Sport in Scotland: An Overview of Legislation, Governance, Policy and Funding

The Scottish sporting landscape is complex, with various organisations responsible for governance and funding. This briefing intends to outline the key stakeholders at a national, local and international level, and their roles in governing and funding Scottish sport. A number of key issues present in Scottish sport are highlighted, including participation trends, addressing inequalities and the state of facilities.

Summary

Background

The complex nature of the Scottish sporting landscape was highlighted in Professor Grant Jarvie's 2019 report – A Review of the Scottish Sporting Landscape.1

This briefing intends to provide an overview of this landscape, discussing the legislative and policy context, responsibilities of key stakeholders, funding sources, and some of the key issues Scottish sport is facing.

Legislative Context

The Local Government and Planning (Scotland) Act 1982 sets out the obligation of the the district and local councils to ensure adequate provision of facilities for recreational and sporting activities.

Under the Local Government etc. (Scotland) Act 1994 this statutory duty was transferred to the new local authorities.

The National Lottery etc. Act 1993 outlines directions that sportscotland must adhere to when distributing and investing National Lottery funding.

An Overview of Governance

Various organisations are responsible for sports governance, planning and delivery at the national, local and international level.

Sportscotland is the national sports agency, and with the Scottish Government, has a large role in shaping the direction of Scottish sport. Both are accountable to the Scottish Parliament.

Policy Context

The Scottish Government's Physical Activity Delivery Plan – A More Active Scotland – outlines their vision of a Scotland where people are more active more often. This delivery plan is currently under revision.

The Active Scotland Outcomes Framework sets out the goals which will help the Scottish Government to achieve this vision.

Sport for Life (2019-2029) is sportscotland's strategy which outlines its vision of an active Scotland where everyone benefits from sport.

The Minister for Social Care, Mental Wellbeing and Sport issues sportscotland with a Strategic Guidance Letter, which sets out the policy framework and priorities that sportscotland should build towards in the current parliamentary term.

Funding

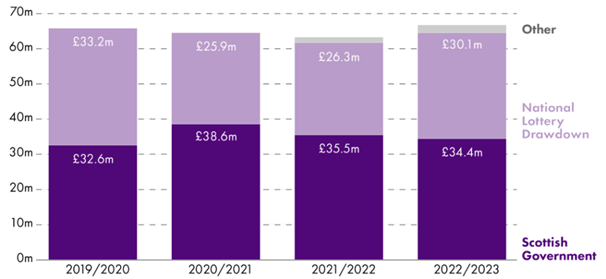

Scottish sport is primarily funded by grant in aid and general fund for sport from the Scottish Government, and National Lottery funding.

Scottish Government funding is provided to sportscotland for spending and distribution, and local authorities, who are estimated to be responsible for up to 90% of the public funding invested.1

As a National Lottery fund distributor, sportscotland is responsible for investing all of the funds received from the National Lottery.

Performance sport is funded by the UK Government through UK Sport. There are also instances where the UK Government provides direct funding to Scottish sport, such as funds provided as part of the UK Government's Levelling Up Agenda, including through the Multi-Sports Grassroots Facilities Programme.

Glossary

Below is a list of abbreviations used throughout this briefing.

| AIOWF | Association of International Olympic Winter Sports Federations |

| ALEO | Arms-length external organisation |

| ARISF | Association of International Olympic Committee Recognised International Sports Federations |

| ASOIF | Association of Summer Olympic International Federations |

| BOA | British Olympic Association |

| BPA | British Paralympic Association |

| BUCS | British Universities and Colleges Sport |

| CGS | Commonwealth Games Scotland |

| COSLA | Convention of Scottish Local Authorities |

| CPG | Cross-party group |

| CSH | Community sports hub |

| DCMS | Department of Culture, Media and Sport |

| DFLE | Disease free life expectancy |

| EOC | European Olympic Committees |

| FIFA | Fédération de internationale de football association |

| HLE | Healthy life expectancy |

| IF | International Sports Federation |

| IOSDs | International Organisations of Sports for the Disabled |

| IOC | International Olympic Committee |

| IPC | International Paralympic Committee |

| LE | Life expectancy |

| MSP | Member of the Scottish Parliament |

| MVPA | Moderate or vigorous physical activity |

| NDPB | Non-departmental public body |

| NLDF | National Lottery Distribution Fund |

| NOC | National Olympic Committee |

| NPC | National Paralympic Committee |

| POCA | Proceeds of Crime Act |

| SCQF | Scottish Credit and Qualification Framework |

| SFA | Scottish Football Association |

| SGB | Scottish governing body of sport |

| SHS | Scottish Household Survey |

| SHeS | Scottish Health Survey |

| SIMD | Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation |

| SPFL | Scottish Professional Football League |

| SSA | Scottish Sports Association |

| SSS | Scottish Student Sport |

| TSFA | The Scottish Football Alliance |

| UEFA | Union of European Football Associations |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

Background

Shaping the direction of sport in Scotland is a power devolved to the Scottish Parliament and administered by the Scottish Government.

The structure of the Scottish sporting landscape is complex, and includes various organisations that are responsible for planning, delivery, funding and governance of sport and physical activity at national and local levels.

The complexity of the landscape has previously been highlighted in The Jarvie Report 20191, which outlined that the sector would benefit from a comprehensive organisational map outlining the remits of all stakeholders.

Briefing Scope

This briefing sets out the key issues surrounding the Scottish sporting landscape, including the legislative and policy context that is presently shaping the direction of Scottish sport, and the avenues of funding for sport and physical activity.

An overview of governance of sport at a national and local level is provided, including the remits of key organisations. A handful of the wider issues relating to sport and physical activity in Scotland are discussed, including participation trends, addressing inequalities and the state of facilities.

Defining Sport and Physical Activity

In the past few years, the line between the definitions of sport and physical activity has become blurred, as literature has begun to place physical activity under the umbrella of sport. However, despite their similarities, each have distinct definitions.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines “physical activity” as:

[…] any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure.

World Health Organization. (2022, October 5). Physical activity. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity

On the other hand, sport incorporates physical activity with skills, to provide a contest between individual or teams, often for the entertainment of spectators.

Prof Grant Jarvie's 'A Review of the Scottish Sporting Landscape' highlights how the line between sport and physical activity has recently become more blurred.2 Jarvie's review uses the term sport and intends it to be inclusive of physical activity, adopting the United Nations working definition of sport, where sport refers to:

All forms of physical activity that contribute to physical fitness, mental well-being and social interaction, such as play, recreation, organised or competitive sport, and indigenous sports and games.

Commwealth Secretariat. (2015). Sport for Development and Peace and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Retrieved from https://production-new-commonwealth-files.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/migrated/inline/CW_SDP_2030%2BAgenda.pdf

However, this briefing will not take this approach. Where the distinct differences between sport and physical activity are pertinent, the terms sport and physical activity will be used where appropriate, according to the respective definitions provided above.

Community sport and elite sport will also be mentioned in this briefing. Community sport is defined as:

[Activities that] are low threshold and financially accessible, and organised locally, in specific – often urban – neighbourhoods. The activities are not usually high level or competitive in nature.

Van der Veken, K., Lauwerier, E., & Willems, S. (2020). How community sport programs may improve the health of vulnerable population groups: a program theory. International Journal for Equity in Health, 19(1). doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-020-01177-5

Meanwhile, elite sport is not consistently defined, but has been deemed to concern professional status, sustained high-level performance, and competitive, national and varsity team members. 5This briefing will consider elite sport to be inclusive of teams and individuals that compete professionally at youth and adult level.

Legislative Context

There is little legislation that directly relates to sport in Scotland, however the Local Government and Planning (Scotland) Act 1982, has key provisions that impact sport-related matters.

Section 14(1) of this Act sets out the obligation of the then district and island councils to provide adequate services. It states:

a local authority shall ensure there is adequate provision of facilities for the inhabitants of their area for recreational, sporting, cultural and social activities.

Since then, under Schedule 13 of the Local Government etc. (Scotland) Act 1994, this statutory duty was transferred to the new local authorities.

The term “adequate” was not defined in the Act, and has not subsequently been defined.1 Previous guidance produced by the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities (COSLA) and the (then) Scottish Executive, provided recommendations on the development and implementation of services. This guidance has since been archived and has not been updated.i

Section 15(2) of this Act sets out the powers of local authorities to provide facilities and activities. It states:

a local authority may provide or do, or arrange for the provision of or doing of, or contribute towards the expenses of providing or doing, anything necessary or expedient for the purpose of ensuring that there are available, whether inside or outside their area, such facilities for recreational, sporting, cultural or social activities as they consider appropriate.

Under the National Lottery etc. Act 1993, sportscotland, the national agency for sport in Scotland, was appointed to distribute funding received from the National Lottery for Scottish sport. Section 26 of the Act outlines directions to distributing bodies, such as sportscotland, of National Lottery funds.

Whilst not legislation, the following documents underpin sportscotland's objectives, responsibilities and priorities, as the national sporting agency for Scotland:

The Royal Charter of the Scottish Sports Council sets out sportscotland's core objectives.

Sportscotland's non-departmental public body (NDPB) Framework document sets out the broad framework within which sportscotland will operate and defines roles and responsibilities which underpin its relationship with the Scottish Government.

The Ministerial Strategic Guidance Letter sets out the Scottish Government's expectations of sportscotland and its strategic priorities over a given term.

An Overview of Governance

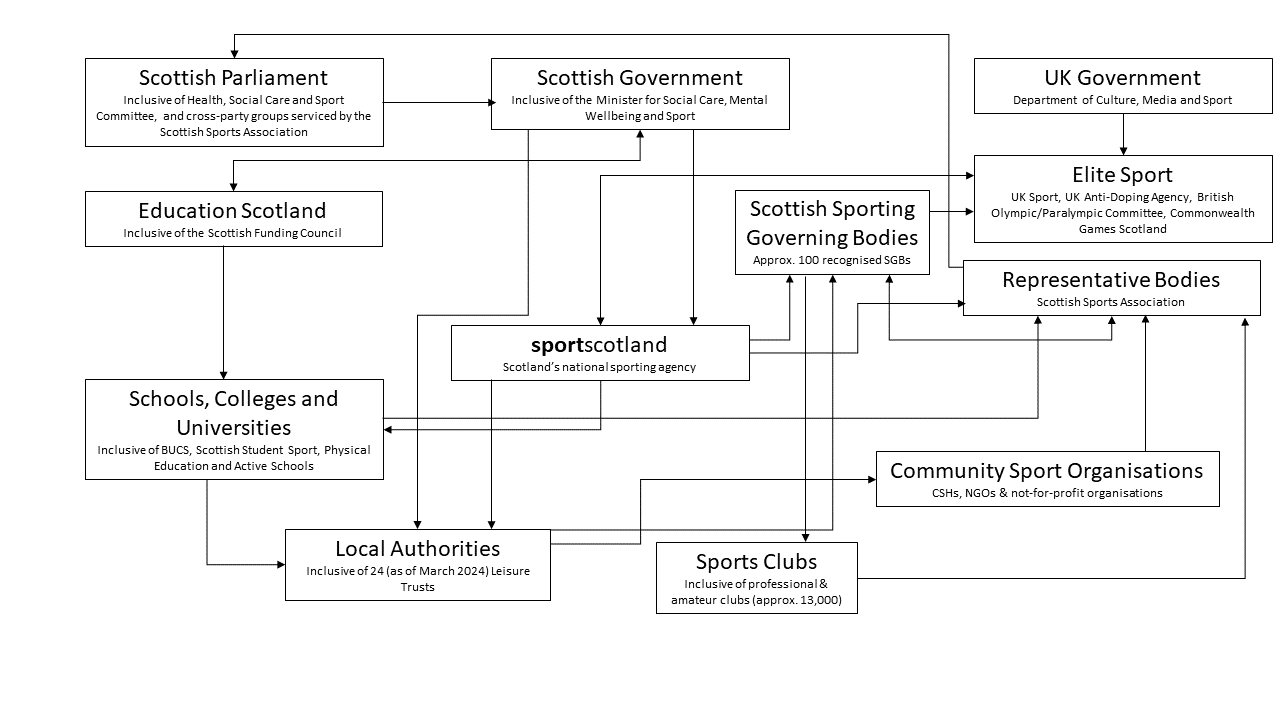

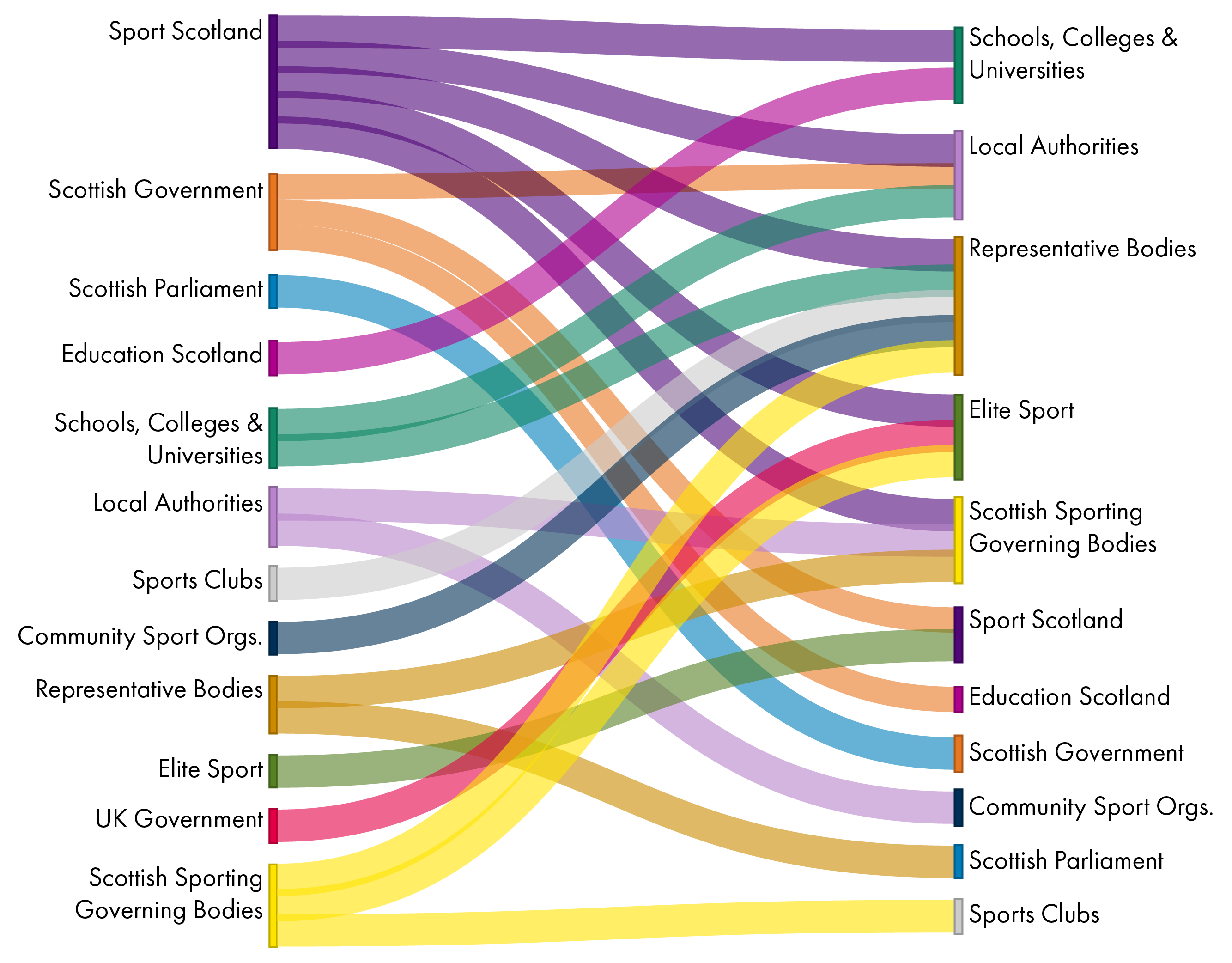

Various government and non-government bodies have roles surrounding sports governance, planning and delivery. These organisations and their roles at local, national and even continental levels are discussed below. Appendix 1 and Appendix 2 provide an overview of the key organisations at a national and local level, and the relationships between them.

National Level

Scottish Parliament

The Scottish Parliament examines and scrutinises the work of the Scottish Government, holds debates on pertinent issues and has the authority to make new laws in devolved areas.

There are various groups within the Scottish Parliament with responsibilities that concern sport and through their discussions and decisions, these groups scrutinise and shape the development of sport policies and strategies.

Health Social Care and Sport Committee

The Scottish Parliament's Health, Social Care and Sport Committee is a small group of Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) that holds the Scottish Government to account on matters within its remit, undertakes inquiries and examines and proposes amendments to legislation. For example, in relation to sport, recently the Committee conducted an inquiry into female participation in sport and physical activity and took evidence from the Scottish Football Association's (SFA) CEO, Stewart Maxwell on issues including governance, accountability, child wellbeing and protection, and fan representation.

Cross-Party Groups

Scottish Parliament cross-party groups (CPGs) are groups of MSPs with a keen interest in a subject or issue that must meet at least twice every year. The CPG on Sport, serviced by the Scottish Sports Association (SSA), supports the development of Scottish sport, raises the profile of sport and physical activity in Parliament, influences Scottish Government policy and liaises with sport organisations, including sportscotland.

Other CPGs with an interest in sport-related matters include:

Scottish and UK Government

Scottish Government

The Scottish Government is responsible for promoting and developing sport and physical activity in Scotland and will develop and implement policies to support this function. Additional roles include to provide funding and support to initiatives, local authorities and organisations, including sportscotland.

A Minister for Social Care, Mental Wellbeing and Sport, currently Maree Todd MSP, is appointed to oversee the direction of sport and physical activity.

The Minister's roles include; to spearhead national policy and strategy, promote the importance of sport, coordinate inter-departmental agendas with other government departments, such as education, and act as the funding agent.

UK Government and UK-Wide Organisations

UK Government

The UK Government's Department of Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) champions sport across the UK at all levels. In Scotland, the DCMS has a more concentrated interest in elite sport, through the UK Government's arms-length NDPBs – UK Sport and the UK Anti-Doping Agency.

UK Sport

UK Sport, as the agency for high-performance sports funded by the UK Government and the National Lottery, has various responsibilities. These include providing financial investment for Olympic and Paralympic sport, planning and hosting major sporting events and collaborating and building relationships with international sporting bodies.

UK Anti-Doping Agency

The UK Anti-Doping Agency is the UK's body fighting against doping in sport, ensuring that Scottish governing bodies of sport (SGBs) and sports clubs comply with the World Anti-Doping Code by implementing and managing the UK National Anti-Doping Policy.

British Olympic Association & British Paralympic Association

The British Olympic Association (BOA) is the UK's National Olympic Committee (NOC), and with the national governing bodies of sports and national sports agencies – including sportscotland – they organise and oversee participation of Team GB athletes at summer, winter and youth Olympic Games.

The BOA is independent from the UK Government, receiving no Government or National Lottery funding, instead raising funds through fundraising and events.

The BOA also serves UK sport by developing, promoting and protecting the Olympic Movement in accordance with the Olympic Charter and Olympic Values, and by developing high performance sport, whilst championing sport for all.

Similar to the BOA, the British Paralympic Association (BPA) is the National Paralympic Committee (NPC) for Great Britain. The BPA is responsible for selecting, entering, funding and managing ParalympicsGB, the Great Britain and Northern Ireland team at the Paralympic Games.

Commonwealth Games Scotland

Commonwealth Games Scotland (CGS) is the lead body for Commonwealth sport in Scotland. Its membership is comprised of the SGBs of the 28 recognised Commonwealth Games sports.

Its vision is for the Commonwealth Games and Team Scotland to inspire Scotland to be physically active and successful in the sporting arena by enabling Team Scotland athletes to perform to their potential at Commonwealth Games and Commonwealth Youth Games.

The CGS Strategic Plan (2020-2027) outlines six strategic goals and corresponding actions and success measures. These goals are:

Successful teams,

Effective organisation,

Integrated partnerships,

Secure financial base,

Achievements recognised and celebrated,

Actions underpinned by evidence.

Sportscotland

Established by Royal Charter in 1972, sportscotland, formerly The Scottish Sports Council, is Scotland's national sports council and a NDPB responsible to the Scottish Parliament through Scottish Ministers.

Inclusive of sportscotland Institute of Sport, National Centres, National Para Sports Centre, and Team Scotland, sportscotland operates to achieve the vision of an active Scotland where everyone benefits from sport.

As the national agency for sport our role is to make sure sport plays its part in a thriving Scotland. We do this by influencing, informing and investing in the organisations and people who deliver sport and physical activity.

Sportscotland. (2023, March 6). What we do. Retrieved from https://sportscotland.org.uk/about-us/what-we-do

NDPBs operate on behalf of, but with some degree of operational autonomy from, the Scottish Government.

Sportscotland's aims and objectives are defined with the Scottish Government, outlined in the sportscotland NDPB Framework, which are aligned with the National Performance Framework, Scotland's Economic Strategy, Programme for Government and the Active Scotland Outcomes Framework.

Sportscotland's core objectives, as set out in its Royal Charter, are:

Fostering, supporting, and encouraging the development of sport and physical recreation among the public at large in Scotland.

The achievement of excellence in sport and physical recreation.

The provision of facilities for the objectives set out above.

Sportscotland's roles and responsibilities include to:

Develop strategies to support and encourage sport participation in schools and communities.

Allocate funding to sports organisations, clubs and initiatives, to develop and implement programmes, support infrastructure and advance elite athlete performance.

Oversee the training of coaches and volunteers in sport through offering programmes and resources to support development.

Provide support to, and collaborate with, sport governing bodies, local authorities, schools and community organisations.

Conduct research and gather insight into participation trends, the impact of ongoing programmes and the needs of communities.

Scottish Governing Bodies of Sport & the Scottish Sports Association

Scottish governing bodies of sport (SGBs) are independent organisations that are responsible for the governance, development and delivery of the individual sports they represent.

SGBs are not appointed by sportscotland, rather they are recognised as being an organisation that governs and administers a sport at a national level.

There are approximately 100 recognised SGBs and sporting national partners in Scotland, 47 of which currently receive investment from sportscotland, including Cricket Scotland, Scottish Cycling, and the SFA. A full breakdown of recognised sports and national governing bodies is available on the sportscotland website.

Sportscotland works directly with SGBs that they invest in to ensure they are fit for purpose, and efficiently and effectively utilise the resources at their disposal.

The SGB Governance Framework and its twelve principles of good governance provides guidance to SGBs, complemented by other Generic Support provided by sportscotland.

The Scottish Sports Association (SSA) is an umbrella organisation representing the majority of SGBs. It has a working relationship with sportscotland, national and local government and other key organisations. The SSA provides support and a voice for its full and associate member organisations.

The nature of the support includes:

Sharing best practice and facilitating networking opportunities across organisations.

Providing relevant information on developments within the sporting world and offering a dedicated team to answer questions and find solutions.

Presenting the unified and representative voice of SGBs.

Informing and influencing the Scottish Government's sport-related agendas.

The SSA publishes annual reviews which provide information relating to their activities and achievements in the previous year.

National Education Organisations

Education Scotland

Education Scotland is a Scottish Government executive agency, accountable to both the Scottish Government and Scottish Parliament, that provides advice on education matters. In relation to physical education, physical activity and sport within schools, they are responsible for:

Improving and supporting quality education.

Supporting the professional development of educators.

Delivering better experiences and outcomes for learners.

British Universities & College Sport

British Universities and Colleges Sport (BUCS) is the national governing body for sports higher education. The BUCS 2023-2027 Strategy outlines its aim to:

deliver exceptional sporting experiences that inspire, develop and unite.

British Universities and Colleges Sport. (2023, July 13). BUCS Strategy 2023-2027. Retrieved from https://www.bucs.org.uk/resources-page/welcome-to-the-new-bucs-strategy.html

This strategy also outlines its values - inclusive, innovative, respectful and dynamic - and strategic themes that will help them to achieve this overarching ambition by 2027.

Scottish Student Sport

Scottish Student Sport (SSS) is an organisation that has partnerships with sportscotland, BUCS, SGBs and the Scottish Funding Council to help them deliver their objectives.

SSS is comprised of students and staff from colleges and universities across Scotland, advocating for active health and sport across higher education with the aim that Scotland can harness the powers of sport to benefit students, institutions and communities.

Its objectives, high-level income and expenditure and the values which underpin its work are outlined in their strategic document – Strategy 21+.

Universities, Colleges and the School Estate

The education system – inclusive of the school estate, universities and colleges of higher/further education – comprises a significant proportion of the Scottish sporting structure.

The Scottish Government is committed to the physical education weekly guidelines for primary (two hours) and secondary (two periods) pupils, outlined on the Scottish Government website, and schools are responsible for ensuring adherence to this.

The 2023 School Healthy Living Survey highlights that 99% of schools – over 99% and 95% of primary and secondary schools, respectively – met the target level in 2023.2

Universities and colleges offer a variety of sports opportunities from organised training and competitive sport, delivered through BUCS and relevant SGBs, and recreational sporting sessions, such as the University of Stirling's ‘Just Play Sport’ programme.

The 2018 ‘Evaluation of sportscotland supported activity: schools and education’ report highlights the various ways sportscotland supports sport and physical activity in the school environment. These include the Active Schools and Active Girls programmes, the School Sport Award, Young Ambassadors programme, among other avenues of support.3

Local Level

Local Authorities

Scotland's 32 local authority areas have a statutory obligation to ensure the provision of adequate services and facilities for sport, physical activity, and leisure. This is outlined in the Local Government and Planning (Scotland) Act 1982. Local authorities are expected to assess local need and account for national objectives when allocating funds, developing strategies, and implementing initiatives.

The remit of local authorities extends to managing community-based (leisure centres, swimming pools, playing fields) and school-based facilities, which make up the majority of Scottish sports facilities.

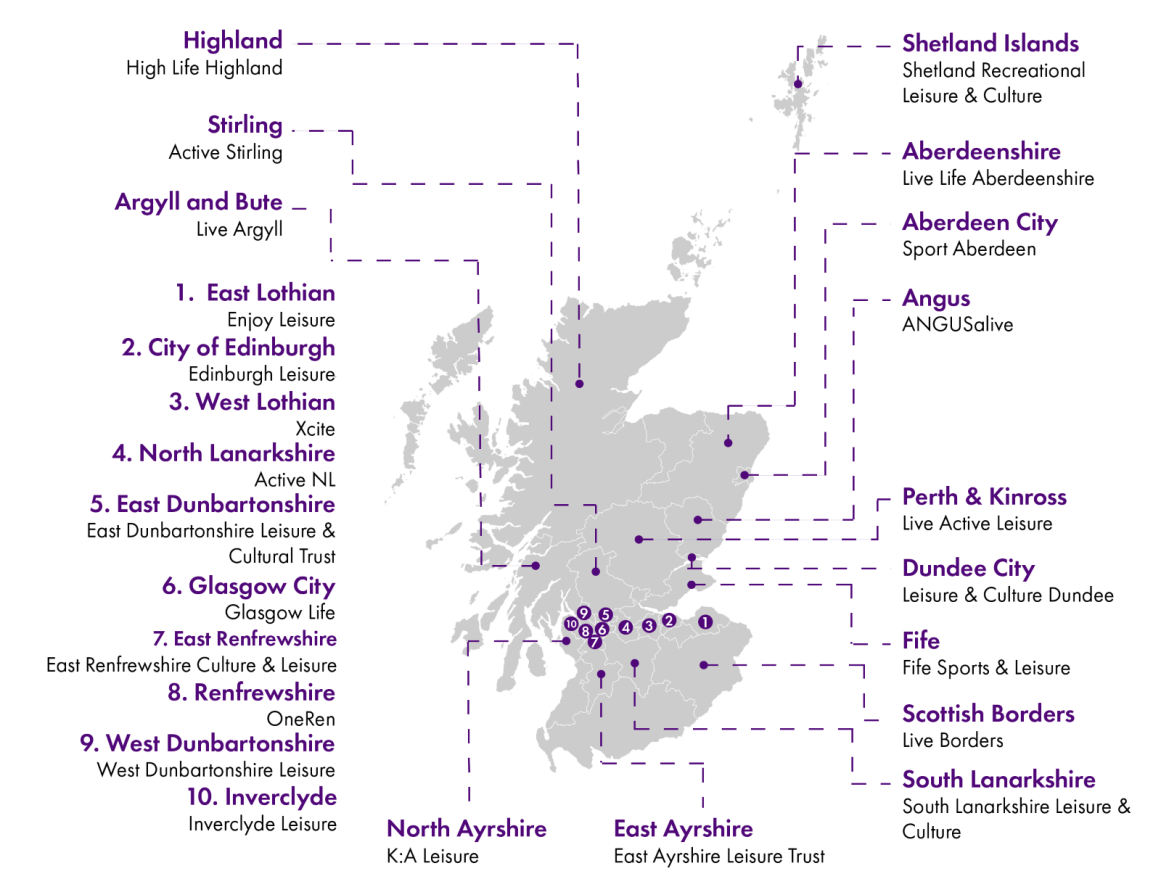

Local authorities are permitted to contract not-for-profit arm's-length external organisations (ALEOs) to work independently to deliver the service on behalf of the local authority.

Audit Scotland produced a report on the emergence of ALEOs in local authorities in 2011, highlighting some key observations1.

The key drivers for local authorities contracting ALEOs are to reduce costs and improve service delivery.

The council maintains a degree of control over ALEOs, typically through a funding agreement, however they have a separate identity, so governance and financial arrangements can be complex.

The local authority remains accountable for the funds they provide to ALEOs and must be able to “follow the public pound” to the point it is spent.

In the decade preceding this report, the number of local authorities contracting ALEOs to deliver leisure services had doubled.

As of April 2024, 24 local authorities currently contract ALEOs, or “leisure trusts”, to deliver sport and leisure services. Appendix 3 lists the local authorities and the leisure trusts they contract.

Sports Clubs and Community Sports Hubs

Sports Clubs

Sports clubs are typically voluntary organisations supported by the relevant SGB and local authority within which they operate. There are approximately 13,000 sports clubs across Scotland1, which tend to rely on membership fees to support their operation, however some receive investment from successful National Lottery and local authority grant bids.

Professional sports clubs, such as the 42 that compete in the Scottish Professional Football League (SPFL) are involved in community work – strengthening their communities and improving people's wellbeing – through charitable trusts or foundations.

The SPFL Trust is responsible for coordinating this work, including the Football Fans in Training programme which receives financial backing from the Scottish Government.

Community Sports Hubs

The Community Sport Hub (CSH) programme, funded through the National Lottery, is one of sportscotland's key initiatives to promote inclusivity in the Scottish sporting system.

A CSH brings together, and enables collaboration between, sports clubs and other community-based organisations to improve the impact that sport and physical activity has on communities.

A network of CSH officers operate across Scotland to facilitate the development of initiatives to overcome relevant barriers. However, an important aspect of the programme is that local people feel empowered and supported to improve sport and physical activity in their own community.

An interactive map of the operational bases of CSHs across Scotland is available on the sportscotland website.

International Level

In some avenues of elite sport, organisations are responsible for overseeing sports governance at an international level. The remit of such organisations is often to oversee and inform the actions of national organisations for given sports. A brief overview of the various organisations is provided below.

International Olympic Committee

Sitting at the heart of world sport, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) supports Olympic Movement stakeholders, promotes Olympismi and oversees the regular celebration of the Olympic Games.

The IOC facilitates collaboration between all the Olympic stakeholders including NOCs, International Federations, organising committees, worldwide partners and media rights-holders. Their vision is to "Build a Better World through Sport", with their values – excellence, respect and friendship – central to their activities.2

The IOC has a number of responsibilities including to encourage and support the organisation, development of sport and sports competitions, including the summer and winter Olympic Games. The full list of their roles is available on the IOC website.

The IOC is a non-profit, non-governmental organisation that is entirely privately funded, relying on contributions from their commercial partners. 90% of their revenue is redistributed to the Olympic Movement whilst the remaining 10% supports the IOC's activities to develop sport and their operations.3

Further information on the contributions the IOC has made to staging the summer, winter and youth Olympic Games, International Sports Federations (IFs), NOCs, and other investment is available on the IOC website.

Annual reports dating back to 2014 are available on the IOC website. The latest report – Annual Report 2022: Solidarity and Peace – details their activities across 2022 building towards their strategic roadmap (Olympic Agenda 2020+5), a review of governance and financial statements.

European Olympic Committees

The European Olympic Committees (EOC) is the umbrella organisation that represents Europe's 50 NOCs. The EOC aims to raise the profile of Olympic sport, spread the Olympic values, inspire participation in sport and physical activity and support the activities of NOCs. The EOC also supports various grassroot activities and elite sporting events, including the European Games, European Youth Olympic Festival and the Games of the Small States of Europe, and will support athletes and coaches in their pursuit of success at these competitions.

The EOC's Strategic Agenda 2030 outlines their roadmap and six key strategic priorities to shape the direction of European sport from 2022-2030. This agenda is closely aligned with the IOC's recommendations and priorities set out in their own strategic agenda – Olympic Agenda 2020+5.

International Paralympic Committee

The International Paralympic Committee (IPC) is an international non-profit organisation that develops Para sport,i ensures the delivery and organisation of the Paralympic Games and acts as the international federation for six Para sports.ii The IPC provides support to its approximately 200 members which include NPCs, International Sports Federations (IFs), regional organisations and International Organisations of Sports for the Disabled (IOSDs).

The IPC's Strategic Plan (2023-2026) outlines their vision – “To make for an inclusive world through Para sport” – and the strategic goals that will ensure the realisation of this vision.

Annual reports dating back to 2004 are available on the IPC website. The latest report – Annual Report 2022 – provides information on the IPC structure, membership, financial statements and key actions across 2022.

International Sports Federations

International Sports Federations (IFs) are responsible for overseeing and ensuring the integrity of the sport they represent at the international level, as well as establishing and enforcing the rules that govern their sport.

Scottish athletes and athletes based in Scotland often participate in competitions organised by these IFs.

IFs are a key component of the Olympic and Paralympic Movements, and for a sport to be included in the Olympic or Paralympic Games, the respective IF must be recognised by the IOC or IPC.

The majority of IFs are recognised by the IOC, grouped under the umbrella of three associations. These are the:

Association of Summer Olympic International Federations (ASOIF).

Association of International Olympic Winter Sports Federations (AIOWF).

Association of IOC Recognized International Sports Federations (ARISF).

Sports that are within the Paralympic Movement are governed either by the IPC, serving as the IF for six sports, by an IF that falls under the Olympic Movement, or an independent IF that governs a particular sport for athletes with a disability. The IPC also recognises a number of IFs that are not part of the Paralympic Games but that are Code signatories. There are also a number of IFs that are not formally recognised by the Olympic and Paralympic signatories but are Code signatories.

IFs will typically have their own website where further information can be found on their governance structure, strategic priorities and financial statements. For example, the Fédération internationale de football association (FIFA) as the IF for football have published their ‘Strategic Objectives for the Global Game: 2023-2027’ and Annual Report for 2023 on the FIFA Website.

Across Europe, there are a number of European Sports Federations that oversee and coordinate elite competitions and development programmes. For example, the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA), as the governing body of European football, is an association of the 55 national football associations across Europe.

Policy Context

Developing and implementing policy surrounding sport and physical activity in Scotland is a power devolved to the Scottish Parliament and administered by the Scottish Government.

Over the last two decades, various strategic policies have shaped the direction and development of sport in Scotland. As the national agency for sport in Scotland, sportscotland, along with local authorities, is responsible for contributing to delivering on the Scottish Government's objectives, by aligning their activities with government policies.

Scottish Government - A More Active Scotland

Scotland's Physical Activity Delivery Plan – A More Active Scotland – outlines the vision of:

A Scotland where more people are more active, more often.

Scottish Government. (2018, July 12). A More Active Scotland: Scotland's Physical Activity Delivery Plan. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/strategy-plan/2018/07/active-scotland-delivery-plan/documents/00537494-pdf/00537494-pdf/govscot%3Adocument/00537494.pdf

The Delivery Plan's overarching aims are to reduce physical inactivity in adults and teenagers by 15% by 2030, address barriers to participation and existing inequalities in access to opportunities, and encourage lifelong participation in sport and physical activity among children and young people.13

The principles of the plan, informed by the WHO Global Action Plan on Physical Activity and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, are embedded within the work of the Scottish Government, and will help to realise the transformative impact that physical activity and sport can have on people's lives.

The Active Scotland Delivery Group was established in 2018 to:

Monitor the delivery of the actions in the Delivery Plan.

Identify opportunities to enhance delivery through partnership working.

Consider recommendations from the Active Scotland Development Group on new or revised delivery actions or approaches.

The Delivery Plan is currently under revision within the Scottish Government, with specific areas of collaborative action based on Public Health Scotland's whole systems analysis. There will be a clear focus on addressing inequalities, which will underpin the actions undertaken.i

Active Scotland Outcomes Framework

The Active Scotland Outcomes Framework sets out the shared goals which the Scottish Government and their partner organisations (including sportscotland, Education Scotland and NHS Education Scotland) have outlined to achieve their vision, and support and enable people to be more physically active.

The outcomes are:

We encourage and enable the inactive to be more active.

We encourage and enable the active to stay active throughout life.

We develop physical confidence and competence from the earliest age.

We improve our infrastructure – people and places.

We support wellbeing and resilience in communities through physical activity and sport.

We improve opportunities to participate, progress and achieve in sport.

A number of policies, initiatives and campaigns have helped the Scottish Government to work towards these outcomes, including the Active Schools programme and the National Walking Strategy.

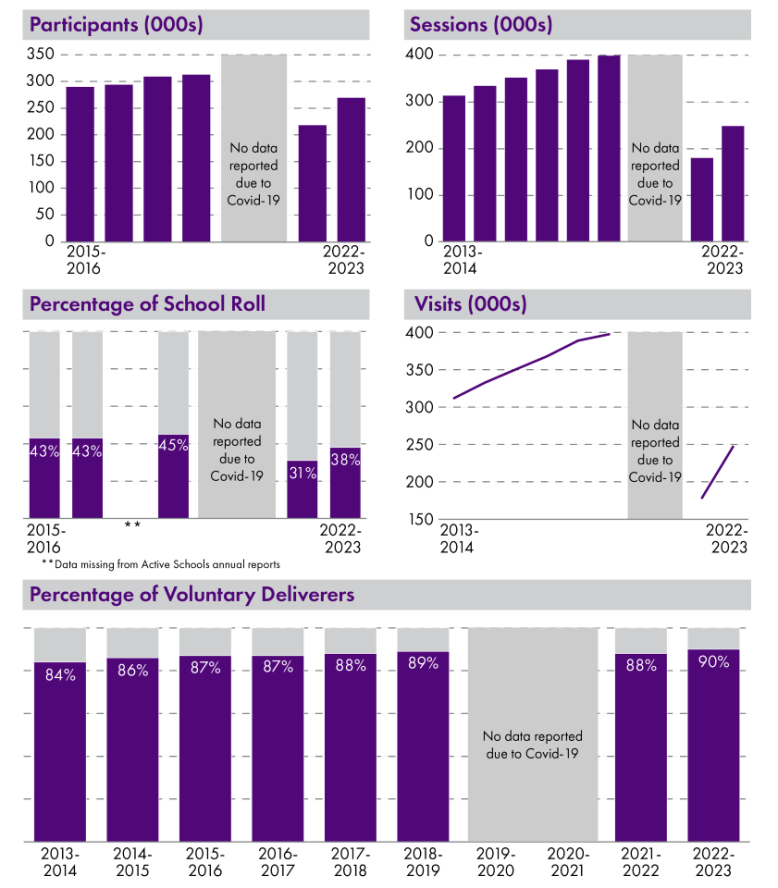

Active Schools

The Active Schools programme, first introduced in 1996, is implemented in schools across all 32 local authorities and is driven by two primary objectives. These are to promote more high-quality opportunities to participate in sport and physical activity within schools, and to facilitate a pathway for longer-term sport participation through partnerships with clubs and community organisations.

Sportscotland provides investment and support to local authorities and the Active Schools network, which includes over 400 managers and coordinators. The importance of the programme, and sportscotland's role, is highlighted in its inclusion within the Minister's Strategic Guidance Letter for 2023-2026 where one of the priorities is to:

Ensure that the Active Schools programme is free for all children and young people by the end of this Parliament.

Active Schools annual reports dating back to the 2013/14 academic year, excluding 2019/20 and 2020/21 due to the Covid-19 pandemic, are available on the sportscotland website. The most recent report, ‘Active Schools Report: 2022-2023’, highlights the current reach of the programme across Scotland and within each local authority. Key points include:

Over 269,000 children and young people attended Active Schools activities throughout the 2022/23 academic year, accounting for 38% of the school roll.

Almost 18,000 people, 90% of which were volunteers delivered almost 247,000 Active Schools sessions.

Appendix 4 provides an overview of the reach of the Active Schools programme across Scotland dating back to 2013/14, including the number of sessions delivered and the number of distinct participants who attended these sessions.

In their report on their inquiry into female participation in sport and physical activity, the Scottish Parliament's Health, Social Care and Sport Committee called on the Scottish Government to commission an evaluation of the Active Schools programme.

The last evaluations were published in 2014 and 2018, however the Committee believed an updated evaluation is necessary, with a particular focus on female participation.

This view was echoed in the Parliamentary Debate on Female Participation in Sport and Physical Activity following the inquiry.

Several MSPs noted the positive impacts this programme has had on broadening girls’ access to a wider range of sports and physical activities yet highlighted the need for an update evaluation.

Let's Get Scotland Walking

Scotland's national walking strategy – Let's Get Scotland Walking – introduced in 2014, outlines the Scottish Government's vision for a Scotland where everyone benefits from walking. The Action Plan 2016-2026, revised in March 2019, was developed to assist in the delivery of the national walking strategy and its vision.

This multi-faceted strategy sits within the context of the Active Scotland Outcomes Framework and the Long-Term Vision for Active Travel in Scotland, amongst others.

The key principles underpinning the vision of the strategy include to address issues surrounding access, availability, and quality of walking spaces, and adaptability to suit changing community needs.

The Action Plan 2016-2026 sets out the various outcomes and the actions that will be taken by relevant delivery leads to achieve these outcomes.

The Daily Mile is one initiative that has been incorporated which has shown benefits such as, increased levels of physical activity and physical fitness, improved body composition and reduced sedentary time.1

Sportscotland - Sport for Life

Scotland's national sport strategy (2019-2029), Sport for Life, was launched by sportscotland in May 2019. As its corporate strategy, this outlines sportscotland's vision of – “an active Scotland where everyone benefits from sport”.

The six key principles guiding sportscotland to deliver the benefit of sport to all of Scotland are:

Inclusive, accountable, responsive, person-centred, collaborative and world class.

The Business Plan (2023-) is driven by Sport for Life and the Strategic Guidance Letter for 2023-2026 that the Minister for Social Care, Mental Wellbeing and Sport, Maree Todd MSP, issues to sportscotland. This letter sets out the strategic policy framework and various priorities that sportscotland should build towards in the current parliamentary term.

Priorities for this parliamentary term include to:

Focus on reducing inequalities in sport and physical activity, by addressing racial inequality, cost barriers and female participation.

Provide accessible and inclusive opportunities for sport and physical activity in the school and education environment.

Support sports clubs and community organisations in the provision of inclusive sport and physical activity organisations.

Place inclusion and welfare at the heart of high-performance sport environment that prepares and supports athletes to deliver success on the world stage.

Provide leadership to develop and sustain strategic partnerships that will help the Scottish Government and sportscotland on their joint vision.

The sporting system that will encourage the key environments – clubs and communities, schools and education, and performance sport – to collaborate and allow all of Scotland to benefit from the system is depicted in Figure 2.

Funding

Sport in Scotland is primarily funded through three avenues:

Grant in Aid from the Scottish Government

General fund for sport from the Scottish Government

National Lottery funding

The majority of Scottish Government funding is allocated to sportscotland for spending and distribution within the sector. The Scottish Government provides further funding to the 32 local authorities, who allocate funds to sport through their own investment into parks, open spaces, sports facilities, and swimming pools.

This investment allows the local authorities to deliver on their statutory obligations to ensure adequate provision of facilities for sporting activities within their area.

As a National Lottery fund distributor, sportscotland is responsible for investing all of the funds received from the National Lottery.

Further income is generated by sportscotland via its two national centres – the national outdoor training centre at Glenmore Lodge, and the national training centre in Inverclyde. The primary purpose of these national training centres is for the development of instructors, coaches, leaders, and national squads, however sportscotland also offer courses for individuals, clubs and schools which generate further income. Historically, there were three national centres, however the national water-sports centre in Cumbrae officially closed in September 2020.

Scottish Government Funding

Each year, the Scottish Government sends sportscotland correspondence detailing their budgetary provision for the upcoming financial year, in light of decisions taken by the Scottish Ministers on budget allocation.

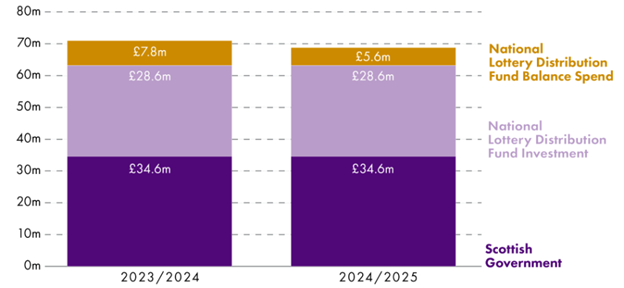

This funding is provided to sportscotland to support the development of Scottish sport and to help them deliver on the outcomes outlined in the Active Scotland framework. In 2023/2024 the Scottish Government provided sportscotland with £34.7 million.

These resources must be used in accordance with the ministerial priorities outlined in the strategic guidance letter (2023-2026), sportscotland's corporate strategy (Sport for Life), sportscotland's business plan (2023-), and relevant guidance such as the Scottish Public Finance Manual.

Local authorities, considered the major financial investors in sport and physical activity across Scotland, are estimated to be responsible for up to 90% of the public funding invested.1

In addition to the direct and indirect investment that local authorities receive from sportscotland, the Scottish Government provides local authorities with yearly funding which can be used for investment into the operations and development of sports facilities and swimming pools and parks and open spaces.

This funding is calculated using grant aided expenditure, a needs-based methodology used to provide equitable funding to local authorities based on relative need, with consideration to factors such as population numbers, rurality and deprivation.

The Scottish Government also funds various organisations through the Physical Activity line of the Scottish Government budget. In 2023-2024 this equalled £5 million and was provided to organisations and projects including Paths for All to tackle health inequalities through delivery of a number of key programmes including Scotland's Daily Mile, women and girls in sport related activity and Active Play development.i

UK Government Funding

The UK Government funds performance sport through their NDPB, UK Sport, which provides funding for sports through four-year awards in line with the Olympic and Paralympic cycle.

UK Sport work with organisations to build their case for investment and to agree upon a set of criteria and requirements.

The investment provided is intended to; contribute to the costs to support high-performance athletes; assist sports with growing a more accessible and sustainable system that facilitates the emergence of more high potential athletes; and ensure the most promising athletes can compete at major sporting events.

Information on UK Sport's Current Funding Awards for the upcoming Olympics and Paralympics Games is available on their website. Further significant investment is provided to their partners – including, sportscotland, BOA and BPA – who support Scottish athletes. UK Sport also provides direct funding to select athletes, through the Athlete Performance Award which uses National Lottery income to support living and sporting costs.

There are instances where Scottish sport receives direct funding from the UK Government, including the ongoing investment from the UK DCMS as part of the UK Government's Levelling up Agenda.

In Scotland since 2021, the UK Government has invested £4.1 million in to 40 projects, through the Multi-Sport Grassroots Facilities Programme, and has recently committed to investing in a further 40 projects up to 2025, totalling an additional £11.4 million of funding.

This programme is providing over £320 million of funding to projects across the UK to allow essential improvements to facilities to take place, such as upgrades to grass and artificial grass pitches, installation of floodlights and solar panels, and developments of changing facilities and club houses.

Information about the specific projects in Scotland in receipt of DCMS investment to date, including the amount of funding received, is available on the UK Government wesbite. The UK Government have used financial assistance powers for UK Ministers provided by the Internal Market Act 2020i to fund this programme.ii

National Lottery Funding

National Lottery funding is delivered to sportscotland, and as a National Lottery Fund Distributor, they are responsible for investing this fund within the sector. Funding received from the National Lottery must be administered by sportscotland in accordance with provisions in the National Lottery etc. Act 1993, as amended by the National Lottery Act 1998.

These provisions are:

Policy directions under Section 26A(1) of the National Lottery etc. Act 1993 as read with Section 26A(1)(A) of the National Lottery etc. Act 1993, as amended by the National Lottery Act 1998. This outlines what matters sportscotland must consider when investing National Lottery funding.

Financial directions provided by Sections 26(3), (3A) and (4) as read with section 26(1)(a) of the National Lottery etc. Act 1993, which states that sportscotland must comply with the Statement of Financial Requirements. These requirements relate to applications for National Lottery funding, approving applications and payment of grants and other general administrative and financial matters surrounding National Lottery funding.

Accounts directions provided by Section 35(3) of the National Lottery etc. Act 1993. These directions outline how sportscotland should approach the reporting of their accounts relating to National Lottery monies. As per directions given by Scottish Ministers, sportscotland must prepare separate annual statements of accounts relating to the expenditure of National Lottery investment – these annual reports can be viewed on the sportscotland website.

National Lottery investment into sportscotland, and the trend in recent years is highlighted in Figure 2.

Sportscotland's Role in Funding

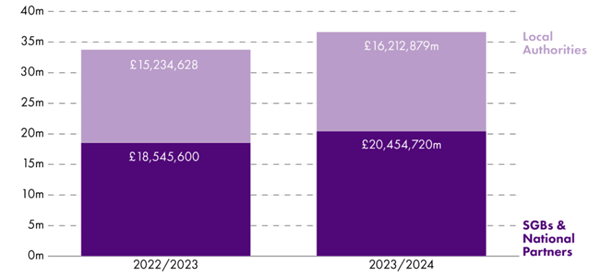

Sportscotland directly invests into 47 SGBs. This investment is utilised to contribute to building towards achieving Active Scotland outcomes, deliverable against various SGB-specific development and performance outcome measures.

Furthermore, sportscotland provide direct funding to local authorities, on top of what local authorities receive from the Scottish Government, to support Community Sports Hubs, coaching, volunteering, and delivery against Active Schools outcomes.

Sportscotland provide additional investment through specific funds such as Awards for All and the Sports Facilities Funds, which local authorities, organisations, clubs and SGBs can apply to.

Sportscotland reported they would be investing "record annual investment figures to support the delivery of sport and physical activity" for 2023/24.1 Funding of £36.7 million – an 8.6% increase on 2022/2023 - was announced to provide further support to their partners in the delivery of sport and physical activity across Scotland. A high-level breakdown of funding issued to SGBs, national partners and local authorities is outlined in Figure 3.

Further information on how sportscotland invests in SGBs and local authorities to further support the sector's delivery against Active Scotland outcomes is detailed in sportscotland's report, 'Investment in SGBs and Local Authorities'.

Historical information of sportscotland's direct, and in some cases additional, investment into clubs, local authorities, SGBs and National Partners, and Sports Facility Funds between 2013-2014 and 2022-2023 is available on sportscotland's website.

Sportscotland's Funding and Expenditure Trends

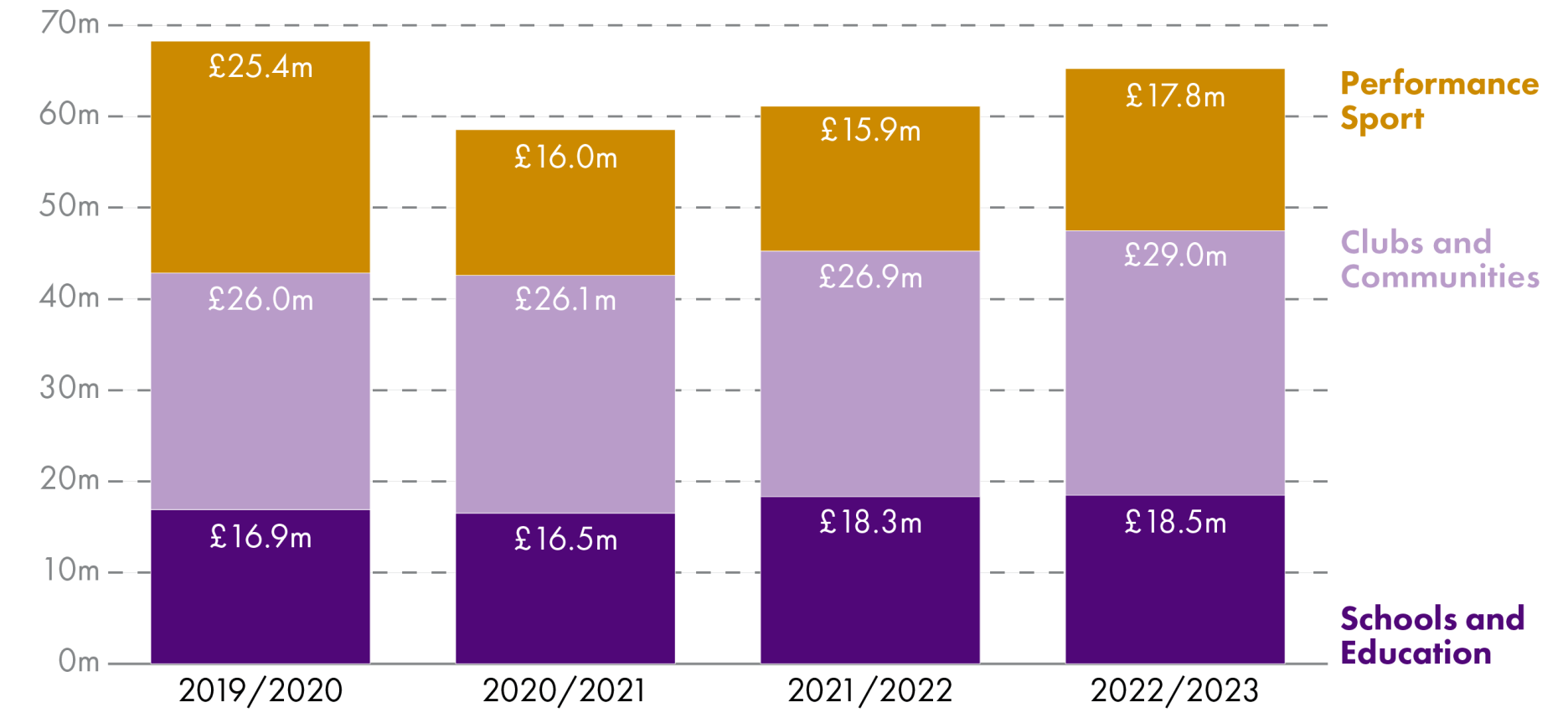

Figure 2 above illustrates Scottish Government and National Lottery investment into sportscotland from 2019-2023. Figure 4 breakdowns sportscotland's expenditure in this same timeframe.

From 2019-2020, sportscotland streamlined the presentation of their expenditure, with data now only available for spending on schools and education, clubs and communities, and performance sport. Funding and expenditure data was derived for the corresponding sportscotland annual review for each given year. Every annual review dating back to 1999-2000 is available on the sportscotland website.

Funding over four years up to 2022/2023 decreased slightly (2019/2020 – 2022/2023; -4.7%). However, this decrease does not reflect the larger decrease in real terms funding that was felt as a result of the impact of inflation on sport organisations.

Sportscotland notes that the differences between funding (Figure 2) and expenditure (Figure 4) are attributable to the commitment to projects that are yet to commence at the time of year-end reporting.

As sportscotland's annual review for 2023/24 has not yet been published, their confirmed funding and expenditure is not yet publicly available. Funding information has been pulled from other sources for 2023/24 and 2024/25 and is displayed in Figure 5.

Scottish Government funding for sportscotland for 2023/2024 and 2024/25 is taken from the Scottish Budget: 2024 to 25 report.4

SPICe has published a blog – Scottish Budget 2024-25: All about the data – and its interactive budget comparison tool allows for comparisons between the 2023/2024 and 2024/2025 budgets, and can account for Spring Budget revision and inflation adjustments.

Estimates of National Lottery funding are provided which are forecasted in sportscotland's National Lottery Distribution Fund (NLDF) Annual Report and Accounts 2022-2023. This report indicates that National Lottery Distribution Fund estimates are based on Gambling Commission forecast revenue in those years, whilst Balance Spend represents the planned capital spending and use of balance to support planned investment.

Community Outreach Programmes

Community programmes use sport and physical activity as a way to address wider issues within individuals and communities. These issues include inclusion, inequality, health and wellbeing, mental health, social skills, employability, and preventing criminal (re-)offences.

Programmes that have successfully delivered, and continue to deliver, on these outcomes include Changing Lives through Sport and Physical Activity and CashBack for Communities.

As these programmes use sport and physical activity services and session to facilitate their delivery of wider, non-sporting outcomes, it can be difficult to quantify exactly how much funding is invested into the sport-specific components of programmes.

CashBack for Communities utilises funds that have been recovered through the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002. Further information on how CashBack for Communities invests in partner organisations, what the partner programmes entail, and how the investment is spent across local authorities is available on the CashBack for Communities website.

Spirit of 2012 highlighted that approximately £1 million worth of investment between August 2018 and August 2021 supported over 13,000 people in sustained and taster activities through the Changing Lives through Sport and Physical Activity programme:

[improving] their wellbeing, inclusion, life skills and community connections.

Spirit of 2012. (2022). Changing Lives Through Sport and Physical Activity Fund Report. Retrieved from https://spiritof2012.org.uk/insights/changing-lives-through-sport-evaluation/

Key Issues in Scottish Sport

This section will discuss some of the important issues present in Scottish sport. These include participation trends and inequalities, facilities, the value of community sport and supporter representation.

Participation in Sport and Physical Activity

Physical inactivity is considered to be one of the four modifiable behaviours - along with tobacco use, unhealthy diet and harmful use of alcohol - that increases the risk of non-communicable diseases.1 There are various health benefits associated with physical activity including physical, mental and cognitive benefits and improved overall wellbeing.2

Participation Trends

The Scottish Health Survey (SHeS) assesses adherence to the guidelines for moderate or vigorous physical activity (MVPA) and muscle strengthening activity outlined by the UK Chief Medical Officers.i The most recent report presents data collected in 2022, with some key findings outlined below.2

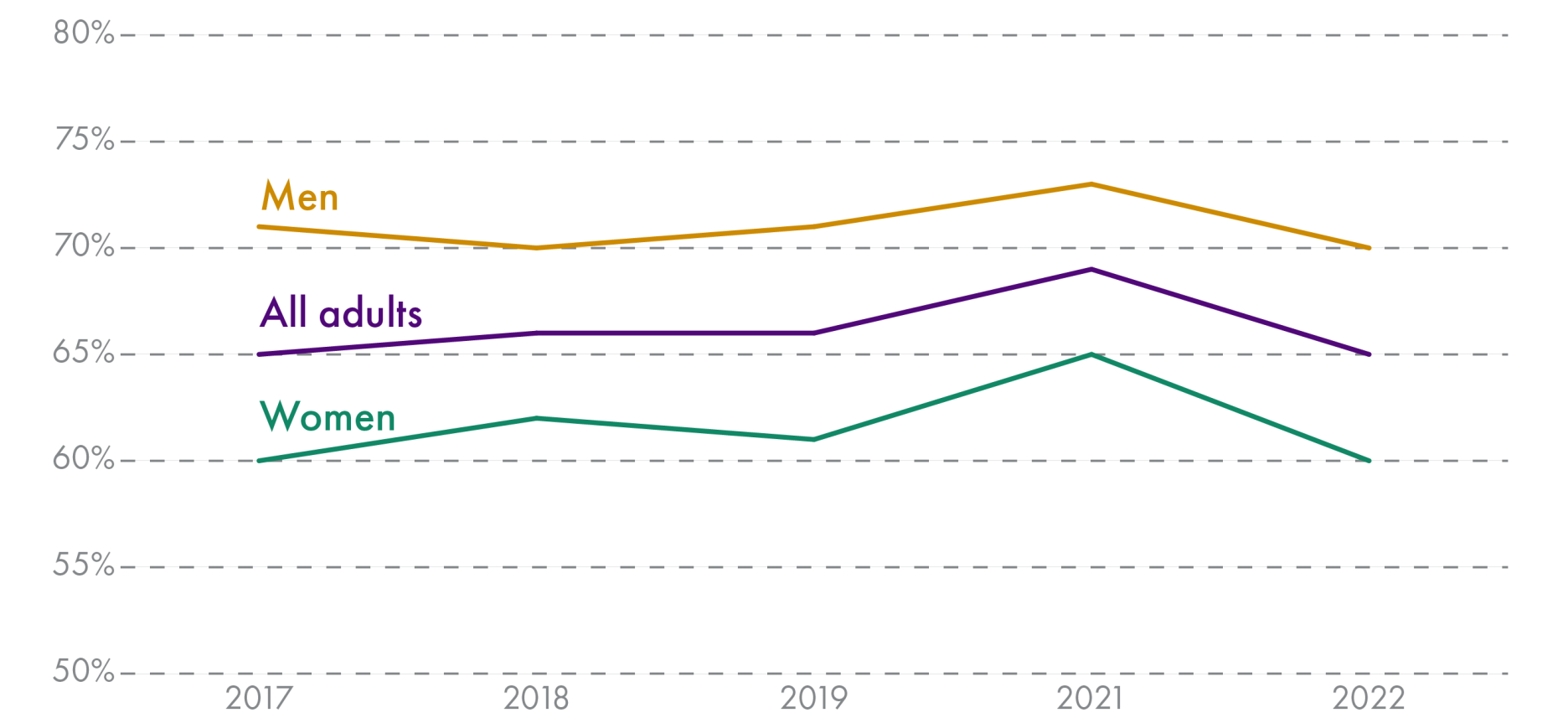

In 2022, 65% of adults in Scotland met the MVPA guidelines, which is down from 69% in 2021. A higher proportion of men (70%) met the MVPA guidelines than women (60%). Figure 6 highlights the trend in recent years.

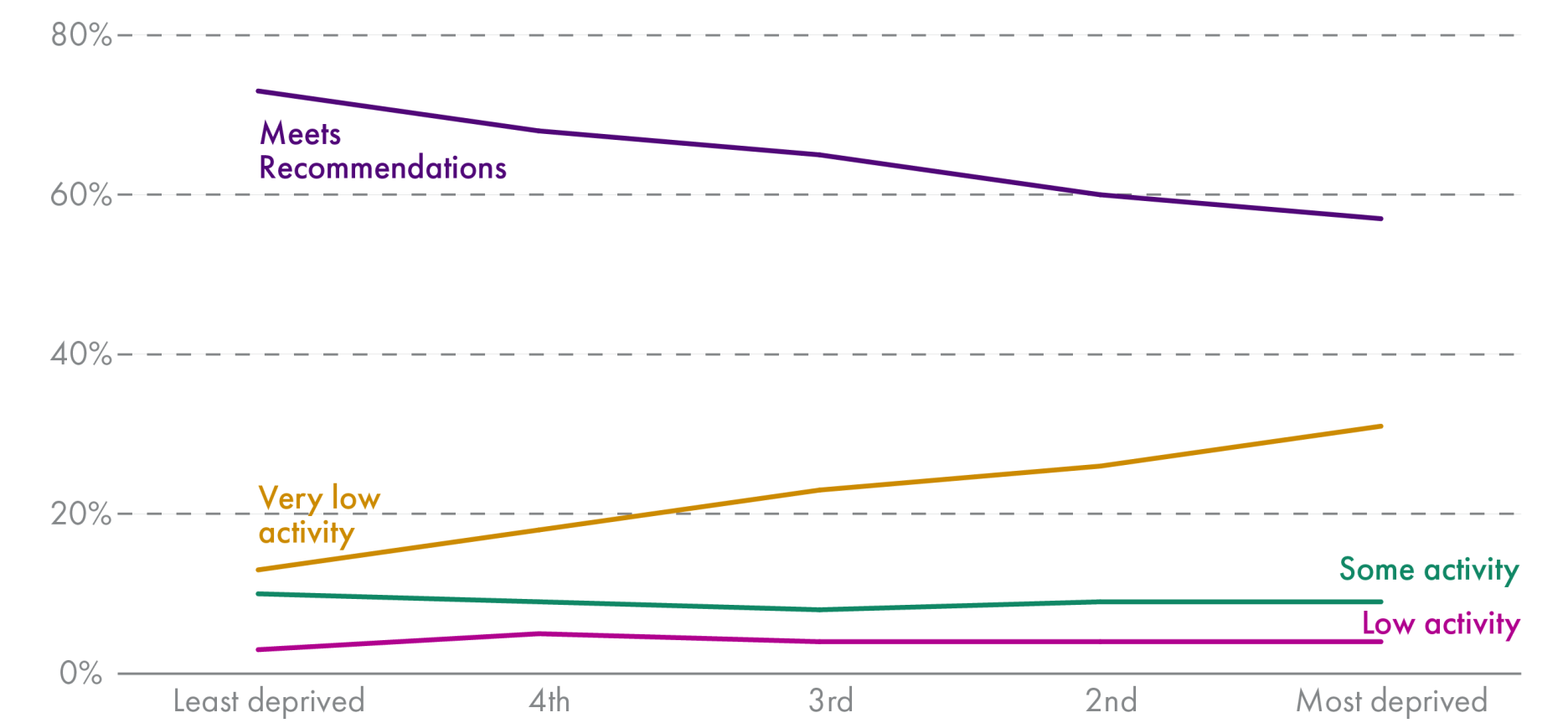

The proportion of adults meeting the MVPA guidelines was lower in the most deprived areas (57%) than the least deprived areas (73%), as shown in Figure 7.

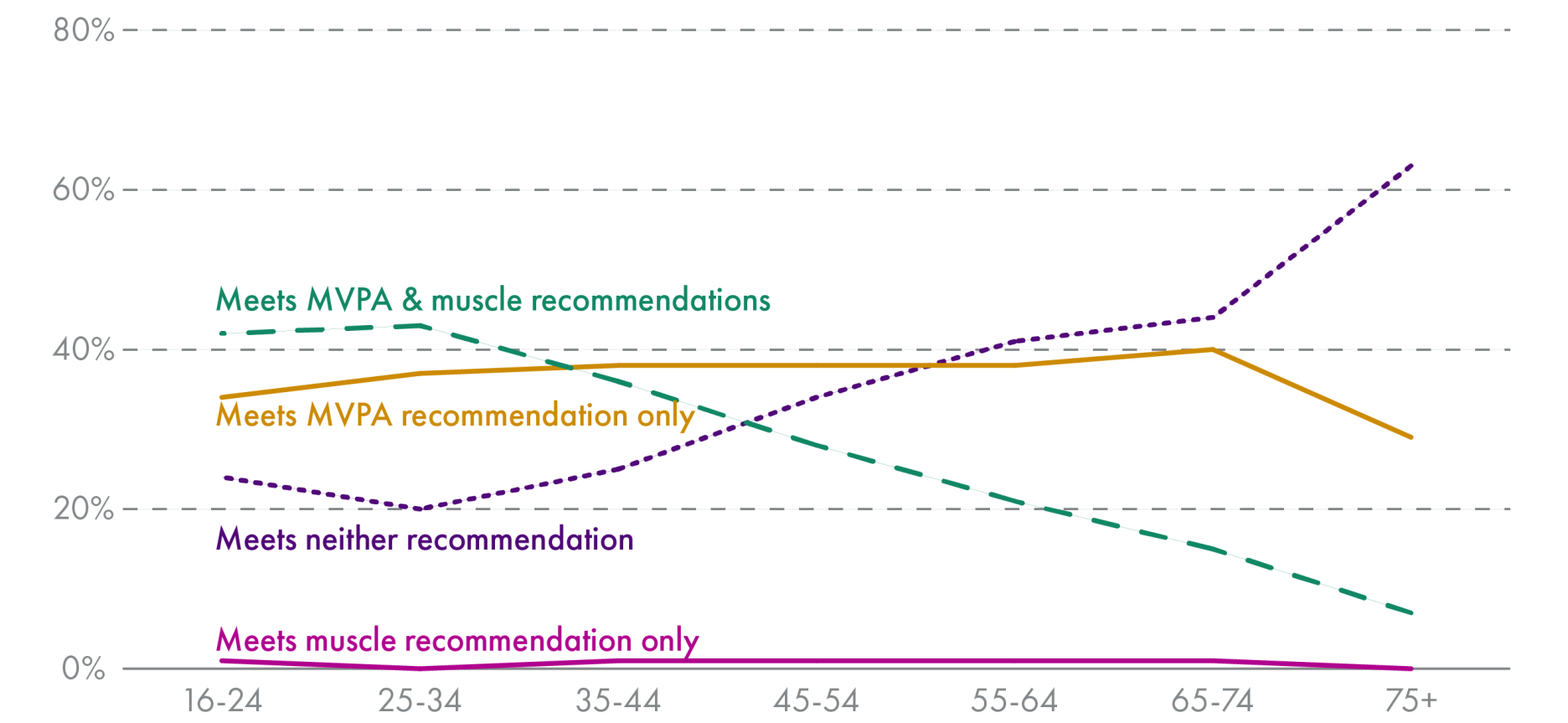

Figure 8 indicates that the proportion of adults meeting the MVPA guidelines declines with age. In addition, the proportion of adults meeting neither MVPA or muscle strengthening activity guidelines increased with age.

The Scottish Government collects information on physical activity and sport participation through the Scottish Household Survey (SHS). The most recent report highlights official statistics from data collected in 2022.6

Key findings include:

Walking (for at least 30 minutes recreationally) was by far the most popular form of physical activity and sport among Scottish adults, as 74% reported participating in the past four weeks. Almost one in five (18%) reported participating in no physical activity or sport in the past four weeks.

Males were more likely to participate in all forms of physical activity and sport in the last four weeks except for recreational walking (73% vs. 75%), swimming (14% vs. 15%), keep fit/aerobics (9% vs. 16%) and dancing (3% vs. 9%).

Participation Inequalities

Research, including the SHeS and SHS surveys, indicate that participation inequalities exist across Scotland, including between SIMD1 and SIMD5i quintiles, and between males and females.

The SHS highlights that finding the time (SIMD1 - 33%; SIMD5 - 37%) and not being interested (SIMD1 - 18%; SIMD5 - 16%) were barriers to sport that did not vary much between deprivation levels. However, the cost of participating (SIMD1 - 12%; SIMD5 - 4%) and current health status not being good enough (SIMD1 - 31%; SIMD5 - 11%) were barriers that were more commonly cited by respondents from the most deprived areas.1

The Sport and Social Inequality report for the Observatory for Sport in Scotland discusses this issue.2 The report highlights that educational attainment, socio-professional category, financial position - which are all considered in the SIMD model - can negatively impact participation in sport and physical activity.

Understanding the barriers and finding ways to improve female participation in sport and physical activity in sport is an important issue in Scotland.

The Scottish Parliament's Health, Social Care and Sport Committee recently undertook an inquiry into female participation in sport.3 They took evidence from stakeholders including former sportspersons, leisure trust representatives, SGBs, third-sector charities, sportscotland, and various other organisations and, in their report, highlighted barriers to participation in teenage girls and women of all ages.

Among teenage girls, barriers included puberty, gendered/restricted activity offerings, competition focus rather than fun, negative attitudes from boys and boys dominating playgrounds in schools.

Meanwhile women of all ages outlined barriers such as women’s health, a lack of positive role models, negative body image, lack of self-confidence, caring responsibilities, harassment and safety concerns, and issues surrounding facilities and changing rooms.

The SHeS survey indicates that amongst adults not meeting the MVPA guidelines, the reasons for not participating in physical activity did not differ significantly between sexes (and age).4 However, the barriers listed in the SHeS multiple-choice questionnaire did not include the majority of those listed in the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee's report. Therefore these female-specific reasons were not represented in the SHeS report's findings.

Sportscotland, through their Sport for Life strategy, outline a focus on addressing issues surrounding equality, diversity and inclusion.5 Similarly, the Scottish Government has said that the Active Scotland Delivery Plan is under revision, and a focus on addressing inequalities will underpin future actions taken.ii

Previous and existing initiatives that have been utilised to address sport and physical activity participation inequalities can be found within the Active Scotland Outcomes Framework. These include:

The National Walking Strategy and the Daily Mile.

The Active Schools and Active Girls programmes.

Encouraging and supporting clubs and communities to engage with people at risk of inactivity through CSHs, SGBs and Direct Club Investment.

Supporting opportunities for people with learning disabilities and autism through the Keys to Life strategy and the Scottish Strategy for Autism.

Non-Binary and Transgender Participation

Sport has historically been separated into two mutually-exclusive categories – male and female. This leads to issues surrounding the inclusivity of sport to non-binary and transgender people, when considering sporting spaces, changing facilities, clothing and competitions, among other barriers.1

On the other hand, concerns have been raised by cis women surrounding the safety of shared spaces. This concern was highlighted in the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee's inquiry into female participation in sport and physical activity. The report states:

Some respondents were concerned that the presence of trans women in female-only spaces may lead to women feeling unsafe.

Concerns have also been raised regarding the inclusion of transgender athletes in elite competitions. Indeed, some governing bodies have banned transgender athletes from participating in female-only competitions if they have gone through male puberty.2

Scottish Government and Sportscotland Actions

The Scottish Government's Non-Binary Equality Action Plan outlines the actions that the Scottish Government will take to improve equality and bring about real, positive and lasting change to the lives of non-binary people in Scotland.1 It outlines the following sport-related objective:

Non-binary people increasingly feel welcomed and able to take part in sport.

Scottish Government. (2023, November 16). Non-Binary Equality Action Plan. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/non-binary-equality-action-plan/pages/12/

The plan outlines that intended actions are due to a partially accepted recommendation from the Working Group on Non-Binary Equality. The recommendation stated the Scottish Government should:

Fund specific work to reduce barriers to trans and non-binary people's participation in sport.

Scottish Government. (2022, July 13). Non-Binary Equality Working Group: report and recommendations - March 2022. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/non-binary-working-group-report-recommendations-march-2022/documents/

The Scottish Government commitment states that they will:

Support sportscotland to reduce barriers to trans and non-binary people's participation in sport.

Scottish Government. (2023, November 16). Non-Binary Equality Action Plan. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/non-binary-equality-action-plan/pages/12/

The actions stated in the plan include to:

Support sportscotland to deliver workshops and learning opportunities to SGBs on guidance for transgender participation in domestic sport.

Support sportscotland to allocate resources to offer one-to-one support to SGBs that wish to develop new policies for transgender participation in their sport.

In September 2021, the five UK Sports Councilsi published guidance on transgender participation in sport, aiming to support sports in better understanding the needs and challenges involved in ensuring that everyone can take part.

SGB Actions

Some SGBs have taken steps to address the barriers faced by non-binary and transgender people when accessing sport. These actions include:

Scottish Athletics have made it compulsory for all Scottish Athletics championship events, including external events held on their behalf, to include a non-binary category within the event entry options.1

Scottish Swimming have issued guidance for Aquatics Participation & Training Information for Transgender & Non-Binary Individuals, and a policy document for Aquatics Sports Competition Information Transgender & Non-Binary Individuals.

On the other hand, some SGBs have introduced rules and policies which have excluded non-binary and transgender individuals from certain sporting events. For example, Scottish Rugby have updated their policy meaning that contact rugby in the women's category is limited to those whose sex was recorded female at birth.2

Acknowledging the Value of Community Sport

Recent research has suggested that a shift in public policy is necessary. In order to harness the potential of community sport, this research has stated that policy development must focus on social disadvantage, addressing inequality of opportunity and recognising the impact of community sport on various wellbeing markers.123

[...] the positioning of sport within the Department of Health and Social Care in Scotland does provide the opportunity for more joined up policy for the realisation of improved health outcomes. The downside is that sport receives a limited percentage of the health and social care budget. Whilst the political and economic imbalance between Scotland and England remains, the level of investment in sport and physical activity is a political choice by the Scottish Government. We argue that the real terms cut in funding for sport and physical activity since 2016 is evidence of a lack of commitment to sport and physical activity above and beyond the health and wellbeing rhetoric.

Meir, D., Brown, A., Macrae, E., & McGillivray, D. (2023). Country profile: sport and physical activity policy in Scotland. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 16(1), 181-197. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2023.2271940

Some of the benefits of community sport are discussed below.

Addressing Wider Community Issues

There are several features of community sport activities that allow them to be a setting well-suited to addressing wider issues in socially disadvantaged individuals and communities.

This includes that they are local, financially accessible and typically non-competitive activities that allow initiatives to engage with the hard-to-reach, vulnerable groups, enhancing their ability to handle adversity.1

Community sport activities in Scotland are used to address wider issues in communities and individuals. These issues include mental wellbeing, social skills and social exclusion, employment and education opportunities, and preventing offenders from re-offending.13

CashBack for Communities

Introduced in 2008, CashBack for Communities is a Scottish Government initiative that utilises funds recovered through the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (POCA).

In 2012, SPICe published a briefing on Community Sport1 which touched on the CashBack for Communities Programme and the funding it provides to community sport in Scotland. The programme has since significantly evolved to become more aligned with the Scottish Government's Vision for Justice, and is a key component of the Serious Organised Crime Taskforce ‘Divert’ strategy. There is now a far greater focus on the non-sporting outcomes outlined in the CashBack for Communities logic model, moving away from a focus on delivering mass-participation sporting activities.2 Funds are invested into community programmes to support Scottish Government Justice Aims by:

focusing on young people at risk of entering the criminal justice system and the communities most affected by crime.

CashBack for Communities delivers a range of trauma-informed and person-centred services and activities for young people aged 10-25 years old, through funding provided to its various partner organisations. Themes covered by projects include sport and physical activity, in addition to arts and culture, employability, youth work and personal skills development.

Phase 6 of the programme runs from April 2023 to March 2026. Up to £20 million has been committed to Phase 6, funding a wide range of sporting and third sector organisations to deliver projects against defined programme objectives. Due to the unpredictable nature of POCA receipts, it is too early to confirm whether there will be a further phase of Cashback or what the objectives will be.i

The main aims of Phase 6 are to deliver projects that:

Support young people most at risk of being involved in antisocial behaviour, offending or re-offending towards, or into, positive destinations.

Provide person-centred support for young people, parents and families impacted by Adverse Childhood Experiences and trauma.

Support young people to improve their health, mental health and wellbeing.

Support people, families and communities most affected by crime.

Phase 6 provides funding to various sporting organisations, which deliver some sport and physical activity sessions, including the SFA, basketballscotland, and Scottish Rugby. However, these organisations use sport to appeal to and engage with young people in wider, multi-faceted projects with a broader focus on employability, personal development and helping young people to achieve their full potential. Therefore, sport participation numbers and development of sporting progression pathways are not directly measured as programme outcomes.

Although CashBack for Communities is now more firmly aligned with Justice outcomes, sport and physical activity remain an integral component of the work delivered. The external Impact Evaluation of Phase 5 (2020-2023) highlighted that:

Some projects, particularly those involving sport and physical activity, made a positive impact to young people's physical health. Young people highlighted that taking part in activity sessions helped them to feel fitter, stronger and healthier. Many indicated that if not involved in CashBack activity they would have been more sedentary and spent more time at home and indoors.

CashBack for Communities. (2023, November). Impact Evaluation: Phase 5 (2020 to 2023) CashBack For Communities. Retrieved from https://cashbackforcommunities.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/CashBack-Phase-5-Final-Evaluation.pdf

Changing Lives through Sport and Physical Activity

In a similar vein to CashBack for Communities, the Changing Lives through Sport and Physical Fund, utilised sport and physical activity to address wider community and individual needs. A core element of the wider Changing Lives work, this fund provided short-term resources into the sport and community sector, through collaboration between sportscotland, Scottish Government, the Robertson Trust and Spirit of 2012. Emerging from 2017's Sport for Change research, it provided 17 partnership organisations with funding to deliver projects that would achieve two key aims:

To address wider issues – related to inclusion and equality, social skills, health and wellbeing and skills for life, learning and employment – through sport and physical activity, and to support people to become and stay active.

To facilitate collaboration between sporting and non-sporting organisations to intentionally use sport and physical activity to achieve positive change.

Spirit of 2012 highlighted that approximately £1 million worth of investment between August 2018 and August 2021 supported over 13,000 people in sustained and taster activities:

[improving] their wellbeing, inclusion, life skills and community connections.

Spirit of 2012. (2022). Changing Lives Through Sport and Physical Activity Fund Report. Retrieved from https://spiritof2012.org.uk/insights/changing-lives-through-sport-evaluation/

Street Soccer Scotland

Street Soccer Scotland delivers football activities and personal development opportunities to socially disadvantaged groups across Scotland. This organisation delivers free football-themed services specifically tailored to adults (16+ years-old) and youth (under 16 years-old), in addition to a variety of activities for females, refugees and people in prisons. They work with a number of partners to deliver their services, including sportscotland, the SFA and the Scottish Government. Through their partnership with Edinburgh Napier University, attendees can gain recognised qualifications – such as Scottish Credit and Qualifications Frameworks (SCQFs) – and undertake a variety of modules including preparing for employment, communication skills and Street Soccer coaching. Further information about Street Soccer Scotland and ways to get involved is available on their website.

Community Sport and Healthy Ageing

Recently published research has highlighted the role that sport and physical activity participation can play in healthy ageing in Scotland’s older population.1

Scotland’s older population (65+ year-olds as a proportion of the total population) is estimated to grow from 19.4% to 25.5% by 2045. Yet, life expectancy (LE) from birth and healthy life expectancy (HLE) are in decline, and with disease free life expectancy (DLFE) at age 65 are all below the UK average – LE and DLFE are the lowest in the UK.

A number of factors have profound impacts on life expectancy, one of which is physical activity. Community sport has the potential to improve physical activity participation trends in older age groups. Sport participation has a number of recognised physical, social and psychological health benefits and can reduce mortality rates, however physical inactivity is seen to increase with age.

This research has urged that a tailored approach to sport and physical activity promotion be taken in order to better engage with older age groups. Various studies have highlighted that the social aspect of sport and physical activity sessions is a significant motivator for older age groups participating in physical activity, more so than in younger age groups.

The Scottish Health Survey 2022 highlights that the social aspect of physical activity was the third most commonly reported reason for participation amongst those aged 75+ years-old ("Just enjoy it" - 28%; "to keep fit [not just to lose weight] - 27%; "to socialise" - 20%). This reason was reported less in all other age groups, although it was the third most commonly reported reason among those aged 16-24 years-old (12%).2

An organisation that promotes its activities in such a way is jogscotland, which has over 330 free jog groups across Scotland. Whilst not solely delivered to older population groups, jogscotland promote their jogging groups as being “fun” and “friendly” and that they allow runners of all abilities to exercise in a “sociable, supportive environment.”

Facilities Review

The availability, accessibility, affordability and condition of sporting facilities are known to be key factors in enabling people to participate in sport. Despite this importance being widely acknowledged, the last comprehensive review of Scottish sports facilities was published almost 20 years ago.1 This review presented several key findings of Scotland's, at the time, approximately 6,000 sports facilities.

Key findings included:

74% of natural grass pitches, 61% of synthetic grass pitches and 50% of tennis courts needed replacement or significant upgrading.

49% of changing pavilions required replacement or significant upgrading.

Club-owned facilities were typically in better condition than those owned by local authorities, however the Public and Private Partnership scheme was beginning to shift this tide.

With no recent comprehensive review of the nation's sports facilities published, it is difficult to assess if improvements have been made. This is recognised by the Scottish Government and in the Minister's Strategic Guidance Letter for 2023-2026, sportscotland were encouraged to undertake a review of the sport facilities estate – this work is now underway.i

Swimming Facilities Review

There are some recent reviews of facilities for specific sports. For example, Scottish Swimming published ‘The Future of Swimming Facilities in Scotland’, in November 2023.1 This report touches on issues including the number, lifespan, condition of facilities, in addition to the financial strains that rising energy costs impose upon them.

As of 2023 there are 396 public pools in Scotland, increasing from 338 pools which was indicated in the Ticking Time Bomb report in 2001.2 On average, five pools across four sites are built each year in Scotland, which is in line with estimations that will ensure adequate provision.1

The potential lifespan of a swimming pool is estimated to be between 38-60 years old. Although, Swim England state that their average age of closure is 38 years, this number will soon increase as more facilities close, as over 40% of their operational swimming pools are over 38 years old. Using predictive modelling, the Scottish Swimming report highlighted that Scotland would observe a decrease in the number of public swimming pools up to 2040, when considering both a maximum 38-year and 60-year lifespan.

If a facility over 40 years old is considered to be at risk of closing, the number of public pools at risk of closure in 2023 is 147 and is projected to rise to up to 279 by 2040. The report highlights that increased investment in facility refurbishment and replacement would help to address this trend. In addition, their review of the condition of swimming facilities highlighted that, in tandem with the findings of the Ticking Time Bomb report, facilities can be operational for up to 60 years provided they are maintained and refurbished adequately. Indeed, there are a number of operational facilities which are over 60 years old, due to investment and commitment to appropriate maintenance.

Swimming pool facilities have felt the pressures of rising energy costs and have implemented various measures to combat these costs. These include reducing opening hours, increasing admission prices and discontinuing, or increasing charges for, community programmes. These measures directly impact on the accessibility, affordability and availability of facilities – factors which are known to affect use of facilities and sport participation. However, this review did not assess the number of facilities that implemented these measures.

Sport Leadership and Supporter Representation

Professor Grant Jarvie's 2019 report outlines some issues surrounding leadership in the Scottish sporting landscape.1 These issues include gender and racial/ethnic imbalances in leadership positions and a need for greater strategic and diverse leadership across Scottish sport.