Migrant labour in Scottish agriculture

This briefing examines the demand for seasonal workers in the Scottish agricultural and horticultural sector. It considers whether the recently announced UK pilot seasonal agricultural workers scheme will address the challenges faced by this industry. The briefing has been written for SPICe by Steven Thomson, a Senior Agricultural Economist at SRUC. The views expressed by the author are his own and do not represent the views of SPICe or of the Scottish Parliament.

Executive Summary

It is reported that Angus Growers had 85 tonnes of fruit unharvested or downgraded at a cost of £625,000 in 2017, at least in part due to a lack of seasonal workers.

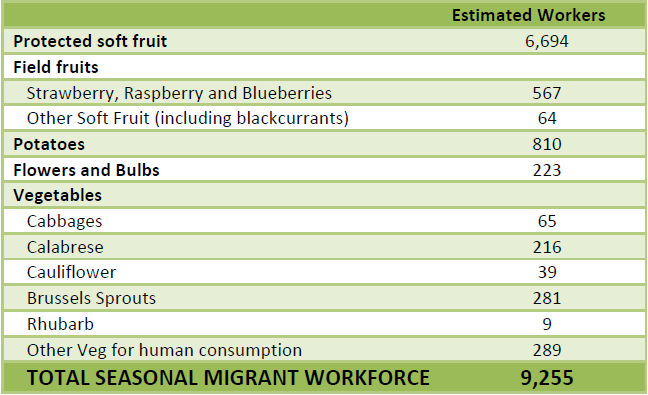

SRUC estimates that there were 9,257 seasonal migrant workers engaged in Scottish agriculture in 2017. A significant majority were engaged in the East Coast soft fruit sector during the summer months.

The Scottish horticulture (including the soft fruit sector) and potato sector accounts for 16.6% of Scottish agricultural output by value, despite using less than 1% of Scottish farmland. The use of a large scale seasonal migrant workforce is concentrated on a small number of very intensive horticulture units.

Foreign workers choose to work on Scottish farms because of: earning potential linked to enhanced quality of life and goals; conditions of work relative to home countries; and familiarity, recommendations and farm reputations.

The agricultural industry has demanded workers from outside the EU be let into the UK, amidst estimates of 10% to 20% worker shortages.

On 6 September 2018, Home Secretary, Sajid Javid, announced a pilot scheme to bring migrant workers from outside the EU to UK farms. The pilot scheme will allow farmers to bring workers to the UK for up to six months.

Scottish businesses alone could use the lion’s share of the pilot quota.

The scheme is unclear on a number of issues, including: how the scheme will ensure the finite quota of workers are effectively placed across all sectors and places that experience recruitment difficulties; and how workforce mobility will be accounted for.

Agriculture production cycles are not easily turned on and off. As one of the respondents to SRUC’s survey explained -“No seasonal labour ...no business! It’s that simple”.

The briefing is written by Steven Thomson from SRUC, drawing on the recent Farm Workers in Scottish Agriculture: Case Studies in the International Seasonal Migrant Labour Market study1, funded by the Scottish Government. The views expressed by the author are his own and do not represent the views of SPICe or of the Scottish Parliament.

Background

Agricultural production cycles are not easily turned on and off, and if agricultural and horticultural crops are to be planted in the coming years, farmers need to know that they will be able to harvest their crops and maintain a viable business.

It is reported that Angus Growers had 85 tonnes of fruit unharvested or downgraded at a cost of £625,000 in 2017, at least in part due to a lack of seasonal workers (Courier).

The Association of Labour Providers1 stated that -

a current and anticipated inability to access sufficient labour is leading growers to take decisions not to plant, to plant less labour intensive produce, or to plant overseas. It leads manufacturers to delay investment and growth decisions, incur additional costs, to invest in overseas manufacturing, to failures in supply and ultimately to business jeopardy and closure.

This briefing examines some of the issues surrounding the employment of seasonal agricultural and horticultural workers in Scotland. It examines what role the pilot seasonal agricultural workers scheme, recently announced by the UK Government, will play in addressing the challenges faced.

The Scottish horticultural sector

The use of a large scale seasonal migrant workforce is concentrated on a small number of very intensive horticulture units. As shown in the table below, the relevant sectors include soft fruit, potatoes, flowers and bulbs and vegetables. Nineteen of the businesses responding to the SRUC survey of the sector accounted for 90% of the workforce and workdays of all survey respondents (SRUC, 2018). The table below shows which sectors used the seasonal migrant workforce in Scotland in 2017.

SRUC, 2018

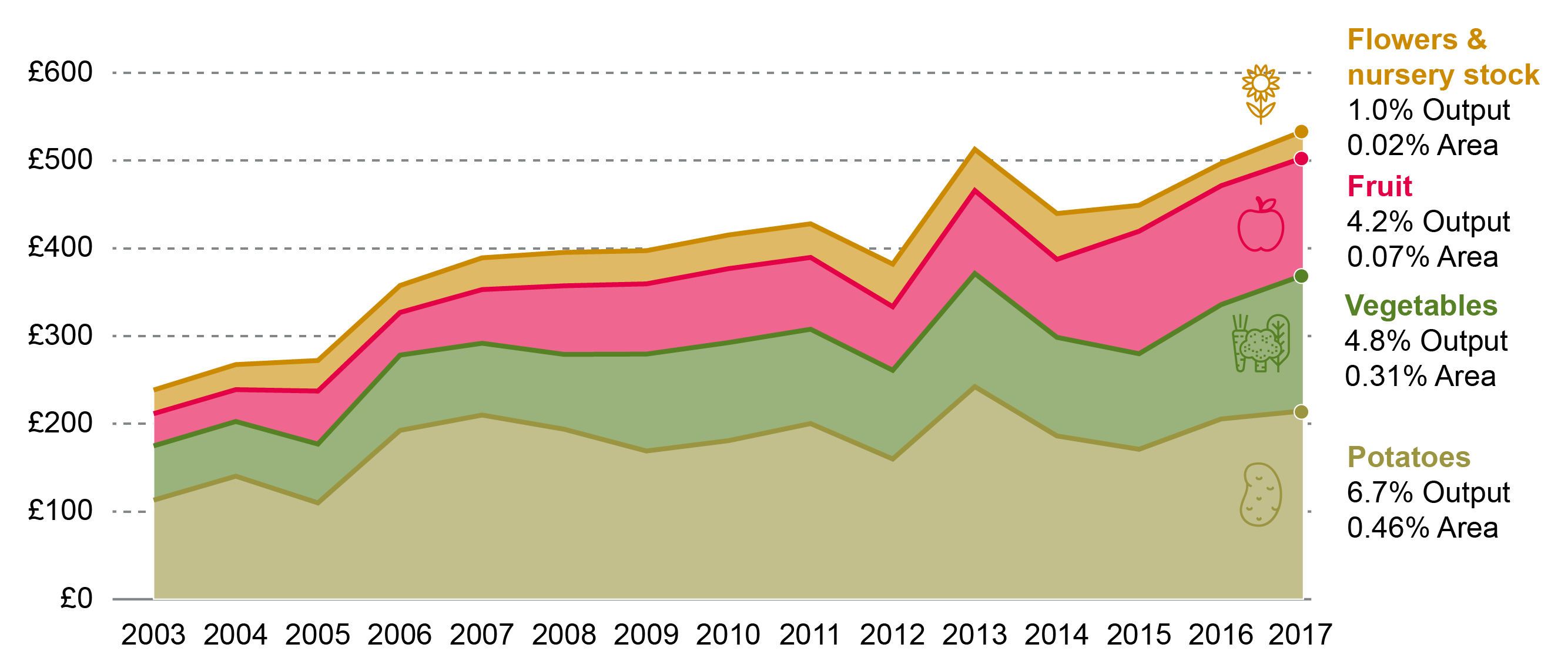

The Scottish horticulture and potato sector accounts for a sixth (16.6%) of Scottish agricultural output by value, despite using less than 1% of Scottish farmland. Scotland’s soft fruit and vegetable sectors have grown significantly in the last 10 to 15 years, with soft fruit output more than tripling since 2003, and vegetable output more than doubling.

Why are foreign workers needed in Scotland?

In Scotland the horticulture and potato sectors are reliant on seasonal labour to undertake key planting, harvesting, grading and processing tasks on farms – tasks with no real mechanical alternative.

Historically, a lot of the work was undertaken by local people or students looking for working holidays and an opportunity to generate some money. However, with the advent of minimum wages in the late 1990s the farm work necessarily became more professional, with workers having to meet minimal standards and throughput compared to the old piece-rate system where they simply got paid for what they harvested/planted. This, and cultural changes where local people no longer appear to want this type of work, meant that the farmers increasingly had to look overseas to fill the workforce void.

A respondent to SRUC's survey said -

We are happy to use locally sourced UK labour, unfortunately none is available for this type of seasonal outdoor work (in all weather). Therefore we have used seasonal migrant workers since 2002. Prior to this all seasonal labour was local. Since then our requirements have more than doubled but local seasonal labour has all but disappeared.

Challenges in recruiting seasonal agricultural workers

The last two years have seen some farmers having to leave a proportion of their crops unharvested due to a shortage of seasonal workers.

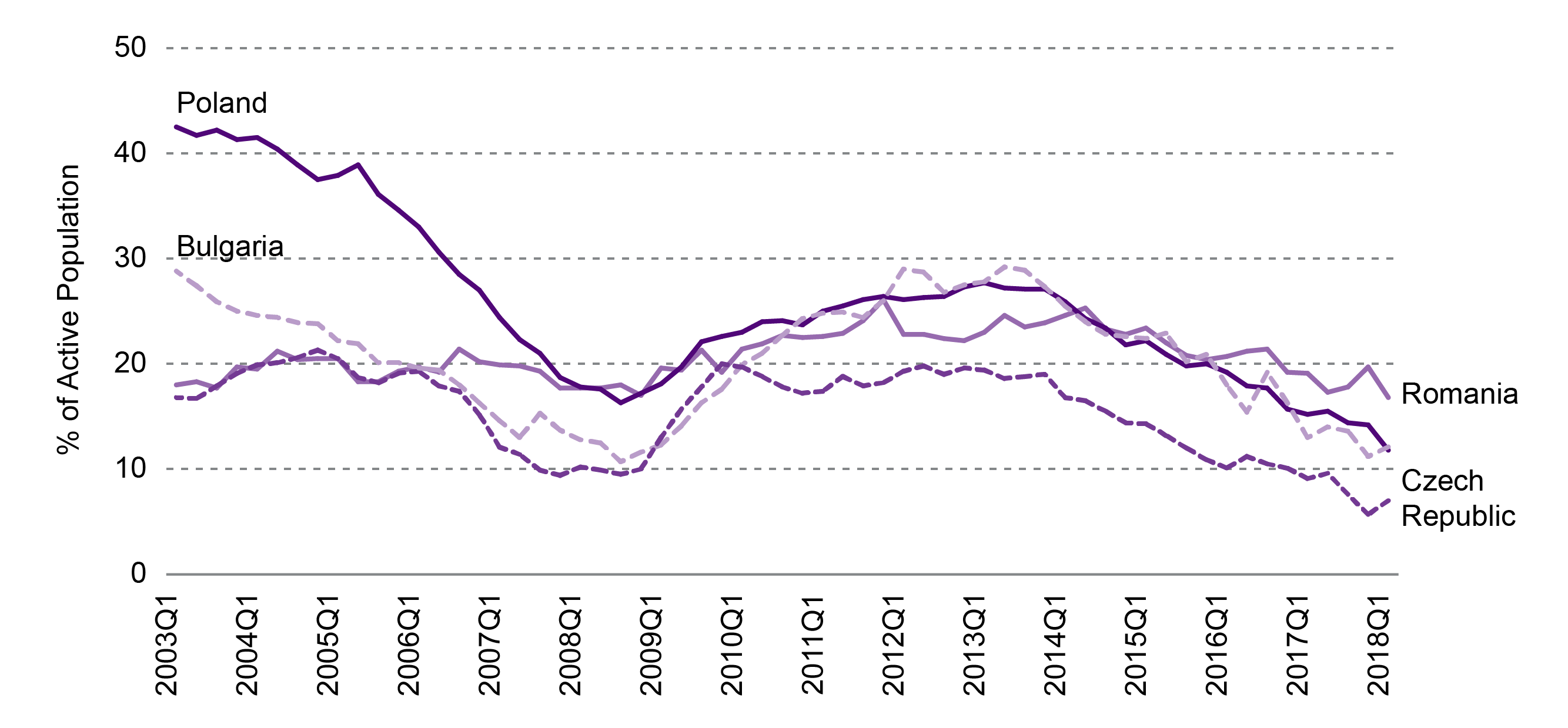

One of the factors affecting current recruitment challenges is the improved performance of many Eastern European economies in recent times, which has led to falling unemployment rates (less than 5% unemployment in both Romania and Bulgaria in July 2018) including, importantly, youth unemployment levels.

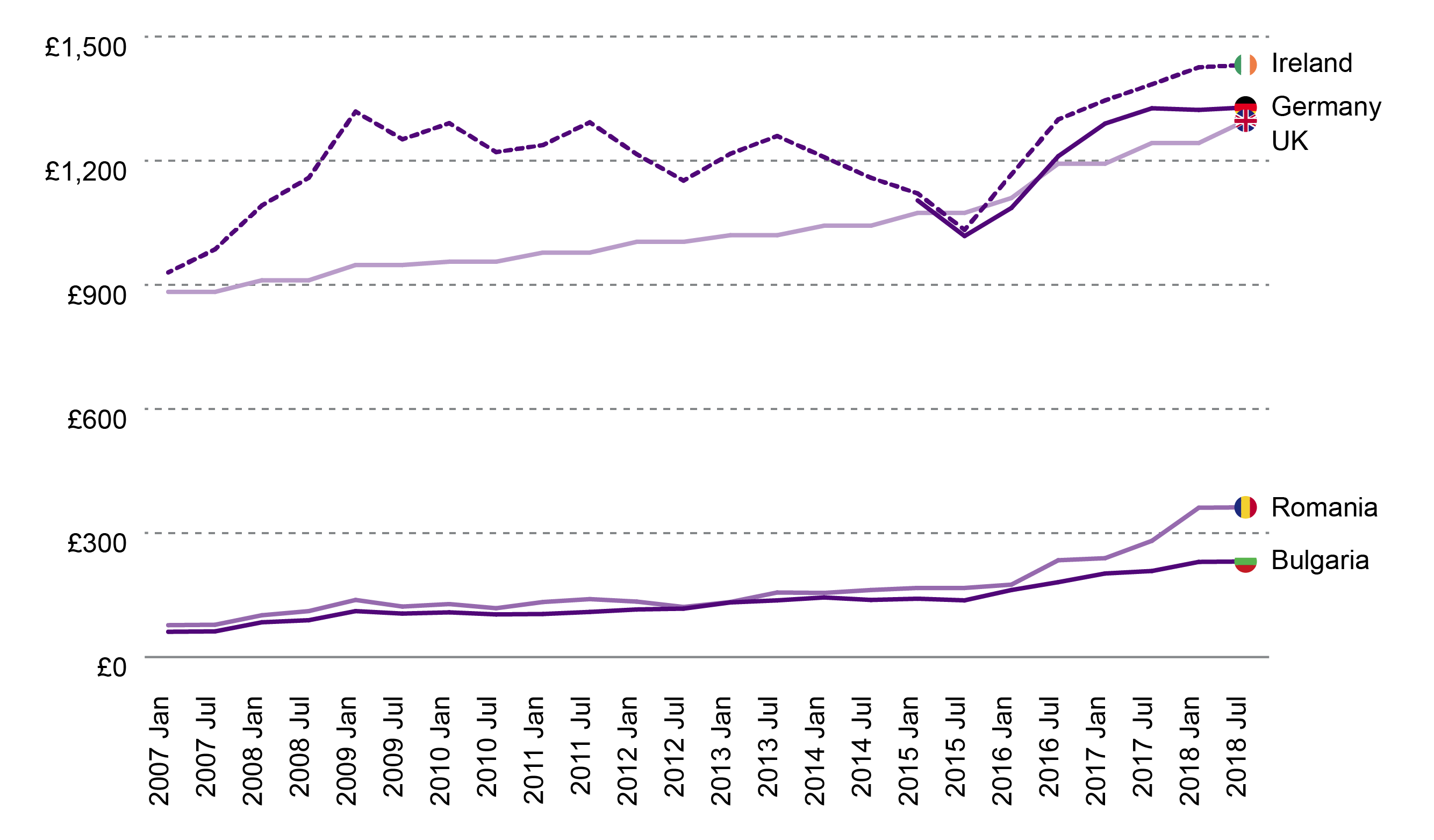

Improvements in Eastern European economic performance has led to a general shortage of seasonal farm workers across much of Europe at the moment (e.g. Germany, Ireland, Spain, etc.). However, the situation in Scotland, and the rest of the UK, has been exacerbated by the weaknesses of Sterling since the Brexit vote. This means that the effective take home wage for Eastern Europeans working in the UK has fallen since 2015.

For example, Romanians working in Scotland are effectively taking home 21% less money compared to November 2015, solely due to exchange rates – whilst those Romanians working in Euro countries have benefited by a 4% exchange rate uplift in their take home wages.

It is therefore unsurprising that recruitment challenges exist across the UK’s horticulture sector, and that the industry has demanded workers from outside the EU be allowed into the UK, amidst estimates of 10% to 20% worker shortages (NFUS, 2018).

Worker motivations

The seasonal EU workforce is considered to be “motivated, reliable, hard-working and honest” (SRUC, 2018). The prevalence of workers from different countries reflects the economic performance of workers’ home countries relative to Scotland. SRUC's research highlighted that the key motivations for foreign workers choosing to work on Scottish farms were -

earnings potential linked to enhanced quality of life and goals

conditions of work relative to home countries, and

familiarity, recommendations and farm reputations.

Significant growth in statutory minimum wages in Bulgaria and Romania has occurred in the last decade, but wage motives for leaving these countries for work remain strong.

For example, a Bulgarian worker on minimum wages would be able to earn £1,000 more per month in Scotland compared to back home. This wage differential is before additional earnings from extended working hours and overtime on farms is taken into account. Workers will have additional accommodation and living costs in Scotland, but the attraction is plain to see.

Seasonality

The seasonal pattern of fruit, vegetable and potato crops in Scotland provides an opportunity for extended work periods for a proportion of migrant workers. The SRUC study found that some “seasonal” workers are wholly employed within the UK over a year with many working the entire period in a single business. However, some longer-term seasonal workers are employed by multiple businesses in various locations, including beyond farm businesses - for example food processors, construction and hospitality businesses, and agricultural labour providers.

A proportion of the migrant workforce is highly mobile, moving between farms and regions in line with peak harvest seasons. Whilst the soft fruit sector is highly seasonal, the length of the growing season continues to expand, driven by technological and plant breeding advances, the use of polytunnels and diversification of the types of fruit grown. SRUC found that, on average, workers were employed for just over four months per year. But in a given season -

36% of the workforce worked for less than 2 months;

38% for between 3 and 5 months;

26% more than 6 months.

Returnees the bedrock of recruitment

The best workers develop skills over multiple seasons and this means that Scottish farmers seek to retain good seasonal employees year after year. Indeed, returnees are regularly relied on to provide an experienced core of employees to spread across worker teams meaning they often become keystone workers – helping manage and run the farm businesses.

A respondent to SRUC's survey said -

Every few years we get one that finds a substantial role for themselves and stays on…we have eight supervisors that have come that route and most now live here all year.

SRUC's study estimated that around half of Scotland’s seasonal migrant agricultural workforce were returnees in 2017, with the remainder being sourced through -

recruitment agencies (18%);

informal ‘friends and family’ networks of existing staff (13%);

direct recruitment by the farms (10%).

In addition, during peak work periods labour providers (sometimes referred to as “gangmasters”) are often contracted to supply workers on a more flexible and immediate basis, something more commonplace in the field vegetable and potato sector compared to the fruit sector.

The old seasonal agricultural worker scheme

Until 2013 the UK had a Seasonal Agricultural Worker Scheme (SAWS). Introduced post Second World War, the SAWS went through many iterations. In the early 2000s it was open to workers from non-EU countries to work for up-to six months in the UK - with Ukraine, Russia and Belarus and Bulgaria taking a significant proportion of the approximate 20,000 annual SAWS permits.

With the accession of Bulgaria and Romania to the EU in 2007, the SAWS was restricted to workers from these countries from 2008 and the scheme was eventually scrapped in 2013 as post-accession worker restrictions on Bulgarian and Romanians came to an end. Commenting on the end of the SAWS scheme the UK Government stated1 -

Unskilled and low skilled labour needs should be satisfied from within the expanded EEA labour market…We do not think that the characteristics of the horticultural sector, such as its seasonality and dependence on readily available workers to be deployed at short notice, are so different from those in other employment sectors as to merit special treatment from a migration policy perspective.

Bulgarian and Romanian workers remain fundamental to the sector, accounting for an estimated 60% of Scotland’s seasonal migrant workforce in 2017. A further 18% come from Poland.

What are others countries doing?

In recent months with unprecedented shortages of labour for important EU agri-food sectors, a number of EU countries have introduced seasonal work permit schemes for non-EU agri-food workers -

Poland has a bilateral agreement for Ukrainians to work there with many engaged in the agriculture sector;

Whilst Ukrainian students are only currently permitted to work in Germany, in 2017 around 6,000 took the opportunity to work for up-to 90 days on farms. Germany is looking to develop arrangements with Balkan countries and Ukraine to overcome farm worker shortages;

In December 2017 Spain made an agreement with Morocco for an additional 7,000 seasonal female farm workers to be able to work for an average of 3 months (at €40 per day) picking strawberries (women are preferred as they are considered more likely to return home – particularly those with children1). Spain and Morocco have had a bilateral agreement on workers since 2001 and it is estimated that there are some 72,000 Moroccans working on Spanish farms alongside around 130,000 other migrant workers;

In May 2018 the Republic of Ireland announced a pilot scheme with 800 permits simplifying agri-food business recruitment from the non-European Economic Area, with a minimum income threshold of €22,000.

The new pilot seasonal agricultural workers scheme

On 6 September 2018, Home Secretary, Sajid Javid, announced a pilot scheme to bring migrant workers from outside the EU to UK farms. The pilot SAWS will allow farmers to bring workers to the UK for up to 6 months. The Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, Michael Gove commented that -

This two year pilot will ease the workforce pressures faced by farmers during busy times of the year. We will review the pilot’s results as we look at how best to support the longer-term needs of industry outside the EU.

Defra has provided the following details -

Pilot workers must be at least 18 years old on the date of application and be from outside of the European Union

Scheme operators will be licenced by the Gangmasters and Labour Abuse Authority (GLAA) and will have to ensure farms where labour is placed adhere to relevant legislation, including the National Minimum Wage

The scheme will be run by “two scheme operators” who will oversee the placement of the workers

The pilot will run from spring 2019 until the end of December 2020 and will be monitored by the Home Office and Defra.

Defra and the Home Office are keen that longer term agri-tech solutions be developed1.

Will the scheme meet the needs of Scottish agriculture?

In light of the background set out above, some issues remain over the pilot scheme.

What happens under a no-deal Brexit? The potential for a “no deal” with the EU could have implications for the agricultural sector’s access to the existing pool of seasonal migrant workers. Both the EU and the UK Government’s plans are for a continuation of EU seasonal worker rights during the proposed transition period to the end of 2020. However, there is no clarity on access rights in the event of no deal or beyond the transition period.

The Migration Advisory Committee’s Final Report on EEA Workers in the UK Labour Market (18 September 20181) acknowledges that

If there is no such [SAWS] scheme it is likely that there would be a contraction and even closure of many businesses in parts of agriculture in the short-run, as they are currently very dependent on this labour.

This acknowledges the need for a scheme – but fails to acknowledge that a drying-up of seasonal EU workers may significantly outweigh the mitigation that a pilot SAWS can deliver.

Can 2,500 non-EU workers fill the recruitment gaps? With estimates of 70,000 to 80,000 migrant workers engaged in UK agriculture2 and a shortfall of 10%-20% in 2018 it is hard to see how 2,500 additional workers will alleviate the ongoing recruitment problem. Indeed, in Scotland the 15% to 20% shortfall experienced in 2017/2018 means that Scottish businesses alone could use the lion’s share of the pilot quota. SRUC argue that across the UK, between 15,000-20,000 non-EU workers may be needed in 2019 and 2020 – particularly if current trends of fewer EU workers choosing to work in the UK continue.

Will the pilot scheme have quota flexibility? Given uncertainties over migration policy (especially with the EU) and exchange rates post-Brexit, it is unclear whether there will be flexibility to rapidly increase the visa quota in response to industry need. Even if this is possible there will likely be significant delays between identifying worker shortages, the policy response, and the recruitment and placement of workers. This could have significant impacts on businesses.

Will there be equitable geographical or sectoral allocation of workers? It is unclear how the scheme will ensure the finite quota of workers are effectively placed across all sectors and places that experience recruitment difficulties. How businesses are prioritised for worker allocation, given the relatively small quota number, is likely to be contentious.

How will workforce mobility be accounted for? A proportion of the workforce are highly mobile. For example, specialist flower pickers move from the South West of England up to the North East of Scotland as the daffodil season progresses. Equally many workers will move between farms for a variety of reasons such as relative ripe fruit abundance, pay rates, presence of friends and family etc. Given that some businesses may only need scheme workers for a short period (e.g. three months during peak harvest periods) it is unclear whether the scheme will have the flexibility to allow these workers to be relocated on another farm, provided their total length of stay is less than six months.

Will permits be reallocated if workers fail to stay the full six months? A proportion of the scheme workforce may not stay in the UK for the full six months. In such instances, it could lead to the scheme underperforming in terms of business needs and expectations.

For example, if the 2,500 workers work six days per week, the scheme would provide 360,000 work days if everyone stayed for six months. However, if the average length of stay is only four months then the number of workdays provided by the scheme would fall by a third.

Will workers be permitted to return on an annual basis? Returnees are the bedrock of many soft fruit businesses and a proportion of the existing workforce work on farms for much longer than six months (with some staying up to 10 months per year). It is unclear how the pilot scheme could support farms that need continuity of workers over a prolonged period. Further, if the scheme prefers new candidates each season (as the previous SAWS did) the added value of retaining staff across seasons will be lost. This would mean greater costs and lost productivity to both the business and the individual worker through the need for new workers to undergo training, familiarisation.

Who will be responsible for ensuring scheme workers return home? The UK Government have stated that there will be two scheme operators. It is unclear if they will have responsibility for ensuring workers leave the UK after their work placement comes to an end.

Will the scheme provide workers from 1st April 2019? Given the extended growing season and existing recruitment challenges the scheme operators will need to be active soon in order to fill vacancies from April. They will have to advertise, locate and vet applications in the months leading up to the April launch date so that in the immediate post-Brexit period there is a stock of workers that the industry can draw on.

Implications of no seasonal labour

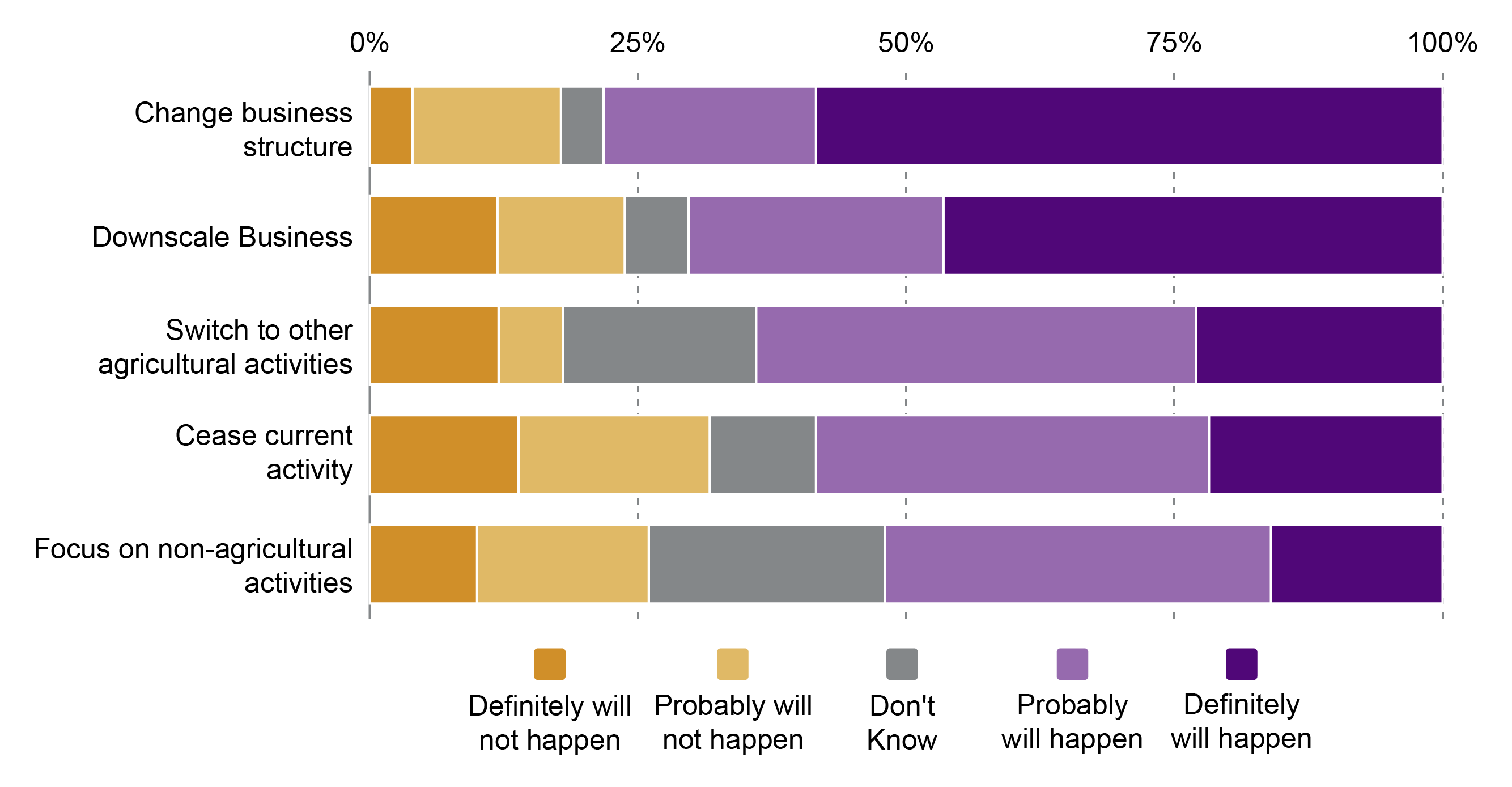

SRUC asked fruit and vegetable farm business in Scotland what they would do without access to foreign seasonal farm workers. The figure below represents responses from 51 businesses that directly employed seasonal migrants and they represented about two-thirds of the total seasonal migrant workforce in Scotland

Agriculture production cycles are not easily turned on and off. If horticultural crops are to be planted, farmers need to know they will be able to harvest them. The UK pilot scheme may be a crucial factor in farmers decision making in Scotland. As one of the respondents to SRUC’s survey explained -

“No seasonal labour ...no business! It’s that simple”.