Constitution, Europe, External Affairs and Culture Committee

How Devolution is Changing Post-EU

Introduction

This report sets out the findings and recommendations of the Constitution, Europe, External Affairs and Culture Committee (“the Committee”) following our inquiry on how devolution is changing outside of the European Union (EU). The Committee thanks all those who provided written and oral evidence and our Advisers, Professor Michael Keating and Dr Chris McCorkindale, for their helpful briefings. All the evidence and briefings are available on the inquiry webpage.

The main focus of our inquiry was on the increased interaction between devolved and reserved competence and the greater complexity and ‘shared’ space between the UK and devolved governments. The Review of Intergovernmental relations, discussed below, recognises that the UK Government and the devolved governments have “a shared role in the governance of the UK.”1

As stated by Professor Keating, although devolution was largely based on the idea that each level would have its own responsibilities, in practice, devolved and reserved powers now overlap and interact with each other.2 Within this context we recognise that devolution has been continually evolving over time through, for example, the significant increase in the powers of the Scottish Parliament following the recommendations of the Calman Commission in 2009 and the Smith Commission in 2015.

The Devolution (Further Powers) Committee interim report on the Smith Commission findings noted that the “shift from a devolution settlement based on a system of largely separate powers to one of shared powers, which is recommended by the Smith Commission, represents a fundamental shift in the structure of [the] devolution settlement.”3

As pointed out by Professor McEwen changes “were already afoot before Brexit came along, with the new devolution settlement making things a lot more complex and interdependent given the split between devolved and reserved powers.” However, “Brexit clearly exacerbated it, creating a completely new constitutional landscape within which devolution is framed.”4

The Chair of the House of Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee (PACAC) told us that a lot of the issues which the Committee is addressing around how devolution works “began before we left the European Union. They have remained unaddressed largely since 1998. That is because of the absence of effective and needful intergovernmental relationships and, indeed, interparliamentary relationships.”5

The Committee notes therefore that the new powers in the Scotland Act 2012 and the Scotland Act 2016 meant that, prior to the EU referendum, devolution had already become much more complex. This included a greater interdependency between reserved and devolved powers and concomitant need for more effective intergovernmental and interparliamentary relations.

A critical difference though is that whereas constitutional change prior to EU-exit was implemented across the UK on a largely consensual basis this has not been the case after EU-exit. Notably, there are significant differences between the UK Government and the devolved governments in how they view the extent of change to the operation of the devolution settlement outside of the EU.

Fundamentally, there remains an on-going intergovernmental disagreement regarding the extent to which the executive and legislative autonomy of the devolved governments and legislatures have been undermined by the constitutional arrangements put in place post-EU exit. In turn, these arrangements have considerable implications for both how the shared space is managed at an inter-governmental level and how it is scrutinised at a parliamentary level.

In Part 1 of the report we examine how the shared space between the UK and devolved governments worked while the UK was a Member State of the EU and how it affected the Scottish Parliament’s competences and core scrutiny functions.

In Part 2 we examine how that shared space has evolved since the decision to leave the EU and how it is impacting on the Scottish Parliament’s competences and core scrutiny functions.

Part 1: The Shared Space Between the UK and Devolved Governments prior to leaving the EU

In this part of the report we look at how the shared space between the UK and devolved governments worked prior to leaving the EU. We also consider how this impacted on the important constitutional principle that the Scottish Parliament has the opportunity to effectively scrutinise the exercise of all legislative powers within devolved competence.

The Informal and Uncodified Parts of the Devolution Settlement

A key part of the devolution settlement are non-statutory agreements and conventions which govern relations between the UK Government and the devolved administrations. Principles for relations between the governments were set out in 1999 and updated in 2013 in an agreement known as the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU).1 The document also includes supplementary agreements on the co-ordination of EU policy and implementation; financial assistance to industry; and international relations touching on the responsibilities of the devolved administrations.

A devolution toolkit which is intended to help UKG officials “take devolution issues into consideration in your work” provides a list of relevant guidance which includes the MoU and Supplementary Agreements and 17 Devolution Guidance Notes. The latter include guidance on UK primary legislation affecting Northern Ireland (DGN8), Wales (DGN 9) and Scotland (DGN 10). DGN 10 provides guidance for UK Government departments on handling primary legislation affecting Scotland including the application of the Sewel convention.

Intergovernmental relations (IGR)

The formal structure of IGR in the United Kingdom was initially set out in the MoU which was intended to provide the procedures for communication, consultation and cooperation between the UK Government and the Devolved Administrations. The MoU is “supplemented by agreements on the establishment of a Joint Ministerial Committee and for certain other areas where it is necessary to ensure uniform arrangements for relations between the UK Government and the three devolved administrations.”1

The MoU also states that the respective governments “will seek:

to alert each other as soon as practicable to relevant developments within their areas of responsibility, wherever possible, prior to publication;

to give appropriate consideration to the views of the other administrations; and

to establish where appropriate arrangements that allow for policies for which responsibility is shared to be drawn up and developed jointly between the administrations.”1

As noted by the Devolution (Further Powers) Committee in 2015, IGR, by design, “in the UK are mainly informal and underpinned by the need for good communication, goodwill and mutual trust.” IGR are intended “to embody and nurture a co-operative working culture among civil servants in different administrations on a day-to-day basis.”3

One of the key findings of the Smith Commission report in 2015 was weak IGR within the UK. Lord Smith noted “the issue of weak inter-governmental working was repeatedly raised as a problem. That current situation coupled with what will be a stronger Scottish Parliament and a more complex devolution settlement means the problem needs to be fixed.” He concluded that both Governments “need to work together to create a more productive, robust, visible and transparent relationship. There also needs to be greater respect between them.”4

The Devolution (Further Powers) Committee recommended that the following should be placed in statute –

general principles underpinning the operation of IGR;

general principles underpinning the structures which will be put in place for dispute resolution;

general principles which will enable Parliamentary scrutiny of this process to take place.3

The Scottish Government responded that we “remain open-minded about the need for statutory underpinning of inter-governmental principles and dispute resolution” but that while “this might help to encourage administrations act in line with the sound principles set out in the MoU, it could prove cumbersome and the mechanism by which it would be enforced is not clear.”6

In response to the findings of the Smith Commission, the Scottish Government and the Scottish Parliament published a Written Agreement on IGR.7 The Agreement recognises the “increased complexity and ‘shared’ space between the Scottish and UK Governments that the powers proposed for devolution entail. It further recognises that the increased interdependence between devolved and reserved competences will be managed mainly in inter-governmental relations.”

The purpose of the Agreement is to “ensure that the principles of the Scottish Government’s accountability to the Scottish Parliament and transparency with regard to these relationships are built into the revised inter-governmental mechanisms from the outset of this structure of devolution.”7

Sewel Convention

The MoU states that “the UK Government will proceed in accordance with the convention that the UK Parliament would not normally legislate with regard to devolved matters except with the agreement of the devolved legislature.”1 The Sewel Convention is also grounded in a shared understanding that, after devolution, while the UK Parliament retained its power to act in relation to devolved matters, the primary responsibility for devolved matters lay with the devolved institutions and that “it is a consequence of Parliament’s decision to devolve certain matters that Parliament itself will in future be more restricted in its field of operation.”1

The Committee has previously noted the view of our Adviser, Dr McCorkindale, that prior to the decision to leave the EU, the Sewel Convention was –

relatively well understood to include both a policy and a constitutional arm;

respected on both sides as a constitutional rule that protected devolved autonomy and facilitated shared governance;

based on the understanding that any decision to withhold consent was the exception rather than the rule but that such a decision generated a constructive response from the UK Government;

based on the understanding that UK legislation in devolved areas would only be made where that legislation was necessary on the part of the UK Government or where it was invited or welcomed by the Scottish Government.

Between 1999 and 2015 the Sewel convention had been engaged more than 140 times in Scotland but consent had been withheld only once and was followed by a compromise.3

The Scottish Government’s view is that “the devolution settlement provided safeguards to prevent the Westminster Parliament removing its powers or legislating or acting in areas of devolved responsibility without the agreement of the Scottish Parliament and Government.” While these “protections were not legally binding but depend on adherence to agreements and conventions in good faith” they “worked as intended from 1999 until the EU exit referendum.”4

In summary the Committee notes the following with regards to how the shared space between the UK and devolved governments worked during the period prior to EU-exit—

The Sewel Convention worked well in relation to primary legislation and the UK Government rarely used delegated powers in devolved areas other than in relation to complying with EU law (discussed below);

Intergovernmental arrangements in specific areas including the co-ordination of EU policy and implementation and international relations were clearly set out in the MoU and supplementary agreements between the UK Government and the devolved governments;

Despite the largely consensual nature of intergovernmental working, concerns about the effectiveness of IGR structures within the context of an increased shared space and an increasingly complex devolution settlement were commonly recognisedi;

Concerns about the ability of the Parliament to carry out its core role of holding Ministers to account in relation to IGR given its inherently confidential nature were also commonly recognisedi.

Delegated Powers

When the Scottish Parliament was established in 1999, UK Ministers’ powers to make secondary legislation in devolved areas were transferred to Scottish Ministers with only a few exceptions.i The main exception was the power to make secondary legislation under section 2(2) of the European Communities Act 1972 to comply with EU law.ii This power was available in devolved areas to both UK Ministers and the Scottish Ministers. As noted by the Scottish Government in correspondence with the Committee, other than this exception the use of SIs in devolved areas “happened rarely.”1

The procedures for the transposition and implementation of EU legislation in the UK were set out in the MoU and the Concordat on Co-ordination of European Union Policy. Paragraphs B4.17 – B4.21 of the Concordat (Annex B to the MoU) set out the underlying principles governing the implementation of EU obligations by the UK Government and the devolved administrations.

The Concordat provided that “it will be the responsibility of the lead Whitehall Department formally to notify the devolved administrations at official level of any new EU obligation which concerns devolved matters and which it will be the responsibility of the devolved administrations to implement.”2

It was then for the devolved administrations to consider, in consultation with the lead Whitehall Department, how the obligation should be implemented, including whether the devolved administrations should implement separately, or opt for UK legislation. Section 57(1) of the Scotland Act 1998 gave the UK Government power to implement EU obligations in devolved areas. As a result, the Scottish Government could decide to pass back responsibility for implementation to the UK Government which could then make GB- or UK-wide regulations.

Where a devolved administration opted to implement separately, the Concordat provided that the devolved administration had a responsibility to consult the relevant Whitehall departments on its implementation proposals to ensure that any differences of approach produced consistency of effect and, where appropriate, of timing.

Guidance for Scottish Government officials on implementing EU obligations included a list of issues to consider in deciding whether it would be more appropriate for the transposition of a Directive affecting a devolved area to be taken forward by the UK Government. For example, would a separate form of transposition allow the Scottish Government to adopt a better form of regulation which would support sustainable economic growth and would a UK Government transposition lead to a better outcome for Scotland?3

In practice in many areas of devolved competence such as the environment, fisheries and agriculture the powers of the Scottish Ministers were largely limited by the need to comply with EU law. UK Ministers were similarly constrained. As pointed out by the Cabinet Secretary, “the shared framework of EU law applied symmetrically to all parts of the UK.”1 On this basis and given the volume and complexity of EU legislation the Scottish Ministers regularly invited the UK Government to legislate on a UK-wide basis.

Where the Scottish Ministers opted to implement EU obligations using devolved powers the Scottish Parliament had the opportunity to scrutinise the relevant subordinate legislation. Where Scottish Ministers opted for UK or GB wide legislation there was no formal scrutiny role for the Parliament. The Scottish Parliament could not scrutinise the legislation and was neither consulted nor asked to consent to the decision to opt for UK wide legislation.

However, the Scottish Government did provide regular reports on the transposition of its EU law obligations including through UK or GB wide legislation. As set out in guidance for Scottish Government officials the responsibilities of the European Relations Division included reporting to the Scottish Parliament on a regular basis on the implementation of EU obligations in devolved areas.3

The Committee notes the following with regards to how the shared space worked in relation to the Scottish Parliament’s legislative function in complying with EU obligations—

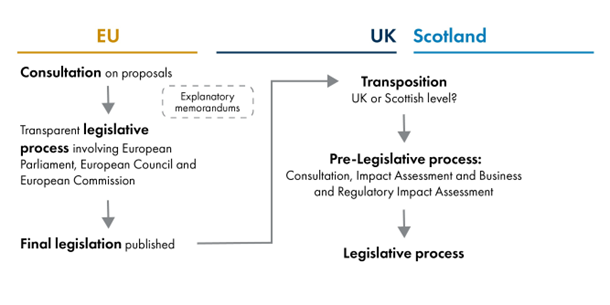

EU law is subject to its own legislative processes including a role for the European Parliament, stakeholders and the public as well as a pre-legislative role for Member States (see Annexe A);

EU law obligations and their consistent effect applied across the UK;

Implementing EU law was a legal requirement and, as such, it was less of an issue from a scrutiny perspective whether the domestic legislation that did so was enacted in Westminster or the Scottish Parliament;

The decision on whether Scottish Ministers or UK Ministers should make the legislation was a matter for the Scottish Ministers;

As such, there was no legislative consent process (the Sewel Convention applies only to primary legislation, and implementation was overwhelmingly done by secondary legislation);

The Scottish Parliament, therefore, had a minimal scrutiny function where a GB or UK approach was adopted;

However, there was a level of transparency and Ministerial accountability through regular reporting to the relevant parliamentary committee and the intergovernmental process, accompanied by guidance for officials, was clear and published.

The Committee’s view is that overall the shared space between the UK Government and the Scottish Government worked well during the period prior to EU-exit. However, this needs to be understood within the context of very limited opportunities for regulatory divergence within the UK given the legal obligations to implement EU law.

It is also apparent that as further powers in areas such as social security and taxation began to be devolved, significant concerns were raised about the weakness of IGR structures within the context of an increasing need for increased shared governance.iii

Part 2: The Shared Space Between the UK and Devolved Governments outside the EU

In Part 2 of the report we examine how the shared space between the UK and Devolved Governments has evolved since the decision to leave the EU. Professor Hugh Rawlings, who was director of constitutional affairs and intergovernmental relations within the Welsh Government, told us that one of the things that we have learned from Brexit “was the extent to which we assumed, without thinking any further, that EU membership provided a framework within which devolution could work. That external mechanism for holding devolution together has now been withdrawn.”1 Professor Jim Gallagher, a former Director General for Devolution in the Cabinet Office suggests that the UK constitution has been stretched “beyond breaking point” by Brexit.1

Professor McHarg’s view is that “Brexit has had profound impacts on devolution” including “significant challenges for the meaningful exercise of devolved autonomy, for effective devolved law and policy making, and for good governance in the devolved policy space.” From a good governance perspective this includes “adverse impacts on the intelligibility, transparency and stability of the boundaries of devolved competence, with knock-on consequences for effective political participation, scrutiny and accountability, constructive inter-governmental relations, and legal certainty and legal risk.”3

Intergovernmental Relations

Until 2022, the formal structures underpinning intergovernmental relations were set out in the MoU between the UK Government and the devolved administrations as noted in Part 1 above. Those structures have been superseded by the review of intergovernmental relations which sets out new structures and ways of working.1The review also sets out the following principles for collaborative working –

Maintaining positive and constructive relations, based on mutual respect for the responsibilities of the governments and their shared role in the governance of the UK;

Building and maintaining trust, based on effective communication;

Sharing information and respecting confidentiality;

Promoting understanding of, and accountability for, their intergovernmental activity;

Resolving disputes according to a clear and agreed process.1

The Committee’s adviser, Professor Keating points out that “the process is widely regarded as an improvement on the previous system.” However, while the assumption is that decisions will be agreed by consensus “there is nothing to bind the UK Government to accept the views of the devolved administrations.”3

Professor McEwen told us that we “have had a big reform of the machinery of intergovernmental relations, but it has not yet been fully implemented. There has been quite a bit of political volatility since that reform was introduced, which has affected its introduction.”4 The Institute for Government told us with regards to Whitehall that “the operation of the intergovernmental relations machinery still tends to be quite patchy and dependent on the extent to which individual ministers and secretaries of state prioritise engagement with the devolved bodies.”4

In this section of the report we examine some of the challenges and issues raised by our witnesses with regards to the operation of IGR after EU-exit.

Scope

The review was limited to intergovernmental mechanisms and ways of working and does not entirely replace the MoU which remains operational. The Scottish Government references the MoU in its document, Devolution since the Brexit Referendum, published in June 2023. For example, “the MoU acknowledges the devolved governments’ interests in trade negotiations and the need for their involvement in such negotiations” and in relation to the exercise of the power under section 35, “the UK Government did not follow the steps set out in the MOU.”1

The Welsh Government notes that while it is anticipated the MOU “will become a largely dormant document” for “the time being, international policy formulation will be developed in line with the current Devolution MoU and its accompanying International Relations Concordat. International obligations will be implemented in line with these agreements”.2

The new structures and ways of working also include provision for the oversight of the Common Frameworks programme including consideration of individual frameworks where necessary. As discussed below, frameworks have been established in order to manage shared and overlapping (formerly EU) competences. The Scottish Government’s view is that frameworks “offer an agreed means to manage regulatory divergence in a post-EU context: an intergovernmental mechanism based on collaboration and mutual respect.” The Welsh Government’s view is that ”Common Frameworks programme has shown that this shared governance can be successful.”3 As noted by our Adviser, Professor Keating these “do not have a standard format and are intended to find pragmatic and technical solutions to issues that might otherwise escalate to the political level.”4

The Review states that as “the UK looks to recover from the challenges of the COVID-19 crisis, strong intergovernmental relations is essential to support and enhance the important work of all governments.” The new structures and ways of working are intended to “provide for ambitious and effective working, to support our COVID recovery, tackle the climate change crisis and inequalities, and deliver sustainable growth.”5

The Committee notes that there is no reference to the need for strong intergovernmental relations in response to an increasingly complex devolution settlement following EU-exit. In contrast one of the key themes arising from our inquiry is the significant impact which leaving the EU has had on IGR within the UK. Philip Rycrofti told us that “you have to see Brexit as a break point in all sorts of ways, including with regard to the management of relationships between the four Governments of the United Kingdom” and “it will require a reconfiguration and reconceptualisation of how those relations are managed.”6

The “increased complexity of the devolution settlement and the implications this has for appropriate discussions between the Welsh and UK Governments” is also recognised by the Welsh Government in an inter-institutional relations agreement with the Senedd. The agreement also recognises that “the interdependence between devolved and reserved competences will be managed mainly in inter-governmental relations.”7

Political Culture and Mutual Trust

Some of our witnesses suggested that the UK’s new constitutional arrangements need to be robust enough to accommodate political differences between governments across the UK. In particular, where there is a breakdown in trust, there needs to be institutional mechanisms which allow inter-governmental working to continue.

Professor Rawlings suggests that “devolution depends, at a fundamental level, on understandings of trust between Governments.”1 Paul Cackette, a former Scottish Government Director, told us that “trust and culture are very hard to develop” and the “trust thing is very difficult for civil servants. There is an institutional inertia, and there are legitimate reasons why information cannot be shared.”1 Professor Gallagher’s agrees that the cultural questions need to be addressed but changing “culture is very difficult.”1

The Committee notes that the review states that “Regular and tailored engagement within these forums will strengthen a shared ambition to operate a culture change across all administrations in their conduct of IGR.”4 However, in correspondence with the Committee the Cabinet Secretary referenced how the Scottish Government has set out in detail5 the ways in which “the actions of the UK Government since the Brexit referendum have eroded the devolution settlement and responsibilities and powers of the Scottish Parliament and Government.”6

In his view this “has been accompanied by difficulties in relations between the UK Government and the devolved governments as its approach, as well as its actions, have failed to adhere to agreed ways of working.”6 He told the House of Lords Constitution Committee in July 2021 that the UK Government had used Brexit to “drive a coach and horses through intergovernmental relationships as they are supposed to work.”8

The Scottish Government’s view is that there “was always a risk that the Brexit process would result in greater centralisation in Whitehall and Westminster” and that the “UK Government’s approach increasingly asserts Westminster’s authority over the Scottish Parliament and Government, something not previously seen under and inconsistent with devolution.”5

The UK Minister for Intergovernmental Relations stated in a letter to the Committee dated 4th September 2023 that across “the last year, there has [been] successful collaboration between the UK Government (UKG) and the devolved administrations [DAs].” In his view there “are, of course, areas where administrations will have opposing views, but the intergovernmental structures provide mechanisms for engagement, ensuring the governments come together to discuss issues in a constructive way.”10

Governance of England

Professor Gallagher’s view is that “one of the structural reasons why IGR outwith the devolved Administrations have been difficult is that 85 per cent of the UK does not participate in them.” He suggests that “England is very centralised, and Whitehall seeks to be the micromanager of 85 per cent of the country, and, funnily enough, it finds it difficult to be hands-off with the remaining 15 per cent.” In his view a “change in the governance of England is an essential precondition for effective IGR for the rest of the UK.”1

This issue was also raised by Professor John Denham who told us that it “is important to separate out the governance structures of the UK and of England. If we look at England, for example, there is no civil service structure that co-ordinates the development and implementation of policy in England.”2

In his view the “first step is to create a machinery of government for England that focuses on how England’s domestic policy is governed. As we do that, we can then become more explicit about what is an issue for England and where there are union-wide areas of concern.”2Professor McEwen suggests that this “would make it easier to know when the UK Government was acting for England—in its capacity as, in effect, a Government for England— and when it was acting as the UK Government, or acting for the union, as it were.” In her view “those Whitehall machinery aspects are key to reforming and improving the way that intergovernmental relations take place.”2

Dispute Resolution

The Committee notes that the formal dispute resolution process within the IGR structure does not appear to have been used despite a number of inter-governmental disagreements. The Committee invited the Cabinet Secretary and the UK Minister for Intergovernmental Relations to comment on why the process has not yet been triggered.

The Cabinet Secretary responded that robust dispute resolution processes “are a key part of the effective intergovernmental arrangements, but there will be uncertainty on how these non-binding mechanisms can have a meaningful effects in a situation without genuine, good faith commitment to respect inter-government processes.”1

The UK Minister for Intergovernmental Relations responded that disagreements “are considered at the lowest appropriate level possible and in most cases are resolved before escalation to ministerial level and the dispute resolution process.”2

The Chair of the Legislation, Justice and Constitution Committee, Welsh Senedd told us in relation to public disputes between the Welsh Government and the UK government – “Why are those not being tested through the committee structures that have now been set up as part of the intergovernmental machinery or through the dispute resolution procedure? When will they be tested?”3

Paul Cackette told us that the “referral to dispute resolution does not seem to provide an incentive for civil servants to work more closely together” and it “seems to me that there really is no incentive just now to make this work.” In his view parliamentary scrutiny “may, as much as anything, provide a cultural incentive to get it right in the first place” on the basis that civil servants “could be called to committee in a much more structured and developed way to explain why you have allowed certain things to happen and why intergovernmental co-operation has not worked may end up providing an incentive.”4

The Committee asked the Cabinet Secretary why the dispute resolution process does not appear to have been tested yet. He responded that what “I am not sure about—this is why the process is untested—is what the dispute resolution process would resolve, if the UK Government’s approach is to go through the formal processes but then, right at the end, to put down its trump card and say that it is invoking this or that measure in order to stop something. The UK Government has simply ruled that something is not happening.”5

A Statutory Basis?

Given the breakdown in trust and difficulties in shifting culture the Committee heard that consideration should be given to placing IGR structures on a statutory basis. As we noted in Part 1 of this report this argument predates the recent intergovernmental disagreements arising from the constitutional impact on devolution of the UK leaving the EU.

The House of Lords Constitution Committee has suggested that “Attitudes and behaviours need to change to make the new intergovernmental arrangements a success. If this does not happen, there may be a stronger argument for placing intergovernmental relations on a statutory footing. However, we are alive to the potential downsides of detailed statutory provisions resulting in political disagreements being settled in court rather than through political dialogue.1

Professor Rawlings told us that when “we were doing intergovernmental relations in the early years, it was clear that there was a problem, but my view was that the political culture around the operation of intergovernmental relations had to be improved.” But over the years, “I came to the view that the culture was not going to change.”2 In his view “there was profound ambivalence on the part of the UK Government as to the extent to which the other Administrations had a legitimate part to play in the governance of the UK” and without that “shared understanding of what the roles of the various Administrations could be, productive intergovernmental relations were not likely.”2

Consequently this “has led me to think that, at least at some level, you need a legal framework that requires the establishment of machinery for intergovernmental relations” given that “you may need law first and then the culture will follow rather than thinking that you should change the culture and then maybe do law.”2

While the Scottish Government acknowledges that the joint review of intergovernmental relations has “introduced some improvements” they “can only be effective if they are applied with good faith and integrity by all parties.” The Cabinet Secretary’s view is that legislation “would only improve this situation if it contained effective enforcement mechanisms and real sanctions” and “the real improvement needed is genuine commitment to operating IGR processes as intended, with integrity and good faith, and respect for all participants.”5

The Cabinet Secretary told us that there “should be a recognition that there is no hierarchy of Governments” and each one “should co-operate through negotiation and consensus using agreed intergovernmental processes such as common frameworks, instead of the UK Government centralising and imposing its views using the formal powers of the Westminster Parliament.”6

The Scottish Government has stated that—

“The devolution settlement preserved the sovereignty of the Westminster Parliament over the Scottish Parliament, but it did not create a parallel hierarchy of governments. In 1999 governmental functions and funding in devolved areas transferred to the Scottish Government, which has the experience, knowledge and responsibility for developing policy and allocating funding for devolved matters. The Scottish Government is accountable to the Scottish Parliament and people for these functions, not to the UK Government or Westminster Parliament.”7

The Welsh Government’s view is that “for devolution to work effectively, it requires consistently constructive co-operation and collaboration between the governments of the UK” and “we must renew the overall relationship between the UK and the devolved governments to one of shared governance in the UK.”8

It defines shared governance as “recognising the presumption of subsidiarity and shared sovereignty: it does not mean the UK government reaching into and duplicating matters which are the responsibility of the devolved governments.”8 The Welsh Government’s view is that “we hope that the Review and the package of reforms will be codified in a new MoU and, if all governments agree, underpinned in statute.”10

The UK Minister for Intergovernmental Relations in response to whether intergovernmental structures should be placed in statute stated that arrangements “must remain flexible enough to address the Government’s and devolved administrations’ interests at any given time.”11

The Committee notes that as stated by our Adviser, Professor Keating there is now “a complex landscape of intergovernmental mechanisms, which has grown incrementally rather than following from a clear constitutional design.”12 This complex landscape includes—

new intergovernmental structures and ways of working which replaces those in the MoU;

other elements of the MoU which have not been reviewed such as the Concordat on International Relations;

Common Frameworks: Definitions and Principles;

individual Common Frameworks;

a number of consent/consult mechanisms related to the use of delegated powers by UK Ministers in devolved areas.

The Committee’s view is that there is a lack of clarity and consistency with regards to how each of these mechanisms work together. For example, as we discuss below, the Common Framework principles include enabling “the functioning of the UK internal market, while acknowledging policy divergence.”13 The Review states that the new IGR structures and ways of working “will provide for ambitious and effective working, to support our COVID recovery, tackle the climate change crisis and inequalities, and deliver sustainable growth.” But there is no reference to the functioning of the UK internal market.

The common framework principles include to “ensure compliance with international obligations” and “ensure the UK can negotiate, enter into and implement new trade agreements and international treaties.” But the Welsh Government have stated that frameworks are “not intended to provide enhanced engagement on matters relating to the Trade and Cooperation Agreement, and the governance structures within it.”10 The Review provides for a “Trade IMG to discuss agreements with the UK’s new trading partners, and an IMG for the UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement.”15 It is also unclear how these new mechanisms work alongside the Concordat on International Relations.

The Committee also notes that given the Review only relates to new IGR structures and ways of working there does not appear to be any intergovernmental agreements in some areas of the new post-EU constitutional landscape. For example, as we discuss below, in relation to the use of delegated powers by UK Ministers in devolved areas.

In turn this has created significant challenges for each of the legislatures across the UK in carrying out their core legislative and scrutiny functions. For example, as highlighted by the Chair of the Legislation, Justice and Constitution Committee, Senedd Cymru, a consequence of poor intergovernmental working is that “the Welsh Government is not in a position to answer the questions that we put with sufficient timeliness and clarity and to the satisfaction of the Senedd.”16

The Committee recommends the need for a new Memorandum of Understanding and supplementary agreements between the UK Government and the Devolved Governments. This should specifically address how devolution now works outside of the EU and based on a clear constitutional design including consideration of the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality. This should be accompanied by new Devolution Guidance notes and other operational guidance notes.

Common Frameworks

The Institute for Government suggests that following the UK’s departure from the EU we “have been left with a big zone of regulatory uncertainty” which “has created a new need for greater co-operation between the Governments, new institutions and, to be frank, a new culture of shared governance.”1

To address this need for greater intergovernmental co-operation the principles for Common Frameworks were agreed in 2017.2 32 policy areas were identified as requiring frameworks. Of these one (Hazardous Substances: Planning) has been finalised and published and 29 have been provisionally approved by Ministers across the four governments and are operational. 27 of the provisional frameworks have been published, two have not and there are two areas in which work is still underway to develop a provisional framework.3 Of the 32 frameworks the Office for the Internal Market (OIM) notes that 16 are expected to interact with the UK Internal Market Act (UKIMA).3

The Scottish Government’s view is that Common Frameworks—

“offer an agreed means to manage regulatory divergence in a post-EU context: an intergovernmental mechanism based on collaboration and mutual respect. This is a model for a properly functioning internal market, where the relationship between a well-functioning market and the power to act autonomously in different territories – the founding purpose of devolution – is managed in a proportionate and balanced manner, recognising the importance of other devolved policy objectives such as health and the environment.”5

In a written response to the OIM the Scottish Government stated that Common Frameworks “provide a consensual model for managing divergence” that is “sufficient to manage practical regulatory and market impacts in devolved areas” which may result from the UK's withdrawal from the EU.3

The Welsh Government in its response to the OIM “commented positively on the potential of Common Frameworks, stating that they ‘aim to manage divergence effectively and have a profound impact on the functioning of the internal market’”3The UK Government’s view is that Common Frameworks “are the right place to for discussing UK internal market (UKIM) related divergence within their scope, including exclusions to the Market Access principles.”8

The Committee also notes that both the UK government and devolved governments agree that where Common Frameworks are operating they are the right mechanism for discussing REUL reform in the areas they cover.9

Operational Impact

As part of our inquiry we considered how Common Frameworks have been operating to date including consideration of the work of the OIM. The Committee notes that Common Frameworks were initially intended to provide “a common UK, or GB, approach and how it will be operated and governed. This may consist of common goals, minimum or maximum standards, harmonisation, limits on action, or mutual recognition, depending on the policy area and the objectives being pursued.”1

However, the evidence we heard suggests that the focus is on process and ways of working rather than policy substance. In a periodic report published in March 2023 the OIM stated that “the majority of activity under Common Frameworks to date has been routine intergovernmental working.”2

The Institute for Government told us that there “has been a lot of positive progress on common frameworks development” and “they are serving to facilitate a lot of interaction in a slightly more structured way between officials working in these technical, regulatory areas where there is a need for an information-sharing and evidence-gathering analysis of whether rules brought in in one part of the UK might have negative effects elsewhere.” Professor McEwen’s view is that “there has been an attempt to depoliticise” common frameworks “and make them quite technical, but the technical can very quickly become political.”3

Some of our witnesses pointed out that frameworks do not appear to have been used in the way that was initially intended. Professor McHarg told us that they “were envisaged as a sort of harmonisation process. That would be the context in which you would decide when it was necessary to have a common set of rules and when divergence was acceptable.” However, they “are all a lot vaguer and more process-oriented, rather than substantive, than they might otherwise have been.”4

Professor McEwen’s view is that at “the outset there was an expectation that they would lead to common regulatory approaches in a sense, whereas they are not doing that now. In the main, they are more about ways of working and engagement.” Our Adviser, Professor Keating’s view is that while Common Frameworks provide a distinct model for joint working there “is no common format and Frameworks variously provide for agreed measures of divergence and joint policy making.”5 Professor McEwen told us “I always thought that the principles were sufficiently ambiguous to get the players to work together but that they were going to be difficult to operate in practice.”3

The Welsh Government told the OIM that Common Frameworks “have only needed to manage a small amount of regulatory difference to date, and it is too early to draw substantive conclusions about their impact.”2 The UK Government’s view is that as frameworks “become increasingly a business-as-usual way of working they are used more and more for clear communication between the parties to the Framework at, and between, each stage of the decision-making process.”8

SPICe have highlighted that “in the absence of a formal and operational process for reporting to legislatures, the only routes to information on how frameworks are operating is through the discretionary disclosure or publication of information by the four governments of the UK.”9 For example, the Cabinet Secretary for Rural Affairs and Islands told the Rural Affairs, Islands and Natural Environment Committee on 2 November 2022 that the UK Government’s Genetic Technology (Precision Breeding) Bill was published without any prior discussion through the common frameworks process—

“The process should have been used for that but, instead, it started the other way round. The bill was published without discussion having taken place with the other Administrations in the UK.”

Interaction with the UK Internal Market Act 2020 (UKIMA)

A number of our witnesses raised concerns about the impact of the market access principles established in UKIMA on the operation of Common Frameworks. The Institute for Government told us that UKIMA “cut across the whole common frameworks programme in creating the market access principles that limit the scope for effective divergence.”1

Professor Rawlings told us that UKIMA “cut straight across” common frameworks “which were designed explicitly to manage the possibility of regulatory divergence and to provide machinery for discussion of prospective divergence mechanisms to deal with possible disputes and so forth.” Furthermore, “whereas the common frameworks proceeded on the basis of a collaborative understanding of how the internal market should be managed, the internal market bill represented a directive approach from the centre as to how internal markets should work.” In his view “the question is the extent to which the common frameworks can survive as a mechanism to provide for regulatory divergence.”2

Philip Rycroft told us that we “had a mechanism, through the common frameworks, to deal with domains where there were cross-border issues and where divergent regimes might have caused problems either side of borders. I have yet to see any evidence that suggests that the common frameworks would not have been adequate to deal with those issues. In that context, the 2020 act was a step too far.”2

Professor Gallagher’s view is that UKIMA “was an error and that it would have been possible to deal with questions of regulatory divergence and that, in practice, it will be possible to deal with such questions, if there is the political will to do so between the respective Governments.”2

The Scottish Government’s view is that UKIMA “has major flaws both as a mechanism for managing the UK’s internal market and in its interaction with the devolution settlement.” With regards to managing the UK internal market, Common Frameworks “offer an agreed means to manage regulatory divergence in a post-EU context: an intergovernmental mechanism based on collaboration and mutual respect.”5

In contrast, UKIMA “imposes a rigid statutory model based solely on the market access provisions, with very limited exceptions, and without the key features of effective internal markets, such as proportionality and subsidiarity.”5

With regards to how UKIMA intersects with the devolution settlement the Scottish Government’s view is that UKIMA “is in effect a new, wide-ranging constraint on devolved competence, cutting across the reserved powers model, that potentially goes further than existing constraints on legislative or executive competence in the Scotland Act 1998, and is unclear and unpredictable in effects.”5

The Scottish Government indicated to the OIM that UKIMA poses a risk to the effective operation of Common Frameworks by casting them as “potentially disruptive to the internal market”, rather than as a means to enable the functioning of the internal market by managing divergence.8

The Scottish Government’s position is that UKIMA “should be repealed as a whole given these fundamental flaws in its design and its damaging effect on the devolution settlement.”5

The UK Government has indicated to the OIM that it has “no specific concerns with the operation” of the market access principles. It cited the referral of the proposed ban on peat in horticultural products in England to the OIM as an example of how the principles had informed policy consideration.8

The Welsh Government indicated to the OIM that it did not recognise the effect of the market access principles on the legislative competence of the Senedd but as they “have only been in operation since the Act came into force, there had been limited opportunity to assess their effect on the policymaking of the four nations.”8

Impact on Business

The Committee also considered the functioning of the UK internal market including Common Frameworks from a business perspective. Philip Rycroft told us that “management of an internal market is important. Divergence can be expensive for businesses, disrupt supply chains and, ultimately, reduce choice for consumers.”Consequently, “we must understand the commercial reality of how internal markets function and how business can flow through an internal market with a minimum of hinderance in order to deliver goods and products across it and, ultimately, prosperity for everybody in it.”1

Therefore, “when looking at possible divergence, part of the equation has to involve considering what divergence would mean for the effective delivery of business on both sides of the border.” From his point of view, we do that successfully through negotiation, “as happens through the common frameworks.”1

The OIM has found that awareness of the market access principles “among businesses is generally very low.” At the same time though there “has been little new regulatory difference between UK nations since the internal market regime was established and the majority of businesses trading in the UK do not experience challenges when selling to other UK nations.” In that context, the OIM found that low awareness of the market access principles suggests that businesses have not needed to rely on them to support intra-UK trade and this reflects the fact that most businesses continue to trade freely across the UK.3

The OIM has also found that awareness of common frameworks “among external stakeholders, such as businesses and trade associations, is low and that those who are aware indicated they “did not know what topics were being discussed or whether there are opportunities for them to input into those discussions.” They also noted that evidence to parliamentary committees indicates that businesses have concerns “about the lack of a role, formal or informal, for non-governmental stakeholders in many Common Frameworks.”3

The OIM’s view is that in “order for policy officials to identify and manage the potential effects of regulatory differences on the UK internal market, they require a good understanding of what these effects might be. Stakeholder engagement can help to inform this understanding.” They suggest that a “proactive approach to explaining the role of Common Frameworks, how they operate and what topics are currently under discussion would increase the likelihood of stakeholders engaging effectively and providing useful insights.”3

Process for considering UKIMA exclusions in Common Framework areas

Under sections 10 and 18 of UKIMA, UK Ministers may make regulations which change what is excluded from the application of the Act’s market access principles. Although only UK Ministers have the power to make changes, the UK and devolved governments have agreed a process for the consideration of exclusions in areas covered by common frameworks.1

Reporting

We invited both the Cabinet Secretary and the UK Minister for Intergovernmental Relations to provide an update on progress in delivering appropriate levels of reporting on the operation of Common Frameworks and on the process for considering exclusions to UKIMA.

The UK Minister for Intergovernmental Relations stated that an annual report will be provided for each Common Framework once these have been fully implemented. However, as noted earlier in this report only one Common Framework has been fully agreed and there has been no reporting on the operation of the other frameworks. With regards to the transparency of the process to consider exclusions to UKIMA, the UK Minister states that these “discussions are no less transparent than any of the other Frameworks discussion.”1

Professor McEwen told us that “although there is transparency around what the frameworks are, it is much more difficult to see how they are operating in practice.”2 Professor McHarg noted that the process to consider exclusions is not statutory and “there is always a problem with accessibility, transparency and intelligibility when things are not contained in statutes.” She also pointed out that “concerns about accessibility, participation, transparency and accountability are inherent to intergovernmental negotiations and are inherently difficult to address.”3

The Committee welcomes the commitment by the Cabinet Secretary in response to our report on the UK Internal Market that where “an exclusion from the provisions of the UK Internal Market Act is necessary to ensure the policy effect of devolved legislation, that will be made clear by the Scottish Government to the Scottish Parliament, in order to allow for proper consideration of the exclusion by interested parties.”4

The OIM stated in March 2023 that we “would encourage transparency both between the governments and with external stakeholders such as businesses and third sector organisations about future regulatory developments that may engage the MAPs and intersect with Common Frameworks.”5

The OIM “note the UK Government’s commitment to update the Common Frameworks page on GOV.UK and to include updates on Common Frameworks in quarterly intergovernmental transparency reports.” They suggest that a “proactive approach to explaining the role of Common Frameworks, how they operate and what topics are currently under discussion would increase the likelihood of stakeholders engaging effectively and providing useful insights.”5

The Committee notes that there appears to be a consensus among the UK Government and the Devolved Governments that Common Frameworks provide the right mechanism to manage regulatory divergence within the UK internal market. However, we also note there are a number of issues which need to be addressed in relation to how frameworks have been operating to date—

There is a lack of clarity around purpose with little evidence that frameworks are delivering common goals, maximum or minimum standards or harmonisation as initially intended;

Rather, as highlighted by the OIM, the majority of activity has been routine intergovernmental working;

At the same time there have been some significant examples of regulatory divergence which raise questions around the role of frameworks in discussing exclusions from the market access principles and how these discussions feed into the process for considering exclusions;

The role of business and other stakeholders in the process and the role of parliament(s) in holding Ministers to account must be part of the wider framework process;

The low level of awareness of frameworks among business and other stakeholders.

The Committee’s view is that there needs to be much greater clarity around how regulatory divergence will be managed through the Common Frameworks programme. In particular, there needs to be clarity around how the market access principles are intended to work in those circumstances.

The Committee also notes that since the Common Frameworks: Definition and Principles were published in 2017 there has been a significant shift in the constitutional landscape including the introduction of UKIMA 2020 and Retained EU Law (Revocation and Reform) Act 2023.

The Committee’s view is that there is, therefore, a need to rearticulate the definition and principles of frameworks both in the light of experience to date and the new constitutional landscape.

The Committee recommends that the new MoU discussed earlier in this report should include a supplementary agreement on Common Frameworks including clarity around—

the extent to which this approach is based on a new culture of shared governance involving joint policy making or co-design or whether it is largely about managing routine intergovernmental activity;

the purpose of frameworks;

the relationship between discussion of market access principle considerations in frameworks and the decisions made in the process for considering exclusions to the market access principles;

the role of business and other stakeholders in the frameworks process and in the process for considering exclusions from the market access principles and the role of parliament(s) in holding Ministers to account;

the relationship between the dispute resolutions process in individual frameworks and the formal dispute resolution process available to governments through the IGR structure, including how these are intended to work given this has yet to be tested;

reporting mechanisms both in relation to the operation of frameworks and the process for considering exclusions to the market access principles.

Sewel Convention

As the Committee has previously noted, whereas the Sewel Convention worked well prior to the decision to leave the EU, there has subsequently been considerable and continuing disagreement between the UK Government and the devolved governments and parliaments regarding its effectiveness.

The Committee has stated previously that the Sewel convention is “under strain” following the UK’s departure from the EU. Although the Scotland Act 2016 gave statutory recognition to the convention, this did not alter its status and it did not become judicially enforceable. There continues to be considerable debate as to whether it should be strengthened in law and subject to judicial review or whether it can be strengthened on a non-statutory basis or whether no strengthening is required.

The Committee has heard that the former would primarily involve removing the reference to the UK Parliament not “normally” legislating without consent from section 28(8) of the Scotland Act 1998 and making it a binding legal rule. The latter would primarily involve the reform of parliamentary procedures at Westminster requiring greater Ministerial accountability and more detailed scrutiny of decisions to proceed without the consent of the devolved legislatures.

Professor McHarg’s view is that “strengthening the Sewel convention is fundamental, because, unless there is some protection for the devolved institutions against the unilateral exercise of Westminster sovereignty, there are no guarantees of anything.” She told the Committee that “we need to try to get back to the situation that we were in pre-Brexit, in which parliamentary sovereignty still existed in principle, but its operation in practice was constrained.”1

Professor Denham’s view is that had “we attempted to do devolution when the UK was already outside the EU, nobody would have invented the Sewel convention, because nobody would have believed that something as inadequate, flexible or ambiguous as the Sewel convention would have been adequate for resolving the disputes that necessarily would arise in UK domestic policy outside the EU.”2

Professor Gallagher told us that UKIMA was a breach of the Sewel convention which in his view was “an error of constitutional significance” and the “consequence of that intervention and a couple of other interventions by recent UK Governments leaves the argument for strengthening the Sewel convention unanswerable.”3

On this basis, Professor Gallagher proposes that Sewel “should now be given full statutory force, so that no law can be made or have effect which alters devolved law or powers unless the consent of the devolved legislature has been secured.” He also notes that this idea has been accepted by the UK Labour Party’s Commission on the future of the UK which recommends—

“there should be a new, statutory, formulation of the Sewel convention, which should be legally binding. It should apply both to legislation in relation to devolved matters and, explicitly, to legislation affecting the status or powers of the devolved legislatures and executives. It should not be restricted to applying “normally”, but should be binding in all circumstances.”4

The chair of the Senedd’s Legislation, Justice and Constitution Committee told us that Sewel “as it exists currently is out of date because of the extent to which what is not normal is becoming normal.” He points out that there “is now a high degree of scepticism in the Senedd and in Wales about whether the Sewel convention is functioning properly.”5 In his view –

“When what is not normal becomes more routine, the devolved institutions—especially the devolved Parliaments—wonder what the debate is and why, when they say that they do not consent and produce evidence for why there should not be consent, that is just bypassed. In effect, scrutiny is transparent but totally ineffectual. We would like something more formal to be put in place.”5

The Chair of PACAC told us with regards to the 'not normally’ provision within Sewel that “one has to question whether we have been living in normal political times. I contend that we have not. Whatever one’s view on the outcome of the referendum on the EU, it has been seismic, and its institutional implications are seismic. We must look at it in that context.”5

This Committee also recognises that there continues to be many instances where the devolved legislatures consent to the UK Government legislating in devolved areas through the legislative consent process. This includes in some areas related to leaving the EU. The Committee therefore explored with witnesses the extent to which Sewel is under strain primarily as a consequence of political disagreements.

The Chair of PACAC pointed out that at the outset of devolution there were Labour Governments in the UK, Wales and Scotland and, therefore, “I suspect that practical working relationships were, on the whole, better than they might have been had the Administrations been headed by different political parties.” His own view “is that I favour a political rather than a legal resolution to the problem.”5

The Committee wrote to both the Cabinet Secretary and UK Minister for Inter-Governmental Relations asking whether they agree that the Convention is under strain. We also asked whether, and how, it could be strengthened in law and be subject to judicial review or whether, and how, it could be strengthened on a non-statutory basis.

The Cabinet Secretary’s response stated that “a convention which can be observed or not by the UK Government, as it chooses, cannot provide any security to the Scottish Parliament that its responsibilities or views will be respected.” He also referenced the Scottish Government’s previous proposals for how the Convention “could be properly put on a legislative footing.”9

Those proposals included “a draft clause” which if enacted would provide that the UK Parliament “must not pass Acts applying to Scotland that make provision about a devolved matter without the consent of the Scottish Parliament.”10 The clause makes it clear that this provision would apply to legislation in a devolved area; changing the legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament; and changing the functions of the Scottish Government. It also includes a duty on UK Ministers to consult the Scottish Government on Bills applying to Scotland.

The Cabinet Secretary told us that the “pre-eminence of the Scottish Parliament to decide on devolved matters should be restated, although we still have to acknowledge Westminster’s continued claim to sovereignty on all matters.”11

The Minister for Intergovernmental Relations states in his response that the UK Government “is committed to the Sewel Convention and has no plans to alter its status.”12 He adds that “the instances where the Government has proceeded without legislative consent have been limited – these are, after all, not normal” and “have generally related to EU Exit” and “international policy”.12

The Minister also states that “it is sometimes necessary for the UK Government to act in its role as the government for the whole of the UK and introduce legislation that works to ensure coherence across the UK.” In his view this is “consistent with the Sewel Convention and indeed the overarching devolution settlements.”12 The UK Minister for Housing and Homelessness in a written response to the Committee also stated that “it is necessary that the UK Government can fulfil the role of the UK's national government.”15

The Welsh Government’s view on Sewel was set out by the Minister for the Constitution and Counsel General in a written statement after the Inter-Ministerial Standing Committee (IMSC) on 17 May 2023. He stated that “the UK Government needs to rediscover its respect for devolution and reverse the position whereby breaches of the Sewel Convention have become the default.”16

Ahead of a speech to the Constitutional and Administrative Law Bar Association’s annual conference on 1 July 2023 he also stated that despite “our efforts to work collaboratively, the UK government has chosen a centralised, unilateral and destructive approach to the devolution settlement” and “has repeatedly pushed ahead with legislation in devolved areas without the consent of the Senedd.”17

He also told the Senedd’s Legislation, Justice and Constitution Committee on 10 July 2023 that “in the last 18 months or so, we’ve had eight or nine major breaches of Sewel, or potential breaches of Sewel.” In his view the core of the problem is that “we don’t have a common position any more” and there is “a normalisation of breaching Sewel, that Sewel is something you seek to achieve rather than something that has a constitutional status that has to be complied with.”18

The Welsh Government’s view is that the ‘not normally’ requirement within Sewel “should be entrenched and codified by proper definition and criteria governing its application, giving it real rather than symbolic acknowledgement in our constitutional arrangements.” Another option is that “a new constitutional settlement could simply provide that the UK Parliament will not legislate on matters within devolved competence, or seek to modify legislative competence or the functions of the devolved governments, without the consent of the relevant devolved legislature.”19

Professor Michael Keating, notes that there have been various suggestions to make Sewel more, if not totally, binding as follows—

The word ‘normally’ be removed from the wording in the Scotland Act;

The conditions under which Westminster can over-ride refusal of consent could be specified clearly, rather it being invoked ad hoc;

There could be a body to consider the justification for over-riding the refusal of consent and issue a report. Although this could only be non-binding, it would force governments to provide a justification;

There could be a requirement for affirmative support in both Houses of Parliament. The non-elected status of the House of Lords could prove an obstacle to this but it features in some proposals for an elected second chamber.

The Committee notes that there is clearly a fundamental difference of viewpoint between the UK Government and all the devolved governments with regards to how the Sewel Convention has been operating since EU-exit. It is also clear that this has led to a deterioration in relations between the UK Government and all the devolved Governments.

The Committee’s view is that this level of disagreement on a fundamental constitutional matter is not sustainable particularly within the context of an increasing shared space at an intergovernmental level.

The Committee notes the view of UK Ministers that “it is sometimes necessary for the UK Government to act in its role as the government for the whole of the UK” and that “it is necessary that the UK Government can fulfil the role of the UK's national government”. The Committee is unclear what “necessary” means within this context and notes that this is not stated within either the MoU or the Devolution Guidance notes. It is also unclear how “necessary” relates to “not normally” and what the threshold is for necessity in justifying overriding devolved consent.

The Committee further notes that in December 2016 it was said [on behalf of the then UK Government in the Supreme Court] that the UK Government considered the Sewel Convention to be “essentially a self-denying ordinance" on the part of the UK Parliament.20 The Committee will invite the UK Minister for Intergovernmental Relations to clarify whether this remains the view of the UK Government.

The Committee also notes that the MoU states that the “UK Government represents the UK interest in matters which are not devolved in Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland.”21 There does not appear to be any reference in the MoU to the UK acting in its role as the government for the whole of the UK.

It is essential that we have the opportunity to hear from the UK Minister for Intergovernmental Relations to discuss the findings of this report and his written response to our previous letter.

Delegated Powers

The Committee has previously noted that there has been a significant step change in the approach to the use of delegated powers during the preparations for EU-exit and after EU-exit. Our view is that “the extent of UK Ministers’ new delegated powers in devolved areas amounts to a significant constitutional change. We have considerable concerns that this has happened and is continuing to happen on an ad hoc and iterative basis without any overarching consideration of the impact on how devolution works.”1

The Hansard Society points out that delegated powers for UK Ministers in devolved areas “are being sought, granted and used – and also questioned – increasingly often, in large part because of the repatriation to the UK of policy-making in devolved areas that were previously governed at the EU level.”2

We invited the views of the Cabinet Secretary and the UK Minister for Intergovernmental Relations on the impact on devolution of the increasing conferral of powers on UK Ministers to make secondary legislation within devolved competence.

The Cabinet Secretary responded that “the increasing conferral of powers for UK Ministers to act in devolved areas is an important constitutional development which requires careful consideration, particularly to ensure that the responsibilities of the Scottish parliament are properly respected.”3

He notes that, prior to the decision to leave the EU, and other than the transposition of EU obligations, the use of SIs to legislate in devolved areas “happened rarely.” He further notes that “there is no equivalent of the Sewel Convention for secondary legislation, so the effect is that the Scottish Parliament loses its ability to formally scrutinise and agree to legislative action within its areas of competence.”3

The UK Minister for Intergovernmental relations appears to take a different view about the extent of change. In his response he states that the use of SIs “in devolved areas are not new and have been used across a wide range of policy areas since the advent of devolution.”5 This is consistent with a previous response we received from the UK Minister for Housing and Homelessness dated 20 March 2023 which stated that this approach of seeking the consent of Scottish Ministers, “when there is a statutory requirement or an existing political commitment to do so” is viewed as having “worked well for over 20 years” and “consistent with long standing practice.”6

As part of this inquiry the Committee heard evidence, including from the chairs of constitution committees in other UK legislatures, about the increasing conferral of powers on UK Ministers to make legislation within devolved competence. The Chair of the House of Lords Constitution Committee told us—

“A big issue that put stress on the devolution settlement was that, when that settlement was first concluded, secondary legislation was used largely to implement EU laws and directives but, once Brexit happened and there was going to be a huge repatriation of powers from the EU, secondary legislation started to be used to do many more things than might have been anticipated at the point of the devolution settlement.”7

The view of the House of Lords Constitution Committee is that leaving the EU “has brought a whole new dynamic” and this “brings with it a need to raise the bar on transparency, scrutiny and how intergovernmental working and the integrity around seeking consent operate.”7

Table 1 below sets out the key differences in the use of delegated powers by UK Ministers in devolved areas before and after EU-exit.

| Before EU-exit | After EU-exit | |

| Number of delegated powers | Limited: section 2(2) of the EC Act 1972 read with section 57(1) of the Scotland Act 1998 and a few other powers, mainly listed in and under the Scotland Act 1998.i | Numerous delegated powers within UK Acts and amended in to retained EU law. |

| Policy areas | By far the most commonly used power was section 2(2) which only applied to subject areas within EU competence | Still mainly in former EU policy areas, but increasingly in other policy areas too. |

| Scope | The scope of the section 2(2) power was limited to the implementation of EU obligations, with some limited flexibility to go beyond minimum standards required by EU law. | Section 2(2) no longer applies and much more policy choice for UK and Scottish Ministers. |

| Role of UKG and Devolved Ministers | SG could ask UKG to implement EU obligations in devolved areas. This decision was for Scottish Ministers. | Varying degree of statutory and non-statutory requirements for UK Ministers to seek the consent of or consult with Scottish Ministers. |

| Non-codified agreements and guidance |

| |

| Parliamentary Scrutiny | SG provided regular reports to the Scottish Parliament on the implementation of EU obligations in devolved areas including at a GB/UK-wide level. | Statutory Instrument Protocol 2 (parliament.scot) |

We consider these key differences in more detail below.

Number of Delegated Powers

The Committee notes that one of the most striking aspects of how devolution is changing outside of the EU is the extent of primary legislation enacted at Westminster which includes delegated powers exercisable within devolved legislative competence by UK Ministers. While this mostly relates to policy areas previously within the competence of the EU there is also a significant number of powers for UK Ministers conferred in subject areas that were not formerly governed by the EU.

The extent of this change is illustrated in the table provided at Annexe B which provides examples of new delegated powers exercisable within devolved competence by UK Ministers which are contained in UK Parliament Acts and Bills. All of these were subject to the Legislative Consent process in the Scottish Parliament during Session 6. This includes the following UK Acts and Bills—

Environment Act 2021

Professional Qualifications Act 2022

Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022

Health and Care Act 2022

Building Safety Act 2022

Economic Crime (Transparency and Enforcement) Act 2022

UK Infrastructure Bank Act 2023

Retained EU Law (Revocation and Reform) Act 2023

Northern Ireland Troubles (Legacy and Reconciliation) Act 2023

Energy Bill

Levelling-up and Regeneration Bill

Procurement Bill

Data Protection and Digital Information (No. 2) Bill

Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Bill

Electronic Trade Documents Act 2023

The above list is in addition to a number of UK Acts that also include delegated powers exercisable within legislative competence by UK Ministers and which were subject to the legislative consent process during Session 5 of the Scottish Parliament.

As the Committee has previously noted, a huge number of new delegated powers of this kind were also created during the EU exit “deficiency-correcting” process, when powers that had been exercisable by EU institutions, e.g., the European Commission, were conferred on Scottish and/or UK Ministers. These powers are not contained within Acts of Parliament but within the body of domestic legislation known as “retained EU law”.1

The Committee notes that the volume of new powers demonstrates the significantly increased complexity of the constitutional landscape.

Policy Areas

Before the EU exit process, by far the most commonly used power for UK Ministers to make regulations within devolved competence was the power in section 2(2) of the European Communities Act 1972.i This power could only be used in subject areas that were within EU competence. Post-EU, the majority of the new powers are still mainly within former-EU subject areas, but increasingly powers are being conferred in other subject areas which were not within EU competence. Examples are in the list above.

Scope

The section 2(2) power was available only for the purposes of complying with EU obligations, and therefore with policy that had already been determined at the EU level.

Given that EU law is subject to its own legislative processes and there was limited room for policy divergence there was less of an issue whether domestic legislation was enacted in the UK Parliament or the Scottish Parliament.

In contrast without the obligation to comply with EU law there is much more policy choice for Ministers including the possibility of increased intra-UK regulatory divergence (not withstanding the practical effects of common frameworks and the UKIMA) and the likelihood of increased divergence from EU law.

Now that policy is being determined at a domestic level rather than simply implementing policy that has been pre-determined and already scrutinised at the EU level, the scrutiny that the domestic legislation receives within the UK is much more important, and accordingly it is much more of an issue whether the policy (and the secondary legislation which gives effect to it) is scrutinised in the UK Parliament or the Scottish Parliament.