Civil Partnership (Scotland) Bill

The aim of the Civil Partnership (Scotland) Bill is to allow different sex couples to form civil partnerships. Just as marriage and civil partnership are open to same sex couples, it will mean that marriage and civil partnership are open to different sex couples.

Executive Summary

The aim of the Civil Partnership (Scotland) Bill is to introduce civil partnerships for different sex couples.

Currently, different sex couples in Scotland only have the option of getting married if they wish to have their relationship legally recognised. Same sex couples have the choice of getting married or forming a civil partnership.

Civil partnerships for different sex couples have recently been introduced in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

This followed a ruling by the Supreme Court that said that the situation was discriminatory and incompatible with the European Convention on Human Rights.

The inequality could be eliminated either by abolishing civil partnerships or by extending them to different sex couples.

The Scottish Government aims to extend civil partnerships to different sex couples to uphold human rights and equality of opportunity. This will also provide parity with the rest of the UK.

The Bill will make changes to existing legislation to allow for different sex couples to form civil partnerships. This includes consequential changes to Scottish family law, and allows for the recognition of certain overseas relationships between different sex couples.

The Scottish Government has run two consultations on different sex civil partnerships.

Those in favour of different sex civil partnerships refer to the need for equality; wanting greater legal and financial protections; that marriage is old fashioned and patriarchal; and that it might promote family stability for unmarried different sex couples with children.

Those against different sex civil partnerships suggest that it is not necessary because it is very similar to marriage; that cohabiting couples in Scotland already benefit from many rights; and that demand would be low.

Recent public opinion research shows that there is substantial public support for different sex civil partnerships, with 65% of people in favour.

Based on the international experience, the Scottish Government estimates there could be 109 different sex civil partnerships registered each year.

It is currently possible for couples to change a same sex civil partnership to a same sex marriage. The Bill provides for couples in a different sex civil partnership to change it to a marriage if they wish. There are no plans to allow married couples to change their relationship to a civil partnership.

However, the UK Government is considering whether to allow the possibility of converting marriage to a civil partnership in the future.

Introduction

The Civil Partnership (Scotland) Bill was introduced on 30 September 2019, by Shirley-Anne Somerville MSP, the Cabinet Secretary for Social Security and Older People.

The aim of the Bill is to introduce civil partnerships for different sex couples. The Scottish Government states1 that it:

...aims to create an inclusive Scotland which protects, respects, promotes and implements internationally recognised human rights. In line with this, the policy of the Bill is aimed at upholding human rights and providing equality of opportunity for couples who decide they wish to enter into a legally recognised relationship. In line with this, the key principles behind the Bill are promotion of:

Equality of opportunity

Human rights.

This Bill follows a Supreme Court ruling on 27 June 2018 that the inability of different sex couples to form a civil partnership is in breach of the European Convention on Human Rights because same sex couples have the choice to marry or form a civil partnership, but different sex couples do not.2

The case was brought by an English couple who had ideological objections to marriage. While there is little legal difference between marriage and civil partnerships, the Equal Civil Partnership campaign state that:

...history, expectations, and cultural baggage of the two institutions is very different. Many couples can make a marriage work, but for some people – especially women – marriage is seen as carrying far too much patriarchal baggage.

If the Bill is passed, it is likely that different sex civil partnership will be available in Scotland around spring 2021. This allows for the set up of the system, and for consequential changes that will need to be made to reserved legislation.

Terminology

This briefing uses the term 'different sex' couples, instead of 'opposite sex' or 'mixed sex'. This is in line with the terminology in the Bill, although the accompanying documents use the term 'mixed sex'. However, 'opposite sex' or 'mixed sex' may be used when quoting from UK or Scottish Government documents.

Background

History of marriage and civil partnership in Scotland

Until fairly recent times, marriage was understood to be between different sex couples. Indeed, the Marriage (Scotland) Act 1977 listed being of the same sex as an impediment to marriage.

This view began to shift as attitudes towards same sex relationships changed1 and there were calls for same sex couples to be able to register their partnerships with the same rights and responsibilities as marriage.2

Civil partnerships for same sex couples were introduced across the UK by the Civil Partnership Act 2004. The 2004 Act created a legal union for same sex couples that was similar to marriage. As a result, same sex couples across the UK were able to form civil partnerships with rights and responsibilities similar to those of marriage. At the time, there was no desire from either the UK or Scottish Government to open up marriage to same sex couples, or to allow civil partnerships for different sex couples. The Scottish Executive said in 2003 that it did not "seek to undermine marriage by extending civil partnership registration to cohabiting couples".3

The 2004 Act was structured in separate parts for England and Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. This was to ensure that each administration replicated, as far as possible, their existing rules of marriage.4 The Scottish Executive endorsed a UK approach for the 2004 Act through a Sewel Motion, ensuring that the Scottish provisions were based on Scots law. It did this for two main reasons:5

The creation of civil partnerships would bring rights and responsibilities that relate to reserved matters, such as immigration, benefits and pensions.

To avoid cross-border issues where a couple might have certain rights in England, but not in Scotland.

The first civil partnerships in Scotland were formed in December 2005.

Following the 2004 Act, attitudes and opinion towards same sex relationships continued to change, with support growing for same sex marriage.6 Some people argued that it was discriminatory to have separate provisions for same sex and different sex couples.7

The Marriage and Civil Partnership (Scotland) Act 2014 introduced marriage for same sex couples. The first changes of civil partnerships to marriages took place on 16 December 2014, whereas the first same sex marriage ceremonies took place on 31 December 2014.8

The 2014 Act also made changes to the 2004 Act, by permitting civil partnership registrations to take place in religious premises.7

Supreme Court Judgment

Steinfeld and Keiden case

The Civil Partnership 2004 Act was challenged by Rebecca Steinfeld and Charles Keidan; a long-term couple, who wished to enter a legally recognised relationship, but had ideological objections to marriage.

The Supreme Court judgment accepted that, before the UK’s Marriage (Same Sex Couples) Act 2013 came into force, which introduced same sex marriage in England and Wales, there was no discrimination against same sex or different sex couples. 1However, it stressed that the discrimination began when the 2013 Act came into effect. This meant that same sex couples had two ways to have their relationship registered, whereas different sex couples only had one. Lord Kerr stated:2

I should make it unequivocally clear that the government had to eliminate the inequality of treatment immediately. This could have been done either by abolishing civil partnerships or by instantaneously extending them to different sex couples.

What did this mean for Scotland?

The judgment did not refer to Scotland. However, the same situation persists, that same sex couples have two choices to register their relationship, and different sex couples only one.

In the Ministerial foreword to the most recent Scottish Government consultation on the future of civil partnerships, Shirley-Anne Somerville, the Cabinet Secretary for Social Security and Older People said:3

The recent decision by the UK Supreme Court in a judicial review in England and Wales means that the Scottish Government is required now to consider the future of civil partnership in Scotland.

The Supreme Court made it clear that the Civil Partnership Act 2004 is not compatible with the European Convention on Human Rights as civil partnership is open to same sex couples only whereas marriage is open to both opposite sex couples and same sex couples. The judgment of the Supreme Court relates specifically to England and Wales but the facts and circumstances in Scotland are very similar.

A consultation on the future of civil partnerships in Scotland was held between 28 September and 21 December 2018.3

England, Wales and Northern Ireland

England and Wales

Civil partnerships for different sex couples were recently introduced in England and Wales, via the Civil Partnership (Opposite-sex Couples) Regulations 2019, under Section 2 of the Civil Partnerships, Marriages and Deaths (Registration etc) Act 2019.

This legislation was introduced by Tim Loughton MP as a Private Member's Bill. The passage of the Bill overlapped with the Supreme Court judgment. On 2 October 2018, the then Prime Minister, Theresa May, announced that the UK Government would change the law to allow different sex couples in England and Wales to enter into a civil partnership.1 The UK Government had planned to introduce its own legislation in the next session of the Parliament. However, the UK Government later supported the Bill after making amendments. 1 The first different sex civil partnerships in England and Wales took place on 31 December 2019.3

Northern Ireland

Until January 2020, only different sex couples could marry in Northern Ireland, and only same sex couples could register a civil partnership.

In July 2019, UK MPs voted to require the UK Government to introduce different sex civil partnerships, same sex marriage, and to change abortion laws in Northern Ireland, but only if devolution was not restored on or before 21 October 2019i. The Northern Ireland (Executive Formation etc) Act 2019 came into force on 22 October 2019, requiring the Secretary of State to make regulations, to come into force on or before 13 January 2020, to allow different sex couples to form civil partnerships.56

The Marriage (Same-sex Couples) and Civil Partnership (Opposite-sex Couples) (Northern Ireland) Regulations 2019 came into force on 13 January 2020. The first different sex civil partnerships can take place from February 2020. 7

Cohabitation

In Scotland, cohabitants have some rights, but these are fewer and less clear than rights for married couples or civil partners. Cohabitants are defined in the Family Law (Scotland) Act 2006 as a couple, same sex or different sex, who live together as if married. The 2006 Act made provisions for cohabitants, dependent on the length and nature of their relationship, and of any financial arrangements:1

A presumption of an equal share in household goods bought during the time the couple lived together.

An equal share in money derived from an allowance made by one or other of the couple for household expenses and/or any property bought out of that money.

On separation, a right in certain circumstances to ask the court to make an order for financial provision against the other former cohabitant.

A right to apply to the court for an order for money or property from the estate if a cohabitant dies without leaving a will.

The right to apply to court for a “domestic interdict” in domestic abuse cases. Such orders could, for example, restrain or prohibit conduct of a person towards the applicant or any child in the care of the applicant.

The Scottish Law Commission announced a review of the cohabitation provisions under the 2006 Act in February 2018. A discussion paper is due to be published soon, followed by a report on the law relating to cohabitants in 2021.

How do civil partnerships and marriage differ?

This section explains the main differences between civil partnership and marriage.

Eligibility

Eligibility for marriage and civil partnership are the same, but for civil partnership the couple must be of the same sex. Both parties must be at least 16, not already in a marriage or civil partnership, not too closely related, and understand the nature of civil partnership or marriage.

Ceremony

Marriages are created through a marriage ceremony, while civil partnerships are created through registration.

When first introduced, civil partnerships could only be registered by civil registrars. This was later amended and there are now several ways for a religious or belief celebrant to be authorised to register civil partnerships.1

The Bill will replicate this for different sex civil partnerships. While the number of same sex religious or belief civil partnerships is low, the Scottish Government suggests it could be higher for different sex couples. This is based on the knowledge that there are more different sex couples in society than same sex couples.1

Both marriage and civil partnership ceremonies can be religious or belief, or civil:

A religious or belief marriage ceremony can be held anywhere, but must be solemnised by a minister, pastor, priest or other person approved under the Marriage (Scotland) Act 1977.

Civil marriage ceremonies can take place at a registration office, or at a place other than religious premises, that has been agreed between the couple and registration authority.

Civil partnerships can be registered by a registrar or by an authorised celebrant.

Couples must give notice to the local registrar of their marriage or civil partnership and pay a fee.

Similarities

When a civil partnership ends through dissolution or death, a set of legal consequences flow, in a similar way to a marriage:1

Rights of succession (inheritance) on the death of one of the parties to a civil partnership.

Right to occupy the family home that may take precedence over the rights of a purchaser, the holder of a standard security (mortgage) or the party named in the tenancy agreement.

Aliment obligations - this is an obligation on spouses and civil partners to maintain each other and any children they may have.

Financial provision on dissolution.

Differences

There are few significant differences between a marriage and a civil partnership.

With regard to survivor benefits, some pension schemes have offered lower benefits for some surviving civil partners when compared to some surviving spouses.1

Most issues in relation to pensions are reserved, but the Scottish Government has devolved responsibility for some public sector pension schemes, for example in local government and the NHS. The Scottish Government has said that survivor benefits in devolved public sector schemes for different sex civil partners would be aligned with the rules for survivor benefits for same sex civil partners and same sex spouses when different sex civil partnerships are introduced. 5

Adultery - sexual intercourse with someone of a different sex outside of the marriage - is a ground for divorce in marriage, whether a different sex or same sex marriage. It is not a ground for dissolution in a civil partnership. This is discussed further below, but the Scottish Government does not plan to add adultery to the law of dissolution of civil partnership. The reasoning is that adultery has been part of divorce law due to a number of religious bodies and people of faith being of the view that it should be a reason for ending a marriage.

Statistics on marriage and civil partnership

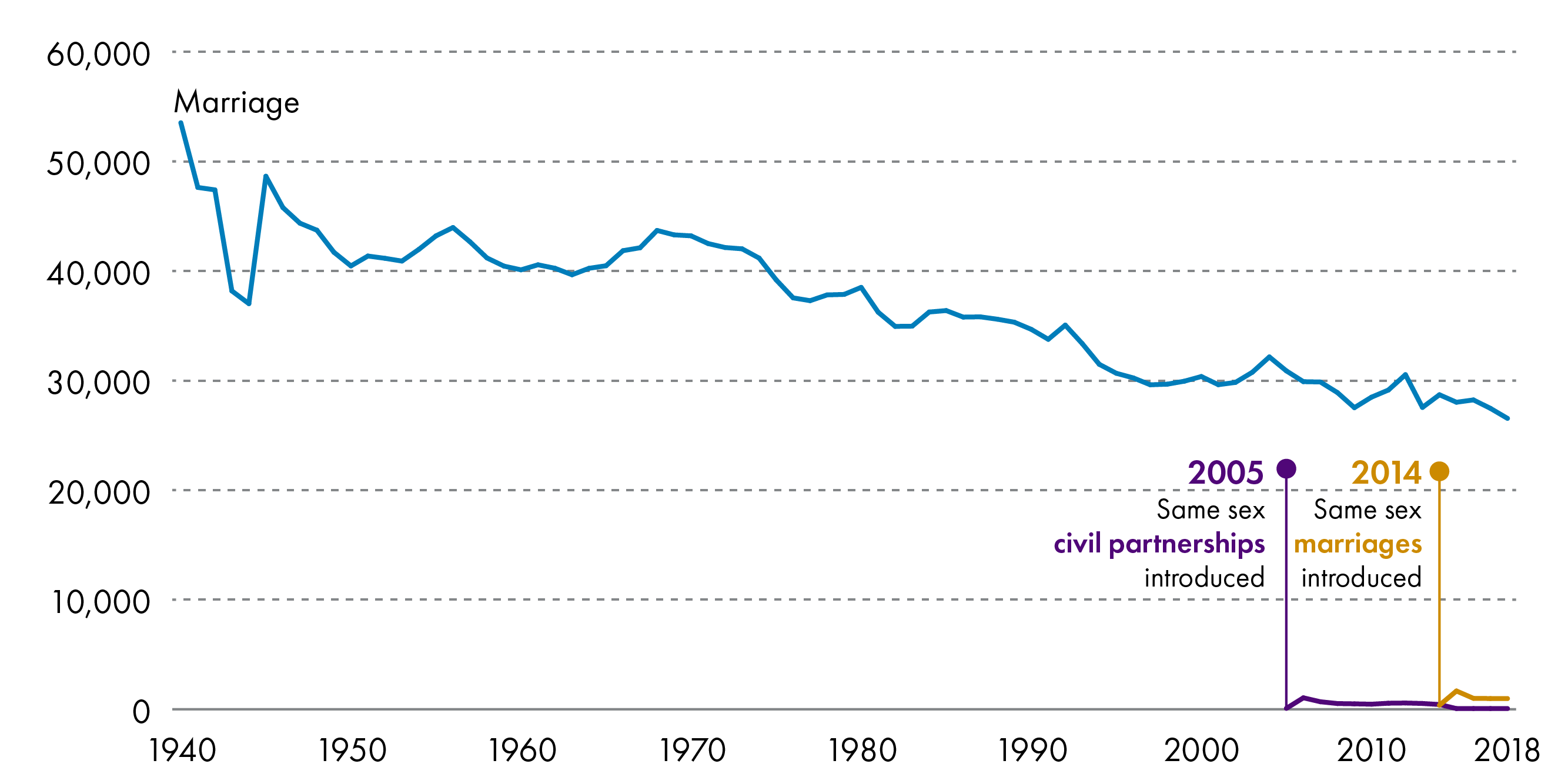

Figures from the National Records of Scotland (NRS) show that, over time, the number of people getting married has reduced over time.1

Same sex civil partnerships and marriages, make up a small number of registered relationships, compared with different sex marriage, as can be seen in the chart below.

The table below shows the number of marriages and civil partnerships entered into each year in Scotland, since civil partnerships were introduced. There was an initial surge in civil partnerships when they were first introduced. When same sex marriage was introduced, this was the preferred option of same sex couples choosing to register their relationship.

| Year | Civil Partnerships | Same sex marriages |

|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 84 | - |

| 2006 | 1047 | - |

| 2007 | 688 | - |

| 2008 | 525 | - |

| 2009 | 498 | - |

| 2010 | 465 | - |

| 2011 | 554 | - |

| 2012 | 574 | - |

| 2013 | 530 | - |

| 2014 | 436 | 367 |

| 2015 | 64 | 1671 |

| 2016 | 70 | 998 |

| 2017 | 70 | 982 |

| 2018 | 65 | 979 |

National Records of Scotland - Time Series Data1

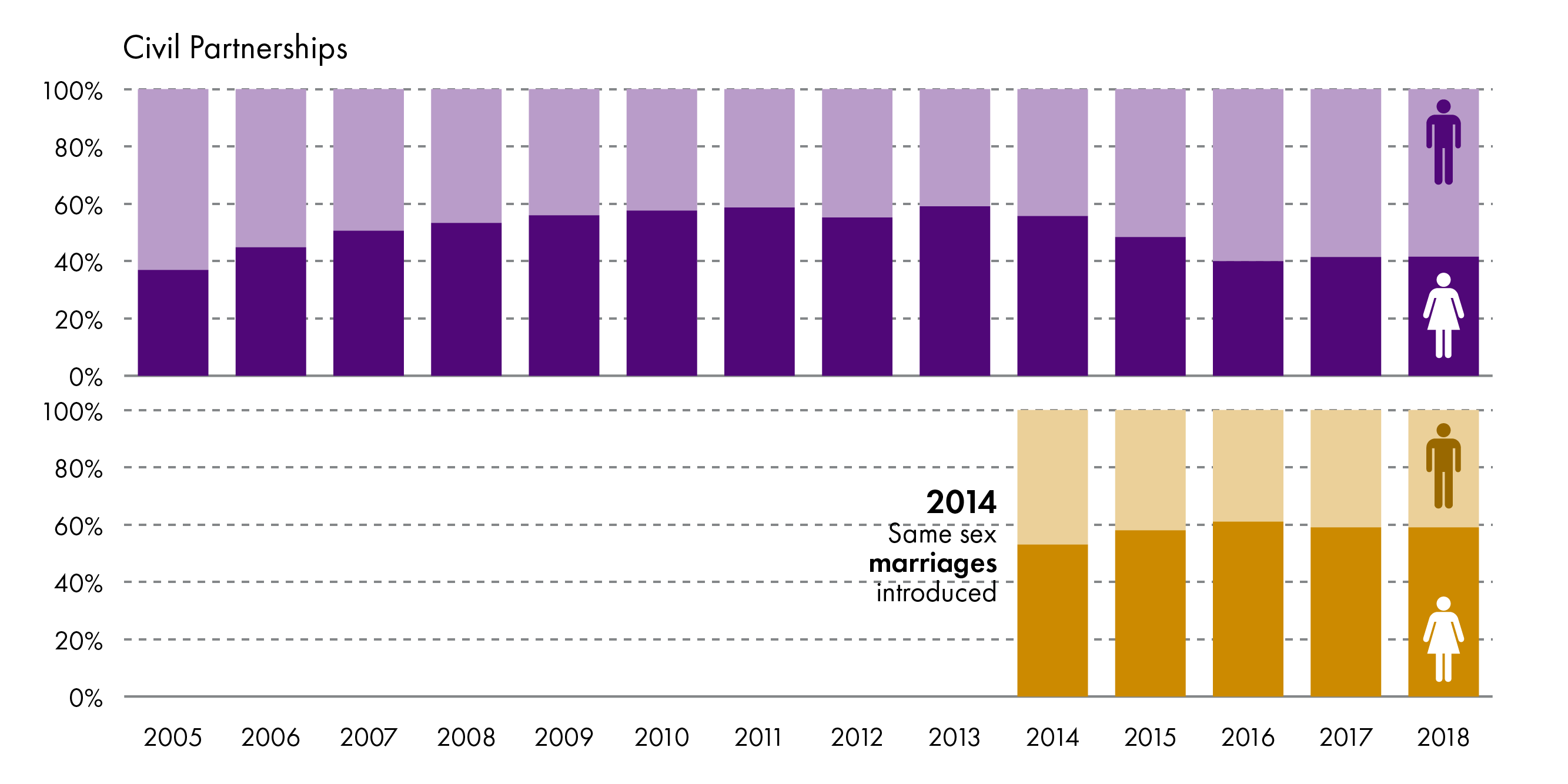

The statistics also show that female couples tend to favour marriage as an option, and male couples tend to favour civil partnership, as can be seen in the following chart.

This pattern is similar to other jurisdictions in that, where both marriage and civil partnership are available to same sex couples, most couples will opt for marriage.10

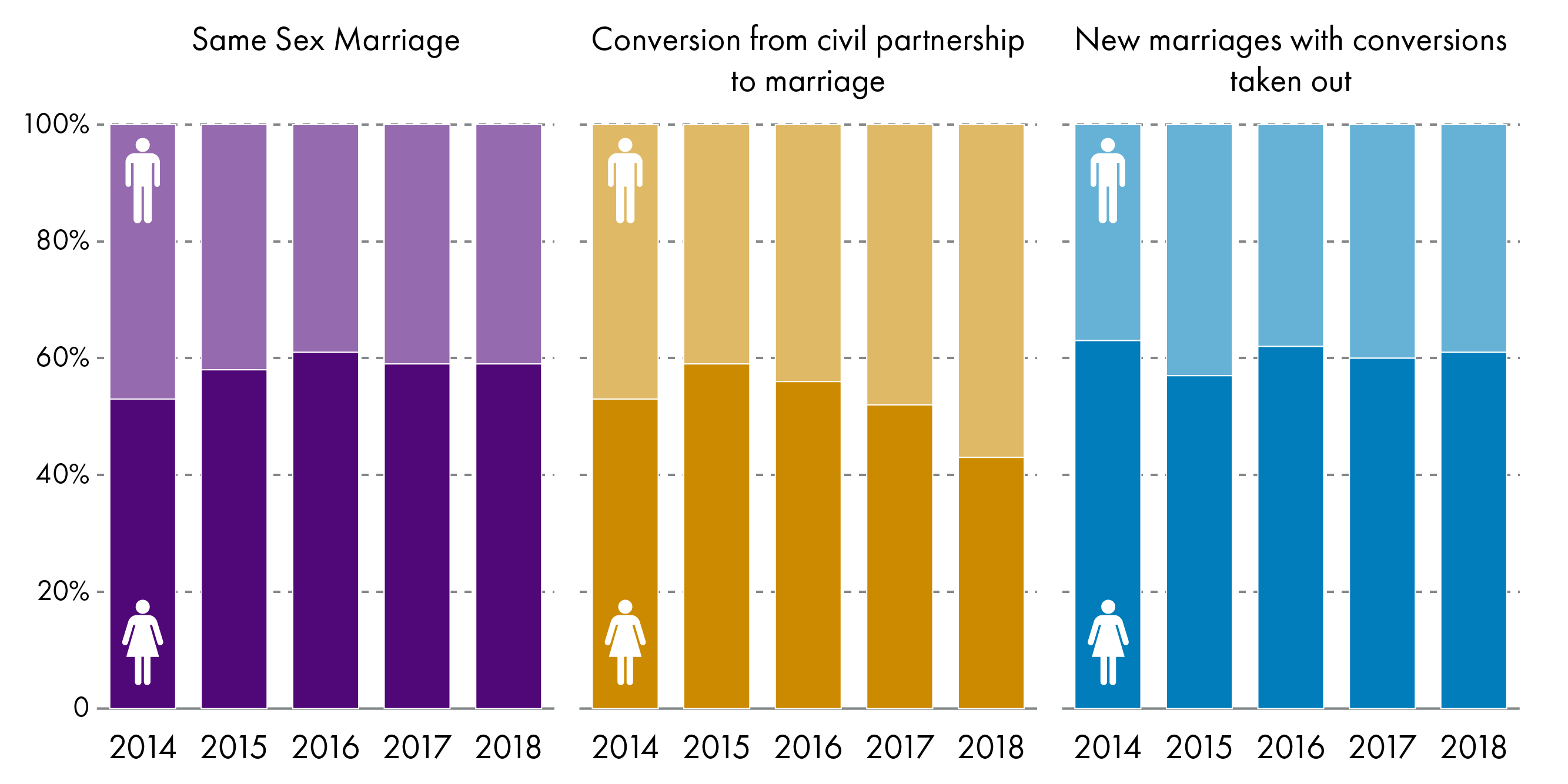

A proportion of the same sex marriages were changed from civil partnerships, which the 2014 Act allowed them to do from 16 December 2014, as the table below shows.11 There was an initial surge when this was introduced, but this has since tailed off.

| Year | Same sex marriage | Changed from a civil partnership | Newly registered same sex marriage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 367 | 359 | 8 |

| 2015 | 1671 | 936 | 735 |

| 2016 | 998 | 173 | 825 |

| 2017 | 982 | 127 | 855 |

| 2018 | 979 | 88 | 891 |

National Records of Scotland - Vital Events reference tables on marriage and civil partnership87654

The chart below shows the proportion of male and female couples who chose to change their civil partnership to a marriage. Overall it shows that female couples have been more likely to change from a civil partnership to a marriage, except for 2018.

International comparisons on legal unions

Other countries and jurisdictions have developed legal unions for couples as an alternative to marriage. These can be to provide a legal relationship for same sex couples, but also as a way to ensure that co-habiting different sex couples have rights. It has been about pursuing equality, but also about providing protection for couples in case of relationship breakdown, or when a partner dies. The terms used for these legal unions include 'civil union', 'domestic partnership' or 'registered partnership'.

Denmark, Sweden, Norway and Iceland were among the first countries to introduce an alternative to marriage, exclusively for same sex couples. They later introduced same sex marriage, despite there not being a substantive difference between marriage and registered partnerships. At the same time, they each abolished registered partnership so that no new registered partnerships could be made. Similarly, the Republic of Ireland, Finland and Germany abolished future same sex civil partnerships when same sex marriage was introduced; existing civil partnerships could be retained. 12

In the Netherlands and France, registered partnerships were created for both same sex and different sex couples. While in the Netherlands registered partnerships are almost identical to marriage, in France they are fundamentally, and deliberately, different to marriage. Later, both countries introduced same sex marriage, but in contrast to the countries above, registered partnerships were retained.2

Scotland, (and until very recently England and Wales), is the only country in the world where same sex couples can choose between a marriage or a civil partnership, while different sex couples only have the option of marriage.

Other countries have opened up registered partnerships to a wider range of relationships. In Belgium, the scheme of legal cohabitation was opened up to any two persons and can include siblings or a parent and child. In some Australian states, couples and non-conjugal relationships, often referred to as 'caring relationships', were able to obtain legal recognition. New Zealand introduced registered partnerships that were almost identical to marriage for same sex and different sex couples, and later opened up marriage to same sex couples. It retained registered partnerships, but also introduced a scheme for cohabitants living as couples that after three years places these couples on the same legal footing as couples in a marriage or registered partnership.2

There are no plans to extend civil partnership in Scotland to other relationships. Forbidden degrees of relationship are set out in Schedule 10 to the 2004 Act.5 These mirror those that apply to marriage, and include: parent, child, grandparent, grandchild, sibling, aunt or uncle, niece or nephew.

Views on different sex civil partnership

The Scottish Government has held two consultations on extending civil partnerships to different sex couples. This section summarises the views received, including responses to a public attitudes survey.

Consultations

During the passage of the Marriage and Civil Partnership (Scotland) Act 2014, the Scottish Government committed to a review of the future of civil partnerships; whether to close future civil partnerships in light of the fact that same sex and different sex couples would be able to get married, or to open up civil partnerships to different sex couples.1

A consultation was run between 22 September and 15 December 2015.2 The consultation sought views on three options:

no change

no new civil partnerships after a certain date in the future, or

introducing opposite sex civil partnership.

However, the Scottish Government stated at the outset that it was "not persuaded that opposite sex civil partnership should be introduced in Scotland." The reasons for this were that "demand would be low; there would be costs; and opposite sex couples seeking to enter into a registered relationship have the option of marrying."

The consultation received 411 responses, with the vast majority (93%) submitted by individual members of the public.

Following the Supreme Court judgment in June 2018, in September 2018, the Scottish Government launched a further consultation to gain fresh insight on the future of civil partnerships (closed 21 December 2018).3 This time, two options were set out:

no new civil partnerships after a certain date in the future, or

introducing opposite sex civil partnerships.

Either of these options would be effective in removing the incompatibility with the European Convention on Human Rights with current law.

There were 481 responses to the second consultation, with the vast majority (96%) from individuals.

No change option

The introduction of this Bill shows that the Scottish Government has moved on from the 'no change' position. However, the original consultation from 2015 sought views on not changing the law, so keeping the option of civil partnership or marriage for same-sex couples, and the option of marriage for different sex couples.

The Scottish Government made the argument that it might be preferable to wait five years from the introduction of same sex marriage, before making any further changes to the law on marriage and civil partnership. This position had support, given that it would allow time to gather evidence on demand for future same sex and different sex civil partnership.4

The Scottish Government said that the case against no change was that there would continue to be an imbalance between same sex and opposite sex couples, and that there would continue to be a separate and distinct status for same sex couples. Those supporting this point said that the imbalance is discriminatory. It was also highlighted that the majority of jurisdictions that have same sex marriage, either offer civil partnerships to both same sex and different sex couples, or neither.4

No new civil partnerships after a certain date in the future

This option would mean that no new civil partnerships could be entered into in Scotland after a certain date. Existing civil partners could stay in their partnerships, and the civil partnerships would continue to be recognised in Scotland.

The Scottish Government argued, in 2015, that this option would reduce complexity, remove a separate status for same sex couples, and that it was more likely that a couple would have their marriage recognised abroad than a civil partnership.

There were two perspectives from those who supported this option. The first was that civil partnerships would become obsolete with the introduction of same sex marriage, and that a line should be drawn under them at that point. The second view was that there should never have been legal recognition of same sex relationships offered by civil partnerships. Respondents with the latter view tended to view civil partnerships as undermining the institution of marriage.4

The second consultation set out the arguments for and against no new civil partnerships after a certain date. Responses were framed in a similar way to the first consultation; either that civil partnerships were no longer needed now that same sex marriage is an option, or that the extension of civil partnerships would be a threat to marriage. Others referred to the similarity between civil partnerships and marriage, and therefore, that there is no need to have two systems running in parallel.7

Other points included:

civil partnerships should be closed as they are a reminder of inequality; they were an unsatisfactory compromise used to suppress the campaign for marriage equality

future civil partnerships should be closed, but only in the context of a wider review of regulated family relationships

the UK Government announced its intention to introduce different sex civil partnerships after the Scottish Government's consultation was published. A number of respondents argued against the closure of future civil partnerships because people may cross the border to enter into a different sex civil partnership. Some also argued that the decision to introduce different sex civil partnership in England and Wales "added impetus" for Scotland to do the same.

Extending civil partnerships to different sex couples

During the first consultation, the Scottish Government set out its reasons against extending civil partnerships to different sex couples. These included:

demand would be low

recognition elsewhere in the UK and overseas would be limited

society's understanding of it might be limited

Scots law provides some rights already for cohabiting couples

it is possible to have a civil marriage

it would increase complexity

the costs would be disproportionate.

The concern most frequently raised with those who agreed with the Scottish Government's position at the time, was that the introduction of different sex civil partnership would undermine the institution of marriage.

Those who supported the introduction of different sex civil partnership commented most frequently that it would offer equality, with all couples having the same options open to them. The assertion that demand for different sex civil partnership would be low was questioned, with individual respondents indicating they wished to enter a different sex civil partnership.

Reasons for different sex couples wanting to enter civil partnerships included:

wanting greater legal and financial protections

not being able to remarry on religious or ethical grounds

having been in an unhappy or abusive marriage

considering marriage to be a patriarchal institution.

Another observed advantage of different sex civil partnerships would be that trans people would not have to end their civil partnership if they obtain a Gender Recognition Certificate.

The Scottish Government's second consultation set out the arguments for and against extending civil partnerships to different sex couples. This time the arguments in favour of extending civil partnerships included:

that it would be fair and equitable

limited demand is irrelevant because it is crucial and necessary for the law to be fair

marriage is seen by some as old fashioned, religious and patriarchal.

The arguments against extending civil partnerships to different sex couples included:

the legal effect, benefits and implications of marriage and civil partnership are the same

the recognition of different sex civil partnership overseas is likely to be limited which may have adverse consequences in relation to legal presumptions that flow from marriage status in other jurisdictions.

Respondents to the 2018 consultation who were in favour of extending civil partnerships, cited reasons such as equality, freedom of choice, access to rights and responsibilities, and family security. Additional arguments in favour of extending civil partnerships to different sex couples included:

advantages for women who reject the institution of marriage because it is seen as patriarchal, and who reject the traditional expectations of women at wedding ceremonies

it might promote family stability for unmarried different sex couples with children

for bisexual people, the sex of their partner would not play a role in determining whether they enter a marriage or civil partnership.

Those against extending civil partnerships to different sex couples tended to state that there was no point because it is very similar to marriage, and that cohabiting couples already benefit from many rights, more so than in England and Wales. There were also comments about undermining marriage, and introducing complexity.

Public attitude survey

The British Social Attitudes Survey recently asked people about opposite sex civil partnerships. The latest report from 20198 shows strong support for different sex civil partnerships:

We find evidence of substantial public support for opposite-sex civil partnerships, coinciding with the announcement of their introduction in October 2018.

Two-thirds (65%) of the public support civil partnerships for opposite-sex couples, while less than one in ten (7%) oppose them.

Those who do not identify with a religion are more supportive of the idea that a man and woman should be able to have a civil partnership (73%), compared with those who do identify with a religion (34%-67%).

Around half (49%) of those with no formal education support civil partnerships for opposite-sex couples compared with seven in ten of those educated to degree level or above (71%).

What will the Bill do?

The aim of the Bill is to allow for different sex couples to form civil partnerships, with similar legal rights and responsibilities to marriage.

To do this, the Bill would also:1

make consequential changes to Scottish family law

allow for the recognition of certain overseas relationships between different sex couples

make consequential amendments to legislation concerning gender recognition

create an offence of forcing someone into a civil partnership.

The Bill, therefore, would make a number of changes to existing legislation. This section provides an outline of these changes, which largely reflect existing provisions for same sex civil partnerships and marriage. These are often quite technical, but are explained further in both the Policy Memorandum and the Explanatory Notes.

Civil partnership for different sex couples

Different sex civil partnerships

Section 1 of the Bill removes the reference to a civil partnership being 'of the same sex' in section 1(1) of the 2004 Act. By removing the same sex requirement, the Bill makes civil partnerships available to different sex couples.

Who will be eligible?

The Bill, section 4, will remove the reference to 'same sex' under section 86 of the 2004 Act regarding eligibility criteria. This will allow different sex couples to form a civil partnership.

Other civil partnership eligibility criteria is maintained, such as both partners must:

have reached the minimum age of 16

not be related

not be in an existing marriage or civil partnership.

There were some responses to the consultation that suggested civil partnerships could be made available to sibling couples. The Scottish Government does not consider that sibling civil partnerships are needed. Its view is that the main driver for such a call is in relation to inheritance tax, which is reserved. The Scottish Government's view is that it would be more proportionate to change legislation on inheritance tax rather than introduce sibling civil partnerships.1

Recognition of overseas different sex relationships

The Bill, at section 2 and Schedule 1, will allow for overseas registered partnerships to be recognised as civil partnerships in Scotland. These have different names around the world, such as civil union (New Zealand, Malta, Israel), domestic partnership (some states in the USA), and registered partnership (Denmark, Sweden and Norway).

The intention is that those in different sex civil partnerships from overseas will have access in Scotland to the rights and responsibilities that flow from that relationship. This reflects similar provision for same sex overseas civil partnerships in Schedule 20 of the 2004 Act. This means that some overseas different sex couples will have more rights and responsibilities than in their original jurisdiction, such as different sex couples who have a French PACS. For others, such as those with a civil union from New Zealand, the rights and responsibilities will be very similar.

Second registration of civil partnership

Couples who had their marriage ceremony outside the UK, but are not able to prove they are married, can go through a second marriage ceremony. Section 20 of the Marriage (Scotland) Act 1977 provides for such couples to make a statutory declaration, solemnised by a civil registrar. This provision had traditionally covered those who were not registered by their local civil authorities, or where civil status documents were not issued.

The Bill, at section 8, aims to extend this to cover civil partnership registration for both same sex and different sex couples. Civil partnerships are less likely to have been informally created, especially given the recent introduction of civil partnerships in different parts of the world. However, the intention is that this would cover couples who cannot evidence their relationship because their documents have been destroyed through, for example, war, civil disturbance or natural disaster.1

Interim recognition of different sex civil partnerships formed outwith Scotland

Section 3 of the Bill provides for the interim recognition of different sex civil partnerships formed in England, Wales or Northern Ireland.

Civil partnerships for different sex couples are now available in the rest of the UK. Therefore, the Bill provides for those relationships to be recognised as marriages in Scotland, until civil partnerships for different sex couples in Scotland come into force.

A similar situation arose when the Marriage (Same Sex Couples) Act 2013 came into force in England and Wales, allowing same sex couples to marry. Schedule 2 of the 2013 Act made temporary provision to recognise same sex marriage from England and Wales as civil partnerships in Scotland.

Religious or belief registration

When civil partnerships were first introduced, they could only be registered by civil registrars. This was later amended by the Marriage and Civil Partnership (Scotland) Act 2014 which provided several ways for a religious or belief celebrant to be authorised to register civil partnerships. It means that, currently same sex civil partnerships can be registered by:1

Civil registrars

A celebrant of a religious or belief body prescribed by regulations made by the Scottish Ministers

A person nominated by a religious or belief body to the Registrar General and approved by the Registrar General to act as a celebrant

A celebrant belonging to a religious or belief body who has been granted temporary authorisation by the Registrar General. This may be for a specific civil partnership (or civil partnerships) or for a period of time.

The Bill, at sections 5, 6 and 7, aims to replicate these arrangements for religious or belief registration of different sex civil partnerships.

While the number of same sex religious or belief civil partnerships are low (the Policy Memorandum says fewer than ten), the Scottish Government suggests it could be higher for different sex couples. This is based on the knowledge that there are more different sex couples in society than same sex couples. It seems likely that most different sex couples would choose a civil registration, but that some might wish to have a religious or belief civil partnerships.1

When the 2014 Act was introduced, specific provisions were made in the Equality Act 2010, via a section 104 Order, to protect religious or belief celebrants and bodies who do not wish to take part in the registration of civil partnership and the solemnisation of same sex marriage. The intention is to extend this provision to the religious or belief registration of different sex civil partnership.

Marriage between civil partners in a qualifying civil partnership

It is currently possible to change from a same sex civil partnership registered in Scotland to a marriage. This can either be done through a marriage ceremony or under an administrative route. Civil partners who were registered outside of Scotland can only change their relationship to marriage through having a marriage ceremony.

Section 10 of the Bill makes provision for different sex couples in a civil partnership to change their relationship to a marriage in the same way as same sex civil partners.

The Scottish Government says this approach is consistent with the policy of aligning different sex civil partnership with same sex civil partnership.1

However, the UK Government is giving consideration to the idea of different sex couples in a marriage converting their relationship in to a civil partnership. This is discussed further below.

Dissolution

There are currently two grounds for dissolution of a civil partnership in Scotland. One is irretrievable breakdown; the second is if either party obtains an interim Gender Recognition Certificate. In either case, an application to the court is required.

Irretrievable breakdown

Irretrievable breakdown can be shown by:

the parties not cohabiting for one year, and with both parties consenting to dissolution

the parties not cohabiting for two years, regardless of whether or not both parties consent to dissolution

one of the parties behaving in such a way that the other party cannot reasonably be expected to cohabit with them.

The Scottish Government intends that the grounds for dissolution of different sex civil partnership be the same as with same sex civil partnership.

However, in both same sex and different sex marriage, 'adultery' can be used to establish irretrievable breakdown of the relationship - a divorce. The Policy Memorandum to the Bill sets out that adultery is defined at common law as voluntary heterosexual intercourse outside marriage. The Scottish Government does not intend to extend adultery to the law of dissolution of civil partnership. "If a civil partner wishes to raise a dissolution action based on the sexual infidelity of his or her partner, then there is the option of raising an action on the basis of one of the parties behaving in such a way that the other party cannot reasonably be expected to cohabit with him or her." 1 This will remain one of the differences between marriage and civil partnership.

Interim Gender Recognition Certificate

A person in a same sex civil partnership who is seeking to obtain a Gender Recognition Certificate under the Gender Recognition Act 2004, would be required to end that civil partnership. They would be issued an with interim Gender Recognition Certificate which would allow for the dissolution of the civil partnership. This is because two people of different sexes cannot currently have a civil partnership. They would need to end the civil partnership either by dissolving the relationship or by changing it to a marriage, unless both partners are obtaining legal gender recognition on the same day. 7

If different sex civil partnerships are introduced, a couple in a civil partnership in which one person is seeking gender recognition, could stay in their civil partnership. 7

The Bill would end the requirement for a person in a civil partnership who obtains a Gender Recognition Certificate to end their relationship, as long as their partner consents to the civil partnership continuing.

Schedule 2, paragraph 5, makes consequential modifications to the Gender Recognition Act 2004. These mirror current provision in respect of marriage.

The Bill makes provision so that a Gender Recognition Panel can issue a full Gender Recognition Certificate to a civil partner, as long as the other partner consents to the civil partnership continuing by making a statutory declaration. It is a crime to deliberately make a false statement in a statutory declaration.9 If the partner does not consent to the civil partnership continuing, then the Gender Recognition Panel is required to issue an interim Gender Recognition Certificate.

Religious divorce

Courts have the power to postpone granting a decree of divorce where there is a religious impediment to one of the parties remarrying and the other party can act to remove the impediment. The only prescribed body is the Jewish religion in terms of the Divorce (Religious Bodies) (Scotland) Regulations 2006.

The Policy Memorandum to the Bill sets out that:1

An impediment to divorce may arise within Judaism where one party refuses to grant the get (Jewish religious divorce). The get is granted by the Beth Din (court of Jewish religious law). Without the get, the other spouse may find it difficult to remarry in some branches of Judaism, such as Orthodox Judaism.

The Bill, at section 9, replicates this provision in relation to the postponement of a decree of dissolution of a civil partnership where a religious impediment to marriage exists. The Scottish Government said that if it did not make this provision, it could place women in the Jewish community at a disadvantage, and potentially other communities if other religious bodies should be prescribed.

Forced civil partnerships

Section 11 of the Bill extends provision on forced marriage to civil partnerships. Forced marriage is where one or both parties do not, or cannot, consent to the marriage. There are currently no provisions in place that relate to same sex forced civil partnership. However, the Scottish Government's view is that the creation of different sex civil partnerships could create a loophole. Creating an offence of forced civil partnership, that applies to same sex and different sex couples, would close that loophole.1

Family law changes

The Bill, at Schedule 2, paragraphs 1 to 4, makes amendments to family law, so that they make provision for different sex civil partnerships. For example:

There is a presumption, in section 5 of the Law Reform (Parent and Child) (Scotland) Act 1986, that a man is the father of a child if he is married to the mother at any time during the pregnancy. The Bill extends this presumption so that a male civil partner of a woman is presumed to be the father of a child.

Under section 3 of the Children (Scotland) Act 1995, fathers have parental rights and responsibilities under certain circumstances, one being that he is married to the mother at the time of conception or later. The Bill makes provision so that the father will acquire these rights when he is in a civil partnership with the mother at the time of conception or later.

The Bill will amend references to 'child of the family' in the Children (Scotland) Act 1995 and the Family Law (Scotland) Act 1985, to take account of a child being the biological child of two civil partners.

Future considerations

Section 104 Order

If the Bill is passed, there are a number of consequences that flow which are reserved to the UK Parliament. The Policy Memorandum states that the Scottish Government and UK Government will prepare an Order, under section 104 of the Scotland Act 1998, to cover these matters.

A section 104 Order is used to make consequential modifications to reserved law, in consequence of legislation passed by the Scottish Parliament. It means that changes can be made to reserved legislation that reflect changes in legislation in Scotland. Section 104 Orders are voted on at Westminster.

The Scottish Government has identified a number of areas that may need to be covered by the Order, including:

Amendments to the Equality Act 2010 - this would protect religious or belief celebrants who may not wish to register different sex civil partnerships.

Amendments to reserved UK legislation to treat male civil partners of women in the same way as husbands of women.

Changes to reserved public service pension schemes, the state pension scheme, and private sector occupational pension schemes.

Changing from civil partnership to marriage or marriage to civil partnership

It is currently possible to change a same sex civil partnership registered in Scotland to a marriage. This can either be done through a marriage ceremony or under an administrative route.

The Scottish Government explains that the reason for this is linked to same sex marriage, which validated same sex relationships as "fully deserving of equal societal recognition and the same respect as mixed sex relationships."1 The Bill extends this to different sex civil partners so that they are not treated differently from same sex couples.

There are no plans to allow married couples to change their relationship to a civil partnership.

However, the UK Government has consulted on the possibility of converting marriage into civil partnership and vice versa. The consultation ran from 10 July to 20 August 2019.2 Reference is made to the initial surge in demand for conversion to marriage, when it was first introduced in England and Wales, and that this later reduced significantly. A similar pattern can be seen in Scotland.

The Civil Partnerships, Marriages and Deaths (Registration etc.) Act 2019 enables the Secretary of State to make regulations for (or bringing an end to) conversion between civil partnership and marriage and vice versa. The considerations include:

future demand for conversion

not wishing to create rights that might not be used

allowing conversion in both directions would change the original purpose, which was to allow same sex couples to convert to a relationship that was previously unavailable

allowing broad conversion rights could risk blurring the distinction between marriage and civil partnership, and undermining the seriousness of the decision taken to enter a particular form of relationship

the potential administrative complexity, and potential confusion about rights and the status of relationships.

The UK Government has also considered whether to simply bring an end to conversion rights for same sex couples, and whether there should be a time limit on the right to convert.

The current proposal "is to allow opposite-sex married couples the opportunity to convert to a civil partnership".2 This would be time limited, and that eventually, all conversion rights would end. The rationale for this is that people would have an opportunity to convert, and then after a period of time, it would no longer be an issue.

The UK Government has not stated its final position on the basis of the consultation.

On 20 January 2020, the UK Government launched a consultation on conversion provisions for Northern Ireland, now that same sex marriage and different sex civil partnership have been introduced.4The consultation runs until 23 February 2020.

Costs

The Financial Memorandum to the Bill provides detail on how the Scottish Government has calculated demand for different sex civil partnership.1 This is required to estimate the costs in relation to the registration of different sex civil partnerships, and the rights and responsibilities that different sex civil partners will have.

The Scottish Government has looked at the take up of civil partnership in Scotland and compared it with other jurisdictions - the Netherlands, France and New Zealand. On this basis it has calculated that there could be between 100 and 150 different sex civil partnerships each year. For the purposes of calculating costs, it has chosen the figure of 109 civil partnerships a year, although of course, there is a high degree of uncertainty with that figure.

It is expected that the day to day costs of registration will be met by the fees paid by couples entering a different sex civil partnership. This is in line with current practice for marriage and same sex civil partnership. Total statutory fees for marriage and civil partnership are £125.

There will be set up costs to allow National Records of Scotland (NRS) to update their IT system, registrars handbook, update forms, and organise training for NRS staff and registrars.

There is no planned publicity campaign, but the Scottish Government will work with NRS to provide information to couples about different sex civil partnership.

Based on experience with the introduction of same sex marriage, it is estimated that set up costs for NRS in relation to registration will be £200,000. Similarly, it is estimated that there will be one-off costs to local authorities for familiarisation and training of £200,000, and of £40,000 for the chairs of private sector defined benefit pension schemes.

Annual running costs are estimated at £528,000, which includes legal aid for dissolution, costs in relation to public and private sector survivor benefits, and, registration costs for different sex couples.