SPICe Style and Writing Guide (Updated 2025)

Our job is to write briefings for MSPs that are clear, accurate, concise, accessible, impartial and relevant. This guide provides guidelines on our writing style, on using plain language and on using our templates.

Writers' checklist

Before you start to write

Consider who will read your writing and what they need.

Be sure you can meet deadlines.

What you need to consider as you’re writing

Make sure your briefing is accessible, accurate, impartial, relevant and brief. This includes giving appropriate consideration to equality issues, human rights, the principles of sustainability and the impact of proposals on the climate and nature.

Aim for an average sentence length of 15-20 words.

Use more active than passive verbs.

Identify and free hidden verbs.

Avoid using jargon and obscure business terms where possible.

Have the confidence to use everyday words and expressions.

Help your readers navigate your briefing with a strong summary and descriptive headings and sub-headings.

Use the tips in this guide to write online content.

Check grammar and do final proofing checks.

Use our templates

Follow our guidelines for checking calculations

Before you publish, check the following:

Have you included a short introduction to the briefing on the cover page?

Have you provided a short executive or key point summary that your readers can use as a stand-alone briefing?

Is your briefing impartial, relevant, accurate, clear and on time?

Have you used parliamentary terminology properly?

Have you completed the SPICe disclaimer on the back page?

Is there a contents page? Always include one unless your briefing is very short, for example, under six pages long.

Have you used infographics, tables, photographs, maps and other visual images appropriately to help your reader understand the subject?

Has your briefing been proof-checked for sense, accessibility, spelling and grammar?

If time allows, has your briefing been peer reviewed by one or more external experts in the subject area?

Before you start writing

Before you get started, take some time to plan what you’re going to write and how you’re going to meet your deadline. This section covers:

Who are you writing for and what do they need?

Our job is to produce briefings for MSPs, their staff and Parliament staff to help them with their parliamentary work. This could cover, for example, legislative proposals, a committee inquiry or a debate.

So put yourself in their place and ask yourself what information you’d need to understand the subject or question.

Write down some headings or key points that you want the briefing to cover and put these in a logical order.

Identify the main sources you’ll use. Think about, and gather, the basic references you’ll need.

Search parliamentary questions and answers and votes and motions, as well as internal SPICe resources such as the SPICe catalogue and Assyst.

How to manage deadlines

We need to produce our briefings to whatever deadline is agreed and is appropriate to their purpose.

There’s no benefit, for example, in publishing a briefing for a plenary debate after the debate takes place. There’s also limited benefit in producing a briefing shortly before a debate starts.

We normally agree when we’ll publish briefings with the relevant committee clerk. As a general rule, we aim to publish briefings by the following deadlines:

Bill briefing (Government bill): five working days before the first Stage 1 evidence session or by negotiation with the committee clerks if Stage 1 begins fewer than 10 working days after introduction.

Bill briefing (member's bill): liaise with the Non-Government Bills Unit (NGBU) but remember not all members' bills come through NGBU. If this is the case, treat it as a Government bill.

Bill briefing (committee bill): by negotiation with committee clerks and NGBU.

Bill briefing before Stage 3: five working days before the Stage 3 plenary debate.

Committee briefing (informal papers): by negotiation with the committee clerk.

Petition briefing: by the date the Public Petitions Committee clerks request.

Plenary debate: at least two working days before the debate.

It’s important that you meet the deadline that you’ve been given. Should you anticipate any problems meeting a deadline, discuss this with your line manager as soon as possible.

Work back from your final deadline to decide how much time you can spend on a briefing. Allow time for people to get back to you with their comments or views. Remember that your priority is not necessarily theirs. Build in enough time for them to respond.

Proof readers and peer reviewers can only review the briefing you give them. They’re not responsible for rewriting your work.

How to increase the impact of your briefing

This checklist has been developed by SPICe Office Heads to aid researchers when thinking about maximising the impact of SPICe briefings for our core customers. These are MSPs, MSP staff and Parliament staff.

All briefings are different, and there is no one-size-fits-all approach to promoting them. So, this list is not intended to be prescriptive. Instead, it presents a list of issues for you to consider, and discuss with your line manager, when preparing briefings.

Choice of topic - While a number of SPICe briefings are mandatory (bill, budget briefings etc.), there is scope for SPICe researchers to publish briefings on any topic within their remits. The first thing to consider is whether the topics chosen are those of most interest and relevance to our core customers.

Style, structure and executive summaries – This guide contains a range of advice on how to write with impact. Researchers should consider at the outset how style, structure and the executive summary could be enhanced to make briefings more accessible and impactful for our core customers.

Infographics – Graphs, charts and other infographics are an obvious way in which the accessibility and impact of briefings can be improved. Researchers can seek advice from the Data Visualisation Team on any aspect of data visualisation. This should be done as early as possible, ideally in the initial planning stages of the briefing.

Media – The media regularly pick up on SPICe briefings, particularly those which provide analysis of government budgets or high profile policy areas. SPICe has an agreement with the Parliament Communications Office (available on the SPICe Sharepoint site) which shows how that office can be used to promote particularly high profile briefings. Again, you should get in touch with the Parliament Communications Office to discuss an approach as early as possible.

Social media – As well as media promotion work, researchers can also use the Parliament’s social media accounts to promote briefings. Your team leader will be able to direct you to the relevant SPICe staff working on SPICe social media . Depending on the subject matter and expected interest, it may also be appropriate to promote briefings from a committee account, the Parliament's main account, or both.

What you need to consider as you're writing

It’s important for us to produce briefings that are:

Our briefings should also take account of equality issues, human rights, the principles of sustainable development and the impact of proposals on the climate and nature.

Make your briefing accessible

Our briefings should be as accessible as possible to disabled people.

The Equality Act 2010 requires organisations to ensure that disabled people do not have difficulty accessing services; this includes web content. We must therefore make web pages and documents accessible to as many people as possible.

Here’s a definition of accessibility:

Accessibility enables individuals with disabilities – such as people with blindness, low vision, or mobility impairments – to read, hear, and interact with computer-based information and content with or without the aid of assistive technology. A document is considered accessible if its contents can be accessed by anyone, not just by people who can see well and use a mouse.

Adobe Systems 2005

The General formatting guidance and How to use our templates sections include advice to help you meet accessibility requirements.

Make sure your briefing is accurate

Your briefing paper must always be accurate and as up-to-date as possible. Double check your information, particularly statistical information.

Our customers operate in public forums so any out-of-date or inaccurate information will be quickly picked up.

Always check that you’re using the latest information or data.

Don’t always rely on a website to give you the most up-to-date data.

Check when new information or data will become available and, if it’s relevant, let your readers know.

Cross-check your information – especially key information – with other sources if you can.

Check your statistical calculations are accurate

Make sure that any statistics in your briefing are accurate and that you’ve checked them thoroughly.

If you’re in any doubt, get advice from one of the SPICe Office Heads or a member of the Financial Scrutiny Unit (FSU).

See the Guidance for calculations section for further information on checking your calculations.

Be clear and understandable

Use plain language to make your writing clear and understandable. The Plain language writing techniques and tips section has more information.

Be impartial

All our briefings must be impartial and balanced; this is crucial to maintain the position of neutrality required of all Scottish Parliament staff.

Our job is to present information to MSPs to help them make decisions – not to decide issues for them. This doesn’t mean our briefings need be bland or uninteresting, or that you should give every argument or viewpoint the same weight.

Always take a balanced approach to writing and give both sides of the argument. Sometimes the evidence will point firmly in one direction and you should reflect this in your briefing.

Give full references for any supporting evidence you cite and attribute any quotes.

Avoid, in all cases, bias, prejudice and your personal opinion. Bias or prejudice can come in subtle forms. Examples include supporting one side of an argument over another by being selective with your evidence, or by the weight or quality of the evidence you’re presenting.

Make your writing relevant and brief

We want our briefings to be relevant, brief and clear. If you're not knowledgeable in a subject area, check as many sources as possible to find out what the main issues are.

It’s usually easier to write long papers than short and succinct ones. This is particularly true if you have limited knowledge of a subject and you’re not sure what’s important and what you can leave out.

You’ll only become familiar with a subject once you’ve worked on it and built up your knowledge. Don’t be afraid to admit that you don’t know everything about an issue or subject. You’ll be surprised how people are willing to share their knowledge on a subject when asked by an interested novice! You can also do the following:

Check what questions MSPs have been asking on the topic and if there have been any previous relevant debates in the Parliament.

Ask an expert what they think the main issues are.

Think about whether the information you intend to put in your briefing is relevant and will help MSPs understand the issues.

Keep your briefing as short as possible. Don’t just write all you know, or have found out, about a subject.

Consider equality issues

You must always consider what, if any, equality issues arise in the area of the subject matter you’re writing about, and whether you need to highlight these.

The Parliament has a commitment to equity, diversity and inclusion. It also has a People Services, Diversity and Inclusion team to further develop these policies.

If you’re not sure whether you need to highlight an equality issue, ask:

one of our Office Heads

our researcher with responsibility for equality issues, or

a staff member with corporate responsibility for diversity and inclusion.

If you’re working on a bill briefing, check the following for any mention of equality issues in relation to the bill:

the bill’s accompanying documents, especially the Policy Memorandum if it’s a Government Bill

an equality impact assessment, which are published for most bills and other significant policy developments

a summary of consultation responses on the bill or related policy developments, or relevant individual consultation responses.

Write your briefing in an inclusive and accessible way, in line with the guidance in this guide. You must make sure you’ve not written anything that could be interpreted as discriminatory in relation to any social or racial groups.

Consider human rights

You must always consider whether there are potential issues relating to human rights when you’re preparing a briefing. Human rights come from a range of sources. However, two conventions currently have particular importance to the legal framework in Scotland.

The European Convention on Human Rights

The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR or 'the Convention') is the key statement of human rights in relation to the work of the Scottish Parliament. ECHR rights are used to define the legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament.

The ECHR is a treaty of the Council of Europe. The UK Government signed the treaty in November 1950. It became possible for the UK courts to apply its principles when deciding cases in October 2000, when the Human Rights Act 1998 came into force.

The importance of ECHR to the Scottish Parliament predates the Human Rights Act. Section 29(2)(d) of the Scotland Act 1998 states that an Act of the Scottish Parliament is not law if it

…is incompatible with any of the Convention rights ....

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (Incorporation) (Scotland) Act 2024

The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) includes rights such as the right to an education and the best achievable standard of health. The 2024 Act incorporated into the law of Scotland the rights contained in the UNCRC which are within legislative competence. It did not incorporate rights or articles that would fall under matters reserved to the UK Parliament.

Public bodies must respect those rights which are incorporated by the 2024 Act.

Further advice on human rights issues

All Scottish Government bills come with statements on human rights. These are found at the end of the Policy Memorandum accompanying the Bill. They can, however, be quite brief.

You can ask for advice on the implications of human rights for your briefing from relevant SPICe researchers (usually covered by civil justice and equality issues researchers). The Office of the Solicitor to the Scottish Parliament (the Legal Office) may be another source of advice. This office advises the Presiding Officer on:

the legislative competence of all bills, including compatibility with ECHR rights

the Parliament’s powers and procedures, including devolved and reserved powers.

Consider the principles of sustainable development

Sustainable development scrutiny

The Scottish Parliament has been working towards using sustainable development as a lens for parliamentary scrutiny. A sustainable development lens can be applied to all scrutiny – whether that is through a committee inquiry, legislative and post-legislative scrutiny or budget scrutiny.

A Sustainable Development Impact Assessment (SDIA) Tool has been developed for use in the Scottish Parliament . The aim is to support more holistic consideration of public policy, draft legislation and budget proposals. This is intended to enable a more consistent approach to policy development.

The SDIA tool covers consideration of other topics that the Parliament has made commitments to build into standard scrutiny processes. These include climate change, equality issues, human rights and participation. This enables them all to be considered together, in a joined-up way.

Legislation and the Parliament's rules set requirements for sustainable development scrutiny

Under the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009, all Scottish public bodies (including the Parliament) have a statutory duty to exercise its functions “in a way that it considers is most sustainable”.

The Parliament’s Standing Orders (Rule 9.3.3(d)) require Government and Members’ bills to be accompanied by a Policy Memorandum which includes assessment of the effects of the bill on sustainable development. The Standing Orders (Rule 9.6.3) also require the lead committee to consider and report on the Policy Memorandum for Government bills.

Further information on sustainable development issues

For more detailed guidance, please see the clerking manual lenses and toolkits, or ask the Head of Research and Sustainable Development Scrutiny in SPICe.

Consider the impact of proposals on the climate and nature

In tandem with sustainable development scrutiny, the Scottish Parliament has been working towards embedding climate and nature considerations across parliamentary scrutiny. A climate and nature lens can be applied to all parliamentary work – whether that is through a committee inquiry, legislative and post-legislative scrutiny, budget scrutiny or debates. It can be applied to work where the main consideration relates to climate change or nature, as well as being used as a lens to scrutinise other issues.

Climate and nature goals are connected with other sustainable development goals and can be considered as a part of broader scrutiny lenses, for example sustainable development.

Further information on climate and nature scrutiny

For more detailed guidance, please see the clerking manual lenses and toolkits, or ask the Head of Research and Sustainable Development Scrutiny in SPICe.

Plain language writing techniques and tips

Be clear about your readers and the appropriate tone

Before you write, think about who you're writing for. As you write, try to use the words and phrases you’d use if they were in the room with you and you were talking to them.

If your readers range widely, for example from MSPs and officials to members of the public, think of someone you know quite well but whom you also respect. An example could be someone in your family. Write using the words and phrases you’d use if you were describing the subject matter to them.

Doing this will help you avoid one of the main pitfalls in business writing: an inflated tone. This tends to produce writing that’s dry, impersonal and harder to read than it needs to be.

Remember that when you talk to someone you instantly alter the tone of how you speak to match your perception of that individual. This, in turn, influences the words and phrases you use.

Harnessing this skill in your writing is a powerful communication technique. It should make writing easier and is a courtesy to your readers.

Aim for an average sentence length of 15-20 words

Effective writing is clear and accurate at first reading. An average sentence length of 15-20 words will contribute towards this.

Remember this is an average. A longer, well structured sentence of 30-35 words shouldn’t cause readers any problem. But they should be the exception.

Similarly, you can often use a short sentence to emphasise a point, like the short sentences that start and end the preceding paragraph.

If the number of words in a sentence strays into the mid-30s or higher, rewrite it. The longer the sentence, the more likely readers will simply skip it.

How to check average sentence length

The most effective way is to check as you write, or after every section you write. And the fastest way of doing this is checking visually.

In an A4 Word file using Arial 12 point, two lines of text will have a word count in the high 20s or low 30s. So a series of sentences of this length will indicate a slightly high average sentence length. And sentences running over more than two lines are worth checking individually.

A more thorough check is to:

count the number of sentences in a passage of text

highlight the passage and note the total number of words

divide the number of words by the number of sentences.

Using Microsoft Word to check sentence length

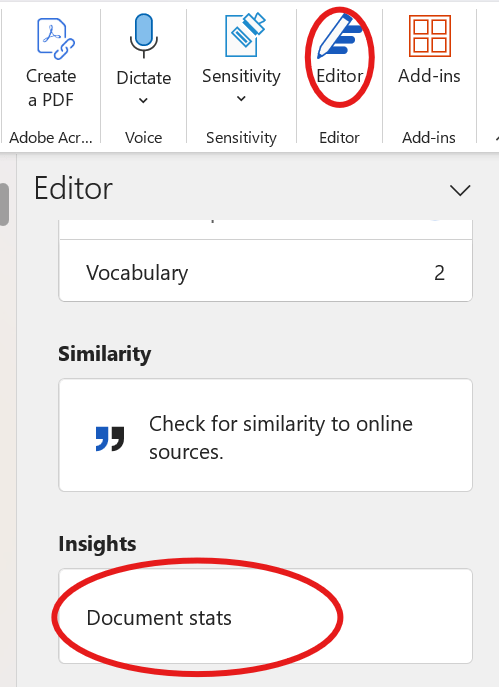

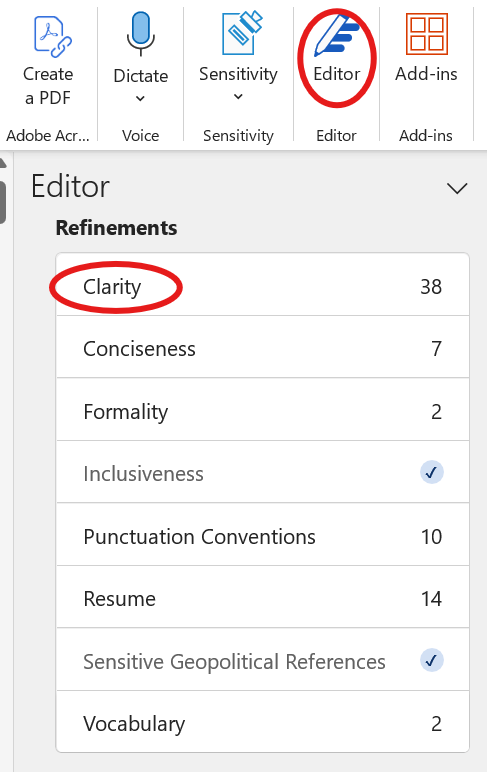

When writing in Microsoft Word, you can use Editor (right end of ribbon on 'Home' tab) to to check sentence length. This is one of the pieces of information you'll get if you click on 'Document stats'. For longer documents, this can take some time.

Dealing with long sentences

Your options are to:

split the sentence into two or more sentences, or

use a bulleted list.

If you choose a bulleted list, follow the style described in the Style Guidelines section.

Use more active than passive verbs

Passive writing is one of the reasons that a lot of business writing is impersonal and seems uninteresting to read. It also contributes towards an inflated tone of writing.

When you talk, you use many more active than passive verbs. You also use passive verbs carefully and precisely. Doing the same in your writing injects life and clarity.

The guidance here will help you identify passive verbs and only use them appropriately.

What do active and passive verbs look like?

Active verbs

When people talk they very often follow this word order:

Someone or something - does - something

For example:

| MSPs | approved | the budget |

| Councils | are introducing | new policies |

| Auditors | will scrutinise | the results |

These use active verbs. This is about who’s doing an action, not about tense; the examples above use the past, present and future tenses respectively.

Passive verbs and problems they can pose

When writing, people often invert the word order they’d use when speaking, making the verbs passive. For example:

| The changes | were approved | by MSPs |

| New policies | are being introduced | by councils |

| The results | will be scrutinised | by auditors |

One obvious consequence is that readers must reach the end of the passive sentence to find out who’s doing what. So the longer the sentence, the more you’re demanding of the reader.

Writers sometimes assume the subject (the person or thing doing the action) is clear from the context and omit it altogether. For example:

| The changes | were approved |

| New policies | are being introduced |

| The results | will be scrutinised |

The risk is that you lose clarity because the reader is unable to identify the subject.

There’s a more complex risk when passive sentences like this have more than one subject. The following passage is from a council’s guidance to an individual who wants to open a catering outlet. It shows passive verbs in bold.

A completed Public Notice must be displayed at or near the premises. Form B must be completed and returned to the licensing section. A licence will be issued if everything is in order.

This passage forces the reader to work out that they are the subject of the first three passive verbs (‘displayed’, ‘completed’ and ‘returned’), while the council is the subject of the fourth.

By avoiding naming any subjects, the passage is impersonal and its tone is more elevated than it needs to be. After all, it’s meant to be a simple, practical instruction, not part of an academic treatise.

How to identify a passive verb

Grammatically, the structure of a passive verb is:

part of the verb ‘to be’, plus

another verb, plus (sometimes)

‘by’.

The following example has each of these elements:

The Bill will be introduced by the Scottish Government in April.

The following example doesn’t specify a subject, so omits ‘by’:

The procedure was phased in after a consultation period.

How to use Microsoft Word to help identify passive verbs

You can use the Editor facility in Microsoft Word to help identify passive verbs using its prompts for 'clarity'. It can also provide a range of other prompts to help you write in plain language.

Note that this function is not currently available in Fonto. However, you can cut and paste Fonto text into Microsoft Word as a check for passive verbs (or to provide a word count).

When it's OK to use passive verbs

When you speak you use passives rarely but precisely, normally for one of three reasons (or a combination of them), as follows:

1. To avoid blame or soften the tone:

Example: One section of the form has not been completed correctly.

If you were speaking to someone you’d asked to fill in the form you’d probably use a passive because the active would be too blunt: ‘You didn’t fill in the form correctly’.

2. Because the subject is irrelevant, unknown or neutral:

Example 1: The polluter-pays principle was established in 1975.

Example 2: Since then it has been adopted in many countries.

3. To stress one element of the sentence over another:

Example 1: Five recommendations have been made by the Justice Committee.

Example 2: The Justice Committee has made five recommendations.

Although these seem similar, there’s a subtle difference. In example 1 above the important information is the number of recommendations that the Justice Committee has made.

But, in example 2, the important information is that it’s the Justice Committee– as opposed to other committees in the Parliament – which has made recommendations.

How to avoid writing passively

Avoid writing passively by following these tips.

Tip 1: Look at who (or what) is doing the action. If it’s at or towards the end of the sentence, move it to the start.

Passive: The policy was reviewed by an all-party committee.

Active: An all-party committee reviewed the policy.

Tip 2: If the subject isn’t clear, can you identify one and put it at the start?

The example is from an auditor’s report on a health board.

Passive: The report identifies where improvements are needed and whether value for money is being achieved.

Active: The report identifies where the board needs to improve and whether it is achieving value for money.

Tip 3: Can you use ‘we’ (and, perhaps, ‘you’)?

The example below is from a (fictional) briefing:

Passive: In this briefing, recent developments in this field across Europe are analysed. A full list of sources can be found at the end of the document.

Active: In this briefing, we have analysed recent developments in this field across Europe. You can find a full list of sources at the end of the document.

Identify and liberate hidden verbs

Hidden verbs inflate the tone of your writing. These tips will help you identify and re-write sentences containing hidden verbs.

What is a hidden verb?

A verb becomes ‘hidden’ when it starts off as a verb but the writer changes it into a noun. For example:

MSPs considered the alternatives.

MSPs gave consideration to the alternatives.

By changing the verb ‘considered’ into the noun ‘consideration’, the writer has to think of and insert a new verb, in this case ‘gave’.

Why hidden verbs matter

Hidden verbs contribute to over-writing. They also contribute significantly to inflating the tone of writing.

They often start out as a simple idea that a writer obscures with padding. Hidden verbs don’t impress readers: they’re more likely to annoy them and to encourage them to skip sentences.

How to identify a hidden verb

This section contains tips on how to identify and deal with hidden verbs.

How to find hidden verbs

Sometimes you’ll notice a pattern, namely: ‘the’ + noun + ‘of’. For example:

Noun: The upgrade involves the introduction of new software.

Verb: The upgrade involves introducing new software.

But often it’s about setting aside editing time, by:

drafting as you normally do

putting away your draft, preferably overnight

spending time specifically looking for ways to edit your writing to make it more concise.

With practice, you’ll quickly see ways to shorten your writing without changing the meaning. Use the following examples to help you:

| We made a decision about what to do next.We decided what to do next. |

| These proposals could have a substantial effect on communities.These proposals could substantially affect communities. |

| MSPs gave their approval to the proposals.MSPs approved the proposals. |

| Options for service provision include the use of arm’s-length external organisations.Options for providing services include using arm’s-length external organisations. |

| Public sector organisations make a significant contribution to the islands’ economy.Public sector organisations contribute significantly to the islands’ economy. |

Editing to improve the overall tone of your writing

It’s often worth doing a mechanical edit – that is, freeing the hidden verb – and thinking of ways to express the idea more clearly. This often ties in very effectively with using everyday words and phrases. For example:

1. Researchers verified this through consideration of local partnership performance.

2. Researchers verified this by considering how local partnerships were performing.

3. Researchers verified this by considering how well local partnerships were working.

and:

1. Owing to the absence of sufficient data, it was not possible to make a robust assessment of this indicator.

2. The absence of sufficient data meant we were not able to assess this indicator robustly.

3. We did not have enough data to thoroughly assess this indicator.

Avoid 'noun-noun-noun' constructions

A sentence which has several nouns in a row can be difficult to read and understand. Being concise doesn’t always mean being clear. Readers respond better to nouns that are clearly linked to verbs than they do to sentences containing nouns in a row. For example, compare these sentences:

An effective performance management system drives service improvement.

Good performance management helps us to improve our services.

The following grid shows how easy it is to assemble nouns. But each combination forces readers to stop, work out how the words link to each other, and reassemble the idea in their heads before reading on.

But they’re more likely just to skip to the next sentence.

| project | sponsorship | eligibility |

| performance | management | system |

| sustainability | improvement | initiative |

| rehabilitation | appraisal | framework |

| budget | implementation | arrangement |

| strategy | oversight | board |

Deal with jargon and business terms

Jargon can confuse readers. Consider how best to deal with such terms and whether you need to use them at all.

What is jargon?

In your work, you’ll have to deal with several kinds of jargon. Your job is that of a gatekeeper. That is, you must pass on only terms you’re confident your intended readers will understand in the way you intend.

If you’re not confident they will, you need to explain the term. This will often involve giving examples. Or you may not have to use the term at all.

Your work will inevitably expose you to the following:

| Type of jargon | Example |

|---|---|

| Professional terms | benthic species (fisheries)quartile (statistics)accrued entitlement (pensions) |

| Business jargon | workstream, scaleable, cutting edgecapacity, capability, corporate values |

| Political terms | co-production, bipartisanagenda (for example, ‘the green agenda’) |

Identify and deal with professional jargon

There are three ways to deal with professional terms:

You’re confident your readers are expert in the area you’re writing about, so you can use the professional terms freely.

You’re confident some readers will know the terms, but others may not. So you use the term but explain it, or give examples to illustrate it.

You can write the content perfectly clearly without using the professional term at all.

For example, you’re writing about heart disease and need to use the term ‘people suffering from cardiomegaly’, a term that describes an enlarged heart that may be associated with heart failure.

You’re confident your readers are expert in this area. Use the term with no explanation.

You’re confident some readers are expert in this area, but some may not be. You write something like: ‘…and people suffering from cardiomegaly, which describes an enlarged heart and may be associated with heart failure.’

You’re writing to a very general audience who are unlikely to know the term. You might write: ‘…and people suffering from an enlarged heart, which may be associated with heart failure.’

Define at point of writing, in footnotes or in a glossary

The most reader-friendly way to define professional jargon is at point of writing. If you divert the reader to a footnote or glossary you’re forcing them to:

stop reading the point you’re making

go to the bottom of the page or find the term in the glossary

absorb the definition

go back to the point they left and re-read it.

However, you may still need a glossary if the subject matter is specialised and specialist terms occur frequently. A useful alternative is to identify and define specialist terms at the start of a piece of writing. This prepares and briefs readers from the start.

Be harsher with business and political jargon

In an ideal world you could simply dispense with all business jargon and political terms. But realistically you must judge each term against these criteria:

Is the reader likely to understand the term?

Is the reader likely to understand the term in the way you intend?

If the answer to either is ‘no’, you must do something about it.

For example, the term ‘workstream’ appears frequently in business writing but doesn’t feature in some dictionaries at all. So it’s almost bound to baffle some readers. If you feel you must use a term like this, it’s worth giving examples to illustrate it.

Be as specific and clear as you can

Other terms demand more of you because people use them with deliberate vagueness. For example:

capacity (might mean numbers, might mean skills)

engage with (might mean consult, listen to, heed, get involved or simply talk to)

governance (can refer to many aspects of managing an organisation or project)

resources (could mean people, money, land, property, and much more)

support (has a huge array of possible meanings).

Be as specific as you can. Left alone, terms like these leave readers to guess, with the obvious risk that they’ll guess incorrectly and at best misunderstand what you write.

Be wary of fashionable phrases

Some terms drift into business writing and enjoy brief periods in vogue. For example:

deliver (delivering priorities, delivering programmes)

drive, driver, driving (driving change, key implementation driver)

going forward

reach out, reaching out (initiating contact? responding? helping?)

robust (reliable? effective? thorough?)

touch base, touching base (getting in touch? meeting?)

Some risk being unclear. The wider your readership, the less likely they are to be familiar with concepts like ‘driving the pace of service integration’ or ‘strategic driver for the delivery of reform’. You may have one set of things in mind for ‘a robust investigation’ but a reader may not share your interpretation of the elements you consider ‘robust’ to be composed of.

Some are silly. Some writers, and speakers, tack ‘going forward’ on to sentences to indicate future action. But that’s what the future tense is for.

Have the confidence to use everyday words and expressions

Using everyday words helps to ensure that your writing is clear and that you set the right tone to engage with your reader. This section looks at the problem with over-writing. We recommend choosing words you'd use if you were talking to your reader. We also advise carefully considering the use of :

The problem with over-writing

Professional writing requires you to make sure your readers have access to complex ideas, often involving specialist vocabulary and concepts.

You can be confident your readers will readily understand everyday words and expressions. Yet many writers set these aside and use a different set of terms, which can make writing seem inflated or pompous.

Having the confidence to use everyday words and expressions is about achieving the tone that’s appropriate to your readers.

You do this every day when you speak. Try to apply the same skill to your writing. Think who will read your writing and use terms that you’d use if you were speaking to them.

This should help you achieve a tone that’s respectful and neither too formal nor too informal.

Some writers feel they must discard plain language in favour of more elaborate alternatives, often involving:

words more common in written English, less common in speech

abstract terms

euphemisms

rarefied terms

fashionable business jargon.

This is often a sign of lack of confidence, or fear of what others might think of them if they use more familiar terms.

In professional writing, readers want information which is clear, accurate and that they can understand at first reading.

Choose words which you'd use if you were talking to your reader

When we speak we sometimes choose one set of words, but we choose another set when we write. One of the most effective and one of the easiest plain language techniques is to use the former in writing.

| Terms we tend to write: | Terms we tend to say |

|---|---|

| accomplish | do, complete, finish |

| address | consider, take action, resolve |

| advise | give advice; tell, inform |

| ascertain | find out |

| commence | start, begin |

| consult | ask |

| determine | decide |

| discontinue | stop, end |

| endeavour | try |

| facilitate | make easier |

| purchase | buy |

| representation | comment |

| terminate | end |

| utilise | use |

Using 'about'

Some writers go to some lengths to avoid writing ‘about’. They’ll use ‘with regard to’, ‘as regards’, ‘in relation to’ and other alternatives. The impact is that sentences look stilted. If ‘about’ is the right word, use it.

Abstractions may force readers to interpret

You must decide if your readers will reasonably understand abstract terms. Taken out of context, the highlighted abstract terms in the following passage are almost impossible to understand.

The selected delivery model targets individuals who are in need of a high degree of support and a range of interventions to promote social inclusion and avert the risk of financial exclusion

Readers should never be forced to interpret, so the passage would need to be rewritten to make it clear and accurate.

Euphemisms soften the tone but may erode impact or be inappropriate

If you’re writing about violence caused by people drinking too much alcohol, it would be more accurate to call it a problem that needs solved rather than an issue, or challenge to be addressed.

Euphemisms may also be inappropriate. A report that refers to an industrial accident as an ‘adverse incident’ risks insulting friends or relatives of someone involved in this or a similar accident.

Avoid inflating ideas

If you’re writing about how people were selected to take part in a medical trial you might write plainly:

Doctors assessed each patient to decide if they were suitable to take part in the trial.

It’s easy to inflate this to something like:

An assessment of each patient was undertaken by clinicians to determine their suitability to participate in the trial.

The second version uses:

a hidden verb (‘assessment’)

a passive (‘was undertaken’)

medical jargon (‘clinicians’)

the inflated ideas of ‘determine’ and ‘participate’.

These will combine to make it more difficult, and certainly more boring, to read.

Prefer English when writing in English

Business writing often features phrases borrowed directly from Latin or other languages; for example:

as per

ultra vires

locus

ad hoc

in situ

per se

in lieu of.

Be cautious with these. Some may be necessary in some contexts. Others may not. If possible, use English alternatives. You can generally be confident your readers will be much more familiar with English than with Latin.

Will figures of speech work?

We can’t avoid figures of speech. They add colour and character to writing. But ask yourself if your readers will reasonably understand them in the way you intend.

The following examples suggest partial ideas, but leave gaps that readers have to fill in:

Example 1: The authority should be able to show it is moving in a positive direction.

Can a direction be positive?

How can the authority show this?

Example 2: Partnership working provides opportunities for organisations to think more strategically.

Can organisations think?

What does ‘think strategically’ actually mean?

Tips for helping readers navigate

Think how you can help your reader get to the information they need. The suggestions below may help.

Summaries answer readers’ initial questions

When anyone receives written information to read, they’ll want answers to questions like these:

What’s this about?

Why should I read it?

What’s changed, important or new about this information?

A good summary will answer these questions. They work well in many writing formats, including emails, reports and briefings. Use the following interrogatives to help you summarise information:

| Interrogative | For example |

|---|---|

| Who | Who needs to read this? Who is affected? |

| What | What’s it about? What new information does it contain? |

| Where | What areas – literal or figurative – does it apply to? |

| When | Are there any relevant timescales or deadlines? |

| Why | Why is the information relevant? |

| How (or how much?) | How will the change take place? How much will it cost? |

Be descriptive to help readers navigate

Elements that readers use to find information include:

document titles

section or chapter headings

headings

sub-headings

links.

The knack to writing these is to be descriptive. That is, you should be able to look at any of these elements and have a good idea what’s inside or below them.

For example, a section headed ‘Productivity’ indicates that the content is something to do with productivity. It’s vague.

But the section heading ‘What is productivity and why is it important’ leaves the reader in no doubt about what’s below.

One useful way of judging the usefulness of any of the elements above is to imagine they’re being read by a screen reader. These are devices that read online content to people with restricted vision or blindness.

A good title, heading, sub-heading or link should give you a clear idea of their content.

Avoid wordy paragraphs

Your aim is to provide your readers with information that’s accurate and clear at first reading.

As readers we all instantly judge a piece of writing on its appearance. If it’s presented in blocks of text – no matter how well written – we’ll judge it harshly.

Keep paragraphs short and use plenty of headings and sub-headings to introduce new subjects or to highlight different aspects of the subject you’re writing about.

Tips for writing online

Publishing our briefings online has implications for how we write and structure our briefings, to make sure they’re accessible to our readers.

This section of the guide covers the following:

Structuring online briefings

Reading online differs in two crucial respects from reading printed content:

1. People read screens more slowly: by up to 25%.

Faced with the first point, in an ideal world, writers would reduce their online content by up to 25%. This isn’t always possible, of course. But the way we structure our writing and help our readers to navigate our content can have a big impact.

2. People are impatient: if they don’t find information quickly they move on.

To help satisfy this second point, plain language techniques are especially useful. Or, to put this another way, readers are more likely to skip a passage they find difficult to read because it uses:

inflated language

long sentences

hidden verbs or passive verbs

jargon.

Reading online contrasts with reading printed content in a third crucial respect:

3. People don’t read screens, they scan

People scan screens in a particular pattern. In general, they’ll:

read the first sentence or two

scan the beginning of sentences and bullets

scan down, looking for relevant content

avoid reading blocks of text.

In response to this, writers need to do the following:

Use bullet points and make sure sentences at the start of paragraphs are relevant.

Use links, headings, sub-headings and bold text to guide readers.

Think of content as chunks of information.

Use summaries to get to the point

Summarising its content at the beginning of a section sets the context and allows readers to work out if it's relevant to them.

Readers scan online content in an 'F pattern'

Research shows that online users scan web pages in a particular pattern: an F pattern. This research shows that online users:

read the first sentence or two

scan down bulleted lists

scan along the first few words or lines of paragraphs.

This means that the first two sentences of your page take on a particular importance. For this reason, summaries work well when you introduce a new subject area. So, if your reader doesn’t read your briefing from start to finish, they’ll quickly see what each subject area is about.

Writing a summary

Here’s a good example from part of a briefing summarising the work of sheriff courts in the context of civil justice:

Sheriff courts are Scotland’s local courts. They deal with both civil and criminal business. Civil cases with a monetary value of up to £100,000 must be raised, in the first instance, in the sheriff courts.

You can see how this works in our example online briefing.

A good summary will answer your readers’ key questions.

Use bullet points and make sure sentences at the start of paragraphs are relevant

Lists are especially useful online as they help readers scan. They’re one of the things we’d consider a chunk of information online.

Research on the F reading pattern shows that online users often scan the first few words of a list to find out if it’s relevant to them. This is a useful tip for writers as we can put important information at the start of lists. This technique is called frontloading.

Interestingly, passive verbs can help you do this. While our advice is to aim for more active than passive verbs online, this technique helps give your writing impact. Here’s a good example (originally from Fife Council’s web pages):

Cans and plastics

Cans and plastics are taken to a transfer station for bulking before transport to Grangemouth

They are then sorted into various grades of plastic and metal

The plastics are recycled into various plastic materials. This includes carrier bags, bins and plastic furniture

The cans are then sorted into Aluminium and Steel for metal processing companies

Use links, headings, sub-headings and bold text

These are all important parts of a page that help readers move through your content.

Write links that describe

A reader should know where a hyperlink will take them before they click on it. When writing links:

Do explain what will happen if you click, for example: Open the online glossary.

Do use descriptive language, for example: How much does the service cost?

Do use action words at the start of links, for example: Download an application form.

Don’t write ‘Click here’: this is repetitive and doesn't explain what will happen if you click.

Don’t be clever: readers will just ignore you.

Don’t use repetitive links such as ‘Continue reading’ – because they’re repetitive.

Headings and sub-headings will help you create chunks of content

Use plenty of headings and sub-headings to guide readers to content: more than you’re used to in conventional writing. Pull out important points in bold.

The knack to writing these is to be descriptive. That is, you should be able to look at any of these elements and have a good idea what’s below them.

A good title, heading, sub-heading or link should give you a clear idea of their content. Our example online briefing shows you how this works.

Use bold to emphasise an important point

Don’t use capital letters, italics or underlining to stress an important point. These can be difficult to read or interpret online. If you have an important point to make, just pull it out in bold.

Of course, don’t overuse this technique or most of your writing will be in bold!

Plain language writing techniques that work particularly well online

The plain language writing techniques described earlier in this guide are particularly suited to writing online content.

Sentence length is particularly important as we know people read online content more slowly, and tend to scan.

Similarly, you can often cut your word count by finding hidden verbs in your drafts and editing them out.

Content that uses more active than passive verbs helps readers move through information quickly.

Passive verbs may also risk inflating the tone of writing. So using many more active verbs also helps set the reader-friendly tone that’s at the heart of effective web-writing.

This is also a huge benefit of using more everyday words and phrases when writing online content. Ultimately, your goal is to inform your readers, not impress them with your vocabulary.

And no-one ever stopped reading complex information because they found the language too easy.

Explaining technical words and phrases in your briefing

Writing online gives us new opportunities for explaining technical words and phrases.

But the advice to explain what you mean at the point of reading still stands.

Consider creating a ‘Useful definitions’ section the beginning of your briefing. Use this section to explain terms, phrases, acronyms and abbreviations that you think your readers will need.

We recommend you include terms that you use more than once in your briefing here and link them from the content to this section.

You should also:

explain what you mean or give examples the first time you use a word or phrase

spell out acronyms and abbreviations the first time you use them.

Editing your work: grammatical and final checks

Setting aside time for a final edit will help to support plain language writing techniques. Pay particular attention to:

Adjectives: do you need them?

The answer to this is often ‘no’. Every word needs to earn its keep. The following sentences read reasonably well (some may need a tweak) without the highlighted adjectives or adjectival phrases:

The advice appears in five different languages.

The changes were introduced in a series of phases.

This has been the case for a number of years.

The advice applies to each individual team.

This will be needed for planning ahead.

The department is in close proximity to the directorate.

A system is in place to give advance warning.

Using 'key'

One adjective worth checking on is ‘key’. It slips all too easily into writing and is often superfluous. If you have ‘key priorities’ it suggests you have priorities that don’t matter, which doesn’t really make sense. If you have ‘key stakeholders’, then other stakeholders might be unhappy about the implication that their views matter less.

Apostrophes

Our expert’s have developed a new product your going to love. Its simple and street’s ahead of what our competitor’s are offering.

If you see nothing wrong with this example, please always check your use of apostrophes.

The golden rule is: if you’re not sure, don’t guess: always check.

Commas

Punctuation isn’t optional. Good punctuation helps readers’ understanding. Bad punctuation can cause misunderstanding and confusion.

Generally, use commas to separate parts of a sentence. They can, for example, separate clauses:

Parliament has ultimate responsibility for the legislation it passes, subject to judicial review.

They can also enclose information within a sentence that is not essential to the meaning of the sentence. For example:

The committee, which comprised seven members, agreed to remit the question to the Government.

But if all the elements of the sentence are essential, omit the commas. (Many grammarians also recommend using ‘that’ rather than ‘which’, but others disagree):

The sub-committee that met last week recommended taking no further action

The sub-committee which met last week recommended taking no further action

Use commas to separate an introductory element from the rest of a sentence:

In June, Salmond said that the Government was prepared to listen to opposition proposals

Without a comma, such a sentence could cause confusion:

In June Salmond said that… (Who is June Salmond?)

Use commas to separate noun phrases where one element defines or modifies the other (called apposition). For example:

Nicola Sturgeon, the First Minister, said, ‘Where would we be without SPICe?’

Commas also separate items in lists or between adjectives. For example:

The Bill was long, technical, complex and controversial.

The Oxford comma

In the last sentence, many would use a comma before ‘and’, that is: ‘The Bill was long, technical, complex, and controversial.’ This is often called an ‘Oxford comma’. Our advice is to use the Oxford comma where it improves the clarity of a sentence. For example:

The Government has published two reports, ‘Housing and Poverty’, and ‘Benefits and Employment’.

However, in many cases commas are optional and are used to make it easy for readers to follow your text in a natural way, and to make your meaning clear. Long sentences with no commas are difficult to follow, can lead to confusion and the possibility that the reader will misunderstand what you are trying to say.

Remember the panda that eats, shoots and leaves.

Conjunctions: 'and', 'but' and 'because'

Starting a sentence with ‘and’, ‘but’ or ‘because’ isn’t a matter of grammar. It’s a matter of style.

Some people don’t like it, so do it with care. But if you don’t want to, don’t. If you do it well, few people will notice. If you overdo it, everyone will.

Infinitive: to split or not?

There’s no grammatical rule against splitting infinitives.

The infinitive is a basic form of a verb and in English always comprises two words, such as ‘to come’, ‘to laugh’ and ‘to cry’. Splitting it means inserting a word between ‘to’ and the second word, such as: ‘to boldly go where no man has gone before’.

In practice, few people notice them and even fewer believe writers should avoid them.

Prepositions: use carefully

“A preposition is a terrible thing to end a sentence with.” – Winston S Churchill

Examples of prepositions are: at, by, for, from, in, of, on, to, with, about and after.

They link the component parts of sentences – such as verbs and nouns. For example:

The cup was on the desk but I knocked it on to the floor.

Common errors with prepositions include: using ‘in’ rather than ‘within’. For example:

I will repay the loan in a year

I will repay the loan within a year

Example 1) indicates I will repay the loan at the end of the year, while 2) means I’ll repay it before the end of the year.

Bills are introduced in the Parliament rather than to the Parliament. Other examples:

"The team leader has responsibility to monitor and co-ordinate the work programme."

This should be ‘…has responsibility for monitoring and co-ordinating the work programme.’

The Churchillian quote that heads this section suggests that it is wrong, or at least grammatically suspect, to end a sentence with a preposition.

Churchill is also reputed to have said that ending a sentence with a preposition is ‘something up with which I will not put’. So what’s that all about?

The point is that some people may prefer not to end a sentence with a preposition, but it’s better to do so than write something stilted in an effort to avoid doing it. For example, ‘Which book are you quoting from?’ sounds more natural than ‘From which book are you quoting?’

Ending sentences with prepositions (or not) is a matter of style and preference, not grammar.

In any case, don’t add an unnecessary preposition to the end of a sentence. For example: ‘The Committee will issue a call for evidence later on.’ The final ‘on’ is superfluous.

Sentences and non-sentences

Look out for sentences that aren’t sentences. This is often when people use a comma instead of a full stop. The following example shows this:

The Education and Culture Committee will meet in Inverness and Aberdeen, this is in response to feedback from schools.

In the next example, the writer has hurriedly inserted a full stop after ‘facilities’ but hasn’t noticed that this leaves the second ‘sentence’ without a subject:

The regeneration has led to new housing, restaurant, bars, hotels and leisure facilities. All of which has helped transform the perception of Leith to somewhere people are happy to live, work and relax.

Slashes, and/or

Don’t make readers guess. You’ll often see a forward slash in writing, leaving the reader to guess if it means ‘and’ or ‘or’. It’s easy to avoid.

Similarly, the phrase ‘and/or’ forces the reader to stop momentarily and work out the permutations. It’s just as easy to write ‘the first thing, the second thing or both’. For example:

This will help us identify changes in the behaviour of adults and/or children

This will help us identify changes in the behaviour of adults, children or both

Spelling: check, don't guess

The golden rule is always to check if you’re in any doubt. Even people confident of their ability to spell have words they’ll need to check now and again. The following list comprises words that people often mix up or misspell, but it’s far from exhaustive:

accommodate

commitment

complement, compliment

its, it’s

led, lead

liaise

license, licence

practise, practice

principal, principle

stationary, stationery

their, there, they’re.

Tenses: be consistent

Consistent verb tenses clearly establish the time of the actions you are describing. Changes in verb tense help readers understand the time relationships among various events.

Conversely, changing tenses when the time of the action you are describing has not changed, causes confusion. For example:

The Scottish Government is considering changing the rules which govern this matter so that when applicants made applications they received immediate notification.

In this sentence, ‘is considering’ is present tense; ‘made’ and ‘received’ are past tense and there is no logical reason for the change of tense.

Style guidelines

This section deals with our standard approach to stylistic issues. It is in alphabetical order.

Abbreviations

Don’t use full stops in common abbreviations or acronyms. For example: NATO, MSP, Mr, Ms, SPCB. Follow the same style for page numbers, such as p1, pp1-4 and so on.

Bullet points

Use these to split long sentences, or to present a list of related issues or points.

There are two types of bulleted list. One is a single sentence. The following bulleted list describes single-sentence lists and how to punctuate them.

This is a single sentence list, so you:

start with a capital letter and introduce the list with a colon

start each bullet with a lower case letter – not a capital

finish the last bullet with a full stop.

The second type of bulleted list is a list of separate points, each one a standalone sentence. The following list describes these and how to punctuate them.

This is a separate points list, in which each element is a sentence in its own right.

Start the list with a standalone sentence, like the one above, and insert a space before starting the next sentence.

Each bullet is a standalone sentence, so must start with a capital letter and end with punctuation, such as a full stop.

This type of bullet has one great advantage. That is, you can insert more than one sentence into each bullet point.

But don’t make bullets too content-heavy as that just defeats their purpose.

Dates

Use this format: 21 July 2015 (not 21st July or July 21). For example: ‘The report will be released on 21 July 2015’.

Numbers

Spell out numbers one to nine, then use 10, 11 and so on. But if a sentence starts with a number always write it in full, for example: ‘Fifteen protesters attended the meeting’.

Parliamentary terminology

This section contains explanations of common terms and phrases used in connection with the Scottish Parliament.

As a parliamentary research service, it is vital that we use the correct terminology and language when describing any aspect of the legislative process or when discussing parliamentary procedures. We must all, therefore, familiarise ourselves with parliamentary terminology and procedures.

You can find more detailed information on parliamentary procedures in the Parliament’s Standing Orders. Additional guidance on public bills, private bills and hybrid bills is also available.

We provide specific advice on the use of the following phrases:

The Parliament

Always refer to the Scottish Parliament as the Parliament, rather than just ‘Parliament’. This helps to reduce the likelihood of confusing the Scottish Parliament with Westminster, for example: ‘There is a Bill going through Parliament at the moment on this subject’.

The convention of referring to the Parliament is based on the Scotland Act 1998 and the standing orders, and is used in most Scottish Parliament documents.

If you’re writing about both the Scottish Parliament and Westminster, refer to the latter as ‘the UK Parliament’ or ‘Westminster’ rather than simply as ‘Parliament’.

The Scottish Government

The Scottish Government (previously the Scottish Executive) comprises the First Minister, ministers, the Lord Advocate and the Solicitor General for Scotland. These are known collectively as the Scottish Ministers (Scotland Act 1998, section 44).

The Scottish Administration covers, in addition to these office bearers, the staff of their departments (Scotland Act 1998, section 51). This includes the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service.

Junior Scottish Ministers appointed under section 49 of the Scotland Act 1998 are also members of the Scottish Government. In Sessions 1 and 2, these posts were referred to as ‘Deputy Scottish Ministers’.

The SNP Administration, elected in May 2007 (Session 3), adopted the term ‘Scottish Government’ to refer to the Scottish Executive/Scottish Administration. It also used ‘Cabinet Secretary’ to refer to Scottish Ministers.

Section 12 of the Scotland Act 2012 renames the Scottish Executive as the Scottish Government for all purposes.

'Cabinet Secretary', is the term used for ministers who attend cabinet meetings. The term ‘Minister’ is used to designate junior Scottish Ministers. The latter do not normally attend cabinet meetings. Use these terms in our briefings and in your general communication, such as emails.

Sessions

Under the Standing Orders (Rule 2.1.1), the period from the first meeting of the Parliament after a general election until the Parliament is dissolved is known as a ‘session’.

A session is normally a period of five years. The Scottish Elections (Reform) Act 2020 set this as the standard term. However, a session may be less than five years if the Parliament is dissolved early to allow for an extraordinary general election.

The Scotland Act 1998 originally set the length of a session at four years. The elections before session two, session three and session four followed this pattern. Arrangements were made for the elections for session five and six to be held after five years in order to avoid clashes with expected elections to the UK Parliament.

Using sessions to reference parliamentary publications and items of business

Most Parliamentary publications and items of Parliamentary business are numbered by reference to sessions. All these numbering series will re-start from 1 in a new session.

For example, the Abolition of Feudal Tenure etc. (Scotland) Bill is SP Bill 4 (Session 1) to distinguish it from the 4th Bill introduced in the second or subsequent sessions of the Parliament.

A session at Westminster has a different meaning to a session in the Scottish Parliament

At Westminster, the period between general elections is known as a ‘Parliament’. Each Parliament is divided into sessions of about a year.

The Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 introduced a five-year fixed term to Westminster with each parliamentary year running from May, following the Queen’s Speech.

Avoid using session to mean a shorter period. It’s sometimes been used to refer to the period until the next recess, or to the current sitting day.

Such careless usage can cause genuine uncertainty when announcing, for example, Bills that will be introduced ‘later this session’.

Parliamentary years

Each session is divided into Parliamentary years (Standing Orders, Rule 2.1.2). The first Parliamentary year begins the day the session begins; subsequent Parliamentary years begin on anniversaries of that date.

So there will normally be five Parliamentary years in a session. Each will usually begin and end on a date in May except for the fifth year, which ends on the date of dissolution. Committee annual reports, for example, cover the period of a Parliamentary year (Standing Orders, Rule 12.9).

Other time periods

Longer periods when the Parliament and committees don’t meet are referred to as recesses. There are normally recesses in February, at Easter, in the summer, in October and over Christmas and New Year.

It may sometimes be convenient to refer to the periods between recesses as terms, but this isn’t defined in the standing orders.

You may refer to weeks when the Parliament and committees are meeting as sitting weeks, and individual days in such weeks as sitting days (Standing Orders, Rule 2.1.3).

Generally, each day’s business in the Chamber is referred to as a meeting of the Parliament (Standing Orders, Rule 2.2). Occasionally, there may be two meetings in one day.

If a committee meets in the Chamber, that is simply a meeting of the committee, not a meeting of the Parliament. A ‘Committee of the Whole Parliament’, involving all MSPs, is still a committee meeting rather than a meeting of the Parliament. It follows committee procedural rules, with the Presiding Officer or their deputy as convener.

The power to legislate

The Scottish Government has a legislative programme and introduces bills as part of that programme. But it is the Parliament that passes bills, not the Scottish Government.

Do not describe the Parliament as ‘enacting’ legislation. The most the Parliament can do is pass a bill; only the Sovereign has the power to make it an Act. The Sovereign does this by giving Royal Assent.

Bills and their passage

Always refer to bills that have been introduced by their full short title, including any ‘etc.’ and ‘(Scotland)’. But do not refer to a bill as ‘the XYZ Bill’ before it has been introduced. This may mislead people into thinking it is available.

Refer to a draft of a bill that’s published before introduction as, for example, ‘the draft Land Reform Bill’. If there’s no published draft, you should refer to a bill that’s not yet introduced as, for example, ‘the proposed Housing bill’.

If you don’t yet know the short title, write ‘the Government’s proposed bill on housing’.

Members' bills

Don’t refer to Members' bills as ‘private members’ bills’. This is the Westminster term, and if you use it, you risk confusing Public Bills - which include all Government Bills, Members’ Bills, Committee Bills and Hybrid Bills - with Private Bills. Private bills are introduced by non-MSPs to gain a private or personal benefit.

Where a member has lodged a proposal for a member's bill, don’t refer to it as if it was a bill or even a draft bill, unless a draft has been published.

All bills are published by the Parliament

Although Ministers introduce Government bills, they’re published by the Parliament, just like all other non-draft bills. Bills are Parliamentary documents, governed by Parliamentary copyright. Acts, by contrast, are Crown publications, under Crown copyright.

The Scottish Government can only lodge amendments to bills

The Scottish Government does not have the power to amend bills, including Scottish Government bills. The Scottish Government can, of course, lodge amendments. But any decision about whether to agree to an amendment is taken by a committee (at Stage 2) or by the Parliament (at Stage 3).

After a bill has been passed

You should continue to refer to a bill as a bill during the period immediately after it is passed. It only becomes an Act on Royal Assent, usually about a month later.

The Scotland Act 1998 makes provision for representatives of both the Scottish and UK governments to challenge Scottish Parliament legislation. They can do this in the four-week period after it has been passed. A successful challenge may mean that a bill does not become law.

The Parliament's business programme

The Parliament, not the Scottish Government, decides on the timetable for business in the Chamber. Formally, that’s not decided until the Parliament has agreed to a business motion proposed by the Parliamentary Bureau.

In practice, the Scottish Government may know further in advance when a particular debate is to take place. However, it should not be seen to be taking the agreement of the Parliament for granted.

General formatting guidance

The guidance in this section applies to online briefings published in Fonto, as well as other SPICe outputs (usually written in Microsoft Word). We provide advise on:

Layout

Text boxes

Avoid using text boxes as sidebars as they may cause text to appear out of order on the page. They can also confuse screen readers.

Infographics and tables

You can use charts, graphs and tables to summarise statistical data and present it in a more accessible way. However some tables do not make sense when read by screen readers, so you should make them as accessible as you can.

Always create tables using the ‘Insert Table’ option. In Microsoft Word, select the Insert tab, then the Table option. This allows the content to be recognised and tagged as a table when the document’s converted to pdf. Never use tabs and spaces to create tables.

Some screen readers have table navigation facilities that depend on row and column headings. Remember the following to help you make your tables accessible:

Format headers in tables as Headings using the template styles.

Do not use merged or blank cells as these can present problems for screen readers.

If tables run over a page, repeat the headers on each page. In Microsoft Word, right click in the table, select Table Properties, then the Row tab, and tick the box ‘Repeat as the header row at the top of each page’.

Avoid tables that run across pages horizontally. In Microsoft Word, right click in the table, select Table Properties, then the Row tab, and turn off the option ‘Allow row to break across pages’.

If it makes sense for a screen reader to read a table’s footnotes before the table itself to clarify its meaning, add them as alternative text (or ‘alt text’). You can find more details about this under the 'using alt text' heading.

If you’re copying and pasting tables into a briefing, use copy and paste rather than 'paste special', then reformat the table. This is the only way that a screen reader can read the table.

If you’re not sure whether to use an infographic or table, speak to the Data Visualisation Team.

You must accurately reference statistics and other data you’ve used in graphs and tables directly underneath the insert. For example:

Source: Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) 2014

Footnotes

Keep footnotes to a minimum. As a general rule, you should include a short explanation in the text, so a reader can understand it at first reading.

You can use footnotes sparingly for non-essential elaborations of the main text. However, think carefully about the impact this may have on a reader’s ability to understand what you have written.

Where longer explanations are needed, consider how best to present this information – for example in an emphasis box (Fonto) or in a dedicated definitions section at the beginning of the document.

Use alt text to describe images and sound

Using 'alt text' is important

If you’re using an image in your briefing, and the content of the image is important to your readers, make sure you include an alternative text description. This is called ‘alt text’. It describes the image. Ensure the description is short, succinct and descriptive.

Each time you upload an image in Fonto, you must fill in the 'alternative description' field.

To add alt text or to see existing alt text in Microsoft Word:

right-click on the image

select 'View Alt text'.

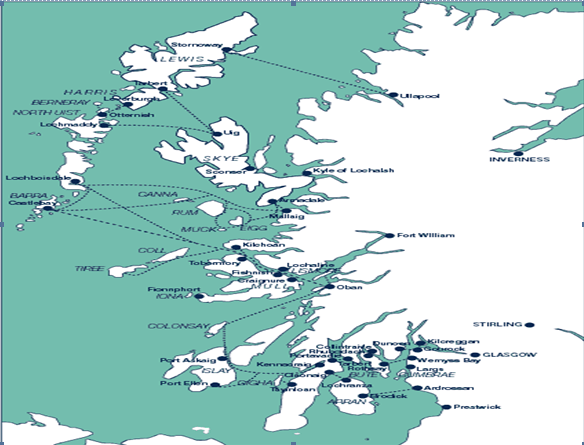

The alt text for this image is: 'Map of Scotland showing route network of ferry services provided by Caledonian MacBrayne in the Clyde and Hebrides'.

Even purely decorative images need an 'alt text' entry

If the image is purely decorative, there is no need for an alt text description. However, it is important that screen readers are still given instructions to interpret the image as decorative. You can tick the 'Mark as decorative' option in the 'View Alt Text' tab in Microsoft Word. Alternatively, you can add Alt=" " or Alt="" to the alt text box.

Infographics should also have 'alt text' descriptions

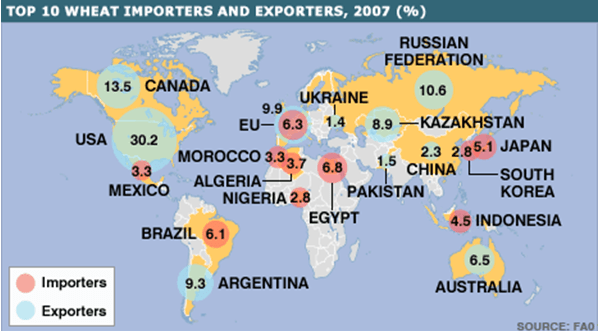

Add short alt text for charts, graphs, maps, and geographic information systems (GIS)-generated material (like the one below).

For example, the alt text for this image could be: ‘Map of the world showing the top 10 wheat importers and exporters, 2007’. The text should describe what the image is trying to convey, rather than the image itself.

Describe the information presented in the image in more detail in the text next to the infographic. It's important we don't exclude disabled users from information by making it only available to sighted users.

Sound and video files should have a transcript

If you’re embedding video or sound content in your briefing, provide a text transcript if you can. Videos should have captions if possible.

Colour and contrast are important for people with a visual impairment

For some people with visual impairment, a bright background can make an electronic document difficult to read. They may use high or reverse contrast to change the way their screen is displayed to make it easier to read, for example white or green text on a black background.

Try where possible to use sufficiently contrasting foreground and background colours in text, tables and images.

Be aware of colour-blindness issues by not relying only on colour to convey information.

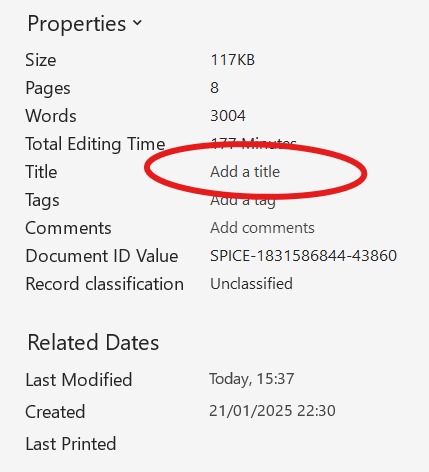

Metadata

You can make documents more accessible by adding metadata, that is, data about the document itself. Readers can then use assistive technology to interpret and display this data. It can also make documents easier to search and find.

Microsoft Word documents need a document title in order to pass an accessibility check. You can add this by:

clicking on the 'File' tab

selecting 'Info'

filing in the 'Title' field in the 'Properties' section.

Make sure Fonto briefings use the correct 'tags'

It is important that Fonto briefings contain the correct metadata - in the form of -'tags'. Without metadata, the briefings will not come up in subject matter searches of our briefings webpage. The 'Fonto User Guide' (saved in the SPICe Sharepoint site) contains more information.

How to use our templates

Published SPICe briefings are now produced using Fonto, our online authoring tool. This has a built-in layout and styles. However, other SPICe outputs continue to be produced in Microsoft Word. The following guidance relates to SPICe publications other than SPICe briefings.

This section of the guidance looks at:

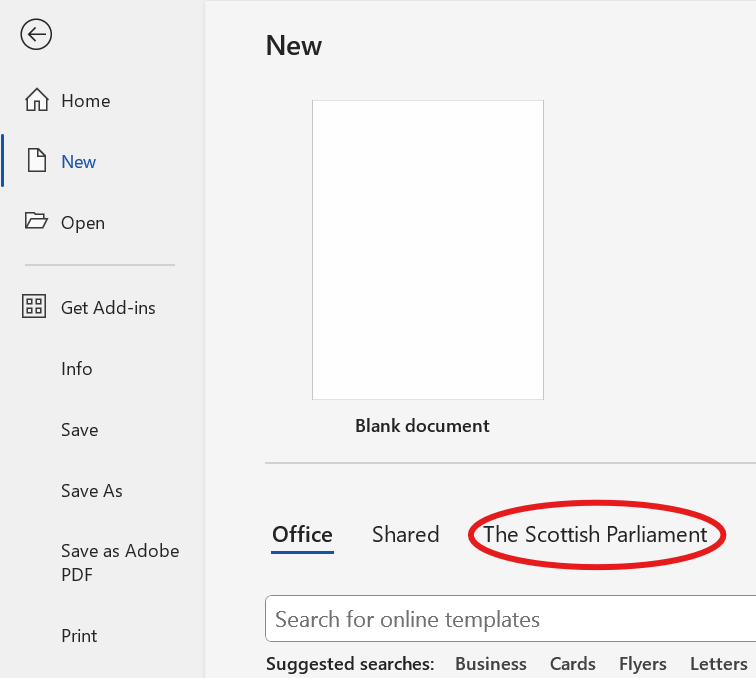

Finding SPICe templates

You can access templates for various types of SPICe briefing in Microsoft Word:

from the File tab, click on 'New'

below the 'Blank document' tile, there is an option to search for templates

click on 'The Scottish Parliament' tab

select the appropriate template from the SPICe folder.

Headings and styles in Microsoft Word

Always use the headings and styles that we’ve built into the templates.