Key Issues for Session 6 - 2023 Update

This briefing has been produced by researchers in the Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe). It provides updates on some of the key issues SPICe identified as likely to be of particular interest at the start of Session 6 along with a number of new policy issues that have emerged since May 2021.The briefing is intended to assist MSPs and their staff, who are encouraged to contact SPICe if they require further information on these or any other topics.

Foreword

At the beginning of Session 6, SPICe published a briefing setting out what researchers thought would be the key issues the Parliament would consider between 2021 and 2026. At the half-way point in the Session, we have decided to revisit the briefing and provide an update.

The 2021 Scottish Parliament election took place during a global pandemic, a climate emergency and whilst the UK was adjusting to no longer being a member of the European Union. As a result, the overarching themes SPICe identified for Session 6 were COVID, climate and the constitution.

Whilst these themes continue to be important, SPICe has identified a further two overarching themes which are also commanding attention during Session 6. The first of these is the impact in devolved policy areas of the geopolitical crises caused by Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine and more recently the situation in the Middle East. The second is the impact of inflation on public services and the cost-of-living crisis. Both these new themes provide additional complexity when considering the key issues which the Parliament continues to face during Session 6.

Beneath these overarching themes, SPICe has updated 20 of the 26 issues identified at the start of Session 6. Researchers have also identified a further 4 issues which have emerged to be significant for the Parliament and are likely to continue to be significant through to the next Scottish Parliament election.

A further consideration in informing the Parliament's work this Session has been the Scottish Government and Scottish Green Party Parliamentary Group Agreement announced in September 2021, which set out how the Scottish Government and the Green Party intended to work together over the course of the Session 6 Parliament. A SPICe blog published at the time the Agreement was announced provides more information on the content of the Agreement and its impact on Parliamentary business.

The key issues identified in this briefing cover all major areas of devolved policy, from reform of school qualifications to the business base in Scotland, and from changes to family law through to changing car use. As with the original Key Issues briefing, you can read the briefing from cover to cover, or you can easily dip into the issues that interest you most.

SPICe continues to provide impartial, factual, accurate and timely information and analysis to support MSPs in undertaking parliamentary business. If you have any questions about how SPICe can help you in your duties please contact SPICe – contact details and much more can be found in the SPICe service guide, accessible on the Parliament's intranet.

Nicola Hudson, SPICe, Head of Research and Financial Scrutiny

COVID-19 Recovery Update

Kathleen Robson, Senior Researcher, Health and Social Care

At the time of the 2021 Key Issues briefing, COVID-19 was still dominating the news and driving health policy decisions and spending.

On the 5th May 2023, the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared that COVID-19 no longer constituted a public health emergency of international concern. It had been over a year since pandemic restrictions were lifted and life in Scotland had essentially returned to normal.

However, this apparent normality disguises the other health consequences that have been left in the wake of the pandemic.

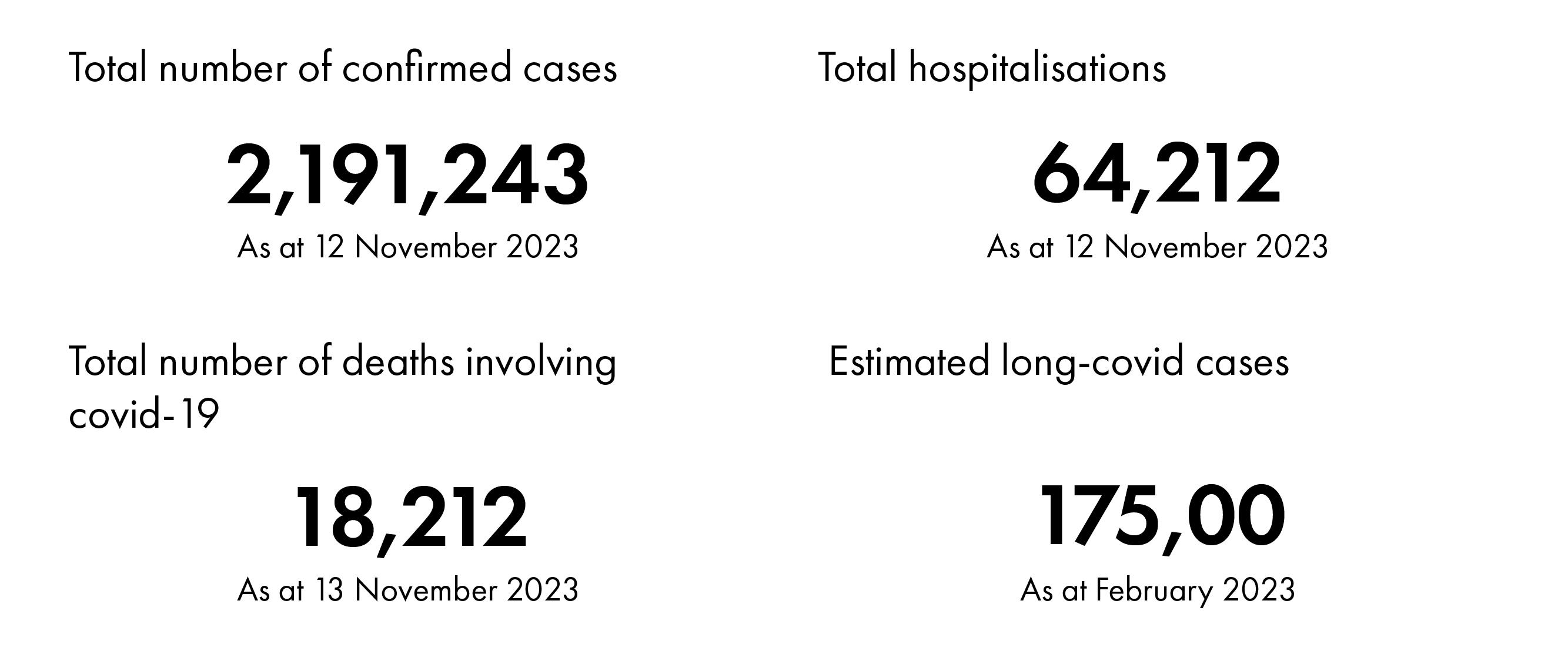

For more than two years the focus was on the direct health harms of covid. Infections, hospitalisations, ITU admissions, long-COVID and death. The grim tally is shown in Figure 1 and for many that impact is still being felt. However, attention has now shifted to the non-COVID health harms.

The Scottish Parliament’s COVID-19 Recovery Committee has now been wound up. There is no longer a Cabinet Secretary for COVID-19, and the virus is monitored in the same way as other respiratory illnesses such as flu. The COVID-19 recovery has been ‘mainstreamed’.

Business as usual?

Not quite.

The following sections focus on changes in the nation’s health and the recovery of the NHS.

Indirect Health Impacts

It was always recognised that the pandemic restrictions would have wider harms but their extent was unknown. It was suggested that the shut-down of services could lead to the late presentation of conditions such as cancer, and in turn lead to poorer survival rates and excess deaths.

Subsequent analysis did indeed show that there were 7,000 fewer cancer diagnoses made in 2020 compared to the previous year.

Data suggests that some of the ‘missed’ cancer cases may now be filtering through. Most notably this is seen in an increase in urgent GP referrals for suspicion of cancer, with many NHS boards reporting referrals considerably higher than pre-pandemic levels. This increase is creating pressure on the pre-diagnosis part of the patient pathway such as outpatients and diagnostics.

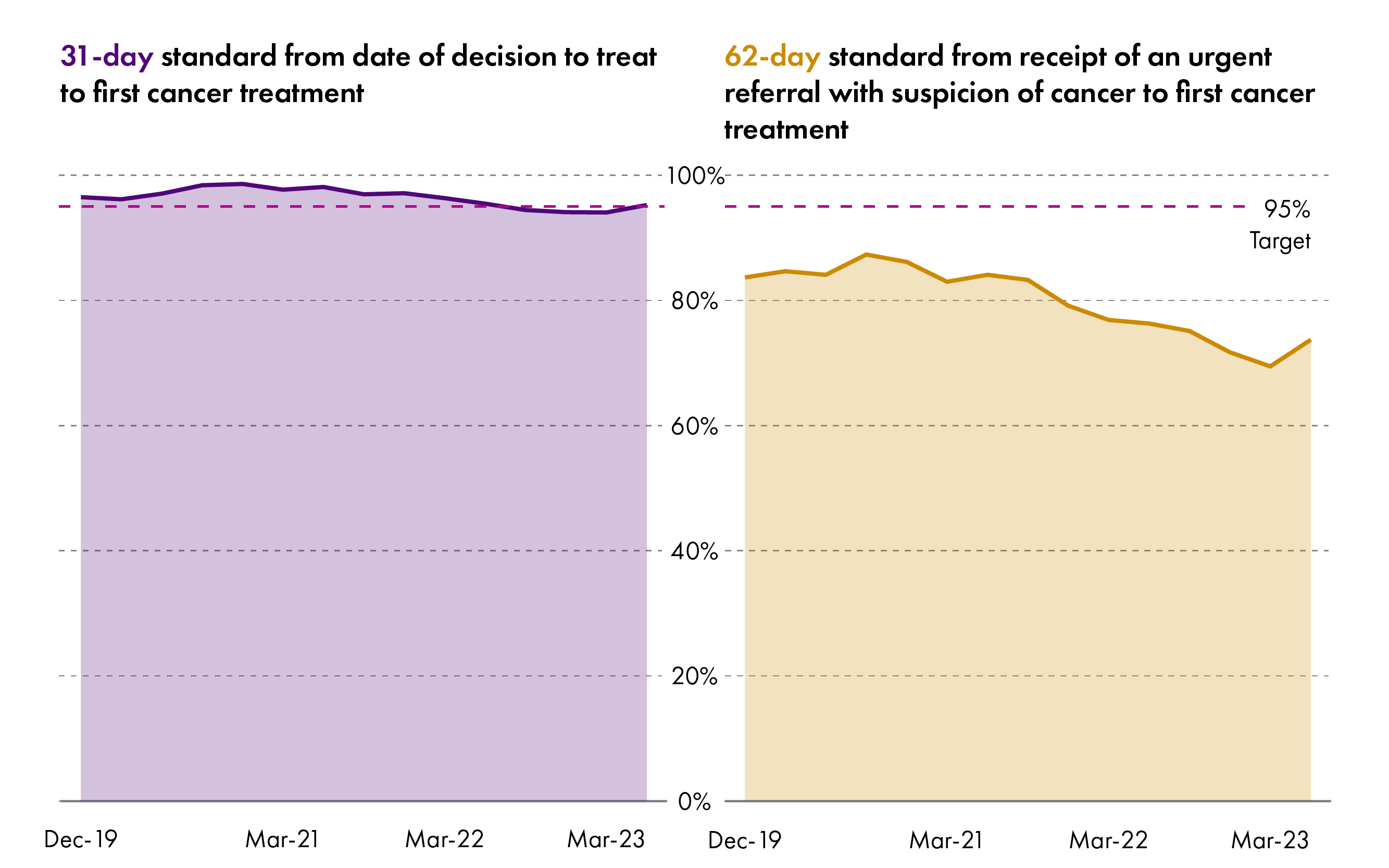

This is evident in the cancer waiting times figures which show that performance against the 62-day treatment target (that 95% of patients should wait no longer than 62 days from urgent suspicion of cancer referral to first cancer treatment) declined over the course of the pandemic. It began to recover at the start of 2023 but no NHS board in Scotland is meeting the target. In fact, the target has not been met at a Scotland-wide level since 2013.

The data also shows that for some of these cancers, there may have been a shift in the stage at which they are diagnosed.

There has been a significant stage shift (p=0.009) for breast cancer since the pandemic. This was largely driven by an increase in stage 3 diagnoses (8.4% in 2022 vs 6.6% in 2018-2019). This stage shift was more apparent for patients resident in the least deprived areas of Scotland (Public Health Scotland)

It is too early to tell whether delays in diagnosis and treatment will continue and if they will influence survival rates. However, it is generally accepted that diagnosing and treating cancer at an earlier stage results in better outcomes for patients.

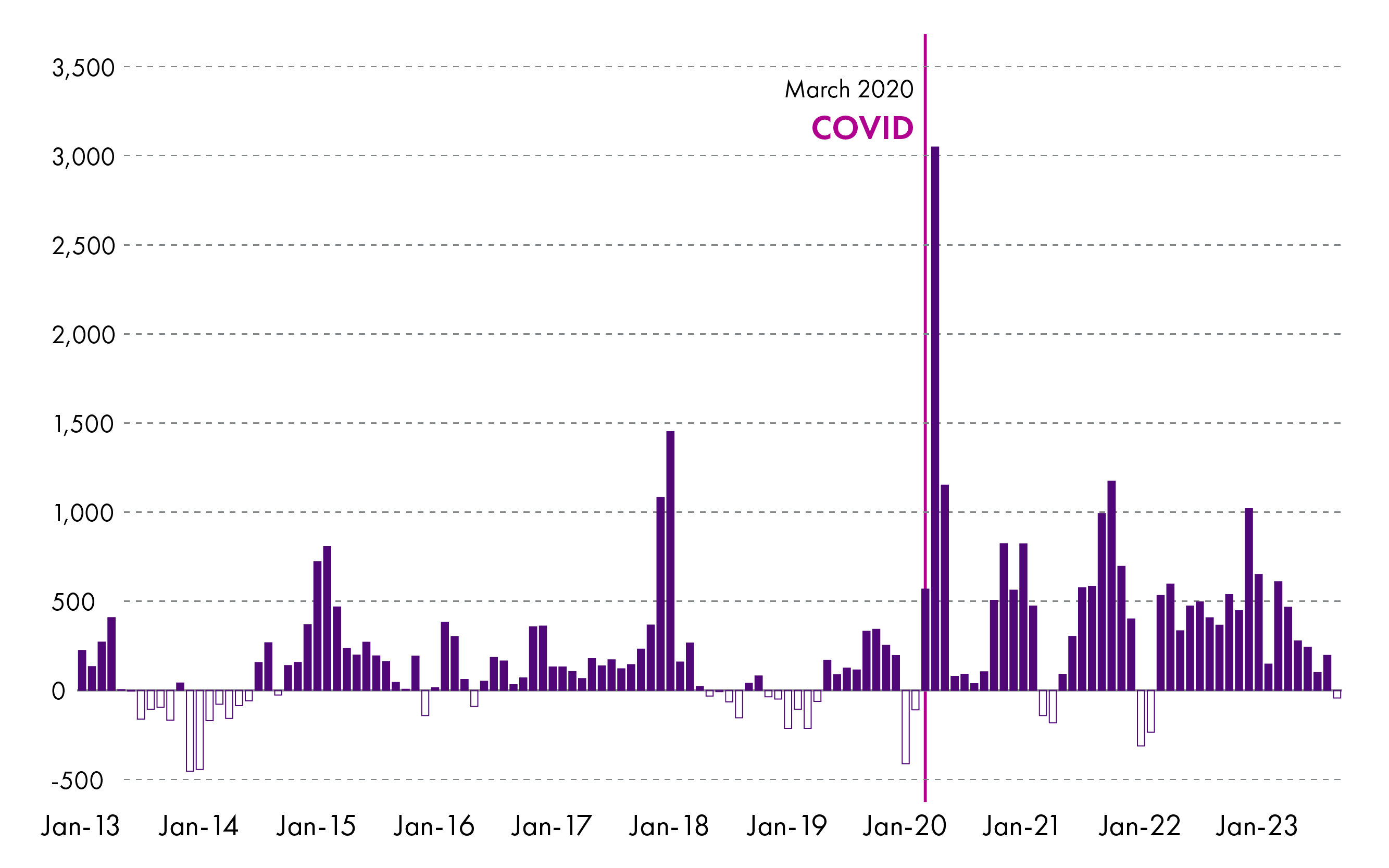

One way of monitoring this will be through the recording of excess deaths in Scotland. Excess deaths refer to the number of deaths in a certain time-period compared to the ‘expected’ number of deaths.

This was a key indicator used during the pandemic for measuring the non-covid health harms and the data showed that Scotland had excess mortality continuing after the worst of the pandemic was over.

The underlying causes of these deaths (aside from COVID-19) were attributable to cancer, dementia/Alzheimer’s, circulatory disease and respiratory conditions.

However, on a more positive note, the most recent data shows a decline in excess deaths and a return to expected levels.

Performance of the NHS

The pandemic forced NHS Scotland to suspend much of its normal activity and encouraged people to stay away except in an emergency. This caused a sharp decline in activity and a backlog in the flow of patients.

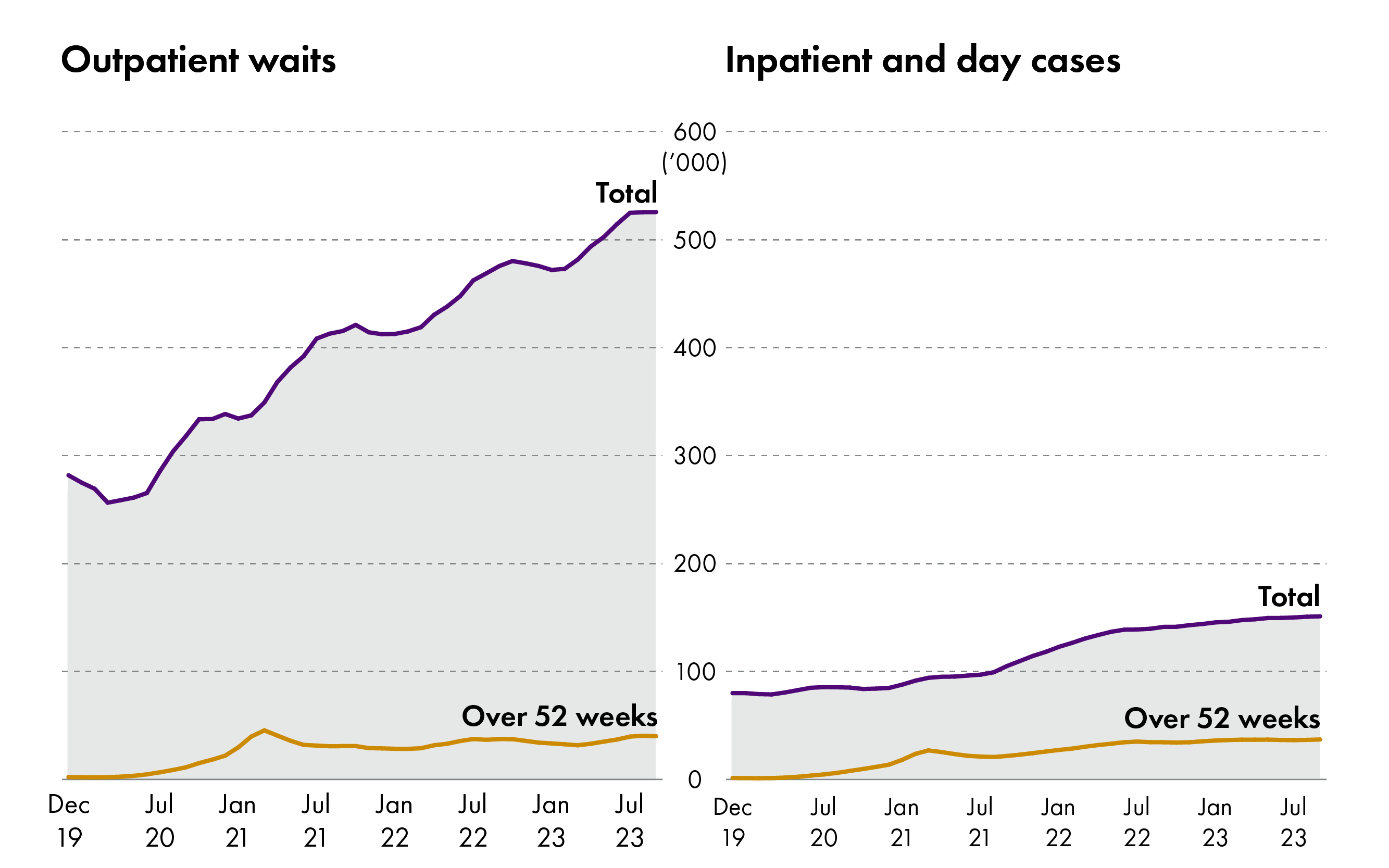

This backlog now sits at 525,654 people waiting for an outpatient appointment and 151,093 people waiting for inpatient or day case treatment. These figures should not be added together for a proportion of the population waiting. This is because individuals may be included on more than one list.

The length of waits also increased and the Scottish Government implemented new targets to reduce waiting times by the end of 2022. However, these have not been met yet.

The level of activity in many areas has not returned to pre-pandemic levels and therefore the backlog has been growing.

Since last year, the number of people waiting for an outpatient appointment has increased by 10.5% and those waiting for inpatient or day case treatment increased by 6.9%.

Funding and staffing have increased so the reasons for the drop-off in productivity are unclear but likely to be multifaceted.

A similar pattern is seen in the rest of the UK and research by NHS Providers in England found that the main reasons given by NHS Trusts for not being back at pre-pandemic levels were:

Staff exhaustion and burn out/low morale

Increased patient acuity (i.e. sicker patients)

Delayed discharges and disruptions to patient flow

Sustained pressure in emergency care

Increased reliance on agency spend

Limited use of available capacity

Continued impact of COVID-19

As well as applying further pressure to stretched services, the pandemic also served as a catalyst for reform.

One specific example of this is NHS dentistry where issues arose post-pandemic as people found it hard to access dental services at all.

Because of the aerosol generating nature of dental procedures and the need for ventilation between patients, dental services were among the last to return to normal after the pandemic.

Dentists saw their incomes drop and costs rise. Some practices responded by closing their lists to NHS patients, with others withdrawing completely from providing NHS services. This prompted reform work by the Scottish Government in association with the profession. For more information please see the SPICe blog on Dentistry.

It is yet to be seen whether these reforms will ensure NHS dental services are sustainable, but it potentially highlights the need for similar reform across the rest of the NHS.

The Scottish Government published its NHS Recovery Plan in 2021 and has made several commitments for reform including; increasing capacity, increasing spending, improving waiting times and redesigning care pathways. Innovation is also being supported by the new Centre for Sustainable Delivery and a network of National Treatment Centres.

However, the recovery plan has been criticised by Audit Scotland for not containing detailed actions which progress can be measured against. Audit Scotland also outlined that just 3 out of 14 NHS boards were expecting to break even in 2022/23 if their savings targets were met.

Against this backdrop of growing pressures and declining performance despite the raft of Scottish Government action, is it now time to consider more radical NHS reform?

Scrutiny in a climate and nature emergency – engaging with disruptive change

Alexa Morrison, Niall Kerr and Abbi Hobbs, Senior Researchers, Environment and Climate Change

Climate change is considered by some to be the ‘biggest threat that modern humans have ever faced’. The impacts of climate change and the changes necessary to address them concern almost all parts of our society, they cut across government departments and parliamentary committees.

The climate and nature scrutiny challenge – what has changed?

There were significant climate policy changes that closely preceded the beginning of Session 6. In 2019, the Scottish Government declared a climate emergency, and set a target for net zero greenhouse gases by 2045. In 2020, it updated the Climate Change Plan (CCP) setting out how Scotland would reduce its emissions until 2032, on the road to reaching net zero. As a result, ‘climate’ was highlighted as one of the key issues for Session 6 of the Scottish Parliament, as the Scottish Government began to grapple with the task of implementing the policies and programmes necessary to achieve net zero.

Alongside the net zero challenge, international reviews of biodiversity decline, with an increased understanding of how fundamentally nature underpins our wellbeing and economies, has led to an understanding that we are experiencing a twin climate and nature crisis, and increased global calls for transformative change. In 2022, COP15 of the UN Biodiversity Convention led to the adoption of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), which sets out a global target to halt biodiversity loss by 2030 and adopted a global vision of a world living in harmony with nature by 2050.

Enhancing climate scrutiny in Session 6

Turning back to domestic efforts, the publication of a CCP and a Scottish Climate Change Adaptation Programme at five yearly intervals are a requirement of the 2009 Climate Change (Scotland) Act. A later section of the briefing on ‘the climate emergency’ sets out the major policy developments that have taken place or are due to take place in this session with respect to these documents.

A further requirement of the 2009 Act was for the Scottish Government to set out the greenhouse gas emissions impacts of its spending decisions. A ‘carbon assessment’ is carried out annually alongside the Scottish Budget. The Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Act 2019 sought to advance this by committing the Scottish Government to work with the Parliament to review budget information related to climate change and a Joint Budget Review Group comprising officials from the Scottish Government and Scottish Parliament was established.

The Joint Budget Review on matters related to climate change between the Scottish Government and the Scottish Parliament recommended three strands of work; an enhanced climate narrative was included in the Budget documentation in 2023-24 and a revised approach to the climate taxonomy of budget lines including the expansion from solely capital to both capital and resource will be applied to the 2024-25 spending lines. A Net Zero Assessment methodology - to improve how carbon assessment is embedded in policy making and spending decisions – has been developed, with a pilot to commence before the end of the calendar year.

Work has also been carried out by Audit Scotland to assess How the Scottish Government is set up to deliver climate change goals. It highlighted that the ‘delivery of climate change ambitions is dependent on all eight Director Generals’ and that ‘cross-government collaboration is required to progress climate change policies and manage competing priorities’. It found that while the Government has improved how it organises itself to support delivery of its climate change goals, more systematic risk management is needed to identify the key risks to meeting climate goals.

To strengthen cross-cutting scrutiny of climate change and net zero, the Conveners Group has agreed a package of proposals, as part of Session 6 strategic priorities. The package includes annual updates to the Conveners Group from the UK Climate Change Committee and capacity building for MSPs, their staff and staff of the Parliament on sustainable development and net zero. Work is underway to deliver these proposals and to continue at the forefront of innovative climate change and net zero scrutiny by developing a model for parliamentary scrutiny of climate change. As part of this, another area of focus to the end of the Session is to build on the activities already offered to individual academics and higher education institutions through the Parliament’s Academic Engagement programme, to strengthen capacity in climate change knowledge exchange.

Continued nature decline – but opportunities ahead for change

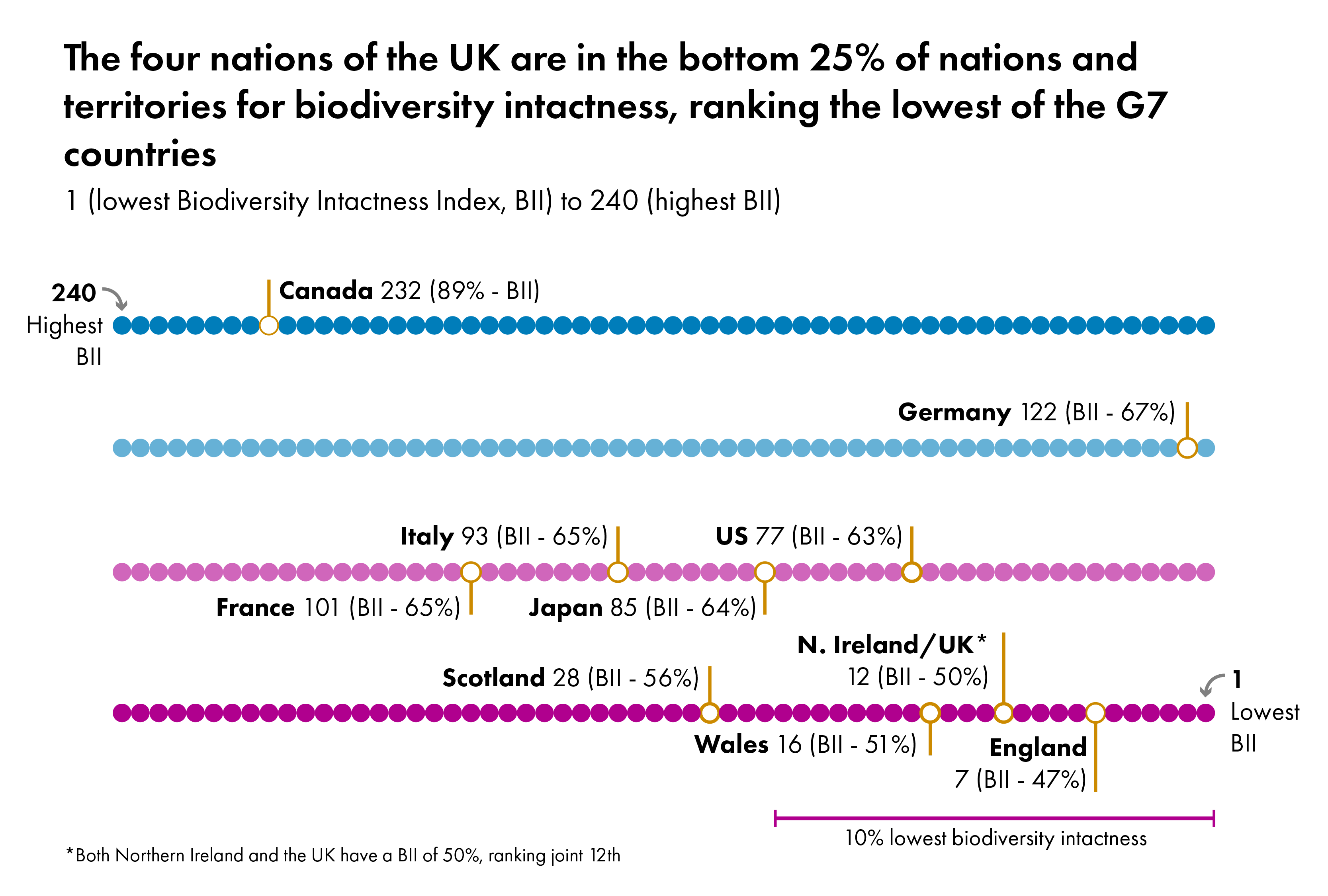

Evidence of the nature crisis led the previous Scottish Government to commit in 2019 to a ‘step change’ in efforts to tackle biodiversity loss. The SPICe Key Issues briefing in 2021 highlighted the extent of the problem in Scotland, and our failure, as with most countries, to meet most of the 2020 global ‘Aichi’ targets. A 2021 review also found that Scotland’s level of ‘biodiversity intactness’ is amongst the lowest in the world, meaning Scotland is one of the most nature-depleted countries. Scotland’s biodiversity intactness was found to be 28th from bottom out of 240 countries and territories assessed.

The 2023 State of Nature report for Scotland (generally considered to be best evidence on biodiversity trends) showed that the national picture is still of nature decline:

1 in 9 species in Scotland is threatened with extinction from Great Britain. This figure is much higher for some groups such as vertebrates.

There has been a 15% decline in average species abundance across monitored wildlife since 1994. In the last decade, 43% of monitored species have declined strongly.

Scotland’s globally important seabird populations are among the biggest concern – declining by nearly half between 1986 and 2019 – before taking into account the recent impacts of avian flu.

Key pressures on our biodiversity include intensive use of land for agriculture and forestry, overgrazing and overfishing. These pressures are exacerbated by climate change, pollution, inappropriate development, invasive non-natives and disease. The State of Nature report highlights the crucial role of natural resource management sectors in both nature recovery and tackling climate change:

Farming, fishing and forestry are important industries in Scotland, providing food, timber and livelihoods, and the current and future state of nature depends on these industries pursuing nature-friendly, sustainable approaches. The geographic extent of these industries means that careful planning and sustainable management is essential to help halt biodiversity loss and mitigate and adapt to the effects of climate change.

Against this backdrop of complex drivers, in September 2023 the Scottish Government published Tackling the Nature Emergency - strategic framework for biodiversity for consultation, which seeks to incorporate targets in the new Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. The Scottish Framework includes:

A Strategy – with a vision to halt biodiversity loss and be Nature Positive by 2030 and to have restored and regenerated biodiversity across Scotland by 2045.

A five-year Delivery Plan – including proposals to scale up nature restoration and develop an Investment Plan to target public investment

Consulting on achieving key international goals such as protecting 30% of land and sea by 2030 ('30 by30’)

The Strategy is expected to be followed by a Natural Environment Bill before the end of this Session, including legal targets for nature restoration – potentially moving biodiversity governance closer to the structure developed to tackle the climate emergency.

Proposed interventions in the Delivery Plan, similarly to the CCP, affect a wide range of sectors across the Scottish economy – from agriculture, to fisheries, development, and local government from establishing “nature networks” to public procurement. There continues to be a mainstreaming challenge for biodiversity policy – with expectations that key forthcoming areas of reform will need to integrate biodiversity goals. Opportunities include:

reform of agricultural support (with the Agriculture and Rural Communities (Scotland) Bill currently at Stage 1)

approaches to land reform (legislation is expected in the forthcoming year), and

how biodiversity is tackled hand-in-hand with the climate crisis in the forthcoming CCP.

There are also global justice considerations around how supply chains and consumption in Scotland drive nature loss abroad, and how this is tackled, for example through circular economy policy (with the Circular Economy (Scotland) Bill currently being scrutinised in the Parliament). Around 80% of Scotland’s carbon footprint comes from consumption i.e. from all the goods, materials and services used and disposed of. There is yet to be an attempt to quantify Scotland’s ‘nature footprint’.

The integration of nature across Government policy, and how this is scrutinised in the Scottish Parliament – will be a test of Scotland’s response to the nature crisis in the remainder of Session 6.

The devolution settlement post EU exit and UK relations

Sarah McKay, Senior Researcher, Constitution

The UK leaving the European Union (EU) was a seismic constitutional shift. EU exit removed an element of the UK’s constitutional framework which had been in place for nearly 50 years. The move away from EU membership has brought the devolution settlement, and how it operates outside the framework which the EU provided, into sharp focus.

This has been reflected in the work of the Parliament’s Constitution, Europe, External Affairs and Culture (CEEAC) Committee so far this session. The CEEAC Committee has held a significant inquiry into ‘How Devolution is Changing Post-EU’ and has produced two reports (the Impact of Brexit on Devolution in September 2022 and How Devolution is Changing Post EU in October 2023) which address some of the key changes in the way that devolution works outside of the EU and note some of the challenges for the Parliament as a result.

In June 2023, the Scottish Government published a paper ‘Devolution since the Brexit Referendum’ which addressed many of the same areas as the CEEAC Committee has in its work to date this session.

The devolution settlement and new constitutional arrangements

In its report ‘The Impact of Brexit on Devolution’ the CEEAC Committee noted the view of its adviser, Dr Christopher McCorkindale, that:

Brexit “has posed a number of significant challenges to the effective functioning of the UK constitution.” In his view, “territorial tension has been exposed and exacerbated by the relatively weak constitutional safeguards for devolved autonomy and the relatively weak mechanisms that have existed for shared governance as between the UK and the devolved institutions.

As part of its work, the CEEAC Committee has considered legislative consent, the UK Internal Market Act 2020, intergovernmental activity including common frameworks and delegated powers in particular detail. These issues are covered in more detail in the section of this briefing titled ‘The changing face of devolution and scrutiny’.

Key legislation and policy commitments

The Retained EU Law (Revocation and Reform) Act 2023

The Retained EU Law (Revocation and Reform) Bill was introduced in the UK Parliament on 22 September 2022 and received Royal Assent on 29 June 2023.

Retained EU law (“REUL”) is a category of domestic law applicable in the UK at present. REUL was created by taking a “snapshot” of EU law and rights that applied in the UK at the end of the implementation period on 31 December 2020. REUL was not fixed in time at 31 December 2020. As such, the REUL that is in force today is that snapshot (taken on 31 December 2020) as it has been amended by other domestic legislation since then.

The Retained EU Law (Revocation and Reform) Act 2023 (“REUL Act”) has four main effects:

“Sunsets” REUL listed in Schedule 1 on 31 December 2023 (i.e., the pieces of REUL listed in Schedule 1 will cease to be in force at the end of the year).

Gives powers to UK Ministers and Ministers in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland to enable them to amend, revoke and/or replace, and update pieces of REUL.

Changes the rules on how REUL is to be interpreted, by removing the principle of supremacy of EU law and other retained general principles of EU law by the end of December 2023, increasing the scope for UK courts to depart from retained EU case law, and downgrades the status of retained “direct” EU legislation, making it easier to amend and requiring it to be interpreted and applied consistently with domestic legislation.

Renames REUL which remains on the statute book after 31 December 2023 as “assimilated law”.

The REUL Act gives UK Ministers, Scottish Ministers and Ministers of the other devolved governments, extensive powers to make changes to REUL and assimilated law. UK Ministers are able to make changes to any REUL or assimilated law, including that within devolved areas. Scottish Ministers are only able to make changes to REUL within devolved areas.

These powers are granted to UK Ministers and devolved Ministers concurrently and jointly. ‘Concurrently’ means that they can be used either by a UK Minister or a devolved administration independently of each other in devolved areas. ‘Jointly’ means a UK Minister and a devolved administration acting together. The powers generally allow Ministers to change REUL or assimilated law by secondary legislation and are (with one exception in relation to the updating power) available until 23 June 2026. A SPICe blog on the REUL Act gives more detailed information on each of the main powers within the Act.

Scottish Government’s policy commitment to align with European Union law

Before EU exit, the UK as a member state (and Scotland as a nation of the UK) was required to comply with EU law in many areas. From 1 January 2021, the need to comply with EU law fell away. Scottish Ministers have, however, indicated that, where appropriate, they would like to see Scots Law continue to align with EU law.

As the CEEAC Committee guidance on post-EU scrutiny explains:

Scottish Ministers have a number of different options for securing that alignment. Part 1 (section 1(1)) of the UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Continuity) (Scotland) Act 2021 (the Continuity Act) confers a power on Scottish Ministers to allow them to make regulations with the effect of continuing to keep Scots law aligned with EU law in some areas of devolved policy. This is known as the “keeping pace” power. Scottish Ministers may also have existing powers in other Acts which would allow them to align Scots law with EU law. Primary legislation may also be used to introduce legislation with the purpose of keeping Scots law aligned with EU law.

The Continuity Act requires Scottish Ministers to report to the Parliament annually on the intended and actual use of the keeping pace power.

The CEEAC Committee has commissioned Dr Lisa Whitten to produce an EU law tracker and report which are provided twice each year (in January and September). Dr Whitten’s research highlights a number of case studies detailing instances of potential divergence and/or alignment between EU Law and Scots Law that have taken place during the reporting period. The first tracker and report were published in September 2023.

Challenges for the second half of Session six

The Scottish Parliament continues to evolve its practices to meet the scrutiny challenges of post-EU constitutional arrangements. The CEEAC Committee has taken a lead on this and, in September 2023, issued guidance on post-EU scrutiny to subject committees.

Finally, it’s likely that there will be interest in the Court of Session’s decision on the Petition of the Scottish Ministers for Judicial Review of the Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill (Prohibition on Submission for Royal Assent) Order 2023.

On 16 January 2023, the UK Government announced that the Secretary of State for Scotland, Alister Jack MP, was planning to make an Order under Section 35 of the Scotland Act 1998.

The Section 35 Order prevented the Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill, which the Scottish Parliament passed on 22 December 2022, from being submitted for Royal Assent. This was the first use of a Section 35 Order and SPICe produced an explainer on it.

The use of the Section 35 Order in relation to the Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill has been challenged by Scottish Ministers at the Court of Session. A separate section of this briefing looks at the Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill in more detail.

The unpredictable impact of geopolitical developments

Iain McIver, Senior Researcher, EU and International Affairs

Whilst foreign affairs and international relations are reserved matters, the impact of geopolitical events can influence devolved policy areas. An example of this is Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

At the time of the invasion Russia was a provider of a significant amount of Europe’s energy supplies whilst Ukraine was the source of much of Europe’s grain. In addition, Russia’s invasion led to the displacement of over 6 million people from Ukraine to other countries along with over 5 million people being internally displaced with Ukraine.

Whilst these issues are outwith the Scottish Government’s control, they have had an impact on the Scottish Government’s policy programme during Session 6.

Rising energy prices

A SPICe blog published in April 2022 set out the detail of the energy price rises, the impacts of these and the remedies proposed. Whilst energy prices had been rising during 2021 and the early part of 2022, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine exacerbated these issues. Sanctions placed on Russia meant the sale of Russian gas to Europe (including the UK) dried up leading to greater demand for the more limited supplies available. This led to volatility in gas prices and record wholesale prices.

The UK was particularly hit by the rise in wholesale gas prices as a result of its reliance on gas imports as explained by the April 2022 SPICe blog:

Whilst around 60% of Scotland’s total electricity generation and around 36% of the total for Great Britain’s market comes from renewable sources, the market is designed so that the wholesale cost reflects the price of the last unit of energy bought to balance the grid and to make sure there is enough to meet demand, which is predominantly gas. So even in energy markets such as GB’s, gas is still driving the wholesale electric price. And as the gas price has soared, so has the price of electricity.

According to the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit, up to February 2023 (a year after Russia’s invasion), the UK Government spent:

In the region of £60–70bn buying gas on wholesale markets in the 12 months since 24th February 2022, adding around £50–60bn of additional costs to the UK economy compared to before the gas crisis and pandemic.

The rise in gas prices leading to rising energy prices in the UK has affected both domestic and business customers. According to the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit, the increased cost in gas prices as a result of the Russian invasion cost the average household £1,000 on wholesale gas over the past 12 months (between March 2022 and February 2023), this is £800 more than in a typical year.

For UK businesses, the cost was estimated to be around £30 to £35 billion because of the increase in gas wholesale prices.

A further SPICe blog published in January 2023 explored the Energy price crisis and the current policy and outlook for 2023.

Rising food prices

Ukraine is often referred to as the “breadbasket of Europe” with more than 70% of the country made up of agricultural land. Ukraine’s main crops include sunflower, corn, soybeans, wheat and barley and it is a key food exporter around the world including to Europe and Africa. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine led to difficulties for Ukraine in producing, harvesting and exporting those crops. These factors have led to food shortages and rising food prices.

The Bank of England’s Chief Economist identified Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as being a key factor in the rise in food prices that the UK has experienced over the last eighteen months. Food price inflation peaked at 19.1% in March 2023, it had fallen to 10.1% in October 2023. According to Huw Pill, much of that inflation is as a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine which caused disruption to the supply chain of staples grown in Ukraine such as wheat and sunflower oil, and brought up costs of raw materials and basic food.

A King’s College London blog concluded that the Russian invasion of Ukraine was one of the reasons for food shortages and consequent rising prices across the world. Other reasons identified include bad weather affecting harvests in other countries and stockpiling by nations seeking to avoid the impact of those shortages:

On its own, the war in Ukraine has caused some food prices to rise. However, only when paired with other factors like bad weather and environmental changes resulting in poor harvests, and speculation and panic resulting in stockpiling does the war have a truly significant effect on food security.

Displaced persons from Ukraine

Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine resulted in millions of people being displaced, both within Ukraine and across Europe. In response to the unfolding humanitarian crisis, the UK Government established three visa schemes for displaced people from Ukraine:

a Family Scheme for those with family members in the UK

an Extension Scheme for those who held a valid UK visa on or after 1 January 2022

a Sponsorship Scheme through which displaced people from Ukraine are sponsored by hosts that offer them accommodation for at least six months. The Scottish Government acted as a supersponsor for the scheme but applications to the Scottish scheme have been paused since July 2022.

Whilst there are no figures for the total number of displaced persons from Ukraine who have come to Scotland, by 3 October 2023, 25,701 displaced people from Ukraine had arrived in the UK with a Scottish sponsor.

Seeking to move on from providing an emergency response to support displaced persons from Ukraine arriving in Scotland, on 27 September 2023, the Scottish Government published a strategy paper entitled ‘A Warm Scots Future’. The strategy, written in partnership with COSLA and the Scottish Refugee Council, “outlines the transition from an emergency response to Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine, to a long-term and holistic approach that supports the integration of displaced people from Ukraine.” SPICe has published a blog that summarises the Warm Scots Future strategy.

Conclusion

Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine early in 2022 has triggered a number of events which have impacted on devolved policy areas, or which have led to Scottish Government approaches such as the Ukraine supersponsor scheme.

Whilst more recent, the situation in the Middle East following the Hamas attack on Israel and the subsequent Israeli military action in Gaza could also potentially have impacts in devolved policy areas. The Scottish Government pledged an initial £500,000 towards the United Nations Relief and Works Agency’s (UNRWA) flash appeal in response to the ongoing escalation in the Gaza Strip. It then followed up with a further £250,000 to support displaced people in Gaza access food, water, shelter and medical supplies. The Scottish Parliament also called for a ceasefire following a debate on 21 November 2023.

As with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the situation in the Middle East creates instability across a number of countries. This instability has impacts far beyond just the countries directly affected and is an important factor when considering the environment in which Session 6 of the Scottish Parliament is taking place.

Inflation and the cost of living

Ross Burnside, Senior Researcher, Finance

One story that was perhaps not envisaged at the start of session 6, was the dramatic impact inflation would have on individuals, households and government spending.

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the world has seen steep increases in inflation, driven by high energy and food costs, and exacerbated by supply chain issues from a slowing Chinese economy.

Inflation impacts all aspects of life

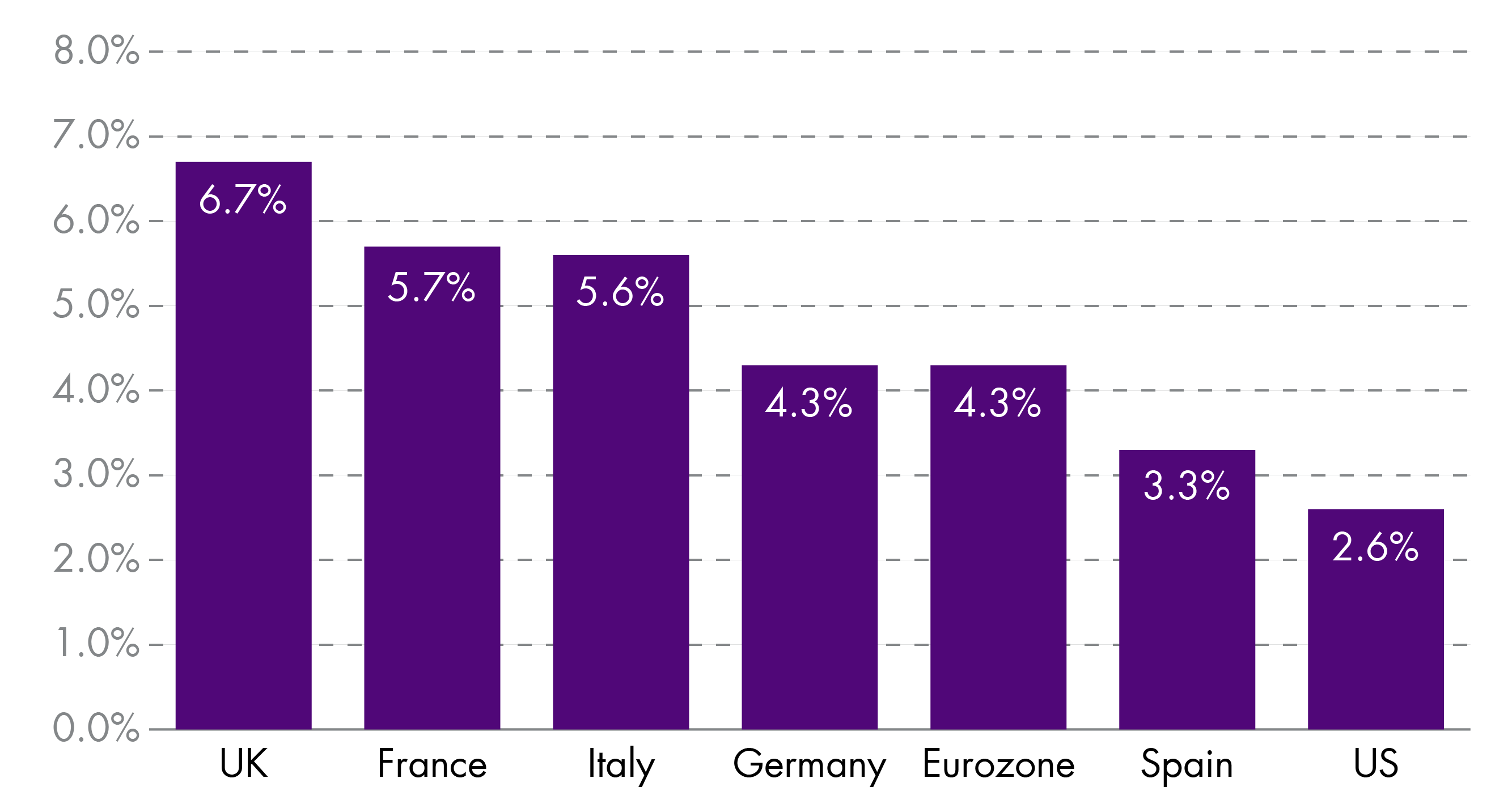

In the UK, the annual rate of inflation reached 11.1% in October 2022, a 41 year high. The UK economy has continued to see stubbornly high inflation well into 2023, with higher price increases than in several similar economies (see figure below).

What does high inflation mean for people?

High inflation impacts on the affordability of goods and services for individuals and households, and has contributed to the cost of living crisis so frequently referred to in recent times.

The main drivers of high inflation have been food and energy price increases in 2022 and 2023. Over the two years from September 2021 to September 2023 food prices increased by 28.4%. The House of Commons library point out that it previously took 13 years, from April 2008 to September 2023, for average food prices to rise by the same amount.

Energy prices have also increased, with household energy bills and road fuel costs increasing rapidly in 2022. Gas prices increased to record levels after Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022 and continued to rise in the remainder of 2022. Electricity prices, which are linked to gas prices also rose.

High inflation has resulted in the Bank of England taking monetary policy action to try to reduce the rate at which prices are growing. The Bank of England ‘Bank Rate’ has been increased from 0.1% in December 2021 and now sits at 5.25%. Increasing interest rates are designed to get the rate of inflation back to the Bank’s 2% target, but have knock on implications on borrowing costs for individuals and businesses as well as higher mortgage costs and prices in the rental market too.

What does high inflation mean for Government and the public finances?

Inflation also has significant impacts on public spending and both the UK and Scottish governments have taken measures to support individuals and households with rising costs. The UK government, for example, responded to increased domestic heating costs with the Energy Price Guarantee which capped the unit cost of energy for households. This policy is estimated to have costs of around £27 billion over the period 2022 to 2024.

To support people through the cost of living crisis the Scottish Government has provided a range of additional funding. Examples of financial support include increasing certain social security benefits by 6% instead of 3.1%, increasing the Scottish Child Payment, additional funding for benefit cap mitigation and the fuel insecurity fund.

There’s also been legislative change. Emergency legislation, the Cost of Living (Tenant Protection) Act 2022 introduced a rent increase cap for existing tenants and a pause on the enforcement of some evictions.

Perhaps the most notable Scottish budgetary impact has been in the realm of public sector pay. With the cost of living increasing to such a significant extent, public sector unions have pushed for higher than normal increases in paydeals. This has led the Scottish Government to offer significantly higher pay deals than had been planned for in the budget.

For example, the 2022-23 Scottish Budget was introduced in December 2021, prior to Russia invading Ukraine. At the time of its introduction, the Scottish Government was planning for the public sector paybill to increase by around 2-3%. However, faced with the prospect of widespread industrial action across the public sector workforce, improved pay deals had to be offered, thus increasing the share of the Budget comprising pay. At around £24 billion per year, the public sector paybill accounted for more than half of all resource spending. An in-year Emergency Budget Review resulted in the movement of around £1.2 billion from other Budget lines to fund improved public sector pay offers and cost of living interventions.

The higher pay deals agreed present challenges to subsequent budgets as these increases are baselined into future pay negotiations.

It is not only pay where inflation impacts arise. Inflation touches on all areas of public spending. For example, rising energy costs impact on the bills for heating schools, hospitals, libraries and all public buildings. Increases in the cost of raw materials and labour costs means that infrastructure spending goes less far than previously planned.

Inflation has arguably been the most significant story of this Parliamentary session to date, largely due to its impact on all areas of life. Inflation has eased from the peak of Autumn 2022 and stood at 4.6% in October 2023. It is to be hoped that inflation will continue to ease over the remainder of this Parliament. However, the ramifications of higher shares of the Budget being spent on pay will be felt on other areas of “unprotected” spend. This means that Scottish Government efforts in improving affordability, restraining unnecessary costs and reforming the public sector will become increasingly important in the second half of this Parliamentary session.

Reform of school qualifications

Ned Sharratt, Senior Researcher, Education

Education reform has been a constant within Scotland’s school education system for many years. Education reforms over the past decade or so have had a number of areas of focus. Central to most of this work is the process of ensuring that schools and teachers have the support, the structures, the capacity and the agency to enact the Curriculum for Excellence. Alongside this is a focus to reduce the poverty related attainment gap and to support pupils with additional support needs. This section of the briefing focuses on another area where reform has been considered, namely the suite of qualifications taken in schools, however, this issue sits in a wide range of work to improve the education system.

OECD Review

In 2021 the OECD published a review on the implementation of CfE, Scotland’s Curriculum for Excellence Into The Future. The purpose of the OECD’s work was to explore “how the curriculum is being designed and implemented in schools and to identify areas for improvement across the country.” The review had been commissioned by the Scottish Government in response to debates in Parliament where concerns were voiced around previous reforms had been implemented, particularly the introduction of National qualifications.

One of the issues that the OECD identified was a disconnect between Broad General Education (BGE) (education up to S3) and the Senior Phase (S4-S6). This disconnect was in relation to the focus on passing exams in Senior Phase in contrast to a broader educational focus in BGE. In 2021, the OECD also published a complementary analysis on ‘Upper-secondary education student assessment in Scotland’. The paper was authored by Professor Gordon Stobart and it compared Scotland’s system of certification in upper secondary to a variety of other countries’ systems. The paper noted that Scotland’s students are more frequently examined than in other jurisdictions and that the implementation of the reforms to the National Qualifications had not removed the ‘two-term dash’ – where in consecutive years there is compressed learning in the first two terms to prepare for exams after Easter.

Independent Review of Qualifications and Assessment (the Hayward Review)

Following the two OECD publications on Scottish Education in 2021, the Scottish Government commissioned Professor Louise Hayward to lead an Independent Review of Qualifications and Assessment. The review began its work in early 2022 and through 2022 and 2023 undertook a number of phases of consultation. Its final report was published in June 2022.

Some of the key recommendations in the report are:

Adopting an SDA (Scottish Diploma of Achievement) as a graduation certificate.

Removing exams in all subjects up to SCQF level 5 (e.g. National 5s), examinations may be retained in levels 6 and 7 (e.g. Highers and Advanced Highers).

A digital profile for all learners which allows them to record personal achievements, identify and plan future learning.

The Review recommended that the SDA be made up of three, equally weighted parts. These are set out in the box below.

Programmes of Learning

“In-depth study of individual areas of the curriculum, subjects and vocational, technical and professional qualifications, will remain a fundamental part of qualifications. However, the new approach to qualifications should go further to improve alignment with CfE."

Project Learning

“Learners should have opportunities to demonstrate how they can use knowledge from across subjects/technical and professional areas to tackle challenges. These kinds of experience are closer to those learners will have beyond school or college, for example being able to work as part of a team, to investigate, to solve problems and to look for creative solutions."

Personal Pathway

“Learners are individuals and should have opportunities to demonstrate their individuality- the courses they choose, the projects they undertake, their interests, their contributions and aptitudes. Together, these combine to help learners make good decisions about what they might do next. This wider, more personalised information will provide colleges, employers and universities with a better evidence base to inform their decisions about which students or employees are likely to be best suited to which course or job.”

When giving evidence to the Education, Children and Young People Committee in September 2023, Professor Hayward said that the vision for the future of qualifications and assessment in Scotland is a crucial part of this work. The proposed vision is for:

an inclusive and highly regarded Qualifications and Assessment system that inspires learning, values the diverse achievements of every learner in Scotland and supports all learners into the next phase of their lives, socially, culturally and economically.

Professor Hayward also stated that the report provides a “longer-term direction of travel for qualifications and assessment in Scotland”.

Response to the Review

The review was welcomed in some quarters. EIS highlighted that the approach suggested by the Independent Review of Qualifications and Assessment would need additional resource to be successfully implemented, the EIS stated:

We need bold and innovative change to deliver a qualifications system that best meets the needs of young people, from all backgrounds, in schools and colleges across Scotland. Recommendations to reduce the emphasis on high-stakes exams, place a greater emphasis on continuous assessment, and provide space for greater breadth, depth, and enjoyment of learning across all areas of the curriculum, can deliver positive change for all of Scotland’s young people.

Other commentators were less enthusiastic (see for example, this Blog by Professor Lindsay Paterson).

In her statement to Parliament on 22 June, the Cabinet Secretary, Jenny Gilruth said that she would, in respect of the Hayward Review, seek further views from teachers and to consider the response in the context of wider education reform. Ms Gilruth gave a further update on 7 November 2023 when she said:

Since the conclusion of the Hayward review in June, I have been seeking views on the recommendations pertaining to the national qualifications. We undertook a survey with teachers and lecturers on the report, which received more than 2,000 responses. Although agreement on the need for change was clear, there were varying views on next steps, and on the perceived appetite for radical reform.

In that context, I cannot ignore the challenges that our schools are currently responding to, and I must balance that reality with any reform of our qualifications system. With that in mind, I propose—subject to parliamentary agreement—to return to the chamber in the new year to debate the proposals fully. In the meantime, I will engage with Opposition spokespeople on the next steps, to ensure that we use any parliamentary debate to encourage greater support for political consensus.

Whether the Scottish Government chooses to take forward the recommendations of the Independent Review of Qualifications and Assessment wholesale, in part, or not at all, it will be a significant decision which will affect secondary education for many years to come.

Increasing public participation in the Scottish Parliament

Ailsa Burn-Murdoch, Senior Researcher, Public Participation

Citizen Participation has been a growing theme in democratic practice in recent years, to the extent that it has now become an area of scrutiny, as well as a growing area of practice, so this section includes a brief overview which builds on a briefing published in February 2022.

Public participation in the Scottish Parliament

The Commission on Parliamentary Reform, in 2017, highlighted the importance of engaging the public in parliamentary processes and recommended that “The Parliament should establish a dedicated team whose main purpose is to support (and challenge) committees to undertake more innovative and meaningful engagement”.

The Committee Engagement Unit was formed soon afterwards and became the Participation and Communities Team at the start of Session 6, which coincided with the name and remit of the Public Petitions Committee being expanded to include Citizen Participation.

In parallel, the Scottish Parliament Corporate Body’s Strategic Plan for Session 6 includes a commitment to “embedding deliberative democracy in the work of the Parliament”.

Since the development of specialised services to support participation in the Scottish Parliament, several high-profile engagement and deliberative activities have taken place. This has included citizens’ panels on primary care (2019) and Covid-19 (2021), and a citizens’ jury on land management (2019).

Scottish Government

The Scottish Government has been on a similar path, having convened the first National Citizens’ Assembly in Scotland in 2019 and Scotland’s Climate Assembly in 2020-21. It set up a Working Group in summer 2021 to make recommendations to Ministers on “institutionalising participatory and deliberative democracy”, which reported in March 2022. It recommended that the Scottish Government “Connect to the Scottish Parliament Committee system for scrutiny of Citizens’ Assembly processes and recommendations”.

The Scottish Government responded in March 2023, confirming that it would adopt the values, principles and standards for institutionalising participatory and deliberative democracy in Scotland and, in time, establish a team which is multi-disciplinary and practice led with overall responsibility for Participation. It also said that “During this Parliament, consideration will be given to how government can best set in place longer term resourcing that delivers a clear programme of Citizens' Assemblies”.

The Scottish Government has also set out its commitment to advancing its approach to human rights budgeting, a core principle of which is participation (along with accountability and transparency). It is expected that emphasis on these principles will increase as the Government progresses forthcoming human rights legislation.

Citizen Participation and Public Petitions Committee inquiry into public participation

In February 2022, the Citizen Participation and Public Petitions Committee agreed to launch an inquiry into Public Participation in the work of the Scottish Parliament. As part of this, it asked a group of 19 randomly selected people from across Scotland, who were broadly representative of Scotland’s population, to come together as a Citizens’ Panel to answer the question “How can the Scottish Parliament ensure that diverse voices and communities from all parts of Scotland influence our work?”.SPICe acknowledged at the time that an inward-looking scrutiny focus was novel in the Scottish Parliament.

The panel came up with 17 recommendations in December 2022, and the Committee took further evidence around these recommendations, which SPICe supported by looking at examples of practice similar to the Panel’s suggestions, and deliberative processes in other legislatures.

Political support for deliberative democracy

The Committee set out its vision for embedding deliberative democracy in the work of the Scottish Parliament in its final report in September 2023, agreeing to the majority of the panel’s recommendations, at least in principle. Most significantly, the Committee concluded that the Parliament should use Citizens’ Panels more regularly to help committees with scrutiny work, and made several recommendations for pilot and preparatory work, with certain guiding principles. The expectation is that, by the end of Session 6, the Committee will recommend a model that the Parliament can use after the 2026 election. The Committee concluded:

That deliberative democracy should complement the existing model of representative democracy and be used to support the scrutiny process.

That the way in which deliberative methods are used, from recruitment through to reporting and feedback, should be transparent and subject to a governance and accountability framework.

That the deliberative methods used should be proportionate and relevant to the topic, and the scrutiny context.

That participants in deliberative democracy should be supported, empowered and given feedback on how their recommendations are used.

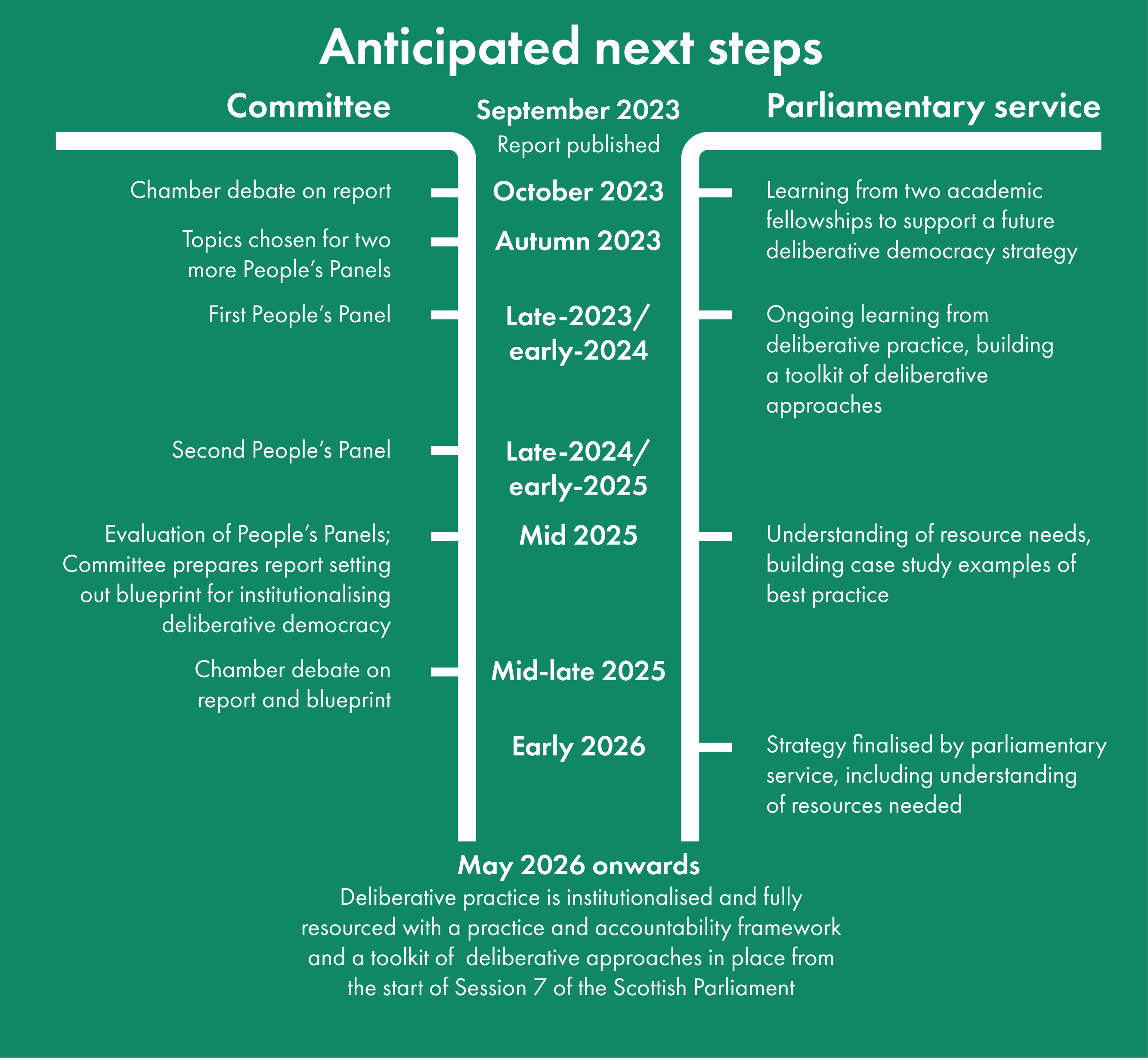

The Committee’s anticipated timeline for implementation of its recommendations is set out in the following infographic:

A debate in the Chamber on the Committee’s report on 26 October showed that the panel process and recommendations have been well received, with strong cross-party support and willingness across parties, and the Scottish Government, to work together in meeting the Committee’s aspirations. Members of the Parliament agreed unanimously to endorse the Committee’s report and recommendations.

Implementation of Committee recommendations

Work is now underway to build on practice expertise and pilot approaches. The first of the two people’s panel pilots commissioned by the Committee will focus on post-legislative scrutiny of the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009. This, and a subsequent panel on an area of public interest in late 2024-early 2025, will provide an opportunity to test emerging practice principles.

Scrutiny of participation

In the meantime, Committees have also begun to increase scrutiny of the Scottish Government’s use of participation. Both the Citizen Participation and Public Petitions Committee and the Equality, Human Rights and Civil Justice Committee included a focus on participation within their 2024-25 pre-budget scrutiny. The latter did so by asking members of an existing citizens’ panel to engage in a deliberative process and come up with questions for the Scottish Government.

As participation in democracy becomes an increasing area of focus and interest, it is likely that it will be an increasing area of Parliamentary activity, in terms of both practice, and scrutiny of Scottish Government activities.

The Promise: Care system reform

Lynne Currie, Senior Researcher, Children’s social work, child protection and adoption

‘The promise’ is the commitment made to children and young people in Scotland’s care system to reform the system and address stigma and inequality of outcomes faced by care experienced people by 2030. The goal of ‘the promise’ is for all children and young people in Scotland to grow up loved, safe and respected.

The Independent Care Review

Moves to reform Scotland’s care system began in the last session of Parliament. The Independent Care Review was commissioned in February 2017 by then-First Minister Nicola Sturgeon MSP. This followed calls from Who Cares? Scotland for a ‘root and branch review’ addressing stigma and inequality of outcomes faced by care experienced people.

People with experience of the care system represented half of the review group’s co-chairs and working group members. During the lifetime of the review, the views of over 5,500 care experienced children and adults, as well as parents, carers and the care workforce, were listened to.

The review findings were published in February 2020, setting out steps Scotland can take to embed significant change to the care system. The main findings were set out in The Promise, alongside the Pinky Promise for younger readers.

The Promise set out a vision for a Scotland where all children grow up loved, safe and respected. This vision is built on five foundations:

Voice: Children must be listened to and involved in decisions about their care.

Family: Children feel loved and safe in their families and families are given the support they need.

Care: Children must not be separated from their brothers and sisters wherever possible. Legislation to help siblings in care stay together has since come into force in July 2021.

People: Care experienced children must be supported to develop relationships.

Scaffolding: Children, families and the workforce must be supported by an accountable system that provides help and support when required.

Responding to the publication of the review report, the then-First Minister said in a statement to the Scottish Parliament on 5 February 2020:

We will work with local authorities, care providers and all other relevant partners to make the necessary changes to care. We will deliver that change as quickly and as safely as possible - and starting now. And we will ensure that people with care experience remain at the heart of the process.

Implementing the recommendations

Following publication of the recommendations, The Promise Scotland was set up by Scottish Ministers as an independent organisation.

The Promise Scotland does not hold statutory powers or responsibilities; its role is to oversee, drive and support reform by 2030. It works with organisations and individuals all over Scotland to help others deliver change for care experienced children and young people.

Plan 21-24 sets out the initial steps of care reform. The Promise Oversight Board reviews progress annually.

The Scottish Government published its Promise implementation plan in March 2022. This sets out the Scottish Government’s actions and commitments on care reform.

Minister for Children, Young People and Keeping the Promise, Natalie Don MSP, currently has responsibility for overseeing progress on care reform.

Progress so far

Actions toward achieving the vision set out in the Independent Care Review in the three years following its publication include:

Legislation to help siblings in care stay together came into force in July 2021. This is set out in the Children (Scotland) Act 2020.

The 2021-22 Programme for Government (PfG) committed to a Whole Family Wellbeing Fund of £500m over Session 6 of Parliament. This is aimed at tackling issues faced by families before they need crisis intervention. The PfG also stated that from 2030, at least 5% of community-based health and social care spend will be focused on preventative measures. The overall intention of this preventative spend is to reduce the number of children being taken into care.

The Hearings System Working Group (HSWG) facilitated by The Promise Scotland published its redesign report in June this year. The Scottish Government response is expected by the end of the year.

The Children (Care and Justice) (Scotland) Bill is currently making its way through Parliament. If passed, this will raise the age of referral to the Children’s Hearings System from 16 to 18 and end the placement of 16- and 17-year-olds in young offenders’ institutions.

The introduction of a Scottish Recommended Rate of allowance for foster and kinship carers was announced in August this year. Local authorities are at various stages of implementing this.

The Scottish Government has launched a consultation on introducing a Care Leaver Payment. This is a proposed one-off payment of £2,000 for those leaving care.

The Promise Oversight Board’s latest progress report published in June 2023 concluded that delivering Plan 21-24 will be challenging:

Sadly, due to the worsening circumstances for so many and the current pace of change, the Promise Oversight Board does not believe that delivering the original aims of Plan 21- 24 is realistic within its given timeframe.

However, 2030 remains the date by which the promise must be kept and if everyone plays their part over the next seven years, this is still achievable.” – Promise Oversight Board, Report Two, June 2023

The report calls for “leadership and drive” from the Scottish Government and scrutiny bodies to put in place clear “principles, outcomes and milestones that will guarantee the promise”.

It also states the Scottish Government should set out an investment plan to deliver the change.

Recent developments: Programme for Government 2023-24

In his statement to Parliament on the 2023-24 Programme for Government (PfG), First Minister Humza Yousaf MSP announced he would chair a Cabinet sub-committee on The Promise to enable cross-portfolio change.

In response to a subsequent Parliamentary Question asking for further detail on meetings and membership of the Cabinet sub-committee the Scottish Government stated that the first meeting would take place when the membership and remit of the group was confirmed.

A Promise Bill is expected before the end of this Parliamentary session. This will include legislation relating to the redesign of the Children’s Hearings System and any other legislative changes required to implement reforms.

Just Transition

Rob Watts, Senior Researcher, Economy

The transition to net zero has been an overarching focus for policy in Session 6 and is discussed in other sections of this briefing. This section focuses on what the transition means for the Scottish economy and key industries that will be affected.

The transition will involve structural changes to the economy that will have significant impacts on communities and industries across Scotland. Managing these changes in a way that spreads the benefits and risks equitably is a key challenge for policy makers. In general terms, this is referred to by the Scottish Government as delivering a “just transition”.

What is a “just transition”?

The concept of a just transition encompasses a range of policy areas and industries in the economy. Issues around energy, agriculture and land use, transport, housing and construction are all relevant to the transition to net zero and whether this happens in a ‘just’ fashion. Decisions around skills, planning and infrastructure investment will all have a bearing on how successful the transition to net zero is, and these are taken by different layers of government.

An obvious example is what will happen in the energy sector, as industry and jobs transition from fossil fuels to renewables, and whether this transition can be managed in a way that is ‘fair’ or ‘just’ to those most affected.

But a just transition also touches on other industries and policy issues. In transport, for example, the Scottish Government has a target to reduce road vehicle mileage by 20% by 2030. How this can be done in a ‘fair’ way that protects those on the lowest incomes and those most reliant on car usage is a key challenge for policy makers. It raises questions about the accessibility and affordability of public transport, and how the use of roads is taxed.

In construction, significant changes to the way buildings are built and heated will be required to meet statutory emissions reduction targets. How the Scottish Government and stakeholders can ensure the workforce has the correct skills to deliver this and that opportunities to re-skill or up-skill are open to all those who could benefit, are questions that surround the idea of a just transition.

A key aspect of this is defining what a just transition is and how the extent to which it has been delivered can be measured.

Scottish Government Just Transition Plans

The Scottish Government has published a draft Energy Strategy and Just Transition Plan.

The Scottish Government has also published three discussion papers ahead of the forthcoming publication of three sectoral plans – one each for agriculture and land use, the built environment and construction, and transport. A key commitment in these just transition plans is co-design with those most affected by the transition to net zero.

It will also publish a place-based just transition plan for the Grangemouth industrial cluster.

The cluster is a significant employer in the region and accounts for around a third of total emissions from companies in Scotland who have a mandatory reporting duty (some large businesses are required to report on climate-related financial risk). The Scottish Government aims to reduce industry emissions by 43% between 2018 and 2032.

The Economy and Fair Work Committee conducted an inquiry into a Just Transition for Grangemouth and reported in June 2023.

The Just Transition Fund

The Bute House Agreement commits to a 10-year £500 million Just Transition Fund for the North East and Moray. The stated aim of this Fund is to “identify key projects, through co-design with those impacted by the transition to Net Zero, to accelerate the development of a transformed and decarbonised economy in the North East and Moray.” The first year of funding was allocated in 2022-23 and it has been announced that the Scottish National Investment Bank will play a role in allocating funds, in line with its remit over the transition to net zero.

Currently, the North East and Moray’s industrial base has relatively high emissions intensity. Across Aberdeen, Aberdeenshire and Moray, industry accounts for 890 Kt CO2 emissions (25.5% of emissions from the region). However, these industries also generate significant economic activity and energy supply. Scotland gets 79% of its energy from oil and gas and the sector supports 65,000 jobs in the North East and Moray. In 2019, oil and gas were responsible for gross value added (GVA) of £16 billion (around 9% of Scottish GDP).

The Economy and Fair Work Committee are currently conducting an inquiry into a Just Transition for the North East and Moray.

The Just Transition Commission

The Just Transition Commission has been established to provide an independent advisory and scrutiny role of Scottish Government policy around a just transition. It recently published three briefings ahead of the Scottish Government’s forthcoming just transition plans. These produced a series of recommendations for government.

The first briefing focused on transport, and in particular, the Scottish Government’s target to reduce car mileage by 20% by 2030 and the justice considerations of this.

The second was centred around land use and agriculture. It focused on the communication of major changes to land managers, communities and impacted groups.

The third briefing on the built environment and construction discussed how a new workforce can be delivered for retrofitting existing buildings.

Members of the Just Transition Commission appeared at a recent seminar for Scotland's Futures Forum.

Health and social care integration

Anne Jepson, Senior Researcher, Health and Social Care

The Key Issues briefing for Session 6 outlined progress on the integration of health and social care through Session 5, as well as the impact of the pandemic on public understanding of social care in relation to the NHS. Focus and action followed the pandemic with the Independent Review of Adult Social Care (IRASC), published in January 2021.

Prior to the Parliamentary Session’s first Programme for Government, the Scottish Government launched a consultation for a national care service in August 2021, which picked up on some of the recommendations from IRASC. In July 2022, the Scottish Government established a Social Covenant Steering Group.

The first Programme for Government (PfG) 2021-22, reflected on the contribution of the care sector and spoke in terms of ‘reforms which start with people and places, rather than services.’ The commitment to bring forward the legislation for a national care service (NCS) was made. The PfG stated that the Scottish Government would ‘take forward the biggest reform of health and social care since the founding of the NHS’. The NCS would:

Address the human rights and needs of people needing care and support

Provide national accountability

Embed ethical commissioning with minimum standards for procurement decisions

Support Fair Work commitments including collective national negotiating for workers’ terms and conditions and representation for workforce and trade union representation in its governance

Bring terms and conditions of nursing staff working in care in line with those in the NHS.

In addition, options to remove non-residential care charging were to be developed, actions to increase early intervention and prevention and a national induction programme for new entrants to adult social care would be developed by end of Spring 2022.

The National Care Service

The National Care Service (NCS) Bill was introduced on 20 June 2022. It is fair to say it has had a bumpy ride so far. A series of blogs have followed progress of the Bill, collated within a SPICe spotlight NCS hub. The Bill is framework in nature, leaving many key elements to secondary legislation and co-design. A number of committees have engaged in Stage 1 scrutiny, and the understanding of what co-design is and entails has dogged a number of committee meetings.

In the PfG for 2022-23, the need to focus on prevention (of admission to hospital) and early intervention was reiterated, referring to community health and social care. The tone for the legislation was slightly less ambitious, but the PfG stated that the Bill would “pave the way for more integrated and person-centred care, ending the postcode lottery of care that exists across Scotland under the current system.” There was a commitment to deliver a £10.50 minimum wage for all adult social care staff in commissioned services, through £200 million of funding to local authorities.

In the 2023-24 PfG, the Scottish Government announced an increase in the hourly rate for care staff to £12 per hour, but this will not be introduced until April 2024. Mechanisms to support national wage bargaining are not in the Bill, although discussions are ongoing about sectoral bargaining. Given that over 75% of care is provided by independent providers and many small, ununionized employers, national wage bargaining will be a challenge for the realisation of this commitment.

The bumpy ride

Under the original plan, it was agreed by Parliament on 5 October 2022 (prior to any evidence being taken) that Stage 1 would be completed by 17 March 2023.

On 8 March 2023 Parliament agreed that Stage 1 would be extended to 30 June 2023. On 7 June 2023, after the Minister for Social Care, Mental Wellbeing and Sport, Maree Todd, had written to, and been in front of, the Committee on 9 May, the Parliament agreed that Stage 1 consideration would be extended to 31 January 2024.

In the Bill as introduced, legal accountability was to move to the Scottish Government, away from local authorities. However, while this pleased some stakeholders, COSLA and the unions were not happy. It was unclear what this change would mean for local authority staff, social work services, including justice and children’s services, and also what it would mean for integration joint boards (and for the Public Bodies (Joint Working)(Scotland) Act 2014).

The postponement of Stage 1 was to allow for further engagement by the Scottish Government over the summer of 2023. The Scottish Government and COSLA reached agreement, in July 2023, that accountability would be shared between government, the NHS and local authorities.

The opposition to the Bill from a wide range of stakeholders, was acknowledged by the Minister for Social Care, Mental Wellbeing and Sport (Maree Todd) on 3 October 2023:

We paused and then worked very hard with partners, local government, trade unions and people with lived experience to try to find a way forward. You will be aware that we were pretty much in a situation in which we could not move forward because the level of opposition to the bill was so great.

However, additional scrutiny carried out in the autumn of 2023 suggests that key stakeholders remain unclear about the structures, governance and legal accountability that a national care service will entail. Many stakeholders are now unclear as to how a national care service will be different from the status quo.

Non-residential social care charging

There is nothing in the Bill about removing non-residential social care charging. Charging for social care is a complex area. It is not clear whether the commitment was to remove charging for all non-residential social care support or just those that are not subject to a financial assessment – that is: day care meals, alarms and alarm monitoring, day care centres and transport. Currently, free personal care and nursing care are free to everyone assessed as needing it. Assessing need is a statutory duty of local authorities. They use national eligibility criteria. Many people have to contribute to or fully fund care and support they need. The level of unmet need is not known.

The PfG 2023-24 reflects some of the issues described above, and the changes made to the plans for a national care service in terms of accountability, and made reference to further engagement over the summer of 2023. Mention of integration has returned to the narrative, but also highlighted is the view of social care as a way to ease pressure on the NHS, potentially undermining the parity between health (the NHS) and social care support (the NCS) that heralded the announcement of the National Care Service.

We are working towards the introduction of a National Care Service so that everyone has access to consistently high quality social care, whenever they need it. Getting this right will remove barriers, tackle inequalities and allow people to flourish by living independent lives in communities of their choice. It will also ease pressure on our NHS and continue the integration of community health and social care support.

Mental health and COVID-19

Lizzy Burgess, Senior Researcher, Health and Social Care

The Key Issues for Session 6 briefing outlined the impact the COVID-19 pandemic and associated restrictions had on the mental wellbeing of people in Scotland. It also looked at some of the actions taken by the Scottish Government to address these, such as the Mental Health Transition and Recovery Plan, which set out a wide range of actions aimed to address some of the impacts on mental health arising from the pandemic. Audit Scotland has said that the plan did not outline timescales for all the actions and the Scottish Government has not carried out a review of progress towards meeting the plan’s objectives (September 2023).

This briefing provides an update on the current level of demand for mental health services, outlines recent policy developments and discusses potential legislative changes.

Demand for services

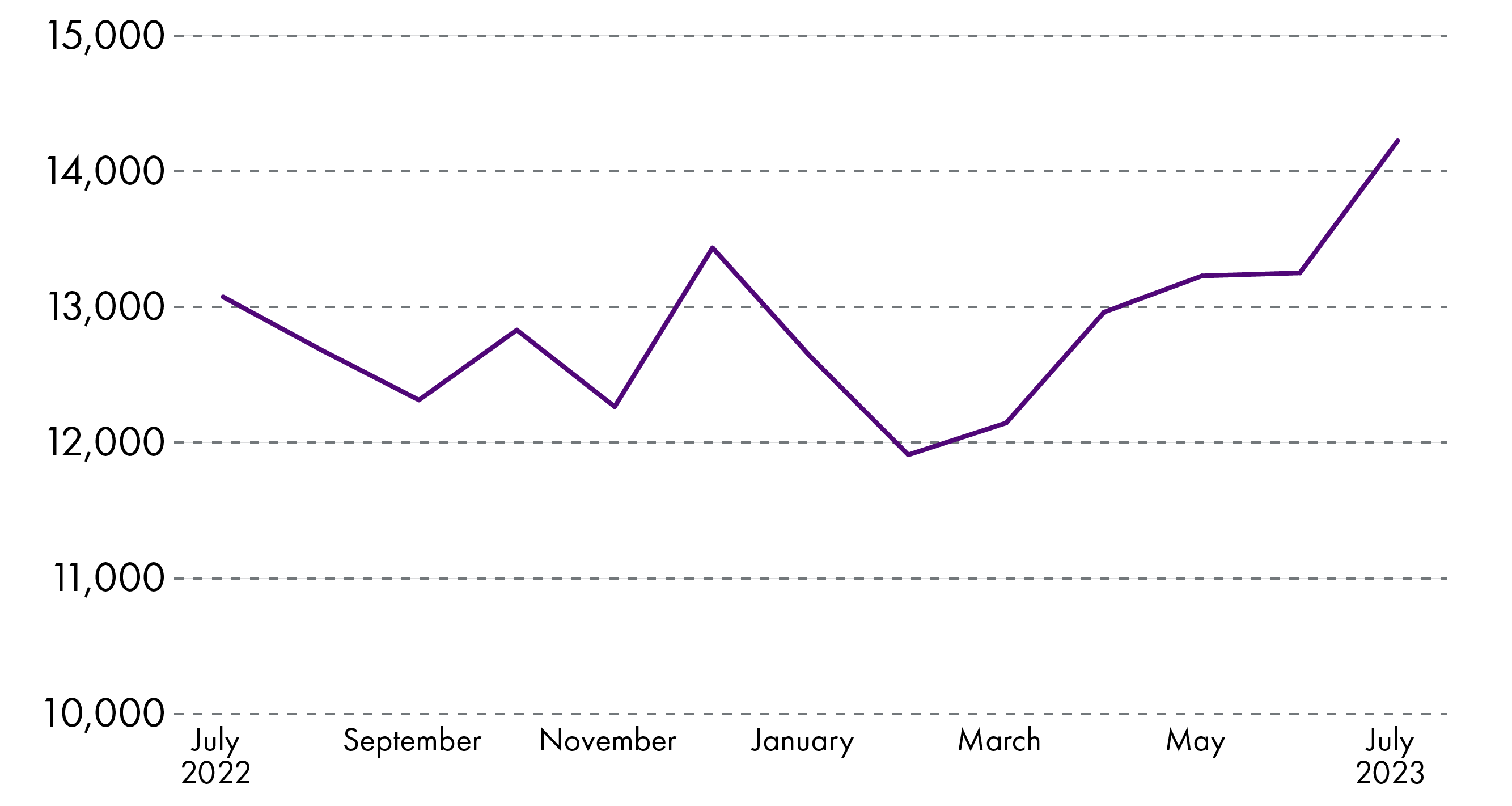

Following the COVID-19 pandemic, demand for mental health services remains high. In July 2023, NHS 24 reported that its mental health service Breathing Space had its busiest month on record, with 14,225 calls offered to service.

Mental health services are still unable to meet the Scottish Government standard that 90% of people should start their treatment within 18 weeks of referral to psychological therapies. For the quarter ending June 2023, 78.8% of people started their treatment within 18 weeks, compared to 80.0% of people for the previous quarter, and 81.6% of people for the quarter ending June 2022.

A similar picture is seen in Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) waiting times. In the quarter ending June 2023, 73.8% of children and young people were seen within 18 weeks, which is a decrease from 74.2% for the previous quarter but an increase from the 68.3% for the same quarter ending June 2022.

Public Health Scotland has started to publish quality indicators for Mental Health. This pulls together 19 of the 30 quality indicators included in the Quality Indicator Profile for Mental Health, from the Mental Health Strategy 2017-2027 (Action 38).

The Auditor General for Scotland and the Accounts Commission has recently carried out a performance update on Adult Mental Health. This noted that information about demand for mental healthcare only covers people already accessing, or trying to access, some mental health services. It does not reflect levels of unmet need. However, it goes on to state that there are indications that demand for mental health treatment has increased.

Accessing services

The performance update on Adult Mental Health also found that accessing adult mental health services in Scotland remains slow and complicated for many people.

In particular, ethnic minority groups, people living in rural areas and those in poverty all face additional barriers.

The report included many recommendations for the Scottish Government, Integration Joint Boards, Health and Social Care Partnerships and NHS boards. The Public Audit Committee is currently considering the report.

Mental health policy

Since 2020 there have been some developments in the Mental Health policy landscape. In relation to CAMHS, in February 2020, the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) NHS Scotland national service specification was published. This sets out the provisions young people and their families can expect from the NHS in Scotland. In September 2023, the Children and Young People’s Mental Health and Wellbeing Joint Delivery Board published its final report. This made nine strategic recommendations.

In June 2023, the Scottish Government and COSLA published a new mental health and wellbeing strategy. This was followed by a delivery plan and Mental Health and Wellbeing Workforce Action Plan.

The Scottish Government’s new mental health and wellbeing strategy states:

Our vision is of a Scotland, free from stigma and inequality, where everyone fulfils their right to achieve the best mental health and wellbeing possible.

This is similar to, but has a few key differences, to the vision set out in the 2017 -2027 strategy which was:

Our vision for the Mental Health Strategy is of a Scotland where people can get the right help at the right time, expect recovery, and fully enjoy their rights, free from discrimination and stigma.

An outcomes framework has been developed to help monitor and evaluate progress towards achieving the vision.

Mental health legislation

The Scottish Mental Health Law Review published its final report in September 2022. The review suggested over 200 proposals for reform. This review followed two earlier independent reviews the Independent Forensic Mental Health Review (February 2021) and the Independent Review of Learning Disability and Autism in the Mental Health Act (December 2019).

The Scottish Government responded to the Mental Health Law Review in June 2023.