Justice Committee

An Inquiry into the Use of Remand in Scotland

Executive Summary

When a person accused of an offence first appears in court, a decision will be made as to whether he or she can be released on bail or remanded into custody. During its inquiry into remand, the Committee heard that, while the use of remand is necessary in certain circumstances, remand levels in Scotland are high. Some evidence to the Committee questioned whether remand should be used so frequently, particularly given that a high proportion of those who are remanded do not go on to receive a custodial sentence.

However, the Committee also heard that judges do not refuse bail without good reason. Decisions as to whether to grant or refuse bail are made according to the framework set out in the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995. The use of remand is usually not the result of one single factor set out in the 1995 Act, but of multiple.

While some witnesses questioned the usefulness of routinely recording the reasons for the use of remand, the Committee believes that the reasons why judges decide to remand people in custody have to be better understood. Without improved knowledge and data, it is difficult to know which interventions or changes should be made to the current system. Currently, information is not recorded consistently or in a way that allows for any meaningful analysis of the reasons why remand is being used.

The Committee heard that the time people currently spend on remand is largely unproductive and potentially damaging for the individual and their family. Evidence suggested that a period on remand could lead to offending behaviour in the future. At present, few services are available to remand prisoners, such as education, and there is therefore little opportunity to engage in any rehabilitative activities. The Committee recognises that there are difficulties in providing support to remand prisoners – such as the short-time people usually spend on remand. However, it considers that more should be done to ensure that remand prisoners have their needs assessed and, where possible and appropriate, are offered support and the opportunity to engage in purposeful activity while in prison.

Particular concerns were raised about the negative effect of remand on an individual's physical and mental health. Other concerns were raised around information sharing between local authority health boards, the prison service, and other public bodies.

The Committee also heard that the negative consequences of a period on remand were exacerbated by the absence of support when remand prisoners are released. The difficulties remand prisoners may face on release are often the same as those faced by convicted prisoners. Particular concern was raised around housing and welfare benefits.

A number of witnesses also emphasised concerns about the use of remand in relation to women who, the Committee heard, are often particularly vulnerable.

The Committee explored whether greater availability of alternatives to remand, or additional support for people granted bail, could reduce the use of remand. Possible alternatives to remand include bail supervision, mentoring and other support in the community, and electronic monitoring. While overall there was broad support for the greater use of alternatives to remand, some witnesses questioned whether the availability of such alternatives would in fact have reduce remand levels.

The Committee also heard that reducing the use of remand, as well as improving outcomes for those prisoners who do have to be held in custody on remand, requires a solution that goes beyond the criminal justice system. Witnesses emphasised that many remand prisoners have “chaotic lives.”

The Committee notes that there are a number of factors which increase the likelihood of a person offending. The Committee further recognises that a large number of those in the criminal justice system may face issues in their lives that may increase the prospects of being placed on remand, and agrees with the evidence it heard that solutions to the high levels of use of remand often lie beyond the criminal justice system. In particular, the Committee considers that there should be greater and more consistent co-ordination between the prison service and housing providers to ensure that suitable accommodation is available for people leaving prison on remand, and that housing advice is available to all remand prisoners.

Introduction

On 16 January 2018, the Justice Committee held a round-table evidence session on the use of remand in Scotland. When a person is remanded in custody, it means that they will be detained in prison until a later date when their trial or sentencing hearing will take place.i During the round-table evidence session, the Committee heard views that too many people are remanded in custody. The Committee also heard that a period of remand can have a detrimental impact on an individual and their family, causing long-term disruption to housing, benefits, employment, relationships and healthcare, both mental and physical.

The Committee subsequently agreed to undertake an inquiry to explore these issues in more depth and to consider what steps could be taken to reduce the potential negative impact of remand.

Background to the Committee's inquiry

The legal framework

The Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995 sets out the rules that the court must follow when making decisions on bail.

In relation to the period prior to trial, section 22A of the 1995 Act provides that (during an accused person's first appearance) the court shall decide whether to release the accused on bail. If bail is refused, the accused is remanded in custody.

Section 23B(1) of the 1995 Act states that:

“Bail is to be granted to an accused person –

(a) except where –

(i) by reference to section 23C of this Act; and

(ii) having regard to the public interest, there is good reason for refusing bail;

(b) subject to section 23D of this Act.”

Section 23C(1) of the 1995 Act sets out grounds on which the court may determine that there is good reason for refusing bail:

“(a) any substantial risk that the person might if granted bail –

(i) abscond; or

(ii) fail to appear at a diet of the court as required;

(b) any substantial risk of the person committing further offences if granted bail;

(c) any substantial risk that the person might if granted bail –

(i) interfere with witnesses; or

(ii) otherwise obstruct the course of justice, in relation to himself or any other person;

(d) any other substantial factor which appears to the court to justify keeping the person in custody.”

Section 23C goes on to state that, in assessing the above grounds, the court must have regard to all material considerations. It provides a number of examples, including: the nature of the alleged offences; the probable disposal if the accused is convicted; and whether the accused was on bail when the offences are alleged to have been committed.

Section 23D of the 1995 Act provides that bail should only be granted in exceptional circumstances if the accused is being prosecuted under solemn procedure for:

a violent or sexual offence and has a previous conviction under solemn procedure for a violent or sexual offencei

a drug trafficking offence and has a previous conviction under solemn procedure for a drug trafficking offence.

The accused (or the accused's lawyer) and the prosecutor are entitled to address the court on the issue of bail. Whenever the court grants or refuses bail, it must state its reasons. Bail may be granted subject to standard or special conditions. Standard conditions include that the accused does not commit an offence while on bail, does not interfere with witnesses, and attends court for trial. Special conditions, for example, preventing the accused from contacting or approaching a particular person, can be imposed where the court considers that necessary. An accused may also be liberated without being made subject to bail conditions. Instead, the accused is simply ordered to appear at future court hearings.ii

The length of time a person may spend remanded in custody is generally constrained by time limits on dealing with cases. For example, where an accused is remanded in custody prior to trial:

summary procedure – the trial should normally commence within 40 days (section 147 of the 1995 Act)

solemn procedure – the trial should normally commence within 140 days (section 65 of the 1995 Act)

Statistics on the use of remand

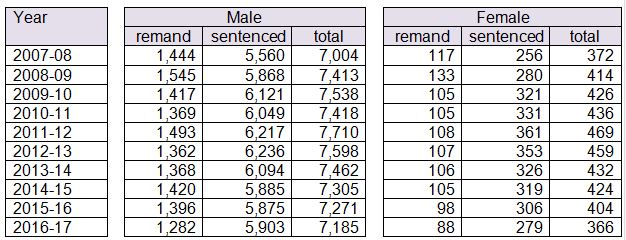

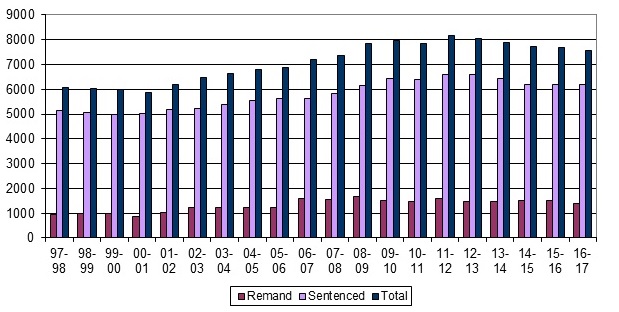

Figure 1 below indicates how the average daily prison population has changed over the last 20 years. As well as showing the total population, it includes a breakdown into remand and sentenced prisoners.

Table 1 provides figures for the last ten years, which are further broken down into male and female prisoners.

Table 1: Average Daily Population by Type of Custody, 2007-08 to 2016-17 As for Figure 1 with additional figures (breakdown into male and female) provided by Scottish Government officials using Scottish Prison Service management information.

Information provided by the Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service showed that 71.1% of accused remanded in solemn proceedings in Sheriff Courts (2014-17) received a custodial sentence. 42.82% of accused remanded in summary proceedings over the same period were given a sentence of detention.

Policy debate on the use of remand

Over the years, the work of a number of expert groups has included consideration of the use of remand. For example, the 2008 report of the Scottish Prisons Commission (chaired by Henry McLeish) noted—

Sometimes people are remanded in custody because that is the only safe thing to do, but often remands are the result of lack of information or lack of services in the community to support people on bail. If judges are to avoid these unnecessary and costly remands they will need nationwide speedy access to information during bail hearings, and they need a wider range of bail options nationwide. These options should include community-based bail accommodation and, where it is necessary, tags and curfews on offenders in their own homes or in specialist bail accommodation. (para 3.15)

A report in 2012 by the Commission on Women Offenders (chaired by Dame Elish Angiolini) stated that a—

… high level of remand prisoners contributes significantly to overcrowding, which means staff are overwhelmed with managing crisis situations. It is a barrier to effective rehabilitation for those serving prison sentences, which makes it more likely that offending behaviour will continue on release, and it is also costly. Women offenders who are accused of committing serious crimes or who thwart the administration of justice should expect to have their liberty curtailed pending disposal of their case. But, analysis of prison data shows that 70 per cent of women who are remanded in custody do not ultimately receive a custodial sentence. So, there is clearly scope to develop meaningful and robust alternatives to remand. (paras 135-136)

The 2012 report of the Commission on Women Offenders included recommendations for encouraging the use of alternatives to remand:

to make bail supervision available across the country – with mentoring, supported accommodation and access to community justice centres for women

to further examine the potential of electronic monitoring as a condition of bail

to improve awareness of alternatives to remand among those dealing with (alleged) offenders

Later the same year, the Scottish Government published a written response to the report of the Commission on Women Offenders. It accepted all three of the above recommendations on alternatives to remand.

The 2016-17 annual report of HM Chief Inspector of Prisons for Scotland highlighted concerns about some categories of prisoner, including remand prisoners, being subject to a restricted prison regime—

IPMs [Independent Prison Monitors] continue to note concerns about the different levels of access to and engagement in activities available in prisons for different groups of prisoners. In particular, women (where they make up a small proportion of the population), young people, those held under protection regimes and remand prisoners often do not have equity of access to purposeful activity, time out of cell and other interventions and services. (p 18)

The report of the former Justice Committee on its Inquiry into Purposeful Activity in Prisons (2013) noted that—

The 2011 Prison Rules state that remand prisoners are not required to work and, as a result, they can spend long periods of time without anything to do. A large number of submissions, especially those from visiting committees, identify this as an issue and argue that it should be addressed as remand prisoners have not been found guilty and are not, therefore, in prison being ‘punished’. This was also an issue which members explored during their visits to prisons.

Members have been concerned that some remand prisoners are discouraged from participating in case it is seen as an admission of guilt.

During members’ visit to HMP Edinburgh, they were told that remand prisoners tend not to have much interest in participating in purposeful activities as their first few weeks in custody are usually spent stabilising their addictions and setting into the prison regime.

The Committee notes the concerns raised by a number of stakeholders relating to the opportunities remand prisoners have to participate in purposeful activities. The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government and SPS give this matter focused consideration when drafting the strategy on purposeful activity.(paras 151-154)

In relation to the above recommendation, a joint response from the Scottish Government and Scottish Prison Service (2013) stated—

The SPS accepts this recommendation and will include a review of the opportunities available for remand prisoners in its strategy for purposeful activity. (p 14)

Information on the views and experiences of remand prisoners, taken from the 2015 prisoner survey, is set out in the Scottish Prison Service’s survey bulletin Remand Prisoners 2015 (2016). The survey asked questions about a number of issues, but most relevant to this report were the following:

64% rated their quality of healthcare in their prison as “very good”, “good”, or “ok”

25% worried alcohol would be a problem for them on release

39% had used illegal drugs in prison

53% reported their drug use had changed during their current period in prison:

62% - drug use had decreased

20% - drug use had increased

10% - same use but different drugs

8% - started using in prison

Remand prisoners had regular contact with their friends and family by letter (64%), visits (49%) and telephone (67%). Convicted prisoners were 10% more likely to have contact by telephone and visits.

Work of the Committee

The Committee’s work on remand started with a round-table evidence session on 16 January 2018 when it heard from the following:

Anthony McGeehan, Procurator Fiscal, Policy and Engagement, Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service;

David Strang, HM Chief Inspector of Prisons for Scotland;

Teresa Medhurst, Director of Strategy and Innovation, Scottish Prison Service; and

Anne Pinkman, Convenor, Scottish Working Group on Women's Offending.

Following that session, the Committee agreed to take further evidence to explore issues in more depth, leading to the following five evidence sessions:

6 February 2018 - Karyn McCluskey, Chief Executive, and Keith Gardner, Head of Improvement, Community Justice Scotland; Thomas Jackson, Head of Community Justice, Glasgow City Council, representing the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities; Tom Halpin, Chief Executive, Safeguarding Communities – Reducing Offending; and Kathryn Lindsay, Chief Social Work Officer, Member of Social Work Scotland.

13 March 2018 - Sheriff Gordon Liddle, President, Sheriffs' Association; Leanne McQuillan, President, Edinburgh Bar Association; Gillian Mawdsley, Policy Executive, Law Society of Scotland; and Professor Neil Hutton, University of Strathclyde.

20 March 2018 - Marie Cairns, Family Visitor Centre Manager, CrossReach; Neil Clark, Project Co-ordinator, HMP Kilmarnock Mental Health Advocacy Service, representing East Ayrshire Advocacy Services; Elaine Stalker, Deputy Chief Executive, Families Outside; and Colin McConnell, Chief Executive, Scottish Prison Service.

27 March 2018 - Alan Staff, Chief Executive, Apex Scotland; Rhona Hunter, Chief Executive, Circle Scotland; Fiona Mackinnon, Partnership Manager, Shine; Kathryn Baker, Chief Executive, Tayside Council on Alcohol; and Kirstin Abercrombie, Service Manager, Glasgow Women's Supported Bail Service, Turning Point Scotland.

24 April 2018 - Michael Matheson, Cabinet Secretary for Justice, Scottish Government.

The Committee also sought written evidence from targeted stakeholders, receiving 27 submissions. The Committee wrote to all local authorities in Scotland seeking information on the availability of services to support the use of bail, as well as the availability of support to mitigate the possible negative effects of remand on both prisoners and their families. 15 responses were received. Details of all these submissions and responses can be found in the Annexes to this report.

The Committee would like to thank all those who submitted written evidence and gave oral evidence during the course of its inquiry into remand. The Committee would also like to thank Circle (an Edinburgh-based charity providing support to families, including those affected by imprisonment) for hosting a visit where Members heard more about Circle’s work with remand prisoners and their families.

Key Issues

Use of remand

At the end of 2017, there were 7,334 people detained in Scotland’s prisons, 6,971 males and 363 females. People on remand account for just under a fifth (18.5%) of the male prison population and a nearly a quarter (22.9%) of the female prison population. The following table from HM Chief Inspector of Prisons for Scotland shows the number of prisoners held on remand as a percentage of the total prison population since the year 2000.i

Table 2: number of prisoners held on remand Year Number in pre-trial/remand imprisonment % of total prison population Pre-trial/remand population rate per 100k of the population 2000 951 16.2% 19 2005 1,175 17.3% 23 2010 1,441 18.3% 28 2017 1,370 18.7% 25 HM Chief Inspector of Prisons for Scotland, Written Submission

The overwhelming view of witnesses was that, while the use of remand is necessary in certain circumstances, it is currently used too frequently.

There were a number of reasons for witnesses holding this view. In his written submission to the Committee, David Strang, Her Majesty's Chief Inspector of Prisons for Scotland, wrote “In some cases it appears that remand is used as a heavy-handed way to ensure that the accused attends court for their trial.”i In oral evidence, he told the Committee—

Remand is perfectly legitimate as long as there are good grounds for it and the decision is not arbitrary…those bars are quite high…I think that remand in prison before trial is used too frequently when there is, perhaps, a minor fear of someone not turning up at court or of them reoffending. The only option seems to be to remand them in custody until trial and I would encourage society and Parliament to consider other ways of ensuring that people attend court for their trial.iii

Kirstin Abercrombie, service manager for Glasgow women's supported bail service at Turning Point Scotland, agreed saying—

At the minute, it seems that we are overusing remand and using it as a fail-safe means of getting people to turn up to court. However, there are many other ways in which we can help people to turn up to court…Even general practice and dental practice surgeries send a text message to remind people before their appointments, so we can start with simple things like that…We are talking about people who have multiple and complex needs, so it is realistic to think that they might struggle to get to court, but that does not mean that we should not help them to get there.iv

Fiona Mackinnon of Shine Women's Mentoring Service also highlighted the need to support individuals to turn up to court, and the potential use of text reminders to do so—

Often it is not a conscious choice not to appear in court—they just do not remember. [At Kilmarnock sheriff court] we set up a system…in which the staff would text the women to say, “Remember you have court tomorrow. If you have any problems turning up, let me know.” At the time that I was involved, that simple measure was having real success in getting people to turn up at court.v

Text alerts have been used to remind witnesses to attend court since 2012. The use of text alerts was expanded earlier this year to notify witnesses when their attendance was no longer required.vi

Other evidence highlighted that a high proportion of those who are remanded do not go on to receive a custodial sentence. In particular, as was noted above, the 2012 report by the Commission on Women Offenders highlighted that only 30% of women remanded in custody go on to receive a custodial sentence. Witnesses also emphasised that a period on remand could have a detrimental impact for an individual and their families, and viewed the negative consequences of remand as a key reason in favour of reducing the remand population. The impact of a period on remand, including the specific issues raised by women, children and young people and families, is discussed further below.

On the other hand, other evidence to the Committee argued that judges do not refuse bail without good reason.

Leanne McQuillan of the Edinburgh Bar Association told the Committee that—

Generally, when sheriffs remand in custody they justify it fairly well and it is difficult to point to an error… Sheriffs are good at justifying why they remand people, and I honestly do not think that they remand people lightly.vii

As discussed earlier in this report, decisions as to whether to grant or refuse bail are made by the court according to the framework set out in the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995. Grounds for refusing bail include any substantial risk that the person might if granted bail:

abscond;

fail to appear at court as required;

commit further offences;

interfere with witnesses or otherwise obstruct the course of justice, or

any other substantial factor which appears to the court to justify keeping the person in custody.

A court must also consider “all material considerations” including the nature of the offence, the probable disposal of the case if the person were convicted, whether the person was subject to a bail order, when the offences took place, the character and past behaviour of the person, any previous behaviour or breaching of court order, and the associations and community ties of the person.

In his evidence to the Committee, Sheriff Liddle of the Sheriffs' Association said—

On each and every occasion when bail is applied for, that is the checklist that we go through in considering whether someone should be admitted to bail…but as part of the equation we have to take into account personal circumstances, and those are all different…x

He added that to reduce the use of remand would require, in his opinion, looking at amending the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) 1995 Act.xi

He went on to emphasise that judges are not eager to remand people, and that it can be a difficult balancing act to consider all the factors involved in an individual case.xii

The Committee has heard considerable evidence that the use of remand is usually not the result of one single factor set out in the 1995 Act, but of multiple. Professor Neil Hutton said—

Very frequently, judges give more than one reason. One of the difficulties is that, often, bail is not granted for a number of reasons at the same time. Often the people concerned are those who have significant records and have failed to comply with court orders before, who have no fixed abode, who have breached bail, and who have chaotic lifestyles. That is true not of all of them, but of a significant number. It is difficult to know exactly why bail was not granted, or whether it was not granted for one reason or another—it tends to be for multiple reasons.xiii

The Justice Secretary told the Committee—

Bail decisions are rightly a matter for the courts, and they are made within the legal framework that this Parliament put in place back in 2007. However, I am keen to address issues relating to the inappropriate use of remand in Scotland, by working together with partners and stakeholders to consider what can be done to reduce the use of remand, where it is safe and appropriate to do so.xiv

Data on the reasons for remand

Given the concerns expressed by the majority of witnesses about the high levels of remand prisoners, the Committee probed whether any data is available on the reasons bail is refused by the courts. However, while reasons are given orally by the court when granting or refusing bail, it appears that these reasons are not recorded or collected in a way that allows for meaningful analysis.

Anthony McGeehan of the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service said—

I am not aware of any data being kept on the reasons for the use of remand…The court is obliged by statute to articulate why an individual is being put on remand. I presume that the sheriff or the court will record the reasons for that decision, but I am not aware of any data being captured or any data set that would allow us to understand why individuals had been remanded or, in a systemic way, to understand the profile of reasons for remand among the current prison population.i

The Sheriffs’ Association outlined the information given and recorded in court—

…written reasons for refusal of bail are provided if an appeal is taken... [Court] minutes are of large variety. They are short, seldom occupying a full A4 page…The minutes are not a written record of reasons given in court for a decision or disposal. Those reasons are provided orally in open court to those who have an interest in the proceedings, namely the accused/offender, his/her solicitor and the prosecutor.ii

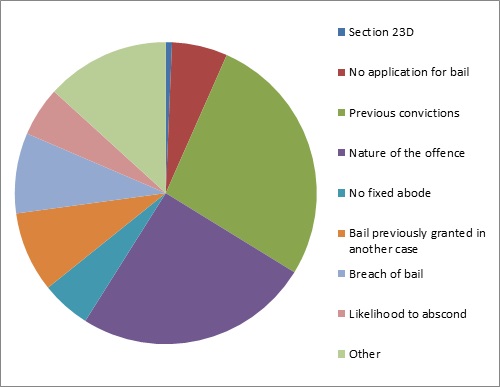

Some insight into the reasons for bail was provided by Professor Hutton, on the basis of a small-scale study he had undertaken of 60 cases in a Scottish Sheriff Court in August 2016. Sheriffs were asked to record reasons for summary sheriff court refusal of bail decisions. They were not restricted to the number of reasons which they could list. The reasons for refusing bail were recorded as follows in Figure 2:

Figure 2: Reasons for refusing bail, Professor Hutton study of 60 Scottish Sheriff Court cases, 2016  From data in Professor Hutton’s Written Submission

From data in Professor Hutton’s Written Submission

Professor Hutton explained, “In five cases a single reason was given for remand. Three of these were no fixed abode, one public safety and one likelihood to abscond. In all other cases multiple reasons were noted (between 2-5).”iii

He continued—

As judges were allowed to give multiple reasons it is difficult to measure the effect of any particular reason. In well over half of all the cases, previous convictions and the nature of the offence (presumably the seriousness of the offence) were the two most common reasons for remand. This is in line with international research which shows that these factors are the two best predictors of custodial sentences.iii

The study also showed that having breached, or being considered likely to breach a court order was another significant reason for remand. Professor Hutton added—

The data shows that a significant proportion of reasons given for remanding offenders in custody relate to their history of involvement in the criminal justice system … Offenders are rarely remanded solely because of the seriousness of the offence or because they present a danger to the community.iii

Karyn McCluskey from Community Justice Scotland mentioned that a form was used in Edinburgh Sheriff Court to capture reasons for deciding whether to remand an individual—

When I was at the court on Monday, I picked up a procurator fiscal form. It is a report by a sheriff and a bail application, and it goes through criteria—yes or no—about why they are granting or refusing bail. I do not know where that form is kept or whether it is always filled in, but it would be useful to start to look at it.vi

However, some witnesses questioned the usefulness of routinely recording the reasons for the use of remand. For example, Sherriff Liddle told the Committee that any additional capturing of data would cause a demand on the resources of the court—

I would not want to be responsible for suggesting that more pressure is placed on clerks to write more and more into the minute each time that a case calls in court. Frankly, that would take up a lot of time and would have a resource implication.vii

He continued—

I can feel that there is an appetite for a written record and perhaps that is because data is something that is looked on as being important, but I cannot see that we would find it very useful when it comes to the question of bail.viii

Professor Hutton also questioned the benefits of additional data collection, saying that—

Asking judges to record their reasons for granting bail, and collecting that data, suggests that there is a feeling that the judges are not making proper decisions, or that they are making decisions without justifying them properly. The little research pilot study that I mentioned would suggest that judges can find plenty of reasons under the 1995 act for remanding people in custody. I do not think that they do it lightly; they try to keep people out of custody as best they can. Given that there are multiple reasons, there would be no problem in judges finding many reasons to justify not granting bail. I am not sure what would be gained by having those reasons given more publicly.ix

The Justice Secretary also had concerns over the purpose of capturing additional data, saying—

Would it deliver greater consistency [in decisions]? I am not sure that it would. Very often, sentencing decisions around bail and remand are individualised. They depend on an individual’s circumstances and history, so it would be difficult to create a data collection system that would allow us to make that direct comparison.x

A similar point was made by Sheriff Liddle, who told the Committee that an individual’s circumstances are taken into account at the point of deciding whether to remand in custody.viii

Several witnesses were asked whether the data available could show an individual who was remanded multiple times, creating an artificial inflation of remand figures in terms of individuals. However, the information is not available; as Keith Gardner of Community Justice Scotland told the Committee, “we do not know whether it is the same individuals we are remanding time and time again.”vi Anthony McGeehan also highlighted the unavailability of data, suggesting additional information may assist in understanding the remand population—

The reasons for remand in the prison population as currently described are unknown. That data is not available at present, although it would be useful in understanding whether the particular considerations that were prominent in the minds of decision makers were, for example, the protection of the public, the administration of justice or a combination of factors and whether those factors could be appropriately addressed through measures such as bail supervision, electronic monitoring, mentoring or other alternatives to remand.xiii

Remanding someone in custody can be necessary and legitimate, and the Committee heard that judges consider all factors and information when making decisions. However, the Committee is of the view that figures for the number of people being held on remand in Scotland appear to be high. The Committee believes that, to make any difference in the numbers, the reasons why judges decide to remand people in custody have to be better understood. Without improved knowledge and data, it is difficult to know which interventions or changes should be made to the current system. Information is not recorded consistently or in a way that allows for any meaningful analysis of the reasons why remand is being used.

Remand should always be used where necessary for public safety. Of particular concern however to the Committee is the question as to whether remand is being overused as a way of ensuring attendance at court. The Committee notes that a substantial risk that an accused may fail to appear at court is, in terms of the legislation, a legitimate reason for refusing bail.

A failure to attend court can, rightly, often have severe consequences for an individual. Therefore, steps should be taken to reduce such occasions to a minimum in order to avoid putting someone on remand with all the costs involved to the public sector and the detrimental impact such a decision can have for the individual.

During the inquiry, the Committee heard from several witnesses arguing that, for example, sending text reminders of court dates could help ensure those characterised as having “chaotic lifestyles” attend court. The Committee considers that further steps could be taken to improve the way the courts keep in touch with those that are required to attend hearings. The Committee notes that text alerts are already used to remind witnesses to attend court, or to notify them that their attendance is no longer required. The Committee considers that a similar system could be piloted in one or more courts for accused, to see if this would be effective in ensuring people attend court and therefore potentially reduce the use of remand for that reason.

While some data on remand is collected by the courts, the Committee believes that there is a need for more and better quality information to be recorded consistently so that it can be effectively analysed and compared at a national level. The Committee heard that this information may be captured already in some courts through the use of a form which records the reasons why bail has been granted or refused. The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government work with the Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service to investigate options for capturing data in a systemic manner, such as the use of a pro forma, on the reasons for granting or refusing bail.

One of the issues raised by the Committee was whether remand rates are artificially high because they include figures for a single person being remanded multiple times, or whether different people are being remanded. The evidence to the Committee was not able to answer this point, as such information does not appear to be captured or collected in any systematic way. The Committee recommends the Scottish Government work with the Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service to separate information on the number of individuals on remand from the overall remand figures and ascertain the true number of those who have experienced time on remand.

The impact of a period on remand

One of the key arguments against the current levels of use of remand was the negative impact that time spent on remand could have for an accused. Witnesses emphasised the limited opportunities available to people on remand while in prison, as well as the absence of support on release. Particular concerns were raised about women and young people remanded in custody. Evidence also highlighted that a period in remand frequently has negative consequences for the individual accused, and also for any children and their wider family.

Experience of remand prisoners

The Committee has heard that time on remand is often unproductive for prisoners. As remand prisoners are not convicted, they have a different status in the prison population. With little access to services, no requirement to work, and the need to be separated from the convicted prison population (who have priority of services),i the Committee heard that a period on remand is essentially wasted time and can do more harm than good.

The Scottish Prison Service's most recent figures for median length of time on remand date from 2012-13 and were 25 days for menii and 22 days for women. However, in evidence to the Committee Teresa Medhurst said that over a three month period in 2017, the average length was 26iii days for women.

Elaine Stalker, deputy chief executive of Families Outside, said—

Remand is particularly difficult. It can be a very short time in prison—by the time someone is back in court, they are out again. There is not enough time for anyone to do anything with people who are on remand, or for families to find things out and start engaging. Those things usually happen when a custodial sentence is given.iv

This was echoed by David Strang, HMIPS, who said—

Being locked up on remand has the same disadvantages as a short prison sentence has...Very little happens for someone who is on remand. They do not have to work, so they do not do so. They must be kept separate from convicted prisoners, so in general they will spend a long period of their day locked in their cell. It is a very unproductive time, and it is disruptive and damaging to other aspects of their life… because of the shortness of the time when they are in custody and the unpredictability of that, they tend not to get on to courses or programmes. Some medical procedures are not available to them. … In general, the regime for people on remand brings reduced opportunities for activity, education and work.v

He went on to say—

My background in the criminal justice system suggests to me that a short period in custody is likely to lead to more rather than less offending; it does not provide a moment of inspiration in which people suddenly realise that their lives have been on the wrong track and that they now have to change. Instead, it is disorientating, unsettling and stressful. Whether or not they are guilty, people can be traumatised and feel a sense of shame and guilt. It is not a constructive time during which they learn some new skill. Once people get into the criminal justice system and go through the process, they leave prison, reoffend and go back in.vi

The Justice Secretary agreed that remand is damaging for individuals, saying “It is clear to me that remand is just as disruptive as short prison sentences. It impacts on families and communities and it adversely affects employment opportunities and stable housing—the very things that evidence shows support desistance from offending.”vii However, he added—

In reality, there is limited opportunity to undertake work in prison with someone who has not been convicted and who is in prison for a very short time—at that stage the period could be undefined, depending on the progress that has been made on the individual case. The timeframe makes it hard for the Prison Service to deploy significant resource to be able to provide the individual with additional input.viii

The Committee also heard views that the level of churn of remand prisoners also presented challenges. Colin McConnell, Chief Executive of the Scottish Prison Service told the Committee—

There is a difference between stock and churn …For the remand population, the stock is about 17 per cent of the people living in a prison on any given day, but the actual churn is about 50 per cent. About 50 per cent of the throughput of the prison through reception is driven by those on remand, although the day-to-day stock is about 17 per cent.

When you factor in the 27 days median point, you begin to get a sense of the scale of the challenge in trying to join all those dots—to make all those connections—for the thousands of people who are passing in and out of our receptions for very short periods of time, many of whom are passing into our care having spent years living a chaotic lifestyle.ix

On the other hand, some evidence suggested that a time in prison on remand can bring some benefits. Colin McConnell of the Scottish Prison told the Committee “many people who make their way into custody, particularly those who, regrettably, are on a treadmill and those who spend very short periods of time with us, have chaotic lifestyles in the community.” He went on to add that “It is almost a perverse aspect of custody that it can bring stability and access to services and resources that may not be available to the individual when they are in the community.”x

He continued—

I understand the committee's concerns about the reasons for remand or its potential overuse…However, perversely, there are positives that individuals can experience by being sent into custody, particularly those who have had chaotic lifestyles up to that point, and there are some good outcomes from that.x

The chaotic nature of some women's lifestyles means that they may consider prison a safe place. This was picked up by Fiona Mackinnon of Shine Women's Mentoring Service who said—

…when I was in court in my previous job, the sheriffs told me that women have asked to go to prison because they feel so hopeless. They feel that there is nothing for them in the community, so sheriffs can feel that there is no alternative to a sentence or to them being remanded in custody.xii

However, in this case a prison stay was not seen as a positive route for the women, and Fiona Mackinnon spoke of having to convince them that there were routes to services and support other than being remanded in custody.

The Committee heard that the time people currently spend on remand is largely unproductive and potentially damaging, and could lead to offending behaviour in the future. At present, few services are available to remand prisoners, such as education, and there is therefore little opportunity to engage in any rehabilitative activities. The Committee heard that there are a number of reasons for this. For example, the short time that a person spends on remand can make it difficult in practice for them to engage in any courses or other activities offered in the prison. Such difficulties can be exacerbated by the sheer churn of remand prisoners through the prison system. Further, there are statutory obligations which require services to be provided to longer-term convicted prisoners which can limit the resources available for remand prisoners. The Committee also heard that remand prisoners could sometimes be reluctant to engage with services or other opportunities in prison because they consider this may be taken as an admission of guilt.

While the Committee recognises these difficulties, it considers that more should be done to ensure that remand prisoners have their needs assessed and, where possible and appropriate, are offered support and the opportunity to engage in purposeful activity while in prison. The Committee will return to this issue as part of this year’s budget scrutiny.

Health

Particular concerns were raised about the negative effect of remand on an individual's physical and mental health. The Committee heard that those remanded in custody may face barriers to obtaining their medication, or continuing services they may have accessed in the community (such as drug or mental health treatment). Community health records may not follow them into prison, and delays or breaks in treatment can result.

Colin McConnell (SPS) told the Committee that following conviction or a decision to remand and individual, he or she then sees a qualified nurse on reception and a doctor within 24 hours. However, particular issues around access to medication while on remand were raised by other witnesses, following evidence in a session with the Scottish Prison Service that medication was routinely removed from prisoners on their entry into prison.i

Marie Cairns, Family Visitor Centre Manager at Polmont Young Offenders Institute, spoke of the impact this uncertainty around health and medication can create for families, saying, “some families have told us that they are extremely concerned about a family member in prison because the person cannot articulate their problems to the medical services.”ii

Other concerns were raised around information sharing between local authority health boards, the prison service, and other public bodies. Marie Cairns suggested more could be done to share existing information—

I was really shocked when I came to work at HM Young Offenders Institution Polmont when I realised that all the care plans that are made while a person is in residential care are not transferred over to the prison. That is a massive amount of information regarding that person. Obviously data-sharing issues and relevant legislation would need to be considered before the information is passed on, but they are missing out on such a wealth of information. It can help SPS staff to know the triggers for somebody who may be going to self-harm or to know the medications. There is a wealth of knowledge in those care plans that I feel would be a great advantage to SPS staff.iii

Colin McConnell said there was, “a communication issue for the NHS. The issue of communication between health boards and the prisons in their jurisdictions has to be addressed.”iv The Justice Secretary agreed that “It is fair to say that some health boards are better than others.”v He elaborated—

My health minister colleagues are looking at an area of work on the back of the Health and Sport Committee's report on healthcare provision within the prison estate. They are looking at some of the measures that need to be taken to improve the consistency with which healthcare is being provided…For example, the health board in my constituency, NHS Forth Valley, has to cover three prisons—Polmont young offenders institution, Cornton Vale and Glenochil. By and large, it delivers a very good service and is very attuned to and works in close partnership with the SPS. In other parts of the country we need to refine that process and make it work better.vi

The Committee also heard that barriers to sharing information arose for a number of different reasons, including the incompatibility of different systems across the prison service and the NHS. Colin McConnell told the Committee—

There are information-sharing blockages that are related to particular permissions that are not allowed to be given across organisations without the individual giving their say so. Without doubt, there are system and process issues that simply get in the way because systems are incompatible. That is not beyond us to resolve, but it is a huge challenge for us.vii

When these issues were raised with the Justice Secretary, he responded—

Before 2011, Scottish Prison Service nurses and medical staff would have had difficulty accessing NHS medical data because of data protection rules. NHS staff are now working within the prison estate and they can access NHS information as required. Part of the challenge will be having computer systems within the SPS that gives it access to NHS data.

Some of the wider data issues are being considered by the health and justice collaboration improvement board. That strategic work needs to be taken forward. We are looking at where there are barriers or blockages, whatever they might be, and, if the solution is an IT solution, whether we can take a more strategic approach.

I would prefer to avoid a situation in which our prison establishments in different health board areas all have to have different fixes so that they can access the appropriate NHS information. It would be good to do this once for Scotland so that the Scottish Prison Service could have a system that allows it to access appropriate medical records as and when that is necessary within a prison establishment, no matter where it is in the country.

That is my view from the justice perspective. I am conscious that there are differences between health boards in respect of their ability to access and share information. I do not kid myself on that it is an easy problem to resolve. That is why we have brought together a new body that includes some of the key leaders in justice and health to deal with some of the more strategic issues. Part of that is about IT and data sharing and putting in place appropriate protocols and systems that can help to facilitate that.viii

Mental health

Anne Pinkman of the Scottish Working Group on Women's Offending told the Committee that, “Too often, prison is used as an alternative to a mental health facility.”i People can end up being remanded because they are perceived to be a danger to themselves (or others) due to a mental health issue.

The Committee also heard about the detrimental effect of imprisonment on mental health. In its written submission, East Ayrshire Advocacy Service highlighted a period of remand can cause further damage to someone suffering from poor mental health, and many witnesses supported this.

In evidence to the Committee, Neil Clark of East Ayrshire Advocacy Services elaborated on a particular preventable cause of mental health issues in prison, related to the removal of medication from prisoners, including mental health medication—

If their medication is removed, they can experience a delay in receiving medication, which can have quite a negative impact on their mental health. Some people have been on certain mental health medications for a number of years, but for whatever reason those medications are not available in the prison. There might be security concerns or a risk that they will be bullied for their medication. There is a lot of concern from prison management and healthcare staff about that, but delaying medication can have quite a negative impact on people who have a genuine need for it…

When I have raised such cases with healthcare staff, I have been told that they do not want to set up a treatment plan if someone is only going to be in prison for a couple of weeks, as they might not follow that treatment plan if they go back into the community. That is their concern. However, we have worked with some people who have been on remand for a number of months and have gone with no medication and no treatment, although they have taken medication and undergone treatment in the community. There is definitely a gap in provision for people on remand.ii

Colin McConnell of the SPS responded to this point, saying—

it is for qualified medical people to deal with an individual's medical care and, in particular, any prescription drugs. As the committee already knows, following conviction or a decision to remand, everyone sees a qualified nurse on reception and a doctor within 24 hours.iii

The Committee heard anecdotal evidence from some witnesses that remand prisoners could have their medication removed while waiting to be assessed by prison-based NHS staff. Witnesses told of the impact that this can have on the individual, who may go some time without their required medication, and also on their families who worry about the family member being without a prescription. The Committee also heard that treatment providers may be reluctant to create a plan or programme for a remand prisoner who may not remain in prison long enough to complete it.

The Committee asks the Scottish Government, NHS Scotland and the Scottish Prison Service to respond to these concerns. The Committee considers that procedures should be in place to ensure that, where appropriate, remand prisoners retain access to prescribed medication, and also have continued access to other treatment (such as mental health support) that they have been receiving in the community.

The Committee also heard that communication between local health boards and the prison service varies by area, in effect creating a post-code lottery which could have an impact on the provision of medication to prisoners on remand. The Committee welcomes the indication from the Cabinet Secretary for Justice that steps are being taken to address barriers to information-sharing between prisons and health boards. The Committee considers that solutions to improve information-sharing, including any necessary IT systems or protocols, are implemented as a matter of priority. The Committee asks the Scottish Government to provide full details for the work being undertaken and timescales for its completion.

Release from remand

The Committee also heard that the negative consequences of a period on remand were exacerbated by the absence of support when remand prisoners are released. As Anne Pinkman told the Committee, “There is no statutory obligation on any service that I am aware of to provide services to individuals who are liberated from remand.”i

The difficulties remand prisoners may face on release are often the same as those faced by convicted prisoners. Particular concern was raised around housing and welfare benefits, and access to support to prevent re-offending.

The Committee heard of the benefits of through-care support to convicted prisoners. Through-care is currently available to adult prisoners serving a sentence of less than four years and not subject to statutory order. Support is provided prior to leaving prison, and for up to a year in the community.ii The Justice Secretary said that through-care officers have “transformed how the Prison Service supports people as they move out of prison. Sometimes that involves supporting individuals who have been on remand, where appropriate, for two to three months after they have moved into the community.”iii

Colin McConnell (SPS) told the Committee—

…we are expanding [through-care support] to those who are sent to us on remand, where they want it. It is not a compulsory service; it is provided where people want help. We are linking with other organisations and agencies that pass through the boundary between prisons and the community to try as best we can to provide wrap-around services for people who pass in and out of the custody continuum—for some people, that is what it is.iv

However, Elaine Stalker of Families Outside argued that more can be done for remand prisoners, particularly in regard to housing issues—

We certainly know that the through-care officers who are allocated to people in prison…will help those people, including young people and females, go to the housing department. They will walk the walk with them and make sure that they are being heard…That is not always the case with remand. Some people will have had quite a few weeks on remand. They may have lost their house because they have gone past the point where they can keep the tenancy and they have nothing else to go back to. They might not have access to a through-care support officer because of the time spent in prison—they might not have known about that provision—so there can be difficulties there as well.v

Teresa Medhurst of the Scottish Prison Service acknowledged the need to work across areas to address the issues caused by remand. She told the Committee that knowledge is being gained from through-care support officers who have supported short-sentence prisoners return to the community—

We are learning about and understanding the impact of imprisonment and the requirement to link with other services in areas such as health, benefits and housing. We are trying to improve that experience for individuals through individual support from our staff and to create arrangements with other national organisations to try to improve the standard arrangements around support for individuals leaving custody.vi

The Committee notes the benefits that properly resourced through-care support can provide in terms of rehabilitation and reintegration when a person is released from prison. However, the Committee heard that the short-time a person usually spends on remand, as well as uncertainty about their release date, can make it difficult to provide such support to remand prisoners. The Committee believes that lessons could be learned from the experience of providing through-care support to short-term convicted prisoners and that similar support should be considered for remand prisoners where appropriate. Steps could also be taken to improve communication between the Scottish Prison Service and partner organisations to facilitate a joined-up approach to providing support for remand prisoners on release where possible.

Welfare and benefits

A period in remand can cause disruption to a person's benefit payments. As Kathryn Lindsay of Social Work Scotland told the Committee—

Access to benefits might need to be reassessed in light of someone not being in the family home. The ramifications are huge and affect every facet of an individual's life, and therefore every facet of their family's life. The average period in remand is something like 23 days—there is all that disruption for 23 days.i

The Committee heard that—

Discharge grants of approximately £75 are provided to all sentenced prisoners on release. Prisoners released from remand, by contrast, receive no financial support and if not in work will typically wait at least 4 weeks for benefit payments to be reinstated.ii

Anne Pinkman elaborated, saying—

A woman who might be caring for children will be released from remand with no finance, and it will take her approximately four weeks to receive any benefit. I have heard the most harrowing stories of how women survive until their benefits are reinstated.iii

In its written submission to the Committee, Shelter explained that there are different entitlements depending on whether a person is on remand or convicted and whether they are in receipt of Universal Credit. Remand prisoners receive up to 52 weeks of housing benefit while awaiting trial or sentencing: greater than the 13 week maximum for convicted (incarcerated) prisoners. However, remand prisoners in receipt of Universal Credit can receive housing benefits for a maximum of six months if they were in receipt of a housing cost element prior to incarceration. Shelter argued—

As Universal Credit continues to roll out and people are transitioned away from legacy benefits and onto Universal Credit, the reduction down to six months’ worth of help with housing costs will negatively affect remand prisoners’ ability to pay for their home while in prison.iv

Shelter also pointed out that while Universal Credit can be claimed up to a month before release, the uncertainty around remand prisoners’ release dates means—

…they cannot benefit from this and are likely to eventually leave prison with very little income and a long time to wait before their first Universal Credit payment. Our advisers state that the most common thing to happen is that prisoners have an appointment scheduled with their local jobcentre to claim benefits, but they will still face a long period of very little income and are more likely to re-offend as a result.iv

Anne Pinkman spoke of the lack of support to resolve benefits and accommodation issues. Individuals may need to make new benefits claims, or have new health issues that need addressing but no support to assist with the process.vi

Kathryn Baker of Tayside Council on Alcohol spoke of the benefits of providing mentors, particularly when dealing with organisations once an individual has been released from prison. Mentors can help with barriers at GP surgeries or benefits agencies—

Initially, the GP or the benefits adviser may not realise that the mentor is not just a friend. As soon as they say, “Actually, I'm this person's mentor,” there is a switch to a different attitude and a different way of treating the client.vii

Women

While evidence pointed to the negative impact of remand generally, a number of witnesses emphasised particular concerns about the use of remand in relation to women. The Committee heard that the women in the prison system are often the most vulnerable, and have complex needs and issues. Anne Pinkman told the Committee—

We know that the majority of women who are received into custody have experienced trauma and that they have extremely high levels of mental health issues. Indeed, we knew way before the establishment of the commission on women offenders that over 80 per cent of women in custody had experienced trauma and abuse, and there is nothing to indicate that that situation has changed.i

Witnesses discussed the damage a time in prison can cause for women. Housing tenancies will often be in a woman's name, and therefore there is a risk of homelessness. Women may fail to disclose that they have children, for fear of them being removed by social services.ii And the Committee heard that when in prison, the primary support for remand prisoners comes from families and visitors but, as Marie Cairns told the Committee, women receive fewer visits—

We are told that females get very few visits from their families; it tends to be the young males who get most of the visits. They tend to get visits from their partners, mums, dads and grandparents, but the male partners of females who are in custody are less likely to visit; they tend to have other things to do. I have spoken to prison staff who worked in HMP Cornton Vale and they said the same: the visit numbers for the females were very low.iii

Elaine Stalker agreed, saying “support networks are not there for women as much as they are there for men.”iii

The Committee heard of many third sector programmes aimed at supporting women in prison, as well as reducing the use of imprisonment for women. Kathryn Lindsay of Social Work Scotland stressed the importance of community-based support—

…such as the wraparound health care and support and the packaging of support to help women to access services that you or I would take for granted, that are important, along with the longevity of that support.v

However, she also spoke of the long-term nature of this support, saying—

We find that women do not leave us. That is a real challenge in terms of the sustainability of that approach. The approach grew from a justice perspective but now there is a recognition that there is a cohort of women in our area—and no doubt in other places in Scotland—who need extra support in order to make and sustain changes in their lives, for their own benefit, for the community's benefit and for the benefit of their children and families.v

Thomas Jackson (Cosla) also told the Committee that programmes for women can take a long time to see results. This can be a challenge when keeping those involved on board, as, for example, with the Tomorrow's Women project it took two years to see behavioural shifts in the women involved. He said—

We must understand that if we target more people who face remand, whom we want to shift to bail, we will have to invest appropriately. We need to recognise that we are dealing with individuals who might live in extremely chaotic situations that it will take longer to unpick.vii

To address the impact on women, a number of third sector initiatives are available. The Committee heard of the positive impact of work done by organisations like Shine Women's Mentoring Service and Circle to assist women in the prison system.

The Committee heard that there are many more such programmes for women than for men.viii While these programmes are clearly successful for the majority of women involved, the numbers of women remanded are unchanged, as is the proportion of those who go on to receive custodial sentences.

The Committee notes the particular impact that a period of time spent on remand can have on female prisoners and those for whom they have caring responsibilities. The Committee recognises the work that many organisations do to mitigate the damage that can be caused by imprisonment, even for a relatively short time, and that these organisations often have to undertake medium to long-term work to see results.

The Committee welcomes the comments from Sheriff Liddle and others that the personal circumstances and caring responsibilities are considered when judges decide whether to grant or refuse bail. Greater availability of criminal justice social workers in court could help to ensure that judges have all the necessary information on a woman's circumstances before making a bail decision.

Young people

The Committee also explored concerns raised about the use of remand for young people, particularly following anecdotal evidence of young people being remanded in Polmont Young Offenders Institute rather than a residential secure facility. Leanne McQuillan addressed both sides of the issue—

Polmont young offenders institution is a bit of a shock for some of the young boys who go there. They go round Edinburgh causing trouble and then, when they go to Polmont, they sometimes get the shock of their lives. That can be a good thing for certain people, who may just need a bit of a fright…I am talking about 16 or 17-year-old boys who think that they are adults, and then they go to Polmont and find themselves alongside people who are in serious trouble. It is very much a culture shock. Some of those boys should probably not be there.

Having said that, there is a problem in various areas of Edinburgh with certain younger boys who constantly reoffend. You see 17 and 18-year-olds on bail who already have more than one page of previous convictions. The courts take account of their age when deciding whether to remand them, but there comes a point when the courts really do not have much choice.i

She went on to say—

It is very rare that a child who does not have any problems in their background goes on a massive crime spree. Most of them have multiple issues, and they are only children. I think that places in secure units are limited and tend to be used for under-16s who cannot go to Polmont—unfortunately, there are still some under-16s who end up being remanded to secure units. I agree, though. Places such as Polmont can cause more harm than good…Some of them think that it is all a great laugh for a while and then, a few years later, they might say, “I've wasted so many years thinking it was great fun going to Polmont and missing out on school and education.” Remand should be avoided, if at all possible, but if someone is on multiple bail orders there are few alternatives.ii

Marie Cairns is based at Polmont and told the Committee that remand can cause different emotions for the families of young people—

Families have told us that they feel relieved that their son or daughter is in prison, because for the first time in a while they have been able to sleep without wondering whether their son or daughter is going to come back or whether the police are going to come to the door. Some families feel that sense of relief when their family member is put in prison. However, for remand prisoners, the families do not know how long they will be in for: it could be seven days, but it could be up to a year before the case comes to court. That is always a concern: they cannot plan because they cannot gauge how long the person is going to be in prison for.iii

Marie Cairns also spoke of the issues faced by young people leaving a period of custody—

For some families, when a person goes into prison, the family feels that that is the last straw. They cannot cope any more. They have made that decision… these young people are leading chaotic lives. Young people who are being liberated who do not have any family support at all are very much on their own. They need some kind of support, but if they are on remand, they not have access to through-care workers—and other agencies, possibly—that could help.iv

However, the Committee heard that work to prevent young people being remanded is successful. Fiona Mackinnon said—

I do not know the numbers, but there has been a massive reduction in the number of young people who are remanded and sentenced. The work with young people and the criminal justice system is a big success story. In the main, they are being kept away from the services of the Scottish Prison Service. A massive amount of work has been done in the community, along with a lot of resources to allow that. There are many lessons to learn from the work with young people and the justice system, some of which can be transferred to work with adults in the justice system.v

Alan Staff, Chief Executive of Apex Scotland, added—

I will back that up. It is absolutely a success story. We were concerned that young people in Polmont generally reported that admission to the young offenders institution was a rite of passage and something to put on their CV, as it were, so anything that can be done to keep young people out of the justice system—or, at least, out of the prison system—must be a good thing.v

Kathryn Baker concurred, saying “We are talking about systemic approaches, and there has been a whole-system approach in youth justice. There is an awful lot that we can learn from that approach.”v

The Justice Secretary agreed that prison is not the best place for young people, saying—

We should try to prevent young people from getting into such settings in the first place. We should work hard to achieve that and our resources should be targeted at reducing the need for young people to end up in custody, through remand or any other means. When young people end up on remand, there is the opportunity to consider other settings, as and when another setting is appropriate for the young person's needs, and in light of safety issues.viii

The Committee welcomes the progress has been made to reduce the number of children and young people in custody, including those held on remand. While the Committee did not explore this issue in detail, the Committee notes and agrees with the Cabinet Secretary for Justice's evidence that when a child or young person is held on remand, consideration should be given to using settings other than a prison or young offenders institution where appropriate to do so.

The impact of remand on children and families

The Committee heard powerful evidence that placing a person on remand can have a negative impact on their family, including any children. Some families may experience considerable stress, especially where procedures are unfamiliar and outcomes unknown, with consequent impact on their physical and mental health and wellbeing. It may put their income and housing at risk, especially where this was previously unstable, and the potential breakdown in trust can lead to division within families and breakdown of family relationships – something likely to have a longer duration than the period of remand.

Additional problems for family members may include the need to travel to prison for visits and the costs involved, and challenges in obtaining information about the case.

One of the most commonly referred to is that of travel and prison visits. Remand prisoners are entitled to more visits than convicted prisoners, and the Committee has heard that in the absence of structured programmes, these visits are the most common form of support available to those on remand. Marie Cairns told the Committee that in relation to young people, prison provision is poor and—

That even goes as far as their benefits. They get no money—nothing at all. In fact, the chaplains have told me that they have often provided deodorants, clothes and stuff to wash their clothes. If those boys—and girls, I assume—do not have family going in to visit, they have nothing at all. Unless they have been convicted, they have no access to anything that is going on in the prison.i

With the pressure on families to provide basic services as well as support, the expectation to visit regularly can be difficult to manage. The Committee heard of people making long bus journeys often at considerable expense, and covering great distances. Barnardo's wrote—

The high level of visits afforded to prisoners on remand can put pressure on families to attend and provide financial support. Children are often taken out of school and have to travel long distances for visits. Whilst visits are often the only activity individuals on remand have, this does place added pressure, on the family.ii

Families Outside added—

Visits from family can help alleviate stress and depression amongst prisoners, but prison visits can be particularly challenging for families during the period of remand…many families are not in a position to travel to a prison for regular visits.iii

They also touched on the uncertainty and stress that families can face—

We know that the families of those on longer sentences face very similar issues to those with relatives who are on remand. It is the fear of the unknown: what is going to happen, and how long will it take? The uncertainty about what is happening in their relative's life, even for what can be a short period of time, can be a real issue.iv

The Committee discussed whether better use of technology could alleviate some of the expectation on family to visit regularly, such as the provision of video conferencing or more regular access to telephones.v

Evidence also highlighted the impact that a person's imprisonment could have on the family's housing or financial situation. In particular, witnesses highlighted that a person's imprisonment on a remand could have knock-on consequences for the benefits received by other family members. Marie Cairns told the Committee:—

We have heard many stories of families having difficulties, particularly if they are receiving their benefits in a joint account. It is really difficult for the person who is left at home to get their benefits because the other person is in prison. It is a big hullabaloo for them to try to get through to the DWP the fact that one person is in prison but the other person still needs to get their benefits. It can create all sorts of problems.vi

As for the impact on children, parental imprisonment is recognised as an adverse childhood experience (ACE). Barnardo's wrote, “Where people have parental responsibilities, particularly care of children, every effort should be made to minimise the disruption in children's lives and reduce the number of children who experience ACEs associated with parental imprisonment.”ii

Families Outside also discussed the impact on children—

Explaining custodial remand to children can be difficult, and younger children are unlikely to draw a distinction between imprisonment for sentence and imprisonment for remand. Children who have witnessed an arrest will be particularly traumatised, and the publicity and stigma surrounding a person's arrest and custodial remand potentially leaves a lasting suspicion from family, friends, and neighbours, even if the person is not convicted.viii

The Committee recognises that parental imprisonment can have severe adverse effects on the children of the prisoner, even if this is for a relatively short period spent on remand. Such childhood experiences can themselves lead to offending behaviour by those children in the future. The Committee recognises the valuable work done by the third sector to support families and children affected by imprisonment.

Reducing the use of remand

A key issue throughout the Committee's inquiry was whether any steps could be taken to reduce what many witnesses perceived to be an inappropriately high use of remand.

Informing the decision-making process

As was discussed earlier, judges are required to make decisions on whether to grant or refuse bail based on the factors set out in the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995. One issue explored by the Committee was whether judges had sufficient information available to them when making a decision on bail.

Sheriff Liddle told the Committee that judges are “fed a lot of information”i prior to making decisions, and take into consideration individual circumstances, including caring duties, when deciding whether to grant or refuse bail. His view was that judges had “adequate information” to make such decisions.i

Anthony McGeehan (COPFS) emphasised that information may be available from criminal justice social workers—

In the real world, [a criminal justice] social worker would be sitting in court and would be aware of the individual because they would see them regularly in that court; they might already be aware of the issues that the individual has and the support that might be appropriate for them. There is knowledge in the system about individuals, but it would be most relevant in the case of the criminal justice social worker, who is perhaps looking to assist the court in its decision-making process on whether bail supervision or remand is the appropriate decision for the individual.iii

However, the Committee heard from other witnesses that criminal justice social workers do not appear to be routinely in the courts, although there are regional variations throughout Scotland. Tom Halpin of Sacro told the Committee, “whether a social worker is available on the day is very much subject to demands on the local department”.iv Kathryn Lyndsay of Social Work Scotland added—

At any given point, a criminal justice social worker might be the only person who is doing that work across several courts in one building, and they will also be in demand from various solicitors who are looking for updated information so that they can inform the court about their individual clients’ circumstances. It is therefore a really complex situation and one that involves a lot of juggling and decision making in real time about where best to use the time.v

Leanne McQuillan, President of the Edinburgh Bar Association, said—

The system was changed quite recently. Before coming to give evidence I spoke to one of the social workers based in Edinburgh sheriff court who told me that the reason for the change was that they felt that their time could be better spent doing other things, although they are available and, if asked, they can come down to court. They are very rarely in court these days but they are in the building.vi