Frequently asked questions: session 6 new constitutional arrangements

This briefing provides answers to some frequently asked questions about new constitutional arrangements which have emerged as the UK has left the European Union.

Executive Summary

This briefing provides answers to some frequently asked questions (FAQs) about new constitutional arrangements which have emerged as the UK has left the European Union (EU).

Previous briefings in the series have considered FAQs in relation to the UK’s exit from the EU and what changed on 1 January 2021. The answers to the questions in this briefing are based on information available at the time of publication. The situation, and our understanding of it, will continue to evolve.

Key changes as a result of the UK’s exit from the EU

Has the Scottish Parliament’s competence changed as a result of the UK leaving the EU?

Yes. The Scottish Parliament still has legislative competence (the ability to make laws) in relation to devolved matters as set out in the Scotland Act 1998, but UK legislation passed during the EU exit process has made some changes to the Parliament’s competence. For example, the rule that required Scottish Parliament legislation to comply with EU law has been removed, and new UK Government Acts have been added to the list of Acts that the Scottish Parliament does not have competence to modify.

There have also been other legal and practical changes during the exit process that could affect the Scottish Parliament’s ability to exercise its competence effectively.

For example, the mutual recognition provisions in the UK Internal Market Act 2020, new international agreements, and common frameworks may all present challenges to how the Scottish Parliament can exercise its competence as a matter of law and/or in practice.

Has the UK leaving the EU given the Scottish Parliament more powers?

One of the big challenges of the UK leaving the EU was to decide who should govern areas previously decided by the EU. The UK Government identified over 100 areas where EU law and matters devolved to Scotland crossed.

Until 1 January 2021 the Scottish Parliament did not have the power to pass an Act if what it proposed was incompatible with EU law. This requirement has now been removed.

The result could be a significant expansion of the areas in which the Scottish Parliament could legislate.

However, the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 passed by the UK Parliament gives UK Government Ministers the power to make regulations which would stop the Scottish Parliament from being able to change the law (or give Scottish Ministers powers to do so) in an area that was formerly governed by EU law.

No regulations of this kind have been made as yet. UK Government Ministers are able to exercise these powers until 31 January 2022. Any such regulations made by UK Ministers would expire five years after they came into force.

See also who has the power to make laws in Scotland.

Who has the power to make laws in Scotland?

There are two different kinds of legislation (laws). They are known as primary and secondary legislation.

Primary legislation is an act of Parliament. For Scotland, primary legislation can be made by the UK Parliament and the Scottish Parliament. The Scottish Parliament makes laws in areas like health, justice and housing which are not reserved to the UK Parliament – these are known as ‘devolved matters’.

The UK Parliament is responsible for making laws on ‘reserved matters’. The UK Parliament can also pass laws on devolved matters if its wishes to, but it normally asks the Scottish Parliament for agreement before it does so, under the Sewel Convention. The Scotland Act 1998 sets out matters which are reserved. There is no formal list of matters which are devolved: whatever is not reserved is devolved.

Secondary legislation is a law created by Ministers (or sometimes other bodies like local authorities). To make secondary legislation, Ministers must have been given specific powers through an act (primary legislation). Ministers exercise these powers by making regulations or orders.

In some cases, it is either UK or Scottish Government Ministers that can make the regulations. But in other cases, both UK and Scottish Ministers have been given the same powers. This means that, in theory, UK and Scottish Ministers could each make regulations in the same area - these are known as concurrent powers.

What is the link between the UK leaving the EU and secondary legislation?

As a result of the UK leaving the European Union, many significant new acts (primary legislation) have been passed in the UK Parliament, and a smaller number in the Scottish Parliament.

These acts have given UK and Scottish Ministers many new powers to make secondary legislation in areas that were formerly governed by EU law. These new powers give Ministers the power to change policy in a significant way.

It is not just Scottish Ministers who now have these powers to legislate in devolved areas. In many devolved areas, UK Ministers have also been given powers.

In some cases, it is either UK or Scottish Government Ministers that can make the regulations. But in other cases, both UK and Scottish Ministers have been given the same powers. This means that, in theory, UK and Scottish Ministers could each make regulations in the same area - these are known as concurrent powers.

UK Ministers will not normally make regulations in devolved areas without the consent of the Scottish Ministers. In some cases that consent is a legal requirement, but not in all.

The Scottish Parliament cannot scrutinise secondary legislation laid at the UK Parliament even where the proposed changes to the law are in devolved areas. But it can scrutinise decisions by Scottish Ministers to consent to such legislation.

The Scottish Parliament scrutinises all secondary legislation made by Scottish Ministers.

Has the UK leaving the EU changed how laws on certain matters are made for Scotland?

While the UK was a member of the EU, many laws that applied in Scotland (and the rest of the UK) were made by the EU. Some of these laws were made by EU institutions and had direct legal effect throughout the UK. Others were implemented into Scots law by secondary legislation made by Scottish or UK Ministers.

Responsibility for making law for Scotland in these former-EU areas now lies with the Scottish and UK Parliaments. Many new powers to change the law in these areas by secondary legislation have now been given to Scottish and UK Ministers. (See ‘Who has the power to make laws in Scotland?’)

It is a significant change that UK Ministers now have powers to make secondary legislation that implements new domestic policy decisions in devolved areas.

See ‘What is the link between the UK leaving the EU and secondary legislation?’ and ‘Did UK Ministers have the power to make secondary legislation in devolved areas before EU exit?’

Did UK Ministers have the power to make secondary legislation in devolved areas before EU exit?

Yes, but on a more limited basis than now.

When the Scottish Parliament was established in 1999, UK Ministers’ powers to make secondary legislation in devolved areas were transferred to Scottish Ministers with only a few exceptions.

A key exception was the power to make secondary legislation that implemented EU obligations. Before EU exit, the UK Ministers regularly used that power, with the Scottish Government’s consent. However, that power was for implementing policy decisions that had been agreed at EU level rather than implementing the UK/Scottish Governments’ own policy. Beyond this key exception, the UK Government did not often make secondary legislation in devolved areas.

This has changed following the UK’s exit from the EU. UK Ministers now have the power to make secondary legislation in many devolved areas because UK legislation passed by the UK Parliament to deal with EU exit has given UK Ministers these powers.

Do Scottish Ministers have more powers to make secondary legislation as a result of EU exit?

Yes. Scottish Ministers have many new powers to make secondary legislation as a result of EU exit. These powers have been given to Scottish Ministers through primary legislation at both a UK and Scottish level.

Why does it matter that UK Ministers and Scottish Ministers have more powers to make secondary legislation?

The powers of UK and Scottish Government Ministers to make secondary legislation in certain areas are much more significant that they were prior to EU exit.

Noteworthy policy changes can now be made by secondary legislation. These include the kind of changes would previously have required the Scottish Parliament to consider primary legislation (i.e. a bill).

What happened to all the EU law that was in place in the UK?

Many of Scotland’s laws come from having been part of the EU. When the UK left the EU, there still needed to be laws in place in areas where EU law had applied.

The European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 changed EU laws which were in place in the UK into a new form of domestic law – known as retained EU law.

What is retained EU law?

We can think of retained EU law as a snapshot of the EU law which was in place in the UK at 11pm on 31 December 2020. That was the time at which EU law ceased to apply in the UK.

Retained EU law was created so that there was no gap in the law which applied in the UK immediately prior to and immediately after EU law stopped applying.

Some parts of retained EU law needed to be changed to ensure the law was clear and could work properly in domestic law (by “domestic law” we mean the law in the UK or in a part of the UK). For example, by removing references to the UK being a Member State, removing references to “euros” or replacing a reference to an EU institution with a reference to a UK or Scottish institution. This exercise of changing retained EU law to make sure that it worked properly in domestic law is known as deficiency correction.

How was retained EU law made?

One of the jobs of the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 was to create a new category of domestic law in the UK known as retained EU law.

To do this, the Act converted EU law, as it formerly applied in the UK, into domestic law as retained EU law.

Some of the EU law which was copied into domestic law as retained EU law needed to be changed to ensure that it worked properly in the domestic context. The process to make these changes was known as the deficiency correcting exercise.

What was the deficiency correcting exercise?

The deficiency correcting exercise is the process by which changes were made to retained EU law so that it would function effectively as domestic law in the UK.

If EU law as it was written pre-exit was simply copied and pasted into domestic law, then it wouldn’t work properly. It would contain elements that didn’t operate effectively in the domestic context, for example, provisions about the functions of EU institutions or provisions which were redundant when the UK was outside the EU. The elements that would not operate effectively are known as “deficiencies”.

A great deal of work was done to correct the “deficiencies” to make sure that UK laws work properly now that the UK is not a member state of the EU. In some cases, the changes were very small – removing references to euros, for example. In other cases, they were more significant – such as changes in regulatory regimes

This work is ongoing as some of the lower priority deficiencies still remain to be fixed.

How were deficiencies corrected?

Because so many laws needed to be changed in a relatively short period of time, UK Government Ministers and Scottish Government Ministers were given special powers which allow them to change the law to correct ‘deficiencies’.

These special powers which Ministers have come from the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018.

UK and Scottish Ministers change the law through secondary legislation. Secondary legislation made by UK Ministers is known as statutory instruments (SIs). Secondary legislation made by Scottish Ministers is known as Scottish statutory instruments (SSIs).

In some cases where the UK Government and the Scottish Government wish to pursue the same policy objective, the Scottish Government can ask the UK Government to lay statutory instruments that include provisions relating to devolved areas of responsibility. UK Ministers will not normally make such regulations in devolved areas without the consent of the Scottish Ministers.

The changes made by these kinds of regulations are often technical and are there to achieve legal continuity. However, these regulations have also been used to make more significant policy changes, for example by conferring new powers on UK and Scottish Government Ministers to make further secondary legislation.

These deficiency-correcting powers are time limited. They can’t be used after 31 December 2022. However, the changes to the law that have been made using these powers are not temporary and do not expire. Similarly, the new powers to make further secondary legislation that were conferred during the deficiency-correcting process do not expire.

Where Scottish Ministers wanted the UK Government to make deficiency-correcting changes on their behalf, they notified the Scottish Parliament by sending a Statutory Instrument (SI) notification under the statutory instrument protocol one .

What was statutory instrument protocol one?

The Scottish Parliament cannot scrutinise secondary legislation laid at the UK Parliament (unless the legislation is made under a special “joint procedure” and is scrutinised by both Parliaments, but this is very rare). The Scottish Parliament can, however, scrutinise the decision of Scottish Ministers to consent to the regulations being made by UK Ministers in devolved areas.

The process for the Scottish Government obtaining the Scottish Parliament’s approval was initially the statutory instrument protocol one agreed between the Scottish Government and the Scottish Parliament. The protocol was agreed in December 2018.

Protocol one applied to proposals for UK secondary legislation made under two powers in the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018:

to correct “deficiencies” in retained EU law and

to implement the Withdrawal Agreement.

Under protocol one it was the role of the Scottish Parliament to decide whether it was content with the Scottish Ministers’ proposal that a particular change to retained EU law would be made by UK Ministers rather than by Scottish Ministers themselves (or by both the Scottish Ministers and UK Ministers jointly). If the Scottish Parliament was content, the Scottish Government gave its consent to the UK Government and the UK Government then laid the legislation in the UK Parliament. The UK Parliament was then responsible for considering the statutory instrument which set out the exact wording of the change being made to the law.

The UK Government did not need the Scottish Government’s consent to make these regulations in devolved areas, but during the passage of the EU (Withdrawal) Act 2018 the UK Government indicated that it would normally seek such consent.

What is statutory instrument protocol two?

Protocol one was replaced by protocol two at the start of 2021. Whereas protocol one initially applied only to secondary legislation made under two powers in the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018, protocol two is applicable to all proposals to make UK statutory instruments which include devolved matters and which are in former EU law areas.

This protocol (like protocol one) sets the process agreed between the Scottish Government and the Scottish Parliament in order to give the Scottish Parliament a role in scrutinising the Scottish Government’s decisions to consent to devolved matters being included in Statutory Instruments (a form of secondary legislation) being made by UK Ministers rather than by Scottish Ministers.

Secondary legislation made by UK Ministers is scrutinised by the UK Parliament even where it changes the law in devolved areas.

What is the difference between protocol one and protocol two?

Protocol one related only to the decision of Scottish Ministers to consent to UK statutory instruments being made under two powers contained in the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018, the power to correct “deficiencies” and the power to implement the Withdrawal Agreement.

Protocol two applies more widely. It applies whenever the Scottish Government consents to devolved matters in former EU law areas being included in a UK statutory instrument. It therefore applies to powers given to UK ministers through a range of EU exit legislation, not just the two powers in the 2018 Act mentioned above. For example, it applies to many more of the powers in the 2018 Act, and to powers in the European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020 and the Direct Payments to Farmers (Legislative Continuity) Act 2020.

Common frameworks

What is a common framework?

A common framework is an approach agreed between the governments of different parts of the UK to a particular policy, including implementation and governance.

What do common frameworks do?

Common frameworks help to make sure that there is some degree of consistency in policy and practice in certain areas. Common frameworks are being developed to ensure that rules and regulations remain broadly consistent across the UK, in certain policy areas where consistency is considered desirable.

Why are common frameworks being developed in the UK?

The UK and devolved governments agreed that common frameworks would be needed after the UK’s exit from the EU to ensure that, in certain policy areas, there is no divergence or limited divergence between the nations of the UK.

During its membership of the EU, the UK and all of its governments were required to comply with EU law. This ensured that in many policy areas, including some that are devolved, a broadly consistent policy approach had developed across all four nations.

What is the Scottish Parliament’s role in relation to common frameworks?

As part of its scrutiny role, the Scottish Parliament needs to be able to consider the Scottish Government’s approach to the development of common frameworks.

The committees of the Scottish Parliament will lead on scrutinising those common frameworks that fall within their respective policy areas.

More information on common frameworks is available on the SPICe Common Frameworks Hub.

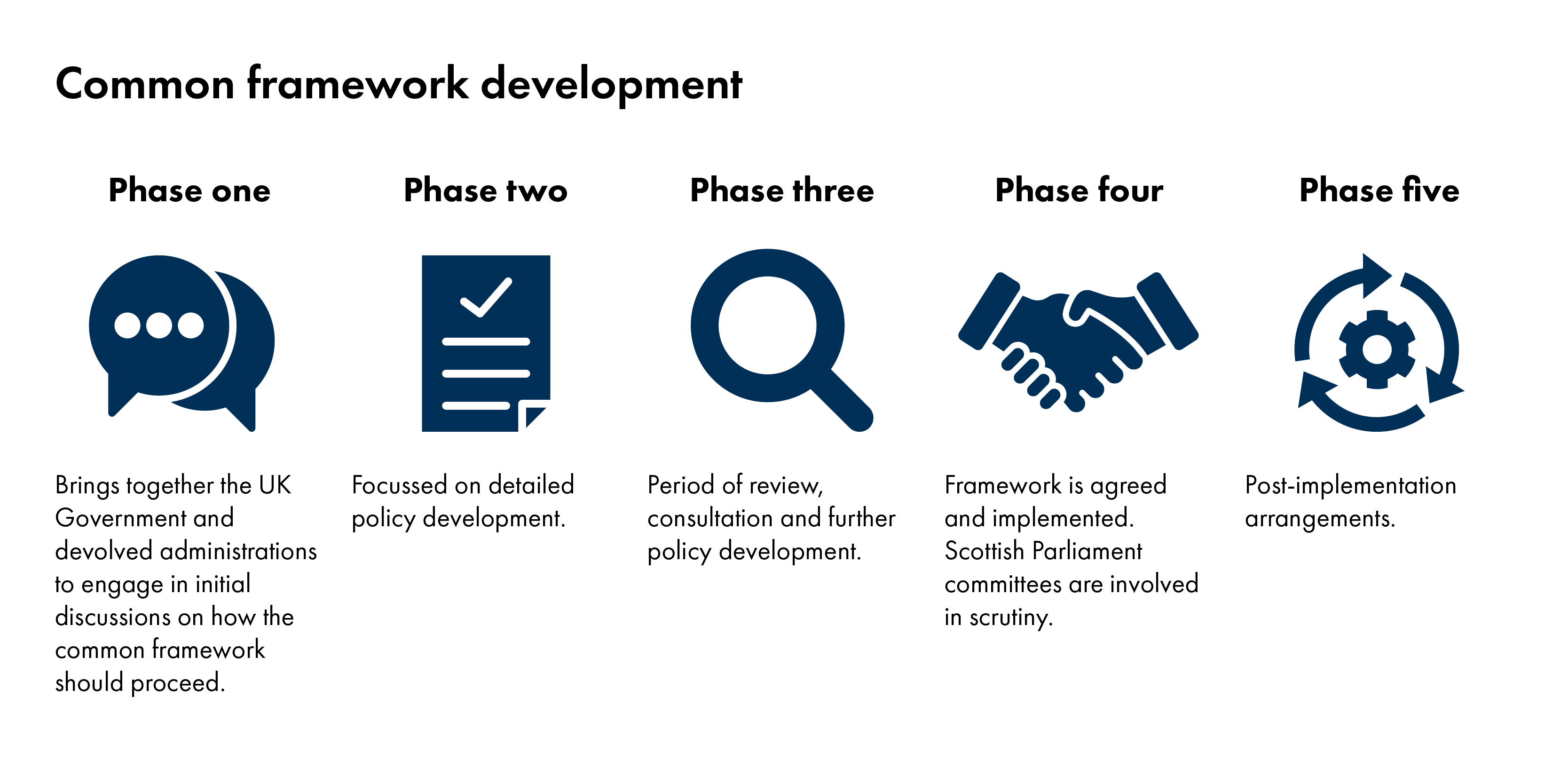

How are common frameworks agreed?

Frameworks go through five phases of development, and each framework will move at a different pace. The UK Government works with the devolved administrations at each phase to develop the frameworks.

What do common frameworks cover?

It is expected that there will be 28 common frameworks relevant to Scotland. Common frameworks on:

Nutrition Labelling, Composition and Standards;

Food and Feed Safety and Hygiene; and

Hazardous Substances Planning

have already been considered by the Scottish Parliament.

As frameworks come before the Scottish Parliament for scrutiny, they will be listed on SPICe’s common frameworks hub.

The UK Internal Market Act 2020

What is the UK Internal Market Act 2020?

The UK Internal Market Act 2020 was introduced in the UK Parliament by the UK Government in preparation for the UK’s exit from the EU.

The Act establishes two market access principles to protect the flow of goods and services in the UK’s internal market.

The Act also gives the UK Government a new power to spend in devolved policy areas such as:

economic development

culture

infrastructure (including health, education, housing and prisons)

domestic educational and training activities and exchanges and

international educational and training activities and exchanges including through the UK Shared Prosperity Fund.

What is the UK Shared Prosperity Fund?

As a member of the EU, the UK received money through the European Structural and Investment Funds programmes. The Shared Prosperity Fund is the UK Government’s replacement funding scheme. The UK Government has set out that the aim of the Fund is to reduce inequalities between communities across the UK.

What are the two market access principles in the UK Internal Market Act 2020?

The principle of mutual recognition, which means that goods and services which can be sold lawfully in one nation of the UK can be sold in any other nation of the UK.

The principle of non-discrimination, which means authorities across the UK cannot discriminate against goods and service providers from another part of the UK.

What is the effect of the UK Internal Market Act 2020 on devolution?

The market access principles in the Act have the potential to disapply devolved legislation and significantly reduce its impact.

Before the Act came into force, Scottish legislation in devolved areas could apply to all goods and services within Scotland. The Act means that goods and services produced in Scotland will be subject to Scottish legislation but those coming into Scotland from elsewhere in the UK will not be so long as they meet any regulatory standards in the place they originated.

Goods which originate in another country (i.e. outside the UK) but which meet the rules of the UK nation in which they arrive can then be sold across the UK. This means that goods which are imported first into another UK nation and transported from there into Scotland do not need to meet different Scottish rules and standards. As such, new UK bilateral trade agreements have the potential to increase the impact of the UK Internal Market Act 2020.

How do common frameworks and the UK Internal Market Act 2020 link?

UK Government Ministers have the power to disapply the market access principles set out in the UK Internal Market Act 2020 where the UK Government has agreed with one or more of the devolved governments that divergence is acceptable through the common frameworks process.

Although Ministers can disapply the market access principles in such circumstances, they are not obliged to do so.

UK and external relations and trade agreements

What is the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement?

The Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) sets out preferential arrangements between the EU and the UK, predominantly in the area of trade in goods.

The TCA’s governance arrangements provide wide-ranging powers for the European Commission and the UK Government in the management of the agreement. It also provides a limited role for the UK Parliament in partnership with the European Parliament.

Although the TCA does have an impact on devolved matters, no governance role is set out for the devolved administrations or legislatures.

What are trade agreements?

A trade agreement, or trade deal, exists when two or more countries agree to reduce or, in some cases remove altogether, trade barriers between them, allowing goods to circulate freely across the countries.

Modern trade agreements typically also involve commitments such as regulatory alignment or mutual recognition of standards. More detail is available in the SPICe briefing on the Anatomy of modern Free Trade Agreements.

Does the Scottish Parliament have a role in trade agreements?

The regulation of international trade is reserved by Schedule 5 of the Scotland Act 1998. However, implementing international obligations in relation to devolved matters is devolved.

The Scotland Act 1998 also enables the Scottish Government to assist the UK Government in relation to international relations, including the regulation of international trade, where it relates to devolved matters.

Prior to UK exit from the European Union, responsibility for the negotiation and scrutiny of trade agreements rested primarily with the European Union. As such, trade policy represents a new area of policy-making for UK legislatures and governments.

What are intergovernmental relations?

Intergovernmental relations (often referred to as IGR) are the processes through which governments interact. It is an umbrella term for both the formal and informal interactions and exchanges between governments.

Intergovernmental relations should allow administrations to work together in areas of joint interest or concern. In the UK, intergovernmental relations refer to the interactions between the UK Government and the devolved governments of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Communication, collaboration, information sharing, and the early resolution of disputes are all important aspects of effective intergovernmental relations.

Why are intergovernmental relations important?

In any system of multi-level government there will be some inter-dependence and overlap of powers and responsibility. In a country like Scotland, where some matters are the responsibility of the Scottish Government and others are the responsibility of the UK Government, intergovernmental relations are vital to effective governance.

There will also be areas of mutual interest and concern where working together, or sharing knowledge and resources, is beneficial. It is important that there are established processes by which to address and manage these areas of inter-dependence, interest and sometimes conflict.

How do intergovernmental relations operate in the UK?

The UK Government and the Devolved Administrations have been undertaking a review of intergovernmental relations. A progress report was published in March 2021. According to the progress report, all of the UK's governments agree that the intergovernmental process should:

facilitate effective collaboration and regular engagement between the governments in the context of increased interaction between devolved and reserved competence following departure from the EU.

The review also proposes a number of new intergovernmental structures including –

a replacement of the Joint Ministerial Committee with the UK Government and Devolved Administrations Council

engagement on cross-cutting issues, including an Inter-ministerial Standing Committee

portfolio engagement at official and ministerial level.

A standing intergovernmental secretariat will also be established to provide administrative support and promote the efficient and effective maintenance of relations at each tier and for the handling and resolution of disputes.

Does the UK still need to comply with the European Convention on Human Rights?

Yes. The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) is an international treaty. It sets out rights and guarantees for people. Any state which has signed up to the ECHR commits to respect the rights and guarantees which it contains.

Members states of the Council of Europe have signed the ECHR. The UK is one of those countries. In the UK, rights under the ECHR are protected by the Human Rights Act 1998. The Council of Europe is separate from the EU, so although the UK has left the EU, it is still a member of the Council of Europe and is still signed up to the ECHR.

The European Court of Human Rights hears cases related to the ECHR. It is separate from the European Court of Justice, which is the court of the European Union.

Is the Scottish Parliament bound by EU law?

No. From 1 January 2021 the Scottish Parliament no longer has to legislate in a way which is compatible with EU law.

Scottish Ministers have indicated that in some areas they would like to see Scots Law continue to align with EU law.

Scottish Ministers have powers to allow them to make regulations (secondary legislation) with the effect of continuing to keep Scots law aligned with EU law in devolved areas (See what is the keeping pace power?)

What is the keeping pace power?

Part 1 (section 1(1)) of the UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Continuity) (Scotland) Act 2021 gives Scottish Ministers powers to allow them to make regulations (secondary legislation) with the effect of keeping Scots law aligned with EU law in devolved areas. This is known as the ‘keeping pace power’.

Will Scots law keep pace with EU law in all areas?

No, not necessarily. Scottish Ministers can make regulations so that Scots law keeps pace with EU law, but they are not required to do so.

In some areas, for example, where the Scottish Ministers have signed up to a common framework, they would be unlikely to exercise the keeping pace power in a way that was inconsistent with the common framework.

What is the Scottish Parliament’s role in relation to the keeping pace power?

Secondary legislation in the form of regulations will come before the Scottish Parliament for scrutiny when Scottish Ministers exercise their power to keep pace.

It will, however, be a challenge for the Parliament to work out where Scottish Ministers have decided not to keep pace with EU law.

Do Scottish Ministers have to report on their use of the keeping pace power?

Yes. Scottish Ministers must lay reports (first in draft form for consultation and then a final version) before Parliament on the intended and actual use of the keeping pace power.

There are two forms of reporting to Parliament, a Policy Statement and an Annual Report.