Hazardous Substances: planning framework

This briefing discusses the Hazardous Substances (Planning) Common Framework. The Hazardous Substances (Planning) Common Framework sets out how the UK and devolved governments propose to work together on land-use planning for sites containing hazardous substances. This briefing also provides background information on the common frameworks programme.

Summary

This briefing provides detailed information on the Hazardous Substances (Planning) Common Framework. The Hazardous Substances (Planning) Common Framework sets out how the UK and devolved governments propose to work together on land-use planning for sites containing hazardous substances. The Hazardous Substances (Planning) Common Framework was considered in session 5 by the Local Government and Communities Committee. A final version of the framework was published on 21 August 2021. This briefing considers the final version of the framework.

Background information on, for example, what common frameworks are and how they have been developed is provided in this paper.

The SPICe common frameworks hub collates all publicly available information on frameworks considered by committees of the Scottish Parliament.

In Session 5, the Finance and Constitution Committee reported on common frameworks and recommended that frameworks should include the following:

their scope and the reasons for the framework approach (legislative or non-legislativei) and the extent of policy divergence provided for;

decision making processes and the potential use of third parties;

mechanisms for monitoring, reviewing and amending frameworks including an opportunity for Parliamentary scrutiny and agreement;

the roles and responsibilities of each administration; and

the detail of future governance structures, including arrangements for resolving disputes and information sharing

The Scottish Government’s response highlighted that there may be a "range of forms" which frameworks could take.

More detail on the background to frameworks is available in a SPICe briefing and also in a series of blogs available on SPICe spotlight.

What are common frameworks?

A common framework is an agreed approach to a particular policy, including the implementation and governance of it. The aim of common frameworks is to manage divergence in order to achieve some degree of consistency in policy and practice across UK nations in areas formerly governed by EU law.

In its October 2017 communique on common frameworks, the Joint Ministerial Committee (EU Negotiations) (JMC (EN)) stated that:

A framework will set out a common UK, or GB, approach and how it will be operated and governed. This may consist of common goals, minimum or maximum standards, harmonisation, limits on action, or mutual recognition, depending on the policy area and the objectives being pursued. Frameworks may be implemented by legislation, by executive action, by memorandums of understanding, or by other means depending on the context in which the framework is intended to operate.

Joint Ministerial Council (EU Negotiations), 16 October 2017, Common Frameworks: Definition and Principles

The Scottish Government indicated in 2019 that common frameworks would set out:

the area of EU law under consideration, the current arrangements and any elements from the policy that will not be considered. It will also record any relevant legal or technical definitions.

a breakdown of the policy area into its component parts, explain where the common rules will and will not be required, and the rationale for that approach. It will also set out any areas of disagreement.

how the framework will operate in practice: how decisions will be made; the planned roles and responsibilities for each administration, or third party; how implementation will be monitored, and if appropriate enforced; arrangements for reviewing and amending the framework; and dispute resolution arrangements.

However, the Food and Feed Safety and Hygiene Law framework outline considered by the session five Health and Sport Committee noted that:

the framework itself is high level and commits all signatories to early, robust engagement on policy changes within scope.

Framework Outline Agreement and Concordat, 30 November 2020

The framework outline went on to note that the framework:

is intended to facilitate multilateral policy development and set out proposed high level commitments for the four UK Administrations. It should be viewed as a tool that helps policy development, rather than a rigid template to be followed.

As such, it is likely that there will be significant variation between frameworks in terms of whether they set policy or set out how decisions on policy within the scope of the framework will be taken.

There are, however, similarities between frameworks in terms of their overall structure, with the agreements setting out the roles and responsibilities for parties to the framework, how the framework can be reviewed and amended, and how disputes are to be resolved.

What is the Hazardous Substances framework?

The framework was drafted prior to EU Exit and therefore sets out some of the key restrictions on divergence between the UK Government and devolved governments that previously existed under EU regulation. These are listed in the box below.

The key restrictions were that the UK Government and devolved governments:

i) were unable to change the definition of what an establishment was (in short, a location where dangerous substances are present in significant quantities);

ii) could not lower standards on what constituted a dangerous substance (i.e. by removing categories of substances or individual substances from the list, or raising the threshold at which the quantity became significant and the establishment fell into scope of the regime);

iii) were required to ensure that the objectives of preventing major accidents and limiting the consequences of such accidents for human health and the environment were taken into account in their land-use policies, through controls on the siting of new establishments and new developments close to establishments;

iv) were required to set up appropriate consultation procedures to ensure that operators provided sufficient information on the risks arising from the establishment and that technical advice on those risks was available when decisions were taken; and;

v) were required to facilitate public involvement at various stages of decision-making on relevant applications for consent or plans and programmes.

The framework also discusses what may become possible following EU exit, for example, it explains:

In simplified terms, what may become possible following the UK's exit from the EU that was not possible before is that the UK Government and devolved governments will have the powers within a domestic context to relax requirements on the level of substances that can be held before triggering the regime and relax the process around what is required once the regime is triggered.

Why are common frameworks needed?

During its membership of the European Union, the UK was required to comply with EU law. This means that, in many policy areas, a consistent approach was often adopted across all four nations of the UK, even where those policy areas were devolved.

On 31 December 2020, the transition period ended, and the United Kingdom left the EU single market and customs union. At this point, the requirement to comply with EU law also came to an end. As a result, the UK and devolved governments agreed that common frameworks would be needed to avoid significant policy divergence between the nations of the UK, where that would be undesirable.

The Joint Ministerial Committee (JMC) was a set of committees that comprises ministers from the UK and devolved governments. The JMC (EU Negotiations) sub-committee was created specifically as a forum to involve the devolved administrations in discussion about the UK’s approach to EU Exit. Ministers responsible for Brexit preparations in the UK and devolved governments attended these meetings.

In October 2017, the JMC (EN) agreed an underlying set of principles to guide work in creating common frameworks. These principles are set out below.

Common frameworks will be established where they are necessary in order to:

enable the functioning of the UK internal market, while acknowledging policy divergence;

ensure compliance with international obligations;

ensure the UK can negotiate, enter into and implement new trade agreements and international treaties;

enable the management of common resources;

administer and provide access to justice in cases with a cross-border element; and

safeguard the security of the UK.

Frameworks will respect the devolution settlements and the democratic accountability of the devolved legislatures, and will therefore:

be based on established conventions and practices, including that the competence of the devolved institutions will not normally be adjusted without their consent;

maintain, as a minimum, equivalent flexibility for tailoring policies to the specific needs of each territory, as is afforded by current EU rules; and

lead to a significant increase in decision-making powers for the devolved administrations.

What is the process for developing frameworks ?

Frameworks are inter-governmental agreements between the UK Government and the devolved administrations.

They are approved by Ministers on behalf of each government prior to being sent to all UK legislatures for scrutiny.

The UK Government Cabinet Office is coordinating the work on developing common frameworks.

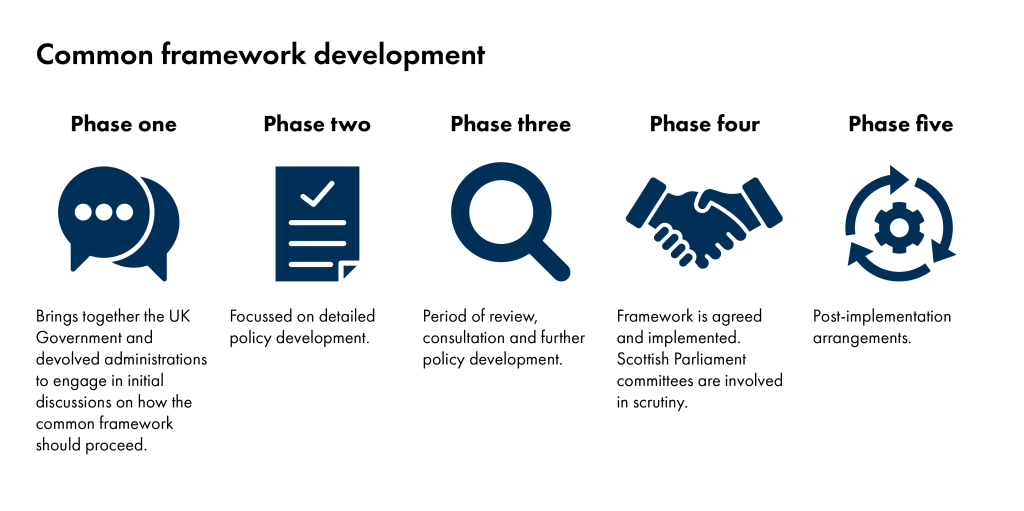

Common frameworks go through four phases of development before implementation at phase five. The stages are set out below. The parliament receives frameworks for scrutiny at phase four.

How will the Scottish Parliament consider frameworks?

Frameworks which have reached phase four are available to be considered by the Scottish Parliament. Subject committees can consider frameworks which sit within their policy areas.

Each legislature in the UK can consider common frameworks. Issues raised by legislatures during this scrutiny are fed back to their respective government. Governments then consider any changes which should be made to frameworks in light of scrutiny by legislatures before implementing the framework. Changes in light of scrutiny are not, however, a requirement.

The Constitution, Europe, External Affairs and Culture Committee has an oversight role in relation to frameworks and will lead on cross-cutting issues around transparency, governance and ongoing scrutiny.

The Scottish Government has previously acknowledged the ongoing role of the Scottish Parliament in relation to frameworks:

Consideration will also need to be given to what role the Parliament might have in the ongoing monitoring and scrutiny of frameworks post-implementation.

Scottish Government response to the Session 5 Finance and Constitution Committee report on common frameworks, June 2019

The Scrutiny Challenge

The way in which common frameworks have been developed and will operate raises some significant scrutiny challenges for the Scottish Parliament.

Common frameworks are intergovernmental agreements and the scope for parliamentary influence in their development is significantly limited with scrutiny taking place at phase four.

The ongoing operation of frameworks will take place at an official level between government departments. It is therefore unclear how much information the Parliament may be able to access to scrutinise the effect of frameworks on policy-making.

The Scottish Government and the UK Government have differing objectives in relation to frameworks. The UK Government is seeking “high levels of regulatory coherence”1. The Scottish Government believes that they are about “allowing legitimate policy choices”1.

The interconnected nature of common frameworks and the UK Internal Market Act 2020 (see section on the UK Internal Market Act).

The impact of common frameworks on the Scottish Government’s stated policy position of keeping pace with EU law.

The fact that most frameworks have been operating on an interim basis since 1 January 2021 in spite of being unavailable for scrutiny by legislatures3.

The legacy expert panel report to the session five Finance and Constitution Committee noted these scrutiny challenges. The Committee had previously recommended that the Scottish Government should have to report on the operation of each common framework, noting interactions with cross-cutting issues such as keeping pace with EU law, on an annual basis.

Session 5 scrutiny at the Scottish Parliament

The framework was considered by the Local Government and Communities Committee in session 5. The Convener wrote to then Minister for Local Government, Housing and Planning, Kevin Stewart. It noted that it agreed with the Minister's assessment that the framework:

raises no contentious issues, and that it can be operated without restriction of devolved powers, with little scope for market impact.

The Committee requested further clarification on the framework's interaction with future international agreements and the conditions under which parties may agree to disagree. With regards to engagement with legislatures, the Committee wrote:

Is it envisaged that administrations will periodically report to legislatures on how effectively the Framework is operating and on any elements of it that, on the basis of experience, require to be revised? We think this Framework –and Frameworks in general– would benefit from such a commitment, and the opportunity it would provide for stakeholders to provide informed commentary on how the agreement has bedded in. If this is agreed, we suggest that parties consider writing it into the Framework itself, to underwrite this commitment. There might be merit in there being a report to legislatures within the first, say, 18 months of the Framework becoming operational. Thereafter, reports could be spaced more widely apart, perhaps once every three years.

The Committee received a response from the then Minister for Local Government, Housing and Planning which acknowledged the requests for regular reporting and suggestions for time frames, but did not make any commitments and referred to the fact that discussions between framework parties were ongoing. A finalised version of the framework, which this briefing discusses, was published on 31 August 2021.

Scrutiny at other legislatures

This section provides information on scrutiny of the framework at other legislatures.

The framework was considered by the Northern Ireland Assembly Committee for Infrastructure, the Welsh Senedd Climate Change, Environment and Rural Affairs Committee, the House of Commons Levelling Up, Housing and Communities Committee, and the House of Lords Common Frameworks Scrutiny Committee.

House of Lords Common Frameworks Scrutiny Committee

The House of Lords Common Framework Scrutiny Committee began its consideration of the provisional framework on 24 November 2020. On 10 December 2020, in correspondence to the Minister of State for Housing, Christopher Pincher MP, the Committee noted:

We are concerned by the lack of planned external scrutiny of the ongoing functioning of the framework. The Provisional Framework suggests a review after two years of operation and states that the “the involvement of other stakeholders would be considered at the time.” We think this is insufficient and does not ensure an appropriate degree of transparency for the rules governing hazardous substances in the planning system. We recommend that the review should actively solicit input from a wide variety of stakeholders, including non-industry stakeholders, and that a report from this review should be published and shared with the UK Parliament and devolved legislatures, in order to facilitate future parliamentary scrutiny.

House of Commons Housing, Communities and Local Government Committee

The House of Commons Housing, Communities and Local Government Committee was responsible for considering the provisional framework in the House of Commons. The Committee held an inquiry to assist with scrutiny of the provisional framework and issued a call for evidence which ran from 1 December 2020 to 14 December 2020. On 17 December 2020, in correspondence to the Minister of State for Housing Christopher Pincher MP, the Committee raised the following concerns on regulatory consistency:

You state in the cover sheet that the framework is non-contentious, and this was borne out in the evidence we received to our inquiry, including in liaison with our counterpart committees. We note evidence from the Health and Safety Executivei that states that "regulatory consistency across the four nations is not always necessary, primarily because of local needs, however significant divergence may provide some difficulties for HSE, both operationally and in terms of ensuring the UK meets its International commitments." The Committee believes, to avoid an adverse impact on the efficiency of HSE's role as statutory consultee, that the framework should include provision whereby, in the event of any proposed legislative divergence, MHCLGii and the devolved administrations engage with HSE, at an early stage to manage the impact of any proposed changes.

The Committee also indicated its agreement with the House of Lords Common Frameworks Scrutiny Committee on the lack of provision for external scrutiny in the provisional framework:

We also note the concern expressed by the House of Lords Common Frameworks Scrutiny Committee about the lack of planned external scrutiny during any review of the procedure for common frameworks. Like the Lords committee, we recommend that the government commit to seeking evidence from stakeholders, including non-industry stakeholders, during the review process and that the report from the review be published and laid before the UK parliament and devolved legislatures.

Northern Ireland Assembly Committee for Infrastructure

The Northern Ireland Assembly Committee for Infrastructure was responsible for considering the provisional framework. The Committee held an oral evidence session on 3 February 2021 with Officials from the Northern Ireland Department for Infrastructure. Committee Chairperson Michelle McIlveen MLA raised the issue of stakeholder engagement within the framework during this evidence session:

The House of Lords Committee has advised that it welcomes several parts of the framework but has a number of concerns. The Committee makes two recommendations that, it believes, would facilitate future stakeholder engagement and parliamentary scrutiny of the framework. It recommends that the review should actively solicit input from a wide variety of stakeholders, including non-industry stakeholders, and that a report from the review should be published and shared with the UK Parliament and devolved legislatures in order to facilitate future parliamentary scrutiny.

Welsh Senedd Climate Change, Environment and Rural Affairs Committee

The Senedd's Climate Change, Environment and Rural Affairs Committee considered the matter of stakeholder engagement as part of the development of the provisional framework and the provisions for ongoing stakeholder engagement when the framework became operational. In correspondence dated 21 January 2021 to the Minister for Housing and Local Government, Julie James MS, the committee noted:

In your letter, dated 17 November 2020, you told us that, “given the limited consequences of the framework proposals, engagement with stakeholders has been similarly limited”. We acknowledge hazardous substances planning is a specialised topic, and the framework proposals themselves do not represent a change in policy. However, we believe more could have been done to engage with a wider range of stakeholders, including environmental groups. We note that, although engagement with key stakeholders took place in March 2019, you have only recently shared details of the draft Framework with other interested parties in Wales. We are disappointed you did not seek to engage these parties at an earlier stage of the Framework development.

The committee also made two recommendations for stakeholder engagement within the framework as part of the monitoring and review arrangements:

We recommend the draft Framework be amended to include an expectation for stakeholder involvement in the review process, while acknowledging the need for a proportionate approach to engagement.

We recommend the draft Framework be amended to include suitable arrangements to facilitate parliamentary scrutiny as part of the review process. As a minimum, the UK administrations should notify parliaments of any review of the Framework, and report on the outcome of any such review.

The UK Internal Market Act 2020

The UK Internal Market Act 2020 was introduced in the UK Parliament by the UK Government in preparation for the UK’s exit from the EU. The Act establishes two market access principles to protect the flow of goods and services in the UK’s internal market.

The principle of mutual recognition, which means that goods and services which can be sold lawfully in one nation of the UK can be sold in any other nation of the UK.

The principle of non-discrimination, which means authorities across the UK cannot discriminate against goods and service providers from another part of the UK.

The Act means that the market access principles apply even where divergence may have been agreed in a framework.

The introduction of the UK Internal Market Act had a significant impact on the common frameworks programme because of the tension between the market access principles contained in the Act and the political agreement reached that “common frameworks would be developed in respect of a range of factors, including "ensuring the functioning of the UK internal market, while acknowledging policy divergence"."i

UK Government Ministers have the power to disapply the market access principles set out in the Act where the UK Government has agreed with one or more of the devolved governments that divergence is acceptable through the common frameworks process.

Although UK Ministers can disapply the market access principles in such circumstances, they are not legally obliged to do so.

On 2 December 2021, Angus Robertson MSP, Cabinet Secretary for Constitution, External Affairs and Culture wrote to the Convener of the Constitution, Europe, External Affairs and Culture Committee to give an update on the common frameworks programme.

The letter indicated that at a recent Ministerial quadrilateral, agreement had been reached between the UK Government and the Scottish Government and other devolved administrationsii on an approach to "securing exemptions to the Act for policy divergence agreed through common frameworks".

The meeting agreed an approach to securing exemptions to the Act for policy divergence agreed through common frameworks, and endorsed the text of a statement that UK Ministers will shortly make to the House of Commons. This will give effect to firm commitments made to the UK Parliament during the passage of the Bill that “…divergence may occur where there is agreement under a common framework, and that such divergence could be excluded from the market access principles. Regulations to give effect to such an agreement can be made under Clauses 10 and 17. In those cases, the Secretary of State would be able to bring to the House a statutory instrument to exclude from the market access principles a specific agreed area of divergence.

This would follow consensus being reached between the UK Government and all the relevant parties that this is appropriate in respect of any specific defined topic within a common framework.

Letter from the Cabinet Secretary for Constitution, External Affairs and Culture, 2 December 2021

Process for considering UK Internal Market Act exclusions in common framework areas

The UK Government and devolved administrations have agreed a process for considering exclusions to the market access principles of the UK Internal Market Act 2020. The process was published on 10 December 2021.

The process requires that if a party to the framework wishes to seek an exclusion to the market access principles, it must set out the scope and rationale for this. The proposed exclusion is then considered by the appropriate framework forum, taking into account evidence including about the likely direct and indirect economic impact of the proposed exemption. If the exemption is agreed, it is for UK Ministers to introduce a draft instrument to the UK Parliament to give effect to the exclusion. The UK Parliament will then consider the draft instrument.

The process is set out in full below.

Proposal and consideration of exclusions

1. Sections 10 and 18 and Schedules 1 and 2 of the UK Internal Market Act contain provisions excluding the application of the United Kingdom market access principles in certain cases.

2. Whenever any party is proposing an amendment to those Schedules in areas covered by a Common Framework:

a. the exclusion seeking party should set out the scope and rationale for the proposed exclusion; and

b. consideration of the proposal, associated evidence and potential impact should be taken forward consistent with the established processes as set out in the relevant Common Framework, including an assessment of direct and indirect economic impacts.

3. It is recognised that all parties will have their own processes for considering policy proposals. Administrations should consult and seek agreement internally on their position before seeking to formally agree the position within the relevant Common Frameworks forum.

Agreement of an exclusion request

4. Where policy divergence has been agreed through a Common Framework this should be confirmed in the relevant Common Framework forum. This includes any agreement to create or amend an exclusion to the UKIM Act 2020’s market access principles.

5. Evidence of the final position of each party regarding any exclusion and whether an agreement has been reached should be recorded in all cases. This could take the form of an exchange of letters between appropriate UK Government and Devolved Administration ministers and include confirmation of the mandated consent period for Devolved Administration ministers regarding changes to exclusions within the Act.

6. Parties remain able to engage the dispute resolution mechanism within the appropriate Common Framework if desired.

Finalising an exclusion

7. Under section 10 or section 18 of the UK Internal Market Act 2020 amendments to the schedules containing exclusions from the application of the market access principles require the approval of both Houses of the UK Parliament through the affirmative resolution procedure. Where agreement to such an exclusion is reached within a Common Framework, the Secretary of State for the UK Government department named in the Framework is responsible for ensuring that a draft statutory instrument is put before the UK Parliament.

1

Hazardous Substances (Planning) Common Framework

The Hazardous Substances (Planning) Common Framework ("the framework") reached phase four during the course of the session five Parliament and was considered by the Local Government and Communities Committee.

Policy Area

The framework relates to elements of the Seveso III Directive (2012/18/ EU) ("the Directive"). The Directive is concerned with the control of major accident hazards involving dangerous substances. The Directive became domestic law in the UK as EU retained law.

The Directive aims to prevent major accidents and, where such accidents do occur, limit their consequences. To that end, the Directive specifies named substances such as ammonium nitrate, generic categories of substance (e.g. flammable gases) and controlled quantities. Where these named substances are present at or above the controlled quantities, the Directive sets certain rules.

The Directive falls into two distinct areas:

On-site rules - the measures put in place, for example by businesses, to prevent accidents from happening and to minimise the risks and impact if they do occur.

Residual off-site risk - the risk of a major accident arising and hurting people or the environment because of the proximity of hazardous substances to other developments or sensitive environments.

The framework relates only to the land-use planning elements of the Directive. This means the requirements which are in place to manage the residual off-site risk, including:

planning controls on the presence of hazardous substances (i.e. setting limits on the amount of dangerous substances that can be stored and/or used before an application for consent to do so must has to be made)

the handling of development proposals for places where hazardous substances are present (i.e. ensuring planning policies take into account the aims and objectives of the Directive)

the handling of development proposals in the vicinity of places where hazardous substances are present (i.e. obliges local planning authorities to comply with various consultation requirements, consider any major accident hazard issues and hazardous substances consent before granting planning permissioni.)

Land-use planning is devolved in Scotland with local authorities responsible for planning decisions in their area.

The Health and Safety Executive (HSE) and Health and Safety Executive Northern Ireland (HSE NI) are government agencies responsible for the encouragement, regulation and enforcement of health and safety.

Scope

The framework sets out the scope as any legislation which applies the land-use planning elements of the retained Seveso III Directive in the UK.i The following ‘operability’ regulations have been made to ensure that the regime continues to function appropriately following the UK's exit from the EU :

The Planning (Hazardous Substances and Miscellaneous Amendments) (EU Exit) Regulations 2018.

The Planning (Environmental Assessments and Miscellaneous Amendments) (EU Exit) (Northern Ireland) Regulations 2018

The Town and Country Planning (Miscellaneous Amendments) (Wales) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019

The Town and Country Planning and Electricity Works (EU Exit) (Scotland) (Miscellaneous Amendments) Regulations 2019

The Planning (Environmental Assessments and Technical Miscellaneous Amendments) (EU Exit) Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2020

The framework notes that these regulations are 'fully independent of the framework'. Given how other, more recent frameworks are drafted, it appears likely that this formulation means that no new legislation is required to implement or is created by this framework.

The framework also mentions the following pieces of legislation of domestic origin:

In England:

The Planning (Hazardous Substances) Act 1990

The Planning (Hazardous Substances) Regulations 2015

The Town and Country Planning (Development Management Procedure) (England) Order 2015

In Scotland:

Planning (Hazardous Substances) (Scotland) Act 1997

The Town and Country Planning (Hazardous Substances) (Scotland) Regulations 2015

The Town and Country Planning (Development Management Procedure) (Scotland) Regulations 2013

In Wales:

The Planning (Hazardous Substances) Act 1990

The Planning (Hazardous Substances) (Wales) Regulations 2015

The Town and Country Planning (Development Management Procedure) (Wales) Order 2012

In Northern Ireland:

The Planning Act (Northern Ireland) 2011

The Planning (Hazardous Substances) (No.2) Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2015

The Planning (General Development Procedure) Order (Northern Ireland) 2015

The framework notes that whilst the different administrations are able to use their devolved planning powers to increase controls beyond the minimum requirements of the Directive, this has not happened in any substantive way.

The framework notes two areas of policy which, although closely linked to the framework, do not come within its scope. These are:

The Control of Major Accident Hazards (COMAH)

This is an existing Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between the devolved administrations and the various bodies that make up the COMAH Competent Authority (see section on roles and responsibilities below). This MoU relates to elements of the Directive which are about on-site measures. This MoU is being updated but is not part of the Hazardous Substances (Planning) framework. It will, however, operate alongside it.

Hazardous substances consent process

The purpose of hazardous substances consent is to ensure that residual risk to people in the vicinity or to the environment is taken into account before a hazardous substance is allowed to be present in a controlled quantity. The hazardous substances consent process sits outside the development consent process (i.e. the consideration of planning permission). Planning authorities have to consult HSE or HSE NI if a planning development is in a consultation zone.ii

International agreements

The framework sets out the following relevant international agreements that the UK will remain party to:

During an evidence session on the framework held by the Local Government and Communities Committee on 16 December 2020, a Scottish Government Official outlined how the above international agreements will restrict the scope of the framework:

That [International agreements] cements many of the requirements of the current regime that operates in international law. Any stripping back of the hazardous substances regime would result in a breach of those international obligations. That limits what the UK, as a party to the conventions, could do, but it also constrains the devolved Administrations, of course. It is right that we have signed up to all those treaties, and that we have stringent regulations in place. We must and will, by means of the framework, ensure that we continue to meet those international obligations.

Summary of proposed approach

The framework states that a non-legislative framework is appropriate. During an evidence session on the framework held by the Local Government and Communities Committee on 16 December 2020, a Scottish Government official gave the following justification for not pursuing a legislative basis for the framework:

[...] there was early consideration of whether a legislative underpinning was necessary for each of the frameworks. For the hazardous substances framework, it was decided that that was unnecessary because it is, essentially, a continuation of the current arrangements. It was therefore considered not to be necessary to have a legislative framework, because what was required would be possible through a common framework.

The framework further details why the hazardous substances planning framework is necessary in relation to the key priorities listed by the JMC(EN) for establishing common frameworks. These are set out in the table below. The text in the table are excerpts taken directly from the common framework.

| JMC(EN) priorities for establishing common frameworks | Common framework description |

|---|---|

| To enable the functioning of the UK internal market, while acknowledging policy divergence: | As stated in section 1 [see 'policy area' section in this briefing], establishments which store certain amounts of certain substances or developers looking to build near such establishments will be required to seek consent from a local authority. The regime is not focused on banning activities or making a substance illegal in a general sense.As a result, (and in a scenario in which the non- regression principle did not apply) the biggest potential discrepancy would be where, for example, one administration removed controls for a certain substance completely, where across the border, operators would need to go through the hazardous substances consenting process with their local authority to hold the substances at a site in the same quantities. However, due to the nature of the regime this would bring very limited economic benefits – relaxed hazardous substances standards would not bring a significant enough benefit to operators to influence which administration they set up business in to the point where this would distort the internal market. |

| To ensure compliance with international obligations | The UK is a signatory to two international agreements relevant to the hazardous substances planning regime (as mentioned in section 2) [see section on 'scope' in this briefing], the Aarhus Convention and the Convention on the Transboundary Effects of Industrial Accidents. The latter in particular cements many of the requirements of the current regime in international law, therefore any significant stripping back of the hazardous substances planning regime could result in a breach of international obligations.This presents limits on what the UK Government can do as the party to the treaties, but also constrains the devolved governments. In very extreme cases the Secretary of State has step-in powers already built into devolution settlements where there is a potential breach of international law, although the UK Government do not envisage these forming any part of the framework agreement. A non-legislative framework agreement would provide the appropriate forum for any policy changes to be addressed, where anything of concern can be flagged and any necessary dispute resolution measures (see section 13) [see the 'dispute resolution' section in this briefing] can be put in place.In the event that either of the two relevant international agreements are amended, UK Government will decide whether the amendments should be ratified. Before ratifying any international agreement, the devolved governments must be consulted. If the legislation of one or more administrations needs to be brought into line with the requirements of any new amendments, then this must be finalised before any amendment can be ratified. Where necessary, any disagreements should be resolved through the dispute resolution mechanism as set out in the framework. |

| To enable the management of common resources | HSE/HSE NI operate across the different planning jurisdictions (HSE NI covering Northern Ireland), and so any divergence could affect them, and so any framework agreement encouraging and providing a forum for discussion would be beneficial. However, potential changes to the regime with significant impacts on HSE/HSE NI are already a potential feature of the existing regime within the EU framework and are not triggered by EU exit. There is not a new significant issue being created on this point that would need to be addressed by legislative means. |

| To safeguard the security of the UK | Differing hazardous substances planning controls in parts of the UK are already a possibility, i.e. not affected by EU Exit, and these differences do not pose a threat to UK security.Reducing protections below current levels could become possible, which could increase the risk to safety within an area (acknowledging the limited risk of cross-border impacts) e.g. by allowing hazardous substances near a sensitive development (to note, safety measures within establishments would still be regulated through non-planning requirements under the Control of Major Accidents Hazards Regulations 2015 or their equivalent). As stated previously, hazardous substances powers are broadly analogous to other devolved planning powers in this regard and as such should be seen as a matter for individual administrations – divergence in and of itself does not pose a risk to the security of the UK as a whole.According to the JMC(EN) principles, a legislative framework agreement should be considered only where absolutely necessary. As set out above, a potential legislative framework for hazardous substances would not meet these criteria. According to the principles set out by JMC(EN) and the objective of securing the proper functioning of the hazardous substances planning regime whilst at the same time respecting the devolution settlements, this common framework will not be a legislative vehicle but rather a reflection of the discussions that have taken place and agreements reached on ways of working going forward, post the UK's departure from the European Union. |

The framework lists the following additional considerations:

the devolved regimes predate the current version of the Directive, and in certain cases go further than its minimum requirements; the framework argues that this demonstrates the lack of appetite to legislate below its minimum standards.

the HSE/HSE NI have a cross-cutting role which provides a common evidence base which all parties look to; with policy development across all four administrations informed by HSE/HSE NI advice, the framework concludes that differing approaches would be unlikely.

The framework also states the following on the current potential for divergence:

Planning authorities and Ministers in the various home nations are free to make decisions on applications as they see fit, provided major accident hazard potential forms part of the consideration. Although decision-making is devolved, which provides the scope for divergence, very little has occurred. In light of past practice, this framework agreement is sufficient to manage divergence.

Stakeholder engagement

The framework documents do not provide detail on specific stakeholder engagement. The text briefly refers to industry views. For example, page 9 of the framework states the following:

Industry stakeholders have been clear that the current processes play an important role in enshrining vital safeguards against major accidents. As such, reducing standards in this way is not something that industry has been pushing for or is likely to pursue and the proposed approach is considered appropriate.

However, no detail is provided on specific industry stakeholders that were consulted.

During an evidence session on the framework held by the Local Government and Communities Committee on 16 December 2020, a Scottish Government Official stated the following:

There has been a series of engagements, and the framework has gone through a number of stages including, in March 2019, a technical round-table meeting with stakeholders to check that they were all content and, in August 2019 and January 2020, review and assessment panels involving officials from the four Administrations. We have been feeding into the framework process through the planning area of the Government.

The Official further noted:

Throughout the stakeholder engagement on whether there was scope for divergence, no concerns were expressed by Administrations or stakeholders—from the industry and local authority sides—to the effect that there was appetite for change and, therefore, scope for divergence. That has been the only conclusion, as it has been confirmed throughout engagement that that is the situation.

The issue of ongoing stakeholder engagement within the framework was raised during the consideration of the provisional agreement at each of the four UK legislatures.

The finalised framework makes provisions for engagement with relevant legislatures and stakeholders in the Review and Amendment process.

Detailed overview of proposed framework: legislation

The framework states that no new primary legislation is required to implement the framework.

Detailed overview of proposed framework: non-legislative arrangements

The framework is is implemented through a non-legislative agreement that sets out how governments across the UK propose to work together on the policy area in scope of the framework. However, in contrast to more recently published frameworks, this framework does not comprise a Concordat or Memorandum of Understanding and instead appears to be wholly made up of what in other frameworks is called a 'Framework Outline Agreement'. It lists a set of nine principles the UK Government and the devolved governments have agreed for future ways of working that would make up the agreement:

Hazardous Substances planning framework principles for future ways of working:

i. In the absence of EU requirements applying to the UK, the nations of the UK will consider appropriate evidence and expert advice (for example that of the Control of Major Accidents Hazards (COMAH) competent authority and industry bodies), as appropriate, as regards the substances and quantities to which hazardous substances consent should apply .

ii. Administrations will respect the ability of other administrations to make decisions (i.e. allowing for policy divergence).

iii. Administrations will consider the impact of decisions on other administrations, including any impacts on cross-cutting issues such as the UK Internal Market.

iv. Wherever it is considered reasonably possible, administrations agree to seek to inform other administrations of prospective changes in policy one month, or as close to one month as is practical, before making them public.

v. Administrations will ensure an appropriate level of public transparency in decision making that leads to policy changes.

vi. Parties will create the right conditions for collaboration, by for example ensuring policy leads attend future meetings.

vii. Future collaborative meetings will be conducted at official level and on a without prejudice basis.

viii. In order to broaden the debate at future collaborative meetings, parties will ensure that different perspectives are present.

ix. Those attending future collaborative meetings recognise the importance of how collaboration is approached.

Hazardous Substances: planning framework in practice

Decision-making

The framework documents set out the intention to establish a working group of policy leads in each administration and hold six-monthly telephone conferences to share information, learning and provide a forum to discuss wider policy issues. They state that the initial meeting will be arranged and chaired by UK Government, with arrangements for further meetings discussed as an agenda item. The meetings will aim to discuss:

any post-exit policies that have been implemented at either the UK or devolved level;

how successful they have been, and;

whether there had been any unexpected impacts.

The framework documents further explain the role of the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) and Ministers:

Usually, HSE acts as the coordinator for implementing new requirements from revision of, or amendments to the Directive and engages with planning representatives from the various administrations to coordinate implementation. They may play a similar role in future but will have no explicit responsibility to do so. As other issues arise, contact is made, again on an ad hoc basis, to seek to resolve these. Ministers responsible for planning individually sign off implementing legislation or changes to procedures.

The framework agreement commits to take account of any future arrangements for the functioning of the UK Internal Market, but notes that the Hazardous Substances (Planning) Common Framework is considered non-market as it focuses on Health and Safety. It also assesses that the framework does not have a strong interaction with any relevant market considerations.

Roles and Responsibilities: parties to the framework

The roles and responsibilities of the parties to the framework are set out in the section on non-legislative arrangements above.

Roles and responsibilities: existing or new bodies

This section sets out the roles and responsibilities of any bodies associated with the framework which already exist, or which are to be created.

The Framework sets out the following competent authorities.

In Great Britain: the COMAH competent authority (CA) is made up of the relevant safety body (HSE or the Office for Nuclear Regulation (ONR) at nuclear establishments), acting jointly with the appropriate environment agency for the locality, i.e. the Environment Agency in England, the Scottish Environment Protection Agency in Scotland, and Natural Resources Wales.

In Northern Ireland: the CA is HSE NI and the Northern Ireland Environment Agency of the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs. The CA determines the nature and severity of the risks to the environment and people in the surrounding area from the hazardous 13 substances in the application and advises the Hazardous Substances Authority on whether they should grant consent. They also have responsibility for advising on any changes to the lists of controlled substances and other policy updates that may impact the hazardous substances planning regime. In relation to planning applications, HSE NI is a statutory consultee and provides advice to planning authorities in Northern Ireland.

The framework further sets out the role of the Health and Safety Executive:

HSE have the lead on the Seveso III Directive in Great Britain, and post-Exit will be taking up several of the functions that currently sit with the European Commission in relation to COMAH, this will include the responsibility for advising on any changes to the lists of controlled substances or other policy updates that may impact the hazardous substances planning regime. Changes in their policy, e.g. on risk or the way they engage in the planning system ultimately rest with the UK Secretary of State for Work and Pensions. Beyond this proximity to the regime, and as a potential source of advice, neither HSE/HSE NI or the CA have any official role within the structure of this framework agreement.

They will continue in their current role and with their current responsibilities following the UK’s Exit from the EU and have been kept informed throughout the process of developing this framework agreement.

Monitoring and enforcement

The framework states the following on monitoring and enforcement:

As no legislative arrangements are considered necessary then enforcement measures are not appropriate. In place of formal monitoring measures there will be regular meetings to review the framework agreement (see sections 8 and 12 [see sections decision making and review and amendment sections in this briefing]). Policy officials acknowledge that there are likely to be ongoing reporting requirements associated with being part of the frameworks work programme and will cooperate with all relevant requests and commissions.

Review and amendment

The framework states that a review meeting between UK Government and devolved governments will be held one year after the day the framework agreement comes into effect. Assuming the framework has been in effect since its date of publication, the review meeting will be held on 31 August 2022. The review is intended to consider the "ongoing application of transposing domestic legislation across the different administrations".

The framework provides further details on the review meeting:

The meeting would focus in particular on any issues encountered and allow parties to provide a forward look of any changes that they are considering. The review will also involve engagement with relevant legislature committees and other stakeholders, as considered proportionate, including appropriate competent authorities, local authorities, industry and environmental groups.

The framework also sets out the process for initiating early reviews:

If any party to this framework agreement feels an early review is necessary, then a request can be made at official level. It is expected that such requests also be resolved at official level, and that such requests be accommodated unless there is a valid reason for refusal. Timeframes can be discussed on a case-by-case basis, but unnecessary delay should be avoided. If an agreement cannot be reached, then the dispute resolution procedure set out in section 13 [see the dispute resolution at official level sections of this briefing] will apply.

The framework also sets out that after an initial review a more permanent arrangement for recurring meetings involving UK Government and devolved governments on the framework agreement will be decided.

Dispute resolution official level

This section considers the dispute resolution process set out within the framework. The framework agreement sets out the intention that there will be a regular group at working level to discuss and work through any issues at an early stage. It further states:

The intention is for this process to remain flexible and adaptable to individual situations, and this precludes us from affixing timescales to each stage. However, resolving issues as quickly as possible will be a key priority and escalation will always be seen as a last resort.

The framework sets out the following dispute resolution process:

Hazardous Substances planning framework dispute resolution process.

Policy leads: Where officials become aware of potential issues or areas of disagreement via any means the first step will be to seek to resolve this amongst policy leads without escalation. This will usually be resolved via discussion with equivalents in other administrations to determine the source of the disagreement, to establish whether it is a material concern and to work through possible solutions to the satisfaction of all parties. It is expected that most disagreements would be resolved at this point.

Director level/Chiefs of planning: Where disagreements cannot be resolved amongst policy leads the next stage will usually be to escalate the issue to director level. At this stage directors can decide whether it would be appropriate to arrange a meeting with counterparts across administrations. Alternatively, or after such a meeting, directors may determine that the issue cannot be resolved at this stage at which point the involvement of Ministers will be required.

Portfolio Ministers: This is expected to be a last resort for only the most serious issues and where all alternatives have been exhausted. In very extreme cases the Secretary of State has step-in powers, already built into Devolution settlements, although the framework states it does not envisage these forming any part of the framework agreement.

HSE/HSE NI: They may be included at multiple stages of the process, potentially flagging issues, or providing advice on possible solutions.

Agree to disagree: The framework states that it does not always follow that where disagreements emerge these will need to be escalated or a ‘solution’ need to be established. The framework agreement will not prejudice the right of administrations to ‘agree to disagree’ in certain circumstances.

Dispute resolution Ministerial level

It is anticipated that recourse to resolution at Ministerial level will be as a last resort and only sought where dispute resolution at official level has failed. Disputes which reach Ministerial level will be resolved through intergovernmental dispute resolution mechanisms. Relevant intergovernmental disputes may concern the "interpretation of, or actions taken in relation to, matters governed by […] common framework agreements".

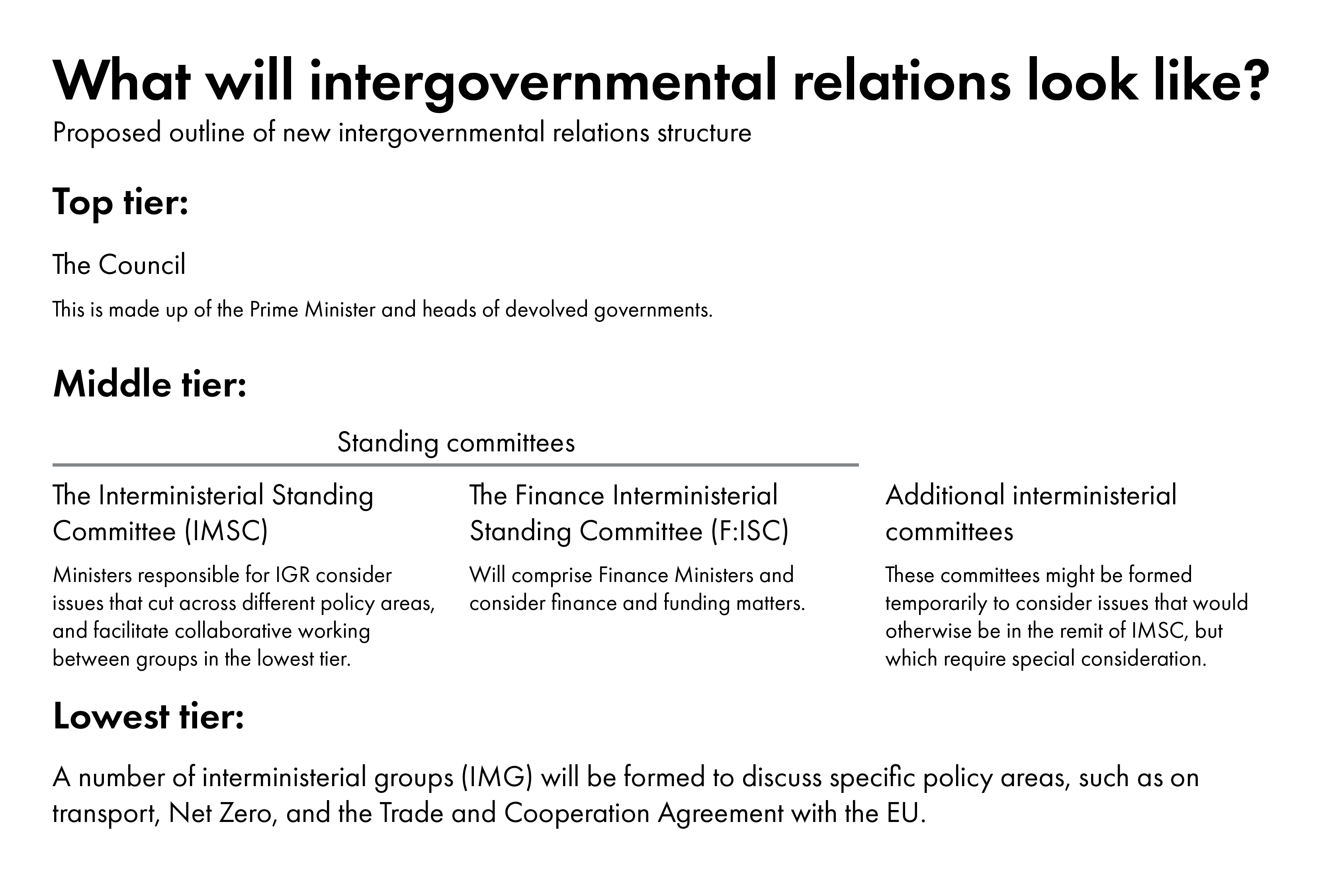

Intergovernmental dispute resolution mechanisms were considered as part of the joint review on intergovernmental relations. The conclusions of the joint review were published on 13 January 2022 and set out a new approach to intergovernmental relations, which the UK Government and devolved governments have agreed to work to. The joint review created a new three-tiered system for intergovernmental discussions, doing away with the old Joint Ministerial Committee structure.

The lowest and middle tiers have specific responsibilities for common frameworks. At the lowest tier, interministerial groups (IMGs) are responsible for particular policy areas, including common frameworks falling within them. At the middle-tier, the Interministerial Standing Committee (IMSC) is intended to provide oversight of the common frameworks programme.

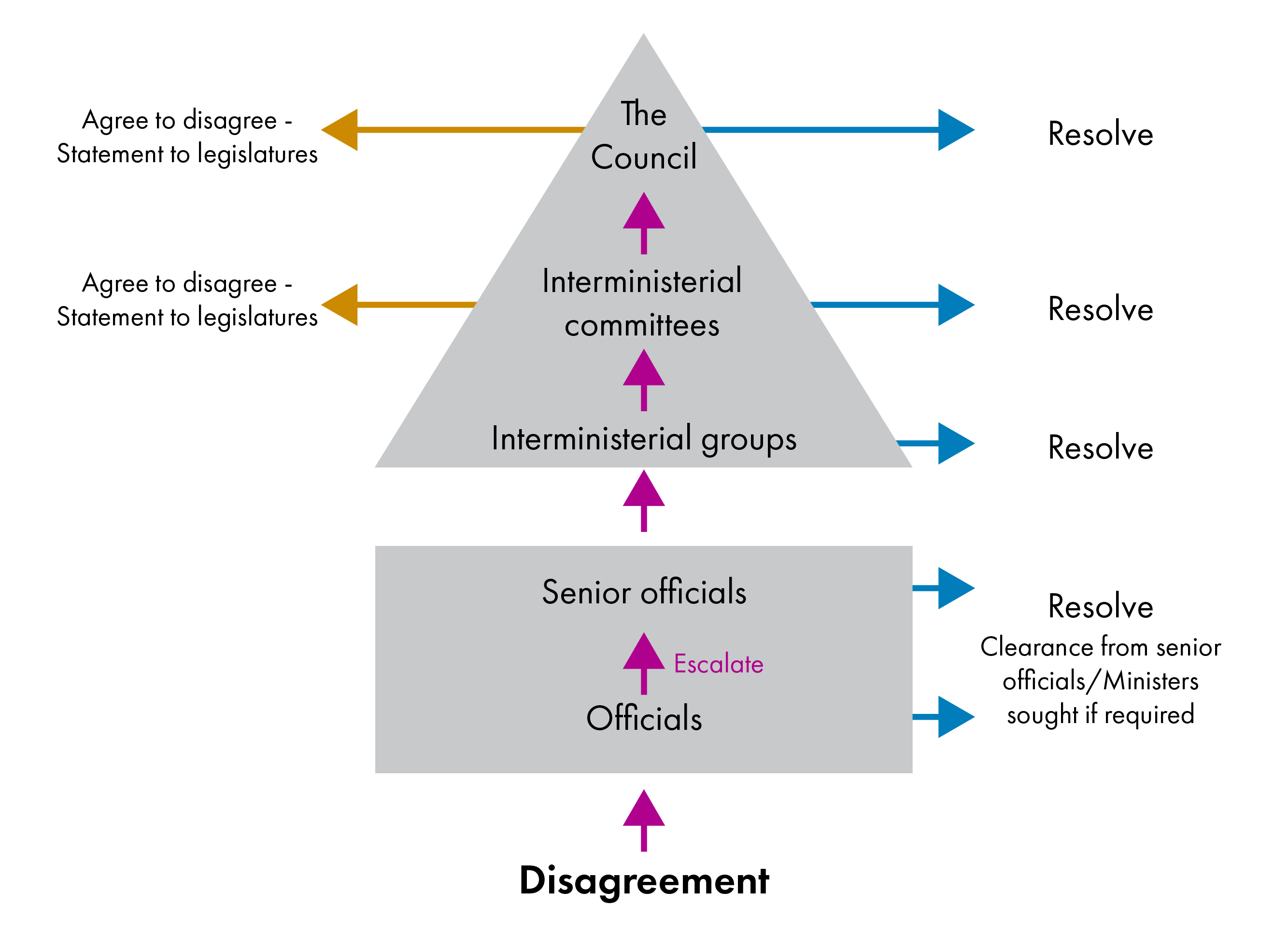

The new IGR dispute resolution process follows on from the process at the official level. If a dispute cannot be resolved at the official level as set out in individual frameworks, it is escalated to the Ministerial level. The diagram below illustrates the general dispute resolution process for frameworks, including discussions between officials (square) and Ministers (triangle).i

At the lowest level, interministerial groups comprising portfolio Ministers attempt to resolve the disagreement. If their attempts are unsuccessful, the issue can be escalated to an interministerial committee. If the interministerial committee is unsuccessful in resolving the issue, it can either agree to disagree, in which case each government makes a statement to their legislature to or escalate the dispute further. If a dispute is escalated to the highest level, third-party advice or mediation should normally be sought and made available to the Council. If the Council fails to find agreement, it is again required to make a statement to their legislatures.

The new process includes more extensive reporting requirements about disputes. The IGR secretariat is required to report on the outcome of disputes at the final escalation stage, including on any third-party advice received. Each government is also required to lay this report before its legislature.

The Office for the Internal Market (OIM) can provide expert, independent advice to the UK Government and devolved governments. Its advice and reports may, however, be used by governments as evidence during a dispute on a common framework.

Rachel Merelie of the OIM explained the position whilst giving evidence to the House of Lords Common Frameworks Scrutiny Committee in November 2021:

The OIM is not involved in dispute resolution. We are here to provide advice to government, using our economic and technical expertise…It is of course possible…that our reports are considered in some shape or form as evidence in support of that process, and we remain open to being used in that way.