Key Issues for Session 6: COVID, Climate and Constitution

This briefing has been produced by the Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe), which is the Parliament’s impartial research service. It identifies some of the key issues that MSPs may face in the Parliament’s sixth Session. It is intended to assist MSPs and their staff, who are encouraged to contact SPICe if they require further information on these or any other topics.

Foreword from the Clerk/Chief Executive

Welcome to the Scottish Parliament Information Centre’s Key Issues for Session 6 briefing – COVID, Climate and Constitution.

The Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe) is the Parliament’s internal research centre. Its subject specialist researchers and information specialists provide impartial, factual, accurate and timely information and analysis to support MSPs in undertaking parliamentary business. This includes support to enable MSPs to respond to constituency enquiries, scrutinise legislation and support the work of the Parliament’s committees.

The Key Issues for Session 6 briefing illustrates the kind of briefing SPICe produces for parliamentarians. It outlines some of the key subjects likely to be of particular interest in the coming Parliamentary Session, providing tailored, expert, impartial analysis of the issues that matter to MSPs and the Parliament.

Whilst the Parliament will undoubtedly engage with a broad range of issues during the next five years, SPICe has identified three broad themes which are likely to feature heavily in the work of MSPs during Session 6.

These themes are:

COVID-19 - The road to recovery.

The climate and ecological emergency and green recovery.

The devolution settlement post EU exit and UK relations.

Alongside these three themes, SPICe has highlighted another 26 issues for Session 6, covering all major areas of devolved policy, from mental health provision to the business base in Scotland, and from changes to family law through to changing car use. You can read the briefing from cover to cover, or you can easily dip into the issues that interest you most. I hope it proves to be a thought provoking and useful reference tool for the months and years ahead.

SPICe is here to support the work of MSPs. If you have any questions about how SPICe can help you in your duties please contact SPICe Team Leaders – their contact details and much more can be found in the SPICe service guide, accessible on the Parliament's intranet.

David McGill, Chief Executive

COVID-19 – The Road to Recovery

Kathleen Robson, Senior Researcher, Health and Social Care

Now that the COVID vaccine roll-out is firmly underway, the political focus in Session 6 will shift to the post-pandemic recovery. As the dust begins to settle, it is perhaps time to take stock and assess where the recovery may need to be focused.

Throughout the pandemic, both the Scottish and UK governments have talked about the four COVID harms:

COVID health harms

non-COVID health harms

societal harms

economic harms.

This serves as a useful model to assess the toll the virus has taken and examine the route to recovery.

It has not all been bad news, some areas such as crime and carbon emissions have improved over lockdown. However, the following details some of the key areas of harm that the recovery may need to mitigate against.

COVID-19 health harms

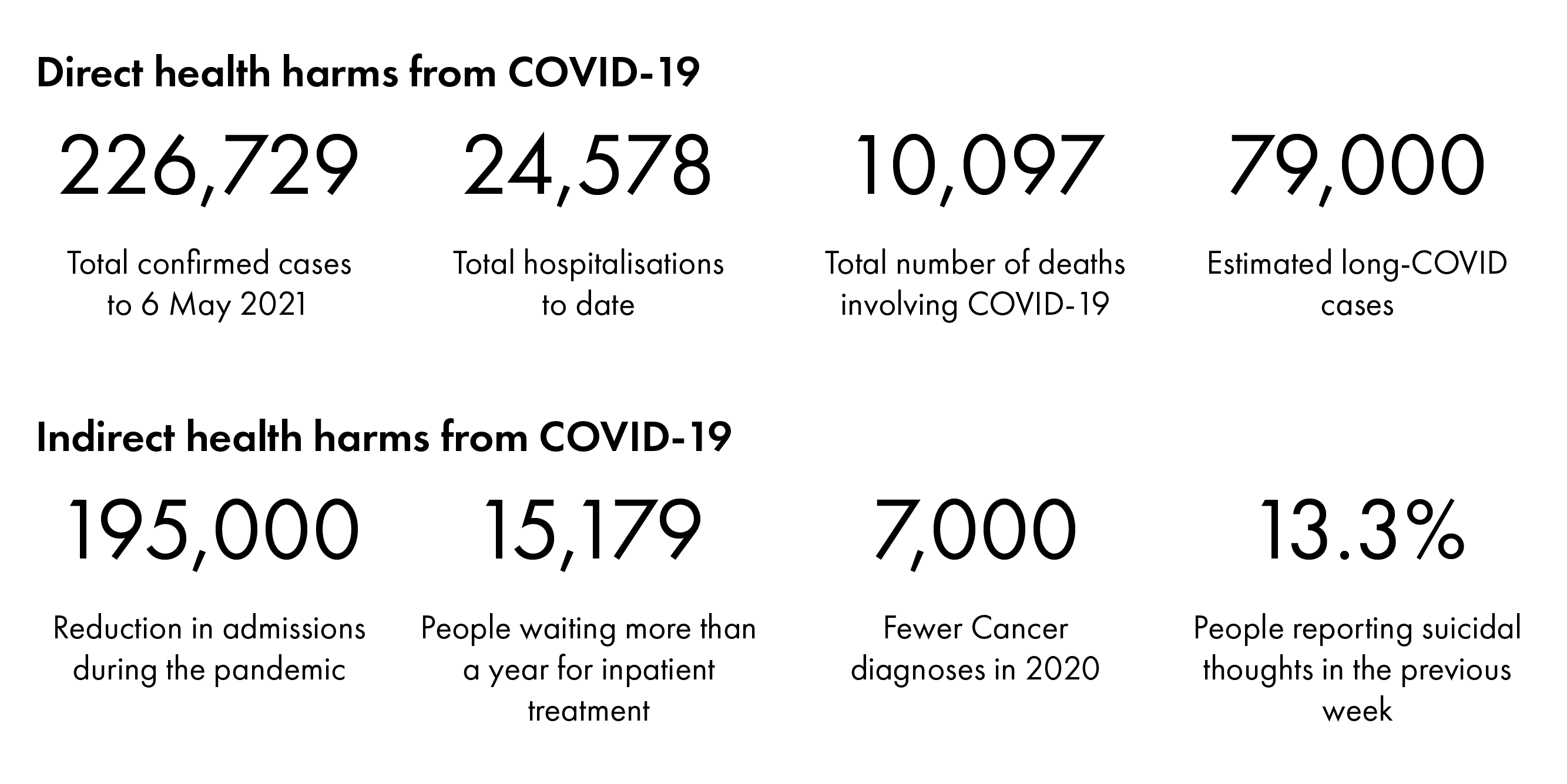

For the last year we have had daily updates on the level of harm inflicted by COVID-19 in Scotland. The grim totals (at time of writing) include 226,729 cases, 24,578 hospital admissions and 10,097 deaths involving COVID-19, including at least 3,400 in care homes.

There is also the unknown quantity of ‘long-COVID’, that is, those with long term health consequences after infection. It is estimated that around one in five people exhibit symptoms for five weeks or longer and around one in ten exhibit symptoms for 12 weeks or more. A recent ONS study tried to measure the overall prevalence of long-COVID and found 79,000 people in Scotland reporting symptoms.

This level of prevalence could have ongoing implications, not only for the individual, but also for the economy, in terms of productivity, and a potential increase in social security claimants.

It may also require a response from the health service, but treatment options are limited and people have mainly been treated by existing services such as general practice. NHS England is creating a network of long-COVID clinics but we have yet to see if Scotland will follow suit.

Non-COVID health harms

As the NHS responded to the unfolding pandemic, there was a scaling back of ‘normal business’. Screening programmes were suspended, emergency admissions fell to 60% of normal levels, and all admissions were down by 195,000 over the year. This has resulted in a backlog of known health need, with the numbers waiting for treatment and the length of wait increasing. By the end of 2020, more than 15,000 people had been waiting longer than a year for inpatient treatment.

Perhaps more worrying, is the scale of the unknown health impact created by the pandemic in the longer term.

This not only arises from delays in seeking and receiving treatment, but also from an increase in unhealthy lifestyle behaviours like reduced physical activity and unhealthy eating, the harms of which may not be felt for years to come.

More pressingly however, are the outcomes for those with existing disease where the diagnosis has been delayed by the pandemic. For example, there were 7000 fewer cancer diagnoses made in 2020 compared to the previous year. Given the importance of detecting cancer early, this may have a detrimental impact on future cancer survival.

Then there is the impact on the nation’s mental health.

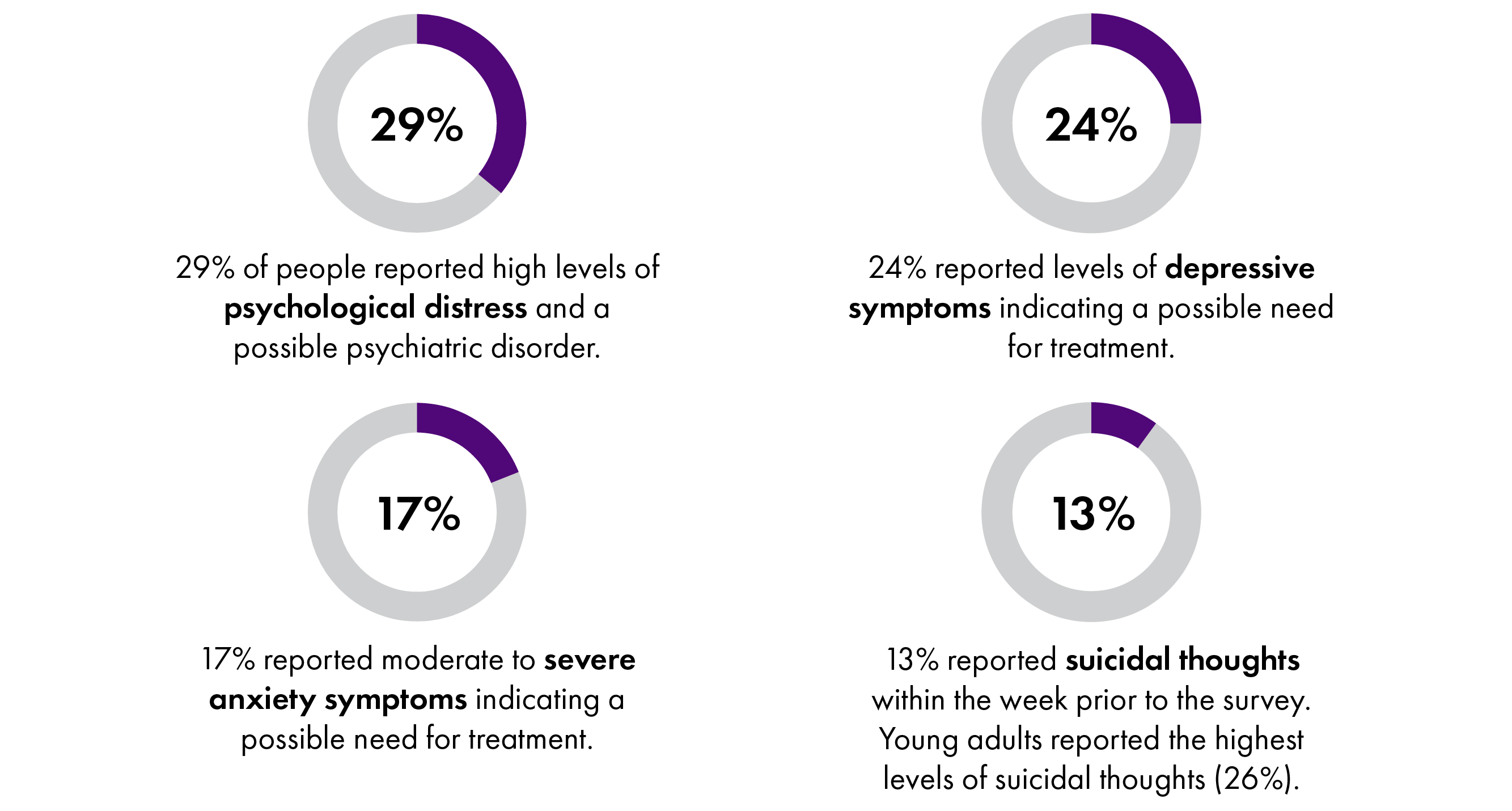

The Scottish mental health tracker has shown almost a quarter (24.1%) of respondents had depressive symptoms at levels that may warrant treatment, with 13.3% reporting suicidal thoughts in the previous week. It is too early to know whether this has filtered through to deaths by suicide in 2020. For more on mental health and COVID, see our dedicated chapter.

The ongoing impact on mental health is likely to bear a direct relation to what is often called ‘the social determinants of health’. This is where the wider societal and economic impacts come in.

Societal harms

It is difficult to know where to start in measuring the impact on society, as no corner of our lives has gone untouched. Some of the indicators used by the Scottish Government include school openings, crisis grants, loneliness, and perceived job security, but arguably this barely scratches the surface.

What we do know about the societal harms is that many have affected younger people disproportionately. This is in contrast to the direct health harms which have tended to fall on the older generations.

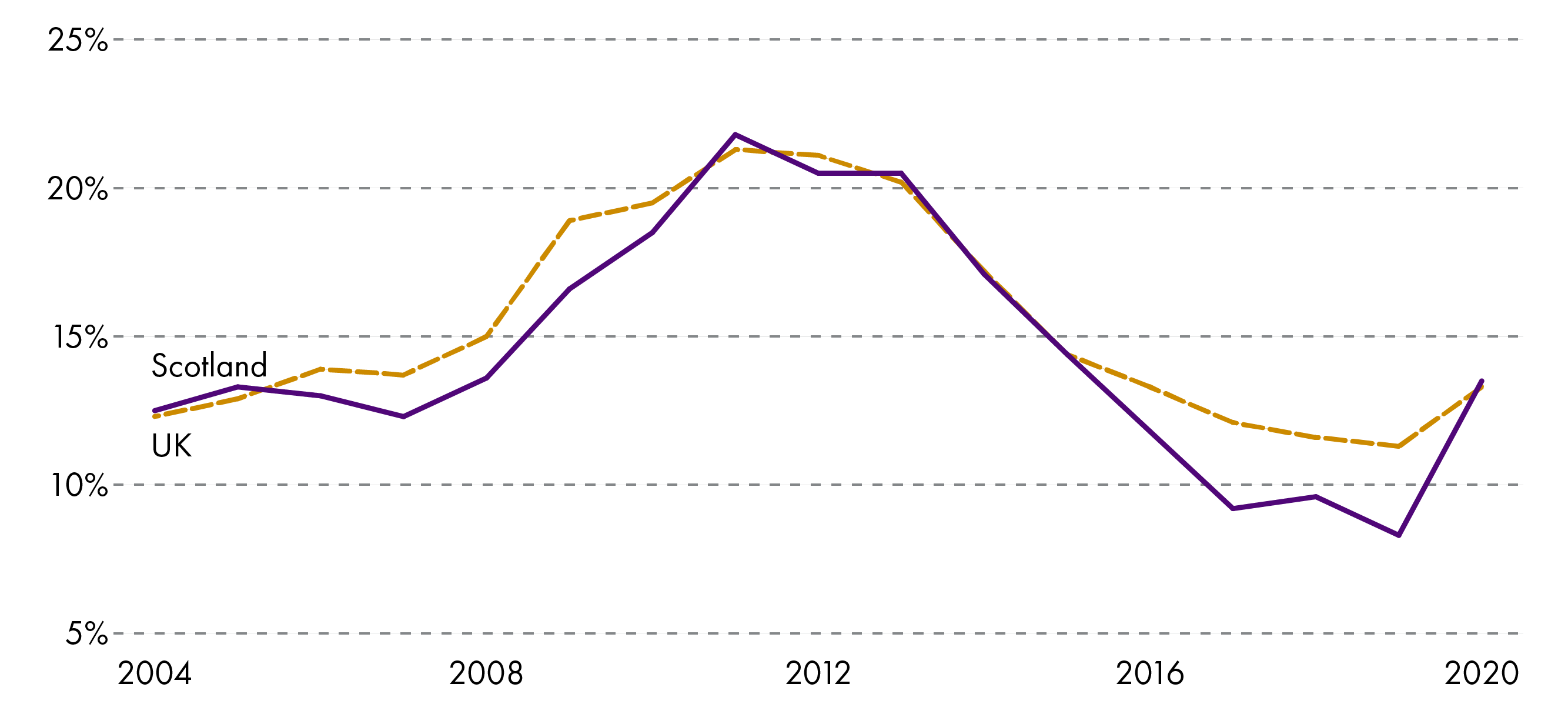

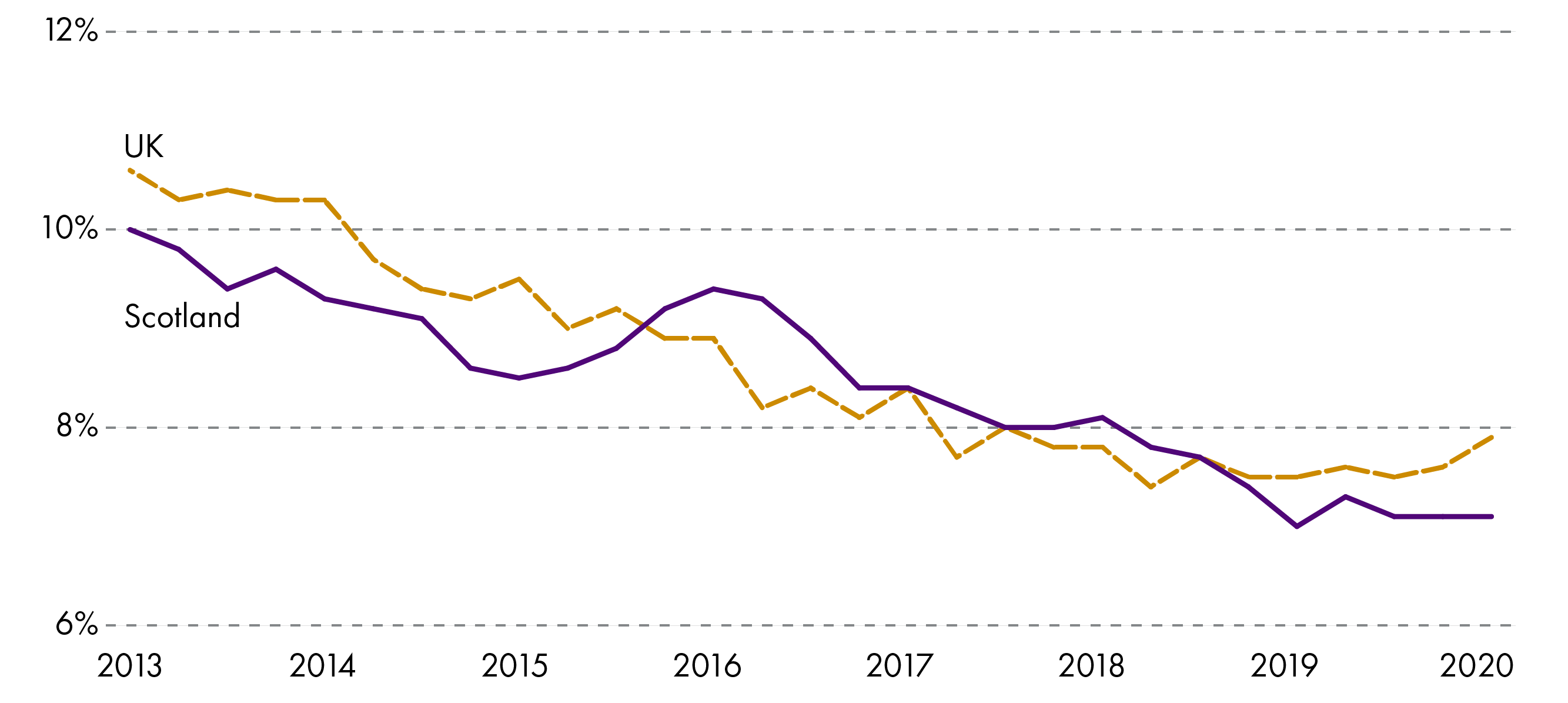

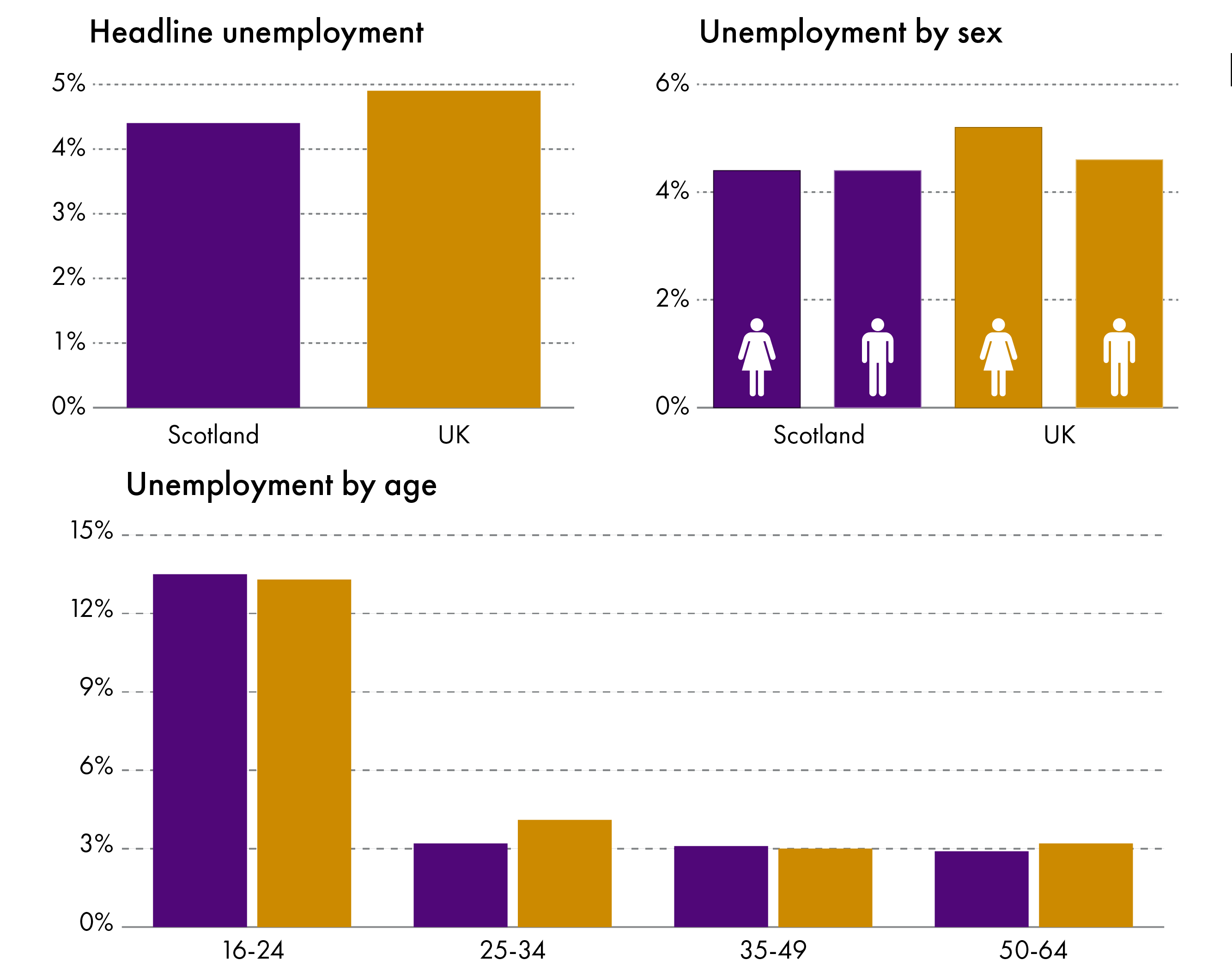

The harms falling on the younger generations include disruption to education and learning, a greater fall in employment and a higher number on furlough.

The number of people under 25 claiming universal credit rose significantly and the number of graduate jobs advertised for university leavers fell by as much as 60%.

Many of these impacts have also been experienced more by women, minority ethnic groups, people with disabilities and those on low incomes. The Scottish Government and COSLA’s ‘COVID-19 Wellbeing Report’ recognised that the pandemic has both highlighted and exacerbated existing inequalities. See our chapter on the labour market and the pandemic for more information.

Economic harms

The economic impact comes from both the public health restrictions and the fiscal support measures put in place to mitigate against them.

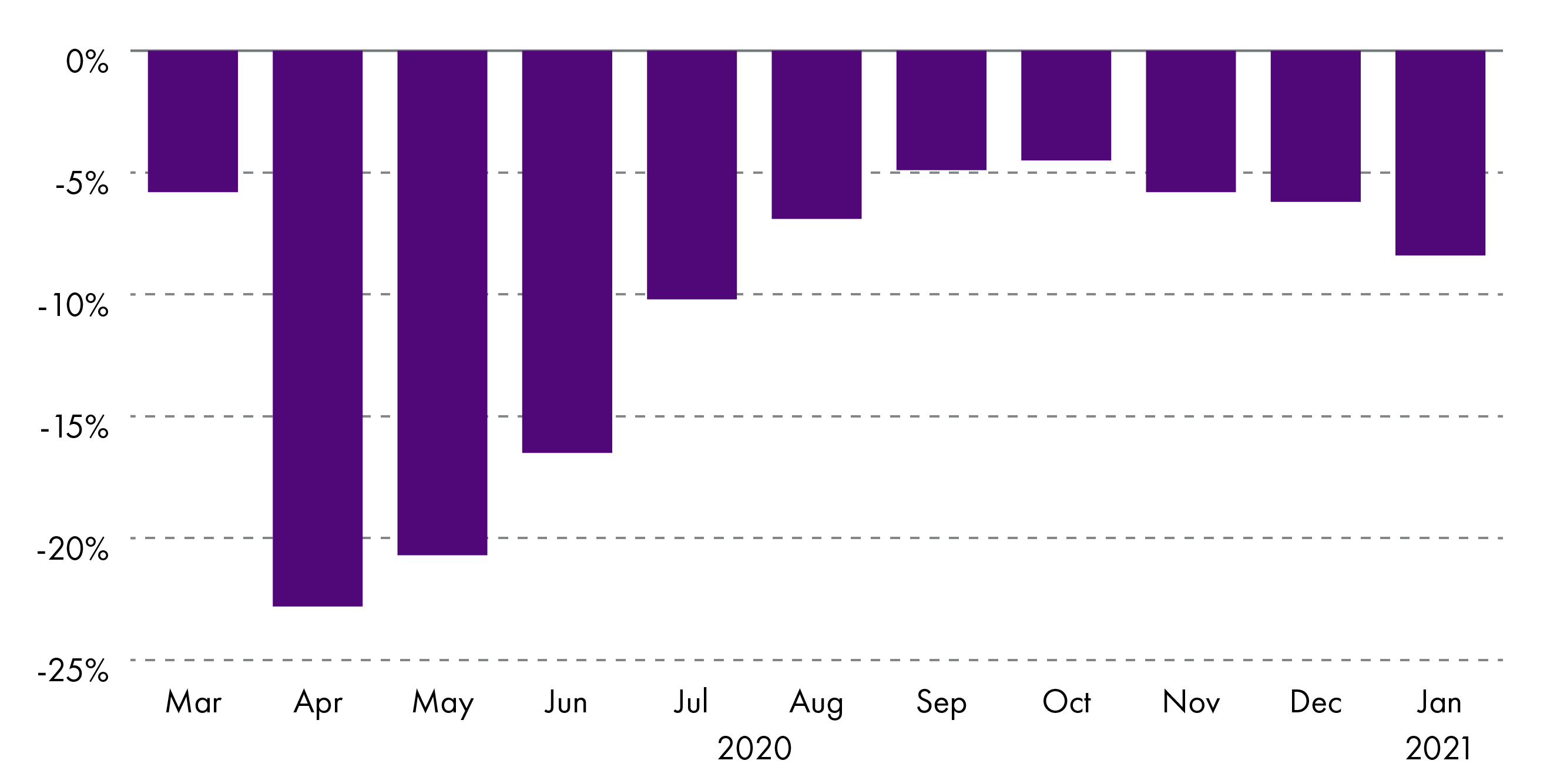

At its starkest, the economic impact can be seen in the dramatic fall in GDP across the UK in 2020, with the economy not likely to return to pre-pandemic levels for some time.

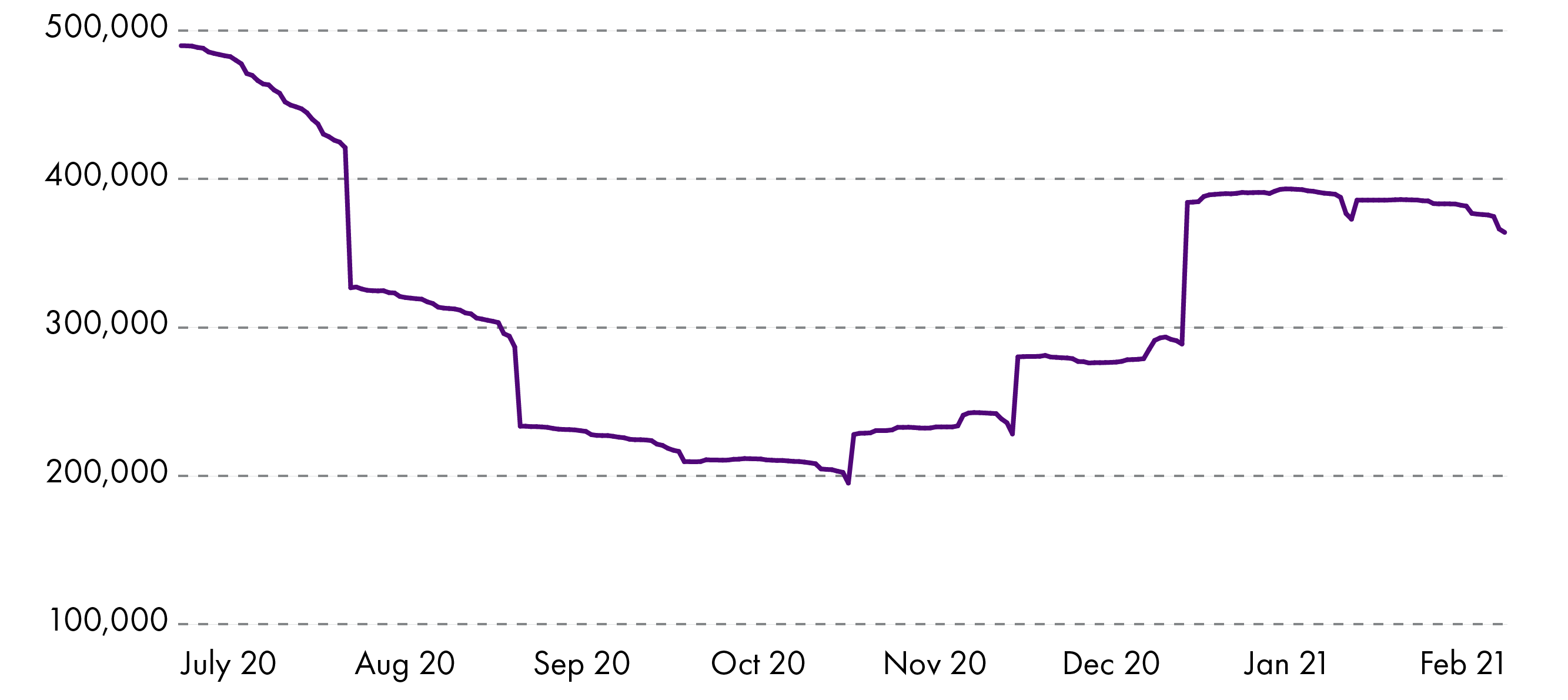

At its low point, the Scottish economy took a near 25% hit to economic activity compared to pre-pandemic levels and 736,000 workers were furloughed. And while the economic figures have recovered somewhat, not all parts of the economy have been impacted equally. Those parts of the economy that depend on social interaction - such as tourism, the night-time economy, arts and culture – have yet to see any sort of notable recovery. For more on the impact on the business base in Scotland, see this chapter.

The impact of the pandemic will be felt on and shape our economy for years to come, touching on issues such as: new business models; changed consumer behaviours, accelerated digitalisation, increased debt levels, youth unemployment, missed human capital and educational opportunities, altered international travel flows, and how we use our urban areas – to name but a few.

Fiscal interventions to mitigate the economic effects of the crisis have also been seen throughout the world, and the UK has been no different.

In 2020-21, £9.7 billion was added in Barnett consequentials to the Scottish spending envelope for COVID mitigation measures. Significant additional COVID resources (£2.3 billion) have also been allocated for the current financial year. £1.1 billion has been carried forward from 2020-21 and a further £1.2 billion allocation has been made. It is possible this might be supplemented depending on how the situation evolves.

The UK Chancellor has indicated that the current extremely high levels of borrowing and debt are manageable in the short term due to extremely low interest rates. However, there will inevitably come a time when the debt requires to be paid down via tax increases, spending cuts, or a combination of the two.

The fragility of the recovery

If the pandemic has taught us one thing, it is that we live in a small and interdependent world. Countries can close their borders and batten down the hatches, but this cannot entirely mitigate against the global impact of the virus.

The vaccine has brought much cause for optimism and the recovery is likely to feature heavily in Session 6. However, the sustainability of any recovery will also depend on access to the vaccine globally.

The UK vaccine effort has been widely praised but until this is matched in the rest of the world, any recovery will be at risk from variants. This will require cooperation between the UK nations and beyond.

Session 6 will be challenging for newly elected Members as they tackle the scale of the recovery needed. But it will also be a fine balancing act to promote recovery while also keeping potential waves of new variants at bay. We are not out of the woods just yet.

Scrutiny in a climate and nature emergency – engaging with disruptive change

Alexa Morrison, Senior Researcher, Environment

We are living through a climate and nature emergency. Politicians are declaring this the world over, but it has been declared by scientists for many decades.

In 1979, David Attenborough stated:

The fact is that no species has ever had such wholesale control over everything on earth, living or dead, as we now have. That lays upon us, whether we like it or not, an awesome responsibility. In our hands now lies not only our own future, but that of all other living creatures with whom we share the earth.

Life On Earth, 1979, Fontana/Collins

This emergency – the ‘twin crisis’ of climate change and biodiversity loss - hasn’t seen the ‘blue light’ response of COVID-19 or even the 2008 financial crash – but it must, and Parliaments have a key role to play – in scrutinising, legislating and approving government budgets.

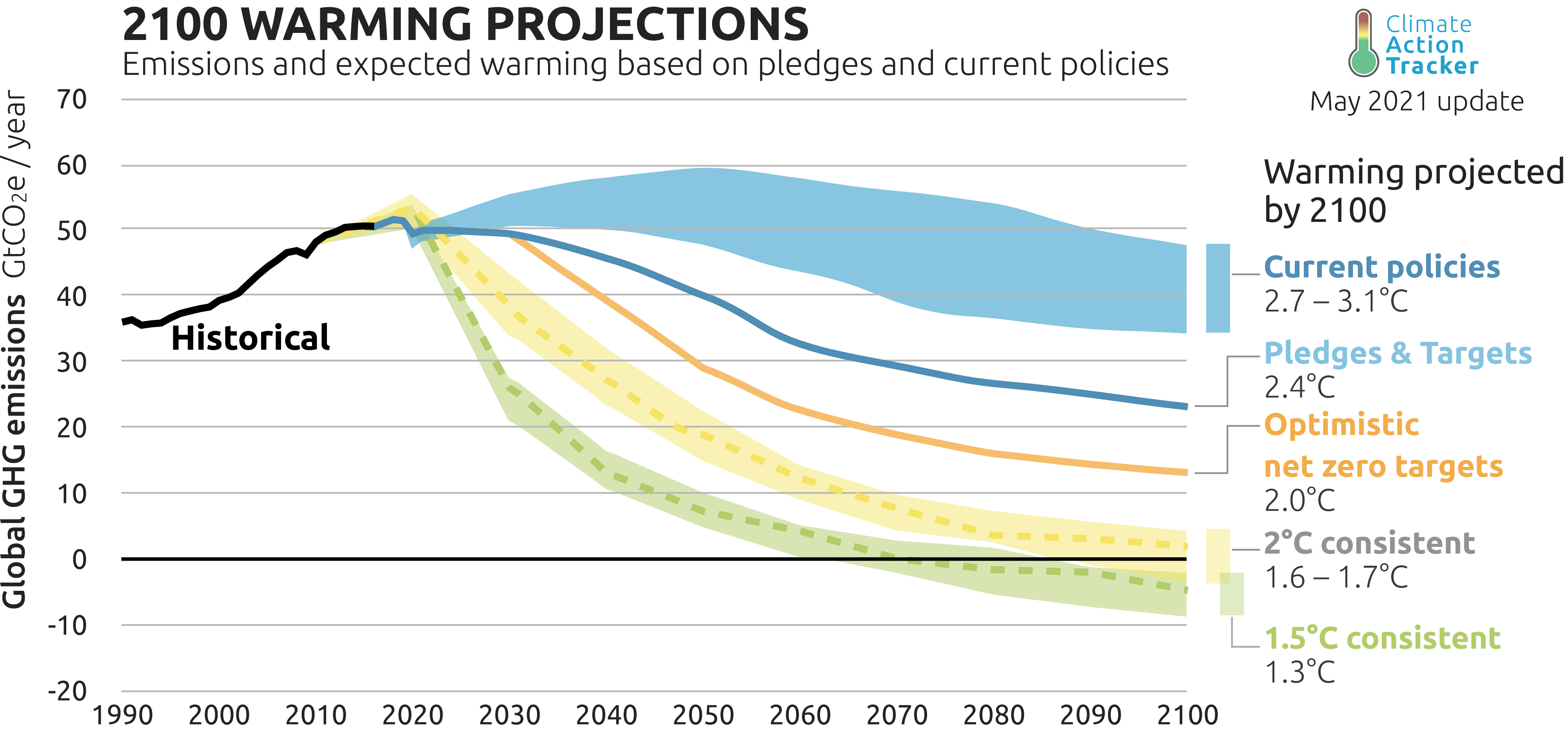

Excess greenhouse gases (GHGs) are causing global temperatures to rise and long-term changes to our climate, with impacts including sea level rise, flooding, and heat-waves. The average temperature of the Earth’s surface has risen by around 1°C since the pre-industrial period. 2020 tied with 2016 as the hottest year on record, and 17 of the 18 warmest years on record have occurred in the 21st century. Avoiding further dangerous levels of climate change is essential for human safety, health and wellbeing, economies and natural ecosystems.

The Paris Agreement, agreed under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, commits countries to limit global temperature rise to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit that to 1.5°C. In November 2021, the spotlight will turn to Glasgow, where the UK is hosting the 26th UN Climate Change Conference, ‘COP26’. For the Scottish Parliament, this brings opportunities to enhance climate scrutiny - learning from international best practice and sharing our learning. For more on COP26, see our dedicated chapter focusing on the conference.

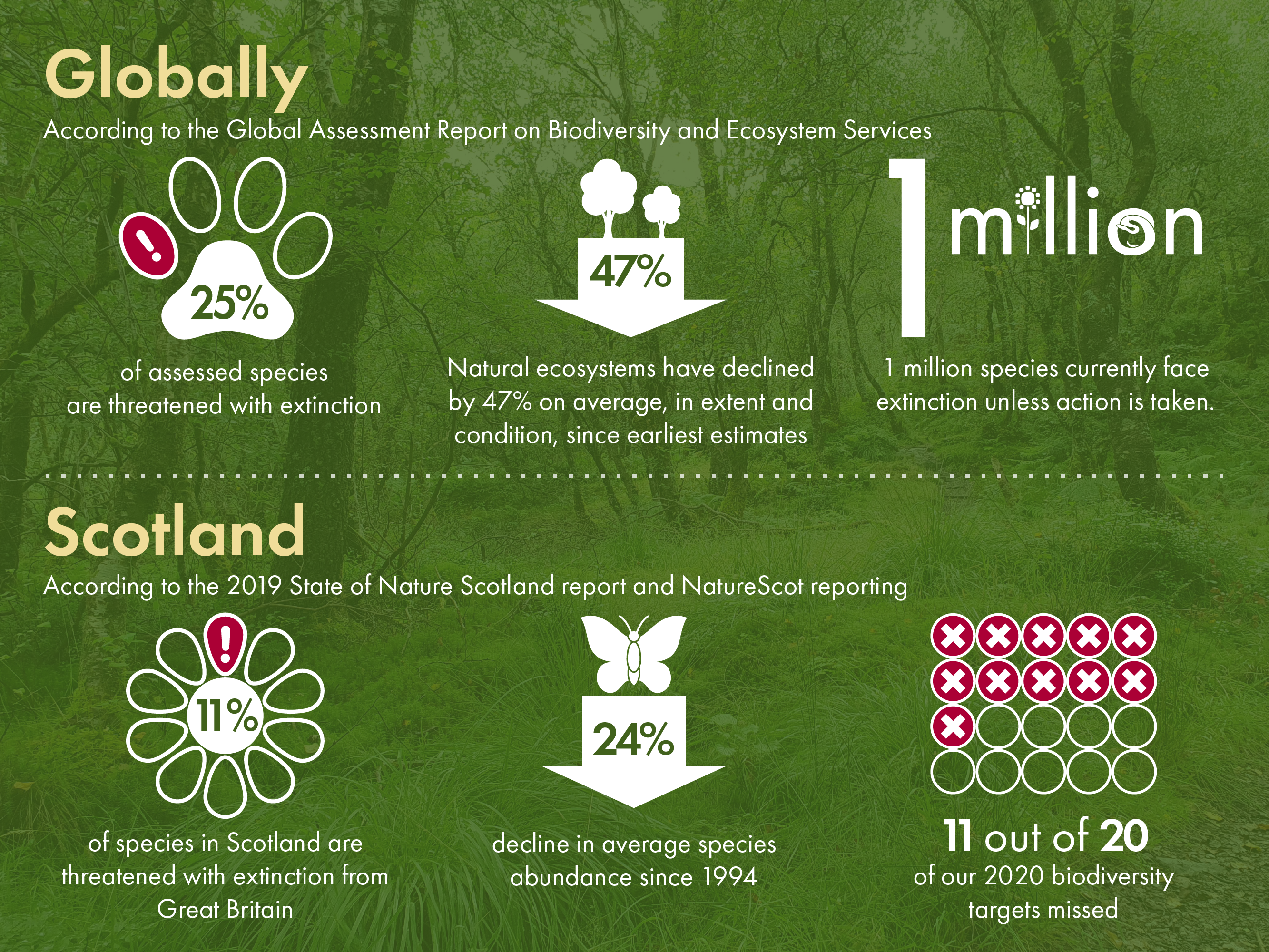

Recent global reviews also highlight the extent of biodiversity decline on land and at sea. The landmark 2019 Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services or ‘IPBES review’ issued a stark warning that nature is declining at unprecedented rates, and that most of the 2020 targets under the UN Convention on Biological Diversity will be missed. Goals for 2030, expected to be agreed at the 15th biodiversity COP in China later this year, will only be achieved, the review states, through ‘transformative change’.

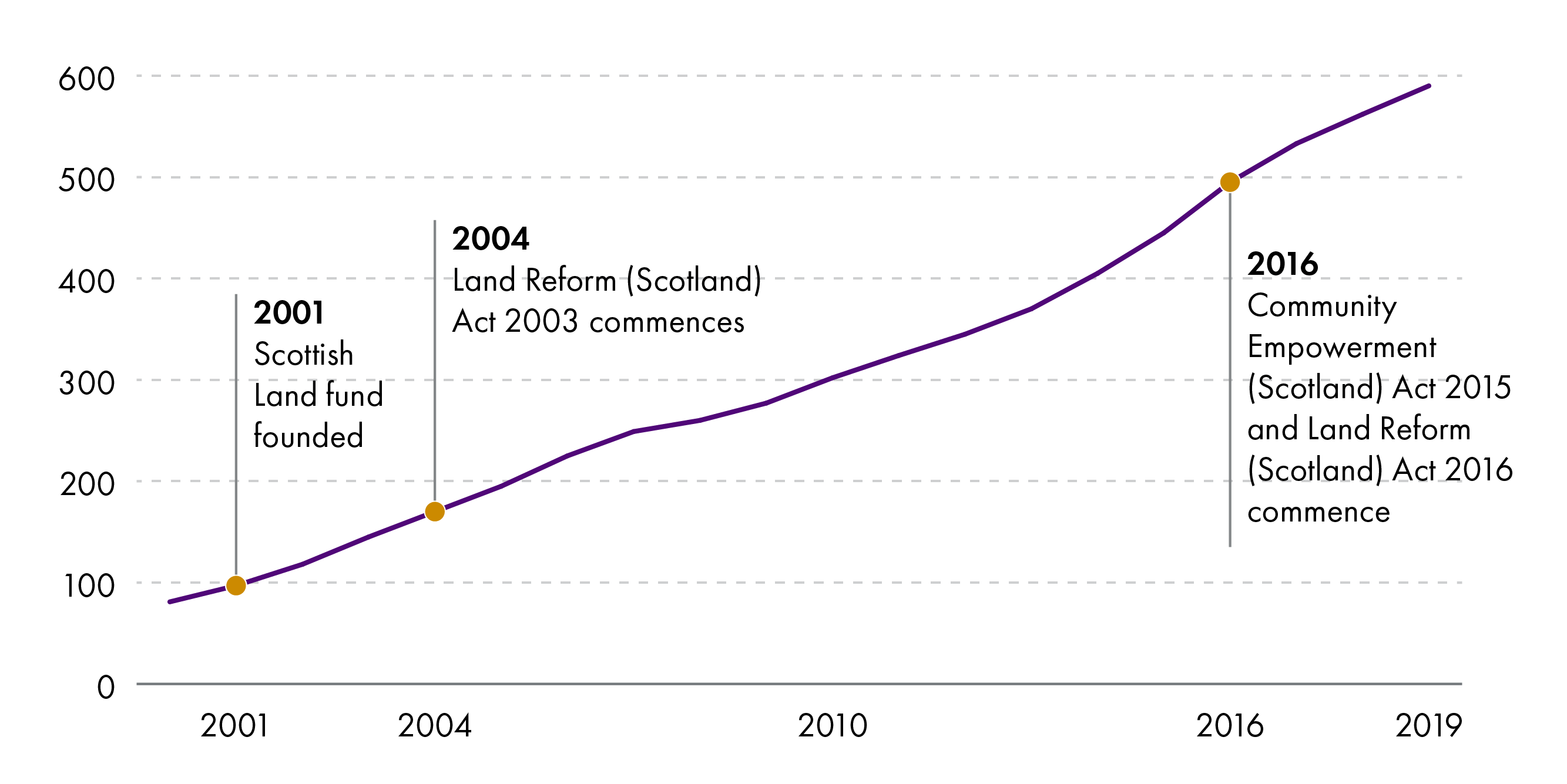

The climate and nature scrutiny challenge

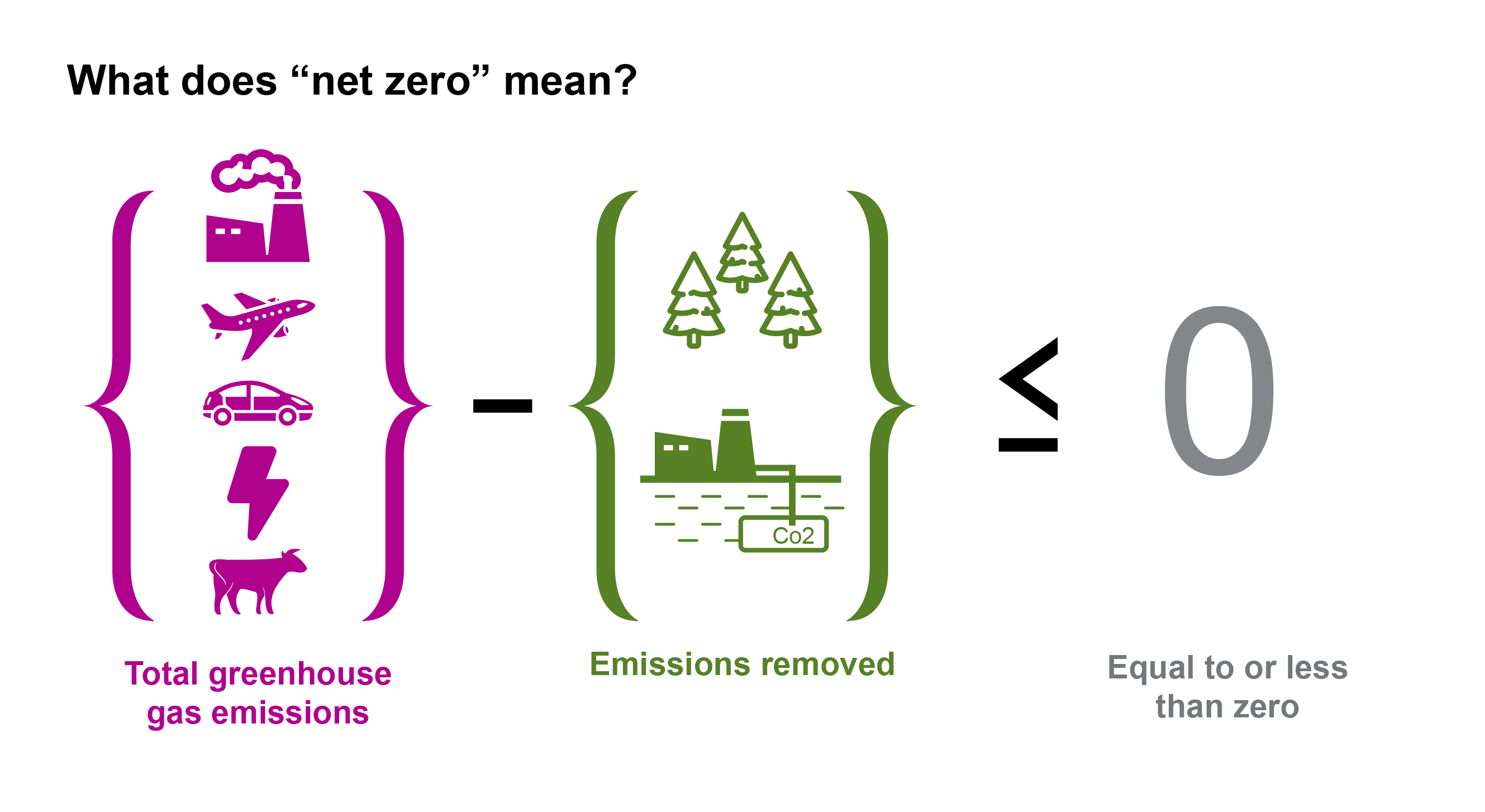

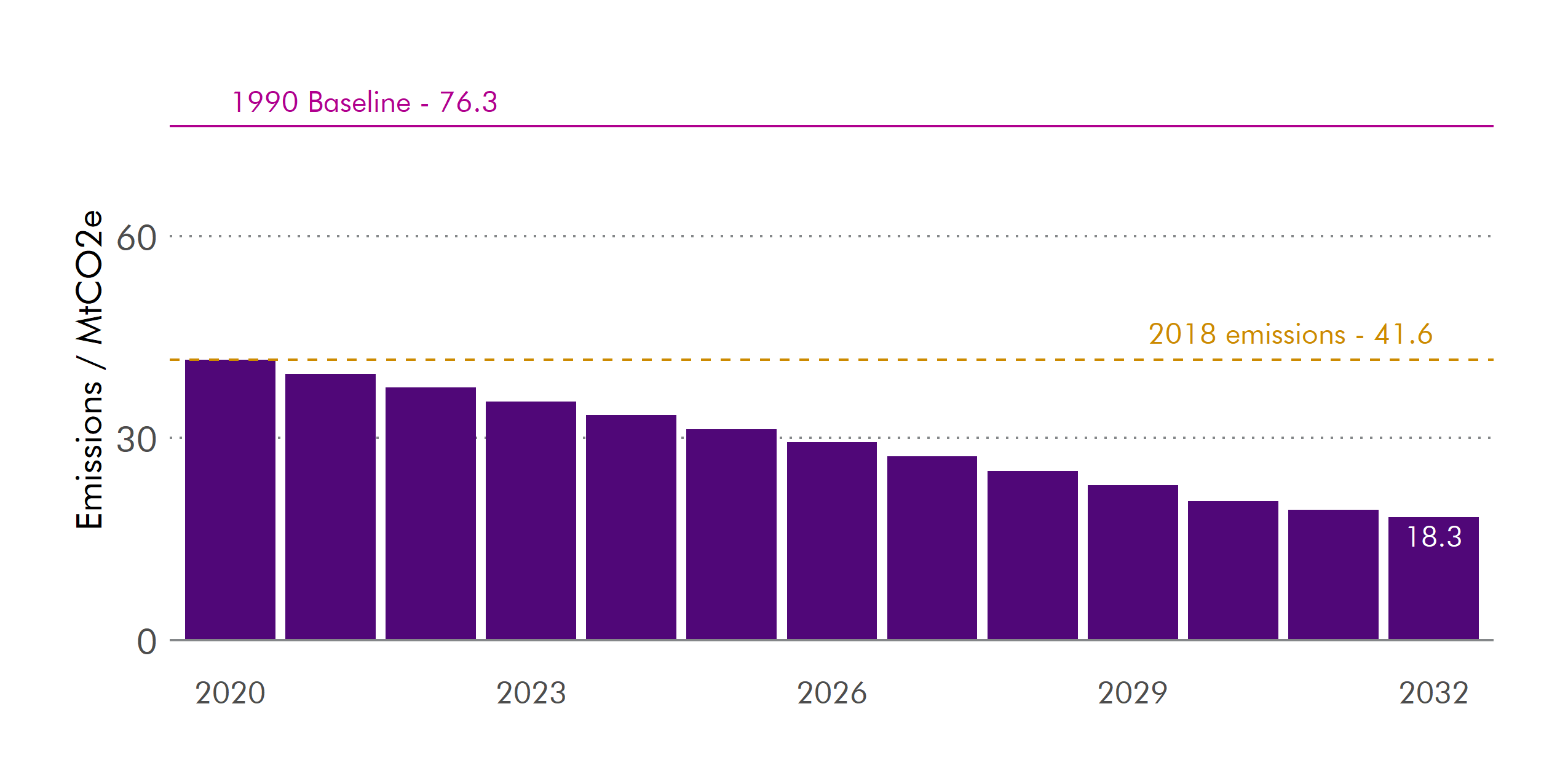

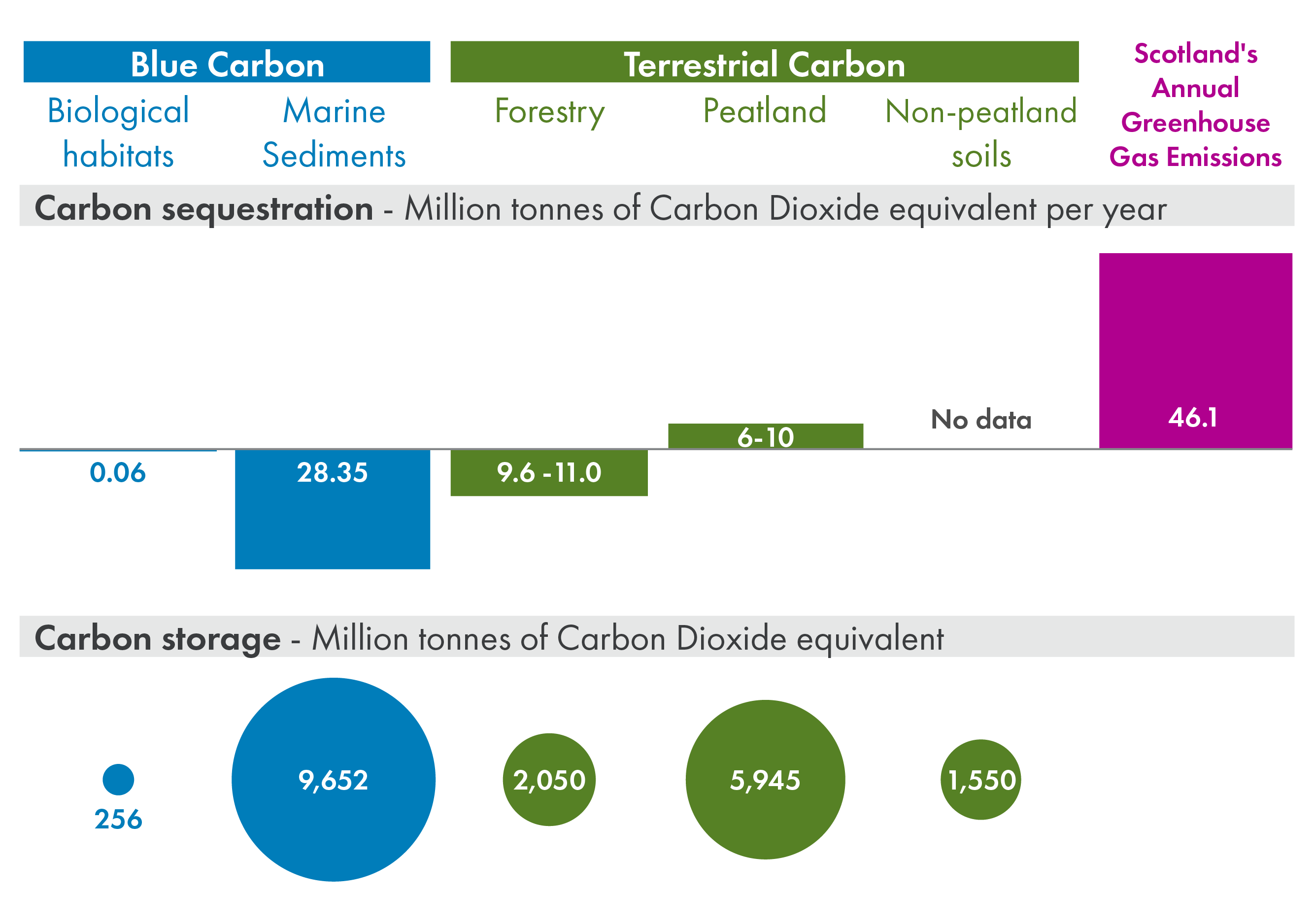

Recognition of the need to seriously tackle climate change escalated through Session 5 of the Scottish Parliament – including the declaration of a climate emergency by the Scottish Government in 2019. This was followed by the passing of the Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Act 2019 which set a target to reduce GHG emissions in Scotland to net zero by 2045. This means that net Scottish emissions must be reduced to at least 100% lower than the baseline year of 1990, through a combination of both reducing emissions and removing GHGs from the atmosphere (see the image below). Between 1990 and 2018, there was a 45.4 % reduction in emissions, with the most significant progress made in energy supply (70.1% reduction). However, many other areas, in particular transport, have stalled.

The previous Scottish Government committed to put climate change at the heart of policy-making. With an interim target to reduce emissions by 75% by 2030 now set in law, this Parliamentary session is likely to see climate scrutiny increase as strategies are developed and implemented. The image below shows the emissions reduction anticipated to take place under the current Climate Change Plan. Deep and ‘disruptive’ change is expected across all sectors of the economy including transport, industry, housing, infrastructure, agriculture and land use, and the development of a more circular economy.

This level of societal change will require coordinated scrutiny and engagement by the Parliament on the implications – including risks and opportunities - for the Scottish people, economy and its environment. Recognising that climate policies have real impacts on livelihoods, the 2019 Scottish Climate Act sought to embed principles of a ‘just transition’ into climate policy-making. The Act sets out the importance of reducing emissions in a way which supports sustainable jobs, and ultimately helps to address inequality and poverty.

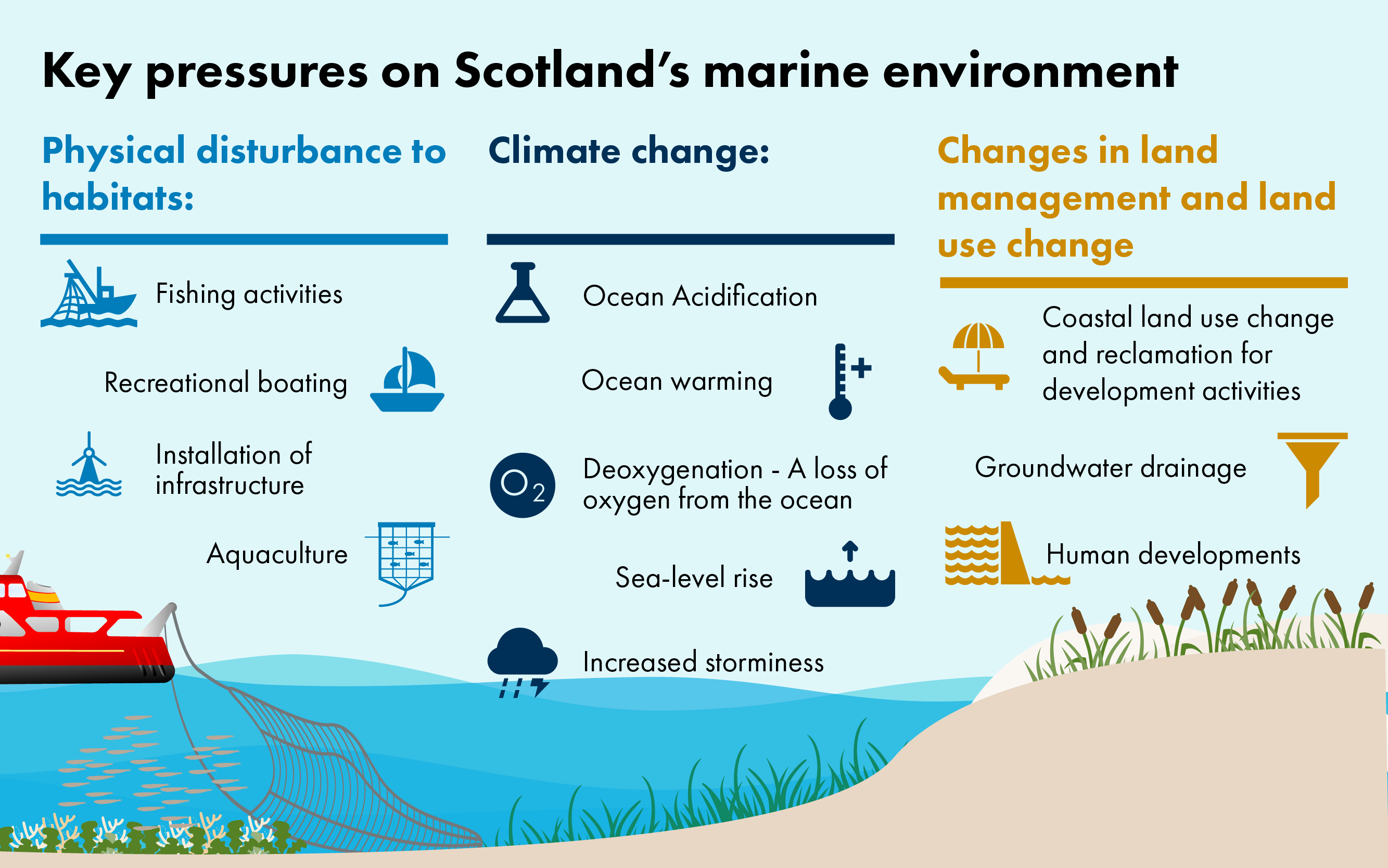

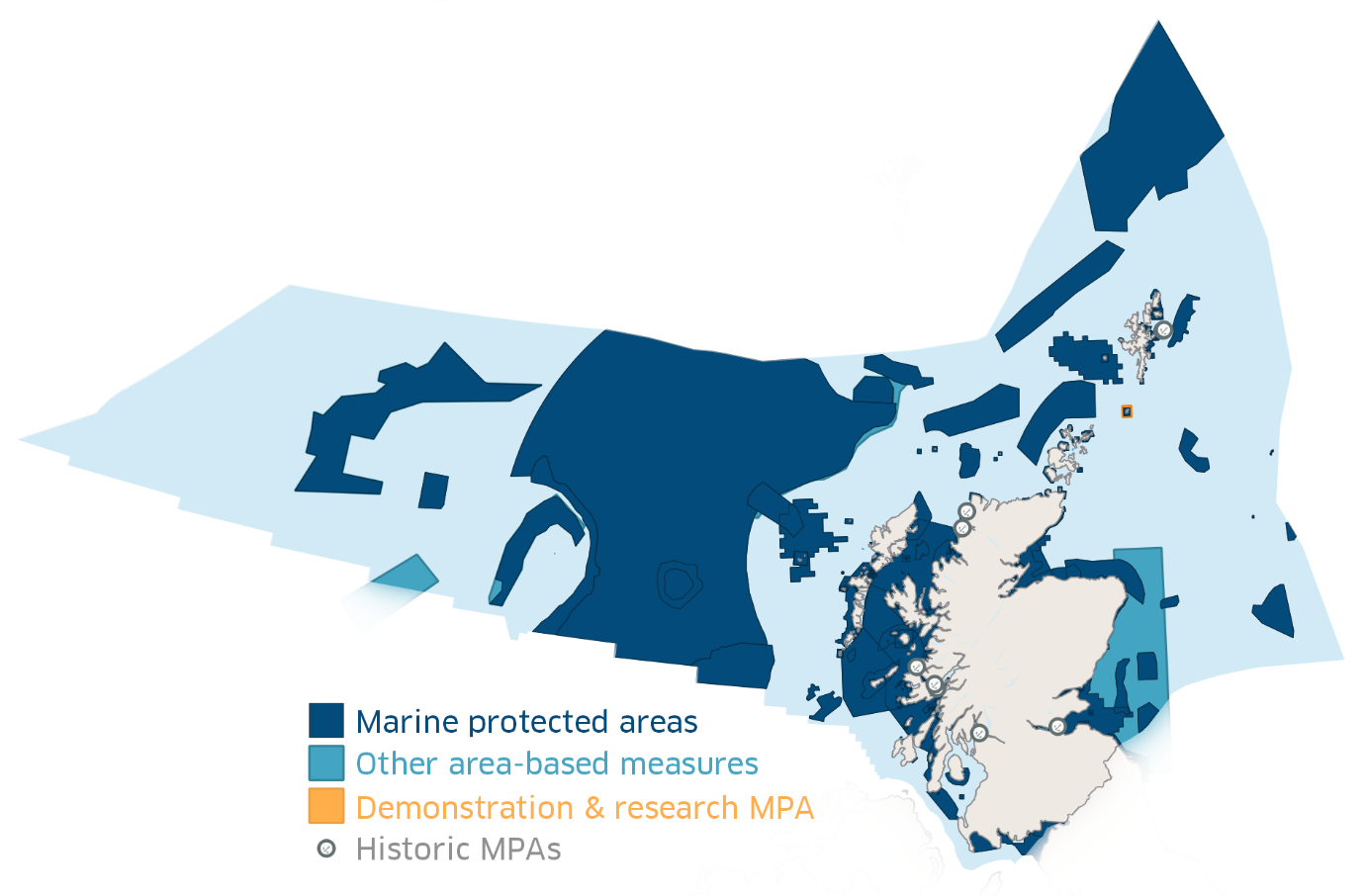

Evidence of biodiversity decline and its implications also led the previous Scottish Government to commit in 2019 to a step change in efforts to address it. The 2019 State of Nature in Scotland report mirrored the global picture, illustrating that there has been no let-up in the net loss of nature in Scotland. Nearly half of the country’s species have declined in the last 25 years, and one in nine is threatened with extinction from Great Britain (the scale at which assessments are made) Key pressures include agriculture, climate change, urbanisation, invasive species, upland management and fisheries. Scotland failed to meet 11 of the 20 Aichi biodiversity targets for 2020. The Environment Strategy for Scotland, published in 2020, recognised that the climate and nature crises are intrinsically linked. Climate change is a significant contributor to biodiversity loss and impacts on biodiversity are expected to be significantly greater if warming exceeds 1.5 degrees. Scaling up nature-based solutions to climate change such as peatland restoration and enhancing woodlands, could, on the other side of the coin, be significant in delivering Paris Agreement goals.

A range of other chapters in the key issues briefing go into different sectors in more detail - for example on Scotland's "blue economy", rural policy and on reducing car travel.

Opportunities for a green recovery – what are we aiming for?

The pandemic has led to calls for a ‘green recovery’ - to achieve dual aims of stimulating our economy whilst transitioning to a low carbon society and protecting the environment. The UK Climate Change Committee has advised the Scottish Government to use climate investments to support recovery, lead a shift in behaviours, and ensure the recovery does not ‘lock-in’ emissions.

The pandemic has also brought some sustainability issues more sharply into public discourse and our day to day lives - the issue of equitable access to green space, for example, or how transport infrastructure should meet changing needs amid Covid-19 restrictions.

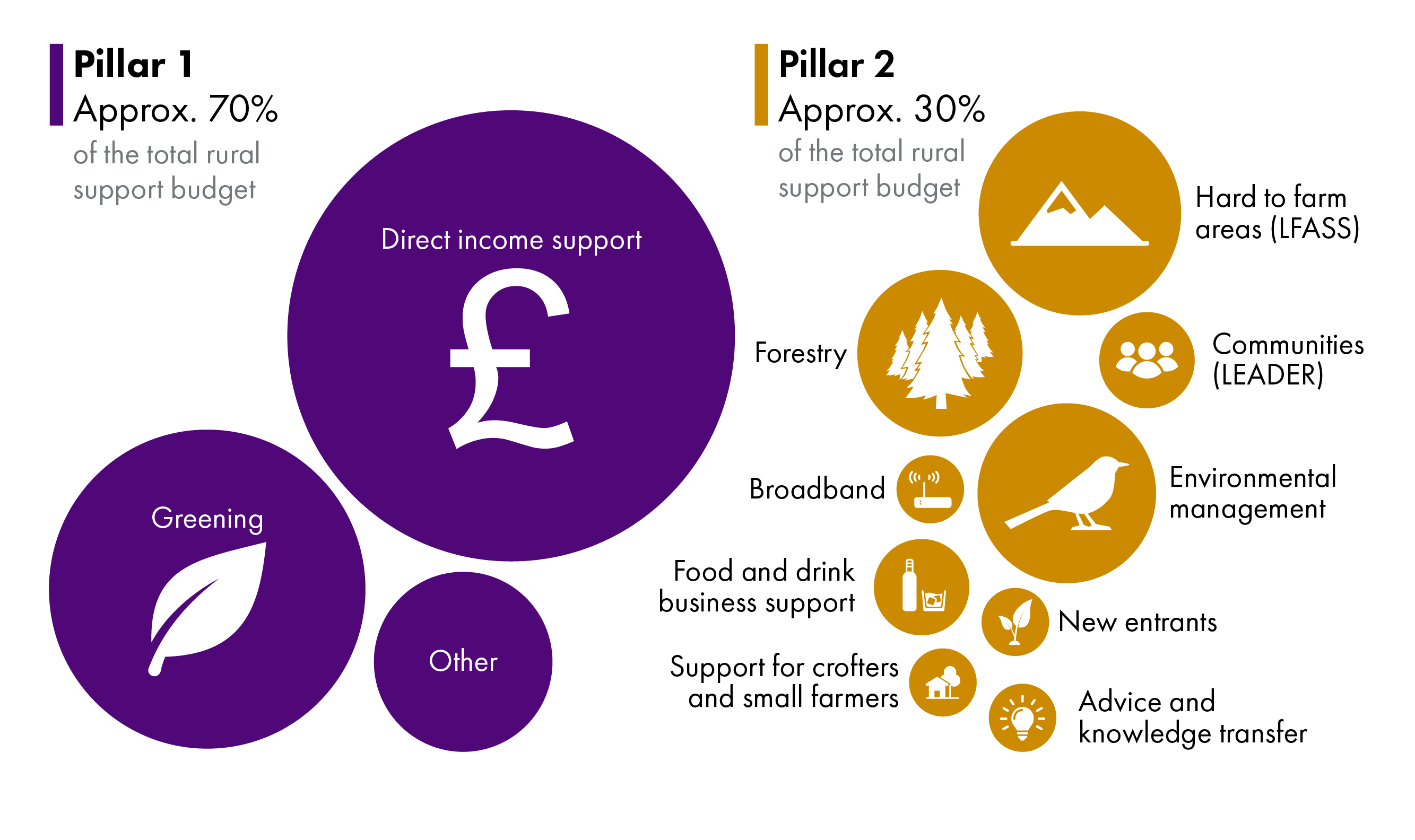

EU exit is still part of the ‘setting’ for a climate and nature emergency-response. Brexit has meant a number of significant policy, funding and legal frameworks need to be re-built. For example, the development of post-EU exit approaches to agricultural support, fisheries, or regulating chemicals share a common thread: they matter for the climate and for nature. More information on this is available in the section on Scotland's rural policy and also in the section on Scotland's blue economy.

Looking ahead to other key areas of policy development likely to take place this Parliamentary session, the following could be scrutinised in relation to a green recovery:

How infrastructure investment will support a low carbon, circular economy.

How changes to food policy can contribute to health and sustainability goals.

How economic strategies measure prosperity.

How town centres will be supported to give space to people and nature.

Our sections on infrastructure investment, food policy, a Scottish economic strategy and town centre regeneration cover all these issues in more detail.

Delivering a just transition will not fit neatly within governmental remits, parliamentary committees, and sections of society. Almost every policy area is likely to play a part. Climate ‘governance’ has evolved to recognise this, from the setting of targets and agreement of strategies across governmental remits, through to how those strategies – most significantly Scotland’s Climate Change Plan - are scrutinised in the Scottish Parliament. Governance for nature recovery is less developed in comparison, but there is increasing recognition - internationally and domestically – of the need to ‘mainstream’ the protection of nature.

Parliaments also have a wider role in ensuring Governments deliver on commitments to achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which aim to provide a shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet. The Scottish Government seeks to implement the SDGs via its National Performance Framework.

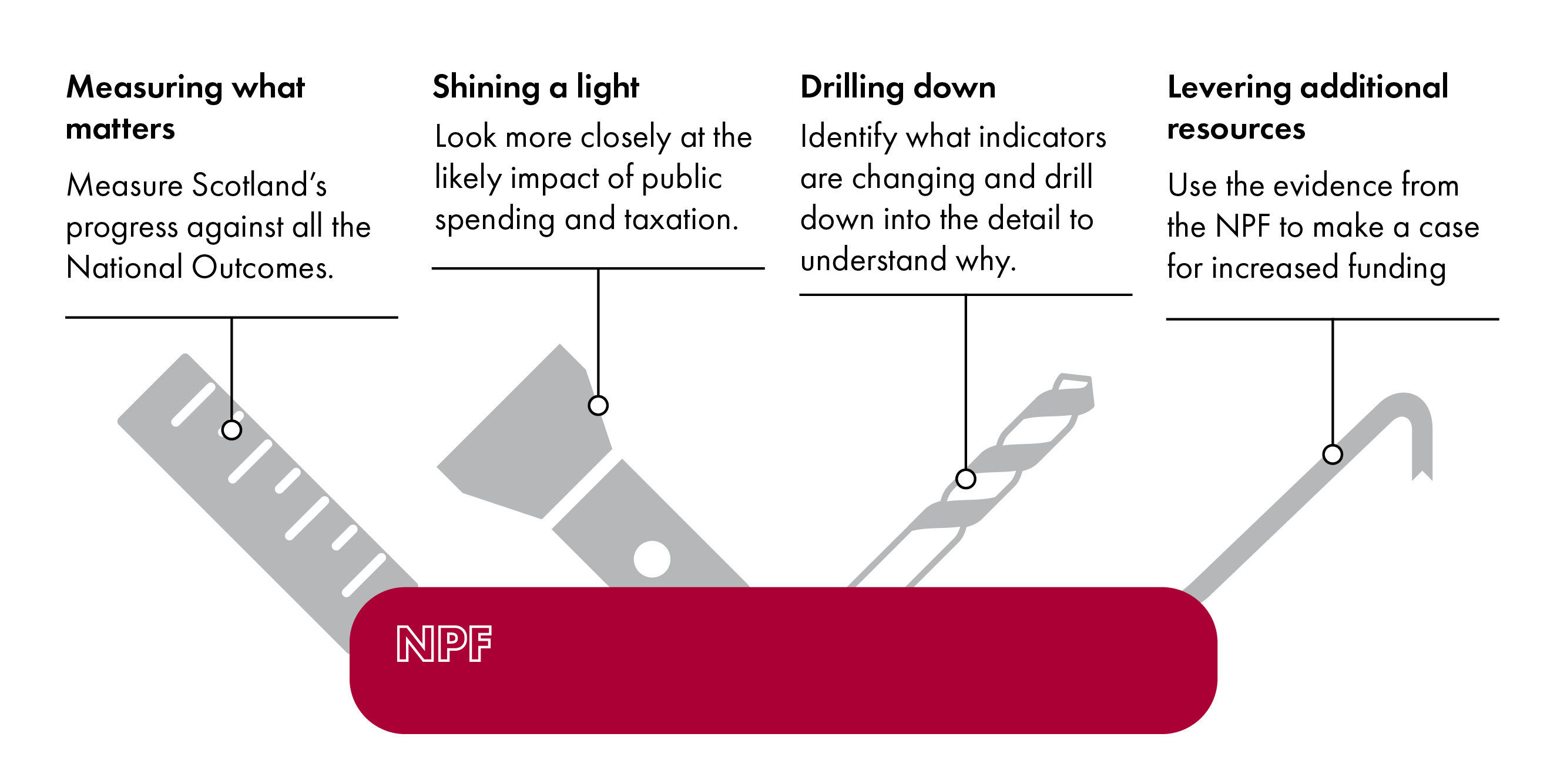

The Parliament has committed to establish sustainable development as a scrutiny lens. This involves scrutinising the relationships between social, environmental and economic issues, and identifying joined-up solutions. The Conveners Group Session 5 Legacy Report highlighted that sustainable development is wide-reaching in scope and impact, and that committees must examine their practices to help achieve a step-change in this area. By doing so, this will help the Parliament meet a duty of Scottish public bodies under the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 to act sustainably. There is a lot more about how the Parliament could use the NPF in our chapter titled "your multi-use parliamentary power tool."

The devolution settlement post EU exit and UK relations

Sarah Atherton, Senior Researcher, Constitution

.png)

The UK leaving the European Union (EU) was a seismic constitutional shift. EU exit removed an element of the UK’s constitutional framework which had been in place for nearly 50 years.

The move away from EU membership has brought the devolution settlement into sharp focus for two reasons:

The question of whether competencies previously held by the EU (including in devolved areas) should sit with the UK Parliament or the Scottish Parliament.

The practical and legal changes to the framework of devolution because of EU exit and the approach taken by the UK Government to address the question of competence.

These two issues will be central to much of the work of the Parliament during Session 6. This section provides an overview of the key changes in the devolution framework as a result of EU exit. The consequence of the changes will be felt particularly in policy areas where the EU previously had competence (such as fisheries, agriculture and food).

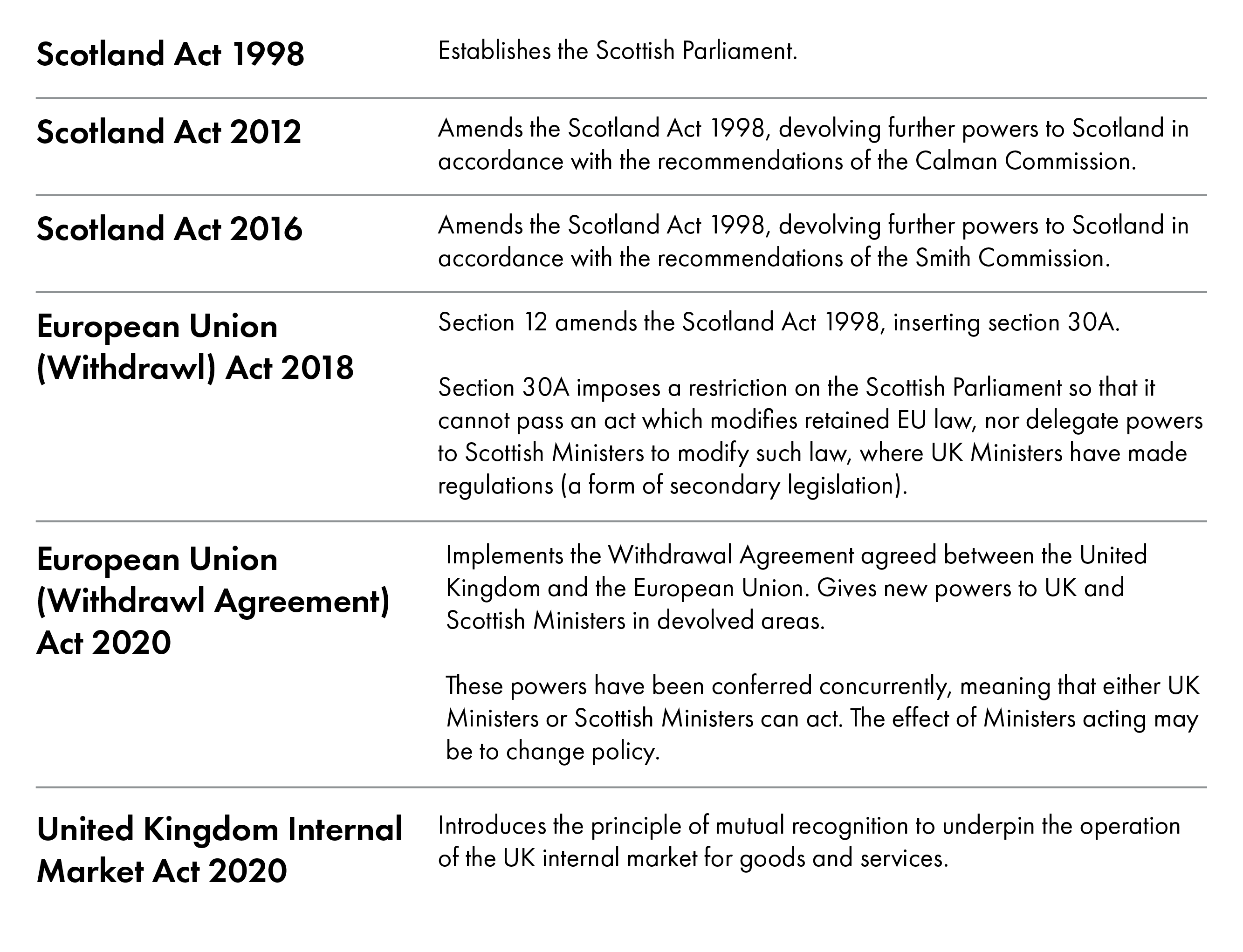

The devolution settlement

The Scotland Act 1998 (as amended by Scotland Act 2012 and Scotland Act 2016) does not specify matters which are devolved to the Scottish Parliament, but rather matters which are reserved to the UK Parliament. Matters which are not reserved are devolved and the Scottish Parliament has full legislative power (i.e. can pass Acts of Parliament) in these areas.

The UK Parliament retains authority to legislate on any issue, whether devolved or not. By convention - known as the Sewel Convention - the UK Parliament asks for the Scottish Parliament’s consent before making primary legislation (Acts of Parliament) in devolved areas. This consent is not legally binding, meaning that the UK Parliament is able to pass primary legislation in devolved areas even where the Scottish Parliament withholds consent.

Before EU exit, the UK as a member state (and Scotland as a nation of the UK) was required to comply with EU law in many areas. EU law had primacy over areas of domestic law and there were some areas in which the EU alone could legislate and adopt binding acts (known as exclusive competence).

This meant that, before the UK left the EU, the Scottish Parliament could only legislate in areas not reserved to the UK Parliament and in a way that was compatible with EU law.

From 1 January 2021, the need to comply with EU law fell away, meaning there was no longer a requirement for the Scottish Parliament to legislate in a manner compatible with EU law.

Nevertheless, new constitutional arrangements and UK-wide legislation have had an impact on the Scottish Parliament.

Preparation for the UK’s exit from the EU

In preparing for EU exit, the UK and its nations had to manage two things:

ensuring that the laws already in place as a result of EU membership functioned effectively after exit to avoid legal uncertainty in key areas

deciding which legislatures within the UK would gain the powers to change laws or create new laws in areas previously within EU competence.

Given the many UK and Scottish laws as a result of EU membership, there was the potential for these laws to be ineffective once the UK left the EU. To avoid a legislative cliff edge, the UK Government worked to preserve the legal position which existed immediately before 1 January 2021 (the date on which EU law ceased to apply in the UK). This legal continuity was achieved by taking a snapshot of all EU law that applied in the UK and bringing it within the UK's domestic legal framework as a new category of law, known as “retained EU law”.

Changes still needed to be made to retained EU law to ensure that laws in this category functioned effectively by, for example, removing references to EU institutions. This deficiencies correcting exercise saw hundreds of statutory instruments and over 50 Scottish statutory instruments made. A SPICe blog ‘Statute still’ examined the deficiencies exercise in more detail.

The other area which needed to be settled was which legislature would have powers to be able to change or make new laws in areas previously within EU competence. The fact that competencies previously held by the EU were to return to the UK, whilst the need to comply with EU law fell away, meant a potential expansion of the legislative powers of the Scottish Parliament.

However, section 12 of the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 passed by the UK Parliament (the Scottish Parliament withheld consent under the Sewel Convention) amended the Scotland Act 1998, inserting section 30A. Section 30A imposes a restriction on the Scottish Parliament so that it cannot pass an act which modifies retained EU law, nor delegate powers to Scottish Ministers to modify such law, where UK Ministers have made regulations (a form of secondary legislation).

This restriction only applies to areas where the EU had competence immediately before 1 January 2021. As such, section 30A does not shrink the competence of the Scottish Parliament, but it can be used to freeze it so that the Parliament's legislative power is not increased by leaving the EU.

Section 30A ensures that the pre-Brexit parameters of devolved competence are retained for a period of up to five years from the date any regulations are made, while new arrangements (in the form of common frameworks) are developed and implemented.

New constitutional arrangements - common frameworks

EU membership meant that across the UK policies were the same or very similar in many areas. The UK’s exit from the EU saw the potential for significant policy divergence across the UK nations.

Given that possibility, the UK and devolved governments agreed that common frameworks could be used to ensure that, in certain policy areas, the rules and regulations remain consistent across the UK. It is expected that there will be around 24 common frameworks covering areas like animal health and welfare, food labelling and blood safety.

Common frameworks are agreed between governments. Legislatures do not consent to frameworks but scrutinise the decisions of Ministers to enter into them. A SPICe paper on common frameworks explores the topic. The SPICe Post-Brexit hub details all of the work carried out by the Scottish Parliament on frameworks.

As a result of frameworks, intergovernmental relations may assume greater importance through Session 6.

Key legislation

The European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020 gives UK and Scottish Ministers new powers in devolved areas that go beyond correcting deficiencies.

These powers have been conferred concurrently, meaning that either UK Ministers or Scottish Ministers can act. The effect of Ministers acting may be to change policy.

The Scottish Parliament has agreed a protocol with the Scottish Government on the scrutiny of any UK statutory instruments made under the European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020 and some other Brexit related legislation.

There are two additional pieces of Brexit related legislation which will likely assume central importance in Session 6.

Part 1 of the UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Continuity) (Scotland) Act 2021 enables Scottish Ministers to keep devolved law aligned with EU law.

The Act does not mean that Scots law has to align with EU law, but it does allow Scottish Ministers to make regulations to keep pace where they feel it is appropriate. It will be the Parliament’s responsibility to scrutinise the use of this keeping pace power by Scottish Ministers.

Further information is available in the SPICe briefing on the UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Continuity) (Scotland) Bill.

The United Kingdom Internal Market Act 2020 establishes two market access principles to protect the flow of goods and services in the UK’s internal market:

the principle of mutual recognition means goods and services which can be sold lawfully in one nation of the UK can be sold in any other nation of the UK

the principle of non-discrimination means authorities across the UK cannot discriminate against goods and service providers from another part of the UK.

The market access principles mean that legislation passed by the Scottish Parliament will apply to producers and service providers in Scotland but will have no effect in relation to goods or services coming into Scotland from elsewhere in the UK.

UK Government Ministers have the power to disapply the market access principles where the four governments of the UK have agreed that divergence is acceptable through the common frameworks process.

The provisions of the United Kingdom Internal Market Act may have a significant impact on the exercise of powers by the devolved legislatures. The market access principles have the potential to undermine devolved competence. Further information on the UK Internal Market Act 2020 can be found in a SPICe blog.

Challenges for Session 6

The Session 6 parliament will have to grapple with the complexities of new constitutional arrangements and the practical limits they may place on the Scottish Parliament even in areas over which it has competence.

Health and Social Care integration: are the joins still visible?

Anne Jepson, Senior Researcher, Health and Social Care

This briefing will provide a short overview of the major structural change to health services in Scotland over the last few years. It will highlight some of the ongoing challenges which will continue into the next session, as well as the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on accelerating reform of the social care sector.

The Scottish Government says that the integration of health and social care has been the ‘most significant change to health and social care services in Scotland since the creation of the NHS’. Whether this has been the experience of staff and the public remains, for the time being, moot.

What has integration entailed: the theory and legislation?

Throughout Session 5, the integration project dominated the work of the Health and Sport Committee, as the public bodies involved sought to implement major shifts in focus and culture from hospital to community-based care.

The Public Bodies (Joint Working)(Scotland) Act 2014 (“the Act”) received Royal Assent in April 2014. Health boards and local authorities were then given two years to put integration arrangements in place. Somewhat confusingly, IAs are also known as Integration Joint Boards (IJBs) and Health and Social Care Partnerships (HSCPs). Each IA is partnered with one of the fourteen health boards.

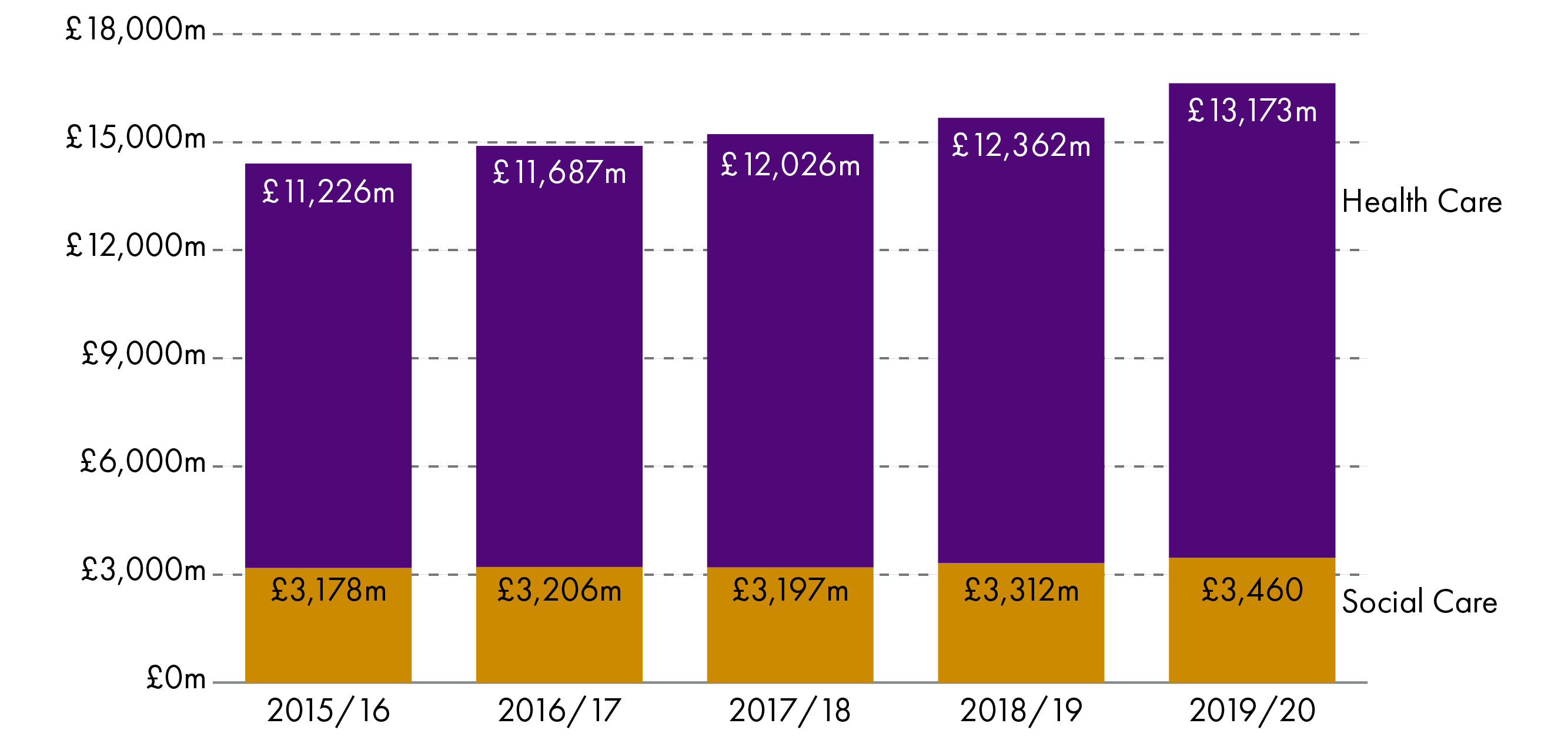

The aim was to create a new governance structure that brings together health boards and local authorities, without replacing either. The ambition is to embed joint working. This has been done by giving IAs responsibility for directing an £8 billion + budget (allocated from both local authorities and the NHS). The IAs are to design, commission and create services that meet the health and care needs of people at a local level, designed with the person at the centre.

What led up to integration?

The Act was the culmination of years of effort: of different programmes and of legislation, to encourage partnership working between the NHS, social work and the third sector, that had been running since the Scottish Parliament came into being.

Audit Scotland published a timeline of these pieces of work, since 1999, in their short guide to the integration of health and social care services 2018.

What and where are the new bodies?

The 31 new IAs generally map onto local authority areas. However, Clackmannanshire and Stirling councils combined to create a single IA. NHS Highland and the Highland Council opted for a slightly different model.

All IAs are responsible for the governance and resourcing (via the directing of delegated budgets) of social care, primary and community healthcare and emergency hospital care for adults, as well as discharge. Some areas have also integrated additional services such as children’s services and criminal justice. Their reach across local services then is huge, and their existence offers substantial potential for change in how services are designed and delivered.

So far so good. How well has integration progressed?

Throughout Session 5, frustration and concern were expressed by both the Health and Sport Committee, and Audit Scotland, about the pace of change and transformation:

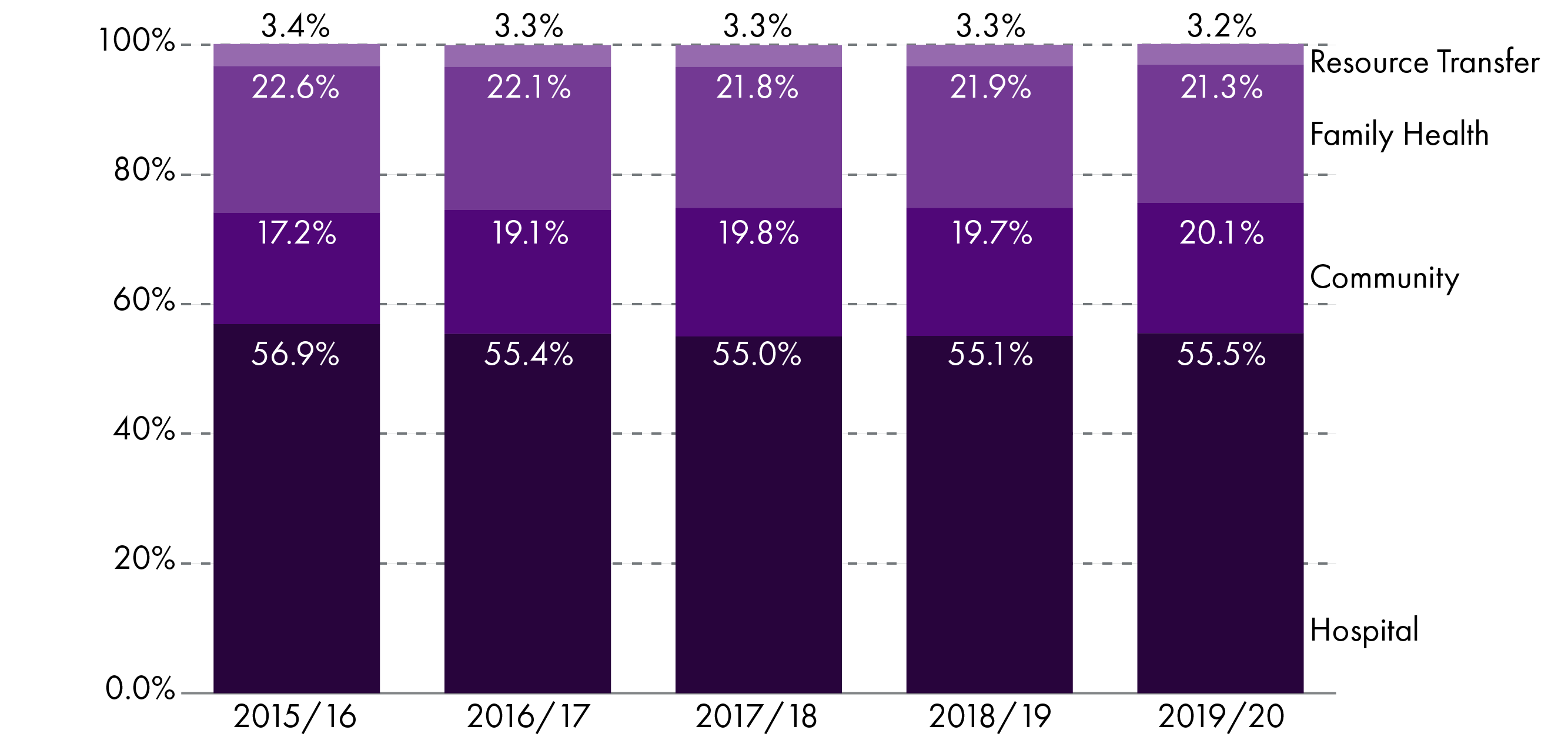

Since 2016/17, integration authority annual budgets have totalled almost £9 billion, with little evidence of a shift in spending from hospital to community care ... Issues noted in integration authority budget processes include delays in agreement, lack of transparency, relationship issues, and inability to make medium or long-term plans.

(source: SPICe Briefing: Health and social care integration: spending and performance update)

The NHS has become recognisable by increasingly enormous physical buildings, where all sick people are cured. The move is to a patchwork landscape of community-based services that focus on the prevention of sickness, the promotion of wellbeing and independent and supported living. This should reduce, in theory, demand on the hospital sector.

The chart below shows how little budgets have changed between hospital and community care, with hospital spending accounting for well over half the total budget. These modest changes continue in the latest figures, although in 2019-20:

The £811m increase in expenditure was not shared evenly across the different sectors. Of the total increase, £499m (62%) was spent on hospital services, £203m (25%) on community services and £99m (12%) on family health services.

The Act, along with other legislation, such as Self-directed Support (Scotland) Act 2013, was to underpin an approach to health and social care that shared a focus on care and support being delivered as close to home as possible and of maintaining someone’s independence for as long as possible. Emergency care was to be the last resort and delayed discharge would be addressed by making integration authorities responsible for discharge arrangements from hospital.

The government used the Ministerial Strategic Group (MSG) to provide added momentum to integration, and published an update on progress in February 2019. However, the most recent meeting of the group was in January 2020. Will the momentum, post pandemic, be picked up by government and integration authorities?

Key issues for social care

To discuss social care under a different heading sort of undermines the point of the integration project. However, the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the many disparities between the NHS and social care, and some were considered by the Health and Sport Committee. The most highlighted outcome from these disparities was the high number of deaths in care homes during the pandemic (around a third of the total number). The then Cabinet Secretary for Health and Sport, Jeane Freeman, acknowledged that ministers did not fully understand the needs of the care sector.

Evidence to the Health and Sport Committee stressed that care homes are homes first, and not health facilities. (For how the pandemic impacted the NHS see NHS in Scotland 2020 Report, Audit Scotland). And for more on the wider impact of the pandemic see our first overarching theme in this briefing.

The underlying structures and operation of both health and social care have not changed, despite the legislation and the best efforts of integration authorities to commission services that fulfil the principles of integration.

So, for example, while NHS services remain free at the point of use in most circumstances, social care is in large part means-tested – people pay their accommodation costs, which are hundreds of pounds a week. The realisation of the costs involved shock many families, just at the point when they are in crisis and need care services.

The Scottish Government were conducting a major review of social care before the COVID-19 pandemic hit. The challenges in social care accelerated focus and action and an independent review of adult social care was commissioned, led by Derek Feeley. It was published in January 2021. This called for major reform of social care, which features in a number of party manifestos.

Session 6 will see tension between dealing with the backlog of hospital treatment, and the drive of integration to focus on prevention and community-based interventions. To allow better scrutiny of local and national innovation, a means of assessing and comparing outcomes for individuals is needed. Audit Scotland lays out the challenges of planning for outcomes, and particularly planning and assessing performance against the National Performance Framework.

Mental health and COVID-19

Lizzy Burgess , Senior Researcher, Health and Social Care

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic there was already high and increasing demand for mental health services in Scotland. This has been exacerbated by COVID-19. How this demand is identified and addressed will be of key interest in Session 6 and will impact on the work across all portfolios. This key issue is linked to COVID-19 recovery and expands on our overarching theme on the topic.

The COVID-19 pandemic and associated restrictions have had a significant impact on the mental wellbeing of many people in Scotland. This has varied across the population and some groups have been more negatively affected than others.

Impact of COVID-19 infection on mental health

Severe COVID-19 infection has been associated with poorer mental health. A report for the Scottish Government by Dr Nadine Cossette, found that up to one-third of COVID-19 patients admitted to hospital develop serious mental health consequences, including depression, anxiety, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), and cognitive problems.

In March 2021, the Scottish Government announced it was setting up a network of mental health clinicians to support people hospitalised with COVID-19.

Long COVID (a syndrome associated with COVID-19 infection that can persist for 12 weeks or more) is associated with reductions in mental wellbeing and can include symptoms of depression and anxiety. The Scottish Government has partnered with Chest Heart and Stroke Scotland to develop its Long COVID Support Service. In England a network of long COVID assessment centres has been established.

Impact of COVID-19 restrictions on mental health

The social restrictions and economic consequences linked to COVID-19 have also had a negative impact on many people’s mental health. For some people this has been a result of:

increased isolation and loneliness

income and job worries

fear of catching COVID-19

worries about childcare and caring responsibilities

fear of eviction or home repossession

disruption to education

higher levels of stress in cramped or confined housing.

In July and August 2020 the tracking the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and wellbeing study found that:

Some groups, including young adults, women, people with pre-existing mental health and those in lower socio-economic groups reported higher levels of mental distress.

The COVID-19 pandemic has widened mental health inequalities. The groups that had the poorest mental health pre-COVID-19 have experienced the largest deterioration. The groups that have been found to be most affected are women and young adults, people from deprived areas and people with low incomes.

The Scottish Government has established an Equality and Human Rights Forum group that will inform policy development and implementation through consultation and representation.

Children and young people have also seen significant mental health impacts resulting from factors including closure of schools and nurseries, problems arising from home schooling and care, reduced opportunity to stay active and socialise with peers. Many older children have issues with mental wellbeing, are anxious about COVID-19, family income, exam pressure and employment prospects.

There has also been a focus on the mental health of healthcare workers, with high levels of anxiety, depression and PTSD identified in staff working with people infected with COVID-19. The Scottish Government has announced funding to provide mental health support for health and social care staff.

Impact of COVID-19 restrictions on the delivery of mental health services

Prior to the pandemic, mental health services in Scotland were already under significant pressure. COVID-19 resulted in restrictions to in-person appointments and closure of support services.

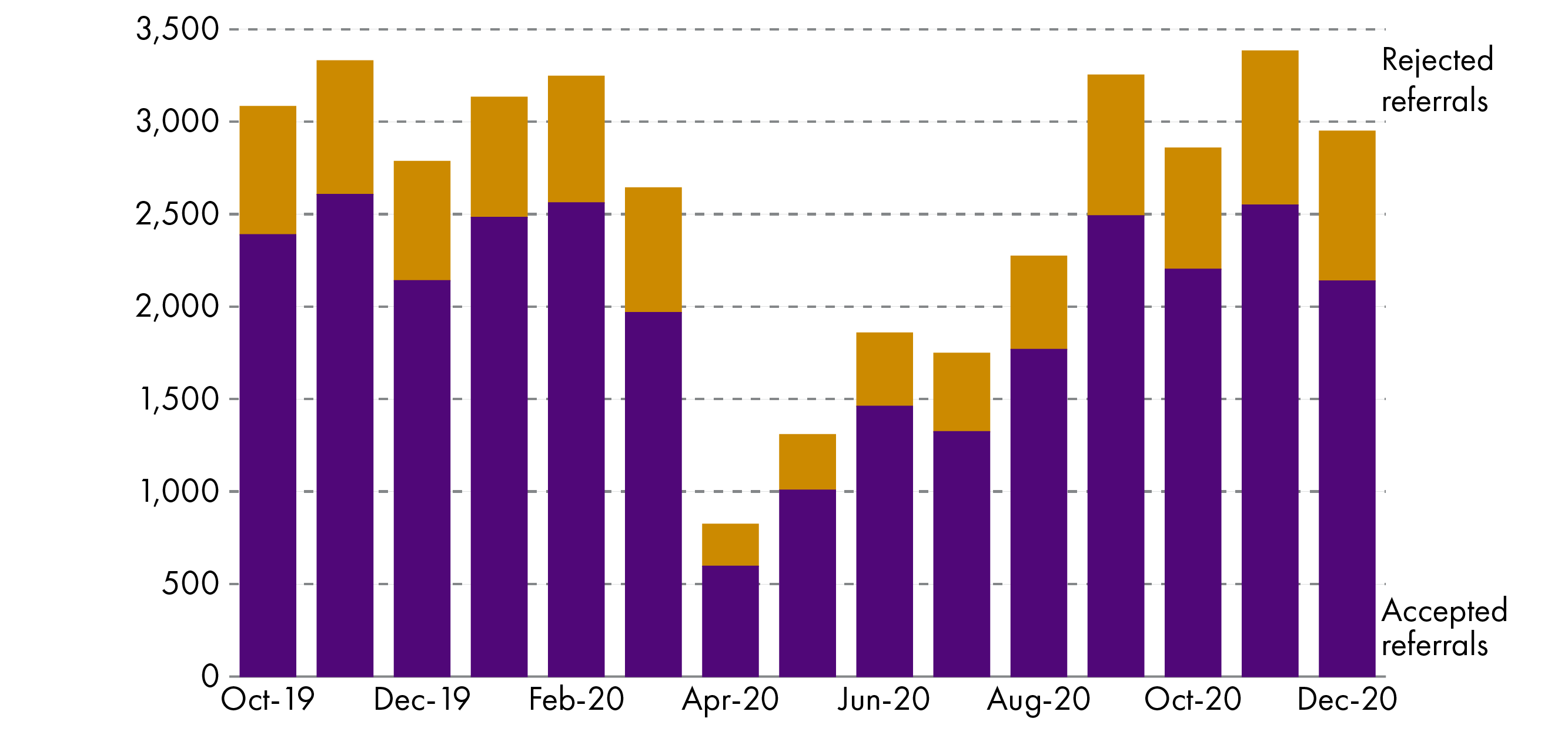

At the start of the pandemic there was a steep drop in the number of referrals to services including Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) and psychological therapies.

Since May 2020 the numbers increased as services were provided digitally but waiting times have increased. In December 2019, 5.4% of people had been waiting 53 weeks+ for CAMHS. This increased steadily – at the end of December 2020 it was 14%.

At the end of December 2020 there were 11,116 children and young people waiting to start treatment with CAMHS.

Similarities can be seen with waiting times for treatment with psychological therapies.

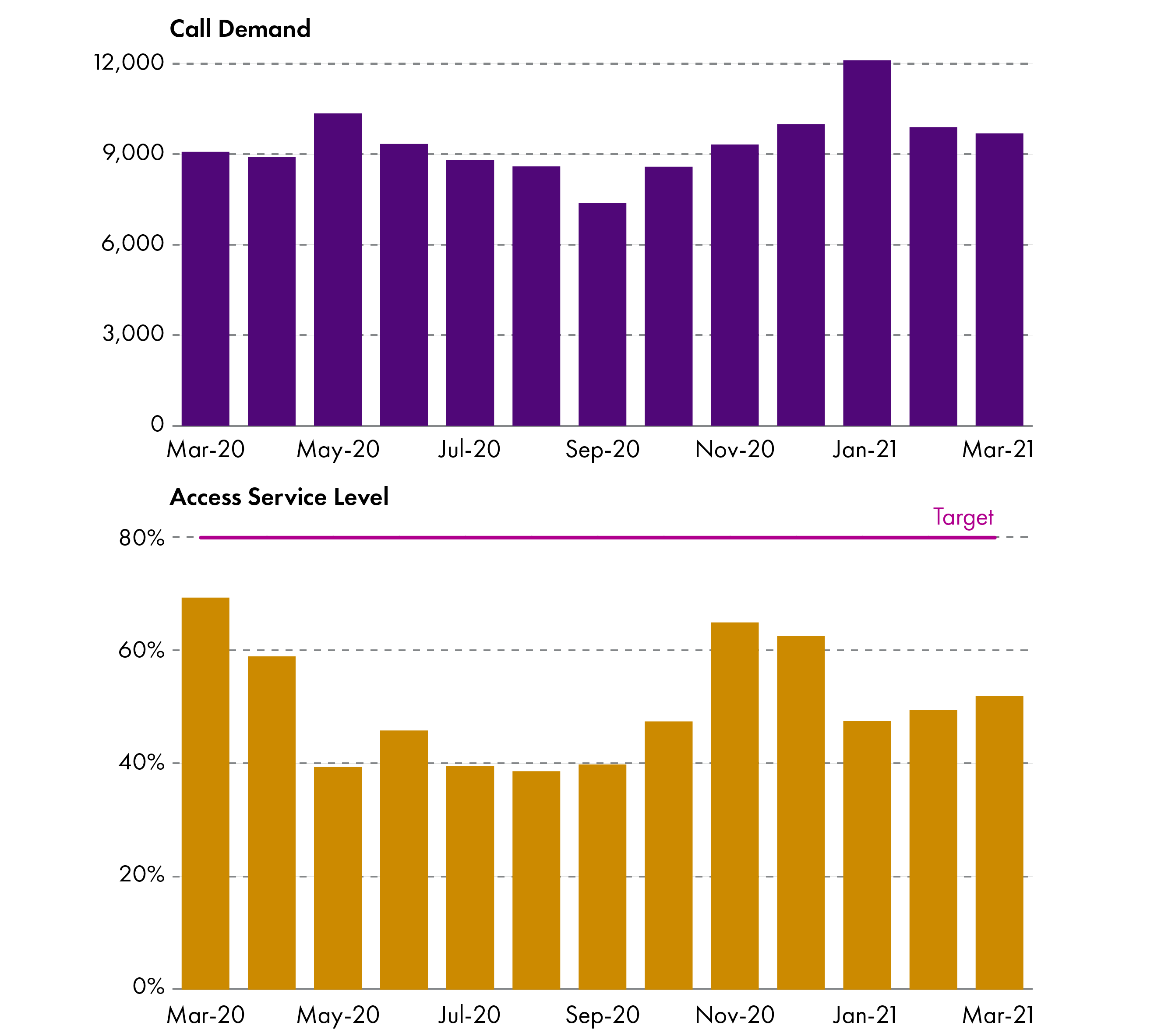

GPs serving deprived communities have reported an increase in patients with mental health problems. There has also been an increase in people calling 999 and Breathing Space for help with mental health problems. Calls to Breathing Space increased consistently between September 2020 and January 2021, with January being the busiest month.

The known and predicted effects of the COVID-19 pandemic mental health and the impact on mental health services was discussed in a think piece by Dr John Mitchell, Principal Medical Officer at the Scottish Government.

Pre-COVID, rising public awareness and demand for mental health treatment was outstripping supply.

Different populations are impacted differently – similar to existing inequalities.

Traumatic experiences for patients, care home residents and staff could lead to mental health issues.

Higher levels of distress at the start of the pandemic will be followed by a possible increase in anxiety and depressive disorders, substance misuse, self-harm and suicide.

It is estimated that there will be an 8% worsening of the incidence of mental health disorders (particularly anxiety and mood disorders and in young people and women).

The challenges will be meeting new demand and remobilising services but there is the opportunity for more individualised approaches.

Cross government work and commitment is needed.

Focus is needed on population wellbeing and mental ill health.

Scottish Government response

The Scottish Government has an overarching 10 year mental health strategy (2017 to 2027) which has 40 actions.

The Scottish Government established a Mental Health Research Advisory Group to inform the development of its mental health policy response to COVID-19. In October 2020, the coronavirus (COVID-19): mental health - transition and recovery plan was published. This details what the Scottish Government has been doing to try to address the mental health challenges. It also highlights a number of commitments in relation to:

whole population mental health

mental health inequality

support for people who are made redundant

children, young people and families

people with long term health conditions and disabilities

older people

Distress Brief Intervention programme and computerised Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

the remobilisation of mental health services.

The Scottish Government has also announced a £120 million Recovery and Renewal Fund for Mental Health, allocated from Barnett COVID-19 consequential funding.

The questions that remain are how the additional mental health needs will be addressed, and how the COVID-19 recovery plan addresses the causes of mental health inequality. The decisions around the improving the wellbeing of people and the delivery and sustainability of mental health services for those who require them will be a key issue which will impact all portfolio areas throughout Session 6 and beyond.

For a further discussion of the direct and indirect health impacts of COVID-19 see the SPICe briefing Health Inequalities and COVID-19 in Scotland.

Gender Recognition Act Reform

Nicki Georghiou, Senior Researcher, Equalities and Human Rights

As SPICe highlighted in the Key Issues briefing for Session 5, each of the five main parties referred to a review of gender recognition law in their manifestos for the 2016 election. By the end of Session 5, there had been two Scottish Government consultations on reforms to the Gender Recognition Act 2004 (GRA), but no legislative action.

However, the potential impact of gender recognition on women – and specifically the move to reform the process to one based on self-declaration – was debated in other contexts, including:

Scottish census, which for the first time would include a voluntary question on trans status. However, there was debate on whether trans people should be able to answer the sex question based on self-identification, or whether this would skew the census data. A recent high court ruling for the census in England and Wales stated that the sex question must be based on legal sex, where individuals answer the question based on their birth certificate or gender recognition certificate.

Gender Representation on Public Boards (Scotland) Act 2018, in which trans women are included in the definition of women. This was challenged in a judicial review with the Scottish Government being found to have acted lawfully.

Hate Crime and Public Order (Scotland) Bill, and concerns that it could criminalise speech that some find offensive.

This time round, the Scottish Parliament manifestos of four of the five main parties (SNP, Scottish Liberal Democrats, Scottish Greens and Scottish Labour) referred to reform of gender recognition law. Scrutiny of reform proposals is therefore likely to loom large in the new session. So, what has happened on the reform of the GRA in Scotland?

What is the current law for gender recognition?

The GRA is UK wide, but is a devolved matter. It provides a way for trans people, aged 18 or older, to apply for legal recognition in their acquired gender. The Gender Recognition Panel makes decisions on the issuing gender recognition certifications (GRCs) and must be satisfied that the applicant:

has provided medical evidence of gender dysphoria

has been living in their acquired gender for two years.

The applicant must make a statutory declaration that they intend to continue to do so for the rest of their life.

There is no requirement under the GRA for an applicant to undergo surgery or hormone therapy.

Once someone has been successful in changing their gender they will be issued with a GRC and their legal sex changes.

To date, 5,583 people have legally changed their sex in the UK through the gender recognition process since 2005.

.png)

The Gender Identity Research and Education Society has estimated the trans population to be between 0.6% and 1% of the population, while the UK Government estimated the trans population to be between 0.35% and 1% (see Annexe E of the UK Government’s consultation on GRA reform).

What did the Scottish Government propose to change?

The Scottish Government first consulted on a review of the Gender Recognition Act 2004 in 2017.

Its view was that applicants for legal gender recognition should no longer need medical evidence or evidence living in their acquired gender for a defined period. In addition, the minimum age should be reduced to 16. It proposed to bring forward legislation to introduce a self-declaration system for legal gender recognition. The consultation also sought views on the recognition of non-binary people.

What did the responses say?

A consultation analysis was published in November 2018. There were 15,697 responses, 15,532 from the public and 165 from groups or organisations. A majority of respondents, around 60%, agreed with:

the proposal to introduce a self-declaratory system for legal gender recognition

the minimum age should be reduced to 16

the recognition of non-binary people.

Those in support of the proposal for a system of self-declaration of gender recognition made the following points:

Gender identity is a personal matter, and gender recognition is sought following thoughtful consideration by people who know their own mind.

The existing system can be complex, intrusive and distressing and act as a barrier to people who wish to change their gender.

Those not in favour frequently stated that:

It could pose a threat to safety in women only spaces (such as toilets, changing rooms, refuges and hospital wards), being open to abuse by men who wish to gain access.

It could undermine measures aimed at promoting female representation by allowing trans women to take up places on all-women short lists, on public boards, or awards.

Why was reform delayed?

On 20 June 2019, the Cabinet Secretary for Social Security and Older People made a statement in the Scottish Parliament. She said that despite support for reform, additional issues had been raised since the consultation, and sought to build consensus on the way forward.

Commitments were made to:

Develop guidance to support the collective realisation of both women’s and trans rights. This was due for publication summer 2020 but has been delayed by COVID-19 and reprioritisation.

Replace the LGBT Youth Scotland schools’ guidance for supporting transgender young people with guidance from the Scottish Government by the end of 2019. Due to the impact of COVID-19, this guidance will now be published “when all pupils have returned to school, or at the earliest opportunity in the new Parliamentary term”.

Establish a working group to address wider concerns about the disaggregation and use of data by sex and gender. The working group has published draft guidance for stakeholder feedback.

The Cabinet Secretary set out plans for a draft bill and announced it would not extend legal gender recognition to non-binary people at this stage. Instead, a working group would be established to identify other ways to improve equality for non-binary people. The work of the group was put on hold due to COVID-19, but was able to restart in February 2021.

Consultation on the draft Gender Recognition Reform Bill

The Scottish Government published its draft bill consultation on 17 December 2019, which ran until 17 March 2020. The proposals included:

Removing the requirement for people to apply to the UK Gender Recognition Panel. Instead, people seeking legal gender recognition would apply to the Registrar General for Scotland.

Removing the requirement to provide medical evidence.

Applicants must have lived in their acquired gender for a minimum of 3 months, and then confirm after a reflection period of 3 months that they wish to proceed.

Applicants would have to confirm that they intend to live permanently in their acquired gender.

Applicants would still be required to submit statutory declarations, made in front of a notary public or a justice of the peace.

It will be a criminal offence to make a false statutory declaration or false application.

Reducing the minimum age of application from 18 to 16.

Why was the draft Bill delayed?

On 1 April 2020 it was announced that the draft Bill, along with a number of other bills, would be delayed due to the impact of COVID-19. Around 17,000 responses have been received. The analysis has been impacted by COVID-19 and the intention is to publish it as ‘soon as practicable’ in the next Parliamentary session, if the administration is returned after the election.

Social Security: completing the (first) project

Camilla Kidner, Senior Researcher, Social Security

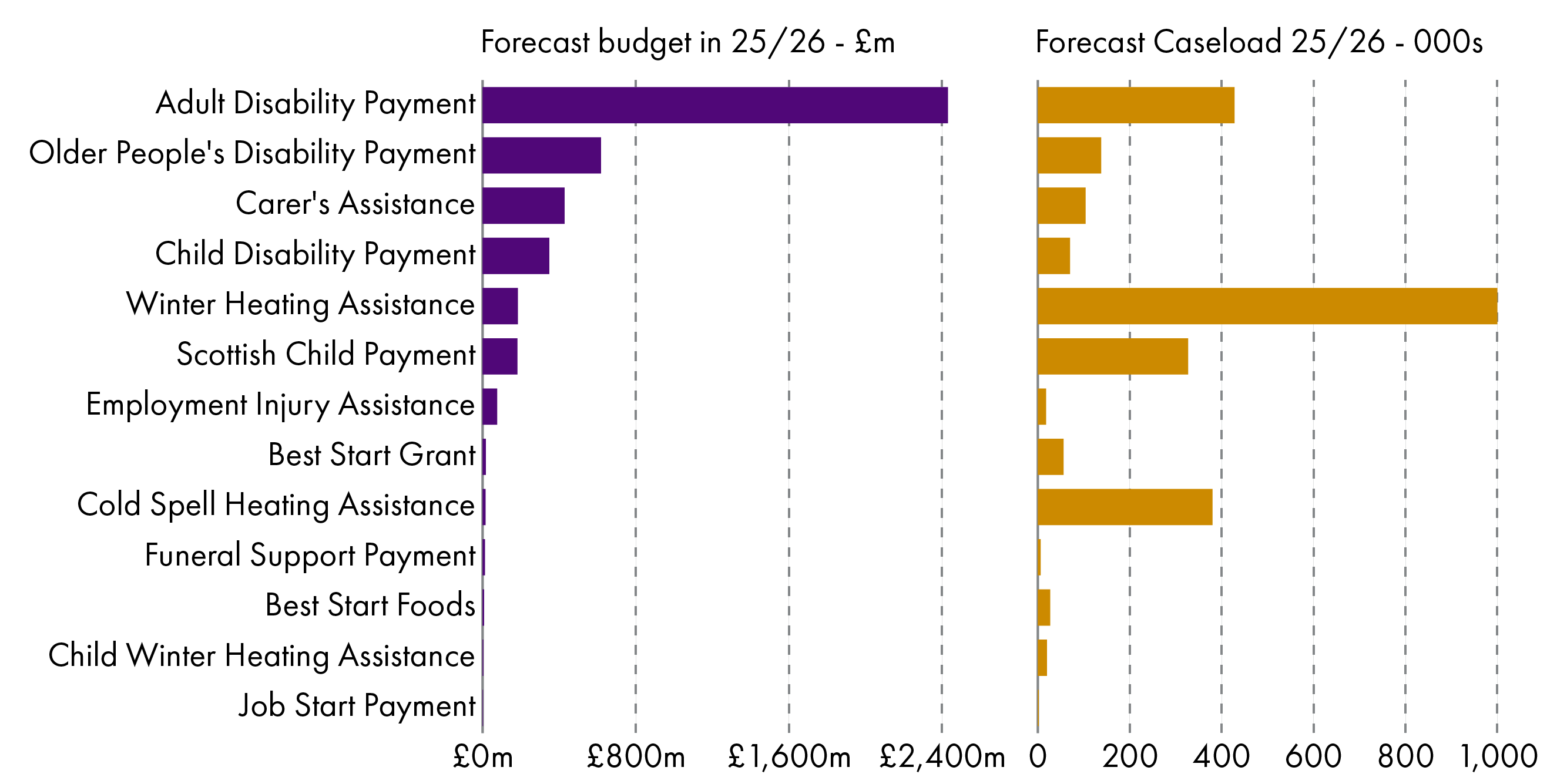

By 2025 the programme of social security devolution which started with the Scotland Act 2016 should be complete. This chapter takes a look at what has been done so far and what is still to do.

What has been devolved?

Most carer and disability benefits are devolved along with payments that were made through the social fund, such as funeral expense payments. The Scottish Parliament can create new benefits and top up most reserved benefits. In addition, Scottish Ministers have some, limited, powers over the way Universal Credit is paid.

What has been done so far?

The Social Security (Scotland) Act 2018 provides the framework for creating most Scottish benefits through regulations.

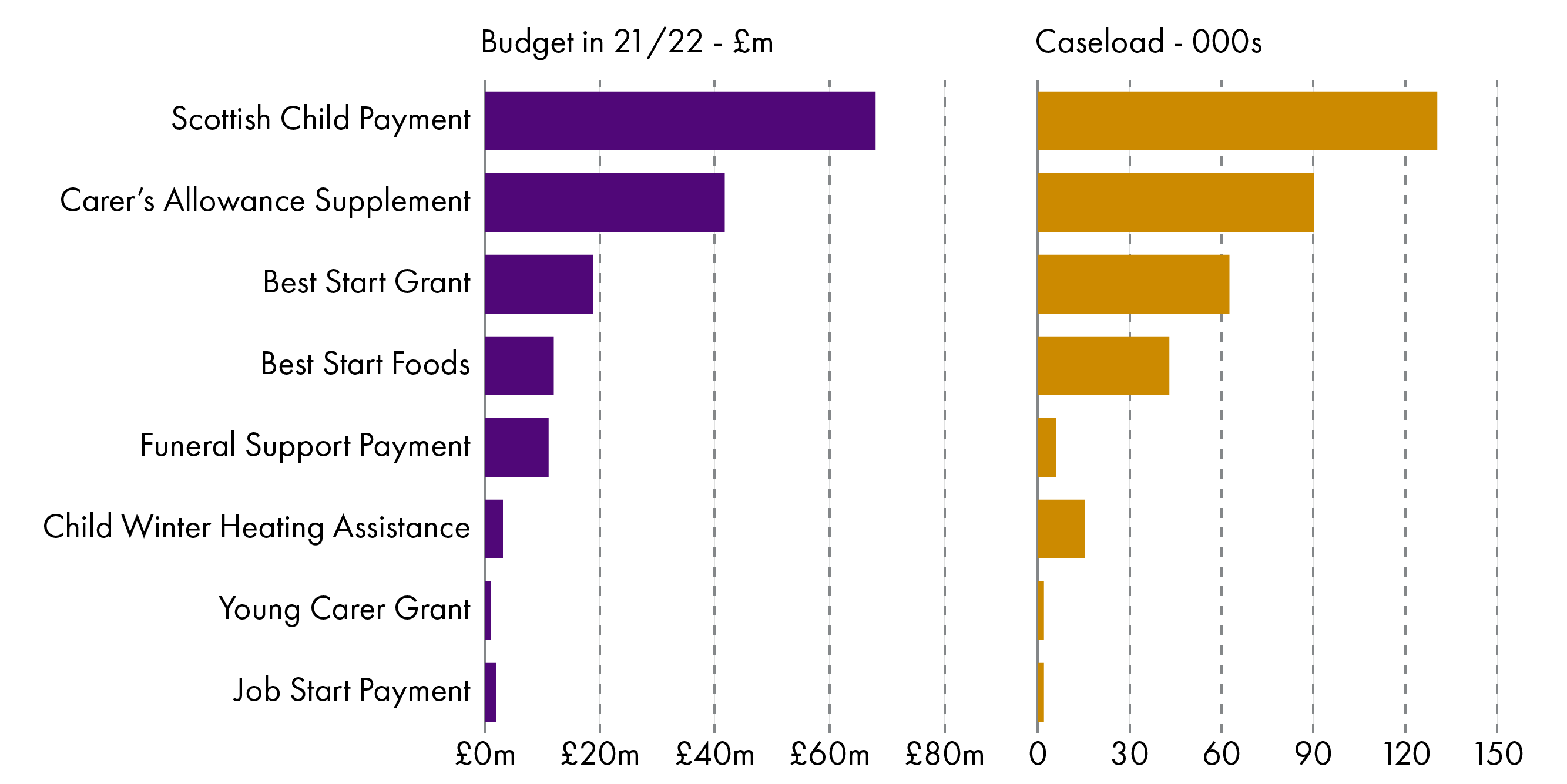

Social Security Scotland is an executive agency set up in 2018. It paid its first benefit – Carer’s Allowance Supplement – that autumn.

Also that year the Social Security Chamber of the First-tier tribunal service was created to hear appeals.

The Social Security Charter, published in January 2019, sets out what people can expect from Scottish social security.

The Scottish Commission for Social Security, established in February 2019, provides independent scrutiny of most social security regulations and the Charter.

In 2021, ‘top-up’ powers were used for the first time to create the Scottish Child Payment.

Throughout, the Scottish Government’s approach is ‘safe and secure transfer’ which means minimal policy differences compared to the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP). The DWP are still administering many benefits on the Scottish Government’s behalf until a Scottish ‘version’ of them can be developed.

So, while the Scottish Government has had financial responsibility for most carer and disability benefits since April 2020, almost all of that spending is still administered by DWP. This should change completely during Session 6.

By the time of the May 2021 election, Social Security Scotland directly administered around 350,000 cases across eight separate benefits with a combined value of around £160 million.

What still has to be done?

The really big devolved benefits (both in terms of caseload and spending) will transfer from the DWP to Social Security Scotland between summer 2021 and 2025. Progress has been delayed – most recently because of COVID-19. The timeline shows the dates known so far.

The regulations for Child Disability Payment were passed in March 2021. A pilot will start in July with national roll-out from November.

The consultation on the regulations for Adult Disability Payment closed in March. A pilot will start in spring 2022, with national roll-out that summer.

The Scottish Child Payment is due to be extended to under 16s by the end of 2022.

There are still substantial gaps in the timetable with no dates yet for the launch of Scottish ‘versions’ of:

Attendance Allowance

Carer’s Allowance

Industrial Injuries Disablement Benefits

Winter Heating Payment

Cold Weather Payment.

Each of these will need substantial regulations to be passed by the Scottish Parliament.

Despite the lack of a detailed timetable, the programme is due to complete by 2025, transforming the scale of Social Security Scotland – from dealing with around £160 million worth of benefits and around 350,000 cases in 2021 to dealing with over £4 billion worth of benefits for nearly two million people by 2025.

Scrutinising this large expansion in Social Security Scotland’s responsibilities and creating ‘Scottish versions’ of the remaining devolved benefits will therefore be key tasks for Session 6.

Doing things differently

The initial priority is ‘safe and secure transfer’. However once benefits are safely in place, there is scope to think about further changes. To this end, the Scottish Government has announced an independent review of Adult Disability Payment starting in 2023. The manifesto commitment to start working towards a Minimum Income Guarantee also provides scope for thinking more broadly about Scottish social security.

Budgetary risks: Adult Disability Payment

In 2022 Adult Disability Payment (ADP) will start to replace Personal Independence Payment (PIP). The rules will be almost the same, but the administration and assessment processes are intended to be very different. Because PIP/ADP is a big benefit, even a small policy change could have a large impact on the budget. The Scottish Fiscal Commission will produce costings. However, there could be a high level of uncertainty in costing new policy.

Social security and child poverty

The Scottish Child Payment (SCP) provides £10 per eligible child per week for families on low income benefits. The SNP manifesto includes a commitment to double this to £20 per eligible child per week over the course of Session 6.

The SCP is a key part of the strategy to meet statutory child poverty targets which include reducing relative child poverty to 18% by 2023-24. At the moment child poverty is rising gradually. In 2019-20, 26% of children were in relative poverty.

When it was announced in 2019, the SCP was intended to contribute a three percentage point reduction in relative child poverty.

In 2022 eligibility is due extend from children under six to children under 16. The then Cabinet Secretary expressed concern about whether the DWP would be able to provide data on which children were eligible in time to meet this deadline. In March she told the Scottish Affairs Committee that:

We do not have access to the data for Scottish Child Payment phase 2. We are still awaiting information and I think a level of co-operation that is required for me to feel comfortable that the DWP will work with us speedily enough to allow us to deliver on that.

The UK Minister told the Committee that:

for the older children, that data is not readily available. There is never a situation where we will not share data where we can.

A manifesto commitment to a ‘bridging’ payment to pupils claiming free school meals could capture around half of those entitled to the extended SCP. The SFC forecast 330,000 children aged 6 – 16 will be eligible for SCP, and the bridging payment is estimated to reach ‘up to 170,000’.

Therefore, a key issue for Session 6 will be how successfully SCP affects child poverty.

Conclusion

Session 5 saw the creation of Social Security Scotland, but it will be in Session 6 that it will develop into a truly large scale endeavour. It will become clear whether the agency has achieved ‘safe and secure transfer’ and treats people with ‘dignity and respect’. It is also in Session 6 that the Scottish Child Payment will be judged against the interim poverty targets. Finally, Session 6 offers the opportunity to think more broadly about whether and how Scottish social security ought to differ from DWP benefits.

Minor changes were made to this chapter on 17 May 2021.

A new human rights framework for Scotland

Nicki Georghiou, Senior Researcher, Equalities and Human Rights

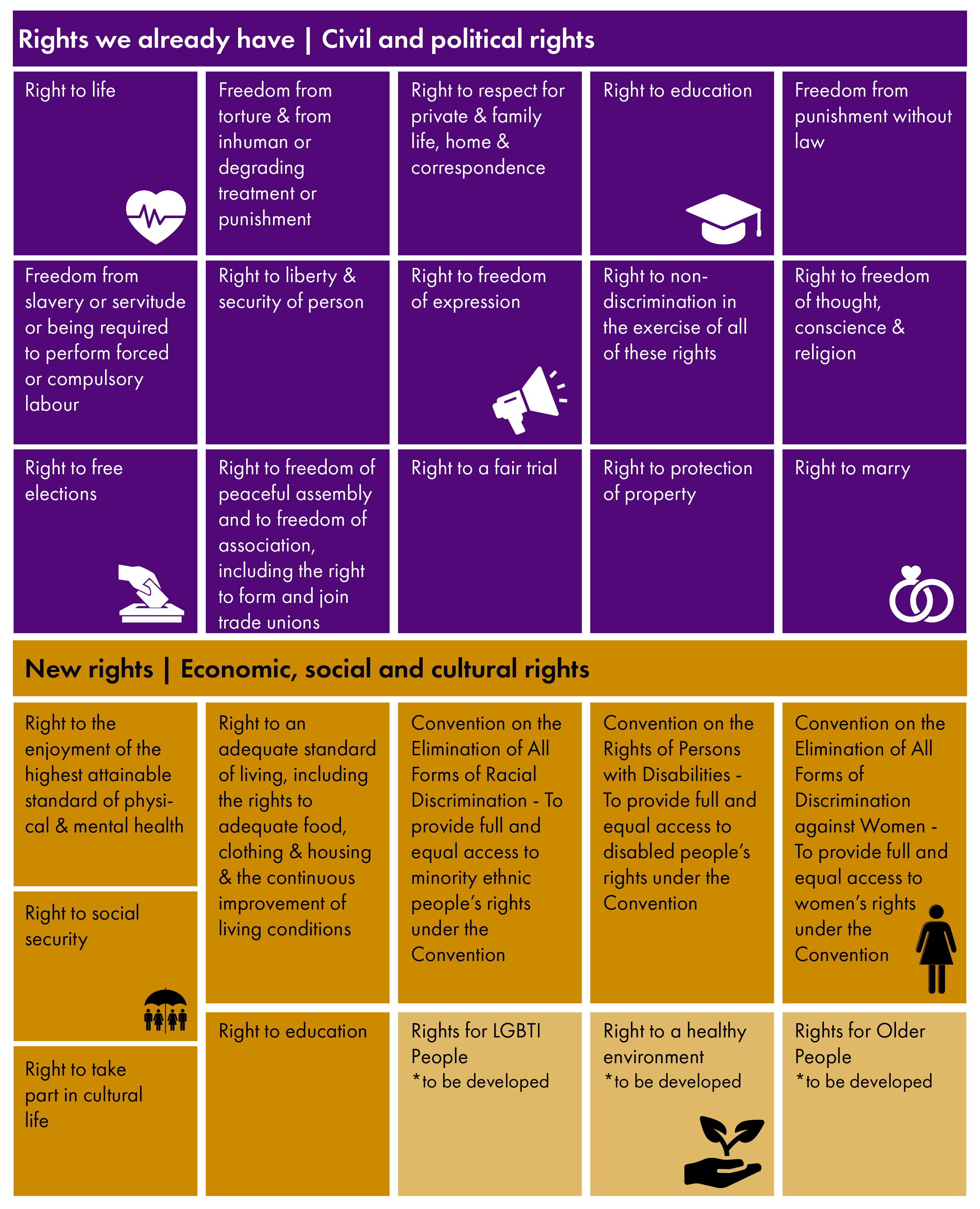

The previous Scottish Government announced on Friday 12 March that, subject to the outcome of the election, a new Human Rights Bill will be introduced in Session 6. The aim is to introduce a new human rights framework for Scotland. This is based on recommendations from the National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership.

The Bill will:

Re-state the rights in the Human Rights Act 1998 (HRA).

Incorporate rights of four United Nations Human Rights treaties into Scots Law, subject to devolved competence, on economic, social and cultural rights, women, disabled people and minority ethnic communities.

And include rights for:

older people

LGBTI people

a healthy environment.

There is no specific UN Treaty on these rights.

Ensuring people have rights sounds positive, but how does it differ from the rights we already have, and why does the Scottish Government think we need a new human rights framework? Why is it likely to be a key issue in the next session of the Parliament?

What rights do we have?

International Human Rights

The modern concept of human rights was developed in the aftermath of the Second World War. The Universal Declaration on Human Rights (UDHR), setting out basic rights and fundamental freedoms, was adopted in 1948 by the newly formed United Nations. It is generally agreed to be the foundation of international human rights law.

Later came the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1966), and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966).

‘Economic, social and cultural rights’ include, for example, the right to an adequate standard of living, the right to adequate food, and rights at work. For further background, see our SPICe briefing on this topic.

‘Civil and political rights’ include, for example, the right to life, freedom from torture, and freedom of expression.

After these UN treaties, there have been numerous international treaties for human rights protections, including those that the Scottish Government proposes to incorporate.

None of the UN treaties currently give individuals legal rights in UK courts. While the UK Government has pledged to make sure its domestic policies comply with the UN treaties, people normally can’t take public bodies to court if their treaty rights are breached in some way.

European Convention on Human Rights

The Council of Europe was formed in 1949. It was set up to promote democracy, human rights and the rule of law in Europe. The Council is separate from the European Union. The UK is one of 47 member states.

The Council adopted the European Convention on Human Rights in 1950, which protects a series of civil and political rights.

Human Rights Act 1998

The European Convention has a different status in UK law to other international human rights treaties. The HRA largely incorporates the rights in this Convention into domestic UK law, giving people rights that are directly enforceable in UK courts. It is unlawful for a public authority to act in a way that is incompatible with a Convention right.

Scotland Act 1998

The Scotland Act 1998 requires that all Scottish Parliament legislation must be compatible with the rights set out in the HRA. If a court finds that an Act of the Scottish Parliament is not compatible with the Convention, it has the power to ‘strike down’ the legislation. This is stronger than the HRA under which courts can issue a ‘declaration of incompatibility’ when it finds that an Act of the UK Parliament is not compatible with the Convention. For further background, see SPICe briefing on Human Rights in Scotland.

Why is this a key issue for session 6?

Impact of Brexit

Now that the UK has left the EU, the EU’s human rights framework (the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights) no longer applies to the UK. The Charter was described by the First Minister’s Advisory Group on Human Rights Leadership (the precursor to the National Taskforce) as one of two pillars of human rights protection in Scotland, the other being the HRA.

However, part of the approach of the proposed human rights framework is to keep “pace through monitoring and adapting future progressive rights developments within the EU, the Council of Europe and the broader international human rights framework”. This will be no small task.

Potential changes to the Human Rights Act

There have also been concerns over proposals by the UK Government to replace the HRA with a British Bill of Rights. This has never materialised. However, the UK Government has consulted on a review of the HRA. A report is due in Summer 2021.

The Scottish Government’s detailed response to the review said that it would “robustly oppose any attempt to weaken or undermine UK commitment to the Convention”, and that any change to the HRA should not be made without the consent of the Scottish Parliament.

Impact and recovery from Covid-19

The Equalities and Human Rights Committee has also identified the significant impacts of economic constraint and the Covid-19 pandemic on equalities and human rights.

How will the new rights work?

A key recommendation is that the Bill would provide access to justice when rights have been breached. What would be the impact for people who have been negatively impacted during the pandemic in terms of housing or access to health services for example? What would be the impact on public authorities with finite resources?

A complex bill

The Taskforce recommends the direct incorporation of four UN treaties and additional rights into one single bill. This builds on the approach used in the UNCRC Bill which incorporates children’s rights into Scots law. The subject matter of the four treaties is broad, including for example, economics, health, housing, culture, and rights for disabled people, women, and minority ethnic people. There will also be additional rights to consider for older people, LGBTI people, and the right to a healthy environment. This is likely to be a complex Bill which impacts on a wide range of policies.

UNCRC Bill and its reference to the Supreme Court

The UNCRC Bill was passed on 16 March. The Bill requires public authorities to comply with the UNCRC. It also gives rights holders the power to go to court to enforce their rights. This is a significant milestone as Scotland will be the first nation in the UK to incorporate the UNCRC.

However, on 24 March the Secretary of State for Scotland wrote to the Deputy First Minister expressing concerns that the Bill would affect the UK Parliament in its power to make laws for Scotland, “which would be contrary to the devolution settlement”. The UK Government has now referred the Bill to the UK Supreme Court for a ruling on this point. Of course, this will delay the Royal Assent of the Bill. If the Court finds that any provision is outside the legislative competence it cannot be submitted for Royal Assent in that unamended form. The Scottish Government could propose that the Bill be reconsidered, or that it be withdrawn, but the Parliament has to agree to do either of those things. The outcome of the case is also likely to have wider implications for the Scottish Government’s plans to incorporate UN human rights treaties into Scots Law.

Violence and harassment experienced by women

Frazer McCallum, Senior Researcher, Criminal Justice

The scale and impact of violence and harassment experienced by women and girls has been highlighted through the work and words of many people – sometimes inspired by the #MeToo movement.

The behaviour involved includes serious criminal offences as well as conduct which, although degrading and damaging, is not criminal.

Some figures from the most recent findings of the Scottish Crime and Justice Survey help to illustrate the scale of the problem. For example, when asked about their experience of various forms of violence and abuse since the age of 16:

21% of women had experienced ‘partner abuse’

6% of women had experienced ‘serious sexual assault’ (e.g. forced sexual activity)

16% of women had experienced ‘less serious sexual assault’ (e.g. unwanted sexual touching).

Wider experience of sexual harassment is explored in a blog by the Scottish Women’s Rights Centre. It notes:

Many women have become so desensitised to so-called ‘low level’ sexual harassment that they would not think to tell anyone about it.

Public attitudes to gender-based abuse are considered in the Scottish Social Attitudes Survey 2019: Attitudes to Violence against Women in Scotland.

In 2014 the Scottish Government and COSLA published Equally Safe: Scotland’s Strategy to Eradicate Violence against Women. It highlighted the need for a broad approach with a focus on prevention.

Although the issue is a wider one, the rest of this briefing focuses on the criminal justice system.

Even with this focus the picture is complex (e.g. including consideration of the approach of the police and prosecution). However, set out below is information on just three areas where debate over the case for further reform of criminal law and procedure is ongoing:

current and possible additional criminal offences

support and protection for complainers/victims in domestic abuse and sexual offence cases

the general requirement for corroboration, the use of juries and the not proven verdict.

The legal provisions outlined are also relevant for male complainers/victims.

Criminal offences

Recent legislation creating, or reforming relevant offences includes the:

Sexual Offences (Scotland) Act 2009 – consolidating much of the existing law on sexual offences as well as seeking to reform and clarify important areas

Abusive Behaviour and Sexual Harm (Scotland) Act 2016 – creating a new offence dealing with non-consensual sharing of intimate images (image-based sexual abuse or ‘revenge porn’)

Domestic Abuse (Scotland) Act 2018 – creating a new offence of domestic abuse against a partner or ex-partner.

In a blog reflecting on the first 12 months of the Domestic Abuse (Scotland) Act being in force, Scottish Women’s Aid referred to it as a “world-leading piece of legislation” but added that:

while we have no doubt that this law has been embraced at a national level, we are convinced that successful implementation is still far off.

Crime involving hatred or prejudice towards people because of their sex is not classed as a hate crime in the same way as crime linked to a range of other characteristics (e.g. race or religion). Whether sex should be treated in the same way as those other characteristics was debated during parliamentary scrutiny of what is now the Hate Crime and Public Order (Scotland) Act 2021.

The 2021 Act will allow the Scottish Government, using secondary legislation, to extend hate crime to cover the characteristic of sex. However, a decision on whether this should happen was put off until a Misogyny and Criminal Justice in Scotland Working Group has reported. As well as looking at hate crime, the Working Group is considering whether any weaknesses in the law should be dealt with by a new offence aimed specifically at tackling misogynistic behaviour.

Support and protection for complainers/victims

Recent examples of legislation seeking to support and protect complainers (or witnesses more generally) and victims include the:

Domestic Abuse (Scotland) Act 2018 – e.g. requiring a court to consider the future protection of the victim, and the possibility of making a non-harassment order, when sentencing an offender in a domestic abuse case.

Vulnerable Witnesses (Criminal Evidence) (Scotland) Act 2019 – e.g. seeking to facilitate greater use of pre-recorded evidence, thereby reducing the need for vulnerable witnesses to appear in court (not limited to domestic abuse and sexual offence cases).

In March 2021, the report of a cross-justice Review Group on Improving the Management of Sexual Offence Cases was published. Its recommendations include:

the creation of a specialist court, with trauma-informed procedures, for serious cases

a presumption in favour of pre-recording complainers’ evidence in serious cases

complainers having access to independent legal representation in objecting to questioning about their previous sexual history

complainers having a statutory right not to be identified in the media rather than relying upon current convention and agreement.

Corroboration, juries and verdicts

Does the general requirement for corroboration (i.e. evidence from more than one source), the use of juries in serious cases, or the availability of the not proven verdict sometimes act as a barrier to justice? That they can has been argued in a range of contexts, with the prosecution of serious sexual offences such as rape being a notable example.

On the other hand, they are seen by some as vital pillars of our criminal justice system – especially corroboration and the use of juries.

The Criminal Justice (Scotland) Bill (introduced 2013) included provisions seeking to abolish the general requirement for corroboration in criminal cases. However, concerns led to those provisions being removed during parliamentary scrutiny. Nevertheless, debate over the need for reform continues (e.g. see the campaigning group Speak Out Survivors).

Juries are not used in all criminal trials but are for more serious cases. There are concerns that the use of juries in some cases (e.g. rape trials) contributes towards low rates of conviction. The issue is examined in chapter 5 of the above-mentioned report on Improving the Management of Sexual Offence Cases. The report recommends that:

Consideration should be given to developing a time-limited pilot of single judge rape trials to ascertain their effectiveness and how they are perceived by complainers, accused and lawyers, and to enable the issues to be assessed in a practical rather than a theoretical way.

It notes that the Review Group was divided on the issue.

Separately from this, the possibility of a more general (although time-limited) use of judge-only trials in serious cases was considered as an option for reducing the backlog of cases resulting from COVID-19 restrictions. The option was not taken forward at the time.

Finally, turning to the not proven verdict; as things stand three verdicts are available in a criminal trial – guilty, not guilty and not proven. In legal terms, the implications of not proven are the same as not guilty in that the accused is acquitted.

Concerns about a possible over-use of the not proven verdict have been highlighted in some situations, including rape trials. The availability of the verdict has also been criticised more generally (e.g. on the basis that it is not well understood). There have been unsuccessful attempts in the past to dispense with the not proven verdict, including in the Criminal Verdicts (Scotland) Bill (which fell in 2016). However, wider political support for the possibility of its removal was expressed in the run-up to the 2021 Scottish Parliament election.

Further and Higher Education – How might the landscape change?

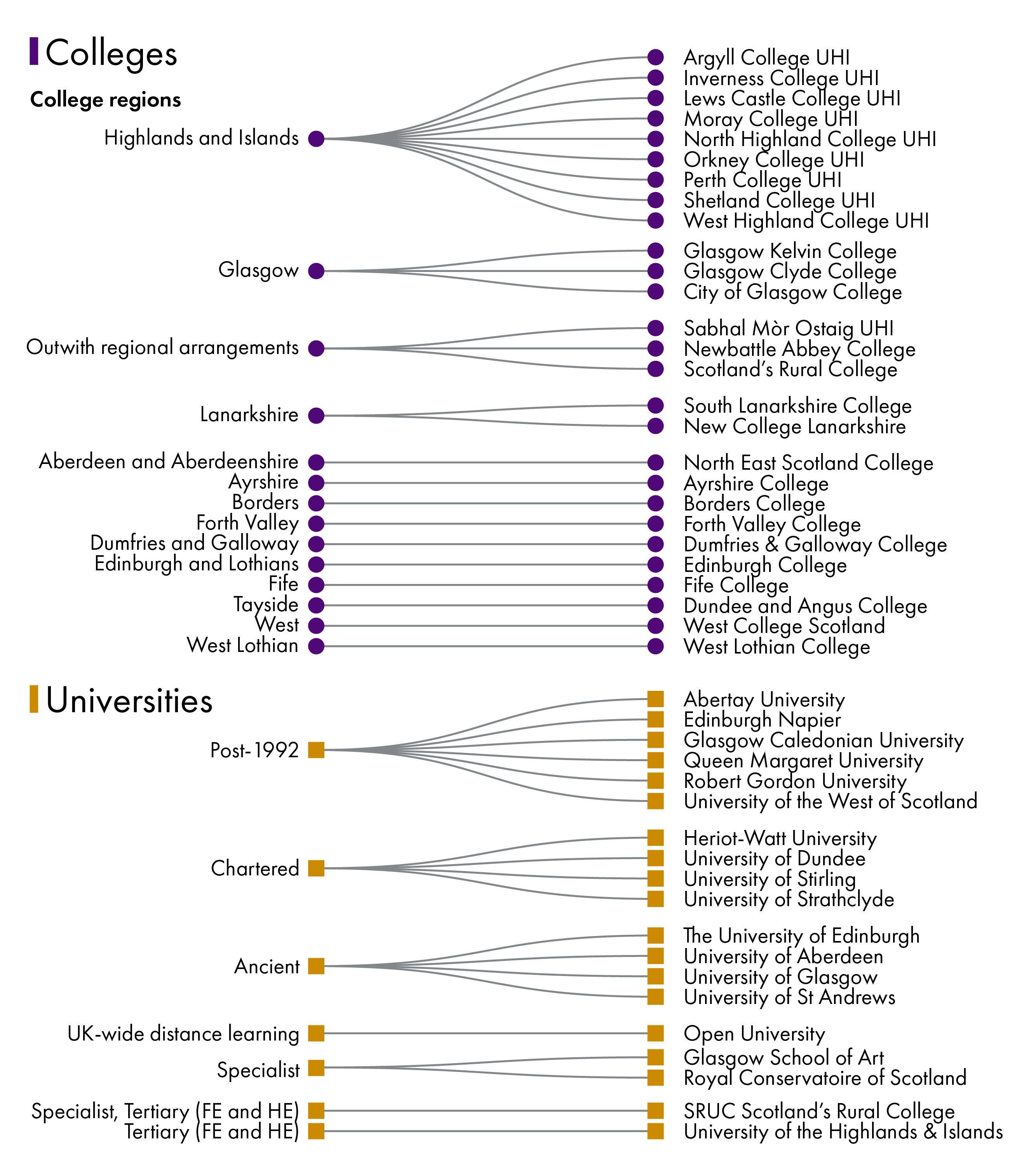

Lynne Currie, Senior Researcher, Further and Higher Education

2020 was a turbulent year for Scotland’s colleges and universities. The COVID-19 pandemic and resulting lockdown put the brakes on in-person teaching, caused significant issues for the delivery of assessment, and meant the Class of 2020 had a very different graduation to students in previous years. See our other chapters on the pandemic for wider information, for example on the road to recovery and the labour market.

There were also question marks around university income as a collapse in the number of international students was predicted.

Sustainability of funding is not a new issue, but it has certainly been exacerbated by the pandemic. Early projections of operating deficits between £384 - £500 million for academic year 2020-21 were later updated to deficits of £176.1 million.

In the year since the pandemic began, both sectors have adapted and found new ways for students to learn.

However, further change lies ahead: the Scottish Funding Council (SFC) is carrying out a review of the post-16 learning landscape. This will likely bring about transformation in the way learning is delivered by colleges and universities.

This briefing summarises the review so far and what might follow in Session 6.

Establishing a review

In June 2020, the then Minister for Further Education, Higher Education and Science Richard Lochhead asked SFC to carry out a review.

The “Review of Coherent Provision and Sustainability” is being carried out in three phases. Initial phase one considerations were published in October 2020; a phase two progress update was published in March 2021; and phase three will conclude in summer 2021.

Almost ten years on from the regionalisation of colleges, which saw existing colleges merged to create 13 college regions, further integration is on the horizon.

The pre-pandemic context

As well as looking at post-pandemic recovery, the SFC review also considers the recommendations of several recent reports. In particular, two reports published in the last two years have set the context. These are:

The One Tertiary System: Agile, Collaborative, Inclusive report. More often called the Cumberford-Little report, this recommends a rebalancing of college and university funding and making supporting business growth a top priority for the sector.

The Driving Innovation in Scotland – A National Mission report by University of Glasgow Principal Professor Sir Anton Muscatelli focused on universities’ role in driving innovation, calling for more collaborative working between institutions.

Phase 1 report: Everything on the table

SFC envisages a central role for universities and colleges in Scotland’s economic recovery from COVID-19. The Phase 1 report of the review set out the immediate focus for academic years 2020-22. Priorities include:

Retaining an emphasis on widening access to students from the least well-off backgrounds and promoting equality and social inclusion.

Support for students facing hardship, including mental health and wellbeing issues.

Funding additional student places resulting from the Deputy First Minister’s decision to reverse downgraded SQA results and revert to teacher-estimated grades.

Protecting Scotland’s research and science base and securing Scottish interests in UK-wide approaches such as job retention, research and development (R&D), post-Brexit and international strategies.

Focusing capital funding on developing digital and blended learning and safe campuses.

Emerging themes for 2022 and beyond were identified from the Phase 1 consultation:

Keeping the interests of students and equalities at the heart of everything.

Supporting the “digital revolution” for learners by developing remote learning and ensuring students have the options of online and in-person learning post-COVID-19.

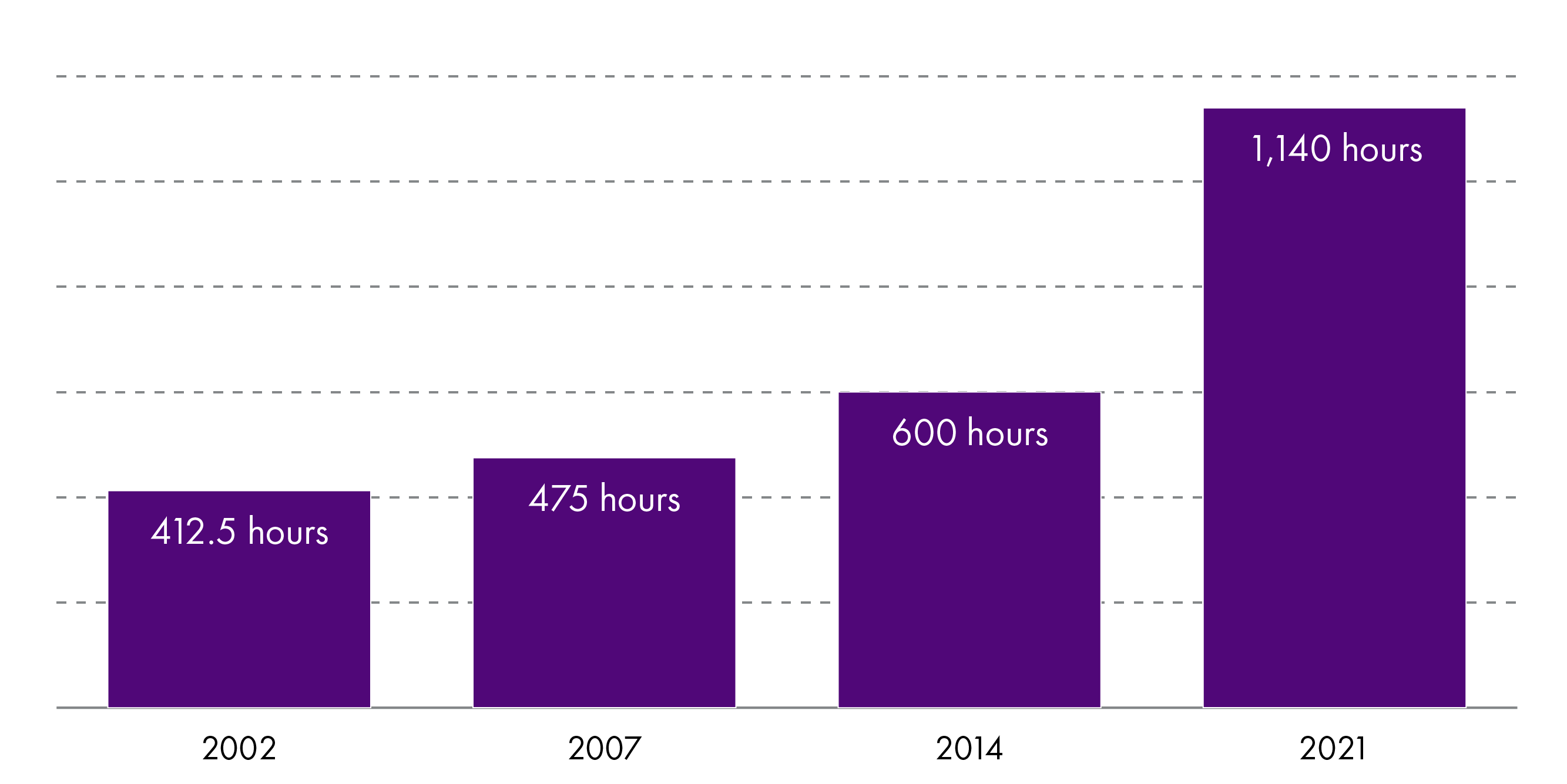

Moving toward a joined-up further and higher education and skills system – known as a tertiary education - offering clearer course choices to learners and collaboration opportunities for institutions.

Recognising the importance of colleges and universities as national assets.