Education and Skills Committee

Children's Hearings System - Taking Stock of Recent Reforms

Introduction

The Children's Hearings (Scotland) Act 2011 ("the Act") brought about major reforms to the Children's Hearing system in Scotland. The Act (which came into effect in 2013) made mainly structural changes to the hearings system. The main aims of the changes were to modernise and streamline the operation of the system, deliver greater national consistency and simplify the provisions for warrants and orders.

The main changes were:

Creating a national body, Children's Hearings Scotland, to recruit and support panel members, headed by the National Convener;

Creating a national Children's Panel (in place of separate panels in each local authority), supported by 22 Area Support Teams;

Creating a national Safeguarder Panel;

Providing for the development of an advocacy service for children in the hearings system (this has not been brought into force);

Providing for the amendment of the Rehabilitation of Offenders Act so that offence grounds accepted or established in children's hearings (other than for certain serious offences) are no longer classed as a conviction (this has not been brought into force);

Introducing access to legal representation through the Scottish Legal Aid Board;

Providing for a “feedback loop” to allow collection of information about the implementation of Compulsory Supervision Orders; and

Revising some of the grounds for referral to a hearing, including introducing new ground in relation to domestic abuse.

The Children’s Hearings system is administered through 2 Non-Departmental Public Bodies, the Scottish Children’s Reporter Administration (SCRA) and Children’s Hearings Scotland (CHS). SCRA was formed under the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1994 and continued under the 2011 Act. It became fully operational on 1st April 1996. CHS was formed under the 2011 Act and became fully operational on 24 June 2013.

Since the reforms brought about by the Act, the Scottish Government, CHS, SCRA and other partner bodies have sought to make continuous improvements to the Children's Hearings system. Most recently, under the banner of the Children’s Hearings Improvement Partnership (CHIP).

This Report

This Report sets out the findings of the Committee's short inquiry to take stock of the reforms brought about by the 2011 Act and how they were being implemented. The Report is a contribution to the work of the Scottish Government and others as part of the Children's Hearings improvement process.

Evidence taken

To help prepare this report, the Committee took evidence from a range of different witnesses, including the Minister for Children and Early Years, many of the key organisations involved in the Hearings system and children's charities (see Annex A). We also heard informally from a group of young people with direct experience of the Children's Hearings system who spoke to the Committee in sessions arranged by Who Cares? Scotland and Barnardo's Scotland. Finally, we were also able to speak to representatives of the Scottish Guidance Association about their experiences.

In addition to our oral evidence, the Committee received 18 written submissions of evidence (see Annex B).

The Committee is grateful to all of those witnesses, organisations and individuals who provided their views to us.

Membership changes

During the Committee's deliberations on this Report, Fulton MacGregor MSP and Richard Lochhead MSP were replaced on the Committee by Clare Haughey MSP and Ruth Maguire MSP.

The Children's Hearings System - background, key facts and figures

About the Hearing System

The structure of the hearings system is based around Reporters, employed by the Scottish Children’s Reporter Administration, and volunteer panel members supported by Children’s Hearings Scotland who make decisions at hearings and local authorities which implement hearing decisions.

The following gives a brief overview of the main stages of a hearing. Throughout, procedures are informed by the key principles of the system which are:

the welfare of the child is the paramount consideration;

an order will only be made if it is necessary (i.e. the state should not interfere in a child’s life any more than is strictly necessary); and

the views of the child will be considered, with due regard for age and maturity.

The hearing should have the character of a discussion about the child’s needs. A sheriff court is generally only involved if grounds of referral are in dispute or not understood, a child protection or child assessment order is required or there is an appeal against a decision of a hearing. The aim is to balance the ‘lay’ character of the system with the guarantees of individual rights afforded by a court system.

Anyone can make a referral to the Reporter, but in practice most referrals are made by the police. The Reporter investigates and decides whether a hearing is required. This decision is based on whether there is sufficient evidence that a statutory ground for referral has been met and if so, whether compulsory measures of supervision are needed. If a hearing is required, the reporter arranges one and three members of the children’s panel are selected to form the hearing.

At the hearing, the grounds for the referral must either be accepted by the relevant persons and child or established by the sheriff in order to proceed.

A safeguarder, whose role is to protect the child’s interests, can be appointed at any time during the hearings process. A child or relevant person can be represented at a hearing and there is state funding available in particular circumstances for legal representation.

Interim orders can be made, but the main decision of a Hearing is whether a Compulsory Supervision Order is required. This states where a child is to live and can include other conditions such as contact arrangements or support services required. Because these are compulsory measures there is strict legal oversight of the process including provision for legal representation and appeals. It is necessary to get the right balance between informality and protecting the legal rights of those involved. This has led to the extension of legal aid in order to protect participants’ ECHR rightsi.

The local authority must implement a Compulsory Supervision Order.

In 2011, the then Scottish Government passed the Children's Hearings (Scotland) Act 2011. This made mainly structural changes to the hearings system, the details of which are set out above in the Introduction section of this Report.

Statistics and trends

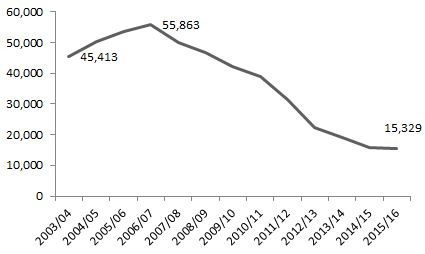

When the Children’s Hearings system started in the early 1970’s, there were around 20,000 referrals a year. After years of steady slow increase there was a dramatic increase in the 2000’s to a peak of nearly 56,000 in 2006/07. Numbers of referrals have since declined steeply to their current rate of around 15,000 per year.

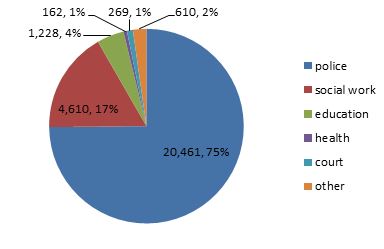

Most referrals, around 75%, continue to be from the police, followed by social work (17%) and the education system (4%); see chart below.

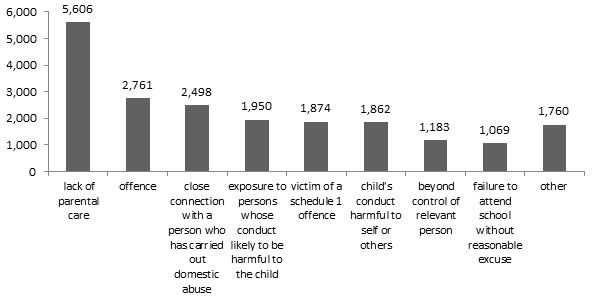

Since the early 1990s, most referrals have been on ‘care and protection’ grounds rather than the ‘offence’ ground. In 2015/16 around a fifth of referrals were on ‘offence’ grounds compared to 39% ten years previously.

By far the most common statutory ground for referral is ‘lack of parental care.’ In 2015/16, over a third (36%) of children referred were referred on this ground. The next most common ground was the child having committed an offence (18% of children referred), followed by “close connection with a person who has carried out domestic abuse (16% of children referredi).

Reducing the number of unnecessary referrals has been a policy focus for a number of years and is connected to the development of Getting it Right for Every Child (GIRFEC).

The number of referrals does not necessarily indicate the level of work for panels - only around a quarter of referrals in 2015/16 result in a Hearing being arranged (26% in 2015/16). There were over 35,000 Hearings held in 2015/16. Most of these (22,502) were to review Compulsory Supervision Orders. Only 8,937 were to consider a statement of grounds (SCRA statistical analysis).

In 2015/16, Hearings made 3,042 new Compulsory Supervision Orders. Compulsory Supervision Orders are not intended as long term arrangements, but can become so in practice. As at March 2016, around a fifth (21%) of the 10,379 CSOs in place had lasted for 5 years or more (Table 5.3, SCRA statistical analysis). A policy focus across children’s services in recent years has been to reduce the time taken to achieve ‘permanence’, whether that permanent arrangement is settled at home with parent(s) or away from home in long term kinship, foster, residential care or adoption.

Legal Aid

Prior to the 2011 Act, access to legal aid was restricted and available only to individuals who needed advice about children's hearings. It covered provision of advice only, it did not allow for representation at children's hearings. The 2011 Act changed this; see above. It is important to note that solicitors were present at some hearings prior to 2011 if an individual was able to self-fund or obtain such support on a pro bono basis.

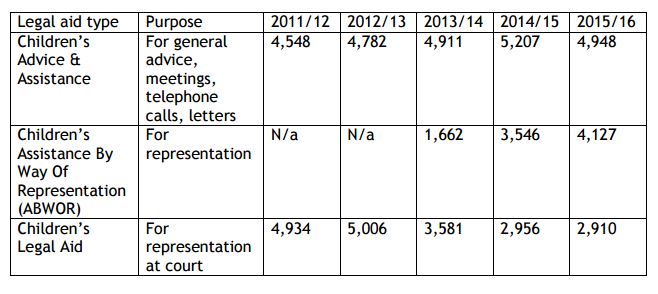

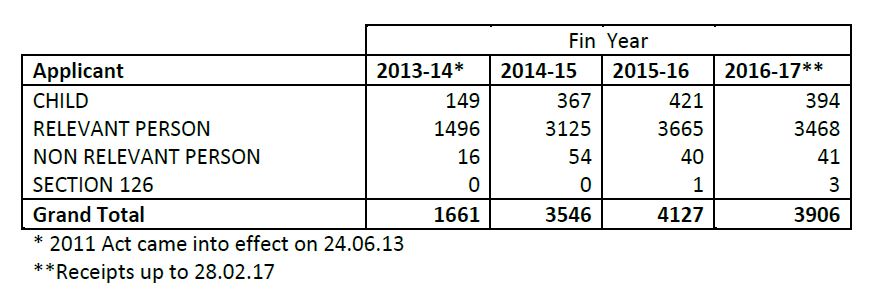

The table below shows grants of legal assistance for the five-year period shortly after the implementation in June 2013 of the legal aid-related aspects of the 2011 Act.

Additionally, the following tables sets out information on the number of granted applications to the Scottish Legal Aid Board.

Key Issues

Children's Participation and Improvements to the Hearings Process

A key element of the children's hearings system is that children should actively participate in the hearing insofar as their age and maturity allows. The children’s hearings system was introduced in 1971 following the Kilbrandon Report of 1964 and the Social Work (Scotland) Act 1968. Kilbrandon recommended a welfare based system to provide an integrated approach to children who had committed offences and children in need of care and protection. It assumes that the child who has committed an offence is just as much in need of protection as the child who has been offended against. It is a lay tribunal which does not have the formality of the normal courts.

The legislation was substantially revised in the Children (Scotland) Act 1995 and the Children's Hearings (Scotland) Act 2011. At all stages, there is supposed to be an emphasis on improving the participation of the child in question and ensure their voice is heard.

The Committee is aware that the Scottish Government and others have initiated a series of initiatives to improve the way that the children's hearings process works. This includes the formation of the Children's Hearings Improvement Partnership and the work undertaken by it. Part of this work included the publication in October 2016 of a research report on The Next Steps Towards Better Hearings. Other work is also underway looking at the Blueprint document, which sets out a Code of Practice and associated standards and targets for children's hearings.

In addition to the above, the Scottish Government is looking more widely at children's services, children in care and has established the Child Protection Improvement Programme.

Views of a selection of young people with direct experience of the Children's Hearings System

As part of our evidence gathering, the Committee was privileged to hear from a small number of young people - aided by Who Cares? Scotland and Barnardo's Scotland - who had had direct experience of children's hearings in their own personal lives. A non-attributable note of the meeting is set out in the Annexes to this Report.

It is worth, however, highlighting here some of the personal views expressed to us as they highlight a substantial number of the issues that follow in this report (paraphrased below) and, additionally, as they chime with much of the evidence we took from professional bodies and interested parties.

The Children's Hearings system was a good experience for me. Although I felt scared at first because I was unsure of what was going to happen, the support from my carers, social worker, guidance teacher and the family support worker from Barnardo’s have helped me to get through. I felt listened to because I had support.

The support worker, social worker and the carers that helped me have been the same people over the last few years. This continuity has helped me to understand what was happening. In particular they have made sure that I have regular contact with my younger siblings.

I feel my voice is heard when I get a chance to speak to my advocacy worker beforehand so they can speak up for me and use my words. That helps. The form I can fill in with my views is useless and no-one reads it. I was 16 years old before I even knew I could even talk to the panel. We weren't told we could do that. I would have participated better if I knew I could speak to them, but I didn't, so I just kicked off.

It's never the same people on a panel. The whole panel thing is really intimidating with all these strangers sat behind a big table. If you keep the same panel members, I think they would learn more about me. Panel members have to stay in the room, they can't even come and introduce themselves beforehand. And we don't even know anything about them, can't we have a bit of information about them to break the ice?

It's horrible waiting around for things to start. The longest I've waited is 2 hours. There's nothing to do. There was only broken toys to play with. It's a horrible environment. The hearing rooms could be more colourful, less intimidating with comfy seating etc. and get rid of the big table.

When I was attending hearings, I just wouldn't read things like all the reports. Things should be in easy-read form, summarised with more information available to those that want it if they are older and able to read it. It's also quite hard to get access to all the documents written about you.

Improvements to the Hearings Process

As can be seen from the anecdotal evidence set out above from the young people that we met, there are further improvements that can be made to how panels are run and how the wider children's hearings system functions.

One suggestion in this area is to look more closely at continuity of membership of a panel to seek to ensure that all or at least some of the panel members are present throughout the entire process for a given child or young person who may have to attend multiple hearings.

The evidence from Social Work Scotland is typical of what the Committee heard in this area. It said—

We recognise that turnover and maintaining the range of knowledge and skills of panel members can be challenging. Inconsistencies of panel members at each subsequent hearing can also be difficult and lead to inconsistencies of decisions for children.1

These views were shared by NSPCC Scotland and the Glasgow City Health and Care Partnership in their submissions to the Committee. As the NSPCC Scotland point out, "there is an issue with continuity of decision-making in that panel members frequently change throughout the process; seldom are the individuals involved in reviewing decisions the individuals who made them."2 Similarly, in her submission, independent social worker Maggie Mellon wrote —

Nowadays it is the norm for completely different panel members to be convened to hear a case every time a child and family come before a hearing. There is little continuity, information that is asked for by one panel will be disregarded by another, forgotten by a third, and then asked for again at a fourth.3

Giving evidence to the Committee, the Minister for Children and Early Years, Mark McDonald MSP, said—

There is always a balance to be struck, because the panellists are volunteers who give of their time to support the children’s hearings system. Depending on when cases are coming back, particularly because a decision has been appealed or grounds have been agreed, having the same panel members throughout the case might lead to delays if scheduling depends on their availability.

Education and Skills Committee 29 March 2017 [Draft], Mark McDonald, contrib. 24, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=10879&c=1989309

When questioned further, the Minister gave the following commitment that he would "certainly give it some consideration and look into the logistical practicalities."5

In addition to continuity of panel members, the issue of the number of people who attend panels was a commonly raised point in a lot of the evidence we took. In addition to panel members, parents, solicitors, teachers, the police, social workers etc, Social Work Scotland reported that—

... decision making with respect to who can attend a Hearing has led to situations where parents have been allowed up to 4 support people each for parents (not relevant professionals – friends, their mum, advocates). This is not helpful as it can overwhelm the child and the Hearing becomes unbalanced and biased towards the parents.1

It is not immediately clear why such an expansion in the numbers of people attending a hearing is being permitted. As Morag Driscoll of the Law Society of Scotland points out in her evidence—

The Scottish statutory instrument that sets out the rules of procedure is helpful on that point. According to rule 6, the chairing member has a duty to keep the number of people in the room at any one time to a minimum. That provision could be used more creatively to find out whether all the people in the room need to be there and whether we need, for example, three social workers—plus a lawyer for the social workers, which is becoming a slightly worrying trend.

That provision is already there. The act and the statutory instruments are something that we should all be slightly smug about in Scotland. They give us quite a good system.

Education and Skills Committee 22 March 2017 [Draft], Morag Driscoll, contrib. 19, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=10863&c=1986638

She noted—

From the point of view of the child, one of the things that perhaps we need to do is to strengthen the guidance for panel chairs on keeping the numbers smaller. Sometimes we have a lot of professionals present, but do we need more than one representative from each field—for example, do we need three social workers and two teachers? Could we ask some people to leave the room for a bit? Can we perhaps look at that again? The act does not define “attendance” at a hearing as being in person.

Education and Skills Committee 22 March 2017 [Draft], Morag Driscoll, contrib. 30, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=10863&c=1986649adding that, in the context of too many people dominating the hearing and preventing a child from participating, we—

... have provision to reduce the number of people who have a right to be at the hearing and we also have provision to exclude a relevant person and their representative if their presence will make it impossible for the child to speak. We could make that a little easier to do because, at the moment, someone can be excluded only if their presence will make it impossible for the child to speak. We must remember that, by excluding someone, we are temporarily removing their right to be present in the hearing, so we must strike a balance in that regard.

Education and Skills Committee 22 March 2017 [Draft], Morag Driscoll, contrib. 90, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=10863&c=1986709

The third key area that could be improved is the reports and paperwork prepared for hearing, particularly from the perspective of how accessible this material is to a child or young person. In most cases, a typical hearing will see reports, some of great length and complexity, prepared by a number of participants in a hearing such as the child's social worker, teacher, child psychologist etc. As the Law Society of Scotland points out in its written evidence—

Requiring those submitting reports to the hearing to provide a simpler version for the child that is appropriate to his or her age and stage. This would make it easier for children to understand the information being provided to the hearing and the recommendations. The “child-friendly” versions could also be provided to children under the age of 12, which is the age at which reports are provided. The child will thereby be better able to understand the process and to form a view. 10

This view was shared by many others who gave evidence to the Committee. For example, Morag Driscoll, who suggested that a one-page, accessible summary for each report could be produced and that this could be implemented immediately.11 This proposal was also suggested by Clan Childlaw, a community law advice network, which commented that consideration should be given to enabling the child to provide a written submission to reports and an account of their views for the hearing along with the other papers before the hearing and that that any such submission would have equal standing.12

In his response to a proposal of this nature - a child-friendly summary of the reports - the Minister said—

That is a very sensible suggestion and I am happy to look into it. Certainly, if we want the system to have children at its heart, children have to be able to understand the process that they are involved in. I will take that suggestion away and look into it.

Education and Skills Committee 29 March 2017 [Draft], Mark McDonald, contrib. 45, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=10879&c=1989330

The Committee also heard from some of the young people that we met that they were unsure or unaware of their right to speak at a panel meeting and address the members, as well as to be engaged with in an suitable and age-appropriate manner. As one young person put it, it was only after attending a number of hearings over a number of years was she finally made aware that she had the right to speak and put her point of view across to panel members. In response to this point, the Minister said—

... it needs to be emphasised in the training that young people have to be made aware of that opportunity because, as you rightly highlighted, if they have it, that can set them at ease for the process that is about to be undertaken. My expectation is that that would be clearly emphasised to panel members as part of their training.

Education and Skills Committee 29 March 2017 [Draft], Mark McDonald, contrib. 53, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=10879&c=1989338

The question of the child or young person's right to participate and speak if they wish was linked in some of the evidence to the question of whether there were times when it was appropriate for this to be done in different ways that didn't always include being physically present throughout all hearings, especially when this could cause distress.

The role of technology and the set-up of rooms and waiting areas were key to this issue. In his evidence, the Minister noted that he had set aside £2.5m in the coming budget for the Scottish Children's Reporter Administration and the Children's Hearings Scotland to develop a joint digital strategy to see if technology - such as participating remotely by Skype - could be utilised to improve the experience for children and young people.15

The benefits of this approach were articulated by Malcolm Schaffer of the Scottish Children's Reporter Administration in his evidence to the Committee. He said—

We are embarking on a three-year digital strategy for the hearings system. As part of that, we will be looking at whether there are other means by which children can participate in hearings without physically being in the hearing room. Are there electronic means? Is videoconferencing appropriate? Are there other mechanisms by which we can ensure that the child’s views are properly submitted to a hearing in advance? The traditional way to have your say is to submit a written form, but we need to get beyond that and consider whether more advanced technology can be used.

We need to think about those means and we also need to consider whether the child should be present throughout the hearing, whether they are physically there, or whether more use could be made of arrangements to ensure that children need to be there only for a minimum period of time and can be excused from parts of the process.

Education and Skills Committee 15 March 2017 [Draft], Malcolm Schaffer, contrib. 74, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=10849&c=1984617

He also outlined the efforts to look at the set-up of the buildings and rooms that are used for panel meetings, commenting—

We are involved in a programme of redesigning our hearing rooms, having taken advice from young people. In particular, following their advice, we have removed the big table and have provided rather more comforting soft furnishings and colours. Perth, Inverness, Glasgow and Irvine have examples of that, and we hope to take that approach in more centres. If committee members would like to visit any of those hearing rooms, they should feel free to do so. I have observed hearings in those rooms, and they really make a difference.

Other changes that are being looked at include the provision of toys and play areas for young people; different waiting rooms for different types of young people, such as older and younger ones; and interview rooms where people can speak to children and young people before and after the hearings. We are putting quite a lot of effort into those changes, and we believe that the early results demonstrate exactly what you said—that a more comfortable environment for the holding of hearings helps to reduce tension and formality.

Education and Skills Committee 15 March 2017 [Draft], Malcolm Schaffer, contrib. 104, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=10849&c=1984647

There were a small number of other areas suggested to the Committee in the evidence we took where some felt improvements in the Children's Hearings system could be made.

Firstly, on the issue of participation, and of very young children and babies, CELCIS and the NSPCC Scotland questioned how this could be achieved. It is one of the fundamental principles of the system that the child must be given an opportunity to express a view, and those views should be taken into account in accordance with the age and maturity of the child. It is their experience that hearings can often cause a child undue distress. They consider that physical attendance in these circumstances is "seldom helpful" and an unreliable way of gauging what a child thinks.2

On a different matter, but also one related to very young children and babies, CELCIS and the Centre for Youth and Criminal Justice at the University of Strathclyde raised a concern. They noted that the length of time it can take to establish ‘grounds’ (legal reasons which may lead to the requirement for a Children’s Hearing, set down in section 67(2) of the 2011 Act) for some children aged 0 to 5 was problematic. It can take many months to establish grounds for example, for a baby whose parents have failed to safely care for a previous child. 19

They noted that, in their view, the Children’s Hearing system was not established to consider the needs of babies and infants, nor was it established to consider the likelihood of harm and the challenge of trying to demonstrate this before actual harm has occurred. CELCIS and the Centre for Youth and Criminal Justice suggest that and additional ground relating to ‘a previous child having been removed from a parent’s care’ is required to best support our most vulnerable young children.

At the other end of the age spectrum - young people between 16 and 18 years of age - CELCIS and the Centre for Youth and Criminal Justice suggest that there are also problems, particularly after a termination of a Community Supervision Order (CSOs) on or around the individual's 16th birthday. They noted that—

A research study found 79% of young people interviewed in Polmont Young Offenders Institute had previous involvement with the Hearing system. 59% stated that their CSO had been terminated just prior to or just following their 16th birthday, meaning their court cases were dealt with within the adult justice system. 19

In their view, more work needs to be done to explain to young people the processes they are involved in, as well as educating the workforce and panel members around the importance and purpose of children remaining on CSOs longer.19

In his evidence to the Committee, Mark Allison of law firm Livingstone Brown, suggested that there was an issue with recourse to kinship care and that these could be prioritised by panels. He said—

My concern, based on my practice, is that kinship is often viewed as a solution only when we have absolutely excluded rehabilitation. It is a long-term solution, but it can be thought of as a short-term solution while we are inquiring as to whether parents can care for their children appropriately or whether there are problems. I feel that that is missing from the system, and the only circumstances in which those relatives are able to participate is when they can show that they have, or have had, significant involvement in recent times. There is a small group of relatives, including grandparents and others who offer to be the alternative carer, who are probably not represented as often as they should be, because they have a viable option. The legislation tells us—although it is not expressly set out; perhaps it should be—that before long-term foster care, the port of call should be kinship care. That is one area in which there is a lack of focus.

Education and Skills Committee 22 March 2017 [Draft], Mark Allison, contrib. 55, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=10863&c=1986674

In its Guidance on the Looked After Children (Scotland) Regulations 2009 and the Adoption and Children (Scotland) Act 2007, the Scottish Government emphasises the use of kinship care. It says "the child's extended family and friendship network should normally be the first option considered for a potential placement".23 This guidance is for social work when considering the best placement for a child, whose recommendations should inform the work of the Panel.

In its evidence to the Committee, Families Need Fathers suggested that some panels were reluctant to take final decisions on a case. It said—

This is sometimes attributed to a reluctance to make decisions with repeated continuations for further reports being ordered but with no clear instruction to any of the parties about what would constitute progress or resolution where there is disagreement about the facts of the case.24

In its evidence, the Adoption and Fostering Alliance (AFA) Scotland questioned whether it was necessary to hold advice hearings to provide a court with advice from the Children’s Hearings in respect of children who are subject to compulsory supervision Orders and where local authorities intend to apply to the courts for Permanence Orders with or without authority to adopt and where local authorities are aware that adoption petitions are being lodged in Court. Its view is that "this additional step in the process seems to serve no useful purpose, causes an unnecessary interference into family life and creates delay."25 AFA Scotland also raised questions regarding the second stage of interaction between the courts and children’s hearings in in relation to sections 95 and 96 of the Adoption and Children (Scotland) Act 2007.

One final area raised in the evidence to the Committee is that of possible extensions to the grounds for referral to the system to include the suggestion of female genital mutilation (FGM) or people trafficking. In its submission, the Law Society of Scotland made this suggestion.10

Training and the Role of Panel Members and Chairs

The question of the training and guidance available to members of children's hearings panels and also that, in particular, to the chair of the panel and the important role that they play in setting how a hearing will run, were key issues in the evidence we took.

Children's Hearings Scotland (CHS) told the Committee that approximately 500 panel members are recruited across Scotland each year in order to maintain the necessary number of volunteers. At any one time, there are around 2,500 volunteer panel members who sit on around 35,000 children's hearings per year. On average, a panel member will sit in on 14 hearings sessions per year, averaging 3+ hours each. Each session may cover 3 individual hearings.1

CHS told us that each new recruit has to attend and complete a 7-day pre-service panel member training programme before they can be put into service as part of the national Children's Panel. Since 2013, all new members are required to complete an SQA Professional Development Award within the first term (three years) of their appointment (approximately 120 hours of study). In 2016, the National Convener established a core training programme of 6 modules over 3 years. The topics are: effectively communicating with children and families, managing conflict in children’s hearings, attachment and resilience in looked after children, revisiting decisions and reasons, the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014 and GIRFEC, and Information Governance.1

In addition, panel members are encouraged to attend learning and development sessions within their local area organised by the Area Support Team. These sessions may include contributions from e.g. the local children’s reporter, social work department, education or third sector organisations.1

CHS has also established a set of 8 national standards for panel members and publishes practice and procedures manuals, common training manuals etc.

The importance of such material was highlighted by CELCIS and the Centre for Youth and Criminal Justice. They said that panel members and all professionals attending Hearings would benefit from clear national guidance, and continuous professional development, to gain a deeper understanding of the purpose of contact with birth families, to inform legal decision making.4

Of particular interest to the Committee is the training that panel members obtain in order to chair a panel. As the National Convener, Boyd McAdam, notes—

Chairing is a critical role in the system and we provide management of hearings training for new panel members. Part of the core training is managing conflict within hearings. Even if a panel member is not in the chair role, they are there to support the chair and they have to have the confidence to manage the difficult behaviours that occasionally arise in hearings, as well as an understanding that the role of a panel member is to move forward and take a decision.

Education and Skills Committee 15 March 2017 [Draft], Boyd McAdam, contrib. 84, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=10849&c=1984627

The ability of the chair is critical. As Jennifer Davidson of CELCIS told the Committee—

When chairs are effective, strong and skilled and they have the confidence to manage the room, it is an effective process for children and it ensures that panels make good decisions for them. Where the chair lacks confidence, it becomes a much more risky situation for the decision making.

Education and Skills Committee 15 March 2017 [Draft], Jennifer Davidson, contrib. 65, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=10849&c=1984608

Similarly, in her evidence to the Committee, Daljeet Dagon of Barnardo’s Scotland, said “we need to support our panel members much better so that they feel stronger and more confident when it comes to managing the hearing.”7

In its evidence to the Committee, Social Work Scotland makes the point that all panel members, include chairs, are currently volunteers and posed the question on whether chairs should become more professional.8 This was also a point made by Glasgow City Health and Social Care Partnership which said—

There is concern about the ability and expectation on lay panel members to chair the complexity of increasingly complex and adversarial hearings. It was suggested a professional chair could avoid this issue. 9

Children 1st raised the more fundamental question of whether increasing complexities called into question the system being based on lay volunteers. It said—

Where panel members were previously able to focus purely on children’s needs, they now face the challenge of having to carefully balance the rights of adult parents and carers with children’s rights while continuing to hold the child’s needs at the centre of the decision-making process. This demands an increased level of skills and capacity on behalf of the panel and has led to debate about whether panel members and/or Chairs should remain as lay people.10

Responding to these points in the Committee, the Minister said—

There is mandatory training for chairs on the management of hearings, communicating effectively with children and families, managing conflict in hearings, attachment and resilience, revisiting decisions and reasons, the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014, and getting it right for every child. Contained within those themes are some of the points that Daniel Johnson raises. It comes down to assessing and analysing the effectiveness of the chairs.

Essentially, there is a feedback system whereby panel members and reporters can look at how chairs have performed. Often, we will not know for sure how effective a panel member will be at chairing a hearing until they do it, so that is an element. We are putting in place much more training and capacity building for chairs of hearings to ensure that they have the confidence and the competence to be able to address the issues that you raise.

Education and Skills Committee 29 March 2017 [Draft], Mark McDonald, contrib. 30, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=10879&c=1989315

The need for ongoing review of the training requirements of panel members was made by some organisations to highlighted the increasing complexity of cases being dealt with by the system. As SCRA noted—

We note that while referrals have reduced in number, the complexity of cases and the numbers of very young children referred to the Reporter have increased. To some extent increased complexity is a by-product of seeking to ensure a human rights-compliant system, along with an increasingly sophisticated understanding of children’s needs. 12

The Committee also took evidence about the availability of panel members in different parts of Scotland, with particular concerns about remote or rural areas. Responding to this point, the Minister noted that whilst there had just been a new recruitment exercise, which was specifically designed to ensure that we have sufficient numbers working in the system, there were "regional variations in the system". He recognised that there will be requirements in other parts of the country to recruit additional panel members. He added—

It is undoubtedly the case that there are some locations, by dint of population, where there are challenges—I would say challenges rather than difficulties—in ensuring consistent recruitment of panel members. However, I am considering that issue and it is also an active consideration for Children’s Hearings Scotland.

Education and Skills Committee 29 March 2017 [Draft], Mark McDonald, contrib. 26, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=10879&c=1989311

Finally, as we shall see in the section that follows on the role of solicitors in the system, the suggestion that there should be more multi-agency training across the different professions involved was a common feature of the evidence we took.

CELCIS and the Centre for Youth and Criminal Justice wrote that the importance of high quality, well-managed, inter-professional training and ongoing coaching to ensure the full and shared understanding of the primacy of children’s participation, the variety of ways this can be achieved, and to foster a culture and ethos where their needs and voice are truly central, cannot be understated. They said, such training should ensure that there is mutual understanding of roles and responsibilities in the children’s hearings system, and that there is an emphasis on the collaborative, child-centred ethos of the hearing process. They argued that this training should foster a culture of mutual respect for all parties.4

Similarly, the Scottish Legal Aid Board (SLAB) argued that work should be undertaken to establish and promote high quality, well-managed, inter-professional training. Such training should, in its view, ensure that there is mutual understanding of roles and responsibilities in the children’s hearings system, and that there is an emphasis on the collaborative, child-centred ethos of the hearing process. SLAB suggests that this training should foster a culture of mutual respect for all parties. In due course, they suggest that this training might usefully become part of any compulsory training that is developed, as well as being available on an on-going basis. 15

The Minister himself was in agreement with the comments made to us and outlined some of the work already underway on this subject, such as the multi-agency training on Getting it Right for Every Child that is taking place in Glasgow. He suggested that this could be rolled out to Edinburgh and other large population centres. He also indicated that he'd look carefully at whether care-experienced and young people who have had experience of the system could be involved in the training on offer.16 This principle could be extended to the recruitment process of panel members and the Minister said he would give this "consideration".16

Advocacy & Safeguarders

Section 122 of the 2011 Act requires the chair of the children’s panel to inform the child of the availability of children’s advocacy services. It also provides for Scottish Ministers to make regulations about the provision of children’s advocacy services and enables Scottish Ministers to enter into arrangements with organisations (other than local authorities, CHS or SCRA) for the provision of children’s advocacy services.

This section of the Act has not been brought into force. It was added by amendment during stage 3 of the Bill (amendment 61, agreed 24th November 2010), and followed amendments on the same theme at Stage 2. During the stage 3 proceedings, Adam Ingram (then Minister for Children and Early Years) stated that there is still no consensus on exactly what support is needed or who should provide it. He said then that it would be important to ensure that the right support is available and that the arrangements for providing it are effective and proportionate. In his view, all that detail can be set out in the regulations once that has been decided. The then Scottish Government consulted on children’s hearings advocacy in November 2011.

The consultation analysis, published in December 2012, concluded that—

There was a great deal of support for the Scottish Government's efforts to improve advocacy provision for children and young people among the respondents to this consultation. However, respondents' comments often suggested that, in their current form, the proposed principles and minimum standards could only be understood as aspirational. Many struggled to see how the proposals could be implemented in practice.1

At present, although s122 of the 2011 Act is not yet in force, there are a number of pilot schemes providing advocacy services. For example, Barnardo’s Independent Advocacy service was set up as an action research project with a view to provide advocacy for children between the age of 3 and 17 years of age who were referred by the Children’s Reporter for an Initial Children’s Hearing. The pilot was run in Fife and evaluated in March 2016. Similarly, Who Cares? Scotland offers advocacy across most of Scotland’s local authorities and provides a special advocacy service to some organisations providing care on behalf of local authorities.

In their evidence to us, Barnardo's Scotland told the Committee that—

Our advocacy work shows that what works best for children and young people in terms of their participation is a consistent relationship with a professional they can trust. It is important that children are able to form relationships with those supporting them, and in our experience the system is not always designed to allow this to happen.

The children and young people we work with tell us that they feel reassured and supported knowing their advocate will be with them every step of the way. Advocates can help children understand the language and terminology used in Hearings which is not always child friendly; this helps with participation if children and young people have a better understanding of what is going on, however not all children are able to access independent advocacy services. 2

Additionally, the Law Society of Scotland told the Committee of its plans to make advocacy more widely available. Morag Driscoll informed the Committee that the Society was—

... also looking at making advocacy for children much more widely available, and to a professional standard. Children do get talked over, but that happens in hearings with no lawyer present as well. The role of the advocacy worker in keeping the child informed, participating and not feeling like the bone between the dogs must not be underestimated.

Education and Skills Committee 22 March 2017 [Draft], Morag Driscoll, contrib. 21, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=10863&c=1986640

Whilst supportive of advocacy services, SCRA did provided a word of caution. It said, "While we are fully supportive of the advocacy agenda therefore, we are wary of any suggestion that there might be “silver bullet” solutions suitable for all children and young people."4

For his part, the Minister noted that—

We have not yet enacted section 122 of the 2011 act, which sets out a requirement for the chair to inform a child or young person of the availability of advocacy. We are operating pilots in Fife and North Lanarkshire to look at how that will be taken forward. I recently agreed to provide funding for those pilots. That is with a view to creating a sustainable advocacy system that can be rolled out nationally by enacting section 122. I understand entirely the important role that advocates can play but, if we are going to introduce the availability of advocacy nationwide, it is important that we absolutely get it right and ensure that children are well served by it.

Education and Skills Committee 29 March 2017 [Draft], Mark McDonald, contrib. 34, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=10879&c=1989319

The Minister also committed to considering the question of whether hearings should proceed in the absence of anyone available whom the child or young person in question considers is an advocate for them, whether this be an advocate in the strict sense of the word or a teacher, friend, local authority worker etc.6

The Committee also took evidence on the role of safeguarders. Safeguarders have been part of the Children’s Hearings system for over thirty years. Appointed by Scottish Ministers, safeguarders are asked to provide Children’s Hearings or courts with an independent assessment of what is in the child’s best interests. Part 4 of The Children’s Hearings (Scotland) Act 2011 placed a duty on Scottish Ministers to establish and maintain a panel of safeguarders (the Safeguarders Panel) for hearings and sheriffs to appoint from in individual cases. In 2012, Children 1st were contracted to develop and manage the Safeguarders Panel on behalf of Scottish Ministers.

In their written evidence to us, Children 1st said that they had been working with the Scottish Government to introduce a transparent and accountable process for recruitment, selection and training of safeguarders and to manage safeguarder allocations, complaints, fees and expenses. Most recently, Children 1st’s Safeguarder Panel Team has worked with safeguarders and Scottish Ministers to create a set of minimum Standards for safeguarders and a Framework for their support and monitoring against these Standards. Safeguarders are now assessed for reappointment. In combination, Children 1st believes that these changes have created a national Safeguarder Panel with increased transparency and accountability for the children and stakeholders it serves.7

In its submission. Social Work Scotland said of the safeguard provision that—

Some of our members have experienced an increasing trend towards appointing a safeguarder to represent the views of the child but it is not always clear how successful this is. There are instances where a safeguarder has barely spoken to the child but panel members feel reassured that their opinion of the child’s views are more valid than foster carers, social worker and school. There may be merit in exploring this further with panel members as the involvement of a safeguarder is often attributed to disagreement between social work and the families when in reality it can be about families disagreeing with a professional assessment.8

Commenting on research they had undertaken in this area, CELCIS and the Centre for Youth and Criminal Justice said—

With respect to the role of the Safeguarder, a 2015 study highlighted that while their work is regarded positively by both panel members and social workers, at times social workers believe that appointments of safeguarders are unnecessary, duplicate their own assessments and lead to avoidable delays. In contrast, panel members believed that the appointments were nearly always needed, and could save time in the long run. Both thought that in certain cases conflict at hearings could be better to managed to reduce the need to appoint a safeguarder.9

In his evidence to the Committee, Malcolm Schaffer of SCRA commented that, previously, there were "haphazard" systems in place in some local authorities to recruit and train safeguarders but that there is now greater standardisation and openness.4 This was something welcomed by Kate Rocks of Social Work Scotland and East Renfrewshire Council in her evidence to the Committee. She commented that—

From a local authority social work perspective, we welcome the standardisation and consistency that Children 1st has brought to safeguarding under the 2011 act. Children 1st has inherited a historical position. When safeguarders were commissioned, the standards were not on the table. Safeguarders were managed corporately within local authorities and sat outside social work services. There were lots of obvious reasons for that—for example, they needed a level of independence. A lot of hard work is going on to change the culture, but there remains confusion in Social Work Scotland about the role of safeguarders and we need to work through that.

Education and Skills Committee 15 March 2017 [Draft], Kate Rocks, contrib. 129, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=10849&c=1984672

In her view, there were still issues with delays that appointing a safeguarder can bring, with the issue of permanence planning because the default position is to ask a safeguarder and the fact that social workers do not get access to safeguarders’ reports. She called for "more clarity on the role of safeguarders".12

Role of Solicitors

The Committee’s deliberations also focused on the role of the solicitors and the impact that solicitors’ involvement had on the Hearings system. While the Committee recognises that there is a right to legal representation, concerns were expressed to us that this was, at least in some areas, making the system more adversarial and moving away from the original ethos of the system.

It has always been possible to have self-funded (or pro bono) legal representation but it is only since 2002 (for children) and June 2009 (for relevant persons) that there has been a scheme for state funded representation. The 2011 Act replaced this scheme with legal aid provided through the Scottish Legal Aid Board (SLAB). Solicitors providing children’s legal aid must register with SLAB and abide by a Code of Practice which sets out key competencies which must be met.

In his evidence to the Committee, the National Convener of Children's Hearings Scotland said that—

... only about 10 per cent of all hearings involve legal representatives. Appeals account for about 3 per cent of hearings decisions, of which about 40 per cent are successful. It is right that we consider advocacy and how we enhance the experience of young people, but we must also recognise that there is a system that is operating daily, which is supported by volunteers.

Education and Skills Committee 15 March 2017 [Draft], Boyd McAdam, contrib. 23, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=10849&c=1984566

Figures presented in a previous section of this Report show that the Scottish Legal Aid Board (SLAB) approved 3,906 applications for grants in 2016/17. This is down slightly from the previous year (4,127) but up by 230% since 2013/14 when the relevant provisions in the 2011 Act came into effect. Of the 3,906 granted applications, nearly 90% were for "relevant persons", e.g. parents.

SLAB also informed the Committee that it had received 12 complaints since 2014 regarding the conduct of solicitors and compliance with the Code of Practice for children's hearings. Of the 12 cases, 3 are ongoing, 4 were upheld, 4 were deemed no further action and one saw the firm excluded from providing legal aid under section 31 of the 2011 Act.2

In its evidence to the Committee, the Law Society of Scotland said that the involvement of solicitors in the Children’s Hearing system is "limited but essential to ensuring that the hearings are fair tribunals in accordance with rights under the European Convention on Human Rights and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child."3

In its view, the presence of solicitors "does not create an adversarial forum". The Law Society of Scotland suggested that under the Children (Scotland) 1995 Act it was considered necessary for a child for whom a movement restriction condition was in contemplation to be provided with legal representation in the same way as when secure accommodation authorisation was likely, whereas under the 2011 Act this is not the case. The Law Society of Scotland stated that any adult who is faced with this serious limitation of freedom of movement will have legal representation. In its view, it is a "potential breach of human rights legislation that children are not and serious consideration to be given to including access to automatic children's legal aid for such children."3

Similarly, Mark Allison of law firm Livingstone Brown told the Committee—

On the role of solicitors, we have to remember that the people whom we represent are largely very vulnerable, and they already have limitations, which arise from their circumstances, on their ability to play this role themselves. I reiterate that we often come into a case because a person feels that they cannot play the role themselves and that they need the benefit of representation.

[...]

We have to remember that solicitors’ work is not confined to the four walls of the children’s hearings room. We do a great deal of work to assist our clients not only to participate effectively but to focus on what is in the child’s best interests before they attend the hearing. Our clients receive large volumes of documents that many of them cannot digest properly, or they might want to raise particular issues that might or might not be central or relevant, so we have to spend a great deal of time enabling them to participate when they get to a hearing, which is normally set for only a short 45 minutes.

Education and Skills Committee 22 March 2017 [Draft], Mark Allison, contrib. 13, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=10863&c=1986632

In research cited by Jennifer Davidson of CELCIS, she indicated that the majority of solicitors who were working in the hearings system were constructive and were offering valuable input.6 Nevertheless, the Committee did hear concerns expressed by some organisations with experience of the Children's Hearings system. For example, Barnardo's Scotland said—

Solicitors are often present to represent the rights of parents, and this can lead to the rights of the child being undermined. The best interests of the child should always be at the centre but we have witnessed actions and behaviours being encouraged by solicitors which are not in the child’s best interests, for example encouraging families not to engage with support services for fear of how this might be perceived by the Panel, or encouraging unnecessarily delays.7

Similarly views were expressed to us by NSPCC Scotland and the Glasgow City Health and Care Partnership. The latter told the Committee that "many of the parents at the hearing are vulnerable and there is a sense some lawyers are exploiting these parents and driving decisions rather than taking instruction" and that "Lawyers are sometimes more focused on winning the case (rather than promoting the wellbeing of the child)."8

In her evidence, Kate Rocks of Social Work Scotland and East Renfrewshire Council said—

The system has become adversarial. If we reflect on and understand the journey into the new system under the 2011 act, none of us was prepared for having other people in the hearing rooms. We agree that it is right and proper for solicitors to be in the children's hearings system, but the necessary conditions were not around to ensure that that was seamless. For example, solicitors who were used to working in a sheriff court and with criminal law were suddenly expected to come in and manage things differently.

It is curious that the act allows for children to have legal representation. Very few children have that, which I suggest is because the vast majority of children in the hearings system now are not 12 to 16-year-olds but very young children who cannot instruct a solicitor. In some respects, our members—social workers across Scotland—are struggling with the concept of whether the system is child centred or parent centred. A fundamental discussion is needed about where the rights of the child are in the system.

Education and Skills Committee 15 March 2017 [Draft], Kate Rocks, contrib. 34, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=10849&c=1984577

The above debate was recognised by the National Convener in his evidence. He noted that—

There are many examples of where lawyers help parents to understand what their rights are and help the environment of the discussion. The 2011 act brought changes, but prior to the act there was always the challenge for panel members to create an environment to allow the child to express their view. Having more people around the table has complicated that task, so one of the challenges for us is to give panel members, particularly the chair, the confidence to manage what is often a fraught environment where tensions are high.

Education and Skills Committee 15 March 2017 [Draft], Boyd McAdam, contrib. 36, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=10849&c=1984579

One suggestion made to the Committee by SCRA is that there may be a geographic dimension to this debate. It told the Committee that "a relatively small number of children’s hearings nationally involve a solicitor (around 4000 appointments for just under 35,000 hearings), though we recognise that there are regional variations." In its evidence, the Glasgow City Health and Care Partnership said that "Glasgow experiences more legal challenge than other hearings across Scotland. "8

Malcolm Schaffer of SCRA expanded on this point, saying—

... about half of the 4,400 appointments in hearings last year were in the west, particularly in Glasgow. Therefore, there is a particular focus there, and there are particular issues in hearings in that part of the country for whatever reason.

Education and Skills Committee 15 March 2017 [Draft], Malcolm Schaffer, contrib. 54, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=10849&c=1984597

The Scottish Legal Aid Board publishes a Code of Practice for solicitors and firms providing children’s legal assistance. This sits alongside a process whereby solicitors wishing to practice in children's hearings must be registered. A solicitor applying for registration must be able to demonstrate that s/he has the following competencies required to represent his clients at children’s hearings and/or in any associated court proceedings before the sheriff, sheriff principal and/or Court of Session:

Competence 1 – An understanding and detailed knowledge of the provisions of the Children’s Hearings (Scotland) Act 2011 and all associated Rules and Regulations.

Competence 2 – An understanding and detailed knowledge of the children’s legal assistance regime that is laid down in Part 19 of the Children’s Hearings (Scotland) Act and the associated Children’s Legal Assistance (Scotland) (Amendment) Regulations 2013.

Competence 3 – An understanding of the ethos of the children’s hearing system.

Competence 4 – Detailed knowledge or experience of representing clients at children’s hearings and related court proceedings.

Competence 5 – If representing child clients, a general understanding of child development and the principles of communicating with children.

In relation to this, Julia Donnelly of Clan Childlaw told the Committee that to get on the register, solicitors must demonstrate competence in a variety of things, but the ethos of the children’s hearings system is the first one.13 Mark Allison expanded on some of the checks in the system, stating—

The Scottish Legal Aid Board has introduced a regime of automatic checks. Every few years, it automatically reviews files through a process involving peer review, with someone coming in to ensure that people are continuing to meet the competencies. The board is at liberty to deregister a person whom it considers is not doing so. It might be the case that that process should be more structured. As I understand it, however, those steps are already being taken.

Education and Skills Committee 22 March 2017 [Draft], Mark Allison, contrib. 37, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=10863&c=1986656

One suggestion made during the Committee's deliberations on this particular aspect of the children's hearings process is whether the presence of solicitors has caused parents to be less forthcoming about problems and deficits in their parenting for fear that this information will be used against them in a hearing. On this point, Daljeet Dagon of Barnardo's Scotland said—

... we have found that if parents admit that they have deficits, that is seen as evidence that other agencies can use. That is why solicitors encourage parents not to admit to those deficits and not to accept support.

Education and Skills Committee 15 March 2017 [Draft], Daljeet Dagon, contrib. 80, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=10849&c=1984623

In response to this point, the Minister said—

... the feedback that I have had from the hearings system is that solicitors play an essential role, particularly in the most complex cases.

I will reflect on and give consideration to the point. I am not sure, however, that I could take a position that would require solicitors to let parents speak. Ultimately, that is a matter for the relationship between the solicitor and their client rather than something that a minister could direct.

Education and Skills Committee 29 March 2017 [Draft], Mark McDonald, contrib. 14, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=10879&c=1989299

More generally, the Minister spoke in favour of the ability of solicitors being present at hearings as one of the main provisions brought in by the 2011 Act to bring consistency with human rights legislation. The cited the Code of Practice as a key document he thought solicitors must adhere to.17 He also agreed to speak to the Law Society of Scotland regarding the situation where solicitors have been instructed privately.18

In addition to the above, there other issues were raised relating to the role of solicitors. Firstly, it was suggested by some that there needed to be greater awareness amongst children and young people of their right to instruct a solicitor. Julia Donnelly of Clan Childlaw told the Committee that—

More generally, on the issue of the number of children who are represented, we find that children are rarely aware that they can have legal representation. It might assist if, at an early stage, they are not just told that they can get a lawyer but are given information that helps them to find a lawyer. It has to be independent information, obviously, so it cannot be too directive, but often if you say to a child, “You can get your own lawyer,” they do not know how to go about doing that. If we gave that information, it might increase the number of children and young people who are represented.

Education and Skills Committee 15 March 2017 [Draft], Julia Donnelly, contrib. 38, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=10849&c=1984581

Secondly, as with volunteer panel members, the issue of rurality and provision of service by solicitors was raised. When questioned, Mark Allison suggested that his firm, although Glasgow based, practised the length of the country and that "It may be an issue that can be looked at, but I do not think that there is a problem with solicitors in such geographical locations being less qualified to do the work; it is simply that there are fewer of them, unfortunately."20

Finally, on the question of how the Children's Hearings system can be improved and the work underway through the Children's Hearings Improvement Partnership (CHIP), the Law Society of Scotland confirmed that it was not represented on the latter body.21

Feedback Loop

Section 181 of the 2011 Act requires the National Convener of Children’s Hearings Scotland to report to the Scottish Ministers on the implementation of Compulsory Supervision Orders by local authorities. The National Convener may ask local authorities to provide information about:

the number of compulsory supervision orders for which the authority is the implementation authority,

changes in the circumstances that led to the making of the orders,

the ways in which the overall wellbeing of children who are subject to the orders has been affected by them, and

such other information relating to the implementation of the orders as the National Convener may require.

The first such report was presented to the Scottish Parliament in March 2017.

In evidence to the Committee, the National Convener of CHS, Boyd McAdam, explained the challenges involved in implementing the ‘feedback loop’ stating that, “I do not think that the feedback loop is working as Parliament originally intended, but we are making a start on it.” He said that they had only been able to capture data on around 1% of Compulsory Supervision Orders and that “the management information just does not seem to be there.” Boyd McAdam told the Committee that “We are working with the data collectors to move towards the provision of information on all Compulsory Supervision Orders, but we have quite a way to go."1

In the foreword to the report published earlier this month, he described his ambition to “identify a meaningful data set, which provides more useful information about the wellbeing outcomes for children and young people and which can be used to drive improvement across the Children’s Hearings system.”2

In their evidence to the Committee, CELCIS and the Centre for Youth and Criminal Justice said that whilst they recognised the complexity of setting up this system, in the absence of information to the contrary, "it appears the feedback loop system remains aspirational at present". They believed that the implementation of an effective feedback loop "is likely to require significant resources."3

The comment on the possible costs of a fully functional feedback system was also highlighted by COSLA in its submission. COSLA said—

... the Feedback Loop in its current form has become an arbitrary exercise and one which we question the value of. It is not the useful communication tool which COSLA had argued for, but instead has become a one way information gathering exercise: from the CSOs, to the National Convener to Parliament. It has also become clear that the process to develop the report places unanticipated demands on local authorities but without clear benefits to the authority or – importantly – to outcomes for children and young people.4

COSLA also described a number of challenges within individual authorities in terms of the type of data they hold, the format that this is in etc., as well as challenges between local authorities when attempting to aggregate the data together to build a national picture. Critically, on costs, COSLA noted that the Financial Memorandum which supported the Bill did not identify any additional costs for local authorities to provide information for the Feedback Loop and there is no continuing mechanism to identify and address these costs.5

In their evidence to the Committee during an informal session, representatives of the Scottish Guidance Association (SGA) stressed that, in their view, there needed to increased emphasis given to monitoring the follow-up actions taken for a child's plan or a compulsory supervision order to ensure that actions are being implemented and the necessary resources available. They stressed that, increasingly, SGA members were reporting problems in accessing support services such as Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAHMS) where referral times are now long, or for supporting families where services can be lacking.

In their evidence to the Committee during an informal session, representatives of the Scottish Guidance Association (SGA) stressed that, in their view, there needed to increased emphasis given to monitoring the follow-up actions taken for a child's plan or a compulsory supervision order to ensure that actions are being implemented and the necessary resources available. They stressed that, increasingly, SGA members were reporting problems in accessing support services such as CALMS where referral times are now long, or for supporting families where services can be lacking.

In his evidence, the Minister said—

The feedback loop is in its early stages. The report that was laid by the national convener highlights that we need to accelerate efforts to ensure that recommendations are being carried out and that we receive appropriate feedback so that we can take steps where required. I have a meeting coming up with the national convener to look at how we respond to the feedback loop and at what steps we should put in place.

Another step that we want to take is for me to have an early meeting with whoever succeeds Councillor Primrose as the education spokesperson for the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities after the local government elections. There is obviously a key role for local government in ensuring that decisions that are made by children’s hearings are effectively implemented and monitored.

Education and Skills Committee 29 March 2017 [Draft], Mark McDonald, contrib. 59, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=10879&c=1989344

Co-ordination between Local Authorities

The Committee also took a small amount of evidence on the issue of how the transfer of a child or young person who was part of the Children's Hearings system could be better co-ordinated and managed if they moved both within and, especially, between local authorities.

In the evidence the Committee took from representatives of the Scottish Guidance Association, we heard that there could be issues with communication between local authorities, for example, when a young person moved accommodation, moved school and, often, when they moved between local authorities. We heard that there could often be a breakdown in communication and that teachers in particular found it more challenging to support the young person.

When questioned on this matter, the Minister said—

We need to have a discussion with local authorities on that and to ensure that the practices that are in place are as strong as they can be.

[...]

There are issues with ensuring that data protection legislation is complied with. We have just gone through a process in relation to how information is shared, which is entirely about the level below child protection and welfare concerns. We will give some careful consideration to how best we can ensure that the information is appropriately shared within the requirements of the Data Protection Act 1998.

Education and Skills Committee 29 March 2017 [Draft], Mark McDonald, contrib. 57, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=10879&c=1989342

Interaction between the Children's Hearings System and the Courts

Scotland's system of Children's Hearings is unique. The hearings system is separate from the functioning of the judicial system in the Sheriff (or High) Court. Nevertheless, there are interactions between the hearings system and Sheriff Courts. For example, if there is a dispute as to how any identified problems in a Reporter's report should be dealt with, the case will be referred to the Sheriff Court. This is what is called a Children's Referral. If the Sheriff is satisfied that any of these grounds is established s/he will remit the case to the Reporter to arrange a Hearing. Once the Hearing has reached a final decision, the child or young person or their parents may appeal to the Sheriff against the decision of a Hearing.

In its evidence to the Committee, Clan Childlaw said that the operation of children's hearings and courts in relation to adoption and permanence proceedings needs to be reviewed. In its view, far too often, contact between a child and their parent is reduced to facilitate the permanence process which gives a basis for appeal which leads to a process of multiple considerations of the issue by children's hearings, sheriffs in appeal proceedings, and sheriffs considering interim orders.1

Social Work Scotland (SWS) also commented on a number of issues. It described the interaction between the two systems as "cumbersome" saying that it can be a difficult experience for families. In its experience, establishing proof at a Sheriff Court can take as much as 4 or 5 months, which can be stressful for families and delays processes for children. On occasion, SWS believes that there can be too much time given to negotiating grounds which could easily be established with a reasonably short court hearing. This is particularly difficult, in its view, where the resulting established grounds bear little resemblance to the original and their power and weight has been lost in a bid to avoid a Hearing.2

SWS also noted the significant time delays which sometimes can occur in securing substantive Orders, which is of particular concern where no Interim Order is in place. Its view is that a more streamlined approach to decision making would be in children’s best interests and would increase capacity for the Hearing system, staff and reduce stresses on families. SWS noted the particular success of the PACE project in addressing permanence timescales for children and whether a similar application would support a review of processes more generally.2

In relation to dealing with offending issues, SWS suggests that further improvements can be made in terms of recognising the importance of retaining young people who offend within the Children’s Hearing system (in line with current policy) instead of referring them into the adult Court system would be significant to meeting children’s long term needs.2

In its evidence to the Committee, Children 1st Scotland pointed out its view that there is an inconsistent approach between the Hearings system and the court system in the treatment of witnesses. It said—

We would also highlight the considerable inconsistencies between the way in which parents and children are treated in the Hearings system and the way in which they are treated in the criminal justice system. The introduction of standard special measures to protect vulnerable victims and witnesses in criminal cases, for example of domestic abuse, do not apply in children’s Hearings. Women and children who may have been able to give evidence via video-link in the criminal court to avoid contact with a perpetrator, may find themselves sitting in the same room during the hearings process. 5

At a more practical level, SCRA told the Committee that it was working with the Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service to improve data collection with a view to identifying where any delays might arise. It noted that court processes and timescales will also be part of the Blueprint work mentioned above. Internally within SCRA, it said that its court project is looking at how they manage proofs and appeals within their own organisation so that they can be confident that they were properly resourcing, supporting and managing court work.6 This is a point shared with Children's Hearings Scotland who said that it believed "there is a need for proactive case management by the courts to avoid unnecessary delay".7

Conclusions