The intergovernmental relations 'reset': one year on

One year on from the 2024 UK General Election, this briefing examines progress and developments relevant to the UK Government's commitment to 'reset' its relationship with the devolved Governments in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. The briefing focuses particularly on intergovernmental relations between the UK and Scottish Governments.

Summary

Under the previous UK Conservative Government, the UK and Scottish Governments worked together on a range of issues, such as the implementation of devolved fiscal and social security powers as well as economic initiatives like City Region and Growth Deals. However, there was disagreement between the two Governments over the devolution settlement, especially after the UK's exit from the European Union (EU), with the Scottish Government repeatedly criticising UK Government actions that it saw as intervening inappropriately in devolved matters, disrespecting the Scottish devolved institutions, and reducing their effective powers.

At the UK 2024 General Election, the Labour Party said that it would "reset the UK Government's relationship with devolved Governments in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland". The Party's manifesto offered some specific commitments to support this goal, such as developing a new Memorandum of Understanding on legislative consent and establishing a Council of the Nations and Regions. However, both during and since the 2024 General Election campaign, UK Ministers have tended to emphasise the 'reset' in terms of an improvement in the day-to-day working relationship between the UK and devolved Governments.

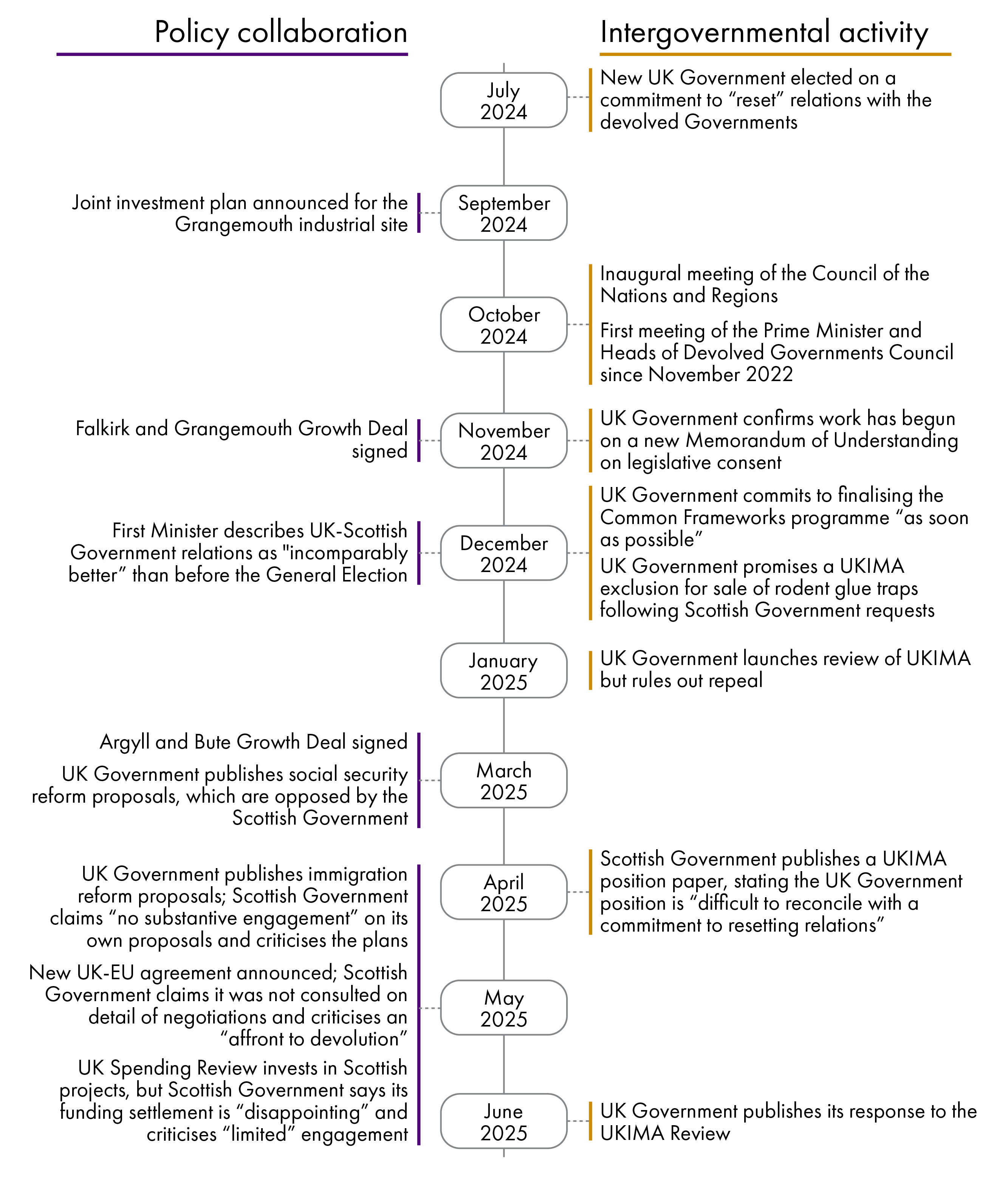

The Secretary of State for Scotland said in June 2025 that, from the UK Government's perspective, its relationship with the Scottish Government "has been reset". The Scottish Government meanwhile has stated that relations with UK Ministers are "more productive and constructive" than under the previous Conservative administration. There have been examples of collaboration in policy areas both Governments see as priorities, such as clean energy, as well as continuing work on initiatives like City Region and Growth Deals.

However, especially since the start of 2025, the Scottish Government has suggested that the UK Government is failing to engage Scottish Ministers sufficiently around key decisions, for example relating to the new UK-EU agreement or the UK Spending Review. There have also been high-profile disagreements between the Governments about UK Government decisions in policy areas such as social security and immigration and how those decisions may affect Scotland.

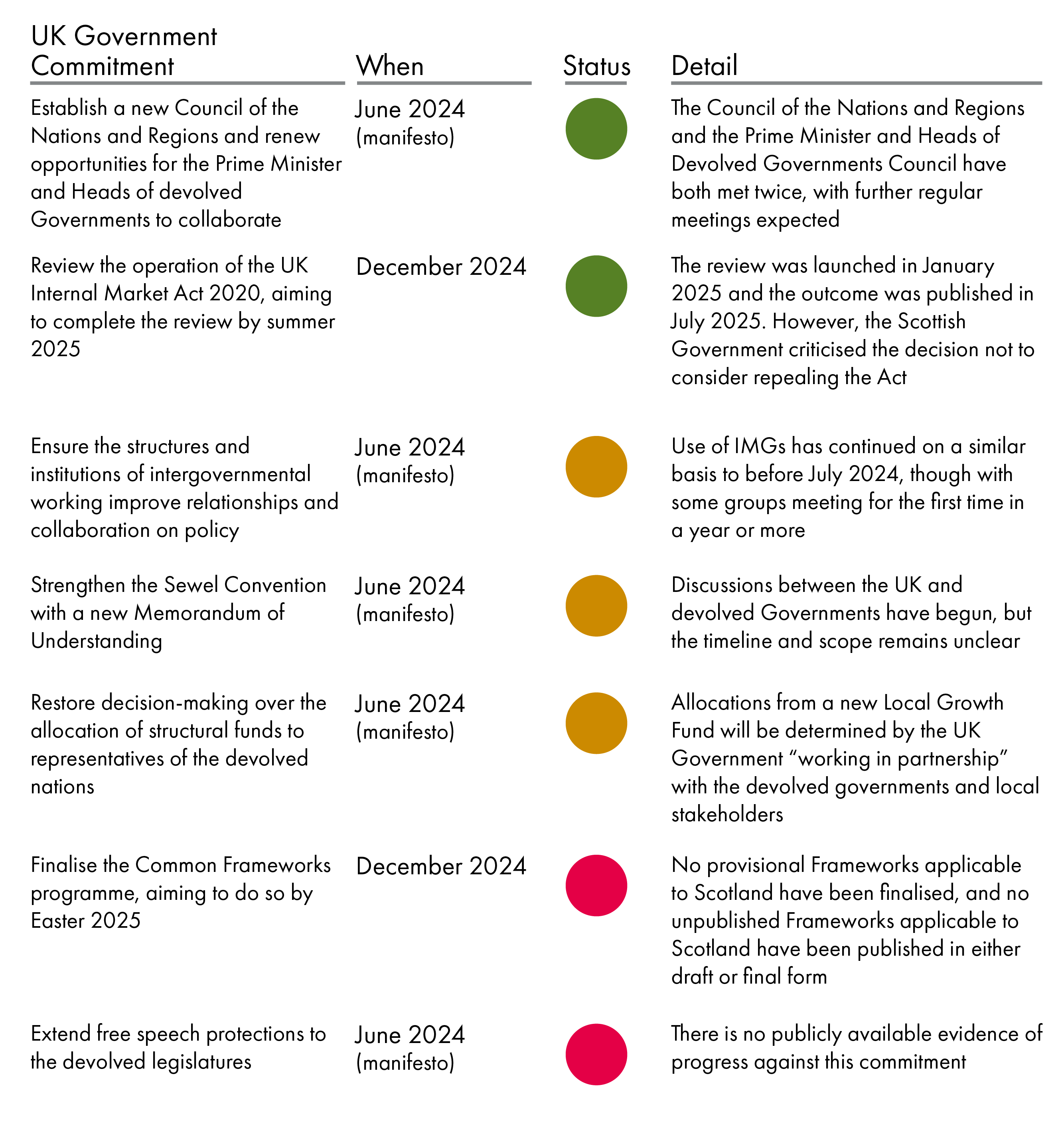

Over the past year, use of formal intergovernmental relations structures has continued on a similar basis to that seen under the previous UK Conservative Government, though with some interministerial forums meeting for the first time after a long hiatus (including, notably, the Prime Minister and Heads of Devolved Governments Council). The UK Government has also fulfilled its commitment to establish a new Council of the Nations and Regions. Discussions between the UK and devolved Governments on a Memorandum of Understanding on legislative consent have begun, but the timescale for this and any progress made to date is unclear.

The UK Government has signalled its intent to use Common Frameworks as the primary means of regulating the UK internal market following the UK's exit from the EU, but as of yet no new Common Frameworks applicable in Scotland have been finalised. The UK Government has published a review of the UK Internal Market Act 2020, legislation which the Scottish Government has described as "the single greatest impediment to more effective and respectful intergovernmental relations". The review commits the UK Government to changing some aspects of how the Act has operated to date, but it has ruled out repealing the Act, despite calls from the Scottish Government to do so.

The Scottish Parliament Constitution, Europe, External Affairs and Culture Committee has highlighted what it has referred to as "the increased interaction between devolved and reserved competence and the greater complexity and ‘shared’ space between the UK and devolved Governments" since the UK left the EU. This underlines the vital importance both of intergovernmental relations and the ability of the two Governments to work together effectively, and of the role of the UK and Scottish Parliaments in scrutinising that activity.

However, the Committee has raised concerns about the transparency of intergovernmental engagement and cooperation. It has also pointed to the potential risks to the Scottish Parliament's legislative and scrutiny functions if the operation of this 'shared space' results in more decisions affecting devolved matters being taken in Westminster, even if this is done with the consent of the Scottish Government. The Committee has launched a new inquiry to consider these issues in greater detail.

A number of developments set in motion during the UK Labour Government's first year in office may continue to affect relations between the two Governments ahead of next year's Scottish Parliament elections. These could potentially include:

the next phase of negotiations regarding the future UK-EU relationship

progress in developing a Memorandum of Understanding on legislative consent

the expected completion of the Common Frameworks programme; and

implementation of the outcomes of the UK Government's Internal Market Act review.

Progress on key commitments

Intergovernmental relations

Intergovernmental relations (IGR) is the term given to engagement between the UK Government and the devolved Governments in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.1 In a Scottish context, it refers to interactions between the Scottish Government and the UK Government, which can include discussions on areas of mutual interest, policy development, and policy implementation.2 While the term covers contact at both ministerial and official levels, discussion of IGR is often focused on political relations.

Within the United Kingdom – as in any system of multi-level government – there is a degree of interdependence between different levels of government, and some overlapping powers and responsibilities. In Scotland, some matters are the responsibility of the Scottish Government and others are the responsibility of the UK Government. In some areas, such as social security, the two Governments share responsibility.

This makes intergovernmental engagement important for effective governance.3 This engagement may include resolving disputes between the UK Government and the devolved administrations, and joint decision-making where two or more administrations share competence or responsibilities.4 In turn, there is a role for the Scottish Parliament in scrutinising the Scottish Government's part in intergovernmental activity.

The UK's exit from the EU has made intergovernmental work even more important to understand. While the UK was a member of the EU, decisions in many policy areas were made at an EU level, but the arrangements put in place following EU exit – such as Common Frameworks and the UK Internal Market Act 2020 – mean many more decisions across various policy areas may now involve intergovernmental working.3 Post-EU exit, therefore, parliamentary scrutiny of IGR also involves understanding these arrangements and how they affect developments in devolved policy areas.

A SPICe briefing published in June 2022 describes the UK's intergovernmental architecture and discusses reforms introduced earlier that year following a joint IGR review undertaken by the UK Government and devolved Governments. The House of Commons Library has also published a briefing on intergovernmental relations in the United Kingdom.

SPICe has launched an intergovernmental activity hub that collates information on intergovernmental activity of relevance to the Scottish Parliament.i SPICe also publishes quarterly updates on intergovernmental activity, which can be accessed via the hub.

IGR under the previous UK Government

Prior to the UK General Election in July 2024, tensions emerged in relations between the then UK Government and the devolved Governments. In particular, the UK's exit from the EU placed pressure on the mechanisms for intergovernmental engagement and led to disagreements about policy and the devolved Governments' role in decision-making.1

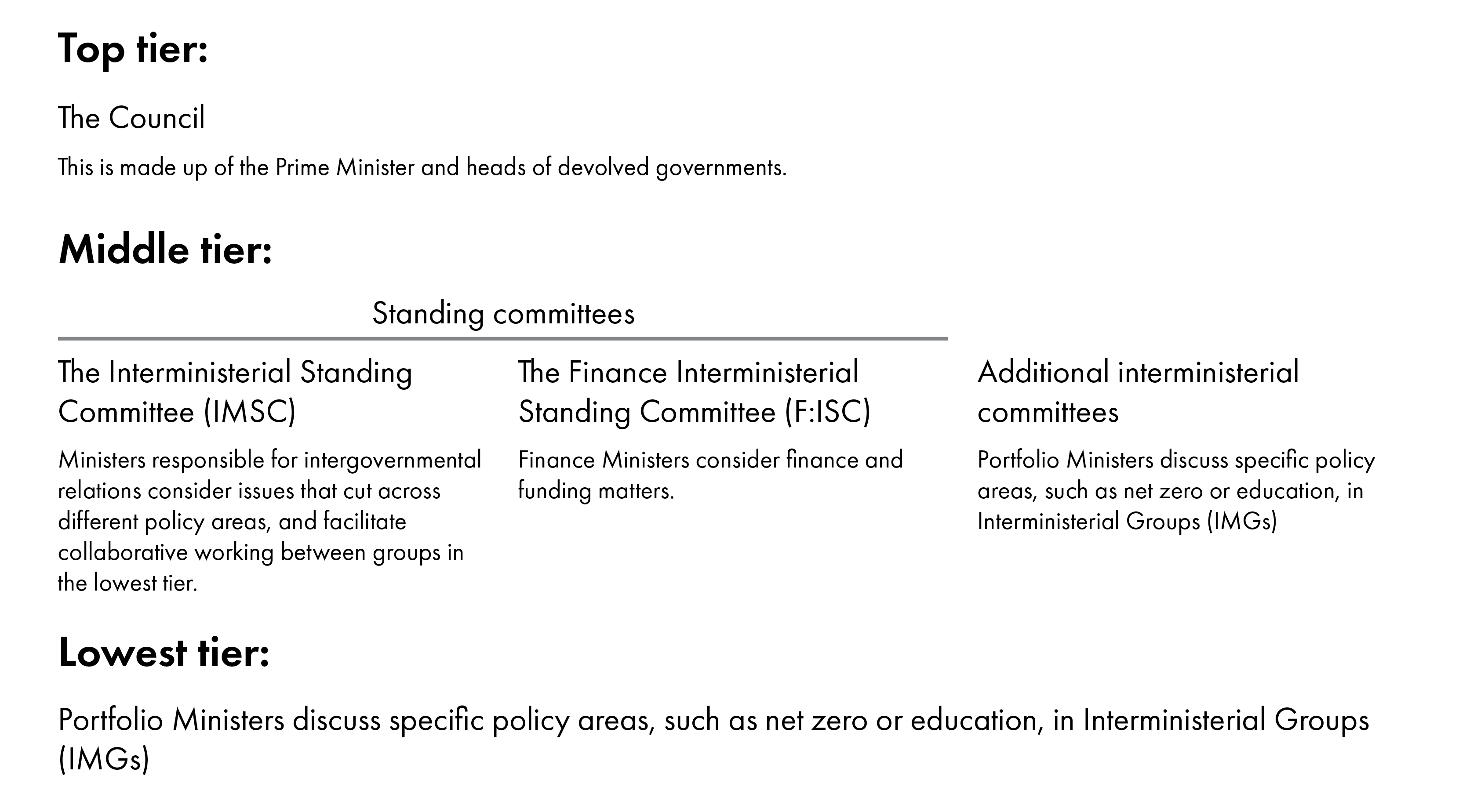

This was despite the introduction of a new three-tier IGR structure in January 2022, which was designed to provide “a positive basis for productive relations”, and support “ambitious and effective” intergovernmental working between the UK Government, the Scottish and Welsh Governments, and the Northern Ireland Executive. 2 In 2023, a total of 124 meetings involving both the UK and Scottish Governments took place, consisting of:

35 intergovernmental meetings held under the formal IGR structures

63 bilateral meetings outside of these structures

and a further 26 meetings outside of these structures also involving one or both of the Welsh Government and the Northern Ireland Executive.3

In a report published during the UK General Election campaign, the Institute for Government (IfG) observed that "relations between the nations have been strained". It drew particular attention to the increasing frequency with which the devolved Governments were withholding consent for the UK Parliament to make provision in devolved policy areas, and suggested that this demonstrated "a clear need for greater coordination and communication between the governments".i

The IfG also observed that "Brexit deepened tensions between the governments", and that intergovernmental relations "deteriorated further with the UK Internal Market Act" (which sought to prevent new regulatory barriers to trade within the UK, but which was opposed by both the Scottish and Welsh Governments who saw it as undermining the devolution settlement).4

In a blog post published just ahead of the UK General Election, Professor Nicola McEwen of the University of Glasgow suggested that the previous eight years had seen notable levels of "tensions and mistrust in relationships between the UK and devolved Governments", arguing that:

Whereas previous UK Governments largely left devolved Governments to manage their own affairs, Conservative Governments since 2016 have been more willing to push back at the boundaries of devolution [...] This more assertive approach to devolution adopted by the Conservatives in office was its way of strengthening and protecting the Union. From the perspective of the devolved Governments, this approach undermined or further discredited the Union.

McEwen, N. (2024). A General Election reset for the Union?. Retrieved from https://www.gla.ac.uk/research/az/publicpolicy/news/headline_1087209_en.html [accessed 7 July 2025]

UK Government perspective

Evidence provided by the UK and Scottish Governments to the House of Commons Scottish Affairs Committee in 2023 and 2024 gives an indication of relations between the two Governments, and their different perspectives on the state of IGR in the lead up to the UK General Election.

Appearing before the Committee in May 2023, then Secretary of State for Scotland, Rt Hon Alister Jack MP, stated that "the UK and Scottish Governments are collaborating and working effectively together in a number of areas", giving examples relating to transport and economic development.1

The then Secretary of State also noted that "inevitably, areas of disagreement have emerged" – citing the Scottish Government's judicial challenge to the UK Government's use of section 35 of the Scotland Act in relation to the Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill, the UK Government's decision on an exclusion from the UK Internal Market Act for the Scottish Government's proposed deposit return scheme, and the Scottish Government's interactions with international governments.1 However, the Secretary of State concluded that, overall:

My assessment of how the UK and Scottish Governments are working together is a very positive one. In conclusion, I would say that we are collaborating on an increasing range of projects that will make real differences to people's lives, and that is exactly what the people of Scotland want and expect.

In a submission to the Committee in September 2023, Mr Jack and the then UK Government Minister for Intergovernmental Relations, Rt Hon Michael Gove MP, stated that the UK Government was "committed to positive and effective working with devolved administrations", and that "significant progress" had been made since the publication of the IGR Review in January 2022. The submission cited a number of examples of joint working between the UK and Scottish Governments, including freeports, investment zones, and city region and growth deals.

However, a subsequent submission to the Committee by the UK Government in April 2024 also implicitly acknowledged tensions between the two Governments, noting that:

The Scottish Government should be focussed on the issues for which it has responsibility under the devolution settlement. Issues such as the constitution and foreign affairs are reserved to the UK Government, and we have been clear with the Scottish Government that they must respect the devolution settlement.

Scotland Office. (2024). Response to Scottish Affairs Committee Call for evidence on the inquiry ‘Intergovernmental Relations: the Civil Service’. Retrieved from https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/129777/pdf/ [accessed 7 July 2025]

Scottish Government perspective

The Scottish Government was more critical of the state of intergovernmental relations under the previous UK Government. In a written submission to the Scottish Affairs Committee in September 2023, it stated that the conduct of IGR had

deteriorated from 2016, as a consequence of Brexit and the opportunity the UK Government clearly believed it presented to pursue what has been called 'muscular Unionism', its increasing intervention in devolved policy matters, and the erosion of the protections provided to devolved institutions, especially the Sewel Convention [...] Overall the Scottish Government is very concerned by developments since 2016.

Scottish Government. (2023). Response to the Scottish Affairs Committee’s inquiry: Intergovernmental relations – 25 years since the Scotland Act 1998. Retrieved from https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/124908/pdf/ [accessed 7 July 2025]

The submission also noted that similar concerns had been expressed by the Welsh Government, quoting a March 2021 statement from then Counsel General and Minister for European Transition Jeremy Miles MS that “the tone of inter-governmental relations has deteriorated due largely to a series of aggressive intrusions by the UK Government into areas of devolved competence".1i

The arguments put forward by the Scottish Government in its submission echoed those set out in a paper it had published in June 2023, which outlined the Scottish Government's view of the impact of UK Government actions since the EU referendum in 2016 on the devolution settlement and the Scottish Parliament. This paper highlighted a number of tensions in the relationship between the two Governments, including:

The passage of the UK Internal Market Act 2020, without the consent of the Scottish Parliament, which the Scottish Government argued "reduces the effective powers of the Scottish Parliament"

The increasing number of powers available to UK Ministers, contained in Acts of the UK Parliament, to act and make policy in devolved areas, in many cases without requiring the agreement of Scottish Ministers or scrutiny by the Scottish Parliament

The UK Parliament passing multiple Acts making provision in devolved areas without the consent of the Scottish Parliament, thereby undermining the Sewel Convention

The then UK Government's decision to use its power under Section 35 of the Scotland Act to prevent the enactment of the Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill

The differing policies of the Scottish Government and the then UK Government on EU exit and the reform and revocation of retained EU laws

UK Ministers' powers to spend money throughout the UK (including on initiatives that would otherwise be considered devolved matters) via the financial assistance powers contained in the UK Internal Market Act, as well as the then UK Government's prospective involvement in devolved areas through its "levelling up" agenda

The Scottish Government's suggestion that the then UK Government had reduced the funding available to Scotland compared to that expected from equivalent EU funding schemes, and the then UK Government's approach of providing that funding directly to local authorities rather than this being distributed via the Scottish Government.3

The Scottish Government's September 2023 submission to the Scottish Affairs Committee did point to "recent examples of practical and constructive engagement and joint working between the Scottish and UK Governments", for example on support for displaced Ukrainians and the updated agreement on the Scottish Government's Fiscal Framework.

A subsequent submission to the Committee by the Scottish Government in May 2024 highlighted further examples of collaborative working, on the implementation of newly-devolved social security powers as well as economic development initiatives like Green Freeports and Regional Growth Deals.

However, in a covering letter for the September 2023 submission, the Cabinet Secretary for Constitution, External Affairs and Culture, Angus Robertson MSP, pointed to the UK Government's "continued attempts to undermine devolution since 2016 and its continued disrespect [...] both for the Scottish Government and for the Scottish Parliament".1

Giving evidence to the Scottish Affairs Committee in March 2024, the Cabinet Secretary described "a state of mind in Whitehall, which is that the devolved Administrations are to be managed or put in their place". Mr Robertson argued that "the bottom line is that the UK Government does not take intergovernmental relationships seriously" – suggesting, for example, that UK Ministers were unwilling to meet their Scottish counterparts, and failing to share documents or to reply to correspondence from Scottish Ministers.5

In its September 2023 submission to the Committee, the Scottish Government argued that UK Government actions since 2016 had served to "frustrate the purpose of devolution and risk making the settlement practically unworkable" – while also noting that "previous experience demonstrates this does not have to be the case". However, it argued that "both reforms and cultural changes are necessary to rebuild trust and confidence in the IGR system", and that a "step change in attitude and behaviour from the UK Government" was needed to deliver a genuine improvement in relations.

Scottish Parliament perspective

The Scottish Parliament's Constitution, Europe, External Affairs and Culture (CEEAC) Committee examined intergovernmental relations, and IGR-related developments, in many of its Session 6 reports prior to the 2024 UK General Election. The Committee had itself called for an IGR 'reset' in November 2022, when it argued that there was a

need to reset the constitutional arrangements within the UK following EU withdrawal, both in respect of relations between the UK Government and the devolved Governments and between the four legislatures and governments across the UK. These relations are clearly not working as well as they should and this needs to be addressed.

Constitution, Europe, External Affairs and Culture Committee. (2022). Legislative Consent Memorandum for the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill (UK Parliament legislation). Retrieved from https://digitalpublications.parliament.scot/Committees/Report/CEEAC/2022/11/14/c9aa979d-01f0-4f3d-b02d-93df8e4b5e73 [accessed 7 July 2025]

In its October 2023 report on How Devolution is Changing Post-EU, the Committee observed that following EU exit, "the management of the regulatory environment across the UK is now dependent on effective intergovernmental relations" – but that there had been "significant disagreement between the devolved institutions and the UK Government" on this point. The Committee also suggested that:

There are significant differences between the UK Government and the devolved Governments in how they view the extent of change to the operation of the devolution settlement outside of the EU. Fundamentally, there remains an ongoing disagreement regarding the extent to which the executive and legislative autonomy of the devolved Governments and legislatures have been undermined.

Constitution, Europe, External Affairs and Culture Committee. (2023). How Devolution Is Changing Post-EU. Retrieved from https://digitalpublications.parliament.scot/Committees/Report/CEEAC/2023/10/24/6692fb8e-0bf0-47cd-a1ba-cff461d9395d [accessed 7 July 2025]

Specific changes in the devolution settlement which the Committee noted had led to a deterioration in IGR included the introduction of the UK Internal Market Act 20203 and the "strain" placed on the Sewel Convention following EU exit.4

On the Sewel Convention specifically, the Committee expressed concern about "the extent of UK Government consultation with devolved Governments on legislative proposals affecting devolved matters prior to the introduction of Bills at Westminster; and the number of Bills which are proceeding without the consent of the devolved legislatures". It pointed to examples – such as the Retained EU Law (Revocation and Reform) Bill – where it claimed intergovernmental engagement was "not working as intended",5 and argued that the level of disagreement between the UK and devolved Governments regarding the Convention's operation was "not sustainable".2

The Committee's October 2023 report on How Devolution is Changing Post-EU gave particular consideration to what it referred to as "the increased interaction between devolved and reserved competence and the greater complexity and ‘shared’ space between the UK and devolved Governments". It suggested that the expansion of this 'shared space' post-EU exit had implications not just for the UK and devolved Governments and relations between them, but also for the Scottish Parliament in terms of its competences and scrutiny functions.

As part of its February 2022 report into the UK Internal Market, the Committee had previously noted "a risk that the increasing shift towards intergovernmental working, as a consequence of the UK leaving the EU, may result in reduced democratic oversight of the Executive". It had highlighted that "the emphasis on managing regulatory divergence at an inter-governmental level" – principally through Common Frameworks, which seek to manage any divergence on a consensual basis – could lead to less transparency, with limited opportunities for scrutiny of this activity by the Scottish Parliament.3

The Committee's October 2023 report reiterated this concern, arguing that:

The increased significance of intergovernmental relations within a shared governance space raises substantial challenges for parliamentary scrutiny. The Committee considers that these challenges are structural and systemic as well as a consequence of political disagreements between governments. This is primarily because the management of the regulatory environment across the UK is now dependent on effective intergovernmental relations which could involve a significant increase in UK-wide legislation in devolved areas. There is, therefore, a significant risk that laws made at a UK level in devolved areas will lessen the accountability of the Scottish Ministers to the Scottish Parliament.

Constitution, Europe, External Affairs and Culture Committee. (2023). How Devolution Is Changing Post-EU. Retrieved from https://digitalpublications.parliament.scot/Committees/Report/CEEAC/2023/10/24/6692fb8e-0bf0-47cd-a1ba-cff461d9395d [accessed 7 July 2025]

A further, related aspect of the 'shared' governance space the Committee has drawn attention to in multiple reports is the increasing capacity of UK Ministers to make secondary legislation in devolved areas. It has noted that the UK Parliament has passed "numerous" Acts containing such delegated powers, "not solely in policy areas previously within EU competence", and that "there is no generic process or overarching agreement as to how the use of these powers should work" – highlighting, for example, inconsistency in the requirements on UK Ministers to seek the consent of or to consult with Scottish Ministers when exercising these powers.2

The Committee has expressed a view that:

The extent of UK Ministers’ new delegated powers in devolved areas amounts to a significant constitutional change. We have considerable concerns that this has happened and is continuing to happen on an ad hoc and iterative basis without any overarching consideration of the impact on how devolution works.

Constitution, Europe, External Affairs and Culture Committee. (2022). The Impact of Brexit on Devolution. Retrieved from https://digitalpublications.parliament.scot/Committees/Report/CEEAC/2022/9/22/1b7a03d8-e93c-45a4-834a-180d669f7f42 [accessed 7 July 2025]

As well as questioning the appropriateness of these powers being given to UK Ministers, the Committee has also suggested that this trend may pose a risk to the Scottish Parliament's legislative and scrutiny function – since, unlike with regulations made by Scottish Ministers, the Scottish Parliament has no formal role in scrutinising secondary legislation laid in the UK Parliament.4

The Committee has called for the UK and devolved Governments to reach an agreement on the use of delegated powers by UK Ministers in devolved areas, which recognises the constitutional principle that devolved Ministers are accountable to their respective legislatures for the use of powers within devolved competence.2

The commitment to 'reset' relations

The Labour Party's UK manifesto for the 2024 UK General Election made the following commitment:

As part of Labour's plans to clean up politics and return it to the service of working people, we will reset the UK Government's relationship with devolved Governments in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland.

Labour Party. (2024). Change: Labour Party Manifesto 2024. Retrieved from https://labour.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Labour-Party-manifesto-2024.pdf [accessed 7 July 2025]

The manifesto claimed the previous UK Government had "weakened our country by disrespecting the legitimate role of devolved Governments and Parliaments". It made a number of specific commitments relating to the devolution settlement, including to:

ensure the structures and institutions of intergovernmental working "improve relationships and collaboration on policy"

strengthen the Sewel convention with "a new memorandum of understanding outlining how the nations will work together for the common good"

"renew opportunities for the Prime Minister and Heads of devolved Governments to collaborate with each other", including establishing a new Council of the Nations and Regions

ensure members of devolved legislatures have the same free speech protections enjoyed by MPs at Westminster

ensure that UK-wide bodies are "more representative" of the UK's nations and regions

"restore decision-making over the allocation of structural funds to the representatives" of Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland.

Specific commitments relating to Scottish devolution included to:

"protect and respect devolution and reset relations" between the UK and Scottish Governments

ensure the devolution settlement for Scotland "enables collaboration on Labour's national missions for government"

"a more collaborative approach" by the UK to the Scottish Government's international engagement, including to "support the Scottish Government to partner with international bodies where relevant and appropriate".

The manifesto identified key policy areas where it said a Labour UK Government would work with the Scottish Government, including in relation to economic growth, supporting people into employment, and child poverty.1

Speaking during the election campaign, the then Shadow Secretary of State for Scotland, Ian Murray MP, said that a Labour-led UK Government would "reset the relationship between the UK and Scottish Governments with new ways of working", and "prioritise co-operation over conflict".3

In a blog post analysing the Labour Party's manifesto, Professor Nicola McEwen of the University of Glasgow claimed that the document suggested a UK Labour Government would offer "fewer direct challenges to the authority of the devolved institutions" than its Conservative predecessor, but only "modest changes to constitutional policy".

Professor McEwen concluded that, on the basis of the commitments set out in the manifesto, any 'reset' would be more focused on culture than on structures, writing that:

Frequent references to resetting UK Government-devolved Government relations lack detail [...] Constitutional safeguards for devolution and intergovernmental relations are notable for their absence. A new approach to devolution and intergovernmental relations may yet transpire under a Labour government, but it will be one that rests on goodwill, a spirit of cooperation and investment in rebuilding trust.

McEwen, N. (2024). A General Election reset for the Union?. Retrieved from https://www.gla.ac.uk/research/az/publicpolicy/news/headline_1087209_en.html [accessed 7 July 2025]

In a blog for the UK Constitutional Law Association, Dr Chris McCorkindale and Professor Aileen McHarg argued that the commitments in the Labour Party's manifesto marked "an important tonal shift" on the future of devolution and IGR compared to the then current Conservative UK Government, though they suggested that the language in the document was "vague".i

Like Professor McEwen, Dr McCorkindale and Professor McHarg noted that the manifesto emphasised improving ways of working between the UK and devolved Governments over greater statutory definition of and safeguards for the devolution settlement, and warned:

There is a real risk that by rejecting more fundamental reform – by favouring political rather than legal regulation of the territorial constitution – Labour's approach will retain or store up the major problems of political regulation that led us to the current state of territorial tension.

McCorkindale, C., & McHarg, A. (2024). The Territorial Constitution and the 2024 UK General Election. Retrieved from https://ukconstitutionallaw.org/2024/06/20/chris-mccorkindale-and-aileen-mcharg-the-territorial-constitution-and-the-2024-uk-general-election/ [accessed 7 July 2025]

Subsequent commentary

Following the General Election, held on 4 July 2024, new UK Ministers continued to use the language of 'resetting' relations with the devolved Governments:

Following his appointment as Secretary of State for Scotland on 5 July 2024, Rt Hon Ian Murray MP said that he was "determined to reset the relationship between the UK and Scottish Governments", and that "focusing on co-operation and joint working will mean we can deliver better results for people in Scotland".1

In remarks he made in Downing Street on 6 July, the new Prime Minister, Rt Hon Sir Keir Starmer MP, announced that he would be visiting Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland later that week to meet the Heads of the devolved Governments, "not just to discuss the issues and challenges of the day [...] but also to establish a way of working across the United Kingdom that will be different and better to the way of working that we've had in recent years".2

First Minister John Swinney MSP met the Prime Minister at Bute House on 7 July 2024, and afterwards set out his intention to "work with Sir Keir's new Government to deliver progress for the benefit of people in Scotland". The First Minister said that he was "confident we have established the foundation for a productive relationship between our two governments based on renewed respect for the devolution settlement".3

The new UK Government's legislative programme was announced in the King's Speech on 17 July 2024. In a Scottish Government press release reacting to the Speech, Deputy First Minister Kate Forbes MSP "reiterated the Scottish Government's intention to work collaboratively with the UK Government to deliver on shared ambitions for Scotland", and was quoted as saying:

The Prime Minister has said he wants to reset the relationship with the Scottish Government, respect the devolution settlement and work constructively together. I am pleased to see this approach reflected in the King's Speech, and we will support the opportunities it presents to improve the lives of people in Scotland.

Scottish Government. (2024). Deputy First Minister comments on King’s Speech. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/news/deputy-first-minister-comments-on-kings-speech/ [accessed 7 July 2025]

Giving evidence to the House of Commons Scottish Affairs Committee in November 2024, the Secretary of State for Scotland Rt Hon Ian Murray MP suggested UK and Scottish Ministers were "working very closely together" on common agendas in policy areas like energy and net zero.5

The Secretary of State argued that while "you cannot syringe the politics out of the relationship [...] the working relationship is close", noting that he had already met with the First Minister four times, and the Deputy First Minister five times. Asked what a successful reset would look like, Mr Murray answered: "Resetting our relationship is about both delivering for the people of Scotland and making sure that people can see both Governments working together".5

Speaking in December 2024 following a meeting with the Prime Minister in Edinburgh, the First Minister John Swinney MSP was quoted as having described relations between the UK and Scottish Governments as "incomparably better than they were immediately before the general election". Mr Swinney said that he had had "a number of one-to-one meetings" with the Prime Minister over the previous six months, with discussions being held "in good faith".7

However, more recent statements by the Scottish Government have also highlighted continuing tensions between the two Governments and obstacles – from Scottish Ministers' perspective – to the 'reset' of relations.

In a position paper on the UK Internal Market Act published in April 2025, the Scottish Government noted that the scope of the UK Government's review of the Act, launched in January 2025, "was set unilaterally by the UK Government, with no reference to the preferred option of the Scottish (and Welsh) Governments". The paper suggested that "this is difficult to reconcile with a commitment to resetting relations with the devolved Governments".

In May 2025 a new agreement between the UK and the EU was announced which included a renewed agenda for UK-EU co-operation in areas such as emissions trading, agri-food and fisheries. While welcoming some aspects of the deal, the Cabinet Secretary for Constitution, External Affairs and Culture Angus Robertson MSP told the Scottish Parliament that the UK Government had made the agreement "without the explicit engagement of the devolved Governments on the negotiation detail – not least on fisheries", which he described as "an affront to devolution".8

Mr Robertson claimed that the UK Government had cancelled three scheduled meetings of the relevant Interministerial Group before the agreement was announced, and declared that "excluding devolved Governments from meaningful consultation, repeatedly cancelling communications and sharing important details only after agreement has been reached in devolved areas is not a reset".8 However, the Secretary of State for Scotland has said that the Scottish Government were "fully informed all the way through" the negotiation process.10

Speaking following the announcement of the UK-EU deal, First Minister John Swinney MSP said the UK Government's alleged failure to explicitly consult the Scottish Government about the provisions in the agreement "demonstrates that the UK Government is not engaging as seriously in intergovernmental relations as I would expect it to do". Mr Swinney was reported as saying that it was a "fair assessment" that relations between the two Governments were "deteriorating", and that "the rhetoric of a resetting of relationships [...] is not really turning into reality".11

In June 2025, Mr Robertson summed up the Scottish Government's perspective on the state of intergovernmental relations as follows:

Although the current relationship with the UK Government is more productive and constructive than it was with its predecessor, areas of significant concern remain, most notably in relation to information sharing and substantive discussion around significant developments such as the US trade deal and the EU reset deal, which were both announced without sufficient engagement with the devolved Governments. There are also a number of areas in which the UK Government is falling short on its commitment to reset intergovernmental relations by failing to take account of Scotland's needs in its work on areas such as eradicating child poverty, migration and the Internal Market Act review.

Scottish Parliament. (2025). Meeting of the Parliament, 4 June 2025. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/chamber-and-committees/official-report/search-what-was-said-in-parliament/meeting-of-parliament-04-06-2025?meeting=16470&iob=140628#orscontributions_M16185E422P758C2696299 [accessed 7 July 2025]

Further detail relating to intergovernmental collaboration and disagreement on the policy areas highlighted by the Cabinet Secretary, as well as in relation to the UK Internal Market Act review, are set out elsewhere in this briefing.

In a June 2025 blog for the Constitution Unit at University College London, Senior Research Fellow Lisa James argued that "it is too early to tell how far the government has been able to deliver on its key manifesto pledge to ‘reset’ the relationship between Whitehall and the devolved nations". The blog noted that while the commitment to establish a Council of the Nations and Regions had been achieved, progress on other manifesto pledges relating to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland remained "very preliminary".

Intergovernmental activity since July 2024

The following section provides an overview of intergovernmental activity since the UK Labour Government took office. It focuses on three areas of activity: meetings between UK and Scottish Government Ministers in the formal intergovernmental relations (IGR) structures, management of the UK internal market, and requests for the Scottish Government and the Scottish Parliament to consent to the UK Parliament passing new legislation which includes relevant devolved provision.

SPICe publishes quarterly updates to give an overview of intergovernmental activity, which can be found on SPICe's intergovernmental activity hub. Under the previous Conservative administration, the UK Government also published quarterly and annual IGR transparency reports. No such reports have yet been published under the UK Labour Government.

Following the joint review of intergovernmental relations undertaken by the UK Government and devolved Governments in January 2022, an impartial IGR Secretariat was established. Part of its role is to produce an annual report on IGR activity. In a House of Lords debate in April 2025, UK Government Minister Baroness Anderson of Stoke-on-Trent said that the UK Government was "currently considering how we can supplement the impartial Intergovernmental Relations Secretariat's annual report, the first of which is forthcoming, with our own reporting from a UK Government perspective".

Interministerial meetings

Formal intergovernmental interactions, involving Ministers and/or officials from the UK Government and each of the devolved Governments, take place under the following structure, which was established in January 2022. A SPICe blog provides more information on how the structure operates.

According to the records of interministerial meeting communiqués published on the UK Government's website, there have been at least 25 meetings held under the formal intergovernmental relations (IGR) structures since July 2024.1 A breakdown of the number of meetings known to have taken place per group (that is, meetings for which a communiqué has been published) is set out in the table below:i

| Group name | Number of meetings since July 2024 |

|---|---|

| Prime Minister and Heads of Devolved Governments Council | 2 |

| Interministeral Standing Committee | 3 |

| Finance: Interministerial Standing Committee | 3 |

| Interministerial Group for Business and Industry | 2 |

| Interministerial Group for Elections and Registration | 1 |

| Interministerial Group for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs | 3 |

| Interministerial Group for Health and Social Care | 2 |

| Interministerial Group for Housing, Communities and Local Government | 1 |

| Interministerial Group for Net Zero, Energy and Climate Change | 3 |

| Interministerial Group for Safety, Security and Migration | 1 |

| Interministerial Group for Trade | 1 |

| Interministerial Group for Transport Matters | 2 |

| Interministerial Group on UK-EU Relations | 1 |

This total of 25 meetings held under the formal IGR structures over the 12-month period since July 2024 compares to a total of 23 meetings held between January and December 2022, and 35 meetings between January and December 2023. Based on the published communiqués available on the UK Government website, 13 meetings were also held in the six months between January and June 2024. A Senedd Cymru research article published in April 2025 concluded that "there isn't yet evidence that meetings within formal structures are happening more frequently than under the previous UK Government".

For some groups, their activity since July 2024 continues a pattern of regular, frequent meetings that was already in place under the previous UK Government - for example, the Interministerial Groups (IMGs) for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs and for Net Zero, Energy and Climate Change, both of which met five times during 2023.2

On the other hand, some groups that have met since July 2024 had not previously met for an extended period – for example, the IMG for Business and Industry (which had previously last met in January 2023) and the IMG for Safety, Security and Migration (which had last met in July 2023). The October 2024 meeting of the Prime Minister and Heads of Devolved Governments Council, the 'top tier' of the formal IGR structures, was the first meeting of this group since November 2022.ii

Interministerial Groups listed on the UK Government website, but for which no communiqués from any meetings held since July 2024 have yet been published, include the IMG for Culture and Creative Industries (which last met in May 2024); the IMG for Education (last met June 2023); the IMG for Justice (last met January 2024); and the IMG for Tourism (last met November 2021).i

Updated terms of reference have been published for the following IMGs since July 2024:

the IMG for Business and Industry

the IMG for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs

the IMG for Net Zero, Energy and Climate Change

the IMG for Safety, Security and Migration

the IMG for UK-EU Relations.

The communiqué from the February 2025 meeting of the Interministerial Standing Committee stated that the Ministers in attendance (including the Deputy First Minister, Kate Forbes MSP) "agreed plans to update understanding of current activity of Interministerial Groups, with a view to ensuring that inter-ministerial engagement operates efficiently and effectively within appropriate structures.". Speaking to a Senedd Cymru Committee in March 2025, the First Minister of Wales, Eluned Morgan MS, indicated that the review would principally be looking at the "composition" of the different groups.4

The table above does not include additional meetings involving UK and Scottish Ministers which have taken place since July 2024 in formal groups that are outside the three-tier IGR structure, including the two meetings to date of the Council of the Nations and Regions, and at least one meeting of the UK Government-Scottish Government Joint Ministerial Working Group on Welfare (held in November 2024).

It also does not include bilateral and/or informal meetings between UK and Scottish Ministers, for example between the Prime Minister or Secretary of State for Scotland and the First Minister or Deputy First Minister, as well as portfolio-level meetings.iv The First Minister and Prime Minister held bilateral meetings on the same dates as the meetings of the Council of the Nations and Regions in October 20247 and in May 2025.8

Professor Nicola McEwen and Dr Coree Brown Swan have observed that "most interministerial meetings take place outside of the new IMGs".9v This has implications for transparency and parliamentary scrutiny, since (unlike with meetings held under the formal IGR structures), no formal record or communiqué of these meetings is usually published or provided to either the UK Parliament or the Scottish Parliament.

UK internal market

The trade in goods, the provision of services and the recognition of professional qualifications across the four UK nations (known as the UK internal market) has become a key part of what the Constitution, Europe, External Affairs and Culture Committee has referred to as the "shared space" between the UK and devolved Governments since the UK left the EU.1 New laws and processes have been put in place to support the governance of this shared space, most notably the Common Frameworks programme and the UK Internal Market Act 2020 (UKIMA), as explored in a December 2020 SPICe blog.

The UK Labour Government has stated that it sees Common Frameworks as "the most important tool" for the UK Government and devolved Governments to collaborate on the regulation of the UK internal market and to manage policy divergence, and that UKIMA should "complement" Common Frameworks. The Scottish Government has said that it "welcomes and shares the UK Government's ambition" to use Common Frameworks as the key mechanism to manage policy divergence and promote regulatory co-operation. More information on Common Frameworks is outlined in the section below.

The UK Internal Market Act 2020 establishes two 'market access principles' (MAPs) of mutual recognition and non-discrimination. The MAPs do not introduce any new statutory limitations on the competence of the devolved legislatures, but may have an impact on whether the laws they pass are effective in relation to goods and services which come from another part of the UK. This is because the MAPs, in effect, mean that those selling goods or providing services only need to meet the regulatory requirements in the nation where they are originally produced, provided or imported.

The Act allows UK Ministers to exclude certain (categories of) goods or services from the market access principles. They must seek the consent of devolved Ministers before making regulations to do so, but can proceed even where the devolved Governments disagree. Both exclusions currently operating – relating to single-use plastics and heat networks – came into effect under the previous UK Conservative Government.i

Only UK Ministers have the power to introduce new exclusions, but the UK and devolved Governments have agreed a process for considering exclusions in areas covered by Common Frameworks. However, there is limited detail about how exactly this operates in practice, and the final decision on whether to introduce an exclusion sits with the UK Government.ii The process for considering exclusions to the market access principles has been a source of tension between the UK and devolved Governments – for example, in relation to the Scottish Government's request for an exclusion relating to a Scottish Deposit Return Scheme (see below) – and was a major focus of the UK Labour Government's review of UKIMA, which concluded in July 2025.

Professor Thomas Horsley of the University of Liverpool has observed that, in order to avoid devolved policymaking potentially coming into conflict with the MAPs, "one solution for the devolved Governments has been to work jointly with the UK and other devolved Governments towards the adoption of UK-wide regulatory standards".3 During the previous UK Conservative administration, the UK and devolved Governments worked together in this way in areas including deposit return schemes, tobacco and vapes,iii and wet wipes containing plastic.iv

Since July 2024, notable intergovernmental discussions around management of the UK internal market have taken place including on glue traps and deposit return schemes.

Glue traps

During the passage of the Wildlife Management and Muirburn (Scotland) Act 2024 (which received Royal Assent in April 2024), the Scottish Government sought a UKIMA exclusion to implement a ban on the sale as well as the possession and use of rodent glue traps. However, the previous UK Government rejected the request, prompting Shona Robison MSP (then Deputy First Minister and Cabinet Secretary for Finance) to raise concerns that the then UK Government was seeking to use UKIMA "to effectively overturn a policy approved by the Scottish Parliament".4

In December 2024, the UK Government announced that, as part of a "package of measures to demonstrate a more pragmatic approach" to the management of the UK internal market, and "in response to the Scottish Government's previous proposal", it would agree to introduce a UKIMA exclusion for the sale of rodent glue traps, in recognition of the "minimal economic impact" this would have on trade within the UK.5

However, at the time of publication, UK Ministers have not yet introduced the necessary regulations to put the exclusion into law.

Deposit Return Schemes

Following intergovernmental discussions about a potential UKIMA exclusion relating to a Scottish deposit return scheme (DRS) for drinks containers during 2023, the previous UK Government offered a temporary, narrower exclusion than the one requested by the Scottish Government, and the Scottish Government stated that it had "no other option" but to delay the introduction of its scheme and align with UK-wide DRS plans.6 The UK and devolved Governments agreed a joint policy statement in April 2024 committing to launch interoperable deposit return schemes covering the whole of the UK.

After the Welsh Government announced in November 2024 that it would not proceed with the joint process and would instead pursue its own scheme that would include glass,v the UK Government stated that it would "continue to work closely" with the Scottish Government and Northern Ireland Executive to launch the scheme in October 2027.7Regulations to establish a DRS in England and Northern Ireland were approved by the UK Parliament in January 2025, and a Deposit Management Organisation to run the scheme for England, Northern Ireland and Scotland was appointed in May 2025 following an application process that was jointly assessed by the three Governments.8

The Acting Minister for Climate Action, Alasdair Allan MSP, told the Scottish Parliament in March 2025 that the Scottish Government "remains committed to delivering an interoperable deposit return scheme with England and Northern Ireland in 2027". Regulations amending the existing legal framework for a Scottish DRS, to give effect to the policy positions set out in the April 2024 joint policy statement and to confirm the scheme administrator in Scotland, were laid before the Scottish Parliament in May 2025 and came into effect the following month.vi

Legislative consent

According to a political convention known as the Sewel Convention, the UK Parliament will not normally legislate on devolved matters without the consent of the Scottish Parliament. The Convention applies to UK primary legislation that would make provision within the legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament, or that would alter the Parliament's legislative competence or the executive competence of Scottish Ministers.i

When any of these criteria are fulfilled, a member of the Scottish Government must lodge a legislative consent memorandum setting out the Scottish Government's view on whether the Parliament should grant legislative consent. Following the lodging of a legislative consent memorandum, Members of the Scottish Parliament may vote on a legislative consent motion to decide whether to grant or withhold consent for the UK Bill.

A SPICe blog from November 2024 contains more information on legislative consent, and the SPICe intergovernmental activity hub collects and categorises data relating to UK Parliament Bills requiring the consent of the Scottish Parliament.

Based on data available on the Scottish Parliament website, there have been 14 UK Parliament Bills since the UK Labour Government took office in July 2024 in relation to which the Scottish Government has submitted legislative consent memorandums to the Scottish Parliament. To date, the Scottish Government has recommended at least partial consent for all 14 Bills, and the Scottish Parliament has voted to grant at least partial consent for all 12 Bills it has considered.

| Bill title | Scottish Government consent recommendationii | Date considered by Scottish Parliament | Scottish Parliament consent decision |

|---|---|---|---|

| Passenger Railway Services (Public Ownership) Bill | Consent recommended | 31 October 2024 | Consent granted |

| Renters' Rights Bill | Consent recommended | 19 February 2025 | Consent granted |

| Great British Energy Bill | Consent recommendediii | 25 February 2025 | Consent grantediv |

| Data (Use and Access) Bill | Consent recommended | 1 April 2025 | Consent granted |

| Tobacco and Vapes Bill | Consent recommended | 29 May 2025 | Consent granted |

| Absent Voting (Elections in Scotland and Wales) Bill | Consent recommended | 25 June 2025 | Consent granted |

| Animal Welfare (Import of Dogs, Cats and Ferrets) Bill | Consent recommended | 25 June 2025 | Consent granted |

| Public Authorities (Fraud, Error and Recovery) Bill | Partial consent recommended | 25 June 2025 | Partial consent grantedv |

| Employment Rights Bill | Consent recommended | 26 June 2025 | Consent granted |

| Border Security, Asylum and Immigration Bill | Consent recommended | 26 June 2025 | Consent granted |

| Product Regulation and Metrology Bill | Consent recommendedvi | 26 June 2025 | Consent granted |

| Children’s Wellbeing and Schools Bill | Consent recommended | 26 June 2025 | Consent granted |

| Crime and Policing Bill | Partial consent recommended | Not yet considered | Not yet considered |

| Planning and Infrastructure Bill | Partial consent recommended | Not yet considered | Not yet considered |

Giving evidence to the House of Commons Scottish Affairs Committee in November 2024, the Secretary of State for Scotland Rt Hon Ian Murray MP claimed that the legislative consent process had been "working very well" in the early days of the UK Labour Government.1

Similarly, following the February 2025 meeting of the Interministerial Standing Committee (part of the second 'tier' of formal IGR structures), the Deputy First Minister Kate Forbes MSP stated that, during the meeting, she had "reflected on recent positive examples" of the UK Government's approach to legislative consent, and that she had been "clear that this should be the consistent approach going forward".2

In some instances, legislative consent memorandums (LCMs) lodged by the Scottish Government since July 2024 that have not recommended consent or recommended only partial consent have also noted ongoing engagement between the UK and Scottish Governments to seek to address barriers to a consent recommendation.vii This was not generally the case where the Scottish Government lodged LCMs that did not recommend consent to Bills proposed by the previous UK Conservative Government.vii

However, some discussions around legislative consent have highlighted broader disagreements between the two Governments. For example, during the debate on the legislative consent motion relating to the UK Government's Product Regulation and Metrology Bill in June 2025, the Minister for Business and Employment, Richard Lochhead MSP, argued that although the Scottish Government was now recommending consent to the Bill, the fact that, as originally introduced, the Bill would have given UK Ministers powers to make regulations in devolved policy areas without the need to consult or seek the consent of Scottish Ministers and the Scottish Parliament raised "concerns" about the UK Government's "approach to devolution".ix

The Sewel Convention only applies to primary legislation (i.e. Bills), not to secondary legislation (i.e. regulations, for example in the form of UK statutory instruments). The Constitution, Europe, External Affairs and Culture Committee has highlighted what it has described as a "step change" since the UK's exit from the EU in scale of UK Ministers' powers to make secondary legislation within areas of devolved competence.3 Some Acts of the UK Parliament conferring such powers on UK Ministers impose obligations on them to consult with, or to seek or obtain the consent of the relevant devolved Government(s) before those powers can be exercised.4

Since the UK Labour Government came to office in July 2024, Scottish Ministers have notified the Scottish Parliament of their intention to consent to the UK Government making regulations that make provision in an area of devolved competence previously governed by EU law on at least 17 occasions.x Around half of these notifications related to environmental and rural affairs, reflecting the high degree of cooperation between the two Governments in this area.

Developments in devolution and IGR

The following section outlines the principal changes and developments relating to devolution and intergovernmental relations (IGR) that have taken place since July 2024.

The Council of the Nations and Regions

The Labour Party's 2024 UK General Election manifesto promised that, if elected, it would "establish a new Council of the Nations and Regions" to "bring together the Prime Minister, the First Ministers of Scotland and Wales, the First and Deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland, and the Mayors of Combined Authorities" in England.1

The idea for this body originated in a report produced for the Labour Party in 2022 by a Commission on the UK's Future chaired by former Prime Minister Gordon Brown,i which recommended “a new and powerful institution to drive co-operation between all [the UK's] governments". The Commission also recommended that this should be a statutory body, underpinned by a legal obligation of co-operation between the different governments.2

In September 2024, it was confirmed that the Prime Minister would shortly establish a Council of the Nations and Regions. In making this announcement, the Prime Minister was reportedly critical of previous intergovernmental forums, observing specifically that under previous UK Conservative Governments the “Prime Minister didn't bother turning up” to such meetings. By contrast, he described the new body as "a proper council [...] meeting on a regular basis", where he and the Heads of devolved Governments "can look at challenges and opportunities together".3

The Cabinet Secretary for Constitution, External Affairs and Culture, Angus Robertson MSP, reacted positively to the Council's creation, saying that the Scottish Government would “welcome the opportunity for a reset" in intergovernmental relations, and was "ready to work with the new UK Government to agree a collaborative, co-operative approach to intergovernmental relations, which respects devolution and all of the powers of the Scottish Parliament".3

At the time of the Council's establishment in September 2024, the House of Commons Library observed that: "It is not yet clear how the Council of Nations and Regions will interact with the existing IGR system, which already includes a council comprising the Prime Minister and the heads of the devolved administrations".2 Unlike the body envisaged in the Commission on the UK's Future, the Council has been established on an informal rather than a statutory basis, and with no underpinning legal duty of co-operation placed on the attending governments and mayoralties.

Speaking in the House of Lords in March 2025, the UK Government Advocate General for Scotland, Baroness Smith of Cluny, described the Council as "a completely new way of addressing intergovernmental relations". On the question of the Council's interaction with the existing IGR structures, she stated that the Council was "a unique forum" that was "in no way intended to replace any existing structures, but simply to supplement them".6

The first meeting of the new Council was held in Edinburgh in October 2024. According to the communiqué published shortly after the meeting, attendees discussed "opportunities for attracting long-term inward investment", and "confirmed their commitment to working together to leverage maximum investment to all parts of the nations and regions and support economic growth".

The terms of reference for the Council were also published alongside the October 2024 meeting communiqué. These stated that the Council will meet biannually, and will:

"be a central driving forum [...] to determine actions for tackling some of the biggest and most cross-cutting challenges the country faces, on a structured and sustained basis"

"provide a forum to share best practice, to collaborate on shared issues, and agree how to work together to drive delivery on areas of mutual priority"

"focus on shared missions, delivery of public services, and shared values"

"provide regular, sustained, engagement to ensure that [...] the voices of the nations and regions are brought to bear on issues affecting the whole country"

"work alongside existing and planned engagement" between the UK Government and the devolved Governments and English authorities with devolved responsibilities.

The Council met for the second time in May 2025. At the time of publication, a communiqué from that meeting is yet to be published. Speaking in the House of Lords in July 2025, UK Government Minister Baroness Anderson of Stoke-on-Trent said in relation to the May 2025 meeting of the Council that "although a communiqué was not published on this occasion, Ministers will continue to update both Houses through the regular scrutiny mechanisms".

A UK Government press release ahead of the meeting stated that the Prime Minister would use it to "challenge those in attendance to drive economic growth in their local areas to deliver for working people", and also to "lead discussions about spreading AI [artificial intelligence] to help working people access the services that they need in their local areas". In a letter to the Convenors of the Constitution, Europe, External Affairs and Culture Committee and of the Economy and Fair Work Committee following the meeting, the First Minister indicated that discussion had "focussed on trade and tariffs and how artificial intelligence can support our public services and stimulate economic growth".

In a report published in May 2025, the Bennett Institute for Public Policy and PolicyWISEii argued that the Council was "a potentially landmark innovation in the UK's model of territorial government", with "real potential" to improve intergovernmental relations. The report suggested however that the Council "needs a more clearly defined purpose", as well as recognition of the "significant differences between the constitutional standing and capacities" of the devolved Governments compared to English regional mayors. It also called for greater clarity on how the new Council fits into the UK's existing intergovernmental relations architecture.7

Memorandum of Understanding on legislative consent

As outlined above, instances under the previous Conservative administration where the UK Government legislated in devolved areas without the consent of the devolved legislatures were widely seen as having placed "strain" on the Sewel Convention and to have contributed to a decline in intergovernmental relations.

The Labour Party's 2024 UK General Election manifesto included a commitment to “strengthen the Sewel Convention by setting out a new Memorandum of Understanding outlining how the nations will work together for the common good”.1

In a letter to the Constitution, Europe, External Affairs and Culture (CEEAC) Committee in August 2024, the UK Government Minister for the Constitution and EU Relations, Rt Hon Nick Thomas-Symonds MP, confirmed that "the Sewel Convention and the way the UK Government legislates is certainly a priority area and we are intending to strengthen the Sewel Convention with a new memorandum of understanding."

In its November 2024 response to a House of Lords Constitution Committee report, the UK Government indicated that the memorandum would "establish a mutual baseline for engagement, and the importance of good policy outcomes as the main objective of legislation UK-wide". It also stated that it would consider the Committee's proposals on improving transparency in relation to the engagement between the UK and devolved Governments on individual Bills, and the devolution implications of Bills, as part of its work to deliver the memorandum.

Also in November 2024, in evidence to the House of Commons Scottish Affairs Committee, the UK Government Advocate General for Scotland, Baroness Smith of Cluny KC, stated that the drafting of the memorandum was "already underway and is quite well advanced". Baroness Smith described it as "a principles document", which was "seeking to entrench a lot of what already goes on in practice".2

The Secretary of State for Scotland, Rt Hon Ian Murray MP, confirmed in February 2025 that initial conversations between officials in the UK and devolved Governments relating to the memorandum's development had taken place towards the end of 2024, and would be continuing "soon" – though he also emphasised his view that "it is important that we take the time to ensure that this new Memorandum achieves its purpose".3

In a letter to the Conveners of the Public Audit Committee and the Finance and Public Administration Committee following the February 2025 meeting of the Interministerial Standing Committee, Deputy First Minister Kate Forbes MSP said that, at the meeting, she had stated that the Scottish Government was "ready to assist with the development" of the new memorandum, and that she had emphasised that "the scope of the renewal should be done in collaboration and agreement with the devolved Governments".4

Common Frameworks programme

Common frameworks are intergovernmental agreements which set out how the UK Government and devolved Governments will work together to make decisions in certain devolved policy areas, in particular decisions about policy divergence (that is, where different administrations choose to pursue different approaches in a single policy area).

Common Frameworks were originally intended to be used to consider matters which were former EU competences; however, some also state that they may be used to consider related matters within the wider policy area. You can read more about what common frameworks are on the SPICe intergovernmental activity hub and in this February 2022 SPICe blog.

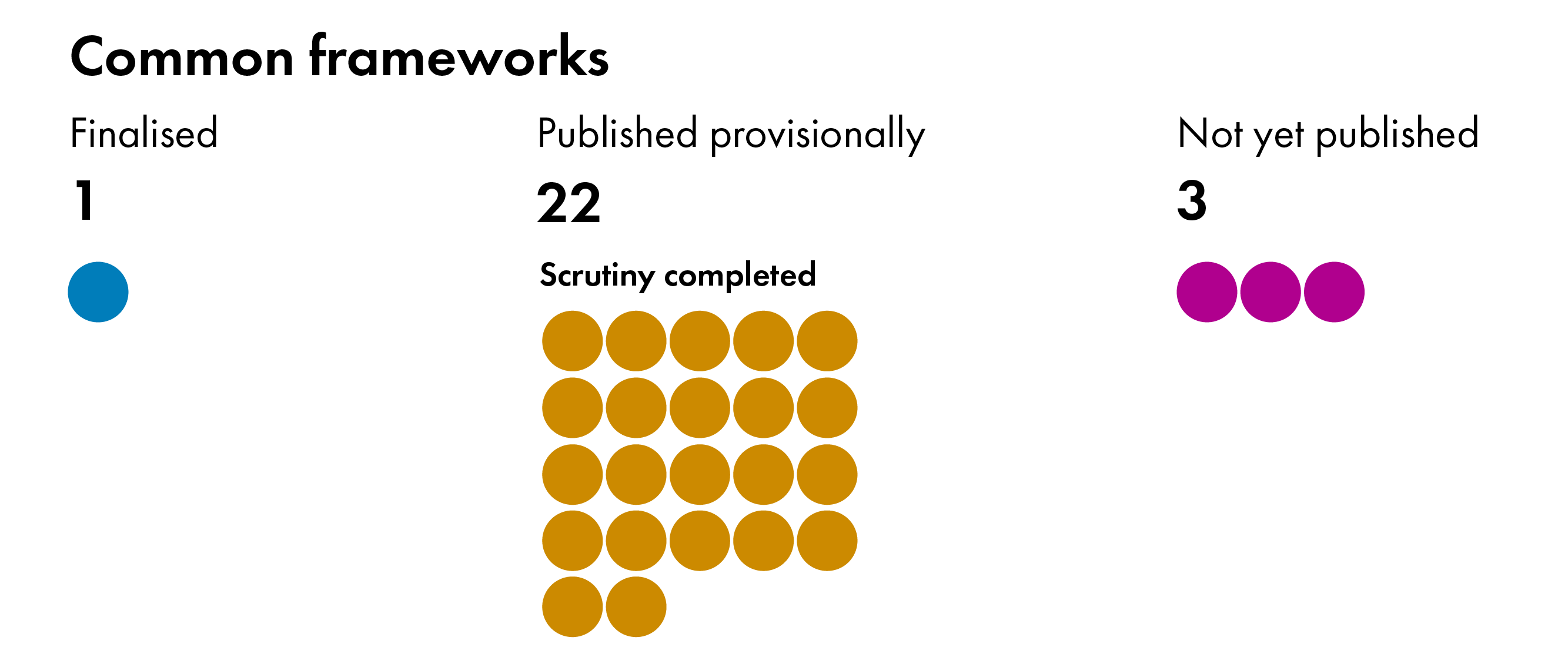

Currently, one Common Framework that applies in Scotland has been finalised, a further twenty-two have been provisionally published and are operational, while three more planned Frameworks that will apply in Scotland remain unpublished. A further six Frameworks apply only to the UK Government and the Northern Ireland Executive.1

In a written statement to the House of Commons in December 2024, the UK Government announced that it was "committed to finishing the Common Frameworks programme as soon as possible" and would aim to do so by Easter 2025. However, despite this commitment, since July 2024, no provisional Frameworks applying to Scotland have been finalised, and the three planned but unpublished Frameworks that will apply in Scotland have not been published in either provisional or finalised form.

The UK Government's December 2024 statement further noted that:

The Government considers Common Frameworks to be the key fora for supporting collaborative policy-making processes in the areas they cover, managing policy divergence between the UK's nations where it occurs, and maximising the benefits of taking different, innovative approaches in different parts of the UK.

UK Parliament. (2024). The Review of the United Kingdom Internal Market Act 2020 [HCWS299]. Retrieved from https://questions-statements.parliament.uk/written-statements/detail/2024-12-12/hcws299 [accessed 7 July 2025]

Similarly, the consultation document published by the UK Government in January 2025 as part of its review of the UK Internal Market Act 2020 (UKIMA) stated that it viewed Common Frameworks as "the most important tool for the UK Government and devolved Governments to find shared approaches or agree on how to manage where one or more parties wish to take a different approach in the areas they cover".

The UK Government's December 2024 written statement also set out its commitment to "developing closer working relationships and increased transparency between the [UK] Government and the Devolved Governments on UK internal market matters that impact significantly on devolved responsibilities within Common Frameworks", and noted the UK Government's position that "the UK Internal Market Act should complement Common Frameworks and support collaborative policy-making".

In a submission to the Constitution, Europe, External Affairs and Culture (CEEAC) Committee in February 2025, Professor Thomas Horsley from the University of Liverpool argued that statements by the UK Labour Government suggested "a fundamental reordering of the relationship between the UKIMA and the Common Frameworks" relative to that seen under its Conservative predecessor – that is, "explicitly prioritising" Frameworks, with UKIMA "relegated" to "the 'background' instrument".

Professor Horsley noted that this could be welcomed on the basis that the Frameworks, by their nature as intergovernmental agreements, inherently involve the "consent and co-design" of each of the four UK nations (unlike UKIMA). However, he also observed that there remain "limitations with the Frameworks in their current form" – namely, that the Frameworks "require further work", that their (re)prioritisation "risks aggravating existing concerns around executive empowerment", and that "without legislative change, the Common Frameworks remain formally subordinate to UKIMA".3

In its April 2025 position paper on the UK Internal Market Act, the Scottish Government welcomed the UK Government's ambition to make Common Frameworks the key mechanism for managing policy divergence and ensuring regulatory co-operation in the areas they cover. However, it argued that UKIMA "does not allow Common Frameworks to perform this role", but instead "conditions and undermines" the Frameworks. It called for the UK Government, as part of its review into the Act, to "set out in detail how it proposes to remove the Act's effect from the operation of Common Frameworks".

In its May 2025 submission to the UK Government's review of the UK Internal Market Act, the CEEAC Committee recommended that the review should address what it concluded was a "lack of clarity" around "the purpose of UKIMA in relation to the operation of Common Frameworks", as well as "the purpose of Common Frameworks given there is little evidence that they are delivering common goals, maximum or minimum standards or harmonisation as initially intended".

In July 2025, the UK Government published what it described as an "in-house process evaluation" of Common Frameworks, which it had carried out between early 2023 and February 2024 (during the previous Conservative administration). This was principally based on data provided by officials from UK Government and the devolved Governments. The evaluation was not designed to assess the impact of the Frameworks, but instead to look at how they are functioning and identify areas for improvement.

Findings from the evaluation process included:

A sense among officials that it was too early to judge how effectively Frameworks were working, but that they were helpful in formalising joint working between Governments, and had led to greater information sharing and joint working "at least to some extent".

Political differences between Governments can make official-level working within Frameworks "more challenging", even if relationships between officials are strong

UK Government tended to be viewed as having "more weight" in Framework discussions, with most meetings across Frameworks chaired by the UK Government who would also take the lead in setting the agenda

The ability of the Frameworks process to handle divergence was perceived not yet to have been fully tested, even within Frameworks where Governments had been considering different policy approaches

There had not yet been much use of the formal dispute resolution processes within Frameworks, but officials were broadly confident in those processes. The evaluation concluded that "there could be greater clarity on how these processes should be used", in particular regarding the distinction between formal and informal disagreements.

The evaluation also identified "six key factors to maximise the effectiveness" of the Common Frameworks programme in future:

Increased sharing of good practice across Frameworks

Increasing co-ordination across Frameworks

Effective levels of stakeholder engagement

Increasing wider knowledge and awareness of Frameworks within governments

Central guidance and monitoring of key Framework processes; and

Further evaluation of Frameworks in the future.4

Review of the UK Internal Market Act

The UK Internal Market Act 2020 (UKIMA) was passed under the previous UK Conservative Government to help regulate the trade in goods, provision of services and recognition of professional qualifications within the UK following EU exit.i It was passed despite both the Scottish Parliament and Senedd Cymru voting to withhold their consent for the legislation.ii

The Scottish Government was also opposed to the Act's passage. It stated in June 2023 that UKIMA "undermines the Scottish Parliament's ability to make laws for Scotland in devolved areas" and represents "the most wide-ranging constraint imposed on devolved competence since 1999".1

The Act contained a statutory obligation for the UK Government to review certain aspects of its provisions by December 2025. In December 2024, the UK Government made a written statement to the House of Commons indicating that it would launch this review in January 2025, with the aim of completing it by summer 2025, ahead of the statutory deadline. The statement also outlined that the scope of the review would go beyond the minimum statutory requirements and would also include "the practical operation of parts 1, 2 and 3 of the Act, including inviting views on the process for considering exclusions from the Act, and the role and functions carried out by the Office for the Internal Market".2

As part of its review, the UK Government ran a consultation between January and April 2025. The consultation document set out the UK Government's position that:

The UK Internal Market Act provides important protections that can, when necessary, facilitate the free movement and trade in goods, provision of services and practice of professions across the UK. It also contains important protections for Northern Ireland's place in the UK internal market and customs union. This review will therefore not consider whether to repeal the UK Internal Market Act or any part of it.

Department for Business and Trade. (2025). UK Internal Market Act 2020: review and consultation relating to Parts 1, 2, 3 and 4. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/uk-internal-market-act-2020-review-and-consultation/uk-internal-market-act-2020-review-and-consultation-relating-to-parts-1-2-3-and-4 [accessed 7 July 2025]

The document also outlined the UK Government's "starting point" that "we do not believe the protections that flow from the [market access] principles should be weakened, but we do want to ensure that the processes around their application are appropriate and transparent".3

The document also set out areas which it said would not be considered as part of the review, including the power for the UK Government to provide financial assistance throughout the UK contained in Part 6 of the Act, which has underpinned UK Government spending in Scotland via mechanisms such as the Shared Prosperity Fund and the Levelling Up Fund. It stated that this provision "remains an important mechanism which enables the UK Government to deliver for people across the UK and on shared priorities with the devolved Governments".3

In February 2025, ahead of a debate in the Scottish Parliament, the Scottish Government issued a press release in which the Deputy First Minister, Kate Forbes MSP, “demanded the repeal of the Internal Market Act and the full restoration to the Scottish Parliament of the powers that were removed by the last UK administration”. The release also noted that MSPs had previously voted to call for the repeal of UKIMA in October 2023.

The Deputy First Minister criticised the UK Government's decision to rule out the possibility of repealing the Act, and argued that this was "a key test for the new UK Government to show whether it intends to continue to ignore the democratic voice of the Scottish Parliament". In the subsequent debate, the following Scottish Government motion again calling for the Act to be repealed was passed by 73 votes to 47: