Anatomy of modern Free Trade Agreements

Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) can regulate a range of matters beyond the basic commitment to liberalise trade in goods by removing tariffs. This overview of two recent FTAs illustrates how states can take advantage of these treaties to achieve deeper economic and policy integration. It is topical to look into these arrangements, because the UK could embark on the negotiation of new FTAs after Brexit. This briefing explores the range of matters that modern FTAs can cover.

About the Author

Filippo Fontanelli is SPICe Academic Fellow in international trade law and adviser to the Scottish Parliament Committee on Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Affairs. He is Senior Lecturer in International Economic Law at the School of Law at the University of Edinburgh.

Executive Summary

After exit from the EU, the UK is likely to leave the EU's external trade policy, and will be able to negotiate free trade deals in its own right. Trade treaties can vary in scope and ambition, and can touch upon several areas of international relations.

This briefing seeks primarily to map the matters that two parties may wish to regulate through a Free Trade Agreement, using the Canada-EU and the Japan-EU agreements as templates.

Key aspects of these Agreements include:

Modern FTAs favour deeper integration that exceeds the mere exchange of trade concessions.

FTAs typically liberalise virtually all trade in goods, providing preferential access to the market of the other member(s).

For agricultural products, liberalisation is not complete across the board, but FTAs achieve at least an improved treatment of imported products, for instance increasing tariff-rate quotas.

FTAs seek to align the product specifications of the participating countries, to facilitate trade in goods that are subject to safety, technical and sanitary standards. If regulatory alignment is not achieved, mutual recognition of each other's standards is encouraged.

In relation to services and access to public procurement, FTAs are mainly helpful because they lock in current concessions and prohibit future discriminatory measures.

FTAs might contain rules on the protection of foreign investments, but they do not always provide pre-establishment guarantees, or access to international arbitration to investors wishing to protect their investments and seek compensation for governmental interference.

The conclusion of FTAs can serve as a platform for each party to commit to the protection of the other party's Geographical Indications.

FTAs can confirm the parties' pledges relating to topics like: labour standards, environmental protection, basic human rights, corporate governance, and cooperation in the fight of transnational crimes. Obligations relating to these matters can also contribute to each country's commitment towards sustainable development.

Appendix A contains a Glossary, explaining the meaning of certain technical terms and expressions that are ubiquitous in all commentary on Brexit and international trade. To facilitate understanding, each entry comes with two examples of its usage in the recent news coverage about Brexit. Some hyperlinks in the text will lead to the Glossary for the clarification of the terms used.

Introduction

Depending on the terms of Brexit, the UK could be in the position to negotiate and agree free trade deals with third countries.

It is helpful to understand what bilateral trade agreements look like. Especially in the practice of the European Union (EU) in recent years, these agreements have included rules that reach much beyond the liberalisation of trade in goods and services.

This briefing offers an introduction to the nature of Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) and breaks down the content of two recent agreements concluded by the EU with Canada and Japan.

UK's external trade policy after Brexit

As a Member State, the UK rules on international trade are governed by the law of the EU. The EU has a common foreign trade policy (the EU Common Commercial Policy), and the member states have assigned to the EU the power to shape and implement it on behalf of them all.

Accordingly, the EU coordinates the commitments of all the member states under the rules of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and in free trade agreements between the EU and third countries. For instance, the European Commission determines the common external tariff applicable to all goods imported into the EU customs union, irrespective of the ports of entry. The EU also chooses the countries with which it seeks to have a preferential relationship, through a free trade agreement.

Upon exit from the EU, the UK's freedom to steer its external trade policy autonomously will increase. Certain tasks are of particular importance:

Re-defining the UK's commitments under the WTO. The UK must decide whether it will retain the same obligations that it now observes as member of the EU.

Replacing or replicating the trade agreements between the EU and third countries. Losing EU membership will entail the UK losing the trade advantages under those agreements. A process of "roll-over" or transitioning of these agreements would help avoid an abrupt disruption of trade practices upon exit. The UK Government is seeking to roll-over the current EU agreements, concluding separate treaties with the third countries that are ready to enter into force on exit day. 1

Negotiating new trade agreements with third countries. The UK must decide, upon leaving the EU customs union, which partners it wishes to approach to conclude preferential deals. The choice will have strategic implications. On the one hand, if the UK achieves a deal with the United States (or Australia, or China) before the EU does, UK businesses will enjoy a competitive advantage in the US market over their competitors from the EU. On the other hand, if a quick deal between the UK and the US were achieved, it would change the framework of the negotiation between the UK and the EU about their future relationship.

This briefing focuses in particular on the negotiation of bilateral free trade agreements. In particular, it addresses what areas trade agreements cover.

In practice, the UK's margin of autonomy in these matters will be largely determined by its future relationship with the EU, possibly commencing after a transitional period during which everything will stay the same even after Brexit. Depending on the EU-UK future relationship, certain external trade policies can be foreclosed - this is more fully explained in the section "What kind of Free Trade Agreement for which kind of Brexit."

What are Free Trade Agreements and what is their function?

Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) are international agreements between two or more countries. Their primary function is to establish preferential market access between its members. For instance, goods originating from an FTA member country could be imported into another FTA member countries without paying custom duties.

Such access is more favourable than the treatment reserved to goods originating from a non-FTA country. Outside FTAs, importing and exporting countries trade under the rules of the World Trade Organisation (WTO). WTO members have bound themselves to a maximum (capped) rate of tariff for each kind of goods, and must apply the same tariff rate to all imported goods irrespective of their origin. Because the WTO does not permit discrimination among trade partners, the capped tariff rate is referred to as Most-Favoured Nation (MFN) rate. Tariffs at the MFN rate or lower apply to all imported products. In this respect, the preferential treatment granted by an FTA is an exception to the principle of MFN treatment. Some countries are, on account of their belonging to an FTA, more favoured than others.

MFN tariff v. preferential trade inside an FTA

Example 1: WTO law allows Canada to impose a custom duty of up to 8% on imported cigars. Instead, cigars from the EU enter the Canadian market at no duty, under the terms of the Canada-EU FTA (CETA).1

Example 2: honey travels duty-free across the borders of the members of the EU, because the EU established a free trade area on its territory. However, honey imported from the US might face a custom duty of up to 17.3%.2 Moreover, the EU grants duty-free access to honey from dozens of countries, under free trade agreements or similar arrangements.

Example 3: normally, cars imported into the EU incur a tariff at the border. Under the EU-Japan agreement, Japanese cars enter the EU market at no duty. Before the EU-Japan agreement, Japanese manufacturers could avoid duties by assembling the cars in the territory of the EU. Now, that arrangement is no longer necessary. Honda has announced a plan to close plants in the UK , which might be motivated, at least in part, by this. BBC business editor Simon Jack says the trade deal certainly "means a dwindling rationale to base manufacturing inside the EU."3

Tariffs are not the only trade barrier that FTAs can reduce or remove. WTO law prohibits quotas and other quantitative restrictions of trade, but tariff-rate quotas exist and might be modified in favour of FTA partners. Non-tariff barriers also exist in the form of domestic regulations, like sanitary requirements for foodstuffs or technical specifications for products.

Besides goods, FTAs can concern trade in services, although they often fail to secure concessions that are significantly higher than those already granted under the WTO. In the WTO, states have exchanged promises to open their services markets to foreign services and providers. The terms and extent change from state to state. Normally, parties to a FTA attempt to secure concessions in areas where there is no WTO commitment. For instance, a state that has made no promise regarding educational services under the WTO has no obligation to open its market to foreign providers (e.g., foreign universities willing to open a branch on its territory). In the framework of a bilateral FTA, the same state might offer preferential rights to educational services and providers from its trade partners.

As explained in this briefing, FTAs are often used to regulate matters that go beyond trade in goods and services.

Types of FTAs

Reciprocal and non-reciprocal

FTAs are normally reciprocal: the member countries exchange trade concessions and open their markets to each other's products and services.

The WTO also enables its members to grant trade favours unilaterally. Unilaterally granted preferences would breach the non-discrimination principle of the MFN, but they are allowed if they benefit developing countries. For instance, the EU has a scheme whereby it grants duty-free or preferential access to most goods from 27 low-income countries (under the Standard General System of Preferences1 and the GSP+2) and free access to all goods other than arms from a further 49 least-developed countries (under the Everything But Arms scheme3). These schemes operate without reciprocity: the beneficiary countries are not expected to extend a corresponding preference to goods from the EU. Instead, the beneficiaries are often required to adopt acts such as ratifying human rights treaties and adopting good government standards, if they want to access the preferential treatment.

Standard FTAs and deep integration FTAs

The content of FTAs has expanded and deepened over time. FTAs establish preferential trade relationships between its members. Besides basic rules relating to tariff rates and rules of origin, FTAs can include trade-related rules that expand on the disciplines of WTO law. For instance, FTAs normally regulate trade in services, the protection of trade-related aspects of intellectual property rights and the discipline of the trade remedies against unfair trade practices (like dumping and prohibited subsidies).

In addition, FTAs increasingly contain sections that do not regulate matters falling within the WTO's reach. By including these matters, the parties signal the intention to establish, through the FTA, a relationship of deeper integration going beyond trade-related matters and reaching into their economic and political choices. Modern FTAs like the EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement and the Canada-EU Comprehensive Economic and and Trade Agreement (CETA) include several chapters regarding these extra-WTO topics, and are examined more fully below.

Bilateral and plurilateral FTAs

FTAs can be concluded between two parties, like the EU-Japan EPA or the US-Korea FTA. Other times, more than two countries are members ("plurilateral"). This is the case for the EU, which currently counts 28 members, the North-American FTA (NAFTA) concluded between Mexico, Canada and the US, or MERCOSUR, concluded between Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay and Venezuela (Venezuela is currently suspended from the agreement).

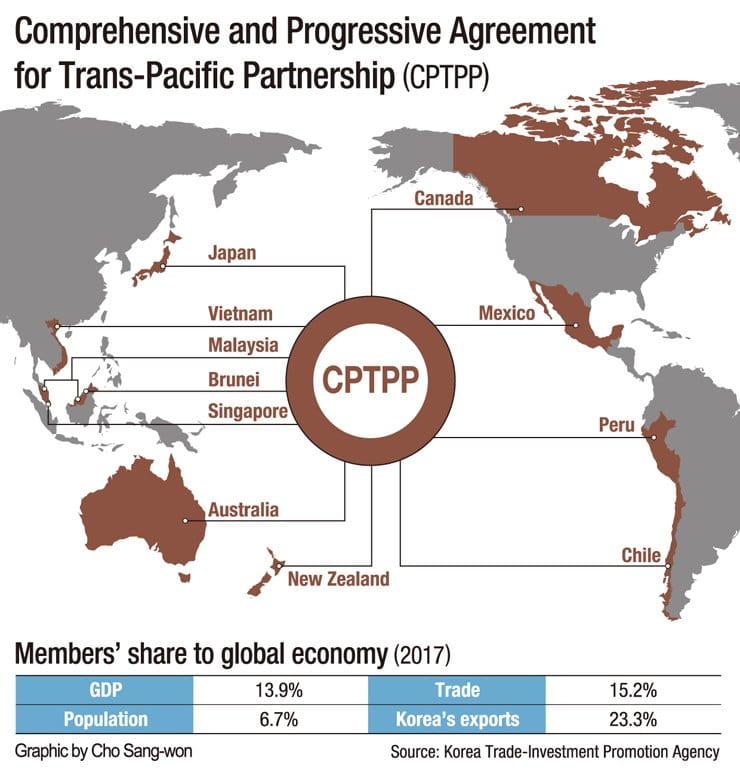

The above mentioned plurilateral FTAs have a distinct regional character: they include adjacent countries. However, attempts have also been made to conclude FTAs between countries that are not in the same region. Currently, after the US abandoned the negotiation of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the remaining 11 countries have concluded a Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). The membership of the agreement, as evident from the map below, does not follow any regional pattern.

The content of deep FTAs: WTO-plus and WTO-extra sections

Deep integration FTAs, which are now fairly common, include regulation both of matters already governed by WTO law and of other matters outside the remit of WTO law.

When FTAs regulate matters already governed by WTO law, they build on the baseline of WTO law and prescribe additional obligations to increase market openness or coordination. For instance, FTAs can require the reduction or abolition of tariffs that are permitted under WTO rules, or establish a regime of mutual recognition of product standards, which can spare exporters from complying with the regulations of the country of importation. Other such topics include: trade remedies (anti-dumping measures; countervailing measures against subsidised imports); trade in services; public procurement; sanitary and phytosanitary measures; technical barriers to trade; trade-related aspects of intellectual property rights and trade-related investment measures.

FTAs can address trade and non-economic matters for which there is no WTO baseline. They range from topics that are closely connected to international trade, like the protection of foreign investments and the regulation of antitrust, to topics bearing no direct relation to trade. The latter can include cooperation in criminal matters, immigration policies, the upholding of labour, human rights and environmental standards, and the promotion of sustainable development. In some respects, when negotiating parties include these matters in FTAs they are ready to accept that trade may decrease as a result When states promote labour standards and ban the products of child labour, they deliberately block trade in certain goods. When states promote environmental protection and prohibit the relaxation of certain standards, they deliberately accept to forfeit those foreign investments that the relaxation would have attracted. Inclusion of these matters in FTAs does not serve economic liberalisation, but the different goal of aligning the states' policies. In this manner, FTA members signal their common views regarding non-economic values.

What kind of Free Trade Agreements for which kind of Brexit

This background briefing presents the content and function of deep FTAs such as those between the EU, and Canada and Japan. Whether the UK will be in the position to achieve a similar deal after exit day, however, will depend on the intended terms of its future relationship with the EU.

At the time of writing, the terms of Brexit are not known. The UK could retain absolute autonomy in shaping its foreign trade policy, if it cut all ties with the EU. Conversely, a close trade relationship with the EU, such as forming a Customs Union with the EU's Custom Union (like Turkey), would constrain the UK's power to negotiate trade deals with other countries.

No-deal

In a ‘hard Brexit’ scenario – with the UK and EU parting ways without achieving any agreement on the terms of the UK's departure and the UK-EU future relationship – the UK could exercise its external trade policy freely, subject only to WTO rules. Under WTO law, the main condition for FTAs to be lawful is that they cover substantially all trade (in goods; for services it is sufficient that the FTA have substantial sectoral coverage). In other words, the UK could not negotiate an FTA in which it could pick and choose which sectors to liberalise (e.g., dairy products and steel) and on which to retain tariffs (e.g., textiles and meat). An FTA must result in a genuine area of generalised free trade. In this scenario, the UK would be free to negotiate comprehensive deals such as the EU-Canada and the EU-Japan agreements.

Customs Union

The UK would have this freedom limited if it joined in a customs union with the EU after exit. Inside a customs union, goods can cross borders between its members without incurring tariffs. In a hypothetical UK-EU customs union, French wine could come into Scotland duty-free, just like Scottish salmon imported into Germany. Customs unions, however, require also that the members coordinate their external trade policies, to avoid tariff-circumvention. If the members of a customs union could retain different tariffs on imports from third countries, it would be possible for exporters to enter the market of the customs union through the entry point applying more favourable duties, and then move goods around its territory at no additional cost. This is why, for instance, EU and Turkey's customs union not only removes tariffs on goods exchanged between them (except food and agricultural products) but also creates a set of coordinated external tariffs. Goods from the US will incur the same tariffs whether they enter into the customs union from Turkey or Italy. This external arrangement makes customs unions different from simple FTAs, which require sophisticated rules of origin to trace the origin of goods travelling across their markets.

The EU and Turkey's customs union can illustrate how the arrangement affects the external trade policy of the participating members. The EU can conclude FTAs, like those with Canada and South Korea. Because of the customs union with Turkey, goods from these third countries, through the EU, can enter Turkey duty-free. The converse is not true: Turkish goods do not benefit from the EU deals. Turkey can conclude independent FTAs with these countries, but its negotiating power is reduced, because these countries already have obtained market access to Turkey. To convince Canada to give duty-free access to Turkish goods, Turkey must formulate new trade concessions.

Customs unions only cover trade in goods. When not all goods are covered, it is possible to speak of an incomplete customs union (but always meeting the “substantially all trade” condition, see above). It is possible for its members to negotiate trade deals with third parties about the sectors left unregulated by the incomplete coverage of a customs union; for example, trade deals can also include areas in addition to trade in goods, like trade in services and foreign investments.

EEA membership

Another scenario would be UK's participation in the European Economic Area, the agreement extending the EU's single market to three members of the European Free Trade Association (Norway, Iceland, and Lichtenstein). This is often labelled as the “Norway-model” or “EEA” option. Should the UK join EFTA and, subsequently, the EEA, it would effectively remain in the single market and would recognise its four freedoms (movements of goods, services, workers and capitals). It would not lose the power to conclude free trade agreements with third countries, if it opted-out of negotiating them together with the other EFTA members. The EEA does not form a customs union between the EFTA states and the EU, and therefore requires rules of origin to determine that a certain good originates from the EEA and therefore can enter the EU at no duty.

Note that in the so-called “Norway-plus” scenario, the “plus” component would refer to a customs union with the EU: this scenario would influence the UK's external trade policy. A slight variation of this model, the “Common Market 2.0” hypothesis, tries to prevent the loss of external trade policy autonomy by adding onto the Norway model a “temporary” customs arrangement with the EU that could lapse once new systems are put in place to ensure frictionless trade across the Irish border, to solve and go beyond the so-called backstop plan. Thereafter, the UK could negotiate free trade agreements autonomously.

Canada model

Another option is the so-called Canada model. The UK could conclude with other parties, including the EU, a trade agreement comparable to the agreement between Canada and the EU (CETA). The UK would then establish agreements liberalising trade in goods and services, without going as far as pledging mutual recognition to foreign standards, or granting to foreign workers freedom of movement to the UK territory. A CETA-like agreement between the UK and the EU, moreover, would not constitute a common customs union and would, therefore, leave ample margin for the negotiation of further deals by the UK.

Ultimately, the nature of the UK's future relationship with the EU will influence its ability to negotiate new trade agreements with other countries, and vice versa. There will be a sequencing issue: a plan of deep economic integration with the EU would reduce the negotiating margin with other countries. Conversely, a hypothetical deal with the likes of US and Australia, if achieved quickly, would make it harder to subsequently reach a customs union arrangement with the EU.

Anatomy of two deep FTAs: CETA and EU-Japan EPA

This section of the briefing provides an overview of two deep integration FTAs concluded by the EU in recent years. These are the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement between Canada and the EU (CETA) and the EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA).

After nine years of impact studies and negotiation, CETA was signed in October 2016 and, pending its ratification by all member states of the EU, all its chapters have provisionally entered into force, except the one on investment protection and some other provisions. The EU-Japan EPA entered into force on 1 February 2019, together with the Strategic Partnership Agreement (SPA) between the same parties. The negotiations were launched in March 2013.

A brief account of these FTAs' main elements may provide a template for modern FTAs, including those that the UK could conclude in the future. The topics discussed here do not exhaust the range of matters governed by FTAs but are selected to give a comprehensive picture.

Trade in goods

Both CETA and the EU-Japan EPA include rules to expand the trade in goods between its parties. This goal is pursued through the elimination or reduction of tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade.

Custom Duties and Trade Facilitation

As discussed previously, the WTO allows only FTAs that liberalise ‘substantially all trade’ in goods between them. There is no numerical benchmark, but it is expected that the participating countries reduce or eliminate tariffs on most products. The negotiation process typically focuses on goods for which the WTO-bound tariff rate is quite high, as it is often the case on agricultural products. A significant reduction in tariffs on those products yields a significant advantage to goods originating from FTA countries over goods from third countries, trading under the Most Favoured Nation terms (that are not preferential).

CETA prescribes the elimination of almost 99% of the tariff lines for Canada and the EU.1 In the agricultural sector, where tariff spikes are more common, the elimination of tariffs covers around 90% of all products. In the EU-Japan EPA, the EU has abolished custom duties on 99% of its tariff lines, and Japan has done the same on 97% of its ones.2 Sensitive products might be excluded from duty-free treatment under FTAs. For instance, the EU-Japan EPA contains no commitment on rice and seaweed (two sensitive sectors of the Japanese industry) nor on whale products (that are prohibited in the EU).

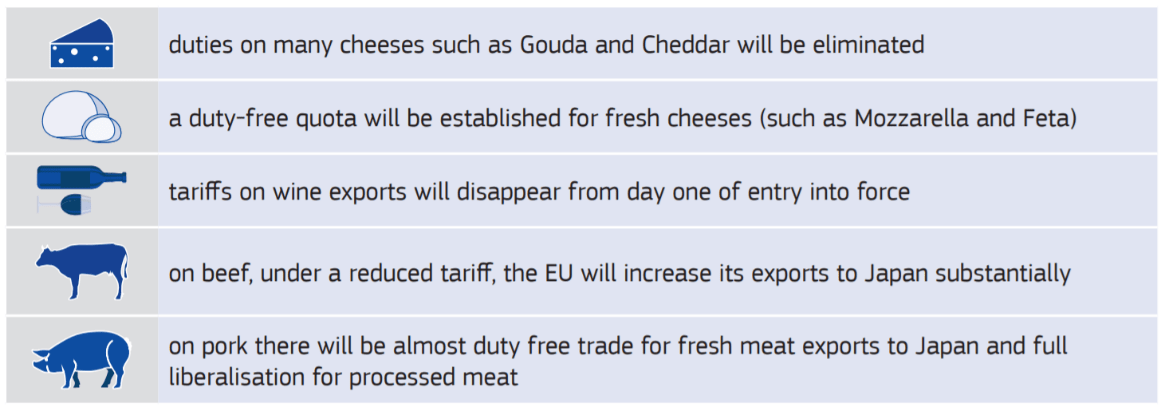

Cheese for cars

In the negotiation of the EU-Japan EPA, the parties focused on removing barriers hindering trade in certain strategic exports. The EU sought to increase access to the Japanese markets for its food products. Conversely, Japan wanted to support its automotive industry's exports into the EU market. The FTA, therefore, came to be known as the ‘cheese for cars’3 pact, and its terms were advertised accordingly. The image below shows how the Commission illustrated the advantages of the new agreement. In exchange for these market access concessions, the EU committed to phase out over seven years its 10% tariff for Japanese cars and to eliminate immediately tariffs on most car parts.

Besides reducing custom duties, both FTAs include a chapter on customs procedures and trade facilitation. Through these rules, the parties commit to cooperate closely to facilitate customs procedures, avoid unnecessary delay in the release of goods, and explore the use of automated procedures to speed up clearance. Both treaties also provide for the importing country's duty to issue advance rulings on tariff classification, to enhance transparency and predictability of the customs-clearing process.

Agriculture

Tariff concessions on agriculture are typically harder to achieve. In the EU-Japan EPA, Japan has liberalised 84% of tariff lines in agricultural products and 73% of the tariff lines in processed agricultural products like pasta, chocolate and sugar confectionery. Japan also abolished its 15% tariff on wines. Japan granted duty-free status to several Geographical Indication cheeses and increased the duty-free or low-duty quotas available to several dairy products from the EU.

Gradual liberalisation of trade in processed agricultural products

Before concluding the EU-Japan EPA, agricultural goods imported into Japan from the EU incurred the MFN tariffs at the border. Japanese MFN rates were characteristically high on agricultural goods, in particular processed agricultural products (PAPs). For instance, 30-40% on cheese, 38.5% on beef, up to 24% on pasta and up to 30% on chocolate. 1

The EU granted free access to virtually all incoming Japanese agricultural goods, with the exception of rice. Japan's tariff concessions covered around 6 billion Euros in trade, and 98% of the current trade in processed agricultural goods. The EU-Japan EPA set up a system of gradual liberalisation:

The EU-Japan EPA is the very first agreement in which Japan will fully liberalise within a timeframe of 10 years tariffs for pasta, sugar confectionary and chocolates. Tariff elimination at entry into force (EIF) is granted for a number of interesting products like egg albumin (MFN 8%, average annual trade value of 64 million Euro), protein substances (MFN 5.1%, trade value 39 million Euro, average trade value of 39 million Euro), lactose (MFN 8.5%, average trade value of 35 million Euro), caseinates (MFN 5.4%, 23 million trade value) and yeasts (MFN 10.5%, trade value 11 million Euro). Tariffs for starch derivatives, sorbitol and glues will be liberalised over a maximum of 10 years. The Agreement provides very sizeable [tariff-rate quotas] for other PAPs such as wheat or barley related food preparations, wheat flours, mixes and doughs and coffee preparations.2

Likewise, Canada has liberalised almost 91% of its agricultural tariff lines. While some sensitive products were excluded from the concessions (poultry meat, eggs and egg products), Canada's concessions on processed agricultural products are comprehensive. In particular, the EU obtained duty-free access for its wine and spirits. For certain products like cheese, dairy, beef and pork, the parties have increased the tariff-rate quotas (TRQs) available. In so doing, they have retained the right to impose custom duties, but only on the imports exceeding the pre-determined amount of the quota. For instance, Canada doubled the quota reserved for EU cheeses, which the European Commission predicts could result in a 128% increase of EU exports.

Rules of Origin

In the context of FTAs, only goods originating from within the participating countries circulate freely. Goods from third countries, instead, might incur custom duties and undergo other checks, for instance safety inspections. Therefore, customs authorities must verify the provenance of goods to identify the applicable treatment. Rules of Origin (RoO) must be established for this purpose.

This determination might be difficult when goods travel across countries and contain components (‘inputs’) of various provenance (for instance, a German car with a Korean engine and leather seats made in Italy). RoO normally require a minimum percentage of a good's inputs to come from a certain country, for that good to claim that origin. RoO also regulate the issue of shipment (clarifying when shipment through third countries affects the good's origin) and dictate which documents must accompany the goods to certify their origin.

For instance, the RoO in CETA specify that goods originate from the EU or Canada when they are wholly obtained in their territories, or when they are produced exclusively from materials originating therein. Alternatively, the criterion of ‘sufficient process’ applies. For instance, a car is considered to originate from the EU or Canada when no more than 50% of the value of the materials used in its manufacturing were imported from outside the EU or Canada.

The RoO in the EU-Japan EPA are largely similar, but contain a more specific section on cars and car parts. After a transition period, the maximum amount of inputs from third countries into a car will be 45%. The FTA contains also a mechanism aimed at facilitating the proof of origin on the part of the manufacturers, without relaxing the RoO thresholds.

Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT)

Technical regulations can represent a trade barrier. For instance, voltage requirements for household appliances can limit their tradability across countries with different standards.

Convergence towards common standards on safety, health and consumer protection, possibly produced by international standardisation bodies, can help eliminate unnecessary trade barriers. Alternatively, trading countries could mutually recognise each other's standards as satisfactory. In so doing, the importing country would spare the imported products from compliance with its domestic standards, as long as the standards of the country of origin are observed. The WTO agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) requires WTO members to enforce only technical measures that are necessary to pursue their goal, and encourages members to follow international standards.

The EU-Japan EPA provides clarity in the identification of the international standardisation bodies and, for instance, points to the Codex Alimentarius standards on labelling of food, a document produced by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) together with the World Health Organisation (WHO), two United Nations specialised agencies. 1 This is a convenient reference for EU exporters that have so far struggled to comply with Japanese labelling requirements. Products that must observe specific standards (for instance, health standards or labelling standards) must obtain a certification of compliance by the national certifying bodies before they can be sold on the marketplace. CETA authorises the competent bodies of EU and Canada to issue certifications based on the standards of each; for instance, the Canadian authorities could certify a product's compliance with EU standards. In so doing, exporters can apply for their products the required certification at the place of production rather than that of export - a convenient arrangement.

In addition, both treaties contain a section on mutual recognition, listing the sectors (e.g., medicines2) in which the importing party acknowledges the satisfactory standard of the exporting party's inspections at the stage of manufacturing, and waives the right to test the goods upon importation.

Automotive standards in the EU-Japan EPA

In the field of automotive goods, the EU-Japan EPA developed an advanced regime of regulatory alignment. The system relies both on mutual recognition and the approximation of the standards. Namely, the EU and Japan commit to align their safety and environmental standards to the international ones – developed by UNECE.3 In so doing, they ensure that the same standards will apply in the two markets. This commitment paves the way for the mutual recognition of the conformity assessment procedures and inspections carried out in the territory of each party, and will spare imported cars from testing and certification procedures in the market of destination.

The EU has reserved the right to reinstate its pre-agreement tariffs on cars (10%) should Japan reintroduce regulatory barriers affecting the importation of cars from the EU.

Sanitary and Phytosanitary measures (SPS)

Like technical standards, sanitary and phytosanitary requirements can result in trade obstacles, when a product already cleared for circulation in the exporting market must also undergo testing and certification in the importing one. The SPS agreement of the WTO requires that SPS measures be scientifically sound and necessary.

Deep FTAs routinely include provisions on SPS measures, but closer integration does not result in the relaxation of domestic standards. Both CETA and the EU-Japan EPA reaffirm the parties' right to impose domestic SPS requirements and block products that do not conform to them.

Besides some commitments regarding transparency and cooperation, both FTAs contain the obligation for the importing country to accept the SPS measures of the other party if they demonstrably achieve the desired level of health protection. In other words, requirements that guarantee an ‘equivalent’ level of protection will spare the imports from testing and certification procedures.

The importing party, at its own expense, can also carry out audits and inspections in the facilities of the exporting party. Through this process, manufacturing facilities can be ‘pre-listed’ and authorised for exports without facing checks at the point of importation.

The precautionary principle

The SPS standards in North America and the EU sometimes diverge. Cases in point are the regulations on the use of genetically modified organisms in food, the marketing of hormone-fed beef meat or chlorine-washed chicken, and the use of glyphosate as fertiliser. In essence, the commonly held view is that the approach to risk assessment is different in Europe from the one used in North-America. Accordingly, it is often questioned whether the EU, by concluding FTAs with other countries, would be forced to open its market to goods that, using a precautionary approach, it considers potentially harmful.

In the preamble of the joint interpretative instrument annexed to CETA, the EU and Canada have reaffirmed ‘the commitments with respect to precaution that they have undertaken in international agreements.’ The EU has also confirmed that CETA does not diminish its right to set the level of protection for its citizens’ health that it considers appropriate. For instance, the EU has confirmed that the ban on hormone-fed beef will continue after CETA's entry into force. It is worth pointing out that, in the past, this ban was found to breach WTO rules, and only recently has the EU convinced Canada and the US to stop inflicting retaliatory trade measures. In exchange, the EU has granted a sizeable increase in the quota of (hormone-free) beef importable duty-free into the EU from the two countries.

Trade in Services

WTO law governs trade in services, but the rules of the WTO's General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) do not establish a standard set of obligations. Trade in services is not hindered by tariffs, but by laws and regulations on the provisions of services. These regulations can restrict foreigners' ability to provide services in the importing country. It is for each country to decide to what extent it wishes to liberalise its services market, and in which sectors (health, education, banking, etc).

FTAs build on this set of customised commitments and expand the FTA parties' liberalisation obligations in favour of foreign services and service providers. Normally, FTAs do not secure across-the-board liberalisation in services, and contain only a modest improvement compared to the GATS baseline, relating to specific services.

The EU-Japan EPA has not introduced new market access concessions, but has contributed to the consolidation of the current level of liberalisation into binding commitments. In so doing, the parties have agreed that liberalisation in services could only increase in the future, by locking in current concessions and future ones as they might be granted. A similar mechanism is included in CETA, which also secured certain limited concessions in specific sectors of the Canadian market (namely maritime transportation and uranium investment). CETA also removed certain nationality requirements for the exercise of professions such as lawyers, accountants, architects and engineers practising in Canada.

Both FTAs provide for advanced procedures for the temporary entry of professionals and their families, which facilitate the circulation of service-providers (independent professional and contract-service suppliers) across the territories of the FTAs.

Mutual recognition of qualifications

Domestic rules on regulated professions might raise obstacles to the circulation of professionals across borders. For instance, the requirement that lawyers have a degree from a local university prevents most foreigners from providing legal services. Agreements regarding the mutual recognition of professional qualifications can remove unnecessary trade obstacles. These agreements hinge on the recognition of foreign credentials as comparable to the domestic ones, and enable foreign professionals to practice in the receiving country.

FTAs can include mutual recognition agreements. CETA introduced a dedicated regime for the negotiation and conclusions of such agreements. Crucially, the associations of the regulated professions of each party manage the negotiations and submit their proposals to a joint bilateral committee. The associations can rely on a set of guidelines (Guidelines for Agreements on the Mutual Recognition of Professional Qualifications) which encourage, for instance, the consideration of alternative credentials (e.g., experience instead of formal qualification) in an overall assessment of equivalence. Residency within a jurisdiction or of having obtained local qualifications or experience cannot be indicated as conditional requirements for the granting of mutual recognition.

Provisions on foreign investments

The economic integration of two countries depends also on the flow of investments and capital between them. International agreements can support the circulation of foreign investments in two ways: by removing barriers to market access (how easily investments are let into the country), and by setting standards of protection for existing investments (how well investments are treated once they are in the country).

In the first case, liberalisation obligations might provide foreign investors with the right to establish themselves in the receiving country (pre-establishment guarantees). In the second case, protection obligations shelter already operating foreign investors from governmental wrongdoing (post-establishment guarantees).

CETA includes both sets of provisions. It prohibits quantitative limitations on the market access of foreign investments. For instance, the EU cannot impose a limit on the total number of foreign tourist agencies that can operate on its territory, and use it as a reason to deny access to a Canadian enterprise. Likewise, Canada could not impose a maximum percentage of shareholding held by EU subjects as a requirement for a local enterprise to operate on its territory. Along with market access commitments, CETA also bans performance requirements, subjecting foreign investors to specific conditions to enter the market and operate (for instance, to export a minimum percentage of its products, or to use locally sourced inputs in the manufacturing process).

CETA also includes a set of provisions granting substantive protection to already established investors. In essence, investors are protected against unfair and inequitable treatment, they are guaranteed compensation in the event of governmental expropriation and they are protected from discriminatory measures. Should a foreign investor believe that the host State has violated one of these standards of protection, it would be spared from bringing its claim to the domestic courts of that jurisdiction and could bring it instead before a special international tribunal established by CETA.

The investment chapter of CETA is not yet into force, pending ratification by all EU member states. There is no section on investment protection in the EU-Japan EPA, but the parties are working on a separate treaty on this matter.

Investor-State Dispute Settlement

Treaties containing provisions for the protection of foreign investments typically enable investors to sue the host government outside the domestic courts system. This possibility is granted to increase the perceived convenience of investing in the host country, pointing at the advantage of having a neutral forum adjudicating disputes between the foreign investor and the local government. This forum, in most existing treaties, is an international arbitral tribunal constituted specifically to resolve the claim and disbanded after the decision is rendered.

While this option is still employed in modern FTAs that contain a section on investment protection (see for instance the US-Korea FTA1), the EU has decided to abandon it, and create instead a permanent court, with a first-instance panel and an appeal body, for investor-State disputes. The EU has managed to introduce this approach in the CETA and the EU-Vietnam FTAs.

Government procurement

The EU, Canada and Japan are parties to the WTO agreement on Government Procurement (GPA). This agreement registers their commitment to treat foreign goods and suppliers as if they were domestic, when they carry out public procurement (the purchase of goods and services for the government). The precise scope of this commitment is specified, by each country, in a specific document: it varies between industry sectors and it might be the case that only certain levels of governments are bound (for instance, the federal government cannot discriminate but the provincial authorities can). The GPA has no hard and fast MFN rule, and it is therefore possible for its members to seek and offer better deals through bilateral agreements like FTAs.

For instance, the chapter on government procurement of the EU-Japan EPA has benefited EU goods and providers, by opening the public purchasing market of Japan in a number of ways. Japan has included under the EPA rules several governmental and independent agencies that were not bound by WTO rules (like the Pharmaceutical and Medical devices Agency and the Tokyo Metropolitan University). The EPA also opened to EU goods and services several sectors that had been until its conclusion outside the scope of WTO law (including telecommunications, insurance, advertising and marketing management).

With respect to CETA, the most valuable concession made to the EU is the binding of provincial and municipal governments and agencies that the GPA did not cover. This guarantee might not necessarily improve the treatment currently reserved to EU goods and services, but has the important effect of preventing the deterioration of Canada's rules, barring future discrimination. Increased access to, and trust in, the Canadian market, for instance, was estimated to result in a considerable increase in the UK's participation in the Canadian market. According to an impact assessment carried out by the Department on International Trade:

CETA enables greater opportunities for UK firms to compete for Canadian Government procurement projects worth between £65 to £80 million per annum.1

Intellectual property rights

Intellectual property rights (copyrights, trademarks, designs, patents, geographical indications) are protected in the WTO agreement on Trade-Related aspects of Intellectual Property rights (TRIPS). FTAs can contain additional TRIPS-plus obligations that strengthen the protection of IP rights and their owners in the jurisdiction of the FTA members.1 These could include, for instance, a longer period of protection for copyrights (from 50 to 70 years), or the provision of remuneration for artists when their music is played in bars and pubs.

CETA and the EU-Japan EPA complement the rules of the TRIPS, increasing certain standards of protection (for pharmaceutical patents, trademarks and unregistered designs) to align the regulatory frameworks of the two jurisdictions. They also provide for more incisive implementation processes for the enforcement of IP breaches, which can include civil enforcement rules and detention of counterfeit goods at the border.

Geographical Indications (GIs) of foods and drinks are protected under the TRIPS agreement of the WTO. This agreement offers equal treatment to foreign GIs and prohibits the use of GIs for products not originating from the designated area. However, it is for each country to select the GIs warranting protection. It is in the interest of each FTA member to include in the deal a list of GIs that it wishes the other party to protect in its domestic laws.

Critically, the CETA contains a detailed list of GIs of foods and drinks originating from the EU territory that Canada committed to protect (none from the UK). The EU-Japan EPA does the same (for instance, Annex 14B to the EU-Japan FTA includes Scotch Whisky and Scottish Farmed Salmon). Inclusion of GIs in FTAs ensures that these indications are automatically protected. For instance, it prohibits the use of GIs for products that do not fulfil the origin requirements, even when that name is accompanied by qualifiers (“in the syle of”; “type”).

Generic cheeses in Canada

Historically, European products have struggled to obtain protection for their GIs in the North American market. Certain terms, which correspond to protected GIs in Europe, have acquired the status of generic commercial terms in the US and Canada, and exclusive protection has been denied. In Canada, for instance, the names Asiago, Gorgonzola, Feta, Fontina, and Munster had been without protection before CETA.

With CETA, these GIs finally receive protection (that is, only products respecting the GIs specifics, in particular the origin from the indicated area, will be able to use that GI). This protection upgrade was possible by allowing products that use these names as generic indications to remain on the Canadian market (a process of so-called “grandfathering”). New products, instead, will not be able to use the generic names and must accompany them with expression such as “style” or “type” or “imitation.” This compromise was saluted as a remarkable achievement for GIs which had, until then, found it hard to leverage their special features in a market in which cheaper products could use their denominations.

Sustainable development, environment and labour rights

Recent FTAs can contain chapters on sustainable development. In these sections, the FTA parties address matters that do not relate directly to economic liberalisation. Rather, they exchange reassurances that the process of economic integration within the FTA, and the economic development that would follow, will be socially sustainable. Increased trade cannot come at the cost of a worse standard of living (see Chapter 22 of CETA; Chapter 14 of the EU-Japan EPA).

There is also an express provision reaffirming the parties’ right to pass general regulations to protect public interests, even when this might have an incidental effect on trade. The parties also pledged to use this regulatory autonomy properly. That is, they shall not use public interest acts to disguise protectionist policies. Moreover, they shall not relax environmental and labour standards to attract trade and investments.

FTA parties commit to observe the relevant international treaties regarding labour standards and environmental protection (for instance, the International Labour Organisation conventions on minimum age and equal remuneration; the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change). Sustainable development chapters also contain provisions that confirm the parties’ commitment to responsible forestry, sustainable fishing, the protection of endangered species and of biological diversity.

The parties also established an institutional structure for the monitoring of these commitments’ implementation. They set up a process of consultation and involvement of civil society, and envisage the possibility that disputes may arise between the parties relating to their observance of the sustainable development commitments. When such a dispute arises, a special panel of experts has the task to resolve it.

Corporate governance in EU and Japan

The EU-Japan EPA includes a section in which the parties commit to promote high standards of corporate governance. For instance, they recognise the importance of accountability of directors towards the shareholders, the shareholders' rights to participate and vote in general meetings and oversee the company's decisions. EU and Japan also committed to ensure that takeovers of publicly listed companies occur at transparent prices under fair conditions.

This section seeks to bridge the gap between the corporate cultures of the two parties. In particular, certain embedded aspects of the Japanese practice (widespread cross-shareholdings, loyalty-based decisions, relative unaccountability of boards) were seen as a possible obstacle to efficiency and discouraged foreign investors. Reform of corporate governance in Japan and alignment with global standards will arguably increase transparency and attract foreign shareholders and capitals.

Conclusion

The UK will likely start negotiating trade agreements as soon as it exits the EU. The negotiations with the major economies will probably concern the entire range of topics that free trade agreements can cover. The coverage of a treaty requires specific negotiation expertise and determines, in turn, the goals and the compromises that a party seeks to pursue.

At the national level, identifying the elements of a treaty allows the central government to carry out an assessment of the estimated impact of a deal. In light of the treaty's content, the UK government has committed to hold meaningful consultations with the interested stakeholders, including the national and local legislatures, the devolved administrations and the industry.1

FTAs take years to negotiate, and commonly negotiators look back at previous deals to draw inspiration for the text of new treaties. Recent FTAs like the CETA and the EU-Japan agreements are bound to influence the drafting decisions of negotiators in future deals. An informed choice can be made to retain or discard these models; either way, a close understanding is necessary.

This briefing explained the sectoral coverage of these two FTAs, whose provisions go beyond the mere removal of tariffs and the establishment of concessions regarding trade in services. It is fair to expect that post-Brexit deals will look quite similar to these treaties, and it is in the UK's interest to build the capacity to negotiate and achieve similar deals as soon as practicable.

Appendix A: Glossary of Brexit-related trade jargon

This Glossary lists technical terms and phrases that might be unfamiliar to the public. They recur in the discussion about Brexit and its implications for international trade. The Glossary provides a short explanation of these concepts, with examples of their use in Brexit-related discussions.

Canada model

Canada and the EU have agreed on a FTA called CETA (Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement). Under CETA, most trade and services can be traded between the EU and Canada freely. Should the UK want to go down a similar path, it could propose a similar FTA to the EU, relating only to goods and services. Tariffs would be avoided, but custom checks would be unavoidable, because goods would still be subject to the regulations of the importing country.

This scenario would be more palatable to the EU than UK’s attempt to retain only the advantages of free trade in goods and agriculture and avoid further responsibilities of participation in the single market. It is still unclear how the Canada (or Canada-plus) model would address the situation at the border between Ireland and Northern Ireland.

Usage in Brexit talks: “Michel Barnier, EU chief negotiator, will next month formally offer Britain a looser free trade agreement— sometimes described as “Canada plus” — which would scrap tariffs but still leave non-tariff barriers in place.”1

“Mrs May should look at the option of retaining the closest possible links with the EU for the first two years after its exit in March, modelled on Norway's relationship with Brussels. This, he argued, would honour the referendum commitment to leave key institutions, like the Common Agricultural and Fisheries policies, but minimise disruption to business while the UK negotiated a much looser arrangement based on Canada's free trade deal with the EU.”2

Concessions

Countries could protect their economy from foreign competition, for instance prohibiting all imports. Free trade, therefore, relies on the relevant countries’ concession to open their borders and their markets to foreign trade. Trade concessions can be unilateral or codified in international treaties, and they form the specific currency in trade negotiations (for instance, to lower the tariff on imported cars from 30% to 10% is a trade concession). Each party of a trade agreement seeks to obtain the largest concessions from its partners, to secure the widest access for its goods and services on their markets. Conversely, it will have to make sufficient trade concessions, opening its economy to foreign goods and services.

Usage in Brexit talks: “Japan is seeking tougher concessions from Britain in trade talks than it secured from the EU, while negotiations between London and Tokyo are also being slowed by the looming risk of no-deal Brexit.”1

“A Chilean official said that Santiago was “in principle in favor of preserving the commercial flows” with Britain during transition but demanded concessions in the agricultural sector, which would apply to a future U.K. accord with the South American country.”2

Customs union

When countries conclude a free trade agreement (see below), they sometimes decide to harmonise their external trade policy, that is, the way they regulate trade with third countries. The European Union is a customs union, hence it will charge the same tariff on goods from third countries, irrespective of whether they are imported, for instance, into Germany or France. Moreover, the EU act on behalf of all EU members when negotiating FTAs with other countries.

Upon ceasing to be a member of the EU, the UK will also leave the customs union. It will be able to determine its external trade policy, for instance setting autonomously tariff rates applicable to imported goods, or negotiating trade deals with third countries. Customs unions normally imply a free trade area (see below) but it is possible to have free trade areas without a customs union. For instance, NAFTA (the free trade area between USA, Canada and Mexico) instituted a free trade area – there are no trade barriers between the three states – but did not form a customs union – the three countries do not have a common external trade policy.

Usage in Brexit talks: “Mrs May said leaving the customs union would allow the UK to strike new trade deals around the world, adding that she was seeking a “frictionless” border with the EU.”1

“[T]he prime minister has always said that the UK could not accept staying in the customs union. But there are signs that the UK is considering whether to stay in an almost-identical arrangement for good, if a wider trade deal can't be done.”2

European Economic Area (EEA)

The EEA is the association between the EU countries and three countries of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA): Iceland, Norway, and Lichtenstein. Switzerland is a member of the EFTA but has not acceded the EEA.

These EFTA countries participate in a free trade association with the EU which covers all four freedoms (goods, services, capital, workers) and largely corresponds to the EU single market (see below), with the exception of agriculture and fisheries, which are not within the scope of the EEA. EFTA territories and the EU do not form a single customs union. Non-EU countries participating in the EU must implement most EU laws and contribute to the EU budget, although slightly less than what EU members pay. Roughly, Norway pays into EU programmes around 20% less than UK does into the EU main budget, per person.

Since EEA non-EU members are not represented in the European Commission and the legislative bodies of the EU, their impact on EU legislation is modest. Their situation is often described as rule-taking without rule-making. In the wake of Brexit, the UK would leave the EU, but it has expressed interest in continuing trade within the EU single market. Therefore, UK’s membership to the EEA has been explored as a possible way forward.

Usage in Brexit talks: “Norway’s government had previously hinted it might block British membership of the EEA because such a change would likely shift the balance of power within the trade association against Norwegian interests. But in an interview with the Financial Times newspaper Erna Solberg suggested EEA membership was now an option for Brexit Britain.”1

“Doubtless these EEA scenarios will strike some readers of Brexit Briefing as unrealistic. After all, a minority of Conservative politicians, more influential than their small number suggests, purport to regard any proposal for close post-Brexit ties between the UK and EU as close to treasonous.”2

Four freedoms

The EU single market (see below) is built on the free circulation of goods, people, services and capitals. All barriers that could hinder their circulation across the EU are removed, such as tariffs on goods and visa schemes for EU workers. The four freedoms form a package that cannot be taken apart. Even non-EU members that participate in the single market (thus forming the EEA, see above) respect the four freedoms.

The UK would prefer to maintain its commitments to the freedom of circulation of goods and capitals after Brexit. This scenario would permit UK and EU goods to circulate in the two markets without tariffs and border delays.

Freedom of movement of people and some sectors of trade in services are a delicate matter for Brexit negotiators. Whilst the EU consider them integral to the single market, the UK would like to retain absolute autonomy in immigration matters. Under the principle of freedom of movement, EU citizens who work or study can travel to, and reside freely in, any EU country. Job-seekers can also travel and remain in any EU country for a short period.

Usage in Brexit talks: “Britain would face labour shortages in London and the south-east from a no-deal Brexit, according to a report calling for the government to extend freedom of movement for EU migrants to protect the wider economy.”1

“UK negotiators would like to put the proposal forward to coincide with a European Council summit in June, in a bid to break a deadlock in Brexit talks. The plan would see a high level of access to the UK for EU citizens in the future, but would leave the British government power to halt it in certain circumstances. But it is likely to enrage hardliners who would see anything even mildly like free movement as a betrayal of the 2016 referendum result.”2

“[t]he EU has spelled out its reasoning in full – arguing that it cannot delegate customs checks to a non-member state, that it thinks Ms May’s proposals for splitting up the single market would give Britain an unfair competitive advantage, and that it wants to preserve the integrity of the bloc’s “four freedoms”.”3

Free trade agreements (FTAs)

Two or more countries can agree to drop all trade barriers among them, allowing goods to circulate freely across their territories. If this agreement does not also create a customs union (see above), each participating country will continue to apply its own trade regulations, including tariff rates, to goods coming from third countries.

FTAs thus create a preferential treatment that only applies to goods coming from within the FTA, and discriminate against third countries. The single market of the European Union (a very advanced form of FTA), can illustrate the point: UK goods now enter Germany duty-free, whereas US goods can incur tariffs at the German border. UK goods are thus treated more favourably than US goods. This discrimination contradicts the MFN rule (see below), but the World Trade Organization (see below) tolerates FTAs that effectively liberalise most of the trade among its members.

Discussion of FTAs in relation of Brexit concerns three central aspects. First, by leaving the European Union the UK would leave the single market, that is, the free trade area of the EU. Second, after Brexit the UK would be able to stipulate new FTAs with third countries. Third, after Brexit the UK might cease to benefit from the existing FTAs between the EU and third countries.

Usage in Brexit talks: “[a report] compares the length of the transition period (21 months) with the time taken to negotiate and fully implement recent free trade agreements. The EU-Canada free trade deal that we hear so much about has taken more than seven years so far. The EU-South Korea deal took nine years.”1

“A radical blueprint for a free trade deal between the UK and the US that would see the NHS opened to foreign competition, a bonfire of consumer and environmental regulations and freedom of movement between the two countries for workers, is to be launched by prominent Brexiters.”2

“Existing agreements that deliver 12 per cent of the UK’s total trade will be lost if there is a no-deal Brexit, the government has admitted. Trade agreements enjoyed with scores of other countries, through EU membership, will “cease to apply” if the UK crashes out of the EU next March. The government said it would attempt to replicate the deals “as soon as possible thereafter” – but admitted those “third countries” would have leverage to demand better terms.”3

Most-favoured nation

The World Trade Organisation requires all its members to treat goods without discrimination, irrespective of their country of origin. This requirement is embedded in the “Most-Favoured Nation” principle, stipulating that every country must be treated as the “most-favoured” one – that is, an importing country cannot treat goods from country A less favourably than goods from country B. Preferential or punitive tariffs, applicable only to goods from one country are prohibited, in principle.

When it comes to custom duties, this principle requires that the same tariff apply to goods from all countries. Free Trade Agreements (see above) constitute an exception to the principle: goods circulate freely within the area of a FTA. In a no-deal scenario, if the UK leaves the EU single market, the EU will still need to extend MFN treatment to UK goods, and the UK will do the same for EU goods.

Usage in Brexit talks: “The UK would pay tariffs on goods and services it exported into the EU, but since the UK would pay ‘most favoured nation’ rates, that would prohibit either side imposing punitive duties and sparking a trade war.”1

“The government is desperate to ensure that Britain’s big exporters do not suffer from Brexit. It has explicitly assured Nissan, a carmaker, that it will not suffer. But WTO rules can make such sectoral deals hard. If Britain were to agree bilaterally with the EU not to apply tariffs on cars, the WTO’s “most-favoured nation” principle might force it to offer tariff-free access to other countries as well.”2

Mutual recognition

In the EU single market (see below), the principle of mutual recognition operates to render the circulation of goods and services smoother. Goods that are lawfully sold in one EU country can be sold across the single market even if they do not conform to the technical regulations (think health, safety and consumer protection) of all other states.

In other words, EU countries have committed to recognise each other’s rules as satisfactory, when there is no EU law that applies across the board. As a result, goods from EU countries are presumed to be safe, or not harmful to human health or consumer protection. In financial services, a similar arrangement is called ‘passporting’: companies authorised in one EU country can operate anywhere in the EU.

Goods from third countries do not enjoy this presumption, and must comply with the EU standards. Free circulation is thus hindered by two regulatory barriers: the goods must effectively comply with EU rules (and those which do not have no access to the EU market), and compliance must be assessed through a process that entails cost and delays.

The UK has proposed that it will submit to the EU its regulations for scrutiny, to demonstrate their substantial equivalence to the EU rules, and spare UK goods from compliance checks. This proposal is often labelled as “Common Rule Book,” referring to the commonality of purposes of UK and EU standards, which should convince the EU to waive its right to perform border checks.

Mutual recognition currently operates, in a less automatic way, for services and service providers. After Brexit, the qualifications of professionals like doctors, professors and architects might no longer be recognised between the UK and EU member states.

Usage in Brexit talks: “The [Office for Budget Responsibility] said if there was no agreement on standards everything would have to be resubmitted for approval: "In a scenario where the UK and EU are unable to agree to the continued mutual recognition ('grandfathering') of existing product standards and professional qualifications, all existing goods may need to be re-approved before sale and services trade would be severely restricted by the loss of market access."”1

“Equivalence does offer certain advantages, in that it does not require both sides to mirror each other’s rules and legislation. Businesses from one jurisdiction can offer financial services in another on the grounds that their standards are similar enough that customers will be protected. So the UK could in theory retain access to the EU market, without having to accept EU jurisdiction or copy out its laws.”2

Norway model

Norway is not a member of the European Union. It participates in the EU single market (see below), but it does not participate in the EU customs union (see above). Reference to the Norway model is shorthand for the situation of those EFTA countries (see above) who acceded the EU market and thus form the EEA (see above). Iceland and Lichtenstein are in the same position.

The Norway-model is sometimes indicated as a viable solution to reconcile the exit from the EU with the membership in the EU single market – except agriculture and fisheries. It must be noted that EEA countries, including Norway, subscribe to all four freedoms (see above), including the freedom of circulation of workers, students and job-seekers across their territories. It is unclear whether the UK intends to retain the obligations relating to the free circulation of people, which significantly curb its autonomy in immigration matters.

Since Norway has little input on EU laws but must respect most of them to maintain access to the EU market, its situation is often described as ‘rule-taking.’ It is unclear whether the UK, after Brexit, would accept to implement EU laws without being able to participate in their creation, and to respect the decisions of the EU Court of Justice. Because of these difficulties with the Norway-model, it has been criticised by those advocating a more radical detachment from the EU after Brexit.

Usage in Brexit talks: “Leaving the EU, but remaining in the European Economic Area (EEA) along with Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein, would cushion the impact of Brexit by keeping the EU in the single market. The UK’s economic power might allow it to win a concession on free movement. Alternatively, it could use provisions to curb migration that already exist.”1

“Scotland’s first minister urged MPs to reject any “cobbled-together agreement” and called for a Norway-style deal with Brussels, as the only “democratic compromise” that would unite different factions.”2

Public procurement

Governments and state-owned bodies purchase goods and services. Public purchasing is funded through taxpayers’ money and, therefore, public rules apply to ensure its efficiency and transparency. These rules set the requirements that suppliers of goods or services must satisfy to compete for public contracts. For businesses, access to public tenders is very valuable: the government is often the largest purchaser of goods and services in a country’s marketplace. Public procurement is a big share of the global economy, and typically accounts for 12-15% of a country’s GDP – around 14% in the UK. Understandably, suppliers are also attracted by procurement opportunities abroad. Therefore, whether foreigners can compete for governmental contracts, and at which conditions, are crucial questions affecting international trade in goods and services. In the EU, all contractors from a Member State must be treated equally. An agreement within the WTO – the Government Procurement Agreement – sets out concessions that only operate among its 47 members.

Usage in Brexit talks: “…trade discussions include the alignment of single-market rules for goods, such as safety and environmental regulations, to avoid further paperwork at the border. An independent British trade policy would then apply mainly to services, data, public procurement and other intangible items.”1

“Staying in the [Government Procurement Agreement] is important so that British companies can bid for government work in the United States, the European Union and Japan, and their firms can retain access to Britain’s procurement market."2

Rules of origin (RoO)

These are rules that determine the country of origin of a good, a determination that might be difficult when goods travel across countries and contain components (“inputs”) of various provenance (for instance, a German car with a Korean engine and leather seats made in Italy). RoO normally require a minimum percentage of a good’s inputs to come from a certain country, for that good to claim that origin.

In the context of Free Trade Agreements (see above), only goods originating from within the participating countries circulate freely. Goods from third countries, instead, might incur custom duties. Therefore, custom authorities need to verify the provenance of goods, to identify the applicable treatment. In a hypothetical UK-EU free trade agreement, hence, RoO would determine whether a good can be considered as originating from the UK, and thus enjoy free access to the EU market (or the other way round).

Brexit will entail that the UK input into the manufacturing of EU goods will no longer count as EU input. When the EU origin of the good is important to enjoy trade benefits (for instance, to obtain duty-free access into Japan, under the EU-Japan FTA), this change might incentivise manufacturers to replace the UK-based component with EU-based ones.

Usage in Brexit talks: “Products like rice, which are only processed in the UK rather than grown here, will fall foul of exceptionally complex “rules of origin”. These govern the degree to which a foodstuff can have an input from outside the EU before it incurs a higher cost.”1

“Businesses that export to the EU will require a suite of changes in their operations, including knowledge of tariffs, rules of origin definitions and the demands of filling in 54 boxes of information for customs declarations forms required for each consignment.”2

Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) and technical measures

States adopt rules to protect humans, animals, and plants from diseases, pests, or contaminants. For instance, they might outlaw the use of certain pesticides or prescribe that meat from animals slaughtered under the age of seven days is unfit for human consumption. Technical measures regard the characteristics of goods on the market, for instance the technical requirements for household appliances to be safe, or the obligation for cars to be equipped with safety belts. SPS and technical measures can constitute an obstacle to trade: if the regulations of the country of origin differ from those of the country of importation, the goods cannot be sold there unless they also comply with the latter. Compliance with multiple sets of regulatory standards is a cost that discourages international trade. The inclusion of rules on SPS and technical measures in trade agreements seek to reduce these regulatory costs, by promoting alignment between the standards of the trading partners, and/or by encouraging them to recognise the equivalence of each other’s standards. In the WTO, the SPS agreement and the agreement on technical barriers to trade (TBT) regulate these matters. In the EU, all member states observe SPS and technical rules dictated by EU law, or recognise each other’s standards as sufficient for marketing goods across all the single market.

Usage in Brexit talks: “The move to keep in step with EU sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) rules will mean that the movement of animals across the island of Ireland will not have to be restricted on the Border or subject to special veterinary checks for nine months from the UK departure.”1

“European Union rules currently limit US exports of certain food products, including chlorine-washed chicken and hormone-boosted beef. If free of EU trade rules, the US want the UK to remove such so-called “sanitary and physiosanitary [sic]” standards on imported goods. A Downing Street spokeswoman said: "We have always been very clear that we will not lower our food standards as part of a future trading agreement.”2

“The government is being urged to prevent consumer safety standards from slipping after Brexit, to avoid putting lives at risk from the growing number of potentially dangerous counterfeit electrical goods coming into the UK.”3

Single market (or internal market)

The European Union constitutes a single market, an area in which obstacles to the circulation of goods, services, capitals and workers were removed (the four freedoms). Tariffs and other regulatory barriers do not apply within the single market. The EU single market comprises all EU member states and is open to the four members of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA): Iceland, Lichtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. EU member states and Norway, Iceland and Lichtenstein form, together, the European Economic Area (EEA, see above).

One country’s membership to the EU grants access to the single market, therefore Brexit is likely to affect or terminate UK’s participation therein. To a relevant extent, the efforts of the UK and EU to reach a deal on the regulation of the future relationship concern precisely the possibility for the UK to remain, in some capacity, within the single market. For this reason, suggestions are often made that the UK should follow the model of EEA non-EU countries, which managed to enter the single market without entering the EU. These countries accepted the single market package deal (the four freedoms), as well as the observance of common rules and the jurisdiction of the Court of Justice of the EU to clarify those rules.

To participate in the single market, a country is required to abide by the four freedoms. The UK has proposed, through the so-called Chequers plan, to retain free trade relationship with the EU, but limitedly to trade in goods and agriculture, and the common rules governing it. The EU has not endorsed the proposal, noting that all four freedoms (including freedom of movement of workers and services) must be accepted at once. If the Chequers plan were approved, abidance to the common rules on trade in goods would prevent the UK from entering FTAs (see above) with third countries based on a relaxation of those rules.

Usage in Brexit talks: “The SNP has long argued for Britain to retain its membership of the single market and the customs union after leaving the EU, an approach the prime minister has rejected repeatedly.”1

“Trade deals are often as much about standards as tariffs. By keeping to EU goods regulations, Britain might make it make it much harder for itself to strike agreements with other countries. The US, for example, wants the UK to break away from the EU’s prohibition on chlorinated-treated chicken as part of any trade deal with Washington.”2

Trade remedies (anti-dumping and anti-subsidy)