Economic, social and cultural rights and the proposed Human Rights Bill

The Scottish Government has proposed a new Human Rights Bill to protect a range of economic, social and cultural rights in Scotland. This briefing, which includes input from various SPICe researchers, outlines the current human rights framework in Scotland and explains what would change under the Scottish Government's proposals.

Summary

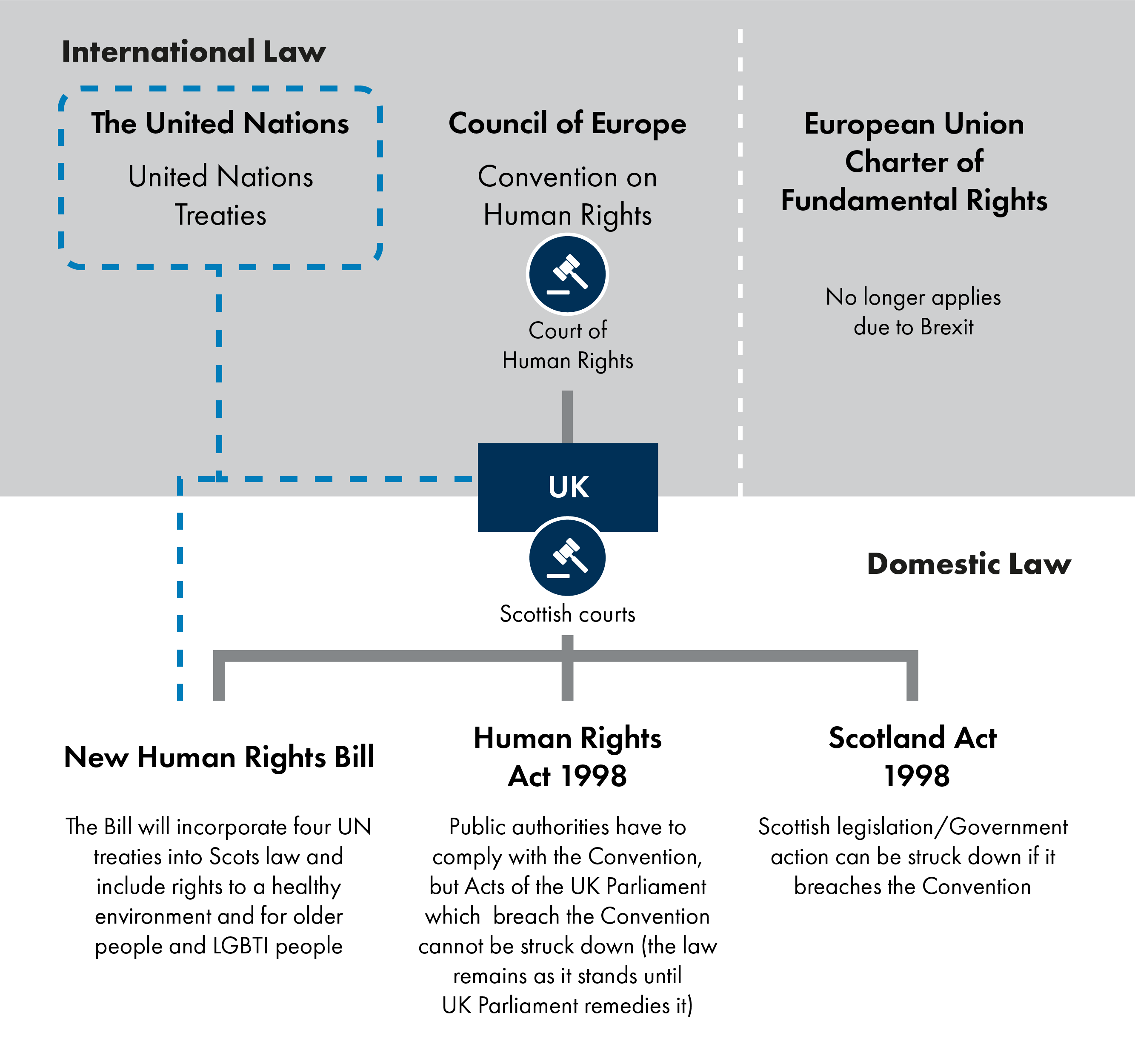

In the UK, human rights law is centred around the Human Rights Act 1998. It brought the rights in the European Convention on Human Rights (Convention) into UK law and was also an integral part of the devolution settlement. As a result, people can rely directly on the Convention in the UK, for example by bringing cases against public bodies arguing that their rights have been breached.

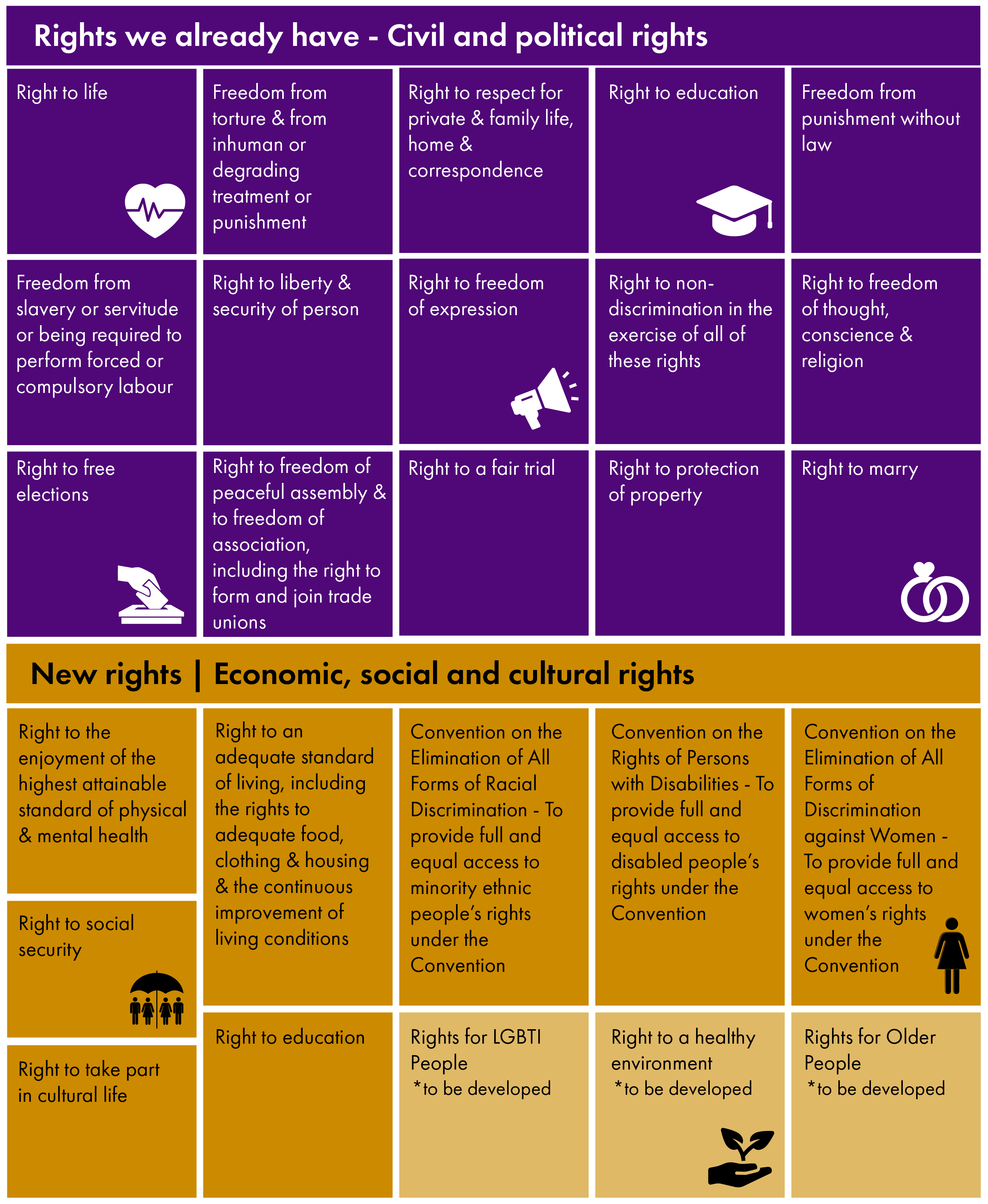

The Convention mainly protects civil and political rights, such as the right to life, right to liberty and freedom of speech. It has less importance for what are known as "economic, social and cultural rights", i.e. the right to health, housing, social security etc.

The UK has signed up to various international treaties on economic, social and cultural rights, in particular UN treaties. However, there is no equivalent to the Human Rights Act which brings these rights en masse into UK law.

Since international treaties aren't part of UK law until put into legislation, the result is that the economic, social and cultural rights rights in these treaties have less protection than the civil and political rights in the Convention.

For some time, there have been arguments in Scotland that the economic, social and cultural rights in UN treaties should also be incorporated into domestic law.

Following on from the work of two advisory groups, in 2021 the Scottish Government proposed a new Human Rights Bill in this parliamentary session aimed at addressing this issue.

The Bill would incorporate into Scots law the UN's International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, as well as three UN treaties on race (CERD), women (CEDAW) and disability (CRPD). It would also include environmental rights, rights for older people, and an equality clause including provision for LGBTI people.

Although much will depend on the details, the Bill would bring about a major change to the human rights landscape in Scotland.

In the first place, it would mean that a wide range of economic, social and cultural rights could be directly relied on by people in Scotland (for example, in cases against public bodies) instead of being primarily matters for international law, politics and diplomacy.

Given the range of rights protected by these UN treaties, and the additional rights proposed, there would be an impact on numerous areas of policy, including environmental policy, equality policy, housing, health, and education.

The actual impact of the Bill in each policy area will depend to a large degree on the priority which each area is given in the Scottish Government's budget, rather than on the nature of the right itself. Budgets and budget scrutiny will therefore be crucial.

The Bill will also have an impact on the courts and court procedures as the proposals argue that current rules on judicial review need to be strengthened and that barriers to access to justice need to be removed so that people have effective remedies to enforce their rights.

Elements of the Bill are likely to be controversial as there is a long-standing debate about the degree to which economic, social and cultural rights should be given the same legal protection in national law as civil and political rights. In addition, depending on its scope, questions could arise around devolved competence in certain areas of the Bill.

An overview follows of the current human rights framework in Scotland, what would change under the Scottish Government's proposals, and some of the high level issues which are likely to be relevant.

Human rights - the current system in Scotland

As the Scottish Government's plans involve a major change to the status quo, it's worth first briefly looking at the different types of human rights and how they are currently protected in Scotland.

Human rights

In very simple terms, human rights are the fundamental legal protections and rights which apply to all human beings. They have their origins in the enlightenment and the emergence of liberal democracy.1

Many of the most important legal sources can be found in international treaties drafted in the aftermath of World War II. For example, by the United Nations or the Council of Europe - a non EU organisation with 47 member states including the UK.

In addition, national laws also protect human rights - either in order to comply with treaties or based purely on domestic law and policy.

The courts have a key role in interpreting and developing these rules and, as a result, court cases can be crucial in establishing the scope of people's rights.

The legal framework is, however, only one aspect of the system. In practice, the way in which people are able to exercise their rights is heavily dependent on government budgets and policies and the workings of individual organisations.

For further details see the SPICe Briefing - Equalities and Human Rights: Subject Profile.

Civil and political rights and economic, social and cultural rights: main sources

Most people will have some knowledge of what are known as "civil and political rights". These are aimed at the ‘personal integrity’ or ‘freedom’ of an individual and include rights such as the right to life, right to liberty, freedom of speech or the right to a fair trial.

The main protections for civil and political rights at UN level can be found in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and in Europe through the Council of Europe's European Convention on Human Rights.

However, there is also a whole range of what are known as "economic, social and cultural rights" (ESC rights). These are more focused on the economic, social and cultural needs of individuals. They are part of the political debate about the appropriate role of the state in addressing issues such as poverty, homelessness, unemployment, poor working conditions, inequality etc.

The main UN treaty protecting ESC rights is the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) which came into force on 3 January 1976. It covers rights such as the right to social security, the right to an adequate standard of living, the right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, and the right to education.

There are also UN treaties which protect the rights of certain groups, for example:

The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW)

The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD)

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD).

The European Social Charter, a Council of Europe treaty which is aimed at similar rights to ICESCR, is the main treaty on ESC rights in Europe.

ESC rights are also protected at EU level. The main source is the EU's Charter of Fundamental Rights. It applies to EU institutions, and Member States when acting within the scope of EU law, but is no longer a source of law in the UK as a result of Brexit.

Comparisons between civil and political rights and economic, social and cultural rights

An outline follows of some of the main differences between civil and political rights and ESC rights. For more details see the SPICe Briefing - Economic, social and cultural rights - some frequently asked questions.

General points

ESC rights are often contrasted with civil and political rights such as the right to life, freedom of expression etc. Some argue that ESC rights have a weaker, more aspirational status than civil and political rights, and hence should be given less protection.

This is partly a result of history. Civil and political rights have their origins in western liberal democratic traditions and have been included in constitutions from the late eighteenth century (e.g. the US Constitution of 1791).

In contrast, the main impetus for ESC rights arguably emerged later, from the industrial revolution onwards when states increasingly took on a role in the organisation of economic and social matters.1 As a result, civil and political rights are sometimes referred to as "first generation rights" and ESC rights as "second generation rights."

To a degree, these historical differences are reflected in the scope of the rights. ESC rights often have a stronger focus on equality and the economic and social needs of individuals, whereas civil and political rights stress more the "freedom" of individuals and the protection of democratic processes. In addition, a number of civil and political rights require the state/others to refrain from acting in a certain way, whereas many ESC rights require states to determine how financial resources should be used.

Differences also exist at the level of national law, as in many countries it is more difficult for individuals to bring court actions based on ESC rights than where civil and political rights are involved.

However, this distinction is not without controversy and many, including the major international human rights bodies, take the view that ESC rights and civil and political rights are not fundamentally different and are part of a larger, interconnected package.

For example, the UN's Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights states that:

All human rights are indivisible, whether they are civil and political rights, such as the right to life, equality before the law and freedom of expression; economic, social and cultural rights, such as the rights to work, social security and education , or collective rights, such as the rights to development and self-determination, are indivisible, interrelated and interdependent. The improvement of one right facilitates advancement of the others. Likewise, the deprivation of one right adversely affects the others

United Nations - Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. (2021). What are human rights?. Retrieved from https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Pages/WhatareHumanRights.aspx [accessed 19 2021]

As an example, it explains that it is often harder for individuals who cannot read and write (i.e. who have not been given a right to education) to find work, to take part in political activity or to exercise their civil and political rights, such as the right to freedom of expression or the right to vote.3

Progressive realisation clauses

Unlike civil and political rights treaties, some ESC treatiesi contain what are known as "progressive realisation clauses".

For example, Article 2 of ICESCR states that:

Each State Party to the present Covenant undertakes to take steps, individually and through international assistance and co-operation, especially economic and technical, to the maximum of its available resources, with a view to achieving progressively the full realization of the rights recognized in the present Covenant by all appropriate means, including particularly the adoption of legislative measures.

This means that states' obligations are incremental ones which can be met over a period of time taking into account the availability of resources. The UN describes the obligation as follows:

At its core is the obligation to take appropriate measures towards the full realization of economic, social and cultural rights to the maximum of their available resources. The reference to “resource availability” reflects a recognition that the realization of these rights can be hampered by a lack of resources and can be achieved only over a period of time. Equally, it means that a State’s compliance with its obligation to take appropriate measures is assessed in the light of the resources—financial and others—available to it.

United Nations - Office of the High Commissioner. (2021). Key concepts on ESCRs - What are the obligations of States on economic, social and cultural rights?. Retrieved from https://www.ohchr.org/en/issues/escr/pages/whataretheobligationsofstatesonescr.aspx [accessed 9 September 2021]

The fact that states may realise ESC rights progressively doesn't mean that they have free rein, however.

The UN's Office of High Commissioner for Human Rights emphasises that many ESC rights are not subject to "progressive realisation" because their obligations kick in immediately (e.g. the elimination of discrimination in Article 2(2) of ICESCR), or because they do not require significant state resources (e.g. the right to form trade unions).

In addition, General Comment No. 3 of the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights stresses that, while the full realisation of the relevant rights may be achieved progressively:

steps to achieve compliance have to be taken within a reasonably short time after the obligations have come into force;

states should move as expeditiously and effectively as possible towards full realisation of the rights and should avoid retrogressive measures; and

there are minimum core obligations for each ESC right.

General comments are a UN treaty body’s interpretation of human rights treaty provisions, thematic issues or methods of work.2 They are not legal binding but are generally seen as providing authoritative statements on the law.3

Minimum core obligations

The UN's minimum core obligations act as a baseline for compliance with ESC rights in the ICESCR treaty. Unlike progressive realisation obligations, the minimum core obligations have immediate effect and are not primarily dependent on states' levels of development.

The general obligations are contained in General Comment No. 3 of the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), and also in separate General Comments dealing with specific areas of policy. These include:

CESCR General Comment No. 14: The right to the highest attainable standard of health

CESCR General Comment No. 191: The right to social security

CESCR General Comment No. 13: The right to education.1

CESR General Comment No. 3 explains the rationale for minimum core obligations as follows:

On the basis of the extensive experience gained by the Committee, as well as by the body that preceded it, over a period of more than a decade of examining States parties’ reports the Committee is of the view that a minimum core obligation to ensure the satisfaction of, at the very least, minimum essential levels of each of the rights is incumbent upon every State party. ... If the Covenant were to be read in such a way as not to establish such a minimum core obligation, it would be largely deprived of its raison d’être.

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. (1990, December 14). CESCR General Comment No. 3: The Nature of States Parties’ Obligations (Art. 2, Para. 1, of the Covenant) . Retrieved from https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/4538838e10.pdf [accessed 9 September 2021]

It also explains that derogating from the minimum core obligations should only be permitted in limited circumstances, noting that:

In order for a State party to be able to attribute its failure to meet at least its minimum core obligations to a lack of available resources it must demonstrate that every effort has been made to use all resources that are at its disposition in an effort to satisfy, as a matter of priority, those minimum obligations.

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. (1990, December 14). CESCR General Comment No. 3: The Nature of States Parties’ Obligations (Art. 2, Para. 1, of the Covenant) . Retrieved from https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/4538838e10.pdf [accessed 9 September 2021]

Although the General Comments provide some guidance on the minimum core obligations for ESC rights, they are not prescriptive rules and there is considerable debate about the nature and scope of the obligations.

In a recent paper drawn up for the Scottish Government's National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership, entitled "The Meaning and Content of Duties to be Considered for Inclusion in the Bill", Dr Katie Boyle characterises the debate as follows:

Critics of the MCO doctrine are concerned that by setting minimum criteria states will be concerned with achieving minimum standards rather than reaching beyond minimum criteria to progressive standards. Those in favour of the doctrine argue that it is required to ensure that, at the very least, minimum criteria are in place to avoid destitution. There is also disagreement as to what the MCO constitutes in both the literature and practice. By way of brief summary, these arguments centre around whether the obligation requires all states to meet the same minimum absolute standards (such as basic survival and the provision of shelter, food, water and sanitation). Others argue for a relative standard to apply. So for example, is the MCO relative to the wealth and resources of the state in question meaning a wealthier nation will be held to higher standards than a state with less resources at its disposal?

Scottish Government. (2020, June 1). The Meaning and Content of Duties to be Considered for Inclusion in the Bill. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/factsheet/2021/01/national-taskforce-for-human-rights-leadership-academic-advisory-panel-papers/documents/aap-paper-katie-boyle---meaning-and-content-of-duties/aap-paper-katie-boyle---meaning-and-content-of-duties/govscot%3Adocument/AAP%2BPaper%2B-%2BNationalTaskforce%2B-%2BKatie%2BBoyle%2B-%2BMeaning%2Band%2BContent%2Bof%2BDuties%2B-%2BJuly%2B2020%2B%25281%2529.pdf [accessed 9 September 2021]

Further discussion on this debate (in particular in relation to the right to health and the right to education) can also be found in academic papers drawn up for the World Bank in 2018.5

The European Convention on Human Rights and the Human Rights Act

The European Convention on Human Rights (Convention), a Council of Europe treaty which the UK ratified (i.e. agreed to be bound by)1 in 1951, is the main human rights treaty in Europe and arguably the most important source of human rights law in Scotland.

A key point to note is that the Convention mainly protects civil and political rights.

Certain economic, social and cultural rights such as property rights and the right to form and join trade unions are also protected, but this isn't the Convention's main focus.

The result is that many ESC rights are given less legal protection in Scotland than the civil and political rights in the Convention.

Since 1966, UK citizens have been able to bring cases based on the Convention to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg.2

However, as the UK has a 'dualist' legal system, which means that international treaties aren't part of UK law until put into legislation, people weren't able to rely directly on the Convention in the UK, for example by bringing cases against public bodies in UK courts.

The Human Rights Act, which came into force in October 2000, brought about a fundamental change to this system by incorporating the Convention, and hence a whole range of civil and political rights, directly into UK law.

As a result of the Human Rights Act, it is unlawful for public bodies across the UK (e.g. the police, local authorities, schools, the NHS etc.) to breach someone's Convention rights (section 6). Public bodies have to comply with the Convention and can be taken to court if they don't (section 7).

Legislation also has to be read as far as possible in a way which complies with Convention rights (section 3 of the Human Rights Act).

In addition, if a UK Act of Parliament doesn't comply with the Convention, courts can make a “declaration of incompatibility” (section 4 of the Human Rights Act). This doesn't automatically strike down the legislation (the UK Parliament can leave it in place). However, if there is the political will to do so, the law may be changed. See below for examples of these two approaches.

UK Acts of Parliament and "declarations of incompatibility"

In a Supreme Court case in 2018,3 the court found that not allowing heterosexual couples to enter civil partnerships in England was discriminatory and declared the law incompatible with the Convention. Changes to the English law on civil partnerships followed shortly thereafter which were mirrored in Scotland in the Civil Partnership (Scotland) Act 2020.

In contrast, although the courts had declared the UK's prisoner voting ban to be incompatible with the Convention in 2005 in the Hirst case, the law in England didn't change until 2018 and then only as the result of a political compromise reached between the UK and the Council of Europe.4 Changes which went further than those in England followed in Scotland in the Scottish Elections (Franchise and Representation) Act 2020.5

UN reporting system and Universal Periodic Review

Unlike the European Convention on Human Rights, the UN framework for protecting ESC rights isn't backed up by an international court which people in Scotland can bring cases to. There is no international equivalent of the European Court of Human Rights.

Instead, the UN treaties provide for a range of less formal mechanisms based on political persuasion rather than court action by individuals.

Arguably, the most important mechanism is the system of independent expert committees which monitor countries' implementation of the core human rights treaties.

Each treaty has an expert committee. On a periodic basis, states are required to submit reports to the relevant committee on their progress in implementing the rights in question. In the UK, reports are submitted by the UK Government which takes into account input from the devolved nations.

The committees consider each national report in conjunction with evidence submitted by other organisations before making formal recommendations to the state in what are known as “concluding observations.”

Concluding observations are not legally binding and there is no legal sanction for non-compliance. Instead they are designed to encourage change by highlighting problems and putting political pressure on the state in question - both at an international level and domestically.

In addition to the review of compliance by treaty bodies, the UN system also includes a "Universal Periodic Review" (UPR) process. This is a peer review system in which the human rights records of all 193 UN Member States are reviewed on a periodic basis by the other Member States.

The UPR process ends with recommendations being made to the states who are under review. These are not binding in the legal sense. Instead, the process envisages that states implement recommendations in the period between reviews (known as the "follow up") with states involved in the following review cycle having responsibility for monitoring implementation.

For more details on how ESC rights are protected and enforced by the UN see the SPICe Briefing - Economic, social and cultural rights - some frequently asked questions.

Human rights and the environment

In recent times, the need to protect the environment has also begun to be seen as a human right. For example, various countries have included the right to a healthy environment in their constitutions.

Environmental rights are a developing area of international human rights law. On 8 October 2021, the UN Human Rights Council recognised, for the first time, that having a clean, healthy and sustainable environment is a human right1. At the same time, through a second resolution, the Council also increased its focus on the human rights impacts of climate change by establishing a Special Rapporteur dedicated to that issue. There had been calls for the UN to formally recognise a right to a healthy environment for some time, with both the current and previous UN Special Rapporteurs on Human Rights and the Environment recommending that the right should be incorporated in an international human rights instrument23.

In passing the resolution, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights called on states to take bold actions to give prompt and real effect to the right to a healthy environment, stating that the decision, “clearly recognises environmental degradation and climate change as interconnected human rights crises.”1

Largely as a result of climate change (and growing consciousness about implications of loss of biodiversity) there are also arguments that there should be "rights for future generations". The broad aim behind this movement is to provide a higher level of protection for the environment than under current environmental laws, and to more systematically recognise links between environmental quality and human health and wellbeing.

For more details on environmental human rights see the SPICe Briefing - Human Rights and the Environment. 5

Devolution - complying with human rights law

Human rights are also an integral part of the devolution settlement and hence policy made by the Scottish Government and Parliament.

The Convention

Scottish Parliament legislation has to comply with the Convention (section 29 of the Scotland Act 1998).

However, unlike UK legislation, there is no "declaration of incompatibility" procedure.

Instead, Scottish Parliament legislation which does not comply with the Convention is unlawful and can be "struck down" in the courts (in other words declared unlawful and unenforceable). This is possible in both civil and criminal cases, including in "judicial review" proceedings - a special type of court procedure which allows decisions by public bodies and the government to be challenged.

For example, in 2016 the Supreme Court held that part of the Scottish Government's mandatory "named person" legislation was unlawful as it interfered disproportionately with the right to respect for private and family life.12 The Scottish Government ultimately announced that it would withdraw the legislation after being unable to find a compromise which would be compatible with the Supreme Court's judgment.34

Scottish Government regulations and other executive action can also be struck down if they don't comply with the Convention. A recent example is the case which was brought against the COVID-19 regulations closing all places of worship in Scotland. The Court of Session held that the regulations were unlawful as they interfered disproportionately with the freedom of religion (Article 9 of the Convention).56

International treaties

Although international treaties are entered into by the UK Government, the devolution settlement also includes various requirements on Scottish Parliament legislation to comply with international obligations, e.g. UN human rights treaties.

In addition, the Scottish Ministerial Code also makes it clear that Ministers must comply with the law, including international law and human rights treaties.

However, there is currently no legislation like the Human Rights Act which brings international obligations or ESC rights like the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights into UK or Scots law. Compliance remains a matter for international law and diplomacy.

Consequently, unless legislation specifically requires this, public bodies aren't required to comply with international ESC rights in the same way they have to comply with the Convention due to the Human Rights Act.

In addition, Scottish Parliament legislation can't be struck down if it doesn't comply with a UN treaty.

As a result, it is not possible to rely on UN rights, or other international ESC rights, in the same way as the Convention - for example by bringing a case in a UK court when legislation, or action by a public body, breaches a UN human rights treaty.

In addition, there is no equivalent to the European Court of Human Rights at UN level. As outlined, the UN treaties provide for a range of less formal mechanisms based on political persuasion rather than court action by individuals

The EU's Charter of Fundamental Rights

Before the UK had left the European Union, Scottish Parliament legislation also had to comply with EU law, including the EU's Charter of Fundamental Rights, in addition to the Convention. The Charter is the EU's core human rights law which applies to Member States when they implement, derogate from or act within the scope of EU law.

The European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 (Withdrawal Act) which repealed the legislation which brought the UK into the EU also brought changes to the devolution settlement.

Under the new rules (section 30A of the Scotland Act 1998), the Scottish Parliament has to comply with "retained EU law" - in other words the EU law (and UK domestic law implementing it) which the UK Government decided to keep as a starting point once the UK had left the EU. However, it no longer has to comply with the Charter as it was not retained by the UK Government in the Withdrawal Act (see section 5(4)).

The Scottish Government attempted to retain the Charter itself in Scots law in its Continuity Bill.i However, the Supreme Court held that the Scottish Parliament did not have the power to do this as it was an attempt to modify UK legislation (the Withdrawal Act) which expressly stated that the Charter is not part of UK law following Brexit.12As a result, the Charter is no longer a legal source in Scotland.

Devolution: proactive protection of ESC rights

Crucially, the role for human rights in Scotland goes much further than simply ensuring that legislation complies with the Convention or international law. The devolution settlement also allows for proactive measures to be taken in Scotland to protect human rights, including ESC rights.

The legal reason for this is that, although treaties are entered into by the UK Government, the Scottish Government has the power, in devolved areas, to implement the UK's international obligations, including human rights treaties.i In addition, the Scottish Government can also set its own human rights policy and priorities in devolved areas including in relation to ESC rights.

Although not always expressed in human rights terms, ESC rights have played a key part in politics and policy-making in Scotland in recent years, in particular in relation to arguments around land reform, children's rights, social justice, inequalities, and Scotland's relationship with the EU.

Most recently, the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (Incorporation) (Scotland) Bill incorporated the rights in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) into Scots law. The legislation has, however, not yet come into force, as, following a legal challenge by the UK Government, the Supreme Court ruled that some of its provisions restrict the power of the UK Parliament to make laws for Scotland and are therefore outside of the Scottish Parliament's devolved powers.12

The Scottish Government has restated its commitment to full incorporation to the maximum extent possible.3 In a letter to the Secretary of State for Scotland from February 2022 the Deputy First Minister, John Swinney MSP, stated:

In the meantime, we are planning to return the Bill to the Scottish Parliament for reconsideration. We are currently considering very carefully how to deliver UNCRC incorporation to the maximum extent possible within the limits of the devolution settlement as now clarified by the Supreme Court’s decision

Swinney, J. (2022, February 1). Update regarding the UK Supreme Court judgment on the UNCRC Incorporation Scotland Bill. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/chamber-and-committees/committees/current-and-previous-committees/session-6-equalities-human-rights-and-civil-justice-committee/correspondence/2022/update-regarding-the-uk-supreme-court-judgment-on-the-uncrc-incorporation-scotland-bill [accessed 13 March 2022]

The timescale is not yet clear, but the procedure would involve the Scottish Parliament reconsidering an amended bill which complies with the Supreme Court's judgment (see the Scottish Parliament's Standing Orders (Rule 9.9)).

For more details on the relevance ESC rights have for politics and policy in Scotland see the SPICe Briefing - Economic, social and cultural rights - some frequently asked questions.

Devolution: divergence in human rights policies between Westminster and Scotland

Although the legal framework for human rights is broadly the same across the UK,i in recent years there has been increasing divergence between the high level human rights policies of the UK Government and the Scottish Government.

Without looking at individual policies on the ground, some of the main high level differences include:

Views on the Human Rights Act

From an early stage, the Human Rights Act has been the subject of criticism at Westminster with arguments being made that it gives too much power to the courts and has a negative impact in areas such as counter-terrorism and criminal law.1

Linked to this is the long-standing campaign within the UK Conservative Party to repeal the Human Rights Act and to replace it with a "British Bill of Rights."2

In 2015, the then Prime Minister, David Cameron MP, stated in the House of Commons that:

Our intention is very clear: it is to pass a British Bill of Rights, which we believe is compatible with our membership of the Council of Europe. As I have said at the Dispatch Box before—and no one should be in any doubt about this—issues such as prisoner voting should be decided in this House of Commons. I think that that is vital. So let us pass a British Bill of Rights, let us give more rights to enable those matters to be decided in British courts, and let us recognise that we had human rights in this country long before Labour’s Human Rights Act.

Hansard. (2015). House of Commons Debate 8 July 2015. Retrieved from https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201516/cmhansrd/cm150708/debtext/150708-0001.htm [accessed 20 May 2021]

Although legislation on a Bill of Rights wasn't forthcoming, the UK Government established an independent review of the Human Rights Act in 2020 whose terms of reference were to examine:

the relationship between domestic courts and the European Court of Human Rights; and

the impact of the Human Rights Act on the relationship between the judiciary, the executive and the legislature.

The Independent Review's report, which was published in December 2021, proposed certain changes to the law but did not recommend fundamental reform.

In contrast, the UK Government's consultation on a new Bill of Rights, which was also published in December 2021, proposes fundamental changes to the Human Rights Act. The Executive Summary to the consultation outlines the plans as follows:

We will overhaul the Human Rights Act passed by the then Labour government in 1998 and restore common sense to the application of human rights in the UK. We will remain faithful to the basic principles of human rights, which we signed up to in the original European Convention on Human Rights ... The Bill of Rights will protect essential rights, like the right to a fair trial and the right to life, which are a fundamental part of a modern democratic society. But we will reverse the mission creep that has meant human rights law being used for more and more purposes, and often with little regard for the rights of wider society.

UK Government - Ministry of Justice. (2021, December). Human Rights Act Reform: A Modern Bill Of Rights A consultation to reform the Human Rights Act 1998. Retrieved from https://consult.justice.gov.uk/human-rights/human-rights-act-reform/supporting_documents/humanrightsreformconsultation.pdf [accessed 26 January 2022]

The Scottish Government view is that the current regime does not need to be changed. In a submission to the UK Government's independent review in March 2021, the then Cabinet Secretary for Social Security and Older People, Shirley-Anne Somerville MSP, stated that:

The Human Rights Act is one of the most important and successful pieces of legislation ever passed by the UK Parliament ... Our submission to the Review highlights the impact that any changes to the Act could have in eroding human rights. The Act is at the heart of Scotland’s devolved constitutional arrangements. No changes that would impact on Scotland should be made without the explicit consent of the Scottish Parliament.

Brexit

Brexit has also been an additional area of conflict. One example is the Scottish Government's attempt to retain the EU's Charter of Fundamental Rights in Scots lawwhich was held to be unlawful by the Supreme Court.

The Scottish Government's proposals

For some time, there have also been calls to treat UN treaties which protect ESC rights in a similar way as the Convention and to incorporate them into Scots law.1

In March 2021, the then Cabinet Secretary for Social Security and Older People, Shirley-Anne Somerville MSP, indicated that the Scottish Government was in favour of this approach and that, if elected, it would bring forward a new Human Rights Bill which would incorporate four United Nations Human Rights treaties into Scots Law as well as "a range of others rights on the environment, older people, and access to justice".

This section of the briefing briefly outlines the background to the Scottish Government's proposals and the proposals themselves.

First Minister's Advisory Group on Human Rights Leadership

The 2017-18 Programme for Government indicated that the Scottish Government would consider "how we can go further to embed human, social, cultural and economic rights including the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child." It also made a commitment to:

establish an expert advisory group to lead a participatory process to make recommendations on how Scotland can continue to lead by example in human rights, including economic, social, cultural and environmental rights

That advisory group, "the First Minister's Advisory Group on Human Rights Leadership" chaired by Professor Alan Miller, was set up at the end of 2017 and reported back in December 2018.

The group made various findings based on its analysis and consultation with public bodies, civil society and rights-holders (i.e. those entitled to protection under the UN treaties).

From the perspective of rights-holders, the key findings in the report were that:

There is inadequate legal protection - the report states that:

Laws giving people rights are not sufficiently put into policy and practice by public bodies. There are barriers to access to justice.

First Minister's Advisory Group on Human Rights Leadership. (2018, December 10). Recommendations for a new human rights framework to improve people’s lives: Report to the First Minister. Retrieved from https://humanrightsleadership.scot/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/First-Ministers-Advisory-Group-on-Human-Rights-Leadership-Final-report-for-publication.pdf [accessed 16 October 2020]

There is insufficient practical implementation - according to the report:

Public service providers do not deliver these services in a way which sufficiently respects and fulfils the rights of people. This is often due to lack of resource but can also be due to a lack of training, awareness of rights, and sometimes just a lack of empathy and respect for dignity.

First Minister's Advisory Group on Human Rights Leadership. (2018, December 10). Recommendations for a new human rights framework to improve people’s lives: Report to the First Minister. Retrieved from https://humanrightsleadership.scot/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/First-Ministers-Advisory-Group-on-Human-Rights-Leadership-Final-report-for-publication.pdf [accessed 16 October 2020]

There is inadequate everyday accountability - the report indicates that:

Inspectors, regulators, complaints handlers and adjudicatory bodies do not consistently do enough to uphold the rights of people. This again can be the result of lack of resource and lack of training and awareness, although there is significant emerging good practice.

First Minister's Advisory Group on Human Rights Leadership. (2018, December 10). Recommendations for a new human rights framework to improve people’s lives: Report to the First Minister. Retrieved from https://humanrightsleadership.scot/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/First-Ministers-Advisory-Group-on-Human-Rights-Leadership-Final-report-for-publication.pdf [accessed 16 October 2020]

Public bodies also appear to have a lack of knowledge and experience in implementing UN rights, with the report finding that:

While there was definite interest, there was found to be a low level of awareness of the implications of giving effect to rights from UN treaties and how to practically implement them throughout law, policy and practice. All strongly emphasised the need to learn how to do so effectively in a stepwise and manageable manner

First Minister's Advisory Group on Human Rights Leadership. (2018, December 10). Recommendations for a new human rights framework to improve people’s lives: Report to the First Minister. Retrieved from https://humanrightsleadership.scot/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/First-Ministers-Advisory-Group-on-Human-Rights-Leadership-Final-report-for-publication.pdf [accessed 16 October 2020]

The report therefore recommended that a bill should be introduced in the Scottish Parliament which would put all international human rights in one place. The bill would contain:

civil and political rights, restated from the Human Rights Act

economic, social and cultural rights, such as the right to adequate housing and the right to adequate food (these would be incorporated from the UN treaty ICESCR)

the right to a healthy environment , including substantive elements (the right to benefit from healthy ecosystems which sustain human wellbeing) and procedural elements, such as rights of access to information, participation in decision-making and access to justice

rights belonging to different groups, such as children, women and disabled people (these would be incorporated from the relevant UN treaties).

The report also recommended that the Bill should include:

a duty on courts to read legislation in line with the rights in the Bill;

a duty on public bodies to comply with these rights following a transition period; and

rules aimed at improving access to justice.

The report considered whether the Bill should allow Scottish Parliament legislation which doesn't comply with the new rights to be "struck down" in the courts. However it didn't take a final view on this noting that "further consideration would need to be given to whether such a provision is within the legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament."

The report also recommended that there should be "capacity-building" (in other words education, training and awareness-raising) to enable effective implementation of the Act by public bodies, and that there should be a national mechanism for monitoring the implementation of human rights in line with UN practices. It also recommended that the Equalities and Human Rights Committee should be given enhanced powers to scrutinise legislation.

The report emphasised that the main reason for setting up a new human rights framework was to "improve people's daily lives". It stressed that:

Improving people’s lives is, however, not something that is only done for people. It works better when it is done with and by people. This is what a human rights-based approach brings to the table and this is what is promoted by the Advisory Group recommendations.

First Minister’s Advisory Group on Human Rights Leadership. (2018, December 10). First Minister’s Advisory Group on Human Rights Leadership - Report to the First Minister. Retrieved from https://humanrightsleadership.scot/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/First-Ministers-Advisory-Group-on-Human-Rights-Leadership-Final-report-for-publication.pdf [accessed 25 May 2021]

The First Minister welcomed the report and said that she would set up a Task Force in early 2019 to take forward the recommendations. She also supported the group's recommendation that new legislation should be developed through public engagement, working across the public sector, civic society and the Scottish Parliament.

National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership

The National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership was established in early 2019 to take forward the recommendations of the First Minister's Advisory Group on Human Rights Leadership (FMAG).

It was co-chaired by Shirley-Anne Somerville MSP, the then Cabinet Secretary for Social Security and Older People, and Professor Alan Miller. It included members from the public sector and civil society, as well as an academic advisory panel which provided a range of briefings for the Taskforce.

After taking evidence from a range of stakeholders (see Annex E of the report for details), the Taskforce published its report on 12 March 2021.

Proposals for a new Human Rights Bill

In line with FMAG's recommendations, the Taskforce's report proposes a Bill which would:

reaffirm the rights in the Human Rights Act

incorporate into Scots law ESC rights in the UN treaty ICESCR and three UN treaties on race (CERD), women (CEDAW) and disability (CRPD)

cover the right to a healthy environment, the rights of older people and the rights of LGBTI people

include a general equality clause aimed at providing equal access for everyone, including LGBTI people, to the rights in the Bill.

The report argues that it would be best to incorporate all the rights in one comprehensive Bill noting that:

... based on FMAG recommendations and the evidence received, the best approach to incorporation would be to have a comprehensive single Bill where all treaties considered in the Taskforce remit are incorporated together. As human rights are indivisible, interdependent, and interrelated, a one-Bill approach with all treaties incorporated will help to reinforce the inter-relationship between all rights and obligations.

Scottish Government. (2021, March 12). National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership Report. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/national-taskforce-human-rights-leadership-report/ [accessed 25 June 2021]

It also explains that its recommendations are based on three principles:

an internationalist approach - in other words a framework which is directly linked to rights in international treaties and which keeps pace with international developments

a maximalist approach - i.e. the aim being to achieve "the most effective promotion and protection of human rights within devolved competence"

a multi-institutional approach - in other words an approach where responsibility is spread among parliament, government, the courts, inspectorates, regulators, and national human rights institutions with the aim of increasing public participation in the system.

Crucially public bodies would be under a duty to comply with the new rights after a transition period has expired. This is one of the key provisions as it will make it unlawful for public bodies to breach the rights protected in the Act.

The report doesn't take a firm line on how legislation should be dealt with under the Bill (in other words options for striking down legislation). Instead it states that this should be explored in more detail, noting that:

"Additionally and specifically, it is considered that it be further explored whether there could be a provision, akin to a “devolution issue” under the Scotland Act 1998, whereby a compatibility issue with any of the relevant treaties can be the subject of challenge in judicial and administrative proceedings. Its effect would be to refer the point to the relevant superior court for determination."

Devolution issues are defined in Schedule 6 of the Scotland Act 1998 and include questions whether an Act of the Scottish Parliament is within the Scottish Parliament's powers. The Schedule also sets out procedural rules which apply where a “devolution issue” arises in court proceedings.

Rationale for change

The foreword to the report outlines the Taskforce's arguments for a new human rights framework.

In line with the FMAG report, the core argument is that the new rights would improve society and people's lives. On this point, the Taskforce's report argues that:

... we have reached a moment in time for the introduction of a new human rights framework for Scotland, to improve all of our lives, our society and contribute to a better world.

Scottish Government. (2021, March 12). National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership Report. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/national-taskforce-human-rights-leadership-report/ [accessed 25 June 2021]

The report further argues that a new framework is a logical step in the process of devolution, noting that:

Many developments have contributed to bring us to this moment in time. From a human rights perspective, Scotland has become increasingly confident and internationalist throughout the past twenty years of devolution and the introduction of this new framework is the next step on its human rights journey.

Scottish Government. (2021, March 12). National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership Report. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/national-taskforce-human-rights-leadership-report/ [accessed 25 June 2021]

The foreword explains that the new framework would put the full range of international human rights in a single place for the first time with the aim being "to provide full and equal access to the enjoyment of these rights and the maximum protection possible to everyone within the current constitutional arrangements."

Brexit and the COVID-19 pandemic are also referred to as additional reasons for change.

New framework and new rights

Much will depend on the exact content of the Bill. However, as outlined in the diagrams below, at a very basic level the proposals would lead to:

A new human rights framework for Scotland; and

Protection for a large number of ESC rights and other human rights in areas of devolved competence.

Note that the right to education appears in both diagrams as it is protected in both the European Convention on Human Rights and ICESCR.

Recommendations aimed at strengthening the legal rights in the Bill

It is important to stress that the Taskforce's proposals go much further than simply adding new rights into the existing human rights framework.

The report also makes a large number of recommendations aimed at strengthening the legal rights which will be incorporated in the Bill.

These largely follow the recommendations of the First Minister's Advisory Group on Human Rights Leadership. Their broad aim, linked to the report's "multi-institutional approach", is to ensure that the rights are "made real in everyday life" and don't just remain as abstract legal principles which aren't followed or enforced in practice.

The recommendations are focused on two main areas:

implementation duties for the Scottish Government, public authorities and courts (Chapter 2 of the Report)

capacity-building, public participation, monitoring of outcomes and access to justice (Chapter 3 of the Report).

Implementation duties

The main recommendations as regards implementation duties include:

Putting public bodies under a duty to comply with the new rights after a transition period has expired. This is arguably one of the key provisions as it will make it unlawful for public bodies to breach the rights protected in the legislation.

Requiring public bodies to have "due regard" to the rules before the full "duty to comply" kicks in (the aim is to give public bodies sufficient time to prepare for the new compliance duty while still having to make the necessary preparations).

A "purpose clause" in the Bill which states that the intent of the legislation is to give maximum possible effect to human rights.

An obligation on courts to pay regard to international law including decisions, general comments and concluding observations from UN treaty bodies, and judgments, decisions, declarations and advisory opinions of the European Court of Human Rights.

Giving the Scottish Human Rights Commission (SHRC) additional powers including the right to take test cases and to conduct investigations.

A "participatory process" (involving members of the public, civil society organisations and stakeholders) to define the core minimum obligations of ESC rights in the Bill.

An explicit duty of progressive realisation taking into account the content of each right.

Enhanced pre-legislative scrutiny in the Scottish Parliament to ensure that future Bills have to comply with the rights in the new framework and not just Convention rights.

Requiring the Scottish Government to be accountable for planning and reporting on how they are fulfilling the rights and obligations under the Bill in practice. This involves publishing a "Human Rights Scheme" and is akin to the Children's Rights Scheme which was part of the UNCRC Bill (see the SPICe briefing on the UNCRC Bill).

Rules on how the legislation will apply to private bodies which have public functions (e.g. when these functions have been outsourced by government).

Statutory and non- statutory guidance developed through consultation with key stakeholders.

The report argues that these elements are necessary so that the rights are fully implemented in practice, noting that:

The primary purpose of these additional elements is to ensure as far as possible the effective implementation of the framework and so improve people’s lives.

Scottish Government. (2021, March 12). National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership Report. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/national-taskforce-human-rights-leadership-report/ [accessed 25 June 2021]

According to the report, the strategic objectives are as follows:

4. The Framework, and human rights protection more widely, keeps pace with progressive international developments

5. The Framework ensures duty-bearers build human rights into all relevant processes and decision-making

6. The Framework ensures compliant and progressively realising human rights legislation is passed by the Scottish Parliament and consideration is given as to whether human rights based monitoring and scrutiny of law and practice could be increased by the Scottish Parliament.

Scottish Government. (2021, March 12). National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership Report. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/national-taskforce-human-rights-leadership-report/ [accessed 25 June 2021]

A key point to note is that the proposals don't take a final view on what should happen to Scottish Parliament legislation which breaches the ESC rights protected in the Bill. Instead the Task Force's report indicates that this needs further thought:

Additionally and specifically, it is considered that it be further explored whether there could be a provision, akin to a “devolution issue” under the Scotland Act 1998, whereby a compatibility issue with any of the relevant treaties can be the subject of challenge in judicial and administrative proceedings. Its effect would be to refer the point to the relevant superior court for determination.

Scottish Government. (2021, March 12). National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership Report. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/national-taskforce-human-rights-leadership-report/ [accessed 25 June 2021]

Capacity-building, public participation, access to justice and monitoring recommendations

The main recommendations on capacity building, public participation, access to justice and monitoring include:

Requiring the Scottish Government to provide adequate resources and clear guidance to:

public bodies so that they can comply with the new human rights duties; and

scrutiny bodies (i.e. regulators, inspectorates and complaints-handling bodies) so that they can oversee how public bodies implement the new human rights,

Better information and advice - Ensuring people have the information they need on their rights as well as easy access to advice.

Strengthening "access to justice" - the aim here is to reduce access to justice barriers (e.g. difficulty accessing legal representation/legal aid, lack of information and advice about rights etc.) so that people have effective remedies to enforce their rights.

Public participation. The report proposes that:

the public (including specific groups affected by the legislation and marginalised groups) should be engaged in developing the framework

the Scottish Government should develop a large scale public awareness campaign

further consideration should be given to including an explicit right to participation in the legislation so that there will be public participation on an ongoing basis.

Monitoring of outcomes. The report emphasises that effective monitoring of outcomes is essential to measure the impact on the ground. It proposes a range of options, including:

monitoring at a national level

monitoring of public authorities

monitoring of budgets.

According to the report, the strategic goals behind these recommendations are as follows:

7. The implementation of the framework is effectively monitored and scrutinised, including through “everyday accountability”, where human rights are part of a broader system of checks on compliance. The framework advances access to justice for people whose rights are not being met

8. The framework provides for effective remedies where people’s rights are not being respected, protected or fulfilled

9. The framework is put into practice as soon as possible, with both duty-bearers and rightsholders supported to secure and advance its implementation

10. The public participation in the establishment and implementation of the framework is essential, along with the essential capacity-building of duty-bearers, to further develop a human rights culture

11. The framework gives practical effect to a multi-institutional model of human rights protection and fulfilment, reflecting the shared responsibility of multiple actors to respect, protect and fulfil human rights.

Scottish Government. (2021, March 12). National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership Report. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/national-taskforce-human-rights-leadership-report/ [accessed 25 June 2021]

Some high level issues

The proposals are ambitious ones in terms of the rights which would be protected, the areas of policy covered and the scope of the recommendations for strengthening the new framework (for example, the range of duties put on public bodies, and the proposals as regards access to justice).

The foreword to the report emphasises this point indicating that its recommendations "are challenging, ambitious and need bold leadership to implement" and that the Bill would be the "biggest step taken in Scotland’s human rights journey."

It also explains that the recommendations will be complex to implement and will provide a challenge to government:

There is no doubt that these recommendations present a big challenge to the government – to build on and accelerate the progress we have already made on human rights through this radical, new statutory framework. Undoubtedly, developing and implementing a framework of this nature will be complex and there are some aspects which we will require to give particularly careful consideration to if we are to do it justice.

Scottish Government. (2021, March 12). National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership Report. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/national-taskforce-human-rights-leadership-report/ [accessed 25 June 2021]

Although much will depend on the scope of the Bill when it is introduced, a brief outline follows of some high level issues which are likely to be relevant.

These are not meant to be exhaustive and only provide a flavour of some of the bigger questions which may arise. The issues noted also don't deal with the specifics of each of the various rights which the proposals aim to protect or with the relationship between different sets of rights. By definition each policy area will have its own individual set of concerns and there will also be complex questions about how different rights relate to each other.

Basic principle: incorporation of ESC rights into national law

The basic principle behind the proposed bill is that a range of internationally protected economic, social and cultural rights (ESC rights) need to be brought into national law in Scotland to have a meaningful effect on policy and on people's lives.

In that sense the aim behind the Bill is to broadly reflect the protection granted to civil and political rights in the Human Rights Act 1998, but then for ESC rights.

This would mean that public bodies would have to comply with ESC rights as well as the civil and political rights in the Convention. All of these rights would be in one Act and people would ultimately be able to enforce their rights in the courts if public bodies don't comply with them. Although their scope is not yet fully clear, there would also be compliance obligations on legislation.

One rationale behind the proposals is a practical one (what the Taskforce calls "making rights real"). However, there is also an underlying principled argument that ESC rights shouldn't be seen as different from civil and political ones. This is stressed in the Taskforce's report which argues that both sets of rights are crucial for "human dignity",i stating that:

As human rights are indivisible, interdependent, and interrelated, a one-Bill approach with all treaties incorporated will help to reinforce the inter-relationship between all rights and obligations

Scottish Government. (2021, March 12). National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership Report. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/national-taskforce-human-rights-leadership-report/ [accessed 25 June 2021]

It is important to note though that there is a long-standing debate about the degree to which ESC rights should be given the same legal protection in national law as civil and political rights.

The debate is a complex one.ii However, some of the key areas of contention include:

The degree to which ESC rights and civil and political rights are actually the same in scope

In overly stark terms, the debate is between those who take the view that only civil and political rights represent universal moral rights worthy of legal protection (with ESC rights having a weaker, more aspirational status) and those who consider that ESC rights also have a universal quality and that all rights are ultimately interlinked in practice.

For more details see the section of the SPICe briefing on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights entitled "How do ESC rights differ from civil and political rights?"

The impact on the democratic process and of enforcing ESC rights through the law

The broad debate here is between those who take the view that, in a democracy, elected representatives and not courts should have the role of forming economic and social policyiii and those who see the courts as providing a larger role in the legal framework (particularly for marginalised groups) in ensuring that government and the legislature comply with fundamental rights (including ESC rights)

Concerns that the courts do not have the capacity to determine disputes on ESC rights

Here the debate is largely between those who are of the view that the courts lack the right expertise, tools and remedies to deal with disputes involving competing claims on financial resources and those who consider that courts are able to deal with these sorts of issues. One of the arguments in favour of courts taking on this role is that they already carry out complex balancing exercises in other areas of law, for example in cases involving civil and political rights, or in fields such as competition law or state aid where decisions need to be taken based on market principles.

Given the scope of the proposals and their impact on many areas of economic and social policy (as well as the additional focus on the environment and equality policy), this debate on first principles is likely to be a key issue when the Bill is introduced.

Impact on numerous areas of policy

Bringing the range of rights proposed into domestic law will have an impact on numerous areas of policy.

ESC rights

Through progressive realisation, Article 2 of ICESCR protects a large number of rights including:

the right to an adequate standard of living including: adequate food, clothing and housing, and the continuous improvement of living conditions

the right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health

the right to education

the right to social security

the right to form and join trade unions

the right to take part in cultural life.

The new rights will therefore be of importance for issues such as :

the current debate on food poverty and the proposed Good Food Nation Bill

homelessness, housing affordability, housing quality, tenants' rights etc.

As a discussion paper commissioned by the Association of Local Authority Chief Housing Officers argues, one of the key issues will be to define the practical meaning of the right to "adequate housing" in a Scottish context. 1In general comment 4, the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights identifies seven key conditions which must be met for housing to be considered adequate: security of tenure; availability of services, materials, facilities and infrastructure; affordability; habitability; location; and cultural adequacy.

The Scottish Government’s vision for housing and route map Housing to 2040, published in March 2021, includes a commitment to align its plans with the human rights agenda. The Scottish Government plans to undertake an audit of current housing and homelessness legislation to understand how best to realise the right to an adequate home. 2 Many of the more specific plans set out in Housing to 2040, including a new homelessness prevention duty for public bodies, a new renters’ strategy (backed by legislation where appropriate), legislation on housing conditions and increasing affordable housing supply will be developed in this context.

Health policy

The right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health will be relevant to addressing the issue of health inequality, i.e. narrowing the gap between the health and life expectancy of the poorest and the wealthiest.

In addition, it could also impact on the review and reform of mental health and incapacity legislation that is anticipated.

Education policy

Human rights issues are likely to impact on the Scottish Government's current work to reform the Curriculum for Excellence (CfE), replace the Scottish Qualifications Authority and reform Education Scotland . This work, currently in its early stages, will shape the primary and secondary school curriculum and assessment framework for the foreseeable future. The reforms follow OECD reports on CfE and assessment.

The Higher Education sector's efforts to widen access to university to those from the least well-off areas in Scotland will also be relevant. The Commission on Widening Access set a target that by 2030, 20% of first year university entrants should come from the 20% most deprived communities. The sector has met an interim target of 16% by 2021, but the Commissioner for Fair Access warned in his latest annual report that progress was threatened due to the disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on poorer communities.

Learner access to digital technology will likely also be relevant. Funding to provide supportfor students, school pupils and care leavers without access to digital technology was provided during the pandemic, and the 2021-22 Programme for Government commits to providing all school age children with a device and connection to get online. Progress on providing these devices is likely to be seen as an important measure of ensuring access to education.

Equality

The proposal to incorporate three UN treaties on race (CERD), women (CEDAW) and disability (CRPD), and to include rights for older people, and an equality clause including provision for LGBTI people will also be of importance to various aspects of equality policy.

The National Taskforce on Human Rights indicated that incorporation of the three UN treaties, which provide civil and political, and social, economic and cultural rights, would help raise awareness about continuing inequalities and help to address barriers. It also stated that their incorporation would strengthen the existing Public Sector Equality Duty (currently under review) and the Fairer Scotland Duty.

There are no UN treaties which specifically address older people and LGBTI people. However, according to the Task Force such rights could be drawn from existing UN treaties. This will likely require further consideration and consultation.

There is also a proposal to include an equality clause “which aligns with the Equality Act 2010 and provides equal access to everyone to the rights contained within the Bill.” This will likely need to cover the relationship, and perhaps set boundaries, between the Equality Act, which is mainly reserved, and the new Bill, which is devolved.

The Human Rights Consortium Scotland has published a range of briefings by Professor Nicole Busby and Dr Kasey McCall-Smith, outlining the content of treaties and rights, including on CEDAW, CRPD, and CERD.

The right to a healthy environment

The First Minister's Advisory Group on Human Rights Leadership recommended in 2018 that the new human rights framework should include a "right to a healthy environment". It stated:

This overall right will include the right of everyone to benefit from healthy ecosystems which sustain human well-being as well [sic] rights of access to information, participation in decision-making and access to justice. The content of this right will be outlined within a schedule in the Act with reference to international standards, such as the Framework Principles on Human Rights and Environment developed by the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment, and the Aarhus Convention.

The 2021 report by the National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership went on to recommend that the proposed right include both "substantive" and "procedural" elements. The report states:

Through providing a right to a healthy environment the framework will demonstrate support for the Paris Agreement, demonstrate global leadership in supporting climate justice and contribute to the international cooperation so urgently needed to face the underlying climate crisis.

Substantive elements refers to the actual elements of the right to a healthy environment. According to the report by the National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership, these elements include:

clean air, a safe climate, access to safe water and adequate sanitation, healthy and sustainably produced food, non-toxic environments in which to live, work, study and play, and healthy biodiversity and ecosystems

Scottish Government. (2021, March 12). National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership Report. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/national-taskforce-human-rights-leadership-report/ [accessed 25 June 2021]

It is important to note that there are also interactions between the right to a healthy environment and other proposed rights such as those relating to health and wellbeing, or the right to food. There is growing evidence that environmental quality is linked to health outcomes (for example, in relation to air and water quality, chemicals, biodiversity, and local access to nature and greenspace).234 In addition, equality issues can be relevant given the way that pollution and environmental damage more often affect socially deprived communities.4

In other words, there are arguments that the full enjoyment of other human rights could be dependent on first having a healthy environment. In 2018, David R. Boyd, Special Rapporteur on human rights and the environment, said in a statement to the UN General Assembly:

It is beyond debate that people are wholly dependent on a healthy environment in order to lead dignified, healthy and fulfilling lives.

Procedural elements refers to how citizens access environmental rights, such as rights to access environmental information, to participate in environmental decision-making and also the ability to access the justice system ("access to justice"), e.g. the rules on bringing environmental cases in court and the funding of these cases. Central to this is the degree to which Scotland meets the requirements of the UNECE Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters (the 'Aarhus Convention'). This is an international environmental treaty that enshrines procedural environmental rights for members of the public. The United Kingdom is a party to this treaty.

The Aarhus Convention Compliance Committee (a non-judicial body) previously concluded that the United Kingdom (and Scotland, as part of the United Kingdom) is not complying with the Aarhus Convention since access to justice in environmental matters is "prohibitively expensive". The extent to which a legal system allows for affordable public interest litigation, the scope of judicial review procedures, and whether there is a need for specialist environmental courts or other bespoke routes of redress, are common themes to the overall question of ensuring access to justice in environmental matters. In September 2021, the Committee set out a number of issues which it considers require attention in Scotland, including the types of claims covered, court fees and the provision of legal aid.6

Changes to environmental governance due to Brexit, and routes for individuals or civil society groups to seek redress for alleged violations of environmental law led to some consideration of these issues as part of the passing of the UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Continuity) (Scotland) Act 2021. The Scottish Government had consulted on developments in environmental justice in 2017 and considered the question of the need for an environmental court, but concluded that, due to the uncertainty of the environmental justice landscape caused by Brexit, it was not appropriate to set up a specialised environmental court or tribunal at that time. The 2021 Continuity Act includes a requirement for the Scottish Government to consult again on the effectiveness of environmental governance arrangements in Scotland, including the question of the need for an environmental court.

More information and background on the above issues can be found in SPICe briefing 'Human Rights and the Environment' published in 2019.

Important context - the climate and ecological emergencies

An important part of the context to this proposal is that Scotland is currently facing 'twin global crises' of climate change and biodiversity loss (recognised in Scotland's Environment Strategy), which in themselves have the potential to significantly impact on human rights and wellbeing. Government responses (and responses by other actors such as corporations) to those crises, and how costs or actions to address them are distributed across society, also have the potential to impact on human rights. Internationally, for example, there has been a surge in recent years of climate litigation brought by individuals and civil society groups, seeking to use human-rights based arguments to hold state and corporate actors to account for failing to deliver on the promised emission reductions.7

The 2021 report by the National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership recognises that:

The UN has called for all countries to cooperate and prioritise human rights as a vital part of all efforts to build back better from the pandemic, end interference with the natural environment which caused the pandemic and urgently address the underlying climate crisis

Scottish Government. (2021, March 12). National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership Report. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/national-taskforce-human-rights-leadership-report/ [accessed 25 June 2021]

Budgets

The actual impact of the Bill in each policy area will depend to a large degree on the priority which each area is given in the Scottish Government's budget, rather than on the nature of the right itself.

The Taskforce's report recognises this and stresses that budgets, and the prioritisation of financial resources, will be crucial to the success of the project. It states that

The Report’s recommendations are very ambitious and it will take time to fulfil their potential. They will need resources and so we need to decide our priorities, use the maximum resources available and progressively realise such rights

Scottish Government. (2021, March 12). National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership Report. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/national-taskforce-human-rights-leadership-report/ [accessed 25 June 2021]

The report also emphasises that monitoring and scrutinising these budgets will be important, noting that

it will be essential that human rights budget scrutiny and monitoring forms part of the framework implementation

Scottish Government. (2021, March 12). National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership Report. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/national-taskforce-human-rights-leadership-report/ [accessed 25 June 2021]

It also recommends that, as part of the proposed "Human Rights Scheme":

the Scottish Government is required to report on how the new statutory human rights framework has been met during the budget process; and that

affected communities are involved in the making of strategic decisions including budgetary decisions.

The report doesn't include a detailed plan for budget setting or scrutiny and much will depend on how the issue is dealt with in the Bill and accompanying documentation and guidance.