Local Government and Communities Committee

Stage 1 Report on the Fuel Poverty (Target, Definition and Strategy) (Scotland) Bill

Conclusions and Recommendations

Section 1 - Fuel Poverty Target

The Target

The Committee supports the principle of setting a statutory target for reducing fuel poverty within a set time period.

Eradication versus a 5% target

The Committee accepts that setting a statutory target for reducing fuel poverty is ultimately a matter of judgment. We are satisfied, on the basis of evidence led, that the target of 5% set out in the Bill is achievable and at the same time would make a real difference to the lives of hundreds of thousands of people were it to be achieved. On balance, it appears to us to strike an appropriate balance between realism and ambition. The 5% target also recognises the Scottish Government's limited influence in relation to two of the four main drivers of fuel poverty, and its transient nature, with the potential for individual households to move in and out of the definition, depending on changing circumstances in relation to which governments may have little or no direct control.

The Committee agrees with the Scottish Government that the more long-term ambition should be the eradication of fuel poverty, as much as is realistically possible, and that the 5% target should not be the limit of this or future government's ambitions. With robust monitoring systems in place (as discussed later in the report), there is the opportunity to learn from experience and to benefit from technological advances between now and the target date.

The length of the target

The Committee notes concerns regarding the length of the target date set out in the Bill, which at 21 years is considerably longer than the 14-year target previous Scottish administrations had worked to. However, the Committee also understands views that this approach is a pragmatic response to previous attempts to set a target, which ultimately failed. We also recognise arguments that reducing fuel poverty will lean heavily on applying technologies still in development and that it is realistic to build in time for these to come on-stream.

The Committee therefore accepts the Government's reasons for setting the target date at 2040. This would however be conditional on the Government bringing forward amendments to make at least some of its interim milestones statutory by way of amendment at Stage 2, and we are pleased to note that a public commitment has been made to enshrine two of these at Stage 2. If the amendments are agreed to, this should help protect the fuel poverty strategy from "drift", and enable comprehensive assessment of how well the strategy is working at its mid-point.

Extreme Fuel Poverty

The Committee notes concerns from stakeholders working with those in extreme fuel poverty (i.e. those having to spend more than 20% of their income on fuel) about the lack of explicit reference in the Bill to prioritising a reduction in extreme fuel poverty. We heard that, without such a reference, there is a risk, even if the overall target is ultimately met, of efforts being targeted at "low hanging fruit". This could leave a disproportionate number of those with the most critical needs remaining in the final 5 per cent facing fuel poverty by 2040.

We ask the Government to bring forward proposals for a separate target for targeting extreme fuel poverty at Stage 2, and to ensure that there is specific reference to eradicating it in any strategy produced under the Bill.

Local Targeting

Given that island areas receive more spend per head on energy efficiency measures than mainland communities, it is concerning that inordinate numbers of householders on our island communities still experience fuel poverty. We believe that the Scottish Government should consider amending Section 1 of the Bill to put in place statutory targets for each local authority to reduce fuel poverty in their areas to no greater than 5 per cent of their households by 2040, in order to help drive progress towards achievement of the national target and eliminate regional disparities.

The Committee understands concerns that there may be a tendency for local authorities to direct resources at the most easy to treat properties in order to meet the new statutory target. We welcome the Minister’s commitment to continue to work with local authorities to consider how best to distribute schemes to balance the requirements of those with the greatest needs for support and those with more marginal problems. We, however, urge the Government to ensure that the fuel poverty strategy will provide clear, helpful and practical guidance to local authorities on how best to distribute their resources to avoid local disparities.

We also heard of the innovative local schemes already in place which allow services to be creative around how they distribute their resources to reduce such anomalies and seek further information on how the Government will ensure the sharing of best practice between local authorities. This applies particularly to island communities which often struggle to achieve the economies of scale that can be achieved on the mainland.

Section 2 - Definition of Fuel Poverty

MIS and rural uplift

The Committee welcomes the revised definition of fuel poverty set out in the Bill, based around the calculation of a Minimum Income Standard that takes account of daily living costs. This should help ensure a closer linkage to actual "lived" income poverty.

However, we understand stakeholders' concerns that the definition may not adequately take into account the reality of living in islands, remote towns and remote rural areas, including the much higher living and travel costs in those areas, reflected in current high levels of fuel poverty.

We therefore ask the Scottish Government, during the remaining passage of the Bill, to commit to introducing an additional Minimum Income Standard to reflect the higher costs faced by those living in islands, remote towns and remote rural areas. In doing so we would urge the Scottish Government to ensure that the additional MIS captures all households in areas covered by categories 4 and 6 of the Urban Rural Classification.

No MIS mark-up for disability or long-term illness and the extension of the age vulnerability criteria

As people are, in general, living longer and healthier lives, the Committee agrees that reaching 60 should not, as a matter of course, be regarded as an indicator of vulnerability and thus of a need for "enhanced heating" under the Bill. We are generally content with the age threshold being 75. In this connection, the Committee notes that the Scottish Government intends to include individuals with long-term health problems amongst those in need of enhanced heating and that this is likely to capture a significant number of households which include an individual in the 60-75 age cohort.

However, the Committee does note concerns about how the approach set out in the Bill might impact in areas of multiple deprivation where life expectancy is on average lower. We ask the Scottish Government to respond to evidence that there should be some built-in flexibility when setting vulnerability criteria by age, so as not to exclude households in real need of enhanced heating status.

Complexity of the new target and linkage to delivery on the ground

The Committee notes that the fuel poverty definition in the Bill is a statistical measuring tool to assess the national fuel poverty rate. As noted earlier, we broadly welcome the definition as a more effective measure of "real life" fuel poverty than the current definition.

Measures on the ground are of course what matter most to people currently in fuel poverty and those trying to help bring them out of it. Stakeholders have significant concerns that the complexity of the definition could obstruct help going to some of those in need and prevent some from self-identifying as living in fuel poverty. A "door-step tool" to help determine which households are in fuel poverty could assist and we would welcome an update on the Scottish Government's thinking on the feasibility of such a tool should the Bill progress. We also invite the Scottish Government to respond to the evidence led at Stage 1 proposing better sharing of information that is relevant in determining whether households are in fuel poverty.

Stakeholders also had concerns as to how the new definition could be made to work alongside the proxies that are used in practice to determine whether households are in need of assistance. We would therefore welcome an update on when the review of the current proxies will take place, how the Government intends to roll out guidance, and how it will encourage the sharing of best practice.

Sections 3-5 - Fuel Poverty Strategy

The Committee believes that an effective fuel poverty strategy will be crucial if current and future administrations are to be successful in their ambitious long-term aim of eradicating fuel poverty in Scotland. It is therefore welcome that the Bill requires the Scottish Government to publish a fuel poverty strategy.

It is vital that key measures and policies are informed by the views of those with first-hand knowledge of the effects and impact of fuel poverty. The Committee welcomes the requirement in the Bill for consultation with people who are living, or who have lived, in fuel poverty before any strategy is published.

Any successful strategy cannot be "top down" if it is to successfully identify the measures best placed to help people. The Committee considers that when periodically reporting to Parliament on progress under the strategy, the Scottish Ministers show whether and how policies and procedures to tackle fuel poverty have taken the lived experience of individuals into account.

The content of the draft strategy

Lack of policies reflecting the rural dimension

The Committee welcomes the Minister's commitment to undertake an Islands Impact Assessment on all aspects of the Bill and considers that any such assessment should also cover the Draft Fuel Poverty Strategy. The Committee would welcome this happening as soon as possible, to allow the Committee to take a view on any of the issues raised in advance of its consideration of amendments to the Bill.

Monitoring of delivery schemes

The Committee was concerned to hear about the inadequacy of works carried out under UK-based energy-efficiency schemes and the apparent lack of monitoring of the quality of this work. We were also concerned with reports that there had been insufficient support from the UK Government to provide re-dress for those who have received defective repairs. The Committee intends to write to the UK Government to call for it to take action and urges the Scottish Government to continue to highlight this issue to the UK Government.

General

The Committee welcomes the publication of the draft fuel poverty strategy and recognises that it is a "work in progress". We note that the Government will work with stakeholders and those with experience of fuel poverty to drive forward improvements. We urge the Scottish Government to take account of the views presented by those who gave evidence in this section of the report, particularly on-

how the strategy will take action to address the drivers of fuel poverty in addition to energy efficiency;

how lessons will be learned from previous schemes;

how best practice will be mainstreamed across Scotland;

linkages to other policies and proposed laws, such as the Planning (Scotland) Bill and the Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Bill;

resourcing and the impact on other policy areas such as the economy, health, social care and educational attainment;

how it will improve policies to tackle fuel poverty in remote rural and island areas;

how it will tackle fuel poverty in the private rented sector;

how it will monitor quality and value for money of energy efficiency measures and delivery schemes; and

the support provided to households that have received ineffective repairs.

Section 6-9 – Reporting on Fuel Poverty

The Committee welcomes the Minister’s commitment to include reporting on progress against all four drivers of fuel poverty and the impact of measures to address each driver. In addition to providing an overall picture of progress against milestones and targets, it will also provide an overview of those mechanisms which are producing positive results and those which are to be mainstreamed as part of best practice, but also those where extra resource needs to be targeted. This is particularly important given that the Scottish Government does not have full control over each of the drivers.

The Committee understands the Minister’s comments that the 5 year reporting requirements in the Bill align well with those in the Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Target) (Scotland) Bill. However, the Fuel Poverty (Target, Definition and Strategy) (Scotland) Bill is a significant piece of legislation in itself, and the Committee also understands views that 5 years is too long a period for statutory reporting on such an important matter. We therefore agree with those who provided evidence that a 3 year reporting period would be preferable. This would better enable quick and effective action to be taken should critical milestones not be achieved.

We recognise the benefit of robust and independent scrutiny that the Committee on Climate Change has brought to measuring progress against climate change targets. The Committee recommends that an independent scrutiny body be put in place to provide the same function for fuel poverty targets. We suggest that the current Scottish Fuel Poverty Advisory Panel could be put on a statutory footing to carry out this role.

Sections 10-14 – General

The Committee agrees that all provisions of the Bill should come into force within 12 months from the date of royal assent.

Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee consideration

The Committee is grateful to the the Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee for raising questions over the delegated powers set out in the Bill, in relation to the appointment of a person to determine the Minimum Income Standard and a power to redefine "fuel poverty". Following evidence from the Minister, we are satisfied that these powers are appropriate.

Policy and Financial Memorandum

The Committee considers that the level of detail provided in the Policy Memorandum on the policy intention behind the provisions in the Bill assisted the Committee in its scrutiny of the Bill.

It is difficult to comment on the financial implications of the Bill, given that the true costs are associated with measures, policies and procedures to be set out in the strategy. At Stage 1, the Committee heard differing views from the Scottish Government and some stakeholders as to whether achieving the target in the Bill would or would not require a step change in resourcing.

It is also surprising that the Government has provided estimated costings for meeting climate change targets in the Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Bill, yet chose not to take a similar approach for this Bill.

We therefore urge the Scottish Government to consider providing further information on the potential costings and funding sources for achieving the fuel poverty targets to the Commitee and to Parliament as the Bill progresses.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Under Rule 9.6.1 of Standing Orders, the lead committee is required to report to the Parliament on the general principles of the Bill.

The Committee has made a number of requests for further information from the Scottish Government and recommendations on issues related to certain aspects of the Bill. That said the Committee overall welcomes the Bill and its core commitment of setting a target which, if achieved, would make a real difference to the lives of thousands of Scottish families.

The Committee therefore recommends that the Parliament agrees the general principles of the Bill.

Introduction

The Fuel Poverty (Target, Definition and Strategy) (Scotland) Bill was introduced by the Scottish Government on 26 June 2018. The Local Government and Communities Committee was appointed lead Committee to scrutinise the Bill at Stage 1 on 5 September 2018.

The long title of the Bill sets out its purpose-

An Act of the Scottish Parliament to set a target relating to the eradication of fuel poverty; to define fuel poverty; to require the production of a fuel poverty strategy; and to make provision about reporting on fuel poverty.1

The Policy Memorandum states that the ambition for Scotland is to see more households:

living in well-insulated homes;

accessing affordable, low carbon energy; and

having an increased understanding of how to best use energy efficiently in their homes.2

This report sets out the Committee's conclusions and recommendations on its Stage 1 scrutiny of the Bill. At Stage 1 of a Bill, the lead Committee takes evidence and gathers views on the general principles of the Bill, before reporting to Parliament with a view on whether the general principles should be approved, and the Bill proceed to Stage 2.

Background

The issue

Fuel poverty is an issue which affects a large number of people in Scotland, with some people and families struggling to pay for their fuel bills or heat their home to an acceptable and comfortable level. During our scrutiny, the Committee heard reports of people having to make a choice about whether to eat or to heat their home, even though we live in an energy-rich country abundant in renewable energy sources and with oil, gas and coal reserves.

Living in a cold draughty home can have a negative impact on people's physical health and mental wellbeing and impact on children's attainment.1 2

Despite efforts by previous administrations to tackle the issue of fuel poverty, it is disappointing that it remains a significant problem in this country. The most recent Scottish House Condition Survey (SHCS) figures show that in 2017, 24.9% of households (613,000) were in fuel poverty.

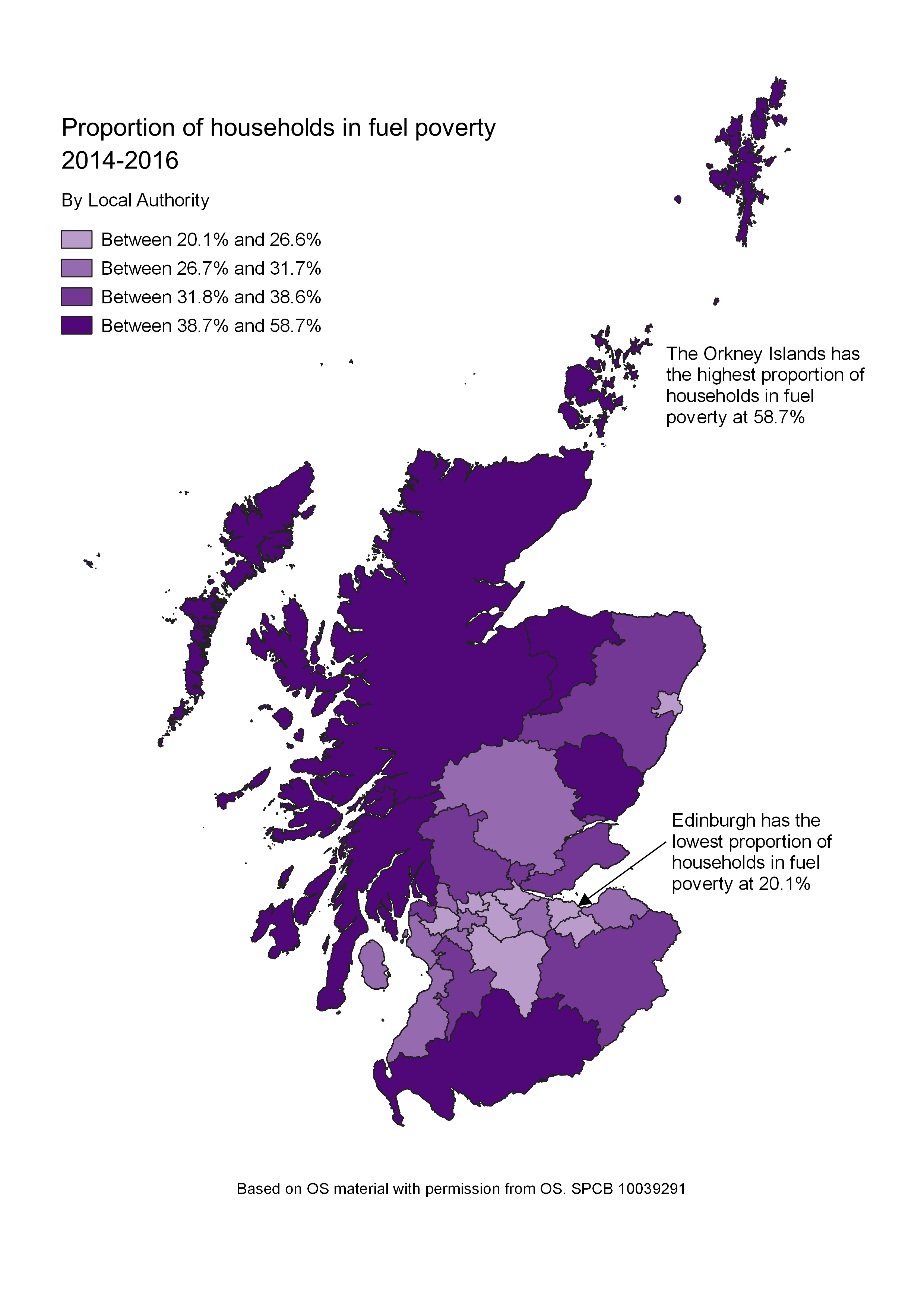

Levels of fuel poverty can vary regionally, with figures reaching as high as 59% of households in Orkney and as low as 20% in Edinburgh. The table below shows regional variations. The Committee heard that rural and island local authority areas have higher rates of fuel poverty than urban or suburban areas. Members who visited the Western Isles witnessed first-hand some of the work being done to tackle the problem.3

These figures are based on the current formal definition of fuel poverty, which the Bill would revise. This definition was associated with a previous target set by the 2002 Fuel Poverty Statement, published under section 88 of the Housing (Scotland) Act 2001: "so far as reasonably practicable, that people are not living in fuel poverty in Scotland by November 2016". This was not met. The Minister for Local Government and Housing wrote to the Committee on 29 June 2016 notifying the target would be missed despite the Scottish Government's investment of over £500 million in fuel poverty and energy efficiency initiatives since 2009.4

Past efforts to address the issue

It is widely recognised that there are four main drivers of fuel poverty:

the cost of energy;

the energy efficiency of the home;

household income; and

how households use the energy they buy.

The Scottish Government does not have direct devolved responsibility in relation to the cost of energy and household income, which are in any case partly influenced by factors that would be outwith the direct control of any government. The Committee heard that much of the focus of past initiatives to tackle fuel poverty had been on improving the energy efficiency of people's homes, an area where the Scottish Government has far more direct power and influence.1

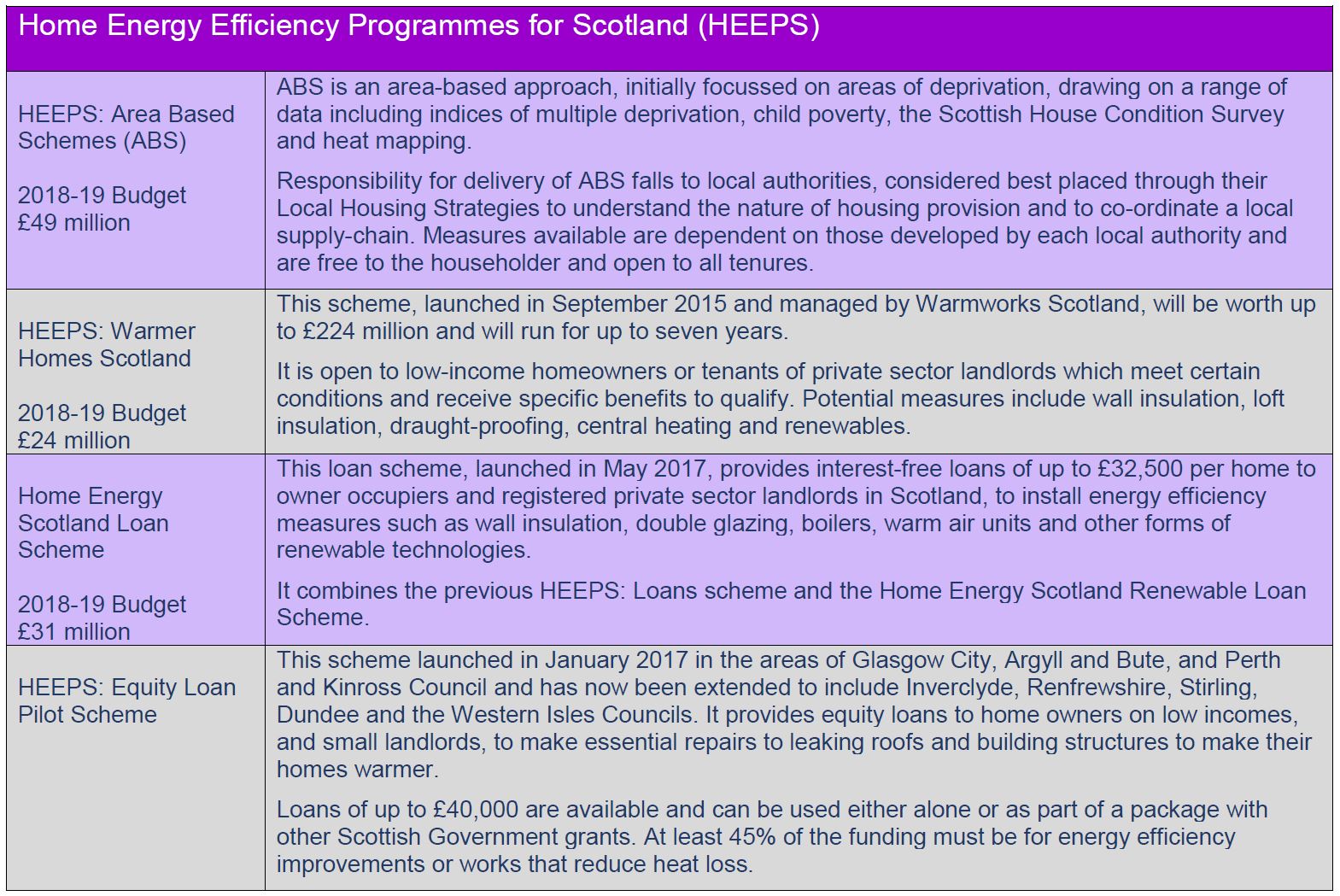

There have been a number of programmes to deliver improved energy efficiency. As noted, successive governments in Scotland have spent millions of pounds on initiatives and also channelled monies from UK-based funding models. Current programmes which are used to deliver the measures are contained in the table below.

The Committee heard about the benefits of such measures during scrutiny earlier this Parliamentary session of the draft climate change plan. We heard that they can improve not only the energy efficiency of the home, but also its value and attractiveness, and the health and well-being of its inhabitants. We heard this again during our scrutiny of this Bill.23 4

In relation to how householders use the energy they buy, there are local schemes providing advice to people on the most efficient ways to use energy at home; for instance, how to use heating appliances properly, how to switch services and get the best deals, and how to get smart meters. During Stage 1 scrutiny of the Bill, Committee Members witnessed first-hand the benefits of such schemes on our visits to Dundee and to the Western Isles.

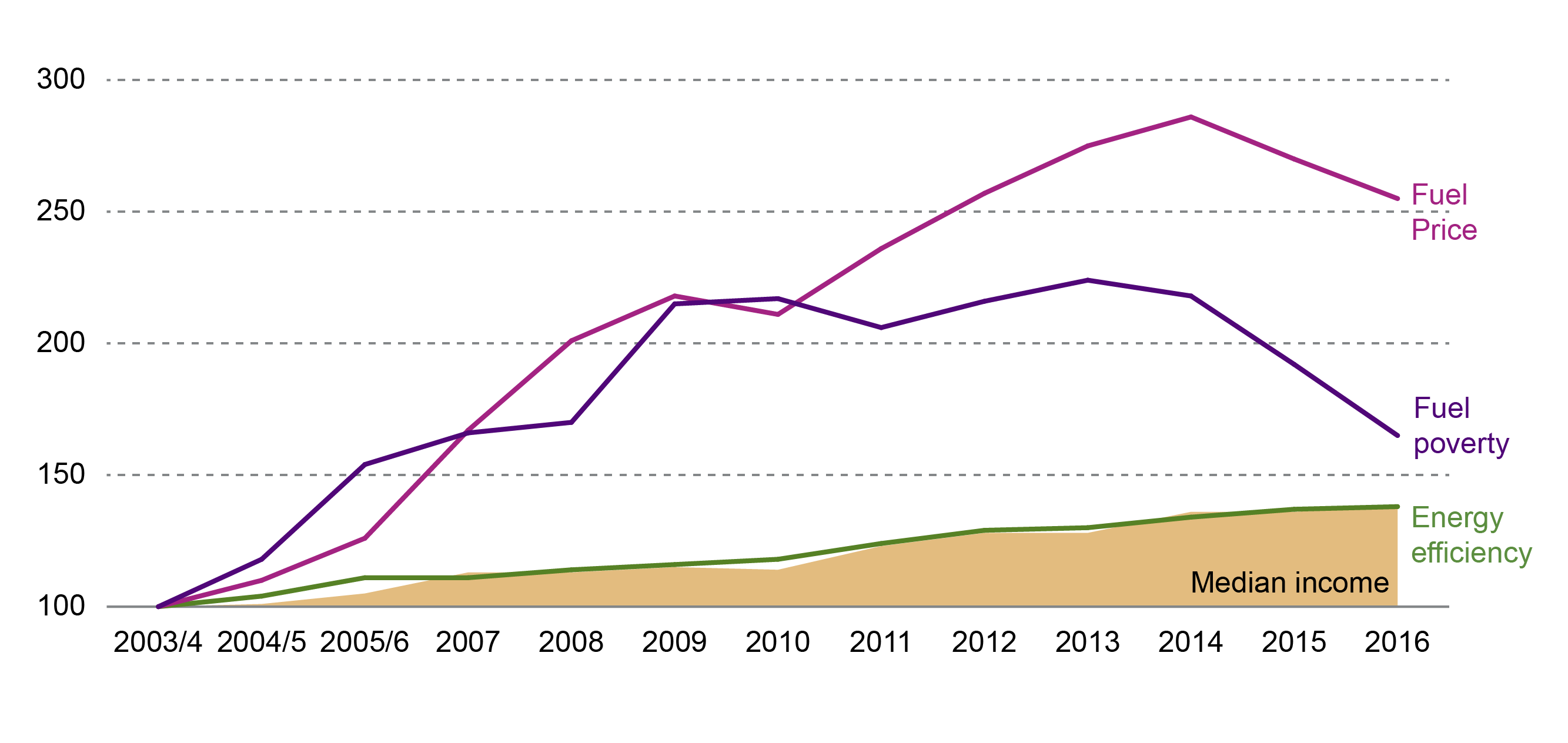

Energy prices have, overall, increased at a much higher rate than general inflation since 2002. The target that was missed in November 2016 was set at a time when prices were at a historic low. The Minister for Local Government, Housing and Planning told the Committee that, whilst median household incomes in Scotland rose by 50% between 2003/4 and 2017, fuel prices rose by 150%. He stated that had fuel prices increased in line with inflation since 2002 (35%), the 2017 fuel poverty rate under the current definition would have been 8.5%.5

The overall energy efficiency of homes in Scotland improved by 38% over the same period. This is welcome, but shows that we cannot rely solely on this measure if we want to bring down fuel poverty. The attached table shows how fuel prices have risen in comparison to household income and rates of fuel poverty between 2003 and 2016.1

Energy Efficient Scotland

The Scottish Government made energy efficiency of the home a National Infrastructure Priority in June 2015. It reaffirmed this position and committed to removing energy efficiency as a driver of fuel poverty in May 2018 when it published the Energy Efficient Scotland Route Map which delivers across two key policy areas, fuel poverty and climate change.

The Route Map sets the following targets:

By 2040 all Scottish homes achieve an EPCi C (where technically feasible and cost effective).

Maximise the number of social rented homes achieving EPC B by 2032, building on the existing standard, equivalent to EPC Band C or D, which social landlords must meet by 2020.

Private rented homes to EPC E by 2022, to EPC D by 2025, and to EPC C by 2030 (where technically feasible and cost effective).

All owner occupied homes to reach EPC C by 2040 (where technically feasible and cost effective).

All homes with households in fuel poverty to reach EPC C by 2030 and EPC B by 2040 (where technically feasible, cost effective and affordable).12

Working Groups and independent Definition Review Panel

When it became clear that the 2016 fuel poverty target was not going to be met, the Scottish Government established two short-life working groups (the Scottish Fuel Poverty Strategic Working Group (SWG) and the Scottish Rural Fuel Poverty Task Force (RFPTF)) to consider an approach to reviewing the definition of fuel poverty and make recommendations regarding a new fuel poverty target and strategy.

Their reports are available here:

One of the recommendations of the SWG, was to appoint an independent panel of academics to review the definition, and the Government established the independent Definition Review Panel which reported in November 2017.

The independent panel's recommendations acknowledged a criticism that a high number of households considered to be in fuel poverty under the existing definition, were not actually in financial distress.

The independent panel called for a new definition which assesses the affordability of fuel after housing costs, such as rent, mortgage, council tax, and water/sewerage rates, are deducted and incorporates a Minimum Income Standard (MIS) (the MIS is considered in more detail in the report’s section on the Bill legislating for a new definition).

The Panel proposed that households are in fuel poverty when:

they need to spend more than 10% of their after housing cost income on heating and electricity in order to attain a healthy indoor environment that is commensurate with their vulnerability status; and

once these housing and fuel costs are deducted, households have less than 90% of Scotland’s Minimum Income Standard (MIS) from which to pay for all the other core necessities commensurate with a decent standard of living.

They also proposed marking up the MIS for those experiencing disability or long-term illness and for those living in remote rural areas, in accordance with the view that those groups face higher costs of living.1

The Scottish Government broadly accepted this definition but also made some key changes, which are reflected in the wording used in the Bill. We discuss the definition the Bill uses, and stakeholders' views on it, later in the report.

The Bill

The Bill has 14 sections-

Section 1 sets out the Scottish Government’s target to reduce fuel poverty to no more than 5 per cent of Scottish Households by 2040.

Section 2 sets out a definition of fuel poverty.

Sections 3-5 require the Scottish Government to publish a fuel poverty strategy within a year of Section 3 of the Bill coming into force. It also sets out consultation requirements in relation to the strategy.

Sections 6-9 place interim reporting requirements on the Scottish Government: it must report to Parliament every five years on various matters in the years leading up to 2040.

Sections 10-14 contain various mainly standard provisions relating to modification and regulation-making powers, commencement powers, and the short title.

As stated above, if the Bill is agreed to, the Scottish Government must publish a fuel poverty strategy. A draft fuel poverty strategy was published alongside the Bill on 27 June 2018 and the Scottish Government has stated that it is consulting on the measures contained within it. The draft strategy is available here:1

https://www.gov.scot/publications/draft-fuel-poverty-scotland-2018/

At Stage 1, the lead Committee's substantive role is to report to Parliament on whether the general principles should be approved, and the Bill proceed to Stage 2. However, it is clear that achieving the target set out in the Bill would be heavily reliant in practice on a robust and realistic fuel poverty strategy that built on lessons learned from previous efforts and was backed by the resources necessary to put it into effect. A separate section of the report is therefore dedicated to consideration of evidence on the draft strategy.

During Stage 1, some commented on the narrow focus of the Bill. For example, the Existing Homes Alliance stated that its scope should be widened in order to create a-

'once in a generation' opportunity to tackle energy efficiency as well and end the scandal of Scotland's cold, damp homes. This Bill should support the achievement of warm, affordable to heat and low carbon homes for everyone in Scotland, so no one is at risk of being in fuel poverty.2

We note, however, that the Bill is part of a suite of measures which will not only improve the energy efficiency of Scotland's homes and buildings, but also lower climate change emissions. These include the Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Bill (also at Stage 1 at the time of publication), legislative and other measures to deliver the new Energy Efficient Scotland programme, the Energy Efficiency Route Map and the Draft Fuel Poverty Strategy itself.3

Outline of the Committee's Stage 1 scrutiny

The Committee agreed its approach to scrutiny of the Bill at meetings on 12 and 26 September, issuing a call for written evidence on Monday 17 September. This closed on 9 November. We received 67 written responses. A link to this evidence is at Annexe A.

We promoted the call for written evidence on the Committee’s Twitter account. A Facebook post with a featured animation reached 6,700 people, was viewed 1,900 times, and was commented upon 23 times.

https://www.facebook.com/scottishparliament/videos/p.341086850032844/341086850032844/?type=2&theater

The Committee held five oral evidence sessions with stakeholders and experts in November and December, concluding with an evidence session with the Minister for Local Government, Housing and Planning on 19 December.

Further details of these sessions are available on the dedicated Bill webpage here:

https://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/CurrentCommittees/109630.aspx

In addition to formal evidence taking, Members of the Committee made visits to Dundee and to the Western Isles during Stage 1 hearing directly from affected people about the different experiences of those facing fuel poverty in urban and rural/island communities. Reports of these visits are available here:

http://www.parliament.scot/S5_Local_Gov/Inquiries/20181129_FPB_DundeeNote.pdf

https://www.scottish.parliament.uk/S5_Local_Gov/Inquiries/20181219_FPB_WesternIslesNote.pdf

The Committee thanks all those who provided written and oral evidence and all those who engaged with us throughout scrutiny of the Bill.

Issues Explored

Section 1 - Fuel Poverty Target

The Target

Section 1 of the Bill sets out a new target to reduce fuel poverty to no more than 5 per cent of Scottish households by 2040. The initial Scottish Government consultation preceding the Bill set a target of 10 per cent. This was revised downwards following comments from many of the respondents that 10 per cent was not ambitious enough.

The Government states that it has set this target to place “Scotland amongst the very best in the world in terms of tackling fuel poverty”. A target of 5% is considered realistic in part because "households move in and out of fuel poverty due to changes in income and energy costs”.1

The Minister for Local Government, Housing and Planning told the Committee that-

Scotland is one of only a handful of European countries to define fuel poverty, let alone set a goal to eradicate it. Achieving the target will place Scotland among the very best countries in the world in terms of tackling fuel poverty.2

Almost all respondents to the Committee's call for written evidence agreed that having a target enshrined in legislation was a good idea, sending a strong signal of the Scottish Government's intent and the seriousness with which it proposed to treat the problem. For example, the Existing Homes Alliance said that a statutory target would provide "a clear end point to measure progress against”. 3

A consensus in favour of a legally defined target also emerged in oral evidence. Ross Armstrong from Warmworks Scotland told the Committee that-

“Politics is often a transient business: the policy priorities of an administration can change as things such as the macroeconomic climate change. However, a statutory target that binds the Government to committing to addressing fuel poverty over the longer term is a welcome and essential part of the strategy.”4

Simon Markall from Energy UK said that the Bill-

“would help to focus minds and give momentum to making sure that we meet the 5 per cent target that is set out in it. There are many aspects on which the strategy and plan that will come with the bill will need to focus, including where the money will come from to finance meeting the 5 per cent target. The 5 per cent target is good, and we broadly support it, but in order to meet it, a clear plan and strategy on how the Government will deliver it are needed.4

The Committee supports the principle of setting a statutory target for reducing fuel poverty within a set time period.

Eradication versus a 5% target

There was far less consensus on whether 5% was the right target or whether 2040 was the right date. There is clearly an inter-relationship between these two issues (the longer the time period, the more opportunity there would be to drive the numbers down) but in this report we will consider the evidence received on each separately.

Some evidence argued that the 5% target was not ambitious enough. A target of 5% is self-evidently not "eradication"; the long-term policy goal set out in the long title to the Bill. Currently, 5% would amount to around 140,000 households, a substantial number of people, and some evidence expressed concern that this would inevitably tend to include those hardest to reach and most in need of help. Energy Action Scotland, the Existing Homes Alliance, the Poverty Alliance, the Chartered Institute of Housing and the Scottish Fuel Poverty Advisory Panel were amongst those arguing that the target should be 0%, generally caveated that this should be as far as reasonably practicable.1 2345

Elizabeth Leighton from the Existing Homes Alliance said-

We acknowledge that there are people who move in and out of fuel poverty and that we might not be able to get that down to absolute zero. There will be particular times when that is not possible, but we think that that is a reasonable position and that that is an achievable and credible target for us to strive for.6

Ross Armstrong from Warmworks Scotland argued that the prior wording of the target: to (by November 2016) eradicate fuel poverty, “so far as reasonably practicable” was-

... a more logical approach. As far as I am aware, 5 per cent is an arbitrary number. Four per cent, 7 per cent and 10 per cent are also arbitrary numbers. The words “so far as reasonably practicable” recognise that fuel poverty is a difficult thing to pin down. People move in and out of it, often from day to day, as their circumstances change. Even if 5 per cent were to be reached by the 2040 target date, the following day the figure might need to be 5.5 per cent or 6 per cent, because an increase in fuel prices might be announced that would push another 5,000 people into fuel poverty.7

Other evidence, whilst welcoming a target overall, expressed concerns that the rationale for a 5% target had not been set out and that it appeared unambitious. They argued for a target closer to 2 or 3%. (e.g. North Lanarkshire Council8 , Energy Agency9 )

However, a signficant body of evidence expressed support, or qualified support, for a 5% target as representing the right balance between ambition and realism, and the Scottish Government's limited influence in relation to two of the four main levers. These included, for example, Argyll and Bute Council and the Rural and Islands Housing Association Forum, the latter of which argued that the target seemed fair given that “the total elimination of Fuel Poverty is neither achievable or totally within the power of the Government.”9 11

Citizens Advice Scotland (CAS) expressed a similar view in written evidence. However, in oral evidence, CAS's representative Craig Salter argued that, if and when the statutory target was met, it would be crucial to keep up the pressure to bring the figure down further-

If that 5% of households are hard to reach or have a greater support need, more resource has to be put towards supporting them.12

The Minister for Local Government, Housing and Planning described the target in the Bill as-

... challenging but achievable and, importantly, deliverable. Of the four key drivers of fuel poverty, two are outwith our direct control: fuel prices and income. Therefore, we are concentrating on the two drivers that we can change: poor energy efficiency and how energy is used in the home. We must bear in mind that most Scottish homes are owner occupied. Bringing such households out of fuel poverty will involve an unprecedented level of intervention in private homes that relies on technology being affordable and in line with low-carbon technologies.13

The Minister confirmed that the Scottish Government's long-term plan remained eradicating fuel poverty, but that-

There will always be a small number of people who move in and out of fuel poverty due to a change in their income or the cost of energy. It is also important to note that the target is for no more than 5 per cent of households to be in fuel poverty by 2040. If we manage to get the level down to 5 per cent, we will not just say, “Job done” and stop trying; our ambition is to ensure that as many folk as possible are out of fuel poverty.14

The Committee accepts that setting a statutory target for reducing fuel poverty is ultimately a matter of judgment. We are satisfied, on the basis of evidence led, that the target of 5% set out in the Bill is achievable and at the same time would make a real difference to the lives of hundreds of thousands of people were it to be achieved. On balance, it appears to us to strike an appropriate balance between realism and ambition. The 5% target also recognises the Scottish Government's limited influence in relation to two of the four main drivers of fuel poverty, and its transient nature, with the potential for individual households to move in and out of the definition, depending on changing circumstances in relation to which governments may have little or no direct control.

The Committee agrees with the Scottish Government that the more long-term ambition should be the eradication of fuel poverty, as much as is realistically possible, and that the 5% target should not be the limit of this or future government's ambitions. With robust monitoring systems in place (as discussed later in the report), there is the opportunity to learn from experience and to benefit from technological advances between now and the target date.

The length of the target

Another significant area in which views differed was as to the date set out in the Bill for when the target should be reached. The Bill provides that the 5% target should be reached "in the year 2040"; in effect, therefore by no later than the end of that year. The difference of views at Stage 1 was between those who considered this time period about right and those who thought it should be shorter. The latter group proposed 2032.

In the Policy Memorandum, the Government argued that the 2040 date had been selected because it was consistent with other policies and measures to address fuel poverty, such as a commitment to remove energy efficiency as a driver for fuel poverty by 2040, by maximising the number of homes reaching minimum EPC ratings. These measures are in the process of consultation. However, the current proposal is that all fuel poor households reach EPC band C by 2030 and EPC band B by 2040.

The Government's view is that reaching the 2040 target of fuel poverty no higher than 5% would require widespread use of cost-effective low carbon heating technologies. It argues that bringing forward the date could create inefficiencies or even perverse incentives that are contrary to climate change goals. For instance, it could encourage increased use of existing higher carbon heating fuels or require further upgrades to renew heating systems in the future to bring them in line with low carbon technologies. The Policy Memorandum adds that currently there is uncertainty on how to best decarbonise Scotland’s energy networks. It says that decisions regarding the operation of the gas network are reserved to the UK Government and there is not yet a strong evidence base on how best to decarbonise it. The Scottish Government argues that without more time to drive down the cost of energy technologies, there is a risk that, if anything, more people could be drawn into fuel poverty because of the high cost of pioneer reduced carbon technologies. Finally, the Scottish Government, in the memorandum, again refers to those drivers over fuel poverty in relation to which it had less control as another reason not to bring the date forward from 2040.1

A large number of stakeholders disagreed. They argued that 2040 was too distant, noting that the previous target, set in 2002, as well as being more ambitious, covered a shorter period of 14 years. Organisations arguing for a 2032 target included West Lothian Council, Citizens Advice Scotland, the Rural and Islands Housing Association Forum, Inclusion Scotland, East Ayrshire Health and Social Care Partnership, the Existing Homes Alliance, and the Highlands and Islands Housing Associations Affordable Warmth Group. Energy UK argued that an earlier date "could help concentrate minds". 234567

CAS was amongst a number of organisations to highlight that a shorter period would also bring policy in line with targets which have been set to improve the energy efficiency of social housing and general energy efficiency standards. It added that not aligning the target in the Bill with the 2032 energy efficiency target would put undue focus on the driver relating to energy efficiency. Craig Salter of CAS told us-

“As has been pointed out already, all the drivers of fuel poverty interact. They all have a significant impact and, as a result, they all need to be addressed together. If we are saying that we can achieve improvements in energy efficiency by 2032, work should be on-going alongside that to address the other drivers too. In that regard, 2032 is an achievable target.8

David Stewart, representing the Scottish Federation of Housing Associations agreed, adding that a 2032 date would also align better with the Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Bill (also at Stage 1 during the Committee's consideration of this Bill) and the Climate Change Plan.9

Norman Kerr of Energy Action Scotland queried why the development of low-carbon heating technologies should be put forward as a reason for not bringing forward the date to 2032. He said that the 2040 date "condemns another generation to fuel poverty". Mr Kerr said that-

The electricity grid in Scotland is now mainly low carbon. We will have our gas grid for many years to come and we will not replace it, although we are looking at technologies that reduce the amount of carbon in the gas mix, such as biofuels and a range of other mixes, including hydrogen. However, simply giving someone low-carbon heat does not take away the fact that they are fuel poor. It may actually contribute to their fuel poverty if there is a significant additional cost of the technology that is applied to gain that low-carbon heat, such as completely stripping out the gas grid and moving to electricity alone for heating…10

Organisations including StepChange Debt Charity and the Energy Agency recognised the pragmatic reasons for a longer target date, but expressed concerns about the impact it could have on vulnerable individuals. Lawrie Morgan Klein of StepChange referred to data they held indicating that-

... electricity arrears is the second-fastest growing debt type— such arrears have gone up by about 37 per cent between 2013 and 2017…It is a growing problem in Scotland, so we welcome there being a target to tackle it. The timeline to 2040 feels distant, considering that we have seen a 4 per cent increase in clients who are struggling with energy costs, so that is a concern.11

In contrast, most local authorities who gave evidence at Stage 1 were less supportive of moving the date forward, on pragmatic grounds. Council witnesses tended to agree with the Scottish Government that a longer time period would allow more time to harness low carbon technology.12

Councils agreed that their reluctance to back an earlier target date related to a lack of clarity around funding and resourcing in the fuel poverty strategy (which will be discussed in more detail later), given the large role they would be expected to play in actually delivering the strategy. Glasgow City Council's Patrick Flynn referred to the complexity of funding schemes, which had also changed significantly over the last few years, which made significant demands on human resources within councils. He said that-

... the 2040 target is a recognition that, if we get interim milestones and certainty about funding, we can make our local strategy work as well as we can so that we can contribute to the national strategy.13

Alasdair Calder, from Argyll and Bute Council, argued that the 2040 target date represented a credible timescale, indicating that lessons had been learned from the previous missed target and that it was not just technical and technological changes that were required-

There is still resistance to switching to lower tariffs, and it will take a long time to change householders’ attitudes. I am a little uncomfortable about bringing behaviour into the discussion, because there is a tendency to sound as though we are saying that people make themselves fuel poor, and I do not believe for a minute that anyone does that. However, there is no doubt that behavioural changes are required. That will take time and resources. I am talking about the old fashioned resource of feet on the ground—people going out to talk to people and coach them through a process.14

Warmworks Scotland told the Committee that, whilst setting a date in legislation was important, the focus should be as much on having a properly resourced governmental plan, with additional dates, targets and milestones.15

In his evidence before the Committee, the Minister made clear that the Scottish Government's preference remained a 2040 target date-

The 2040 target aligns with the energy performance certificate targets that are in “Energy Efficient Scotland: route map”, and it lends itself to the achievement of the interim target in the Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Bill that by 2040 Scotland’s net emissions must be at least 78 per cent lower than the baseline. If we bring the fuel poverty target forward to an earlier year, that would mean utilising technologies to reduce fuel poverty that rely on existing high-carbon heating fuels. In some cases, that might lead to households needing two interventions in order to meet climate change objectives as well as everything else.

The Minister said that a 2040 target would also give more time to-

“set in place a pipeline that allows companies to boost the skill sets that are required in various parts of Scotland, rural and urban. They can then benefit in terms of employability in delivering the schemes. I think that 2040 is realistic; it is ambitious, but we can do it.16

Interim targets

The Scottish Government has set some non-statutory interim targets to measure progress in reaching targets set out in the Bill (should the Bill be agreed to). By 2030:

The overall fuel poverty rate will be less than 15%.

Ensure the median fuel poverty gap is no more than £350 (in 2015 prices before adding inflation).

Make progress towards removing poor energy efficiency of the home as a driver for fuel poverty.

And by 2040:

Ensure the median fuel poverty gap is no more than £250 (in 2015 prices before adding inflation).

Remove poor energy efficiency of the home as a driver for fuel poverty.1

During Stage 1 scrutiny, a number of stakeholders, such as the Existing Homes Alliance, called for the interim targets to be statutory.2

At the meeting on 19 December, the Minister confirmed that, if the Bill proceeds past Stage 1, he would bring forward amendments at Stage 2 to enshrine two interim targets in law: that by 2030 the overall fuel poverty rate will be less than 15%; and that by 2030 the median fuel poverty gap is no more than £350.3

The Committee notes concerns regarding the length of the target date set out in the Bill, which at 21 years is considerably longer than the 14-year target previous Scottish administrations had worked to. However, the Committee also understands views that this approach is a pragmatic response to previous attempts to set a target, which ultimately failed. We also recognise arguments that reducing fuel poverty will lean heavily on applying technologies still in development and that it is realistic to build in time for these to come on-stream.

The Committee therefore accepts the Government's reasons for setting the target date at 2040. This would however be conditional on the Government bringing forward amendments to make at least some of its interim milestones statutory by way of amendment at Stage 2, and we are pleased to note that a public commitment has been made to enshrine two of these at Stage 2. If the amendments are agreed to, this should help protect the fuel poverty strategy from "drift", and enable comprehensive assessment of how well the strategy is working at its mid-point.

Extreme Fuel Poverty

The 2003 Scottish Executive Fuel Poverty Statement defines extreme fuel poverty as when a household has to spend over 20% of its income on fuel. The annual Scottish House Condition Survey includes data on extreme fuel poverty. However, evidence at Stage 1 commented that there is no mention of measuring or targeting extreme poverty in the Bill, Policy Memorandum or draft Fuel Poverty Strategy.

The Committee heard of concerns that a lack of emphasis on tackling extreme fuel poverty could risk there being a focus on prioritising “low hanging fruit” to meet the 5% target, i.e. the easiest to treat properties, meaning that those in the most extreme circumstances, with the most difficult to treat issues, would end up disproportionately in the 5% still facing fuel poverty.

In their written submissions, organisations including the Wheatley Group and the Scottish Federation of Housing Associations called for explicit recognition of extreme fuel poverty in the Bill or for other measures to prevent the strategy failing to prioritise those in extreme fuel poverty. The Highlands and Islands Housing Associations Affordable Warmth Group further suggested an additional target in the Bill: “the elimination of extreme fuel poverty by 2025.”123 In oral evidence, Dion Alexander, representing the group, told the Committee-

In our submission, we ask that extreme fuel poverty should continue to be measured, because it will provide a guide to what is going on in the elimination of the worst forms of fuel poverty. We say very firmly that extreme fuel poverty is intolerable in a civilised society and that it should be eradicated as quickly as possible— within five years.4

In oral evidence, representatives of the Existing Homes Alliance, the Energy Agency, StepChange Debt Agency, Argyll and Bute Council and Glasgow City Council all agreed, with Alexander Macleod of Aberdeenshire Council, noting the potential for "unintended consequences if the measure were not added.5 Elizabeth Leighton of the Existing Homes Alliance suggested that-

We may be able to look for examples from the Child Poverty (Scotland) Act 2017, which talks about “persistent poverty”. The risk is that, if we allow for 5 per cent, those people will be the most difficult, hardest and most expensive to reach, and they will just be left behind. We cannot be in a position where we say that it is okay for that 5 per cent to continue to live in fuel poverty in 2040—surely that is unacceptable.67

The Minister for Local Government, Housing and Planning told us-

In our draft strategy we proposed fuel poverty gap targets for 2030 and 2040, which consider the depth of fuel poverty. That, in effect, is a measurement of the size of the gap between the bill for the fuel that a household requires to stay warm and its spending 10 per cent of its income on fuel. The independent panel suggested such a measure in respect of the proposed new definition; it was suggested as a means by which the severity of fuel poverty can be better understood. The approach that we are proposing in all that we are doing is therefore in line with the panel’s view and is designed to tackle the situation of folks who are in extreme fuel poverty.8

The Committee notes concerns from stakeholders working with those in extreme fuel poverty (i.e. those having to spend more than 20% of their income on fuel) about the lack of explicit reference in the Bill to prioritising a reduction in extreme fuel poverty. We heard that, without such a reference, there is a risk, even if the overall target is ultimately met, of efforts being targeted at "low hanging fruit". This could leave a disproportionate number of those with the most critical needs remaining in the final 5 per cent facing fuel poverty by 2040.

We ask the Government to bring forward proposals for a separate target for targeting extreme fuel poverty at Stage 2, and to ensure that there is specific reference to eradicating it in any strategy produced under the Bill.

Local Targeting

The Bill sets out a national target for reducing fuel poverty. As with the discussion on extreme fuel poverty, some stakeholders expressed concerns that this might create an incentive for local authorities to target "quick wins", rather than households with more critical needs. The Committee also heard views that local targets should be set, to ensure that there was a nationwide effort to reduce fuel poverty. As noted earlier, there are big disparities between local authority areas. In particular, rural and island authorities tend to have far greater problems with fuel poverty. A number of local authorities who provided evidence argued that setting local targets would increase the likelihood of resources under the fuel poverty strategy being better directed.12

Argyll and Bute Council argued in their written evidence that the risk with a "blanket" nationwide target was that "householders in remote and rural areas will be disproportionately represented in the residual" even if the 5% target were met.3

In oral evidence, Alasdair Calder, representing Argyll and Bute Council, said there was scope to further break down the target at local level, to reduce the risk of pockets of fuel poverty remaining in particular sectors and areas-

We have nine distinct housing market areas in our local housing strategy, and we could operate the target at that level—we could say that the 5 per cent target applied in each housing market area.4

A key theme to have emerged during Stage 1 is the particular fuel poverty challenge that exists in island communities. Referring to Coll and Tiree, Alasdair Calder of Argyll and Bute Council referred to-

... the issue of getting the workforce over there, the supply chain issue and the difficulty of the location. That all adds up to its being an extremely difficult area to deal with, for which extra resources will be needed. At the same time, if we addressed the whole of Argyll and Bute, we would not want our 5 per cent to be disproportionately located on our islands or in remote rural areas. Whatever the challenge is nationally, we should face that challenge locally to make sure that we have a good distribution of all the schemes that we operate.5

The Energy Agency's Liz Marquis highlighted how Councils could be creative in how they allocated their area based schemes-

The area-based schemes that we are talking about have some flexibility. That is really important—everything should not be too rigid; there should be a bit of flexibility. The project in Dumfries and Galloway that I have been talking about comes out of the council’s budgets for tackling poverty in the area. There are creative ways of doing things inexpensively that help lots of people. We should try to combine that creativity with quite rigid rules about what we should be doing and achieving in the long term.5

Ross Armstrong of Warmworks, which runs the Warmer Homes Scotland programme, demonstrated how the current mechanisms target those areas with the greatest need and felt that this needed to be a key aim of the strategy-

It is important for the Government to ensure that, as part of the fuel poverty strategy, national instruments are properly set up and incentivised to target areas where need exists.

Our contract with the Government has been set up in a specific way to ensure that we go where need presents itself. Just under a fifth of all the work that we do is in the Highlands and Islands, for example, in areas that will have some of the worst levels of fuel poverty. That means that, in population terms, our work is disproportionately skewed towards those areas where the need for warmth—and for affordable warmth—is clearly greater.

He added-

The Government should learn the lesson of the past three years of our programme, which is that you can clearly direct help to where it is needed most if your contract, your key performance indicators, and all the targets that you have to hit and report on monthly are properly set up to tackle the areas where need is greatest.7

On whether the Scottish Government would consider targets for each local authority, the Minister for Local Government, Housing and Planning said-

We need to take into account the difficulties that exist in certain places. We as a Government have ensured that the allocation of resource reflects the needs of various places. For example, our island councils benefit from three times more spend per head of population on HEEPS ABS than those on the mainland, because we recognise the differences that exist in those communities.

Three or four weeks ago, I announced further flexibilities in delivery in island communities. We are looking at bringing new things into schemes, such as microgeneration, the removal of asbestos and the installation of oil tanks. We will continue to look at those flexibilities and I will consider having further discussions with local authorities about setting individual targets if that is deemed appropriate.8

Given that island areas receive more spend per head on energy efficiency measures than mainland communities, it is concerning that inordinate numbers of householders on our island communities still experience fuel poverty. We believe that the Scottish Government should consider amending Section 1 of the Bill to put in place statutory targets for each local authority to reduce fuel poverty in their areas to no greater than 5 per cent of their households by 2040, in order to help drive progress towards achievement of the national target and eliminate regional disparities.

The Committee understands concerns that there may be a tendency for local authorities to direct resources at the most easy to treat properties in order to meet the new statutory target. We welcome the Minister’s commitment to continue to work with local authorities to consider how best to distribute schemes to balance the requirements of those with the greatest needs for support and those with more marginal problems. We, however, urge the Government to ensure that the fuel poverty strategy will provide clear, helpful and practical guidance to local authorities on how best to distribute their resources to avoid local disparities.

We also heard of the innovative local schemes already in place which allow services to be creative around how they distribute their resources to reduce such anomalies and seek further information on how the Government will ensure the sharing of best practice between local authorities. This applies particularly to island communities which often struggle to achieve the economies of scale that can be achieved on the mainland.

Section 2 - Definition of Fuel Poverty

Previous definitions of fuel poverty in Scotland were based on the Boardman definition which states that a household is fuel poor if it is "unable to obtain an adequate level of energy services, particularly warmth, for 10 per cent of its income".1

In 2002, the then current Scottish Executive refined the definition. The aim was to achieve a more precise definition that would enable better targeting of resources-

A household is in fuel poverty if, in order to maintain a satisfactory heating regime, it would be required to spend more than 10% of its income (including Housing Benefit or Income Support for Mortgage Interest) on all household fuel use. The definition of a 'satisfactory heating regime' would use the levels recommended by the World Health Organisation. For elderly and infirm households, this is 23° C in the living room and 18° C in other rooms, to be achieved for 16 hours in every 24. For other households, this is 21° C in the living room and 18° C in other rooms for a period of 9 hours in every 24 (or 16 in 24 over the weekend); with two hours being in the morning and seven hours in the evening. 'Household income' would be defined as income before housing costs, to mirror the definition used in the UK Households Below Average Income (HBAI) Statistics.2

It was recognised during the 14 year period of the previous target that a minority of households caught by the definition might not, by most conventional measures, be income poor and might not, in fact, be struggling to pay fuel bills.3

Earlier in this report, we noted the work of the short life working groups set up by the current Scottish Government, when it became clear that the prior target would not be met, and the defintion they produced. They intended, in revising the definition, to more closely align the target to income poverty.

The definition in section 2 of the Bill largely adopts this definition. It provides that-

A household is in fuel poverty if -

(a) the fuel costs necessary for the home in which members of the household live to meet the conditions set out in subsection (2) are more than 10% of the household's adjusted net income, and

(b) after deducting such fuel costs and the household's childcare costs (if any), the household's remaining adjusted net income is insufficient to maintain an acceptable standard of living for members of the household.4

This new definition switches the assessment of fuel poverty from before housing costs (BHC) to after housing costs (AHC). In other words, the affordability of fuel is assessed against income after deduction of housing costs (rent, mortgage, council tax and water rates) and childcare costs.

The calculation uses an income threshold measure known as the Minimum Income Standard (MIS) to determine an acceptable standard of living. The MIS is currently determined by the Centre for Research in Social Policy at Loughborough University in conjunction with the Joseph Rowntree Foundation. The Policy Memorandum states that the "consistent and simple standard" of 90% of MIS set out in the Bill better enables regional variations to be taken into account. It adds-

This approach ensures that households only marginally above the income poverty line that are struggling with their fuel bills, will be captured in the new definition of fuel poverty. The new definition also excludes higher income households, even if they would need to spend 10% or more of their net household income after housing costs on required fuel costs. This addresses a drawback, highlighted by the Panel, of the current definition where households with quite high incomes could be classified as fuel poor.

It adds-

This will allow the Scottish Government to focus the definition of fuel poverty, and targeting of support, onto those most in need, regardless of where they live.5

Enhanced heating requirements

The conditions in Subsection (2) set out the requisite temperatures and length of time to be maintained at that temperature for standard and for those which require enhanced heating. For those who require enhanced heating, the requisite temperatures are-

23 degrees Celsius for the living room;

20 degress Celsius for any other room;

for 16 hours a day. Otherwise, requisite temperature are

21 degrees Celsius for the living room;

18 degrees Celsius for any other room;

for-

9 hours a day on a weekday;

16 hours a day during the weekend.1

The Bill does not define who is deemed to require "enhanced heating." There is a regulation-making power to do this. The Policy Memorandum states that it will include households where a member is elderly, or has a condition or illness which makes that person especially at risk of suffering adverse effects from being in a cold home.2

The Scottish Government accepted a recommendation by the fuel poverty expert panel that being over the age of 60 should not, in itself, be a threshold for vulnerability, as it was under the previous definition. It proposes under regulations to set 75 as the relevant age at which enhanced heating is required.

There were two recommendations by the expert review panel that the Scottish Government did not take forward. These were that the MIS should be marked up for those experiencing disability or long term illness, and for those living in remote rural areas.3

MIS and rural uplift

During consultation before the Bill was introduced, most stakeholders welcomed the new definition. The general view was that this would better align fuel poverty with income poverty. However most views were critical of the decision not to adopt a Scotland specific MIS to reflect the additional cost of living in Scottish rural and island areas.

In the Policy Memorandum, the Government argues that the additional living costs faced by remote and rural households are already accounted for within the modelling used to estimate fuel poverty. Thus, it says, there is no need to adjust the MIS for the new definition. The Draft Fuel Poverty Strategy explains-

the way fuel poverty is calculated already takes account of regional variations in external temperatures, solar irradiance and exposure to the wind as well as types of stock and information about occupants. These can lead to greater energy usage estimates to maintain either standard or vulnerable heating regimes in rural and remote rural areas. In addition, regionalised (North and South Scotland) energy prices are used in the fuel poverty calculation (for mains gas and electricity).1

Most of the evidence the Committee heard at Stage 1 broadly supported the new definition and, in particular, the use of the MIS within it. For example, the Highlands and Islands Housing Associations Affordable Warmth Group said that using the MIS would “underpin and inform the evidence-based understanding of poverty and the amount of disposable income that people have.” However, it was amongst a number of stakeholders to query the exclusion of a rural MIS. Dion Alexander referred to research carried out by Highlands and Islands Enterprise in 2013 and 2016, telling the Committee that-

The independent panel of academics that came up with the new fuel poverty definition recognised that there was a particular problem in remote rural areas of Scotland and suggested an uplift, in the same way, for example, that we have a London uplift on the MIS UK data when it is used to inform the living wage. We are asking people to do the same thing for remote rural Scotland, because we know from the MIS remote rural Scotland data that, depending on their household type and location, families in remote rural areas need between 10 and 35 per cent more income to achieve the same basic standard of living as those in households elsewhere. That has to be a fundamental contributor to fuel poverty; it is not the only contributor, but it must be recognised in any definition if that definition is to have credibility and serve the purpose for which it is designed.2

This view was shared by amongst others, CAS and the SFHA, with the latter noting that it was in rural off-gas areas that problems with fuel poverty tended to be especially acute.3

Dr Keith Baker of the Energy Poverty Research Initiative said that-

It has become quite clear—particularly from our work, but also from the Scottish house condition survey stats—that there is a question about whether we need a remote rural adjustment in the definition. Is the condition of fuel poverty in rural areas and, in particular, remote rural areas significantly different from its condition in urban areas? It is very clear that the answer to that is yes… and the new SHCS stats show that the increase in fuel poverty over the past year has been proportionally higher in rural areas.4

In a letter to the Committee sent at the start of Stage 1 oral evidence-taking, the Scottish Government set out further reasons for not supporting a rural MIS.

BREDEM calculations: The Government said that the higher costs of domestic fuel bills in remote rural and island areas are addressed in the measurement of fuel poverty under the proposed new definition by the use of BREDEMi, which it says-

already takes into account regional weather conditions. In response to concerns raised by rural and island stakeholders, we are further reviewing the weather information used in this estimation, together with the fuel prices pertaining to fuel types other than gas and electricity, with the aim of making these more localised where possible.

Alignment with other measures of poverty and uplift for delivery of energy efficiency measures in rural, remote rural and island areas: The letter said-

we believe that our approach to using UK MIS aligns with other measures of poverty such as the national minimum wage, minimum living wage and (real) living wage and other measures of poverty based on income, such as child poverty. Our approach aligns with other strategies to tackle poverty, reduce child poverty, improve health outcomes and make Scotland a fairer country.

The letter added that the Government would further review the weather and fuel cost information applied in BREDEM, using a model that would take account of house type and construction and the fact that rural, remote rural and island dwellings tend to be harder to heat. Via the strategy, it would also seek to develop innovative approaches and enhancements to delivery routes which currently take account of the additional costs of delivering energy efficiency measures in rural, remote rural and island areas, which provide higher funding per household and grant caps.

Cost: The letter stated that the regional MIS would be costly to develop and maintain at around £0.5 m over a 4 year period and that this was not good value for money-

The vast majority of the decrease in fuel poverty in rural, remote rural and island areas is due to the fact that an income threshold has been introduced at all rather than the value of that income threshold. The outcome [of a rural MIS] is unlikely to produce the desired effect for many stakeholders. We feel that the resources required to develop this would therefore be better utilised in the delivery of support to fuel poor households, including those in rural, remote rural and island areas.5

Some witnesses questioned the arguments set forth in the Scottish Government's letter. Dion Alexander, of the Highlands and Islands Housing Associations Affordable Warmth Group, queried the government's cost estimate but said that, even if it were accurate, it would be money well spent. Norman Kerr of Energy Action Scotland said-

On the figure of £0.5 million over four years, if we amend BREDEM—there is a reference to the need to amend BREDEM—that will not be free, but that has not been costed. I think that the figure has been given to demonstrate why we should not apply a remote rural uplift, rather than why we should. In the great scheme of things, £0.5 million over four years is a drop in the ocean to get more accurate reporting that will enable us to dedicate resources to a particular area. I am sorry, but I think that the figure is a smokescreen.6

CAS agreed, noting that Loughborough University and Highlands and Islands Enterprise had already undertaken some research on developing a rural MIS. CAS's Craig Salter told us that-

in the Scottish house condition survey, methodologies are revised and applied retroactively so, even if there were a short delay, there is no reason why a remote rural uplift should not then be applied once the information is ready. A delay is not a reason not to do it.7

The Committee heard directly from Professor Donald Hirsch, the leading expert on this issue at Loughbourgh University, and who had been instrumental in developing the definition used in the Bill. He confirmed that his team had been funded by Highlands and Islands Enterprise and partnership organisations to do a study on a remote rural MIS. Professor Hirsch said it would not take much more work to produce a measure. He told us-

The calculations in the independent review panel’s proposed measure used a crude estimate that was based on the work that we have already done on remote rural Scotland. The panel used that to come up with its estimates of what the results would be if you had that element. The method is there, the work has been done and it could be regularly updated. The issue about whether any extra research would be required is about whether one updates something that has already been done in those areas.

The Committee asked Professor Hirsch how much effort would be required to maintain the remote rural MIS as an accurate and useful measure. He told us that-

It would involve making sure—not every year, but on a regular cycle—that the estimate of additional, non-fuel costs in the areas concerned kept in touch with reality and that, when a premium was applied to the UK MIS, that was adjusted whenever the UK MIS changed, because the starting point would be different. There are light-touch ways of doing that—it could be done in more or less detail, depending on how many areas were looked at. Some additional qualitative research of the kind that we did, which involved talking to people in those areas about the extra costs, would be required, as well as some regular, fairly routine updating of prices.

On costs, he said his "broad estimate" was that-

... it would cost between £50,000 and £100,000 a year. I do not know why the Government has said that it would cost £0.5 million over four years rather than five—in our view, that would be a maximum. Is that a lot of money? I read that the Government spends around £100 million addressing fuel poverty, and £50,000 to £100,000 is not very much in comparison with that. I reckon that the Government spends about £2 million on the Scottish house condition survey. If you want to make sure that you target things properly, you need to spend a small amount on gathering knowledge.

Professor Hirsch said that the main case for a remote rural uplift was mainly the high cost of travel and delivery charges for people living in these areas. He added-

The independent review panel estimated that in remote rural Scotland, according to its measure, which included the adjustment that we are discussing, the fuel poverty rate would be 40 per cent. The Scottish Government's technical annex estimates the fuel poverty rate in those areas as being 28 per cent. I do not think that that is a negligible difference.

There are all sorts of technicalities to do with how those measures are compared, but the underlying point is that if, as our evidence suggested, it can cost 25 to 40 per cent more to live in such an area, why would having a threshold that was that much higher not make a difference to the number of people who we say are in fuel poverty?

We asked Professor Hirsch for a view on a Scotland-specific MIS, which some stakeholders, including Energy UK had proposed. He confirmed that there had been some research into this at Loughborough University, and the conclusion reached was that there was “close to zero difference” between urban areas in England and Scotland.

The Scottish Government formally classifies communities by how urban or rural there. There are six classifications, with category 1 the most urban. Category 6 refers to settlements with a population of fewer than 3,000 people which are more than half an hour’s drive from a larger town. Amongst those in favour of a specific recognition of rurality in the definition, there was further discussion as to whether it would be sufficient to map category 6 communities onto the definition, or whether category 4 communities should also be incorporated into any additional calculation of MIS.8 ii Referring to his team's prior work on identifying a rural MIS, Professor Hirsch explained that-

... what we called remote rural Scotland included towns such as Thurso, Stornoway and Lerwick. I suspect that the review panel’s initial calculations looked only at category 6, but I would submit that there is just as much of a case for including category 4. It is all part of the same work, and we have made the calculations in that respect. Whether a person lives in Thurso or in a village outside it, most of the same costs apply, because those who live in the town still have to travel quite far to get to work or have no access to a supermarket and therefore have to pay higher prices.9

Professor Hirsch confirmed that all island communities would fall within categories 4 and 6 as every island household in Scotland is more than a half hour's drive away from a town of more than 10,000 people.10

In a further update to the Committee, Professor Hirsch, stated that, if a rural MIS were created, the appropriate terminology should be "remote towns and remote rural areas" rather than just "remote rural areas".11

Argyll and Bute Council's Alasdair Calder said that the Bill failed to adequately address the rural dimension. He proposed-

We could look at developing a Scottish minimum income standard with a rural element. Alternatively, if the way forward is to continue to use the UK-wide MIS, I suggest that we consider having, instead of a 90 per cent measurement against fuel poverty to account for rural areas, a 110 or 120 per cent measurement to take account of areas where there are higher energy costs for things such as oil and electric heating. I do not believe that that would substantially change the position for folk who heat their homes using gas, which is substantially cheaper. That might be a way of capturing the rural issue.12

The Minister for Local Government, Housing and Planning told the Committee that he had considered this evidence from Mr Calder and that-

... I will look seriously at that suggestion and consider how such an uplift can be best achieved for remote rural areas.13

He added, however, that-

... first of all, we have to find out exactly what difference having that standard would make. Would it make any difference? Obviously, if it was thought that it would make a difference, the likelihood is that there would be amendments lodged recognising that those differences exist.14