Post-Legislative Scrutiny in the Scottish Parliament in Session 6: A Strategic Priority

During Session 6 of the Scottish Parliament, post-legislative scrutiny was declared to be a strategic priority. This briefing provides an evaluation of the post-legislative scrutiny undertaken by committees during Session 6. It highlights the full post-legislative scrutiny inquiries undertaken by committees (i.e. where a formal inquiry was followed by a written report), as well as innovative approaches that have been trialled. It concludes with a summary of findings from a survey of MSPs and officials on their engagement with post-legislative scrutiny during Session 6.

Summary

This briefing presents the results of a research project into post-legislative scrutiny in the Scottish Parliament carried out by Dr Tom Caygill (Senior Lecturer in Politics, Nottingham Trent University) as part of the Scottish Parliament's Academic Fellowship programme. It is based on an analysis of a survey of MSPs and officials as well as interviews with officials on certain committees which undertook post-legislative scrutiny in innovative ways during Session 6. The views expressed in this briefing are the views of the author, not those of SPICe or the Scottish Parliament.

Post-legislative scrutiny is a process whereby parliaments can review and evaluate the effectiveness of laws after they have been in force for a period of time. Post-legislative scrutiny is an important tool for the Scottish Parliament to monitor the implementation and effectiveness of the legislation that it passes. During Session 6, post-legislative scrutiny was declared to be a strategic priority by the Conveners Group in order to improve the conduct of such scrutiny during the session.

In total eight full inquiries have taken place (up to June 2025) and a further five post-legislative innovations have taken place, whereby committees have experimented with their approach to such scrutiny in order to fit it into their work programmes. This flexibility in approach, beyond full post-legislative scrutiny inquiries, has enabled more subject committees to engage with post-legislative scrutiny than in previous sessions, despite a heavy legislative workload.

The post-legislative innovations are documented in the case studies and form a central part of this briefing. All of the documented innovations were found to have been meaningful and are replicable within the Scottish Parliament and, in some cases, they are replicable externally as well. They show that it is possible to embed post-legislative scrutiny into pre-existing mechanisms to ensure that it becomes part of the everyday activity of the Parliament. They have also highlighted the benefits that engaging the public in the process can have, especially for a form of scrutiny that can sometimes be viewed as technical and dull.

The survey of MSPs and officials has provided insight into the support that post-legislative scrutiny has within the Parliament as well as some of the key challenges that remain (time, capacity and support). Overall, the strategic priority has been a success in encouraging more committees not only to engage with post-legislative scrutiny but also to innovate with their approach to it. Furthermore, it has been a success in building and retaining support for post-legislative scrutiny among MSPs and officials.

In order to drive post-legislative scrutiny forwards, the following recommendations are made:

Conveners Group to retain post-legislative scrutiny as a strategic priority for one further session.

Conveners Group to consider how the best practice identified in this report and by the working group on post-legislative scrutiny can be best shared with committees across the Parliament.

Committees to be encouraged to include lines of questioning relating to the current legislative landscape into Stage 1 scrutiny (where appropriate) going forwards.

Committees to be encouraged to engage more with post-legislative review.

Committees to be encouraged to move forward with candidates for post-legislative scrutiny at the start of a new session when the legislative workload is lighter.

Conveners Group to encourage current committees to include candidates for post-legislative scrutiny in their legacy reports.

Consideration to be given to producing a post-legislative scrutiny toolkit to support committees in Session 7.

The working group on post-legislative scrutiny to be expanded.

Post-legislative scrutiny in Session 6: context

What is post-legislative scrutiny?

Post-legislative scrutiny is defined as ‘a broad form of review, the purpose of which is to address the effects of legislation in terms of whether intended policy objectives have been met and, if so, how effectively' (Law Commission of England and Wales, 2006)1. Post-legislative scrutiny therefore has two distinct functions. First, there is a function relating to monitoring the implementation of legislation. Second, there is an evaluation function relating to whether or not the aims of an Act are reflected in the results and effects of legislation once implemented2.

One of the most important roles of the Scottish Parliament is to scrutinise and pass laws which are fit for purpose. However, there is an increasing role for parliaments in reviewing the impact and effectiveness of the laws they pass. The need for post-legislative scrutiny arises out of concerns expressed that parliaments (not just the Scottish Parliament) are not doing enough to assess the effectiveness of legislation once it has become law, given the volume of legislation they now have to deal with and the limited amount of time they have to reflect on legislation already passed.

Context

In Session 5, the Scottish Parliament identified that there was scope for further improvement with regards to how it undertook post-legislative scrutiny. As a result, the Parliament decided that the Public Audit Committee should have post-legislative scrutiny added to its remit3. This meant that the committee was given the specific task of considering previous Acts of the Scottish Parliament to determine whether they had achieved their intended purpose. However, adding post-legislative scrutiny to the remit of the Public Audit Committee did not mean that other subject committees were prevented from launching their own inquiries. The operation of this approach in Session 5 was evaluated as an earlier part of this academic fellowship.

In Session 6, a decision was taken to return the operation of post-legislative scrutiny to subject committees, where responsibility lay before the changes in Session 5. However, given concerns that post-legislative scrutiny hadn't really taken on much of a form in previous sessions, the Conveners Group decided to make post-legislative scrutiny one of its four strategic priorities during Session 64.

What is a strategic priority?

In practice, the establishment of post-legislative scrutiny as a strategic priority meant it was identified as an area where the Conveners Group could bring improvements to the Parliament's scrutiny role4. As part of the strategic priority, a working group on post-legislative scrutiny was established; it reports regularly to the Conveners Group to identify barriers to post-legislative scrutiny work and ways in which it could be carried out more easily4. To this end, the Parliament has welcomed innovations in post-legislative scrutiny during the course of this session, beyond the typical committee inquiry and report that was the focus of Session 5’s work. During research on post-legislative scrutiny in Session 5, time and capacity were noted as key issues facing committees when undertaking post-legislative scrutiny. As such there was a need to allow committees to be flexible in their approaches and to report on their post-legislative scrutiny work to the Conveners Group. The establishment of post-legislative scrutiny as a strategic priority has raised its profile and importance. This has been illustrated by the variety of committees engaging with the process in this session. In addition, a dedicated space has been created on the Parliament's website to highlight the work of committees across the Parliament.

Post-legislative scrutiny in Session 6: overview

Post-legislative scrutiny in Session 6 has taken a number of forms, the most frequent of which is a formal inquiry followed by a written report. For the purposes of this briefing, this is described as a full post-legislative scrutiny inquiry. The term 'full' denotes inquiries which were dedicated solely to post-legislative scrutiny, which were reviewing either part of an Act, a full Act or a number of complimentary Acts.

This approach has been undertaken by committees which have been able to find time for a larger piece of post-legislative scrutiny within their work programmes. For the purposes of this briefing, we will not be evaluating those inquiries in depth as the analysis of that approach was addressed in great detail in the research briefing on Session 5. However, we will acknowledge the range of full inquiries undertaken.

| Committee | Act of the Scottish Parliament |

|---|---|

| Criminal Justice Committee | Domestic Abuse (Scotland) Act 2018 |

| Economy and Fair Work Committee | Procurement Reform (Scotland) Act 2014 |

| Health, Social Care and Sport Committee | Social Care (Self-directed Support) (Scotland) Act 2013 |

| Local Government, Housing and Planning Committee | Community Empowerment Act 2015 (Part 2) |

| Local Government, Housing and Planning Committee | Community Empowerment Act 2015 (Part 9) |

| Social Justice and Social Security Committee | Child Poverty (Scotland) Act 2017 |

| Education, Children and Young People Committee | Education (Additional Support for Learning) (Scotland) Act 2004 |

| Equalities, Human Rights and Civil Justice Committee | British Sign Language (Scotland) Act 2015 |

As of June 2025, eight full post-legislative scrutiny inquiries have been undertaken by committees. The Local Government, Housing and Planning Committee has undertaken two inquiries into two different parts of the Community Empowerment Act 2015. This builds upon the work of its predecessor committee, which reviewed Parts 3 and 5 of the Act. Without a dedicated committee undertaking post-legislative scrutiny and alongside the Conveners Group strategic priority, a wider range of subject committees have engaged with full inquiries. In Session 5, only three subject committees engaged with full inquiries. In the current session, seven committees have now done so.

There is still potential for further post-legislative scrutiny as the current session comes to a close; and two committees have listed post-legislative scrutiny as potential future work. The Health, Social Care and Sport Committee has listed post-legislative scrutiny of the Health and Care (Staffing) (Scotland) Act 2019 as a potential future piece of work. This would be their second full inquiry this session. The Standards, Procedures and Public Appointments Committee has also listed post-legislative scrutiny of the Lobbying (Scotland) Act 2016 as a potential piece of future work. There is also the potential for the Net Zero, Energy and Transport Committee to undertake a full inquiry of the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009, after establishing a People's Panel to engage the public with section 91 of the Act. Although full inquiries have not been possible so far on the Acts listed above, some preparatory work has been undertaken on two of them which will be discussed in more detail later, in the case study section of the briefing.

This briefing does not assess the acceptance of post-legislative scrutiny recommendations by the Scottish Government. However, it is possible to look to the results of the appraisal of committee outputs in Session 5 to understand the type and strength of recommendations that committees have provided in the past, as well as the extent to which recommendations were accepted by the Scottish Government. 85% of recommendations called for either changes in policy or practice (43%), further research and reviews to be undertaken (25%) and the disclosure of information (17%). 60% of the 253 recommendations studied in Session 5 were accepted by the Scottish Government, either in part or in full. This is a higher level of success than in Westminster. It is also worth noting that just because an incumbent government does not accept recommendations in its response initially, this does not mean that: a) the same government won't implement them later down the line, or b) that a new government won't pick them up upon entering office. This is important to flag in relation to post-legislative scrutiny on the basis that impact isn't just about the first couple of months after a committee has reported.

The focus of post-legislative scrutiny in Session 6 has not solely been about full inquiries. Indeed the Conveners Group has encouraged consideration of how post-legislative scrutiny can be carried out more easily. This has led to committees innovating and identifying ways they can incorporate post-legislative scrutiny into their everyday work. For the purposes of this briefing, these are described as post-legislative innovations.

| Committee | Post-legislative innovation |

|---|---|

| COVID-19 Recovery Committee | Incorporating post-legislative scrutiny into the scrutiny of secondary legislation and Stage 1 scrutiny of the Coronavirus (Recovery and Reform) (Scotland) Bill |

| Health, Social Care and Sport Committee | Incorporating post-legislative scrutiny into the scrutiny of secondary legislation: Alcohol (Minimum Pricing) (Scotland) Act 2012 (Continuation) Order 2024 & Alcohol (Minimum Price per Unit) (Scotland) Amendment Order 2024 |

| Health, Social Care and Sport Committee | Undertaking post-legislative review of the Health and Care (Staffing) (Scotland) Act 2019 to gather necessary information and data to facilitate a full inquiry |

| Finance and Public Administration Committee | Undertaking post-legislative scrutiny of the Financial Memorandum that accompanied the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014i. |

| Net Zero, Energy and Transport Committee | People's Panel to review Section 91 of the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 |

The Health, Social Care and Sport Committee has been particularly active having undertaken one full inquiry; incorporating post-legislative scrutiny into the scrutiny of secondary legislation; and having undertaken post-legislative review, laying the groundwork for a full inquiry in the future.

It is these innovations which will be explored in more depth in the subsequent section of this briefing. While there is debate (politically and academically) about the quality of different forms of post-legislative scrutiny, this briefing aims to provide an overview of those different innovations undertaken by the Scottish Parliament during this session. These approaches are potential future models for successor committees in the Scottish Parliament; and are also future models for other legislatures looking to increase their engagement with post-legislative scrutiny. Given the challenges raised in the briefing evaluating Session 5 in relation to time and capacity and given the heavy legislative workload, innovation is vital to ensuring the Scottish Parliament is able to incorporate more post-legislative scrutiny into its work programme. However, that innovation does need to appraised in order to avoid post-legislative scrutiny becoming a box ticking exercise. Nor should innovations be seen as a replacement for full inquiries, but rather a supplementary form of post-legislative scrutiny.

Session 6 has seen eight full post-legislative scrutiny inquiries, and although this is three short of the number of inquiries undertaken by the Public Audit and Post-Legislative Scrutiny Committee and other subject committees in Session 5, it has been supplemented by at least five innovations . It has also meant that a wider range of subject committees have engaged with post-legislative scrutiny than in Session 5. This also compares favourably to Session 4, where subject committees were tasked with undertaking post-legislative scrutiny, albeit without the strategic priority that currently exists. Only five full inquiries were undertaken in Session 4. While it is too early to declare that the strategic priority of the Conveners Group has been a success, there is positive evidence that post-legislative scrutiny has advanced during Session 6, especially as the roll out of the strategic priority was not immediate after the 2021 Scottish Parliamentary Elections.

Case studies

The case studies in this section of the briefing are focused on post-legislative innovations (i.e. ways in which committees have engaged with post-legislative scrutiny outside of the formal structure of an inquiry) and focus on the work of the following committees:

COVID-19 Recovery Committee

Health, Social Care and Sport Committee

Finance and Public Administration Committee

Net Zero, Energy and Transport Committee.

The research involved document analysis of publications by the respective committees and four interviews (covering the first three committees) with officials. The first three case studies are structured around the key questions that were asked of each interviewee, with their responses summarised and analysed. It was not possible to secure interviews for the final case study focusing on the work of the Net Zero, Energy and Transport Committee. As a result, the analysis for this section is based on publications by the Parliament and is structured as a summary of the process and its outcomes. The discussion of interviewee comments reflects what participants said but are paraphrased in part and conclusions from the research are contained in the emphasis boxes throughout.

COVID-19 Recovery Committee: post-legislative scrutiny as part of Stage 1 scrutiny

This case study focuses on the work of the COVID-19 Recovery Committee and its scrutiny of the Coronavirus (Recovery and Reform) (Scotland) Bill (now the Coronavirus (Recovery and Reform) (Scotland) Act 2022). In particular, it focuses on the committee's approach to Stage 1 scrutiny. Stage 1 scrutiny involves the appraisal of the general principles of a bill. This scrutiny is conducted by a lead committee (normally the committee whose remit matches that of the bill). The lead committee is responsible for examining the bill and takes evidence and testimony from experts, organisations and members of the public about what the bill intends to do. Following the collection of that evidence the committee will write a report and give its view of the bill, including recommendations about whether the Parliament (as a whole) should support the principles of the bill. Following the completion of this stage, the Parliament then debates the bill and votes on whether it should continue through the legislative process. The ability to take evidence during this stage of the legislative process on the general principles of what the bill is aiming to achieve, does give committees an opportunity to look back at prior legislation in the area as well.

Trialling incorporating post-legislative scrutiny into the scrutiny of legislation

Prior to the introduction of the Coronavirus (Recovery and Reform) (Scotland) Bill, the COVID-19 Recovery Committee's work had been focused on renewing temporary emergency legislation relating to the COVID-19 pandemic. The focus was on secondary legislation that was extending the primary (parent) Act. This was a result of a sunset clause having been added to the bill during its original passage. A sunset clause is a provision within a law which sets an expiration date unless an extension is agreed. This kicked off the committee's interest in incorporating post-legislative scrutiny into its legislative processes. In relation to the extension of temporary legislation using secondary legislation, the committee tried a few different ways of asking stakeholders for information that was effectively post-legislative scrutiny (Interview O1). Those questions focused around whether the temporary legislation should continue and be extended for a limited of period of time and whether stakeholders could give examples of why that was the case (Interview O1). Questions were also asked about whether any provisions should not be extended, if that was the opinion of stakeholders (Interview O1).Although this wasn't explicitly labelled as post-legislative scrutiny, the committee was asking people questions which invited them to reflect on the effectiveness of the legislation that had been in force. The committee was required to scrutinise the legislation anyway and was trying to embed post-legislative scrutiny into the renewal of that piece of legislation. While this didn't take place through oral evidence sessions but through written submissions, it was an early test of how post-legislative scrutiny can be incorporated into legislative procedures. This particular example is specific to Acts were there is a sunset clause but it also shows it can be done. This form of incorporating post-legislative scrutiny into scrutiny of secondary legislation will be explored in more detail in relation to the work of the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee.

Post-legislative scrutiny and the Coronavirus (Recovery and Reform) (Scotland) Bill

The Coronavirus (Recovery and Reform) (Scotland) Bill was introduced in January 2022. Stage 1 scrutiny was split among five different committees as the legislation was aimed at putting certain COVID-19 powers onto a more permanent basis. The Bill therefore affected a number of different policy areas.

Approach

The COVID-19 Recovery Committee decided to incorporate post-legislative scrutiny into its Stage 1 scrutiny on the basis that "the new Bill was making permanent some of the temporary powers and there was a big focus on being seen to monitor the use of these powers" (Interview O1). Before the powers were made permanent, the committee wanted to review the use of them previously, in order to inform the scrutiny of the new Bill. Those powers were "extraordinary in terms of the impacts on people's lives … so it was very important reputationally for the Parliament to be effectively scrutinising those powers and doing so before deciding whether to extend them on a permanent basis" (Interview O1).

The interviewee noted that this was quite an exceptional case which was very topical. There was a lot of public interest in the Parliament exercising its powers to renew this legislation. There also was not time to launch a full post-legislative scrutiny inquiry as the Bill had been introduced in January 2022 with a deadline set for Stage 1 scrutiny of May 2022. The call for views was open between the 3 and 25 February 2022; this was followed by oral evidence sessions and the requirement to write a report. It is also important to note that the committee needed to focus on more than just looking back during this stage and, as such, the time window to focus on post-legislative aspects of previous legislation was narrow. With a narrow time frame, the committee wrote its call for views in advance of the Bill being introduced (based on what the Scottish Government had consulted on) and then compared that against the Bill as introduced to ensure it matched (Interview O1).

So there was a bit of guess work involved in terms of what would be in the bill but signs were there and it was possible to get ahead of the Bill.

Outcomes

Interviewee O1 noted that if the committee hadn't incorporated post-legislative scrutiny into Stage 1 scrutiny, it was unlikely that scrutiny would have happened in the short term. Indeed, even in the long term, there was not necessarily the appetite to go back and do discrete pieces of post-legislative scrutiny as politics was moving on after the pandemic had subsided. So it was the only opportunity to reflect back on COVID-19 legislation and the committee seized it.

By adopting a post-legislative scrutiny approach to the Bill, the committee was able to get much greater clarity on the Scottish Government's approach to legislating and how the powers differed from ones passed by other legislatures in the UK (Interview O1). It also gave the committee a better sense of why this legislation was being brought forward, which was particularly sensitive given these were emergency powers. It gave the committee a fuller picture of how that legislation fitted into a broader UK picture than the committee would have had if it had not looked back at previous pieces of legislation.

The process had changed the whole narrative around the legislation, because it had become clear that the Scottish Government were putting Scottish legislation on a par with that of England and Wales, rather than going well beyond those powers. The Government had not gone into that detail in its Policy Memorandum; it was evidence that the committee needed to seek out as it wasn't readily provided in background briefings (Interview O1).

There was clearly a benefit here to understand why the legislation was needed and this is potentially good practice for other committees as they might find something important and they might end up understanding the legislation better.

Benefits and challenges

While it is not a universal viewpoint, there is commentary which suggests that the Scottish Parliament has too readily legislated in a wide range of areas and has passed too much legislation not all of which was required.1

Contrary to this commentary, Interviewee O1 noted that doing this kind of post-legislative scrutiny gave the committee a much clearer picture of:

why the legislation was necessary

how it fitted into the broader policy landscape

what other legislation was out there and why it was considered to be deficient and requiring a new Bill.

It was also noted that, because the Scottish Government is not currently providing that level of detail in its Policy Memorandums,it is for the Scottish Parliament to go out and find that information and satisfy itself whether the legislation is required (Interview O1).

There is an element of best practice here, both in terms of incorporating post-legislative scrutiny into pre-existing workloads but also to better understand and highlight the issues from previous bills. It benefits the quality of subsequent legislative scrutiny, with MSPs having a better understanding of the wider policy and legislative context. So it is not just a benefit from a post-legislative scrutiny perspective but also from a wider legislative scrutiny perspective.

One challenge was reaching the right stakeholders to give evidence to the committee. Part of this was as a result of the legislation being very broad, but even when filtering down to Part 1 of the Bill, which solely focused on emergency health powers, the committee found that because Scotland is such a small jurisdiction, it does not necessarily have experts covering all areas of policy that might come up (Interview O1).

Another challenge was that of time. The Bill was introduced in January 2022 and the Government wanted it passed by June 2022. With the call for views going out in early February, there was a need for a lot of preparatory work before the Bill was introduced. As noted earlier, this did involve some guesswork on what would be in the Bill, which was then checked against the Bill as introduced. It became obvious from the first oral evidence session that the committee needed more information about public health powers, and there was pressure to rapidly find an expert external commentator who could provide the missing evidence that was needed (Interview O1). Time was needed to find that person, have them do the work, provide written evidence to the committee and then for the clerking team to feed that back to MSPs (Interview O1).

This is a key difference with self-initiated inquiries in that although there might still be time pressures, there is not a fixed date by which to report. It is one of the reasons why it is still important to find space and time to conduct full inquiries too. This is clearly a wider issue with the legislative process too regardless of whether there is a post-legislative aspect to it or not. There is perhaps a need for bills to be published further in advance in order to give committees more time to prepare – which in the end will lead to better scrutiny of the legislation.

Replicability

Interviewee O1 noted that they would repeat this approach and that they would want to continue building a picture of how a bill or piece of secondary legislation fits into a wider legislative context, because it leads to better scrutiny. It does serve as an illustration that a committee doesn't always need lots of time to do post-legislative scrutiny, even in exceptional circumstances when it is under a lot of pressure.

In order to deliver this scrutiny effectively, Interviewee O1 noted that there might need to be some staff training on how to do it well, particularly in time-pressured situations. Questions around resources were also raised in relation to repeating this activity. As such, there was a question of whether officials want to be doing all of the information-gathering on wider legislative frameworks or whether experts should be providing that information to the Parliament (Interview O1). While there is a process for commissioning research, in this case the committee was lucky and able to lean on people's goodwill (Interview O1).

The other issue here is that commissioning research costs money and usually requires lead time.

When it comes to replicating the activity for other bills, it was something that Interviewee O1 felt was possible and that other committees could explore as part of their scoping.

Member engagement

This approach was not specifically framed as post-legislative scrutiny to Members as it was embedded into the committee's approach to legislative scrutiny. However, Members were consulted on the types of questions that the committee were to ask in their call for views and oral evidence sessions (Interview O1).

So while MSPs might not have recognised it as a piece of post-legislative scrutiny in the formal sense, they were still engaging with the principles of post-legislative scrutiny.

Interviewee O1 also noted that when it came to the outputs of this Stage 1 scrutiny, Members were very engaged with the evidence looking back at previous Acts of the Scottish Parliament in this area. Indeed, evidence provided by academics in this area was also well received by Members and actively quoted in the Stage 1 debate (Interview O1).

There is an interesting aspect to embedding post-legislative scrutiny into pre-existing procedures in that, not only does it deliver wider benefits to legislative scrutiny, it also prevents post-legislative fatigue setting in. It becomes a normalised part of what the Parliament is doing, or rather the questions revolving around looking back at past Acts become normalised.

Interviewee O1 also noted that the government probably wouldn't recognise their line of questioning and work as post-legislative scrutiny but they engaged with the outputs well during the Stage 1 debate too (Interview O1).

Health, Social Care and Sport Committee: post-legislative review

One area of interest that has arisen during the course of this research is the amount of information gathering that the Parliament must do itself in relation to post-legislative scrutiny. This involves a lot of behind the scenes work by committee clerks as well as the research teams in SPICe. One aspect of post-legislative scrutiny that varies between the Scottish Parliament and Westminster is that, in the latter parliament, the UK Government is expected to publish its own review of Acts of Parliament within three to five years of Acts entering into law1. If this does not happen, committees have the right to request and compel this information be provided2. This arrangement does not currently exist in the Scottish Parliament and the power to compel as stated in the Parliament's standing orders and in section 23 of the Scotland Act only refer to the ability to require any person to "produce documents in that person's custody or under that person's control". It is not clear whether committees would have the power to request similar memorandums from the Scottish Government, especially if they do not already exist in some form. Without such an arrangement and with ambiguity over powers, this is why post-legislative review becomes such an important process for committees. However, it can involve substantial work by SPICe when supporting committees. Further to this point, it enables committees to engage with post-legislative scrutiny even when there is limited time to conduct such scrutiny.

This case study is a key example of how committees can work behind the scenes to draw information together which firstly reminds the Government that the committee is interested in the implementation and operation of a certain Act and secondly provides the foundations for the committee to launch a full post-legislative scrutiny inquiry in the future, should it find the time in its work programme to do so.

Approach

The process began as a discussion between committee clerks and researchers within SPICe. In this case, there were a couple of areas where Interviewee O2 and their colleagues in SPICe knew that they wanted to do some background research. During the passage of the Health and Care (Staffing) (Scotland) Act 2019, they had become aware that there were stakeholders who were unhappy with the legislation. In addition, it appeared that not much had happened since the passage of the Act either (Interview O2). As such, the committee wanted to see what had been going on, although they suspected very little as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic (Interview O2). The committee wanted to put a bit of pressure on the Government and see:

what work it had done on the Act

what the plans were going forwards

how the committee could address some of the concerns that stakeholders had (Interview O2).

Interviewee O2 noted that the committee knew there were issues but they were not sure what had happened since the Act's passing. Interviewee O2 also noted that the committee had written to the Scottish Government as part of the process and that the response they received (and the gaps in it) meant that the committee should look at the Act more widely. The Government had presented a timeline of intended activity, which the committee could use in the future as a baseline to judge the implementation and operation of the Act (Interview O2).

This was viewed very much as an initial piece of post-legislative scrutiny prior to a full inquiry taking place. From an academic perspective, this very much represents what Westminster would call post-legislative review which is how it will be labelled in this briefing. The key difference being that, in the case of Scotland, the information is being gathered and presented by a committee and SPICe rather than by the Government itself. The work was viewed as an information-gathering exercise and, indeed, post-legislative review itself can have a number of functions. Firstly, it puts the Government on notice that this is something the Parliament is interested in (which can generate action in and of itself). Secondly, it acts as a litmus test to determine whether a full inquiry is needed. In this case, it has not yet led to a full inquiry, but as noted earlier in the briefing this is something that remains on the committee's to do list as part of its future work programme.

However, this is where committee constraints are relevant. In that regard, the committee has yet to find time to complete a wider inquiry into health and care staffing.

Another challenge was that the turnover of members of the committee had pushed the issue of health and care staffing down the agenda (Interview O2).

It is worth noting, though, how proactive the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee have been during Session 6 when it comes to post-legislative scrutiny. The benefit of conducting post-legislative review in this way is that a successor committee, whether in Session 7 or beyond, can come back to the issue should they wish to. There does arguably need to be an element of caution though in undertaking such work, in order to avoid post-legislative scrutiny fatigue among Members. Further caution is also needed to ensure that post-legislative review, were it to be replicated, is not viewed as being the same as post-legislative scrutiny or a replacement for it. Rather it should be viewed as supplementary to the inquiry process.

Outcomes

Interviewee 02's view was that the main outcome from this approach was that when the committee or its successor comes to look at the issue of health and care staffing again, they have a baseline and foundation to work from (Interview O2). Interviewee O2 also noted that they did not think the work had achieved much substantially, although they suggested it would have given the Scottish Government a bit of a nudge. However, to date the committee is not aware of progress being made in this area (Interview O2).

The above may not perhaps seem like much in terms of a main outcome. However, it should not be underappreciated. In an ideal world, the committee would have undertaken full post-legislative scrutiny. However, going through the process of collecting data and evidence is still important in order to paint a picture of where an Act is in terms of implementation and performance. This is especially important as the Scottish Government does not ordinarily provide this information directly to the Parliament. The activity is, therefore, still a useful one which does not require a huge amount of committee time, albeit it does require the time of the clerking team and SPICe, and the Convener and Members agreeing to send a letter to the Government. It provides a useful process to engage with post-legislative scrutiny in preparation for a full inquiry, but can also be a tool for engaging with the process even when workload and time do not permit a wider inquiry. In some cases, it could also form the basis of a one-off oral evidence session too.

Benefits and challenges

Interviewee 02 noted that the main benefit of this approach to post-legislative scrutiny is that it it is very quick and that the committee receives the information requested from the Government as they have to respond (Interview O2). In the grand scheme of things, it was thought that this approach did not really take up any of the committee's time (Interview O2). As a result of this process the committee was also seen to be responding to the concerns of stakeholders, because the letter to and response from the Scottish Government were published (Interview O2). The committee could then point stakeholders to the updates and receive feedback from them too (Interview O2). It was also noted that although, in an ideal situation, more work would have been done on the issue, it was better than doing nothing at all and not responding to the concerns of stakeholders (Interview O2).

Consequently, this approach can provide a a helpful model to engage committees with post-legislative activity . It also sets them up to launch a wider inquiry if time permits. However, it should be noted that this approach is not advocated as a replacement for full post-legislative scrutiny. Instead, it is useful as a first step on the road to wider scrutiny or as supplemental scrutiny.

The key challenge noted was that the committee felt that it had done something on the issue already, so when the suggestion was made to launch a wider inquiry, they decided not to (Interview O2). The decision not to launch a wider inquiry was on the basis of the wider post-legislative activity that the committee had undertaken during this session, which is to be commended. In addition, the committee had already written to the Government and had received a response, so in the minds of Members they had completed work on this topic (Interview O2).

This issue is a big challenge and suggests that, although post-legislative review can be a useful model for committees, caution is needed to prevent it being seen as a substitute for post-legislative scrutiny.

Replicability

Despite all the challenges this is something that Interviewee O2 would do again because “it is a really good way to start the process” (Interview O2). Interviewee 02 also indicated that this approach is flexible and that conducting post-legislative review could be the end of the process, with one simply writing a letter to the Government and updating stakeholders without doing any more. However, they also noted that post-legislative review can also spark something else and inform wider scrutiny (Interview O2). As the Scottish Government does not ordinarily provide the information envisaged in post-legislative review, taking the opportunity to provide an update on where an Act is in terms of implementation and operation is useful and is an important role for the Parliament. Interviewee 02 noted in that regard that “the more information you can get on different topics the better, then you can assess which ones you want to take forward” (Interview O2).

Post-legislative review is clearly something committees and, in particular, clerking teams can do to keep post-legislative scrutiny alive during a period where time might be limited for a wider inquiry. Interviewee O2 also noted that the approach taken by the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee is something that could very easily be replicated by other committees.

Resource implications

There were not any major resource implications as part of this approach, other than the time of the clerking team and colleagues in SPICe. It was something SPICe and the clerking team were able to absorb into their workload but it did not really have any impact on the committee's resources other than asking them to approve a letter to the Government (Interview O2). Interviewee 02 notes that "it was a time when I had a little bit more capacity, so they are good things to do between other projects" (Interview O2).

Member engagement

Members were involved in initial discussions to decide whether or not the committee wanted to focus on the topic and there were a number of Members who were very keen (Interview O2). Prior to post-legislative review taking place, a piece of secondary legislation had come before the committee where stakeholders had raised issues with the legislation too (Interview O2). In terms of conducting post-legislative review itself, Members agreed to the focus on it but it was the clerking team and SPICe who conducted the research and presented the letter to the Scottish Government to the committee for approval (Interview O2).

Health, Social Care and Sport Committee: post-legislative scrutiny as part of scrutiny of secondary legislation

The approach to post-legislative scrutiny by the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee in this case again involved incorporating it into aspects of other parliamentary (and in particular legislative) scrutiny. It came about as a result of a sunset clause in the Alcohol (Minimum Pricing) (Scotland) Act 2012 (2012 Act). The Act, which set a minimum price for alcohol sold in Scotland at 50p per unit, was passed in May 2012 and came into effect in May 2018.The sunset clause meant that the legislation would lapse unless the Scottish Parliament approved an extension. The clause also required the Scottish Government to provide a report on the operation and effect of minimum unit pricing. As a result of the sunset clause, two pieces of secondary legislation were laid in the Scottish Parliament:

The Alcohol (Minimum Pricing) (Scotland) Act 2012 (Continuation) Order 2024, extending the parent Act by a further six years.

The Alcohol (Minimum Price per Unit) (Scotland) Amendment Order 2024,which increased the minimum unit price from 50p to 65p.

The two pieces of secondary legislation were subject to the affirmative procedure which meant that the Parliament had to agree to them before they would come into effect, thus extending the provisions in the 2012 Act. It should also be noted that secondary legislation cannot be amended, only approved or rejected.

More details and background on the Orders can be found in the SPICe briefing "The Alcohol (Minimum Pricing) (Scotland) Act 2012 (Continuation) Order 2024".1

Approach

The Health, Social Care and Sport Committee was the lead committee scrutinising the secondary legislation. The Orders were backed by a number of evaluations and consultation reports that were commissioned by the Scottish Government and Public Health Scotland. The University of Sheffield also undertook some modelling and the modelling, consultation and reports were referenced throughout as justification for both extending the policy and uprating the minimum unit price (Interview O3). As the sunset clause required the committee (and subsequently the Parliament) to approve the extension of the Act, the committee took the initiative to include elements of post-legislative scrutiny in its scrutiny of the secondary legislation.

The committee started its process of post-legislative scrutiny by holding an evidence session with the Minister for Drugs and Alcohol Policy (Interview O3). The committee also tried to strike a balance between stakeholders who had the most to say on the policy. This involved two panels. The first panel consisted of drug and alcohol charities who were relaying to Members their experience and their members’ experiences since the introduction of the parent Act (Interview O3). Those stakeholders were strongly in favour of continuing the policy as well as the uprating, saying there had been a noticeable impact, if not in reducing alcohol related deaths directly, then certainly in helping improve public health outcomes (Interview O3). The second panel was an attempt to balance this evidence with that of retail organisations who faced an impact from the uprating of the minimum unit price (Interview O3). After that session, the committee felt that they had covered all bases in terms of what they needed in order to hold a further session with the Minister (Interview O3). The Minister subsequently appeared before the committee to answer questions from Members. There was a general consensus from Members that the 2012 Act should continue and that the uprating should take place (apart from two Members who voted against both motions) (Interview O3). Following the committee's scrutiny, the Minister then moved motions in the chamber in relation to the two Orders, both of which passed.

The committee's approach to post-legislative scrutiny involved it taking the opportunity to take evidence on the operation of the 2012 Act before deciding: a) whether the legislation should be extended, and b) whether the minimum unit price should be uprated. This is a relatively unique position due to the nature of the sunset clause. However, it does present an additional way to embed post-legislative scrutiny into existing procedures. Although sunset clauses are not common, the approach outlined above does perhaps present a model for how this could be repeated again should committees need to extend other Acts in future. It also shows how committees can innovate to incorporate post-legislative scrutiny into their existing processes and workload. Although the approach taken did not lead to a full review of the 2012 Act and a dedicated post-legislative scrutiny report, the oral evidence collected did feed into the committee's deliberations and the committee report on the secondary legislation.

Interviewee 04 indicated that there was a lot of controversy on minimum unit pricing when the legislation was introduced and that the compromise that was reached at that time was that there would be a sunset clause so that the Act could be reviewed before being extended (Interview O4) . Interviewee 04 noted that this is a very distinct case of post-legislative scrutiny as, in most circumstances, it would be something a committee would proactively do, whereas there was a specific trigger here (Interview O4). The committee knew that it was going to have to undertake scrutiny of two pieces of secondary legislation as part of its normal work, so it was reacting to that rather than proactively deciding to do post-legislative scrutiny (Interview O4). The question of how the policy had worked in practice became important because the committee needed to come to a view about whether it was content for the policy to be extended and whether an uplift should occur as well (Interview O4).

The committee were acutely aware that it was operating with a distinct time scale in mind (Interview O3). The parent Act was due to expire and, as such, there was a fixed deadline for taking evidence, reporting to the Parliament and for the Parliament to agree to both motions. As a result, the committee didn't have an infinite amount of meetings that they could dedicate to delving into the research and looking for alternative experts as would often be possible for a piece of full post-legislative scrutiny where there is more flexibility (Interview O3).

Outcomes

The main outcomes were that the parent Act was extended and that the minimum unit price was uprated. The committee took the view that it had done its job in order to meet the tight timescales and that was the main thing (Interview O3). However, another important aspect of this work was that the committee had heard evidence from a range of conflicting stakeholders in order to inform this scrutiny of the extension and uplift Orders (Interview O3).

Interviewee O3 noted that the approach was also interesting from the perspective that the committee was using the scrutiny as a launch pad for justifying why the policy should continue. This aspect of post-legislative scrutiny was about looking back at how the Act had performed and making the case for the policy continuing. In that regard, it is perhaps an example of how post-legislative scrutiny can sometimes play a more positive role rather than simply being about finding errors and holding the executive to account, although that is undoubtedly part of its role. Here the process was very much a case of focussing on whether the policy was working and if it was, extending the operation of the parent Act. Interviewee O3 also noted that the process used was quite distinctive in the sense that Ministers were using the evidence gathered to justify to the Parliament as a whole why the Act should be extended and the minimum unit price uplifted. Interviewee O4 highlighted that this approach to post-legislative scrutiny had a more defined purpose. In normal circumstances, committees would produce a report which might be debated in the chamber but there would not necessarily be a vote, whereas, as the secondary legislation was subject to the affirmative procedure, there was a natural end point for this approach to post-legislative scrutiny (Interview O4).

Benefits and challenges

The main benefit was that post-legislative scrutiny was incorporated into an existing work programme item that had to be scrutinised, rather than the committee having to find time as a self-initiated inquiry. A key benefit noted by Interviewee O3 was that the committee was able to give a voice to a broad range of different views, both for and against the policy.

The issue of giving a voice to stakeholders and the public was raised as a main benefit of post-legislative scrutiny during the research on Session 5. This further underpins the important role of post-legislative scrutiny in allowing further input from external organisations and individuals in the policy making process.

Time was an initial challenge. This is distinct from full post-legislative scrutiny inquiries, as it is not an issue of fitting an inquiry into a tight work programme. Rather it is about having a set deadline to scrutinise the legislation, produce a report in time for the Parliament to approve the motions ahead of the parent Act expiring (Interview O3; Interview O4).

Interviewee O3 noted that there was a further challenge in terms of evidence gathering from the perspective of dealing with two very specific pieces of secondary legislation and keeping discussion narrow and not going down other routes.

For a broader piece of post-legislative scrutiny, it would be relevant to branch scrutiny out into different areas of the policy. However, in this case, there was a need to remain focused on the content of the two pieces of secondary legislation.

Interviewee O3 noted that one good example of a relevant area of discussion as part of a wider piece of post-legislative scrutiny would be the question of where the money goes that is raised from the minimum unit price policy. In the evidence session the issue was raised that the money was, in effect, simply going back to retailers as a result of higher prices and that there is no levy to draw that money back to charitable organisations or support networks (Interview O3).

In a broader piece of post-legislative scrutiny that would be a relevant line of questioning, however that is not what the secondary legislation was seeking to enact: the committee only had two options, to agree to the uplift or to reject it. The committee decided to recommend the uplift to maintain its effectiveness in reducing alcohol-related harm, even if there were questions on where the money goes.

Interviewee O4 also noted in addition that, as the Orders could not be amended, there were topical debates about whether 65 pence was the correct level to increase the minimum unit price to but this could not be factored into the end decision. The committee did, however, take oral evidence on this issue and that evidence is now on the public record (Interview O4).

Replicability

Interviewee 03 thought that this could be repeated, probably in another six years, as the Parliament will need to make a decision as to whether it wants to extent the Alcohol (Minimum Pricing) (Scotland) Act 2012 again in 2030 (Interview O3). Interviewee 03 also noted that there wasn't a lot that the committee could have done differently in terms of how it tackled the process (Interview O3). In an ideal world the committee would have had more evidence sessions before producing its report with recommendations on whether the Parliament should approve or reject the motions (Interview O3). However, it was "on rails really", the Government knew when it needed to introduce the legislation in order to have sufficient time to scrutinise and pass the motions before the parent Act expired (Interview O4). Interviewee O3 did note, however, that when the successor committee scrutinises similar motions in the future, there is now a launchpad and baseline for what they can expect.

Interviewee O4 did note that although it is up to Members to decide what their priorities are, there is a case to be made for a committee to come back to the parent Act two or three years down the line in order to undertake a broader piece of post-legislative scrutiny.

Given that both interviewees raised that Members were keen to question witnesses on wider areas of the policy and that evidence was being presented which suggested that there are other changes that could be made to the Act, there is perhaps an argument for a larger piece of post-legislative scrutiny in order to appraise the Act in more detail. If Members were so minded, this is something that the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee could include in its legacy report as we head towards the end of this session.

Interviewee O3 noted that if the next evaluation report (required as part of the sunset clause) presents different results to the one this committee has examined, then there would be an even stronger case for a broader post-legislative scrutiny inquiry but that it is ultimately up to Members of the successor committee to make that decision.

Interviewee 04 also thought that this would definitely be the model to follow if a committee was faced in the future with a piece of legislation which had a sunset clause relating to extending a parent Act, (Interview O4). Although sunset clauses are rare, Interviewee O4 noted that it could be argued that having such clauses written into legislation actually places a greater onus on the Parliament to undertake ongoing scrutiny of a policy.

Resource implications

The work carried out by the committee was reactive rather proactive as there were two very specific pieces of secondary legislation that the committee had to reach a position on (Interview O4). This meant that it immediately went up the hierarchy of priority for the committee, and was always going to get prioritised over other work (Interview O4).

Finance and Public Administration Committee: post-legislative scrutiny of financial memorandum

The Finance and Public Administration Committee has innovated in the way it has approached post-legislative scrutiny during Session 6. The committee is less legislatively intensive than other committees in the Scottish Parliament as a large amount of its time is spent scrutinising the Scottish Government's annual budget alongside financial memorandums that accompany bills as they pass through the legislative process. As a result of post-legislative scrutiny also not being compatible with Finance Acts (on the basis new legislation is introduced for each financial year which succeeds the previous Act), the committee has found an alternative approach to contribute to the strategic priority on post-legislative scrutiny. It was decided that, in order to fulfil its post-legislative scrutiny role, the committee would re-examine financial memorandums after the law had been implemented to see how accurate the original cost estimates were, and whether any anticipated savings had been realised. This is an approach to post-legislative scrutiny which is not common but also one which could be applied to other legislatures in the UK and beyond.

What are financial memorandums?

When bills are introduced to parliament for legislative scrutiny, they are usually accompanied by a financial memorandum. The purpose of financial memorandums is to set out best estimates of the costs, savings, and changes to revenues arising from a bill, as well as to outline the financial implications for the government, local authorities and other connected organisations. In the Scottish Parliament, it is the role of the Finance and Public Administration Committee to scrutinise these financial memorandums and, in so doing, the committee asks those (people and organisations) who might be financially affected by the legislation for their views. Such scrutiny is simultaneous with the examination of the details of the bill by subject committees.

From the responses it receives the committee will do at least one of the following1:

take no further action beyond passing the submissions on to the lead committee for its consideration

write to the lead committee highlighting any areas of concern and suggesting that it may wish to raise them with the Scottish Government Minister responsible for the Bill

invite stakeholders who have responded to expand upon their submissions in oral evidence

invite Scottish Government officials to respond to the issues raised in oral evidence

publish a formal parliamentary report to the lead committee highlighting any areas of concern and suggesting that it may wish to seek further information on them from the Scottish Government.

Approach

The committee undertook post-legislative scrutiny of estimated costs that arose from the expansion of early learning and childcare, as set out in the financial memorandum for the Children and Young People (Scotland) Bill. This was a pilot approach to post-legislative scrutiny and was intended to provide a model of how this type of scrutiny might be effectively undertaken in the future (Interview O5).

This is effectively a new form of post-legislative scrutiny, although it is not direct scrutiny of the bill itself, it is scrutiny of documents which accompany the bill during its passage through the legislative process. As the financing of such legislation will form a key part of its implementation and its success, this is an important innovation, particularly for committees which are finance based and, as a result, engage less with the review of legislation. In many ways, although this is a new approach to post-legislative scrutiny, it also bears the hallmarks of more traditional modes as it does follow the process of a formal post-legislative scrutiny inquiry, in that evidence was gathered both in written and oral form and a letter (rather than a report) was prepared to send to the Scottish Government on which a reply was sought.

The definition of post-legislative scrutiny by the Law Commission of England and Wales1 is broad and talks about assessing whether policy objectives have been achieved and, if so, how effectively. As finance is a key part of how effectively a policy will operate, this type of scrutiny falls under the remit of post-legislative scrutiny.

There is also an additional benefit from this approach to post-legislative scrutiny in that it is designed to enhance the development of financial memorandums in the future (Interview O5).

Again this is a key goal of post-legislative scrutiny, i.e. to improve the quality of law and policy making.

In shaping its inquiry the committee agreed to ask the Financial Scrutiny Unit in SPICe to gather relevant financial data from local authorities and the Scottish Government to identify the actual costs of the legislation in order to compare it to what was proposed/estimated in the original memorandums (Interview O5). The committee sought to gather further written and oral evidence from specific stakeholders and report its findings and recommendations to the Scottish Government by way of a letter (Interview O5).

With the help of SPICe, the committee therefore sought to identify the current landscape in order to compare it to the original source material, whilst also taking evidence and conveying its views to the Scottish Government.

Why did the committee decide to undertake post-legislative scrutiny in this way

The committee's rationale for focusing its attention on post-legislative scrutiny of the early learning and childcare provisions in the Children and Young People (Scotland) Bill was five-fold (Interview O5):

Firstly, the Bill introduced significant policy measures to expand free childcare provision with significant costs attached, in particular for local government (Interview O5).

Secondly, the Finance Committee in Session 4 had raised concerns when the original Financial Memorandum was considered in relation to the financial estimates and the assumptions underpinning them (Interview O5).

Thirdly, there were different views between the Scottish Government and local authorities regarding the likely scale of the costs (Interview O5).

Fourthly, those concerns led to a Supplementary Financial Memorandum being published which received further scrutiny by the Session 4 committee.

Finally, the committee's report in Session 4 concluded that the ‘government needs to develop a more robust methodology for forecasting potential savings from preventative policy issues. There was therefore a need to develop measures to ensure that the actual savings are effectively monitored and reported’ (Interview O5).

There were clearly numerous issues with this particular financial memorandum and the Session 6 committee was able to look back at previous issues that had caught the attention of its predecessors in order to select an appropriate candidate. As noted in the research briefing on post-legislative scrutiny in Session 5, there is a need for more committees to be flagging the work of their predecessors to aid them and their successors in their post-legislative scrutiny work.

Outcomes

The committee reviewed the initial financial estimates and monitored expenditure following the policy's implementation. Its goal was to help inform and improve the development of future financial memorandums. Before the committee formally launched its inquiry, SPICe sought data from local authorities and the Scottish Government before producing a briefing note including an analysis of the data received (Interview O5). The committee then took evidence from local government representatives as well as childcare providers, followed by government officials (Interview O5). The committee concluded that, despite the Session 4 committee's call for ongoing monitoring of implementation costs, challenges were still present (Interview O5). The committee noted in its letter to the Government that:

Evidence provided to the committee shows that monitoring of expenditure continues to pose challenges to the Scottish Government and local authorities. Robust financial data is needed to provide a clear assessment of outcomes, sustainability and value for money.

While the committee acknowledges the progress that has been made in this area, we recommend that the Scottish Government undertakes further, more detailed data collection exercises on a regular basis, including comparisons between allocations and expenditure at local authority level.

The committee further recommends that future Financial Memorandums include comprehensive information on the Scottish Government's plans to monitor expenditure to ensure that new policy initiatives are being appropriately funded and ensure greater transparency around spending.

Following the completion of the inquiry, the committee requested that costs be monitored in relation to several bills and sought to tie in reporting on costs for specific bills to significant regular publications such as the Medium-Term Financial Strategy (Interview O5). This is something that is still being discussed with the Government at the time of writing (Interview O5).

The committee further recommended that:

To enhance transparency and enable effective scrutiny, the Scottish Government should avoid implementing major policy expansions via secondary legislation, where costs are significantly higher than estimates in the original FM. This is noted as a particular concern in relation to the National Care Service Bill.

Interviewee O5 noted that this particular recommendation became an important reference point for the committee's scrutiny of financial memorandums. This recommendation was reiterated in various reports and letters where the committee raised concerns regarding the use of framework legislation. The following bills were of note in relation to this particular aspect:

the National Care Service (Scotland) Bill

the Circular Economy (Scotland) Bill;

the Police (Ethics, Conduct and Scrutiny) (Scotland) Bill (Interview O5).

The committee built upon this recommendation in correspondence with the Minister for Parliamentary Business, in an effort to improve the quality and consistency of financial memorandums. The Minister committed to updating and improving guidance for civil servants in developing financial memorandums (Interview O5).

The committee has gone on to have impact through its persistent follow up to its inquiry. This is a key example of why follow up and keeping on top of key recommendations is important in terms of pushing for action from the Government. This process in and of itself is also important, with the Finance Committee being able and willing to review previous financial memorandums, it should encourage the government to focus more on their accuracy on the basis that they could get pulled up by a successor committee at some point in the future for poor estimates and delivery. This is also an important example of where there is an accountability element of post-legislative scrutiny in terms of implementation and accuracy, as well as the usual policy development role in advancing policy in various areas. A key purpose of post-legislative scrutiny is to ensure that more thought and effort goes into drafting and preparing bills in order to provide better quality policy. This is a very specific type of post-legislative scrutiny that the committee can come back to repeatedly and, through regularly scrutinising new financial memorandums, it is able to flag other issues which successor committees may wish to come back to.

Benefits and challenges

Interviewee O5 noted that this approach of focusing on a financial memorandum relating to a major policy measure was helpful. It allowed the committee to directly compare progress in areas where its predecessor committee had already recommended that specific action be taken. It was also noted that the narrow focus specifically on the expansion of childcare was viewed as helpful to ensure a more contained first post-legislative scrutiny inquiry, rather than focusing on an entire financial memorandum (Interview O5).

This is another good example showing that it isn't necessary to review an entire Act or, in this case, financial memorandum as committees can instead be guided by where evidence of problems leads them. This is particularly important when committees face wider capacity issues, with narrow gaps in their work programmes. A more contained inquiry can ensure the most pressing issues are dealt with and the case of the Local Government, Housing and Planning Committee addressing multiple parts (part 2 and part 9) of the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015 shows that committees can return to legislation if they feel that they need to.

There were two key challenges that Interviewee O5 noted in relation to undertaking post-legislative scrutiny of financial memorandums.

Firstly, it was anticipated that gathering the necessary data from local authorities and the Scottish Government would take a few months. However, in practice the complexities of the data and the various iterations that had to be collated in order to establish a robust dataset, led to data collection taking much longer than anticipated (Interview O5). Interviewee O5 noted, however, that it was important to have a full and clear picture of the available data to inform a SPICe briefing for Members before the oral evidence sessions took place.

It was also raised that while sufficient time had passed to allow the policy to embed, inevitably the policy approach had evolved since the initial scrutiny of the bill and the original financial memorandum (Interview O5). As such, additional written and oral briefings from SPICe were needed on how the policy had developed in the meantime and this led to further challenges in separating out financial data relating to the original provision and those relating to subsequent policy changes (Interview O5).

There are clearly lessons to take away from this experience in terms of planning for future post-legislative scrutiny of financial memorandums in terms of preparatory time for gathering data and also monitoring how the policy may have evolved since the initial scrutiny of the bill and the original financial memorandum. There is also potentially a resource challenge as well in terms of collecting such data, although if the committee only does one or two inquiries per session this issue is not insurmountable. It also adds to wider analysis of how much heavily lifting the Parliament has to do in terms of gathering data – which is not ordinarily provided by the Government.

Replicability

Following the completion of the inquiry, clerks prepared an evaluation of the pilot, which was considered by the committee at its Business Planning Day in 2023 (Interview O5). The outcome of that evaluation was that it was a worthwhile exercise and it did contribute to the committee's wider scrutiny of financial memorandums and continuous work to improve the quality of such memorandums (Interview O5). In light of the challenges that Interviewee O5 noted, the committee agreed that future post-legislative scrutiny would focus on financial memorandums :

where the provisions in the Act have had sufficient time to be implemented and ‘bed in’, but where the policy environment has not changed too substantially

which have been the subject of concern expressed by predecessor Finance Committees

which relate to significant policy measures and/or contain significant estimated cost implications or forecasts significant savings

where the findings could potentially inform other scrutiny work the Committee undertakes or produce outcomes that could impact on other areas of the committee's remit.

The committee has not completed any further post-legislative scrutiny due to existing pressures in the work programme. However, there has also been a challenge in selecting an appropriate financial memorandum due to the complexity and in some cases lack of data available (Interview O5).

The evaluation undertaken by the committee provides a useful insight into the thought and work that has gone into developing this approach to post-legislative scrutiny. Lessons have clearly been learned from the pilot inquiry and this is reflected in the criteria that the committee will use going forwards in order to select financial memorandums for post-legislative scrutiny. The challenges around the complexity and lack of data remain; however, this is also a reflection of the information disadvantage that Parliament is at compared to the Government. There is also potentially an issue of important data not being collected in the first place, however going through the motion of post-legislative scrutiny of financial memorandums may encourage the government and other organisations to collect and monitor such information in the future. Post-legislative scrutiny can have an anticipated reaction effect.

Net Zero, Energy and Transport Committee: post-legislative scrutiny through a People's Panel

The final case study appraises the work of the Net Zero, Energy and Transport Committee in relation to their People's Panel which reviewed section 91 of the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009.

It was not possible to conduct interviews for this case study, so instead it is built around committee documents and SPICe publications. However, this is an important case to reflect upon because it focused on public engagement. This is important for post-legislative scrutiny as it can be viewed as quite a technical process, when in fact it relates to the experiences of the public and other stakeholders who are impacted by legislation and public policy. Being able to incorporate public engagement into such activities is an important step forwards in being able highlight the relevance of post-legislative scrutiny and the legislation reviewed to the public and constituents more widely, whom MSPs and the Scottish Parliament seek to serve. A report by the Westminster Foundation for Democracy on post-legislative scrutiny of climate change legislation highlights that participative and deliberative democracy can bring greater insight and buy-in to post-legislative scrutiny.

What are People's Panels?

A People's Panel is a form of deliberative public engagement, which brings together a cross section of the Scottish public which is broadly representative, in order to learn about an issue, deliberate and produce recommendations1. Alongside post-legislative scrutiny being declared a strategic priority, the Conveners Group also had strategic priorities on participation, diversity and inclusion for committees in order to embed public participation into committee activity and the wider work of the Parliament1. Following its report on embedding public engagement in 2023, the Citizen Participation and Public Petitions Committee recommended two further People's Panels be created, one of which was on post-legislative scrutiny.

Climate Change People's Panel

In October 2023, the Conveners Group endorsed the formation of a people's panel to support the Net Zero, Energy and Transport Committee's post-legislative scrutiny of section 91 of the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009. This section requires the Scottish Government to produce and periodically review a public engagement strategy for climate change1.

The People's Panel was asked to discuss and prepare recommendations in response to the following questions1:

How effective has the Scottish Government been at engaging the public on climate change and Scotland's climate change targets?

What else (if anything) could the Scottish Government do to inform and involve the public to help meet Scotland's climate change targets?

23 members of the Scottish public were randomly selected to represent the breadth of demographics in the population. They travelled to the Scottish Parliament to meet and deliberate with experts and committee members over two weekends and through two online sessions in February and March 20241. Full details of the demographic make-up of the panel can be found in the Net Zero, Energy and Transport Committee's report.

A stewarding body was also appointed, comprised of experts in relevant fields in order to ensure there was fairness, credibility and transparency in the process4. The operation of the People's Panel was reviewed by Elisabet Vives, Iñaki Goñi and Eugenia Rodrigues of the University of Edinburgh. However, the outcome from the Panel was a collective statement along with 18 recommendations for the Scottish Government in terms of its engagement on climate change.

The collective statement of the Panel suggested:

There needs to be truth and honesty from the Scottish Government about the scale of the challenge, and a compelling vision of the better world we are all aiming for… The panel have considered all evidence they have heard and concluded that collaboration with expert local and community led organisations is the key to success … The panel recognise that change is not easy but needs to happen … The panel would like the Government to commit to understanding the action gap and barriers to participation.

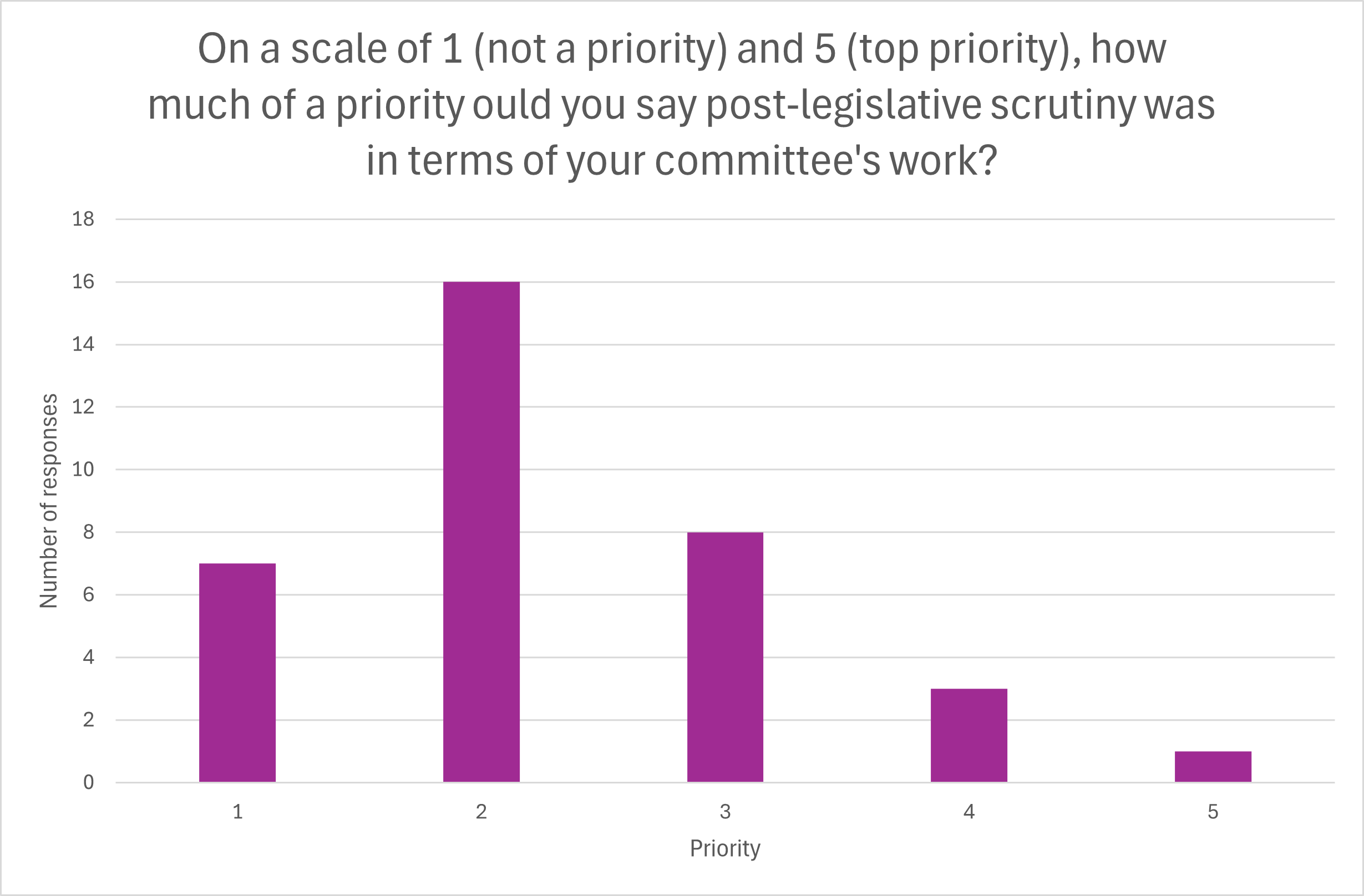

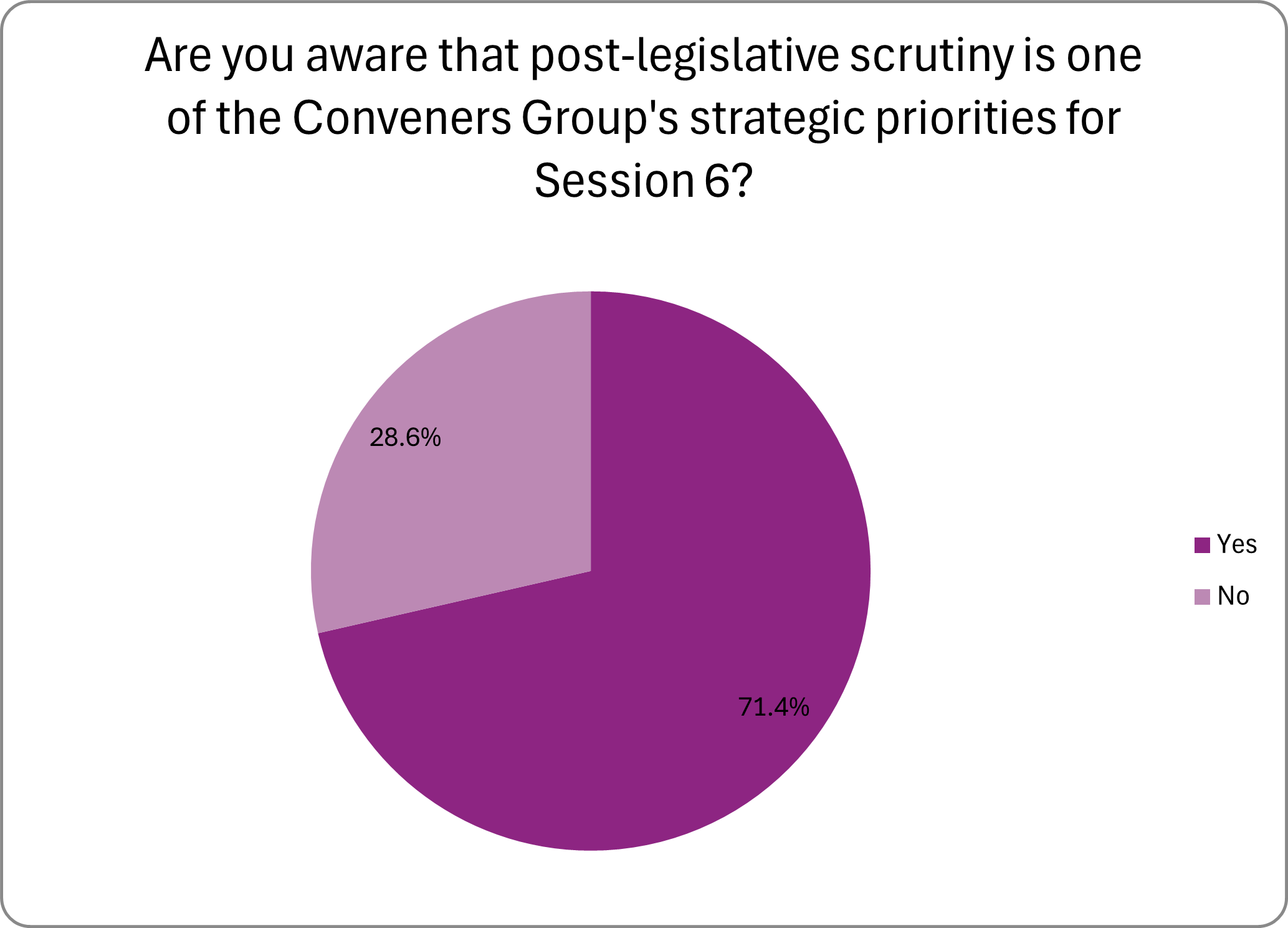

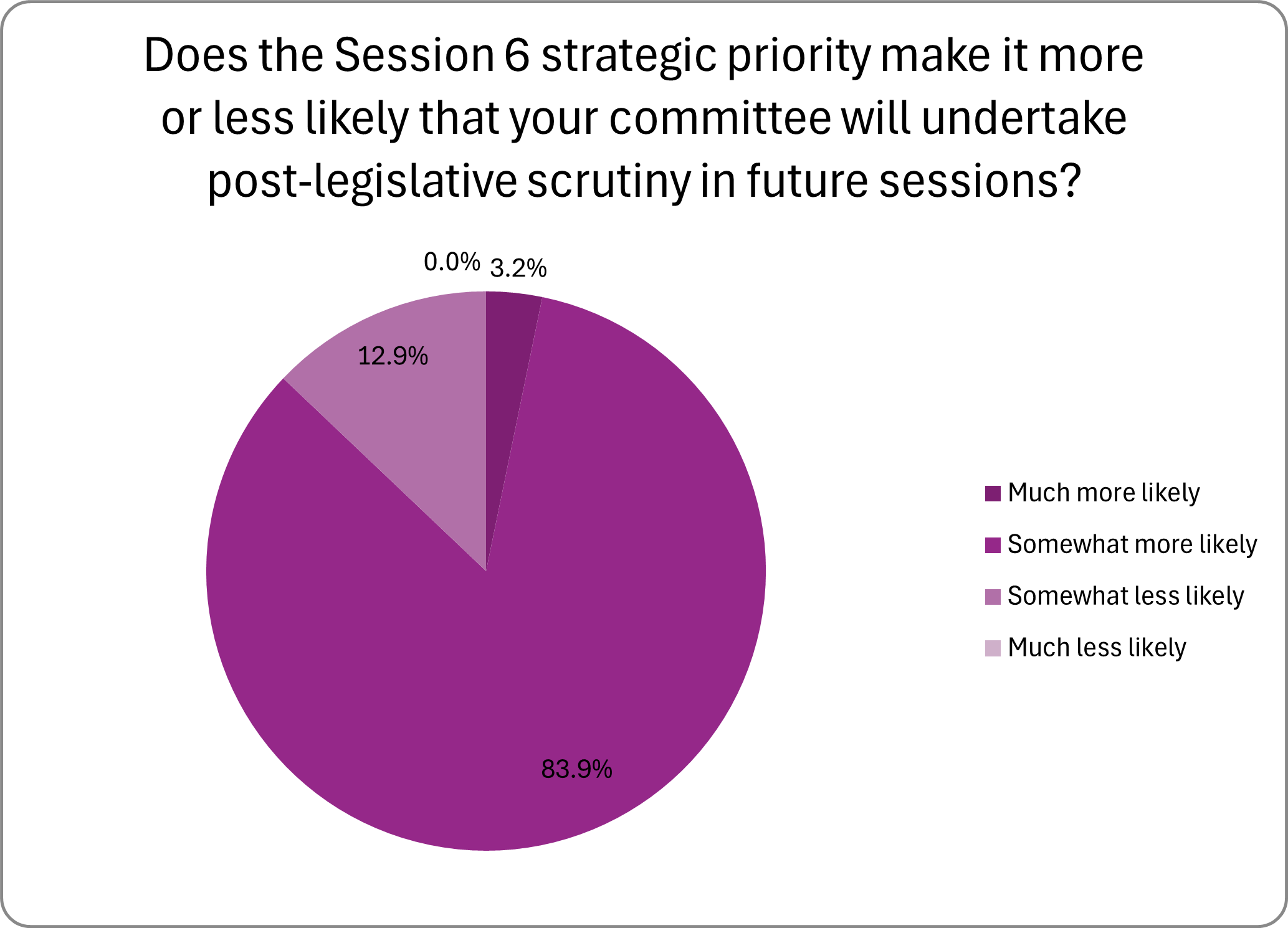

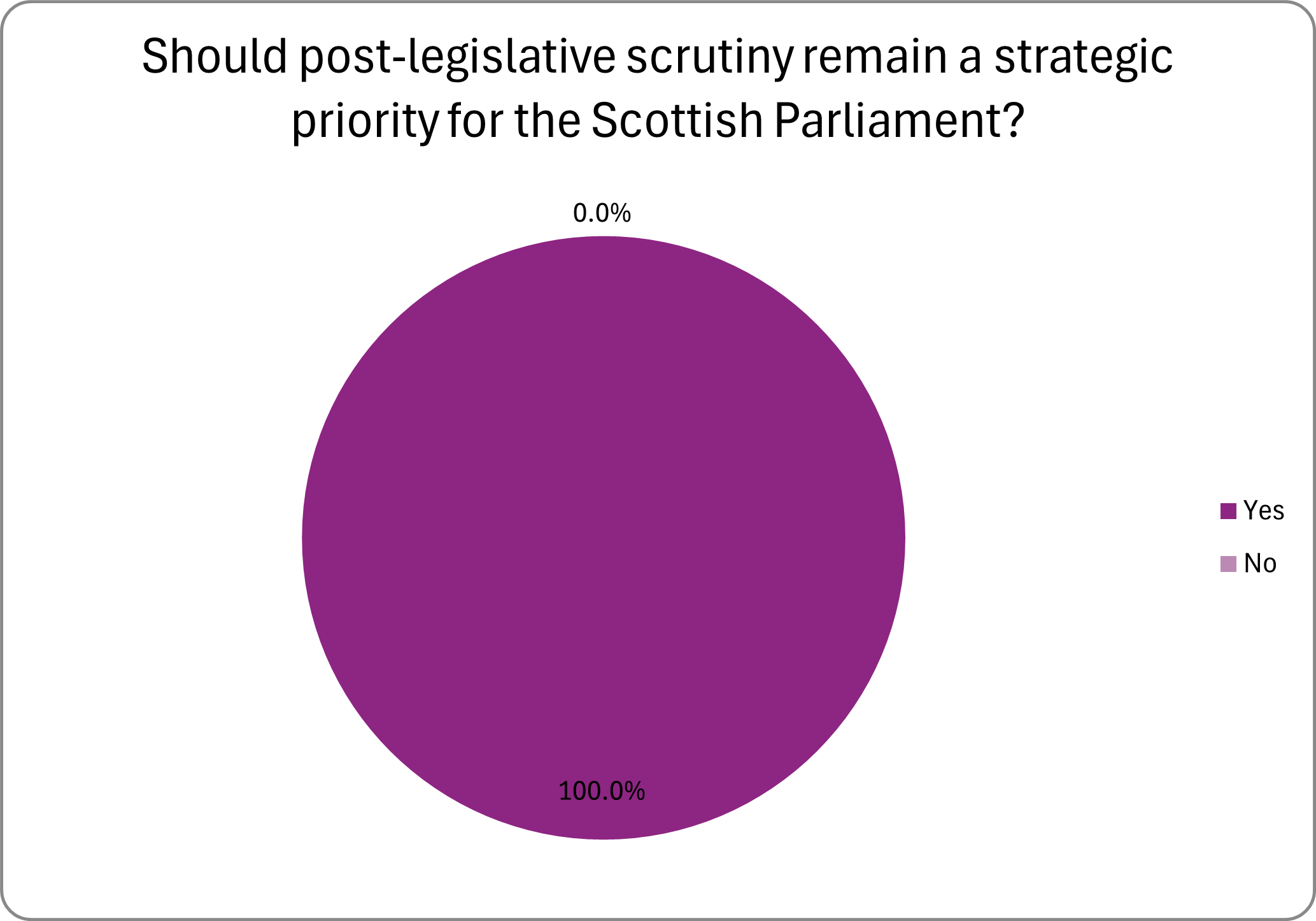

Hobbs, A., & Kerr, N. (2025, March 11). Delivering a model for parliamentary scrutiny of climate change: a Climate Change People’s Panel. Retrieved from https://spice-spotlight.scot/2025/03/11/delivering-a-model-for-parliamentary-scrutiny-of-climate-change-a-climate-change-peoples-panel/