Issue 13: EU-UK Future Relationship Negotiations

Following the UK's departure from the EU, the negotiations to determine the future relationship began on 2 March 2020. Over the course of the negotiations, SPICe will publish briefings outlining the key events, speeches and documents published. This briefing describes what happened in Round 8, as well as the Prime Minister's timetable for a deal by 15 October and the dispute over proposals in the UK Internal Market Bill.

Executive Summary

This is the thirteenth in a series of SPICe briefings covering the negotiations on the future relationship between the EU and the UK.

This briefing:

Describes the Prime Minister's position that if agreement on a trade deal can not be reached by 15 October then there will be no deal.

Outlines the dispute over the UK's approach to the Ireland/Northern Ireland Protocol contained in the UK Internal Market Bill, and its potential impact on the negotiations.

Analyses what happened in Round 8 of the EU-UK future relationship negotiations as well as the time available for further discussions.

Going into Round 8

At the end of the last round (Round 7), both chief negotiators reported little progress had been made in the talks. The key issues cited as sticking points remained level playing field issues (including State Aid) and fisheries. From the EU's point of view, Michel Barnier also cited governance (in relation to dispute settlement), law enforcement (in relation to guarantees on the protection of citizen rights and personal data) and mobility and social security coordination as areas where progress is needed.

Round 8 of the EU-UK negotiations took place this week leaving only one further round of talks formally timetabled (Round 9 - w/c 28 September).

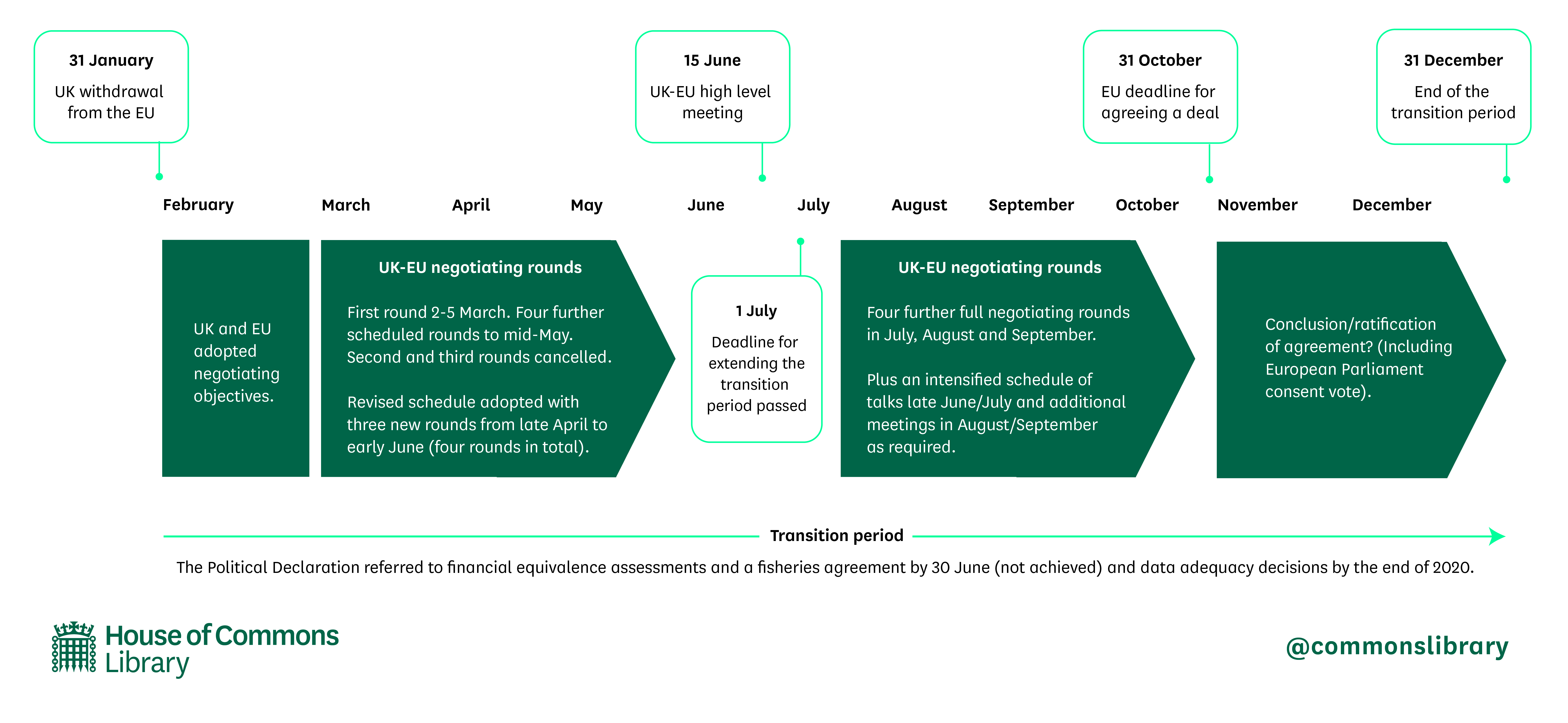

The EU's timeline for an agreement

The EU's timeline for an agreement is described by the House of Commons Library:

October deadline

The EU has said an agreement needs to be reached by the end of October to allow time for ratification by the end of the year. A draft EU ratification timeline indicates the EU would like an agreed legal text ready by the beginning of October, to make time for legal and linguistic revisions.

The next European Council meeting is on 15-16 October. The EU envisages this is when political approval for an agreement could be given by EU heads of state and government. However, as has happened previously in the Brexit process, an additional EU leaders’ summit could be called to approve a deal.

Time needed for ratification

The EU’s formal ratification procedures require an EU Commission proposal for a Council decision on the deal by early November. The agreement would be sent to the European Parliament in mid-November. The EU Parliament would need to give consent to the agreement, with a vote expected in December.

This timetable is based on the assumption that the agreement will not be “mixed” (covering both EU and Member State competences). A mixed agreement would also require ratification within each Member State, although aspects could be applied provisionally ahead of full ratification.

In a webinar hosted by The Institute of International and European Affairs (IIEA) on 2 September, the EU's chief negotiator Michael Barnier said:

We have no more time to lose. We must have a final agreement by the end of Oct if we're to have a new partnership in place by January 1.

Prime Minister's date for 'no deal'

Ahead of Round 8, the UK Government outlined its position that if agreement on a trade deal could not be reached by 15 October then there will be no deal.

On 7 September, the Prime Minister issued the following statement:

We are now entering the final phase of our negotiations with the EU.

The EU have been very clear about the timetable. I am too. There needs to be an agreement with our European friends by the time of the European Council on 15 October if it’s going to be in force by the end of the year. So there is no sense in thinking about timelines that go beyond that point. If we can’t agree by then, then I do not see that there will be a free trade agreement between us, and we should both accept that and move on.

While the EU has outlined the same timetable as indicative of when a deal must be done to allow for ratification, this is the first time either side has publicly set a point in time when they will close negotiations.

The Prime Minister then stated that no deal "would be a good outcome for the UK", and without a deal the UK's trading relationship with the EU's will be like Australia’s:

We will then have a trading arrangement with the EU like Australia’s. I want to be absolutely clear that, as we have said right from the start, that would be a good outcome for the UK. As a Government we are preparing, at our borders and at our ports, to be ready for it. We will have full control over our laws, our rules, and our fishing waters. We will have the freedom to do trade deals with every country in the world. And we will prosper mightily as a result.

While much of the EU-Australia trade is on WTO terms, Australia does have agreed arrangements with the EU on cooperation and mutual recognition - a Partnership Framework and a Mutual Recognition Agreement to facilitate trade in industrial products.

The Prime Minister continued:

We will of course always be ready to talk to our EU friends even in these circumstances. We will be ready to find sensible accommodations on practical issues such as flights, lorry transport, or scientific cooperation, if the EU wants to do that. Our door will never be closed and we will trade as friends and partners – but without a free trade agreement.

There is still an agreement to be had. We will continue to work hard in September to achieve it. It is one based on our reasonable proposal for a standard free trade agreement like the one the EU has agreed with Canada and so many others. Even at this late stage, if the EU are ready to rethink their current positions and agree this I will be delighted. But we cannot and will not compromise on the fundamentals of what it means to be an independent country to get it.

The Scottish Government Cabinet Secretary for the Constitution, Europe & External Affairs responded to the Prime Minister's statement on Twitter:

In the few days before the Prime Minister's statement, the UK's chief negotiator David Frost also made some public statements on the forthcoming round of negotiations.

On 4 September, David Frost shared a link to agenda for Round 8 on Twitter writing:

We look forward to welcoming @MichelBarnier and his team to London next week. We have scheduled lots of time for discussions, as we should at this point in the talks. However, the EU still insists we change our positions on state aid and fisheries if there are to be substantive textual discussions on anything else. From the very beginning we have been clear about what we can accept in these areas, which are fundamental to our status as an independent country. We will negotiate constructively but the EU's stance may, realistically, limit the progress we can make next week.

On 5 September the Mail on Sunday published an interview with David Frost where is is quoted as saying:

[The EU] have not accepted that in key areas of our national life we want to be able to control our own laws and do things our way and use the freedoms that come after Brexit...

We are not going to be a client state. We are not going to compromise on the fundamentals of having control over our own laws. We are not going to accept level playing field provisions that lock us in to the way the EU do things; we are not going to accept provisions that give them control over our money or the way we can organise things here in the UK and that should not be controversial – that's what being an independent country is about, that's what the British people voted for and that's will happen at the end of the year, come what may."

Implementation of the Ireland/Northern Ireland Protocol

The EU has stated throughout the EU-UK negotiations that it considers the full implementation of the Withdrawal Agreement, and in particular the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland, as critical and linked to any agreement on the EU-UK future relationship. For example, following the first meeting of the Specialised Committee on the Protocol on Ireland / Northern Ireland the EU stated:

A new partnership can only be built on the faithful and effective implementation of the Withdrawal Agreement.

In May 2020, the UK Government published its plans for the implementation of the Protocol. The EU welcomed this and the related technical discussions on implementation at the second meeting of the Specialised Committee on the Implementation of the Protocol on Ireland / Northern Ireland in July. But concern over the tight timescales were also expressed by the EU, which stated it:

remains concerned as to the progress of practical and time-consuming preparations needed for the full application of the Protocol.

Until this week, no further meeting of the Specialised Committee on the protocol had been held.

Further information on the functions and tasks of the Withdrawal Agreement's Joint Committee and it's Specialised Committees is available in Issue 6 of this briefing series.

The UK Internal Market proposals

Following press reports that the UK Government intended to legislate though the Internal Market Bill in a manner contrary to the Ireland/Northern Ireland Protocol, on 8 September the UK Government's Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, Brandon Lewis, responded to an urgent question in the House of Commons.

When asked to assure the House of Commons that nothing that is proposed in the Internal Market Bill would breach international legal obligations or international legal arrangements, the Secretary of State said:

I would say to my hon. Friend that yes, this does break international law in a very specific and limited way. We are taking the power to disapply the EU law concept of direct effect, required by article 4, in certain very tightly defined circumstances. There are clear precedents of this for the UK and, indeed, other countries needing to consider their international obligations as circumstances change. I say to hon. Members here, many of whom would have been in this House when we passed the Finance Act 2013, that that Act contains an example of treaty override. It contains provisions that expressly disapply international tax treaties to the extent that these conflict with the general anti-abuse rule. I say to my hon. Friend that we are determined to ensure that we are delivering on the agreement that we have in the protocol, and our leading priority is to do that through the negotiations and through the Joint Committee work. The clauses that will be in the Bill tomorrow are specifically there should that fail, ensuring that we can deliver on our commitment to the people of Northern Ireland.

The following day (9 September 2020), the UK Government published the United Kingdom Internal Market Bill 2019-21.

SPICe will provide further analysis on this bill and its implication for Scotland. The focus taken in this briefing is the EU-UK future relationship negotiations and any potential impact the internal market proposals will have on the negotiations.

European Commission reaction

The European Commission called an extraordinary meeting of the EU-UK Joint Committee. This meeting happened on 10 September in London after which the European Commission issued a statement (emphasis added):

Following the publication by the UK government of the draft “United Kingdom Internal Market Bill” on 9 September 2020, Vice-President Maroš Šefčovič called for an extraordinary meeting of the EU-UK Joint Committee to request the UK government to elaborate on its intentions and to respond to the EU's serious concerns. A meeting took place today in London between Vice-President Maroš Šefčovič and Michael Gove, Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster.

The Vice-President stated, in no uncertain terms, that the timely and full implementation of the Withdrawal Agreement, including the Protocol on Ireland / Northern Ireland – which Prime Minister Boris Johnson and his government agreed to, and which the UK Houses of Parliament ratified, less than a year ago – is a legal obligation. The European Union expects the letter and spirit of this Agreement to be fully respected. Violating the terms of the Withdrawal Agreement would break international law, undermine trust and put at risk the ongoing future relationship negotiations.

At the same time, Round 8 of the negotiations was ongoing. The outcome of this round is reported on in the following section.

What happened in Round 8

The eighth round of formal talks took place over 8-10 September 2020 and followed on from a meeting of the chief negotiators in London last week. The agenda for Round 8 indicated that lengthy sessions were timetabled across almost all area of discussion.

Despite the dispute over the UK's internal market proposals, the talks continued. Statements from both chief negotiators made at the end of the round are analysed in the next section.

Statements from the UK and EU chief negotiators

Following Round 8, the UK's chief negotiator, David Frost, made a statement describing the round:

These were useful exchanges. However, a number of challenging areas remain and the divergences on some are still significant.

On the timetable and the deadline set by the Prime Minister, he said:

We remain committed to working hard to reach agreement by the middle of October, as the Prime Minister set out earlier this week.

We have agreed to meet again, as planned, in Brussels next week to continue discussions.”

David Frost made no reference to the dispute over the UK's internal market proposals.

Chief negotiator Michel Barnier also provided a statement from the EU's perspective. He stated that:

The EU remains committed to an ambitious future partnership with the UK. This would clearly be to the benefit of both sides. Nobody should underestimate the practical, economic and social consequences of a “no deal” scenario.

Barnier said that the EU had shown flexibility on "the role of the European Court of Justice, the future legislative autonomy of the UK, and fisheries" but that "the UK has not engaged in a reciprocal way on fundamental EU principles and interests". A 'level playing field' to ensure fair competition is one of the EU's key negotiating priorities. On this, Barnier said:

The UK is refusing to include indispensable guarantees of fair competition in our future agreement, while requesting free access to our market.

During the negotiation on level playing field issues, the EU has sought clarity on the UK's plans for its State Aid regime. On 9 September the UK provided some details stating that the UK will "follow World Trade Organisation (WTO) subsidy rules and other international commitments, replacing the EU state aid laws, from January 1" but that the final regime would not be set until next year following consultation. Barnier commented that:

We have taken note of the UK government's statement on “A new approach to subsidy control”. But this falls significantly short of the commitments made in the Political Declaration.

Similarly, we are still missing important guarantees on non-regression from social, environmental, labour and climate standards.

Modern trade agreements are about ensuring sustainable and fair partnerships with high standards in areas like the environment, climate, employment, health and safety, and taxation. These principles are now at the heart of EU trade policy: with the UK, and with other partners around the world.

And they are at the heart of the EU's negotiating mandate. For the EU, its Member States and the European Parliament, any future economic partnership, regardless of its level of ambition, must ensure that competition is both free and fair.

Barnier went onto list further areas of concern to the EU. These included areas with devolved responsibilities such as judicial cooperation and law enforcement, fisheries and the sanitary and phyto-sanitary regime:

The UK has moreover not engaged on other major issues, such as credible horizontal dispute settlement mechanisms, essential safeguards for judicial cooperation and law enforcement, fisheries, or level playing field requirements in the areas of transport and energy.

There are also many uncertainties about Great Britain's sanitary and phyto-sanitary regime as from 1 January 2021. More clarity is needed for the EU to do the assessment for the third-country listing of the UK.

In what has been interpreted as a reference to the dispute over the UK's internal market proposals, Barnier finished his statement saying:

To conclude a future partnership, mutual trust and confidence are and will be necessary. The Chief Negotiators and their teams will remain in contact over the coming days.

At the same time, the EU is intensifying its preparedness work to be ready for all scenarios on 1 January 2021.

Future meetings

The rest of the dates for talks agreed under the negotiation's Terms of Reference are:

(As necessary) - Meetings of the Chief Negotiators / their teams / specialised sessions: weeks of 14 and 21 September (Brussels and London)

Round 9: week of 28 September to 2 October (Brussels)

Statements from the chief negotiators confirmed that meetings would take place next week (w/c 14 September).

One more formal round of talks is scheduled. Further rounds can be agreed, but there is very little time to conduct more discussions ahead of the Prime Minister's deadline of 15 October.

In addition, the EU have set a deadline for the end of September for the UK to change its approach to the Ireland/Northern Ireland Protocol in the UK Internal Market Bill:

Vice-President Maroš Šefčovič called on the UK government to withdraw these measures from the draft Bill in the shortest time possible and in any case by the end of the month.

The UK government's response to this is likely to affect the outcome of the negotiations in Round 9.

New EU Trade Commissioner appointed

Following the resignation of Phil Hogan, Commission President Ursula von der Leyen assigned trade responsibilities to another Commissioner on an interim basis. In a statement on 27 August she said:

Executive vice-president Valdis Dombrovskis will assume interim responsibilities for trade matters and at a later stage I will decide upon the final allocation of portfolios within the College of Commissioners.

Joint Ministerial Committee (EU Negotiations) communiqué: 3 September 2020

On 3 September, the Joint Ministerial Committee (EU Negotiations) met by video conference. This meeting was attended from the Scottish Government the Cabinet Secretary for the Constitution, Europe and External Affairs, Michael Russell MSP and the Minister for Europe and International Development, Jenny Gilruth MSP.

The short communiqué published read:

The Committee discussed progress on negotiations with the EU, an update on transition readiness, the implementation of the Northern Ireland Protocol, including the legislative timetable, progress with work on the UK Common Frameworks Programme and interactions with the UK Internal Market.

SPICe briefing: Trade Agreements and their Potential Impact on Environmental Protection

On 4 September SPICe published a briefing on trade deals and their potential impact on environmental protection. The Chapter analysing the EU-UK negotiations is reproduced below.

The trade agreement with the EU: State of play

The non-binding Political Declaration attached to the Withdrawal Agreement announced the negotiation of a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) between the UK and the EU. The European Union published a text of the draft treaty in March 2020 that it will use as template for the negotiations with the UK. The UK also published its working draft in May 2020.

EU FTAs do not necessarily resemble each other. The EU has dozens of FTAs with other countries, and they vary significantly. For this reason, it is impossible to predict the terms of a future UK-EU FTA: even among the FTAs of the EU, which could serve as a template, there is a considerable variety.

Judging from the draft texts circulated by the EU and the UK in the spring of 2020, it appears that the EU is seeking to negotiate an FTA similar to that of the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement, which sets the foundation for Ukraine’s prospect to become a member of the EU. Instead, the UK have used “pure” EU FTAs as a template, like those with Japan, Korea and Canada. The distinction is critical: Ukraine is preparing to become an EU member state and, therefore, is effectively committing to align to EU rules, including in the field of environmental protection, with a medium-term plan to be bound by them directly.

Commitments to maintain a level playing field are a key sticking point of the negotiations between the EU and the UK. Reference to the level playing field was included in the Political Declaration agreed in October 2019, which stated:

the precise nature of commitments should be commensurate with the scope and depth of the future relationship and the economic connectedness of the Parties.

The document outlining the EU’s negotiating position, published in March 2020, says (emphasis added):

Given the Union and the United Kingdom’s geographic proximity and economic interdependence, the envisaged partnership must ensure open and fair competition, encompassing robust commitments to ensure a level playing field. (…) To that end, the envisaged agreement should uphold the common high standards in the areas of State aid, competition, state-owned enterprises, social and employment standards, environmental standards, climate change, and relevant tax matters.

On environmental matters, the document reproduces the wording enshrined in the 2018 Draft withdrawal Agreement:

The envisaged partnership should ensure that the common level of environmental protection provided by laws, regulations and practices is not reduced below the level provided by the common standards applicable within the Union and the United Kingdom at the end of the implementation period in relation to at least the following areas: access to environmental information; public participation and access to justice in environmental matters; environmental impact assessment and strategic environmental assessment; industrial emissions; air emissions and air quality targets and ceilings; nature and biodiversity conservation; waste management; the protection and preservation of the aquatic environment; the protection and preservation of the marine environment; the prevention, reduction and elimination of risks to human health or the environment arising from the production, use, release and disposal of chemical substances; and climate change.

In this vein, the EU may require that standards continue to stay aligned in the future, hinting to a mechanism of “dynamic alignment” measured against the EU rules (e.g. on state aid); in other areas, it may demand at least the guarantees of “non-regression” and “ratcheting-up” (e.g. on sustainable development, social and labour rights, environmental protection) (see Box 5).

Box 5: non-regression v. dynamic alignment v. ratchet-up

If States A and B commit to “non-regression,” they are each free to pass new laws, as long as they do not weaken the standards they had at the time of the commitment. For instance, if A passes more advanced rules on workers’ protection increasing the number of statutory leave days, B does not have to catch up. However, neither State can “regress,” for instance reducing the holiday entitlement it granted at the time of the agreement.

Through a “ratchet-up” clause on future levels of protection, A and B can agree that, if both independently increase the level of protection on a given matter, the new level is subject to non-regression. For instance, if both A and B, successively, increase the holiday entitlement, the new shared standard would become entrenched. Neither could no longer amend its law to reduce it – even if B had no obligation to match A in the first place.

If States A and B commit to “dynamic alignment,” each new law passed by A in the relevant field must be mirrored by B to match the enhanced standard. If A passes the rule increasing the holiday entitlement, B must do the same, and vice versa. Alignment can be ensured either through a promise of equivalence (B, to catch up, must adopt “comparable” rules to those of A) or straight compliance (B must follow the same rules adopted by A).

The UK has so far rejected the EU’s proposals. The UK Government position paper on trade negotiations with the EU, published in February 2020, makes it plain that the UK wants to be free to diverge from EU laws and standards, as it sees fit, after the end of the implementation period in December 2020. It says (emphasis added):

the Government will not negotiate any arrangement in which the UK does not have control of its own laws and political life. That means that we will not agree to any obligations for our laws to be aligned with the EU's, or for the EU's institutions, including the Court of Justice, to have any jurisdiction in the UK.

On environmental matters specifically, the paper says (emphasis added):

The Agreement should include reciprocal commitments not to weaken or reduce the level of protection afforded by environmental laws in order to encourage trade or investment. In line with precedent, such as CETA, the Agreement should recognise the right of each party to set its environmental priorities and adopt or modify its environmental laws. The Agreement should also include commitments from both parties to continue to implement effectively the multilateral environmental agreements to which they are party. The Agreement should establish cooperation provisions between the parties on environmental issues. In line with precedent such as CETA, EU-Japan EPA and EU-South Korea, these provisions should not be subject to the Agreement's dispute resolution mechanism outlined in Chapter 32.

The UK and the EU are therefore holding rather different negotiating positions. It remains to be seen whether and how this gulf will be bridged in any resulting agreement.

The Scottish Government articulated its position in its response to the UK Government’s consultation on future free trade agreements that:

If the UK leaves the EU and Customs Union, it will become solely responsible for negotiating trade deals. As our response to these consultations demonstrates, Scotland and the rest of the UK will sometimes have very different interests in some negotiations, both in terms of our sectoral priorities, and the value we place on particular social, environmental, ethical or other concerns. […]

Membership of the EU, Single Market and Customs Union has given the UK a strong framework for protecting and advancing individual and collective rights, as well as a range of broader societal interests. Not only do they protect the interests of workers through a variety of measures, and adopt strategies for promoting greater inclusion for Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) and under-represented groups, they also ensure a high level of environmental protection, measures to combat climate change, and high regulatory and animal welfare standards. It is vital that, if the UK leaves the EU, these protections are not lost or traded away in the interests of securing a trade deal.

The outcome of the negotiations will have implications for Scotland’s stated ambition to keep pace with EU regulation, deviation at the UK level may put pressure on Scotland to follow the UK Government in order to protect the UK internal market.

Scottish Government's Programme for Government

In its Programme for Government 2020-21 published on 1 September, the Scottish Government summarised its position at the start of September in relation to EU Exit and the EU-UK negotiations:

It is not clear whether or not there will be an agreement on the future relationship or whether the transition period will end with a deal. However, the UK Government's ambition for the new relationship is so limited that even if an agreement can be struck, the damage to Scotland and its people in many aspects of the relationship is likely to be comparable to "no deal." The Brexit process has already been hugely damaging to Scotland, but we will experience the full, negative, impact of Brexit from 1 January 2021 onwards. The Scottish Government is therefore being forced to prepare for this change, which will hit the Scottish economy hard, at the same time as tackling the pandemic.

There are now less than four months to implement the Withdrawal Agreement and the Northern Ireland Protocol; conclude the negotiations of the future EU‑UK relationship including parliamentary ratification; implement any agreement on the future relationship; and make the necessary practical, procedural and legal changes, including making businesses aware of what it will mean for them. The UK Government's highly political approach to the Northern Ireland Protocol has left businesses - and the UK's Devolved Administrations - largely in the dark as to what is intended.

In any event, it will not be possible to prepare fully for the inevitable economic damage that will be created by forcing Scotland into no deal or a poor deal in just a few months' time and during a period where the sole focus of many businesses will continue to be how to survive the pandemic. There will be a negative Brexit shock. The only question is how big that shock will be. The Scottish Government estimates that Scottish GDP could be up to 1.1% lower by 2022 compared to continued EU membership, this implies that the cost could amount to a cumulative loss of economic activity of up to £3 billion over these two years with much bigger long‑term costs. At a time where we are working tirelessly with people, communities and businesses across Scotland to avoid a second COVID-19 peak and the further economic damage that this would cause, this entirely unnecessary hard Brexit is a bitter pill to swallow.