Draft Climate Change Plan - Background Information and Key Issues

This briefing relates to the Scottish Government's Draft Climate Change Plan: 2026 - 2040. It provides background information on climate change, related legislation and targets, and key issues.

Summary

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change notes that human activities "have unequivocally caused global warming", and that global emissions continue to increase due to "unsustainable energy use, land use and land-use change, lifestyles and patterns of consumption and production across regions, between and within countries, and among individuals". This is leading to "widespread and rapid changes in the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere and biosphere" resulting in "many weather and climate extremes in every region across the globe", and "widespread adverse impacts and related losses and damages to nature and people".

In 2022, Scotland recorded its highest ever temperature of nearly 35°C in the Scottish Borders, impacting health, ecosystems, and infrastructure. In 2023, prolonged rainfall followed by Storm Babet led to widespread flooding and several deaths, as well as substantial disruption to transport and power systems.

By contrast, the geopolitics of tackling the climate emergency have changed significantly in the last 5 years, with recent international climate negotiations being described as "divisive" and a "reality check on just how much global consensus has broken down over what to do about climate change". Nevertheless, public awareness and consensus in Scotland on the need for action remains high, with 72% of respondents to a recent survey feeling that "climate change is an immediate and urgent problem".

Scotland has slightly more than halved it's greenhouse gas emissions in the last 30 years, but will have to nearly half them again in the next decade to come close to achieving domestic targets, and contribute to achieving UK and international goals. Recent data shows that decarbonisation efforts have stalled, with emissions flat lining since 2020; Scotland has failed to meet nine of its thirteen legislated annual targets since 2010 and four out of five since 2018.

The 'hard yards' of decarbonisation will therefore require detailed, strategic and co-ordinated scrutiny across multiple portfolios. Failure to meet future annual targets will increase the risks of Scotland missing its long-term emissions reduction goals.

Three key pieces of legislation provide for a statutory framework to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases in Scotland. There is also a requirement to publish a document (known as a Climate Change Plan - CCP). The draft CCP was published in November 2025, marking the start of 120 days of parliamentary scrutiny. This Plan outlines how the Government intends to meet emissions reduction targets across all portfolio areas and sectors of the economy and covers the period 2026-2040 as Scotland looks to be ‘net zero’ in carbon emissions by 2045.

This will be the first time the Scottish Parliament has considered a statutory CCP in draft form since the 'net zero' target was set in 2019. The draft Plan must include information on how they will reduce emissions in the following sectors:

Energy supply

Transport (including international aviation and shipping)

Business and industrial process

Residential and public (in relation to buildings in those sectors)

Waste management

Land use, land use change and forestry

Agriculture.

In addition to this, the draft plan must contain information on various specific policy areas such as regional land use partnerships, fossil fuels, district heating, electric vehicles, a whole farm approach to emissions accounting, carbon capture and storage, and energy efficient housing. Previous Plans have contained information on behaviour change and public engagement.

Scrutiny of the draft CCP is a cross-parliamentary effort, reflecting the fact that climate change impacts across all sectors, with the Net Zero, Energy and Transport (NZET) Committee taking the lead. Scrutiny focuses on areas such as the overall trajectory of emissions, governance, policy coherence, electricity, buildings, transport, industry, waste & circular economy, land use & forestry, agriculture, and negative emissions.

One of the key issues to note when considering the draft CCP is in relation to Parliamentary timescales, and how this fits with strategic scrutiny of a crisis that needs coordinated and long-term oversight. Having waited four years for the document to be published, scrutiny of the Government's flagship strategy for tackling Scotland's territorial contribution to climate change is again being considered late in a Parliamentary session, with limited time for the Scottish Government to consider and respond to parliamentary scrutiny - and wider public consultation, as well as ongoing monitoring of the adopted plan.

This was highlighted by the NZET Committee in a recent report, who noted that a new CCP "is certainly needed in order to provide a reset on our net zero ambitions, with an improved focus on delivery", and that it will "fall to the government in power after the next election in May 2026 to implement the Plan". Therefore, "given that Parliamentary sessions and Climate Change Plans both tend to run in five-year cycles, the Committee suggests that the next Scottish Government consider a “circuit breaker”: laying the next draft earlier in the next session than this time. This would avoid a repeating cycle of draft Climate Change Plans being considered very close to the end of Parliamentary sessions, when scrutiny and response times risk becoming limited".

Detailed sectoral information on the CCP, as well as analysis of governance and policy coherence will be available at SPICe Hub: draft Climate Change Plan.

Introduction

Climate change poses a real and existing threat to human safety, health and wellbeing, economies and natural ecosystems. Mitigating and adapting to it will require a complete transformation of society and the economy. The UK and Devolved Government's statutory advisers, the Climate Change Committee (CCC), state 1:

Climate change is here, now. Until the world reaches Net Zero CO2 emissionsi, with deep reductions in other greenhouse gases, global temperatures will continue to rise [...].

The current record pace of human-induced climate change will mean that the UK’s weather and climate will continue to change over the decades ahead. The UK will experience warmer and wetter winters – raising flood risk for properties, agriculture, and infrastructure. Continued shifts towards drier and hotter summers will increase the intensity of summer heatwaves and droughts, with rising risks of surface water flooding when rainfall does occur. Sea levels around the UK will continue to rise for centuries to come.

In Scotland, the most severe and costly risk is of flooding to people, communities, buildings and business, with the UK Climate Risk Assessment noting that 2:

Flooding remains a key risk to infrastructure, and water scarcity in summer is an issue, particularly for private water supplies. Climate change also continues to affect the natural and marine environment across Scotland, as well as its agriculture and forestry, landscapes and regulating services such as pollination. High temperatures also have the potential to affect a wide range of health and social outcomes. Interactions between risks are also increasingly recognised.

The draft Climate Change Plan: 2026 - 2040 (CCP) 3, published on 6 November 2025, is a Scottish Government document which outlines how it intends to meet greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets and achieve net zero emissions, across all portfolio areas and sectors of the economy. This is the fifth iteration of a CCP since 2010, with the last Plan update published in draft form in December 2020.

A lot has changed in the last five years, not least the geopolitics of tackling the climate emergency. The recent COP30 negotiationsii have been described as "divisive" and a "reality check on just how much global consensus has broken down over what to do about climate change" 4. International diplomacy aside, there is also increasing political opposition to domestic approaches to achieving net zero emissions, with consensus on the issue described as having "shattered and reaching net zero [...] fast becoming a political dividing line" 5.

Public awareness and consensus in Scotland on the need for action remains high, with 72% of respondents to a recent survey feeling that "climate change is an immediate and urgent problem". The research revealed that trust in research organisations or scientists is also high (74%), but that there are also feelings of worry (46%), powerlessness (35%) and sadness (26%) 6. Another survey found that over half of Scots (52%) "worry a lot about climate change in everyday life" 7.

Scotland has slightly more than halved it's greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the last 30 years, but will have to nearly half them again in the next decade to come close to achieving domestic targets, and contribute to achieving UK and international goals. Recent data shows that decarbonisation efforts have stalled, with emissions flat lining around 40 MtCO₂eiii since 2020. The "hard yards" of decarbonisation will therefore require detailed, strategic and co-ordinated scrutiny across multiple portfolios 8.

This briefing provides an overview of Scotland's approach to tackling climate change. It highlights the latest climate science, and outlines the main legislative and policy provisions in Scotland. It also sets out how emissions in Scotland have reduced to date and some of the ways that climate change has recently been considered in the Scottish Parliament.

Latest climate science

Whilst, for some, the political appetite for reducing GHG emissions and tackling climate change appears to have waned since Parliament last scrutinised and reported on a draft CCP, the warnings of climate scientists have not.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report was published in 2023. It is clear that human activities "have unequivocally caused global warming", and that global GHG emissions continue to increase due to "unsustainable energy use, land use and land-use change, lifestyles and patterns of consumption and production across regions, between and within countries, and among individuals". This is leading to "widespread and rapid changes in the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere and biosphere" resulting in "many weather and climate extremes in every region across the globe", and "widespread adverse impacts and related losses and damages to nature and people" 1.

UN Secretary-General António Guterres recently noted that it was now “inevitable” that humanity will overshoot the 1.5 degree target in the Paris climate agreementi, with “devastating consequences” for the world 2.

The IPCC states, with very high confidence, that 1:

Climate change is a threat to human well-being and planetary health [...]. There is a rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a liveable and sustainable future for all [...]. Climate resilient development integrates adaptation and mitigation to advance sustainable development.

In recent advice to the Scottish Government, the CCC stated 4:

The climate is changing. Global warming has unequivocally been caused by greenhouse gas emissions, with 100% of the observed long-term temperature change attributable to human causes. Evidence of climate change is visible around the world, including in Scotland. In 2022, Scotland recorded its highest ever temperature of nearly 35°C in the Scottish Borders, impacting health, ecosystems, and infrastructure. In 2023, prolonged rainfall followed by Storm Babet led to widespread flooding and several deaths, as well as substantial disruption to transport and power systems.

Scotland's progress in cutting emissions

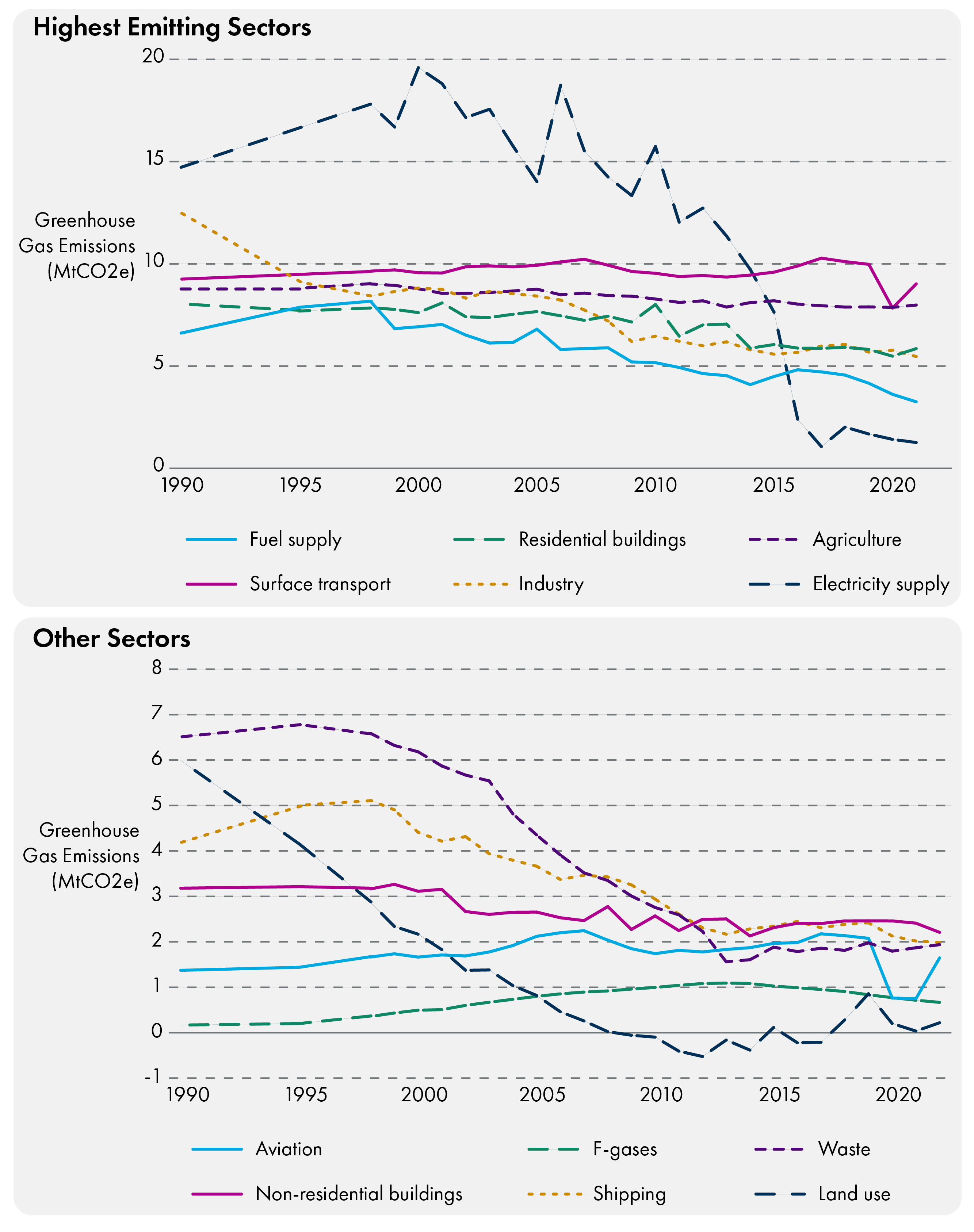

The most recent Scottish Greenhouse Gas Statistics were published in June 2025, for the year 2023. They report a 51.3% reduction in emissions since 1990. The most significant sources of emissions in Scotland currently are Transport, Industry, Buildings and Agriculture 1 .

The CCC's most recent report on Progress in reducing emissions in Scotland 2023 summarises sectoral emissions reductions as follows 2:

Since 1990, the electricity supply sector has contributed the most to emissions reductions in Scotland, driven by the phase-out of coal and the growth of renewable energy [...]. Significant reductions have also been seen in the industry, waste, and land use sectors. Emissions reductions in other sectors have been modest.

Further detail is also provided:

Transport: emissions increased by 9% from 2020 to 2021 but remain 19% below pre-pandemic levels in 2019. This was driven by a 15% rise in surface transport emissions, which remain 10% below 2019 levels. Aviation and shipping emissions fell slightly and remain 68% and 16% below 2019 levels, respectively.

Buildings: emissions increased by 6% from 2020 to 2021, with colder than average temperatures contributing to the rise.

Industry: emissions decreased by 6% in 2021 compared to 2020 levels, driven by a reduction in fuel supply emissions from petroleum refining and oil and gas extraction, likely due to extensive periods of maintenance (both planned and unplanned).

Electricity supply: emissions fell by 8% in 2021 due to a reduction in gas-fired generation. Electricity generation from gas in Scotland fell by 0.7 TWh (13%) in 2021.

Agriculture, land use and waste: emissions all increased from 2020 to 2021. There has been no progress in reducing emissions in these sectors in the last eight years.

The following infographic allows for a comparison of historical sectoral emissions since 1990:

Scotland has therefore failed to meet nine of its thirteen legislated annual targets since 2010 and four out of five since 2018. The CCC states that:

Stronger action is needed to reduce emissions across the economy to be able to meet future targets. Failure to meet future annual targets will increase the risks of Scotland missing its long-term emissions reduction goals.

Key legislation

This section sets out Scotland's statutory framework for tackling climate change.

Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009

The Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 was passed by the Scottish Parliament in June 2009. This provided a statutory framework to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases in Scotland by setting an interim 42% reduction target for 2020, with the power for this target to be varied based on expert advice, and an 80% reduction target for 2050. The Act also required that annual targets, consistent with the 2020 and 2050 targets, were set out by secondary legislation. This model of target setting has been superseded by new approaches set out in the Climate Change (Emission Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Act 2019 and the Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets)(Scotland) Act 2024 (see below for more information).

Section 35 of the 2009 Act required that after each batch of annual targets had been set, the Scottish Government produce a report on proposals on policies (RPP - now known as Climate Change Plans (CCP)) that sets out how they intend to meet climate change targets.

The Act required that a draft RPP is laid in the Scottish Parliament for consideration of 60 days and that Scottish Ministers would have regard to:

Any representations on the draft report made to them

Any resolution relating to the draft report passed by the Parliament

Any report relating to the draft report published by any committee of the Parliament for the time being appointed by virtue of standing orders.

Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Act 2019

The Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 was amended by the Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Act 2019. This increased the ambition of Scotland’s emissions reduction targets to net zero by 2045 and revised interim and annual emissions reduction targets. The changes raised the ambition of the 2030 and 2040 targets to 75% and 90% reductions respectively. The changes responded to the advice of the CCC (in the form of their Net Zero analysis) but did not adhere exactly to their recommended ambition.

The amendments also updated arrangements for CCPs to meet the targets and included new measures, such as creation of a Citizens Assembly and a Scottish Nitrogen Balance Sheet. The 2019 Act placed the monitoring framework for the Climate Change Plan on to a statutory footing for the first time, with sector by sector reports on progress (CCP monitoring reports are published in May each year) and the inclusion of matters relevant to a just transition. It also increased the parliamentary scrutiny period for the draft plan to 120 days and introduced a fixed 5-year commitment to publish a CCP:

In the case of the first plan, before the end of the period of 5 years beginning with the day on which this section comes into force

In the case of each subsequent plan, before the end of the period of 5 years beginning with the day on which the previous plan was laid.

The 2019 Act changed the model of target setting introduced by the 2009 Act and required Scottish Ministers to set annual emissions targets for each year between three major target years (2030, 2040 and 2045). It required annual targets to be calculated in a straight line between interim targets e.g. 2021-2029, 2031-2039 and 2041-2045 and as a % reduction.

Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Act 2024

The CCC's Progress in reducing emissions in Scotland – 2023 Report to Parliament stated that achievement of the 2030 target was now “beyond what is credible” and that “overall policies and plans in Scotland fall far short of what is needed to achieve the legal targets" 1.

Following this report, in April 2024 the Scottish Government reconfirmed its commitment to the 2045 net zero target, but announced plans to make "minor" changes to climate change legislation to move Scotland to a system of 5-yearly carbon budgets and away from a system of annual targets 2.

In autumn 2024, the Scottish Government introduced a Bill, which became the Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Act 2024 in November 2024. Amongst other things, the 2024 Act:

Repealed the interim 2030 and 2040 targets for emissions reduction and abolished the system of annual percentage-based targets for emission reductions set out in a straight line between the interim targets. The 2045 target of net zero emissions was retained.

Replaced the system of target setting with a system of 5-year carbon budgets, expressing the target as an amount in carbon tonnage, to be set by regulation by the Scottish Government following advice from the CCC .

Removed the requirement for a new CCP to be laid by March 2025, replacing it with the requirement for a Plan to be laid before the Scottish Parliament within 2 months of the carbon budget regulations coming into force.

Carbon budget regulations

The CCC published Scotland’s Carbon Budgets: Advice for the Scottish Government in May 2025 1.

In line with the Act, the CCC sets out their advice on the level of Scotland’s four carbon budgets, covering the period 2026 to 2045. They recommend that the Scottish Government sets its carbon budgets at annual average levels of emissions that are:

57% lower than 1990 levels for the First Carbon Budget (2026 to 2030).

69% lower than 1990 levels for the Second Carbon Budget (2031 to 2035).

80% lower than 1990 levels for the Third Carbon Budget (2036 to 2040).

94% lower than 1990 levels for the Fourth Carbon Budget (2041 to 2045).i

As previously noted, the most recent Scottish GHG statistics were published in June 2025, for the year 2023. They report a 51.3% reduction in emissions since 1990 2 .

The CCC report also sets out the actions which would be required to follow a "balanced pathway"ii to stay within carbon budgets. They describe the targets as "deliverable" but that "getting to Net Zero by 2045 will require immediate action, at pace and scale" 1.

In correspondence in January 2025, the Acting Cabinet Secretary told the Parliament's Net Zero, Energy and Transport (NZET) Committee that the Scottish Government intended to lay the regulations in late May, if possible within a week of the CCC advice 4. The Scottish Government ultimately laid the draft regulations setting carbon budgets for the next four 5-year carbon budget periods, running from 2026 – 2045 on 19 June 2025 (roughly one month after the advice). The 19 June regulations amount to an acceptance of the CCC’s overall advice on targets and are framed so as to implement it.iii

The Committee published its Report on the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 (Scottish Carbon Budgets) Amendment Regulations 2025 on 30 September 2025; the draft regulations were subject to the affirmative procedure, and were debated in the Chamber, and came into force on 8 October 2025.

Indicative Statement

The 2024 Act also provides that the Scottish Government must lay an "indicative statement", alongside the regulations. This indicated the proposals and policies in relation to each of the sectors which were likely to be set out in the next CCP. The Indicative Statement included some commentary on particular areas where the Scottish Government expected to deviate from the CCC's Carbon Budget Advice in how they intended to achieve emission reduction levels 5. The statement focuses on peatland restoration and agriculture, and notes:

For the avoidance of doubt, the pathway that is set out within the CCP will reflect the Scottish Ministers’ proposed pathway to net zero – this means that for agriculture and peatland we will not follow the CCC’s specific recommendations, instead we will implement solutions to ensure we meet our net zero and nature obligations in a way which works for rural communities.

Summary of key parliamentary scrutiny

This section sets out some of the background and context to recent scrutiny.

Background

Scrutiny of the previous draft Climate Change Plan update (CCPu) took place at at the tail-end of the 5th Parliamentary sessioni in early 2021. At that time, Scotland was still grappling with the global COVID-19 pandemic, and also considering how best to recover.

In late 2020, before considering the CCPu, the Parliament's Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform Committee carried out an an Inquiry into Green Recovery from COVID-191, noting that "Scotland has shown it can be bold in the face of a crisis", and must be "equally bold in putting systemic change at the heart of the climate and ecological crises".

This Report found that there was an "implementation gap" between what had been recommended to the Scottish Government, and what was actually taking place. Overall budgetary alignment with net-zero was also found to be vital. Subsequently, the Scottish Government "committed to a green recovery", and defined it as "[...] a recovery which sets us on a path to meeting our world-leading emissions reduction targets in a way that is just and improves the outcomes for everyone in Scotland, ensuring no one is left behind" stating 2 :

COVID-19 has demonstrated the risks of abrupt, unplanned shifts and how these exacerbate inequalities in our society. However, a green recovery offers opportunities to address these inequalities, create and maintain good, green jobs right across Scotland, and empower people and communities to make decisions about their future through community wealth building. A green recovery drives action to reduce our emissions and protect and restore our natural environment.

The draft CCP update was published on 16 December 2020. The Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform (ECCLR) Committee led scrutiny of the updated plan in collaboration with the Economy, Energy and Fair Work (EEFW) Committee, Local Government and Communities (LGC) Committee and the Rural Economy and Connectivity (REC) Committee. Following evidence sessions in January and February 2021, the four committees reported directly to the Parliament in March 2021 (ECCLR, EEFW, LGC and REC). The update set out that the next statutory CCP was to be completed by early 2025. The ECCLR Committee made a number of detailed recommendations, including calling for 3:

Clarity on the modelling, evidential base and assumptions that underpin how the plan was developed, and the associated policy decisions chosen

Demonstration of how the policies and proposals deliver the predicted emissions reductions for each sector

Clarity on timescales associated with policy and proposal commitments to ensure that these reflect the urgent nature of the climate emergency and the immediate opportunities to progress a green recovery

Reviewing the credibility of reliance on new and untested technologies, and to set out a plan B for how equivalent abatement could be achieved.

Ultimately however, the Scottish Government declined to incorporate the Committee's recommendations into the updated Plan, citing an "urgent need to finalise" it before dissolution for the election 4. Subsequently, early in the current (sixth) Parliamentary session (June 2021), the then Cabinet Secretary for Net Zero, Energy and Transport stated that implementation and delivery of climate policies "must remain our priority", and that:

the next full climate change plan [will] be brought forward as soon as possible. That approach reflects the urgency that the climate emergency demands.

The Scottish Government carried this commentary into Session 6, and the international climate negotiations in Glasgow at COP 26 in November 2021. In Glasgow their focus was on climate justice, noting that "those most affected by climate change – young people, and those from the Global South – have often done the least to contribute to the crisis" 5. Overall, the United Nations Climate Conference was described as a fragile win, with agreements on financing for climate adaptation in developing countries, and explicit mention of coal power, fossil fuel subsidies, and a “just transition” in the Glasgow Climate Pact.

Session 6 scrutiny

Early in Session 6, the Parliament ramped up efforts to develop a model for more effective scrutiny of key strategic cross-committee issues, including climate change and achieving net zero. In June 2022 the Conveners Group agreed a package of proposals to strengthen cross-cutting scrutiny of climate change (including access to expert advice, training for MSPs and regular updates from the CCC), as part of Session 6 strategic priorities. These are explored in more detail in SPICe Blogs on:

Developing a model for parliamentary scrutiny of climate change1

Delivering a model for parliamentary scrutiny of climate change: drivers, actions and next steps2

Delivering a model for parliamentary scrutiny of climate change: a Climate Change People’s Panel3.

As set out above, the lead Committee for scrutinising climate change, the NZET Committee, has scrutinised changes to the regulatory framework for GHG emissions reduction this session.

To support the Parliament’s scrutiny of the draft CCP, in February 2025, the NZET Committee wrote to the CCC, Audit Scotland, Environmental Standards Scotland, and the Scottish Fiscal Commission to ask them to set out what a "good" CCP would look like. Their full responses are linked below:

The Committee shared a summary and the full responses with the Acting Cabinet Secretary in April 2025, and encouraged the Government to consider this advice and engage with these bodies in preparing the draft CCP. Many of the concerns that were raised mirror those of the Session 5 ECCLR Committee. For example, in relation to transparency of methods and data, budgetary alignment, and clarity on policy timescales 5.

Draft Climate Change Plan

The Scottish Government published the draft Climate Change Plan on 6 November 2025, marking the start of 120 days of its parliamentary scrutiny (until 5 March 2026).

This Plan outlines how the Government intends to meet emissions reduction targets across all portfolio areas and sectors of the economy and covers the period 2026-2040 as Scotland looks to be ‘net zero’ in carbon emissions by 2045.

This will be the first time the Scottish Parliament has considered a statutory CCP in draft form since the passing of the 2019 Act. The draft Plan must include information on how they will reduce emissions in the following sectors:

Energy supply

Transport (including international aviation and shipping)

Business and industrial process

Residential and public (in relation to buildings in those sectors)

Waste management

Land use, land use change and forestry

Agriculture.

In addition to this, the draft plan must contain information on various specific policy areas such as regional land use partnerships, fossil fuels, district heating, electric vehicles, a whole farm approach to emissions accounting, carbon capture and storage, and energy efficient housing. Previous Plans have contained information on behaviour change and public engagement.

Since the 2019 legislation, the Plan must be prepared in accordance with just transition and climate justice principles. Further detail on the background to the draft CCP is explored in SPICe Blog Climate Change Plan: what’s the background and what does it need to do.

Scrutiny of the draft CCP is a cross-parliamentary effort, reflecting the fact that climate change impacts across all sectors, with the NZET Committee taking the lead.

Scrutiny focuses on areas such as the overall trajectory of emissions, governance, policy coherence, electricity, buildings, transport, industry, waste & circular economy, land use & forestry, agriculture, and negative emissions.

Detailed sectoral information on the CCP, as well as analysis of governance and policy coherence will be available at SPICe Hub: draft Climate Change Plan1.

One of the key issues to note when considering the draft CCP is in relation to Parliamentary timescales, and how this fits with strategic scrutiny of a crisis that needs coordinated and long-term oversight. Having waited four years for the document to be published, scrutiny of the Government's flagship strategy for tackling Scotland's territorial contribution to climate change is again being considered late in a Parliamentary session, with limited time for the Scottish Government to consider and respond to parliamentary scrutiny - and wider public consultation, as well as ongoing monitoring of the adopted plan. This was noted by the NZET Committee in their Report on the Carbon Budget Regulations, who made the following recommendation 2:

The Committee recognises the Scottish Government’s aim to have a finalised Climate Change Plan in place by the end of this session. A new Plan is certainly needed in order to provide a reset on our net zero ambitions, with an improved focus on delivery. The Committee notes that it would fall to the government in power after the next election in May 2026 to implement the Plan - unless it decided to restart the process by laying a new draft shortly into the new session. If not, then given that Parliamentary sessions and Climate Change Plans both tend to run in five-year cycles, the Committee suggests that the next Scottish Government consider a “circuit breaker”: laying the next draft earlier in the next session than this time. This would avoid a repeating cycle of draft Climate Change Plans being considered very close to the end of Parliamentary sessions, when scrutiny and response times risk becoming limited.