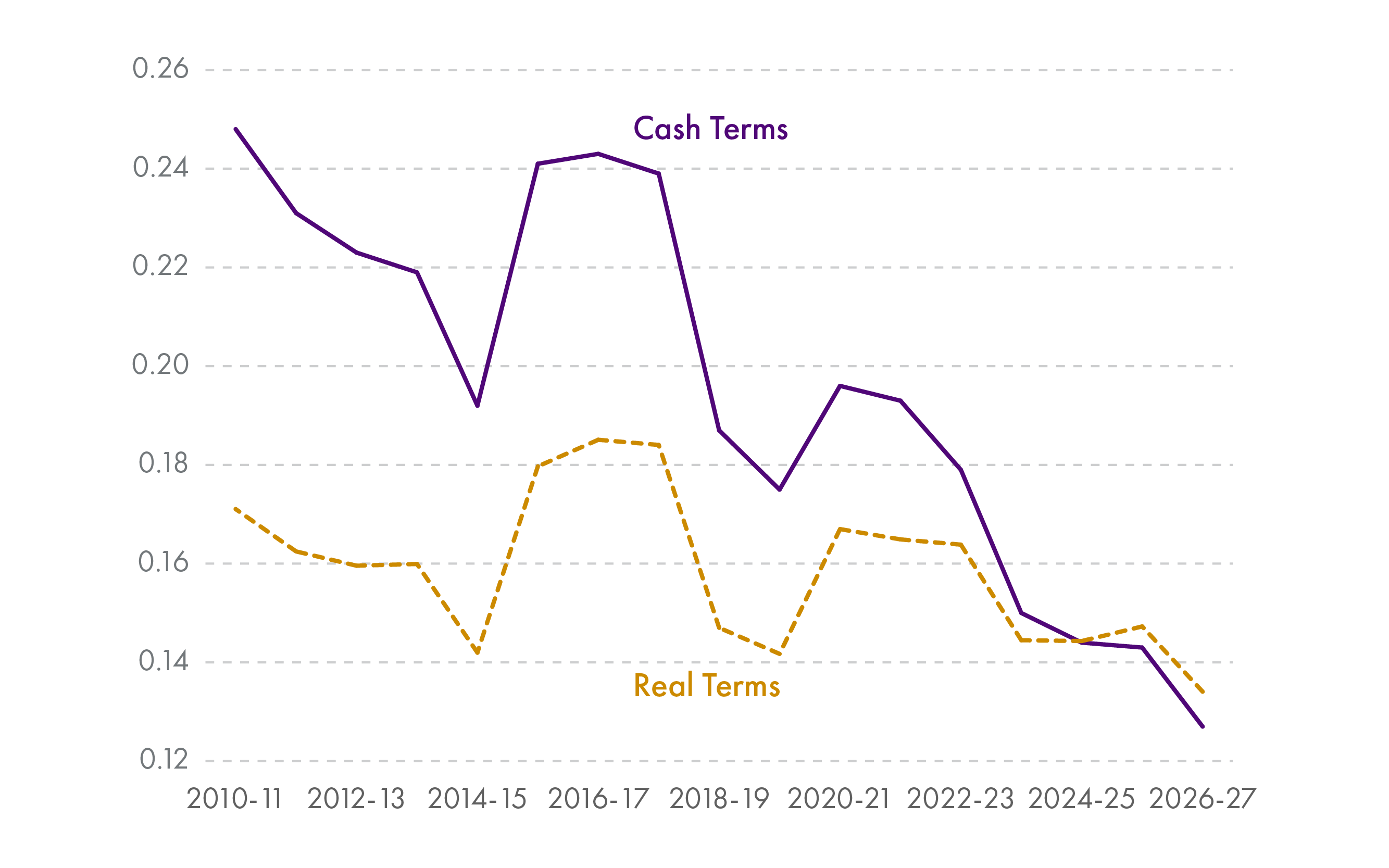

Comparing Budget document 2026-27 to the previous Budget document, as SPICe has done in the past, we see both cash and real terms increases in the overall revenue allocation to local government (see Tables 2 and 3).

| Local Government (Revenue) | 2025-26 Budget document | 2026-27 Budget document | Cash change (£m) | Cash change % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Revenue Grant | 9,458.4 | 10,440.7 | 982.3 | 10.4% |

| Non-Domestic Rates | 3,114.0 | 3,474.0 | 360.0 | 11.6% |

| Specific (ring-fenced) Resource Grants | 247.4 | 222.4 | -25.0 | -10.1% |

| Revenue within other portfolios | 1,438.3 | 867.7 | -570.6 | -39.7% |

| Total revenue for LG | 14,258.1 | 15,004.8 | +746.7 | +5.2% |

Due to previously announced commitments, such as fully funding the Real Living Wage for early learning and social care workers, COSLA argues that the actual increase in uncommitted revenue funding is closer to £235 million.

When adjusting for likely inflation, we can see that the local government revenue settlement increases by £419 million, or +2.9%, in real terms over the year.

| Local Government (Revenue) | 2025-26 Budget document | 2026-27 Budget document | Real change (£m) | Real change % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Revenue Grant | 9,458.4 | 10,213.0 | 754.6 | 8.0% |

| Non-Domestic Rates | 3,114.0 | 3,398.2 | 284.2 | 9.1% |

| Specific (ring-fenced) Resource Grants | 247.4 | 217.5 | -29.9 | -12.1% |

| Revenue within other portfolios | 1,438.3 | 848.8 | -589.5 | -41.0% |

| Total revenue for LG | 14,258.1 | 14,677.5 | +419.4 | +2.9% |

The past three Budgets have all included real terms increases for the local government revenue settlement. However, COSLA argues that these increases have not been enough to meet the needs of local authorities and the increasing demands on their services. Prior to the Budget, COSLA called for a revenue settlement of £16 billion in 2026-27, including an additional £750 million for social care. So, the 2026-27 settlement is almost a billion short of what they asked for.

More on the ABR to Budget comparison

The Scottish Budget document includes an additional table which shows the Autumn Budget Revision (ABR) figures for 2025-26 without transfers that have not been baselined into 2026-27. In the Institute for Fiscal Studies’ opinion, the figures in Table A.09 represent “a major improvement”. The figures are not broken down beyond the “Finance and Local Government” heading, but the vast majority of funding included is for local government.

| Finance and Local Government | 2025-26 ABR (minus non-baselined transfers) | 2026-27 Budget | Change (£m) | Change (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cash terms | 14,154 | 14,506 | +352 | +2% |

| Real terms (2025-26 prices) | 14,154 | 14,190 | +36 | +0.3% |

This table appears to support the IFS’s argument that local government’s spending power is increasing by a far smaller amount than the Budget-to-Budget comparison would suggest.

Council tax in 2026-27

The Budget did not include any surprise council tax-related measures, such as a freeze or cap. So, councils are free to increase bills by as much as they see fit in 2026-27. The Cabinet Secretary told the Parliament:

Decisions on council tax rates will, of course, be taken locally. However, this is a reasonable deal and, given the cost of living pressures that we all recognise, I urge local authorities to translate the settlement into reasonable decisions on council tax.

A recent Local Government Information Unit survey of council leaders, chief executives and senior finance officers found that every respondent intends to reduce spending on services and increase council tax in 2026-27. The report concludes:

The scale of council tax increases continues to be significant. Not only is every council planning to raise council tax, every council is planning to raise it by at least 5%. Over a fifth plan to raise council tax by over 10%.

All 32 local authorities increased their council tax in 2025-26, with increases ranging from 6% in South Lanarkshire to 15.6% in Falkirk.

New council tax bands from 2028

The UK Budget in November included plans to introduce a council tax surcharge on properties in England valued above £2 million from 2028, dubbed a ‘mansion tax’. The Scottish Budget includes a proposal to introduce two new tax bands for properties valued above £1 million from April 2028. Band I will apply to properties valued between £1 million and £2 million, and Band J will apply to those valued above £2 million.

The Scottish Government notes this will be based on an ‘up to date’ valuation of those properties, not the 1991 value that is used to calculate council tax liability currently. This suggests that a partial, targeted revaluation will be required to determine liability for the new bands, with the Budget setting aside £5 million to carry this out. The Scottish Government suggests this will affect fewer than 1% of properties.

A COSLA source told SPICe (personal correspondence) that their understanding based on very initial information from the Scottish Government is that the new policy could raise between £12 million and £16 million annually. The cost of a targeted revaluation is estimated to be around £10 million, albeit this would be a one-off cost.

Verity House agreement

There are some positives for local government in the Budget, including a significant reduction in the proportion of the revenue allocation that is either ring-fenced for specific purposes or transferred in-year from other portfolios (often seen by local government as a form of ringfencing). In light of the commitment in the 2023 Verity House Agreement to work towards “no ring-fencing or direction of funding”, this Budget shows a significant move forward.

The Verity House Agreement also stated that “wherever possible multi-year certainty will be provided to support strategic planning and investment”. The publication of the Scottish Government’s Spending Review alongside the Budget document, may provide some degree of certainty to local government. This shows that the core revenue settlement increases initially in 2026-27 but then falls slightly in real terms over the following two years.

Capital allocation

COSLA also wanted to see a General Capital Grant (GCG) of £844 million in 2026-27. Instead, the Budget provides a GCG £494 million. The overall capital allocation from the Scottish Government continues to fall, decreasing by 14.2% in real terms over the year, which will be a disappointment to many in local government.

| Local Government (Capital) | 2025-26 Budget document | 2026-27 Budget document | Cash change (£m) | Cash change % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Capital Grant | 556.0 | 493.7 | -62.3 | -11.2% |

| Specific (ring-fenced) capital grants | 196.1 | 147.7 | -48.4 | -24.7% |

| Total "core" Capital | 752.1 | 641.4 | -110.7 | -14.7% |

| Capital Funding within other Portfolios | 25.0 | 40.0 | 15.0 | 60.0% |

| Total capital for LG | 777.1 | 681.4 | -95.7 | -12.3% |

| Local Government (Capital) | 2025-26 Budget document | 2026-27 Budget document | Real change (£m) | Real change % |

| General Capital Grant | 556.00 | 482.93 | -73.1 | -13.1% |

| Specific (ring-fenced) capital grants | 196.10 | 144.48 | -51.6 | -26.3% |

| Total "core" Capital | 752.1 | 627.41 | -124.7 | -16.6% |

| Capital Funding within other Portfolios | 25.00 | 39.13 | 14.1 | 56.5% |

| Total capital for LG | 777.1 | 666.54 | -110.6 | -14.2% |

COSLA explains that the capital reduction in the Budget “can be attributed to known cessation or reductions of previous funding streams”. Whatever the explanation, it is certainly the case that the local government capital allocation continues to reduce in real terms.

As explained by the Accounts Commission, “borrowing is the main source for funding [local authority] capital projects, and councils are intending to borrow £3.13 billion in 2025-26”. Overall, local government debt currently sits at around £25 billion (see Local Government 2024-25 Provisional Outturn and 2025-26 Budget Estimates) and it seems likely to continue growing over the coming years.

Taxation

A range of taxes are devolved or partially devolved to the Scottish Government. This provides revenues that are available to support the Scottish Budget. There are deductions to the Scottish Budget (known as “block grant adjustments”) to reflect the fact that the Scottish Government now benefits from these revenues and can set the policy to adjust revenues in order to support policy objectives.

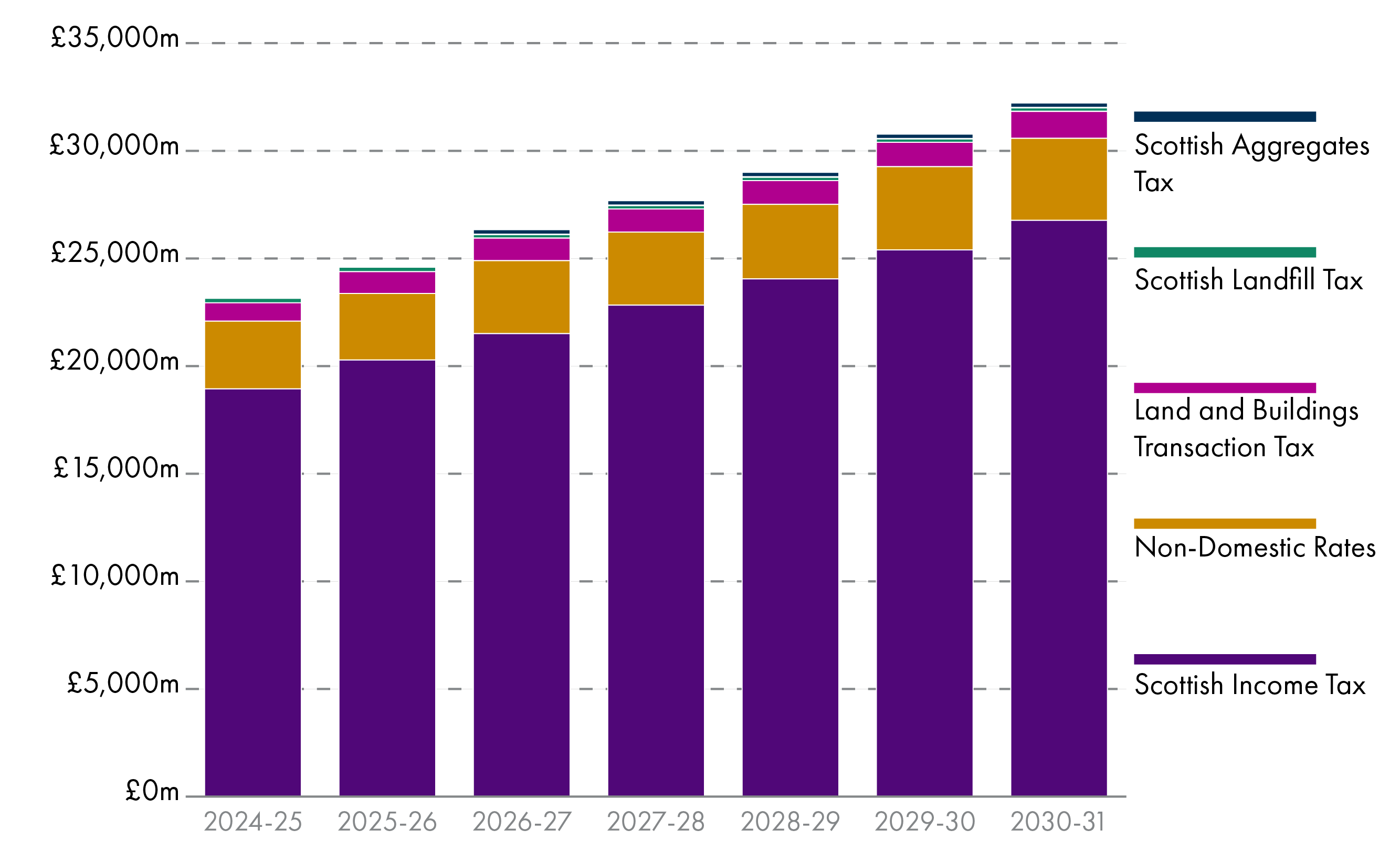

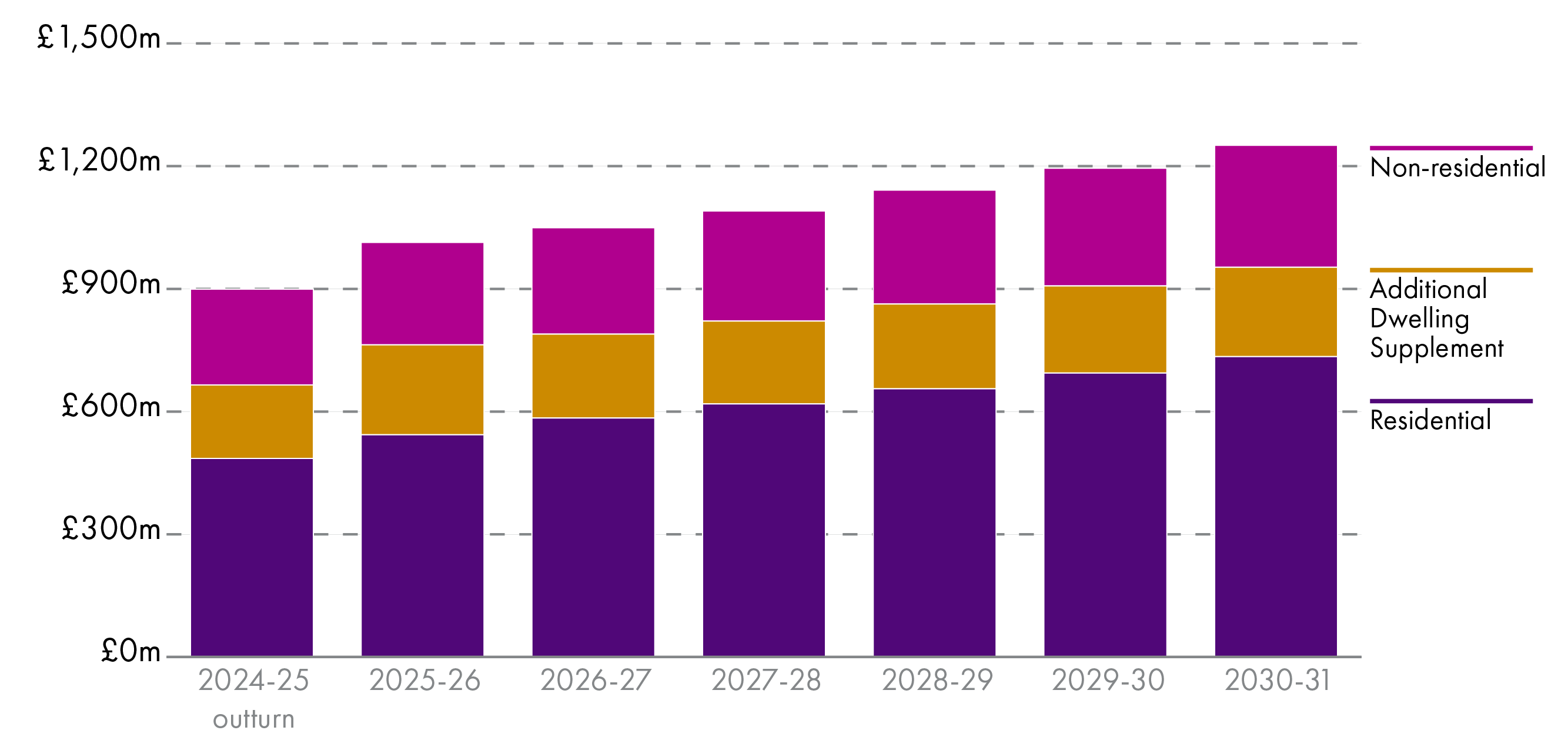

Figure 20 below shows the forecast revenues from the various taxes. Income tax is by far the largest source of revenue for the Scottish Government.

Income tax

Income tax proposals

The Scottish Government set out its proposals for income tax from April 2026 as part of the Scottish Budget 2026-27. These proposals need to be approved by a Scottish Rate Resolution, which must precede Stage 3 of the Budget Bill process. Income tax then cannot be changed during the financial year.

As part of the Tax Strategy published alongside the previous Budget, the Scottish Government had committed to not introducing any new income tax bands or increasing the income tax rates through the remainder of this Parliament.

The proposals set out by the Scottish Government involve:

Increasing the basic rate and intermediate rate thresholds by 7.4%

Freezing the higher, advanced and top rate thresholds

Maintaining existing tax rates for each band.

The result of these proposals is the Scottish income tax schedule shown in Table 7.

| Band | Taxable income | Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Starter rate | £12,571* - £16,537 | 19% |

| Basic rate | £16,538 - £29,526 | 20% |

| Intermediate rate | £29,527 - £43,662 | 21% |

| Higher rate | £43,663 - £75,000 | 42% |

| Advanced rate** | £75,001 - £125,140 | 45% |

| Top rate** | Over £125,140 | 48% |

* Assumes individuals are in receipt of the standard UK personal allowance (£12,570 in 2026-27). The personal allowance is reserved and set by the UK Government.

** Those earning more than £100,000 will see their personal allowance reduced by £1 for every £2 earned over £100,000. This policy is reserved to the UK Government.

Note that Scottish income tax only applies to non-savings non-dividend (NSND) income.

Impact on individuals

The proposed 2026-27 income tax schedule sees a slightly lower tax liability for all income levels compared with 2025-26. This difference is no more than £32 per year, and is lower for those on lower incomes.

When compared with income tax policy in the rest of the UK (rUK), Scottish taxpayers earning less than £33,500 will pay up to £40 less income tax per year than they would in the rest of the UK. The Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) project that the median taxpayer will have NSND income of £31,136, meaning that just over half (55%) of all Scottish income taxpayers will pay less than they would in rUK.

Taxable income above £33,500 attracts a higher tax liability than in rUK and the gap widens rapidly for those earning above the higher rate threshold of £43,663. For example, those earning more than £50,000 will be paying at least £1,500 more income tax per year than they would in the rest of the UK.

| Annual earnings | Scottish Government proposals income tax payable 2026-27 | Difference compared with 2025-26 | Difference compared with rUK |

|---|---|---|---|

| £20,000 | £1,446 | -£11 | -£40 |

| £25,000 | £2,446 | -£11 | -£40 |

| £30,000 | £3,451 | -£32 | -£35 |

| £35,000 | £4,501 | -£32 | £15 |

| £40,000 | £5,551 | -£32 | £65 |

| £45,000 | £6,882 | -£32 | £396 |

| £50,000 | £8,982 | -£32 | £1,496 |

| £55,000 | £11,082 | -£32 | £1,650 |

| £60,000 | £13,182 | -£32 | £1,750 |

| £65,000 | £15,282 | -£32 | £1,850 |

| £70,000 | £17,382 | -£32 | £1,950 |

| £75,000 | £19,482 | -£32 | £2,050 |

| £80,000 | £21,732 | -£32 | £2,300 |

| £85,000 | £23,982 | -£32 | £2,550 |

| £90,000 | £26,232 | -£32 | £2,800 |

| £95,000 | £28,482 | -£32 | £3,050 |

| £100,000 | £30,732 | -£32 | £3,300 |

| £150,000 | £59,634 | -£32 | £5,931 |

Note that Scottish income tax only applies to non-savings non-dividend (NSND) income.

The 2024 Tax Strategy also stated that the Scottish Government would:

Maintain the commitment that over half of Scottish taxpayers will pay less income tax than they do in the rest of the UK – this commitment was met by the 2026-26 proposals on the basis of current estimates and is discussed further below.

Uprate the starter and basic rate bands by at least inflation – this commitment was met, with the uprating of the upper thresholds of these bands by 7.4%. As a result, the starter rate band (the amount between the thresholds) increased by just over 40% and the basic rate band increased by 7,4%. Both of these are well in excess of the current level of inflation, which is just over 3%.

Maintain the Scottish Higher, Advanced and Top rate thresholds at current levels in nominal terms – this commitment was met.

The commitment to ensure most Scottish taxpayers pay less income tax than they would in the rest of the UK

As noted above, the Scottish Government’s Tax Strategy includes a commitment to ensure that over half of Scottish taxpayers will pay less income tax than they do in the rest of the UK. During 2025 there was some debate about whether this commitment was met. This reflected the fact that, at the time of the Budget, this commitment is judged on the basis of forecasts provided by the SFC, which are subject to change as further data becomes available.

In recent years the Scottish Government has allowed a relatively small margin for error. The 2025-26 Scottish Budget suggested that 51% of taxpayers would pay less than they would in the rest of the UK. As such, a relatively small increase in average earnings could result in the commitment no longer being met.

In November 2025, the SFC published an update to their estimates of median income in Scotland. This update suggested that someone earning an income of £30,318 or above would pay more income tax in Scotland than they would elsewhere in the UK. According to the SFC, in 2025-26 this is expected to be 49.1% of Scottish taxpayers, so the commitment was still met for 2025-26 based on this update. However, the same update showed that the statement no longer held for 2023-24 and 2024-25 on the basis of the updated data. Note however that the commitment was made in the 2024 Tax Strategy, subsequent to the budgets for those financial years,. Nonetheless, this shows how finely balanced the commitment is, given that it is based on estimates that will inevitably change when new data becomes available.

In the 2026-27 Budget, the Cabinet Secretary has given herself a little more headroom, by setting income tax in a way which means that 55% of Scottish income taxpayers pay less than they would in the rUK, on the basis of the current estimates.

Income tax revenues

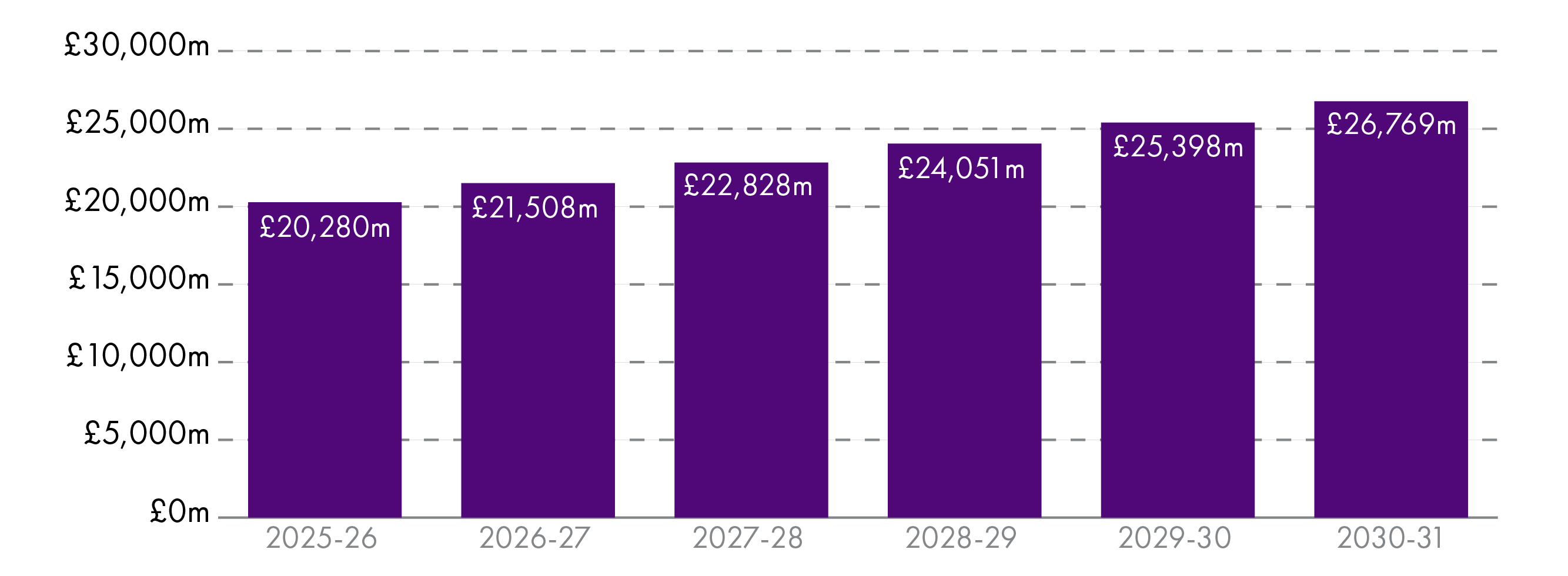

The SFC forecast strong growth in income tax revenues in 2026-27. Forecasted income tax revenues for 2026-27 are £21,508 million, which is £1,228 million (6.1%) higher than in 2025-26, but £274 million (1.3%) lower than the SFC’s December 2024 forecast.

The impact of the increases to the basic and intermediate rate thresholds is a relatively modest reduction (£50 million) in forecast revenues for 2026-27.

Income tax net position

The logic behind the partial devolution of income tax is that the Scottish Budget should benefit from any revenue raised over and above what would have been raised had income tax devolution not occurred.

This means that the amount of revenue added or deducted from the Scottish Budget in relation to income tax depends on two factors: the growth in the size of the tax base (i.e. total earnings) relative to rUK and the policy choices of the Scottish Government relative to the UK Government.

If earnings grow faster in Scotland than in rUK, devolved tax revenues will – other things being equal – be higher than if income tax had not been partially devolved. Likewise, if the Scottish Government increases income tax rates compared with rUK policy, then any additional revenue raised flows to the Scottish Budget.

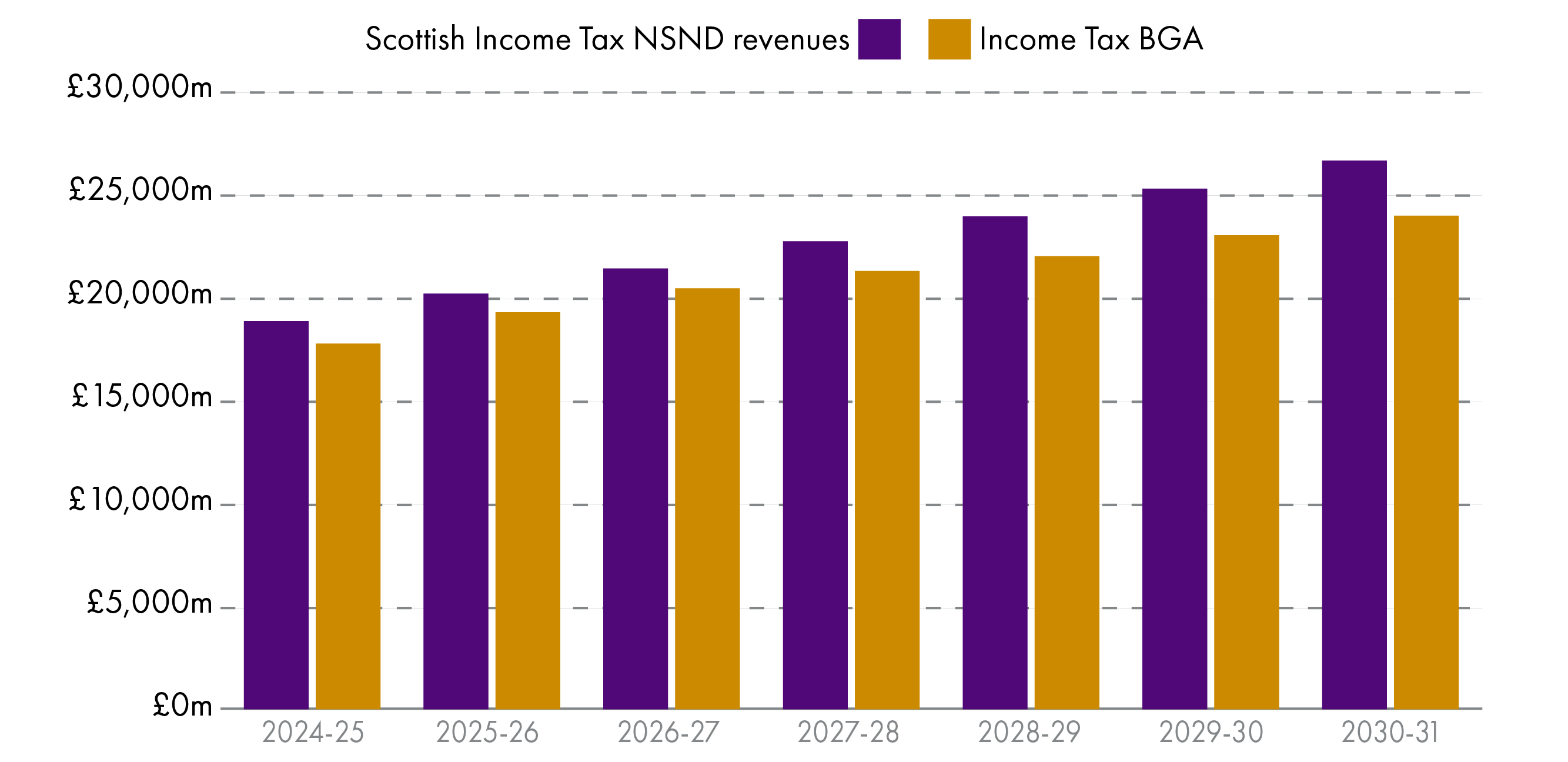

The amount added or deducted from the Scottish Budget through the partial devolution of income tax is known as the ‘income tax net position’. This is the difference between Scottish NSND income tax revenues and the income tax Block Grant Adjustment (BGA). The income tax BGA reflects what Scotland would have raised in income tax had it retained the same tax policy as rUK and if Scotland's per capita tax revenues had grown at the same rate as the rest of the UK.

In 2026-27, the SFC forecasts that the income tax net position will be £969 million. This means that the Scottish Budget benefits by around £1 billion through the partial devolution of income tax.

The SFC had previously forecast that the income tax net position for 2026-27 would be £1,314 million – higher than it is now forecasting. In May 2025, this forecast was revised down again to £1,072 million. According to the SFC, the latest downward revision reflects lower than expected 2023-24 Scottish Income Tax outturn data and the effect of a larger upwards revision to UK average earnings growth in the latest OBR forecasts.

Since income tax was first partially devolved, the Scottish Government has adopted a different income tax policy to the UK Government. This has primarily had the effect of increasing tax rates on earnings above £43,663 relative to rUK. However, over the same time period, earnings have grown more slowly in Scotland than in rUK (although the SFC project that there has been some catchup more recently).

The net result is that, in 2026-27, the SFC estimate that Scottish income taxpayers will pay £1,754 million more in income tax than in rUK due to policy differences, but the Scottish Budget only benefits by £969 million. The SFC describe this as an “tax base performance gap”.

It is also worth cautioning that the income tax net position is highly sensitive to small changes in OBR and SFC forecasts.

Income tax reconciliation

All of this also matters for future budgets. The income tax net position is based on forecasted tax revenues in Scotland and rUK. A reconciliation is then applied to future budgets once actual tax revenues are known. For 2026-27, a positive reconciliation of £406 million is being applied, as the outturn data resulted in a more positive position than had been forecast. In contrast, for 2027-28, a negative reconciliation of -£310 million is currently forecast, although this could change. This is much lower than the £851 million negative reconciliation that had been previously forecast, demonstrating how much these forecast reconciliations can change over time. The Scottish Government does have limited borrowing powers to smooth out the effects of reconciliations if required.

Taxation on income from property

Scottish income tax rates and bands currently apply to non-savings, non-dividend (NSND) income, which includes property income. At the moment, the Scottish Government can only set tax policy to apply to all types of NSND income. It cannot currently differentiate between types of income and – for example – apply a different policy to property income.

In the 2025 UK Autumn Budget, the UK Government announced a 2p increase to the rates of income from property, starting in 2027-28. The UK Chancellor pledged to devolve the relevant powers so that the devolved administrations can determine policy in this area. So, in future, the Scottish Government will also be able to set a different policy for taxation of property income should it choose to do so. The Scottish Budget does not provide any specific commitments on plans to use these new powers in Scotland, stating only that:

The UK Government has committed to devolve an equivalent power, to set a separate rate for property income in Scotland, as part of the UK’s annual Finance Act. Subject to legislative consent from the Scottish Parliament, the first year this power could come into effect would be 2027-28.

Non-domestic rates

Non-domestic rates (NDR) are local taxes paid on land and heritages used for non-domestic purposes in the private, public and third sectors. The tax is administered and collected by local authorities, but tax rates and reliefs are set by the Scottish Government. The amount of tax due depends on the rateable value of the property, set by independent assessors, multiplied by the poundage rates set by the Scottish Government. These are announced in the Budget, alongside a range of rates reliefs.

There has been particular interest in NDR this year as Scotland, like England and Wales, is currently undergoing a revaluation of rateable values. On the Wednesday before the Budget, the Scottish Parliament held a debate on non-domestic rates and the impact of increased bills on businesses and other non-domestic properties across Scotland. This came after draft valuation notices were sent to properties at the end of November showing changes to their rateable values. It is clear that the revaluation is causing considerable concern across several sectors, particularly amongst hospitality and retail businesses.

In last year’s Budget, the Scottish Government maintained the poundage rates from 2024-25 at 49.8 pence for the Basic Property Rate and increased the Intermediate and Higher Property Rates in line with inflation. The 2026-27 Budget includes measures aimed at softening some of the impacts of the 2026 revaluation, with the Government reducing the Basic Property Rate (for properties with a rateable value up to and including £51,000) from 49.8p to 48.1p. Reductions will also be seen for the Intermediate and Higher Property Rates.

The Budget states:

The Scottish Budget delivers a broadly revenue-neutral revaluation in real terms over the course of the revaluation cycle, and therefore decreases the Basic, Intermediate and Higher Property Rates in 2026-27 to reflect overall growth in rateable values at revaluation, whilst offering a generous relief package.

Retail, Hospitality and Leisure relief

The Parliamentary debate held the week before the Budget had a particular focus on the retail, hospitality and leisure (RHL) sectors. Some businesses in these sectors are likely to see significant increases in their rateable values come April.

Based on draft 2026 rateable values, the Government estimates that 144,000 non-domestic properties across Scotland (around 56% of total non-domestic properties) will see an increase in their rateable value in 2026. Approximately 66% of hotels, 60% of pubs, 49% of shops and 88% of leisure and entertainment properties will see their rateable values increase. Self-catering properties are expected to see an overall increase in rateable value of 88%, with the mean rateable value of self-catering entries rising from £4,153 to £7,826. However, changes to actual NDR bills for individual properties will depend upon the rates and reliefs set out in the Budget. These include the Small Business Bonus Scheme which provides 100% exemptions to properties with rateable values less than £12,000 (subject to cumulative rateable value rules).

The Budget includes a new 15% NDR relief from April 2026 to March 2029 for RHL premises liable for either the Basic or Intermediate Property Rates. This could help up to 37,000 properties (subject to the cap of £110,000 per ratepayer) and the Scottish Budget states this will reduce the NDR bills of beneficiaries by around £36 million in 2026-27. The Budget also extends and expands the 100% relief for three more years for RHL properties on islands and some remote areas (capped at £110,000 per business per year). The SFC estimates that these policy decisions will cost around £47 million.

How these reliefs compare to those announced by the UK Government (for NDR payers in England) at the Autumn Budget Statement will undoubtedly be explored over the coming weeks. Initial analysis by the IFS suggests that the 15% RHL relief “will be a little more generous than the equivalent lower tax rate in England for small businesses, but less generous for larger businesses occupying multiple properties due to the cap”. It’s also interesting to note that the Scottish Government could improve the support available depending on possible announcements by the UK Government:

We are still awaiting details from the UK Government about possible changes to business rates for pubs in England, following press speculation last week. But I can assure members that, if additional resources become available, we stand ready to use these to provide even further support for the sector in Scotland.

Revaluation-related transitional reliefs