Health, Social Care and Sport Committee

Remote and Rural Healthcare Inquiry

Membership changes

There were 3 changes to the membership of the Committee during the inquiry:

On 7 November 2023, Ivan McKee MSP replaced Stephanie Callaghan MSP.

On 9 November 2023, Ruth Maguire MSP replaced Evelyn Tweed MSP.

On 18 June 2024, Joe FitzPatrick MSP replaced Ivan McKee MSP.

Summary of recommendations

Education and Training

The Committee wishes to highlight the extensive evidence it has received of the critical importance of local availability of suitable training and development opportunities to support recruitment and retention of the healthcare workforce in remote and rural areas. The Committee calls on the Scottish Government and NES, in responding to this report, to set out they are doing to improve the availability, suitability and flexibility of local training and development opportunities in remote and rural areas as a key component of their overall strategy for nurturing Scotland's remote and rural healthcare workforce.

The Committee notes evidence from multiple stakeholders that the development of "Earn as you learn" programmes in remote and rural areas could play an important role in increasing the prospective workforce in these areas and making those areas more attractive destinations for student placements. The Committee therefore calls on the Scottish Government to ensure that the development of such programmes and increased availability of such opportunities form an integral part of its forthcoming Remote and Rural Workforce Recruitment Strategy.

The Committee calls on the Scottish Government to address the concerns it has heard raised that training arrangements for staff seeking to work in remote and rural areas, particularly AHPs, lack flexibility to enable them to complete their training locally. In particular, the Scottish Government should work with professional bodies, training providers and NHS Boards to explore opportunities to condense training into a shorter time period and to provide training online so workers are not obliged to relocate to the central belt to complete their training, incurring additional time and cost commitments as a consequence.

More broadly, the Committee calls on the Scottish Government, Scottish universities and colleges, professional bodies, and NHS Boards to explore ways of offering more local training and development opportunities in remote and rural areas

Issues Around Recruitment and Retention

The Committee highlights the significant extent to which a lack of available affordable housing is acting as an indirect barrier to healthcare provision in remote and rural areas of Scotland by dissuading or making it practically impossible for healthcare workers to locate themselves within the remote and rural communities they would otherwise wish to serve. The Committee believes this is an issue that needs to be urgently discussed and addressed within relevant fora involving NHS Boards, local authorities, professional bodies, trade unions and other key stakeholders. There is an opportunity to learn from, and to disseminate more widely, local examples of good practice and innovative approaches to resolving this important issue, including:

Repurposing vacant local authority and NHS property to provide accommodation for healthcare workers;

Ensuring healthcare workers are appropriately prioritised within any wider plans to provide additional affordable housing for key workers;

Exploring options for generating additional revenue to be channelled towards provision of more affordable homes for key workers, including those working in healthcare;

Providing incentives for local residents, property owners and tourist accommodation providers to offer temporary accommodation to healthcare workers on placement, for instance through council tax rebates.

From the evidence it has heard during this inquiry, the Committee has also concluded that digital infrastructure has a crucial role to play in significantly improving the availability of appropriate training opportunities for the remote and rural healthcare workforce, for improving their quality of life and thereby making remote and rural areas a more attractive location in which to work, while also improving the quality and convenience of services provided to patients. The Committee therefore calls on the Scottish Government and the UK Government, in responding to this report, to set out the specific actions they are respectively taking to improve digital connectivity in remote and rural areas, how these actions will contribute to improving access to and availability of healthcare services and the anticipated timetable for implementation of any relevant plans and strategies.

Service Design and Delivery

The Committee calls on the Scottish Government in responding to this report to set out what it is doing to combat silo working in the delivery of remote and rural healthcare services, to promote a whole-system approach and to design services in a way that is more flexible and responsive to local needs and circumstances.

The Committee commends existing good practice in the provision of remote and rural healthcare services demonstrated by third sector organisations. It calls on the Scottish Government to set out what it is doing to systematically capture any such examples of good practice and to disseminate these more broadly across all remote and rural areas.

Primary Care and Multi-Disciplinary Teams (MDTs)

The Committee has heard extensive evidence throughout this inquiry of the specific challenges associated with implementing the 2018 GMS contract in remote and rural GP practices, in particular the practical challenges associated with trying to develop multi-disciplinary teams in remote and rural settings. It has also heard evidence of a growing trend towards remote and rural GP practices handing their 17J contracts back to the local NHS board for those services to be provided directly by the board.

In light of this evidence, the Committee calls on the Scottish Government to explore the extent to which a revised, more flexible approach to implementation of the 2018 GMS contract, specifically in remote and rural settings, might help to improve the sustainability of remote and rural GP services and the financial viability of remote and rural practices. It should also examine examples where 17J contracts are being directly managed by the local NHS board and any lessons to be learned from that experience for future delivery of GP services in remote and rural areas.

The Committee believes that much greater structural support should be given to remote and rural GPs to enable them to develop their skills and experience by facilitating greater opportunities to work simultaneously in GP practices and clinical settings. It therefore calls on the Scottish Government, NHS Boards and professional bodies to set out what they are doing collectively to promote and facilitate such opportunities to enable remote and rural GPs to work across different settings.

Funding and Investment

In light of evidence during this inquiry that the current NRAC funding formula fails to meet the specific needs of remote and rural areas, the Committee reiterates previous calls it has made for this formula to be reviewed and reformed to take better account of specific challenges and associated higher costs of healthcare delivery facing those areas, including an ageing population, depopulation, and the greater requirement for small scale service delivery.

The Committee calls on the Scottish Government to work with local decision-makers to explore opportunities to develop a revised approach to funding application and allocation processes that will mitigate against the current funding uncertainties faced by many third sector organisations providing healthcare services in remote and rural areas. This should include exploring opportunities to provide longer term funding certainty to those organisations, including through multi-annual funding allocations, and improving application processes through enhanced transparency, reducing unnecessary administrative burdens and better communication.

Access to Services and Service Provision

The Committee has heard evidence of ongoing pressures on the provision of social, palliative and end of life care services in remote and rural areas, and that the location of a number of care homes in older buildings has meant they are unable to comply with modern accommodation standards. The Committee also highlights evidence that, given the tendency towards an ageing population increasingly living in more remote and rural areas of the country, demand for these services is projected to increase significantly in the years ahead.

The Committee equally heard many stories illustrating how a combination of increasing demand and diminishing supply is forcing a growing number of people to have to travel long distances from where they live to be able to access these services.

In this context, the Committee would recommend a comprehensive audit of social, palliative and end of life care services in remote and rural areas to develop a clear picture of service provision, including the availability of care at home services. The Committee takes a view that a clear strategy is needed to develop innovative approaches, including greater provision of care at home and local community services to enable a much greater number of people to receive these services close to, or at, home - within the communities where they live.

The Committee has heard evidence of the particular importance of providing more localised support for people suffering with poor mental health given the high likelihood that having to travel long distances is likely to exacerbate their condition or discourage them from accessing those services at all. The Committee recommends that this issue could be addressed by facilitating opportunities for local treatment from travelling consultants as well as expanding the availability of online appointments.

The Committee equally acknowledges the importance of addressing the mental health needs of healthcare staff working in remote and rural areas, countering the potential negative effects of isolation by ensuring staff are given access to a reliable support network of their peers. The Committee believes this should be a particular area of focus for professional bodies in supporting recently graduated staff undertaking remote and rural placements.

The Committee notes evidence of the particular impact of alcohol use in remote and rural areas and the consequent need for improved provision of drug and alcohol support in those areas. In this context, it wishes to highlight the recommendation from Alcohol Focus Scotland that this should be a specific area of focus for the National Centre for Remote and Rural Health and Care as part of its initial work to address primary and community care provision.

The Committee has received extensive evidence of the often substantial additional travel and accommodation costs people living in remote and rural areas will incur when accessing healthcare services. The Committee further notes significant variations in access to reimbursement for these costs, depending where an individual lives and whether or not they are in receipt of benefits. It therefore calls on the Scottish Government to set out what actions it will take to encourage development of a more consistent and suitably flexible policy for reimbursement of travel and accommodation costs for remote and rural patients accessing healthcare.

Opportunities

The Committee has heard evidence that, properly utilised, technology and digital infrastructure offer the potential to improve the quality and delivery of healthcare services in remote and rural areas. At the same time, it recognises that healthcare needs to be offered to patients according to their own preferences and what is convenient for them - and that many will continue to have a preference for face-to-face appointments.

The Committee has equally heard evidence that digital provision in remote and rural areas is patchy and is often of insufficient quality to be used to its full potential, be that in terms of improved provision of services or improved access to training for staff. The Committee has concluded there is a need for a detailed cost-benefit analysis of increased investment in technology and digital infrastructure to determine where such investments can be targeted to maximise their positive impact on the delivery of healthcare services in remote and rural areas.

Throughout the inquiry, various stakeholders have emphasised the importance of robust data collection and research to measure the impact of specific policy decisions on improving access to and provision of healthcare services in remote areas, and to ensure future policy measures are effectively targeted. In this context, the Committee calls on the Scottish Government to set out the steps it is taking to ensure that improved data collection and research on healthcare provision in remote and rural areas is a key area of focus for the new National Centre on Remote and Rural Health and Care, including -

the facilitation of improved access to, and sharing of, research and data across healthcare teams working in remote and rural communities; and

action to plug any clear gaps in available data needed to improve healthcare delivery in those communities.

Remote and Rural Workforce Recruitment Strategy

The Committee looks forward to the forthcoming publication of the Scottish Government's Remote and Rural Workforce Recruitment Strategy and requests an update on progress, key areas of focus and planned timetable for publication and implementation.

Based on the evidence it has received during this inquiry, the Committee has concluded that it would be beneficial for the scope of the Strategy to include actions to address wider issues affecting retention of staff in remote and rural areas, access to training, improved availability of opportunities for career development and progression. To be truly effective, the Strategy must have a twin focus on highlighting the unique opportunities working in a remote and rural environment can offer as well as addressing the structural challenges around pay and working conditions that make working in healthcare in remote and rural settings comparatively less attractive to potential candidates.

The Committee equally concludes that, in order to be successful, the Strategy needs to adopt a whole system approach by identifying actions to address all potential barriers to recruitment in remote and rural areas, including availability of affordable housing, schooling and childcare, reliable and affordable transport links and digital connectivity that will otherwise act as a disincentive for healthcare professionals to relocate to these areas.

The Committee agrees with many stakeholders engaging with this inquiry that a key focus for the Strategy should be to improve the sustainability of remote and rural healthcare services by building workforce resilience. The Committee therefore calls on the Scottish Government, in responding to this report, to set out how it intends to ensure the Strategy actively contributes to meeting that goal.

The Committee also takes a view that the Strategy must include robust provisions for ongoing monitoring of key challenges and opportunities related to recruitment and retention of the healthcare workforce in remote and rural areas.

The Committee further highlights to the Scottish Government related recommendations contained earlier in this report which relate to the remote and rural workforce recruitment strategy.

National Centre for Remote and Rural Healthcare

The Committee has been concerned by evidence of a general lack of awareness of the purpose and remit of the National Centre. It therefore asks the Scottish Government to set out what it is doing to promote awareness of the National Centre amongst key stakeholders, including remote and rural patient groups and healthcare staff and to engage these stakeholders in its current and future work.

The Committee highlights stakeholder concerns that, too often, a "one size fits all" approach to the development of healthcare policy fails to address the particular needs of remote and rural communities or to reflect the diversity of local issues and circumstances across different remote and rural areas in Scotland. The Committee therefore believes that developing a more tailored approach to healthcare service delivery that is more flexible and responsive to local needs, challenges and circumstances needs to be an overarching priority of the new National Centre. In particular, the Committee would recommend a review of impact assessment processes to ensure their findings are consistently and properly reflective of local situations and can help to inform a more locally tailored approach to delivery of remote and rural healthcare in the future.

The Committee also believes that the National Centre has an important role to play in breaking down the existing siloed approach of many organisations involved in designing and delivering healthcare services in remote and rural areas. In addition, the Committee seeks a specific commitment from the Scottish Government that, as it develops, the National Centre will assume a clearly defined role in acting as an advocate on behalf of remote and rural communities that use those services. In this context, the Committee would request that the Scottish Government keep it regularly updated about the National Centre's future work plan and key areas of focus.

The Committee further highlights to the Scottish Government related recommendations contained earlier in this report which relate to the National Centre for Remote and Rural Health and Care.

Introduction

People living in remote and rural areas face unique challenges when it comes to accessing healthcare and the Scottish Government has made a number of policy commitments aimed at tackling these challenges.

In recognition of this, the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee decided to undertake an inquiry to get a better understanding of these challenges and to scrutinise the policy response of the Scottish Government. A key aim of this inquiry was to hear directly from individuals and stakeholder groups with a view to making targeted recommendations with a view to shaping existing and future healthcare policy in a way that best serves the needs of remote and rural communities.

The Committee first agreed its approach to the inquiry at its meeting on 13 June 2023. In its approach, the Committee examined previous relevant scrutiny undertaken including its inquiries into alternative pathways for primary care, health inequalities and NHS boards scrutiny.

At its meeting on 17 January 2023, the Committee also heard from the Cabinet Secretary for Health and Sport as part of its consideration of the following petitions:

PE1845: Agency to advocate for the healthcare needs of rural Scotland

PE1890: Find solutions to recruitment and training challenges for rural healthcare in Scotland

PE1924: Complete an emergency in-depth review of Women’s Health services in Caithness & Sutherland.

Prior to this session the Committee agreed to write to remote and rural health boards seeking evidence on the issues raised within the petitions.

The following submissions were received:

• NHS Western Isles submission

• NHS Ayrshire and Arran submission

Following this evidence session on 17 January 2023, the Committee agreed to close petitions PE1845 and PE1890 on the basis that the issues raised would be considered as part of a broader inquiry into remote and rural healthcare.

A decision on petition PE1924 was deferred until after the Best Start North Review had concluded. On 30 August 2023, the Committee received correspondence from the Minister for Public Health and Women's Health which stated the Best Start North Review's work had been superseded by the independent Moray Maternity Services Review.

These petitions and the evidence received helped form the basis of the Committee's inquiry into remote and rural healthcare.

The Committee agreed to begin the inquiry by issuing a key issues consultation using the Your Priorities platform. This ran from 16 June 2023 until 11 August 2023. The Committee was keen to hear directly from stakeholders and members of the public about the key issues and challenges they face when accessing healthcare in remote and rural areas. The responses received were intended to help the Committee determine key areas of focus for the inquiry. The consultation received a total of 179 ideas, with 221 comments, reaching 218 users comprising a range of individuals and stakeholder organisations from across Scotland.

Following the conclusion of the key issues consultation, the Committee agreed that the focus of the inquiry should be to consider the views of remote, rural and island communities, and the workforce, with a view to informing future Scottish Government policy in this area, including in particular:

The Scottish Government's Remote and Rural Workforce Recruitment Strategy; and

the development of the National Centre for Remote and Rural Health and Care.

On 14 September 2023, the Committee launched a more detailed Call for Views . Based on responses from the key issues consultation and in the specific context of the anticipated Scottish Government policies outlined above, respondents were asked five questions:

Are there any immediate issues unique to remote and rural communities which the National Centre for Remote and Rural Health and Care will need to focus on to improve primary and community care in these areas?

Are there any issues which the National Centre will be unable to address, which may require further policy action from the Government?

What would you like to see included in the Scottish Government’s forthcoming Remote and Rural Workforce Recruitment Strategy?

What specific workforce related issues should the strategy look to resolve? •

Are there any workforce-related issues which the creation of a Remote and Rural Workforce Strategy alone will not address. If so, what are these issues and what additional action may be required to address them?

The call for views ran from 14 September until 20 October 2023 and received 70 responses. Following its closure, research colleagues produced a summary of responses.

The data gathered from the call for views was not intended to reflect a representative sample of the population, but rather to offer a snapshot of the experiences, opinions, and concerns expressed by those who responded, and to support the selection of appropriate witnesses to give oral evidence. The call for views was structured in a largely qualitative manner, with open text boxes to enable respondents to express their views in their own words. The responses were analysed using thematic analysis.

As part of the inquiry, Members of the Committee also participated in a programme of informal online engagement on 30 January and 6 February 2024. During these sessions, the Committee heard from participants representing local patient campaign groups as well as rural GPs and multi-disciplinary teams (MDTs).

Members of the Committee also carried out an external visit to the Isle of Skye on Monday 13 May 2024. Members met with staff at the Broadford Medical Centre to hear first hand of their experience dealing with primary care in the area, as well as the unique challenges associated with serving patients in remote, rural and island areas. They also met with staff from Broadford Hospital, where they received a tour of the newly built facility as well as holding discussions with available staff at the hospital. Members then spent the evening meeting with various patient groups, individuals, and stakeholders at Skye and Lochalsh Mental Health Association to learn more about its work and the specific challenges faced by the organisation and its users.

.png)

The Committee also held six formal evidence sessions, taking evidence from a broad range of relevant stakeholders, as detailed below:

Meeting date Witnesses and themes 21 November 2023 Representatives from NHS Education for Scotland (NES) and Scottish Government officials on the National Centre for Remote and Rural Health and Care and the Remote and Rural Workforce Recruitment Strategy 28 November 2023 Academics (focusing on rural health and wellbeing) 5 December 2023 Stakeholders (representing various health professions) 12 December 2023 Stakeholders (representing the healthcare workforce) 19 December 2023 Stakeholders (representatives from healthcare professional associations) 21 May 2024 Cabinet Secretary for Health and Social Care and supporting officials.

It should be noted that, during the course of taking oral evidence, the Committee was required to pause its work on the inquiry to allow it to deal with other time-sensitive priorities as part of its work programme, hence the significant gap between the fifth and sixth oral evidence sessions.

Background

As background context for this inquiry, it is important to recognise that there are many differing views and approaches with respect to addressing the specific challenges facing provision of, and access to, healthcare in remote and rural areas in Scotland. Be it directly or indirectly, many different policy initiatives and decisions have influenced the current healthcare landscape in Scotland, including in more remote and rural areas.

However, one of the key issues which has emerged as a constant throughout this inquiry is the extent to which national policy outcomes are properly reflected in the experience of patients, workers, and stakeholders in remote and rural areas - particularly when compared to more accessible and well populated areas of Scotland.

Sir Lewis Ritchie Report

On 30 November 2015, the Main Report of the National Review of Primary Care Out of Hours Services was published. Better known as The Sir Lewis Ritchie Report, named after the Chairman of the Independent Review, it made a number of recommendations for the future of Primary Care services in Scotland, many of which are still in the process of being implemented in remote and rural areas.

The 2015 report had a national focus for redesigning primary care services in Scotland. It suggested various guiding principles in Health and Care Design and Delivery which would underpin service delivery in the future, namely that services should be:

Person-centred

Intelligence-led

Asset-optimised

Outcomes-focused

As well as this, it stated such services should be:

Desirable

Sustainable

Equitable

Affordable

The report concluded that, for this new approach to urgent care to be successful, multi-disciplinary teams (MDTs) must be effectively trained and supported, with the right conditions created in workspaces for people to be valued, to facilitate effective communication and to encourage continuous professional development. The report also states that, in order for these conditions to be met, there would be a need for technologically enabled and innovative working environments which are fit for purpose for both service delivery and training.

The themes outlined above were also echoed in evidence submitted to the Committee throughout this inquiry.

Crucially, the Review also recommended that a national implementation plan, supported by local implementation guidance, be developed. It was argued that this recommendation would play a key role in transforming services in remote and rural communities, where needs often differ to those in other areas of Scotland.

As a specific example of such local guidance, the Sir Lewis Ritchie Review made further recommendations in 2018 with a particular focus on addressing urgent care provision in North Skye. The implementation of these recommendations continues to be a key focus for the Health Board and the Scottish Government, with regular updates on progress with implementation available on the NHS Highland website.

Demographics

As a helpful illustration of the complexity involved in delivering healthcare services in remote and rural areas, the Committee notes the work done by the Rural Scotland Data Dashboard to present data on a range of issues impacting rural Scotland. In 2023, the Scottish Government published the Rural Scotland Data Dashboard: Overview, which is intended to accompany the dashboard and provides a synthesis of the data collected by the Dashboard to give a broad outline of successes, challenges, and trends in rural Scotland across a range of policy areas, including health and social care.

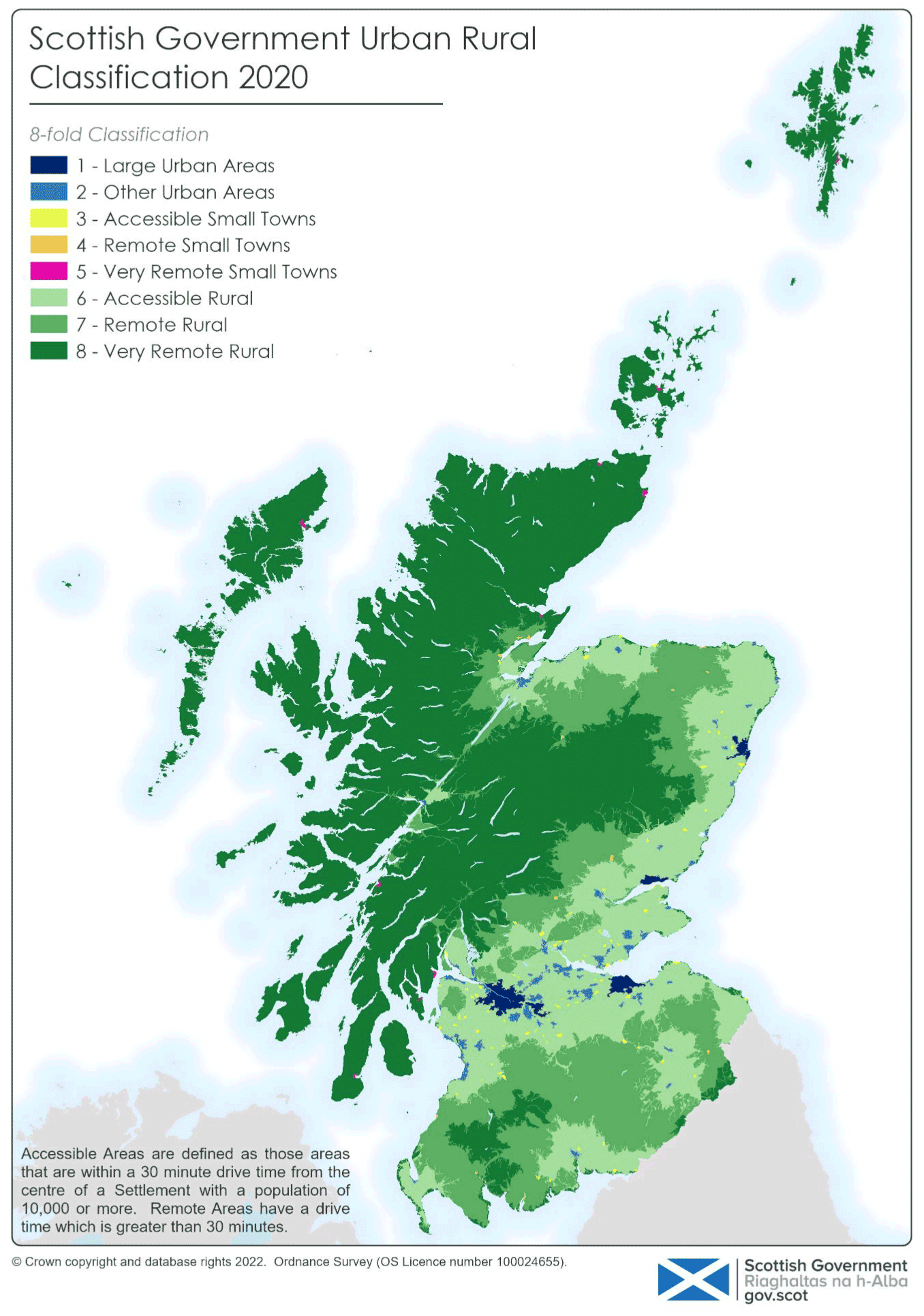

The Dashboard and subsequent overview uses the Scottish Government Urban Rural Classification 2020, which the Committee also referred to in determining its approach to this inquiry.

The way of defining urban and rural areas across Scotland is based on two main criteria:

Population - as defined by the National Records of Scotland

Accessibility - based on drive time to a Settlement with a population of 10,000 or more.

The Scottish Government's core definition of rurality classifies areas with a population of fewer than 3,000 people to be rural. These classifications are then collapsed to this core definition, creating an 8-fold classification:

Large Urban Areas: Settlements of 125,000 people and over.

Other Urban Areas: Settlements of 10,000 to 124,999 people.

Accessible Small Towns: Settlements of 3,000 to 9,999 people, and within a 30 minute drive time of a Settlement of 10,000 or more.

Remote Small Towns: Settlements of 3,000 to 9,999 people, and with a drive time of over 30 minutes but less than or equal to 60 minutes to a Settlement of 10,000 or more.

Very Remote Small Towns: Settlements of 3,000 to 9,999 people, and with a drive time of over 60 minutes to a Settlement of 10,000 or more.

Accessible Rural Areas: Areas with a population of less than 3,000 people, and within a drive time of 30 minutes to a Settlement of 10,000 or more.

Remote Rural Areas: Areas with a population of less than 3,000 people, and with a drive time of over 30 minutes but less than or equal to 60 minutes to a Settlement of 10,000 or more.

Very Remote Rural Areas: Areas with a population of less than 3,000 people, and with a drive time of over 60 minutes to a Settlement of 10,000 or more.

For the purpose of this inquiry, the Committee agreed to define remote and rural healthcare areas as those areas marked 4, 5, 7 and 8 on the Scottish Government Rural Urban Classification map. This was to ensure the Committee could effectively scrutinise the key issues identified without being unnecessarily restrictive.

Data from the National Records of Scotland indicate that most people in Scotland live in large urban areas and accessible small towns. By comparison, as at mid-2021, data showed that:

12% of the population (660,901 people) lived in accessible rural areas, and

1.6% of the population (299,115 people) lived in remote and rural areas.

The Scottish Government's report "A Scotland for the future: opportunities and challenges of Scotland's changing population" sets out some of the key issues facing the health and social care system as a result of changing demographics and concludes:

An ageing population, with an increasing number of our 'oldest old' citizens, has the potential to transform our population's health and care needs. In order to address these, careful long-term systems planning is needed. While many older people will enjoy better health than their predecessors did at an equivalent age, they will still have significant health needs living with potentially multiple conditions, and the overall impact will be a steadily increasing demand for health and social care.

The Committee has heard evidence that there are significant pressures facing the health and social care system across Scotland as a consequence of increased demand resulting from changing demographics as well as a rising number of people with increasingly complex needs. However, it also heard that these pressures are often exacerbated in remote and rural areas.

Education and Training

A common theme arising throughout the inquiry was the need for improved access to education, training and professional development opportunities for rural healthcare staff.

Many respondents to the Committee's call for views highlighted the importance of better education and training. For example, NHS Education for Scotland argued in their submission that there is a need to:

Develop and deliver unique training, education and leadership development programmes that equip remote and rural healthcare staff to innovate and lead service improvements aligned to the changing needs of their remote and rural communities.

In their submissions, the Royal College of Nursing (RCN) and other individual respondents recognised the unique challenges facing the remote and rural workforce and highlighted the need for "locally accessible" education access routes, in particular for midwives. One respondent suggested this could be delivered in conjuction with universities in remote and rural areas with the aim of growing the remote and rural workforce.

This need for locally accessible education access routes was echoed by Professor Annetta Smith, Professor Emerita at University of the Highlands and Islands, in oral evidence to the Committee on 28 November 2023:

Locally accessible training is vital.... If we ensure that students who are in training have access to remote and rural placements so that they get a taste of what remote and rural healthcare is like, and if we make those placements as good as they can be and they are supported, it might increase the likelihood of attracting some of those professionals back to those areas...

A healthcare professional may, after having that experience, come and work in a remote and rural area for two or three years rather than stay there forever. We have to look, therefore, at how we maximise the opportunities through education, training and placements. If we make those the best that they can be, we can encourage people to work in remote and rural areas, rather than having them feel as though they are going to work in a backwater and that their professional career is going to stagnate. It needs to be the opposite: it has to be seen to be exciting professionally, with opportunity, education and training built in.

Witnesses were asked whether better use could be made of existing initiatives to support local skills development and training such as the Clinical Skills Managed Education Network (CSMEN) mobile skills unit. Laura Wilson, from the Royal Pharmaceutical Society, responded:

Yes. We would support any training that can be done more locally, that does not take pharmacists away from their practice for longer than is necessary and that allows them to build up skills.

Also, the pool of senior pharmacists who can provide peer review and support is far more diluted in remote and rural areas. It would be more than welcome if attempts were made to encourage them to take part in those things and to provide them with support and training to do so.

During oral evidence, Dr Iain Kennedy of the British Medical Association, reflected positive experience of the Scottish Graduate Entry Medicine (or ScotGEM) programme in providing opportunities for students to undertake training in remote and rural areas. At the same time, he suggested that additional focus was still needed on encouraging more of those same students to continue working in remote and rural areas once they had completed their studies. He stated:

The BMA in Scotland, and colleagues more widely, have a very positive perception of ScotGEM. I highlight another conflict of interests: my practice trained the first batch of ScotGEM students in Inverness. I can remember groups of six students coming in. We had one of our GPs freed up for a full two days every week purely to train ScotGEM students. The students are highly motivated, mature and brilliant.

One concern is whether the students come back to work in rural areas. However, ScotGEM is regarded as a success. I think that we should try to emulate the bursary that those students get for undergraduate medical students at our universities, so that they can be funded to go to rural areas, which obviously attracts much greater costs.

The Committee heard evidence that much work has been done over the years to tailor education, training and workforce support to the specific needs of staff working in remote and rural areas. Dr Pam Nicol, Associate Director of Medicine and the National Centre of Remote and Rural Health and Care Lead, NHS Education for Scotland, told the Committee:

In 2008, the Scottish Government supported the establishment of the first permanent team—the NES remote and rural health care education alliance—and for the past 16 years we have been delivering education, training and workforce support. However, we are very keen to also be able to leverage the expertise of partners across Scotland who have expertise in remote and rural research and evaluation, in the development of leadership skills and good practice and also in recruitment and retention.

During an informal engagement session with Rural GPs and MDTs on 6 February, Members asked participants how easy they found it to access suitable training. In response, participants highlighted difficulties with supporting learning given the level of understaffing in remote and rural communities. They suggested that, because of the difficulties faced with releasing remote and rural staff to undertake additional training to support career development, many are deterred from taking up positions in remote and rural areas, viewing it as an unwise career move.

Participants also noted that MDTs in remote and rural areas often include many part-time staff, making it particularly difficult to arrange training sessions at suitable times and locations to accommodate all those looking for development opportunities.

A lack of development posts (i.e posts whereby the successful candidate would complete a programme of learning and development) was highlighted as a further challenge in rural areas. As an example, it was pointed out that, at the time of discussion, there was only one specialist midwife position available in the whole of NHS Highland.

During the same informal session, some Rural GP participants also highlighted particular difficulties with providing suitable staff training within remote and rural practices, given that Rural GPs are often required to operate as "jacks of all trades."

For allied health professionals, the Committee heard evidence of similar issues related to training and further development of remote and rural staff. In evidence on 5 December 2023, Derek Laider of the Chartered Society of Physiotherapy told the Committee:

...one solution that we really need to push forward is training people who already live and are embedded in a locality and who are not going to go elsewhere. We need to utilise opportunities such as earn as you learn and apprenticeships to try to solve recruitment and retention issues.

The Committee wishes to highlight the extensive evidence it has received of the critical importance of local availability of suitable training and development opportunities to support recruitment and retention of the healthcare workforce in remote and rural areas. The Committee calls on the Scottish Government and NES, in responding to this report, to set out they are doing to improve the availability, suitability and flexibility of local training and development opportunities in remote and rural areas as a key component of their overall strategy for nurturing Scotland's remote and rural healthcare workforce.

The Committee notes evidence from multiple stakeholders that the development of "Earn as you learn" programmes in remote and rural areas could play an important role in increasing the prospective workforce in these areas and making those areas more attractive destinations for student placements. The Committee therefore calls on the Scottish Government to ensure that the development of such programmes and increased availability of such opportunities form an integral part of its forthcoming Remote and Rural Workforce Recruitment Strategy.

The Committee calls on the Scottish Government to address the concerns it has heard raised that training arrangements for staff seeking to work in remote and rural areas, particularly AHPs, lack flexibility to enable them to complete their training locally. In particular, the Scottish Government should work with professional bodies, training providers and NHS Boards to explore opportunities to condense training into a shorter time period and to provide training online so workers are not obliged to relocate to the central belt to complete their training, incurring additional time and cost commitments as a consequence.

More broadly, the Committee calls on the Scottish Government, Scottish universities and colleges, professional bodies, and NHS Boards to explore ways of offering more local training and development opportunities in remote and rural areas.

Issues around Recruitment and Retention

The Committee heard evidence throughout the inquiry that one of the main challenges faced by remote and rural healthcare relates to recruitment and, crucially, retention of suitably skilled and qualified staff.

Pay and working conditions

Throughout this inquiry, the Committee heard extensive evidence that the retention of healthcare staff in remote and rural areas has been a key challenge to the effective delivery of services. Although the Committee heard evidence of a wide variety of factors affecting retention, one factor that was particularly often mentioned was staff pay and working conditions.

The need for improved pay and conditions for staff was consistently raised by respondents to the Committee's call for views and also in oral evidence. Given current challenges with the cost of living, compounded by the additional costs associated with living remotely, there was a consensus that current pay rates and working conditions offer insufficient incentive for staff to remain in remote and rural areas.

Travel expenses was a commonly raised issue during the inquiry with many highlighting that remote and rural staff are often expected to use their own vehicle to deliver services. One individual response to the call for views highlighted:

[Nursing staff] are required to use their own vehicles to travel down very rough dirt roads and if any damage occurs to their own cars they have to pay for it themselves.

Meanwhile, in common with a number of individual submissions, Waverley Care highlighted the need to address payment of travel time and petrol expenses to carers and care at home staff. One individual told the Committee: “staff simply can not afford not to be paid as distance between clients can be considerable”, adding that, in their view, the lack of pay for travel time and expenses made the care at home service “undeliverable” in many remote and rural areas.

During an informal engagement session on 6 February 2024, Members also heard evidence that the impact of tourism in driving up the cost of living in certain remote and rural areas (for example, Aviemore) made recruitment and retention even more challenging, with wages being insufficiently competitive to attract healthcare staff to live and work in those areas.

Specific issues were raised with regards to midwifery - with one participant pointing out that specialist midwifery posts are currently offered at the same pay band as other midwifery posts. It was also suggested that community midwifery positions typically available in more remote and rural areas were less attractive than hospital midwifery positions typically found in the central belt, which would tend to offer a better work-life balance and greater flexibility with shift patterns, making them a more attractive option for many prospective staff or trainees.

Organisations, including Age Scotland and The Royal College of Nursing (RCN) Scotland, also highlighted the need for improved pay and conditions to make working in remote and rural areas more attractive.

Specifically, in response to the question in the call for views as to what the Remote and Rural Workforce Recruitment Strategy should look to resolve, The Royal College of Anaesthetists (RCoA) highlighted the need to:

Make R&R working attractive through enhanced remuneration […] and provision for flexible working.

Another individual argued that staff should be paid “from beginning to end of shift, not just the time spend in an individuals home", pointing out that "remote and rural [staff] may spend more time travelling than providing care”.

During an informal engagement session, rural GPs also spoke about their experiences of a high turnover of staff in smaller (one or two) practitioner practices. They suggested a key reason for high staff turnover in these smaller remote and rural practices was a general feeling of being "not treated well" and of being devalued.

Participants also noted that smaller practices suffer from limited succession planning with the result that there is no natural route for younger GPs to progress in more remote and rural areas. At the same time, one participant noted a positive recent trend towards increased rural placement of students.

Challenges finding suitable candidates

Throughout the inquiry, the Committee heard evidence that recruitment in remote and rural areas is challenged by a lack of recognition within salary structures for the specific levels of skill and experience required to deliver services in a remote and rural context.

In evidence on 12 December 2023, Nicola Gordon representing the Royal College of Nursing, told the Committee:

We are hearing from members that pay structures do not always recognise the additional responsibility in remote and rural roles. In the NHS, a band 5 nurse can sometimes be the only registered nurse who is on shift. At band 5 pay level, she will be taking on the responsibilities that would normally be for more senior nurses—she might be covering the role of a senior charge nurse or a band 7 nurse. The pay structure does not reward that, which can be a disincentive.

During an informal engagement session, MDTs explained that they have seen a particular shift in recruitment for positions in remote and rural areas over the last 3 years, with posts now needing to be advertised multiple times a year to find suitable candidates.

Participants went on to explain that many foreign applicants applying for posts are not properly trained or qualified for the roles advertised and that many of these posts require experience or prior training in multiple disciplines to be able to deliver services specifically in a remote and rural context.

During informal engagement, one Rural GP participant told Members that their practice hasn't experienced many issues with recruitment, but added that this was mainly due to being able to recruit former trainees living locally who have subsequently qualified as GPs. At the same time, this participant acknowledged that many other practices in remote and rural areas would not be in such a fortunate position - for example, while practices in and around Inverness may face limited difficulties, this may not be the case for practices in more remote areas such as Caithness and Sutherland.

Allied Health Professions

Throughout the inquiry, the Committee heard evidence from across the wider healthcare workforce, beyond rural GPs and MDTs. This evidence highlighted a number of acute challenges associated with the delivery of wider healthcare services by the allied health professions.

In evidence to the Committee on 5 December 2023, Sharon Wiener-Ogilvie of the Allied Health Professions Federation, which includes 14 professional bodies and around 14,000 staff across Scotland, pointed to significant recruitment challenges in remote and rural areas. She told the Committee that, in some areas, 35 per cent of staff were due to retire in the next five to seven years and up to 20 per cent of posts are currently vacant. She went on to say:

What concerns us particularly is that, even when new graduates apply for posts, they stay for a very short duration and tend to leave after two years. They use the post as a stepping stone to get some experience, then go and work elsewhere. That happens for two reasons. First, practitioners require more generalist skills to work in rural areas, which sometimes seems less attractive to staff. Secondly, there is less career progression in remote and rural areas. There is no way for remote and rural areas to incentivise people to come and work in those areas and then to stay there. People need to travel to different locations to deliver care. That is very expensive for staff.

Ms Wiener-Ogilvie also highlighted challenges associated with the reduced numbers of AHPs coming out of universities and suggested that fewer graduates are applying for posts. She continued:

We feel that there are solutions, including grow-your-own-workforce initiatives such as earn and learn. However, to do that, we need the universities to deliver training to allied health professionals in a flexible way. Online training needs to be delivered remotely and the academic curriculum needs to be condensed so that it is delivered, for example, over three days, not five, with the AHP undertaking two days’ practical work in their host health board. That way, we can recruit people from remote and rural areas who very much want and need jobs in those areas, and they will not have to relocate to the central belt to do their training, which is very costly. I think that there is appetite from boards to deliver such solutions but, at the moment, the universities do not provide the hybrid learning that would allow us to provide those opportunities.

Wider rural issues

The Committee also heard extensive evidence of the impact wider issues associated with living in a remote and rural are having on access to healthcare as well as recruitment and retention of remote and rural healthcare staff.

Housing

Challenges around availability and affordability of housing for staff came up extensively throughout the inquiry.

Many respondents to the Committee's call for views highlighted the impact a lack of affordable accommodation for permanent, temporary and student staff is having on recruitment and retention. In its written submission, the Scottish Women’s Convention (SWC) stated:

[There] isn’t enough staffing because we sometimes get supply nurses down, and some of them would like to stay on, and they might like to bring their families, but there’s no housing for them.”

Another individual submitted:

Airbnb and holiday homes have reduced already scant availability and health boards have sold of much of the traditional 'nurses' homes. There is no priority housing for essential workers.

Challenges associated with a lack of affordable housing were echoed by Neil Carnegie, Community OT Team Manager (Kirkcaldy & Postural Management), Fife HSCP and representing the Royal College of Occupational therapists, to the Committee on 5 December 2023:

The cost of housing can make it difficult to attract and retain staff, because they just cannot afford to live in those areas. That is mainly because prices have been pushed up by tourists and because a lot of people own second homes.

In evidence on 12 December 2023, Dawn MacDonald, representing the Highland healthcare branch at Unison, told the Committee that Unison's members have similarly reported housing pressures in remote and rural areas - with nurses forced to turn down remote and rural placements because they are unable to find affordable accommodation in the local area.

She went on to tell the Committee that, from those students fortunate enough to be able to find temporary accommodation during their placement, feedback is for the most part extremely positive because those students will typically find that they gain a rich knowledge and experience from their placement which they would not necessarily have found on placement in the central belt.

When asked for examples of good practice in attracting students to take up placements in remote and rural areas, Dawn MacDonald elaborated:

One example is from what we did in Bute to keep student nurses coming there. We are a small island with a population of 7,000, and we wanted to keep the students coming. We spoke with some hoteliers and, because their properties are quiet in the winter, we did a deal with them to bring in students at a reasonable price. I cannot say that the accommodation was always fantastic, but I reiterate that, when placements happened, the students said their experience was invaluable.

Representing the Royal College of Midwives during the same evidence session, Jaki Lambert outlined certain pockets of good practice but noted discrepancies in the relative availability of accommodation for nursing and midwifery compared to other categories of medical staff:

In areas that still have protected accommodation, such as nurses residences, keeping a space that is always available for students has worked....

Part of the challenge is getting arrangements in place with local bed and breakfasts. That trade is seasonal, which can often be a challenge. Some hospitals put up adverts to see whether folk can make rooms available.

There has been some innovation, because people want students—they want folk to come and work in the area. The approach often involves having local arrangements in place or protecting space. The challenge is that space has often been protected for medical staff but not for nursing and midwifery, and we have to fight the corner for nursing and midwifery.

At its meeting of 21 November 2023, Stephen Lea-Ross, deputy director of health, workforce planning and development at the Scottish Government, informed the Committee that, in addition to an annual bursary for student nurses across all programmes of £10,000, the Scottish Government also provides out-of-pocket expenditure for placement activity across the country. He concluded:

That combined package of financial support is the most advantageous that is offered anywhere in the United Kingdom, but it is being reviewed in line with the evidence that we are taking as part of the nursing and midwifery task force, which was commissioned on the back of the 2023-24 agenda for change pay offer. That task force is looking expressly at attraction, selection and the package and offer of support that is available to nurses in training as well as to attract graduates to posts across the country; in particular, it is looking at the rural and island infrastructure component that poses an additional burden.

When asked what actions the Scottish Government is currently taking to improve availability of affordable housing for healthcare staff in remote and rural areas, Mr Lea Ross responded:

In our engagement with colleagues across Government who are leading on the rural development plan, we have picked up the question of key worker housing. By that, I mean not just providing housing for placement and peripatetic staff, but increasing housing availability more generally as part of the effort to attract staff to live and work in the communities that they serve, which includes both local or domestic and international recruitment efforts. Off the top of my head—I would have to double-check the figure—I think that the commitment is around £30 million worth of investment, as part of the Scottish Government’s broader housing strategy commitment to invest in new housing to support key workers across the country.

Other public services including childcare and transport

Evidence submitted to the Committee throughout the inquiry emphasises the significant impact challenges associated with delivery of other public services, notably childcare and public transport, can have on provision of, and access to, healthcare in remote and rural areas.

There was a broad consensus among respondents to the Committee's call for views that poor or inadequate availability of childcare creates an additional barrier to working in healthcare in remote and rural areas. In its written submission, the British Medical Association (BMA) Scotland stated:

Childcare facilities, especially in more isolated regions, are scarce. Unlike their urban counterparts, hospitals in these areas often lack childcare services for staff. Additionally, community childcare options, such as childminders, are nearly non-existent in some areas.

Many respondents to the call for views argued that improving childcare services would facilitate an improvement in recruitment and retention of remote and rural healthcare staff as it would make it easier and more attractive for working parents to live in, or relocate to, remote and rural areas. The SWC called for a specific focus in the Scottish Government's Remote and Rural Workforce Recruitment Strategy on tackling obstacles to recruitment for working parents:

The creation of a ‘Remote and Rural Workforce Strategy’ should include clear policy surrounding flexible work options, as well as improved childcare.

Inadequate public transport services were also cited by both Bòrd na Gàidhlig and RCN as a significant obstacle to recruitment and retention in remote and rural areas. Community Pharmacy Scotland (CPS) highlighted the importance of having in place a “reliable, affordable public transport service” for the remote and rural healthcare workforce and that this should include air and ferry services to island communities, as well as reliable and affordable bus and railway links.

Infrastructure including broadband

In addition, there was equally a general consensus throughout the inquiry that the availability and reliability of communications infrastructure, including broadband and mobile network coverage, is a further significant barrier for those providing and accessing healthcare services in remote and rural areas.

Responding to the call for views, the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy argued that, in their experience, poor digital infrastructure in rural areas is a significant barrier to healthcare service provision and access to training opportunities for the healthcare workforce:

Poor-quality broadband and mobile network coverage hinders access to online referral services and limits opportunities to promote health initiatives to individuals and communities. Poor digital infrastructure also presents challenges for the existing healthcare workforce, preventing access to essential training and professional development.

At the Committee's evidence session on 28 November 2023, Dr Stephen Makin, senior clinical lecturer at the University of Aberdeen and honorary consultant geriatrician at NHS Highland, argued that broadband issues can hinder digital innovation intended to enhance and streamline service delivery:

NHS Near Me is a great service for video consultations, but someone in a rural area needs to have expensive broadband to be able to access it at home. They need to have fibre optic broadband. I am talking to you from a house that does not have fibre optic broadband; I pay £50 a month to get mobile broadband. When I try to do a video clinic, the broadband that most of my patients have is not good enough for a video call, so we just end up talking on the phone, which negates the whole point of the service—it is not the same.

Poor availability of broadband and mobile coverage was also raised in the Committee's informal evidence session with remote and rural GPs and MDTs on 6 February 2024, with some participants highlighting that poor or non-existent home WiFi or mobile broadband prevents them from updating records or managing systems requiring an internet connection during patient visits, thereby hampering the quality of service they are able to provide.

The Committee highlights the significant extent to which a lack of available affordable housing is acting as an indirect barrier to healthcare provision in remote and rural areas of Scotland by dissuading or making it practically impossible for healthcare workers to locate themselves within the remote and rural communities they would otherwise wish to serve. The Committee believes this is an issue that needs to be urgently discussed and addressed within relevant fora involving NHS Boards, local authorities, professional bodies, trade unions and other key stakeholders. There is an opportunity to learn from, and to disseminate more widely, local examples of good practice and innovative approaches to resolving this important issue, including:

Repurposing vacant local authority and NHS property to provide accommodation for healthcare workers;

Ensuring healthcare workers are appropriately prioritised within any wider plans to provide additional affordable housing for key workers;

Exploring options for generating additional revenue to be channelled towards provision of more affordable homes for key workers, including those working in healthcare;

Providing incentives for local residents, property owners and tourist accommodation providers to offer temporary accommodation to healthcare workers on placement, for instance through council tax rebates.

From the evidence it has heard during this inquiry, the Committee has also concluded that digital infrastructure has a crucial role to play in significantly improving the availability of appropriate training opportunities for the remote and rural healthcare workforce, for improving their quality of life and thereby making remote and rural areas a more attractive location in which to work, while also improving the quality and convenience of services provided to patients. The Committee therefore calls on the Scottish Government and the UK Government, in responding to this report, to set out the specific actions ithey are respectively taking to improve digital connectivity in remote and rural areas, how these actions will contribute to improving access to and availability of healthcare services and the anticipated timetable for implementation of any relevant plans and strategies.

Service Design and Delivery

Sustainable services

The Committee heard evidence that maintaining sustainable services is particularly difficult in remote and rural areas.

One key factor contributing to poor sustainability of healthcare services in remote and rural areas was deemed by many contributors to the inquiry to be a lack of resilience due to understaffing. In practice, this could mean that, if one staff member is off sick or unable to attend work for some other reason, then services may simply be unavailable for the duration of their absence.

On 5 December 2023, Derek Laider told the Committee:

If you have one practitioner who is providing those services, and that one practitioner is off, there is no service. In central belt areas or other more densely populated areas, that might put pressure on the rest of the team, but there will be some ongoing service. We have to be aware of that aspect for remote and rural areas.

Derek Laider went on to point out that, in the case of allied health professions, the level of resilience is less than for nursing and this exacerbates the issue of poor sustainability in remote and rural areas still further:

We also need to bear in mind that the vacancy factor that is built into nursing budgets is not built into AHP budgets—there is no AHP factor. Therefore, if you hire one physiotherapist, they are there for 42 weeks a year, and you already have a number of weeks when there is no service. If we want a sustainable service for 52 weeks, which does not disappear when one person is off sick, we need to find a way to factor that in.

Speaking to the Committee on 12 December 2023, Michael Dickson of the Scottish Ambulance Service acknowledged challenges around resilience and sustainability of services in remote and rural areas which could be attributed to having smaller teams in those areas. However, he went on to argue that more should be done to promote the unique development opportunities associated with working in smaller teams in remote and rural communities as a means of attracting staff:

It is really easy to focus on the number of staff that we need, but actually, in the small teams that we find in rural locations, a difference of one or two people can be vast for sustainable services. If we lose a couple of people, it can destabilise the whole team. More people are likely to say, “Actually, this isn’t right for me”.

For me, the focus has to be making “remote and rural” a badge of honour and putting it front and centre of what the work of health and social care looks like moving forward. It is a huge privilege to work in these communities. It is a massive opportunity for people to see a breadth of activity that they simply will not get to see if they work in a city centre location or in the central belt, and we need to harness that.

At its meeting on 21 May 2024, the Cabinet Secretary and supporting officials informed the Committee that one of the key focuses of the remote and rural workforce recruitment strategy would be to improve workforce sustainability in rural and island communities. During that same evidence session, Paula Speirs acknowledged that sustainability is an issue which is not necessarily confined to remote and rural areas and therefore requires to be addressed more broadly:

In considering the recruitment and staffing models, we are looking at a slightly wider element—the issue of what is a sustainable model of health and care in our remote, rural and island areas. We must not look at those things separately. That piece of work involves looking not just at our staffing model, but at what a sustainable model of care is, given that our services are particularly fragile. That is not the case only in remote and rural areas. We are making some immediate reforms in a number of areas. The cabinet secretary referred to the need for longer-term reform, but we need to do the planning for that, because if we do not plan, services could become even more fragile.

In his evidence to the Committee, the Cabinet Secretary argued that one of the main pressures on achieving and maintaining sustainable delivery of services is the lack of available hospital beds and informed the Committee that this is an area of focus for NHS Scotland's recently established National Centre for Sustainable Delivery:

We are using the centre for sustainable delivery to identify patients who can be discharged and get them discharged as quickly as possible, and thereby bring down the average hospital occupancy time. We are also working on that with our local government partners.

Whole System approach

One of the key themes arising throughout the inquiry was the need for a more joined up or "whole-system" approach to Government policy action.

One individual noted the need for “joined up thinking”, involving education, health, third sector and others, to enable a holistic approach and prevent “silo-working”. This idea of "silo-working" was also a topic of discussion during informal engagement with patient campaign groups - with some participants suggesting that health boards, the Scottish Government, and many other decision-making bodies appear to operate in silos without clear lines of communication or accountability.

The Committee heard frequent complaints from patient groups that NHS Boards fail to listen and that there is a lack of accountability of executive and non-executive directors who sit on NHS Boards. It was also suggested that many local councillors feel disempowered to be able to change centralised pathways or to provide more localised access to healthcare services.

Many participants during this session expressed a view that there needed to be an independent point of contact who could counteract the perceived siloed approach of many healthcare organisations with "common sense, compassion and caring". In this context, "independent" was understood to mean an advocate for remote and rural areas who does not fall under the remit of local or national Government or healthcare organisations. This reflected the views expressed by supporters of Petition 1845.

During the Committee's informal engagement session on 30 January 2024, the Committee heard from patient advocates from Dumfries and Galloway, specifically Wigtownshire, about the challenges faced by people in their locality with accessing cancer pathways and maternity services. In particular, the Committee heard how many people across Stranraer and Wigtownshire are required to travel to Edinburgh for cancer treatment due to the fact that NHS Dumfries and Galloway is included within the South East Scotland Cancer Network. The Committee additionally heard evidence that many expectant mothers from Stranraer are forced to travel, on average, 75 miles or more from Stranraer and Wigtownshire to hospital in Dumfries for their babies to be delivered.

In its response to the call for views, NHS Education for Scotland argued:

There is a need to also invest in remote and rural social care as part of a whole system approach to fully address the identified inequities in health, wellbeing and care experienced by people living in many of our remote, rural and island communities.

This view was echoed by Professor Annetta Smith, Professor Emerita at University of Highlands and Islands, at the Committee's evidence session on 28 November 2023. Professor Smith argued that access to healthcare services in remote and rural areas is hampered not only by a lack of availability of healthcare professionals but by a range of barriers related to the infrastructure that supports people to live in remote and rural communities, including schooling, childcare, transport, and digital connectivity:

In relation to the recruitment of health and social care staff, the issue relates not just to the availability of staff but to how they live, work and thrive in the Western Isles and to whether the structures to support that are there. If they are not, people simply will not come, because they can choose to go where they will have readier access to services. We can try as hard as possible to recruit staff, but, if the social structures are not there to support people to live and work on the islands, staff will not come. That is one example of the need for a whole-system approach. Things cannot be addressed in isolation; the whole context has to be considered

These points were echoed in the same evidence session by Dr Rebecah MacGilleEathain, research fellow in the division of rural health and wellbeing at the University of Highlands and Islands, who said:

I agree with what Professor Smith has said about the whole-system approach. Instead of having little models for what is going well, important as they are, we need a whole-system approach to infrastructure in order to deliver good health and social care in those communities.

Tailored approach

Many respondents and witnesses also argued the case for a more tailored approach to the delivery of healthcare services in remote and rural areas - one that is more responsive to local circumstances.

In response to the call for views, individuals and organisations, such as RCN Scotland and BMA Scotland, suggested that a “one size fits all” approach to policy is inefficient as it does not consider the unique needs of rural areas.

BMA Scotland equally noted the need for a tailored approach that takes account of the comparative differences of local circumstance between different remote and rural areas across Scotland:

a one size fits all approach across Scotland can disadvantage remote and rural areas, treating all non-urban settings as the same will not work. There needs to be an acknowledgement of the complexity of the problem and the diversity of rural and remote areas to ensure adaptable, flexible approaches are taken.

Waverley Care called for a wide-reaching remote and rural workforce strategy that is “attentive to the nuances of places and people”. Comhairle nan Eilean Siar argued for the consideraton of “Island Community Impact Assessments” and “Island Proofing” to be undertaken to ensure healthcare policies reflected the specific circumstances of island communities.

During informal engagement, patient campaign groups argued that the impact of certain policy approaches on people and staff in remote and rural areas needed to be more carefully considered. Participants raised concerns that equality impact assessments can often fail to reflect the reality on the ground.

Third Sector involvement

Organisations, including Hospice UK and Marie Curie Scotland, emphasised the importance of third sector involvement in service design and delivery.

Hospice UK highlighted the role that hospices have to play in “providing education and training, and clinical expertise and support, to the wider health and social care workforce.”

In its written submission, Marie Curie Scotland also stated:

The third sector plays a key role in integrated services but is not seen as an equal partner and is often not included in early conversations with existing Integration Authorities regarding the strategic planning and commissioning of palliative care services.

In evidence to the Committee on 28 November, Dr MacGilleEathain further emphasised the important role of the third sector in delivering services. She argued that, in her experience, much of the good practice to be found in remote and rural areas actually comes from third sector organisations rather than the NHS and that greater efforts should be made to learn from this:

There are a lot of good third sector organisations that are supporting people’s health, so we in the NHS do not necessarily always know what is going on. That is one of the issues: it is about finding out what they are doing, perhaps through word of mouth. Rural and remote communities work like that sometimes. We may find out that there is a good third sector organisation that is supporting people’s health well and has a really good model, so we need to investigate and understand how that works, and take learning from it. Sometimes it can be bit of a barrier if the organisation is from the third sector rather than the NHS.

The Committee calls on the Scottish Government in responding to this report to set out what it is doing to combat silo working in the delivery of remote and rural healthcare services, to promote a whole-system approach and to design services in a way that is more flexible and responsive to local needs and circumstances.

The Committee commends existing good practice in the provision of remote and rural healthcare services demonstrated by third sector organisations. It calls on the Scottish Government to set out what it is doing to systematically capture any such examples of good practice and to disseminate these more broadly across all remote and rural areas.

Primary Care and Multi-Disciplinary Teams (MDTs)

The Committee heard extensive evidence throughout the inquiry of the more acute issues facing primary care in remote and rural areas.

2018 General Medical Services (GMS) Contract

One of the common themes emerging through evidence from those engaged with the inquiry was the particular challenges being faced in implementing the current 2018 General Medical Services (GMS) Contract, or GP contract, in a remote and rural context.

In response to the call for views, the Nairn Healthcare Group raised particular concerns about the financial viability of applying the independent GP contractor model in remote and rural areas:

“Current funding models disadvantage remote and rural health care provision and take too little account of the additional costs to maintain and develop services in remote and rural settings. The lack of strategic and financial investment into the Independent GP contractor model has seen many GP practices decide the business model is simply no longer financially viable and have handed back their 17J contracts back to Highland Health Board who are now forced to run services and estimated costs 2-3 times higher than before. This is hardly a model for sustainable provision of GP in remote and rural areas.”

The GP contract was also a key issue raised during an informal engagement session with rural GPs. While acknowledging that the GP contract had “noble foundations”, participants reported having subsequently encountered problems since its introduction. Many expressed the view that the contract was impossible for remote and rural practices to deliver and was not geared towards supporting the delivery of an independent contractor model in a remote and rural context.

One participant argued that implementation of the contract has had a detrimental effect on health outcomes and has resulted in a widening disparity between remote and rural and urban healthcare provision. They cited vaccination programmes, including for measles, as an example, where the practical effect of removing this responsibility from GPs and reallocating it to vaccination centres was, in their view, increased cost, lower levels of uptake and poorer outcomes.

In evidence on 28 November 2023, Dr MacGilleEathain, Research Fellow at the Division of Rural Health and Wellbeing, University of the Highlands and Islands, outlined in further detail the impact in remote and rural areas of this change of approach to the provision of vaccinations and other routine aspects of patient care, brought about by the 2018 GP contract :