Lived experience in the Scottish Parliament: three case studies

This briefing presents three case studies from research undertaken as part of an Academic Fellowship based with Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe) between January and July 2025. In this research, Dr Clementine Hill O'Connor (University of Glasgow) explored how lived experience has been integrated into the scrutiny work of the Scottish Parliament. This case study volume gives context to Dr Hill O'Connor's full research briefing, but also serves as a stand-alone reference tool on case study methodology and impact.

Overview

This briefing presents three case studies from research undertaken as part of an Academic Fellowship based with Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe) between January and July 2025.

In this research, Dr Clementine Hill O'Connor (University of Glasgow) explores how lived experience has been integrated into the scrutiny work of the Scottish Parliament, illustrated by three case studies. These draw on interviews with Parliament staff members, Committee members, and, in one case study, participants, as well as analysis of supporting documentation.

The purpose of these case studies is to offer an in-depth description of one of the many processes through which lived experience features in the work of Parliamentary Committees. The case studies examine engagement processes undertaken as part of three scrutiny activities:

Each case study is structured along similar lines, and offers an account of the steps taken to develop the approach and the decisions that had to be made to address particular challenges. The design and delivery model is explained, and outcomes of the processes of engagement are then explored. This includes looking at the impact of the process on the people involved, on the inquiry process, and on the committee's final recommendations and next steps. Finally, each case study concludes with lessons which can be drawn from the process.

Together, these case studies provide insight into the opportunities and challenges of embedding lived experience in parliamentary scrutiny, and highlight lessons for future practice in ensuring that processes are effective, transparent and ethical.

The combined lessons learned from the case studies, along with the wider research gathered through this fellowship, recommendations arising from interview discussions, and a suggested list of key questions to ask at the outset of considering the use of lived experience are included in the main briefing from the fellowship. Recognising that different audiences will engage differently with the varying aspects of the fellowship output, the main briefing has been published as a separate document to this case study volume.

As with all guest publications, the findings and conclusions of both this case study volume and the full briefing are the views of the author and not those of SPICe, or of the Scottish Parliament.

Context - committee scrutiny and support

All three case studies focus on activities which supported committee scrutiny. This section gives a brief overview of what this means, and those involved, to provide context for the case studies for those unfamiliar with the work of Scottish Parliament committees.

The Scottish Parliament has 15 committees, most of which focus on specific areas of policy. These committees will be responsible for the scrutiny of legislation and policy, which typically takes the form of an inquiry process. Some of this work will be allocated to committees, i.e., in the form of a draft bill, others will be determined by Scottish Government timetables (such as scrutiny of the Budget), and other inquiries will be proactively pursued by committees. Committees manage their own work programmes and decide how they will approach scrutiny of an issue or bill, including the timetable and how they will gather evidence. More detail on how committees work is available on the Parliament's website.

Approaches to incorporating lived experience in the scrutiny work of committees are developed and delivered by committee support staff. Committee support as a whole is led by teams of committee clerks, who manage work programmes, meetings and stakeholder relationships, provide direct support to conveners and members, and draft committee reports. Clerks draw on support from colleagues in other offices to create a wider support team. These services include research support from the Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe), and the Parliament's in-house Participation and Communities Team (PACT), as well as Communications Managers who help to promote committee work.

For each piece of scrutiny work, committee support teams will work together on scoping. This will involve background research, identifying the areas where a committee making recommendations may have the most impact, and understanding what evidence and voices are needed to help the committee understand and develop recommendations on a policy area or bill. Committees then consider the options presented and have the final say on an inquiry approach and who they take evidence from. The support team then works together to put the committee's chosen approach into action.

When incorporating lived experience into scrutiny, it is typically a Participation Specialist from PACT who takes the lead on building relationships. They use their connections within communities and the third sector to identify potential participants and support people to take part. This includes practical support such as making travel arrangements, designing and facilitating meetings and activities, helping people to understand their role in the process and feel prepared to take part, and providing wellbeing support in a trauma-informed way. Clerks and research staff will stay involved to provide context on both the committee's role, and the policy being explored. The role of the committee itself will vary - sometimes MSPs lead discussions, other times they act as participants, and in some cases they do not take part in the process directly. Where they don't take part, they instead respond to and use the outputs of lived experience processes delivered on their behalf by staff.

The use of lived experience sits within a wider process of evidence-taking, with more 'traditional' methods including seeking written views from stakeholders and the public in a "call for views", and taking oral evidence during committee meetings. This means that it will typically form part of an evidence base, rather than standing alone.

Recent work on Embedding Public Participation and Embedding Deliberative Democracy in the work of the Parliament, and on Strengthening Committees Effectiveness, provides wider context of how the Parliament is exploring and looking to strengthen it's scrutiny role.

Case study: inquiry into the Financial Considerations of Leaving an Abusive Relationship

In December 2024, the Social Justice and Social Security Committee agreed to carry out an inquiry into the Financial Considerations when Leaving an Abusive Relationship. The inquiry focused on:

the support local authorities give to women leaving abusive relationships;

how rules and practices related to the public sector and social security take account of the financial issues women can face when leaving abusive relationships; and,

how much information and advice is available from public bodies and charities.

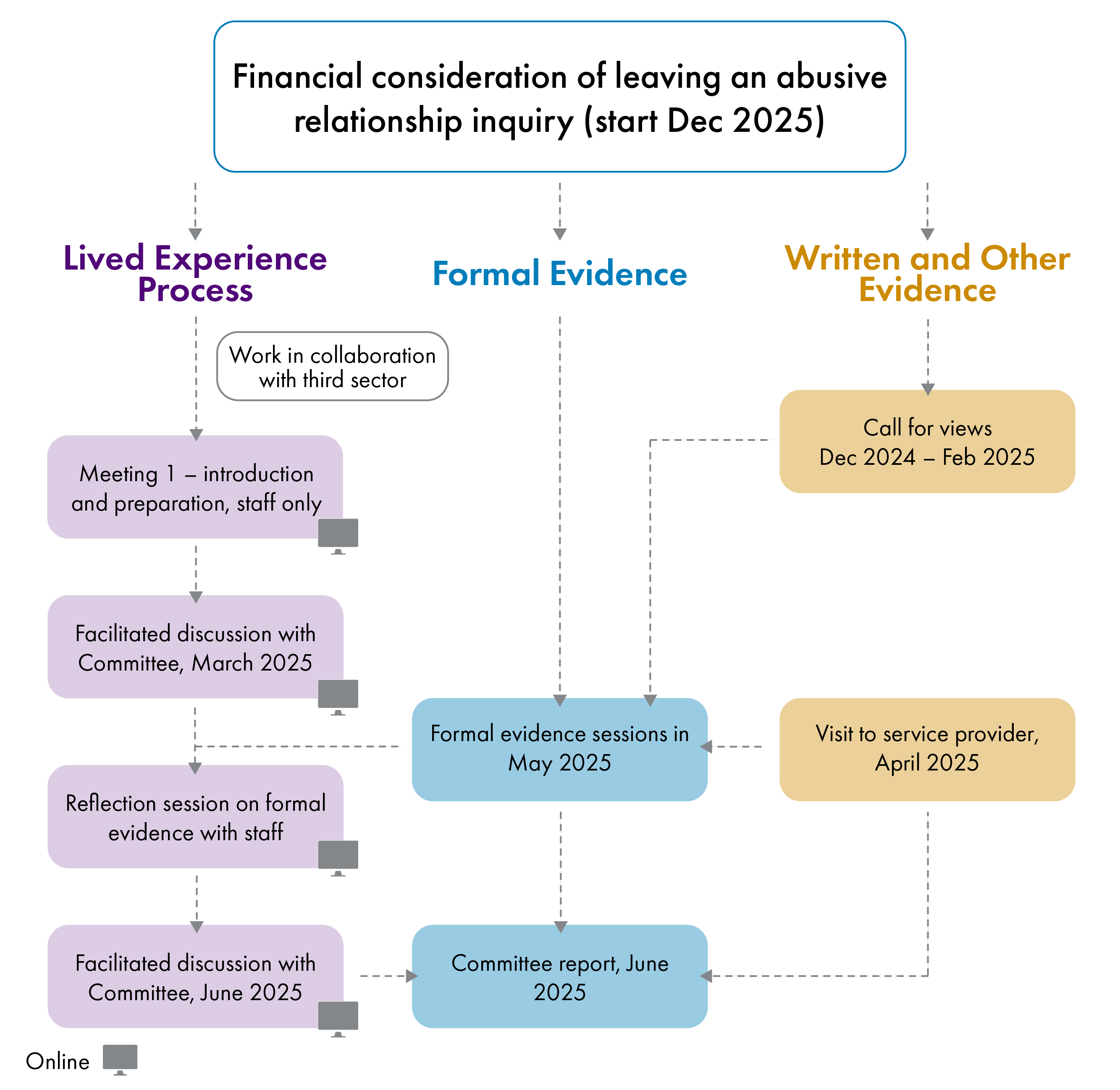

The approach to the inquiry included a call for views, two committee sessions with formal witnesses from relevant organisations, a visit to a service supporting people experiencing economic and financial abuse and a process of engagement with women with lived experience of domestic abuse.

The process of engagement consisted of four meetings with the Scottish Women's Aid Survivor Reference Group (SRG). One meeting served as an introductory session, followed by the meeting with members of the committee. The Committee then spent two weeks taking formal evidence before the group met to reflect on the evidence that had been presented. A final meeting was held for SRG to feed these reflections back to Committee members. The inquiry report was published on 9 July 2025.

Developing the approach

In the following sections, the key characteristics of the process are described, with some reflection on the rationales for the choices that were made. These are useful points to consider when designing future approaches to engaging people with lived experience.

Identifying a specific group to work with

Members of the clerking team, Participation and Communities Team (PACT) and Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe) worked together to design the specific approach that was taken. There were lots of discussions about the remit of the inquiry and the best group of people to engage on the subject. Time and resources were a consideration – if the remit covered too many areas, then there would need to be multiple processes of engagement across a variety of different groups. This would not only be time-consuming for the organising team, but also for the Committee, whose Members would have to find additional time outside of committee business to attend the informal meetings.

The following exchange in a focus group with Parliament staff members illustrates the balance that had to be taken:

Really, we would have wanted to go broader [but] there just wasn't the time to do that. You know, to have separate engagement with different groups of people who had experienced it.

Parliamentary staff member 1

But then you need different [third-sector] partners …you need the commitment for the committee…and sometimes that's tricky. So obviously the bigger you go, the more demands you make of their time.

Parliamentary staff member 2

It was agreed with the Committee that the approach would be one that related specifically to the concerns of women leaving abusive relationships and the support they have access to. Based on the experience and contacts of SPICe and PACT, it was decided that Scottish Women's Aid were the obvious organisation to work with.

Scottish Women's Aid run a Survivor Reference Group which is made up of individuals with lived experience of domestic abuse, some of whom have previously been involved in consultations and engagement processes with the Scottish Parliament.

Working alongside a third-sector organisation in this context was understood to be vital. Not only do they have links to individuals who have the lived experience to feed into the work of the committee, but they also have ongoing, supportive relationships with this group. This meant that everyone involved could be confident that there was the right support for the participants throughout the process.

We rely on them [Scottish Women's Aid] to carefully choose people who have the support and the distance to cope

Parliament staff member

This ensured that SRG members could participate safely in a process that required them to share traumatic experiences that risked triggering or re-traumatising them. In cases such as this, where the voices of those with lived experience are deemed crucial to the scrutiny process it is vital to consider the support and debriefing processes that are in place. Given resource limitations within the Scottish Parliament and the established relationships that exist, third-sector organisations are often better placed to offer this.

Negotiating the specifics

The process of agreeing the specifics of the approach taken was a series of negotiations and discussions such as those described above in terms of the trade-offs between resources and remit.

Scottish Women's Aid continued to play a key role in working with the team to design the approach. The SRG had previously been involved in the work of another parliamentary committee undertaking Stage One scrutiny of a bill in November 2022. This had been a difficult process for those involved. The eventual vote on this bill had gone against what the group had recommended, and they felt their views had not been taken seriously. This meant that Scottish Women's Aid wanted to ensure that the process for the inquiry into the Financial Considerations when Leaving an Abusive Relationship was designed and managed in such a way that set realistic expectations, offered the chance to feedback, and clearly demonstrated that the women's' experiences were adequately taken into account.

A series of four meetings, two with Committee members and two with the Parliament staff team was agreed on. This approach allowed time for the SRG to get to know the team and feel adequately prepared for the meetings with the Committee members. As one staff member described in the focus group:

I think working, you know, together [PACT, Clerks and SPICe] to prepare the women. I think that worked well. You know, and then they get to know us in between the meetings. And the fact that they could have the longer view

Parliament staff member

This way of working also meant that there was time for the SRG to feedback between meetings so that adaptations to the process could be made.

We could ask them how they wanted things to go, you know, at meeting one we could talk about meeting two and meeting three etcetera

Parliament staff member

This also gave the group a sense of ownership over the process rather than feeling they were being “wheeled in and wheeled out”.

All of these decisions had to be considered in the context of resources, time, and timelines. The committee has a specific time that they meet each week, they have a variety of bills to scrutinise and inquiries to conduct. It meets weekly when Parliament is sitting (there are recesses when the Parliament does not sit in February, July, August, October and December), and it is challenging for committees to meet outwith set meeting times, both because of restrictions of when committees can meet related to Chamber business, and because MSPs own need to balance committee work with time in their constituency and their other commitments as parliamentarians and party members.

This means that timelines can be tight and inflexible. It is a balancing act to meet the requirements of the committee, and ensure that there is adequate time for the engagement, and crucially, for the clerks to be able to feed evidence from the engagement sessions into the key documents for the committee, including briefings, suggested areas of focus for questions for formal witnesses and the final report.

Details of the approach

The engagement process consisted of four meetings set out in detail here.

Meeting One

This was an initial preparatory session with eightwomen from the SRG, Scottish Women's Aid and the members of the clerking team, SPICe and PACT who were involved in facilitating the process. The SRG watched a video that the Parliament Communications Office have developed to explain the role of the Scottish Parliament. One of the SRG members noted how valuable this had been:

I also found it really helpful when she played the little clips about what Parliament, what government is at the very beginning, […] it was just a great reminder and sort of really set us up in a very, you know, practical way on who's who and what we're going to be doing.

Participant from informal engagement session

The second focus of the meeting was a discussion with the SRG about the themes and questions that they wanted to explore with Committee members in meeting two. These were taken initially from the Call for Views, and the SRG were asked if there were any additional themes they wanted to consider. The group agreed how best to prioritise the themes so that they got the opportunity to focus on those that they felt were the most important.

Meeting Two

This was held online prior to Committee members hearing formal on-the-record evidence from witnesses in Committee meetings. The SRG members were divided into two groups, each had a note taker and a Committee member who facilitated the discussions. The two groups each had a set of questions that Committee members asked them, based on the themes and priorities that had been agreed in meeting 1. Both groups were asked about legal aid, social security, the role of government and advice and services. In addition, one group also addressed no recourse to public funds and debt the second group addressed Equally Safe and the role of police.

Meeting Three

This meeting was held after all the formal evidence had been taken. Staff worked together to summarise the evidence in a paper that was circulated prior to the meeting. During the meeting the SRG members watched some key clips from the sessions and gave their perspective on the issues that were raised.

Parliament staff also set out the focus and format of meeting four, the final engagement with the Committee. The SRG were presented with a couple of different options for feeding back their reflections on the evidence and they decided to take a similar approach to meeting two. It had been suggested that the SRG might present their views and arrangements had been made for an additional meeting to support this. However, the SRG members were clear that they would prefer to respond to specific questions from the Committee members.

Meeting Four

This meeting took a similar format to meeting two. The SRG members were divided into two groups, each had a note taker and an MSP to facilitate the discussions. The two groups worked through the same set of six themes. Staff from SPICe took responsibility for writing the questions for each theme, ensuring that they were framed as a prompt for the SRG members to reflect the discussions from meeting three. Time was provided at the end of the meeting for the women from the SRG to raise any issues that had not been discussed during the meeting.

Outcomes and (early) impact

The inquiry concluded in June 2025, and the report was published on 9 July. As such, there is a limit to the extent of the impact that can be achieved in such a short space of time. Nevertheless, through interviews with staff, Committee members and the women who took part there are some early and important indications of positive impacts on relationships between citizens and Parliament and on the rigour of the overall scrutiny process. This case study offers some important developments in best practice for consideration for others working in this area (in the Scottish Parliament as well as elsewhere).

Impact on SRG members

All of the women described the emotional toll of recounting traumatic incidents and discussed what made it worth it for them to participate when there was a risk to their emotional and mental health. However, they all felt very positive about their participation in the inquiry into Financial Considerations when Leaving an Abusive Relationship and a key reason for this was that they felt the process had been respectful throughout.

I felt, like it was really taken seriously. That what they were doing […] to listen to us and to have our lived experience. So I felt like that thoroughness really gave our stories and the issues the respect it deserves.

Participant from informal engagement session

I thought they were respectful of us, of our time and also of our experiences. And I think a lot of people aren't always like they forget that we've actually lived through these things. And it's been really hard and traumatic.

Participant from informal engagement session

They were so respectful, and I think they listened well, and it felt like they were going to carry forward what we were saying.

Participant from informal engagement session

Given that some of the members who participated in this inquiry had felt let down after their involvement in the Stage 1 scrutiny of a bill in November 2022, this was significant for repairing some of the relationships between this group and the Scottish Parliament. The key issue that had been previously identified, and informed much of the way this process was designed and carried out, was that there had been a mismatch between expected and actual outcomes for those involved. The staff team had been cognisant of this and sought to reiterate the limits of the impact that the inquiry could have on overall policy. This was evidently well received and understood by the SRG members who talked about feeling like their expectations had been well managed. This was echoed in a response to the PACT feedback survey:

MSPs were well engaged with the topic and spoke in a sensitive and informed manner. They clearly respected our opinions, and were open about the limitations of what they could achieve and how they would progress issues.

Participant from informal engagement session

Impact on the engagement with, and assessment of, formal evidence

The report states that the points made in the first meeting between the SRG and Committee members were “used to inform questions asked of witnesses during the oral evidence sessions”. This was reflected in the focus group with staff members and interviews with the Committee members. The SRG also noticed this in their reflections on the formal evidence. They agreed that, as highlighted above, they felt their experiences had been respected and this in turn had been carried through to the questions that were asked of the formal witnesses:

When I got to watch the videos. That was super, I thought. You know, they've really taken on board what we've said, and they're holding the ministers to account. And that was really empowering. Because I kind of thought you know what? They're not just sitting there nodding their heads going. Yeah, whatever, you're actually really committed to taking things forward for us is, was my impression.

Participant from informal engagement session

The design of the engagement process, with meetings between the SRG members and committee members serving to ‘bookend’ the formal evidence sessions had an impact on the way that members were able to assess and scrutinise the evidence they heard. One MSP said that it had served as a way to ‘test’ the formal evidence. They described it as being:

actually really helpful because they [the SRG members] were able to say ‘it doesn't happen’. Or that it might be the theory, but in practice, this is what happens.

Committee member

This approach of using insights from people with lived experience of using a service to check the reality of particular services or policies is incredibly valuable in the context of scrutiny. This adds an extra component to scrutiny, ensuring that policies and processes are achieving the things they were designed to do.

Impact on the recommendations and next steps

Two of the recommendations that appear in the Committee's report make direct reference to the SRG. Both clearly draw the link between what the committee heard and the specific recommendations they are making in response.

Members of the SRG were clear that victim/survivors should not have to worry about school meal debt. We would therefore like the Scottish Government to provide an update on action it is taking to ensure all local authorities access the School Meal Debt Fund.

Inquiry Into Financial Considerations When Leaving an Abusive Relationship Report, para. 271

Evidence we took from members of the SRG, as well as through written and oral evidence, indicated that knowledge of the legal aid system amongst solicitors needs to be improved. SLAB should therefore work with the Law Society of Scotland to improve this.

Inquiry Into Financial Considerations When Leaving an Abusive Relationship Report, para. 345

It is important to note that both of these recommendations came from the fourth meeting in which SRG members met with Committee members to reflect on the formal evidence that had been given. This gave the SRG members the chance to respond and indirectly challenge the formal witnesses, bringing in their lived experience of being in debt and attempting to access support from the Scottish Legal Aid Board (SLAB). These are not necessarily recommendations that the committee would have come to without the specific perspective of the SRG members. These insights have offered an additional level of rigour to the scrutiny process.

One of the key themes that came from the SRG was the role of police in relation to the experiences of leaving an abusive relationship. Whilst this was outside of the remit of the Social Justice and Social Security Committee it was clearly identified as an issue and the Committee committed to following up on this. There is a dedicated section in the report that outlines the issues reported by the SRG and the letter that the Committee sent to Police Scotland to follow up (8 April 2025). The letter also directly referenced the lived experience evidence that had been taken.

The report sets out that the whilst the Committee welcomes the approach taken, it also recognises that "there seems to be a gap between the stated approach and victim/survivors anecdotal experiences" (para. 448). The Committee makes a further two recommendations related to these issues, pushing further on the requests for assessment of the approach taken by Police Scotland and for information on the use of lived experience engagement to improve the service.

Lessons to draw from the case study

Managing Expectations

Managing the expectations of SRG members was crucial throughout the engagement process. Using the video that explains the role of Scottish Parliament and the difference between Parliament and Government set the foundations for this.

The repeat reminders across the four meetings that set out the full inquiry process were also helpful. However, a key part that came through was that these reminders and explanations are more effective when they also come from MSPs. SRG members appreciated the openness and honesty, even when Committee members were stating the limits of their power and scope for change.

Clear references to input and impact of lived experience

Throughout the inquiry report there are explicit references to the evidence from the SRG and examples of impact on the way that the Committee proceeded through the inquiry, the recommendations it made and the actions it has taken. There were also references to the experience of the SRG members in correspondence with Police Scotland.

Having a clear audit trail in this way supports attempts to evidence the impact of lived experience. It serves as a way to get the voices and views of people ‘on the record’ rather than in anonymised summary notes that can be easy to miss. This approach also allows for a clear way to feedback to those who have participated in the engagement process.

‘Book-ending’ formal evidence

It was evident that the design of the engagement was deemed valuable for both MSPs and the SRG members. It added an extra dimension to scrutiny and gave SRG members a more meaningful engagement across the whole process.

Given some of the pressures on timing, there were some mixed perspectives on this approach as a whole. Nevertheless, it is an approach which can clearly illustrate two of the potential roles that insights from people with lived experience can play in committee processes:

to set the context and guide subsequent formal evidence, and

to challenge, feedback and provide an alternative perspective to formal evidence.

This case study offers ways of thinking about different types of approaches, encouraging clerking teams and committees to think about what specific set of insights and contributions will support the work they are doing.

Case study: Right to (Addiction) Recovery (Scotland) Bill

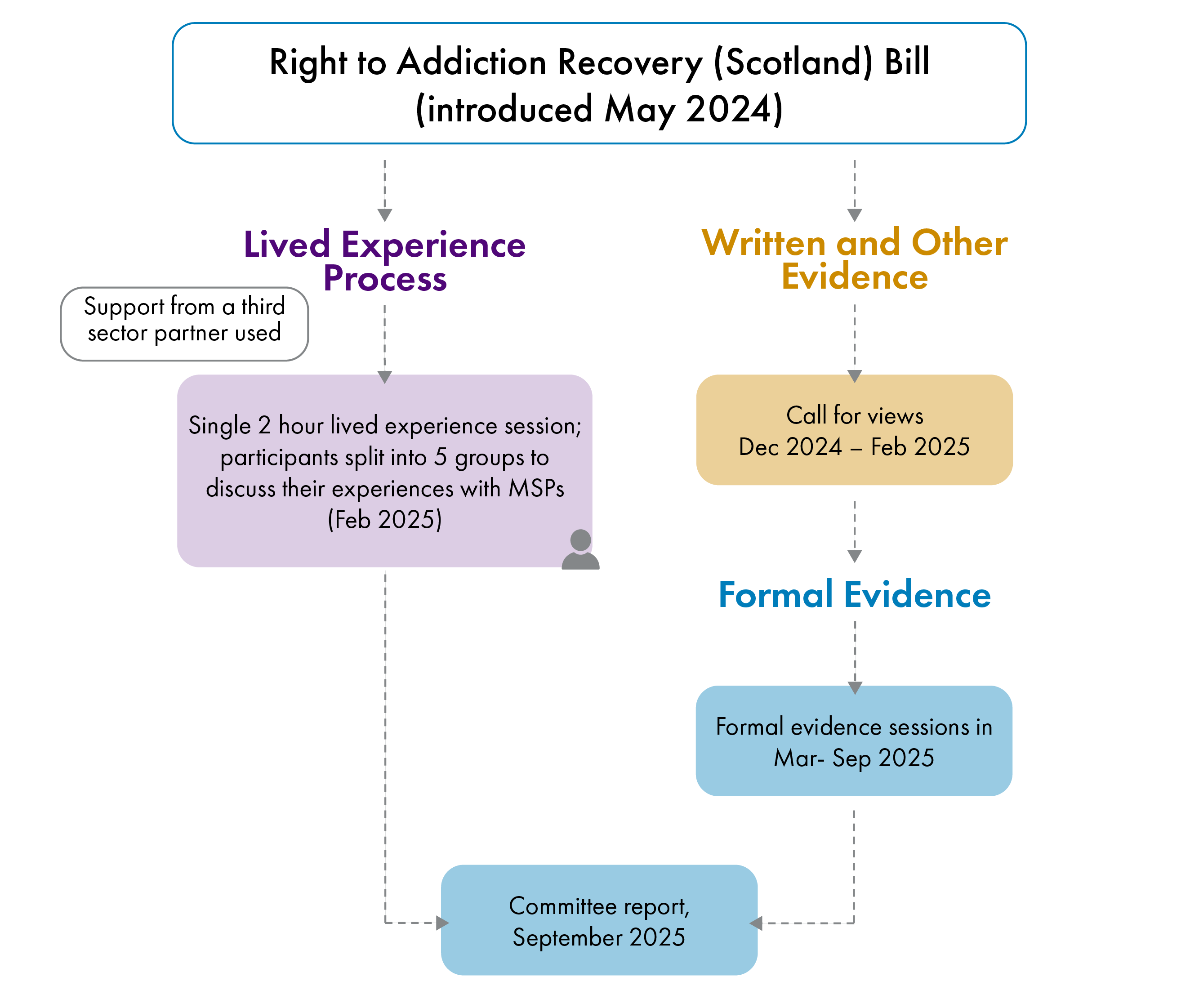

The Right to (Addiction) Recovery (Scotland) Bill was a Member's Bill introduced by Douglas Ross MSP in May 2024. The Stage 1 report was published in September 2025 and a debate and vote took place on 9 October 2025. During this vote the Parliament did not agree to the general principles of the Bill, meaning that it fell and did not progress to Stage 2.

The lead committee was the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee, which held a call for views between November and December 2024, followed by five public evidence sessions. The Stage 1 scrutiny process also included an informal engagement session with people who had lived experience of recovery from alcohol and/or drug addiction.

This case study will focus on the informal engagement session that was organised by the Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe), the Participation and Communities Team (PACT) and the clerking team (“committee support staff”) in February 2025. Analysis of publicly available reports has been supplemented by interviews with members of staff supporting the engagement, and with Committee members.

Details of the approach

In the following sections, the key characteristics of the process are described, with some reflection on the rationales for the choices that were made. These are useful points to consider when designing future approaches to engaging people with lived experience.

In-person discussion groups

The engagement session with people who had lived experience of recovery from alcohol and/or drug addiction was held in person at the Scottish Parliament in February 2025. There were 17 participants, split into five groups, which each spent two hours discussing their views of the Bill with Committee members (who also facilitated the discussions). Anonymised notes were taken by Committee support staff and made public on the Scottish Parliament website.

When diaries are busy and Committee members have a variety of other roles and commitments, committee support staff noted in interviews that organising sessions during committee time (rather than, for example, in the evenings) often means a better turn out. Therefore, the decision was made to hold this engagement session in person, during the Committee's normal weekly meeting slot on a Tuesday morning, to ensure that Committee members could prioritise attendance.

The five groups remained with the same Committee member for the full two hours, as opposed to other formats where participants and/or Committee members move tables to hear a variety of different perspectives. The rationale was that this allowed for a level of familiarity and confidence to build up so that participants weren't repeating their experiences, and there was time for the discussions to go deeper. This is reflected in comments from one of the participating Committee members:

… the pros of it would probably be that it [was] a smaller intimate group of people who would be able to actually discuss easier than in a big group […] that kind of intimate setting of it allowing a more fulsome discussion with a smaller group of people is a positive.

Committee member

The engagement session was well attended by both Committee members and people with lived experience; however it is worth noting that such an approach has its risks. If people have jobs, caring responsibilities, or are based outside of the Central Belt, being in the Scottish Parliament building for 10am on a weekday morning might be a challenge. In making decisions around the timing of engagement sessions, parliament staff are therefore often making a trade-off between the likelihood of members attending, and the potential needs of participants.

Choice of participants

The Right to (Addiction) Recovery Bill was initially consulted on as part of the Member's Bill development process. The launch of the consultation prompted public statements from prominent drugs charities, including the Scottish Drugs Forum, who were opposed to the principles of the Bill. This was reflected in the SPICe summary of the Committee's own call for views, in that the majority of organisational responses disagreed with the purpose and extent of the Bill. In contrast, the individuals who responded to the call for views overwhelmingly agreed with the purpose and extent of the Bill.

In this case, as in others, the Committee support team relied on the connections and capacity of third-sector organisations to facilitate links to people with lived experience of addiction. The following quote from a Parliament staff member outlines this in more detail:

[I]t's helpful to [work with the third sector to] recruit participants, but also from safeguarding perspectives so that they can support the participants before, during and after and also helps with planning and safeguarding because they often have a relationship with the participants. And they can help plan, and we work with them to plan it so that we can tailor it specifically for the participants that they have. And so that they're comfortable. So yeah, it will start the team identifying organisations that might be able to help.

Parliament staff member

When considering which organisations to work with, the Committee support team had to consider the positions that potential partner organisations had taken on the Bill in the call for views to make sure that a balance of views was represented.

The five chosen organisations identified people who would be able to take part in the session, and there were numerous interactions between the organisations and the committee support team to consult on the language used and the key questions that would be discussed. Organisations were asked to make sure that a range of views and experiences were included.

One of the challenges of working with well-known organisations, particularly in specific areas such as addiction services, is that there are a limited number of people able and willing to participate in engagement sessions such as this. This was reflected when one of the Committee members noted that they had already met with many of the people in the room through other engagement processes. However, another Committee member said that they had been able to hear a whole new set of perspectives from people and organisations that they had not met with previously. As a result of the process, they said "after that session I actually really looked at in in a different way".

Outcomes and (early) impact

The Committee's Stage 1 report concluded that, having heard all of the evidence, it could not recommend that the general principles of the Bill be agreed to. However, the Committee were not unanimous on this recommendation, and it went to a vote with 6 votes for, 1 vote against and 2 abstentions. At the Stage 1 debate, which took place on 9 October 2025, the Parliament also did not agree to the general principles of the Bill, with 52 MSPs voting for, and 63 MSPs voting against the motion (0 abstained, 14 did not vote).

It is difficult to assess the extent that lived experience, or indeed other forms of evidence, had an impact on how individual members voted, either in agreeing the Stage 1 report, or following the debate. Ideally, Committee members might make a clear, publicly available statement of why they had voted in a particular way, and point to specific pieces of evidence that convinced them one way or another. In reality, that is not practical, nor is it necessarily reasonable to expect committee members to be able to do that when they have read and heard a large volume of information from across a wide range of sources of evidence.

It may not be possible because of this to assess the impact of the process on a specific decision or vote. However, the interviews with Committee members and support staff which took place while Stage 1 was still ongoing can illustrate the influence that lived experience of drug/alcohol addiction had on the process of scrutiny.

Encouraging new perspectives

One of the Committee members interviewed shared their reflections of the engagement with people with lived experience and the extent to which this had shaped their thinking and lines of inquiry with witnesses, particularly the Scottish Government, in formal evidence-taking. Having been someone who, in previous roles, was well-acquainted with the discussions and debates around recovery services, they had a particular view and set of opinions. They explained that they had "set aside" those views and "let go of the biases" that they had formed. They said that "listening to that lived experience […] has made me start to really push witnesses around how people can actually realise their rights […] So it's taken my questions in a completely different way because of what I heard".

This is an important illustration of the power that lived experience can have, when it offers a new perspective and, crucially, when Committee members are committed to being open and acknowledging some of the potential biases or preconceptions they might have on a particular issue.

Influencing amendments

Another Committee member described how they approached the engagement session with people with lived experience of drug/alcohol addiction:

I've got my notepad that I take in there and I'm sitting writing down the potential amendments to the Bill directly from input from people with lived experience.

Committee member

This Committee member, in alignment with other committee members and parliament staff members across the case studies, saw real value in lived experience as a way to check the extent to which Bills realistically meet the needs of the people that they are intended to support. As such, amendments were described as a way to achieve this, using the insights of people with lived experience of drug/alcohol addiction to inform changes that will ensure that Bills are "compatible and viable for those who we're trying to help".

This is another important illustration of the ways that lived experience can support new ways of thinking, and how it has the potential to strengthen bills as they work their way through the Parliamentary process.

An additional source of evidence

The Committee's Stage 1 report references the input of people with lived experience of drug/alcohol addiction as an additional form of evidence. The report notes that one of the issues raised by people with lived experience of drug/alcohol addiction was concern about the medical model that underpins the approach proposed in the Bill and the reliance on GPs, who may lack expertise, to make recommendations about treatment. This is set alongside references to written submissions made in response to the Committee's call for views, and quotes from various formal witnesses. This body of evidence, collectively, appears to have informed some of the key questions to the member in charge of proposing the Bill who was asked to respond to these specific concerns when appearing before the Committee.

The report also highlights a series of concerns that were raised with regards to the impact of the Bill on the healthcare workforce. People with lived experience of drug/alcohol addiction were concerned that “typically short GP appointments” were inappropriate in this situation (where someone is seeking assessment for treatment options) and queried "GPs' capacity to be able to offer the longer appointment required". As above, this is set in the context of other sources of evidence that highlight similar issues. This leads to a series of notes from the Committee related to the issues raised and the conclusion that "the Bill's potential impact on the workforces must be carefully assessed" in the context of the current strain on the healthcare workforce that was described by many (including people with lived experience).

These examples show where the views of people with lived experience are an additional source of evidence, used alongside other sources to strengthen claims and arguments made throughout the report.

Lessons to draw from the case study

The importance of new and alternative perspectives

The examples of the experiences of Committee members illustrate the importance of new perspectives in the scrutiny process. For instance, a new set of perspectives can shift the focus and offer alternative lines of inquiry to approach bills from a different angle. The second example highlights the ways that members can approach engagement sessions with people with lived experience with the aim of strengthening legislation and ensuring that it meets the needs of those it is trying to help. In both examples, Committee members have shown a commitment to hearing from and, crucially, learning from people who have lived experience. Encouraging, supporting and giving Committee members the skills to approach scrutiny in this way was a consistent theme of the recommendations that were suggested by interviewees across the case studies. As the Standards, Procedure and Public Appointments (SPPA) Committee highlights in its report on Strengthening Committee Effectiveness, “If a member enters the ‘committee arena’ with the necessary support, knowledge and skills needed in their role, they will perform with confidence and ability”. The induction programme at the start of Session 7 provides an opportunity to support members in developing skills relating to building lived experience into scrutiny.

Working with Committee Members to identify missing perspectives

Given the importance of new and alternative perspectives, and the note from one Committee member that they had not heard anything new, it is important for committee support teams to work closely with committee members to explore and identify the perspectives that they are missing from their understanding. This again connects in with findings of the SPPA Committee on Committee Effectiveness, which recommended that:

each committee should set objectives for the individual pieces of scrutiny and inquiry work it conducts. This approach will further assist in members working collegiately to deliver shared objectives. We also consider it will encourage more time to be built into the scoping stage of inquiries to ensure the most appropriate methods of evidence taking and engagement are used.

Standards, Procedures and Public Appointments Committee, Strengthening Committee Effectiveness, para. 97

The knowledge and perspectives existing or missing may differ from one MSP to another, but for lived experience to have the kinds of value illustrated in this case study, it may well be necessary to cast the net more widely when identifying groups to work with and invite into engagement processes. One Committee member had a specific recommendation around this issue:

I think we probably need to reach out to organisations who have not got real links currently with the Parliament […] I actually think that some of the work that we're needing to do, if we really want to get more lived experience, is work with some of these [smaller] third-sector organisations who are embedded in their communities.

Committee member

Since this interview the Participation and Communities Team have published a report, "Approach to Working with Communities", based on its experiences of participation work, evaluations from events with the communities sector, and feedback from the Presiding Officer's 25th Anniversary programme of regional visits. One of the key actions in the 12-month plan that is set out in the report is to commit to:

proactively scoping and researching excluded and marginalised communities, identifying missing voices, (whether by geography, identity or shared interest), building relationships and establishing new connections.

Participation and Communities Team, Approach to Working with Communities

This set of activities directly aligns with the suggestion from the Committee member noted above, as well as responding to calls from communities about how they can be more involved in the Parliament. They show that there exists a clear commitment to continue to develop good practice in encouraging a more diverse set of perspectives into the Parliament more broadly, and specifically into committee processes, and that the practice expertise to do so already exists within the Parliament.

Case study: Housing (Scotland) Bill

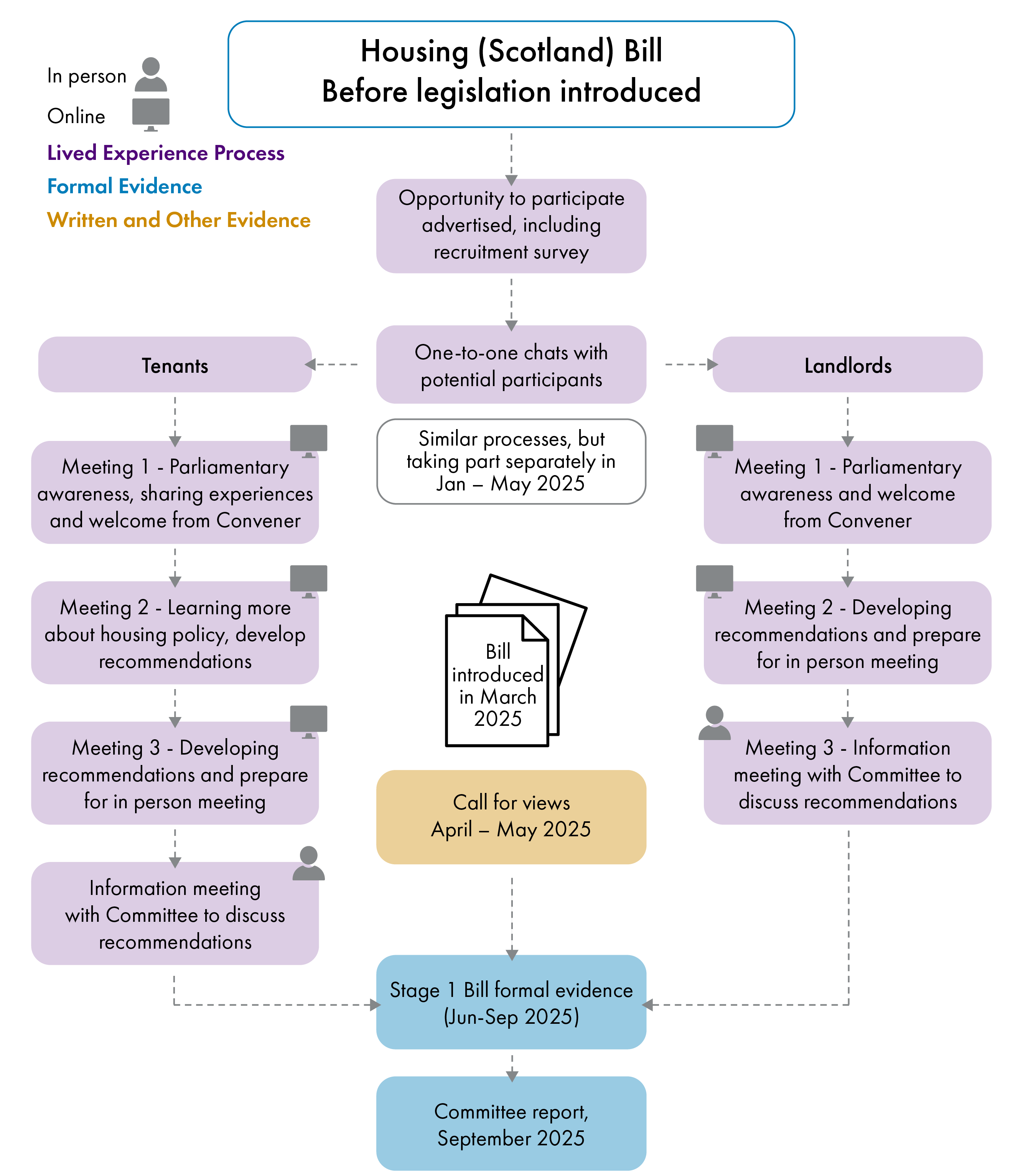

The Housing (Scotland) Bill was introduced in March 2024, and passed by the Scottish Parliament on 30 September 2025. The lead committee for the scrutiny of the Bill was the Local Government, Housing and Planning Committee. The Social Justice and Social Security Committee conducted scrutiny focused on the parts of the Bill that align with their remit: homelessness prevention (part 5) and fuel poverty (part 6).

This case study will focus on the work undertaken by the Local Government, Housing and Planning Committee, which convened two separate Lived Experience Panels to prepare for and support its Stage 1 scrutiny of the Bill. The panels met between January and May 2024.

One panel was made up of tenants, and the other was made up of landlords, both from the private rented sector. The panel process ran alongside a call for views, and the Committee also held six formal evidence sessions in public. The panels each met multiple times online to develop a series of recommendations that they then presented to the Committee in person. Following the publication of the details of the rent control component of the Bill in November 2024, panel members were invited back to give evidence at a public Committee meeting in January 2025.

Developing the panel approach

The approach was developed before the Housing (Scotland) Bill was introduced. The Committee knew that the Bill would be introduced in Session 6 of the Scottish Parliament but was unsure of exactly when. Typically, committees will wait until the introduction of a bill to take evidence. In this case, the Committee agreed that it would be useful to explore the context of the private rented sector in advance so that:

when the Bill came through they (the Committee) would be able to test it against some of the things that they'd heard from the panel.

Parliament staff member

In effect, the process was designed to ensure that the Committee could assess the extent to which the Bill could tackle the issues faced by tenants and landlords.

Unlike other approaches to lived experience, including those featured in the other case studies explored in this research project, the panels were not supported or convened via third-sector organisations. As described in the case study on the inquiry into the financial considerations when leaving an abusive relationship, third-sector organisations can be a source of support for people participating in lived experience panels and engagement processes. They also provide key links between parliamentary staff (most often via PACT) and the communities affected by a bill or the issue under inquiry. In the case of the Housing (Scotland) Bill, the remit of the panels was relatively broad across two key groups 1) Landlords from the Private Rented Sector and 2) Tenants in the Private Rented Sector). Although were some early discussions about and with potential third-sector partners, they had limited resources and, in some cases, were more focused on specific parts of the Bill, i.e., homelessness prevention. The responsibility for the scrutiny of these provisions lay with another committee. This meant that there was not an obvious third-sector partner.

Members of the Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe), PACT and the clerking team worked with a range of organisations to promote the opportunity for tenants and landlords to apply to join one of the panels. Panel members were recruited via a range of relevant organisations with links to tenants and landlords (including Shelter, Indigo House, Crisis, Living Rent and Student Accommodation providers for tenants and Scottish Tenant Farmers, Scottish Association of Landlords and Scottish Property Federation for Landlords). In total there were 91 landlords and 37 tenants who applied to take part.

Applicants to both panels were asked to complete a survey which was designed by committee support staff and agreed for use by the Committee. The ambition was not to be representative of the population – panel members were instead chosen to represent people with a diverse set of perspectives and experiences.

whether it's a rural landlord, or somebody who owns multiple properties, so getting a balance of different perspectives […] the tenant side of it you might get somebody who is a student who's new to renting, or somebody at the other end of the spectrum who might have been renting property for 30 years.

Parliament staff member

One-to-one meetings were held with prospective panel members to offer further support and to help individuals to understand the purpose and format of the process they were agreeing to.

Details of the approach

In the following sections, the key characteristics of the process are described, with some reflection on the rationales for the choices that were made. These are useful points to consider when designing future approaches to engaging people with lived experience.

Limited direct involvement of MSPs

Each panel followed the same process of online meetings, separate to one another. The Convener of the Local Government, Housing and Planning Committee joined an initial meeting to welcome the panel members. The rest of the meetings were held with no committee members present, until the panels came to the Parliament in May 2024 to present their recommendations.

The choice to have most of the meetings without any MSPs was a key decision that required some consideration. Given the range of pressures on the time of Committee members it would not have been feasible to expect them to attend and engage with all of the meetings with the panels. However, it was vital for there to be a meaningful amount of time for the Committee to hear from the panels. Initially there was some surprise from Committee members that there were so many meetings being held without members present, but when talking through the whole approach they recognised the value in giving the panels the time and space to understand the process and get to a point where they could share their views confidently and clearly. This was echoed in interviews with parliamentary staff involved as they described the rationale for the approach taken:

the earlier sessions weren't so much about sharing with the Committee, they were about helping them [the panel members] work together to understand what the view that they wanted to express the Committee was, and understanding how they worked well as a group. I suppose [there was] the kind of view that if members [had been] involved at the beginning perhaps that would have been more challenging to do. By giving them the space to work together to come to what […] views [...] they wanted to share with the Committee was an effective use of time […]. But still not taking away from that opportunity for members to hear what they wanted to say because […] ultimately all of those earlier meetings were condensed into the key issues that they wanted to share with the Committee.

Parliament staff member

SPICe, PACT and the Clerking team worked together to facilitate the sessions. SPICe researchers briefed the panels on the overall content of the Bill and were able to offer specialist and technical insights where necessary. The panels each had two meetings which were designed and facilitated to support them to come to a collective agreement on a set of recommendations from the respective positions as landlords or tenants. The recommendations from each of the panels were published separately:

Outputs

The two Lived Experience Panels each produced a set of recommendations that were presented to the Local Government, Housing and Planning Committee. The members of the Panel had the chance to meet with Committee members informally and, in groups of three or four discussed the recommendations in more detail. This face-to-face engagement at the end of the process was important and, as described by staff involved in the process:

was a chance for members to explore in more detail what came out in the groups and for them [members of the Lived Experience Panel] to share in more detail […] and I think it's certainly opened some members eyes to some things.

Parliament staff member

Whilst this was a key part of the process, there are no written outputs from this meeting. The sole public output from the Lived Experience Panels is the series of recommendations.

Many of the recommendations are in direct opposition to one another. For example, the Tenants Lived Experience Panel recommended several changes around rent caps and rent controls. This included the specific recommendation “that rents and rent increases should be tied to tenants’ income and that rents should still be affordable to tenants earning minimum wage”. In contrast the Landlords Lived Experience Panel stated clearly and definitively that “the panel does not support the introduction of rent controls”. This significant difference between views was highlighted in the Committee's Stage 1 report, noting that the rent controls were “the most contentious aspect of the Bill during the Committee's scrutiny” (para. 100). Whilst there may have been some assessment or discussion of the differences in recommendations, there is no evidence of it in the formal outputs from the scrutiny process.

Ongoing engagement

It was important for the format to include an element of ongoing engagement which was described as follows:

the Committee was able to test […] what these will mean, and understood […] from the tenants perspective what this would mean as well as from the landlords one. So, I do think it added an awful lot to the Committee's understanding of the challenges faced by both groups as it as it made […] its conclusions on the on the Bill at Stage 1. Obviously, we're still going with the process. […] the committee hasn't considered amendments at Stage 2 yet. But [it] did hear from representatives as part of reflecting on the amendments at Stage 2. So […] it's not the end yet. The committee is continuing to draw on what it heard from […] the people involved in the groups and hopefully it's built up a rapport with people that it can continue to go back [to the panels] for the rest of the Session.

Parliament staff member

The ability to reconnect with members of the panel proved crucial as there were some issues with the timing of the Bill and the specific details of the rent cap, a key part of the Bill and arguably the most contentious part. In the Chamber debate on 28 November, it was noted that details of the rent cap had not been submitted by the Scottish Government in time for the Committee to include this as part of the Stage 1 scrutiny process. During the debate the Convener welcomed the details that has since been offered, and the Committee held a further meeting in January 2025 to hear from witnesses on the subject of the rent cap, which included evidence from members of the panels. Two members of the tenants panel joined the first witness panel of the meeting, and the two members of the landlord panel joined the second witness panel of the meeting.

Outcomes and (early) impact

Challenges in understanding impact

Between the first panel meetings taking place in January 2024, and the Bill passing in September 2025, preparation for and scrutiny of the Bill was a long process. As noted in a recent SPICe blog on the workload of committees, few bills take longer than a year to scrutinise, so the 18-months between introduction and passing of the Housing (Scotland) Bill was unusual. As a result, the Committee took on many other pieces of work in the intervening period.

This means that in bringing this case study together there has been a strong reliance on the written records of the scrutiny process, including the variety of public documents available, alongside internal evaluation of the lived experience panels. Following and tracking impact in this way is challenging, so it is worth considering that there may be further areas of impact not captured here. To build on a document review, interviews were also conducted with members of the Clerking Team, SPICe and PACT, and one of the Committee members.

The next sections outline the ways that the Lived Experience Panels were referred to throughout the formal evidence sessions, and in the Stage 1 report. This is supplemented, throughout, with insights from these interviews.

Examples of panel outputs informing formal evidence sessions

Throughout the formal evidence sessions Committee members made references to the lived experience panels. There were examples of members asking formal witnesses to directly respond to proposals or claims that the panels had made. For example:

You may be aware that, in the lead-up to the bill, we had a landlords panel and a tenants panel before us, which was very helpful in enabling us to speak to people with lived experience. Our tenants panel proposed an alternative system whereby […] What are your thoughts on that suggestion?

Excerpt from Official Report of meeting on 3 September 2024

This illustrates a specific contribution that the lived experience panels made. It provided a new perspective to support the development of robust bills, and to test new and alternative approaches with witnesses.

In the case above this was with reference to the recommendations from the tenants’ panel. There were similar exchanges that referred to specific claims made by the landlords panel.

The landlords [lived experience panel] pointed towards what they saw as unique circumstances in rural areas, specifically with regards to the Government's island communities impact assessment screening. Is there anything specific within the Bill's proposals that you think is not going to meet the needs of rural and island communities?

Excerpt from Official Report of meeting on 3 September 2024

In this example, the views from the lived experience panel brought the scrutiny process from the abstract and into the consideration of “the actual impact on the ground where it’' carried out” (Committee member). Insights from the experience of rural landlords highlighted specific issues that could then be explored in more detail with witnesses in public sessions.

Examples from the Committee's report

References throughout the Committee's Stage 1 report, setting out the purpose of the panel recommendations “to inform the committees scrutiny of the Bill” (para. 19) and acknowledging that the panel had offered “valuable insights about the housing system from the perspectives of people directly affected by the legislation” (para. 20).

More specifically, the insights from the panels were used to support and add depth to other sources of evidence and points made by formal witnesses. They served as part of the broad evidence mix that was used by Committee members as they scrutinised the Bill and formed the basis of the Stage 1 report. This was illustrated throughout the report in language such as “The Tenants Panel similarly highlighted…” and “this was mirrored in the recommendations of the Landlords’ Housing Panel”.

The report highlighted areas of consensus around the “measures that could be taken to retain properties within the private rented sector” (para. 75) and noted the similarities between some of the recommendations the panels made. Both panels also agreed that time-consuming tribunal processes needed improvement.

Despite these two areas of consensus, and as outlined in the previous section, the recommendations presented by the two panels were, in many ways, diametrically opposed. Given the areas of significant difference, it is difficult to draw a clear line from the recommendations of the lived experience panels to the outcomes in the report and the amendments that have been made by members. As explored in fellowship work by Dr Adam Chalmers on tracing the impact of public engagement, the challenge of understanding and tracing impact is not specific to this case, however the complexity of the Bill and the number of amendments (nearly 700 in total) arguably exacerbate the challenge. Tracing the impact of lived experience based on amendments is also limited, because whilst members are expected to explain the purpose of an amendment when moving it, they do not have to attribute the source of the reasoning behind the amendment.

The examples show that as a source of evidence, the lived experience panels were valuable in the additional and new perspectives that they offered. However, without clear references in the report, or in the statements about specific amendments, it is difficult to make claims about the concrete difference the lived experience panels made to the final Bill.

Lessons to draw from the case study

Matching aims and ambitions to the specifics of the approach taken

The aims and ambitions for the approach was to understand the context and issues faced by individuals and test these against the content of the Bill. However, the approach of having a one-off session with the Committee does not necessarily lend itself to the back and forth that might be required when thinking about testing evidence from different sources against the views and issues raised by the lived experience panels.

There are of course challenges in taking an approach which requires more input from committees which are already stretched for time, both within committee meeting slots and in terms of MSP's individual workload. There is always a trade-off and balance to be struck, and this should be a key part of designing an approach to scrutiny. The findings from a previous SPICe Academic Fellowship with Dr Cara Broadley (Glasgow School of Art) show that co-design across committee support teams has value in offering ways to develop approaches that “align with the needs of parliamentary staff and external stakeholders”.

Careful consideration of the dynamics between different groups offering their Lived Experience to the scrutiny process

The two sets of recommendations were, as highlighted, very different in some significant ways. It is not clear how the differences between the two were managed. In writing the report the clerking team are committed to providing a balance of evidence, leaving decisions of what weight to give different forms and sources of evidence down to the Committee. However, it is important to recognise the power dynamics and differentials between the two groups of people contributing their lived experience to the scrutiny process and to consider the extent to which this needs to be accounted for when considering the recommendations put forward by the different groups.

The fundamental differences between the two sets of recommendations raised questions about the extent to which lived experience can inform and impact Parliamentary scrutiny when it takes this form. The Standards, Procedures and Public Appointments Committee recently published its report on Strengthening Committee Effectiveness, and as part of this recommended that more time be taken at the outset of an inquiry to understand the aims of the committee, how this will be evaluated, and the role of citizen participation and lived experience in the process. Embedding this approach in Session 7 would be an ideal opportunity for Committees and their support staff to consider how inquiries could seek to find lines of consensus between stakeholder groups with opposing views.

Exploring options for deliberative approaches

This case study illustrates challenges of incorporating the direct input of people with lived experience into a politicised and far-reaching issue such as housing. Even if people do not have current experience of renting, it is likely that a significant proportion of the population have experience of renting at some point in time. This is not a niche issue only effecting a small number of people, as is sometimes the case when Parliament invites people with lived experience to give their input. There are a vast array of experience and perspectives from tenants and landlords which was always going to be a challenge to cover in only two, relatively small, panels.

An alternative approach that could be explored for questions that are a) wide ranging and b) have the potential to be politically divisive could be a more deliberative process. Within the two lived experience panels the members were supported to come to a consensus and identify collective recommendations, rather than simply listing individual issues and experiences. However, this deliberation took place within rather than between the two groups. The People's Panels model of deliberation which the Parliament recently agreed to use throughout Session 7 would not necessarily have been an appropriate model here, but it does indicate the commitment that the Scottish Parliament has made to exploring and implementing new ways of working.

Smaller deliberative processes outside of people's panels would be an option, such as those used by the Equality, Civil Justice and Human Rights Committee as part of its approach to Human Rights Budget Scrutiny. In this, a panel with lived experience has had a longer-term relationship with the Committee, and has both produced questions for the Committee to put directly to the Scottish Government, and collaboratively explored issues with the Committee. In the latter, policy was explored from the perspective of the Scottish Government's requirements to meet minimum core human rights responsibilities, a framework which could provide a useful basis for scrutiny of challenging or divisive topics.

The evaluation of two People's Panels held in 2024 notes that "the Parliament has built an in-house capacity to experiment, iterate, and respond to the specific needs of each panel" (Inaki Goni and Elisabet Vives, University of Edinburgh). If the input of people with lived experience is to be engaged with meaningfully, this same level of capacity should be resourced to allow the Parliamentary service to reflect on and respond to the asks from committees for lived experience involvement and to ensure that approaches are designed and evaluated effectively.