Common UK Frameworks after Brexit

The briefing discusses the creation of common frameworks between the UK and devolved governments that will come into effect after Brexit.This briefing has been written for SPICe by Akash Paun, a Senior Fellow of the Institute for Government, with research assistance from Jack Kellam.The views expressed by the author are his own and do not represent the views of SPICe or of the Scottish Parliament

Summary

This research paper discusses the creation of ‘common frameworks’ between the UK and devolved governments to come into effect after Brexit. Common frameworks applying across the United Kingdom (or, in some cases, Great Britain) are expected to be established in a number of policy areas that fall within the legislative competence of the devolved institutionsi, while also being subject to EU law.

The UK and devolved governments have agreed on broad principles to guide the establishment of these frameworks. The next phase of the process is to identify precisely where such frameworks are required, what form they should take, and how far they should seek to constrain policy differentiation between the nations. Reasonable progress has reportedly been made in discussions between the governments, but at time of writing there is very little information in the public domain about what has and has not been agreed, and what will happen next. This paper seeks to shed light on these and related issues.

What are ‘common frameworks’ and why are they needed?

The UK government has identified 142 distinct policy areas that fall into the ‘intersection’ between EU law and devolved legislative competence in at least one of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland (see Annex). Since all devolved legislation must be compatible with EU law (specified, for instance, in section 29 of the Scotland Act 1998), membership of the EU ensures legal and regulatory consistency across the UK in these areas.

That does not imply, however, that there is complete regulatory uniformity in these areas. The degree to which the four nations of the UK are bound by the same legal requirements depends on the nature of EU law in that domain. In some cases, the EU specifies minimum standards, for instance in relation to aspects of environmental quality, but with discretion for different countries and territories to decide how to reach the benchmarks (or whether to exceed them). In other areas, EU law is more prescriptive and detailed, and allows little variation in how it is implemented. An important distinction in this regard is between ‘Directives’ and ‘Regulations’. As per Article 288 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union:

A regulation shall have general application. It shall be binding in its entirety and directly applicable in all Member States.

A directive shall be binding, as to the result to be achieved, upon each Member State to which it is addressed, but shall leave to the national authorities the choice of form and methods.

EurLex. (n.d.) Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. Retrieved from http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:12012E/TXT&from=EN [accessed 25 January 2018]

A central argument for common UK frameworks is that if they are not created, then once the UK ceases to be bound by EU law, the potential for policy divergence within the UK will significantly increase. Policy variation between the four nations of the UK is not, of course, inherently problematic. Indeed, the very rationale of devolution is to enable policy differentiation in response to local circumstances, and so lessons can be learnt about which approaches work best (as part of a ‘policy laboratory’).2 However, the absence of common standards could in some areas have negative consequences, for instance by imposing new burdens on business or undermining coordination in tackling cross-border policy issues. The difficult task is to identify where the potential negative effects of policy variation are serious enough to necessitate constraints on devolved policy autonomy.

Where did the idea of common frameworks come from?

In the aftermath of the referendum result, the importance of involving the devolved governments in the exit process was recognised by the UK Government. In her first week as Prime Minister Theresa May committed that she would not commence the Brexit process without first reaching agreement on a ‘UK-wide approach and objectives’.1 This aspiration was subsequently embedded in the terms of reference of the Joint Ministerial Committee on European Negotiations, although in the event, the UK Government unilaterally decided upon both the timing and the content of the ‘Article 50’ withdrawal notification letter.

The initial focus of the debate about Brexit and devolution was whether and how agreement could be reached on the terms of exit and the future UK-EU relationship, given the very different positions adopted by the respective administrations. There was also discussion about the repatriation of powers from the EU and how the competences of the devolved institutions might be affected. There was less attention paid initially to the creation of new UK-wide frameworks which would be needed to replace EU law.

The Institute for Government noted in October 2016, in a study of the impact of Brexit on the territorial constitution, that:

There might be a desire to create new UK-wide coordinating systems to replace the EU-wide systems the country will be leaving. The concern may be that having left the EU Single Market (assuming this is the outcome), steps will need to be taken to ensure that the UK Single Market does not itself fragment. This might therefore require regulatory standardisation, for instance to prevent a race to the bottom or other unintended spillover effects.

Paun, A., & Miller, G. (2016). [No description]. (n.p.): (n.p.).

The UK Government itself publicly identified the need for common frameworks in January 2017, when Prime Minister Theresa May stated that:

Our guiding principle must be to ensure that – as we leave the European Union – no new barriers to living and doing business within our own Union are created, that means maintaining the necessary common standards and frameworks for our own domestic market, empowering the UK as an open, trading nation to strike the best trade deals around the world, and protecting the common resources of our islands.

UK Government. (2017, January 17). ‘The government’s negotiating objectives for exiting the EU: PM speech’. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/the-governments-negotiating-objectives-for-exiting-the-eu-pm-speech [accessed 25 January 2018]

Despite continuing UK-devolved disagreement about the terms of Brexit, it is worth noting that in this same period the Scottish and Welsh Governments also recognised the need for new arrangements to facilitate cooperation within the UK in areas currently governed by the EU. In its December 2016 White Paper Scotland’s Place in Europe the Scottish Government recognised that:

There may be a need to devise a cross border framework within the UK to replace that provided by EU law, for example in relation to animal health, that should be a matter for negotiation and agreement between the governments concerned, not for imposition from Westminster.

Scottish Government. (2016, December 20). Scotland's Place in Europe. Retrieved from http://www.gov.scot/Publications/2016/12/9234 [accessed 25 January 2018]

On 23 January 2017, the Welsh Government then published Securing Wales’ Future, in collaboration with Plaid Cymru, noting that:

We recognise that in some cases, in the absence of EU frameworks which provide an element of consistency across the UK internal market, it will be essential to develop new UK-wide frameworks to ensure the smooth working of the UK market.

Welsh Government. (2017, January 23). Securing Wales’ Future. Retrieved from https://beta.gov.wales/brexit [accessed 25 January 2018]

The UK Government developed its position further in its February 2017 white paper The United Kingdom’s exit from and new partnership with the European Union, promising that:

We will maintain the necessary common standards and frameworks for our own domestic market, empowering the UK as an open, trading nation to strike the best trade deals around the world and protecting our common resources.

UK Government. (2017, February 2). The United Kingdom’s exit from and new partnership with the European Union. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-united-kingdoms-exit-from-and-new-partnership-with-the-european-union-white-paper [accessed 25 January 2018]

Further detail was then provided in the March 2017 Great Repeal Bill white paper, which explained:

Examples of where common UK frameworks may be required including where they are necessary to protect the freedom of businesses to operate across the UK single market and to enable the UK to strike free trade deals with third countries. Our guiding principle will be to ensure that no new barriers to living and doing business within our own Union are created as we leave the EU.

UK Government. (2017, March 30). The Repeal Bill: White Paper. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-repeal-bill-white-paper [accessed 25 January 2018]

What has been agreed on creating new common frameworks?

Despite these signs of common ground between the governments, progress toward reaching agreement on Brexit appears to have halted, or gone into reverse, in early 2017. This is reflected in the fact that after four meetings in four months, the JMC(EN) ceased operating between February and October 2017.

In this period, the UK Government took a series of major decisions about Brexit that were opposed by the devolved governments, including the submission of the Article 50 letter and the publication of the EU Withdrawal Bill. Intergovernmental dialogue (including at civil service level) also appears to have been undermined by the wider political context, including the 2017 general election campaign and the decision by the Scottish Government to place a second independence referendum on the agenda.

The summer of 2017 was marked by the start of a serious disagreement about the EU Withdrawal Bill, Clause 11 of which provided that all powers exercised in Brussels would return to Westminster, before potentially being ‘released’ to the devolved institutions on a case-by-case basis. The bill sets as a default that Westminster alone could legislate to replace EU legal frameworks, by preventing the devolved legislatures from amending ‘retained EU law’. Negotiations are ongoing about how to amend the bill in order that it can receive legislative consent from the Scottish Parliament and Welsh Senedd. Without agreement on the bill, it is hard to imagine how the UK and devolved governments will be able to work together effectively to create and manage common frameworks.

At the October 2017 meeting of the Joint Ministerial Committee on EU Negotiations (JMC(EN)), the four governments (with Northern Ireland represented by civil servants) agreed that common frameworks should be established where they are necessary to:

enable the functioning of the UK internal market, while acknowledging policy divergence;

ensure compliance with international obligations;

ensure the UK can negotiate, enter into and implement new trade agreements and international treaties;

enable the management of common resources;

administer and provide access to justice in cases with a cross-border element;

safeguard the security of the UK.1

It was also agreed that any frameworks would ‘maintain, as a minimum, equivalent flexibility for tailoring policies to the specific needs of each territory as is afforded by current EU rules’, and that the overall effect would be ‘a significant increase in decision-making powers for the devolved administrations.’ The UK government also reiterated that adjustments to devolved competence would only be made with consent.

The October agreement thus marked a significant breakthrough in UK-devolved relations.2 It was the first joint statement between all four governments about any substantive aspect of Brexit. The statement also represented a sensible and balanced package of principles, in the view of the Institute for Government, in that it set out a set of objective tests for when frameworks should be created, while also committing to respect and extend the devolution settlements.

However, this agreement was at the level of broad principle, leaving major questions unanswered about how the principles will be interpreted, where common frameworks will therefore be established, and what form they should take. With the fate of the EU Withdrawal Bill still in the balance, it is crucial that swift progress is made in answering these questions.

Where will common frameworks be needed?

According to analysis carried out within Whitehall, there are 142 policy areas currently subject to EU law that fall within the competence of at least one of the Scottish Parliament1, Welsh Senedd2 or Northern Ireland Assembly3 (see Annex A). A total of 111 areas fall into this ‘intersection’ of EU and devolved power in the Scottish case. This is more than the 64 areas of intersection identified for Wales, but fewer than the 141 in the case of Northern Ireland, reflecting differences in the three devolution settlements.

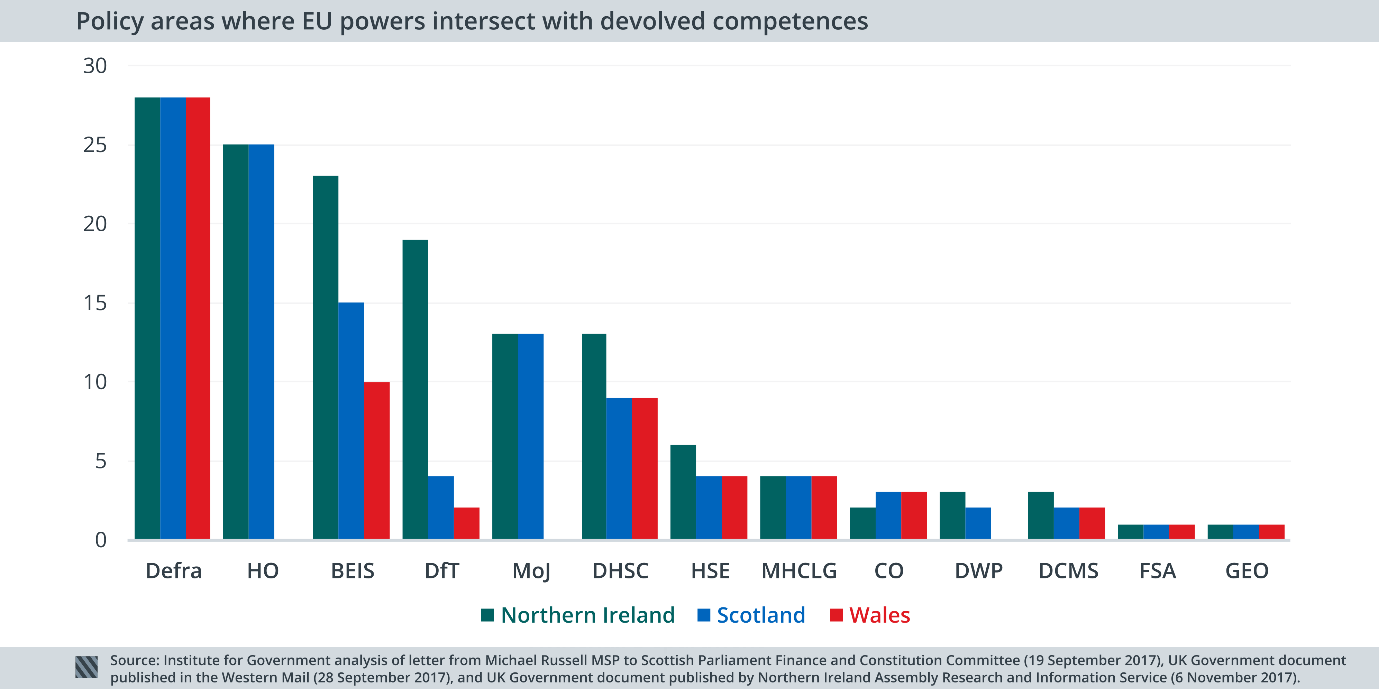

As shown in figure 1, when categorised by lead Whitehall department, the Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) is most affected, with 28 areas of intersection between EU and devolved power. These span almost the entirety of Defra’s responsibilities, including 14 different aspects of environmental quality, as well as agriculture, fisheries, forestry and animal welfare.

Next on the list is the Home Office (HO) where there are 25 areas that are devolved to Scotland and Northern Ireland (though not Wales) and subject to EU law. These include data sharing requirements (for instance through the EU fingerprint database), minimum standards legislation for certain crimes (such as football disorder and human trafficking), cross-border cooperation in law enforcement (for instance to facilitate action on organised crime), and participation in EU agencies such as Europol.

The Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) is also responsible for over 20 areas of EU law that are devolved to at least one part of the UK. In the case of Scotland, these relate to issues including energy efficiency, carbon capture, onshore hydrocarbons licensing (fracking), and environmental law.

Other departments with a significant number of areas on the list include:

The Department for Transport (DfT), although principally for Northern Ireland, which has various additional devolved powers, for instance over railways and vehicle registration.

The Ministry of Justice (MoJ), relating to EU arrangements for civil judicial cooperation, mutual recognition of criminal court judgments, legal aid and victims’ rights.

The Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), relating for instance, to the right of EEA citizens to access healthcare in the UK, and around issues such as tobacco regulation and blood safety.

In total, 13 UK government departments and bodies have responsibility for policy areas with both an EU and devolution dimension.

Figure 1: Areas of intersection between EU law and devolved legislative competence

Will common frameworks represent a ‘recentralisation’ of power to Westminster?

For each of the areas mentioned, powers currently exercised by the EU are expected to be repatriated to the UK, subject to the terms of Brexit and the future UK-EU relationship. The large number of policy areas included in the list, in conjunction with the provisions in the EU Withdrawal Bill, has given rise to fears of a recentralisation of power to Westminster. There are valid concerns, especially about the terms of the bill, but common frameworks themselves need not mark a power transfer to the centre. The following points should be borne in mind.

First, frameworks are not expected in all the areas where EU law ceases to apply. In many cases, there is no reason not to allow full policy autonomy for each UK nation, or indeed positive reasons to welcome differentiation. The test is whether a framework is required for one of the six reasons agreed at the JMC(EN) in October. The problem is the absence of clarity or transparency about how the principles are being defined and put into practice. This is a particular issue with regard to the first principle relating to ‘the functioning of the UK internal market’, which is a vague concept that could be interpreted in various ways that are more or less conducive to policy differentiation within the UK.

Second, even where common frameworks are deemed necessary, they will not necessarily extend to the entirety of the policy area in question (particularly true for broad categories on the list such as ‘energy efficiency’, ‘land use’ and ‘forestry’). It is agreed that any existing devolved flexibility will be preserved, so new frameworks should at the most constrain devolved policy autonomy only to the extent it is currently constrained by the EU. It is also agreed that overall, there will be a significant extension of devolved powers. These are important principles that provide an important counterbalance to the potentially centralising logic of the six reasons for why frameworks might be needed. As the process of developing frameworks moves forward, the various governments must be held to account for ensuring that all these principles are respected.

Third, ‘common framework’ is an umbrella term for a range of different arrangements that might be established, which might vary widely in terms of how much they seek to limit policy divergence. This is made clear in the October 2017 joint statement:

A framework will set out a common UK, or GB, approach and how it will be operated and govered. This may consist of common goals, minimum or maximum standards, harmonisation, limits on action, or mutual recognition, depending on the policy area and the objectives being pursued.1

Fourth, a crucial distinction should be drawn between legislative and non-legislative frameworks, since only the former could create legally-enforceable standards or regulations. The latter would rest upon the identification of shared objectives and the continued willingness of the UK and devolved governments to cooperate. We now explore this distinction in more detail.

Will common frameworks require legislation?

Over the past few months, private discussions have been under way between the UK and devolved governments not only about which policy areas will require any form of common framework, but also about where legislation will be needed.

In many cases non-statutory agreements between the governments are likely to be sufficient. However, legislation is likely in a small subset of sectors, possibly including politically-sensitive areas such as agricultural support and management of fisheries, as well as technical areas where the costs of having separate regulatory systems would be disproportionate (for instance, chemicals regulations and animal health). Legislation to create such frameworks would be expected to pass through the UK Parliament, but subject to the legislative consent or ‘Sewel’ convention. On 30 January 2018, the Leader of the House of Lords confirmed that the Government would shortly be publishing an ‘initial framework analysis’ and that UK-wide legislative frameworks would be created in ‘only a minority of policy areas where EU law intersects with devolved competence’.

Legislative frameworks could be more or less prescriptive and binding. Within the EU we noted above the important distinction between Regulations and Directives. We might see an analogous distinction emerging domestically, with some UK frameworks setting binding regulations that directly apply across the country, and others establishing common standards or principles that each nation can meet in its own way. This could be enabled through executive powers conferred on UK and devolved ministers in an Act of Parliament establishing the legislative framework. This would raise questions about accountability to the respective parliaments.

A further question is whether the creation of statutory frameworks will require changes to devolved legislative competence, for instance by adding ‘reservations’ of power in areas such as agriculture or state aid. One argument for this approach might be to provide greater legal certainty, since devolved institutions would then be unable to legislate contrary to the UK-wide framework. However, this approach would unarguably represent a recentralisation of power, and it would weaken the influence of devolved governments over the design and operation of frameworks in these areas. It seems unlikely that this approach would gain the consent of the devolved bodies, other than perhaps in non-contentious technical areas. Binding legal frameworks can in any case be created by the UK Parliament without any need to amend the devolution settlements, since Westminster retains the power to legislate on devolved matters, which it should do only with consent.

Non-legislative frameworks could come in different forms too. Some might contain agreed shared standards, some could facilitate data-sharing, and others might set out detailed arrangements for intergovernmental relations, including more robust dispute resolution mechanisms (for instance around fisheries, or to set out how devolved ministers will be consulted during trade negotiations that might impact on devolved policy areas).

New post-Brexit funding frameworks are also likely to be needed, for instance to replace spending from the EU Common Agricultural Policy and Structural Funds programmes. One option is to increase devolved block grants in line with the devolved nations’ current or forecast receipt of EU spending. The block grants would subsequently rise or fall each year in line with English spending, via the Barnett Formula. An alternative approach would be to create longer-term funding frameworks with ring-fenced budgets to support agriculture or regional economic development. The former approach would give the devolved institutions greater control of spending decisions, but would leave devolved budgets more exposed to the risk of cuts in England. The latter approach might provide greater budgetary certainty at the expense of decreased autonomy. In any case, new funding frameworks should be agreed by consent and subject to parliamentary scrutiny at all levels.

What new governance arrangements will be needed to make common frameworks work?

The 1999 devolution settlements were designed on the principle of a binary division of power between what was reserved and what was devolved. This model had advantages in terms of clear accountability, but it meant the UK did not have to develop a culture of or institutions for ‘shared rule' between central and devolved levels.i The UK membership of the EU further contributed to the weakness of intergovernmental working, since many policy issues with a cross-border component (including environmental protection, fisheries management, and market-distorting state aid) were addressed on an EU-wide basis.

Many studies and inquiriesii since 1999 have concluded that bodies such as the Joint Ministerial Committee system delivered few demonstrable benefits. Common criticisms included (a) that JMC bodies meet on an ad hoc basis, at the discretion of UK ministers, with no formal process for agreeing an agenda or meeting schedules (b) that it in practice offers little scope for devolved influence even when important devolved interests are at stake, and (c) that its proceedings are relatively opaque, with little information released to the public or parliaments. Past reviews of intergovernmental relations have also found evidence that Whitehall too often takes decisions without sufficient consideration of or consultation about their impact on the devolved nations and institutions.1

These weaknesses are all the more serious in the Brexit context. We have discussed above the patchy nature of intergovernmental engagement with regard to the UK negotiation strategy, leading to numerous proposals for reform in how the JMC(EN) operates. For instance, the Scottish and Welsh Governments made a joint call in June 2017:

to use JMC (EN) as a forum in which we can have meaningful discussions of key issues, aimed at reaching agreement rather than an opportunity to rehearse well-established public positions.

Scottish Government. (2017, June 15). Scottish and Welsh Governments write to Brexit Secretary David Davis. Retrieved from https://beta.gov.scot/news/scottish-and-welsh-governments-write-to-brexit-secretary-david-davis/ [accessed 25 January 2018]

The House of Lords European Union Committee similarly argued in July 2017 that

the UK Government needs to raise its game to make the JMC (EN) effective. This means better preparation, including bilateral discussions ahead of meetings, a structured work programme, greater transparency, and a willingness to accept that the JMC (EN), even if not a formal decision-making body, is more than a talking-shop… [and] should be authorised to agree common positions on key matters affecting devolved competences in time to inform the UK Government’s negotiating position.

UK Parliament. (2017, July 19). House of Lords European Union Committee 4th Report of Session 2017–19 Brexit: Devolution. Retrieved from https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201719/ldselect/ldeucom/9/9.pdf [accessed 25 January 2018]

As progress is made on agreeing new common UK frameworks, a debate is now beginning about the nature of intergovernmental structures that will be needed to provide for the oversight and renegotiation of these frameworks, and for appropriate dispute resolution processes. For instance, the Public Administration and Accounts Committee recently suggested:

evolving the JMC (P) into an annual Heads of Government Summit, analogous to meetings of the Council of the European Union… [which might] facilitate an extension of the length of time spent on JMC/Heads of Government business… and provide a greater guarantee that the interests of all four of the Governments are heard and better understood.

UK Parliament. (2016, December 8). House of Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee Sixth Report of Session 2016–17 The Future of the Union, part two: Inter-institutional relations in the UK. Retrieved from https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201617/cmselect/cmpubadm/839/839.pdf [accessed 25 January 2018]

There may also be a need for new JMC-type committees in areas where common frameworks are created, such as agriculture, the environment or fisheries. Additionally, as the Institute for Government has previously suggested,5 and as the Scottish Parliament’s Finance and Constitution Committee heard from Prof. Richard Rawlings, the post-Brexit UK may also require new JMC sub-committees ‘dealing with international trade policy and the domestic single market’.6

As noted, the ability to conclude trade agreements and the need to preserve the UK internal market are two of the six agreed reasons why common frameworks are deemed necessary.

There will therefore be a need for more systematic intergovernmental dialogue about these issues, for instance to ensure sufficient consideration of how trade agreements affect devolved areas. There might likewise be a case for new JMC type bodies in the spheres of justice, policing and security policy, if common frameworks are created in these areas.

In its 2017 White Paper on Brexit, Securing Wales’ Future, the Welsh Government, along with Plaid Cymru, has outlined the most detailed – and ambitious – proposals for future IGR of the four UK governments. It called for a replacement of the JMC structure with ‘a UK Council of Ministers covering the various aspects of policy for which agreement between all four UK administrations is required.’7

As part of this, the Welsh Government also called for ‘robust, and genuinely independent arbitration mechanisms to resolve any disputes over the compatibility of individual policy measures in one nation with the agreed frameworks’, to replace the existing JMC dispute resolution and avoidance protocol, which is rarely used and is not seen as robust enough by the devolved governments.7

It will also be important to create sufficient analytical and administrative support for these bodies. Consideration should be given to creating a proper joint secretariat for the JMC system, with resources to commission research and analysis that can inform joint decision-making between the UK and devolved governments about the operation and future evolution of common frameworks.

Whatever form new intergovernmental bodies take, as important as their structural design will be the principles they embody. We have noted the importance of common frameworks being designed jointly between the UK and devolved governments. Intergovernmental bodies created to oversee the operation of these frameworks should embody this idea of working in partnership, in contrast to the hierarchical logic of the current JMC system (reflected in the fact that JMC bodies meet only when and where UK ministers decide).

Comparative research has shown that when more decisions are taken through intergovernmental forums, as in some federal systems, accountability and parliamentary scrutiny can suffer.9 The creation of common frameworks signals a move away from a binary division of power towards more extensive joint working between UK and devolved governments. This therefore increases the importance of ensuring that intergovernmental bodies are transparent and accountable.

The opaque nature of existing UK IGR has been recognised by the Scottish Parliament and Government, who concluded an agreement in 2016 to improve the flow of information from executive to legislature about intergovernmental negotiations10. As a result of this agreement, no counterpart to which exists at Westminster, regular reports are now made by ministers to the Scottish Parliament, for instance before and after JMC meetings.iii This is an improvement on what went before, but it may be insufficient for ensuring the accountability of common frameworks.

Scrutiny of common frameworks might benefit from greater cooperation between the four UK legislatures. In July 2017, the House of Lords European Union Committee recommended ‘that the structures for interparliamentary dialogue and cooperation be strengthened’, to aid scrutiny of the Brexit process across the UK’s different legislatures.3 It has subsequently helped to establish an ‘Interparliamentary Forum on Brexit’, bringing together chairs of committees from the UK, Welsh, and Scottish legislatures ‘to discuss the process of the UK’s withdrawal from the European Union, and… [their] collective scrutiny of that process’.12This forum has met twice to date, in October 2017 and January 2018.

A more transformational proposal would be to place the intergovernmental system onto a statutory footing. The UK Government has always resisted this idea, preferring the flexibility and lack of legal obligations provided by the status quo. However, giving the JMC or similar structures a legislative basis might deliver a number of benefits, including increased transparency, an end to the current ad hoc approach to intergovernmental relations, and a stronger status for the devolved governments. The idea is not a new one but it might gain a new lease of life as a result of Brexit and the development of common frameworks. The House of Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee recently reported that: ‘There appears to be a consensus in the evidence we received of the desirability to place the UK’s inter-governmental machinery on a statutory footing.’13

If the idea of statutory intergovernmental relations is taken forward, careful thought would need to be given about precisely what aspects of this system to place into law. There would be risks in being too prescriptive about how particular intergovernmental bodies should operate. An alternative approach would be to set out in legislation some core principles for how intergovernmental relations will work in the context of common frameworks, for instance including commitments to transparency, to information sharing between the governments, to enforceable rights for devolved ministers to be involved in certain decision-making processes, and to a more robust dispute resolution system.

Annex: Areas of intersection between EU law and devolved legislative competence

| Lead UK department | Policy Area | Northern Ireland | Scotland | Wales |

| Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) | Carbon Capture & Storage | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Company Law | Yes | No | No | |

| Consumer law including protection and enforcement | Yes | No | No | |

| Efficiency in energy use | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Elements of Employment Law, including health and safety at work | Yes | No | No | |

| Environmental law concerning energy planning consents | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Environmental law concerning offshore oil and gas installations within territorial waters | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Heat metering and billing information | Yes | Yes | No | |

| High Efficiency Cogeneration | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Implementation of EU Emissions Trading System | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Late Payment Commercial Transactions | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Mutual recognition of professional qualifications | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Non-food product design and labelling | Yes | No | No | |

| Onshore hydrocarbons licensing | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Product Safety and Standards | Yes | No | No | |

| Radioactive Source Notifications - Transfrontier shipments | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Radioactive waste treatment and disposal | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Recognition of Insolvency Proceedings in EU Member States | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Renewable Energy Directive | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Security of supply (emergency stocks of oil) | Yes | No | No | |

| Security of supply (gas) | Yes | No | No | |

| Single energy market/Third Energy Package | Yes | No | No | |

| State Aid | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Cabinet Office (CO) | Public Sector Procurement | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Statistics | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Voting rights and candidacy rules for EU citizens in local government elections | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) | Energy Performance of Buildings Directive | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Directive | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Hazardous Substances Planning | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) Directive | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) | Elements of the Network and Information Security (NIS) Directive | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Provision in the 1995 Data Protection Directive (soon to be replaced by the General Data Protection Regulation) that allows for more than one supervisory authority in each member state. | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| The Rental and Lending Directive (concerning library lending) | Yes | No | No | |

| Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) | Agricultural Support | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Agriculture - Fertiliser Regulations | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Agriculture - GMO Marketing & Cultivation | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Agriculture - Organic Farming | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Agriculture - Zootech | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Animal Health and Traceability | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Animal Welfare | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Environmental quality - Air Quality | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Environmental quality - Biodiversity - access and benefit sharing of genetic resources (ABS) | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Environmental quality - Chemicals | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Environmental quality - Flood Risk Management | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Environmental quality - International timber trade (EUTR and FLEGT) | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Environmental quality - Marine environment | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Environmental quality - Natural Environment and Biodiversity | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Environmental quality - Ozone depleting substances and F-gases | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Environmental quality - Pesticides | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Environmental quality - Spatial Data Infrastructure Standards | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Environmental quality - Waste Packaging & Product Regulations | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Environmental quality - Waste Producer Responsibility Regulations | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Environmental quality - Water Quality | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Environmental quality - Water Resources | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Fisheries Management & Support | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Food Compositional Standards | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Food Geographical Indications (Protected Food Names) | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Food Labelling | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Forestry (domestic) | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Land use | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Plant Health, Seeds, and Propagating Material | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Department for Transport (DfT) | Aviation Noise Management at Airports | Yes | Yes | No |

| Driver Licensing Directive (roads). Also Driver certificates of Professional Competence | Yes | No | No | |

| Harbours | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Inland transport of dangerous goods and transportable pressure equipment | Yes | No | No | |

| Maritime Employment and Social Rights | Yes | No | No | |

| Operator licensing (roads) | Yes | No | No | |

| Passenger Rights (rail) | Yes | No | No | |

| Rail Franchising Rules | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Rail Markets and Operating Licensing | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Rail Markets: safety rules and régimes | Yes | No | No | |

| Rail Markets: technical standards | Yes | No | No | |

| Rail Markets: Train driving licenses and other certificates directive | Yes | No | No | |

| Rail Workers Rights Directive | Yes | No | No | |

| Roads - Motor Insurance (minimum required levels of insurance and various compensation schemes, not insurance, financial and prudential regulation, which is reserved) | Yes | No | No | |

| Roadworthiness Directive | Yes | No | No | |

| Transporting dangerous goods by rail, road and inland waterway Directive | Yes | No | No | |

| Vehicle registration (roads) | Yes | No | No | |

| Vehicle standards - various types approval Directives (roads) | Yes | No | No | |

| Working Time Rules and Harmonisation of Hours Directive and regulations on tachographs | Yes | No | No | |

| Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) | Blood Safety and Quality | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Clinical trials of medicinal products for human use | Yes | No | No | |

| Elements of Reciprocal Healthcare | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Elements of Tobacco Regulation | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Free movement of healthcare (the right of EEA citizens to have their elective procedure in another MS) | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Good laboratory practice | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Medical devices | Yes | No | No | |

| Medicinal products for human use | Yes | No | No | |

| Medicine Prices | Yes | No | No | |

| Nutrition health claims, composition and labelling | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Organs | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Public health (serious cross-border threats to health) | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Tissues and cells | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) | European Social Security Co-ordination | Yes | Yes | No |

| Migrant access to benefits | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Private cross border pensions | Yes | No | No | |

| Food Standards Agency (FSA) | Food and Feed Law | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Government Equalities Office (GEO) | Equal Treatment Legislation | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Home Office (HO) | Data sharing - (EU fingerprint database (EuroDac) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Data sharing - European Criminal Records Information System (ECRIS) | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Data sharing - False and Authentic Documents Online (FADO) | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Data sharing - passenger name records | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Data sharing - Prüm framework | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Data sharing - Schengen Information System (SIS II) | Yes | Yes | No | |

| EU agencies - EU-LISA | Yes | Yes | No | |

| EU agencies - Eurojust | Yes | Yes | No | |

| EU agencies - Europol | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Minimum standards legislation - child sexual exploitation | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Minimum standards legislation - cybercrime | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Minimum standards legislation - football disorder | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Minimum standards legislation - housing & care: regulation of the use of animals | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Minimum standards legislation - human trafficking | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Practical cooperation in law enforcement - Asset Recovery Offices | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Practical cooperation in law enforcement - Europan Judicial Network | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Practical cooperation in law enforcement - European Investigation Order | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Practical cooperation in law enforcement - Implementation of European Arrest Warrant | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Practical cooperation in law enforcement - Joint Action on Organised Crime | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Practical cooperation in law enforcement - Joint Investigation teams | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Practical cooperation in law enforcement - Mutual Legal Assistance | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Practical cooperation in law enforcement - Mutual Recognition of Asset Freezing Orders | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Practical cooperation in law enforcement - Mutual Recognition of Confiscation Orders | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Practical cooperation in law enforcement - Schengen Article 40 | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Practical cooperation in law enforcement - Swedish Initiative | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Health and Safety Executive (HSE) | Chemicals Regulation | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Civil use of explosives | Yes | No | No | |

| Control of Major Accident Hazards | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Genetically modified micro-organisms contained use | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Health and Safety at work | Yes | No | No | |

| Ionising Radiation | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Ministry of Justice (MOJ) | Civil judicial co-operation - jurisdiction and recognition & enforcement of judgements in civil & commerical matters (including B1 rules and related EU conventions) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Civil judicial co-operation - jurisdiction and recognition & enforcement of judgements instruments in family law (including BIIa, Maintenance and civil protection orders) | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Civil judicial co-operation on service of documents and taking of evidence | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Criminal offences minimum standards measures - Combating Child Sexual Exploitation Directive | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Cross-Border Mediation | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Legal aid in cross-border cases | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Mutual recognition of criminal court judgments measures & cross-border co-operation - European Protection Order, Prisoner Transfer Framework Directive, European Supervision Directive, Compensation to Crime Victims Directive | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Procedural Rights (Criminal Cases) - Minimum Standards Measures | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Provision of Legal Services | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Rules on Applicable Law in Civil and Commercial Cross-Border Claims | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Sentencing - Taking Convictions into account | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Uniform fast track procedures for certain civil and commercial claims (uncontested debts, small claims) | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Victims Rights Measures (Criminal Cases) | Yes | Yes | No |