Equalities and Human Rights: Subject Profile

This subject profile provides an overview of the equalities and human rights legislative framework at International, UK and Scottish levels. It also provides an overview of the Scottish Government's legislative and policy approach to advance equalities and human rights.

Summary

This subject profile provides an overview of the equalities and human rights legislative framework at International, UK and Scottish levels. It also provides an overview of the Scottish Government's legislative and policy approach to advance equalities and human rights.

A range of legislation was passed by the Scottish Parliament in Session 5 that broadly aimed to improve equality and human rights for different groups of people. For example, the extension of civil partnerships to mixed sex couples, a legislative objective to increase the number of women on public boards, pardoning men convicted for historical same-sex sexual offences that are now legal, and increasing protections around domestic abuse and Female Genital Mutilation.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (Incorporation) (Scotland) Bill was passed unanimously. However, the UK Government referred the Bill to the UK Supreme Court for a ruling over its legislative competence. There has been no judgment on the case to date.

Over the last Session, the Scottish Government developed policies with the stated goal of improving the lives of a range of people under the broad aim to achieve a Fairer Scotland. These include strategies and action plans on race, disabled people, older people, and women.

However, the evidence indicates that the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated existing inequalities for different groups. Arguably, continuing scrutiny will be required as we recover from the pandemic to help prevent further inequalities.

Other key policy areas include:

Equally Safe - the strategy for preventing and eradicating violence against women and girls.

Gypsy/Traveller Action Plan - to improve the lives of Gypsy/Travellers across housing, education and work, and to tackle discrimination.

New Scots integration strategy - to support the integration of refugees and asylum seekers.

Ending destitution together strategy - this recently launched strategy aims to improve support for people who have no recourse to public funds.

The Scottish Government also has plans to introduce:

A Bill to reform the Gender Recognition Act 2004. The Scottish Government first consulted on reforms in 2017, but the proposals were delayed, firstly to take account of additional issues raised, and secondly because of the impact of COVID-19 pandemic.

A Bill to incorporate four international human rights treaties into Scots law, on economic, social and cultural rights, women, disabled people, and minority ethnic communities. It will also include rights for older people, LGBTI people, and a healthy environment.

Introduction

This briefing provides an overview of the legislative and policy framework on equalities and human rights in Scotland and the UK, with reference to the international and EU context. It briefly considers the impact of Brexit on equality and human rights.

It contains an overview of key areas of policy development in Scotland, as well as in the UK, and considers the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

International human rights framework

The Universal Declaration on Human Rights (UDHR) was adopted in 1948 by the newly formed United Nations. It is generally agreed to be the foundation of international human rights law. Nearly every state in the world has accepted the UDHR.1 It sets out that basic rights and fundamental freedoms are inherent to all human beings who are born ‘free and equal’. These include rights and freedoms such as:

the right to life

the right to own property

the right to freedom of opinion and expression

the right to work and to work in just and favourable conditions

the right to social security

the right to a standard of living adequate for health and well-being

the right to equal protection against any discrimination in violation of the UDHR.

Equality and non-discrimination are core principles of the UDHR.

International Bill of Human Rights

The International Bill of Human Rights is the informal name given to the UDHR, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1966), and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966).

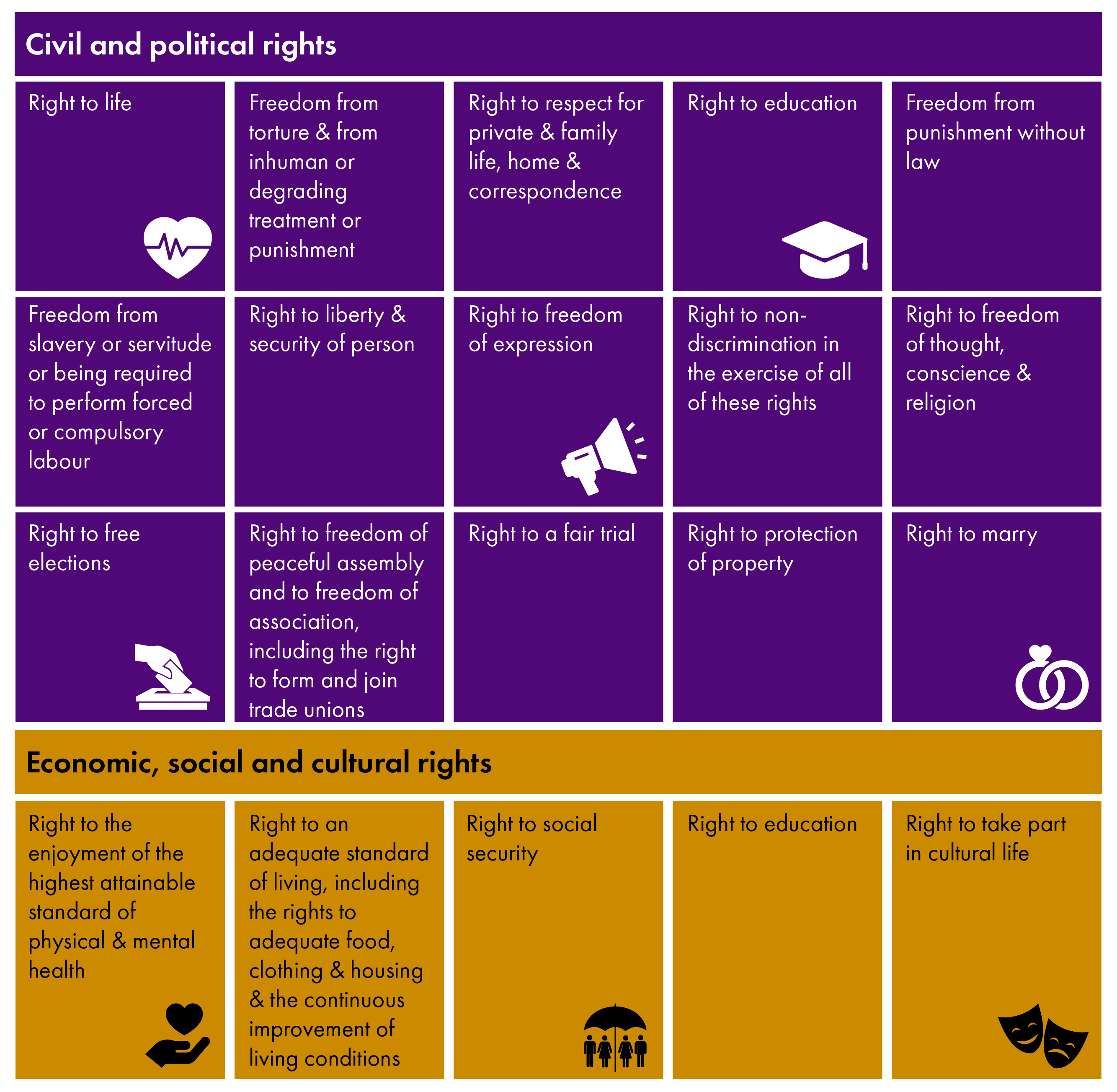

Economic, social and cultural rights include, for example, the right to an adequate standard of living, the right to adequate food, and rights at work. Civil and political rights include, for example, the right to life, freedom from torture, and freedom of expression.

International human rights treaties

After the International Bill of Rights came numerous international treaties for human rights protections. Some of these deal specifically with equality and discrimination:

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (ratified by the UK in 1986)

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ratified by the UK in 1969)

Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (ratified by the UK in 2009).

These treaties each promote rights for specific groups. However, as things stand, none of these UN treaties give individuals legal rights in the UK courts. While the UK Government has pledged to make sure domestic policies comply with the UN treaties, people normally cannot take public bodies to court if their treaty rights are breached in some way. The Scottish Ministerial Code also states that there is an overarching duty on Ministers to comply with the law, including international law and treaty obligations.1 The Scottish Government has proposals to incorporate these treaties.

The Convention on the Rights of the Child (ratified by the UK in 1989), also contains a non-discrimination provision. In Session 5, the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (Incorporation) (Scotland) Bill aimed to incorporate this treaty into Scots law. However, due to a challenge from the UK Government over legislative competence, Royal Assent has been delayed.

Council of Europe

The Council of Europe, formed in 1949 and based in Strasbourg, is made up of 47 member states including the UK. It was set up to promote democracy, human rights and the rule of law in Europe. It is completely separate from the European Union.

All council members must sign up to the European Convention on Human Rights.

The Convention, adopted in 1950, protects a series of civil and political rights. For example, the right to life, right to freedom of expression and the right to respect for private and family life.

Article 14 is concerned with the prohibition of discrimination in respect of other rights and freedoms:

The enjoyment of the rights and freedoms set forth in this Convention shall be secured without discrimination on any ground such as sex, race, colour, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, association with a national minority, property, birth or other status.

Article 14 is not a free-standing guarantee against discrimination, but it can prohibit discrimination in relation to other Convention rights. For example, Article 14 must be used in combination with one or more of the other articles, such as the right to private life.

The European Social Charter, adopted in 1961, is a Council of Europe treaty. It guarantees fundamental social and economic rights as a counterpart to the European Convention on Human Rights, which covers predominantly civil and political rights. It has been revised over the years, and 43 out of the 47 member states are Parties to either the Charter or the Revised Charter1.

Human Rights Act 1998 and Scotland Act 1998

Human Rights Act 1998

The Human Rights Act 1998 largely incorporates the rights contained in the European Convention on Human Rights into domestic UK law so that people can rely directly on the Convention in the UK, for example by bringing cases against public bodies.

The Act requires all legislation to be interpreted and given effect, as far as possible, to be compatible with the Convention rights. The Act makes it unlawful for a public authority to act incompatibly with the Convention rights and allows for a case to be brought in a UK court or tribunal against the authority if it does so.

If a court finds that an Act of the UK Parliament is not compatible with the Convention, it can issue a ‘declaration of incompatibility’. While the UK Parliament may reconsider the legislation, the declaration does not invalidate the Act.

The UK Government launched an independent review of the Human Rights Act on 13 January 2021. It closed on 3 March 2021. The review is examining the framework of the Act, how it is operating in practice and whether any change is required. Over 150 responses were submitted, and are available to view on the review webpage. The Scottish Government responded to the review on 2 March 2021.1 It stated that it has made it clear it would “robustly oppose any attempt to weaken or undermine UK commitment to the Convention, together with any actions which seek to distance the UK from membership of the Council of Europe.”

Scotland Act 1998

The Scotland Act 1998 requires that all Scottish Parliament legislation must be compatible with the rights set out in the Human Rights Act. If a court finds that an Act of the Scottish Parliament is not compatible with the Convention, it has the power to ‘strike down’ the legislation, which means it would no longer be part of Scots law.

A key difference here is that the Scotland Act is stronger when it comes to legislation. Under the Human Rights Act, a court can issue a ‘declaration of incompatibility’ when it finds that an Act of the UK Parliament is not compatible with the Convention, whereas, under the Scotland Act, a court can strike down Scottish legislation. For further background, see the SPICe briefing on Human Rights in Scotland2.

Equality framework

Equality law in the UK, which protects certain groups from discrimination in different settings, has developed incrementally over more than 50 years, since the Race Relations Act 1965.

Equality Act 2010

The Equality Act 2010 (the Equality Act) brought together over 100 separate pieces of legislation into a single Act to create a legal framework which protects the rights of individuals and which advances equality of opportunity for all. The majority of the Act came into force in October 2010 and covers Great Britain. It provides protection against discrimination to nine 'protected characteristics', these are:

age

disability

gender reassignment

marriage and civil partnership

pregnancy and maternity

race

religion or belief

sex

sexual orientation.

The Equality Act provides protection for people with the protected characteristics across employment, education, and goods, services and public functions. However, a limited number of exceptions apply, so it cannot be assumed that all prohibited conduct applies to all protected characteristics in all areas.

| Type of discrimination | What this means |

|---|---|

| Direct discrimination (s.13) | This occurs where someone is treated less favourably than another person, because of a protected characteristic.Some exceptions:

|

| Indirect discrimination (s.19) | This occurs when a policy or practice applied has an effect which particularly disadvantages people with a protected characteristic, unless the policy or practice can be justified. |

| Harassment (s.26) | This is unwanted conduct which has the effect of violating someone's dignity or creates an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment. Harassment also covers unwanted conduct of a sexual nature. |

| Victimisation (s.27) | This occurs where someone is treated badly because they have taken action under the Act, or might be taking action, or are supporting someone who is taking action. |

| Reasonable adjustments (s.20-22) | This is a duty which requires employers, service providers and education providers to make reasonable adjustments to ensure disabled people do not face substantial disadvantage in comparison to someone who is not disabled.The duty has three requirements:

|

| Discrimination arising from disability (s.15) | Makes it unlawful to treat a disabled person unfavourably because of something connected with their disability, where the employer/service provider knows, or could reasonably be expected to know that the person has a disability. Discrimination is unlawful, unless it can be justified. |

Public Sector Equality Duty

Section 149 of the 2010 Act creates a single equality duty for the public sector which incorporates all the protected characteristics, although marriage and civil partnership is only partially covered. The “general equality duty” came into force on 5 April 2011. It requires public authorities, and any organisation carrying out functions of a public nature, to consider the needs of protected groups, for example, when delivering services and in employment practices.

The public sector equality duty requires public bodies to have due regard to the need to:

eliminate discrimination, harassment and victimisation

advance equality of opportunity between different groups

foster good relations between different groups.

Section 153 of the Equality Act gives Ministers in England, Wales and Scotland the power to impose 'specific duties' through regulations. The specific duties are legal requirements designed to help public authorities meet the general duty. Each administration has developed the duty differently.

The Equality Act 2010 (Specific Duties) (Scotland) Regulations 2012 (as amended) came into force on 27 May 2012.1 The Equality and Human Rights Commission in Scotland published a range of guidance to support Scottish public authorities subject to the specific equality duties. Public authorities subject to the specific equality duties are required to:

report on mainstreaming the equality duty

publish equality outcomes and report progress

assess and review policies and practices

gather and use employee information

publish gender pay gap information

publish statements on equal pay

consider award criteria and conditions in relation to public procurement

publish required information in a manner that is accessible.

A further duty is imposed on Scottish Ministers to publish proposals for activity to enable listed authorities to better perform the general equality duty.

The majority of public authorities began reporting in 2013 and publish every 2 years or 4 years depending on the specific duty. Further authorities have been added by regulations, so some report on different timescales.2

Public Sector Equality Duty Review

The Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) published research in 2018 on the effectiveness of the public sector equality duty (PSED) across Great Britain1, and on the specific PSED in Scotland.2 The EHRC in Scotland has also published a series of research on compliance with the specific PSED in Scotland.3

The report on Scotland's experience with the specific PSED found that, overall, there was limited evidence of change for people with protected characteristics. It was possible for public authorities to meet the requirements of the duties "without investing substantially in producing or demonstrating change."2 It made a number of suggestions for improvement, including:

a greater focus on producing change for people with protected characteristics

more consistent application of the available guidance produced by the EHRC

improvements to the quality of data and how it is collected.

The Scottish Government has been committed to reviewing the specific PSED and began work on this in 2018. However, work on this review was delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The review is being conducted in two stages. The first stage is the publication of a report on the effectiveness of the PSED in Scotland, and learns from the experience of COVID-19. This report - 'Review of the Operation of the Public Sector Equality Duty in Scotland: Learning from Mainstreaming Equality during the COVID-19 Pandemic'5 - was published as a supplementary document to the Scottish Government's 'Equality outcomes and mainstreaming: report 2021'.6

The interim conclusions found that the overall framework of a general equality duty, supported by specific duties, is worthwhile and can lead to progress, but the potential has not yet been realised.

The Scottish Government has said that, rather than replace the current regulations, it would be more pragmatic and effective to amend and update them.

The second stage of the review, to take place later in 2021, will involve the development of proposals and consultation on them.

Scotland Act 1998 and 2016

Scotland Act 1998

The subject matter of equal opportunities is reserved by Schedule 5 of the Scotland Act 1998. This currently includes two key pieces of legislation:

The Equality Act 2006 which established the Equality and Human Rights Commission

The Equality Act 2010 which consolidated a vast amount of anti-discrimination legislation including the Equal Pay Act 1970, the Sex Discrimination Act 1975, the Race Relations Act 1976 and the Disability Discrimination Act 1995.

The definition of equal opportunities in the Scotland Act 1998, Schedule 5, Section L2, is:

... the prevention, elimination or regulation of discrimination between persons on grounds of sex or marital status, on racial grounds, or on grounds of disability, age, sexual orientation, language or social origin, or of other personal attributes, including beliefs or opinions such as religious beliefs or political opinions.

The exception to the equal opportunities reservation allows the:

Encouragement (other than by prohibition or regulation) of equal opportunities, and in particular the observance of equal opportunity requirements.

In addition, the Parliament can impose duties on Scottish public bodies and office holders in the Scottish Administration with regard to carrying out their functions with due regard to meeting equal opportunity requirements.

Scotland Act 2016

The Scotland Act 2016, which amends the Scotland Act 1998, devolved further responsibility for ‘equal opportunities’ to the Scottish Parliament. The responsibility commenced on 23 May 2016.

Section 37 of the 2016 Act adds exceptions to the reservation contained in the Scotland Act 1998. The Scottish Parliament is able to:

legislate about equal opportunities in relation to non-executive appointments to the boards of Scottish public authorities. This provision applies to all protected characteristics, and allowed for the Gender Representation on Public Boards (Scotland) Act 2018.

introduce protections and requirements in relation to Scottish functions of Scottish or cross-border public authorities that add to, but do not modify, the existing provisions of the Equality Act 2010.

Section 38 of the 2016 Act covers the public sector duty regarding socio-economic inequalities. It provided a mechanism for the Scottish Government to introduce a socio-economic duty, as set out in Section 1 of the Equality Act 2010:

An authority to which this section applies must, when making decisions of a strategic nature about how to exercise its functions, have due regard to the desirability of exercising them in a way that is designed to reduce the inequalities of outcome which result from socio-economic disadvantage.

Fairer Scotland Duty

The socio-economic duty came into force on 1 April 20181. The Scottish Government re-named it the Fairer Scotland Duty.2

The Fairer Scotland Duty requires certain public authorities to actively consider how they can reduce inequalities of outcome caused by socio-economic disadvantage, when they make strategic decisions. It is subject to a three-year implementation phase, and as such, interim guidance was published to assist public authorities.3

The EHRC is the regulator of the duty, and it published research on how public bodies in Scotland are implementing the socio-economic duty, and on preparations for implementing the duty in Wales (in Wales, the duty came into force on 31 March 2021). There are no plans to introduce the duty in England. For Scotland, the research found:

The duty encouraged public bodies to review and formalise their consideration of socio-economic disadvantage within strategic decision-making processes.

Buy-in from senior management, clear identification as to what constitutes a ‘strategic decision’, and a strong evidence base relating to socio-economic disadvantage, were all identified as necessary for effective implementation in both nations.

Some Scottish public bodies reported that the duty had begun to influence and change the outcomes of decisions. However, several felt that the duty had not yet made any significant changes to the outcome of decisions that had been made, and had not been used to set or tackle specific priorities to date.

Public bodies in Scotland and Wales identified the following to ensure future success and the effective implementation of the duty:

clear success criteria and measures so that the impact of the duty on inequalities of outcomes can be monitored

further guidance and support from governments on data use and consultation with those experiencing socio-economic disadvantage

mechanisms that hold public bodies accountable to the duty

collective responsibility for the duty among all staff members within public bodies

greater focus on changes to outcomes rather than decision-making processes.

Impact of Brexit

The UK's exit from the EU means that there are two high level impacts on equality and human rights:

The UK no longer has to comply with EU Directives on 'equal treatment', as well as directives on employment rights.

The UK no longer has to comply with the Charter of Fundamental Rights.

European Union

Equality between women and men and non-discrimination are common values on which the EU is founded.1

It was the Treaty of Rome, which established the European Community in 1957, that enshrined the principle that ‘men and women should receive equal pay for equal work’ (now Article 157 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU)). In 1997, the Treaty of Amsterdam enabled the Council to take appropriate action to combat discrimination based on sex, racial or ethnic origin, religion or belief, disability, age or sexual orientation (now article 19 of the TFEU).

EU Directives

From these key equality principles a series of 'equal treatment' EU directives have been agreed, which each Member State has to comply with. These have progressively extended the protection against discrimination to more groups and in respect of more areas of life. The directives have either required significant amendments to UK equalities legislation, where there was already domestic law, or required the introduction of completely new domestic law.

Council Directive 2000/43/EC implemented the principle of equal treatment between persons irrespective of racial or ethnic origin. The directive outlaws discrimination on grounds of racial or ethnic origin in the areas of employment, vocational training, goods and services, social protection, education and housing.

Council Directive 2000/78/EC established a general framework for equal treatment in employment and occupation. The directive introduced protection from direct and indirect discrimination in employment in respect of age, disability, religion and belief and sexual orientation.

Council Directive 2004/113/EC implemented the principle of equal treatment between men and women in the access to and supply of goods and services.

Council Directive 2006/54/EC consolidated a number of previous directives and further implemented the principle of equal opportunities and equal treatment of men and women in matters of employment and occupation (consolidated 76/207/EEC, 86/378/EEC and 75/117/EEC, all as amended).

Member states must implement EU directives in domestic legislation. EU law takes precedence over domestic law, which means that all Member States have to ensure their domestic laws comply with the minimum standards set out in directives. States are sometimes free to go further than the provisions, but they cannot do less than a directive requires.

Prior to the UK's withdrawal from the EU, the Equality Act 2010 enabled Ministers to amend UK equalities legislation to ensure consistency where changes are required by European law. The aim was to ensure that areas of the Act which are covered by European law, and those that are domestic in origin, did not get out of step. However, this was repealed by the Equality (Amendment and Revocation) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019/305.

There are also a range of employment directives which no longer apply, covering for example, working time and maternity leave.

When the UK left the EU on 31 January 2021, a snapshot of EU law was taken to become 'retained EU law'. The intention was to provide legal certainty in the UK in the period immediately following EU exit.2 While EU Directives themselves are not retained, the legislation implementing them or rights and obligations under them, are retained.3

The UK and devolved administrations have agreed a number of 'common frameworks' to limit the potential for policy divergence, where EU law has previously provided a common legal framework.4 In some areas, the UK Government and the Scottish and Welsh Governments agree it will be necessary to maintain UK-wide approaches, or common frameworks. This includes the common framework for 'Equal Treatment' legislation.5

The EU Charter of Fundamental Rights

The Lisbon Treaty 2009 brought into force the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. The Charter sets out rights that stem from existing general principles of EU law, but also from common constitutional traditions and international human rights treaties. A broad range of civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights are included; it is broader than the Human Rights Act in terms of scope.

The Charter also prohibits discrimination on "sex, race, colour, ethnic or social origin, genetic features, language, religion or belief, political or any other opinion, membership of a national minority, property, birth, disability, age or sexual orientation."

The Charter is binding on the EU and its institutions, but can also bind EU Member States when they are implementing, derogating from or acting within, the scope of EU law. It can, therefore, have an impact at a national level.

The Scottish Government attempted to retain the Charter in Scots law in its Continuity Bill.6 However, the Supreme Court held that the Scottish Parliament did not have the power to do this as it was an attempt to modify UK legislation (the Withdrawal Act) which expressly stated that the Charter is not part of UK law following Brexit.7

Since the UK's withdrawal from the EU, the Charter no longer applies in the UK. The Equality and Human Rights Commission set out its concerns which arise from the loss of the Charter.8 The overall view is that it leads to a reduction of rights.

However, it is worth noting that interpretation of the Charter and its non-discrimination rules is not without controversy. For example, the European Court of Justice recently ruled that European employers can ban workers from wearing any visible sign of their political, philosophical or religious beliefs if the employer needs to present a neutral image towards customers or to prevent social disputes.9

Partly in response to concerns about reduced rights after Brexit, the First Minister set up the First Minister's Advisory Group on Human Rights Leadership in January 2018. They were asked to "recommend the next steps on Scotland's human rights journey, including finding a way forward in the context of post-Brexit uncertainty."10 This has led to proposals for a new human rights framework in Scotland.

UK Government

Government Equalities Office

The Government Equalities Office (GEO) leads work on policy relating to women, sexual orientation and transgender equality, as well as equalities legislation.

The GEO reports to Liz Truss MP, the Minister for Women and Equalities. Kemi Badenoch MP is the Minister for Equalities, and Baroness Berridge of The Vale of Catmose is the Minister for Women.

The 'Equality Hub', which is part of the Cabinet Office, brings together the work of the GEO and:

UK Government approach to equality

New approach to tackling inequality

On 17 December 2020, Liz Truss set out the UK Government's new approach to tackling inequality across the UK.1 In her 'Fight for Fairness'2 speech Liz Truss defined the UK Government's view of the 'current problem' with the debate around equality in the UK:

Too often, the equality debate has been dominated by a small number of unrepresentative voices, and by those who believe people are defined by their protected characteristic and not by their individual character.

The new approach to equality "will be based on the core principles of freedom, choice, opportunity, and individual humanity and dignity", and a move beyond the "narrow focus of protected characteristics." The intention is to consider socio-economic and geographic based inequality, in addition to the protected characteristics, to "break down barriers to social mobility." To achieve this, a large-scale project was announced - the Equality Data Programme - to better understand the barriers people face across the UK.3

UK Government action on equality

This section highlights some of the key areas where the UK Government has taken action on equality.

Plans to legislate for a ban on conversion therapy

In July 2018, the UK Government said it would “eradicate the abhorrent practice” of LGBT conversion therapy.1 It was based on evidence from the UK Government's self-selecting LGBT survey in 2017.2 This announcement on conversion therapy was UK-wide. However, progress stalled, and there have since been petitions in the UK and Scottish Parliament calling for action.3

A commitment to ban so called conversion therapy was set out in the Queen's speech on 11 May 2021.4 This was followed by a commitment to launch a consultation and then introduce legislation banning conversion therapy in the UK.5

Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities

The Prime Minister established the independent Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities on 16 July 2020, following the Black Lives Matter protests.6

The Commission's report and supporting documents were published on 31 March 2021. It made 24 recommendations in areas including data, education, employment, crime, policing and health.

The report has been controversial and stakeholder reaction to it has been mixed. Some said that the report rightly identified various causes of disparities, while others criticised its position on institutional racism, the veracity of its conclusions and its reference to the slave trade.7

Gender Recognition Reform

The UK Government consulted on reforms to the Gender Recognition Act 2004 between 3 July and 22 October 2018. It received over 100,000 responses.8

After some delay, the UK Government's response to the consultation was published on 22 September 2020. It was decided that the current provisions within the 2004 Act would remain the same, but that the application process would be modernised. To this end, the application fee has now been reduced from £140 to £5 on 4 May 2021, across the UK.9 The Government Equalities Office is also working to move the application process online.

In a ministerial statement10, Liz Truss said:

It is the Government's view that the balance struck in this legislation is correct, in that there are proper checks and balances in the system and also support for people who want to change their legal sex.

The focus was moved towards trans healthcare:

We have also come to understand that gender recognition reform, though supported in the consultation undertaken by the last government, is not the top priority for transgender people. Perhaps their most important concern is the state of trans healthcare. Trans people tell us that waiting lists at NHS gender clinics are too long. I agree, and I am deeply concerned at the distress it can cause.

The independent analysis of the consultation reported:11

Trans respondents overwhelmingly reported that the current gender recognition process was too bureaucratic, time-consuming and expensive, highlighting in particular that the process made them feel dehumanised and stressed.

When asked about what having a Gender Recognition Certificate (GRC) would mean to them, many trans people talked about the social and legal validation they would gain through an updated birth certificate. The lack of recognition of those identifying as non-binary was frequently raised.

Nearly two-thirds of respondents (64.1%) said that there should not be a requirement for a diagnosis of gender dysphoria in the future, with just over a third (35.9%) saying that this requirement should be retained.

Around 4 in 5 (80.3%) respondents were in favour of removing the requirement for a medical report which details all treatment received.

A majority of respondents (78.6%) were in favour of removing the requirement for individuals to provide evidence of having lived in their acquired gender for a period of time.

The Women and Equalities Committee launched an inquiry on 28 October 2020 on whether the UK Government's proposals are the right ones and whether they go far enough.

COVID-19 disparities

On 2 June 2020, Public Health England (PHE) published a descriptive review of data on disparities in the risk and outcomes from COVID-19. 12 The review confirmed that the impact of COVID-19 had replicated existing health inequalities, and in some cases, had increased them.

The review reported that the risk of dying among those diagnosed with COVID-19 was higher in Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic groups than in White ethnic groups. Before COVID-19, the mortality rate was higher in White ethnic groups than in Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic groups.

To support this work, PHE engaged more than 4,000 people who represent the views of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic communities, to gather insights into factors that may be influencing the impact of COVID-19 on these groups and to find potential solutions. PHE published a summary of stakeholder insights into factors affecting the impact of COVID-19 on Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic Communities on 16 June 2020.13

Following the PHE review, the UK Government announced on 4 June 2020 that the Government's Equality Hub, led by the Equalities Minister, Kemi Badenoch MP, would take work forward to "understand the key drivers of the disparities identified and the relationships between the different risk factors." This would include work to consider the effectiveness and impact of current actions being taken to lessen disparities in COVID-19 infection rates and deaths. Three of four quarterly reports have now been published.14

UK Parliament

There are two separate committees at Westminster which focus on 'women and equalities' and 'human rights'. They have each dedicated much of their work programme in the past year to the impact of the Coronavirus pandemic. They have focused on the impact on specific groups of people, and more broadly on the implications for human rights.

Women and Equalities Committee

The Women and Equalities Committee examines the work of the Government Equalities Office (GEO). It holds Government to account on equality law and policy, including the Equality Act 2010 and cross-Government activity on equalities. It also scrutinises the Equality and Human Rights Commission.

The Committee has 11 cross-party Members and is currently chaired by Caroline Noakes MP.

The Committee has taken a keen interest in the impact of Coronavirus on different equality groups. It launched an inquiry in March 2020, and has since focused in more detail on the impact of the pandemic on women, disabled people, and ethnic minority people.

Its recent inquiry reports include:

Unequal impact? Coronavirus and the gendered economic impact

Unequal impact? Coronavirus, disability and access to services

Current inquiries include:

Joint Committee on Human Rights

The Joint Committee on Human Rights has members appointed from the House of Commons and House of Lords. It examines matters relating to human rights within the UK, as well as scrutinising every Government Bill for its compatibility with human rights.

The Committee has 12 cross-party Members and is chaired by Harriet Harman QC MP.

The Committee has taken a keen interest in the UK Government's response to COVID-19 and the implications this has for human rights.

Its recent inquiry reports include:

The Government's response to COVID-19: human rights implications

The Government's response to COVID-19: human rights implications of long lockdown

Current inquiries include:

Equality and Human Rights Commission

The Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) was established under the Equality Act 2006 and is responsible to the UK Government. It is a regulatory body responsible for enforcing the Equality Act 2010. It is accredited as an ‘A Status’ National Human Rights Institution and monitors the UK's compliance with the seven UN human rights treaties it has signed and ratified.

The EHRC has powers to:

Enforce equality law – by providing advice and information, as well as taking, supporting or intervening in legal cases on behalf of individuals, and taking legal action to prevent breaches of the Human Rights Act 1998 where Article 14 is engaged. It also has the power to launch official inquiries and formal investigations.

Shape public policy – by working to influence the Government to develop equality and human rights legislation; ensuring social policy considers the importance of equality and human rights; and, commissioning, assessing and publishing research to build a source of evidence-based knowledge.

Promote good practice – by working with public, private and voluntary organisations and employers to reduce discrimination, develop good practice and promote equality for all.

EHRC in Scotland

Although it is a ‘reserved’ body, the EHRC in Scotland works with the Scottish Government and other partners to promote equality and best practice. The Commission in Scotland:

provides information and advice

campaigns on equality issues

seeks to influence legislation and policy

supports key legal cases.

The EHRC also has responsibility for human rights in Scotland in relation to reserved policy areas (such as immigration). Human rights in relation to devolved areas (such as the police) is the responsibility of the Scottish Human Rights Commission. In practice, the two areas are often interwoven.

The Scotland Committee is responsible for ensuring the overall work of the Commission reflects the needs and priorities of Scotland. The Committee sets strategic direction and steers the Commission's work in Scotland.

Scottish Human Rights Commission

The Scottish Human Rights Commission (SHRC) was established under the Scottish Commission for Human Rights Act 2006, and is accountable to the people of Scotland, through the Scottish Parliament. The Commission is accredited as an ‘A Status’ National Human Rights Institution within the United Nations system.

The SHRC has a general duty to promote awareness, understanding and respect for all human rights, anywhere in Scotland. It has powers to recommend changes to law, policy and practice; and promote human rights through education, training and publishing research.

The Commission also has the powers to:

conduct inquiries into the policies or practices of Scottish public authorities

enter some places of detention as part of an inquiry

intervene in civil court cases where relevant to the promotion of human rights and where the case appears to raise a matter of public interest.

Further powers were given to the SHRC under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (Incorporation) (Scotland) Bill ('the UNCRC Bill') (as passed). The SHRC were given the power to bring proceedings under the Act (when in force) in respect of UNCRC requirements, and to intervene in proceedings where a person claims a public authority has acted incompatibility with UNCRC requirements. The Bill is not yet in force because the UK Government referred the Bill to the Supreme Court over its legislative competence. The hearing took place on 28 and 29 June 2021; there has been no judgment to date.1

Scottish Government

Equality and human rights mainstreaming

The Scottish Government's Programme for Government 2020-21 said that it was "putting equality and human rights at the heart of our approach." To this end, it will develop an equality and human rights and mainstreaming strategy.1

To help take this commitment forward, a new Directorate of Equality, Inclusion and Human Rights has been created, which became operational, following the appointment of a new Director, at the end of 2020.2

The new directorate will focus on using data and lived experience to improve outcomes and challenge us when a policy is not working. It will also develop our approach to service design, ensuring our health, education, justice, housing and social security services work for the benefit of everyone in Scotland.2

The impacts of COVID-19 have been experienced "disproportionally by different groups, including women, those from minority ethnic communities, older people and disabled people", so the strategy will also aim to address this.1

The most recent Equality and Outcomes Mainstreaming Report 2021 provides an update on progress incorporating equality across Scottish Government activities, both in terms of policy and as an employer.2

National Performance Framework

The National Performance Framework (NPF) was first established by the Scottish Government in 2007. The NPF sets out the Scottish Government's strategic aims for Scotland and measures progress against a range of outcomes. Ministers are required to review the National Outcomes every five years. It is described as a "wellbeing framework, showing the country we want to be."1

The NPF has 11 National Outcomes aligned with 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals. One of the National Outcomes is to "respect, protect and fulfil human rights and live free from discrimination." The vision for this outcome states:

We recognise the fundamental equality of all humans and strive to reflect this in our day to day functioning as a nation. We stand together to challenge unfairness and our equalities legislation, law and practice are world leading. We uphold human rights, democracy and the rule of law, and our justice systems are proportionate, fair and effective. We provide the care people need with love, understanding and dignity. We have robust, independent means to hold government to account and take an active interest in politics and civic life.2

A recent report describes the impact of COVID-19 on National Outcomes.1 The main conclusions are:

The pandemic has had significant and wide-ranging impact across the National Outcomes, and these are largely negative, particularly in terms of health, economy, fair work and business, and culture outcomes. Progress across the NPF has been hindered and in some cases deeply set back.

COVID-19 impacts have been (and are likely to continue to be) borne unequally, are expected to widen many existing inequalities and produce disproportionate impacts for some groups that already face particular challenges.

However, it also highlights some positive impacts and potentially positive future developments that may result from experiences during the pandemic.

Equality and human rights in the Budget process

A key example of mainstreaming by the Scottish Government is the Equality Statement published alongside the Draft Budget.

The first Equality Statement was published in 2009 for the 2010-11 draft Budget1, and the annual document has evolved over time. While it has been welcomed by equality organisations, it has faced some criticism for focusing too much on the positives, rather than considering the impact of Budget reductions.2

During Session 5, there has been an increasing focus on human rights budgeting. This builds on recommendations from the Equalities and Human Rights Committee3, the work of the First Minister's Advisory Group on Human Rights Leadership, and the Scottish Human Rights Commission.4

The latest version, now called the Equality and Fairer Scotland Budget Statement, is presented differently to previous Equality (and Fairer Scotland) Budget Statements.5 In response to a recommendation from the Equalities and Human Rights Committee,6 it sets out ten key existing or emerging risks to progressing national outcomes as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and Brexit. It also considers how policy and activity funded by the 2021-22 Scottish Budget will respond to those challenges.

The ten key existing or emerging risks are:

Heightened risk that existing structural inequalities in the labour market will be entrenched and worsened.

Elevated risk of poorer labour market outcomes and disproportionate impacts on young people due to COVID-19.

Risk that women's unfair responsibility for unpaid care and domestic work might get worse and reduce their ability to find paid work and income.

COVID-19 mortality and health inequalities.

Drug and alcohol deaths remain unacceptably high with the impact of COVID-19 unclear.

High and rising mental health problems made worse by COVID-19.

As work, public service and home schooling moved online, it highlighted a real digital divide.

Risk that economic impacts and decisions about Universal Credit could increase poverty and particularly child poverty.

Risk that gaps in attainment and skills levels will have been made worse by periods of blended and virtual learning.

Evidence of rising levels of domestic abuse and reporting of sexual abuse crimes against women and children as well as risk of rising hate crime due to COVID-19 and EU Exit.

For each of these risks, the Equality and Fairer Scotland Budget Statement considers:

what does the evidence tell us about the problem?

what the evidence gaps are

what the policy and budget response is for 2021-22

how it is working to close the evidence gap.

For further background, see SPICe blog on "Ten key risks for equalities?"7

Equality Budget Advisory Group

The Equality Budget Advisory Group (EBAG) helps shape the Scottish Government's equality and human rights approach to the budget.

EBAG has recently published recommendations for equality and human rights budgeting in the 2021-2026 parliamentary session. 8

Expenditure on equalities and human rights projects

There is a specific budget line for 'promoting equalities and human rights' which supports the equality and human rights infrastructure across Scotland. This support includes:

investment in the capacity of equality organisations

strategic interventions to support equality outcomes

specific funds to support frontline activities to address violence against women and to support activities to promote equality and human rights.

In the Scottish Budget 2020-21, the Scottish Government indicated that the budget line had increased to £30.2 million in the Scottish Budget 2020-21, and that this will be increased by a further 6% to £32.2 million for the 2021-22 budget.9

In response to the Equalities and Human Rights Committee's pre-budget scrutiny,10 the Scottish Government said:

In this exceptionally challenging year the budget prioritised support for those most at risk from the pandemic, extending existing funding streams to provide clarity and consistency to our funded organisations and enable them to provide flexible support to communities. In 2021-22, we will deliver streamlined funding streams – Delivering Equally Safe and Embedding Equality and Human Rights – that will more closely align our funding with the National Performance Framework outcomes, in line with the Committee's recommendations, and will encourage and support partnership working to tackle some of the more entrenched issues of inequality across our society.9

The Scottish Government has recently announced specific funding for:

Equality data

Equality data is key to the performance of the Public Sector Equality Duty. However there have long been gaps in the available data. To this end, the Scottish Government made a commitment in its Programme for Government 2021-22 to develop a comprehensive approach to improving data collation and analysis to support its mainstreaming strategy.1

A key resource of equality data is the Equality Evidence Finder, which provides the latest data across equality groups by policy area.

Other resources include:

The Gender Equality Index, published in December 2020.2 It measures progress towards gender equality in Scotland, across a range of indicators, covering work, money, time, knowledge, power, health, and violence against women.

Impacts of COVID-19 on different groups, focusing on the health and social impact,3 and the economic impact of labour market effects.4

The Scottish Government also established a working group on sex and gender in data. This was in response to wider concerns about the conflation of sex and gender in data. The working group published draft guidance for stakeholder feedback in December 2020.5

Action on equalities and human rights

This section briefly highlights key Scottish Government action taken to advance equalities and human rights in Session 5, and plans for the future.

Legislation passed

The Scottish Government introduced a range of legislation that aims to advance and promote equalities and human rights:

Commencement of the socio-economic duty in the Equality Act 2010, re-named the Fairer Scotland Duty by the Scottish Government.

The Civil Partnership (Scotland) Act 2020 extended civil partnerships to mixed-sex couples. The first mixed-sex civil partnerships were able to take place from 30 June 2021.1 This now means that all couples in Scotland can choose to get married or form a civil partnership.

The Gender Representation on Public Boards (Scotland) Act 2018 introduced the 'gender representation objective' - a target that women should make up 50% of non-executive board membership. It came into force on 29 May 2020, and there is statutory guidance to support public authorities.2 The definition of 'women' in the Act includes trans women, for the purposes of the Act. This was challenged in a judicial review with the Scottish Government being found to have acted lawfully.3

The Female Genital Mutilation (Protection and Guidance) (Scotland) Act 2020 provides for FGM Protection Orders. These are a form of civil order that can impose conditions or requirements on a person, with the aim of protecting a person from FGM, safeguarding them from harm if FGM has already happened, or reducing the likelihood that FGM offences will happen. It will be a criminal offence to breach an FGM Protection Order. The Act also provides for statutory guidance in such matters. The Act is not yet fully in force.

The aim of the Historical Sexual Offences (Pardons and Disregards) (Scotland) Act 2018 is to provide a form of redress against the discriminatory effect of convicting men for same-sex sexual offences in the past, for activity that is now legal. It introduced a pardon for those convicted of criminal offences for engaging in same-sex sexual activity which is now legal. It also put in place a system to enable a person with such a conviction to apply to have it “disregarded” so that information about that conviction held in records, does not show up in a disclosure check. The pardon scheme opened on 15 October 2019.4

The Census (Amendment) (Scotland) Act 2019 amends the Census Act 1920 to allow questions on sexual orientation and transgender status to be answered on a voluntary basis. This will be the first time the census has asked questions on sexual orientation and transgender status. Scotland's Census was due to take place in March 2021, but has been delayed for a year due to the COVID-19 pandemic.5

The Domestic Abuse (Scotland) Act 2018 came into force on 1 April 2019 and criminalises psychological domestic abuse and coercive and controlling behaviour. The Domestic Abuse (Protection) (Scotland) Act 2021 aims to better protect people at risk of domestic abuse by introducing new powers for the police, the courts and social landlords. The Act is not yet fully in force.

The Hate Crime and Public Order (Scotland) Act 2021 aims to provide greater protection to victims of hate crime, based on a range of characteristics. It modernises and consolidates existing hate crime law. Critics argued that aspects of the Bill infringe on freedom of expression. Amendments were made during the passage of the Bill to address these concerns.6 The Act is not yet fully in force.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (Incorporation) (Scotland) Bill will incorporate the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) into Scots law.7 The Bill was passed unanimously on 16 March 2021.8 However, the Secretary of State for Scotland wrote to the Deputy First Minister on 24 March expressing concerns that the Bill would affect the UK Parliament in its power to make laws for Scotland, “which would be contrary to the devolution settlement”.9 The UK Government referred the Bill to the UK Supreme Court for a ruling on this point. The hearing took place on 28 and 29 June; there has been no judgment yet.10

The Scottish Government also supported two Members' Bills:

the Children (Equal Protection from Assault) (Scotland) Act 2019, introduced by John Finnie MSP, provides children with equal protection from assault by abolishing the defence of 'reasonable chastisement'. This means that a parent (and others caring for or in charge of children) charged with the assault of a child will no longer have the defence, in either criminal or civil proceedings, that the use of force constituted 'reasonable chastisement' or 'justifiable assault'. The Act came into force on 7 November 2020.

the Period Products (Free Provision) (Scotland) Act 2021, introduced by Monica Lennon MSP, places duties on local authorities and education providers to ensure that period products are available free of charge for anyone who needs them. The Act is due to come into force within two years of Royal Assent, which was on 12 January 2021.

Future legislation

It is likely that the Scottish Government will introduce legislation to reform the Gender Recognition Act 2004, and to incorporate international human rights treaties into Scots law.

Gender Recognition Act Reform

The Scottish Government first consulted on changes to the Gender Recognition Act 2004 (GRA) in 2017.1 The GRA provides a way for trans people, aged 18 or older, to apply for legal recognition in their acquired gender. The Scottish Government's view was that applicants for legal gender recognition should no longer need medical evidence or evidence of living in their acquired gender for a defined period. In addition, the minimum age should be reduced to 16. It proposed to bring forward legislation to introduce a self-declaration system for legal gender recognition. The consultation also sought views on the recognition of non-binary people.

A majority of respondents, 60%, agreed with:

the proposal to introduce a self-declaratory system for legal gender recognition

the proposal that the minimum age should be reduced to 16

the recognition of non-binary people.

Despite this support, reform was delayed. On 20 June 2019, the Cabinet Secretary for Social Security and Older People, Shirley-Anne Somerville MSP, made a statement in the Scottish Parliament.2 She stated that additional issues had been raised since the consultation, and that she sought to build consensus on the way forward. These additional issues related to concerns that the reforms could pose a threat to women's safety in single-sex spaces, where predatory men might seek to gain access.

There were also wider concerns about the perceived conflation of sex and gender, and guidance for schools on supporting transgender young people.3 To this end, the Scottish Government:

established a working group on sex and gender in data. The working group published draft guidance for stakeholder feedback in December 2020.4

recently published guidance for schools on Supporting Transgender Young People. 5This revises previous guidance for schools published by LGBT Youth Scotland.

A consultation on a draft Bill ran between 17 December 2019 and 17 March 2020.6 The draft Bill includes provisions for a system of self-declaration of legal gender recognition and reducing the minimum age for application from 18 to 16. It does not include legal gender recognition of non-binary people; instead a working group has been established to identify other ways to improve equality for non-binary people.

However, on 1 April 2020, it was announced that the draft Bill, along with a number of other bills, would be delayed due to the impact of COVID-19. Around 17,000 responses have been received. The consultation analysis has been impacted by COVID-19 and the intention is to publish it as ‘soon as practicable’ in this parliamentary session.7

There has been no announcement to date regarding introduction of the Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill.

Human Rights Bill

The Scottish Government announced on 12 March 2021 that, subject to the outcome of the election, a new Human Rights Bill will be introduced in Session 6.8 The aim is to introduce a new human rights framework for Scotland. This is based on recommendations from the National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership.

The Bill will:

re-state the rights in the Human Rights Act 1998

incorporate rights of four United Nations Human Rights treaties into Scots Law, subject to devolved competence:

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women

Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination

and include rights for:

older people

LGBTI people

a healthy environment.

There is no specific UN Treaty on these rights.

The approach has been developed in response to the impact of Brexit, where the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights no longer applies, and also in response to concerns that the UK Government might replace or amend the Human Rights Act. Both the Charter and Human Rights Act were described by the First Minister's Advisory Group on Human Rights Leadership (the precursor to the National Advisory Group) as the two pillars of human rights protection in Scotland.9

The National Taskforce recommended the direct incorporation of four UN treaties and additional rights into one single bill. This builds on the approach used in the UNCRC Bill which incorporates children's rights into Scots law. The subject matter of the four treaties is broad, including, for example, economics, health, housing, culture, and rights for disabled people, women, and minority ethnic people. There will also be additional rights to consider for older people, LGBTI people, and the right to a healthy environment. This is likely to be a complex Bill which impacts on a wide range of policy areas.

Future plans on equalities and human rights

The Scottish Government has a range of action plans and strategies to advance equalities and human rights.

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected everyone. However, the impacts have affected different groups of people disproportionally, in particular, women, people from minority ethnic communities, older people, disabled people, and those who share a number of characteristics, often with deprivation as an additional aggravating factor.1 Existing inequalities have been exacerbated by the pandemic.2

The Scottish Government has published a series of reports and slides looking at the impact of COVID-19 on different groups, including a review of the evidence on the impact on equality across a range of policy areas.3

In response to reports, both at UK and international level, that some minority ethnic groups may be at risk of a disproportionate impact from the pandemic, the Scottish Government established the Expert Reference Group on COVID-19 and Ethnicity (ERG). The ERG made recommendations in September 2020. 4 These were provided in two reports, respectively focusing on:

the data and evidence in relation to COVID-19 and race5

systemic issues and risk in relation to COVID-19 and race.6

The Scottish Government responded to the ERG in November 2020.7 The Scottish Government is considering "how the findings from this report will inform our thinking as we move forward."1

During the response to the COVID-19 pandemic, a significant amount of work was undertaken to support people and communities. This was delivered at pace and challenged traditional ways of working. The Social Renewal Advisory Board (SRAB) was established to build on this experience and tasked with considering how Scotland could emerge from the pandemic, "whilst ensuring reducing poverty and disadvantage, embedding a human-rights based approach and advancing equality was at the heart."9

The SRAB reported in January 2021 and made 20 ‘calls to action’ structured around three themes:10

Money and Work – everyone should have a basic level of income from employment and social security.

People, Rights and Advancing Equality – everyone should see their rights realised and have access to a range of basic rights, goods and services.

Communities and Collective Endeavour – "we believe that we need to work together to deliver a fairer society and we need to give more power to people and communities and empower frontline teams."

The Scottish Government is considering SRAB's advice.1

The Race Equality Framework 2016 - 201312 and subsequent Race Equality Action Plan13 outlined more than 120 actions to secure better outcomes for minority ethnic communities in Scotland. These actions focused on employment, education, health, housing, poverty, community cohesion, participation and representation.

After hearing from stakeholders about the slow progress on the Race Equality Action Plan, the Equalities and Human Rights Committee conducted an inquiry on Race Equality, Employment and Skills. The inquiry focused on progress in the public sector and the Committee's report made a number of recommendations, including that more needs to be done to reduce the ethnicity pay gap and occupational segregation, and that Chief Executives and senior leaders within public authorities must demonstrate leadership in this area.14

A final report on the action plan was published in March 2021, which provides an update on progress, as well as highlighting action taken to tackle race inequality in response to COVID-19.15 It also set out details on future action.

The Scottish Government will continue its work on race equality. This will include implementing the recommendations from the Expert Reference Group on COVID-19 and Ethnicity (ERG). There are also plans to publish an 18 month "bridging plan" for 2021-2022. The aim is to balance immediate action and longer-term structural change, particularly in light of COVID-19 and the new role of the ERG.

The Gypsy Traveller Action Plan 2019-2021,16 published jointly with COSLA, is focused on improving Gypsy/Traveller lives across housing, health, education, work, representation, and tackling discrimination. The final report of the Race Equality Action Plan said that the proposed "bridging plan" for 2021-22 "aims to coincide with a proposed 18-month extension to deliver on the actions set out in the Gypsy Traveller Action Plan."15

The New Scots integration strategy 2018-2022 sets out “an approach to support a vision of a welcoming Scotland”. The key principle is that integration begins from day one of arrival, and not just when leave to remain has been granted.18

The Scottish Government recently launched its strategy to improve support for people with No Recourse to Public Funds (NRPF) living in Scotland – Ending destitution together: strategy.19 The anti-destitution strategy is in response to the Equalities and Human Rights Committee report on its inquiry into asylum and insecure immigration.20 The key recommendation for the Scottish Government was for the creation of an anti-destitution strategy to mitigate destitution.

A Fairer Scotland for Disabled People 2016-2021 is the Scottish Government's delivery plan for the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD).21 It sets out five ambitions to improve independent living, employment, participation, accessibility, and protected rights, and 93 actions.

A progress report was published in 2019.22 This will form the basis of a further report in 2021 which will provide a more detailed account of the progress on each of the 93 actions.23

A Fairer Scotland for Disabled People: Employment Action Plan was published in December 2018.24 This sets out actions to meet the ambition to at least halve the disability employment gap by 2038. The first Annual Progress Report of the Employment Action Plan was published in March 2020.25

A Fairer Scotland for Older People – A Framework for Action was published in April 2019. It sets out the priority areas to deliver better outcomes for older people. These include: access to public services, health and social care, employment, financial security, and housing. A progress report was due to be published in April 2020, but has been rescheduled due to the impact of the pandemic.23

Equally Safe is the Scottish Government's strategy for preventing and eradicating violence against women and girls. It has a delivery plan, published in 2017,27 and a final report, published in November 2020.28 The final report refers to discussion with stakeholders on the future direction of the strategy, by the end of 2020, before taking forward further engagement throughout 2021.

The Scottish Government conducted a consultation on how to challenge men's demand for prostitution (Sept – Dec 2020).29 The consultation analysis and Scottish Government response were published on 16 June 2021.3031The Scottish Government will now consider how aspects of international approaches which seek to challenge men's demand for prostitution would best be applied in Scotland. This will include listening to those with lived experience.

The Fairer Scotland for women: gender pay gap action plan, published in 2019, sets out a list of actions to address the gender pay gap.32

The First Minister's National Advisory Council on Women and Girls (NACWG) was established in 2017. The Council looks at different topics on an annual basis, and can make recommendations to the First Minister. The third report, published in 2020, makes recommendations to improve leadership and accountability across the Scottish Government and the Scottish Parliament.33

The Working Group on Misogyny and Criminal Justice in Scotland was set up to consider how the Scottish criminal justice system deals with misogyny.34 This includes looking at whether there are gaps in the law that could be addressed by a specific criminal offence to tackle such behaviour.

The group will also consider whether a statutory aggravation and/or a stirring up of hatred offence in relation to the characteristic of sex should be added to the Hate Crime and Public Order (Scotland) legislation by regulation at a future date. It held its first meeting on 12 February 2021, and has to report its findings to the Scottish Government within 12 months.

The Working Group on Non-Binary Equality was set up in January 2020. Work of the group was put on hold due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but restarted in February 2021.35 As announced by the Cabinet Secretary for Social Security and Older People in June 2019, the Scottish Government does not intend to extend legal gender recognition to non-binary people.36 However this group will seek to strengthen and improve equality for non-binary people in Scotland.

Scottish Parliament

In 1998, the Consultative Steering Group (CSG) made recommendations on the operation and rules of procedure of the Scottish Parliament. The CSG placed a strong emphasis on the need for the Scottish Parliament to promote equal opportunities for all, and that equal opportunities should be mainstreamed into the work of the Parliament. It also recommended the establishment of the Equal Opportunities Committee as a mandatory committee. 1

Equalities and Human Rights Committee

The Session 5 Equalities and Human Rights Committee published a legacy report on 24 March 2021. This report summarises its work over the five years of Session 5 and highlights outstanding issues for its successor Committee.1

As well as scrutinising seven Bills, the Committee undertook a range of inquiries and made a number of recommendations for the successor committee, including:

COVID-19 and the impact on equalities and human rights - to prioritise scrutiny on post COVID-19 recovery, with close attention to ensure the issues, challenges and barriers, already faced by different groups, are not further exacerbated.

Destitution, asylum and insecure immigration status - to continue work with the Local Government and Communities’ successor committee to follow up work in this area, particularly in light of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and Brexit in the next session.

Getting Rights Right: The Scottish Parliament and Human Rights - members of the successor committee should receive in-depth training on human rights to enable them to continue to show leadership on human rights in the Parliament. They should monitor proposals to incorporate international human rights treaties into Scots law.

Race Equality, Employment and Skills - consistent monitoring of the Scottish Government's progress on race equality in Scotland.

Gypsy/Travellers - keep a focus on this area by monitoring the implementation of the Scottish Government and COSLA's action plan to ensure it impacts positively on the lives of Gypsy/Travellers in Scotland.

The Committee also made recommendations to:

continue developing the approach on equalities and human rights budget scrutiny

monitor developments in the Scottish Government's review of Public Sector Equality Duty.

The Committee carried forward two public petitions:

Equalities, Human Rights and Civil Justice Committee

The new Equalities, Human Rights and Civil Justice Committee is the successor to the Equalities and Human Rights Committee.

Its remit has been expanded to include civil justice. The remit of the committee was previously expanded at the start of Session 5 to include human rights.1

The Committee had its first meeting on 23 June 2021; Joe FitzPatrick MSP was elected as Convener, and Maggie Chapman as Deputy Convener.

This was followed by the launch of a call for views on Petition PE187 to end conversion therapy, on 6 July (closed 13 August 2021). The petition calls on the Scottish Parliament “to urge the Scottish Government to ban the provision or promotion of LGBT+ conversion therapy in Scotland.”