Social Work in Scotland

This briefing describes how social work is organised, planned, and delivered in Scotland. It includes the key legislation and the policy context for social work. It presents the funding and workforce trends as well as covering the key challenges facing the sector and its workforce. It also looks ahead to upcoming changes to social work.

Summary

Social work is a varied profession which provides a wide range of services. These include care services for adults, services for children and families and criminal justice services, including the supervision and rehabilitation of offenders.

The statutory framework for social work services covers many different pieces of legislation. The Social Work (Scotland) Act 1968 is the key legislation and places the responsibility for these services with local authorities.

Current policy themes in social work are:

Personalisation and person-centred support, which puts the person first, as an expert in their own care.

Independent living, which aims to ensure people can live independently and in homely settings for as long as possible

Early intervention and prevention, which aims to take action to avoid problems escalating and requiring more intrusive or intensive services

Joined up working, which encourages smooth and collaborative working across relevant organisations

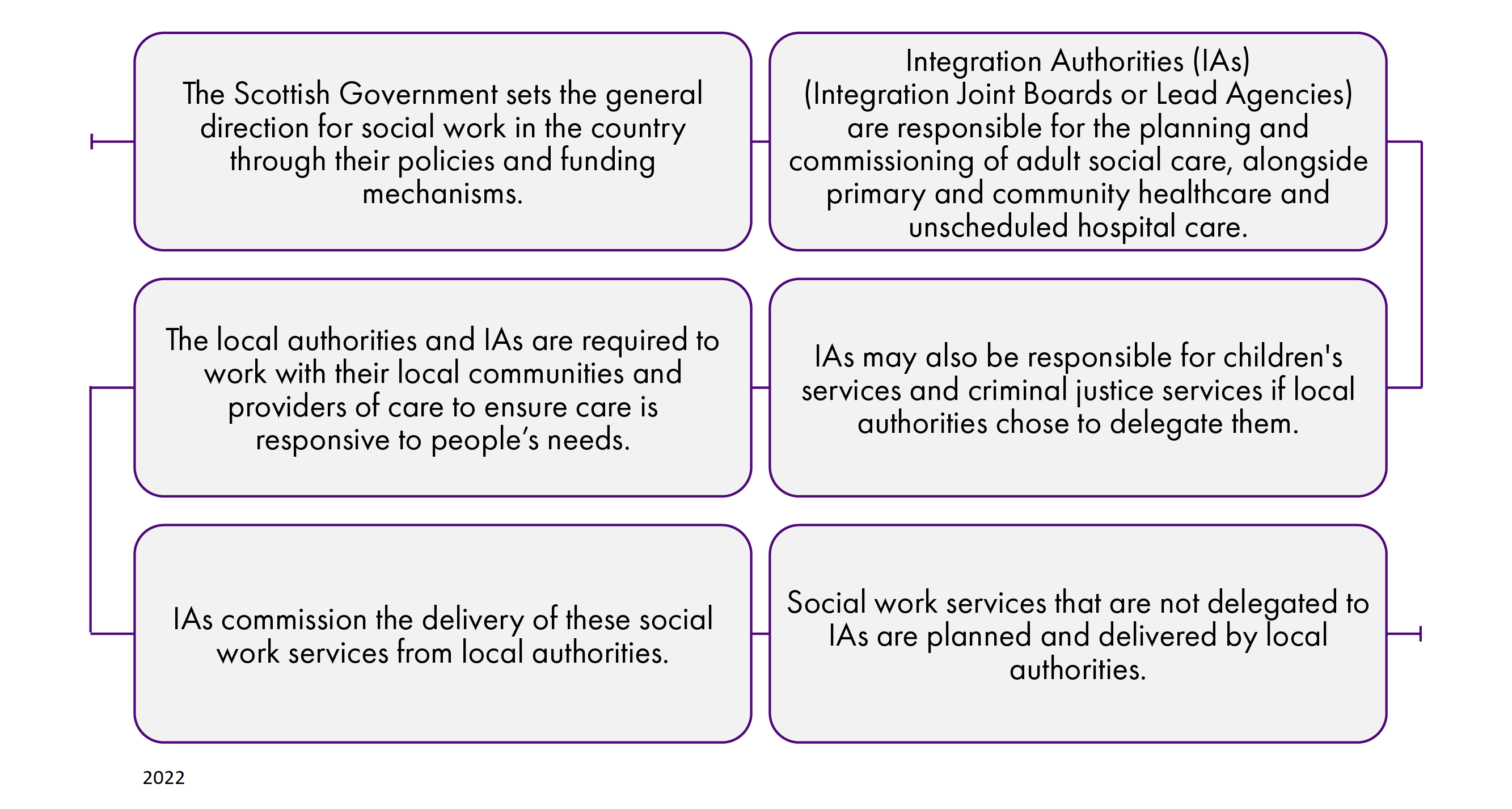

Since the integration of health and social care in 2016, Integration Authorities have been responsible for the planning and commissioning of adult social care. They may also be responsible for children's services and criminal justice services if local authorities have chosen to delegate these services.

Social work services are delivered by local authorities or are commissioned by local authorities from private or third sector organisations.

There are a number of issues and challenges within the sector which affect the social work workforce and services. Restricted budgets are one of the biggest challenges and can have wide ranging impacts on the outcomes for service users, workforce wellbeing and the recruitment and retention of staff1.

Other challenges have arisen from issues with the integration of services and slow progress to preventative and early intervention approaches2.

The Scottish Government's proposals for a National Care Service (NCS) are set to be a significant change to how social work is organised and delivered. The Scottish Government has consulted on the scope of the NCS.

There was general support for the NCS, and many agreed on opportunities for more consistent outcomes and coordinated working across organisations3. There was also support for a National Social Work Agency for national leadership of social work.

Some responses to the NCS consultation identified potential risks to social work3. Primarily these were concerns about the loss of understanding of local needs and potential lack of accountability within a centralised service. Concerns about losing local links to partners in the local authority like education or housing were also raised.

Introduction

Social work encompasses a diverse range of services provided to children and families, adults, and those in the criminal justice system. In Scotland, local authority social work departments deliver or commission these services with the aim of supporting some of the most vulnerable people in society and improving the quality of their lives1. The needs of people requiring social work services is hugely varied. Therefore, social work services encompass many levels of care, support, and protection for people at different periods in their lives or continuously throughout their lives.

The majority of social work and social care resources are directed towards adult services, mostly on care services for older people (65 years+). Alongside residential care and care at home, other adult social work services include mental health services, addiction support, help for adults with disabilities, dementia and Alzheimer's support, provision of mobility aids and re-ablement services, as well as supporting refugees and victims of trafficking 1.

Social work departments also provide services to children and young people to help support and protect vulnerable children and their families. These services include child protection, support for families, kinship care, adoption and fostering services, mental health services, support for young people in the justice system, children with disabilities and child refugees 1.

Criminal justice social work involves a range of services to the criminal justice system. Social work is involved in diversion from prosecution, implementation of social work orders and deferred sentences, and statutory or voluntary support and supervision to those serving prison sentences both before and after release 4.

What is Social Work?

"Social work is a practice-based profession and an academic discipline that promotes social change and development, social cohesion, and the empowerment and liberation of people. Principles of social justice, human rights, collective responsibility and respect for diversities are central to social work. Underpinned by theories of social work, social sciences, humanities and indigenous knowledges, social work engages people and structures to address life challenges and enhance wellbeing. The above definition may be amplified at national and/or regional levels"

The Global definition of social work, approved by the International Federation of Social Workers (IFSW) General Meeting and the International Association of Schools of Social Work (IASSW) General Assembly in July 2014

Key legislation

The cross-cutting nature of social work means that it is regulated by a complex statutory framework. The Social Work (Scotland) Act 1968 laid the groundwork for current social work services, placing the responsibility for these services with local authorities. The key legislation that has been aimed at improving social work services and the outcomes for people who use them is outlined in the annex. The range of legislation specifies how public services are organised, delivered and regulated, the rights of those who use social services and the responsibilities of social work staff and departments.

Current situation

Policy themes

The wide-ranging remit of social work means Scottish Government policy on social work is part of many different overarching policies. However, there are some recurrent themes around social work.

Personalisation and person-centred support

Personalisation is an aspect of the wider public service reform agenda and is also reflected in specific policy developments. The personalisation agenda focuses less on targets but instead offers flexibility to both service users and implementing agencies 1.

Focus on care being provided to the highest standards of quality and safety, whatever the setting, with the person at the centre of all decisions

Health and Social Care Delivery Plan Scottish Government. (2016). Health and Social Care Delivery Plan. Retrieved from http://www.gov.scot/Resource/0051/00511950.pdf [accessed 23 October 2018]

The GIRFEC approach is child-focused - it ensures the child or young person – and their family – is at the centre of decision-making and the support available to them

Getting it right for every child (GIRFEC) Scottish Government. (2021). Getting it right for every child. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/policies/girfec/

Aim to have effective, modern, person-centred and trauma-informed approaches to justice

The Vision for Justice in Scotland Scottish Government. (2022). The Vision for Justice in Scotland. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/strategy-plan/2022/02/vision-justice-scotland/documents/vision-justice-scotland-2022/vision-justice-scotland-2022/govscot%3Adocument/vision-justice-scotland-2022.pdf

Independent living

Policy around independent living is particularly centred around older people and people with disabilities. Across many areas, the Scottish Government states the aim to provide the right support to people who need it, so they can stay safely and independently in their own homes, for as long as possible. Independent living is about comfort and respect, as well as self-determination. Independent living is also part of the policy agenda to move resources to community settings from the acute sector, such as hospitals.

To ensure people get the right care, at the right time and in the right place, and are supported to live well and as independently as possible. An important aspect of this will be ensuring that people’s care needs are better anticipated, so that fewer people are inappropriately admitted to hospital or long-term care

Health and Social Care Delivery Plan Scottish Government. (2016). Health and Social Care Delivery Plan. Retrieved from http://www.gov.scot/Resource/0051/00511950.pdf [accessed 23 October 2018]

The Scottish Government’s approach to policy for disabled people ... is rooted firmly in the UNCRPD and in the aim of the independent living movement

A Fairer Scotland for Disabled People Scottish Government. (2016). A Fairer Scotland for Disabled People: delivery plan. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/fairer-scotland-disabled-people-delivery-plan-2021-united-nations-convention/documents/

Early intervention and prevention

Early intervention and prevention have been a major driver in policies in education, health, justice, and early years for some time. Prevention and early intervention usually refer to actions taken to avoid more intrusive or intensive services at a later time. For example, mentoring schemes for young people who are at risk of becoming involved in crime, to prevent them being taken into custody later on.

These principles are present throughout policy on social work, particularly since the Christie Commission on the future delivery of public services in 2011, which recommended prioritising prevention and early intervention.

The GIRFEC approach is based on tackling needs early - it aims to ensure needs are identified as early as possible to avoid bigger concerns or problems developing

Getting it right for every child (GIRFEC) Scottish Government. (2021). Getting it right for every child. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/policies/girfec/

Prevention and early intervention are key to minimising the prevalence and incidence of poor mental health and the severity and life time impact of mental disorders and mental illnesses. Prevention and early interventions must be a focus of activity and funding

Mental Health Strategy 2017-2027 Scottish Government. (2017, March). Mental Health Strategy 2017-2027. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/publication/2017/03/mental-health-strategy-2017-2027/documents/00516047-pdf/00516047-pdf/govscot%3Adocument [accessed 28 January 2018]

We must reset the social contract with our public services – ensuring we are all supported at the earliest opportunity to improve our life chances and reduce our risk of offending

The Vision for Justice in Scotland Scottish Government. (2022). The Vision for Justice in Scotland. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/strategy-plan/2022/02/vision-justice-scotland/documents/vision-justice-scotland-2022/vision-justice-scotland-2022/govscot%3Adocument/vision-justice-scotland-2022.pdf

Joined-up working

The integration of health and social care is a key aspect of social care planning and delivery. The aims of a joined-up approach to delivering social work services extends beyond health to include education, police, the justice system, housing and more.

Integration aims to improve care and support for people who use services, their carers and their families. It does this by putting a greater emphasis on joining up services and focussing on anticipatory and preventative care

Health and Social Care Integration Scottish Government. (2021). Health and social care integration. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/policies/social-care/health-and-social-care-integration/

GIRFEC requires joined-up working - it is about children, young people, parents, and the services they need working together in a coordinated way to meet the specific needs and improve their wellbeing

Getting it right for every child (GIRFEC) Scottish Government. (2021). Getting it right for every child. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/policies/girfec/

Justice services work together to ensure joined-up services and ensure person-centred outcomes, building partnerships and ensuring the system wide impact of our actions are factored into our decision making. Our workforces are supported to see their part in the bigger picture and be supported in their wellbeing

The Vision for Justice in Scotland Scottish Government. (2022). The Vision for Justice in Scotland. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/strategy-plan/2022/02/vision-justice-scotland/documents/vision-justice-scotland-2022/vision-justice-scotland-2022/govscot%3Adocument/vision-justice-scotland-2022.pdf

Joined up services was a key approach recommended in Changing Lives: the Report of the 21st Century Social Work Review in 2006. One of the key conclusions of the report was that:

Social work services don't have all the answers. They need to work closely with other universal providers in all sectors to find new ways to design and deliver services across the public sector

Scottish Government. (2006). Changing Lives: Report of the 21st Century Social Work Review. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/changing-lives-report-21st-century-social-work-review/

Policy context

Getting It Right For Every Child (GIRFEC)

Getting it right for every child (GIRFEC) is the Scottish Government approach to supporting children and families. It is the framework by which services like social work, health and education should work with young people and their families to provide the support they may need 1. It was developed in "pathfinder areas" from 2006 and was implemented as a national approach in Scotland in 2011. GIRFEC is based on the principles of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) 2. The Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014 legislated for some of the key aspects of GIRFEC. The framework outlines that practitioners should:

Put the child or young person, and their family, at the centre of decision making and for the support available to them.

Offer the right support to promote eight factors contributing to the child's wellbeing (safe, healthy, achieving, nurtured, active, respected, responsible, included - SHANARRI).

Take preventative approaches to ensure their needs are met early to avoid problems escalating.

Work together with all other services they may need in a coordinated way to meet their specific needs and focus on their wellbeing.

Through shared resources, support and practical guidance, ‘universal’ services (e.g. midwives, health visitors, pre-school, and school) as well as ‘targeted’ services (e.g. social work) are all recommended to use this overarching approach.

A key element of the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014 is that every child has a named person, a clear point of contact for the child or their family when they need information, advice or support. Alongside this, a personalised child's plan would be drawn up where the child needs extra support to be coordinated and delivered. There were concerns around privacy in relation to the named person and child's plan components of the Act leading to a supreme court challenge of the Act in 2017. The ruling found the aims of the 2014 Act were legitimate, but that the information sharing provisions of the Act were not compatible with privacy rights and not within the legislative competences of the Scottish Parliament 3.

The named person and child's plan requirements were not implemented. In 2019, the Deputy First Minister announced that the Scottish Government intended to repeal these aspects of the Act. He confirmed a commitment to these aspects of the Act on a non-statutory basis, and many local partners already operate these aspects voluntarily under current legal powers4. The Scottish Government are still considering how to proceed to repeal these aspects from the Act5.

Sharing similar principles, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (Incorporation) (Scotland) Bill was passed by the Scottish Parliament in 2021. This Bill aimed to incorporate children’s rights outlined by the UNCRC into law. The Bill would require Scotland’s public authorities ensure the protection of children’s rights in all their decision-making and service delivery. The Bill has not received Royal Assent due to aspects of the Bill being outwith legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament. Much of the work implementing the UNCRC is already ongoing through GIRFEC. The Scottish Government hopes to take this legislation forward after considering the implications of the ruling and addressing those areas that are outwith legislative competence6.

The Promise

Where a local authority takes on legal responsibilities for a child's care, they become 'looked after'. The Independent Care Review notes children and young people prefer the term 'care experienced' to describe their circumstances, the term 'looked after' has a particular meaning in law. Therefore, this briefing will use the term 'care experienced' where possible, but 'looked after' will be used in relation to the relevant legislation and policy. This may be for a range of reasons, for example because the child has experienced abuse or neglect, has complex disabilities requiring specialised care, has become involved in the justice system, or is unaccompanied and seeking asylum. The complex landscape of legislation, policy, and practice that these children find themselves in is known as the 'care system'. In 2017, the Scottish Government commissioned an independent review of the Scottish care system. People with experience of the care system represented half of the review group’s co-chairs and working group members. During the lifetime of the review, the views of over 5,500 care experienced children and adults, as well as parents, carers and the care workforce, were listened to and informed the final findings. The report of the Independent Care Review, 'The Promise' was published in 2020 1.

The Promise reflects the work needed to change the care system to improve the wellbeing and outcomes for children and young people. The Independent Care Review concluded in 2020 and the Scottish Government accepted all of the recommendations, with all political parties pledging to 'Keep the Promise'. The promise sets out the vision for children to grow up loved, safe and respected, built on five foundations:

Voice: That children's voices are heard and they are involved in decision making.

Family: Children must stay with their families if it is safe to do so.

Care: if family care is not possible, siblings must stay together where it is safe, and should stay in a loving home as long as needed.

People: Children must develop relationships with people in the workforce and community.

Scaffolding: There must be a system to support children, families and the workforce.2

In 2021, ‘The Promise Scotland’ was established with a dual responsibility of oversight of progress towards the commitment to "Keep The Promise" and to provide support for its delivery by leading, collaborating, and driving change:

It works with all kinds of organisations to support shifts in policy, practice and culture so Scotland can #KeepThePromise it made to care experienced infants, children, young people, adults and their families - that every child grows up loved, safe and respected, able to realise their full potential.

thepromise.scot

In 2022, the Scottish Government published its Keeping the Promise implementation plan which sets out their actions and commitments for the next 10 years to ensure The Promise is kept.

Disabled people

The Scottish Government's policies for disabled people are based on the "social model of disability", where people are disabled by barriers placed by society not being able to provide for their needs and rights, rather than a medical model which places blame on their impairment 1. Key to the Scottish Government's policy is delivering on the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD). Its strategy is laid out in a 'A Fairer Scotland for Disabled People', a plan built around five ambitions:

Independent living and met needs.

Fair work.

Accessible places.

Protected rights.

Active participation.

Mental health

The Mental Health Strategy 2017-2027 outlines the Scottish Government's aim of achieving parity between mental and physical health. The strategy recognises poor mental health is the responsibility of more than the NHS, but that the wider public services must work collectively to improve mental health. The strategy aims to work alongside other Scottish Government policies to:

tackle poverty

address mental health needs in the justice system

develop a robust social security system for those who need it

address unemployment

work with teachers and school staff to help young people with mental health needs 1.

The strategy focuses on early intervention and preventative approaches to poor physical health of people who suffer from mental ill health, including from addiction. The strategy committed the Scottish Government to undertaking a review of the strategy in 2022, its halfway point, and work on refreshing the strategy is underway.

The Scottish Government's Mental Health Transition And Recovery plan outlines the response to worsening mental health as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. The plan included expanding existing mental health services like mental health support through NHS 24 and digital solutions with online delivery of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT). It also has the aim of supporting local authorities to set up more community mental health and wellbeing services.

Criminal justice and reducing reoffending

The Scottish Government's 2022 Visions for Justice in Scotland outlines its aims for criminal justice. There is a continued focus on shifting towards more community-based alternatives to prison. For example, through unpaid work as part of Community Payback Orders (CPOs) or Drug Treatment and Testing Orders (DTTOs).

The Community Justice (Scotland) Act 2016 was implemented in 2016 and the Scottish Government set out its plans for strengthening community justice services, which included community sentencing and criminal justice social work. Community Justice Scotland was established in 2017, with the aim of improving the joined up working of services (public sector, third sector and other partners) to reduce reoffending.

Alcohol and drugs

A key aspect of the Scottish Government's approach to tackling alcohol and drug misuse is a joined-up approach and embedding work on drug deaths and harm across other aspects of policy including mental health, homelessness, and justice to address underlying issues. Part of this joint up approach is the use of Alcohol and Drug Partnerships (ADPs) which brings together local NHS boards, local authorities, police and voluntary sector organisations to collaboratively address drug and alcohol issues. These ADPs are responsible for developing strategies that are based on local needs to tackle alcohol and drug misuse. They are also responsible for commissioning services, which may be from local authorities social work departments, to promote recovery and take preventative approaches to reduce prevalence of problem substance use 1. Social work departments may assess the needs of someone who is referred to them, and then refer them to relevant drug or alcohol services that have been commissioned by ADPs that may meet those needs2.

In 2021, the Scottish Government announced that a new national mission to reduce drug related deaths and harms would be established and supported by additional funding for community-based interventions and greater capacity in residential rehabilitation. The national mission aims to provide fast access to the right treatment and support and improved frontline drugs services.

Integration of health and social care services

A number of policies have been introduced in Scotland and across the UK in recent decades which have aimed to increase integration of health and social care services. The desire for more integrated services has been driven by ongoing and predicted changes in health and social care pressures due to rising costs and demand. Scotland has an ageing population1 and a declining healthy life expectancy (the number of years one can expect to live in good health)2. These demographic changes mean the health and care requirements of Scottish people are changing, with more people with complex care needs.

The Public Bodies (Joint Working) (Scotland) Act 2014 was commenced with the aim of adapting public services to the changing population, better integrating the health and social care systems3.

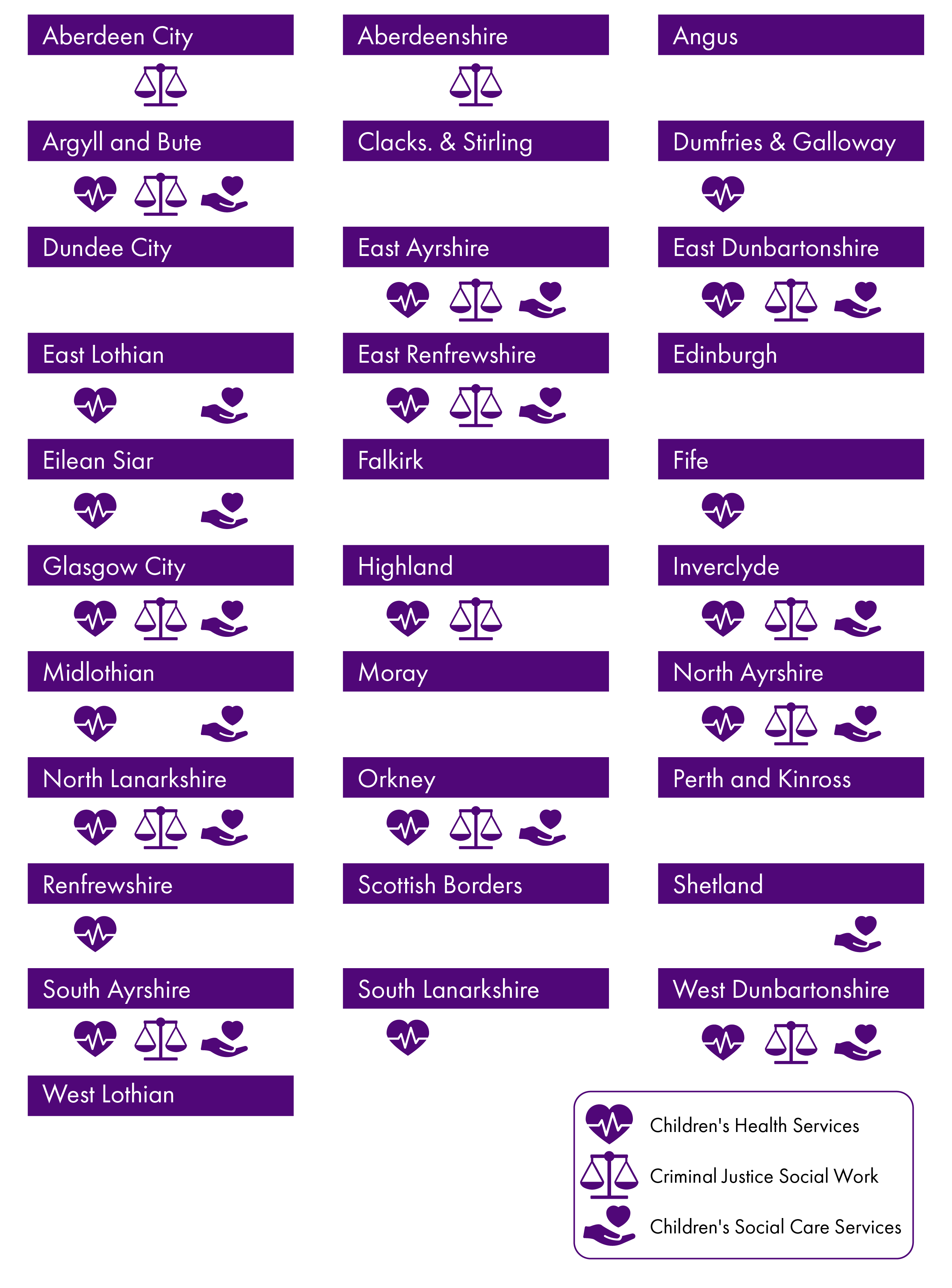

Integration was a significant change in the delivery of health and social care. The Act created 31 new integration authorities (IAs), partnerships between the 14 territorial health boards and 32 local authorities (Clackmannanshire and Stirling councils have joined to create a single integration authority). These IAs are responsible for planning adult social care, primary and community health care, and unscheduled hospital care, delivered by Health and Social Care Partnerships. Beyond these minimum delegated services, the Act also allows children’s services and criminal justice services to be delegated to IAs 4. All IAs have some aspects of children's health delegated, but there are 19 which have fully delegated children's health services. Criminal justice services has been delegated in 17 IAs, and 12 have delegated responsibility for children's social care services 5.

All but one IA follows the Integrated Joint Board (IJB) model, where a new body was established to take on these responsibilities for governance, planning and resourcing of the delegated services. The Highland integration authority instead uses a Lead Agency model, where the NHS board or local authority take the lead in planning and delivering delegated services4.

Alongside the planning and delivery of delegated services, the integration authorities must identify methods of improving the quality and consistency of their services. In line with the Scottish Government's agenda, the IAs should aim to shift services to preventative and community based care8.

Each IA develops a strategic commissioning plan with involvement from stakeholders, outlining how they will plan and deliver services over the medium term. The plans result in binding directions given to the health board or local authority with actions they are responsible for carrying out to deliver the plans9.

Planning and delivery of social work services

Planning and organisation of social work services is the responsibility of IAs, or local authorities where services are not delegated. IAs or local authorities will commission services, or the local authorities will deliver the social work services themselves according to the plans set out.

Service planning example: Moray Physical and Sensory Disability Strategy 2017-2027

The Moray Integration Joint Board is responsible for adult social care. Their strategic plan sets out the overarching plan for health and social care in the area and the physical and sensory disability strategic plan sets out in more detail the local priorities for people with physical and sensory disabilities.

Needs assessments of disabled people in Moray informed the plan and available services were reviewed to identify gaps in service. The plan is based around four pillars: health and wellbeing, independent living, choice and control, and active and equal citizenship. It outlines what services should focus on, based on identified priorities. For example, under the health and wellbeing pillar, they identify services should focus on:

Helping people make more informed choices around smoking, healthy eating, and alcohol.

Increasing opportunities for people to increase their levels of physical activity.

Increasing access to support for people to improve and maintain their mental wellbeing.

Enhancing health checks and assessments to support early intervention and prevention.

These focus areas inform what services for disabled people are commissioned or provided by Moray council.

Social care for adults and children with care needs is primarily delivered through self-directed support, where eligible individuals are given the opportunity to choose how they receive care. Care may be delivered by local authorities or commissioned from private or third sector organisations. Other aspects of social work involve statutory interventions in serious and complex issues 1. This includes care and protection where an adult or child is at risk, compulsory interventions on mental health grounds or for adults with incapacity, as well as social work within the criminal justice system.

It is a requirement of the Social Work (Scotland) Act 1968 that every local authority must appoint a Chief Social Work Officer (CSWO). The CSWO is the leadership role of local authority social work and oversees all social work services within the local authority. The CSWO also has a role in IJBs as a non-voting member of the board, representing social work when IJBs make strategic and commissioning plans2.

The work of social work departments is highly varied and delivery of services reflects that. A lot of the work is done through discussions with people who are referred to them, relationship building, listening, advising, and referring to partner agencies. Work may be done as part of a short term programme, for example some alcohol and drug services commissioned by ADPs3, or it may be a routine and embedded practice like providing care packages based on assessments4. The predominant methods of service delivery are outlined below.

Self-directed support

Social work services include the assessment and arrangement of care and support for people who need it. The way this care is organised is primarily through self-directed support (SDS), as stipulated by the Social Care (Self-directed Support) (Scotland) Act 2013. Anyone can ask for, and has a legal right to, an assessment from their local authority. The local authority's social work department must then carry out an assessment of needs in collaboration with the supported person and other relevant individuals. Social work staff assess someone's level of need and desired outcomes, which will include any medical conditions or disabilities, and what support is already in place. Assessment follows a framework of four categories of risk (low, moderate, substantial and critical) 1. After assessment, the social worker will check if they meet the eligibility criteria for care support to meet their needs. If they are identified as having needs that meet eligibility criteria and require a budget, then they are given four options:

A direct payment, so the person can purchase their own support.

The supported person chooses their support, but someone else arranges the support and manages the budget.

The local authority manages support and budget on behalf of the supported person.

A mix of the above.

Alongside these options, social work staff will provide information and advice about the options available. Social work staff may also provide advice and alternatives to those who do not meet the eligibility criteria.

Each local authority sets their own eligibility criteria that they follow, based on the resources they have available. The criteria will follow the national framework for categorising risk, but because criteria are set locally, the availability and provision of care differs from one local authority to the next1. Most local authorities, however, only have resources to provide services to people in substantial or critical risk categories after assessment3.

Social work departments will arrange the care or support required that has been identified in the assessment. The package of care and support may be reviewed if the supported person requests it or if there is a significant change to their needs to confirm the care provision is still appropriate4.

The provision of care is delivered within a mixed economy, meaning social work departments are both care providers and facilitators. Local authorities may deliver services themselves or commission services from the private and voluntary sector. Commissioning from the private sector is mostly used for residential care for older people (76%) and nursing care (97%). The voluntary sector is mostly commissioned for care home services for people with learning disabilities (62%), physical and sensory impairments (76%), and mental health problems (64%)5.

Statutory care and protection

Social work staff must make the decisions for when and how to intervene in complex cases of care and protection. Where adults or children are in need of protection, at risk of significant harm, at risk of causing significant harm to themselves or others, or unable to give informed consent for their care, social work staff will undertake enquiries or investigations and make recommendations for whether a person requires compulsory protection 1.

Children's social work services

Further details on the children's care system can be found in the subject profile briefing on Scotland's care system for children and young people, but is outlined below.

The Scottish Government's Children's Social Work Statistics are published annually and report the number of children in Scotland who are looked after or on the child protection register. The latest data covers the period 1 August 2020 to 31 July 2021. During this time there were 13,255 children in Scotland who were looked after and 2,104 children on the Child Protection Register. Of these children, 413 were both looked after and on the Child Protection Register. In total, this is 1.5% of the population of under 18 year olds in Scotland1.

Looked after children

Children who have experienced neglect or abuse, need specialised care because of complex disabilities, or have become involved in the youth justice system may become involved with the care system. This is when the local authority takes on some legal responsibility for the child's care and they become 'looked after'. The Independent Care Review notes children and young people prefer the term 'care experienced' to describe their circumstances, the term 'looked after' has a particular meaning in law. Therefore, this briefing will use the term 'care experienced' where possible, but 'looked after' will be used in relation to the relevant legislation and policy

Children can become involved in the care system through referrals to the Children’s Reporter, through the justice system or sometimes on a voluntary basis between the local authority and family. Referrals to the Children’s Reporter are mainly from agencies like the police, education, or a social worker who has concerns for the child. Referrals can, however, be made by anyone, including their parents and family members, or the public 1.

The Scottish Children's Reporter Administration organises the work of children's reporters and children's hearings. Children's reporters determine if a child or young person needs a hearing and will facilitate the hearing. The children's hearing is a multi-agency legal meeting where decisions are made in the best interests of the child or young person and can include compulsory measures of care, for example, setting out where a child must live.

Social work staff have a role in preparing reports and making recommendations to a children's hearing or court on matters such as whether a child should be accommodated away from home, or about the permanence, termination, or alteration of supervision requirements. They will also make recommendations and organise adoption and foster care if required 2.

Children who are formally 'looked after' may live in a number of different arrangements including:

at home under a Compulsory Supervision Order (where the child has regular contact with social services)

in kinship care with friends or family members

in foster care or with prospective adopters

in a residential school

in a secure care setting.

A multi-agency team around the child, usually including social work, education, and health services (and other specialist services where required) work with the child and their family to develop a care plan for them. The plans should detail the child’s care, education, and health needs, and outline the roles of each partner in the plan in delivering the child's needs. Local authorities also provide aftercare services for young people leaving care, giving advice, guidance, and assistance for care leavers3.

Children and young people who, for a variety of reasons, might pose a risk to themselves or others in the community may be placed in secure care. This is a locked environment where the child’s freedom is restricted while they are provided with intensive support. In 2020-21 there were 178 children admitted to secure care1. Chief Social Work Officers may take the decision to recommend secure placement for a child. This action is only taken if authorised by the Children’s Hearing System or a Court. It may also be taken as a short-term emergency plan before attending a hearing or court5.

Child protection

Social work, health services and the police have a responsibility to investigate child protection concerns that are referred to them 1. A child may be placed on the child protection register if they are believed to be at risk of significant harm from neglect or abuse. The local authority social work department are usually the key agency in arranging a meeting (Child Protection Planning Meeting) of the family and multi-agency professionals. The planning meeting reviews a child’s referral to child protection and determines if they should be placed on the register. For each child on the register, together with the multi-agency professionals and with involvement of the family, the local authority social work department have a role in preparing a child protection plan, which outlines the actions needed to safeguard the child and promote their welfare. This may include care and support requirements or placements that the local authority must provide. The Child Protection Planning Meeting review the case regularly to determine if they should remain on the register or be de-registered2.

Mental health and adults with incapacity

Social work staff have a duty to enquire into cases where adults with a mental disorder might be at risk from others or where they are putting themselves or their property at risk1. Mental health officers (MHOs) are social workers with specific training and have specific statutory roles in mental health services under the Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003 and Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000. The 2003 Act specifies when someone can be given treatment, hospitalisation, or detention against their will. MHOs have a number of duties under the Act. Detention is usually recommended to a court by a doctor or a psychiatrist, preferably with involvement from an MHO. For some detentions, like short-term detentions, the involvement of an MHO is required. If someone is required to receive treatment or care under the Act, an MHO will be appointed to interview them and advise them of their rights. MHOs also have a responsibility for providing consent for assessments or treatments in hospital. They will apply for compulsory treatment orders if they deem them to be appropriate, and liaise with Mental Welfare Commission and named persons about someone's treatment or detention2.

Where an adult is not able to make care decisions for themselves, or lacks the ability to communicate, social work staff will provide assessment and support. At an early stage of assessment and care management, social work staff will check if the person has a proxy, someone who has power under the 2000 Act to make decisions on behalf of an adult whose capacity is impaired. If nobody is available, social work staff will apply for a guardianship or intervention order if it is deemed necessary in order to protect the welfare of an adult with incapacity3.

Criminal justice social work

Social work is involved in the criminal justice system at three stages1:

Diversion from prosecution.

Implementation of social work orders and deferred sentences.

Statutory or voluntary support and supervision to those serving prison sentences both before and after release.

Criminal justice social work (CJSW) services provided by local authorities include:

Assessments and reports to inform sentencing decisions and parole boards.

Advice, support, or supervision to those attending court, and those on bail as an alternative to custodial remand.

Supervision of social work orders and unpaid work.

Services within prisons to those serving custodial sentences.

Throughcare and prison aftercare services to ensure public safety.

Support for victims of crime and their families.

In less serious cases, it may be appropriate to take action but avoid prosecution. The Procurator Fiscal may issue a direct measure, including warnings, fines, and fiscal work orders. A fiscal work order is an issue of 10-50 hours of unpaid work as an alternative to prosecution, supervised by CJSW staff. If the Procurator Fiscal issues a diversion from prosecution, CJSW will assess the suitability of the alleged offender. Diversion from prosecution is used when an offender has an identifiable need that has contributed to the offence. Diversion from prosecution should provide an intervention to address the need in order to reduce the risk of further offending2.

CJSW may provide court services to those attending court as well as assisting court proceedings with assessments or recommendations. If an individual is prosecuted and given a community sentence, CJSW will be involved in a number of ways depending on the sentence.

Most community sentencing is through the use of community payback orders (CPO), which allow courts to issue community service or probationary requirements to offenders, supervised by CJSW staff. There were 16,800 CPOs in 2019-20, before a fall to 8,200 in 2020-21 due to the pandemic decreasing court business. CPOs should have either, or both, an offender supervision requirement or an unpaid work requirement. They may also have other requirements like compensation, mental health treatment, or drug or alcohol treatment1.

For offenders with a more serious substance misuse problem related to their offending, the judge might issue a Drug Treatment and Testing Order (DTTO) involving social work supervision. The order involves treatment of drug addiction, regular testing and reviews with the sentencers. Social workers do not provide treatment, but act as the link between the offender and the court and sentencer through progress reports, attendance at hearings and carries out any required actions in the case of a breach 4. The courts issued 510 DTTOs in 2019-20 and 230 in 2020-211.

If an individual is given a structured deferred sentence, they are given a short period of supervision from social work staff after they have been convicted, but before final sentencing. These sentences aim to help the offender address, with a multi-agency approach, any underlying issues that have resulted in offending behaviour6.

Throughcare provides social work support to people serving custodial sentences from the point they are sentenced, through their period of imprisonment and after their release. Throughcare is designed for both public protection, as well as to facilitate reintegration and rehabilitation after release into the community. There are statutory throughcare supervision requirements for those serving prison sentences over four years, short-term sex offenders, and others given supervised release orders. An offender can also request voluntary throughcare if they are not given statutory requirements. CJSW throughcare responsibilities include clear communication to offenders at various points from sentencing to release to identify potential problems and communicate support available in prison units and after release. Their responsibilities also include reports to parole boards to inform release decisions including home background reports7.

How social work is funded

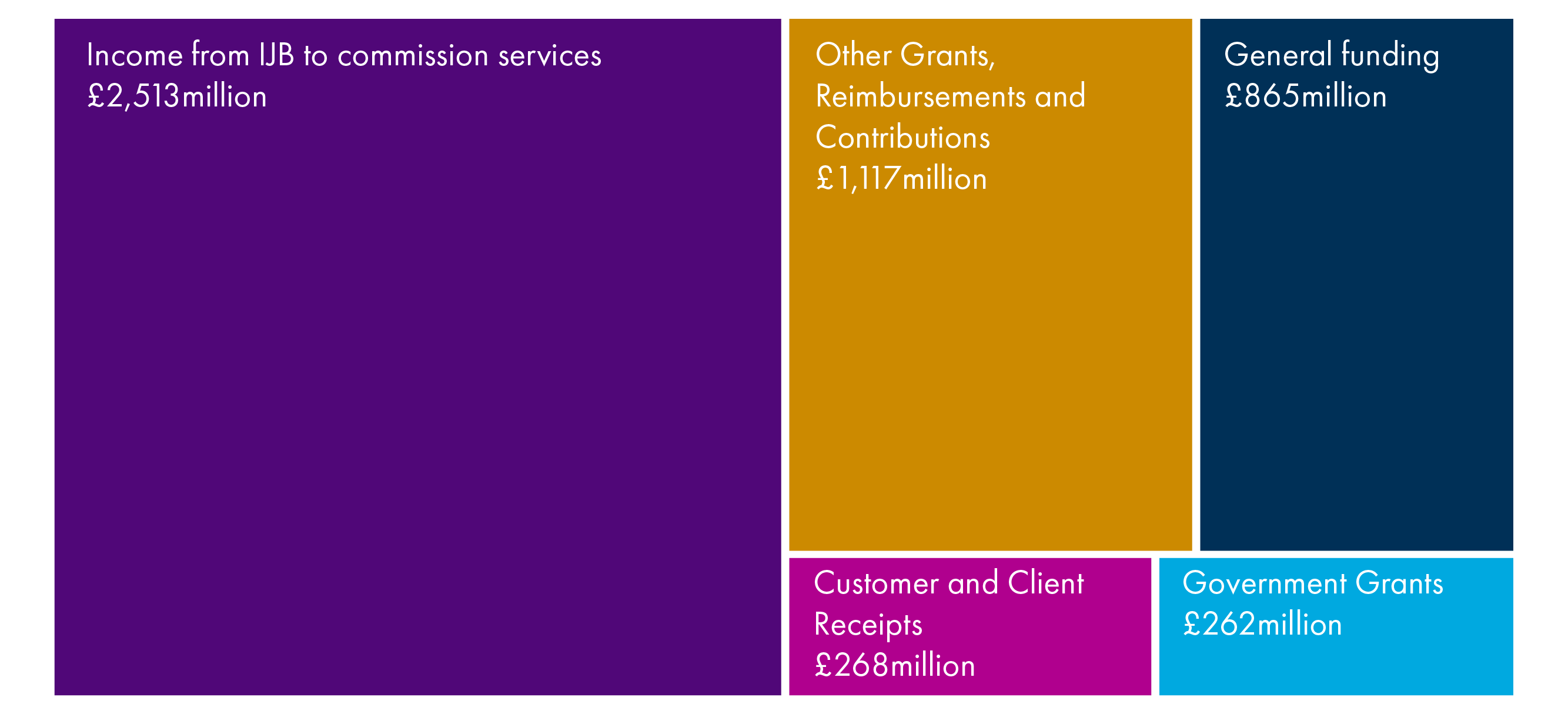

Social work services are primarily funded by integration authorities (IJBs or the Lead Agency), service specific grants, and local authority general funding.

Each IA receives funds directly from the health board and local authority as per their agreed budgets, and there are no separate funding streams directly from the Scottish Government1. The IJBs have a duty to develop a strategic plan for their budgets. Enacting these plans, they fund and commission social work services from local authorities2.

Local authorities also receive grant funding for specific services from Scottish Government, contributions from health boards (outwith IJB funding) and other local authorities, as well as income from service users. Local authorities also fund social work services from their general funding (General Revenue Grant and local taxation) or from their reserves3.

Gross expenditure by local authorities on social work services in 2020-21 was £5,041 million 3. £2,513 million of this social work expenditure, around half, was funded by income from IJBs to commission specific services. A further £1,378 million was funded by service specific grants, reimbursements and contributions, and £268 million from income from service users. The remaining £865 million is paid for by general funding, which is general income to local authorities and not funding for specific services.

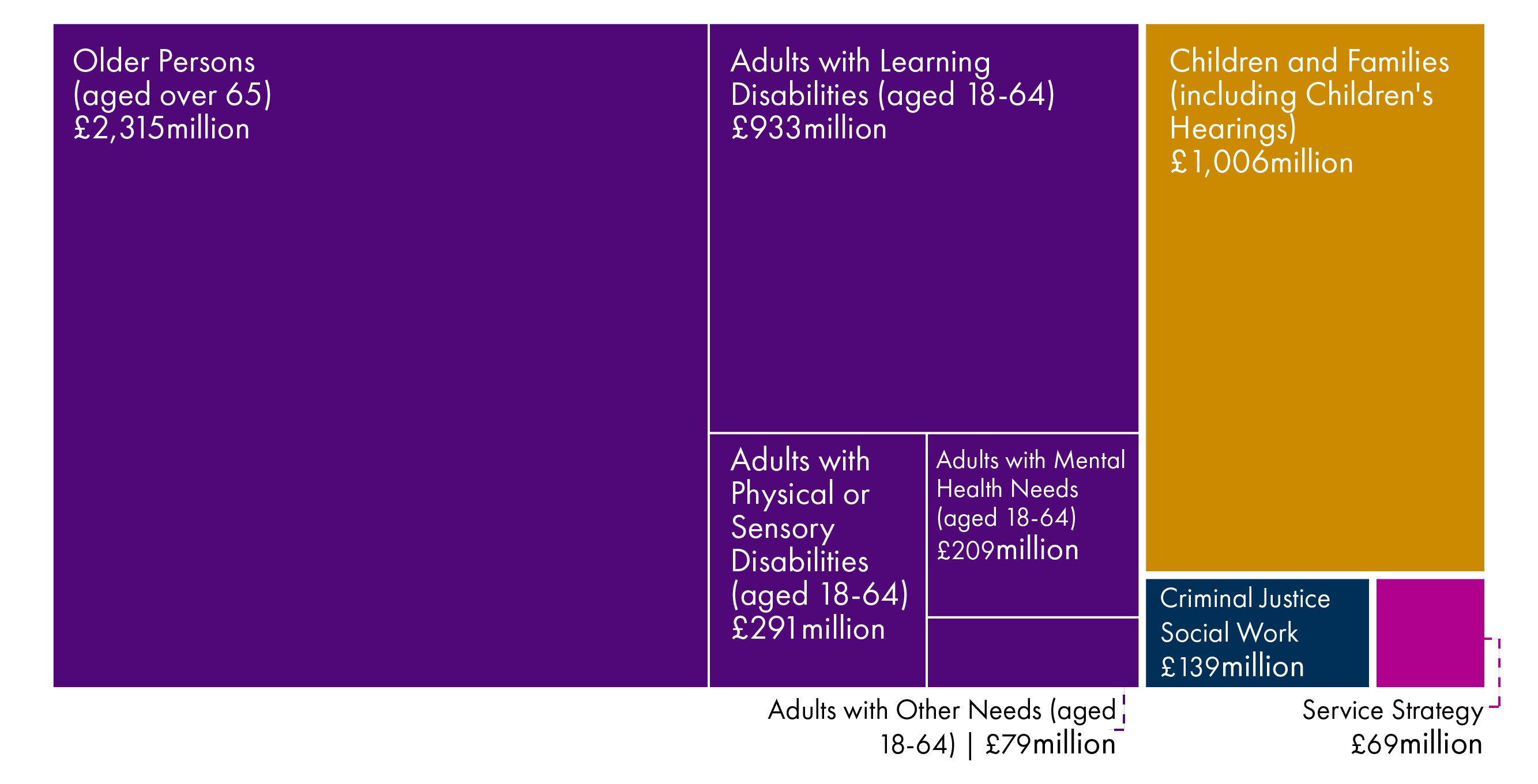

Expenditure is greatest on adult social care services to older people (65 years +), which received £2,314 million, or 46% of all social work expenditure in 2020-21. Other adult services received 30% of total social work expenditure in 2020-21. These services to adults aged 18-64, include services to people with physical, sensory, and learning disabilities, mental health needs, addictions, asylum seekers and refugees. A further 20% went to children and family services.

Gross expenditure on social work has been increasing in recent years and was 7.3% greater in 2020-21 than in 2019-20. This increase is seen in spending on all subservices of social work, except in children's hearings. The reduced expenditure on children's hearing reflects the reduced number of hearings held in this year due to the pandemic7. Both the costs of providing social work services and the income to local authorities on a funding basis for these services have increased. When contributions to IJBs are included in expenditure, the absolute value of the increase in expenditure is larger than the increase in income on a funding basis, leading to an overall increase in expenditure from general funding.

Workforce

The Scottish Social Services Council (SSSC) is the regulator of the social work, social care and early years workforce in Scotland. It also provides official statistics on the workforce.

The term “social service workforce” is usually used to refer to the whole workforce of people engaged in the delivery of social services, including children's daycare, local authority social work services, adoption and fostering, care homes, and housing support, whoever their employer may be. The social service workforce in Scotland is the largest it has ever been. The size of the social services workforce in 2020 was 209,690, roughly 8% of the national workforce. The social service workforce predominantly work in care services. Across the whole sector, 39% were employed in the private sector, 34% in public and 27% in the voluntary sector. It is a predominantly female workforce, with women making up 83% of the social services workforce, and 80% of those employed in the local authority social work service workforce1.

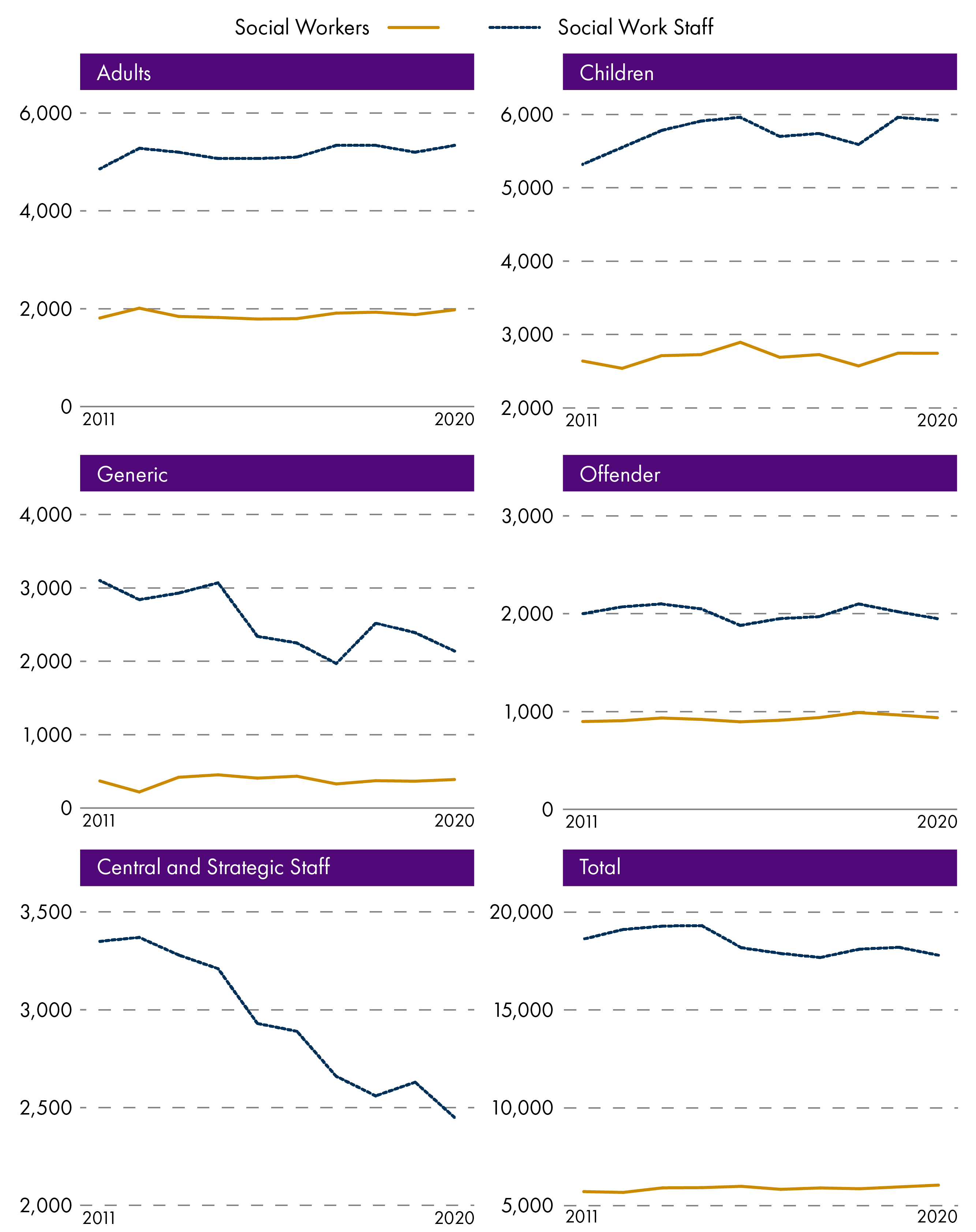

Local authority social work departments employ a range of staff in fieldwork services, including social workers, as well as in central and strategic roles, including support staff, administration and management. In 2020, local authority social work staff numbered 17,800, a reduction of 400 from 2019, continuing the overall trend of a reducing workforce in the last decade. While social work staff in adult and children's services have been increasing in number, the overall declining trend is from central and strategic staff and generic fieldwork services. Though this may partly be explained by more centralised social work administration in local authorities, which are not included in these figures1.

In 2020, there were 6,049 local authority social workers, working in a statutory setting. This is an increase of 1.5% from 2019, and 5.8% from 2011. The total number of social workers on the SSSC register also includes social workers employed in the private and voluntary sector, those working in non-practising roles and those not currently working but maintaining their professional registration. In 2020, there were 10,919 social workers on the SSSC register. This represents a 3.0% increase from 2019, but is not entirely comparable as changes to registration allowed temporary registrations as a COVID-19 measure1.

In 2020, 677 of these local authority social workers were employed as mental health officers (MHO) working for local authorities. 60% of these worked in non-exclusive MHO posts, meaning they also carry out other statutory social work for the local authority. The number of MHOs has fallen by 2.5% since 2016, and the estimated hours spent on mental health officer duties fell by 6.2%, meaning there are fewer MHOs and they are spending less time on MHO work4.

Training

Not all roles within social services require formal training and qualification. However, having or working towards a relevant qualification is a requirement for registration with the SSSC1. There are multiple routes to gaining a social services qualification including university study and work-based qualification.

In order to become a social worker, people must complete a university degree in social work. The degree became the required professional qualification for social workers in 2004. The qualification is a full four year degree programme for undergraduates, or a two year postgraduate degree. The nature of social work means these qualifications train students in relevant aspects of law, ethics, human development, social policy, and psychology. The degree has integrated placements in social service settings and practice-based assessments.

The Scottish Government outlined the framework for the professional standards that the degree should train students in, including a focus on integration of academic and practice skills and knowledge2.

Dealing with changing service demands and integration led to a review on social work education. The review concluded with a number of recommendations. In light of the recommendations, the SSSC have been revising aspects of the Standards in Social Work Education and continue to implement changes to the framework in line with the recommendations. The social work degree is therefore continuously evolving to meet changing standards of practice.

The SSSC have post registration training and learning requirements for newly qualified social workers (NQSWs). In order to keep their registration NQSWs must complete 144 hours of further study, training, courses and seminars in their first year3. Following the review of social work education, a probationary year is being proposed to supersede these requirements.

For other social service jobs, other routes are available to qualification and registration. Apprenticeships are a work-based means of getting a qualification through learning on the job. Apprenticeships usually include a primary qualification, a Scottish Vocational Qualification (SVQ) and practice experience. Apprenticeships are available to a wide range of people from secondary school pupils (foundational apprenticeship), to those already employed in the sector looking to develop their career (technical or professional apprenticeship) 4.

A range of SVQs are available for a number of social service jobs. Some SVQs are available to anyone without prerequisites, while others are for those with more experience in the sector. They are work-based qualifications that assess the skills and knowledge related to a specific role or set of roles in social services 5.

Funding for training

Funding for training is available from a number of sources. The Student Awards Agency Scotland (SAAS) provide funding for tuition fees and loan support to eligible students for undergraduate university degrees which includes social work honours degrees. Bursaries are available for postgraduate study from SSSC and include a maintenance grant alongside tuition fees for eligible students, although this funding is limited and subject to a quota.

Skills Development Scotland are a national agency that provide funding to people undertaking SVQs, with approved SVQ courses being eligible for funding of up to £200. Skills development Scotland also provide the funding for Modern Apprenticeship Centres to be able to offer apprenticeships that pay and training on the job.

Professional development

The continued professional learning (CPL) requirements for newly qualified social workers, outlined above, are 144 hours of continued learning. Continued professional learning is also required of all registered social service workers. The SSSC codes of practice outline what learning requirements are needed to maintain and improve their skills and knowledge.

The CPL requirements depend on the worker's position. Social workers must renew their registration every three years and within that time must complete 90 hours of CPL, at least a third of this must focus on collaboratively identifying, assessing and managing risks to vulnerable adults and children.

Beyond the required CPL, the SSSC aim to promote opportunities for further learning and leadership through their continuous learning framework and resources for leadership and professional development. Furthermore, some SVQs and professional or technical apprenticeships are additional qualifications available to those in the sector looking to improve their skills and knowledge to advance their careers.

Regulation

Social work in Scotland is regulated by two public bodies, the Scottish Social Services Council (SSSC) regulates the workforce, and the Care inspectorate (CI) regulates the services. Both bodies aim for public protection through regulating the sector.

The SSSC was created through the Regulation of Care (Scotland) Act 2001. The SSSC is the regulatory body for the social work, social care, and early years workforce. It aims to strengthen professionalism, raise standards of practice, and ensure the workforce is trained, trusted and skilled. It maintains registers of the workforce, sets codes of practice, regulates training and education, and investigating cases where workforce standards are not met 1.

Some people involved in social work are not registered, and therefore not regulated, by the SSSC. This includes adult day care staff, social work assistants, personal assistants, and community justice staff. SSSC have expressed concern that, as these roles have evolved in recent decades, they have become more complex and have responsibilities that require regulation, including safeguarding and assessment2.

The Care inspectorate (CI) was established by the Public Services Reform (Scotland) Act 2010. The CI superseded three regulatory bodies responsible for different elements of social care: Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Education (HMIE); the Social Work Inspection Agency (SWIA); and the Care Commission (CC). The CI inspects, regulates, and supports improvements to social care and social work services to ensure they meet the right standards. They also deal with complaints, making recommendations and outlining required improvements where care does not meet the right standard3.

Issues and challenges

There are a number of issues and challenges within the sector which affect the workforce and social work services. Limited financial resources is one of the biggest challenges and this can have wide ranging effects on the outcomes for service users, workforce wellbeing, and recruitment and retention12. There are also a number of issues that have arisen from the moves towards integration and slow progress to preventative and early intervention approaches34.

Funding issues

Excluding COVID-19 funding from Scottish Government, local authorities have had funding reductions in real terms, by 4.2 per cent from 2013-14 to 2020-21, according to the Accounts Commission1. These funding reductions have put pressure on local authority services including social work2. Increasing amounts of funding are ring-fenced for specific projects to meet Scottish Government priorities, and the Accounts Commission say this leaves local authorities with less flexibility to meet unforeseen needs1.

Despite reduced overall local authority funding, funding for social work has increased in recent years, accounting for a growing proportion of local authority funding. Expenditure on social work services has also been increasing, but is increasing by more in absolute terms4.

Increasing expenditure is primarily a result of increasing demand for services and rising service costs. Demographic changes in Scotland are seeing more older people living in Scotland5, often with more varied and complex needs6, putting demand on social work to deal with cases requiring greater resources. The Christie Commission on the future delivery of social services warned of demand outstripping the capacity to deliver services without significant resource increase.

Alongside this, there have been service cost increases. In 2021, the Scottish Government announced that local authorities were to raise the hourly rate paid to adult social care workers to £10.50 an hour in April 2022. Wage increases alongside increased national insurance and pension contributions puts further pressure on funding services. While there are clear benefits to fair work and pay policies, it increases the service costs and puts pressure on service providers 2.

Limited resources have created tension between the cost and the quality of commissioning services, with a recent Audit Scotland briefing on social care finding that the focus often ends up on costs over outcomes 8. The Independent Review of Adult Social Care (Feeley review) also highlighted that this focus on cost has been at the expense of relationship building between social work staff and clients 9, an important part of the profession. These funding pressures have led to wider pressures on the workforce and the services they can provide, with many local authorities only able to provide critical services2.

Workforce issues

There are a number of significant and intertwined challenges facing the social work services workforce. Stressful working conditions have an impact on the wellbeing of the workforce and have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Poor workforce wellbeing can impact on the retention of staff in their roles and on the services they provide to clients. Retention and recruitment of staff is an issue across the social services sector.

Workforce wellbeing

Many social work staff find their working environment challenging and this has been exacerbated to some extent by the COVID-19 pandemic. Stress at work can have an impact on staff retention and recruitment. It can also have a large impact on the mental and physical health of the workforce and on the services they deliver1.

Recent surveys into the wellbeing of social workers in Scotland have found that:

82% have experienced significant stress because of work

36% felt ‘not valued at all’

57% say their mental health has got worse during the pandemic.

1

The main factors contributing to poor workforce wellbeing and measures to address the issue are outlined below.

Workload

In studies into workforce wellbeing, workload is often cited as the greatest cause of stress 123. In a 2022 survey of social workers in Scotland, half said their workload was not at all manageable 3. Across the UK, social workers report levels of demand at work 95% worse than the UK average 2, and over 70% of workers in the UK are not able to complete their work within their contracted hours 6.

High workloads are driven by rising demand and an increase in more complex cases. Rising demand on services is mostly driven by demographic changes of an ageing population. The national policy direction to shift more care away from hospitals has led to a reduction in hospital beds. This means more support is needed outside of hospitals to be provided by social work.

Limited resources mean local authorities restrict what social work can be done. Eligibility criteria are set by local authorities based on available resources. So while everyone has a right to be assessed, often it is only the most critical and complex cases that access resources 7. This inhibits early intervention work for people with more straightforward needs. These cases can escalate to become more complex where social work intervenes at a crisis point, contributing further to workloads of complex cases.

Social workers also report a high volume of administrative tasks8. As more legislation and guidance is implemented, there are requirements for staff to collect high volumes of data, fill out paperwork and gather evidence to ensure procedure is followed 2. Cuts to social work department staff numbers have mostly been from administrative roles, meaning social workers are having to do more of these administrative tasks alongside their casework.

High job demands impact on social workers stress levels, job satisfaction, likelihood to continue working when ill and intentions to leave their role. Chronic poor working conditions also lead to poor mental or physical health of workers. These high workloads also impact on services. Limited budgets and high workloads mean time spent with clients is limited and inhibits the ability of social work staff to develop relationships 2. In a 2022 survey, almost all (96%) social workers in Scotland said lighter caseloads would mean that children would be better protected 3.

Support

Social work staff also report feeling a lack of support, which can contribute to poorer wellbeing1. Management roles in social work do not require a social work qualification2. As such, some social work staff report being managed by people without social work backgrounds who do not fully understand the nuances of the role and services. It has been reported that some social workers consider that they don't have the professional supervision they need and lack professional and ethical discussions around the decisions they make1.

The Chief Social Work Officers (CSWO) should fulfil these roles, but as social work is split across several services in local authorities (adults, children, criminal justice), CSWOs are usually operationally managing just one area. It has been suggested that CSWOs are distant from social workers where there are no line management responsibilities 4.

Beyond organisational support, many social work staff do not feel that they are respected or that the complexities of their jobs are understood by the wider public, the media and politicians1.

COVID-19 impacts on workforce wellbeing

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated pre-existing issues experienced by social work staff. Many social work staff said the pandemic adversely impacted workplace morale and individual mental health 1. Across the UK, nearly half of social workers have reported increased caseloads since the pandemic 2. Like many professions, social work staff were mostly working from home. In some cases this has meant that difficult decisions and conversations were taking place at home, without immediate support from peers or line managers3.

Almost three-fifths of social workers in Scotland (57%) reported that working during the COVID-19 pandemic had negatively impacted their mental health 3. It has also been reported that staff in the health and social care workforce across the UK adopted more negative coping strategies during the pandemic, including substance use, behavioural disengagement and self-blame. They also reported worsening work-related quality of life and burnout 5.

Addressing wellbeing

A number of initiatives to improve the wellbeing of the social work workforce have been launched in response to the impact of the pandemic. This includes the Social Work Professional Support Service, a peer support network delivered by the British Association of Social Workers with funding support from the Scottish Government. The Scottish Government also launched a wellbeing fund of £1 million in 2022. The Workforce Wellbeing Fund for Adult Social Work and Social Care is a fund for activities or items designed to improve the wellbeing of the workforce.

Furthermore, the Scottish Government has committed to increase funds to support the wellbeing of people working in Health, Social Care and Social Work as part of the National Workforce Strategy for Health and Social Care in Scotland to £12 million, although it remains to be seen how this money will be allocated and spent.

As part of the National Workforce Strategy for Health and Social Care in Scotland, the Scottish Government has also committed to allocating £22 million annually to local authorities from 2022-23 to increase the social work workforce capacity. It is hoped that expanding the workforce will help meet the rising demands of social work services.

Retention and recruitment

The recruitment and retention of staff is widely recognised as a continuing issue in parts of the social services workforce 1.

Across social services in Scotland, just over four-fifths of the staff in 2019 remained in the same post in 2020. This varies by sub-sector, with local authority social work employees employed as central or strategic staff, and generic fieldwork services having some of the lowest retention rates 2.

Alongside issues affecting wellbeing discussed previously in workforce wellbeing, a 2016 survey identified other factors that impacts retention and recruitment including a lack of career progression and training34.

The impact of working conditions on retention can be particularly significant for newly qualified social workers (NQSWs). Newly qualified social workers do not have protected caseloads to give them the time and space to work though the complexities of the job, develop the confidence in their roles and working with other agencies. In a survey of NQSWs, all reported they held large caseloads almost immediately when starting a new role. This left many feeling overburdened from the first few days on the job5.

The 2016 recruitment study cited low pay and a lack of candidates with relevant skills as the biggest challenge to recruiting social work staff. The study also found that rural authorities struggled to recruit and retain staff. They struggle to fill vacancies and the transport costs associated with large authorities and spread out populations making these areas less attractive 3. As discussed in the identity and image section later, an issue with the image of social work in the public sphere was identified. Some social work staff feel that the profession is not understood, valued or respected by wider society, which impacts on recruitment7.

Most staff in the social services believe that the high turnover has a negative impact on the quality of services they provide3.

The Office of the Chief Social Work Adviser at the Scottish Government is considering an Advanced Practice Framework to address the problems around retention and recruitment (personal correspondence with Scottish Government, 14 April 2022). The framework is expected to include proposals to create more career progression with senior practitioner roles taking on mentoring and professional management of more junior practitioners while staying in practice. Part of this package of proposals includes changes to education and training of social workers. They cover standardising education and improving training through better and more appropriate placements. There are also proposals to develop a mandatory, supported year for newly qualified social workers which would offer a standardised framework for induction, protected caseloads, professional supervision, and dedicated training time. This has been trialled in pilot schemes and the SSSC is making recommendations to the Scottish Government, based on these pilots to make the supported year a national approach 9.

Identity and image

"There is a divergence between what the profession does now (crisis support and statutory intervention) and what the profession thinks it is (early intervention and support to prevent crises)" - Alison Bavidge (SASW) - Minutes from the meeting of the cross party group on social work (19 January 2022)

The professional identity and public image of social work was identified as an issue in Changing Lives, the 2006 review of Social Work:

the “crisis” in social work is mainly a matter of professional identity that impacts on recruitment, retention and the understanding of the profession’s basic aims 1

The image and unclear or changing professional identity of social work is another problem for retention and recruitment. People within the profession across the UK report feeling not valued, respected or understood by the wider public 2.

"This boundary-spanning role can be seen as both a strength and weakness – it was evident that social work happened everywhere but no one was quite sure what it did" 3

Many social work staff in Scotland feel that promoting the image of the profession through positive stories or national campaigns would help recruitment and retention. Stories in the media and high-profile negative stories tarnish the reputation of the profession. Staff within Scottish social services more generally felt that recruitment is hindered by the sector being seen as less appealing and as having a lower status than others in education or health, for example4.

The Feeley Review also highlighted a need for an ‘explicit social covenant’ to address the lack of trust within social care support services. From this, the Social Covenant Steering Group was formed, and are tasked with building and maintaining trust in the social care system. The aim is to promote the image of the social care system and set out the values and principles that should guide the delivery of social care.

Integration issues

Integration of services on the ground has started slowly because of the complexity of the change and the challenging workforce and governance issues involved1. The implementation of integration has also led to some unintended consequences as a result of these complex structures and differing work cultures.

The complexity of the governance arrangements of integration has been highlighted as an issue of concern by Audit Scotland 2. An Audit Scotland update report on integration said that strategic planning of services can be hindered by poor collaboration in leadership and planning, high turnover in both voting and non-voting members of the IJB, disagreement in governance arrangements, as well as poor data sharing with staff and public. Where boards are tackling these issues, progress towards integration is happening quicker. The publication also reported that these issues led to tensions between local authorities, health boards and IJBs, as well as between voting and non-voting members on integration boards. Social work then finds itself within a complex structure of decision making and management which impacts on how they work on the front line. Social workers report feeling like social work loses its voice in the structure, with little or no involvement in decision making 3.

[There is] the unanticipated consequence of integration where social work and social care is currently fragmented across different public bodies in different integration arrangements

Scottish Government. (2021). A National Care Service for Scotland: consultation. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/national-care-service-scotland-consultation/documents/

The complexity of governance and decision making also complicates the funding structures. An Audit Scotland report on integration in 2015 said that local authorities and health boards work to different financial planning cycles, which means aligning funding plans for health and social care is difficult and lengthy. They often agree budgets at different times of year, and this means the IJBs can experience delays in receiving allocations to the board, making it difficult to set budgets for services 5.

The Audit Scotland update on the progress of integration also reported local authorities and health boards do not see the IJB finances as a shared resource as was intended, and both can be unwilling to give up control of their finances. This can lead to tensions between local authorities, health boards and IJBs for influence on the budget-setting process 2.

Audit Scotland reviewed financial planning for the integration progress update. The report was published in 2018 and at that time, they found that no integration authority had a long term financial plan and only one-third of IA's had medium term financial plans. Longer term plans are vital in delivering effective integration of services and progressing to preventative and early intervention approaches 2.

There are cultural differences between local authorities and the NHS, with social work and social care operating under a relational 'social model' and the NHS operating under an intervention-led 'clinical model'. Social workers feel that the NHS is more risk averse and staff are not given as much responsibility to take initiative of care 5. These constitute different ways that healthcare providers and social workers view their jobs coming from very different roles, regulatory frameworks, governance systems and training 9. These cultural differences in ways of carrying out and understanding the work are barriers to fully integrated services. The cultural difference can also be reflected in the boards and the decision makers for services, with social workers not always feeling the nuances of their profession are fully understood by those making the decisions for it.

These cultural differences, especially from the IJB can have a negative impact on the wellbeing of the workforce, and a feeling that their professional identity is diminished.

Respondents described an overarching culture which comes from sources external to their organisation which was damaging to morale and increasingly stressful

Ravalier, J. (2018). UK Social Workers: Working Conditions and Wellbeing. Retrieved from https://www.basw.co.uk/resources/uk-social-workers-working-conditions-and-wellbeing-0

Few IJBs have longer-term plans and so there has been slow progress to early intervention and prevention approaches to social work11, with some local authorities and IJBs having a much greater focus on early intervention than others. The need to allocate resources to community and preventative approaches was outlined in the Christie Commission for future delivery of social services in 2011, but there has been little change with resources still often tied up in short term problems and focused on crisis and high-tariff intervention 12. The savings from preventative approaches may not materialise for many years, which makes it difficult to include when most strategic plans are short or medium term 11. Social workers already feel overstretched with high caseloads of crisis work, that they have little or no time to spend on preventative work. Furthermore, it can be difficult to persuade the public of the long term benefits of preventative approaches when they require reduced funding for other services, for instance shutting down a care home to free up funding for community based care projects 11.

Service delivery and consistency issues

The complex arrangements of integration and decisions taken by each local authority means services are adapted for local context, but also that services are inconsistent across the country.

Despite 'consistency of practice' being a part of the framework of standards for self-directed support (SDS), there is still a mixed picture of delivery across the country, with evidence suggesting that some people do not have full access 1. Where there is full access to all options, it works well and people benefit from having more control of their care2, but studies have shown that traditional care culture has changed little since the implementation of SDS, and local authorities directly delivering services remains the dominant provision of SDS 34. Some user experiences of SDS suggest that social work staff are not discussing all options with them, or that they felt they had not made the choice2. There is variation in the eligibility criteria for accessing care services, as well as the process for resource allocation after assessments. On top of this, there is evidence that social workers may game the system, inflating people's needs in assessment so they can access care. All this leads to different delivery of service and access to care through self-directed support between local authorities 1.