Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee

Inquiry into Framework Legislation and Henry VIII powers

Membership changes

The following changes to Committee membership occurred during the course of the Committee's inquiry :

On 29 May 2024, Jeremy Balfour MSP replaced Oliver Mundell MSP

On 4 September 2024, Daniel Johnson MSP replaced Foysol Choudhury MSP

On 10 October 2024, Roz McCall MSP replaced Tim Eagle MSP

On 15 January 2025, Katy Clark MSP replaced Daniel Johnson MSP

Executive summary

The Committee’s work on framework legislation and Henry VIII powers has elicited varied and thoughtful responses. They come from committees and parliaments across the world, key stakeholder organisations at the heart of Scottish policy making, leading academics and think-tanks, and eminent legal bodies.

The Committee is very grateful to everyone who contributed to the inquiry, and the breadth and strength of those striking submissions in and of itself tells a story.

While the Committee recognises that there is not a single definition for framework legislation, it understands what it is – and believes most others will know it when they see it too. It has agreed that it broadly considers framework legislation to be:

legislation that sets out the principles for a policy but does not include substantial detail on how that policy will be given practical effect. Instead, this type of legislation seeks to give broad powers to ministers or others to fill in this detail at a later stage

The Committee heard varied views about the frequency of framework legislation – there seemed however to be a general acceptance that it is not a diminishing issue. On balance, the Committee considers that across jurisdictions, it is likely the occurrence of framework legislation has increased since the 1932 Report of the Donoughmore Committee on Ministers’ Powers, and that this trend seems to be accelerating.

The Committee also agreed that its own preference, wherever possible, is for the detail of legislation to be spelled out on the face of a Bill to allow for transparency, proper democratic engagement, and so that stakeholders and parliamentarians can engage with and scrutinise solid proposals.

The Committee recognises the need in some cases for primary legislation to provide flexibility, by allowing for laws to be updated without requiring further Bills. In such cases though, the Committee argues for any delegated powers to be clear and well defined, and steps to be taken to strengthen scrutiny of both the primary legislation delegating the power and subsequent secondary legislation made under it.

The report sets out in detail the steps which the Committee supports being taken by both government and fellow parliamentarians to help achieve this.

Finally, the Committee concluded that, while it expects to see so-called Henry VIII powers (powers which allow for primary legislation to be amended by secondary legislation) appropriately limited in scope, it considers them a necessary, efficient tool when used suitably. There are nonetheless suggestions to strengthen scrutiny in relation to this category of power, as set out towards the end of this report.

Introduction

The Delegated Powers and Law Reform (“DPLR”) Committee (“the Committee”) formally agreed to hold an inquiry into framework legislation and Henry VIII powers at its meeting on Tuesday 7 May 2024.

The Committee had recently considered a number of pieces of framework legislation, including the National Care Service (Scotland) Billi and the Agriculture and Rural Communities (Scotland) Billii, and wanted to explore the perception that the number of framework Bills was increasing and the scrutiny challenges that such Bills presented. It raised these issues with the former Minister for Parliamentary Business at the Committee’s meetings of 26 September 2023iii, 19 March 2024iii, and in correspondence in April 2024v, following which the Committee decided to hold an inquiry.

The Committee wanted to look in more depth at these issues. In order to do so, it agreed to focus on questions relating to definitions of framework legislation, whether it is being used more frequently, and whether improvements could be made to scrutiny processes for either framework provisions or for subordinate legislation stemming from framework legislation. It also agreed to look at secondary legislation being used to amend primary legislation (so-called Henry VIII powers), and concerns about how such powers might be used.

The Committee considered these issues during its business planning session on Tuesday 25 June 2024, at which it heard informally from the Minister for Parliamentary Business, as well as two academics (Professor Richard Whitaker and Dr Pablo Grez Hidalgo).

The Committee’s call for views on the inquiry ran from Friday 5 September to Thursday 31 October 2024. The Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe) produced an analysis of responses.

On Friday 6 December 2024, Members of the Committee (Stuart McMillan MSP, Jeremy Balfour MSP and Roz McCall MSP) met privately with Members of the House of Lords Delegated Powers and Regulatory Reform (“DPRR”) Committee, Lord Lisvane, former Clerk to the House of Commons, and the Office of the Parliamentary Counsel (the UK Government department responsible for drafting primary legislation) during a visit to London. A note from these meetings has been published.

The Committee also met (online) with the Chair of the Parliament of New South Wales’ Regulation Committee, Natasha Maclaren-Jones on Wednesday 22 January 2025. A note from this meeting has also been published.

The formal committee oral evidence sessions took place on Tuesdays 7, 14, 21 and 28 January 2025. At these meetings, the Committee heard from: academics and the UK Government’s Office of the Parliamentary Counsel; stakeholders and legal experts; other committee conveners from the Scottish Parliament and Welsh Senedd, and the former Permanent Secretary of the UK Government Legal Department; and finally the Minister for Parliamentary Business accompanied by Scottish Government officials, including the Parliamentary Counsel’s Office (the Scottish Government body responsible for drafting primary legislation for the Scottish Government).

As evidenced by those the Committee spoke with, issues relating to framework legislation and Henry VIII powers are not unique to Scotland. While this report is focused primarily on their use by the Scottish Government and scrutiny in the Scottish Parliament, the Committee found its engagement with other legislatures and those working in other jurisdictions very helpful. The Committee hopes that this report sets out its current thinking in a way which is helpful to parliamentarians elsewhere, and is keen to remain a part of relevant discussions in other jurisdictions, including through the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association.

The Committee is grateful to all those who took the time to inform its consideration of the issues. It found the thoughtful and varied responses immensely helpful, and illustrative of the strength and depth of feeling that these issues arouse in stakeholder, legal, parliamentary and academic fields.

Minutes of all relevant Committee meetings are contained at Annexe B.

Work of the Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee and subordinate legislation processes in the Scottish Parliament

Before considering the evidence that the Committee received, it may be helpful to outline what delegated powers and subordinate legislation are, the role of the Committee in relation to the scrutiny of delegated powers in Bills, and the processes in place for the scrutiny of subordinate legislation at the Scottish Parliament, as set out in Standing Orders.

What are delegated powers and subordinate legislation

Bills often give (delegate) authority to another person or body to make subordinate legislation. This is also known as delegated or secondary legislation. Most often, the authority is delegated to the Scottish Ministers (i.e. the Scottish Government) and exercised by way of Scottish Statutory Instrument (“SSI”).

Bills will set out to whom (it is proposed) the power is delegated, the extent of that power (what it may be used to do), and the level of parliamentary scrutiny which should attach to the exercise of that power (e.g. negative or affirmative procedures, or bespoke procedures, as discussed later in the report).

Once a Bill which delegates powers is enacted, it is referred to as the parent Act in relation to any secondary legislation made under powers in it.

This allows governments (both the current government and future ones), or other bodies powers are delegated to, to fill in or change aspects of a policy or other details, without needing to introduce a new Bill (“primary legislation”) to Parliament on each occasion.

Subordinate legislation is routinely used to determine the detail of an Act’s implementation and timing, or to update some of its provisions.

In addition to “routine” use, wider delegated powers can also be used to make more significant changes, or to “fill in” significant aspects of proposals. It is these wider delegated powers which are often found in framework legislation.

Role of the Committee in relation to delegated powers in Bills

As set out in Standing Orders of the Scottish Parliament, it is for the Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee to consider and report on every proposed delegated power provision in all Bills before the Scottish Parliament.

The Committee will scrutinise the delegated powers:

during Stage 1 of a Bill and report to the relevant lead committee; and

after Stage 2 of the Bill, if there are any new or revised powers, reporting to the Parliament.

At both stages, the Committee considers, in relation to each delegated power in a bill:

whether the delegation of the power is appropriate or whether it should instead be on the face of the Bill;

whether the power has been clearly drafted and goes no further than necessary to meet the stated policy intention; and

if it is to be delegated, whether the level of parliamentary procedure (e.g. negative, affirmative or otherwise) that is proposed for future scrutiny of exercises of the power is appropriate.

The Committee’s scrutiny is informed by a Delegated Powers Memorandum (DPM) provided by the Scottish Government (or Member in charge of a Bill, if not the Scottish Government). This is required at Stage 1 under Rule 9.3.3B to accompany every Bill that contains delegated powers. The rule states:

A Bill which contains any provision conferring power to make subordinate legislation, or conferring power on the Scottish Ministers to issue any directions, guidance or code of practice, shall on introduction be accompanied by a Delegated Powers Memorandum setting out, in relation to each such provision of the Bill—

(a) the person upon whom, or the body upon which, the power is conferred and the form in which the power is to be exercised;

(b) why it is considered appropriate to delegate the power; and

(c) the Parliamentary procedure (if any) to which the exercise of the power is to be subject, and why it was considered appropriate to make it subject to that procedure (or not to make it subject to any such procedure).

After Stage 2, Standing Order 9.7.9 provides:

If the Bill has been amended at Stage 2 so as to insert or substantially alter provisions conferring powers to make subordinate legislation, or conferring powers on the Scottish Ministers to issue any directions, guidance or code of practice—

(a) the member in charge shall lodge with the Clerk, not later than whichever is the earlier of—

(i) the tenth sitting day after the day on which Stage 2 ends;

(ii) the end of the second week before the week on which Stage 3 is due to start,

a revised or supplementary Delegated Powers Memorandum,

(b) the committee mentioned in Rule 6.11 [the Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee] shall consider and report to the Parliament on those provisions.ii

To supplement this information, the Committee will regularly write to the Scottish Government (or Member in charge of a Bill) to seek additional information to allow it to properly scrutinise the powers.

The Committee may also take oral evidence from stakeholders and / or the Member in charge of a Bill (usually a government minister), when it has more significant questions about the delegated powers in a Bill. To note, the majority of this scrutiny takes place at Stage 1. At Stage 2, the lead committee will have considered any changes to existing powers or new powers prior to the DPLR Committee’s consideration.

The Committee will then report its findings, including any recommendations, to the lead committee (at Stage 1) or the Parliament (after Stage 2) which will take these into account when considering the Bill.

In reporting to the lead committee or the Parliament, the Committee can also make more general comments, for example, giving its view on the overall approach to delegated powers taken in a Bill.

The Scottish Government and lead committees regularly act on the questions and recommendations from the Committee, and makes changes to delegated powers provisions at Stage 2 of Bills.

In the course of 2023 and 2024, the Committee took oral evidence from Ministers three times, questioning them on the delegated powers contained in the National Care Service (Scotland) Billiii, the Regulation of Legal Services (Scotland) Billiii and the Land Reform (Scotland) Billiii.

Scrutiny of subordinate legislation in the Scottish Parliament

Where an Act contains a provision which delegates a power, and that provision is in force, the power can be exercised (i.e. used). This results in subordinate legislation – most frequently in the Scottish Parliament by way of an Scottish Statutory Instrument (SSI).

This Committee considers all subordinate legislation instruments that require to be laid before the Parliament, regardless of procedure applied. It provides legal and technical scrutiny, testing each instrument against criteria set out in Standing Order Rule 10.3.1. These include checking that any pre-laying requirements have been met, that the power it is made under is being used as was anticipated, and that the instrument is clear and legally workable.

In the Parliamentary year 2023-24, the Committee reported 11% of all the instruments it considered, drawing points in them to the attention of the lead committee and the Parliament due to Committee concerns about legal or technical issues.i

In the same timeframe the Scottish Government withdrew and re-laid five draft affirmative instruments. Most often, instruments were withdrawn and re-laid as a result of questions raised by the DPLR Committee.i

All affirmative and negative procedure instruments are also scrutinised by lead committees. Which lead committee scrutinises the instrument will depend on its subject matter. There is no requirement for lead committees to consider laid-only instruments, which accounted for 30 of the 193 instruments laid by the Scottish Government in Parliamentary year 2023-24.i

Lead committee scrutiny looks into the policy merits of the instrument. Lead committees can recommend that either an instrument be annulled or not approved by Parliament depending on whether it is negative or affirmative procedure.

All affirmative instruments were approved by lead committees and the Parliament in 2024. Motions to annul an instrument were tabled for a total of 12 negative instruments (including one ‘package’ of six SSIs linked to court fees). 104 negative instruments were laid in total.

Of the 12, one of these motions to annul was agreed by a lead committee. However, the Chamber did not then subsequently agree to annul the instrument.iv

There are differences in scrutiny procedures for subordinate legislation between the UK Parliament and the Scottish Parliament, and as such, some of the evidence the Committee received which related to the UK Parliament would not be directly applicable to the Scottish Parliament context.

A number of the differences are highlighted in the below table, provided by SPICe:

Differences in scrutiny procedures of secondary legislation in the UK Parliament and Scottish Parliament: negative procedure Scottish Parliament UK Parliament All SSIs subject to the negative procedure are made before they are laid. Some SIs subject to the negative procedures can be made before they are laid, whereas others must be laid in draft. Negative SSIs in the Scottish Parliament are considered by the DPLRC and a subject committee. Negative SIs do not have to be considered by a committee whose remit includes the subject matter of the SI. Motions to annul an SSI in the Scottish Parliament are known as "motion for annulment". Motions to annul an SI in the UK Parliament are known as "prayer motions". Differences in scrutiny procedures of secondary legislation in the UK Parliament and Scottish Parliament: affirmative procedure Scottish Parliament UK Parliament All SSIs subject to the affirmative procedure are laid in draft unless specified otherwise in the parent Act. Some SIs subject to the affirmative procedures can be made before they are laid, whereas others must be laid in draft. A Minister is required to attend any committee considering an affirmative SSI. A Minister is not required to attend any committee considering an affirmative SI. A Minister recommends approval at the Lead Committee and (if the Lead Committee recommends approval) the Parliamentary Bureau is responsible for moving the motion to approve the SSI. The Minister who laid the SI in the UK Parliament is responsible for moving the motion to approve the SI on the floor of the House of Commons.

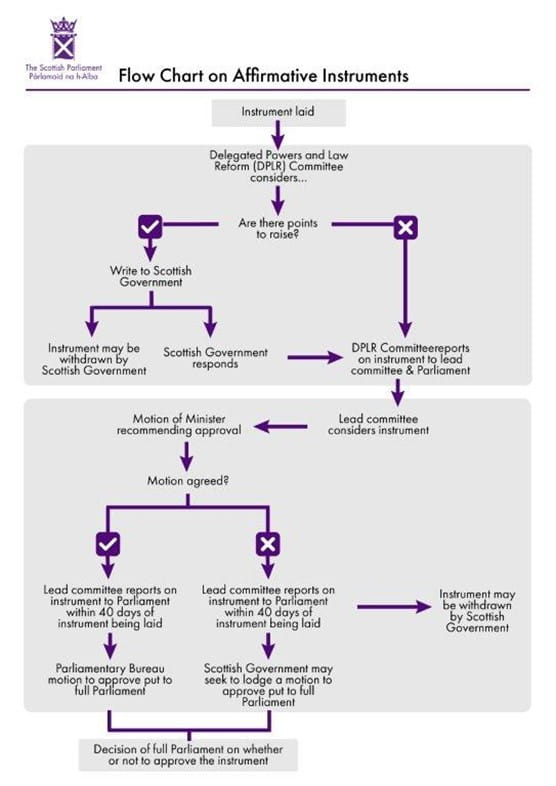

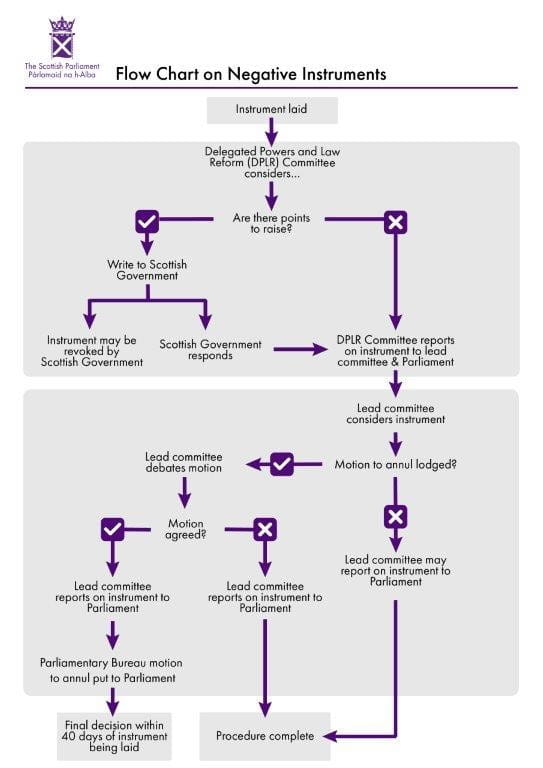

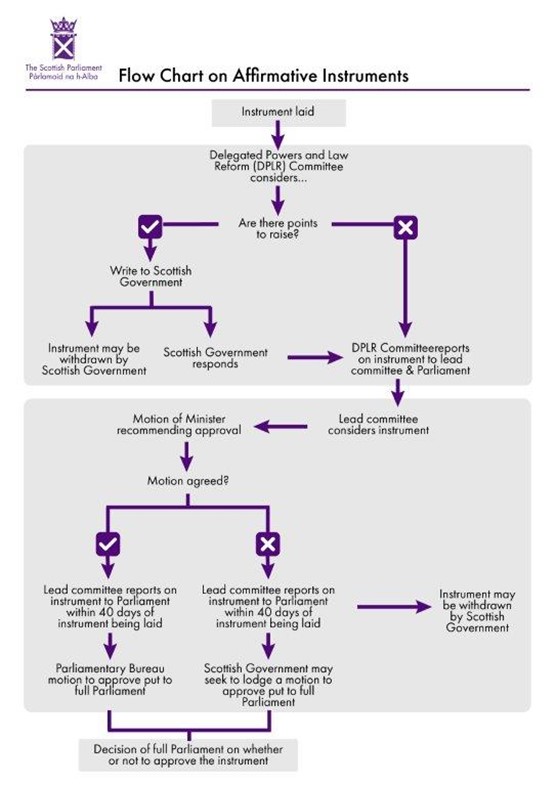

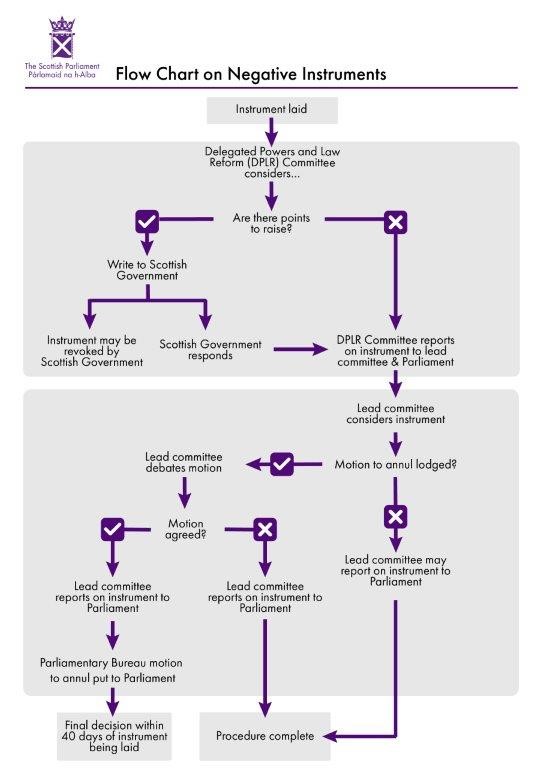

The below infographics also set out the affirmative and negative procedures. More detailed information on subordinate legislation procedures in the Scottish Parliament is set out at Annexe A.

Definition and frequency of framework legislation

Two key, interrelated, questions the Committee wanted to explore were around what is meant by framework legislation, and whether it is becoming more common. These questions were linked because, to consider whether the incidence of framework legislation being introduced into the Scottish Parliament has increased, it is crucial to have a clear understanding of what is meant by the term.

Terminology

While ‘framework’ was commonly used by witnesses and respondents to the Committee’s consultation, other terms were also used by respondents to refer to the type of legislation which sets out the principles for a policy but does not include substantial detail on how it will be given practical effect. These included skeletoni, headlineii, jellyfishii, shelliv and enablingv (although enabling can refer to any Act with delegated powers).

Dr Andrew Tickell suggested that the different terms given to framework legislation contain value judgements:

The language that we use to describe such Bills is not a question of objective description. “Skeleton” is a term of abuse and is designed to be a critical framing of powers of this kind as an inappropriate transfer of power from the legislature to the executive, whereas “framework” sounds nice and friendly and sensible and is about planning and administration. “Headline” sounds more press-orientated than anything else...ii

The term ‘framework’ is one Members of the Committee have encountered being used most commonly by Members of the Scottish Parliament to refer to legislation that sets out the principles for a policy but does not include substantial detail on how it will be given practical effect. Instead, this is left to be filled in by secondary legislation. However, the term is not one which is universally used or strictly defined.

Definition

The responses to the call for views generally suggested that framework legislation gives “broad” or “high-level” detail and principles, and then allows for detail to be added at a later point through subordinate legislation, as highlighted in responses from organisations including: the National Farmers Union for Scotland (NFU Scotland)i, the Scottish Parliament’s Net Zero, Energy and Transport (“NZET”)ii Committee and Rural Affairs and Islands (“RAI”) Committeeiii, New Zealand’s Regulations Review Committeeii and the Society of Local Authority Lawyers and Administrators in Scotland (“SOLAR”)v.

Some respondents also cited existing definitions. Professor Richard Whitakervi and Dr Ruth Fox of the Hansard Societyvii both looked to the definition used by the House of Lords Delegated Powers and Regulatory Reform (“DPRR”) Committee, which is “where the provision on the face of the bill is so insubstantial that the real operation of the Act, or sections of an Act, would be entirely by the regulations or orders made under it”viii.

The Law Society of Scotlandix noted the definition used in the Cabinet Office’s Guide to Making Legislation, which is “A bill or provision that consists primarily of powers and leaves the substance of the policy, or significant aspects of it, to delegated legislation”.

Other witnesses pointed out that Bills may contain a mix of both “standard” delegated powers and framework provision. Professor Colin Reid’s written submission pointed out “there is no exact definition and many statutes will include both framework and substantive elements”x. Kay Springham KC made a similar point “this is not a black and white situation. One might have in a piece of legislation a mixture of framework provisions, but it will not, as a whole, be framework.”xi

Need for a definition

The Committee heard differing views on whether a definition was required.

Age Scotlandii and The Royal College of Nursing in Scotland (RCN Scotland)xiii, argued for “a clear definition” in their written submissions, with both also agreeing with the general consensus of what the term means.

Professor Richard Whitaker also stated that a clear, agreed definition would be helpful for academic tracking purposesxiv.

Finlay Carson MSP, Convener of the RAI Committee and Kenneth Gibson MSP, Convener of the Finance and Public Administration (FPA) Committee, both felt that there would be value in having a clearer definition. Kenneth Gibson MSP illustrated the difficulty that not having such clarity had caused for the FPA Committee, with a Bill team and Cabinet Secretary apparently disagreeing as to whether or not a Bill it was scrutinising was framework (in relation to the Police (Ethics, Conduct and Scrutiny) (Scotland) Bill). Acknowledging that finding a single definition could prove challenging, Kenneth Gibson MSP stated that “it might be helpful to at least know the parameters”.xiv

Mike Hedges MS, Chair of the Senedd’s Legislation, Justice and Constitution (“LJC”) Committee stated that in Wales, the LJC Committee “decide that a bill is a framework bill, and we challenge the Government to tell us that it is not.” He stated that this raises awareness, and could lead to increased scrutiny of regulations made under the eventual Act.xi

Committees in the Scottish Parliament have similarly decided that Bills are framework in the past. Most recently, this Committee stated that it considered the Land Reform (Scotland) Bill to be framework in its report published on 17 January 2025, despite the Cabinet Secretary in charge disagreeing with this.xvii

In seeking a global definition, others pointed to the spectrum of different “framework” approaches, making it difficult to identify one, single, all-encompassing definition. Professor Jeff King and Dr Adam Tuckerii suggested the Committee might wish to see a “distinction between the ordinary use of delegated powers, framework schemes, and skeleton provisions.”

This position was also put forward by organisations including the Open Universityxixand the Law Society of Scotland, which pointed to an extreme category dubbed “hyper-skeletal” by the House of Lords DPRR Committeeii.

Dr Pablo Grez Hidalgo further suggested that:

we should consider the idea of skeleton legislation or skeleton provisions as a spectrum: at one extreme, there will be examples where there will be only a statement of policy intent or policy aims and no flesh whatsoever in the bill or the provision, while all the way down at the other end of the spectrum there will be instances where the legislation or provision contains more policy decisions. Since there is a spectrum of different possibilities, it would be rather difficult to have a single definition. If there is something that characterises every instance, it is the fact that key policy decisions are left for ministers to decide at a different time through delegated legislation.xiv

This position was broadly echoed by the others appearing alongside Dr Grez Hidalgo, even though some felt that a definition could be useful if it could be obtained – either for academic purposes or if different scrutiny routes ensued. Appearing on a later panel, Sir Jonathan Jones KC agreed that framework legislation should be seen as a “continuum”, rather than this being a “binary” issuexiv.

Vicky Crichton from the Scottish Legal Complaints Commission (“SLCC”) also saw the idea of a spectrum as a helpful one, and highlighted the importance of considering each Bill and each delegated power in its own context, stating:

It is ultimately for the Parliament to decide how much detail is sufficient in any given case...

…a question that the Parliament or an individual committee should ask itself when it looks at a particular piece of legislation [is]: is there sufficient detail to understand the Government’s intentions and how the powers in the legislation will operate to enable the full consideration of a bill? In some cases, “sufficient” might be quite minimal but, in others, it absolutely will not be.xi

While their written submission had supported a definition, in oral evidence, Adam Stachura from Age Scotland conceded that a definition or label might create unnecessary jargon, and as such, create a barrier for the public to engaging with the Scottish Parliament”xi.

Professor Colin Reid questioned whether a definition is necessary, acknowledging that this spectrum creates challenges in obtaining one,stating:

“Is it simply to help us to discuss these issues, or will it actually make a difference in procedural terms? If it is to make a difference in procedural terms, there is a huge challenge, because of what my colleagues have said about the spectrum and the mixture of broad provisions, narrower provisions and very precise ones that there can be within one bill.”xiv,

Dr Ruth Fox of the Hansard Societyxiv, Kay Springham KC of the Faculty of Advocates and Michael Clancy OBE of the Law Society of Scotlandxiv also all questioned what the consequence of a definition would be. It was considered a definition might allow a piece of legislation to labelled framework, but “so what?”xiv. Dr Fox also questioned who the final arbiter would be in applying any framework label to a Bill and how they would take a decisionxiv.

Lloyd Austin of Scottish Environment LINK and Jonnie Hall of NFU Scotland felt that scrutiny processes were more important, and did not see the value of defining framework legislation to create a label.xiv This point was echoed by Rosemary Agnew, the Scottish Public Services Ombudsman (“SPSO”):

Rather than spending time pinning down a definition, the more important thing is to pin down how framework bills are scrutinised and how the subsequent secondary legislation is scrutinised.xiv

The point was also made in the RAI Committee’s written submission that the definition it used in its Stage 1 report on the Agriculture and Rural Communities (Scotland) Bill, which was“primary legislation which sets out broad powers with the details of how these powers would be used and implemented to be set out at a later date through secondary legislation”, would not include the Good Food Nation (Scotland) Bill, which it also considered to be framework. As such, RAI Committee added “and other documents to be laid in Parliament” to its ‘definition’ of framework legislation for the purpose of responding to the inquiry. This, it argued, brought into scope the Good Food Nation (Scotland) Bill, and allowed it to consider documents such as the Good Food Nation plan, in addition to secondary legislationii.

In evidence to the Committee, the Minister for Parliamentary Business questioned what purpose and utility a definition would have, arguing that it “could be difficult” to come up with a simple and straightforward definition.xi The Minister also made the point that a Bill changes during the course of its parliamentary journey, with opportunities for delegated powers to be added, removed or amended. He stated “Bills change as we consider them”xi.

Committee consideration, conclusions and recommendations

The Committee notes the evidence it received that there is not a single, precise definition, or even a single agreed term for legislation that sets out the principles for a policy but does not include substantial detail on how that policy will be given practical effect.

It also notes that within a single Bill, there might be both framework and substantive elements. It is for this reason that the Committee has focused on framework legislation, rather than framework Bills.

The Committee considers that “framework” is the most commonly used term in the Scottish Parliament to describe this sort of legislation. This is as neutral a term as it can find.

There appears to be a high level of consensus as to what framework legislation is in practice, with respondents to its consultation from a range of backgrounds (academic, stakeholder, legal and parliamentary) giving similar descriptions and examples. The Committee further recognises that having a description of framework legislation will be helpful as a reference point to aid MSPs, government, officials and stakeholders in instances where a framework approach is being followed.

The Committee considers that the description it has previouslyi used for framework legislation is accurate and adequate for these purposes. The Committee’s understanding of framework legislation being that it is:

Legislation that sets out the principles for a policy but does not include substantial detail on how that policy will be given practical effect. Instead, this type of legislation seeks to give broad powers to ministers or others to fill in this detail at a later stage.

Nonetheless, the Committee recognises that, within this description, there will be spectrum of types of framework provision, grey areas, and scope for reasonable disagreement as to whether or not an individual provision or Bill fits the description it is using.

Frequency

Based on the common understanding of what framework legislation is, the Committee explored whether this type of legislation has increased.

Historic context

It was widely noted in written submissions that framework legislation is not a new phenomenon. Dr Robert Brett Taylor and Professor Adelyn M Wilsoni state that the phrase “skeleton” legislation was “coined by Lord Herschell in Institute of Patent Agents and others v Lockwood 1894 AC 347, 356”. Professor Jeff King and Dr Adam Tuckerii and Dr Pablo Grez Hidalgoiii also pointed to the 1932 Report of the Donoughmore Committee on Ministers’ Powers in their written submissions to reference the fact that this is not a new debate.

Dr Andrew Tickell, Dr Nick McKerrell and Dr Catriona Mullay stated that framework legislation is also a “long-standing concern of UK parliaments, reflected in a succession of committee reports going back to the early 1990s.”iv

Attempts to quantify the number of framework Bills

Attempts to quantify the number of framework Bills was shown to be difficult, with witnesses and government disagreeing. Professor Richard Whitaker has researched framework legislation across the UK Parliament, Senedd Cymru and the Scottish Parliament. Given that Bills are not formally or routinely labelled as framework in the Scottish Parliament, Professor Whitaker concludes “it is difficult to be precise about the proportion of bills that fall into the framework category in Scotland”, Professor Whitaker calculated that around 4 (10%) of the 40 government Bills introduced in the Scottish Parliament up to March 2024 in Session 6 have been frameworkv. Those were, the Coronavirus (Recovery and Reform) (Scotland) Bill, the National Care Service (Scotland) Bill, the Circular Economy (Scotland) Bill and the Agriculture and Rural Communities (Scotland) Bill.

In a letter to the Committee in April 2024, the Scottish Government stated that it considered “it would be reasonable to characterise” five of its Bills introduced up to that point as frameworkvi. However, these differed slightly from Professor Whitaker’s analysis. While there was agreement on three of the Bills mentioned in the paragraph above, the Scottish Government did not identify the Coronavirus (Recovery and Reform) (Scotland) Bill. It did however include the Social Security (Amendment) (Scotland) Bill and, the Housing (Scotland) Bill (for its rent control elements).

Other Bills in this session of the Scottish Parliament which were considered to be framework legislation were brought to the Committee’s attention. As discussed in the section looking at definitions above, the FPA Committee perceived disagreement within the Scottish Government as to whether the Police (Ethics, Conduct and Scrutiny) (Scotland) Bill was framework legislation.vii

The RAI Committee stated it considered the Good Food Nation (Scotland) Bill to be framework legislationv, with Scottish Environment LINK also mentioning it as a real-life experience of it engaging with framework legislation.v

Notwithstanding the difficulties calculating precise figures, the Committee heard from a number of respondents that framework legislation is becoming more common across legislatures.

Professor Whitaker’s research into the UK Parliament found an upward, though not uniform, trend in the number of “skeleton bills” since 1991, with 0.7 such bills per year on average for the period 1991 – 2015, but 2.1 per year between 2016-2023.v

The Senedd’s LJC Committee’s submission highlighted that it “has raised concerns during the Sixth Senedd about the frequent use of framework (or skeleton) legislation by the Welsh Government.” It noted that 43% of all primary legislation introduced between May 2021 and March 2024 was framework, according to research conducted on their behalf by Professor Whitaker. Three of the six Bills introduced in the Senedd by the Welsh Government in 2022-2023 were labelled by the LJC Committee as framework.xi

The House of Lords DPRR Committee felt that there had been a “considerable increase” over the last 40 years in the number of UK Bills its members thought had “skeletal” aspects. While Lord Lisvane spoke about a “steady upward trend” in the last 20 years.xii

The Hansard Society, said, “As observers of the legislative process at Westminster it has been our impression that the number of framework bills has increased in recent years”.xiii Dr Fox of the Hansard Society suggested a ratchet effect may be driving an increase in framework legislation, meaning “Governments and ministers think, “So-and-so brought forward that bill, so why can’t I do the same?””vii

From a UK drafting perspective, Jessica de Mounteney, First Parliamentary Counsel felt that events such as Brexit and COVID-19 “led to something of a culture change”, due to the speed with which legislation was enacted during that period, with the Constitution Society also suggesting that the same two events had “normalised” delegated legislationviixvi. Jessica de Mounteney also posited that any speeding up may similarly be due to changes to “the way that the world works” with 24-hour news cycles and “a constant pressure to do something”.vii

Drs Tickell, McKerrell and Mullay, from Glasgow Caledonian University stated in their written submission that “Bills containing framework powers are now a ubiquitous feature of modern governance and can be found in legislation across the whole range of the administrative state’s activities”.iv They also noted that “there is evidence of a general feeling of concern over increased use of delegated powers and framework legislation at Holyrood”.iv

A number of stakeholders involved with policy development in Scotland also perceived an increase in the use of framework legislation. These included the written submissions from Age Scotlandxx and RCN Scotlandxxi.

Kay Springham KC from the Faculty of Advocates felt that the evidence suggests that framework legislation is becoming more common:

Work has been done by others on what might be considered to be framework legislation and whether there has been more of it. My sense from reading all of that is that there has been more, and that part of the explanation is Brexit and part of it is Covid.

However, I do not know whether that is the entire reason. Perhaps there has been a shift in the attitude of Government. It has been suggested by others that a Government that gets elected wants to be seen to be doing things, and “doing things” is making legislation. If the policy in question has not been fully thought through, the easy answer is to do it as a framework bill and then work out the detail in secondary legislation.

The evidence, as far as I can see, suggests that it is becoming more common, and there is not just one but a number of reasons as to why that might be the case. xxii

In evidence to the Committee, however, the Minister for Parliamentary Business rejected the suggestion that there had been an increase in the use of framework legislation in a Scottish context, stating that “we are almost in danger of coming to the conclusion that that is the case because it is repeatedly asserted to be so. I have not seen anything to suggest that there is greater frequency.”vii

Committee consideration, conclusions and recommendations

The Committee notes the varying views it has heard based on practical experience and academic research as to whether there has been an increase in framework legislation. The Committee also notes that no witness has claimed that framework legislation is becoming less common.

The Committee considers that without a universal, undisputed definition and significant academic research, this is a question which it is not possible to answer definitively.

However, it acknowledges the perception of the majority of witnesses that the occurrence of framework legislation has increased – with some suggestions put forward as to why that may be the case.

Considering the balance of evidence, across jurisdictions, the Committee considers that it is likely the occurrence of framework legislation has increased since the 1932 Report of the Donoughmore Committee on Ministers’ Powers, and that this trend seems to be accelerating.

Why framework legislation is used

The Committee was keen to explore the reasons why framework legislation may be used. In doing so, it sought to examine any disadvantages of the approach, particularly in relation to scrutiny, as well as the positive case for the use of framework legislation.

As part of this, the Committee considered specifically what might constitute appropriate or inappropriate use of framework legislation.

The main reasons suggested to the Committee for use of framework legislation can be summarised as:

the ability to have flexibility,

an ability to co-design policy and services, and

in instances where less policy development has taken place.

Each of these reasons is examined below, as well as the cross-cutting challenges framework legislation creates, particularly in relation to legal and financial issues.

Flexibility

Witnesses and respondents suggested that the flexibility allowed by framework legislation helps to ‘future proof’ legislation and allows a statute to remain in place for a longer time without becoming outdated. It was felt that in such circumstances framework legislation could be efficient. However, almost all witnesses who recognised the benefits of flexibility that framework provision allowed suggested that flexibility and efficiency had to be balanced with robust scrutiny and sufficient detail to allow for such scrutiny. As such, most of the evidence the Committee heard argued that framework legislation should only be used in very limited circumstances.

Professor Colin Reid suggested that framework legislation “provide[s] for an uncertain and changing future”i and was “eminently sensible” in areas where there will be near-term changes in understanding or financial and physical conditions that mean updates to the law are likely to be needed.ii

The UK Government’s Office of the Parliamentary Counsel explained to the Committee how a power might come into being, to allow for updates to be made to the law. Diggory Bailey said in his experience:

We have discussions with departments about the degree to which they want flexibility. Sometimes, they come forward with a policy proposal, thinking that it will be framed as a power, but we look at it and say, “Do you really need a power? If you’re sure this is what you want, why can’t we write it out?” Equally, it might be the other way round. That involves a necessary process in which they describe the policy to us and what they want to achieve now and in the future, and we test that and think through how it will be received by Parliament. There is an iterative process to try to arrive at the best piece of legislation to give effect to ministers’ decisions.i

The Scottish Parliament’s Local Government, Housing and Planning Committee noted “there is a need for the flexibility that secondary legislation affords, but at the same time there must be a balance”ii.

The RAI Committee supported the framework approach of the Agriculture and Rural Communities (Scotland) Bill (now Act, 2024) in part because it provided “the flexibility to adapt…support via secondary legislation”.ii

NFU Scotland also supported the framework nature of this legislation. It stated that this was because of the “long-term” nature of farming and crofting, and a desire for flexibility to allow for adaptation to future circumstances. NFU Scotland suggested that the framework approach taken to the Agriculture and Rural Communities (Scotland) Act “provides scope for whatever ministers decide to do in setting objectives, in consultation with us and other stakeholders, to adjust and amend things.” i

Scottish Environment LINK pointed out that “in the environmental world, one of the reasons why we can see benefits of using framework legislation … is that science is always moving on. Some things need to be changed and updated quite quickly”.i

However, LINK also argued that there “should be limits on…flexibility and, where decisions are substantive, primary legislation should set limits to the policy”. It also argued that frameworks should still be “substantive”, and set defined policy objectives. It highlighted some reservations in relation to the Agriculture and Rural Communities (Scotland) Act 2024 on this basis.i

Adam Stachura from Age Scotland stated that the flexibility provided by the Coronavirus (Scotland) Act 2020 was sensible in the context of “fast-moving and changeable circumstances that were outwith [the Parliament’s] control”i.

Jonnie Hall of NFU Scotland also viewed framework powers as appropriate for potential emergency situations, stating “there are certain times when a Government might need to act pretty quickly…. A three or four-month period might be a bit too long if all of a sudden markets collapse or if we had a disease outbreak.”i Such emergency powers do exist in legislation allowing for response to emergency situations already, allowing for quick reaction and after-the-event scrutiny.

Members of the DPRR Committee in Westminster considered that there were some “reasonable” examples of skeleton provisions, and they could see justifiable contexts in areas of fast-moving technological change such as online safety.xi

The SPSO and SLCC both raised the issue of legislation setting up a new public body which is to be operationally independent. These organisations broadly considered that, in such circumstances, flexibility in the parent Act was helpful and appropriate to give the organisation autonomy and an ability to adapt, though the SPSO noted that the legislation “should provide sufficient clarity” on issues such as interactions with existing structures and key principles.iiii

Similarly, SOLAR stated “framework legislation is appropriate in circumstances where a Bill sets a long-term objective and flexibility is required to set up the necessary institutions and develop the monitoring procedures for meeting that long-term target.” It considered the Ethical Standards in Public Life etc. (Scotland) Act 2000 an appropriate example of flexibility being used as a reasonable justification for what it considered to be broad delegated powersxiv. That Act sits behind various codes of conduct for those in public life and the Commissioner for Ethical Standards in Public Life in Scotland.

The SLCC highlighted perceived difficulties that can arise when a parent Act lacks flexibility, citing the Legal Profession and Legal Aid (Scotland) Act 2007, which governs its functions. It explained:

we recently had a situation where the collapse of a single law firm, which was debated in the Parliament, led to some real issues. The flexibility in our processes that we would have liked to have had, which would have allowed us to look differently at how we deal with individual members of the public and consumers, really is not there. We think that we could have delivered a better service had we had more flexibility. There are things that we would like to have done that we could not do, and we do not believe that those things would have fallen outwith the purposes that the Parliament expects us to deliver. It is hard for a public body to step outside a very tightly specified piece of legislation, even in those types of circumstances.i

The point was also made that flexibility would not always provide a persuasive justification for the need for framework powers. Mike Hedges MS, Chair of the Welsh LJC Committee raised concerns about the Welsh Government taking powers to allow for flexibility “just in case they were needed”, in situations where it wasn’t clear the powers would be necessaryi. He cited an example in the Environment (Air Quality and Soundscapes) (Wales) Bill.ii

The Committee has also recently highlighted powers to lead committees in relation both the Land Reform (Scotland) Billxviii and the Housing (Scotland) Billxixand invited them to consider the necessity of the powers. In relation to a delegated power at Section 19(2) of the Housing (Scotland) Bill, the Committee stated it “does not usually consider it appropriate to delegate a power where it is not clear and foreseeable that such a power will be used. The Committee asks the lead committee to consider whether there are any policy reasons that mean it believes this power is necessary, and if not, the Committee recommends that the power is not delegated.”

Further, the framework approach taken in relation to Agriculture and Rural Communities legislation was not universally supported. In response to the call for views, William Maclaren Moses suggested that by delegating these powers in the name of flexibility the Scottish Parliament was being “sidestepped”xx.

Lloyd Austin of Scottish Environment LINK made the point that framework legislation previously passed may “have a provision for an option to act quickly in certain circumstances”i, meaning new framework legislation may not be needed to respond to emergencies, given some powers already exist. DPPR Members also pointed out that parliaments can move fast and legislate quickly if there is a pressing need. DPRR Members spoke about the ability of parliaments to be recalled, and adapt to challenging situations, as evidenced by the ability to sit virtually in response to the COVID-19 pandemicxxii.

It was also pointed out that achieving flexibility is not necessarily a binary choice between framework and non-framework provisions. Professor King and Dr Tucker pointed to the “ordinary use” of delegated powers “where there is a need for flexibility, or experimentation”.xxiii Scottish Environment LINK also highlighted what it described as a “halfway house” with the primary legislation incorporating more detail and structure, but significant policy nonetheless being set out in secondary legislation. It considered the UK Environment Act 2021 appropriate framework legislation as it contained a “broad target setting power, a duty to exercise this by a specific date in certain areas, a requirement to seek independent advice and a cycle of scrutiny and reporting”.ii

Drs Tickell, McKerrell and Mullay from Glasgow Caledonian University neatly summed up the tension between “the potential flexibility and efficiency of rule-making by secondary legislation, and competing demands for transparency, democratic accountability, and enhanced scrutiny”. They stated that “balance between flexibility and efficiency on one hand, and robust scrutiny on the other, will always be a matter of judgement, with the full circumstances of each use of delegated powers important to ensure that they are appropriate”.ii

In evidence to the Committee, the Minister for Parliamentary Business indicated that the Scottish Government did not “routinely” set out to introduce framework Bills. He told the Committee:

Bills, and the nature, form and function of the delegated powers that are in them, are considered on a case-by-case basis. Ultimately, the approach that is taken to delegated powers is driven by what makes sense in the specific context of each bill.i

Co-design

A further reason put forward to justify the use of framework legislation was the ability to co-design policy and services once the legislation had been passed.

The Health, Social Care and Sport Committee stated that it had been told that the Scottish Government took a framework approach to its National Care Service (Scotland) Bill as it was its intention to “develop the policy iteratively and collaboratively with key stakeholders through a process of co-design”.

Likewise, the NZET Committee stated that “In the context of the Circular Economy (Scotland) Bill, we heard that this would create further opportunities for consultation or "co-design".” While noting its preference for scrutiny if consultation or co-design is undertaken before the Bill’s introduction “so that meaningful policy provision was on the face of the Bill”, NZET Committee recognised that:

there may be circumstances where there are valid reasons that this policy development cannot be done with stakeholders ahead of the Bill’s introduction, in which case this may make framework provisions in a Bill appropriate.i

From a stakeholder perspective, RCN Scotland accepted “one advantage of framework legislation could be that detail relating to implementing policy decisions can be designed with a wider range of stakeholders outwith the parliamentary process.”i Though it also held some concerns about this in practice.

NFU Scotland also spoke about co-design in its submission to the Committee in relation to the Agriculture and Rural Communities (Scotland) Bill. It stated this occurred with many stakeholders from a range of backgrounds both before the Bill’s publication, during the process of it going through the Scottish Parliament, and would continue now the Bill has passed as the Rural Support Plan is developed.iii In oral evidence, Jonnie Hall of NFU Scotland said “We have seen very much a continuation of engagement with stakeholders, which brings us to co-design. It is to our credit that that is how we do things in Scotland.iv.

However, challenges created by framework legislation allowing for co-design to take place alongside and after the parliamentary process were recognised by respondents and witnesses.

Speaking about the National Care Service (Scotland) Bill, the Health, Social Care and Sport (HSCS) Committee stated that many witnesses expressed concern about the Government’s co-design plans as the “lack of detail in the Bill made it difficult to determine whether it would improve the quality and consistency of social work and social care services in Scotland.”i

RCN Scotland stated that its own experience of being involved in co-design through the National Care Service (Scotland) Bill had “not been positive”, despite it seeing the positive case for co-design. It echoed the suggestion made by the HSCS Committee, stating that it saw the most significant disadvantage of the approach as being on the “the ability of stakeholders (including Parliament) to meaningfully scrutinise proposals”.i

The FPA Committee, which scrutinises Financial Memorandums (FMs) accompanying Bills in the Scottish Parliament, suggested that co-design processes to finalise exact policy during and beyond the passage of the relevant primary legislation presented significant challenges for effective financial scrutinyi. In oral evidence, the Committee’s Convener Kenneth Gibson MSP reiterated this point “although we are not particularly keen on them, if they [framework Bills] are to be used, all the co-design work and stakeholder engagement should be done prior to the bills coming to the committee, so that we can fully analyse the costs.”iv The FPA Convener was unequivocal, stating that, although the Committee supports co-design there is “absolutely no reason at all why co-design and stakeholder involvement cannot happen before a bill reaches stage 1.”iv

Similarly, the Equality and Human Rights Commission, while agreeing with the concept of co-design, argued that it “should be done in advance of a Bill being published” and that “ongoing or future co-design should not be used as justification for a framework Bill and should instead inform a more detailed Bill during its development phase.”x

Rosemary Agnew, the SPSO also felt that co-design is a term that could be unclear, drawing a distinction between “co-design of the policy that informs the framework and the legislation from the co-design of how that policy will be delivered”,iv making the point that when co-design happens has an impact on the proposals put to Parliament.

When asked whether she was supportive of co-design taking place after a Bill was passed, Dr Ruth Fox of the Hansard Society responded:

There might be very specific reasons for justifying it in that way, but I would, as a general principle, say no. You should do the consultation about the direction of policy, the options, the pros and cons and why the Government has chosen a particular course over another one first. There might then be a case for consulting on the specific operational detail of the regulations with the affected stakeholders at a later date when the regulations come forward.iv

In evidence to the Committee, the Minister for Parliamentary Business set out that there would often be co-design before and after the passage of a Bill. He said:

there will be co-design through the process of engagement with relevant parties in advance of introducing legislation. That will happen, but sometimes it will be appropriate to set out in the bill the high-level principles under which the law should function. Thereafter, as part of the various functions that are determined through secondary legislation, that should also be done by co-design.iv

Less policy development having taken place

One final reason suggested by witnesses for the introduction of framework legislation was that less policy development had taken place before the Bill was introduced, meaning that Ministers were instead taking a framework approach and allowing the details to be worked out and added through secondary legislation.

DPRR Committee Members suggested that a pressure for legislative ‘slots’ in Parliament meant it was attractive to civil servants and governments to give themselves a power to “fill in” policy details not yet concluded at a later point, and to make quicker changes in the future (without needing further primary legislation).i

Lord Lisvane pointed to the pressure on governments to be seen to legislate – particularly in the immediate aftermath of an election with a manifesto to implementii, a point echoed by the UK First Parliamentary Counsel, who shared their perception that “there is a constant pressure [on Ministers] to do something, and that that “something” tends to be legislation.”iii

The Hansard Society highlighted “unrealistic, self-imposed 100-day deadlines” in the context of a post-election period leading to framework legislation. It further stated that this “is not an acceptable reason for Ministers to take powers for themselves (and their successors) to legislate at a later date – especially through a process that allows for less parliamentary scrutiny than primary legislation.”iv

Kay Springham KC from the Faculty of Advocates also noted that the argument in relation to parliamentary time is a possible driver behind any increase in framework legislation.iii

Adam Stachura of Age Scotland warned against this approach, telling the Committee:

I think that there is a place for framework legislation, but it is being used too freely when there is a lack of detail to begin with, and it is a case of, “We will fill in the blanks at the end.” That is not good for public scrutiny and even, quite frankly, for committee scrutiny.iii

Challenges of a framework approach – including legal and financial issues

A number of respondents to the Committee’s call for views and witnesses expanded on what they saw as the obstacles to effective scrutiny presented by framework legislation, including scrutiny of the legal and financial implications of such legislation.

SOLAR argued that because MSPs are asked to pass legislation without knowing exactly how the powers conferred may be exercised “the use of framework legislation dilutes the level of scrutiny and interrogation that good legislative practice requires” and impedes the Parliament’s opportunity to effectively engage with stakeholders.i

The Faculty of Advocatesi and Senators of the College of Justice (Judges sitting in the Supreme Courts) made the point that, when considering framework legislation, the entirety of the law is not scrutinised at one point, meaning that legislators cannot consider the complete manner in which it will operate. The Senators argued that:

at the time of scrutiny, there will inevitably be an incomplete picture of what legal rights and duties may arise and what procedures must be followed and issues may be missed.i

The Faculty of Advocates summed up this concern in relation to framework legislation stating:

when framework legislation is used: the primary legislation does not give the full picture; the secondary legislation is often subject to lighter touch scrutiny and also does not give the full picture; and the courts cannot properly carry out their function of determining whether the legislation is lawful.i

The Faculty of Advocates went on to highlight a case where not having the full picture of legislation had caused a practical challenge. It pointed to the judicial review undertaken of the Tied Pubs (Scotland) Act 2021 (Greene King Ltd v Lord Advocate 2023 SC 311). It stated that the primary legislation was “lacking in clarity” because its effect was to be implemented largely through secondary legislation which was not yet in force at the point of the judicial review. Had the litigators waited for the secondary legislation then the challenge to the primary legislation “would almost certainly have been time barred”v.

Respondents who have practical experience of considering framework legislation highlighted difficulties in assessing the financial impact and costs of legislation. As mentioned in the section in relation to co-design, the FPA Committee and its Convener stated that framework legislation presents a significant challenge for effective financial scrutiny. This has been a concern of the FPA Committee this session.i

The FPA Committee outlined the significant work it is has undertaken to raise its concerns about the impact of framework legislation on its financial scrutiny work. It has corresponded with the Presiding Officer, the Minister for Parliamentary Business and the Scottish Government’s Permanent Secretary in relation to this issue, and has secured commitments from the Scottish Government to update guidance and put in place enhanced training for Bill teams to improve the quality of financial memoranda.v

The FPA Committee cited as an example the original Financial Memorandum for the National Care Service (Scotland) Bill which, it said, did not have enough detail to allow the Committee to assess or scrutinise the financial implications of the Billv. This concern was shared by Adam Stachura of Age Scotland, who was of the view that there is a lack of understanding of the financial implications of the legislation.ix

The Scottish Parliament’s NZET Committee also highlighted the difficulties in assessing the financial implications of framework legislation. It made the point that the FPA Committee does not have a role in scrutinising the impact of secondary legislation, meaning the financial impact of regulations may not be fully understood.i

The RAI Committee described the financial memoranda for both the Agriculture and Rural Communities and the Good Food Nation Acts as “wholly inadequate”i suggesting scrutiny concerns of the FPA Committee can also be shared by lead committees, who consider in detail the overall policy and general principles of a Bill at Stage 1.

SOLAR stated that “the lack of detail [in framework legislation] makes it extremely difficult for local authorities and the wider public sector to assess the impacts of the legislation and the costs of implementing the policy”. The impact of this, SOLAR stated, is to create challenges for local authorities to forward plan for key services likely affected by legislation, and implement appropriate budgets.i

Lloyd Austin of Scottish Environment LINK also spoke about the lack of detail in financial memoranda for framework legislation presenting a scrutiny challenge for stakeholders. Describing the organisation’s experience of engaging with the Circular Economy (Scotland) Bill Lloyd Austin said:

It was such a framework that the financial memorandum did not indicate what the financial consequences would be for anyone. Our view might be different from that of other people about what should be done under the circular economy strategy and what the financial consequences for Government and businesses might be, but the point is that such a minimal framework meant that that debate could not happen. That debate will happen when the strategy is produced. The question is, what are the scrutiny provisions for that, and how will it be debated?ix

Professor Colin Reid acknowledged this challenge. He suggested that it might be possible to request additional financial memoranda to accompany subordinate legislation, in an attempt to address the “gap” in scrutiny.

It follows from the nature of framework legislation (and is a key part of its value) that at the time of enactment there is no guarantee of whether and how the powers granted will be used. Therefore at the Bill stage, it is inevitable that the Policy and Financial Memoranda can say very little – the whole point of the framework is that different Governments may use it for different purposes. The scrutiny gap arises because there is no equivalent requirement for policy and financial information at the time delegated legislation is presented to Parliament (or the policy leading to such legislation has sufficiently crystallised). This gap needs to be filled somehow and … It would be possible to require such Memoranda for some or all delegated legislation, but that increases the burden on government.i

On the issue of financial implications of framework legislation, the Minister for Parliamentary Business told the Committee:

I have certainly raised and emphasised the point to my colleagues that the quality of the financial memoranda should always be sufficient for the purpose of the finance committee’s consideration of any legislation or, indeed, subject matter. That should be a thorough and proper exercise.

It goes back to the point about on-going deliberation and consideration of legislation, whether it be in primary or secondary form. My expectation is that, if a committee of the Parliament is looking for more information, colleagues should provide it.

…

The finance committee has raised a concern and has written to me about it. I have heard that concern and I have acted on it. I have communicated to all ministerial colleagues, and to all senior civil servants who are involved in the consideration of any financial memoranda, that they should ensure that they go through the rigorous process that the Parliament rightly expects. We could also update the Government’s handbook on the bill to that effect.

If the Parliament considers that we can do more, it need only ask. If it asks for something that we can do, I will be happy to implement it. If it asks for something that we cannot do, I will be happy to set out why that is the case.ix

Committee consideration, conclusions and recommendations

The Committee notes the evidence it received on why framework legislation may be used, the reasons why it may be useful in certain circumstances, and the disadvantages of a framework approach. The majority of the evidence received highlighted the challenges framework legislation creates.

The Committee considers that legislation should, other than in very limited circumstances, set out a high degree of detail on the face of the Bill. This facilitates transparency and proper democratic engagement, by allowing both stakeholders and parliamentarians to engage with solid proposals.

In appropriate and very limited circumstances, the Committee considers that there may be a case for framework powers, primarily in order to provide flexibility.

Where a framework approach is being taken, it is essential that a full justification at the Bill’s introduction is given as to why the framework provision is appropriate in the circumstances.

It is not possible to give a definitive view as to what constitutes “appropriate circumstances” for framework legislation. Each use of delegated powers will need to be considered on its own merits and in the context of that particular power.

The circumstances where a framework approach may be appropriate are more likely to arise in areas which need to be updated frequently, in ways which cannot reasonably be foreseen.

Where a framework approach is taken, the Committee highlights the concerns it heard about the lack of detail on estimated costs provided in accompanying Financial Memoranda. The Committee confirms that all Financial Memoranda should include an estimate of any costs arising from delegated powers provisions, based on how it is expected to, or might, be used by the administration. The Committee also calls on the Scottish Government to ensure it keeps committees updated throughout the legislative process on the estimated costs arising from a Bill and discuss with the committee the most appropriate format for presenting any updated figures.

The Committee considers powers allowing flexibility “just in case” are unlikely meet the test for the necessity of the power, and as such be considered inappropriate.

The Committee considers that consultation and “co-design” on a Bill’s provisions should take place prior to its introduction to enable sufficient policy detail to be provided on the face of the Bill.

The Committee considers that, as a general rule, a lack of policy development is not an appropriate justification for introducing framework legislation.

Improving scrutiny of framework legislation

The Committee recognises that, where framework provision is included in a Bill, it is crucial that parliamentarians and stakeholders have the means to properly scrutinise it and consider its impact. To that end, it therefore explored what action could be taken to improve such scrutiny.

The Committee heard various suggestions to improve parliamentary scrutiny of framework provision in a Bill including:

The Parliament (or DPLR Committee) articulating its expectations in guidance for government and drafters,

Enhanced and improved information from the Scottish Government on the introduction of framework legislation, including:

drafts of subordinate legislation,

enhanced accompanying documents and “skeleton declarations”,

Post legislative scrutiny, and

A “scrutiny reserve”.

The merits of these suggestions are discussed below.

The Parliament (or DPLR Committee) articulating its expectations in guidance for government and drafters

The DPRR Committee in the UK Parliament House of Lords has produced its own Guidance for Departments on the role and requirements of the Committee.i This sets out, amongst other information, the DPRR Committee’s view on what a framework Bill is, and the very limited circumstances it considers framework legislation appropriate. It also sets out principles the DPRR Committee expects should be adhered to in relation to the delegation of powers, and how these should be explained in Delegated Powers Memoranda, including the government making “skeleton legislation declarations”. These declarations are explained in detail later in the report.

The DPRR Committee’s guidance document was mentioned by a number of respondents to the DPLR Committee’s call for views, including the Hansard Societyii, Professor Richard Whitaker,ii and Dr Robert Brett Taylor and Professor Adelyn M Wilsoniv.

The UK Government’s First Parliamentary Counsel, Jessica de Mounteney, explained that when drafting UK Bills, the Parliamentary Counsel’s Office is “acutely aware of the likelihood of criticism from the delegated powers committee, and that it informs a lot of our discussions with the department”.v

It was suggested that the Committee may wish to produce similar guidance. Dr Pablo Grez Hidalgo argued that this might be a way of enhancing the Committee’s influence in the earlier stages of Bill preparation, by ensuring its expectations of the Scottish Government and its drafters are clear.iiv.

During oral evidence, the Committee explored concepts related to the general point of guidance, including around ‘guardrails’, ‘concordats’ between Parliament and Government and ‘principles’ around framework legislation.

There was support for the idea of guidance or principles establishing when framework legislation would be acceptable by a number of witnesses. These included Dr Ruth Fox from the Hansard Societyv, Dr Pablo Grez Hidaglov, Professor Whitakerv, and Sir Jonathan Jones KCv.

There was general agreement from the stakeholder panel the Committee heard from on 14 January 2025v that guidance could be a helpful tool, and NFU Scotland in their written submission indicated three criteria which could, in its view, be appropriate for governing whether framework legislation is appropriate. These are:

There is a need to deliver flexibility and adaptivity to mitigate possible future challenges.

Extensive work is undertaken with relevant stakeholders before and during the parliamentary process.

A clear indication of the overall required outcomes is set out by the Scottish Government.ii

However, other witnesses and respondents were more circumspect. Professor Reid, speaking about guidance on what secondary legislation might be appropriate for, warned that clear-sounding principles – like not creating a criminal offence through subordinate legislation – could lead to outcomes in real life which may not have been intended to be captured by the original principle. Professor Reid stated:

You need to appreciate that there are problems, even with something that seems as simple as creating a criminal offence. What does that actually mean? Slightly changing the boundaries of a criminal offence would make things criminal that were not criminal before. …there may be a criminal offence, but you would want it to be easy to change and update the legislation at all times for technical reasons. However, narrow changes in the boundary would bring people into criminal law who were previously outside it. There may be difficulties even with something that sounds as clear and neat as [not] creating a criminal offence.v

Dr Fox highlighted the work the Hansard Society had done as part of its delegated legislation review. One idea to come from that was a ‘concordat on legislative delegation’ between the UK Parliament and Government to set out a joint understanding of what should, and what should not, be provided for in delegated legislation. Dr Fox indicated, however, that work on the delegated legislation review highlighted how difficult finding consensus could be – both in terms of what is appropriate delegation and about the structure of any agreementv.

Dr Andrew Tickell felt that even if guidance existed “the Government will do what it feels politically able to get away with”.v

In evidence to the Committee, the Minister for Parliamentary Business stated that:

If there was some determination that there should be guidance, we would need to consider how we might interact with that….

If the question is whether guidance should be created to say when the Government can and cannot introduce a bill in a certain way, I would probably respectfully push back on that, because ultimately it should be for Parliament to determine the nature of a bill as we move forward.

Bills change as we consider them. I have just taken the Scottish Elections (Representation and Reform) Bill through Parliament…That bill changed, and secondary legislation-making powers were added to it as we moved through the process.

The creation and passing of a bill is an iterative process. Trying to limit the manner in which a bill can be drafted before it is even introduced would not be as helpful to Parliament as people might think.v

Enhanced and improved information from the Scottish Government on the introduction of framework legislation

As set out in the introduction, any Bill conferring power to make subordinate legislation, or conferring power on the Scottish Ministers to issue any directions, guidance or code of practice, must be accompanied by a Delegated Powers Memorandum when introduced. This must set out, in relation to each such provision of the Bill—

(a) the person upon whom, or the body upon which, the power is conferred and the form in which the power is to be exercised;

(b) why it is considered appropriate to delegate the power; and

(c) the Parliamentary procedure (if any) to which the exercise of the power is to be subject, and why it was considered appropriate to make it subject to that procedure (or not to make it subject to any such procedure).

This document assists the Committee to initially assess each delegated power in a Bill, and consider whether further information is required before reporting to lead committees.

In addition to the Delegated Powers Memorandum, Bills must also be accompanied by a Policy Memorandum, a Financial Memorandum and Explanatory Notes.

Drafts of subordinate legislation

A number of witnesses suggested that the Scottish Government should provide drafts of the subordinate legislation at the same time as Parliament is scrutinising the parent Bill, to give a clear sense to both stakeholders and parliamentarians as to how the Government intends to use a framework power.

The Hansard Society suggested that in exceptional, justified scenarios where framework legislation is used, “draft regulations, or other indications of how the powers may be used, are provided along with the bill” as a way to assess the appropriateness of the delegation of powers.i

Professor Jeff King and Dr Adam Tuckeri, as well as the Law Society of Scotlandi were supportive of this approach, as was the Scottish Crofting Federation, which stated:

Framework legislation should only be enacted after draft proposals for secondary legislation have been published. Stakeholders must be provided with satisfactory evidence as to how the framework, as well as the proposed draft secondary legislation will address the stated objectives.i

Age Scotland also argued for “general information and principles of what would be expected in secondary legislation.”i

Professor Reid however was sceptical about this solution, noting that “if you are at the stage where you have the SSIs already drafted, you do not need the framework bill—you could be producing a more solid bill.”vi

Enhanced accompanying documents for Bills and “Skeleton declarations”

A number of respondents and witnesses stressed the importance of information which accompanies framework legislation. It was suggested that ensuring this is detailed and of a high standard would aid scrutiny.

Dr Robert Brett Taylor and Professor Adelyn M Wilson suggested that the Scottish Parliament should require “a more robust and detailed memorandum … This might usefully provide enhanced detail on the context and impact of the powers being granted.”i Professor Whitaker made a similar point stating that Bills that delegate considerable numbers of powers to ministers may be acceptable “if enough detail is provided about the limits to and the policies to be implemented by those powers”i.

A strong delegated powers memorandum “that fully justifies the need for the delegated powers and provides examples of how powers might be used” was also suggested by the NZET Committee in relation to framework legislationi.

Dr Pablo Grez Hidalgo also pointed to the DPRR Committee’s practice of asking for the Government to make an explicit declaration in the delegated powers memorandum which accompanies a skeleton Bill. This is set out in its Guidance to departments: