Judicial Review

Judicial review is an important type of court action in which a judge assesses the lawfulness of a decision or action by a public body. This briefing provides an introduction to judicial review in Scotland.

Executive Summary

Judicial review is the court process by which a judge reviews a decision, an action or a failure to act by a public body or other decision maker. Judicial review is only available where other effective remedies have been exhausted and where there is a legally recognised ground of challenge.

There have been recent, high-profile judicial review cases associated with the UK's departure from the European Union ('Brexit'), as well as cases associated with the UK and Scottish governments' public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic. These cases have raised the public profile of judicial review as a form of legal challenge to official decision making.

Who can bring an action for judicial review?

The rules on standing determine who may bring an action for judicial review. The previous law on standing in Scotland was widely criticised and was changed by the UK Supreme Court in 2011.

The current test requires that the person or body raising an action has sufficient interest to do so. This test is thought to be beneficial to those seeking to represent a public interest, such as the protection of the environment.

Time limits

The Courts Reform (Scotland) Act 2014 introduced a three month time limit in which to bring judicial review proceedings. There is discretion for the courts to depart from this time limit, where 'equitable' (i.e. fair) to do so.

The costs of raising a judicial review action

Someone raising a judicial review action can be exposed to considerable financial risk. Depending on the circumstances (for example, whether legal aid is available) cost can act as a barrier to using judicial review in an individual case.

Developments in the law relating to judicial review

There have been some significant developments in the nature of judicial review since the introduction of the current judicial review procedure in Scotland in 1985.

Some of these developments created new grounds of judicial review. They have opened up the possibility of challenge to legislation by way of judicial review to a much greater extent than was the case previously.

The legality of decision making, not its substance

However, despite recent developments, judicial review remains primarily concerned with the process or legality of official decision making. For the most part, judicial review is not focused on the merits of the decisions themselves.

An action for judicial review is not equivalent to a statutory right of appeal, which may involve examination of the merits of a decision. Even after a successful action for judicial review, the decision maker may be able to make the same decision again, so long as it does so in a lawful way and following the correct process.

Overall, judicial review should be seen as part of a wider system for addressing grievances in relation to official decision making.

Introduction and background

This introductory section explains:

Why judicial review matters

Every day, official decisions are taken that affect the lives of individuals and which have an impact on businesses and other organisations. As one leading textbook notes, it is important for a free society that decision makers can be held to account for their decisions.1 Judicial review is one mechanism that aims to provide that accountability.

Judicial review is traditionally the remedy of last resort. Individuals and organisations applying for judicial review can also face significant challenges, financial and otherwise. However, in the right set of circumstances, judicial review is also one of the most high-profile and effective types of legal action that can be brought in Scotland.2

A key point is that judicial review doesn't just enable some administrative decisions to be challenged and set aside. It also has the wider effect of encouraging more careful decision making in the first place,3 because of the knowledge that decisions may later be tested in court.1

What this briefing covers

The overview section of this briefing provides a summary of the topic of judicial review as a whole. This section is intended as a useful introduction to the subject, and it can be read as a stand-alone briefing.

The next section of the briefing looks in more detail at judicial review in practice. It considers what we know from the published statistics and summarises some of the key cases that have recently made media headlines.

The briefing goes on to consider important constitutional developments relating to judicial review, with sections looking at:

Later sections of the briefing explore important practical topics in greater detail than the overview at the start of the briefing provides. For example, there are sections on:

The final sections of the briefing look at:

judicial review as part of a wider system for addressing grievances

various recent and current policy initiatives relevant to judicial review, not otherwise covered in earlier sections of the briefing.

An overview of judicial review in Scotland

This section provides an introductory overview to judicial review in Scotland.

Which court?

A court action for judicial review in Scotland can only be raised in the Outer House of the Court of Session in Edinburgh.

A decision of the Outer House can be appealed (reclaimed) to the Court of Session's Inner House. A decision of the Inner House can, in turn, be appealed to the UK Supreme Court in London. In some circumstances, appealing against a decision requires a court's permission to do so.i

In some limited circumstances, a judicial review case beginning in the Court of Session may be later transferred to the tribunal system. A tribunal is a specialist forum for resolving disputes.

Some key terms

In Scotland, a court action for judicial review is begun using a document known as a petition. The person or body bringing the court action is called a petitioner. The person or body defending the action is called the respondent.

The court may permit interventions in court proceedings by third parties (interveners) who are not litigants in the case. These involve third parties providing written or verbal arguments on key legal issues relating to the case.

How the court decides what to do

When considering a petition for judicial review, the Court of Session will apply the following:

legislation, including the Court of Session Act 1988, as amended by the Courts Reform (Scotland) Act 2014

case law, i.e. the branch of law developed by the decisions of judges in earlier cases

the court rules, which determine how the court proceedings relating to judicial review operate (especially Chapter 58 and Chapter 58A of those rules).

There are some key differences between the law and court procedure associated with judicial review in Scotland, compared to their equivalents in other parts of the UK.

However, there are also aspects of judicial review where the law is virtually identical UK-wide. Consequently, when making decisions, the Scottish courts regularly take into account case law from other parts of the UK.

Public bodies and government ministers

A judicial review action can be raised against a wide range of different public bodies, including, for example:

UK and Scottish government departments and ministers

non-departmental public bodies (NDPBs)

A full list of Scottish public bodies can be found on the Scottish Government’s website.

Just because a body is a public body does not mean that all of its acts and decisions can be subject to judicial review. For example, private contractual disputes between a public sector employer and its employee cannot be judicially reviewed.

Private bodies

A key difference between judicial review in Scotland, compared to judicial review England and Wales, relates to the scope of judicial review.

In Scotland, it is possible, where certain conditions are satisfied, for the acts and omissions of private bodies in Scotland, such as the governing bodies of sporting or trade associations or private clubs, to be the subject of an action for judicial review. In England and Wales, an action for judicial review is only possible in relation to bodies exercising public functions.

Legislation

Legislation of both the UK and Scottish Parliaments can be the subject of an action for judicial review in Scotland. There are two main types of legislation:

primary legislation - Acts of Parliament, the method by which major new laws, or significant changes to existing laws, have traditionally been made

subordinate or secondary legislation ('subordinate legislation' for the remainder of this briefing) - this is the law created by ministers, or other bodies, under powers given to them by an Act of Parliament.

Subordinate legislation has traditionally been used to fill in the details of primary legislation or to bring specific provisions of primary legislation into force. However, more significant policy changes are likely to be included in subordinate legislation after Brexit.

A key point is that subordinate legislation can be reviewed on the full range of judicial review grounds that are available in other circumstances. However, although primary legislation can be subject to judicial review, the opportunities for review are more limited.

The costs of a judicial review action and how to pay for it

A petitioner in a judicial review action can be exposed to considerable financial risk. The costs of using lawyers to present this type of case can be high. Significant court fees, payable directly to the court by the litigants, can be payable.

Crucially, it is also the usual practice for the losing person or organisation in a civil court case to be responsible for paying the winning person's or organisation’s legal expenses in relation to the case, as well as their own.

Depending on the circumstances, legal aid may be available to an individual raising a judicial review action. This has a range of benefits.

Crowdfunding, where a large number of people donate money online to a fundraising cause, appears to be becoming a more common for judicial reviews.1234

Where the petitioner is acting in the public interest, a court may grant a protective expenses order. This shields the petitioner, at least to some extent, from the normal rule relating to the other side's legal expenses.

Some preliminary requirements associated with a judicial review action

Where an effective alternative statutory remedy exists, a person or organisation is required to use it before seeking judicial review,i unless special or exceptional circumstances apply.1

The petitioner usually has three months to lodge an application for judicial review from the date on which the grounds giving rise to the application first arise. However, the court may extend the time limit in an individual case, where equitable ( i.e. fair) , to do so.ii

Under case law, a petition can also be rejected by the court because it is premature or raises a hypothetical or academic issue.

Key stages of a judicial review action

A judicial review action has three main stages in the Outer House of the Court of Session.

First, there is the permission stage, a significant hurdle to clear in practice,1 but not intended to be an 'insurmountable barrier'.2

At this stage, the court must decide that the petitioner has standing. In other words, whether it considers whether the petitioner has a ‘sufficient interest’ in the outcome of the case. The petition must also have a real prospect of success according to one or more of the grounds of review.i

If permission is granted, the court will then look to set dates for two court hearings:

the procedural hearing, if the court considers one is requiredii

the substantive hearing, the main hearing in relation to the case.

The aim of the procedural hearing is to establish that the case is well-prepared and ready to proceed to the substantive hearing.iii

The substantive hearing is set for a date no later than 12 weeks from the date permission was granted, except where the judge is satisfied a longer period is necessary.iv

At the substantive hearing, the court takes an in-depth look at whether one or more of the grounds for judicial review have been established. If so, the court will consider whether the remedy asked for by the petitioner to resolve the case should be granted.

The court may also determine how the parties' legal costs should be divided up between the parties at this stage, although this can be dealt with in a separate hearing.

At the end of the substantive hearing the court may give its decision, for example, if there is a particular urgency associated with the case. Otherwise, a written judgement will follow the substantive hearing, usually within about three months.3

The grounds of review

Traditionally, the grounds of judicial review, a key part of the case, have been divided into three main categories:

the decision maker acted unlawfully (illegality)

the decision was made using an unfair procedure (procedural impropriety or unfairness)

the decision was so unreasonable as to be irrational (irrationality or unreasonableness).

However, the categories are overlapping and the grounds are still evolving. For example, there are now grounds of review associated with breaches of Convention rights. Convention rights are rights protected by the European Convention on Human Rights which have been incorporated into UK domestic law.i They are not affected by the departure of the UK from the European Union.

The Scotland Act 1998 says that an Act of the Scottish Parliament is not law in so far as any of its provisions are outwith the legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament.ii The Act imposes similar restrictions on Scottish subordinate legislation and the activities of the Scottish Government.iii Consequently, the Scotland Act also created additional grounds of challenge.

Legal remedies

If a judicial review action is successful, the court has discretion to decide what legal remedy it should grant to resolve the case. A variety of remedies are possible. Some remedies require a decision maker to take a decision again. However, in keeping with the nature of judicial review, the court will not stipulate what the content of any new decision should be.

An award of financial damages to an aggrieved individual or organisation is only available in limited circumstances.

Judicial review in practice: the statistics and the headlines

This section considers how the law of judicial review is used in practice. It looks at both the official statistics available in Scotland, as well as some recent, high-profile judicial review cases.

A very small part of the courts’ total caseload

Judicial review actions consistently comprise a very small percentage of the total court actions begun in the civil courts in any given year in Scotland.

This is because most civil cases are heard by the local sheriff courts, not the Court of Session.

For example, in 2020-2021, judicial review actions were less than 1% of cases initiated in the civil courts overall (238 judicial review cases out of 43, 632 civil cases).1

However, judicial review cases do represent a significant proportion of the Court of Session's workload. For example, they were around 17% of the cases started there in 2019-20 and around 11% of the cases started there in 2020-21.1

Trends in the judicial review caseload

For a long time after the judicial review procedure was introduced in 1985, there was a steady increase in the judicial review caseload.

For example, there was only an average of around 50 cases initiated a year in the first full five years of the judicial review procedure.1 This compares to an average of:

around 320 cases a year in the five years between 2010-11 and 2014-15

around 390 cases a year in the five years between 2015-16 and 2019-20.2

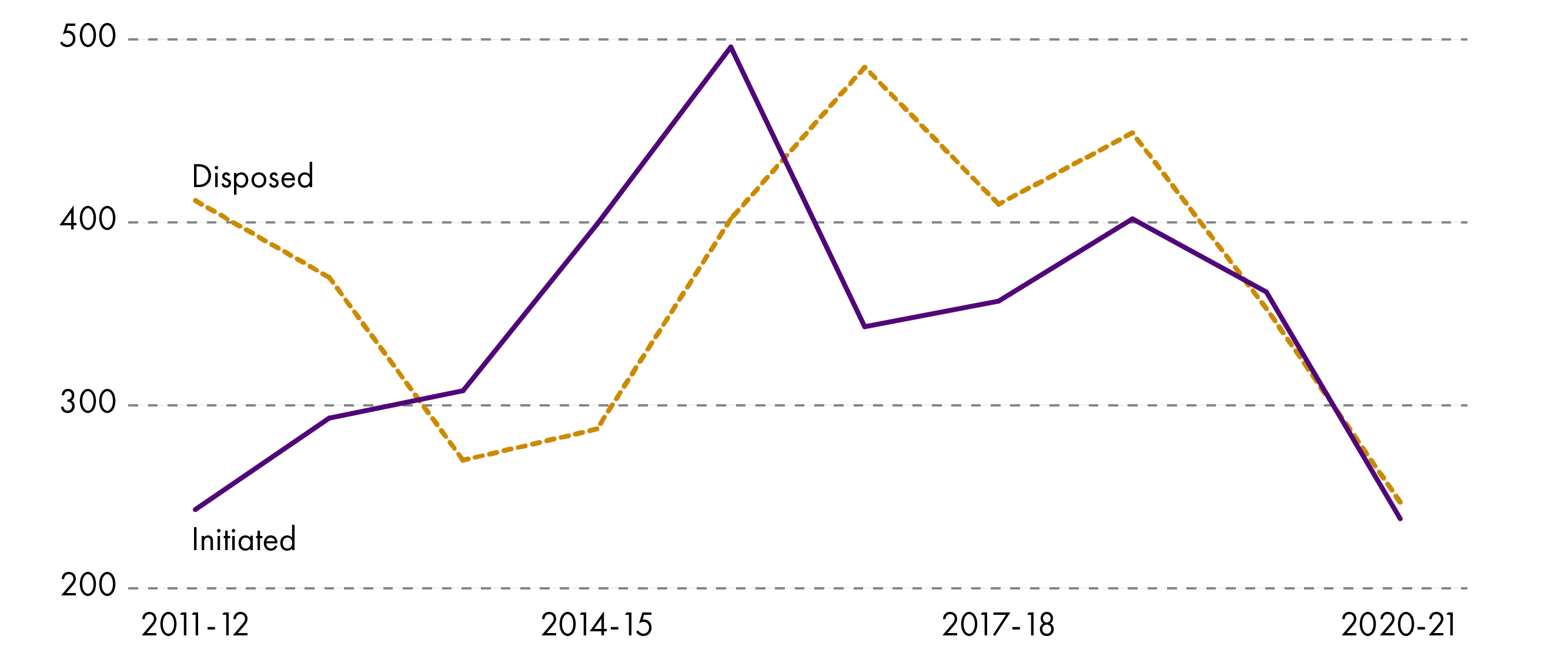

As Figure 1 shows, over the last ten years, the number of judicial review actions initiated in any given year has been variable.

Between 2015-16 and 2016-17 there was a large decrease in the number of cases initiated. This is partly due to a rise in number of judicial reviews in the preceding year, ahead of the reforms specified in the Courts Reform (Scotland) Act 2014.3 Some of these reforms were unfavourable to would-be petitioners, likely encouraging them to initiate proceedings before the law changed.

There were 238 judicial review cases initiated in 2020-21, a 34% decrease on 2019-20.4 This decrease relates to the drop in the number of judicial review cases on immigration and asylum during the pandemic, a topic discussed in more detail in the next section of the briefing.

What are judicial review cases raised on?

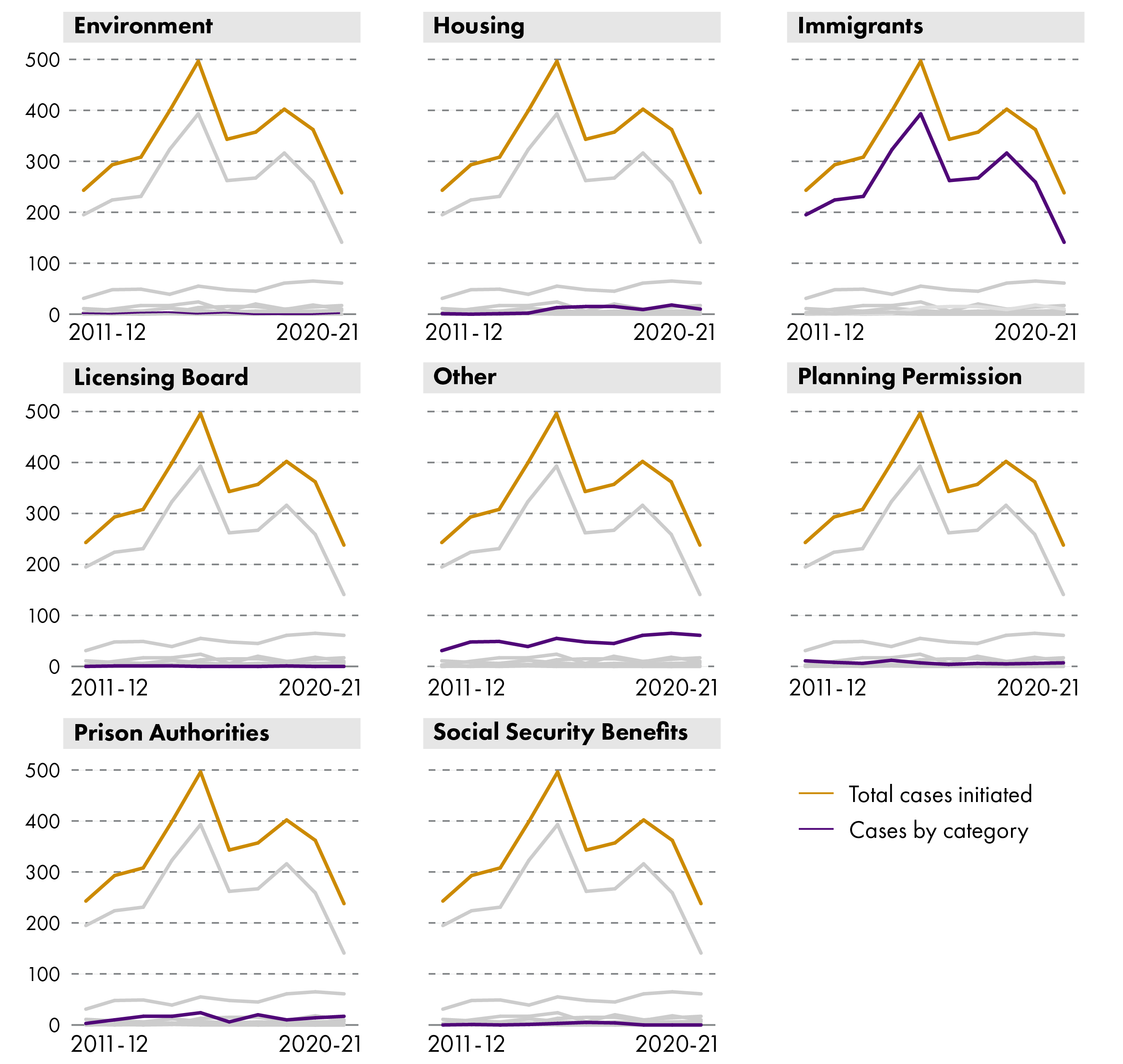

Using the Scottish Government's categorisation,1Figure 2 shows the trends in judicial review cases initiated over the last ten years by policy area.

Immigration and asylum cases

Immigration and asylum cases have been a significant driver of overall trends in judicial review cases, and typically make up a largest proportion of total cases initiated.123

For example, immigration and asylum cases represented between 70% and 80% of judicial review cases started in Scotland over the five years between 2015-16 and 2019-20.3

Judicial review cases relating to a person's immigration or asylum status are often started in response to a decision to deport someone from Scotland.

An academic article (from 2015)2 identifies the following factors as being present in policy areas where there are a lot of judicial review actions:

the absence of alternative remedies - or the presence of gaps in available remedies

the importance of the issue for the litigant

the availability of suitably expert legal advice and representation

the ability of the potential petitioners to finance the litigation (e.g. through legal aid).

The article argues that, in immigration and asylum cases, all these factors come together.

In 2020-21, however, the number of immigration and asylum cases initiated fell by 46% compared to the preceding year. They made up around 60% of all judicial review cases initiated in 2020-21.3All of, or part of, the drop is likely to be because the Home Office made less decisions in relation to a person's immigration or asylum status during the height of the pandemic.

Other cases

The next largest set of cases in the Scottish Government statistics are a group of cases classified simply as other, without any further breakdown by subject area.

This category is rising as a percentage of the total cases. For example, it represented around 18% of the total cases in 2019-20, compared to around 10% of cases in 2014-15.1

Overall, the 'other' category may obscure changes in the nature of the judicial review caseload which might otherwise attract policy and academic commentary.

There have been two main surges in cases involving prison authorities: one in 2003–2004, and a second one in 2009–2010.2 Numbers have dropped dramatically since the second surge in 2009–10.3Both surges are thought to relate to cases connected to the use of ‘slopping out’. It was ultimately established by case law that this contravened prisoners’ human rights and gave rise to a claim for damages.2

A snapshot of some recent high-profile cases

The snapshot of recent cases in this section, and other sections, of the briefing is not intended to be an exhaustive treatment of recent developments in judicial review.

The cases that make media headlines, and raise the public's awareness of judicial review, are not those which the published statistics suggest make up the largest proportion of the judicial review caseload in Scotland.

High-profile judicial review actions tend to be those that involve legal challenges to key policy decisions by the UK and Scottish governments. Two areas of government activity have been particularly prominent in this regard in recent years:

the UK's decision to leave the EU (Brexit) and the implementation of that decision

the UK and Scottish governments' response to COVID-19 pandemic.

Some high-profile judicial review challenges in these areas are set out in the box below.

R (Miller) v Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union (2017)1

The UK Supreme Court ruled that the UK Government was not allowed to begin the process for leaving the EU (via an Article 50 notification) without explicit authority from an Act of Parliament. The unsuccessful argument of the UK Government had been that its prerogative powers, i.e. special powers which can be used without Parliament's approval, could be used to invoke Article 50.

R (Miller) v The Prime Minister; Cherry and others v Advocate General for Scotland (2019)2

These joint cases explored the limits of the prerogative power to prorogue (suspend) the UK Parliament. The cases concerned whether the advice given by the Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, to Queen Elizabeth II that the UK Parliament should be prorogued was unlawful. At the time, withdrawal from the EU was imminent.

The UK Supreme Court found that an attempt to prorogue Parliament for a period of five weeks significantly interfered with Parliament's ability to carry out its constitutional functions, including that of holding the Government to account. With no reasonable justification offered for such an interference, it was found to be unlawful.

Philip v Scottish Ministers (2021)3

In this case brought by a number of Christian churches, the Court of Session found that the closure of places of worship by the Scottish Government under COVID-19-related regulations was unlawful. The successful ground of challenge was based on the right to worship as a Convention right. The court found that the legislative interference with that Convention right had been disproportionate.

Katherine Rowley v Minister for the Cabinet Office (2021)4

In this case, the High Court of Justice for England and Wales found that the UK Cabinet Office had discriminated against a profoundly deaf woman and breached its statutory duty to make reasonable adjustments in respect of a disability. This breach occurred when the Cabinet Office had failed to provide British Sign Language interpretation for two live scientific briefings for the public in September and October 2020.

Night Time Industries Association v Scottish Ministers (2021)

This case involved a challenge to the introduction in Scotland of a statutory 'vaccine passport scheme', which required proof of vaccination for entry to bars and nightclubs. The Court of Session did not accept that the scheme was disproportionate, irrational or unreasonable but was "an attempt to address the legitimate issues identified in a balanced way." Consequently, it was within the margins of a reasonable government response to the pandemic.

R (on the application of Good Law Project and EveryDoctor) v Secretary of State For Health and Social Care (January 2022)

This case, on contracts relating to the supply of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), was one of several cases relating to the UK Government's awarding of contracts for various goods and services during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The High Court of Justice for England and Wales found that the Government's operation of a 'VIP lane', which conferred preferential treatment for bids was unlawful. This approach failed to comply with the obligations of equal treatment and transparency contained in the relevant legislation relating to public contracts.i However, even if two such suppliers had not been allocated to the high priority lane, it was highly likely that they still would have been awarded contracts because of the substantial volumes of PPE they could supply to meet an urgent need. In February 2022, the Good Law Project reported it had sought permission from the court to appeal parts of the High Court's judgement.

Key constitutional developments affecting judicial review

This section of the briefing considers three key constitutional developments relevant to judicial review over the last fifty years:

Human rights and judicial review

This first section considers how the development of human rights law has affected judicial review.

The Human Rights Act 1998

The Human Rights Act 1998 (‘the Human Rights Act’) came fully into force in 2000. As explained earlier in the briefing, the Act provides for certain rights protected by the European Convention on Human Rights ('the Convention') to be part of UK domestic law. These rights are known as Convention rights.

A new ground of review - breach of Convention rights

One effect of the Human Rights Act is that it is now possible to bring an action for judicial review in the Court of Session based on an alleged breach of one of the Convention rights. Previously, an individual alleging a breach had to take their case to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg.

More information on the content of specific Convention rights are provided under Grounds of judicial review at Breach of Convention rights.

Public bodies and subordinate legislation

Section 6 of the Human Rights Act provides that it is unlawful for a public authority to act in a way which is incompatible with a Convention right, unless the wording of an Act of the UK Parliament means they have no choice.

Section 6 allows people whose rights have been infringed to challenge the validity of both:

administrative decisions

subordinate legislation under which decisions are made.

Administrative decisions and subordinate legislation can be struck down by the courts, i.e. found to be invalid and unenforceable, by virtue of section 6.

Acts of the UK Parliament

This section of the briefing considers how the Human Rights Act affects Acts of the UK Parliament.

Note that, separately, Acts of the Scottish Parliament are classified as subordinate legislation under the Human Rights Act.i

The Scotland Act 1998 also contains specific provisions on Convention rights and Acts of the Scottish Parliament, discussed later in the briefing. It is these provisions which are commonly used in practice in relation to human rights challenges of Acts of the Scottish Parliament.

Obligation to interpret

Under the Human Rights Act, courts are obliged to interpret Acts of the UK Parliament consistently with Convention rights so far as it is possible to do so.i Therefore, some cases of potential inconsistency between provisions of such Acts of Parliament and Convention rights can be resolved by the court's interpretation of those provisions.

Declaration of incompatibility

Where it is not possible to interpret an Act of the UK Parliament so as to make it compatible with Convention rights, a higher court can issue a declaration of incompatibility in relation to that act.i

In the context of a Scottish judicial review, such a declaration can be made by the Court of Session and, should the case be appealed to UK Supreme Court, that court.

A declaration of incompatibility:

does not make an Act of Parliament invalid

is not binding on the parties against which it is issued

does not have any effect on the rights of the parties to the case in which it is made.

Instead UK Government ministers are empowered to make an order repealing or amending the legislation in question, as they think appropriate, to remove the incompatibility.ii

A declaration of incompatibility can still have a big impact in practice. UK Government ministers will be aware that there is the possibility that the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg could find the United Kingdom in breach of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

Providing all domestic judicial remedies have been exhausted, it is still an option for an individual to take a case against the United Kingdom to Strasbourg because they feel they been denied a remedy under the ECHR.

The impact of the UK's changing relationship with the EU on judicial review

On 1 January 1973, the UK joined the European Economic Community, which has since evolved to become today’s European Union ('the EU').

The UK left the EU on 31 January 2020 ('Brexit'). There then followed a transition period, before EU law ceased to have effect in the UK at 11 pm on the later date of 31 December 2020.

This section considers the impact of the UK's (changing) relationship with the EU on the law of judicial review.

The impact of the UK's membership of the EU

Prior to joining the EU, the UK Parliament was recognised by the UK courts as sovereign. This meant that Acts of Parliament were treated as the supreme law of the land and were immune from judicial review.

When the UK joined the EU, two key principles became fundamental:

The principle of the supremacy of EU law says that a country's domestic law must be consistent with EU law (whatever the source of that EU law). Furthermore, to the extent that it is not consistent, EU law must take priority over domestic law.

The principle of direct effect says that, where certain conditions are satisfied, rules of EU Law can be relied upon directly by litigants in national courts. Crucially, this position applies even if the law in question has not been specifically incorporated into a member state’s domestic legal system.

A very important consequence of these two principles is that, in the UK, Acts of Parliament, subordinate legislation and decisions of public bodies could be the subject of a judicial review action in the national courts on the basis that they were incompatible with EU law.

The UK's departure from the EU and EU retained law

Since EU law ceased to apply in the UK (at 11 pm on 31 December 2020), as a general rule, it has not been possible to raise an action for judicial review based on an alleged breach of EU law.

The one exception to this general rule is where the UK-EU Withdrawal Agreement, discussed later in the briefing, requires the UK to adhere to EU law, principally in the context of Northern Ireland.

In the post-Brexit era, the key concept which affects judicial review is retained EU law.i

Retained EU law is a new type of UK domestic law. Broadly speaking, it is a snapshot of the EU law which was in place in the UK at the point EU law ceased to apply in the UK.

Not all EU law became retained EU law, a topic discussed in more detail later in the briefing.

Retained EU law was created so that there was no gap in UK law immediately after EU law stopped applying. The underlying policy aim was to provide legal certainty in the period immediately following EU exit.

The UK Government has recently announced it is planning to introduce a ‘Brexit Freedoms Bill’, with one policy aim to make make it easier to amend or remove retained EU law than it is at present.

Retained EU law and judicial review

There are three key ways in which retained EU law might be relevant in the context of judicial review after Brexit:

In certain circumstances, it will be possible to bring a petition for judicial review based on an alleged breach of retained EU law.

Retained EU law itself can sometimes be challenged by way of judicial review. However, depending on the type of retained EU law, it cannot be challenged on all the grounds of judicial review which are available in other circumstances.

Domestic legislation (made on or after 11 pm on 31 December 2020) which amends retained EU law can itself be judicially reviewed.

The first two scenarios involve complex areas of law and are considered in more detail in the next sub-sections of this briefing.

A possible breach of retained EU law

To explain why a judicial review action might be possible for an alleged breach of retained EU law, two key terms are used in this part of the briefing:

First, IP completion day, which is defined in legislation as 11 pm on 31 December 2020 (when EU law ceased to apply in the UK).i

Second, as a convenient shorthand, UK domestic law made before the IP completion day is referred to here as pre-IPCD domestic law.

Section 5 of the European Union Withdrawal Act 2018 ('the 2018 Act') says:

The principle of the supremacy of EU law does not apply to any legislation or other legal rule passed or made on or after IP completion day.

However, with some exceptions and qualifications, the principle of the supremacy of EU law continues to apply on or after IP completion day to pre-IPCD domestic law.

Crucially, this means that there could be a challenge by way of judicial review to pre-IPCD domestic law on the ground that the domestic law is incompatible with retained EU law.

For those interested in the detail of the 2018 Act:

The rules contained in section 5 of the 2018 Act are themselves subject to the overriding supremacy of the UK-EU Withdrawal Agreement, a topic explored later in this briefing.

The principle of supremacy of EU law applies almost exclusively to pre-IPCD domestic law. However, as a limited exception, it can also apply to certain modifications of pre-IPCD domestic law which are made on or after IP completion day.ii

A UK Government policy paper from January 2022 suggests that the Brexit Freedoms Bill, recently announced in the Queen's Speech, may revisit the issue of whether the principle of the supremacy of EU law should apply in respect of pre-IPCD domestic law.

Challenging retained EU law by way of judicial review

After Brexit, an individual or organisation might also be able to bring a judicial review action to challenge a piece of retained EU law.

However, there are several types of EU retained law, and what is possible here depends on the type of retained EU law at issue. Two of the main types of retained EU law in this context are:

These are considered in turn in the next two sub-sections of this briefing.

Other relevant parts of the UK-EU Brexit arrangements

Although not falling within the definition of retained EU law, some aspects of UK-EU Brexit agreements are directly enforceable in the UK legal system in the same way that EU law was previously:

First, the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 says the UK-EU Withdrawal Agreement, including the Northern Ireland Protocol, has direct effect in the UK legal system where the agreement requires this.i The UK-EU Withdrawal Agreement sets out the terms of the UK's exit from the European Union. The Northern Ireland Protocol helps prevent checks along the land border between Northern Ireland (in the UK) and the Republic of Ireland (in the EU).

Second, the European Union (Future Relationship) Act 2020 makes a general modification to all existing domestic law, so far as necessary to comply with the UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement.ii This agreement, which is separate from the UK-EU Withdrawal Agreement, sets out the UK-EU future relationship.

It seems possible that a potential judicial review action could be based on domestic laws or action by a public body that allegedly breaches either of those agreements.

Note that the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill was introduced by the UK Government on 13 June 2022. If enacted, the Bill would empower UK Ministers to disapply elements of the Northern Ireland Protocol unilaterally. The Institute for Government has provided a helpful summary of the Bill.

Subordinate legislation after Brexit

There is one final point relating to judicial review and the post-Brexit world.

The powers of UK and Scottish Government Ministers to make subordinate legislation in certain areas are much more significant that they were prior to the UK's EU exit. This is as a result of powers granted to Ministers in various different pieces of Brexit-related primary legislation.

Noteworthy policy changes can now be made by subordinate legislation. These include the kind of changes which would previously have required the Scottish or UK Parliaments to consider primary legislation (i.e. a bill).

The change of approach is significant in the context of judicial review. This is because a review of subordinate legislation is possible on the full range of grounds associated with judicial review, compared to the more restrictive approach taken to Acts of Parliament.

Judicial review and the Scottish Parliament and the Scottish Government

This section of the briefing specifically considers judicial review in the context of the Scottish Parliament and the Scottish Government.

Two key topics are covered in this section of the briefing:

an introduction to the Scotland Act 1998 and its relationship with judicial review. This includes a discussion of how a key concept in the Act, legislative competence, changed after Brexit

whether Acts of the Scottish Parliament can be subject to a petition for judicial review on the so-called 'traditional' grounds of review. As a reminder, these are illegality, procedural impropriety or unfairness and irrationality or unreasonableness.

The Scotland Act 1998: legislative competence

The Scotland Act 1998 ('the Scotland Act') created the Scottish Parliament and the Scottish Government (or the Scottish Executive as it then was).

The Scotland Act transferred significant statutory powers (devolved powers) from a UK level to the Scottish Government and the newly created Scottish Parliament. The remaining powers (reserved powers) are still exercisable by the UK Parliament and Government.

The Scotland Act has significant implications for the nature of judicial review. As outlined earlier in the briefing, the Scotland Act says that an Act of the Scottish Parliament is not law in so far as any of its provisions are outwith the legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament.

Statutory provisions falling outwith legislative competence include:

those addressing matters reserved to the UK Parliament

those which are incompatible with Convention rights, making human rights an integral part of the devolution settlement as well.

The Scotland Act also imposes similar limitations on Scottish subordinate legislation and acts of, or failures to act by, members of the Scottish Government.i

Alleged non-compliance with these provisions of the Scotland Act by the Scottish Parliament or the Scottish Government fall into a specific category of legal questions known as devolution issues. As well as arising in other types of court proceedings, devolution issues can be the subject of a petition for judicial review before the Court of Session.

Where there is an alleged breach of Convention rights by the Scottish Government, including in relation to subordinate legislation it has made, the case of Somerville v Scottish Ministers (2007) is significant. The case determined that there is a choice of raising an action for judicial review under either the Scotland Act or the Human Rights Act.1 However, the legal consequences are the same in both situations: An unlawful decision or provision of subordinate legislation may be struck down (i.e. found invalid and unenforceable).

The legislative approach to Acts of the Scottish Parliament (under the Scotland Act) differs from the approach to the Acts of the UK Parliament (under the Human Rights Act).

If an Act of the Scottish Parliament is found to be outwith legislative competence, including where it is incompatible with a Convention right, it is invalid and can be struck down by the courts.ii

On the other hand, as explained earlier in the briefing, an Act of the UK Parliament which is incompatible with a Convention right (under the Human Rights Act) remains valid. However, it can be the subject of a declaration of incompatibility.iii

The approach to Acts of the Scottish Parliament and legislative competence

To date, most challenges to the legislative competence of Acts of the Scottish Parliament under judicial review have failed. Two examples of successful challenges to Acts of the Scottish Parliament are set out in the box below:

Salvesen v Riddell (2013)1

A legislative provision relating to agricultural tenanciesi was found by the UK Supreme Courtto violate Article 1 of Protocol 1 of the ECHR (which protects property rights). The provision was accordingly outwith legislative competence.

The Christian Institute and others v The Lord Advocate (2016)2

Part 4 of the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014 has the key policy idea that every child in Scotland should have a 'named person' to safeguard the welfare of every child in the country. The UK Supreme Court found Part 4 to be a disproportionate interference with the rights of children, young people and their parents under Article 8 of the ECHR (which protects private and family life). The provisions were therefore outwith legislative competence and, consequently, were not brought into force. In 2019, the Scottish Government announced its intention to scrap the statutory scheme.

Legislative competence: EU law and EU retained law

Breaches of EU law were part of the original scope of what was outwith legislative competence under the Scotland Act. i However, since 11 pm on 31 December 2020, when EU law ceased to apply in the UK after Brexit, this has not been the case.ii

The UK's departure from the EU did have an additional (temporary) effect on the concept of legislative competence. This relates to EU retained law, i.e. the new type of UK domestic law created when EU law ceased to apply in the UK.

Specifically, the European Union Withdrawal Act 2018 ('the 2018 Act') inserted section 30A into the Scotland Act 1998.iii This provision (now repealed) said that it was not within the legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament to modify any retained EU law that is set out in so-called freezing regulations.

These regulations could be made by UK Ministers. They could specify the parts of retained EU law which the UK Government wanted to protect from modification by the devolved legislatures. Such regulations would expire five years after they came into force.

UK Government Ministers only had the key power to make these freezing regulations until 31 January 2022. Ultimately, no relevant regulations were made and section 30A itself was repealed by regulations which came into force on 31 March 2022.iv

Acts of the Scottish Parliament and the 'traditional' grounds of review

As mentioned earlier in the briefing, the so-called ‘traditional’ grounds of judicial review fall under the broad headings of:

These grounds of review do not apply to Acts of the UK Parliament.

The position with Acts of the Scottish Parliament is as follows:

By virtue of specific provision in the Scotland Act, procedural impropriety does not apply to Acts of the Scottish Parliament.i

A specific (statutory) example of illegality is contained in the Scotland Act, that is to say being beyond the legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament.

Aside from this specific statutory form of illegality, the 2011 UK Supreme Court decision in the AXA case clarified that the traditional grounds of illegality and unreasonableness did not apply to Acts of the Scottish Parliament, save in exceptional circumstances.1

The exceptional circumstances referred to by the UK Supreme Court in the last bullet point were:

a breach of fundamental rights. There is no definitive list of what constitutes a fundamental right, but it is a concept the Supreme Court in particular has been active in developing in recent years.

a breach of the rule of law. In its most basic form, the rule of law is the constitutional principle that no one is above the law.

The mechanics of judicial review in more detail

This section of the briefing revisits some aspects of the law associated with judicial review actions which merit a more detailed treatment than was possible in the overview at the start of this briefing.

Specifically, this section covers in more detail:

who can a bring a judicial review action (covered by the rules on standing)

the circumstances in which a third party can intervene in a judicial review action

the scope of judicial review in Scotland which, as noted earlier, differs from that in England and Wales

the grounds for judicial review, both established grounds, as well as emerging ones and ones where their scope is uncertain

the remedies available where a judicial review action is successful.

Who can raise judicial review proceedings - in more detail

As explained earlier, the rules on standing determine who may bring an action for judicial review. This section of the briefing covers:

Standing in judicial review cases: the general position

In Scotland, until ten years ago, for a petitioner to have standing to bring a judicial review action, the outcome of the case would have to materially affect their private legal rights.

This caused particular difficulties for petitioners in the context of public interest standing. This is where an individual, group or organisation seeks to represent the general public or some part of it.

The previous law on standing in Scotland was widely criticised and was changed by the UK Supreme Court in 2011 in what is known as the AXA case.1

The Supreme Court decided in the AXA case that the more liberal test of sufficient interest used in England and Wales should be used in Scotland.

The new test in the AXA case - in more detail

Lord Hope and Lord Reed were the two judges who gave the leading judgements in the AXA case. Both adopted a test of standing based on the petitioners' interests, rather than on their legal rights (Lord Hope at para 62, Lord Reed at para 170 of the judgment).

Lord Hope (at para 63) expressed the view that the new test meant that a petitioner seeking review of a particular measure required to be directly affected by it. His formulation of the new test excluded 'the mere busybody' and required the person to have:

a reasonable concern in the matter to which the application related (para 63)

He also said:

A personal interest need not be shown if the individual is acting in the public interest and can genuinely say that the issue directly affects the section of the public that he seeks to represent (para 63).

Lord Reed explained the rationale for the new test in terms of the important constitutional principle of the rule of law. As noted earlier, in its most basic form, this is the principle that no one is above the law.

Lord Reed said a public authority can violate the rule of law without infringing the private legal rights of any individual. Hence, why a rights-based approach to standing was, in his view, insufficient (para 169 of the judgment).

However, Lord Reed also said that what is required by the new test of standing can still depend on the context of the case:

In some contexts, it is appropriate to require an applicant for judicial review to demonstrate that he has a particular interest in the matter complained of … In other situations, such as where the excess or misuse of power affects the public generally, insistence upon a particular interest could prevent the matter being brought to court, and that in turn might disable the court from performing its function to protect the rule of law. (para 170)

Shortly after the AXA case, the Supreme Court again had to consider the Scottish test of standing in Walton v Scottish Ministers (2012),1 as part of a statutory appeals process.

When this case was first appealed, the Court of Session said that, had it been an action for judicial review, Mr Walton would not have had ‘sufficient interest’. When the matter ultimately came before the Supreme Court, it strongly disagreed. It took the opportunity to reaffirm the new liberal approach to standing for judicial review.

After AXA - uncertainties and the continued importance of case law

The sufficient interest test has now been placed on a statutory footing by section 89 of the Courts Reform (Scotland) Act 2014 ('the 2014 Act'), which inserted a new provision in the Court of Session Act 1988.i However, no further explanation of sufficient interest was provided by the 2014 Act.

Consequently, in future, the law as set out in the decided cases of the Supreme Court and the Court of Session will remain significant on the topic of what is required to satisfy the test.

A leading Scottish academic, Professor Tom Mullen, writing in 2015 on the new test of standing and how it might develop, commented:

The judgments of Lord Reed and Hope in AXA and Walton provide only a general statement of the new approach to standing and the rationale for it. They do not resolve all of the issues that might arise when litigants assert that they have standing to sue in the public interest, in particular the factors which the court should take into account in deciding whether to recognise the standing of a public interest litigant.

Mullen, T. (2015). Public Interest Litigation in Scotland. Jur. Rev. 2015, 4, 363-383 at pp 371-372.

Sufficient interest under statute

Given the issues environmental bodies have traditionally had in relation to standing, one interesting recent statutory development is found in the UK Withdrawal from the European Union (Continuity) (Scotland) Act 2021 ('the 2021 Act'). The 2021 Act gave Environmental Standards Scotland, a new independent body set up to ensure the effectiveness of environmental law, a power to apply for judicial review where there is an alleged breach of environmental law.i

The 2021 Act says the new body is to be treated as having sufficient interest in the subject matter of any application which it may make (or of any legal proceedings in which it may intervene).

However, this is not the first time a public body has been given automatic standing under statute when it wants to bring certain types of judicial review case. Another example relates to the Equalities and Human Rights Commission, which has this status for judicial review cases (including Scottish cases) connected to the Commission's functions.ii It appears the Commission has had to target its resources carefully when using its legal powers and similar considerations are likely to apply for other bodies with equivalent powers.

Cases relating to Convention rights

For judicial review cases relating to Convention rights, the test for standing is different from the general test.

While some petitioners have a special status, the Human Rights Act 1998 usually requires the person raising the action to be a victim.i The meaning of victim in this context is the subject of extensive case law.

In 2015, Professor Mullen argued that, if the victim test is the usual gateway to standing, the result may be that the UK’s obligations under the Convention are not adequately supervised by the court. Those who do have standing as victims (based on personal interests) may be unaware they could sue, or may choose not to take their case to court.1

Also in 2015, the Inner House of the Court of Session had to consider this issue in Christian Institute v Lord Advocate.2 The Inner House expressed the view that the practical effect of the restriction in the victim test was limited in cases in which a public interest body was willing to a) support an individual’s legal challenge; or b) apply to intervene in any case raised by a potential victim.

However, the debate has continued more recently on whether the victim test is satisfactory in policy terms. As discussed later in this briefing, the Scottish Government is proposing that there will be a Human Rights Bill in this parliamentary session, with the aim of strengthening human rights protection in Scotland. The independent report of the National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership ('the National Taskforce Report') published in March last year, is a key piece of work related to this goal.3

The National Taskforce Report recommends replacing the victim test with the sufficient interest test in cases relating to Convention rights (recommendation 23).

Funding a judicial review action

A key issue for any would-be petitioner in a possible judicial review action is how to fund it.

A person initiating a petition for judicial review has the following potential costs:1

their own legal costs, which can be particularly expensive as judicial review requires the involvement of lawyers with rights to appear in the Court of Session, mainly advocates. In addition to advocates, solicitors, another type of lawyer, also typically work on the case.

court fees, payable to the court. These can be a considerable figure to be factored into the overall costs, usually over a thousand pounds for a day's hearing in the Outer House.i2

the expenses of their opponent if they lose. This includes the opponent's legal costs and court fees. There may also be liability for the expenses of any intervening third parties in the case.

Note that certain exemptions from court fees apply, including for those litigants who qualify for Civil Legal Aid or who are receiving certain state benefits.ii

A key advantage of qualifying for Civil Legal Aid is that it also offers a level of protection against liability for the other side's legal expenses.iii

Advice and Assistance

Advice and Assistance funds legal advice from a solicitor but does not cover representation by a lawyer in court. The term legal advice is broad enough to include investigation, negotiation and any work involved in a subsequent application for Civil Legal Aid.1

Advice and Assistance is available where:i

the client is financially eligible, based on their capital and income

the issue on which advice is being sought relates to Scots law, which includes UK law as it applies in Scotland.

Civil Legal Aid

Note that Civil legal aid is available only to persons.iThis rule makes NGOs and incorporated or unincorporated community groups ineligible.1

Civil Legal Aid, which covers legal representation in court, is also only granted by the Scottish Legal Aid Board (SLAB) where a number of tests are met. One test relates to the applicant's financial eligibility, based on the applicant's capital and income.ii

Another of the tests relating to eligibility for Civil Legal Aid is that it is reasonable in the particular circumstances of the case that the applicant should receive it.iii It is this test which, in practice, can create a barrier to funding for judicial review cases.

In relation to the reasonableness test, where a number of people have the same interest in the case, Civil Legal Aid will not be provided to one individual unless it can be shown that:

an individual will suffer serious prejudice, or

it would not be reasonable for the other people concerned to pay the expenses being sought. iv

In this context, the Environmental Rights Centre for Scotlandhas recently argued that a person wishing to undertake environmental litigation is prone to a 'joint interest' with others, as there may well be a number of individuals with similar concerns about the issue in dispute.

In assessing reasonableness, another issue is that SLAB will also examine the likely costs of any case. It will balance these against the benefit an applicant will get from the proceedings.

Judicial review actions are particularly expensive from the outset because they must be raised in the Court of Session. However, the matters they relate to may not be significant in financial terms. On the other hand, a particularly important matter of law or status could justify the expense in the analysis by SLAB.

Protective expenses orders

As mentioned earlier in the briefing, the normal rule of litigation is that expenses follow success. In other words, the losing party will usually pay the legal expenses of the winning party in a case.

However, the usual rule can be modified for cases in which the litigant seeks to advance the public interest. The aim is to make it less likely that exposure to liability for expenses will deter litigation which is in the public interest.

In a Scottish judicial review action (and indeed in some other types of litigation) it is possible for the court to make a protective expenses order (‘PEO’). This limits the financial liability of the person raising the action.

The equivalent term in England and Wales is a cost capping order, previously a protective costs order.1

There are currently two separate legal approaches to PEOs in Scotland:

PEOs in environmental cases

Chapter 58A of the court rules applicable to the Court of Session set out how PEOs should operate in environmental cases. There have been various iterations of these rules, with the current set applicable since December 2018.

If the judge decides that the proceedings would be prohibitively expensive for the person applying for the PEO, having regard to various factors set out in the court rules,i they must award a PEO.

PEOs contain two caps on financial liability:

One cap limits the applicant’s liability for the other side's legal expenses to £5,000.

The other cap limits the respondent’s liability in expenses to the applicant to the sum of £30,000.ii

These are the default PEO caps, they may be raised or lowered 'on cause shown', i.e. when the court is satisfied there is a reasonable basis for doing this.

The first cap aims to protect the petitioner. On the other hand, the second cap is intended to address the potential for a PEO to operate as a ‘blank cheque’, enabling a petitioner to litigate in an unreasonable or disproportionate fashion.

The current PEO regime for environmental cases has been recently criticised by the Environmental Rights Centre for Scotland as being insufficient to improve the affordability of environmental litigation.1 The cost of such litigation is considered more generally in a later section of this briefing, in the context of government compliance with the Aarhus Convention.

Other public interest cases

For other public interest cases not falling under the regime in Chapter 58A of the court rules, the decision to award a PEO in a particular case, and at what level, is still a matter for the discretion of the courts.

In 2009, the report of the Scottish Civil Courts Review recommended that there should be a new regime for all PEOs in public interest litigation, with the court being required to have regard to specified criteria in their decision-making process.1 However, the report of the Review of Expenses and Funding of Civil Litigation (the Taylor Review) later made recommendations on this topic in 2013. Its report largely favoured the retention of the court’s existing level of discretion.2

The Aarhus Convention and environmental cases

The UK is a signatory to the Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters (the Aarhus Convention).

There have been a number of findings that the Scottish legal system is non-compliant with the Aarhus Convention with respect to its requirements on access to environmental justice. The first of those findings was made in 2014, and the most recent in October 2021.1

The main source of non-compliance is the failure to meet the requirement that access to environmental justice must be not prohibitively expensive (Article 9(4)).

The Scottish Government has not responded publicly to the October findings, but it did consider the issue of court fees for environmental cases in its recent consultation on court fees.

Relating to the Aarhus findings last year, the Environmental Rights Centre for Scotland made various recommendations for improving the situation in relation to the costs of environmental litigation, including judicial review actions.1

For example, the Centre recommended the existing regime of Protective Expenses Orders for environmental cases be replaced with what is known as Qualified One Way Cost Shifting. The general rule would be that a petitioner would not be liable for the expenses of any other parties if the judicial review were unsuccessful. However, conversely, a petitioner would still be able to claim their expenses from the respondent if the judicial review were successful.

See also the later section of this briefing on other policy developments relating to access to environmental justice associated with 2021 Brexit-related legislation.

Third party interventions

As explained earlier in the briefing, interventions are written or verbal arguments on key legal issues relating to the case by third parties in judicial review proceedings with an interest in the case.

Sometimes specific legislation enables individual public bodies to intervene in certain types of judicial review case. For example:

the new body, Environmental Standards Scotland, has a statutory power to intervene, either with the court's permission or invitation, in judicial review cases relating to environmental lawi

under statute, the Equality and Human Rights Commission has capacity to intervene in any judicial review case which it appears to the Commission is connected to its functions.ii See the box below for a recent example of the Commission's power in action.

S v Scottish Ministers (2021)1

S is a prisoner serving a life sentence. In this case he challenged, by way of judicial review, decisions of the prison authorities. They had refused him exceptional escorted day absence ('EEDA') to enable contact with his elderly grandmother outside of the prison.

The Outer House of the Court of Session refused permission to allow S to proceed by way or judicial review. S appealed this decision. At the appeal stage in the Inner House, the Equality and Human Rights Commissionintervened in writing. In its intervention, the Commission considered the role of the public sector equality duty in policy formulation. It also advanced arguments about the approach for prisoners to Article 8 of the ECHR (which protects the right to a private and family life). The appeal was ultimately successful.

Otherwise, interventions are permitted in two ways under the current court rules:

Where the person is 'directly affected'

In the first place, a party who considers that they are directly affected by the issues raised in the case, may apply to enter the process and become a party to the case.i This is what individuals affected by an asbestos-related condition sought to do in the AXA case, discussed earlier in the briefing.

Public interest intervention

There is also a separate procedure contained in the court rules for a public interest intervention.i

A public interest intervention allows a person to make an application to the court for leave to intervene in a judicial review petition where he or she believes that any issue in the case raises a matter of public interest. The court may grant permission if it considers that certain requirements are satisfied.

In the Court of Session, public interest intervention is generally in written form and is subject to rules as to length. An oral intervention is only permitted in exceptional circumstances.ii The UK Supreme Court has demonstrated a greater willingness to hear oral interventions.

Until relatively recently, public interest interventions were rare in practice in Scotland but they are becoming more common. A noteworthy example of the courts' approach is given in the box below:

The Christian Institute and others v Scottish Ministers (2016)12

This case, referred to earlier in the briefing, related to the Scottish Government's legislation to create a 'named persons' scheme. Before the Inner House, CLAN Childlaw, a charitable Scottish law centre for children and young people, was granted permission to intervene in writing in the public interest. However, the Inner House did not agree with CLAN's Convention rights-based arguments against the scheme.

Before the UK Supreme Court, the charity again intervened - in writing and orally. The intervention was high-profile, and ultimately the Supreme Court found that certain Convention rights had been breached by the Scottish Government.

The scope of judicial review

As explained earlier in the briefing, the scope of judicial review is different in Scotland compared to England and Wales.

The general position

In England and Wales, a distinction has developed between cases involving public law and those involving private law rights, with judicial review only being competent in relation to public law rights.

The effect of this distinction in judicial review cases south of the border is that the decisions of private bodies are not usually open to judicial review.

In the important case of West v Secretary of State for Scotland (1992)1 the English approach was rejected for Scotland. It was confirmed that the actions and decisions of private bodies could be subject to judicial review.

The judges in West stated that what was required for a competent judicial review action was a tripartite relationship between:

the source of the decision making power

the person or people to whom that decision making power has been delegated

the person or people affected by that decision making power.

The practical effect of this test is that the decision of a private body, for example, the decision of a sporting association or golf club might be able to be judicially reviewed, where a committee applies the association or club rules to a member.

Later case law has suggested that the tripartite relationship is not an exhaustive statement of all the circumstances where judicial review is possible, nor should it be interpreted too literally.2

The scope of judicial review in this context is also less important in practice than once it was. For the current court rules now allow the transfer of cases brought under the incorrect court procedure to the right court procedure. Accordingly, a case beginning under the judicial review procedure can be transferred to what is known as the ordinary procedure.i3

Cases relating to Convention rights

In terms of the scope of judicial review, there is a special rule applicable to judicial review cases concerning Convention rights.

The Human Rights Act 1998 provides a right of challenge in respect of public authorities acting in contravention of Convention rights. This means that the public or private nature of the body remains important in this context.i

Grounds of judicial review

This section of the briefing explores the grounds for judicial review in detail.

The grounds (emerging and established) covered in this part of the briefing are as follows:

illegality (in the traditional judicial review sense)

breach of Convention rights (a specific statutory form of illegality)

breach of retained EU law (another specific statutory form of illegality)

unjustified departure from someone's legitimate expectations

Although the grounds have been divided into categories for this purpose, any type of categorisation is somewhat artificial. The grounds for judicial review are (perhaps increasingly) fluid and overlapping.

Illegality

In one sense it can be said that the sole ground of judicial review is that of unlawfulness. All the ways in which decisions or actions can be challenged by way of judicial review may be seen as aspects of this basic ground.

However, when the specific ground of review of illegality is referred to, a narrower meaning is being attributed to the term.

The basic principle is that public bodies may not make any decision or take any action that is not authorised by law.

Any decision or action going beyond that body’s legal powers is unlawful and may be challenged as such. This type of unlawfulness is sometimes referred to using the Latin phrase ultra vires.

Some of the specific principles underpinning this ground of review are considered in more detail in the next sections of this briefing.

The situations covered are as follows:

the decision maker's powers have been used for an improper purpose

the decision maker has fettered (i.e. closed off) their discretion

Separately, specific statutory forms of illegality, namely, breach of Convention rights, and breach of EU retained law are discussed in later sections of the briefing.

Breach of a statutory duty

A court may find an action, or failure to act, is unlawful where this is in breach of a particular duty imposed by statute.

Not all alleged breaches of statutory duties will be treated the same way by the court. The court will look at the wording used in the statute, as well as the whole scope and purpose of the Act to work out what is required and what the effect of the particular breach at issue should be.1

The courts are much more willing to enforce duties to carry out particular tasks, for example, a duty to produce a strategy or to follow a particular procedure. On these types of duties, see also the later section of the briefing on procedural impropriety or unfairness.

Errors of law and errors of fact

In some circumstances, the court will recognise that an error by a decision maker relating to the law which applies (an error of law) amounts to a ground for judicial review. Likewise, an error relating to the facts of a dispute (an error of fact) can constitute a ground for judicial review.

The rules in this area are underpinned by the fundamental principle that the courts in judicial review actions are primarily concerned with the legal validity of decisions taken, not the merits of those decisions.

Review where there is discretion

It is easy to understand that a decision that is inconsistent with the terms of a statute is subject to judicial review. However, many statutory powers and duties confer discretion. The decision maker may have a range of choices available as to what to do in the light of the facts.

The next few sub-headings of this briefing relate to the review of the discretionary element in decision making.

Breach of Convention rights

As discussed earlier in the briefing, a breach of Convention rights can form a ground for judicial review under the Human Rights Act 1998 (the Human Rights Act) and also under the Scotland Act 1998.

The Convention rights enshrined in UK domestic law are as follows:

Right to life (Article 2)

Freedom from torture and inhuman or degrading treatment (Article 3)

Freedom from slavery and forced labour (Article 4)

Right to liberty and security (Article 5)

Right to a fair trial (Article 6)

No punishment without law (Article 7)

Respect for your private life, home and correspondence (Article 8)

Freedom of thought, belief and religion (Article 9)

Freedom of expression (Article 10)

Freedom of assembly and association (Article 11)

Right to marry and start a family (Article 12)

Protection from discrimination in respect of these rights and freedoms (article 14)

Protection of property (Protocol 1, Article 1)

Right to education (Protocol 1, Article 2)

Right to elections (Protocol 1, Article 3)

Prohibition of the death penalty in peacetime (Protocol 6).

Absolute, limited and qualified rights

Not all rights in the Convention and its Protocols have the same weight. There are three broad types:

In the first place, there are absolute rights. As the name suggests, these rights, such as the protection against torture (Article 3), are absolute and cannot be removed or limited by member states.

There are also limited rights, that is to say those which can be limited under specific and finite circumstances. For example, Article 5 (right to liberty) allows for people to be imprisoned, provided there is a “lawful detention of a person after conviction by a competent court”.

Lastly there are qualified rights. These are rights which require a balance between the rights of the individual and other interests. These include the rights to: respect for private and family life (Article 8); freedom of thought, conscience and religion (Article 9); freedom of expression (Article 10); freedom of assembly and association (Article 11); peaceful enjoyment of property (Protocol 1, Article 1); and, to a degree, the right to education (Protocol 1, Article 2). See the later discussion of the principle of proportionality in the context of qualified rights.

Depending on the right in question and the specific circumstances, a policy or decision which restricts a Convention right may or may not be incompatible with the Convention.

Breach of retained EU Law

As set out earlier in the briefing, a possible (statutory) ground of judicial review is that there has been a breach of retained EU law.

A key point is not all EU law became retained EU law.

Sources of EU law which were retained

Sources of EU law which the UK has retained include those discussed earlier in the briefing, namely:

domestic legislation passed to implement EU directives and other EU law, a category known as EU-derived domestic legislationi

EU regulations, decisions and tertiary legislation, forming part of a grouping known as direct EU legislation.ii

Other sources of EU law which have been retained include:

some directly effective rights under the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Unioniii1

most general principles of EU law as they existed at IP completion dayiv

relevant case law of the Court of Justice of the European Union issued before IP completion day.v

Directly effective rights under the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union are rights which the UK Government considers are "sufficiently clear, precise and unconditional" as to confer rights directly on individuals. They can be relied on in national law without the need for implementing measures.2

Para 94 of the Explanatory Notes to the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 has a helpful (non-exhaustive) list of directly effective treaty rights.

The general principles of EU law include equal treatment and non-discrimination; legal certainty; proportionality; and the protection of legitimate expectations.

Unlike other forms of retained EU law, the general principles cannot be relied upon in a court action as a direct ground of challenge to set aside (pre-IP completion day) domestic law.vi

The principles can only be used as an aid to interpretation of other forms of retained EU law (which can form the basis of such a direct legal challenge).vii

In addition, the UK Supreme Court , the Inner House of the Court of Session, and the High Court of Justiciary (the highest criminal court in Scotland) are not bound by retained EU case law. These higher courts can choose to depart from it where they consider it right to do so.viii

Sources of EU law which were not retained

The UK is not retaining:

the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, except insofar as its rights are replicated in other parts of EU retained lawi

the legislative instruments known as EU directives themselves. (This is not to be confused with the domestic legislation implementing directives, which are retained)

as already discussed, the principle of supremacy of EU law for any domestic law passed or made on or after IP completion dayii

the rule in the Francovich case. This says that, where certain conditions are satisfied, a member state can be liable to pay financial damages where there has been a breach of EU law.iii

It is easy to get confused between the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union ('the Charter') and the well-known European Convention on Human Rights ('the Convention'). For one thing, there is an overlap in their content. However, the Charter draws on a broader range of sources than the Convention. It aims to be a very modern codification, including ‘third generation’ fundamental rights. These include those related to data protection and bioethics.

As discussed earlier, the Convention is incorporated into UK domestic law by virtue of the Human Rights Act 1998. Its status as part of UK domestic law is unaffected by Brexit, unlike the position with the Charter.

Procedural impropriety or unfairness

Decision makers must act fairly in reaching their decisions. This principle applies solely to the procedure used, as opposed to the substance of the decision reached.

Sources of procedural requirements

There are various sources of procedural requirements:

The common law, that is to say the law developed through the individual decisions of the courts, requires a fair procedure to be followed. In this context, this is sometimes referred to as the requirement to observe the principles of natural justice.

Legislation may impose a duty to follow specific procedures. However, failure by a decision maker to comply does not automatically mean that the decision which follows is invalid. The courts will take a range of factors into account in this regard.

Convention rights are significant sources of procedural requirements.

Article 2 of the ECHR imposes a specific procedural requirement. An effective official investigation is required where an individual is killed as a result of the official use of lethal force or where public authorities have failed to protect life.

Article 6 of the ECHR creates a right to a fair trial in civil and criminal matters. This Convention right has been very influential in practice.

A requirement to follow a specific procedural requirement can sometimes result from the protection of 'legitimate expectations', a topic explored in more detail later in the briefing.

The specific principles underpinning procedural fairness

The content of procedural fairness has been described by a leading textbook as a "constantly evolving"and "infinitely flexible", with its precise content depending on the subject matter of the case.1 However, this section of the briefing considers some of the specific principles associated with the general concept of procedural fairness:

Unjustified departure from legitimate expectations