Trade Agreements and their Potential Impact on Environmental Protection

Trade agreements may interact with environmental protection as a result of differences in standards and measures to protect the environment between trading partners. This briefing outlines differing environmental protection measures and their interactions with potential trade agreements, and discusses Scottish environmental protection in the context of the UK's emerging post-Brexit trade agreements. Cover Image credit: Photo by Paul Rysz on Unsplash

Executive Summary

This briefing first provides a theoretical discussion of the interaction between trade agreements and measures to protect the environment. It then provides an analysis of Scotland's position in the context of emerging UK post-Brexit trade agreements, taking into account the devolved context.

Section 2 explains the functions of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and bilateral or multilateral free trade agreements (FTAs)

Section 3 outlines how different types of environmental protection measures may interact with international trade.

Section 4 provides a number of case studies on the interactions between trade rules and environment, animal welfare and food safety ambitions. First, two detailed case studies on trade in eggs and egg products, and on chlorine-washed chicken are provided, followed by a number of shorter case studies outlining the trade dimensions of proposed environmental measures in Scotland.

Finally, section 5 outlines the interactions between devolution, trade and environmental standards, providing a summary of Scotland's position as a devolved nation in the context of emerging post-Brexit trade agreements.

About the authors

Dr Annalisa Savaresi is Senior Lecturer in Environmental Law at Stirling University, and Dr Filippo Fontanelli is Senior Lecturer in International Economic Law at the University of Edinburgh. At the time of writing, both authors were undertaking a SPICe Academic Fellowship, supporting SPICe researchers with expertise on environmental governance in Scotland, trade and markets, and EU exit. What follows are the views of the authors, not those of SPICe or the Scottish Parliament.

1. Introduction

Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) do not primarily concern environmental matters, but can affect the implementation and efficacy of the environmental policies of the participating countries. In general, when environmental measures restrict trade across countries, they come under scrutiny and can be challenged for breaching the commitments of trade partners.

Under the rules of the World Trade Organization (WTO), environmental measures can be justified but are subject to scrutiny. Permissible environmental measures must be designed to achieve their stated purpose without being unnecessarily restrictive. For instance, an environmental ban on harmful products can be unlawful if appropriate labelling is available, as a less intrusive option, to attain the same goal. Of course, the critical questions are whether the same goal is achieved, and whether the restriction to trade is lesser. These questions must be asked by a country that seeks to regulate environmental matters while complying with its international trade obligations, whether under WTO law or specific trade agreements.

Environmental regulations often play a role in FTAs. If a trade agreement requires the upholding of a regulatory level playing field, it will work as a regulatory “floor,” foreclosing the lowering of standards applicable in any of the participating countries. Conversely, without level playing field safeguards, the deterioration of environmental standards in one country, besides the presumptive detrimental effect on the environment, can create trade distortions: goods produced with fewer regulatory constraints are cheaper to produce, and if sold abroad can undercut the local competition.

The “level playing field” expression indicates a condition for the liberalisation of trade in goods between parties. All companies competing in the same multi-country market must observe comparable rules, for instance on safety, environmental protection, or labour rights. Moreover, the governments should follow comparable rules when intervening in the economy, for instance granting subsidies and state aids. Without these two guarantees, companies subject to more lax rules or receiving more state support would be able to cut production costs and enjoy an unfair advantage when they sell their goods abroad on the markets of their FTA partners.

As such, trade agreements, ultimately, are concerned with these two scenarios. First, the permissibility of high environmental standards that can restrict trade; second, the permissibility of low environmental standards that open up trade asymmetrically, creating trade diversion.

The UK is currently negotiating a trade deal with the European Union (EU). The UK position in January 2021, and that of Scotland within it, will depend chiefly on whether the UK will continue to align with EU environmental standards, and whether it will commit to do so. The EU considers continued alignment with its environmental standards as a precondition for reaching an FTA. Meanwhile, the UK is also in negotiations with the United States (US), which has different environmental policies, measures and standards. A US government document outlining the US-UK Negotiating Objectives specifically mentioned the objective to:

establish a mechanism to remove expeditiously unwarranted barriers that block the export of U.S. food and agricultural products in order to obtain more open, equitable, and reciprocal market access.

Office of the United States Trade Representative. (2019, February). United Kingdom Negotiations Summary of Specific Negotiating Objectives. Retrieved from https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/Summary_of_U.S.-UK_Negotiating_Objectives.pdf [accessed 1 September 2020]

As the competence in environmental matters is largely devolved, Scotland can set its own environmental policies. Through the provisions contained in the UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Continuity) (Scotland) Bill, the Scottish Government aims to ensure that Scotland can ‘keep pace’ with EU standards where it is considered appropriate. However, as international trade is a reserved policy area, the UK-EU (and UK-US) negotiations are run by the UK government. The UK government might provide Scotland with updates on the negotiations and grant some right of consultation but, ultimately, presently is the body constitutionally endowed with the competence to enter international trade agreements. Therefore, Scotland is not in the position to ensure that the UK’s future trade agreements will align with its environmental policies and standards.

This briefing provides a matrix for understanding the interactions between future trade agreements and devolved environmental standards in Scotland, in light of ongoing trade negotiations between the UK Government and the EU and the US respectively.

This briefing does not directly address the effect of Brexit on environmental matters2. iRather, it considers the discrete legal effects of FTAs. It is important to assess this effect at a time when the UK seeks to forge new trade relationships with the EU and US. After the implementation period, ending on 31 December 2020, the UK will be under no obligation to observe EU law. The UK Government has announced its plan to exercise its full regulatory autonomy, diverging from EU rules if necessary. In contrast, and as noted above, the Scottish Government has stated an intention to maintain regulatory alignment with the EU on a case by case basis. While not incompatible in the abstract, these approaches might lead to diverging outcomes without coordination. It is therefore appropriate to examine whether obligations in future trade agreements will constrain the UK’s, and Scotland’s, margin of action in environmental matters.

Likewise, this briefing does not speculate on the effect of Brexit on the exercise of environmental powers by devolved administrations when it comes to intra-UK trade. For the present purposes, it suffices to note that, to a large extent, different environmental rules across the UK might have a practical effect on intra-UK trade. The governments of the UK nations intend that the UK should work, internally, like a single market in which goods and services can be traded without frictions. The legality under UK law of any internal trade obstacle entailed by different rules across the four UK nations exceeds the scope of this briefing, and was surveyed by the UK government in a white paper published on 16 July 2020. Apart from a brief reference to this study, the briefing refers only to international trade, that is, trade occurring across two different countries (or between the UK and a Free Trade Area, like the EU).

2. International trade rules under the WTO and Free Trade Agreements (FTAs)

International trade rules typically 1) prohibit discriminatory, protectionist or inefficient trade restrictions but also 2) encourage the creation of a level playing field to prevent the use of regulatory differences to secure competitive advantages. WTO law mostly covers the first aspect, while FTAs can cover both. Many FTAs seek to establish level-playing field conditions, as well as lower or eliminate tariffs.

2.1 The World Trade Organization (WTO)

In order to act in line with WTO rules, states cannot discriminate against any trading partner country, nor favour domestically-produced goods over imports. The principle of non-discrimination between trade partners is called “most-favoured nation,” indicating that generally there will be no preference in international trade relations (FTAs are an exception to this principle). The prohibition of protectionism is called “national treatment,” because it guarantees that imported products will not be treated worse than national ones.

There is, in principle, an exception for public procurement. That is, public purchasing programmes can be designed to favour domestic goods and contractors. However, since the UK is party to the Government Procurement Agreement of the WTO, even UK public authorities must avoid favouring local businesses when they purchase goods and services.

WTO law also addresses non-tariff trade barriers, e.g. regulatory measures. Domestic measures that have no direct bearing on international trade can constitute trade barriers and, potentially, produce discriminatory or protectionist effects. For instance, Rule 137 of the UK Highway Code requires all drivers to stay in the left lane of two-lane carriageways. This regulatory measure, inevitably, makes it much harder for foreign manufacturers to market in the UK cars with the driver’s seat on the left side of the vehicle. The measure results in a restriction of international trade that favours the local industry. Therefore, the UK government must show that there is a genuine public interest (in this case, traffic safety) and that the restriction of international trade is both incidental and inevitable.

Likewise, WTO law allows countries to justify environmental measures that are trade-restrictive. To do so, they must show that the measure is necessary to protect human or animal health, or that it relates to the conservation of exhaustible natural resources. They must also demonstrate that the measure reflects values that are respected domestically. For instance, a ban on products containing a toxic chemical must be accompanied by an internal prohibition to use that substance in manufacturing. A restriction on imports that does not apply domestically is unlikely to be designed genuinely to advance a public purpose, and is more likely to be protectionist.

WTO rules also permit measures that protect the public morals in a country, even if they incidentally hinder the importation of foreign goods. For instance, the EU banned on its territory the marketing of seal products, pointing out that its citizens have moral objections to the killing of seals for commercial purposes. Canada and Norway challenged the ban before the WTO, but could not overcome the morals-based defence of the EU. Ultimately, the EU could retain the ban, and only had to change the system to grant exceptions that were initially designed to favour EU-based indigenous people, and discriminated against Canadian and Norwegian Inuit peoples.1

2.2 Free Trade Agreements (FTAs)

With a FTA, two or more countries agree to lower trade barriers between them, such as custom duties on imports, enabling goods and services to be sold more easily across their territories. If the FTA does not also create a customs union, each participating country continues to apply its own trade regulations, including tariff rates, to goods coming from third countries. The EU is not a country, but can conclude FTAs with other countries, as it constitutes itself an FTA which is also a customs union.

Therefore, FTAs establish a preferential treatment for goods and services that travel between its member territories. Each participating member, instead, affords to goods from third countries (coming from outside the FTA), the indiscriminate treatment agreed under the rules of the WTO: the most-favoured nation principle (MFN) (see example in Box 1).1

Box 1: Tariffs within and without FTAs

Japan imposes no tariffs on cheese from the EU, thanks to an FTA between the EU and Japan. Gradually, Japan will also eliminate tariffs on US cheese, thanks to the US-Japan trade agreement.2

Outside trade agreements, Japan imposes a tariff as high as 40% on cheese from countries with which it has no preferential trade agreement. This rate is capped (“bound”) under the law of the WTO, and must apply to all goods irrespective of their origins, with the exceptions of goods coming from countries with which Japan has a preferential arrangement (an FTA, or a scheme to promote development cooperation).

For countries that do not trade under preferential terms with Japan (as the EU and the US do), the MFN rate is better than nothing, because it is capped, but it is worse – occasionally much worse – than duty-free treatment.

Like WTO law, FTAs also address non-tariff trade barriers, e.g. regulatory measures. In this briefing, the attention is on the non-tariff barriers that environmental measures can raise against imported goods. Conversely, regulatory measures, rather than impeding trade, sometimes have a different effect: they divert trade, i.e. they take trade away from other countries, thanks to a “race to the bottom” mechanism. For instance, if a country lowers its environmental standards, it might attract manufacturing business at the expense of other more environmentally-conscious countries. Though this effect is not a restriction of trade as such (trade flows are not eliminated, they are merely shifted across markets), it is perceived as an unfair practice within an extended trade territory. Trade partners often set out rules to prevent this instance of trade diversion caused by regulatory differences.

3. The interaction between environmental measures and trade obligations

International trade law (of the WTO or FTAs) does not expressly prohibit or limit one country’s right to protect the environment. However, environmental measures can interact with international trade, incidentally or by design. As a result, these measures can come under scrutiny, and their permissibility can be questioned under international trade law.

It is helpful to distinguish between the ultimate policy goal (for instance, lowering emission levels), the concrete objective of the measure (for instance, reducing the energy consumption of laptops) and the specific measure chosen (for instance, a certification scheme for energy-efficient laptops, or a standard on the maximum use of pesticides). In common parlance, “standards” is often the catch-all word used to refer to a diverse range of environmental policies or measures. Instead, the term “measures” refers specifically to the means through which policy goals are pursued. This distinction has important implications in trade law. While policy goals and concrete objectives are not constrained by international obligations, specific measures can be, insofar as they result in trade restrictions.

It is impossible to predict whether or when the UK will enter into FTAs with the EU and/or US, whether the EU and the UK will agree on level playing field commitments, and whether Scotland and the other UK nations will retain their current environmental measures. However, the next section provides some examples of how international trade obligations may constrain environmental measures. The examples, therefore, draw on international trade law practice, mostly within the WTO framework, rather than on hypothetical future UK scenarios.

3.1 Examples of interactions between trade and environmental measures

a. Rules on preparation and production methods (PPMs):

States sometimes adopt measures restricting the ways in which a product is produced or prepared. Some of these measures treat differently products that, apart from their preparation process, are indistinguishable (that is, they concern non-product related PPMs). This is the case, for instance, of restrictions on the marketing of eggs from chickens held in battery cages. This differential treatment is generally prohibited and requires a specific justification, for example on environmental grounds (there is a margin for labelling requirements, that could relate to non-product related PPMs and be permissible). For instance, the US prohibited the sale of shrimps harvested in ways that could harm sea turtles. In so doing, it effectively limited the import of shrimps from countries using different harvesting techniques. These countries challenged the US measure as an unwarranted trade restriction before the WTO. The WTO ordered the US to adapt its measure: the US was allowed to retain the environmental goal of the restriction, but was ordered to reform the measure to permit the sale of shrimp harvested with turtle-friendly techniques that were not exactly like the one prevailing in the US, but were comparably effective.1

Another preparation measure regards animal testing for the production of cosmetic products. The EU has prohibited the animal testing of finished cosmetic products since 2004, and the testing of cosmetic ingredients since 2009. A general marketing ban for all cosmetic products tested on animals entered into force in 2013.2 These measures were never challenged formally before the WTO. Initially, US-based manufacturers raised the issue of trade-restrictiveness and, for a while, the EU had banned testing on its territory, but not the import of cosmetics tested on animals, fearing that it would be challenged by other countries under WTO law. The European Scrutiny Committee of the House of Commons, in 2002, summarised these doubts as follows:

… as the test method does not have any physical effect on cosmetic products, a prohibition based on whether or not ingredients have been tested on animals, and which applies irrespective of whether such products have been manufactured in the Community or imported from third countries, could be considered to be contrary to WTO rules.

UK Parliament. (2002, January 13). Select Committee on European Scrutiny Sixteenth Report. Retrieved from https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200102/cmselect/cmeuleg/152-xvi/15202.htm [accessed 02 September 2020]

The bans were passed subsequently, effectively barring the entry of imported products. Over time, the interpretation of the exceptions of WTO law has evolved, and there is no significant resistance against measures banning testing on animals. In any event, these bans could possibly pass the test of WTO legality, based on the “public-morals” exception explained above with respect to seal products.

b. Rules banning import of harmful goods:

States can adopt measures seeking to reduce the entry of harmful goods into their territory. In so doing, they create a trade barrier, and must justify the restriction. For example, Brazil prohibited the import of refurbished tyres, which have a shorter lifespan and therefore cause a quicker accumulation of tyres in landfills. Since mosquitoes use the stagnating water gathered inside discarded tyres to breed, the disposal rate of tyres had direct effects on public health (more tyres lead ultimately to a quicker spread of mosquito-borne diseases, like malaria). The restriction was challenged before the WTO. The review body agreed that it was necessary to protect public health. However, the measure was considered discriminatory, because it did not bar the importation of refurbished tyres from Uruguay. Ultimately, the Dispute Settlement Body (DSB) of the WTO asked Brazil to remove the ban, or extend it to all imported tyres. 1

Other examples of import bans premised on the protection of public interests are the ban on UK beef imports that many states introduced after the outbreak of BSE in 19962 and the ban on pollutant waste adopted by China in 2017.3

These bans are considered lawful as long as they treat the manufacturers of each country – including the home country or territory – the same, without relying on artificial distinctions that might harbour a protectionist design.

c. Rules on marketing and certification schemes:

States can regulate and restrict marketing strategies to pursue public goals, and these restrictions can affect the flow of imported goods. For instance, the US created a certification scheme whereby the “Dolphin Safe” label could only be applied to tuna fished with specific safeguards to avoid the bycatch of dolphins. Mexico challenged the scheme, as a barrier to the importation and sale of Mexican tuna, and the WTO requested that the US amend its certification scheme to ensure that differential treatment of goods was based on the environmental goal, not on the producing country. It was permissible that the scheme would ultimately distinguish between products, to the detriment of tuna that was not considered dolphin-safe and therefore not eligible for the certification. However, it was necessary to demonstrate that eligibility under the scheme related truly to the purpose of the measure, distinguishing because of environmental harmfulness, not to exclude non-US products from the market.1

d. Prohibited goods:

States can prohibit the production, sale and use of certain products, irrespective of the place of manufacturing. Total bans have the obvious effect of precluding imports. For instance, France prohibited in 1999 the use of construction materials containing asbestos, and overcame a challenge brought by Canada under the WTO rules, invoking the protection of human health as a justification, even if incidentally the ban resulted in a disadvantage for Canadian manufacturer of asbestos products, and might have favoured EU-based manufacturers of substitutable construction materials which did not contain asbestos.

Likewise, the EU has banned single-use plastics1 and the UK adopted a similar domestic ban, which will enter into force in October 2020. Many States have banned cultivation and imports of genetically-modified foodstuffs. States that do not have the same environmental measures may not consider these goods harmful and might challenge the banning country for raising an unnecessary barrier to trade. The dispute settlement system of the WTO – or of an FTA – will then scrutinise the justifications offered by the importing country, to determine whether they are covered by some exception in the treaties, for instance on environmental grounds.

e. Green subsidies:

States can provide financial support to manufacturers of environmental goods, like solar panels, or to the producers of renewable energy. These measures are difficult to challenge per se, but when they benefit only local producers, under WTO rules foreign producers can complain of discrimination. For instance, India successfully challenged a US scheme before the WTO that provided subsidies to generators of renewable energy, which was conditional on using locally produced components. This practice is widespread, and India itself had done the same in the past. Both the US and India were ordered to remove the requirements to use domestic components from their benefit schemes.

Another form of green subsidies are environmental support schemes for agriculture, or agri-environment schemes. Traditional agri-environment schemes have been in place, in Scotland and across the EU, as part of the Common Agricultural Policy for some years, where farmers are paid for managing the environment. In the field of agricultural products, exceptionally, WTO law permits the payment of subsidies, including those that can restrict international trade, under certain conditions and within certain maximum amounts. Schemes providing support for producers depending on environmental performance qualify as so-called “green-box” subsidies, and are permissible and unrestricted as they are considered to “not distort trade, or at most cause minimal distortion”1. Therefore, subsidy schemes rewarding sustainable agriculture are possible.

f. Other environmental measures:

Environmentally harmful goods can be subject to other measures. For instance, France removed a tax break on palm oil biofuels, prompting a claim of discrimination by states exporting palm oil - this is still pending1. The WTO-legality of this French measure will depend, among other things, on whether it will be considered to address proportionately the targeted environmental harm (the destruction of forests to obtain agricultural land to grow biofuels) and treat all countries alike (without targeting Indonesia and Malaysia unfairly, leaving alone other countries that produce biofuels in similar ways).

g. Dual tariffs:

The UK briefly considered the possibility to impose higher tariffs on goods from countries with poor environmental standards1. Such tariffs would certainly be challenged under the most-favoured nation principle. While tariffs above the level bound by the WTO would be unlawful, it would be possible to lower tariffs on certain environmentally-friendly goods (for instance: tuna caught whilst sparing other species) and retain the higher rate on the harmful ones. This approach too could be challenged, when the two categories of goods are ultimately in competition with each other, and only differ in the way they are prepared/produced (for instance: ordinary tuna and dolphin-friendly tuna). Under WTO law, a discrimination challenge can be overcome if the measure seeks to combat the depletion of exhaustible natural resources and is accompanied by an internal equivalent measure. On matters of wider environmental interest (for instance, animal welfare), no specific justification is available, and a state must demonstrate that the sub-standard products undermine the public morals of its citizens, as explained above.

h. Lawful tariffs:

Tariffs on foreign goods, which are not ostensibly aimed at environmental protection, can shield the local industry from cheap goods produced in accordance with looser standards. Lowering those tariffs, therefore, can have the effect of opening the local market to “low-quality” competitors. The objection to tariff-cutting can be tinged with environmental concerns, as in the case of objections to the supposed drop in agricultural tariffs that the UK might offer to the US1. Conversely, higher tariffs can be invoked for environmental purposes, for instance to protect producers from cheaper imported products (see the example of egg producers below in part 4).2

A government might consider using tariffs to force a level playing field when regulatory coordination is impossible: the tariff artificially inflates the marketing costs of a foreign product when the domestic competitor must face other regulatory costs. However, tariffs cannot be discriminatory (under the WTO principle of most-favoured nation), and therefore higher tariffs on specific goods must apply to all countries. Furthermore, even in a preferential relationship (such as an FTA) tariffs can be lowered between the two countries, but not increased: if the UK and the US conclude an FTA, raising custom duties on certain US goods is not an option.

3.2 Impact on domestic and international trade: managing the regulatory floor

The rules of the WTO and most FTAs prohibit discrimination based on the goods’ origin and do not allow tariffs exceeding a fixed rate – which is often zero in FTAs. Normally, imports do not face direct discrimination and unlawful tariff rates. However, these are not the only trade barriers that they could face.

Regulation, including environmental measures, can result in a non-tariff obstacle to imports, or in a competitive disadvantage for domestic producers:

Environmental measures, as explained above, can at times create an obstacle to the importation of foreign goods, producing discriminatory effects. Sometimes, the environmental measure simply results in a burden imposed on foreign goods (for instance: marketing restrictions and labelling requirements).

Environmental measures regulating the production process do not apply to imports which, upon importation, cross the border as final products. Therefore, production-related restrictions create a compliance cost only for the local industry, putting it at a disadvantage. For example, a law prohibiting the use of a certain chemical in agriculture is likely to affect domestic production, but cannot apply abroad. Therefore, this measure is likely to favour imported agricultural goods from places without restrictions, which could be produced more cheaply and therefore can undercut local prices. This environmental measure, if anything, would increase international trade. It would also affect negatively the domestic producers, unless it is accompanied by a restriction of imports, or an FTA containing level playing field arrangements, which can force the exporting country to adopt measures with similar goals (and comparable compliance costs).

Box 2: How diverging standards can affect international trade:

Local standards can constitute trade barriers (domestic floor is higher). Example: if state A bans battery eggs altogether (i.e. eggs from hens kept in small cages with little room for movement), foreign producers of battery eggs and egg-products cannot sell their goods into A’s market, and other states might challenge A’s measure on the grounds that the regulatory floor is unjustifiably high and forecloses market access for imported products, discriminating against them. Demonstrating that the standard is upheld internally too is necessary but insufficient to justify the restriction. Absent any demonstrable risk for human health or public morals addressed by the ban, the importing country is likely to lose that challenge, and might be forced to resort to a less restrictive measure, like labelling.

Local standards can expose the local industry to increased competition by cheaper imports (foreign floor is lower). Example: if country A bans battery egg production, but does not ban the marketing of battery eggs and egg products, country A’s producers will suffer from the competition of cheaper products from country B, where the same standard does not apply. This was the scenario in the EU, when testing on animals was prohibited on the EU territory, but imported cosmetics could be marketed irrespective of their production methods. The local industry will object to this scenario, indicating the lower regulatory floor of B as the reason for an unfair competitive dynamic. Obviously, this scenario creates no harm to international trade, quite the opposite. The government of the importing country A might anticipate this risk and conclude with B an agreement whereby both countries will maintain similar standards. In case of violation, country A might be entitled to impose tariffs.

3.3 Environmental provisions in FTAs

Modern FTAs contain dedicated provisions on environmental protection. Interpreting these provisions is crucial to assessing domestic environmental measures holistically, rather than only for their trade-restricting potential.

Modern FTAs also contain sections on sustainable development, which do not concern trade liberalisation directly. These sections seek to achieve two goals: they indicate the parties’ understanding that the process of economic integration and development within the FTA must be socially sustainable and not come at the cost of harming the environment and other social goods. Moreover, they try to prevent each FTA party from free-riding on the other party’s commitment to environmental protection, by loosening its domestic rules to give a competitive advantage to its national producers.

However, these treaties tend to encourage the upholding of environmental standards, rather than justify the adoption of trade-restricting measures. In other words, FTA provisions on environmental protection tend to start from the assumption that the trade obligations will be observed. These FTA provisions are not particularly helpful to safeguard the policy space to implement ambitious environmental measures. The spirit of these provisions is to reinforce the minimum level of protection, to prevent a race to the bottom; typically, trade agreements do not safeguard the efforts of a government that wants to achieve a higher level of environmental protection.

The UK draft for the EU-UK FTA1 contains a dedicated chapter on Trade and Environment (Chapter 28). It acknowledges each party’s right to “set its environmental priorities” but always in a manner consistent with the trade rules of the agreement (Article 28.3). The parties confirm their commitment to observe existing international obligations (Article 28.4) and promise to apply their current laws (Article 28.5). In case of controversy, if consultations fail to produce an amicable solution (Article 28.13), a Panel shall hear the dispute and issue non-binding recommendations (Article 28.14).

The document published in March 2020 by the UK government, outlining its negotiation approach to a US-UK agreement, adopts a similar approach to the regulation of environmental measures.2 The official position is that the UK will not “compromis[e] on … high environmental protection, animal welfare and food standards.” This non-retrogression policy would result in “measures which allow the UK to maintain the integrity, and provide meaningful protection, of the UK’s world-leading environmental and labour standards.” There is no further specification. However, a dedicated section of this document, devoted to the impact-assessment analysis2 cautions that environmental degradation may result from an increase in pollution caused by higher manufacturing production and increased trade flows.

3.4 Trade and the EU push towards stricter environmental standards

The EU exercises the competence on environmental protection on behalf of its Member States, and does so quite actively. The EU is furthermore planning to continue its regulatory activity in the near future.

First, the EU continuously advances its environmental policies, adopting new product standards, which may result in trade restrictions. This prospect raises the question of whether the UK will decide to keep pace in each case. Second, based on its previous trade negotiations, it can be safely assumed that the EU will insist on level playing field clauses in future FTAs, or justification provisions, with the aim of guaranteeing the viability of its environmental measures and prevent them from turning into a burden for EU based industry.

The EU has not hesitated to pass environmental measures that indirectly restrict harmful trade. For example (alongside Australia, Japan and the US), it has instituted a system to verify the legality of imported forest products, in order to address concerns over forest loss in the tropics. In particular, the EU established a licensing scheme to ensure that only timber products that have been legally produced in accordance with the national legislation of the producing country enter the EU market. The scheme requires that imports of timber products originating in partner countries be covered by a license. The scheme furthermore lays down detailed provisions relating to the conditions for the acceptance of the licence, and for the application of the system of imports of timber products.1

More generally, the EU plans to bolster its due diligence requirements for corporate actors. On 29 April 2020, the European Commission announced that it will introduce mandatory rules requiring businesses to undertake due diligence to mitigate human rights and environmental harm in their supply chains across EU Member States. The rules will form part of the EU’s European Green Deal strategy and its response to the COVID-19 emergency. The rules were announced by the EU Commissioner for Justice, Didier Reynders, during a webinar hosted by the European Parliament Working Group on Responsible Business Conduct. The announcement was preceded by the publication of a study commissioned by the European Commission, which found that existing measures (which are mostly voluntary) have not satisfactorily addressed human rights violations and environmental harm arising in supply chains. Commissioner Reynders said that the new rules will be mandatory and enforceable through sanctions for non-compliance.

As explained above – raising standards might expose the local industry to compliance costs. These costs might translate into a competitive burden if there is no mechanism to impose the same due diligence duties on foreign firms competing on the internal market. A briefing prepared by the Human Rights subcommittee of the EU Parliament noted that the upcoming legislation on due diligence:

… should apply to companies domiciled in an EU Member State and also to those companies placing products or providing services in the internal market. Otherwise, EU companies bound by the rules will be competing with non-EU companies not subject to the same due diligence obligations.

European Parliament. (2020, June). Human Rights Due Diligence Legislation - Options for the EU. Retrieved from https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2020/603495/EXPO_BRI(2020)603495_EN.pdf [accessed 02 September 2020]

Additionally, the EU’s Green Deal also includes plans to adopt a carbon border adjustment mechanism. This mechanism would permit EU states to levy (“adjust”) at the border a carbon-related price (tariff or tax) on goods imported from non-EU countries with lax climate policies. The targeted goods are those that have (or are presumed to have) been produced in a way that would not be permissible or would be penalised under the EU pollution policies and standards.

This scheme, essentially, would address two issues: the lack of a level playing field (causing trade harm to the more responsible industry) and the related problem of carbon ‘leakage’, i.e. when a country adopts more stringent measures to combat climate change, production can simply move abroad, thus frustrating the environmental goal of the measure. The scheme would not start until at least 2021 and must be compatible with WTO rules.

Finally, in March 2020, the EU adopted the Circular Economy Action Plan, which is also part of the European Green Deal. The plan envisages legislative and non-legislative measures regarding the life cycle of products, with an emphasis on repair, reuse and recycling, to reduce the EU’s consumption of resources.

The “key objectives” of the plan include:

Mainstreaming circular economy objectives in free trade agreements, in other bilateral, regional and multilateral processes and agreements, and in EU external policy funding instruments.

Measures required to implement the Circular Economy Action Plan might influence the negotiation of an FTA in the two ways. First, the plan to adopt trade-restrictive measures might cause the EU to insert specific justifications in the FTA, for instance a right to raise the regulatory floor without worrying about the trade consequences. Second, the plan to adopt more stringent and costly standards on the EU industry might cause the EU to insist for level playing field guarantees in the FTA, for instance a promise by trade partners that they will also raise the regulatory floor.

4. Case-studies: interactions between trade rules and environment, animal welfare and food safety ambitions

Thus far, this briefing has outlined the theoretical interactions between trade rules and environmental standards and discussed some examples from around the world of how these have been utilised. This section considers case studies of the interactions between trade and environmental, animal welfare and food safety standards. We use trade in eggs and egg products as an in-depth case study to illustrate these interactions. Secondly, we provide more detail on the interaction between trade and product standards in the much-discussed example of chlorinated chicken.

The remaining three case studies discuss environmental issues that the Scottish Government have stated an ambition to address, with a view to ascertain whether measures could be hindered by international trade obligations, or whether they might have an adverse impact on the local industry. As noted above, international trade is reserved to the UK Government, whilst environmental policy is devolved to the Scottish Parliament . Therefore, Scotland has the power to introduce environmental measures, but may be restricted, either directly or indirectly, by trade agreements struck at UK-level.

4.1 Trade in eggs and egg products – interaction between trade and animal welfare standards

Of all eggs consumed in the UK – around 13 million per year – the majority are produced locally, while some 2 million are imported. Eggs sold in shell are not typically imported, as their transport is impractical, while processed egg products are easily traded internationally.

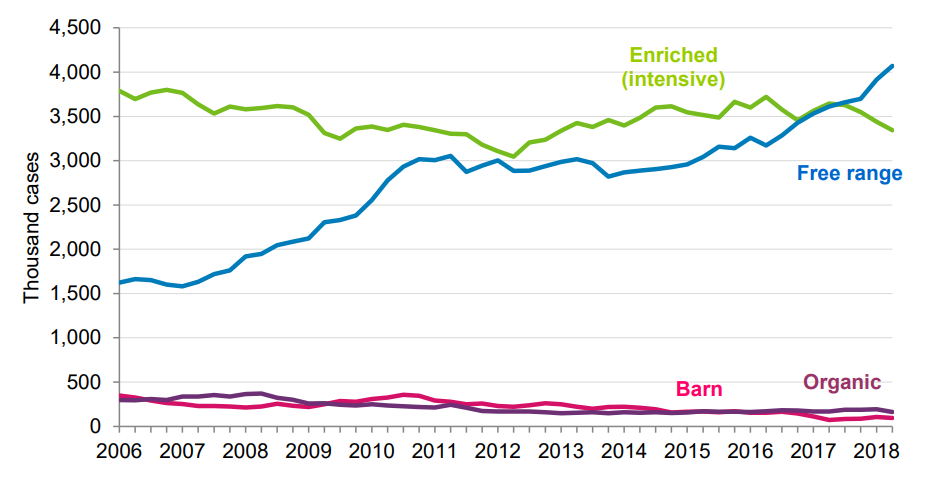

In the EU, battery production has been prohibited since 2012. Apart from a small quota of barn and organic eggs, the UK market is evenly split between eggs by caged hens and free range, with the latter growing. UK producers complying with EU rules and animal welfare standards sustain higher production costs than non-EU producers using battery hens.

Source: UK Government1

Eggs are traded without custom duties between the UK and the EU27. Trade in eggs is free from tariffs also between the EU and third countries that have FTAs with the EU. However, the EU has included animal welfare standards in their recent trade deals, therefore duty-free access for foreign eggs depends on compliance with EU-like standards. The EU imposes a tariff of 30.4€/100Kg on eggs from third countries (countries with which it has no trade deal, like Argentina or the USA), on top of a tariff quota (where a certain amount can be imported at a lower tariff rate) of 15.2€/100Kg. Tariffs on processed eggs can be much higher: dried yolks face a 142.3€/100Kg tariff on top of a tariff quota of 71.1€/100Kg. In spite of the Association Agreement between Ukraine and the EU, trade in eggs is considered too sensitive to warrant full liberalisation. Accordingly, the same tariff applicable to eggs imported from third countries applies to Ukrainian eggs above a limited tariff-free quota.

| From third countries (including the UK without a deal after 2020) | From another EU Member State | From a country with which the EU has a FTA or a development cooperation scheme | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eggs | 30.4€/100Kg | 0 | 0 |

| Dried yolks | 142.3€/100Kg | 0 | 0 |

The EU, for the most part, does not impose animal welfare standards on imports, because they could be considered discriminatory and could be challenged under WTO law. The main reason why the EU markets are not captured by cheaper foreign eggs is that the applicable tariffs make them more costly when they cross the border. This is therefore an example, like those discussed in section 3, above, where lawful tariffs have been used to safeguard the competitiveness of an environmental-friendly product against competing products produced in environmentally-harmful ways.

After the end of the implementation period in December 2020 and in case it does not manage to agree an FTA with the EU, the UK will adopt a tariff scheme, published in May 2020, which roughly replicates the current EU tariff (25GBP/100Kg). The UK had previously proposed to drop tariffs on most goods, including eggs and processed egg products. This scheme was discarded, as it was felt it had been prepared without sufficient consultation with the local stakeholders, and would have exposed some domestic industries to a sudden competitive pressure from foreign products – not so much those from the EU, which after all have not faced tariffs for decades, but from all other countries. For instance, foreign egg-products from China or Brazil would have entered the UK market at no additional cost. However, in both scenarios, EU custom duties would apply to UK eggs sold into the EU market.

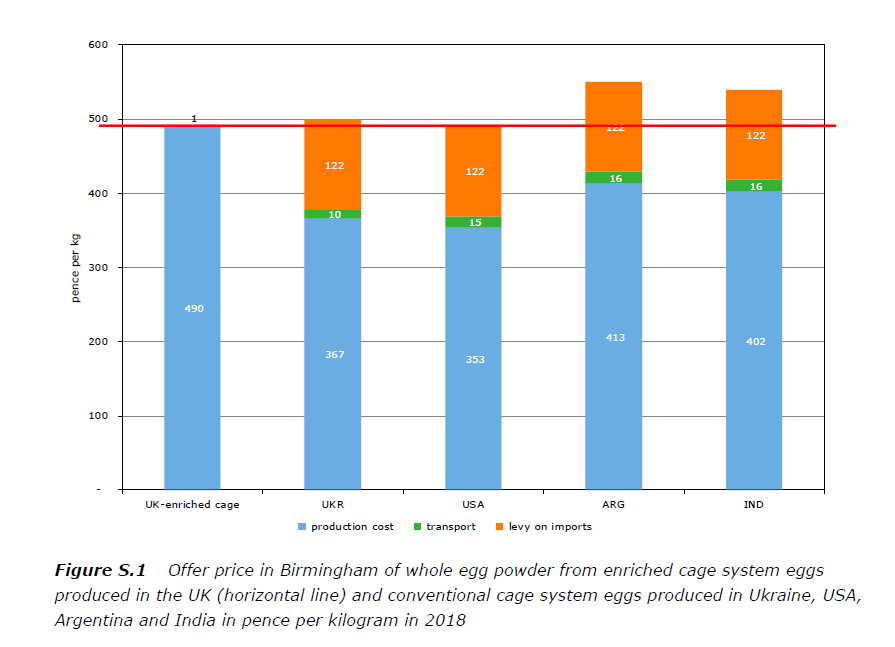

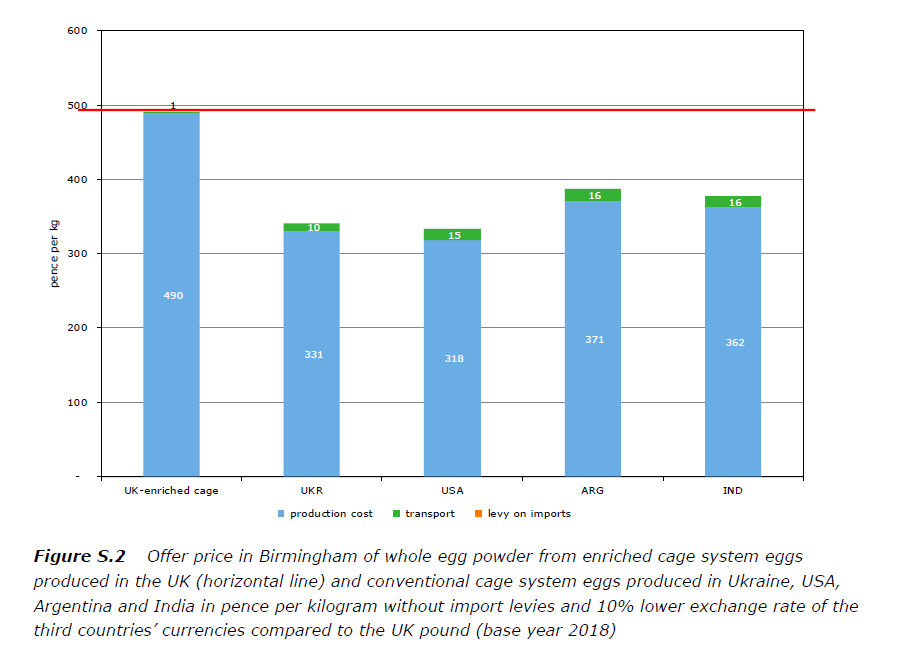

Domestic regulations implementing this EU law will initially continue at the end of the implementation period subject to changes made to correct deficiencies in those regulations as they apply in retained EU law. Subsequently, the UK administrations will be free to retain, change or discard these rules inherited from EU law. If the UK decides to retain current animal welfare standards, however, it would need to retain a custom duty at the border (see figure below, custom duty in orange) to protect the local industry from competition from outside the EU. The lower production costs of imported battery eggs from outside the EU would otherwise undercut the price of local eggs. See Figure S.1, and compare it with Figure S.2, below.

The cost of feed is also a variable that can affect the income-per-bird calculation. The production costs could rise if the price of the components of bird feed goes up due to imposition of tariffs on imported grains like wheat, barley, and soymeal.

As noted above, WTO law prohibits, in principle, barriers based on the method of preparation and processing of goods which do not result in differences in the final products, unless they relate to environmental conservation efforts or protect public morals. In the case of a no-deal Brexit, only tariffs would prevent cheap imported eggs and egg-products, produced in ways that would not be permitted under the EU standards in force now, from penetrating the UK market.

In FTA negotiations, removal of tariffs is the primary bargaining chip. It is fair to assume that both a potential UK-EU FTA and a potential UK-US FTA would create duty-free trade in eggs and egg-products between the UK and its trade partners. This prospect creates different follow-up issues that these FTAs would have to address:

Realistically, a trade deal with the EU will need to contain a level playing field guarantee that the UK and EU standards will not be lowered. Without such guarantee, the EU would be hesitant to conclude a deal removing tariffs, knowing that the UK could drop its standards and sell cheap sub-standard eggs across the EU single market.

Conversely, the success of a trade deal with the US depends on US producers obtaining market access to the UK market for their products without having to change their production methods. US battery eggs or egg products could therefore enter duty-free into the UK, whether or not the UK will retain the EU standards.

These scenarios do not necessarily exclude each other. It would be in theory possible for the UK to retain the current standards for its products (a precondition for the EU deal) and simply accept US goods complying with different ones (a precondition for the US). In this scenario, however, local producers would suffer the most: they would be subjected both to high-standard competition from the EU and low-standard competition from the US, with no tariffs on either class of products.

Consumers preferring free-range will be always able to check provenance when they buy eggs in the supermarket, and a dedicated labelling system can be established. However, price-sensitive industries (restaurants, school canteens) and food manufacturers might opt for the cheaper foreign inputs, unbeknownst to the final consumer. Furthermore, cheaper non-UK inputs in UK food products might make the latter ineligible for duty-free treatment under a UK-EU deal, or simply prohibited for failure to comply with EU standards.

4.2 Chlorine-washed chicken and industry-wide voluntary standards – interaction between trade and food safety standards

Even if the UK aligns with EU law standards (for instance, on the prohibition on battery eggs, chlorine-washed chicken or hormone-fed beef) it might be unable to apply these standards at the border to block non-conforming food, depending on the nature of its FTAs with other countries, such as the US. This, in turn, means that Scotland too would not be able to block non-conforming foods.

Standards for producing and processing foodstuff may or may not affect the final characteristics of the products. For instance, a prohibition to use certain pesticides causes lower levels of harmful residue in the vegetables. In contrast, it is impossible to tell which can of tuna comes from sustainable fishing, or which cosmetic product was not tested on animals. Countries can adopt standards of the first kind to pursue public interests like environmental protection, irrespective of the trade restriction that might occur. However, standards that do not relate to the characteristics of the products cannot be used to discriminate between similar goods, unless there is a justification related to a social value, such as conservation of exhaustible resources, human and animal health, or public morals.

In certain cases, it is unclear whether a certain method of processing and production has any effect on the ultimate qualities of the product: this is the case for instance of genetically-modified foodstuffs, hormone-fed beef and chlorine-washed chicken. The US regulator does not consider that these methods have any salient effect on the final product, in terms of risk for human health. The EU regulator, while unable to point to any practical evidence of risk for health, considers these processes potentially harmful and prefers to ban them out of precaution.

For example, local hormone-free beef meat cannot be favoured over foreign hormone-fed beef meat through a selective hormone-specific ban, tax or tariff - that is, an extra hormone-specific tariff, on top of any generic and legitimate tariff on beef. EU hormone bans have been successfully challenged by Canada, Argentina and the US under WTO law. The EU was able to negotiate an amicable arrangement with Canada and Argentina, but currently pays a hefty price to maintain its unlawful ban on US hormone meat, in the form of a generous increase of the quota of US (hormone-free) beef that can enter the EU single market duty-free. Conversely, some standards do not need to apply to imports since a lawful tariff will stifle imports anyway (battery eggs).

In 2009, the US also initiated a lawsuit against the EU before the WTO on chlorine-washed chicken, which is presently suspended – but not withdrawn.1 The US has put its challenge on the chlorine-washed chicken on hold, in the context of a wider composition of mutual trade interests.

After EU exit, and irrespective of whether there will be an FTA with the US, the UK could be challenged for retaining these bans. It might not be sufficient for the UK to confirm its share of the US meat quota to fend off new challenges of the hormone ban, and it is possible that what has kept the US from going after the EU’s ban on chlorine-wash will not keep the US from going after the UK.

If environmental standards are softened on imports, but retained on the local industry, UK products could be undercut by foreign cheaper products with lower compliance costs.

The penetration into the UK market of foodstuff that is widely perceived as substandard might be mitigated by voluntary conduct, for instance decisions by retailers not to stock certain products. For instance, on 25 June 2020 Waitrose announced that it will never stock chlorinated chicken, and other retailers made similar declarations.2 Waitrose’s managing director promised:

We will never sell any Waitrose product that does not meet our own high standards, … any regression from the standards we have pioneered for the last 30 years would be an unacceptable backwards step.

…It would be simply wrong to maintain high standards at home yet import food from overseas that has been produced to lower standards. … We would be closing our eyes to a problem that exists in another part of the world and to animals who are out of our sight and our minds.3

Similar strategies – mostly driven by business considerations – have been adopted in the past by supermarket chains, which have announced total or near total bans on GM foodstuff or even products from pigs or poultry fed with GM animal feeds.4 Likewise, some UK supermarkets refuse to stock eggs of laying hens kept in cages, and many have made at least a commitment to stop doing so by 2025.5

These voluntary choices, alone, would be unlikely to limit the circulation of lawful products completely. Smaller retailers might choose to stock the foreign products, if available, to offer a low-price option to their clients. Moreover, sometimes it is impossible or impracticable to verify the method of production of foodstuff when it is processed into a composite final product, or when it is used in the preparation of food served in restaurants and canteens. Commentators have also pointed out how relying on consumers’ discretion alone, through labelling, might be insufficient:

Under current EU rules, the chlorine wash is classed as a processing aid rather than an ingredient and so wouldn’t have to be declared on the packaging. This means UK consumers would be unlikely to know whether imported US chicken had been through the chlorination process unless it was voluntarily declared. Of course, once the UK leaves the EU, it would be free to change the rules. But that doesn’t mean it necessarily would.

The Conversation. (2017, August 2). Chlorine-washed chicken Q&A: food safety expert explains why US poultry is banned in the EU. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/chlorine-washed-chicken-qanda-food-safety-expert-explains-why-us-poultry-is-banned-in-the-eu-81921 [accessed 2 September 2020]

4.3 Scottish environmental ambitions and potential interactions with trade rules

The following three examples take potential Scottish Government interventions on the environment, and analyse potential measures in the context of trade rules.

4.3.1 Peat extraction and use

Peatlands can store a significant amount of carbon dioxide and, therefore, their degradation and depletion for commercial use contradict public efforts to mitigate climate change.1 Peat is mostly used to produce compost for gardeners and growers and, in small amounts, it is used also in the whisky industry, and as heating fuel in some rural areas.

After it transpired that the UK and Scotland do not keep an up to date record of peat extraction, the Scottish Government has committed to “phasing out the use of peat for horticultural purposes.”2 The 2019-20 Scottish Government Programme states:

This year we are investing a total of £14 million to fund projects to restore degraded peatlands. To address activity that impacts some of our peatlands and reduces their carbon store, we will seek to phase out the use of horticultural peat by increasing uptake of alternative growing media substrate.

While the Scottish Government has not yet set a date for phasing out the use of peat, the UK Committee on Climate Change (a statutory body established under the UK Climate Change Act of 2008) recommended that the extraction of peat for all uses cease by 2023, and that there be “an accompanying ban on the sales of peat given that two-thirds are imported, mainly from Ireland.”3

So far, no concrete proposals have been made and therefore here we merely consider different scenarios of how a peat ban would fare under current and future trade obligations. The scenarios are divided into Scotland-specific measures (a and b) and UK-wide measures (c).

a) A local ban on production (extraction and processing)

The Scottish Government does have the power to ban peat extraction and/or processing in Scotland. A domestic ban on peat extraction would of course halt the degradation of peatlands in Scotland but may not affect international trade of peat or products prepared with peat combustion. On the contrary, in the wake of a local extraction ban, peat compost and peated whisky from the rest of the UK or from third countries would probably increase their sales in Scotland at the expense of the local industry. If an extraction ban is not accompanied by a ban on processing, the Scottish manufacturers of peat compost and peated whisky could continue their operations, importing raw peat from outside Scotland, for processing. A Scottish ban on extraction and processing could force the domestic peat-based industry to shut down.

A Scottish ban on extraction and/or use of peat may lead to “carbon leakage”: a prohibition imposed at the local level might simply lead to an increase of production elsewhere, frustrating the pursuit of the environmental goal at the international level. In other words, producers of peat compost and whiskies could relocate their production process elsewhere, where extraction and/or processing of peat is lawful, and sell the final products on the Scottish market.

The ultimate effects of a local production ban would therefore be dubious: the environmental gains could be frustrated by carbon leakage (more peat would be extracted or processed outside Scotland); the hit taken by the domestic industry could open opportunities for outside competitors; peat-based products could still be sold locally.

b) A local ban on production and marketing

In the alternative, Scotland could decide to adopt, together with a production ban, a marketing ban, outlawing also the sale of peat and peat-based products. In principle, this measure would have a better environmental impact and would not trigger the replacement of Scottish products with outside competing goods. However, the legality of a Scottish-only ban on marketing would be controversial. First, a marketing ban would render importation of peat-based products possible in the abstract but pointless in practice. In effect, a marketing ban has on imported goods an effect equivalent to a quantitative restriction at the border (an import ban). Scotland does not have the power to impose external trade measures. Second, the marketing prohibition would likewise create a clear intra-UK disparity: it would prohibit the sale in Scotland of peat-based products regularly produced and marketed in the other nations.

In other words, it would be very hard for Scotland to remedy the detrimental effects of a production ban (carbon leakage and harm to the local industry) through a marketing ban. A Scotland-only marketing ban might encounter challenges from within and without the UK.

c) A UK-wide ban

The UK, conversely, could adopt an import ban on all peat-based products. Such an import ban could be justified, as the WTO allows restrictions based on the protection of exhaustible natural resources, and peat is certainly one.

WTO law imposes a condition for the legality of such bans. That is, environmental restrictions should be made effective “in conjunction with restrictions on domestic production and consumptions” (Art. XX(e) General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade). Accordingly, a UK-wide import ban should be accompanied by an internal ban on production and marketing.

On this latter aspect, the UK has already taken some steps. The UK Government has committed to phasing out the use of horticultural peat in England by 2030, and the National Planning Policy Framework for England does not allow for granting new licenses for peat extraction. The UK’s plan does not expressly mention the possibility of a restriction on imports, but acknowledges the limited effects of an internal ban, and the need to curb imports:

Two thirds of the peat sold in the UK is imported from Europe, so it is also important that we focus on reducing the demand for peat in horticulture to also protect peatland outside of the UK.

UK Parliament. (n.d.) Petition: Ban peat compost. Retrieved from https://petition.parliament.uk/archived/petitions/263362 [accessed 02 September 2020]

The language is clear in identifying the environmental goal (protection of peatlands abroad, to prevent leakage) but is ambiguous on how to achieve it. To “reduce [domestic] demand” for foreign peat is not the same as banning its importation, which would rather cut the supply. In other words, the UK is not yet expressing the intention to accompany the internal prohibition of production and sale with an external trade measure (a ban). Should such measure materialise, it would be justifiable under the terms of WTO law and of a typical FTA that includes environmental exceptions.

4.3.2 Waste reduction measures

A number of waste reduction measures have been proposed. The Scottish Government tabled a Circular Economy Bill proposal in late 2019. The Bill included the power to introduce a charge on single-use disposable items (like beverage cups) and mandatory public reporting of unwanted surplus stock and waste of certain materials by Scottish businesses. The proposal was put on hold in April 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the Deposit Return Scheme, which is set to be implemented starting in 2022, already places some responsibility on businesses for the recycling of bottles. The adoption of measures such as these may have repercussions on the free circulation of products in the UK internal market unless reasonable flexibility is exercised, which is explored further below.

Other circular economy measures are being developed in collaboration with the UK Government and the other devolved administrations. A UK-wide reform of packaging regulations through a revised extended producer responsibility scheme (EPR) may soon make producers liable to pay the full cost of dealing with packaging waste while stimulating investment in collection, sorting and reprocessing. The adoption of measures such as these may have repercussions on the free circulation of products entering the UK from its trading partners.

Charges on disposable items (like a sales tax) do not raise issues under WTO law or under the typical provisions of FTAs. These charges have the precise goal to make disposable products more costly, and encourage reliance on reusable alternatives. Domestic and foreign producers would be equally affected by this competitive setback, with no direct discriminatory effect based on their origins. Foreign producers of disposable items might claim that the charge is indirectly discriminatory (since it would give an advantage to the local industry of reusable items), but international trade law (WTO and FTAs alike) justifies discriminations that result from a rational application of a measure aimed at preserving exhaustible resources (energy, water, trees, clean air, fertile soil).

It is important, however, that the charge is shown to have at least a reasonable chance to make a contribution to the protection of the environment. For instance, the measure must be designed to prevent unintended harmful effects that contradict its purpose. Conversely, ineffective restrictions can be challenged under WTO and FTA provisions. During the public consultation concerning the Circular Economy Bill, it was noted:

Any action to reduce the use of single-use items (including environmental charging) needs to go hand-in-hand with requirements on manufacturers / producers to design products that can be easily recycled. Action will be needed to prevent producers switching to alternative packaging that is less recyclable than plastic.

…

no additional items should be considered for environmental charging until there is robust evidence that such charges are effective at driving changes in consumer behaviour

…

focus for any future charges should be on non-recyclable / hard-to-recycle items rather than items which are ‘single-use’ but can be recycled. Items which are infinitely recyclable (glass and aluminium) should not be included in any environmental charging scheme.

Scottish Government. (2019, November 7). Developing Scotland's circular economy: consultation on proposals for legislation. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/delivering-scotlands-circular-economy-proposals-legislation/pages/5/ [accessed 2 September 2020]

Domestic measures, besides being effective, must be relatively flexible, to accommodate foreign standards that are equally effective. Unreasonably rigid measures can be deemed to constitute trade obstacles. A classic example, with respect to packaging standards, is the case of the Danish system for recycling bottles. The European Court of Justice (ECJ) found that the protection of the environment constitutes one of the EU’s essential objectives and was an acceptable ground to restrict the entry of goods from other Member States. It accordingly upheld the national legislation, apart from the requirement that only prescribed types of containers could be used, which the ECJ considered to fall foul of the principle of proportionality. This was because the measure did not allow for the possibility that foreign manufacturers use containers that, while not being pre-approved by the Danish authorities, were equally returnable and, therefore, presumably equally capable of serving the environmental goal. This requirement of reasonable flexibility may become relevant in discussions on the UK internal market, vis-à-vis the implementation of measures, like the Deposit Return Scheme for single-use drinks containers.

4.3.3 The right to repair

Within the wider context of its circular economy plan, the EU is considering taking measures to increase the lifespan of products through maintenance and repair.1 In its implementation calendar the EU has planned to take “legislative and non-legislative measures establishing a new right to repair” in 2021. As part of its consultation on circular economy legislation, the Scottish Government has suggested that it intends to align with and transpose the EU circular economy package2; as such this policy intention on the right to repair is discussed in theory in relation to the EU’s proposals.

The EU explicitly committed to guaranteeing that consumers have precise information on the products’ lifespan and the availability of spare parts, repair services and repair manuals. It also plans to establish “minimum requirements for sustainability labels/logos and for information tools” and new rights for consumers to obtain spare parts and find repair and upgrade services. The EU also plans to enhance the standards that products must satisfy to obtain the EU Ecolabel certificate, a certification scheme that signals low environmental impact.

These policy goals can be achieved through a series of measures, some binding, some voluntary, including: binding labelling and information requirements, technical voluntary standards, as well as the obligation for manufacturers to guarantee certain post-sale services. Alternatively, a subsidy could be offered to businesses engaged in the refurbishment of used products.

Zero Waste Scotland, a non-profit organisation funded by the Scottish Government, has outlined “incentivised return”3 offering financial incentives to refurbishing businesses, as one of a number of circular economy business models.4 Public support to service providers, however, must be granted in a non-discriminatory way in order to not fall foul of trade rules, such as in the example of the US and India’s green subsidies for renewables. Since the UK seeks to roll-over its membership in the Government Procurement Agreement of the WTO, public contracts in the field of “maintaining and repair services”5 will have to be offered to foreign contractors too.

In general, Scotland can adopt environmental measures of the kind described, with two caveats relating to a potential disparity of standards between Scotland and the rest of the UK.

Without a UK-wide standard, foreign products that do not meet the Scottish “repairability” standard could enter the UK and be sold on its market. Unless the devolved nations are empowered to restrict trade to pursue public objectives, the risk is that the Scottish standard would be frustrated by the continuing presence on the UK market of sub-standard goods. The Scottish scheme, ultimately, might be relatively unhelpful for the environment and damage Scottish producers, at the advantage of their competitors.

Conversely, a UK-wide regulation might be justified under WTO and FTA law, invoking the exception relating to the conservation of exhaustible natural resources.

5. Scotland: Devolution, trade and environmental standards

This briefing has explored theoretical interactions between trade and environmental regulations, and provided case study examples of challengeable and unchallengeable efforts to impose environmental regulations.

Scotland has committed to maintaining environmental, animal welfare, and food safety standards, which, under the status quo, are devolved competences. However, trade is reserved, and therefore, trade deals may be struck without Scottish standards and ambitions in mind, and Scotland is limited in its ability to control trade-related impacts. Scotland cannot change the rules on what is imported into the UK. However, it could set standards prohibiting the marketing of products in Scotland that do not comply with devolved requirements. The UK Government could also exercise their existing order-making powers under sections 35 and 58 of the Scotland Act to prohibit a Scottish Bill or an action of the Scottish Government which the Secretary of State has reasonable grounds to believe would be incompatible with any international obligations from becoming law. In the same vein, Scotland cannot set or remove tariffs on items coming to Scotland in order to maintain a level playing field.

Box 4: The UK internal market

EU exit requires a careful management and regulation of the so-called “UK internal market.”1 Once the UK is able to diverge from EU law on the environment at the end of the implementation period on 31 December, increased divergence between environmental standards within the UK may follow, and these local regulatory differences might in turn affect intra-UK trade, as the case of Northern Ireland has already illustrated.

As discussed above, a unilateral Scottish ban on marketing peat products, or a Scottish ban on single-use plastic, would have an impact on the UK internal market, and limit the circulation of goods within the UK market. Such regulatory fragmentation could create compliance and logistical costs for operators that want to conduct businesses across the various regulatory zones. It also could also put manufacturers subject to more stringent rules at a disadvantage vis-à-vis their competitors.

Responding to a call for views by the Finance and Constitution Committee of the Scottish Parliament, the Food and Drink Federation Scotland stated:

Differing regulatory standards for food manufacturing will create a significant disruption to the current food and drink supply chains. It would mean additional [stock keeping units] and labels within the same consignment, adding significant cost for business for additional storage, labels etc. The proliferation of distinct storage locations and additional transport could add to the environmental impact of food and drink products in the UK.

Food and Drink Federation Scotland. (n.d.) Written evidence submission to the Finance and Constitution Committee. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/S5_Finance/General%20Documents/submission_from_Food_and_Drink_Federation_Scotland_3.pdf [accessed 2 September 2020]

The National Farmers’ Union Scotland highlighted the importance to have common UK rules in several critical sectors:

The examples of policy areas which NFUS believe would be sensibly governed by a common framework would be pesticides, organic farming, fertilisers, animal health and traceability, marketing standards, food and feed safety, and food labelling.

National Farmers Union Scotland. (n.d.) Written evidence submission to the Finance and Constitution Committee. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/S5_Finance/General%20Documents/submission_from_NFU_Scotland_10.pdf [accessed 2 September 2020]

The UK Government published a white paper on the UK internal market on 16 July 2020,4 which has not been the result of negotiations with the devolved administrations. A detailed analysis of this document and the underlying issue exceeds the scope of this briefing. In brief, the UK might try to prevent regulatory fragmentation in at least two respects:

First, it could create a system of market access mutual recognition among the four nations, to maintain the circulation of goods across the whole UK. This arrangement would largely frustrate more stringent standards adopted locally, as sub-standard goods would have to be accepted from the other nations.

Professor Michael Keating notes, as part of the Centre on Constitutional Change’s response to the white paper on the UK internal market, notes:

The principle of mutual recognition is taken directly from EU practice. This means that an item that meets the regulatory standards in one part of the UK can be sold anywhere else in the UK. Yet, again, the context is different. The EU is a union of 27 countries, in which no country predominates. In the UK, England has 85 per cent of the population so that it will be English standards, set by the UK Government, that prevail. Some of these standards will be set so as to conclude trade deals with other countries, meaning that these imports will be freely available across the UK, whatever standards are set in Scotland and Wales.

University of Edinburgh Centre on Constitutional Change. (2020, July 17). Response: The Internal Market White Paper. Retrieved from https://www.centreonconstitutionalchange.ac.uk/news-and-opinion/response-internal-market-white-paper [accessed 2 September 2020]

Second, the UK Government may seek to impose additional constraints on devolved competence, or at least take action in devolved areas to facilitate the conclusion and implementation of international agreements. Jo Hunt, from the Centre on Constitutional Change at the University of Edinburgh notes:

Controversially from a devolution perspective, the UK government has argued for additional constraints over the exercise of devolved competence on the grounds that they are necessary in the interests of internal and international trade objectives. Though the power created by the EU (Withdrawal) Act 2018 to effectively freeze competence in areas covered by specific EU regulations has not yet been used, work is underway by government officials from across the UK on the creation of new regulatory common frameworks to replace those previously provided by EU law across matters such as animal health and welfare and food safety.6

The White Paper does not go into details about the possibility of intra-UK regulatory differences in the field of environmental protection. It lists (paragraphs 42-44) the UK achievements in this field, stating that the UK standards will be maintained after Brexit. The presumption is that environmental measures will be consistent across the UK, and consistency is cited among the catalysts for international trade:

Ensuring the UK remains a coherent and integrated economy will be key to fostering all the opportunities in trade.

The scenario outlined in the White Paper would rule out hypothetical obstacles to trade. However, the autonomy of the UK nations in environmental matters entails the possibility that regulations could diverge. The foreword to the White Paper, by the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, Alok Sharma, hints to the possibility of retaining local rules, but does not clarify how these rules – which certainly are susceptible to resulting in trade obstacles – can be implemented in spite of their trade-restrictive effects:

These principles [non-discrimination and mutual recognition] will not undermine devolution, they will simply prevent any part of the UK from blocking products or services from another part while protecting devolved powers to innovate, such as introducing plastic bag minimum pricing or introducing smoking bans.

5.1 The Scottish Government’s view

As noted above, the Scottish Government has expressed the ambition to maintain close ties with the EU, and continue to align with EU environmental standards after exit, when appropriate. The UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Continuity) (Scotland) Bill (‘the Continuity Bill’) introduced to Scottish Parliament in June 20201 is intended to allow the Scottish Parliament to "keep pace" with EU law in devolved areas, therefore hinting at a willingness to ensure dynamic alignment, whether or not an EU-UK FTA will require that.

The Bill published on 18 June 2020 aims to give powers to the Scottish Ministers to make provision (as outlined in Section 1(1)(a):

corresponding to an EU regulation, EU tertiary legislation or an EU decision,

for the enforcement of provision made under sub-paragraph (i) or otherwise to make it effective,

to implement an EU directive, or

modifying any provision of retained EU law relating to the enforcement or implementation of an EU regulation, EU tertiary legislation, an EU decision or an EU directive.