National Care Service (Scotland) Bill

This briefing provides an overview of the provisions made in the National Care Service (Scotland) Bill. It also anticipates and highlights some of the areas Members might wish consider in scrutiny of the Bill at Stage 1.

Summary

The National Care Service (Scotland) Bill1 'the Bill', was introduced on 20 June 2022. The stated purpose of the Bill is to improve the quality and consistency of social services in Scotland.

The Bill is a framework bill that lays the foundations for a national care service, allowing for the substantive detail to be co-designed, chiefly with people who access support, those who deliver it and unpaid carers, later.

Framework legislation will typically provide powers to Ministers to make new laws by secondary legislation to fill in the detail of the Act at a later point. Framework legislation presents some challenges for scrutiny because of this lack of detail.

The Bill is divided into four parts:

Part 1 is divided into seven chapters and is the most substantive Part. It covers the principles of the National Care Service, Ministerial responsibility for the National Care Service, the setting up of care boards, strategic planning, powers of the Scottish Ministers to intervene, arrangements for a charter and complaints process, and the transfer of functions and staff between organisations.

Part 2 covers information sharing.

Part 3 contains provisions about reforms to the Carers (Scotland)(2016) Act 2. It also provides for the rights of care home residents in relation to visiting, makes some provision about procurement, and changes the powers of the Care Inspectorate.

Part 4 contains the Final Provisions. The Bill also contains four Schedules.

The Bill emerges from the long trajectory of efforts to integrate health and social care. Marks of these efforts, and a response to some of the problems that emerged from implementation of the Public Bodies (Joint Working) Act 2014, 3are evident in aspects of this Bill.

These problems include issues with:

clear lines of leadership and accountability

information sharing

the integrating of finances

a 'cluttered' governance and bureaucratic landscape.

The pandemic highlighted some of the pressures that are unique to care services, and prompted the government to commission an independent review of adult social care, which was chaired by Derek Feeley. This provided a substantial set of recommendations, some of which were taken forward into the proposals for a National Care Service, which covered most aspects of social services, rather than just adult social care.

Social services is a term used to cover the wide range of services that needs to be in place to enable individuals to lead a full life while being adequately supported to do so. It is important to distinguish between the two key areas of social services: first the statutory role of social work, which is about assessing need, managing risk and promoting wellbeing. And the broader term, 'social care support', which refers to the services, many of which are provided by the voluntary and private sector, to directly support people's needs and meet their desired outcomes for a full life.

The Bill's Policy Memorandum describes the breadth of remit for social services:

People may need support for many reasons, for example as a result of illness, physical disability or frailty, learning disabilities or mental health conditions, addiction or experience of homelessness. Social services also support unpaid carers in their caring role. They provide help for children and families who may need additional support, or where children are unable to live with their own families, and work with people to address offending and its causes, while effectively managing risk.

The Financial Memorandum

The Financial Memorandum (FM) reflects the Scottish Government’s best current estimate of the costs associated with the Bill, and this briefing includes detailed analysis of the FM, to help inform scrutiny by the lead committee and the Finance and Public Administration Committee.

A range of uncertainties are acknowledged in the FM, the most significant of which include:

the range of services to be transferred to the NCS

the nature of the delivery model to be introduced

the phasing of introduction of the new model

staffing requirements and the extent to which staff will transfer to new bodies

the VAT status of new bodies

the transfer of assets to new bodies and the maintenance costs associated with these assets.

As these uncertainties are resolved, the Scottish Government should be in a position to produce more refined cost estimates. However, these would not receive further scrutiny as decisions would be reflected in secondary legislation which would not have an associated FM. Similarly, any business cases or financial and regulatory impact assessments would not be subject to Parliamentary scrutiny in the same way as an FM. This leaves scope for estimated costs to change considerably without any detailed Parliamentary scrutiny, so it might be considered appropriate for updated costs to be presented to the Parliament’s Finance and Public Administration Committee as the Bill progresses through its Parliamentary stages and as further decisions are reached on the scope and nature of the NCS.

Local government

The Bill sets out powers for the Scottish Ministers to transfer community health, social care, and social work functions to the NCS by secondary legislation. Such transfers will have major budgetary, staffing, policy and governance implications for local authorities. A dedicated section of the briefing discusses these issues in detail.

Children's services

The Bill would also enable Scottish Ministers to include children’s services in the National Care Service in the future. To this end, section 27 of the Bill would give Ministers powers to remove a wide range of children’s services functions from local authorities by means of regulations. Again, a dedicated section of the briefing covers these issues in detail.

Introduction

The National Care Service (Scotland) Bill1 'the Bill', was introduced on 20 June 2022. The stated purpose of the Bill is to improve the quality and consistency of social services in Scotland.

The Policy Memorandum 2sets out a Vision for the National Care Service, but says that the Bill is only one element that will support this Vision:

The Scottish Government is determined that social care and social work services should deliver consistent, high quality support to every person who needs it, across Scotland. Those services must have human rights at the heart of the system, enabling people to take their full part in society and live their lives as they want to, while keeping individuals and communities safe. This Bill is one element that will support the delivery of this vision.

Social Care Minister Kevin Stewart said:

One of the key benefits of a National Care Service will be to ensure our social care and social work workforce are valued, and that unpaid carers get the recognition they deserve.

When this Bill passes we will be able to have the new National Care Service established by the end of this parliament. In the interim we will continue to take steps to improve outcomes for people accessing care - working with key partners, including local government, and investing in the people who deliver community health and social care and support.

The Bill is a framework bill that lays the foundations for a national care service, allowing for the substantive detail to be co-designed, chiefly with people who access support, those who deliver it and unpaid carers, later. Consultation on this detail has started already.3. This detail would be delivered later, in a range of secondary legislation, once the Bill is passed.

Framework bills, also referred to as ‘skeleton bills’ set out principles for a policy but do not provide substantial detail on how that policy will be given practical effect.

Such bills provide broad powers to fill in the detail at a later point, most often by delegated (secondary) legislation known as Scottish Statutory Instruments (SSIs).

In the Cabinet Office Guide to Making Legislation, paragraph 15.17 explains what a framework bill is:

A Bill that leaves the substance, or significant aspects, of the policy to delegated legislation is sometimes called a framework Bill. It might amount to a series of powers providing for a wide range of things that could be done with the detail on what will be done, left to be set out in the regulations.

Overview of the Bill

The Bill is divided into four parts. Part 1 is divided into seven chapters and is the most substantive Part. It covers the principles of the National Care Service, Ministerial responsibility for the National Care Service, the setting up of care boards, strategic planning, powers of the Scottish Ministers to intervene, arrangements for a charter and complaints process, and the transfer of functions and staff between organisations. Part 2 covers information sharing. Part 3 contains provisions about reforms to the Carers (Scotland)(2016) Act 1. It also provides for the rights of care home residents in relation to visiting, makes some provision about procurement, and changes the powers of the Care Inspectorate. Part 4 contains the Final Provisions. The Bill also contains four Schedules which would be introduced by sections 4, 27 and 34 of the Bill.

Part 1 - The National Care Service

Part 1 is divided into seven chapters, described in more detail below.

Chapter 1 - sets out the principles of the National Care Service (NCS), establishes that the Scottish Ministers would be responsible for the NCS, in a similar way to the NHS, and that care boards would be established. Local care boards would cover every part of Scotland. Special care boards, with national responsibilities could also be established. This chapter also clearly sets out that Ministers may fund the care boards and act as their financial guarantor. There is nothing in the Bill about repealing legislation (The Public Bodies (Joint Working) Scotland Act 2014), that established integration authorities. This means that integration authorities and care boards could be operating in parallel. If omitting this from the Bill was an oversight, it remains that there could be uncertainty during the scrutiny of the Bill.

Chapter 2 - would require the Scottish Ministers, if they are delivering or arranging services directly, to have a strategic plan, as well as the institutions of the national care service - care boards. Care boards would have to consult with community planning partners on a draft, then the public, and finally seek approval from the Scottish Ministers, who will have the powers to make changes to the plans. Strategic plans must include ethical commissioning strategies, which set out how services will be provided in a way that reflects the NCS Principles.

Chapter 3 - would require Scottish Ministers to produce a NCS charter of rights and responsibilities and to make it publicly available so people can understand what they can expect from the NCS, and any responsibilities people using the NCS might have. This is similar to the premise of the NHS charter in Scotland. Work on this can start before the NCS is operational.

Ministers could make regulations about independent advocacy services linked to NCS services.

Ministers would have to provide a central service for receiving and passing on complaints. They could make provision for how complaints will be handled, and by which body.

Chapter 4 - would place care boards under a legal duty to comply with any direction (section 16) issued by the Scottish Ministers. Ministers would have the power to disband a board completely (section 17), if they deemed that the board had failed to carry out any of its functions. This could be done following an inquiry, and the Scottish Ministers could appoint someone (section 19) to take on the functions of the board following a service failure, or risk of one. This failure could include failing to follow a direction from the Scottish Ministers. The removal would come about through (laid-only) regulations.

In an emergency, (section 18) the government would be able to appoint, through directions, someone to take over the running of the board if they think they other person would be more effective in performing a function or functions.

Scottish Ministers would also have powers to intervene in a provider’s operation, including appointing someone to take control of the operations, subject to a court’s authorisation of an emergency intervention order. However, the court would have discretion to amend the terms of the order, such as taking control of the operations. The order could be in place for a maximum of 12 months, with the option of a single six month extension.

Chapter 5 - allows for the government and care boards to conduct research, provide and fund training, to provide funding for other activities and to purchase land compulsorily to carry out a function of the national care service or a care board.

Chapter 6 - would enable Ministers to make regulations to transfer functions from local authorities and health boards to themselves, as having responsibility for the national service, or to care boards. Functions that can be transferred from local authorities are only those related to specific social work-linked legislation which is listed in schedule 3. These regulations would amend the relevant Act. While these regulations are laid before Parliament and considered by the relevant Committee, they cannot be amended, only agreed to or not.

However, in relation to transferring children's and justice services into the National Care Service (section 30), the government would have to consult publicly. In addition, if the regulations are laid before Parliament, they must include a summary of the consultation process and of the responses received.

Also in this chapter, the Scottish Ministers could have powers via regulations to redistribute functions from local to special care boards, or to themselves, and vice versa.

There would be a power to make regulations to transfer staff, property and liabilities from one organisation to another, but staff could not be transferred from a health board.

Chapter 7 incorporates schedule 4 into the Bill, and describes what the National Care Service is. That is, not a single entity, but a term encompassing care boards and powers or duties of the Scottish Ministers coming from regulations that arise from the Bill.

Part 2 - Health and social care information

Part 2 of the Bill would give powers to the Government to make regulations to set up a scheme so that information could be shared to improve effectiveness of services. This would be governed by a proposed information standard to ensure that data would be recorded and handled consistently.

Part 3 - Reforms connected to delivery and regulation of care

Part 3 of the Bill would change the Carers (Scotland) Act 2016 1. A new duty would be placed on local authorities to provide the support necessary to enable an unpaid adult or young carer to take ‘sufficient breaks’ from caring for someone. This duty, according to the Explanatory Notes, could not be subject to local or national eligibility criteria.

In this Part too, is the incorporation of "Anne’s Law". These provisions seek to ensure that care home residents would be able to receive visits or make visits to loved ones.

Ministers would be required to issue so called 'Visiting Directions', following consultation with Public Health Scotland, to care home providers about visits to or by care home residents. In effect, the direction would remove variation across the country and between providers. However, a direction could be varied or revoked.

In this Part too is the proposed insertion of a provision that would enable Ministers to limit the types of organisations that can bid for selected contracts to provide services to the NCS . In 2015, Article 77 of the EU directive 2014/24/EU 2allowed this, but at the time it wasn’t deemed necessary to include it in the Public Contracts (Scotland) Regulations 2015 3. The current definition of the type of organisations that could bid for such contracts are those in mutual ownership or that involve employee participation, but Ministers could amend this to include voluntary and third sector organisations

Section 42 of the Bill would modify section 64 of the Public Services Reform (Scotland) Act 2010 4. This change would allow the Care Inspectorate (CI), formally known as Social Care and Social Work Improvement Scotland - SCSWIS), to move to cancel a failing care provider's registration without first issuing an improvement notice, allowing time for improvements in service to be put in place. The CI would be able to move directly to applying to the Sheriff Court to cancel the registration. The 2010 Act makes it a criminal offence to provide a care service without being registered with the Care Inspectorate.

Part 4 - Final provisions and schedules

Section 44 defines 'health board' and 'special health board'. Sections 45 and 46 relate to the powers to make regulations and to amend existing legislation through either negative or affirmative procedures. Commencement of all but this part of the Bill would be through regulations.

Schedule 1 covers the constitution and operation of care boards and how members would be appointed. The chair and ordinary members would be appointed by the Scottish Ministers according to regulations they may make. The Ministers could also remove a board member if they deemed them to be unfit or unable to perform the members' functions.

The Scottish Ministers would also appoint the chief executive of a care board, and the care board could appoint staff under terms and conditions set by the Scottish Ministers.

Schedule 2 details the existing legislation relevant to the responsibilities of public bodies, that would apply to care boards.

Schedule 3 lists the Acts that would cover the transfer of local authority functions to care boards.

Schedule 4 covers modifications required to the Local Government (Scotland)Act 1973 to allow a legal basis for a local authority continuing to provide a service and to act as a contractor. The Public Services Reform (Scotland) Act 2010 would also be modified so that the the restriction to transfer health board staff (by transferring a function) to a NCS institution could not be bypassed using the 2010 Act. Paragraph 3 of schedule 4 amends section 14 of the 2010 Act.1

Framework legislation - issues and implications

While framework or 'skeleton' legislation is not new, the challenges and particularities of it with regard to scrutiny are worthy of some attention. The next sections explain what framework legislation is and consider some of the scrutiny challenges it presents.

What is framework legislation?

According to a 2009 report entitled 'What happened next? A study of Post-Implementation Reviews of secondary legislation' by the House of Lords Merits of Statutory Instruments Committee:

“Framework bills” (or “skeleton bills” as the Delegated Powers and Regulatory Reform Committee refers to them) set out the principles of the legislation for scrutiny but rarely provide substantial information about how those principles will apply in practical policy terms.

House of Lords Merits of Statutory Instruments Committee. (2009, November 12). What happened next? A study of Post-Implementation Reviews of secondary legislation . Retrieved from https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld200809/ldselect/ldmerit/180/180.pdf [accessed 23 September 2022]

Framework legislation will typically provide powers to Ministers to make new laws by secondary legislation to fill in the detail of the Act at a later point. The Cabinet Office ‘Guide to Making Legislation’ states:

A bill or provision that consists primarily of powers and leaves the substance of the policy, or significant aspects of it, to delegated legislation is sometimes called a framework (or ‘skeleton’) bill or provision.

The Hansard Society. (2021, November). Delegated Legislation: the problems with the process. Retrieved from https://assets.ctfassets.net/n4ncz0i02v4l/2e2hncTHupRnvN4trkguJ6/34ab2e41faa8254985034fab5c466a5c/Charge_Sheet_FINAL_2_Nov21.pdf [accessed September 2022]

The House of Lords Delegated Powers and Regulatory Reform Committee, which considers bills that give powers to make secondary legislation, states:

A bill is, in effect, a skeleton bill or a bill contains skeleton clauses where the provision on the face of the bill is so insubstantial that the real operation of the Act, or sections of an Act, would be entirely by the regulations or orders made under it.

UK Parliament, House of Lords Delegated Powers and Regulatory Reform Committee. (2021, November). Guidance for Departments. Retrieved from https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/8225/documents/84262/default/#page=5 [accessed September 2022]

The Hansard Society describes skeleton bills or bills with skeleton clauses as bills “that contain powers rather than policy – reflecting administrative convenience, incomplete policy development or Ministers’ wish for the greatest freedom to act at a later date.”2

Scrutiny challenge

Since framework bills do not include full details on how a policy will be implemented, legislatures are unable to scrutinise such details at the time of considering a bill. The House of Lord’s Delegated Powers and Regulatory Reform Committee (DPRRC) published a report in 2021 1in which it states that:

far too often primary legislation has been stripped out by skeleton provisions and the inappropriate use of wide delegated powers. This means that it is increasingly difficult for Parliament to understand what legislation will mean in practice and to challenge its potential consequences on people affected by it in their daily lives.

There is no question that secondary legislation is a necessity. Without it, legislatures would be swamped with needing to pass primary legislation for small changes and updates to existing law. The House of Lords Delegated Powers and Regulatory Reform Committee's 2021 report on secondary legislation 'Democracy Denied? The urgent need to rebalance power between Parliament and the Executive' articulates the case for secondary legislation as follows:

While the delegation of powers can be controversial, the need for delegated legislation has long been widely accepted. Erskine May, the authoritative text on parliamentary procedure, refers to the advantages arising from its “speed, flexibility and adaptability”, and the first report of the Delegated Powers Scrutiny Committee, published in March 1993, began:

“Parliament recognises the need to delegate some legislative powers. The ever-increasing mass of detail in statutory instruments could not be scrutinised by Parliament if it formed part of primary legislation. The need to change detailed provisions from time to time would place impossible burdens on Parliament if the changes always required the introduction of new legislation. The argument is not whether delegation is ever justified but what criteria can be used in determining whether particular proposals for delegation are acceptable.”

Secondary legislation can be passed more quickly than primary legislation, because it receives more limited parliamentary scrutiny. It cannot, for example, be amended - simply accepted or rejected. This limits the extent to which a legislature can shape secondary legislation.

Secondary legislation is subject to different kinds of laying procedures. The different procedures allow for different levels of scrutiny. Typically, Scottish Statutory Instruments (the most common form of secondary legislation) are laid before the Scottish Parliament subject one of the following procedures:

affirmative

negative

no procedure or laid only

provisional affirmative

super-affirmative.

The NCS Bill would provide Ministers with a number of powers to make secondary legislation. In each case the procedure is specified as either affirmative or negative. The parliamentary process for each procedure is explained on the Scottish Parliament's website. See also section on the role of the Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee.

Given this, it is important that, when scrutinising any primary legislation granting delegated powers, a legislature is content not only with the powers themselves, but also with the procedure which will apply to any future secondary legislation.

The Scottish Parliament’s Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee conducted an inquiry from November 2021 to February 2022 into the "made affirmative procedure" (one of the procedures secondary legislation can be subject to) at the Scottish Parliament. The made affirmative procedure was widely used during the COVID-19 pandemic. In a debate in January 2022 that formed part of this inquiry, Craig Hoy MSP asked John Swinney, Deputy First Minister:

Do you think that the increased use of such legislation [skeleton legislation and the delegated legislation that stems from it] is consistent with the need for parliamentary scrutiny and accountability?

John Swinney responded:

[…], it is important that we wrestle with those questions on a case-by-case basis. When legislation is being considered, it is an absolute requirement that, for anything that might be described as skeleton legislation to be put in place, a clear argument must be made, and clear justification provided, to satisfy the test of parliamentary scrutiny.

What makes the National Care Service Bill framework legislation?

The NCS Bill contains substantive provisions that would give powers to Scottish Ministers to make secondary legislation. The policy memorandum1, published alongside the NCS Bill states:

The Scottish Government is committed to engaging with people with experience to codesign the detail of the new system, to finalise new structures and approaches to minimise the historic gap between legislative intent and delivery. For that reason, the bill creates a framework for the NCS, but leaves space for more decisions to be made at later stages through co-design with those who have lived experience of the social care system, and flexibility for the service to develop and evolve over time. Some of those future decisions will be implemented through secondary legislation, others will be for policy and practice.

The Scottish Government has also provided a Delegated Powers Memorandum, 1which explains the provisions in the Bill that give Ministers powers to make secondary legislation. This document sets out a rationale for why the Scottish Government thinks those powers and the parliamentary procedures to which the Bill proposes any secondary legislation would be subject to are appropriate.

The role of the Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee

The standing orders of the Scottish Parliament set out the role of the Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee. In general terms, the DPLRC carries out legal and technical checks on legislation. The Committee considers, for example, whether delegated powers in primary legislation (i.e. those in a bill) are appropriate and it also checks secondary legislation for legal and technical accuracy. The Committee does not consider the policy context of legislation, nor the impact the legislation might have on policy and practice. The remit of the Committee is available on the Scottish Parliament website which explains its role in more detail.

Rule 6.11 of the Scottish Parliament's Standing Orders sets the remit for DPLRC and specifies that, in relation to delegated powers proposed in primary legislation, the Committee considers and reports on:

"(b) proposed powers to make subordinate legislation in particular Bills or other proposed legislation;

(c) general questions relating to powers to make subordinate legislation;

(d) whether any proposed delegated powers in particular Bills or other legislation should be expressed as a power to make subordinate legislation"

The Scottish Parliament. (2022, April 1). Standing Orders Gnàth-riaghailtean. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/about/how-parliament-works/parliament-rules-and-guidance/-/media/5d38f9e0016f40f98a27181a9345e3d1.ashx [accessed 23 September 2022]

This means that it is the DPLRC's role to consider the appropriateness of the delegation of powers in the NCS Bill as well as the suitability of the proposed procedures (for example affirmative or negative) for any secondary legislation made under its provisions in the future.

Section 46 of the Bill specifies the procedures which would apply to any future secondary legislation made under those provisions of the Bill which contain regulation making powers.

Background to the Bill

No legislation emerges from a vacuum. The National Care Service Bill is no exception. It emerges from the long trajectory of efforts to integrate health and social care. Marks of these efforts, and a response to some of the problems that emerged from implementation of the Public Bodies (Joint Working) Act 2014, 1are evident in aspects of this Bill. These problems include issues with:

clear lines of leadership and accountability

information sharing

the integrating of finances

a 'cluttered' governance and bureaucratic landscape.

The following sections provide a brief overview of some of the main developments that have contributed to the introduction of this legislation.

Health and social care integration

The Scottish Parliament's respective health and public audit committees, along with Audit Scotland, have tracked the progress of the integration of health and social care since 2014.

This graphic from Audit Scotland's 2018 Report on the progress of integration highlights where there were issues and what was required for success.

The way health and social care services are planned and delivered across Scotland was changed by the Public Bodies (Joint Working) (Scotland) Act 20141(‘2014 Act’). Local authorities and NHS boards are required by law to work together to plan and deliver adult community health and social care services, including services for older people.

The 2014 Act 1had the aim of ensuring health and social care services are well integrated, so that people receive the care they need at the right time and in the right setting, with a focus on community-based, preventative care.

The new bodies, 31 integration authorities (IAs), which were mostly established as integration joint boards (IJBs), were created as separate legal entities, responsible for commissioning and a wide range of health and social care services across the partnership area. Highland is the only area to adopt a “lead agency” arrangement, with the chief executive of NHS Highland having responsibility for adult health and social care services and the chief executive of Highland Council having responsibility for for children's health and social care services. This means there is no separate integration joint board, nor a chief officer or chief finance officer.

Each IA differs in terms of the services they are responsible for and the local needs and pressures they face. At a minimum, IAs need to include governance, planning and resourcing of social care, primary and community healthcare and unscheduled hospital care for adults. The IAs are responsible for both the ‘front’ and ‘back doors’ of secondary care, and data from these – A&E and discharge hubs - are used as indicators to measure the success of integration.

In some areas, partners have also integrated children’s services and social work criminal justice services. Highland Lead Agency, Dumfries and Galloway IJB, and Argyll and Bute IJB have also integrated planned acute health services. The 2014 Act was intended to shift resources away from acute hospital care towards preventative and community-based services, hence the inclusion of unscheduled hospital care and discharge being included in integration schemes.

The website Health and Social Care Scotland provides links to information on all 30 IJBs (health and social care partnerships) , and to each IJB’s Integration Scheme, Strategic Plan, Board membership and Annual Report. These are the core documents relating to each IJBs’ performance and strategy.

Audit Scotland scrutiny of health and social care integration

Audit Scotland has tracked the progress of integration, within the context of the transformation of health and social care, and efforts to ensure services are better co-ordinated and more collaborative, fulfilling the ambition of the 2014 Act.

The last time Audit Scotland looked in detail at integration was in its Update in 20181. However, since then it has provided some insights and recommendations in its overview of Local Government in Scotland 2019/20 2and the Accounts Commission published a Financial Analysis of Integration Joint Boards, 2020/21 in June 2022 3.

The pandemic altered how all public services and third sector services operate, and inevitably interrupted the progress of integration. The Audit Scotland Update might appear somewhat out of date, but prior to the pandemic, this report provided a focus for improvements to integration arrangements.

In 2018, Audit Scotland made several recommendations for actions they felt were required to make integration a success. It said that IAs, councils, NHS boards, the Scottish Government and COSLA all needed to work together, to achieve the following (summarised):

Commitment to collaborative leadership and building relationships.

Effective strategic planning for improvement in IAs and government departments.

Integrated finances and financial planning, and centrally funding innovation.

Agreed governance and accountability arrangements.

Ability and willingness to share information and data.

Meaningful and sustained engagement with local communities.

The Overview of local government 2019/20 2 included IJBs and in its key messages, said the following:

Audit Scotland

A majority of IJBs (22) struggled to achieve break-even in 2019/20 and many received year-end funding from partners.

Total mobilisation costs for Health and Social Care Partnerships for 2020/21 due to Covid-19 are estimated as £422 million. It is not yet clear whether the Scottish Government is to fund all of these costs.

Instability of leadership continues to be a challenge for IJBs. There were changes in chief officer at 12 IJBs in 2019/20. (This is significant because the only staff members appointed to IJBs are the Chief Officer and the Chief Finance Officer).

The most recent audit of IJBs was carried out by the Accounts Commission and published in June 2022. The key messages indicate a mixed picture, as does a comparison of the 30 IJBs. Overall funding for IJBs increased to £10.6 billion in 2020-21, largely a reflection of an increase in funding made available during the pandemic. As a consequence, all IJBs achieved a year-end surplus. Unspent COVID-19 funding and a late allocation for a number of areas accounts for a tripling of total reserves.

The audit also found that, while the budget gap has decreased, recurring savings need to be identified to achieve medium- and longer-term financial sustainability:

IJBs face significant financial sustainability risks exacerbated by uncertainty of future funding, rising demand and the potential impact of a national care service. The non-recurring nature of some funding streams, and the reserves held by IJBs, presents a significant challenge to IJBs. It is essential that IJBs identify significant recurring savings to maintain current levels of service provision at the same time as transforming the way services are delivered.

Accounts Commission

Ministerial Strategic Group for Health and Community Care

Although established in 2008 as a forum for health and social care leaders, since 2016 the Ministerial Strategic Group for Health and Community Care (MSG) has worked to support the process of integration. The group disbanded early in 2020 as the focus shifted to managing the COVID-19 pandemic. It published its final review of progress of integration in February 2019. Its recommendations and observations aligned with the Audit Scotland report, Health and social care integration:update on progress, published in November 2018 1. This was followed up with an update on progress, sent to the Session 5 Health and Sport Committee in response to its pre-budget report in February 2021. However, it is the Group’s main, February 2019, report that most succinctly highlights the challenges integration faced, and sets out a number of time-bound proposals against Audit Scotland’s recommendations.

Scottish Parliament scrutiny of social care

In 2019-20, the Health and Sport Committee conducted an inquiry into social care and support for adults over 18 years. The decision to hold the inquiry was based on closures of residential care facilities, funding issues and withdrawals from contracts with local authorities.

The Committee wanted to explore the future delivery of social care in Scotland and what is required to meet future needs.

The Committee held an event, Scotland 2030: A Sustainable Future for Social Care for Older People, on 16 November 2018, in collaboration with Scotland’s Futures Forum, to consider the future of social care for older people in Scotland. The event considered the general proposition of how social care would look (and be financed) in 2030.

The Scottish Government Adult Social Care Reform Programme had been working to reform social care in Scotland. The inquiry was not intended to replicate that work, but to instead explore the future delivery of social care in Scotland and what would be required to meet future needs.

The initial inquiry into social care was to be a forward-looking strategic approach designed to encourage an exploration of how social care can be co-ordinated, commissioned and funded differently in the future. The written submissions can be found via this link.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, scrutiny of social care was paused. The pandemic brought several issues to the fore in relation to care homes and wider social care. On 4 June 2020, the Committee took evidence from the Cabinet Secretary for Health and Sport on the issue of COVID-19 in care homes. It was also forced to revise its approach to the inquiry, due to the restrictions in place, and decided to consider what early lessons could be learned from the impact of the pandemic. A limited number of evidence sessions were held in the autumn of 2020.

Summaries of evidence from the initial social care inquiry, and the session exploring the impact of COVID-19 on care homes, are available:

Initial social care inquiry responses from members of the public

COVID-19 care home inquiry responses from care home managers

COVID-19 care home inquiry responses from public, staff and relatives.

During August and September 2020 the Committee carried out a further online survey to receive the views of those who receive, or provide, care and support at home:

The Committee published its report on 10 February 2021, a week after the 'Feeley Review', the Independent Review of Adult Social Care' was published:

A response to the report was received by the committee from the then Cabinet Secretary for Health and Sport on 17 March 2021:

The pandemic effect

A more recent, shorter trajectory, comes from the pandemic. There were a large number of deaths in care homes in the early weeks of the pandemic. There were 9.2 deaths in the care home sector for every 100 places.1. However, a quarter of these deaths in older people's care homes occurred in just 26, or 3%, of homes. 2. At April 2021, deaths in care homes accounted for around a third of all COVID-19 deaths in Scotland.3.

The deaths in the early weeks of the pandemic aroused a high level of media attention in the middle of 2020.

In addition, many care services in the community ceased completely for a time. People in care homes were no longer able to see loved ones or leave the home they were in. Some were in isolation when infection in a care home was detected.

The vulnerability of the care sector and the people who relied on it was exposed during the pandemic in terms of health protection, access to Personal Protective Equipment, resilience and the human rights of care home residents, as vulnerable people were effectively trapped in their homes or care homes.

The Health and Sport Committee adapted its inquiry into social care to examine some of the live issues at the time.4

In its Programme for Government 5in September 2020, Ministers undertook to:

Immediately establish an independent review of adult social care. This will examine how adult social care can most effectively be reformed to deliver a national approach to care and support services. This will include consideration of a national care service.

Independent Review of Adult Social Care

The conclusions of the independent review became the so-called 'Feeley Report', or the Independent Review of Adult Social Care (IRASC)1. Although the focus was on adult social care, the Review made links to other national reviews, including the Independent Care Review – The Promise 2, and The Review of Mental Health Law 3. It also established links to the Fair Work Group and the National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership.

The Feeley Report contained a chapter of 53 recommendations, including the establishment of a national care service, under a number of headings:

a human rights based approach must be embedded in social care practice

unpaid carers need better more consistent support

the case for a national care service and how it should work

closing the implementation gap - a new approach to improving outcomes

models of care

commissioning for public good

fair work

finance.

Scottish Government consultation on a national care service - areas for further scrutiny

Following publication of the Feeley Report, the Scottish Government issued a consultation on proposed reforms to "start the discussion and debate about what changes should be made to achieve better outcomes for people"(p8)1.

The responses were analysed and a report was published in February 20222. The process attracted some criticism: the questionnaire being too long, too short a timescale for responding, a lack of detail, and leading questions.

Given the potential impact of the Bill on the functions of local government, COSLA were disappointed that their submission, representing 32 local authorities was weighted as a single response in the analysis.

Our members are political leaders throughout diverse communities across Scotland with a distinct knowledge and understanding of their local areas. For this reason, we are disappointed that COSLA’s response - amongst many others – has been weighted as a single response...

...What Scotland needs now is a clear roadmap that tells us what the proposed National Care Service will look like, how it will go about achieving meaningful and evidence-based reform, and – crucially – what this means for both the people who use social care and our workforce. There is also a concerning lack of any detail regarding the cost of a National Care Service and how it will be funded. This must be carefully and robustly laid out so that Scotland can have confidence in the affordability and sustainability of the proposals.

We simply cannot wait the four or five years until a National Care Service is in place, when we can work together to bring about meaningful change now.

COSLA

According to the analysis, the main themes emerging from the proposal to set up a national care service were:

the need to avoid adding additional bureaucracy

maintaining local accountability

role of local authorities

challenges in remote and rural areas

suggestion for inclusion of housing, education and transport.

Other themes to emerge included:

the need for more detail on the proposals to inform the debate

the need for more detail about the costs of designing and implementing an NCS

transition risks and centralisation

the impact on local authority workforces

localism and local accountability

the needs of remote and rural areas

human rights and equality issues

the extent of the proposed NCS

the delivery of services under the NCS.

Scottish Parliament consultation for Stage 1 scrutiny

The Scottish Parliament launched its call for views on 8 July 2022, following the introduction of the National Care Service (Scotland) Bill1 on 20 June 2022. It closed on 2 September 2022. It comprised two parts:an opportunity to submit a detailed response via 'Citizen Space', as well as an opportunity to join a less formal engagement process via 'Your Priorities'. The detailed questionnaire contained both general questions about the Bill as well as questions on the specific provisions and sections. The Your Priorities pages offer people the opportunity to respond to themes, to comment and to create their own. The front page of this site has two pinned starting points: 'Views on the Bill' and 'Your questions, hopes and concerns about the Bill'.

The Health, Social Care and Sport Committee clerking team led three sessions with stakeholders during the month of August to discuss the Committee’s scrutiny of the Bill. The following organisations were represented:

Session 1: Voluntary Health Scotland Policy Officer’s Network (the following organisations signed up to the event – though not all necessarily attended):

Samaritans

MND Scotland

Paths for All

See Me

British Red Cross

Care Inspectorate

Kidney Research UK

Generations Working Together

Chest Heart and Stroke Scotland

Age Scotland

Eat Well Age Well

LGBT Health.

Session 2: Inclusion Scotland network

Session 3: Scottish Federation of Housing Associations network & the Housing Support Enabling Unit. The Scottish Government bill team also attended this session.

Specific areas for scrutiny

The following sections highlight particular aspects of the Bill and issues or areas of focus. The Health, Social Care and Sport Committee is the lead committee scrutinising the Bill, and will consider all aspects of the Bill, in collaboration with the two secondary committees: Education, Children and Young People Committee and the Local Government, Housing and Planning Committee. The Finance and Public Administration Committee will scrutinise the Financial Memorandum. The Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee will scrutinise the Delegated Powers Memorandum, considering the technical aspects and details of the legislation.

A summary of evidence from the Parliament's Call for Views on the Bill will be produced to support scrutiny.

Financial Memorandum

The Financial Memorandum (FM) for the National Care Service (Scotland) Bill (“the Bill”) sets out the estimated costs associated with the measures proposed by the draft legislation.

What costs does the Financial memorandum cover?

Estimated costs are set out in relation to the various aspects of the Bill as follows:

establishment of a National Care Service

establishment of Care Boards

health and social care information

right to breaks from caring

“Anne’s Law” – visits to or by care home residents

changes to powers and functions of the Care Inspectorate.

In line with standard practice for FMs, the costs are set out separately in relation to:

The Scottish Administration

Local Authorities

Health Boards

Other public bodies

Businesses and third sector organisations

Individuals.

At the outset, it is important to note that the purpose of an FM is to provide costs relating to the implementation of the associated legislation. An FM is not intended to consider the wider policy environment in which the Bill sits; it only considers the direct costs of the legislation. The Scottish Government has a programme of health and social care reform that includes a range of measures that are not covered by this Bill and, as such, do not feature in the costings.

As explained in the FM, commitments that are not covered by the Bill’s provisions (and so are not covered by the FM) include:

To increase pay and improve terms and conditions for adult social care staff in commissioned services.

To bring Free Personal Nursing Care rates in line with National Care Home Contract rates.

To remove charging for non-residential care.

To increase investment in social work services.

To increase provision of services focusing on early intervention and prevention.

To invest in data and digital solutions to improve social care support.

These measures do not require primary legislation. The FM notes that:

these are policy decisions to be made or sustained under the new framework, not necessary consequences of the Bill provisions.

As such, the FM reflects the costs associated with the primary legislation that has been introduced. The Bill documentation also indicates a number of areas where further changes and decisions will be implemented via secondary legislation e.g. regulations. It is worth noting, and as explained above, the costs of changes introduced via secondary legislation would not normally receive the same level of Parliamentary scrutiny as changes that are introduced via primary legislation.

Overall costs and general considerations

The total costs of the Bill over the five year period 2022-21 to 2026-27 are estimated at between £644 million and £1,261 million.

A breakdown of these estimated costs by year and according to the part of the Bill to which they relate is shown in Table 1. The FM provides a range of estimates; both lower end and upper end estimates are shown in the table.

| £ million | 2022-23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2026-27 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total - all provisions | ||||||

| Total estimated costs - lower end | 24 | 63 | 84 | 232 | 241 | |

| Total estimated costs - upper end | 36 | 95 | 126 | 477 | 527 | |

| Establishment and running of NCS national organisation | ||||||

| Total estimated costs - lower end | 24 | 60 | 72 | 92 | 83 | |

| Total estimated costs - upper end | 36 | 90 | 108 | 138 | 124 | |

| Establishment and running of care boards | ||||||

| Total estimated costs - lower end | - | 4 | 12 | 132 | 142 | |

| Total estimated costs - upper end | - | 6 | 18 | 326 | 376 | |

| Rights to breaks from caring | ||||||

| Total estimated costs - lower end | - | - | - | 8 | 16 | |

| Total estimated costs - upper end | - | - | - | 13 | 27 | |

| Anne's Law | ||||||

| Total estimated costs | 0.186 | 0.090 | - | - | - | |

Scope of care boards

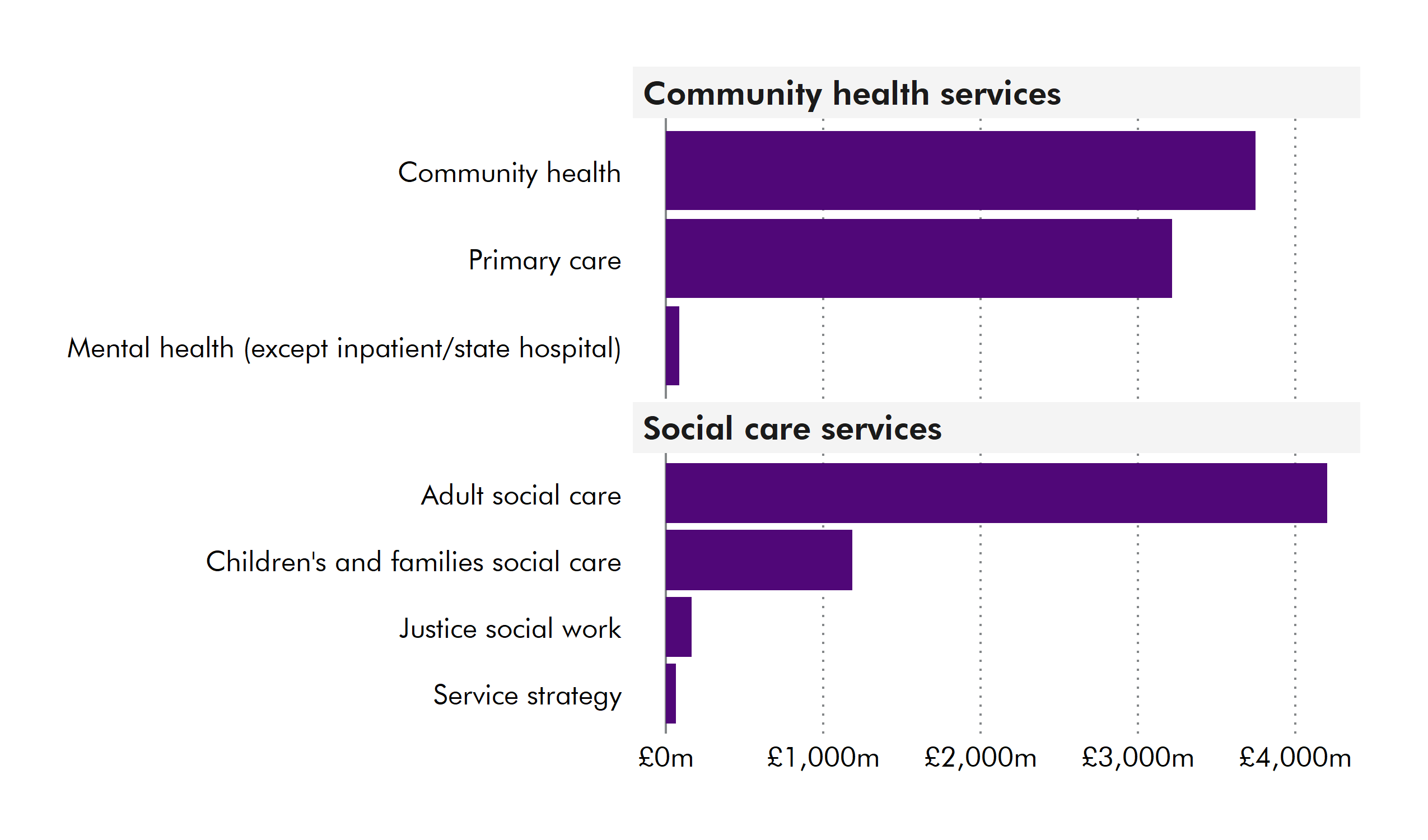

The wide range in the estimated costs reflects uncertainties over the costs of establishing and running the national NCS organisation and the associated care boards. This, in turn, reflects uncertainties around the exact format and responsibilities of these organisations. According to the FM, the lower end of the cost estimates reflects a scenario in which only adult social care services are transferred, while the upper end of the cost estimates would reflect a scenario in which adult social care and social work, children’s social work and social care, and justice social work are all transferred.

As shown in Figure 1, according to data presented in the FM, adult social care accounts for estimated expenditure of £4.2 billion in 2022-23, which is three-quarters of the total £5.6 billion spend on social care services. A further £7 billion of expenditure is accounted for by community health services that could potentially be transferred to care boards, although the FM notes that the scope of health functions that might be transferred to care boards has yet to be determined.

The FM notes that these expenditure figures are illustrative and intended to give a scale of the services in scope and provide context for the policy proposals. They are not direct costs associated with the Bill. The expenditure estimates are projected forward using inflation plus a 3% uplift to reflect other pressures, such as pay, prescribing and energy prices. The estimates for future years project forwards based on existing expenditure profiles and do not reflect any policy decisions e.g. to increasing spend on adult social care. Furthermore, in the current volatile inflation environment, the projections for future years could look quite different if revised to reflect the latest inflation data, so may be of limited value other than for reflecting the relative scale of expenditure on different service areas.

Tracking spend on social care is not straightforward1under the current funding arrangements, so it will be important to get a clear baseline position on services being transferred to the NCS to support future monitoring of spend in this area. Following the Police and Fire Reform (Scotland) Act 2012, there have been significant challenges in tracking local government budgets and expenditure on a comparable basis.

Alternative delivery models

As noted in the FM and elsewhere in the Bill documents, delivery of services might take a number of formats, with decisions to be taken locally following options appraisals and consultation with stakeholders. For example, where services are currently provided in-house by local authorities, this arrangement might continue through a procurement arrangement. Alternatively, care boards may take on direct delivery of services, with staff transferring to care boards. It is also not yet determined which functions might be delivered at national level by the NCS national organisation, rather than at local level.

Decisions relating to the delivery model will have a significant bearing on costs and this is reflected in the broad range of cost estimates.

Phasing of transfer of functions

The FM highlights that transfer of functions might take place immediately on creation of the care boards, or might be phased over a number of years. The FM acknowledges that “a phased approach may result in a period of double running costs or transfer costs in addition to the costs set out [in the FM]”. However, no indication is given of the potential scale of such double running costs or further potential costs.

Establishment of the National Care Service - national organisation

The FM notes that, at national level, there will not be a new body. The new responsibilities for social work and social care will be handled by Scottish Government staff reporting directly to Scottish Ministers, in a similar way to the current Health Directorates of the Scottish Government that oversee the NHS in Scotland. The proposed National Social Work Agency will be set up as a unit within the NCS.

The NCS is to be established by 2025-26 and the FM notes that preparatory work is already underway, including:

policy development and co-design

programme and project management (PPM)

recruitment costs

financial forecasting

data and digital discovery work

workforce planning.

Both staff and non-staff costs are identified and these are shown both for the establishment phase and the operational phase. For the first planned year of operation of the NCS (2025-26), there are both establishment phase costs and running costs.

Estimated costs for establishment of the NCS are summarised in Table 2. These costs fall entirely to the Scottish Administration and cover both the establishment phase (2022-23 to 2025-26) and the operational phase (from 2025-26). The financial year 2025-26 incorporates elements of both establishment and running costs. A range of estimates is given, with the table below showing both the lower end and upper end estimates.

| £ million | 2022-23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2026-27 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower end estimates | |||||

| Staff | 18 | 47 | 48 | 64 | 60 |

| Systems and IT | 11 | 13 | 10 | ||

| Training and other staff costs | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | |

| Premises costs | 1 | 2 | 7 | 5 | |

| Third party advice (legal/consulting) | 6 | 10 | 10 | 6 | 4 |

| Total – lower end | 24 | 60 | 72 | 92 | 83 |

| Upper end estimates | |||||

| Staff | 27 | 71 | 72 | 95 | 91 |

| Systems and IT | 1 | 15 | 20 | 16 | |

| Training and other staff costs | 2 | 2 | 5 | 5 | |

| Premises costs | 1 | 4 | 9 | 7 | |

| Third party advice (legal/consulting) | 9 | 14 | 14 | 8 | 6 |

| Total – upper end | 36 | 90 | 108 | 138 | 124 |

Staff costs

The headcount on which the establishment phase staff costs are based are set out in the FM and shown in Table 3.

| 2022-23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Establishment Phase | 200-300 | 440-660 | 440-660 | 60-90 |

This would suggest that there will be between 200 and 300 additional staff engaged in preparatory work for the NCS in the current financial year, at a cost of between £18 million and £27 million. The staff costs, combined with headcount assumptions imply an average annual cost per full-time equivalent (FTE) staff of between £80,000 and £110,000 through the establishment phase. Note that these are not salary costs, but will include wider costs such as employer National Insurance Contributions (NICs) and employer pension contributions. The FM notes that many staff in this phase will be in the data and digital space, including short-term contractors. Although employer NICs and pension costs will not apply to contractors, the remuneration costs for staff in these sectors might be higher due to the specialist skills involved.

The FM notes that the staff costs are based on estimates of the resource requirements at various stages of the programme but cautions that “this headcount profile is likely to change significantly as more detail is known.”

Staff costs are shown for the operational phase of the NCS at £59-88 million in 2025‑26 and £60-91 million in 2026-27. The FM indicates that this is based on the assumption that the full range of services (including children’s services and justice social work) will be transferred to the NCS from the outset. In practice, a narrower range of services might be transferred, or the transfer could be phased over a number of years. These staffing costs might therefore be expected to represent the upper end of potential costs in these years.

The FM states that the costs are based on an increase of 500-700 in the Scottish Government headcount, although the FM also states that these are not all additional posts, so it is unclear whether the costs relate specifically to additional posts (and if so, how many additional posts have been included in the cost estimates). No further details on the planned staffing profile are provided e.g. on staff grading structures. The estimated costs, combined with an increased headcount of 500-700 would imply average annual costs per staff member of between £85,000 and £180,000 depending on which end of the range is ultimately delivered. Again, these would include employer NICs and pension contributions. The Scottish Government has noted that, as with the establishment phase, there will continue to be data and digital contractors employed during the early years of the NCS, which affects the average.

For reference, according to a recent FOI response, the existing Scottish Government Directorate for Health and Social Care employs around 1,200 staff on a headcount basis. These proposals would therefore imply an increase of around 50% in the number of staff employed in the Scottish Government in the area of health and social care. Note that this refers only to staff employed centrally and does not include any staff employed locally in the proposed care boards.

It is not clear how these plans for increased staffing sit in the context of the Scottish Government’s stated intent to restrain the public sector pay bill, and to reduce the overall size of the public sector, as set out in the May 2022 Resource Spending Review.

Non-staff costs

Non-staff costs are also set out and include:

systems and IT

training and other staff costs

premises costs

third party advice (legal/consulting).

These non-staff costs are much lower than the staff costs, representing around a quarter of total costs through the establishment and operational phase. Table 4 shows the totals over the full five year period for each of these areas, with lower and upper end estimates provided. Staff costs are also shown for comparison. The FM notes that “further work is required to refine [the non-staff cost] estimates”.

| £ million | Total estimated costs for 5-year period2022-23 to 2026-27 |

|---|---|

| Staff | 237-356 |

| Systems and IT | 34-52 |

| Training and other staff costs | 10-14 |

| Premises costs | 15-21 |

| Third party advice (legal/consulting) | 36-51 |

In the past, major IT projects have been affected by cost over-runs and management issues, including the relatively recent Scottish Social Services Council's ICT project. Audit Scotland has reported on the Scottish Social Services Council's ICT project and wider issues in relation to public sector ICT projects and the Scottish Parliament’s Public Audit Committee receive regular updates on Major ICT Projects.

Care boards

Care boards are expected to replace the current Integration Joint Boards (IJBs). They will carry out the delivery functions of the NCS and be directly accountable to Scottish Ministers and directly funded by them. This is an important difference from the current IJB arrangements, where funding is allocated to IJBs via Health Boards and Local Authorities and accountability is to the Health Boards and Local Authorities. Care boards will also employ their own staff, unlike IJBs where staff remain employed by Health Boards or Local Authorities.

Highland does not currently have an IJB as it opted to use a different model of integration. As such, the new arrangements will involve the creation of a new body in this region.

When the care boards become operational in 2025-26, costs are expected to range from £132-326 million, rising to £142-376 million in 2026-27 (see Table 5). In the set up phase, there will be some costs to the Scottish Administration relating to recruitment and acquisition of premises.

The estimates assume that there will be some savings on current expenditure. For example, the FM costings are based on the assumption that IJBs will be abolished (although there is nothing specific in the legislation in relation to this). These savings are estimated at £25-40 million per year, although no detail is provided on the basis for these estimates.

| £ million | 2022-23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2026-27 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scottish Administration | - | 4-6 | 12-18 | - | - |

| Care boards | - | - | - | 132 - 326 | 142-376 |

Ministers will determine the number of care boards to be established. The FM states that the top end of the estimated costs reflects:

an assumption of 32 Care Boards – one in each local authority area

an immediate transfer of social workers and care staff to the NCS.

The lower end estimates assume a more gradual set up of care boards, possibly in a more limited number of areas. The FM is not specific about the exact assumptions around the timings and phasing, although does note that the lower end costs assume that no staff would transfer initially.

The Bill also allows for the creation of “Special Care Boards” to provide central functions, in a similar way to the existing Special Health Boards. However, any costs associated with any such Special Care Boards do not appear to be included in the FM estimates. The FM notes that the Special Health Boards (of which there are eight) have budgets ranging from £18-425 million, so the creation of Special Care Boards could add significantly to costs.

The FM notes uncertainties around costs in relation to pensions, VAT and treatment of assets:

In respect of pensions, an employer contribution rate of 20.9% has been assumed.

In relation to VAT, the FM notes that IJBs are able to reclaim VAT on services (unlike Health Boards). The current costings do not assume any VAT costs, but the FM acknowledges that such costs could be considerable if the set up arrangements require VAT to be paid.

No capital costs in relation to asset transfer or maintenance costs have been included in the FM costings. The FM notes that further investigation is required in respect of such costs.

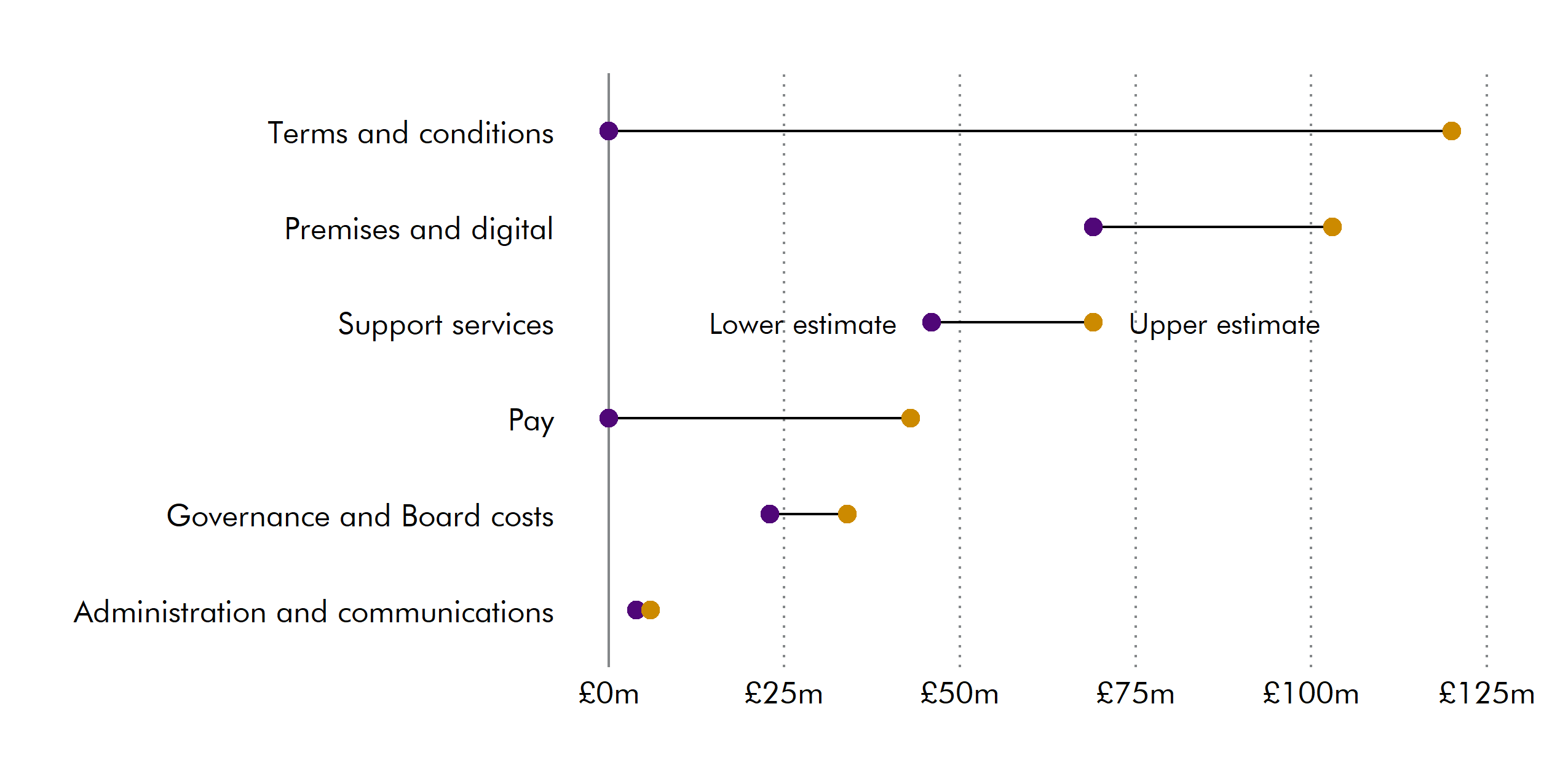

A breakdown of estimated additional care board costs in 2026-27 is shown in Figure 2.

The FM notes that there are potentially up to 75,000 social work and social care staff that could transfer from local authorities to the new bodies. Depending on the extent to which staff transfer to the new care boards, the costs associated with ‘Terms and Conditions’ for care board staff could represent up to £120 million in 2026-27, equivalent to around a third of the total costs for that year. This would involve aligning factors such as sick pay and holiday entitlement. In addition, additional pay costs could add a further £43 million to costs as rates of pay would need to be aligned. At present, rates of pay and terms and conditions for social work staff vary across local authorities.

The FM notes that there could be further costs and savings for local authorities and (to a lesser extent) health boards as a result of the transfer of functions to care boards. However, these are not estimated in the FM, which notes that this information will be included alongside the relevant secondary legislation in due course. Cost information associated with secondary legislation would not routinely be scrutinised by the Parliament’s Finance and Public Administration Committee.

The FM also notes the assumption that existing contracts for delivery of social care services with external partners will be transferred, so there would be no immediate cost implications for these partners. The FM does, however, note that changes to policies on (for example) ethical procurement or Fair Work could have implications for such partners in the future and that any costs associated with such policy changes will be subject to separate financial and regulatory impact assessment. Again, these financial and regulatory impact assessments would not receive the same level of scrutiny as an FM.

Health and social care information

The FM does not include any estimated costs associated with Part 2 of the Bill, which deals with information sharing and information standards. According to the FM, “this will enable the creation of the nationally-consistent, integrated and accessible electronic social care and health record”. The FM acknowledges that there will be costs involved in achieving this, but states that “at this early stage it is not possible to provide an exact position on the total cost of investment or how the costs will be phased”. Although these costs will be included in business cases in due course, these would not be subject to Parliamentary scrutiny and it would normally be expected that the FM should include at least some indication of likely costs, even where these are uncertain.

Rights to breaks from caring

The Bill includes proposals to establish a statutory right for unpaid carers to take short breaks. This will be via a personalised adult carer support plan (ACSP) or young carer statement (YCS). This will be in addition to existing funding available through a range of small grant schemes that provide easy access support for those in less intensive caring roles. Costs have been estimated based on:

numbers of carers and the intensity of caring (hours per week)

nature of replacement care (residential or home-based)

unit costs for replacement care, carer breaks and easy access support

cost and numbers of young carer support workers.

Assumptions have had to be made around:

numbers of carers that will exercise their right to breaks

average amount of replacement care for personalised support packages

balance between personalised support and easy access support

existing levels of local authority/IJB spending on breaks and replacement care

how demand and provision will evolve over time.

The assumptions are set out clearly in the FM, but the range of different assumptions on which the calculations are based means that the estimates will be sensitive to alternative assumptions. Reflecting this uncertainty, upper and lower end estimates are given.

Also, as the demand and scale of provision is expected to build over time, estimated costs are given for a longer time period than other aspects of the Bill. In the early years of implementation, costs are expected to be £8-13 million in 2025-26 and £16-27 million in 2026-27. However, by 2034-35, costs are expected to have increased ten-fold to between £82 million and £133 million. There are no estimated costs prior to 2025-26.

| £ million | 2025-26 | 2026-27 | 2027-28 | 2028-29 | 2029-30 | 2030-31 | 2031-32 | 2032-33 | 2033-34 | 2034-35 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower end estimate | 8 | 16 | 25 | 33 | 41 | 49 | 58 | 66 | 74 | 82 |

| Upper end estimate | 13 | 27 | 40 | 53 | 66 | 80 | 93 | 106 | 120 | 133 |

The FM also sets out the costs of easy access breaks, although these are not a direct consequence of this Bill.

The FM notes that information on breaks collected from the Carers Census that could be used to inform cost estimates is largely incomplete, but that measures are underway to improve the quality of information gathered.

The cost estimates presented in the FM do not incorporate any estimate of the potential savings that could result from enabling carers to take regular breaks from caring responsibilities. The FM does note, however, that these savings could be substantial as the Bill provisions around carers’ breaks are aimed at protecting the health and wellbeing of carers. For example, enabling breaks for carers could deliver savings on both social care and health expenditure through:

helping to ensure that existing caring relationships do not break down

reducing carer ill health

enabling carers to remain economically active.

Visits to/by care home residents ('Anne's Law')

“Anne’s Law”, which would be brought into effect by Section 39 of the Bill proposes statutory rights for those living in adult care homes to visit or be visited by relatives or others. The FM notes that changes to guidance were introduced in the light of the pandemic and new Health and Social Care Standards are now in place. As such, it is not possible to disentangle the costs of the new Standards from any related to the Bill. The FM does note that there may be costs for care homes and others in promoting the new arrangements, but that these are expected to be absorbed within updates to existing training and other materials.

Some modest costs are identified for the Care Inspectorate as a result of a larger number of individuals (care home residents, friends and family) exercising their right to complain in the light of the new arrangements. Any such increase is expected to be short-lived in nature while the changes are implemented, and so costs are not expected to persist beyond 2023-24.

As well as any increase in costs associated with additional complaints, there will also be modest costs for the Care Inspectorate in promoting the new guidance and Standards and in building capacity and capability within the sector. In 2022-23, additional costs are estimated at £186,000, falling to £90,000 in 2023-24.

The FM also highlights the health and wellbeing benefits of allowing such visits and notes that these benefits can also result in cost savings for the delivery of services. These costs are not quantified in the FM.

Changes to powers and functions of the Care Inspectorate

The Bill proposes some minor changes to the powers and functions of the Care Inspectorate, namely:

enabling the Care Inspectorate to cancel a service’s registration without first issuing an improvement notice under certain circumstances

allowing for Health Improvement Scotland (HIS) to support the Care Inspectorate in carrying out inspections (with HIS potentially charging for services).

Neither of these changes are expected to result in significant costs, so are not included within the FM estimates.

Local government

Local authorities have been responsible for the delivery of social services for decades, going back to the 1968 Social Work (Scotland) Act and the 1948 National Assistance Act. After education, social work/social care is the second largest area of local government expenditure, with councils spending over £3.5 billion of their net revenue expenditure on social services in 2020-211. This represented around a third of Scottish local government total net expenditure. As observed by a monitoring group of the European Charter of Local Self-Government earlier this year, social care in Scotland is “one of the largest municipal services”2.

Impact on local authorities - COSLA's views

The Bill sets out powers for the Scottish Ministers to transfer community health, social care, and social work functions to the NCS by secondary legislation1. Such transfers will have major budgetary, staffing, policy and governance implications for local authorities, and council submissions to the Parliament’s Health, Social Care and Sport Committee all raise concerns about the various ways they may be impacted. In its submission, umbrella body COSLA highlights a number of concerns, including the following general points:

The Bill will have an impact on many different areas of local government, with the potential loss of local authority functions and budget having wider consequences for the administration of local authorities.

There is a lack of clarity regarding the impact of the National Care Service proposals on local authority budgets.

The Bill’s Financial Memorandum (FM) both overstates the current funding made available to Local Government for social work/care and understates the actual costs of providing the services. Thus, the figures used in the FM are “wholly unreliable”.

No account has been taken of the impact of detaching social care and social work from other local services (for example housing, education, money advice, etc.).

The Bill will lead to the transfer of powers and accountability away from local communities to Ministers and unelected boards.

This is "over-centralisation and control" at the expense of services being designed and delivered locally, based on local knowledge and expertise.

Local democratic accountability as currently exists is critical to ensuring that differing local needs and circumstances are reflected in the care and support that is available to people when they need it.

COSLA’s submission states that the Government has not published any detailed assessment of how the Bill will impact local government. Indeed, there are 16 evidence and impact documents published on the Government's website, not including the Policy Memorandum, and none specifically covers how local government will be impacted. COSLA therefore argues:

It is important that in being asked to approve the Bill, that the Scottish Parliament has a full understanding of the impact of the Bill on any stakeholder whose functions are impacted either directly or indirectly. At a minimum, this should include the impact on Local Government, Health Boards and Health and Social Care Partnerships who are likely to be the most impacted by the Bill. There is no impact assessment on these crucial public bodies, their workforce nor indeed the continued operation of critical services whilst they are subjected to greater uncertainty.

With the Scottish Parliament’s Local Government, Housing and Planning Committee being a secondary committee during the Stage 1 bill process, the potential impact of the Bill on local government will likely be explored in detail with COSLA, individual local authorities and other stakeholders.

Potential impact on accountability and local democracy

In the Scottish Government’s Consultation Analysis document1, there is a short section on localism and local accountability, with analysts noting that “concerns were raised by many respondents about the loss of local accountability under a more centralised system”. However, in the Bill's Statement of Benefits2 the Government asserts that it knows “that people expect Scottish Ministers to be accountable for these [social work/care] services”. This assertion follows on from the Feeley Review which set out the following justification for a national care service:

The pandemic has demonstrated clearly that the Scottish public expect national accountability for adult social care support and look to Scottish Ministers to provide that accountability. Statutory responsibility for care homes sits with Local Authorities and individual providers. However, it was clear during the pandemic there was an expectation that Scottish Ministers should be held to account, which makes sense from a public health perspective.3

In the Bill's Policy Memorandum, the Government sets out its expectation that the new care boards will "represent the local population" and will include people with lived and living experience, and carers, "in addition to local elected members to preserve local democratic accountability". Nevertheless, the Bill is also clear that all care board members are to be appointed by Scottish Ministers.

Local councillors and Integration Joint Boards

Since 2016, Integration Joint Boards (IJBs) have been responsible for the planning and monitoring of adult social care, primary and community health care and unscheduled hospital care across most of Scotland. Boards may also be responsible for children's services and criminal justice services should local authorities choose to delegate these services.1.