Will fishing be discarded in the Brexit negotiations?

This briefing explores how the catching sector of the UK's fishing industry may fare in Brexit negotiations on the future relationship between the UK and the EU. It looks at how other countries outside of the EU have negotiated with the EU with regards to access to waters and trade in seafood. The briefing also highlights the importance of fishing to Scotland's economy compared to the UK as a whole.

Executive Summary

When the UK leaves the European Union, it will become an independent coastal state, meaning that it will have full control over fisheries governance and access to waters in its Exclusive Economic Zone.

The extent to which the UK will allow access to its waters to EU vessels will depend on negotiations on the UK's future relationship with the EU.

In March 2018, the UK and EU reached an agreement on the transitional period after the UK's withdrawal from the EU in March 2019. During this period, the UK will continue to be bound by the rules of the Common Fisheries Policy but will be "consulted" by the EU during relevant fisheries negotiations but will not be a full participant.

Some stakeholders are concerned that negotiations may provide reciprocal access for UK and EU fishing vessels in exchange for access to markets for seafood products. These arrangements have previously been negotiated between the EU and third countries such as Norway, Iceland, Greenland and the Faroe Islands.

Fishing contributes less than 1% to the Scottish economy and UK economy as a whole, whether measured by number of jobs or value added. However it's contribution to the Scottish economy is greater than to the UK economy as a whole. Fishing is also disproportionately more important in terms of employment and economic contribution in rural communities.

Introduction

As a member of the European Union, the UK's fisheries are primarily governed by the EU under the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP), with fisheries management undertaken by the UK Government and devolved administrations. The UK is bound by EU law, which dictates certain technical aspects of fishing (e.g. gear restrictions, minimum landing sizes, etc), as well as rules relating to fishing opportunities (e.g. quotas and effort controls) and access to fishing grounds.

When the UK leaves the European Union, it will become an independent coastal state, meaning that it will have full control over fisheries governance and access to its waters out to 200 nautical miles (known as an Exclusive Economic Zone or EEZ) or to the edge of its established maritime boundaries with neighbouring coastal states. As a coastal state, it will be able to set a total allowable catch and other management measures for fish within its EEZ. It will also be able to determine which vessels may fish within this area.

However, the UK will still be bound by international law under the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the 1995 United Nations Fish Stock Agreement. This will require co-operation on the management of shared stocks that occur in one or more neighbouring EEZs, as well as in relation to stocks that straddle or migrate between the EEZ and adjacent high seas.

The extent to which the UK will allow access to its waters to EU vessels will depend on negotiations on the UK's future relationship with the EU. This will be achieved through bilateral and/or multilateral fisheries agreements or other ad hoc arrangements. Some stakeholders are concerned that arrangements over access may also be influenced by negotiations on future trading arrangements between the UK and the EU.

Why is the fishing industry concerned?

The Scottish Fishermen's Federation (SFF) want to see an end to current quota arrangements which they believe give too much of the UK's fish stocks to EU vessels. They see leaving the EU as an opportunity to take back control of the UK's EEZ.1

The SFF is also concerned that current arrangements on access to the UK's water and fish stocks for EU vessels under the Common Fisheries Policy may be maintained after Brexit as part of a free-trade agreement with the EU. In a joint statement, with the National Federation of Fishermen’s Organisations (NFFO) it states:

The EU’s stated preference for a free trade deal in return for access to fish in UK waters and quota shares is an absurd attempt to maintain the current unbalanced arrangement which results in 60% of the UK’s natural fish resources being given away. Acceptance of such an unprecedented and unprincipled link by UK negotiators would be regarded by the entire UK fishing industry as a gross betrayal and have grave electoral consequences.2

What has been agreed for the transition period?

In March 2018, the UK and EU reached an agreement on the terms of the UK's withdrawal from the EU. The agreement includes a transitional period after the UK leaves the EU in March 2019, ending on 31 December 2020.

As part of the terms of agreement, the UK will continue to participate in the Common Fisheries Policy until the end of the transition period. The text of the draft withdrawal agreement published in March 2018 states that the UK will be “consulted by the European Commission in respect of the fishing opportunities related to the United Kingdom” as opposed to playing an active role in negotiations as a member of the EU.1

The agreement outlines specific arrangements on how the EU will consult with the UK and includes a statement that the EU “may exceptionally” invite the UK to be part of the EU delegation at international negotiations. It also maintains the relative stability keys for the allocation of fishing opportunities, meaning that the proportion of quotas assigned to EU Member States will remain in place.

The Scottish Fishermen's Federation reacted to the agreement stating:

This falls far short of an acceptable deal. We will leave the EU and leave the CFP, but hand back sovereignty over our seas a few seconds later. Our fishing communities’ fortunes will still be subject to the whim and largesse of the EU for another two years.

On 20 March 2018, Michael Gove, Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs made the following statement on the transition agreement to the House of Commons:

Our proposal to the EU was that, during the implementation period, we would sit alongside other coastal states as a third country and equal partner in annual quota negotiations. We made that case after full consultation with the representatives of the fisheries industry. We pressed hard during negotiations to secure this outcome, and we are disappointed that the EU was not willing to move on this.

However, thanks to the hard work of our negotiating team, the text was amended from the original proposal, and the Commission has agreed amendments to the text that provide additional reassurance. The revised text clarifies that the UK’s share of quotas will not change during the implementation period, and that the UK can attend international negotiations. Furthermore, the agreement includes an obligation on both sides to act in good faith throughout the implementation period. Any attempts by the EU to operate in a way that harmed the UK fishing industry would breach that obligation.

The full debate following the Secretary of State's statement can be viewed below.

Negotiations on the UK's future relationship with the EU

Inclusion of a transition period will form part of the overall Article 50 Withdrawal Agreement. So far, elements of the Withdrawal Agreement have been agreed including the terms of the transition period, but until all elements of withdrawal have been finalised, and the agreement is ratified by the EU and the UK, the individual elements that make up the Withdrawal Agreement cannot be signed off.

The Withdrawal Agreement is also likely to include high-level principles setting out the basis for the future relationship between the EU and the UK after the transition period has ended. These high-level principles will inform the detailed negotiations on the future relationship.

There have been assurances from the UK Government that fishing will not be sacrificed for a favourable trade deal. David Mundell MP, Secretary of State for Scotland told the Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Relations Committee on 22 February 2017:

I make this absolutely clear, since it is occasionally referenced in the media—is that there is absolutely no situation in which fishing will be a bargaining chip in the negotiations. It is a very important industry here in Scotland and I very much welcome its positive approach.

Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Relations Committee 22 February 2017, David Mundell, contrib. 143, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=10801&c=1976971

However, In March this year, Chancellor of the Exchequer, Phillip Hammond MP stated that the UK Government would be "open to discussing with our EU partners about the appropriate arrangements for reciprocal access for our fishermen to EU waters and for EU fishermen to our waters"2

In an evidence session of the Rural Economy and Connectivity Commmittee 6 June 2018 Cabinet Secretary for Rural Economy and Connectivity, Fergus Ewing said:

On several occasions, I have asked Mr Eustice and Mr Gove, and Mrs Leadsom before Mr Gove’s appointment, for confirmation that access rights will not be traded away permanently as part of quid pro quo in an EU deal, perhaps over access to the single market. Sadly, I have had no answer to that.

The European Commission make it clear that its objective in negotiations for a future trade deal is for continued reciprocal access between the UK and EU waters. The draft negotiating guidelines for a future trade deal states:

Trade in goods, with the aim of covering all sectors, which should be subject to zero tariffs and no quantitative restrictions with appropriate accompanying rules of origin. In this context, existing reciprocal access to fishing waters and resources should be maintained.

Can access to the UK's waters be traded for access to EU markets?

As a member of the EU, the UK currently has tariff-free access to the EU market for exports of fish and fish products. This is beneficial to the industry because the UK exports up to 80% of its seafood, the majority of which goes to destinations in the EU. However, it must also allow vessels from other EU member states to fish within its EEZ and some EU fishing vessels have rights to access certain fishing grounds within the territorial sea (0-12 nautical miles).

Once the UK leaves the EU, these arrangements may be renegotiated. The UK Government has also announced its withdrawal from the London Fisheries Convention meaning that the UK will have control on access to its territorial sea in addition to control of its EEZ.

Article 11.2.7 of the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries advises against trading access to natural resources for market access.

States should not condition access to markets to access to resources. This principle does not preclude the possibility of fishing agreements between States which include provisions referring to access to resources, trade and access to markets, transfer of technology, scientific research, training and other relevant elements. 1

The Code of Conduct represents international best practice, but it is not legally binding. In practice, states are able to reach whatever arrangement they like in the negotiation of trade agreements, depending upon their precise circumstances and political expediency.

How has the EU negotiated with third countries in the past?

There have been cases in the past in which negotiations between the EU and third countries have resulted in the EU gaining access to fish stocks in exchange for access to the single market.

Although it is not comparable to the UK in terms of its population and economy, Greenland's negotiations for a bilateral agreement with the EU provides an interesting case. Greenland voted to leave the EU in 1982 and negotiations were not completed until 1985.1Negotiations took three years to complete despite fisheries being the main issue for negotiations and access rights for EU vessels were still conceded.2

In an article published by Politico on 22 June 2016, Lars Vesterbirk, Greenland’s former representative to the EU who led the negotiations is quoted as stating:

The EU got almost the same amount of fishing rights they had before, and we had the same amount of money for our fish...1

There is also a free trade agreement between the EU and the Faroe Islands, under which the Government of the Faroe Islands state that they are able:

"to export most of its fish products to the EU market. There remain nevertheless, quantitative restrictions on some areas of vital importance for the Faroese industry."4

At the same time, the Faroe Islands retains control over access to its waters for EU vessels, which it negotiates on an annual basis under a bilateral fisheries framework agreement concluded with the EU.

On 30 May 2018, an own-initiative report by rapporteur Linnéa Engström MEP endorsed by the European Parliament Fisheries Committee was adopted by the European Parliament. Although adoption of the text has no legislative basis, it signals the opinion of the European Parliament with respect to access for EU vessels to the UK's waters.

The text adopted by the European Parliament in plenary (adopted by 590 votes to 52, with 41 abstentions) on 30 May 2018:

Calls on the Commission, when drafting a post-Brexit agreement, to make the UK’s access to the EU market for fishery and aquaculture products dependent on EU vessels’ access to British waters and on the application of the CFP. (Para. 24).5

Tariffs on seafood exported to the EU

Tariffs on seafood exports to the EU after Brexit will depend on the UK's future trading relationship with the EU. A free-trade agreement, with zero tariffs on fish and fish products is a top priority for seafood processing stakeholders.1

Outside of a free trade agreement, tariffs are particularly high for processed fish products. Under the EU’s Most Favoured Nation tariff lines, tariffs on fish products range from 0% for some fresh products to 25% for highly processed products. For the top five fish products exported from the UK to the EU, the tariff lines for non-preferential trade ranged from 2% on Atlantic salmon to 20% on frozen mackerel in 2014.2

The current EU tariff landscape provides for three broad arrangements:

No tariff: through membership of the EU Single Market or the EU Customs Union

Reduced tariff: through preferential arrangements or trade agreements

Full tariff: countries outside the EU without preferential agreements or trade agreements and operating under WTO rules.

These tariff arrangements are summarised in more detail in the box below.

No tariff: Seafood of EU origin can be transported freely between member states of the EU without commanding any tariff. Seafood imported into the EU and which has been cleared by Customs at the border (and any duties paid) is also in free circulation within the EU. The EU has a Customs Union with four non-EU states: Turkey, Andorra, Monaco and San Marino.

Quota-dependent tariffs (reduced tariff): Fishery products that are covered by autonomous tariff quotas (ATQs) during 2016–2018 are listed in Council Regulation 2015/2265. ATQs provide either total or partial suspension of duties for a limited period and for a limited quantity. The EU also provides a small number of tariff quotas for specific seafood products exported from particular countries e.g. Norway, Iceland and Serbia.

Preferential arrangements (reduced tariff): The General System of Preferences (GSP) provides developing countries access to EU markets. Overseas countries and territories (OCTs) are countries such as the Falkland Islands and Saint-Pierre and Miquelon which are linked to member states but outside the EU. Exports from OCTs to the EU benefit from tariff preferences.

Trade agreements (reduced tariff): The EU has trade agreements with several countries or blocs, including the members of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA: Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway), Switzerland, Morocco, Mexico, South Korea, CARIFORUM, etc. Seafood imported into the EU from these countries benefit from preferential tariffs which occasionally may be quota dependent.

Full tariff: Seafood imported from countries without a preferential arrangement or not as part of a tariff quota will be subject to the full EU tariffs, known as the Most Favoured Nation (MFN) tariffs.3

Source: adapted from Seafish

The UK is also a net importer of seafood, the majority of which comes from the EU. Tariff-free trade on seafood as part of a free trade agreement between the UK and EU may therefore be mutually beneficial.

However, a free trade agreement could take many years to negotiate. For example, the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) took 7 years to negotiate. It is unclear what arrangements would be put in place in the intervening period during any negotiations for a free trade deal with the EU.

Even within the European Economic Area (EEA), tariffs are relevant. Evidence provided to the House of Lords Select Committee on the European Union indicated that Norway and Iceland (outside the CFP and customs union) are subject to tariffs on certain fish and fish products despite trading within the EEA.

For example, Norwegian exports of white fish to the EU are tariff free, but range from 2-25% to other valuable species.2 In written evidence to the House of Lords European Committee inquiry on Brexit: fisheries, Kristin Alnes of the Norwegian Seafood Federation states:

The lack of free trade with the EU is very difficult for us and has been a problematic area for years. Our fish become more expensive and our exporters have less income.

This difficulty is reflected in the Scottish Government's official position, which, as part of its ‘enhanced EEA option’, has argued that.

given that most agricultural and seafood products traded from EFTA-EEA countries to the EU are subject to tariffs, the UK Government needs to negotiate for tariff-free access to the Single Market for these products and we will press for this. (para. 96)5

How important is fishing to the UK and Scottish economy?

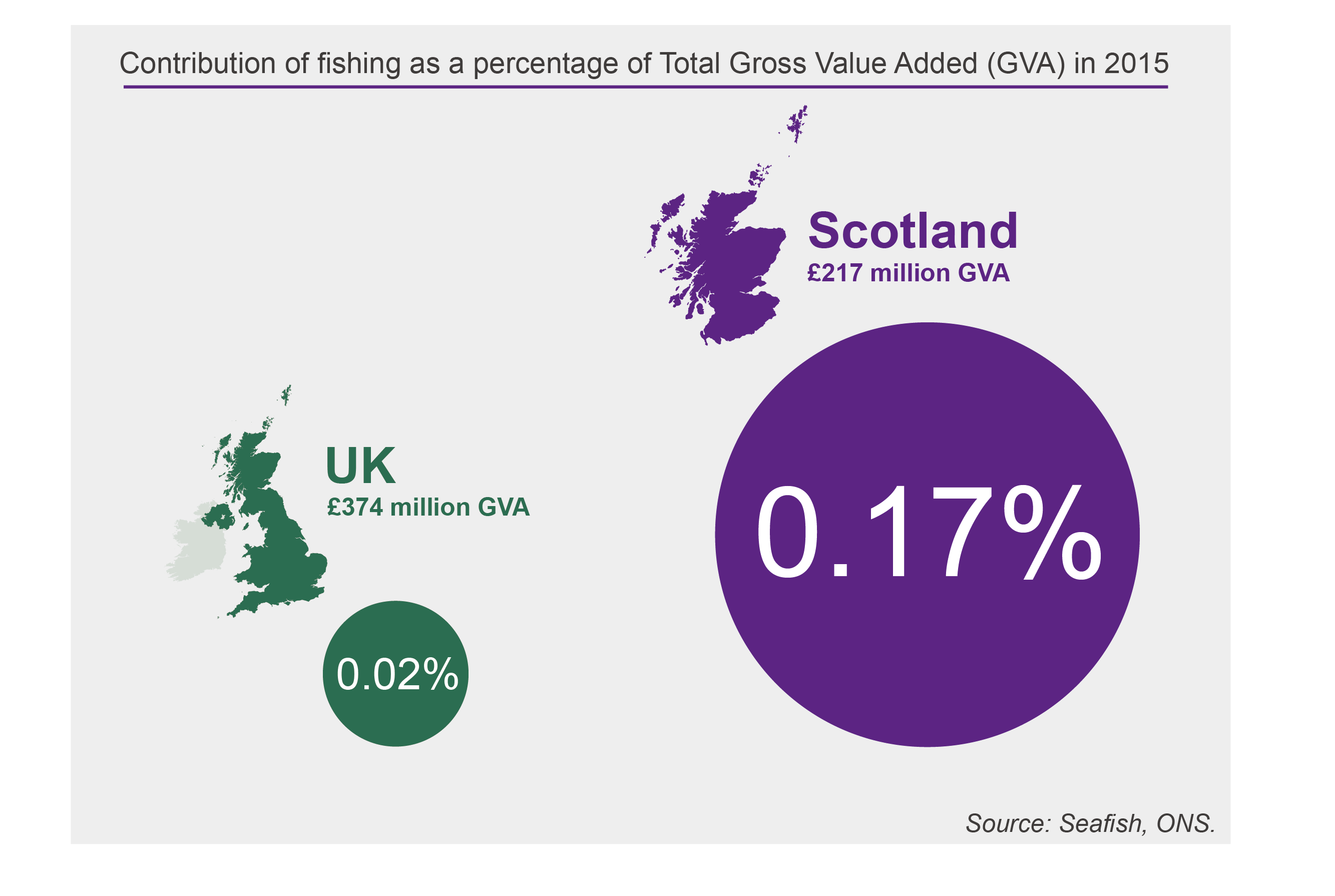

Outside the political discussion, economic statistics show the importance of fishing to the Scottish Economy. Figures from Seafish show that UK vessels contributed £373.5 million in Gross Value Added (GVA) to the UK economy in 2015. This accounted for 0.02% of the UK’s total GVA (total GVA is obtained from the Office for National Statistics). Scottish vessels contributed £216.8 million, accounting for 0.17% of Scotland’s total GVA.1 In other words, sea fisheries contributed 8.5 times more to Scotland’s economy in 2015 than to the UK economy as a whole.

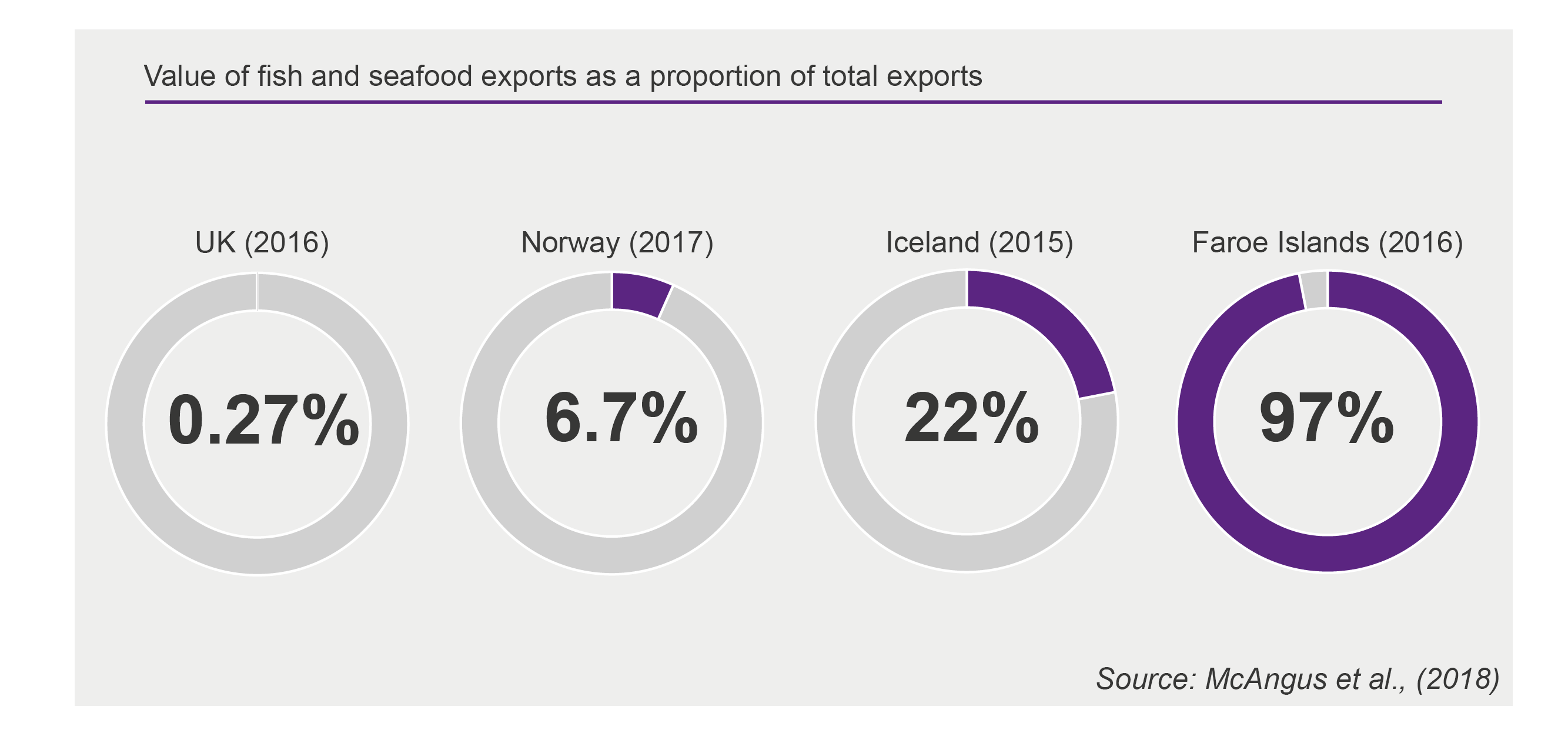

The contribution of fishing to the UK's economy is especially pertinent in light of lessons learned from negotiations between the EU and third countries such as Greenland, Iceland, Norway and the Faroe Islands, where seafood exports account for a far greater proportion of total exports.4

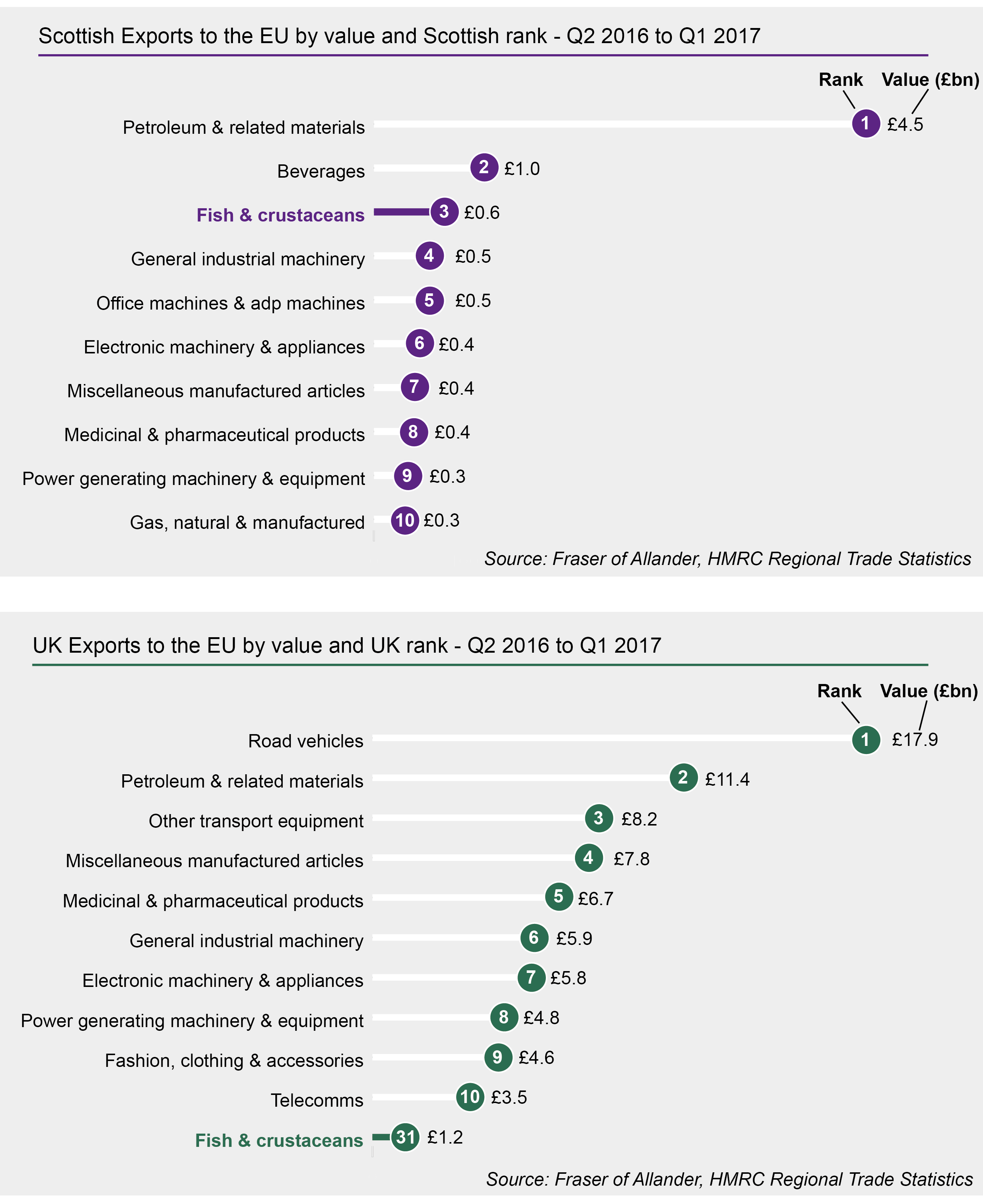

Analysis by the Fraser of Allander Institute shows that fish and crustaceans rank 31st in UK exports to the EU in terms of value in 2016/17. In Scotland it was the third highest export to the EU behind beverages and petroleum.6However, these statistics also include farmed salmon and therefore may overestimate the value of sea fish exported to the EU.

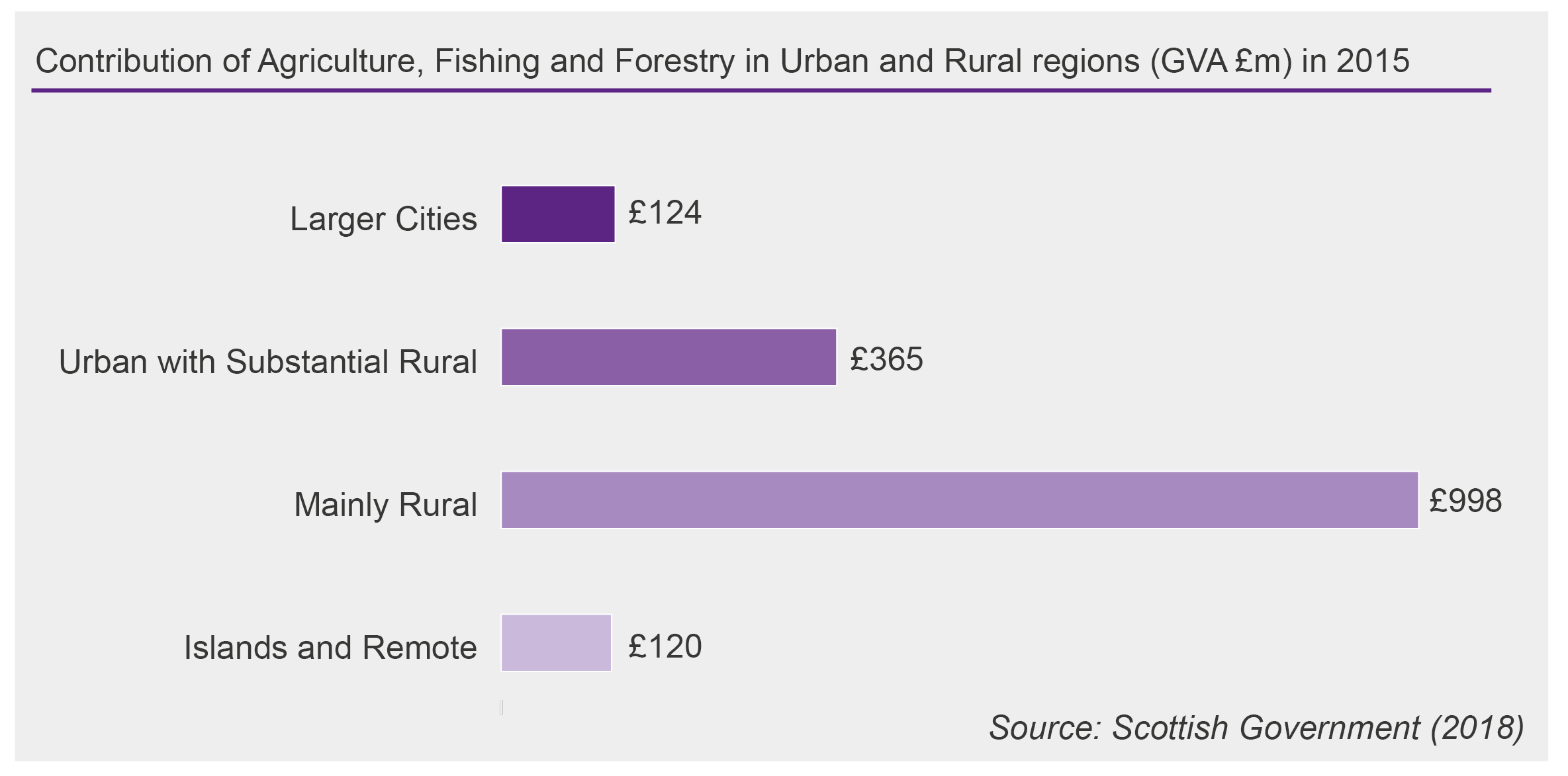

Although fishing's contribution to the Scottish economy and the UK economy as a whole is small, it has a greater contribution to the rural economy than other regions. A recent Scottish Government report – Understanding the Scottish Rural Economy – shows that agriculture, forestry and fishing contributed £998 million GVA in ‘mainly rural’ areas compared to £124 million in ‘larger cities’ in 2015.9

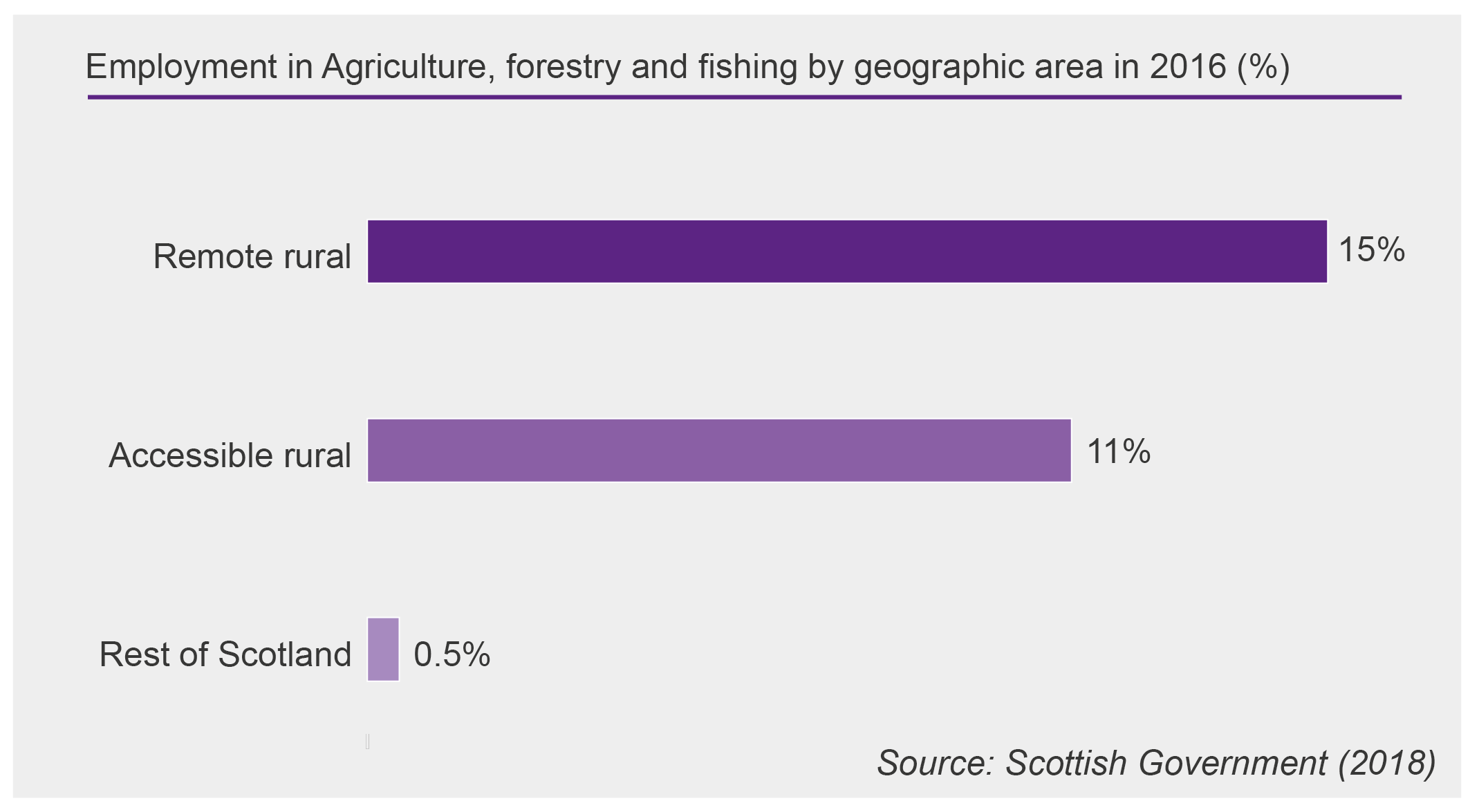

The report also shows that 15% of people in ‘remote rural’ areas are employed in this sector, compared to 11% in ‘accessible rural’ and 0.5% in the rest of Scotland.

According to Seafish, Scottish registered vessels had the highest number of full-time employees in the UK fleet in 2015 with 4,180 FTEs.1