Human Rights and the Environment

This briefing considers the recommendation by the First Minster's Advisory Group on Human Rights Leadership that a new human rights framework for Scotland should include "a right to a healthy environment". The briefing describes human rights and environmental law in Scotland as well as international examples where environmental rights have been enshrined in law. The briefing then explores access to justice in environmental matters and how human rights can be integrated into environment-related policy.

Executive Summary

The First Minister's Advisory Group on Human Rights Leadership recommended that a new human rights framework for Scotland should include a "right to a healthy environment". Recognising the human right to a healthy environment in constitutions is a common practice around the world. Over 100 countries have a constitutional right to a healthy environment. The previous and present United Nations Special Rapporteurs on Human Rights and the Environment have called for the recognition of the right to a healthy environment in a global human rights instrument.

Human rights and the state of the environment are interdependent. Human rights depend on a healthy environment; and appropriate environmental governance requires respect for human rights. The Scotland Act 1998 requires all public authorities in Scotland to act in accordance with the European Convention on Human Rights and respect international obligations found in the UN Core Human Rights Treaties.

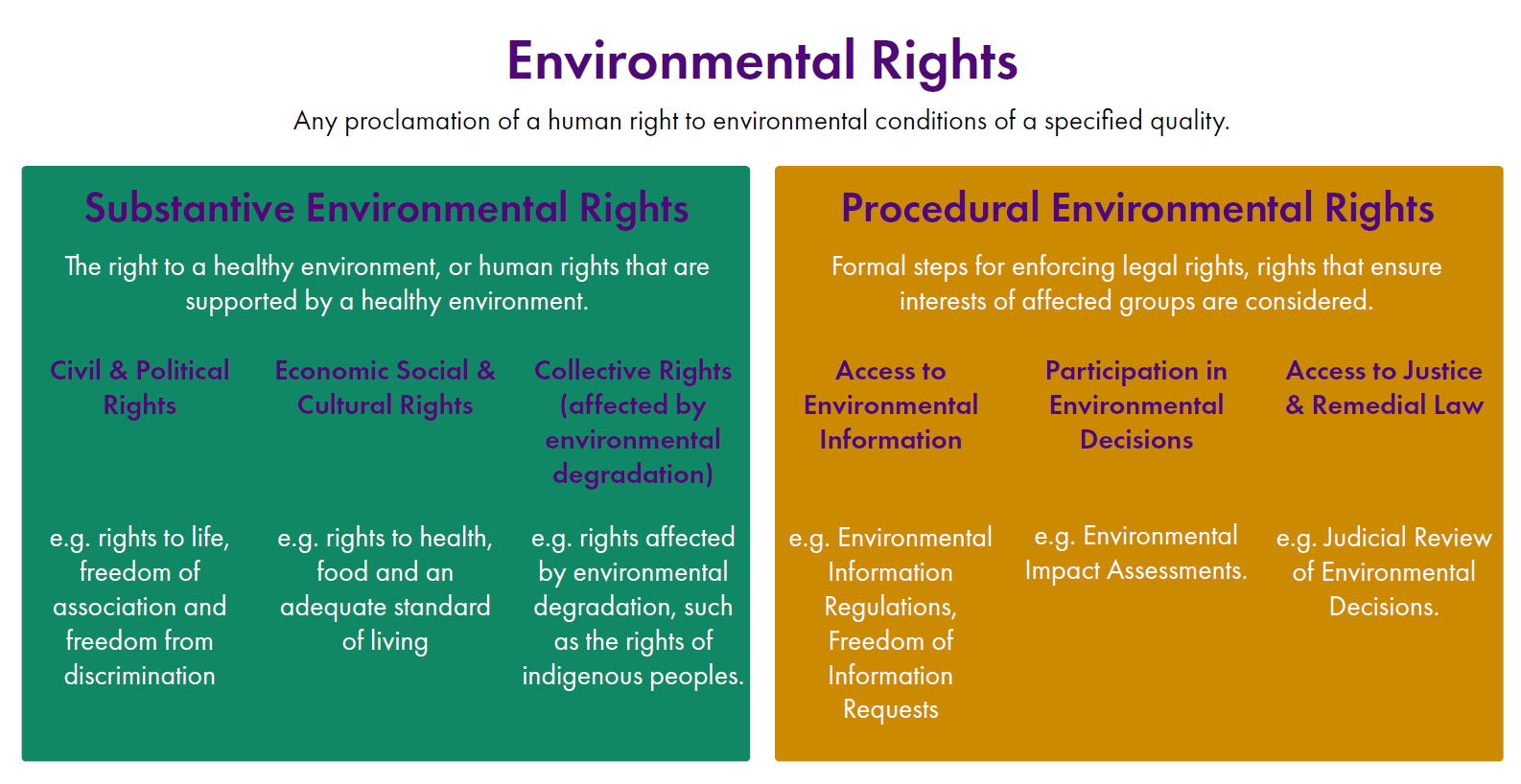

Environmental rights can be broadly categorised into substantive and procedural and rights:

Substantive rights depend on a healthy environment for their enjoyment (e.g. right to life, right to an adequate standard of living).

Procedural rights refer to the formal steps for enforcing legal rights, such as rights to access environmental information, participation in environmental decision-making and access to justice in environmental matters.

The Aarhus Convention is an international environmental treaty that enshrines procedural environmental rights for members of the public. The United Kingdom is a party to this treaty. The Aarhus Convention is independent of European Union membership and will continue to apply to the United Kingdom in the event of an EU exit. However, the loss of EU oversight structures will reduce number of available routes for environmental redress and may impact the enforceability of procedural environmental rights.

The Aarhus Convention Compliance Committee have concluded the United Kingdom (and Scotland, as part of the United Kingdom) is non-compliant with the Aarhus Convention on the basis that access to justice in environmental matters is "prohibitively expensive". Environmental harms tends to be diffuse in nature and often affects groups rather than individuals. Consequently, resolving environmental harm may require technical or scientific expertise. Therefore, the extent to which a legal system allows for affordable public interest litigation and specialist environmental courts as a route of redress is integral to the question of ensuring access to justice in environmental matters.

Environmental challenges such as climate change and biodiversity loss threaten the enjoyment of human rights in Scotland and around the world. The UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment has laid out States' substantive and procedural obligations relating to climate change and biodiversity loss.

Human rights based approaches to environment-related policy can resolve perceived conflicts between interests and rights. For example, by reconciling present generations' rights to livelihood and intergenerational rights to environment protection. Similarly, in the context of land reform, place and community-based approaches may improve sustainable development and conservation in Scotland.

National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership: The Right to a Healthy Environment in Scots Law?

Recognising environmental rights in law is an increasingly widespread practice worldwide.1 On 10 December 2018, The First Minister's Advisory Group on Human Rights Leadership recommended that a new human rights framework for Scotland, in the form of an Act of the Scottish Parliament, should include "a right to a healthy environment".2 The recommendation also stated:

This overall right will include the right of everyone to benefit from healthy ecosystems which sustain human well-being as well [sic] rights of access to information, participation in decision-making and access to justice. The content of this right will be outlined within a schedule in the Act with reference to international standards, such as the Framework Principles on Human Rights and Environment developed by the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment, and the Aarhus Convention.

First Minster's Advisory Group on Human Rights Leadership. (2018, December 10). Recommendations for a new human rights framework to improve people's lives: Report to the First Minister. Retrieved from https://humanrightsleadership.scot/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/First-Ministers-Advisory-Group-on-Human-Rights-Leadership-Final-report-for-publication.pdf [accessed 19 September 2019]

On 12 June 2019, the Scottish Government announced the National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership.4 The taskforce will take forward the recommendations made by the First Minister's Advisory Group on Human Rights Leadership and focus on the development of new legislation. The Scottish Government's Programme for Government (PfG) 2019-20 stated:

The National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership will continue its work to establish a legislative framework for a Scottish Bill of Rights. This will be preceded, by the end of this Parliament, by legislation to incorporate the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Scottish Government. (2019, September 03). Protecting Scotland's Future: the Government's Programme for Scotland 2019-2020. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/protecting-scotlands-future-governments-programme-scotland-2019-20/ [accessed 04 October 2019]

Scope of the Briefing

This briefing considers the recommendation, of a right to a healthy environment, made by the First Minister's Advisory Group on Human Rights Leadership. The briefing focusses on international examples where environmental rights have been enshrined in law, Scotland's requirements to comply with the United Kingdom's (UK) international human rights obligations (and those in relation to the environment), access to justice in environmental matters and the impact of a potential exit from the European Union (EU). The briefing then explores how human rights can be integrated into environment-related policy in the context of issues such as the climate emergency, land reform, and sustainable development.

What are Environmental Rights?

Human rights and environmental policy are matters devolved to the Scottish Parliament.1 Most human rights law in Scotland is derived from the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). This was incorporated into UK law by the Human Rights Act 1998 (HRA) allowing the ECHR to be enforced through UK courts and the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR).

The ECHR encompasses "civil and political" human rights. The State has a duty to refrain from acting in a way that unjustifiably interferes with these human rights.2 The ECHR does not include a right to a healthy environment or explicitly recognise the environment in realising certain civil and political rights.3 However, the ECtHR has indicated it has had to develop its case-law where environmental issues undermine the exercise of rights in the ECHR (e.g. right to life, right to freedom of expression).35

The Scotland Act 1998 requires Scottish Ministers and the Scottish Parliament to act in accordance with the ECHR. The Scotland Act (and HRA) require all public authorities in reserved and devolved areas of competency to comply with the ECHR. Scotland is also required to respect international obligations found in the UN Core Human Rights Treaties. Notably, The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and International Covenant on Economic, Social & Cultural Rights (ICESCR) direct states to consider human rights and the environment when realising rights to health. The CRC asks governments to consider "dangers and risks of environmental pollution".6 The ICESCR asks states to adopt policies for "The improvement of all aspects of environmental and industrial hygiene".7

Human rights law in Scotland, its relationship with EU law and the implications of Brexit were covered previously in SPICe briefings:

Environmental Rights: A right to a healthy environment

The United Nations (UN) member states have not formally recognised the human right to a healthy environment in a global instrument.8 However, the Stockholm Declaration of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment 1972 is considered a broad recognition of the interplay between human activity, environmental issues and human rights:9

Man is both creature and moulder of his environment, which gives him physical sustenance and affords him the opportunity for intellectual, moral, social and spiritual growth. In the long and tortuous evolution of the human race on this planet a stage has been reached when, through the rapid acceleration of science and technology, man has acquired the power to transform his environment in countless ways and on an unprecedented scale. Both aspects of man's environment, the natural and the man-made, are essential to his well-being and to the enjoyment of basic human rights the right to life itself.

United Nations. (1972). Report of the United Nations Conference on the Environment, Stockholm, 5-16 June 1972. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/CONF.48/14/REV.1 [accessed 04 October 2019]

The Stockholm Declaration provided a non-binding set of principles and recommendations for environmental policy.10 After the Stockholm Declaration, there was a proliferation of countries including the right to a healthy environment in their constitutions.12 Over 100 countries now have a constitutional right to a healthy environment.12 The UK participated in the Stockholm Conference but does not currently recognise a right to a healthy environment in law10. However, despite the absence of a global instrument recognising a human right to a healthy environment, human rights norms relating to the environment have developed with the "greening" of human rights law - explored later in the briefing.15

Types of Environmental Rights

Environmental rights can be broadly categorised into 'procedural' and 'substantive' rights.16 Substantive rights depend on a clean environment for their enjoyment.16 States have an obligation to ensure legal frameworks that protect against environmental harm that interferes with the enjoyment of human rights.15 Procedural rights predominantly refer to access to information about the environment, participation in decision-making and access to justice in environmental matters.16 States' procedural obligations include assessing environmental impacts on human rights, making environmental information public, facilitating public participation in decisions and providing access to remedial law for environmental harm.15 States also have an obligation to ensure non-discrimination and their obligations to the protection of groups in vulnerable situations, including women, children and indigenous peoples.15

Framework Principles on Human Rights and the Environment

There have been clear calls for the UN to formally recognise a substantive right to a healthy environment, with both the current and previous UN Special Rapporteurs on Human Rights and the Environment recommending the right is incorporated in an international human rights instrument.12

The UN Human Rights Council appointed John Knox as the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment for 2015-18. The role of the Special Rapporteur is to assess human rights law in relation to the environment and promote best practice on human rights approaches to environmental policy.3

At the end of his mandate, John Knox presented the Framework Principles on Human Rights and the Environment (Framework Principles; see Annex 1). These principles detail the main human rights obligations relating to "the enjoyment of a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment". John Knox also urged the UN Human Rights Council to recognise the right to a healthy environment:

I hope the Human Rights Council agrees the right to a healthy environment is an idea whose time is here. The Council should consider supporting the recognition of this right in a global instrument.1

David Boyd, the current Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment, in a statement to the 73rd General Assembly of the United Nations in 2018 said:

After six years as mandate holder, Professor Knox came to the conclusion that there is a glaring gap in the global human rights system. He and I are in 100% agreement that it is time for the UN to recognize the fundamental human right to live in a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment. This right belongs to everyone, everywhere. Human life, health, well-being, and dignity depend on access to clean water, clean air, and a healthy environment.2

The Aarhus Convention and Procedural Environmental Rights

Principle 10 of the Rio Declaration 1992 is considered to be the international policy basis for procedural environmental rights:1

Environmental issues are best handled with the participation of all concerned citizens, at the relevant level. At the national level, each individual shall have appropriate access to information concerning the environment that is held by public authorities, including information on hazardous materials and activities in their communities, and the opportunity to participate in decision-making processes. States shall facilitate and encourage public awareness and participation by making information widely available. Effective access to judicial and administrative proceedings, including redress and remedy, shall be provided.

The United Nations Conference on Environment and Development. (1992). THE RIO DECLARATION ON ENVIRONMENT AND DEVELOPMENT. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/education/pdf/RIO_E.PDF [accessed 19 November 2019]

The United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-Making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters (i.e. the Aarhus Convention) is one of the only legally binding global instruments on environmental democracy.3 The Aarhus Convention puts Principle 10 of the Rio Declaration into practice and enshrines procedural environmental rights.3 It was ratified by the UK and EU in 2005.5 Scotland, via the UK, is obliged to respect and implement the Aarhus Convention.6 However, the compliance body for the Aarhus Convention (on which more later) have found Scotland (as part of the UK) to be non-compliant with requirements of the Aarhus Convention.

See Aarhus Compliance in Scotland for more information.

EU Exit: Impact on Environmental Rights

Debate over the implementation of procedural environmental rights or 'Aarhus rights' in Scotland precedes the 2016 EU Referendum. However, questions over how environmental standards will be maintained after EU Exit, and how Aarhus rights will be affected, have been central issues since the referendum.1

The loss of EU-level monitoring and enforcement mechanisms for environmental law as a result of EU exit could result in a "governance gap" with an associated impact on procedural environmental rights in Scotland (e.g. through loss of access to environmental information, or access to justice through existing complaints routes to the European Commission).1 The Scottish Government have recognised the potential for an environmental governance gap after Brexit and published the responses from their consultation on Environmental Principles and Governance after Brexit. The Scottish Government's PfG 2019-20 also stated:

The Scottish Government has decided to introduce a Continuity Bill to allow the Scottish Parliament to ‘keep pace’ with EU law in devolved areas if Brexit occurs. We are also clear that EU exit must not impede our ability to maintain high environmental standards. We will develop proposals to ensure that we maintain the role of environmental principles and effective and proportionate environmental governance and any legislative measures required will be taken forward in the Continuity Bill. In the event of ‘no deal’, we will put in place interim, non legislative measures while continuing to develop longer‑term solutions.

Scottish Government. (2019, September 03). Protecting Scotland's Future: the Government's Programme for Scotland 2019-2020. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/protecting-scotlands-future-governments-programme-scotland-2019-20/ [accessed 04 October 2019]

The issues of maintaining environment standards and procedural environmental rights are interdependent. Scottish Environment LINK, in their recent report on environmental governance approaches with exit from the EU stated:

To be clear, this review has shown that the existing governance structures are inadequate and will require reform and supplementing post-Brexit. This is not a matter for minor tinkering but for intelligent, integrative, systemic change to ensure that oversight is clear, simple, independent, robust, credible and effective. This is true not only of itself but also because there is a need to be seen to be taking the current and future rights of the citizen seriously: rights to information, to justice, to a clean environment, as consumers and to protection from harms, not least to the environment and to health.

Scottish Environment LINK. (2019, October). Environmental Governance: effective approaches for Scotland post-Brexit. Retrieved from http://www.scotlink.org/wp/files/documents/REPORT-Environmental-Governance-effective-approaches-for-Scotland-post-Brexit-OCT-2019.pdf [accessed 10 October 2019]

Comparative Approaches on the Right to a Healthy Environment

The Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment has argued that even without formal recognition of the right to a healthy environment, the term has been adopted to refer to the range of human rights that depend on a healthy environment. For example, in his report on the Framework Principles, the Special Rapporteur stated:

It raises awareness that human rights norms require protection of the environment and highlights that environmental protection is on the same level of importance as other human interests that are fundamental to human dignity, equality and freedom. It also helps to ensure that human rights norms relating to the environment continue to develop in a coherent and integrated manner.

Framework Principles on Human Rights and the Environment (2018). (2018, March 05). Retrieved from https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Environment/SREnvironment/Pages/FrameworkPrinciplesReport.aspx [accessed 04 October 2019]

This is further reflected by the first of the Framework Principles:

States should ensure a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment in order to respect, protect and fulfil human rights.

Framework Principles on Human Rights and the Environment (2018). (2018, March 05). Retrieved from https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Environment/SREnvironment/Pages/FrameworkPrinciplesReport.aspx [accessed 04 October 2019]

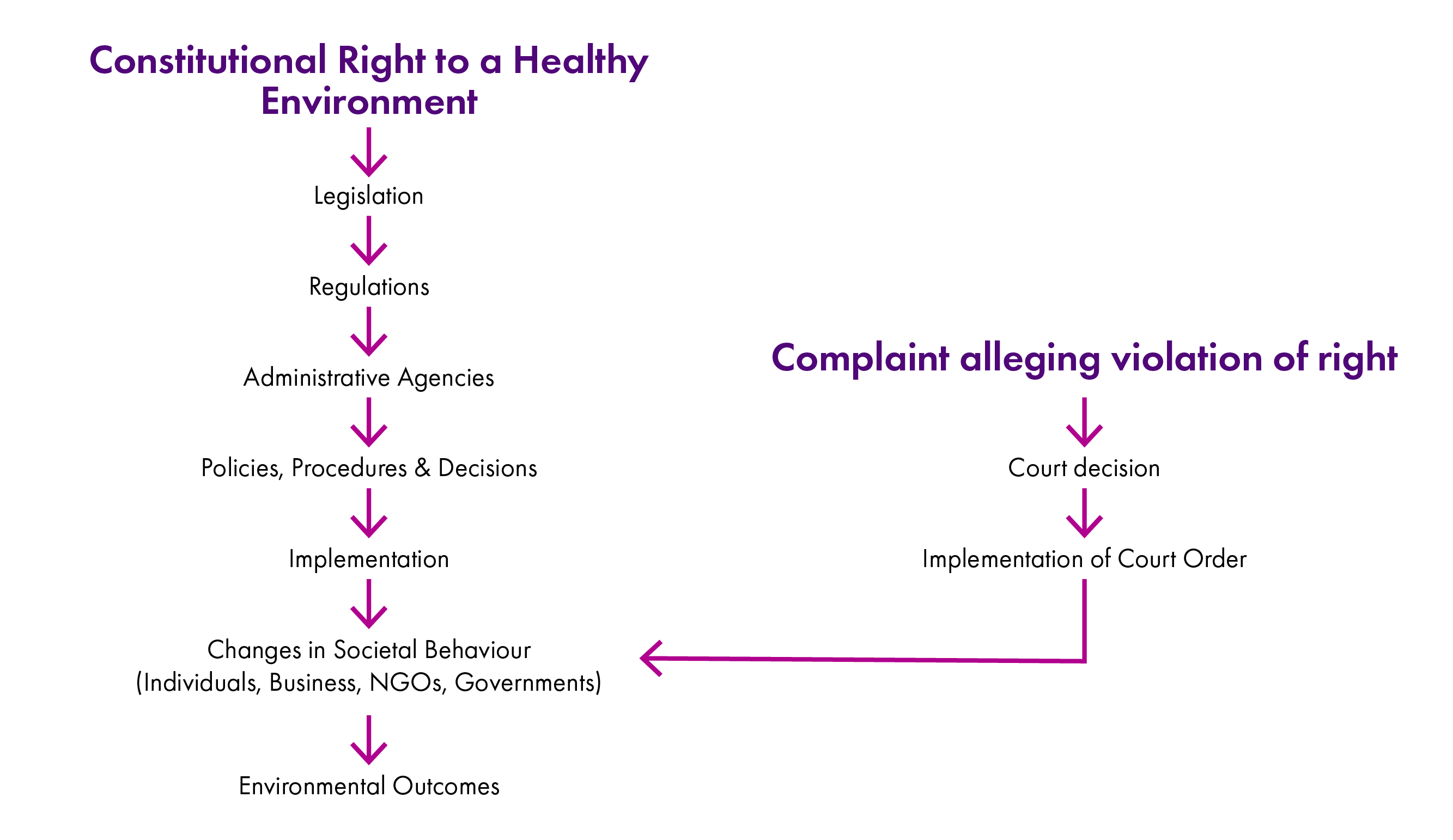

A substantive right to a healthy environment places the environment on the same level as other societal aims and constitutional human rights.3 The assumption underlying the guarantee of a right to a healthy environment is that it guides environmentally sensitive policy and decision-making by the government and legislature.3 Constitutional environmental rights are also intended to provide a route or redress on environmental matters that would not otherwise be provided for by the law.5

The Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment highlights some of the specific advantages afforded to countries where a constitutional right to a healthy environment has been implemented:

It has raised the profile and importance of environmental protection and provided a basis for the enactment of stronger environmental laws. When applied by the judiciary, it has helped to provide a safety net to protect against gaps in statutory laws and created opportunities for better access to justice.

Framework Principles on Human Rights and the Environment (2018). (2018, March 05). Retrieved from https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Environment/SREnvironment/Pages/FrameworkPrinciplesReport.aspx [accessed 04 October 2019]

However, it is difficult to determine the effectiveness of constitutional rights to a healthy environment in delivering good environmental outcomes.This is mostly due to the complexity in determining causal influence, the extent to which the right is built into environmental legislation and the enforceability of the right (see Image).7 The enforceability of the right is determined by a number of factors: specific provisions within the constitution, status of the judicial system, legal standing rules, availability of environment and human rights law expertise, legal costs associated with challenging human rights breaches in court and the strength of civil society.7

Case Studies: Influence of Constitutional Environmental Rights

Constitutional rights to a healthy environment, as mentioned previously, can shape environmental law and the extent to which the right is enforceable through the courts. This section describes examples of the implementation of a constitutional environmental right in several countries and the mechanisms affecting how the right is realised in public policy, legislation or environmental litigation.

For a summary table of the content of the right and availability of procedural rights, see Annex 2.

Portugal

Portugal recognised the "right to a healthy and ecologically balanced human living environment and the duty to defend it" in its constitution in 1976. The constitution concurrently established rights of standing to individuals and environmental NGOs in Portugal for acting in the public interest on environmental matters.1 The Framework Act on the Environment (1987) establishes the preservation of the environment and control of pollution as one of the essential tasks of the State. The Framework Act also elaborates on the procedural rights of citizens, including rights of participation in decision making and ensuring access to justice. The functioning of the right to a healthy environment was strengthened again in 2014 with Law No. 19 - The Environment Basic Law which aims to realise environmental rights through the promotion of sustainable development. If any development is to occur it should guarantee the well-being and progressive improvement to the quality of life of citizens following from the duty of the state to protect the environment.

In terms of the functioning of the right to a healthy environment through litigation, Portugal has comparatively liberal rules and laws on legal standing, litigation costs (NGOs are exempt from legal costs) and access to courts.1 There is limited evidence of the success of administrative and civil legal proceedings in environmental matters however. Despite the provision of many routes to access justice in environmental matters, some reviews suggest the uptake of these provisions is low.1

Norway

Norway added "a right to an environment that is conducive to health and to natural surroundings whose productivity and diversity are preserved" to their constitution in 1992. The constitution also states that the environmental right is a principle, not a self-executing right. Section 112, the part of the constitution enshrining the right to a healthy environment, states: "The State authorities shall issue further provisions for the implementation of these principles."4

Subsequent environmental law, such as the Environment Information Act, granted rights to environmental information and the right to participate in environmental decisions for Norwegian citizens. Despite procedural rights and legal standing for NGOs, there have been few environmental litigation cases directly invoking the constitutional right to a healthy environment in Norway.1 However, in Greenpeace Norway v. Government of Norway in 2017, the Oslo District Court ruled that the right to a healthy environment is an enforceable right protected by the constitution. Despite this, the District Court ruled that the Government's decision to extend licenses for oil exploration and drilling did not contravene the right to a healthy environment.6 The case began appeal proceedings at the Oslo Court of Appeal on 5 November 2019.

At the end of a visit to Norway in September 2019, the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment encouraged Norway to change the formulation of the right:

At this time in human history—faced with a global environmental crisis of unprecedented severity—recognizing, respecting, protecting and fulfilling the right to a healthy environment has never been more important. I therefore urge the Norwegian Government to modify its position and adopt the interpretation of Article 112, supported by the decision of the Oslo District Court, recognizing that it is a clear expression of the human right to live in a healthy environment.

OHCHR. (2019, September 23). Norway. End of Mission Statement. Retrieved from ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=25032&LangID=E#_ftn7 [accessed 17 November 2019]

South Africa

A substantive environmental right, "the right to an environment not harmful to their health and well-being", was added to the South African Constitution in 1996. This was complemented with a State duty to protect the environment for the benefit of future generations through pollution prevention, conservation and sustainable development.1 The constitutional right has been operationalised in several pieces of legislation. The National Environment Management Act 1998 incorporates the right to an environment not harmful to people's health, enshrines rights to environmental information, allows legal standing for citizens and NGOs in environmental matters and lays out several other environmental governance processes. Legislation on biodiversity and air quality also refers to the constitutional environmental right.

The constitutional environmental right has not only influenced environmental law-making, but also the enforcement of environmental law. The South African judiciary have been active in enforcing the right and have ruled on cases across a range of environmental matters (e.g. commercial developments, air pollution, waste management). The National Environment Management Act, which guarantees citizens' procedural rights and legal standing in environmental cases has been upheld on the basis that environmental protection depends on an active civil society.1 As such, South Africa benefits from a strong civil society presence in environmental governance. Several remedies are offered through the courts in environmental matters; rulings that a law is valid or invalid, administrative action, injunctions, or damages.1

Argentina

Argentina amended their Constitution in 1994 to include "the right to a healthy, balanced environment, which is fit for human development so that productive activities satisfy current needs without compromising those of future generations."11 The constitutional right prompted a new programme of environmental law incorporating it. The Law on National Environmental Policy (2002) sought to incorporate the new right by setting out a comprehensive body of environmental law and principles. It sets out environmental management standards and the allocation of several environment funds (e.g. environmental restoration, insurance and compensation for environmental damage). It also grants procedural rights such as participation in environmental decisions and the promotion of environmental education. The availability of legal procedures and legal standing rules have increased the ability of citizens and NGOs to seek access to justice in environmental matters.1

Courts are active in upholding the constitutional right to a healthy environment and regularly engage in judicial activism.1 The right makes reference to human development, satisfying current needs and acknowledging the rights of future generations. This has resulted in litigation where courts have legally required investments in infrastructure to help realise substantive environmental rights. For example, the right to water and sanitation is not explicit in the Argentine Constitution. In Mendoza and others v. National Government (2008), a group of residents in the Matanza-Riachuelo river basin in Buenos Aires filed a case against the Government for not protecting the environment from the discharge of industrial waste into the river. The residents also claimed that 44 businesses in the area were responsible for negative health effects of the industrial pollution. Argentina's Supreme Court upheld the constitutional right to a healthy environment and ordered a restoration operation. The Autoridad de Cuenca Matanza Riachuelo (ACUMAR) oversees the project including new waste-water treatment systems.

"Greening" Human Rights in European Court of Human Rights

Arguments against constitutional rights to a healthy environment include their relative ineffectiveness or redundancy given that existing human rights law can be "greened". The "greening" of human rights law can be applied to cases where environmental harm has resulted in a human rights violation or undermines the exercise of a certain human right (e.g. right to life).1

European Court of Human Rights

The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) has delivered a series of important and widely cited decisions on environmental matters even though the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) does not recognise a right to a healthy environment.1

Human rights violations have been found arising from a wide array of environmental issues (e.g. industrial pollution, natural disasters, waste management, access to courts). The basis for claims in environment-related cases have ranged across rights enshrined in the ECHR:

Right to life (Article 2)

Prohibition of inhuman or degrading treatment (Article 3)

Right to liberty and security (Article 5)

Right to a fair trial (Article 6)

Right to respect for private and family life, home and correspondence (Article 8)

Freedom of expression (Article 10)

Right to an effective remedy (Article 13)

Protection of property (Article 1 of Protocol 1)

The most common basis for environmental claims is Article 8 of the ECHR. The ECtHR has adopted a low threshold for environmental harm in these cases. For example, environmental harm does not need to be endangering a person's health to be interfering with their right to respect for private and family life. The threshold is also reviewed on a contextual basis, in other words, what constitutes suitable environmental conditions varies depending on the case.1 Contrary to constitutional rights to a healthy environment, the ECtHR does not qualify interference based on the negative or positive health outcome for the claimants or environment. Rights enshrined in the ECHR do not protect claimants against all environmental harm since the ECtHR limit the enjoyment of ECHR rights where societal and individual interests need to be balanced (n.b. this can be said of all human rights).1

Balancing human rights and environmental rights is discussed in the commentary of the Framework Principles. The Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment stated in the commentary of Principle 11:

Ideally, environmental standards would be set and implemented at levels that would prevent all environmental harm from human sources and ensure a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment. However, limited resources may prevent the immediate realization of the rights to health, food, water and other economic, social and cultural rights. The obligation of States to achieve progressively the full realization of these rights by all appropriate means requires States to take deliberate, concrete and targeted measures towards that goal, but States have some discretion in deciding which means are appropriate in light of available resources. Similarly, human rights bodies applying civil and political rights, such as the rights to life and to private and family life, have held that States have some discretion to determine appropriate levels of environmental protection, taking into account the need to balance the goal of preventing all environmental harm with other social goals.

This discretion is not unlimited. One constraint is that decisions as to the establishment and implementation of appropriate levels of environmental protection must always comply with obligations of non-discrimination (framework principle 3). Another constraint is the strong presumption against retrogressive measures in relation to the progressive realization of economic, social and cultural rights.

Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment. (2018, January). A/HRC/37/59: Report of the Special Rapporteur on the issue of human rights obligations relating to the enjoyment of a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment. Retrieved from https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G18/017/42/PDF/G1801742.pdf?OpenElement [accessed 12 November 2019]

Summaries of the rulings and judgements from environment-related cases heard at the ECtHR can be found in the Environment and the European Convention on Human Rights Factsheet.

Aarhus Compliance in Scotland

The Aarhus Convention guarantees procedural environmental rights for the public. The underlying assumption is that governments obliged to act with transparency and civic participation in environmental matters will deliver better environmental governance.1

Three Pillars of the Aarhus Convention

The Aarhus Convention links environmental protection and governmental accountability by enshrining procedural environmental rights for members of the public (and organisations or legal persons).2

The Aarhus Convention is organised around three pillars:

Access to information on the environment held by public authorities (e.g. information on the state of the environment) and the active dissemination of information by public authorities.

Participation in environmental decision making (e.g. development decisions, preparation of policies and legislation relating to the environment).

Access to justice regarding environmental matters (e.g. to challenge a response to an information request, the legality and merits of a decision, actions contravening national environmental law).

The third pillar of the Aarhus Convention ("access to justice") grants rights to members of the public (including NGOs) to challenge decisions relating to the environment made by public authorities. Article 9(4) of the Aarhus Convention requires that procedures facilitating access to justice in environmental matters:

provide adequate and effective remedies, including injunctive relief as appropriate and be fair, equitable, timely and not prohibitively expensive.

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. (1998, June 25). Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-Making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters. Retrieved from https://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/env/pp/documents/cep43e.pdf [accessed 22 November 2019]

In addition, Article 9(5) requires Parties to:

ensure that information is provided to the public on access to administrative and judicial review procedures and shall consider the establishment of appropriate assistance mechanisms to remove or reduce financial and other barriers to access to justice.

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. (1998, June 25). Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-Making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters. Retrieved from https://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/env/pp/documents/cep43e.pdf [accessed 22 November 2019]

Aarhus Convention Compliance Committee

The Aarhus Convention has a compliance mechanism to hold governments and decisions makers accountable - the Aarhus Convention Compliance Committee (ACCC). The ACCC is a non-judicial body that seeks to help Parties meet their obligations under the Aarhus Convention.1 Members of the public are able to make complaints directly to the ACCC. The UK has been found to be non-compliant with the Aarhus Convention by the ACCC in 2015, 2017 and 2019. The Meeting of Parties (to the Aarhus Convention) formally acknowledged this in 2014 and 2017.

The ACCC provide recommendations to the UK on the compliance requirements for each of the devolved legislatures. On providing affordable access to justice, the costs of environmental litigation within the Scottish legal system were seen as prohibitively high. Access to justice in environmental matters in Scotland predominantly takes place by judicial review (some environmental matters may be dealt with via environmental appeals to the Scottish Government, or in environment-related statutory appeals and summary applications).2 Judicial review proceedings examine the lawfulness of a decision and are only available when no other remedy is available or all other options have been exhausted.3 The losing party pays their own and the winning party's legal costs.2 The prospect of legal aid funding in environmental cases is also very limited.5 This poses significant financial risk to the petitioner in environmental litigation.6

When the petitioner is acting in the public interest, protective expense orders (PEO) may be granted. PEOs are orders that pre-emptively limit parties' liability for costs.7 In 2018, new PEO rules for environmental judicial reviews and statutory appeals in the Court of Session were introduced.8 These new rules make changes to how parties to the proceedings can limit expenses under a PEO (see Rules of the Court of Session 58A.7). The applicant's liability for costs are limited to £5000 (or any other sum that can be justified).9 Moreover, when a PEO is made, it must also make a provision to limit the opponents' liability. This is set to £30,000 (or any other such sum that can be justified).9 Previously, applicants' liability for costs was capped to £5000 or lower, and opponents' liability to £30,000 or higher (if the applicant could demonstrate this was reasonable).11 The new PEO rules could have the effect of increasing the applicants' liability for costs if unsuccessful, or, if successful, decreasing the PEO applicants' ability to recover costs.12

Furthermore, the new rules remove the need for an additional hearing to approve a PEO (which created additional legal costs) and define the term "prohibitively expensive" (see Rules of the Court of Session 58A.1).12 The Court must grant a PEO if it is satisfied the proceedings are "prohibitively expensive". In addition, the PEO now carries over if the case is appealed.12 While there will be no need to reapply, the cap granted by PEO also remains in place (i.e. it does not change to reflect additional costs incurred by further legal proceedings).12

The ACCC concluded in February 2019 that even with these changes, Scotland remained non-compliant. The areas requiring further attention were the types of claim covered, levels of the cost caps and cost protection on appeal.16 The UK submitted another progress review in September 2019. The ACCC have not yet responded (see submitted documents here).

Scottish Parliament Petition: Access to Justice in Environmental Matters

Aarhus compliance in Scotland has been the subject of a long-running petition to the Scottish Parliament. The petition (Access to Justice in environmental matters) by Friends of the Earth Scotland, was lodged on the 12 November 2010. The petition's summary states it is:

Calling on the Scottish Parliament to urge the Scottish Government to clearly demonstrate how access to the Scottish courts is compliant with the Aarhus convention on ‘Access to Justice in Environmental Matters’ especially in relation to costs, title and interest; publish the documents and evidence of such compliance; and state what action it will take in light of the recent ruling of the Aarhus Compliance Committee against the UK Government.

PE01372: Access to justice in environmental matters. (2010, November 12). Retrieved from http://external.parliament.scot/GettingInvolved/Petitions/petitionPDF/PE01372.pdf [accessed 17 November 2019]

The petition is currently being considered by the Equalities and Human Rights Committee (EHRiC). As part of the committee's consideration of the petition, the committee wrote to the Scottish and UK Governments for further information on the status of Aarhus compliance. The Scottish Government does not accept it is non-compliant with the Aarhus Convention. The Cabinet Secretary for Justice, Humza Yousaf MSP wrote to the EHRiC on 26 June 2019:

The Scottish Government is confident that it is compliant with the requirement of the Aarhus Convention in respect of maintaining access to justice in environmental cases. It is supported in this view that the infraction case initiated by the European Commission in relation to the UK’s transposition of Articles 3(&) and 4(4) of the EU’s Public participation Directive (PPD) has now been closed. In saying that I acknowledge that although the UN’s Aarhus Convention Compliance Committee (the Compliance Committee) has recognised ‘significant progress to date’ it is still of the opinion that there are further issues to be addressed. We will continue to engage with the committee to reassure them of Scotland’s continued compliance.

Cabinet Secretary for Justice, Humza Yousaf MSP: Scottish Government. (2019, June 26). Petition PE01372: Access to Justice in Environmental Matters. Retrieved from https://parliament.scot/S5_Equal_Opps/ScotGov_responce_petition1372.pdf [accessed 09 October 2019]

Therese Coffey, the then UK Government Minster of State (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs) stated in a letter to the EHRiC on 26 June 2019:

The UK Government is committed to the effective implementation of the Aarhus Convention. The implementation of the Convention in Scotland is a devolved matter and questions concerning compliance with the Aarhus Convention in relation to Scotland should most appropriately be raised with the Scottish Government.

Equalities and Human Rights Committee Agenda: 27th Meeting, 2019 (Session 5). (2019, November). Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/S5_Equal_Opps/Agenda_and_Papers_20191114.pdf [accessed 13 November 2019]

On the incongruence between responses from the ACCC, Scottish Government and UK Government, Mary Church (of Friends of the Earth Scotland) stated in a letter to the EHRiC on 25 September 2019:

We would start by noting that 9 years after tabling our petition the Scottish Government remains in non-compliance with the Aarhus Convention, as is evident from the most recent (February 2019) assessment of the Convention’s Compliance Committee (ACCC).

The Committee will be aware that the most recent assessment is the latest of 7 consecutive decisions of the ACCC and the Aarhus Convention’s Meeting of the Parties to have found that the Scottish civil justice system does not comply with Article 9 of the Convention, with the first such finding being made by the ACCC in 2014. Our petition therefore concerns a long-running, systemic problem.

Sadly the latest finding is unsurprising, since the Scottish Government has to date failed to undertake a comprehensive review of the Scottish legal system in relation to Article 9 provisions and has instead taken a reluctant, piecemeal approach to compliance.

Equalities and Human Rights Committee Agenda: 27th Meeting, 2019 (Session 5). (2019, November). Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/S5_Equal_Opps/Agenda_and_Papers_20191114.pdf [accessed 13 November 2019]

At the EHRiC meeting on 14 November 2019, the committee agreed to keep the petition open.

Impact of EU Exit on Procedural Environmental Rights

As the ECHR, UN core human rights treaties and the Aarhus Convention are independent of EU membership, they will continue to apply to the UK in the event of EU exit.1 However, the EU is also a party to the Aarhus Convention and applies the Aarhus Convention to EU institutions and bodies via the Aarhus Regulation.2 The EU has also implemented certain Aarhus rights into EU law for Member States (e.g. Public Participation Directive and Directive on Public Access to Information). These Directives have bolstered the role of the European Commission and the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) in protecting environmental rights in the EU.3

Leaving the EU is expected to remove the UK from the jurisdiction of the European Commission and the CJEU, and the loss of EU oversight structures could impact the enforceability of environmental rights. In Commission v United Kingdom (C-530/11), the CJEU ruled in 2014 that access to justice was prohibitively expensive in the UK. This decision was binding and required the UK government to bear the costs. Conversely, the ACCC is a non-judicial and recommendatory body. The Meeting of Parties consider the ACCC's recommendations and decide on non-judicial, non-confrontational and consultative measures to bring about full compliance with the convention.4

It should be noted that the EU was also found to be non-compliant with the Aarhus Convention by the ACCC due to insufficient administrative and judicial routes of redress at EU level.5

Access to Justice Approaches

The Scottish Government published an analysis of its consultation on Developments in environmental justice in Scotland in September 2017. This consultation sought views on establishing an environmental court for Scotland. More recently, in October 2019, the Scottish Government published the responses to their consultation on Environmental principles and governance after Brexit in view of preparing for environmental governance post EU exit.

This section provides information on, and examples of, approaches that have been developed or used internationally to improve environmental governance and operationalise procedural environmental rights, in particular access to justice. These include public interest litigation (PIL), environmental rights centres, environmental courts and Rights of Nature.

Barriers to Public Interest Litigation in Scotland

Negative environmental impacts are often diffuse in nature and tend to affect groups rather than specific individuals.1 Consequently, the extent to which a judicial system allows for PIL is highly relevant to the question of access to justice in environmental law and disputes - and thus the availability of procedural environmental rights. Relatively recent environmental cases in Scotland have been said to demonstrate significant barriers and deterrents to taking legal action in order to protect the public interest of safeguarding natural resources and the environment.1 Difficulties can involve demonstrating legal standing (i.e. showing that the party has a sufficient connection to and harm from the action being challenged in litigation) and the risk of incurring significant financial costs.

Under the Aarhus Convention, it is up to parties to the Convention, within their own national framework of legislation, to determine what constitutes a "sufficient interest". The Convention also states this should be done "consistently with the objective of giving the public concerned wide access to justice within the scope of this Convention". In Scottish courts, public interest petitioners had typically struggled to demonstrate the previous test for standing of "title and interest" in order to challenge a decision.3 In other words, to demonstrate they have private or property interests that could be impacted by the decision in consideration by the courts.3 This resulted in petitioners being challenged on standing in several environmental judicial review cases (e.g. Marco McGinty v The Scottish Ministers on the Hunterston Power Station proposals).

In 2011, Friends of the Earth Scotland intervened in AXA General Insurance Limited and others v The Lord Advocate (Scotland) at the Supreme Court.3 This case established the interpretation of standing in Scots law as "sufficient interest" allowing cases to be raised in the public interest. The ("sufficient interest") test requires the petitioner is directly affected by the matter (i.e. has a reasonable concern) or is able to demonstrate genuine concern on behalf of those likely to be affected by the decision.1

Additionally, PIL on environmental matters can incur significant costs to a petitioner particularly if they lose the case. The John Muir Trust lost an appeal of a judicial review case regarding a wind-farm development at Stronelairg in the Highlands.7 They were ordered to pay costs of £350,000 and £189,000 to SSE and the Scottish Government respectively.8 The costs were negotiated down to £50,000 and £75,000. The Scottish Government stated they held "responsibility to consider the interests of taxpayers, in relation to costs incurred in legal actions".9

Overcoming Barriers to Public Interest Litigation in Scotland1

A report published by the Human Rights Consortium Scotland and Scottish NGOs identified five key barriers to PIL in Scotland:

Difficulty Accessing Case Information

Limited case information provided by courts and within a time-frame that permits reasonable success for intervening in a case.

Court decisions are not readily available (except in cases heard at the Court of Session, Supreme Court and ECHR).

Parties intervening in a case are not able to receive court papers.

Issues of Legal Standing

Applicants need to demonstrate "sufficient interest" in judicial review cases.

Only victims of alleged human rights violations can bring a challenge before UK courts and the ECHR.

Time Limits to Make Claims

Time limits to make a claim and intervene vary depending on area of law.

For judicial review cases, the organisation must bring a challenge to the court within 3 months.

Inhibitive Costs

Costs include (but not limited to) court fees, preparing court documents, opposing parties' expenses (dependent on if the case is lost and whether costs are capped), and fees for legal advice and representation.

Limited Culture of PIL

Opportunities to take part in media campaigns and public consultations on policy and legislation are familiar to NGOs in Scotland, and widely used.

Uncertainty over how NGOs can cooperate and collaborate in using the law to progress social change as a party to a PIL case or outwith.

Environmental Rights Centres

Environmental rights centres (ERCs) are public, independent or charitable bodies aiming to support and advise citizens about access to justice for environmental matters.1 ERCs may also pursue PIL for environmental matters.1

Environmental Rights Centre for Scotland

Scottish Environment LINK published a feasibility study of an Environmental Rights Centre for Scotland. They recommended that an ERC for Scotland in March 2018:1

Provide affordable legal advice and representation to the public and civil society.

Carry out public legal education.

Carry out legal research.

Advocate for law and policy reform.

pursue strategic litigation.

Scotland's NGO community have expressed support for an ERC and are in the process of setting up an ERC via Scottish Environment LINK.4

Environmental Courts and Tribunals

Environmental courts have been established in various countries as a means of enforcing environmental law and ensuring access to justice in environmental matters. More than 1200 courts exist in 44 countries.1 Dedicated and specialist environmental courts have been suggested as more suitable than judicial review procedures to resolve environmental disputes in Scotland.2

An Environmental Court for Scotland?

Scottish Environment LINK recently published their report Environmental Governance: Approaches for Scotland post-Brexit. They argued that an environmental court should be included in a coherent governance system post-Brexit.

On establishing an environmental court, the Scottish Government stated in September 2017 as part of the consultation analysis on Developments in environmental justice in Scotland:

The Scottish Government has considered the issue carefully and is fully mindful of the views of the respondents to the consultation. The variety of views on what sort of cases an environmental court or tribunal should hear combined with the uncertainty of the environmental justice landscape caused by Brexit lead Ministers to the view that it is not appropriate to set up an [sic] specialised environmental court or tribunal at present. The Government will, however, remain committed to environmental justice and will keep the issue of whether there should be an environmental court or tribunal or even a review of environmental justice under review.

The Scottish Government. (2017, September 29). Developments in environmental justice in Scotland: analysis and response. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/developments-environmental-justice-scotland-analysis-response/pages/4/ [accessed 14 October 2019]

Models of Environmental Courts

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) identified seven judicial problems relating to environmental disputes that environmental courts can be designed to address:1

Limited knowledge of environmental law and technical or scientific expertise required in assessing environmental matters.

Large numbers of cases being heard by general courts and slow court proceedings.

High legal and court costs for litigants.

General courts unable to prioritise environmental cases.

Insufficient enforcement of decisions and remedies for the environment.

Traditional win-lose approaches adopted rather than problem-solving approaches focussed on improving the environment and sustainability.

Lack of flexibility in court rules and procedures (e.g. legal standing, difficulty encouraging public participation, access to information and transparency or accountability).

Environmental courts of different models have been implemented in countries of varying development and legal systems. These models can make use of best practice features of a judicial model for handling environmental disputes as suggested by UNEP, including:1

Judicial independence

Flexible court rules and procedures

Use of alternative dispute resolution and public participation

Comprehensive jurisdiction (i.e. geographic, subject-matter, level of review, appeal)

Effective remedies for environment and enforcement powers

Providing citizens, organisations and communities (of place and interest) with access to courts by means of open standing

Recruiting legal, technical and scientific expertise required to assess the merits of an environmental case.

| Model | Operations |

|---|---|

| Operationally Independent | Free-standing, fully or substantially independent courts. Tend to be more expensive and complex but have wider jurisdiction and incorporate higher number of best practices.Examples

|

| Decisionally Independent | Environmental courts included in the general court system (i.e. within its supervision, budget and management), but have independence in terms of procedures, rules and decisional freedom.Examples

|

| Multi-disciplinary Decision Making | Can be incorporated in both the operationally independent and decisionally independent models of environmental courts. The court adopts an interdisciplinary approach to adjudication, combining the analysis and decision-making of both law-trained and technical-trained judges as co-decision makers.Examples

|

| General Court Judges Assigned Environmental Cases | A general court designates or assign established courts or judges as “green benches” or “green judges” and declares the establishment of an environmental court.Examples

|

| General Court Judges Trained in Environmental Law | Environmental training for select judges but an environmental court is not created.Examples

|

Environmental courts in Chile, Kenya and Sweden were discussed as part of SPICe briefing: Mainstreaming nature - international approaches to biodiversity conservation.

Rights of Nature

An emerging approach to ensuring or enhancing access to justice in environmental matters is the granting of legal rights for, or legal personhood to, nature, and thus, recognising nature has a right to be protected.1 This approach has only been taken in several places around the world. A frequently cited issue in environmental litigation, domestically and globally, is determining who has legal standing and experienced adequate harm to protect environmental interests and take claims of environmental damage to court.23 Allowing nature to be a rights holder in this scenario provides an opportunity for nature to be represented without the need for its representation to have legal standing.4

Ecuador

Various approaches have been taken in adopting legal personhood or constitutional legal rights for nature. In 2008, Ecuador embedded the rights of nature into its constitution. The amendment to the constitution recognises nature as having "the right to integral respect for its existence and for the maintenance and regeneration of its life cycles, structure, functions and evolutionary processes".5 The legal authority to defend nature is granted to the people of Ecuador with ecosystems themselves being named as defendants.6 The case Wheeler et al. v. Director de la Procuraduria General del Estado en Loja was the first court case in Ecuador to rule in favour of the rights of nature.7 Residents of the Vilcamba River riverfront took the provincial government to court on the basis that the construction of a road would deposit vast amounts of waste material into the river.7

Tamaqua Borough, PA, United States

In the United States, some local municipalities have recognised the rights of nature.9 The first local Rights of Nature ordinance was granted in Pennsylvania in 2006.9 Concerns over water quality were raised by citizens in response to the dumping of coal mine reclamation and sewage waste in rivers by corporations.6 The Tamaqua Borough council granted a Rights of Nature ordinance recognising the rights of borough citizens to defend the community's ecosystems.9 The waste disposal was then seen as a violation of the Rights of Nature and banned. Since then over 30 local municipalities in seven US states have granted Rights of Nature ordinances.13

New Zealand

New Zealand is notable in its approach of granting legal personhood to nature. Te Urewera was a national park in New Zealand from 1954 until 2014.14 The land was the basis of a long-running dispute between the indigenous Maori and the New Zealand Government over who had the rights to ownership and governance of the land.15 A resolution was reached with the Te Urewera Act 2014 which removed the national park status and granted legal personhood to the 2000km2 land area of Te Urewera.14 The legislation was considered a shift from a utilitarian view of the land (e.g. land with tourism or agricultural value) to one that integrates Maori characterisation of the land into the legal framework.14 The Te Urewera Act was also considered significant for recognising the right to participation in decisions about the land, enabling an ongoing partnership between people and authorities, and ensuring the right to culture is protected.18

Rights of nature has recently gained attention as a means of environmental governance, acknowledging or helping to realise cultural rights of indigenous communities and protecting the environment.19 In 2017, four rivers were granted personhood:20

Whanganui River, New Zealand

Ganges and Yamuna Rivers, India (now overturned by Supreme Court)

Attrato River, Colombia

Rivers as legal persons was discussed as part of SPICe briefing: Mainstreaming nature - international approaches to biodiversity conservation.

Some concerns regarding the approach of granting rights of nature have been raised in relation to financial costs of ensuing judicial processes and the challenges of enforcing those rights. In Ecuador, when rights of nature have been recognised in legal decisions, the relevant local bodies responsible for enacting reparations have lacked enforcement capacity.21 This approach to environmental rights is therefore only likely to be effective in protecting the environment if given appropriate force and effect.21

| Ecuador | US (Pennsylvania) | New Zealand | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scope | How is Nature defined (framed)? | All of Nature; Pachamama (Mother Earth) | Ecosystems in municipality (natural community) | Te Urewera Forest (living spiritual beings) |

| Which rights? | To exist and maintain ecosystem integrity; restored when damaged | To exist and "flourish" | Legal personhood status | |

| Strength | Type of law/legal standing | Constitution (maximum legal standing) | Municipal ordinances (subordinate to state and federal law); home rule charters (legal standing unclear) | Act of Parliament (parliamentary supremacy) |

| Hierarchy of rights | Rights of Nature declared transversal | Places Rights of Nature over corporate rights | Not explicitly addressed | |

| Who represents Nature? | Everyone | City/municipal citizens | Appointed guardians | |

| Mandated responsibility for protecting Nature? | No | No | Yes |

Human Rights Based Approaches to Environmental Policy

Human rights can play an important role in mediating the relationship between humans and the environment.1 Where a right to a healthy environment exists, the formulation of such a right can be used to balance the integrity of ecosystems with our rights to benefit from them (i.e. the balance of resources between environmental and socio-economic needs).1 Human rights can be used to establish rights and duties.1 Additionally, they offer another potential legal mechanism to tackle issues such as environmental degradation1.

The implementation of environment-related laws and policies may affect the enjoyment of human rights, and conversely the enjoyment of some human rights (e.g. the right to property) may have negative impacts on environmental protection. The adoption of a rights-based approach can therefore help to identify instances where environmental protection and human rights go hand in hand, and solutions to conflicts between the two.5

Human Rights Based Approach

The Scottish Human Rights Commission have led the integration of human rights based approaches (HRBA) in Scotland based on the approach laid out by the UN. The PANEL principles are used to implement a HRBA and ensure that people's rights are put at the centre of policies and decisions.5

Participation

People should be involved in decisions that affect their rights.

Accountability

There should be monitoring of how people’s rights are being affected, as well as remedies when things go wrong.

Non-discrimination

All forms of discrimination must be prohibited, prevented and eliminated. People who face the biggest barriers to realising their rights should be prioritised.

Empowerment

Everyone should understand their rights, and be fully supported to take part in developing policy and practices which affect their lives.

Legality

Approaches should be grounded in the legal rights that are set out in domestic and international laws.

The Framework Principles can be used to reinforce a HRBA to environmental policy, as they form the most authoritative compilation of principles on human rights and environment to date. The principles are in part based on treaties (e.g. Aarhus Convention) and binding decisions from human rights tribunals.7 Others are based on non-binding statements of human rights bodies. They can be used to inform and complement States' existing human rights obligations in relation to the environment.7

Current environmental challenges, in particular the climate emergency and biodiversity loss, pose immense threats to the enjoyment of human rights in Scotland and worldwide.9 The impacts of climate change, as well as the actions taken to mitigate and adapt to climate change, also have pervasive impacts on the rights of children and the rights of future generations.9 The following section describes human rights obligations relating to climate change and examples of how the rights of future generations can be integrated into policy. Land reform, with the implementation of community rights to buy, is also highlighted as an example of how human rights can be integrated into environmental policy.

Impact of Climate Change and Biodiversity Loss on Human Rights

Human activities (e.g. burning of fossil fuels) are causing climate change and biodiversity loss. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reported that the world is already experiencing increased frequency, intensity and duration of extreme weather events, rising sea levels, increased air pollution, ecosystems degradation and destruction, biodiversity loss and the spread of disease.1

Scotland is expected to experience significant effects of climate change including rising sea levels, hotter, drier summers and milder, wetter winters.2 Extreme weather events such as more frequent summer heat waves and intense precipitation events are also expected.2 This has and will have direct, indirect and cumulative effects on our natural environment, infrastructure, food security, health and cultural heritage.4

The 2015 Paris Agreement is an international treaty which aims to keep global warming below 2°C, with special efforts to limit the increase to 1.5°C by requiring states to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.5 The UK is a party to the Paris Agreement. Current contributions set by parties to the treaty are not expected to limit global warming increase to below 3°C.1 The preamble of the Paris Agreement explicitly linked climate change with human rights obligations:

Acknowledging that climate change is a common concern of humankind, Parties should, when taking action to address climate change, respect, promote and consider their respective obligations on human rights, the right to health, the rights of indigenous peoples, local communities, migrants, children, persons with disabilities and people in vulnerable situations and the right to development, as well as gender equality, empowerment of women and intergenerational equity

United Nations. (2015). Paris Agreement. Retrieved from https://unfccc.int/files/meetings/paris_nov_2015/application/pdf/paris_agreement_english_.pdf [accessed 16 October 2019]

Climate change threatens the full enjoyment of human rights. The Male’ Declaration on the Human Dimension of Global Climate Change (from a meeting of small island states hosted by the Maldives in 2007) called on the UN Human Rights Council to conduct research on human rights obligations and the impacts of climate change. It was the first international declaration to explicitly state the effects climate change will bear on human rights:

Climate change has clear and immediate implications for the full enjoyment of human rights including inter alia the right to life, the right to take part in cultural life, the right to use and enjoy property, the right to an adequate standard of living, the right to food, and the right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health;

Male’ Declaration on the Human Dimension of Global Climate Change. (2007). Retrieved from http://www.ciel.org/Publications/Male_Declaration_Nov07.pdf [accessed 17 October 2019]

The Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment released the Safe Climate report in October 2019 concluding that a safe climate is a crucial element of the right to a healthy environment. The report highlights the effects of climate change on the enjoyment of many human rights and gave special consideration to the disproportionate effects of climate change on vulnerable populations.

| Impact on Right from Climate Change | |

|---|---|

| Right to life |

|

| Right to health |

|

| Right to food |

|

| Right to breathe clean air |

|

| Rights to water and sanitation |

|

| Rights of the child |

|

Impact of Biodiversity Loss on Human Rights

Biodiversity loss is also being driven by climate change and human activity, with pervasive effects on human rights. The Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment clarified the dependence of some human rights on the sustainable use of biodiversity, namely, the right to life, health and an adequate standard of living.11 Biodiversity conservation has socio-economic benefits in terms of providing food, medicine, tourism and well-being.12 Healthy ecosystems are key to sustainable development and can be used to realise human rights such as access to natural resources and rights to culture.12

| Impact on Right from Climate Change | |

|---|---|

| Rights to life and health |

|

| Right to an adequate standard of living |

|

| Non-discrimination and rights of vulnerable groups |

|

The interplay between biodiversity and human rights obligations are also acknowledged in the Scottish National Performance Framework. Under the National Outcome for Environment associated with the framework, the "Vision" states:

We see our natural landscape and wilderness as essential to our identity and way of life. We take a bold approach to enhancing and protecting our natural assets and heritage. We ensure all communities can engage with and benefit from nature and green space. We live in clean and unpolluted environments and aspire to being the greenest country in the world.

We are committed to environmental justice and preserving planetary resources for future generations.

The relationship between biodiversity loss and the climate crisis was recognised in the Scottish Government's PfG 2019-20:

Biodiversity loss and the climate crisis are intimately bound together: nature plays a key role in defining and regulating our climate and climate is key in shaping the state of nature.

Scottish Government. (2019, September 03). Protecting Scotland's Future: the Government's Programme for Scotland 2019-2020. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/protecting-scotlands-future-governments-programme-scotland-2019-20/ [accessed 04 October 2019]

Human Rights Obligations Relating to Climate Change

The Safe Climate report by the Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment clarifies States' human rights obligations and private actors' responsibilities relating to climate change:

States' Procedural Obligations

Provide the public with accessible information on the global climate crisis and incorporate climate change into the educational curriculum.

Ensure inclusive public participation in all climate-related actions with a particular focus on empowering marginalised and the most affected populations.

Enable affordable and timely access to justice to hold public authorities and businesses accountable for complying with their climate change obligations.

Assess the potential climate change and human rights impacts of all plans, policies and proposals.

Integrate gender equality into climate action.

Respect the rights of indigenous peoples in climate action with particular attention to ensuring free and informed consent from indigenous communities.

Ensure protection for environmental and human rights defenders working on all climate-related issues (e.g. from violence, harassment etc).

States' Substantive Obligations

States must not violate the right to a safe climate through their own actions or the actions of corporate actors or businesses.

States must establish and enforce law and policy to fulfil the right to a safe climate.

States must avoid discrimination and retrogressive measures in all climate actions (i.e. mitigation, adaptation, finance, and damage from climate change).

Business Responsibilities

Reduce greenhouse gas emissions from their own activities and subsidiaries.

Reduce greenhouse gas emissions from their products and services.

Minimise greenhouse gas emissions from their suppliers.

Publicly disclose their emissions, climate vulnerability and the risk of stranded assets.

Ensure that people affected by business-related human rights violations have access to effective remedies.

Rights of Assembly & Climate Change Protests

Human rights of assembly and expression in relation to climate change protests have recently been the subject of both public debate and judicial action. Articles 10 and 11 of the ECHR guarantee rights of expression, assembly and association for environment and climate-related protests. These rights should only be restricted when there is a concern for public safety.

Civil Disobedience and Extinction Rebellion

Extinction Rebellion (XR) is an environmental pressure movement that uses civil disobedience and non-violent protest action to compel government action on the climate emergency, biodiversity loss and the risk of social and ecological collapse.1 They are active in countries worldwide, as well as Scotland and across the UK.2

Between 7 and 19 October 2019, XR coordinated "Autumn Uprising" protest action across various locations in the Metropolitan and City of London police areas.3 On 8 October 2019, the Metropolitan Police issued a Section 14 order of the Public Order Act 1986 limiting the protest action to Trafalgar Square.3 On 14 October 2019, the Metropolitan Police issued a revised Section 14 order requiring XR cease all their protests within London.

On 6 November 2019, The High Court of Justice ruled the order was unlawful.3 The judgement stated:

Separate gatherings, separated both in time and by many miles, even if co-ordinated under the umbrella of one body, are not one public assembly within the meaning of section 14(1) of the 1986 Act.

The High Court of Justice. (2019, November 06). Jones and Others v The Commissioner of Police for the Metropolis. Retrieved from https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Jones-Ors-v-Comm-of-Police-Approved-judgment.pdf [accessed 15 November 2019]

The conditions and regulations that can be imposed on rights of assembly in Scotland are discussed in SPICe blog: Marches and parades – frequently asked questions.

In light of the youth climate change protests and school strikes, the UN Human Rights Council adopted a resolution in March 2019 calling upon States:

To provide a safe and empowering context for initiatives organized by young people and children to defend human rights relating to the environment;

UN Human Rights Council. (2019, March 20). Recognizing the contribution of environmental human rights defenders to the enjoyment of human rights, environmental protection and sustainable development. Retrieved from https://undocs.org/A/HRC/40/L.22/Rev.1 [accessed 04 November 2019]

Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation

The UN Human Rights Council have stressed the importance of implementing a rights based approach to any climate action.1 A HRBA for climate action means that all policy design should occur with the fulfilment of human rights in mind. Efforts to adapt to climate change should incorporate human rights norms and principles such as the PANEL principles set forth by the Scottish Human Rights Commission. The UN Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights (OHCHR) stated in their Key Messages on Human Rights and Climate Change:

States must ensure that appropriate adaptation measures are taken to protect and fulfil the rights of all persons, particularly those most endangered by the negative impacts of climate change such as those living in vulnerable areas (e.g. small islands, riparian and low-lying coastal zones, arid regions, and the poles). States must build adaptive capacities in vulnerable communities, including by recognizing the manner in which factors such as discrimination, and disparities in education and health affect climate vulnerability, and by devoting adequate resources to the realization of the economic, social and cultural rights of all persons, particularly those facing the greatest risks.

Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights. (2015). Key Messages on Human Rights and Climate Change. Retrieved from https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/ClimateChange/KeyMessages_on_HR_CC.pdf

The UN Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights has warned that failure to mitigate and adapt to climate change may result in a "climate apartheid", where the wealthy can shield themselves from severe effects of climate change while people in poverty (those least responsible for climate change) are left most exposed to risks of extreme weather events, food insecurity, forced displacement and vector-borne disease.

On ensuring participation of affected groups in climate change action, the OHCHR stated:

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and other human rights instruments guarantee all persons the right to free, active, meaningful and informed participation in public affairs. This is critical for effective rights-based climate action and requires open and participatory institutions and processes, as well as accurate and transparent measurements of greenhouse gas emissions, climate change and its impacts. States should make early-warning information regarding climate effects and natural disasters available to all sectors of society. Adaptation and mitigation plans should be publicly available, transparently financed and developed in consultation with affected groups.

Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights. (2015). Key Messages on Human Rights and Climate Change. Retrieved from https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/ClimateChange/KeyMessages_on_HR_CC.pdf

Fairbourne, Wales