Criminal Justice Committee

Judged on progress: The need for urgent delivery on Scottish justice sector reforms

INTRODUCTION

Between September and November 2021, the Criminal Justice Committee held a series of roundtable meetings, looking at a number of key issues in the justice sector.

The purpose of the roundtables was to hear from external organisations and individuals and to give Members an up-to-date picture of developments in the justice sector. It was envisaged that each roundtable would also provide an idea of the short and longer-term measures that might be needed to tackle each of the issues. These would then be developed into an Action Plan.

This report contains separate chapters on the following issues:

The impact of COVID-19 on the justice sector;

Prisons and prison policy;

Misuse of drugs and the criminal justice system;

Victims’ rights and victim support;

Violence against women and girls;

Reducing youth offending, offering community justice solutions and alternatives to custody, and

Legal aid.

The summaries in each chapter are not intended to provide a comprehensive analysis as we would produce if we had conducted full inquiries into each issue.

They summarise the issues raised during a single evidence session on each subject area. Doing justice to the detail of any single issue would require a much longer inquiry. Nevertheless, the roundtables provided the Committee with a valuable overview of each subject and allowed us to identify a number of short-term and longer-term actions that are needed.

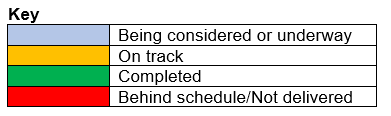

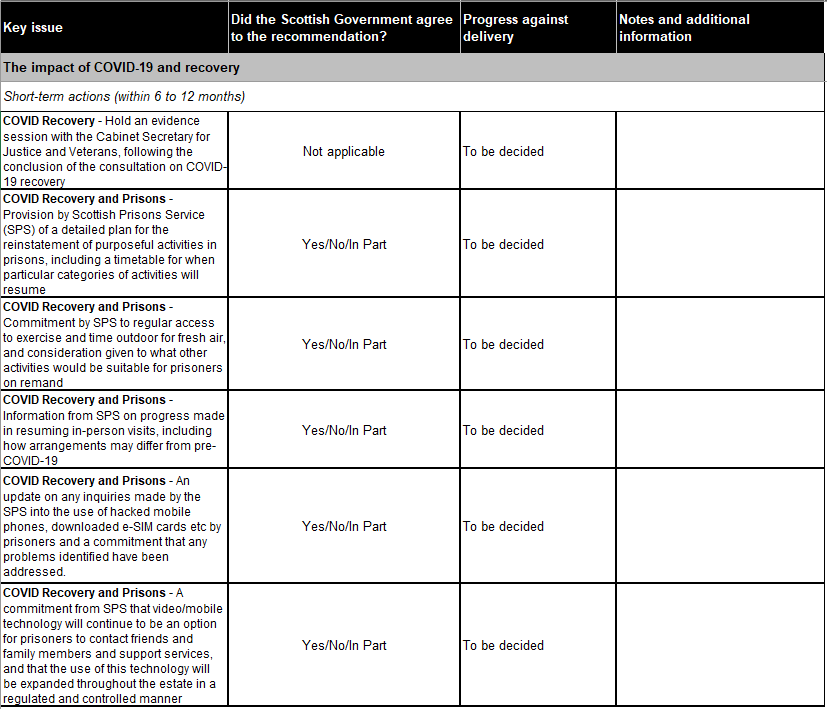

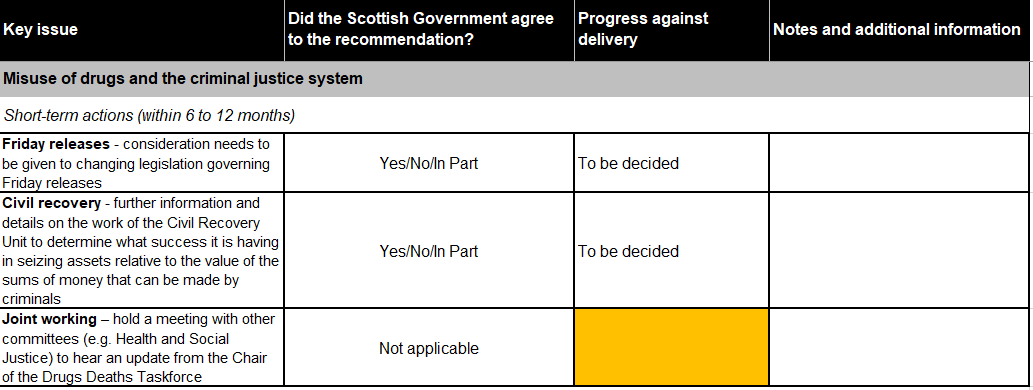

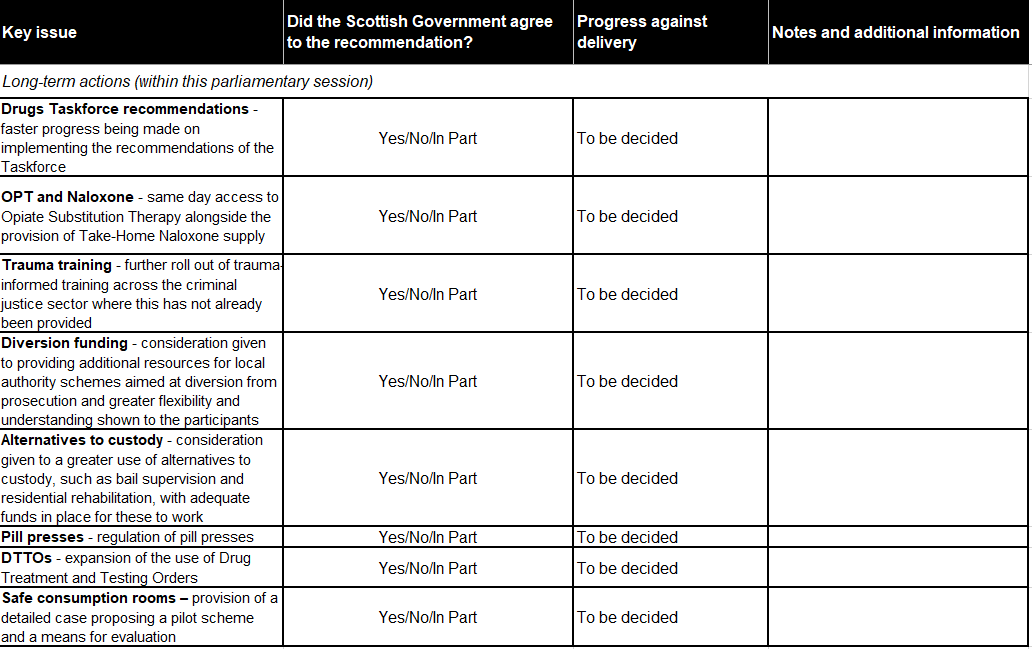

We have collated these actions into an Action Plan (Annex A). This Action Plan will be used to monitor the progress of the delivery of improvements by the Scottish Government and other bodies. Our intention is to update this Plan at regular intervals in this parliamentary session.

THE IMPACT OF COVID-19 ON THE JUSTICE SECTOR

Introduction

On 8 September 2021, the Criminal Justice Committee held a roundtable meeting about the impact of COVID-19 on the justice sector. The Committee took oral i and written evidenceii from a number of stakeholders.iii

COVID-19 has clearly affected all aspects of the justice sector and has had, and continues to have, a major impact.

As well as being the subject of this roundtable meeting, the impact of the pandemic was also raised as an issue at several of our other roundtable meetings.

It is clear to us that COVID-19 recovery will be a major ongoing priority during this parliamentary session.

Court backlogs and ‘digital justice’ – impact of COVID-19

Prior to the pandemic, the court system in Scotland already had a backlog of trials. The impact of COVID-19 led to that backlog in the court system increasing markedly. According to the Scottish Government, the current backlog of solemn trials (for the most serious crimes) is not expected to be cleared until 2025. The summary trial backlog is not expected to be cleared until 2024.

Before the pandemic, there were approximately 13,400 sheriff court trials outstanding. The number at the moment is over 32,400 trials. In the justice of the peace courts, there were just over 3,200 trials outstanding, and the number is now sitting at approximately 7,890. In the sheriff and jury courts, there were about 1,330 trials outstanding pre-pandemic and there are now currently in excess of 3,500 trials for the more serious offences.

Conclusion: As a Committee, we recognise that each and every one of those delayed trials means justice for the victims has been put on hold and the rights of the accused to be heard in court have been curtailed. We are particularly concerned about the disproportionate impact of delays on victims of gender-based violence who are predominantly women and girls. Cases of serious sexual violence make up 80 to 85 per cent of cases that proceed to trial in the high court.

In order to help address this backlog, the Scottish Parliament agreed temporary legislative powers to permit a more digitally-based justice system. These include powers allowing virtual/remote attendance in courts and tribunals, including in criminal court cases. In addition, temporary legislative measures extending various statutory time limits for progressing criminal court cases were agreed, including ones extending the time that an accused can be held on remand.

The Scottish Government is currently consulting on a proposal for a longer extension of some of these temporary provisions and also whether some should be made permanent at this stage. Primary legislation on this is expected in the new year and the Committee hopes to take a role in its scrutiny.

The Scottish Courts and Tribunal Service (SCTS) is also significantly increasing the number of jury trials in order to address the backlog.

At our roundtable meeting, the Committee heard about the impact of the backlog in the court system on victims of crime. Kate Wallace of Victim Support Scotland told us that“the delays in trials are having a massive impact on the mental health of victims and witnesses”.

The number of remand prisoners in Scotland’s already overcrowded prisons was also discussed. The number of prisoners held on remand has increased to a total of over 1,700 in 2020-21. Delays to trials means it has been more difficult to keep periods of remand within normal statutory time limits.

Tony Lenehan of the Faculty of Advocates was broadly supportive of some of the proposals taken by the SCTS to address the backlog. However, he expressed concern that ‘digital justice’ can impact on the quality of communication in court. The setting of a virtual trial may also lack the gravity of a formal court room. He commented—

“…in the High Court, things have to be about justice first and foremost. When it comes to matters of convenience to do with shepherding people to court, keeping people from travelling on the roads and all that sort of thing, I understand that there are benefits there, but they do not measure up to the benefits of having the most accurate and the fairest justice. Virtual contact reduces that.”i

A similar view was echoed by Ken Dalling of the Law Society of Scotland. Mr Dalling also expressed concern about changes being “Trojan-horsed” in.

However, Mr Dalling and Mr Lenehan agreed that it would be appropriate to retain some of the temporary changes, particularly those detailing with procedural or administrative matters. These included using electronic signatures and the remote balloting of juries. Both the Law Society of Scotland and the Faculty of Advocates had reservations about some of the other proposals for a more digital justice system.

Eric McQueen of the SCTS raised the idea of a ‘hybrid option’ where certain participants in courts could take part remotely but the accused appeared in person. He said that “it would be unfair to categorise everything as being a step backwards". ii

Prisons and COVID-19

The impact of COVID-19 on prisons and on purposeful activity in prisons in particular was also discussed at the roundtable meeting.

Purposeful activity is generally understood to refer a range of constructive activities within prisons such as work, education and vocational training, counselling and other rehabilitative programmes.

Purposeful activities in prisons were suspended in March 2020. Teresa Medhurst, Interim Chief Executive of the Scottish Prison Service, told us—

“We had to put down the majority of our activity, including our learning service from Fife College and our prisoner programmes. It was only when we started to step out from lockdown with the rest of the country that we were able to look at the arrangements that we could put in place in order to reinstate some of those services. I am sure you will understand that that has limitations because of the restrictions.”i

Ms Medhurst set out some of the mitigations being put in place to allow the return of purposeful activities.

There was also discussion about the wider impact of COVID-19 on prisons at the roundtable on 15 September 2021. For example, we discussed how prisoners had kept in touch with their friends and families when physical visits were not permitted due to COVID-19 restrictions.

Ms Medhurst was asked about reports that mobile phones provided to prisoners had been hacked and used to purchase drugs. She indicated that there were “security measures” in place to identify phones that have been tampered with.

We also discussed whether video contact from families could be continued after the pandemic. Ms Medhurst told us “we are working on a digital strategy to increase and enhance our technological capacity”.ii

The Committee recently considered an SSI which extends the powers to impose various restrictions in prisons due to COVID-19. We raised a number of concerns with the Scottish Government, Scottish Prison Service and HM Inspector of Prisons Scotland about some of the proposals and have agreed to monitor how these powers are used in practice.

Other issues

The Committee discussed several other issues relating to COVID-19 at the roundtable meeting including—

The recovery, reset and renew programme of the Scottish Fire and Rescue Service

How COVID-19 might impact on any reform of the regulation of the legal profession

The impact of COVID-19 on Police Scotland recruitment and training

Suggestions that individuals were falsely claiming to have COVID-19 symptoms in order to avoid attending court

The impact of COVID-19 on justice social work, including the need to return to face-to-face contact

The impact of COVID-19 on the legal aid system (this is discussed in a separate note of the roundtable meeting on legal aid).

Conclusions and recommendations

Conclusion: It is clear to us that two of the key priorities in this parliamentary session, will be—

The progress being made in reducing the court backlog. On this, we are deeply concerned at the impact of delays on the victims of crime, the numbers of prisoners on remand, and other participants in the judicial process. Whilst we understand why the backlog has increased, we want to avoid any further slippage in the timescales for clearing this. This is something we intend to monitor to assess what progress is being made and we set out specific proposals in the recommendation below;

A proper assessment of the merits of ‘digital justice’. We understand why a number of initiatives were introduced as a result of COVID-19. These have, generally speaking, been welcomed. Indeed there appears to be support for many of them to continue. But real and substantial concerns have been raised about making some of these changes permanent. Our view is that a proper assessment has to be made of the various proposals for ‘digital justice’. They should only progress if there is genuine merit in the proposals, rather than simply being a matter of a cost saving or administrative convenience. Whilst we accept there may never be unanimity, there must be a general consensus from the main participants and we cannot make fundamental changes to how our court system functions and the rights of individuals involved without full and proper debate.

Recommendation: The Committee intends to keep both these priority issues under review this session to ensure progress is made as indicated. The Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service continues to publish regular updates on progress in reducing the court backlog. The Committee will also hold an evidence session with the Cabinet Secretary for Justice and Veterans, following the conclusion of the consultation on COVID-19 recovery. This will be a chance to question the Cabinet Secretary on the Scottish Government’s position on returning to normal operations in the court system and the merits, or otherwise, of making various ‘digital justice’ proposals permanent.

Conclusion: The Committee will also seek to be involved in the scrutiny of any forthcoming legislation brought in by the Scottish Government either to further extend temporary measures or to make certain changes to the courts system permanent.

Conclusion: An important theme this parliamentary session will be how Scotland’s prisons are recovering from the impact of the pandemic. We would like to highlight two priority issues where we must see progress made in the near term-

The reinstatement of purposeful activities in prisons;

Progress on improving arrangements for visits and contact from families and friends, or the provision of digital alternatives where this is not possible.

Conclusion: The Committee understands the immense challenges on the Scottish Prison Service in managing the pandemic within our prisons. The Committee pays tribute to the management of the Scottish Prison Service in our prisons and also all of the prison officers and staff that work in them. Their service and dedication is not in question. Nevertheless, in our view, there are improvements that need to be made in terms of how the Scottish Prison Service is responding to COVID-19 and the regimes that are currently in place.

Recommendation: The Committee recommends that the Scottish Prison Service provides—

A detailed plan for the reinstatement of purposeful activities in prisons, including a timetable for when particular categories of activities will resume.. At present, the law states that remand prisoners cannot be required to work but we acknowledge that some may wish to. However, such services are also prioritised for long-term convicted prisoners as a matter of statutory obligation; this limits the resources available for remand prisoners. We need to address the long-standing question of what can be done to ensure that prisoners held on remand and on shorter sentences would have the option to benefit from these activities;

As a minimum, all prisoners including those on remand should have regular access to exercise and time outdoor for fresh air, and consideration should be given to what other activities would be suitable for prisoners on remand;

Information on progress made in resuming in-person visits, including how arrangements may differ from pre-COVID-19.

An update on any inquiries made by the Scottish Prison Service into the use of hacked mobile phones, downloaded e-SIM cards etc by prisoners and a commitment that any problems identified have been addressed.

A commitment that video/mobile technology will continue to be an option for prisoners to contact friends and family members and support services, and that the use of this technology will be expanded throughout the estate in a regulated and controlled manner.

Conclusion: In summary, whilst we understand the reasons for the severe regimes within prisons that had to be put in place because of the pandemic, restrictions on meaningful activities, association, contact with families etc should only be in place where strictly necessary and all efforts made to remove them as soon as possible and alternatives put in place in the meantime.

Conclusion: The Committee will make its views on the wider issues in prisons and on prison reform known in a separate report.

Conclusion: COVID-19 has had a significant and disruptive impact on the justice sector.

Conclusion: As a Committee, we recognise that each and every one of the delayed trials caused by the backlogue in the Courts system means justice for the victims has been put on hold and the rights of the accused to be heard in court have been curtailed. We are particularly concerned about the disproportionate impact of delays on victims of gender-based violence who are predominantly women and girls. Cases of serious sexual violence make up 80 to 85 per cent of cases that proceed to trial in the high court.

Conclusion: The Committee’s focus in the early part of this parliamentary session will be to—

Monitor the use of any temporary provisions, regulations, or powers given to authorities in the justice sector as a result of COVID-19 to ensure their use is necessary, proportionate and appropriately time-limited.

Assess what progress is being made in the justice sector to recover from the impact of COVID-19 and return to previous standards of service levels for users

Ensure that where administrative and technological innovations are retained, it is only after they have been assessed on their own merits as warranting retention.

Recommendation: In the section on 'Other Issues' the Committee has identified these as important issues which it plans to return to once the immediate priorities noted in this report have been addressed.

PRISONS AND PRISON POLICY

Introduction

On 15 September 2021, the Criminal Justice Committee held a roundtable meeting about prisons and prison policies. The Committee took orali and written evidenceii iii ivfrom a number of stakeholders.v

The roundtable identified a series of issues that need to be addressed in both the short and longer-term.

Many of these issues are long-standing ones which policy-makers have historically struggled to address. We want to see progress during this parliamentary session. A number of these issues were investigated by our predecessor committees and are not new. It is our view that we cannot keep scrutinising the same issues and recommending changes without seeing signs of substantive progress.

In addition to the issues highlighted in this report, our separate chapter on the impact of COVID-19 on the justice sector discusses some additional points regarding prisons and responses to the pandemic.

Remand

The first priority issue we wish to highlight is the high number of prisoners on remand, and the experiences which some remand prisoners have faced in prison.

The Howard League Scotland noted that there has been a significant rise in the number of people held on remand in Scotland (then at approximately 24% of the prison population), particularly amongst young people. In recent weeks, the Cabinet Secretary told the Parliament that remand is now at 30 per cent of the prison population”, describing this as “too high”.

Wendy Sinclair-Gieben, HM Inspector of Prisons for Scotland told us in written evidence:

“One of my repeated findings is the cultural acceptance of a hierarchy of entitlement in prisons where in Scotland remand prisoners and those labelled 'non-offence protection' are rarely afforded access to rehabilitative activity. For them 22 hours a day locked up in a room often not designed for one but holding two is routine.”i

Dr Katrina Morrison of the Howard League Scotland argued that remand prisoners should have the same opportunities for work and access to programmes as the rest of the prison population.

Phil Fairlie of the Prison Officers Association Scotland noted the impact of the number of remand prisoners on overcrowding in prisons.

Bruce Adamson, the Children and Young People’s Commissioner, expressed concern about the number of children under 18 on remand in young offenders institutions. The issue of holding children in prison is considered further below.

Women and children

A second issue which emerged from the roundtable meeting was the impact of prison on two particular groups of prisoners: women and children. There was discussion about whether and when it was appropriate for women and children to be imprisoned.

Women

Wendy Sinclair-Gieben, HM Inspector of Prisons for Scotland described visiting a women’s prison—

"What stands out when you walk around is the number of women who are apparently mentally unwell. It is clear to me that, if we had a presumption of liberty for women, particularly when they are doing a good job caring for their children, the number of women coming into custody would not be so high.”

Dr Katrina Morrison of Howard League Scotland told us that women in custody are especially vulnerable. A number of women in prison have head injuries, which are thought to be mostly as a result of domestic violence.

The written submission from the Scottish Centre for Crime and Justice Research noted that—

“Considerable attention has been given to the prison estate for women over recent years by the Scottish Government, Parliament, and Prison Service. Many reports have made detailed recommendations on how best to reduce the number of women in custody (latterly, the Commission on Women Offenders, 2012) with the current development of HMP Cornton Vale and plans in place for SPS Community Custody Units. However, to date, attempts to reduce the number of women in prison have had limited impact.”

Children

Bruce Adamson, the Children and Young People’s Commissioner, commented on the situation with respect to children—

“…children under 18 should not be deprived of their liberty in prisons or young offenders institutions. Instead, we must ensure that children receive really good-quality intensive support, perhaps in a secure setting but not in the prison system. The situation needs to change urgently.”

The proportion of children held on remand has increased.

Wendy Sinclair-Gieben, HM Inspector of Prisons for Scotland, noted in her written submission that childhood has been accorded special status in international human rights law. She noted that contact with the criminal justice system is often detrimental to young people’s wellbeing and development. She raised the questions as to whether “perhaps now is the time to also consider being the first UK nation to remove children from prison”.

Substance misuse in prisons

A third issue we wish to highlight is the problem of substance misuse in prisons. We have also commented more widely on drug misuse in the criminal justice system elsewhere in this report.

In terms of prisons, Wendy Sinclair-Gieben, HM Inspector of Prisons for Scotland told us—

“Drugs in prison are a major issue. I have talked about revising the prison rules, and one thing that needs to happen is a reduction in the amount of drugs coming in through the post...”

Wendy Sinclair-Gieben also added that—

“On substance misuse, I would really like the committee to look at the evidence around diversion, depenalisation and all the issues that will help us to reduce the prison population and, I hope, make the replacement of Greenock and Dumfries prisons, and even Barlinnie, unnecessary. That would be my dream.”

We heard that one technique to illegally bring drugs into prisons is to soak letters in drugs which can then be posted to a prisoner.

Teresa Medhurst, Interim Chief Executive of the Scottish Prison Service, noted that “the methods and means by which people can traffic them are, for the most part, well known, but we are considering other measures that we can take, particularly with mail coming into prisons, to minimise those risks as much as possible”.

In recent weeks, the First Minister and the Cabinet Secretary for Justice have given a commitment that the Scottish Government plans to legislate (via secondary legislation) to change prison rules to permit prisoners’ mail to be photocopied and thereby reduce the smuggling of certain drugs into prisons via this route. An SSI has now been laid in the Scottish Parliament and will be considered by the Committee early in the New Year.

There was also discussion about the use of Buvidal as an Opioid Substitution Treatment in Scotland's prisons. Teresa Medhurst noted that it “has much more potential to minimise risk to individuals and ensure that people can be better supported on their recovery journey”.

Rehabilitation and alternatives to prison

At the roundtable meeting there was a wider discussion about the role of prisons.

One issue which was raised was how to rehabilitate someone who has committed a crime and whether prison is the best setting for that rehabilitation to take place.

Wendy Sinclair-Gieben, HM Inspector of Prisons for Scotland did not consider that it was—

“We have got it wrong. We will need to undertake significant change to turn that concept around, to look at rehabilitation and support in the community and to remove the presumption of punishment as a way out.”

Professor Fergus McNeill of the Scottish Centre for Crime and Justice Research noted that rehabilitation in prison is “really difficult” and the evidence on rehabilitative programmes is that they work better in communities than in prisons–

“The obvious reason for that is that you can try to learn something in an institutional environment, but the first thing that you have to do when you are released is transfer that learning to a new context.”

We also discussed at the roundtable meeting whether more should be done to prevent individuals being imprisoned in the first place.

Professor Fergus McNeill told us—

“Any criminologist would tell you that, if you want to reduce crime, you invest way upstream of the criminal justice system and that, when you invest in criminal justice, you invest in diversion at every possible turn."

Several witnesses argued that reducing the prison population would help address some of the problems faced by prisons such as capacity issues.

Allister Purdie of the Scottish Prison Service noted—

“To refer to Fergus McNeill’s point, the ideal position further down the line would be for us to stop bringing people into prison and to stop building a new prison in Glasgow for 1,200 people.”

The issue of overcrowding has been cited as a major barrier to improving conditions in prisons in Scotland. In particular it has impacted on the rehabilitation of prisoners. Professor McNeill noted—

“we do not rehabilitate prisoners well, we do not prepare them for release well and we do not support them on release well, because our system is chock-a-block with people who should not be in it.”

Prison estate

This Committee has commented previously on the need for capital investment to modernise the prison estate. This includes both major investments in upgrading prisons such as HMPs Greenock and Dumfries, and shorter-term investments to improve the current conditions in the existing estate.

In evidence to the Committee, Wendy Sinclair, HM Inspector of Prisons Scotland expressed concerns about resources available for improvements to the prison estate. She said she saw:

“no evidence to suggest that the SPS is sufficiently resourced to make adequate progress with these key capital projects and strategic initiatives alongside other competing pressures and important but routine maintenance projects.”

She added that:

“The recent investment in HMP Glasgow and HMP Highland is welcome, but well overdue, and still leaves Scotland operating prisons with Victorian features that bear no resemblance to a modern prison system, especially in HMP Greenock, HMP Dumfries and parts of HMP Perth. These establishments are expensive to run and maintain and utterly inadequate for the care and accommodation of older and disabled prisoners, which we expect to become an increasing issue for the SPS given recent trends regarding the prosecution of historical sex crimes. There needs to be sufficient investment by the Scottish Government and SPS to support the design and planning of replacement facilities for these three prisons, while recognising that planning consent and securing a site might put back the point at which major construction costs hit. Similarly, while welcoming the structural and philosophical reforms around the women’s estate, further investment will be required to remove the current dependency on using accommodation in the male estate for women".

A particular issue is how the prison estate can accommodate certain types of prisoners, such as elderly people and prisoners with disabilities or mental health issues. The issue of modernising the prison estate is also linked to the more fundamental question of overall prison numbers in Scotland.

We have also said that we must build on existing efforts to stop the revolving door in our prisons and look at greater funding for effective alternatives to prison where appropriate.

In our recent pre-budget report, the Committee concluded that “there is a case for sustained, above inflation injection of funds into the prison budget, allied to a clear, long-term strategy to address these problems.”

Other issues

The issues we have identified above are, of course, not the only issues facing prisons in Scotland. There are many other important issues which were touched on during the roundtable meeting, for example—

Reforms to the day-to-day prison regime, such as greater use of in-cell technology. There is a need to ensure that prison rules are kept up-to-date so that prisons can use in-cell technology in order to take part in purposeful activities and maintain family contacts;

Deaths in custody and deaths following release;

Post-release support;

The challenges of accommodating a complex prison population (for example, older prisoners, prisoners guilty of sexual offences, and prisoners with links to organised crime).

Conclusions and recommendations

Conclusion: A priority issue this parliamentary session for organisations in the justice sector must be addressing the high numbers of prisoners on remand and improving the experience of those prisoners who must be held on remand. Our predecessor committee reviewed the situation back in 2018i and, over three years on, there is no discernible sign of substantive progress on the numbers being held despite the concern of many. That cannot continue.

Recommendation: The Committee recommends that the Cabinet Secretary for Justice and Veterans provides details on how the Scottish Government proposes to address the specific concerns about the use of remand highlighted in the roundtable meeting. The Committee is aware, for example, that the Scottish Government plans legislation in this area (a Bail and Release Bill). We request an update on the timing of that legislation and what it plans to cover.

Conclusion: A priority issue this parliamentary session must be to improve how women and children are treated in the prison system and whether alternatives to prison may, in some cases, be more appropriate. This is a subject on which there seems to be widespread agreement that progress needs to be made, but less success in delivering change.

Recommendation: The Committee recommends that the Cabinet Secretary for Justice and Veterans provides details on what specific policies and initiatives the Scottish Government are proposing to improve the treatment of women and children in the prison system. The Committee recommends that the Cabinet Secretary sets out his views on the specific concerns raised by the Children and Young People’s Commissioner about children in the prison system and the Commissioner’s proposals to address these concerns.

Recommendation: As a short-term measure, the Committee asks the Scottish Government when it will fulfil its promise that under 18s should not be held in prison and that secure care should be used instead. The Committee believes that, in principle, children under the age of 18 should be held in secure care and not in prison. Therefore, we also ask when the Scottish Government will fulfil a commitment made by the Deputy First Minister in session 5 to review why it is necessary to move someone from secure care to HMP YOI Polmont after they turn 18 years of age, even if they only have a short time left on any sentence (see also the section on secure care).

Conclusion: A priority issue this parliamentary session should be addressing the problem of substance misuse in prisons. It is clear that the misuse of drugs in prisons is rife and more needs to be done both to prevent drugs from coming into prisons and to rehabilitate prisoners who use drugs.

Recommendation: The Committee recommends that the Scottish Prison Service provides details about what programmes are currently available in prisons to rehabilitate users of drugs and how much funding is associated with these initiatives. The Committee welcomes recent indications from the Cabinet Secretary and the First Minister that the Scottish Prison Service will, after consideration of operational and legal issues, implement a new policy in respect of photocopying prisoners’ mail. The Committee proposes to scrutinise the relevant SSI and how it is implemented. It is vital that this issue is taken forward without unnecessary delay. Lastly, the Committee recommends that the Scottish Prison Service provides an update on the progress made in rolling out the use of Buvidal across the prison estate.

Conclusion: We have also called elsewhere in our budget report for further investment in recovery cafes within each prison where appropriate.

Recommendation: We have highlighted some of the key questions about the role of prisons in Scotland which have been raised at the roundtable meeting. For example, are prisons the best place to rehabilitate people? Should more be done to reduce the number of people sent to prison where this is appropriate? These are fundamental issues which reach beyond the day-to-day operation of prisons. The Committee recommends that this parliamentary session the Scottish Government and others in the justice sector should do more to directly tackle these fundamental questions in the interests of progress.

Conclusion: There are numerous challenges facing prisons in Scotland, many of which we touched on in the roundtable meeting and also in previous parliamentary sessions. We have highlighted in this note some of the issues we consider to be an immediate priority. In our inquiry and scrutiny work this parliamentary session, we will play our role in encouraging those in the justice sector to make progress in taking these issues forward. It is not acceptable to us to spend another parliamentary session commenting on the same issues and making recommendations for change. Greater action and progress are needed now

Recommendation: In the section on 'Other Issues' facing prisons and prison policy in Scotland, the Committee has identified these as important issues which it will consider in addition to the immediate priorities which have been noted in this report.

MISUSE OF DRUGS AND THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM

Introduction

On 27 October 2021, the Criminal Justice Committee held a roundtable meeting about the misuse of drugs and the criminal justice system. The Committee took oral iand written evidenceii iii ivfrom a number of stakeholders.v

Every single death brought about by the misuse of drugs is a tragedy, not only for the victim, but also for their families, friends and loved ones. Behind the statistics, is a person and a family who have lost someone close to them.

Sadly, the statistics for drug deaths in Scotland are stark. In July 2021, the National Records of Scotland (NRS) published a document (Drug-related deaths in Scotland in 2020) which reported that there were 1,339 drug-related deaths in 2020. This is a 5 per cent increase on the previous year and the largest number ever recorded since records began in 1996. Drug-related deaths have increased substantially over the last 20 years. The NRS report shows that there were 4.6 times as many deaths in 2020 compared with 2000.

The NRS report states that Scotland’s drug death rate was 3.5 times that for the UK as a whole, and higher than that of any European country.

According to a recent reportvi from the Scottish Government, in 2019-20, the vast majority of drug possession offenders were male (85%). The median age of an offender was 29 years old, with almost two thirds (63%) being between 20 and 39 years old

Drug misuse and the crimes often associated with their use then translate through to impacts in the criminal justice system. For example, in Scotland’s prisons, the Scottish Prison Service’s biennial Scottish Prisoners’ Survey most recently reported that 41% of respondents stated that their drug use was a problem for them on the outside, 39% said that they had used illegal drugs whilst in prison, and more than one in ten (12%) stated that they only started using drugs whilst in prison.

Figures released to the media under FoI laws showed there were 229 recoveries of suspected psychoactive substances across the prison estate in June 2020. In June of 2021, there were 421 such seizures. The synthetic cannabinoid "Spice", and "street" benzodiazepines, such as Etizolam, are now thought to be the dominant drugs in prisons.

The impact of drug misuse in Scotland is also felt in terms of the time and resources required in multiple sectors, namely the police, the courts, criminal justice social work, and third sector support bodies.

The Scottish Drug Deaths Taskforce

In 2019, the Scottish Government established the Scottish Drug Deaths Taskforce in an effort to tackle drugs misuse in Scotland. The Taskforce was tasked with helping to tackle Scotland’s unique challenge by identifying evidence-based strategies that will make a difference to those most at risk, and using its expertise, influence and networks to put these into practice. The Taskforce membership features those with health, social services, research, police, criminal justice and emergency service backgrounds but also those who bring lived experience of drug and addiction issues.

Since the Taskforce was formed in 2019, it has made a number of recommendations to a range of stakeholders. This includes the Scottish Government, the Lord Advocate, Police Scotland, the Scottish Prison Service, Health Improvement Scotland and the NHS. These recommendations relate to a wide range of topics that the Taskforce believe would have a positive impact on tackling the drug problem faced in Scotland and ultimately save lives. Some of these recommendations date back to April 2020.

The Committee heard that the Taskforce views its role as putting a spotlight on areas where change is required. There are already Taskforce recommendations for many of the issues which were raised at the Committee evidence session. These are summarised below.

As such, it is not the Committee’s intention in this report to try to duplicate the work of the Taskforce. It has already studied many of the issues raised by the roundtable participants and made a series of detailed recommendations in its reports.

A person-centred approach

Witnesses at our roundtable described experiences of seeking help with drug issues and it not being provided for a variety of reasons. These included: being told their addiction was “not severe enough to need treatment”; no treatment being available for the drug they used (cocaine); no phone service or services provided at evenings and weekends; people referred and either not then dealt with at all, not dealt with in a timely fashion, or referred somewhere that was not appropriate, which offered no real remedy for them.

Written evidence from the Scottish Institute of Policing Research (SIPR) refers to a gap between policy and practice. The Committee heard that the services available did not meet demand, and that some services, such as residential rehabilitation and community day programmes are either no longer provided or have been privatised. This means that often services are targeted at the most critical end of the spectrum. As well as gaps in provision, there are overlaps in the services provided. There is a lot of work being undertaken in isolation, which needs to be co-ordinated.

Following the evidence session, Police Scotland confirmed that since April 2019, the number of individuals records as accepting arrest referrals, which are for people within police custody, is 2287. The total number of people recorded on the Interim Vulnerable Person’s Database (iVPD) with a Drug Consumption Marker from 2018 to 2021 inclusive are 39,822i . They confirmed that there is disparity of services available across Scotland, which depends on the third sector or statutory support is available locally. They indicate that “The lack of standardised support for someone with complex needs is challenging with some areas unable to provide direct support or an appropriate referral as their needs do not meet a specific criteria set”.

The Committee heard that a whole-system approach should be adopted, which looks at what is provided, where funding is allocated, and how this can be improved in terms of efficiency and effectiveness.

Witnesses indicated that there is a need for a wider range of community services for people for whom prison should not be an option. One recommendation was the provision of access to a care manager, who is able to understand and treat the reasons for drug use, such as trauma, poverty, neglect and abuse.

The Taskforce has a number of recommendations which seek to address these issues. One recommendation is that a costing exercise should be undertaken, reflecting that a push to increase the number of people in services must recognise the increased pressure this will put on these services and the needs that may flow from it. This would enable costing of a long-term sustainable system of care.

A trauma-informed response

Witnesses also spoke about the importance of interactions with police officers, social workers, drug counsellors, sheriffs and prison officers, being trauma-informed to reflect the health issues of the person and the underlying causes of their drug use.

The Committee heard concerns that police officers are not provided with the necessary training to assess those with mental health issues to assess whether they should be taken to a police cell or require medical treatment. Police Scotland and the Crown Office told the Committee that they were looking to introduce a trauma-informed package for officers and criminal justice practitioners respectively.

Police Scotland indicated that their officers are now more trauma-informed and more aware of individual needs. However, they confirmed that there are no ‘rigid guidelines’ for officers, who need to make decisions based on their professional judgment. The Committee also heard that more solicitors and sheriffs are trauma-informed.

The Taskforce recommends that the Scottish Government works with justice partners to support the adoption of the Stigma Strategy, trauma informed and family inclusive practice and the adoption of distress-based interventions.

Diversion from prosecution

The Committee heard that prosecutors in Scotland have a wide range of disposals which range from a warning, a fine, a diversion, a fiscal work order or, in some cases, prosecution. They are able to select the option that will achieve the most appropriate outcome for the individual offence and the individual offender. It is then for the local authority to provide a support programme for that person.

Following the evidence session, the COPFS confirmed that in relation to the 1,000 accused persons offered diversion in 2020-21, 605 were completed or remain ongoing. They explained that there can be a number of reasons why a diversion is not completed. This might be the local authority’s assessment that the individual is unsuitable, the person may be unwilling to engage with diversion and fail to participate or they may reject it as an option. The COPFS indicated that, as a prosecution service, it does not and cannot undertake continued monitoring of accused persons who have completed a diversion programme.

Witnesses indicated that there is influential evidence to suggest that public money is better spent on community-based remedies rather than reverting to prison sentences.

One issue is whether local authorities have sufficient resources to provide the diversion programmes that they would wish to in relation to offenders who are referred to them. Another issue raised is the removal of people who do not attend regularly and the unnecessary inflexibility of the programmes.

In her written evidence, Liz Aston of SIPR and Edinburgh Napier University, refers to the role of police officers in diverting people to drug services. At present, this can only be done at the point of arrest. In other parts of the UK there are examples of police-led diversion schemes, such as Thames Valley Police’s Drug Diversion scheme, which provides direct access to drug services without admission of guilt and can be used for possession of any category of drug.

The Taskforce’s Criminal Justice and the Law Subgroup is working on recommendations around diversion from prosecution and will report between July 2022 and December 2022.

Access to treatment

The Committee heard that currently, only 35 per cent of the 60,000 people with drug problems are in treatment, whereas in England, more than 60 per cent of people with drug problems are in treatment.

Witnesses told the Committee that the implementation of the Medication-Assisted Treatments [MAT] standardsi, which includes same-day prescription is key. These are evidence-based standards to enable the consistent delivery of safe, accessible, high-quality drug treatment across Scotland. The Scottish Government has set a deadline of next April (2022) to deliver the MAT standards. The Committee heard that these standards should also be implemented in prisons, as this is not currently available.

The Taskforce recommends that the implementation of MAT Standards must be scaled up at pace. To enable this the Taskforce recommends that formal standards and indicators are developed by Health Improvement Scotland by the end of 2021. The Scottish Government will have a vital role in supporting this roll out by ensuring that Chief Officers take accountability for delivery of the standards at local level. The Taskforce also supports the devolution of licensing for Heroin Assisted Treatment (HAT) premises to allow the single-office co-ordination of premises and prescriber licensing and the Scottish Government should support and promote a national roll out for HAT.

The prison service

A key issue raised during our roundtable was the lack of support for those before, during and after their prison sentences, including putting in place the necessary support prior to the release of prisoners.

Witnesses described the impact on people of being imprisoned, the ease in which drugs can be accessed within the prison estate, the use of drugs as a coping mechanism, and the lack of provision in place to help people succeed upon release which can result in them returning to drug use.

In April 2020, the Taskforce recommended that adequate throughcare provision be made available to prisoners on liberation, including: access to a GP and continuity of Opiate Substitution Therapy (OST) provision, and that a Take-Home Naloxone (THN) supply be provided for all prisoners with a history of substance use on liberation, and their families.

More recently, the Taskforce recommended the reintroduction of throughcare support officers and consideration of funding of this service, an end to Friday liberations or in advance of a public holiday,i and that alternatives to remand and imprisonment should be considered, which should include bail supervision and residential rehabilitation.

Law reform

During our roundtable, the Committee heard views that the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 should be reformed by the UK Government to reflect the different drugs now available and how they are consumed, and to improve practice in Scotland.

The Committee also heard views that it is not necessary to change the Act to enable the use of safe injection facilities. Some witnesses recommended that the Scottish Government and others find ways to facilitate the use of safe consumption spaces as a drug death prevention intervention.

Other regulatory changes suggested include the regulation of pill presses, introducing a more informed way to test for the drugs that people are using, ensuring that diamorphine-assisted treatment is made available in the prison system, and looking to expand the use of drug treatment and testing ordersi (DTTOs). There were conflicting views from witnesses on whether the regulation of pill presses would work, with a suggestion that alternatives to street drugs should be regulated and provided to avoid people seeking out illicit supplies.

The Taskforce recommends reform of the 1971 Act, as well as asking the Scottish Government to do more to maximise flexibility under the current legislation. It also recommends a review of the use of DTTOs. In September 2021, it published a report on drug law reformii, which covers this issue in detail.

Following the evidence session, the Lord Advocate told the Committee that she would consider a “precise” and “specific” proposal for a drugs consumption room in Scotland if this was presented to her.

Use of Naloxone

The Committee heard a lot of support for the use of Naloxone nasal spray by those in the criminal justice sector, and more widely, to revive people who have overdosed on drugs. Police Scotland indicated that there was little concern about the police use of Naloxone, with the exception of the Scottish Police Federation’s (SPF) views.

Following the evidence session, the SPF provided a written submission on this point. It states that “The SPF considers that Scotland’s drugs death crisis is a tragedy that deserves much more focus, effort and attention than “sticking plaster” approaches such as issuing police with Naloxone Spray”. The SPF believes that “the solution to tackling the drugs deaths crisis is not this”. The SPF believes that police officers have a “role in the response to drugs misuse but that role is not a medical one”

The pilot of police officers volunteering to carry and administer Naloxone is currently subject to academic evaluation. Following the evidence session, Police Scotland confirmed that the Naloxone Test of Change programme has concluded, and an independent evaluation of the process is being undertaken by the Public Health Surveillance Sub-Group of the Drugs Death Task Force (DDTF) and the Scottish Institute of Policing Research. It is expected to be completed in early 2022. Anonymised data from the project will be available for use in academic papers, conference presentations and presentations to policy makers.

Police Scotland’s drug harm reduction team will consider any learning from the evaluation and make recommendations to the Chief Constable.

Effectiveness of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002

Prosecutors can proceed to recover criminal profits only where a prosecution results in a successful conviction and where there are assets to be recovered.

There is a civil recovery system, dealt with by the Civil Recovery Unit (CRU), which acts on behalf of the Scottish Government. The aim of the CRU is to use civil proceedings to disrupt crime and to make Scotland a hostile environment for criminals. It pursues that aim by investigating and seeking to recover cash and assets which have been obtained through crime. The CRU is a multi-disciplinary team of around 24 members comprising financial investigators, forensic accountants and lawyers. It is part of the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service (COPFS) but exercises its functions separately and independently. Operational responsibility for the CRU lies with the Lord Advocate and Solicitor General in their capacity as Scottish Ministers.

Serious crime prevention orders

The Committee also heard that consideration should be given to changing the regulations on how drugs are dealt with, such as drug trafficking and supply, as the current approach is not working.

Following the evidence session, Police Scotland provided further information on whether it has sufficient resources to effectively monitor people who are released under a serious crime prevention order (SCPO).i

Police Scotland confirmed that there are currently 71 SCPOs within the scope of its responsibility, The SCPO Subjects are managed by Local Policing Divisions. They are supported by the National Specialist Crime Division, SCPO Unit at the Scottish Crime Campus, which co-ordinates the application for new Orders as well as the process for SCPO subjects entering the community.

Conclusions and Recommendations

As stated above, this short summary report from our roundtable of 27 October 2021 is not intended to replace what would have been produced by an exhaustive and detailed inquiry. Neither is this report intended to be an alternative for the detailed work of the Scottish Drug Deaths Taskforce and the recommendations it has made to date, as well as those made by academics and other experts.

Recommendation: We do believe, however, that faster progress is needed in this area, which reflects the seriousness of the situation. Some of the recommendations made by the Taskforce date back to April 2020 and it is not obvious to this Committee that these are being implemented quickly or at all. We would like to see much faster progress being made on implementing the recommendations of the Taskforce.

Conclusion: The record level of drug deaths in Scotland, the personal tragedy behind each death and the huge impact of drug misuse on the criminal justice system is one of the defining challenges in this parliamentary session.

Conclusion: In addition to wanting to see rapid progress with the recommendations already made by the Taskforce and the completion of other parts of its work, the Committee believes that certain other measures are needed to be taken forward in the short and longer-term. These are outlined below.

Recommendation: In our view, from the evidence heard, there appears to be a service gap between what is currently being provided to help those with a drug problem and what is needed. This gap needs to be addressed. As such, we believe that rapid progress needs to be made with:

The recommendation of the Taskforce that there should be same day access to Opiate Substitution Therapy alongside the provision of Take-Home Naloxone supply.

A further roll out of trauma-informed training across the criminal justice sector where this has not already been provided.

Consideration given to providing additional resources for local authority schemes aimed at diversion from prosecution and greater flexibility and understanding shown to the participants, in the administration of those schemes.

Consideration of whether there is scope to replicate the kinds of schemes in Scotland that are in place elsewhere in the UK which provide for diversion of prosecution not only at the point of arrest. The concept of diversion will only work if there are appropriate schemes to divert people to and the Committee would like to see evidence of what these schemes are. Therefore, the Committee invites local authorities and others to confirm the resources in place to provide these schemes.

Recommendation: In terms of our prisons, a separate report by the Committee has made a series of recommendations on how we can tackle drug misuse in these institutions. We would add the following to these recommendations:

Throughcare officers and the throughcare system has to be reinstated as soon as possible.

Consideration needs to be given to improving support prior to release in terms of access to suitable housing, health care, and addiction support if required.

Consideration needs to be given to changing legislation governing Friday liberations as these have shown to be situations where an ex-offender stands a much greater risk of reoffending due to the lack of support available over a weekend.

Consideration given to a greater use of alternatives to custody, such as bail supervision and residential rehabilitation, with adequate funds in place for these to work.

Recommendation: In terms of reform of the laws that underpin the misuse of drugs and the criminal justice system, we note the views of the Taskforce that changes are needed. We do believe that consideration needs to be given to making changes to the law in the following areas:

The regulation of pill presses;

The expansion of the use of Drug Treatment and Testing Orders.

Recommendation: We also note the views of the current Lord Advocate that she would give consideration if a detailed case was made to her on the use of safe consumption rooms. We would like to understand what a ‘detailed case’ would contain and would urge the Scottish Government and the Taskforce to look into this as a matter of urgency and provide us with the details of how this might work in practice. This would be with a view to the establishment of a pilot safe consumption room.

Conclusion: The Committee notes the views of the Scottish Police Federation about the use of Naloxone by police officers but considers that, with appropriate safeguards and training, it should be possible for this to continue to be used by officers on a voluntary basis who may often be the first person called to an incident. We look forward to the speedy completion of the external evaluation of the pilot and would be minded to support the administration of Naloxone by those across the criminal justice system (police, prison and fire and rescue officers), and its use more widely.

Recommendation: The Committee would also appreciate further information and details on the work of the Civil Recovery Unit to determine what success it is having in seizing assets relative to the value of the sums of money that can be made by criminals, particularly serious and organised crime groups through the supply of drugs.

Recommendation: Finally, this Committee recognises that reform of the criminal justice system is just one component of the efforts to tackle Scotland’s record drug deaths. Health measures and wider social justice and anti-poverty efforts are equally required. As this Committee is recommending that faster progress is required to tackle the misuse of drugs, we intend to approach the members of the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee and the Social Justice and Social Security Committee with a view to holding a joint, public meeting in early 2022 with the relevant Ministers and the senior members of the Taskforce to scrutinise the progress being made in delivering the Taskforce recommendations and the remainder of its work.

VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN AND GIRLS

Introduction

On 22 September 2021, the Committee held a roundtable evidence session on domestic abuse, gendered-violence and sexual offences. The Committee took orali and written evidenceii from a number of stakeholders.iii

Following that evidence session, the Committee held informal meetingsiv on 24 November to hear from survivors of these crimes about their personal experiences of the criminal justice system, as well as practitioners. We are immensely grateful to all who took the time to speak with us. A note of the issues discussed with them is available online.

There has been much work done by the Scottish Government and others to try to improve the experience of survivors of domestic abuse, gendered-violence and sexual offences in the criminal justice system, particularly for crimes of violence against women and girls.

In 2014, the Scottish Government and the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities (COSLA) published Equally Safe: Scotland’s Strategy to Eradicate Violence against Womenv. Additionally, the Victims and Witnesses (Scotland) Act 2014vi, the Domestic Abuse (Scotland) Act 2018vi, and the Vulnerable Witnesses (Criminal Evidence) (Scotland) Act 2019vi were introduced. In March 2021, the Final Report from the Lord Justice Clerk’s Review Group: Improving the Management of Sexual Offence Casesvi, was published, setting out detailed proposals to improve the system.

The Committee considered whether these measures have improved the experience of victims and witnesses, whether there are any unintended consequences, and what more can be done to improve the criminal justice system for victims of these crimes.

What is clear is that despite the best efforts of all concerned and no end of reports and reviews, these crimes are on the increase. According to the Scottish Government, sexual crimes were 12% higher in October 2021 compared to October 2020 (increasing from 1,093 to 1,221 crimes), and 8% higher compared to October 2019 (increasing from 1,134 to 1,221 crimes.

Sexual assaults increased by 29% compared to October 2020 (from 336 to 434 crimes). Rape and attempted rape decreased by 4% compared to October 2020 (from 215 to 207 crimes), and increased by 2% compared to October 2019 (from 202 to 207 crimes).

The rise in “other sexual crimes” since 2019 (up 6%) was driven by crimes including communicating indecently, coercing a person into being present/looking at sexual activity, disclosure of intimate images and voyeurism.

These summary reports are not intended to be a replacement for an exhaustive and detailed inquiry. They present some of the issues that were identified during our roundtables as key, and outline some actions that are needed in the short and longer-terms.

Tackling the causes of violence against women and girls

The Committee considered the causes of violence against women and girls, why it has increased, and what can be done to address the causes.

Dr Marsha Scott, Scottish Women’s Aid, told the Committee that women’s inequality is the cause and consequence of all the forms of gender-based violence against women and girls. Dr Scott stated that, although there have been some important process changes and various measures introduced, there has been little impact on outcomes for women. Dr Scott said that to prevent violence against women and girls, we need to enable them to leave abusive relationships, explaining that:

“However, unless we get serious about dealing with unpaid work, the lack of childcare, the pay gap, women’s homelessness as a result of domestic abuse and all the things that enable violence against women and girls, the fact remains that, although we will continue to be better at responding to it when we see it, we will have done nothing about preventing it. .”

These issues were also raised during the informal meetings we held with survivors and frontline support workers. The Committee heard that women and girls must be supported to leave abusive relationships. They can face financial hardship, especially if they become single parents. They want to be able to keep working to support their children and there needs to be support measures put in place to enable them to do so.

Rabia Roshan of Amina—the Muslim Women’s Resource Centre, told the Committee that these are the same causes for violence against women and girls in black and minority ethnic communities, but there are also cultural and religious reasons, which make it difficult to tackle. Ms Roshan explained that the provision of sex education and understanding consent need to be improved, and described some of the work Amina does, telling the Committee that:

“A lot of our work is about breaking down barriers, separating the two and challenging the misconceptions. As with prevention work in schools and challenging young people’s misconceptions.”

Detective Chief Superintendent Sam Faulds, explained the collaborative work between Police Scotland and others regarding the policing response to reports of rape and serious sexual crime. DCS Faulds welcomed the increase in the reporting of both recent and non-recent sexual crimes, as well as the increase in detection rates for the police. However, she added that there is still room for improvement, saying that:

“On the policing response, it is really frustrating for us that we are never getting to the prevention stage. We need much earlier intervention through education and so on before reaching that stage."

Ronnie Renucci QC, Faculty of Advocates, echoed this view, telling the Committee that:

“There has been a sea change in the way that such cases are prosecuted when they get to court, as well as in the way that the police approach them proactively, certainly in relation to historical domestic violence and domestic sexual crimes.”

During the informal meetings, the Committee heard that there is a need to educate young people about domestic violence and to tackle intergenerational violence. A multi-agency approach, with robust oversight, was recommended.

Court delays

A key issue raised by a number of witnesses is the impact of COVID restrictions in further delaying criminal trials for sexual offences and domestic abuse.

Moira Price, Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service, told the Committee that the ability of the criminal justice system to progress criminal trials was significantly affected due to restrictions. Ms Price confirmed that there are currently 40,543 cases awaiting trial in the summary courts, which is a 132 per cent increase on the position immediately prior to the pandemic. This is despite priority being given to those cases involving domestic abuse, sexual offending and child witnesses.

Sandy Brindley, Rape Crisis Scotland, explained that survivors of sexual crimes were unable to safely access support during the pandemic, describing people phoning for help from cupboards or their cars. Ms Brindley confirmed that the biggest impact of COVID restrictions had been the uncertainty caused by court delays. However, she stressed that this only exacerbated an existing situation. Ms Brindley said that:

“Even before Covid, we had people waiting for two years or more for their case to come to court, which caused huge distress. The delays are much worse now because of Covid.”

Dr Marsha Scott told the Committee that the lockdown period was a difficult and dangerous time for victims of domestic abuse and that the significant delays to court proceedings caused women and girls to feel there was nowhere to turn for justice.

The work of the Scottish Government, court service, Faculty of Advocates and the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service to address the backlog of cases was commended by Ms Brindley. However, she stated that the impact of the uncertainty is causing huge distress and anxiety to survivors who “wake up every day thinking about what will happen”.

Improving the Management of Sexual Offence Cases

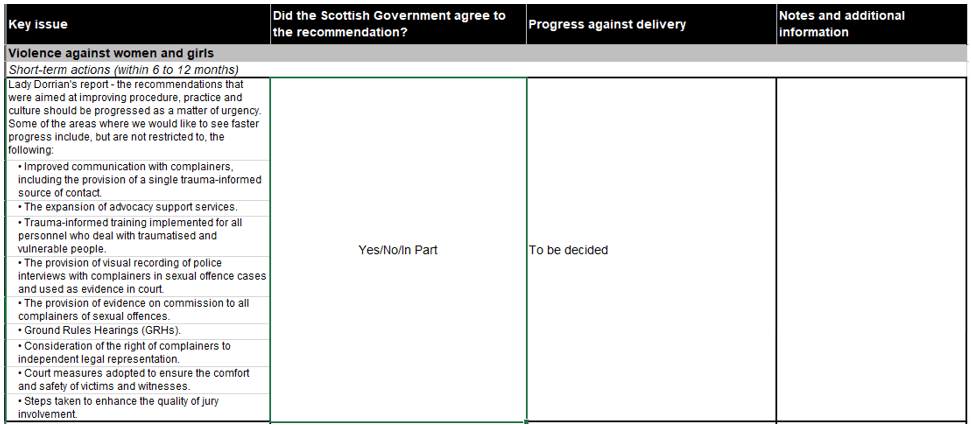

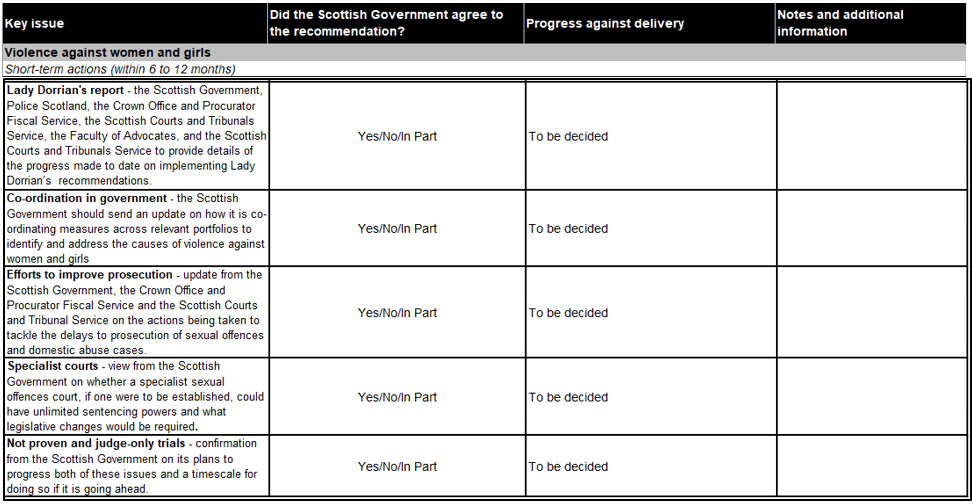

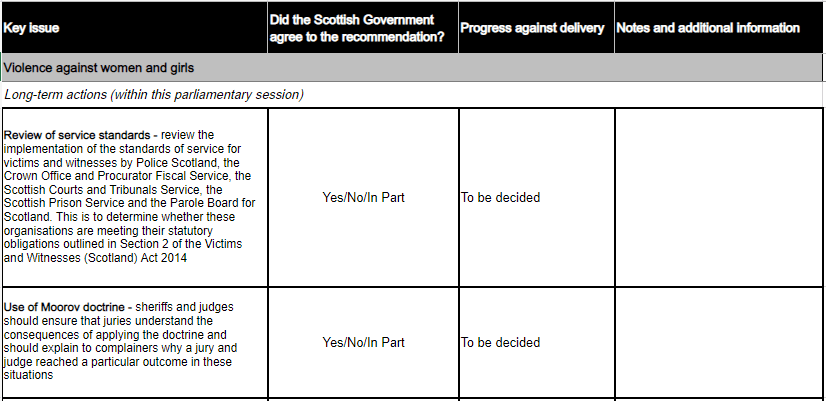

In March 2021, the Lord Justice Clerk, Lady Dorrian, published the findings of her review to develop proposals for an improved system to deal with serious sexual offence cases.[1] It focussed on those issues most relevant to the process of managing these cases within the Scottish Court system. Many of the areas recommended for improvement could be applied to both the prosecution of sexual offences and domestic abuse cases[1] Improving the Management of Sexual Offence Cases report.

Pre-recording of the Evidence and Case Management

Lady Dorrian concluded that the presentation of evidence by a complainer attending court many months, even years, after an alleged incident, is not conducive to the presentation of best evidence. Her report states that:

“Police interviews, written statements, attending court and giving live evidence in chief and in cross-examination were labour and time intensive, contributing to delay and the negative experience of complainers.”

Lady Dorrian recommends the increased use of commissions for taking evidence, with Ground Rules Hearings and improved judicial management, be implemented “as soon as possible”.

Sandy Brindley told the Committee that taking evidence on commission could have been a way to “mitigate some of the distress caused by the uncertainty of the pandemic”. However, this was not done due to a lack of availability of commissions. Ms Brindley said that:

“… some of the complainers we are supporting are being told that it would be quicker for them to give evidence in a live trial than to hold off for a commission. That is entirely unsatisfactory.”

During the informal meetings, the Committee heard about police statements about serious sexual assaults were taken from women who were in a traumatised state, that some women were not made aware of their entitlement to representation or support, and from some women that they were questioned for hours at a time without being offered a break. In some cases, the women were not allowed to see their statements to verify their accuracy until the day of the trial, which could be a number of years later. It was then too late to amend any errors.

The women survivors who spoke to the Committee supported the provision of evidence by commission, which they recommended should be offered to all survivors of sexual offences.

The provision of evidence by commission is issue is covered in greater detail in the section of this report on victims’ rights and victim support.

Providing a trauma-informed service

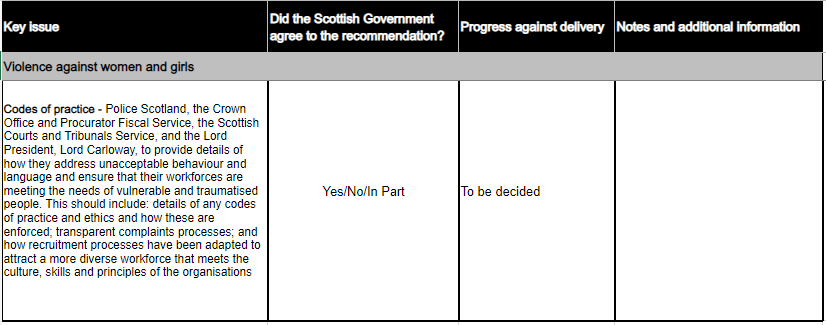

Lady Dorrian recommends that a number of steps be taken to ensure that the adoption of trauma-informed practices is a central way in which the experience of complainers can be improved. This includes one consistent trauma-informed source of contact from the outset and at relevant key stages of the process, revised procedures, trauma-informed training for all personnel in dealing with vulnerable witnesses, which includes examination techniques, and accredited courses approved by the Lord Justice General.

Lady Dorrian also recommends that practical arrangements for the making of statements or the giving of evidence should also be approved in the interest of the comfort and safety of complainers.

Moira Price explained to the Committee that the Crown Office takes a trauma-informed approach and seeks anonymous feedback from victims and witnesses, to learn lessons and improve the service they provide.

Rabia Roshan told the Committee that the criminal justice system needs to improve as it is letting down victims of violence and abuse, saying that:

“We see that when we speak to survivors on the front line and hear of the horrible experiences that they go through. After having had abuse perpetrated against them, they think that they can have full faith in the system, but they are really let down. In the aftermath of abuse, that is a retraumatising experience for them.”

Sandy Brindley described the current criminal justice system’s management of serious sexual assault cases as, “the antithesis of a trauma-informed `approach”.

During the informal meetings the Committee heard experiences where poor practice, a lack of communication, empathy, consideration and any explanation of the criminal justice process, made for an extremely distressing and retraumatising experience for survivors of sexual assaults and domestic abuse.

Some examples of poor practice include:

a statement being taken by a sole male, senior officer for a complaint of serous sexual assault;

lack of protection provided for victims and witnesses attending court,

no challenge to unacceptable behaviour and language by legal representatives within courts,

no throughcare or aftercare throughout the trial and beyond, and;

being told the verdict over the phone at which time they were not given any information about where to access support.

Independent legal representation

Lady Dorrian recommends that independent legal representation (ILR) should be made available to complainers, with appropriate public funding, in connection with section 275 applicationsi and any appeals therefrom. Complainers should have a right to appeal the decision in terms of section 74(2A)(b) of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995. Representation at any review further to limit the permissible evidence under section 275(9), should be at the judge’s discretion.

Dr Marsha Scott referred to a lack of “appropriate, affordable and geographically accessible legal services” for domestic abuse cases. Dr Scott told the Committee that:

“… victims tell us that some of their negative experiences after a conviction had to do with the fact that they had poor or non-existent legal representation or could not afford good legal services”.

During the informal meetings, the Committee heard about the lack of fairness in the criminal justice system. There is a defence lawyer appointed to represent the accused, there is an advocate appointed to put the case for the Crown, but there is no-one appointed to provide legal advice to victims. We heard that this gap in the system needs to be rectified.

Safety and wellbeing

The Committee heard concerns about the lack of consideration given to the safety and wellbeing of victims of sexual assaults and domestic abuse in the prosecution of these crimes.

Dr Marsha Scott raised a concern about “the extent to which convicted domestic abuse perpetrators are given community sentences”, and recommended more use of electronic monitoring to ensure the safety of women and children.

During the informal meetings, the Committee heard of practices which put victims in danger and made the criminal justice process a terrifying experience. This included coming face-to-face with the accused and their family in the court building, agreed special measures not being in place at their arrival at court, and not being informed when the perpetrator was released from prison.

The Committee also heard that the police service does not take stalking and harassing behaviour seriously enough, despite it being known to lead to worse behaviour, with the onus being incorrectly put on the victim to try to avoid the person.

A national, specialist sexual offences court

Lady Dorrian recommends that a national, specialist sexual offences court be created. Its procedures should be based on current High Court practice and revised to meet appropriate standards of trauma-informed practice. It would have sentencing powers of up to 10 years imprisonment.

Ronnie Renucci QC cautioned the Committee that the creation of a specialist court could have the unintended consequence of downgrading serious sexual offences by creating a two-tier system. Mr Renucci reasoned that if all cases of rape are prosecuted in the High Court, “they are all regarded with the same degree of seriousness”. However, if some cases are prosecuted in a lower court with inferior sentencing powers, “it cannot be anything other than a downgrading”.

Mr Renucci agreed that specialism is required in the prosecution of these crimes, but suggested that could be achieved through, “judges and from practitioners in the Crown and the defence being properly trained”. Mr Renucci said:

“However, that specialism can come from I think that a ticketing system is used in England, under which people must be trained and must have passed a test or met criteria to take such cases. That can be done, but the proper forum for any serious sexual offence is the High Court.”

Sandy Brindley agreed with Mr Renucci’s view that a hierarchical approach was not appropriate for the prosecution of serious sexual assaults but stated that the “way to address such concerns is to remove the 10-year sentencing limit that is proposed for the new court”. Ms Brindley added that much could be learned from the domestic abuse courts, in terms of approach.

Professor James Chalmers, regius professor of law at the University of Glasgow, agreed that the 10-year limit sentencing powers of the specialist court was not necessary. Professor Chalmers advised that to resolve this issue, “The [specialist] court would be presided over by High Court judges or by sheriffs who were considered appropriately qualified to sit in that court”.

Dr Marsha Scott spoke about the success of domestic abuse courts where, prior to the COVID pandemic, cases came to court in “about eight to ten weeks”. Dr Scott indicated that in the domestic abuse court legal professionals “had special training to prosecute domestic abuse cases and the sheriffs and judges had special training to understand the dynamics of domestic abuse”. She recommended this model, stating that it might also be a way to stop perpetrators from using the criminal justice system to prevent justice.

Judge only trials

In her report, Lady Dorrian referred to evidence from some judges where they found it difficult to understand the rationale for the acquittal verdict returned. This was particularly acute in the case of single complainer indictments, and even in cases with ample evidence of high quality. Lady Dorrian recommends that:

“Consideration should be given to developing a time-limited pilot of single judge rape trials to ascertain their effectiveness and how they are perceived by complainers, accused and lawyers, and to enable the issues to be assessed in a practical rather than a theoretical way. How such a pilot would be implemented, the cases and circumstances to which it would apply to and such other important matters should form part of that further consideration.”

The Committee heard conflicting views on whether judge only trials should be introduced for the prosecution of sexual offence cases. However, there was a consensus that criminal justice system personnel should receive trauma-informed training.

Sandy Brindley told the Committee that she was concerned about jury attitudes influencing their decisions in rape cases and that decisions are not based on evidence. Ms Brindley stated that one of the main reasons for low conviction rates is that no matter how much evidence there is: “Juries simply will not convict.” She stated that there needs to be meaningful engagement with the question of why juries are so reluctant to convict in rape cases.

Ms Brindley recommended that the Scottish Government and the Scottish Parliament consider models used in Europe where there are judge only trials in operation. This should include systems where there is a judge with lay assessors. This might provide an alternative system as:

“That means still having some form of citizen participation but ensuring that those citizens have had some training in how to assess evidence.”

Professor Michele Burman, University of Glasgow, described the use of judge only trials in South Africa to prosecute cases of rape and serous sexual assault. Professor Burman indicated that these trials have two community representatives present to provide informal advice to the judge.

Ronnie Renucci QC told the Committee he is not in favour of judge only trials. Mr Renucci questioned why entrusting all such important decisions to a very small group of judges is viewed as a preferable system. In relation to low conviction rates, he stated that he was “unaware of any research that has been conducted that shows that that would change the figures”.

Professor Chalmers referred to the anecdotal evidence from some of the judges who gave evidence to Lady Dorrian’s review, where they found it difficult to understand the rationale for some verdicts returned by juries.