Local Government and Communities Committee

Stage 1 Report on the Planning (Scotland) Bill

Report Recommendations

The Scottish Government review of planning

We acknowledge the range of approaches and timescales over which the Scottish Government has consulted on its proposals for inclusion within the Planning (Scotland) Bill.

The purpose of planning

The planning system is uniquely placed to deliver a wide range of public benefits including a high quality environment, social development, cultural and artistic opportunities, connectivity and economic prosperity. We consider that it is important to have a clear and shared view of what the planning system is designed to achieve.

Since 1947, the purpose of planning has simply been (as reflected in the long title of the Bill), to make provision about how land is developed and used. The purpose to which land is developed and used has been left to policy and practice. It is well understood now, however, that the planning system is central to delivering not only outputs such as high quality environment, warm and secure homes and national infrastructure but also to helping fulfil climate change obligations, sustainable development goals, and wider human rights.

We note that by stating a purpose to planning there is a risk that it is so all-encompassing that it is ends up saying nothing at all. However, we are aware of examples from the Netherlands, Finland, Denmark and Germany where such a purpose has been effectively and succinctly articulated to provide an over-arching purpose of what a planning system should be seeking to achieve.

We also consider that a clear vision of what planning is to achieve will provide greater certainty to communities and developers supporting more meaningful engagement on planning applications, local place plans and local development plans.

We therefore recommend that a purpose of planning is included within the Bill. Such a purpose should reflect the ambition to create high quality places, to protect and enhance the environment, to meet human rights to housing, health and livelihoods, to create economic prosperity and to meet Scotland’s climate change goals and international obligations.

Part 1: Development Planning

The National Planning Framework

The proposal to incorporate Scottish Planning Policy (SPP) into the National Planning Framework (NPF) is, on balance, a sensible idea and puts the SPP onto a statutory footing. We note, however, that there is no explicit statutory reference to the SPP in the Bill[i] and the intention to merge the two documents could be made more explicit.

[i] We note that Section 1(2) of the Bill would expand the scope of the NPF to allow future versions of the NPF to include policies and proposals for the development and use of land.

The Bill provides that the new NPF would become part of the development plan for each planning authority, along with the Local Development Plan. This substantially increases the status of the NPF and concerns have been expressed that this creates greater central control and influence in the planning system.

The move to a 10 year cycle for reviewing the NPF better accords with development timescales, reducing the amount of time spent on preparing plans. It also means, however, that there is an increased likelihood of significant reviews needing to be made to reflect emerging policy issues and challenges.

We welcome the steps taken by the Scottish Government in this Bill to increase the time available for Parliament to scrutinise this Bill. Given the enhanced role to be accorded to the NPF, however, the Committee takes the view that the process of Parliamentary scrutiny must be significantly enhanced to include time for substantive engagement with the public. Provision for such enhanced scrutiny should be incorporated in the Bill and amendments brought forward to—

- require Parliament to be consulted on changes to the NPF

- remove limits to the timescales for Parliamentary scrutiny of the draft NPF (and any revisions) and give Parliament the power to establish such timescales as appropriate to the scope of the proposals according to normal Parliamentary business planning procedures

- require the draft NPF to be accompanied by a statement as to the process of engagement and consultation undertaken by Scottish Ministers in preparing the draft NPF as well as information on the impacts on equalities, human rights, children and young people, island communities and sustainable development (reflecting current reporting requirements for Scottish Parliament Bills)

- ensure that the final NPF reflects the views of Parliament as a whole rather than Scottish Ministers and has the standing to endure across successive governments. We recommend that the Scottish Government amends the Bill to enable the final NPF laid in Parliament to be amended by Parliament and, following any agreed changes, for the final NPF to be subject to Parliamentary approval.

We welcome the Scottish Government's commitment to bring forward amendments to the Bill at Stage 2 "to place procedures for significant amendments to the NPF on the face of the Bill" and its consideration of how to make appropriate arrangements for minor amendments. [35]

We request further information on how the Scottish Government will ensure that the NPF has "clear read across to funding arrangements".

Subject to the above amendments being brought forward we are content with the proposals to strengthen the NPF.

Finally, we suggest that the NPF should provide an opportunity to create greater coherence between a range of national policy areas such as climate change, energy, marine planning and transport. We recommend that Scottish Ministers consider how such greater coherence might be established within the NPF and be reflected in the Bill.

Removal of Strategic Development Plans

It is fair to say that views are mixed on the proposal to remove the statutory provisions relating to Strategic Development Plans (SDPs). To the extent that there is support, it is contingent on a commitment to continue with some form of regional spatial planning because, as one witness put it, “people and the natural environment do not obey strict political boundaries.”

We note that there are significant concerns about the future of regional spatial planning, a discipline that has a long history in Scotland and has attracted interest and commendation from elsewhere. A number of the planning authorities that comprise Clydeplan wrote of their positive experience and the valuable contribution that regional planning had made to "the successful delivery of regeneration and economic growth in the Glasgow city region in recent years."

It was not clear from the evidence we heard that removing the current provisions for SDPs will lead to a simplification, to streamlining, to cost savings or to more effective planning at a regional scale. There is a risk that the time and effort currently devoted to the four SDPs will be eroded and political support will wane if regional planning becomes a voluntary endeavour.

Given this, we do not consider that the current statutory framework for regional planning should be repealed unless a more robust mechanism is provided to that currently proposed in the Bill.

We suggest that such a mechanism could include enabling local authorities to work together for strategic planning purposes; and that any agreed plan that arises from that work should then form part of the relevant Local Development Plans (LDPs).

Local Development Plans

In considering the changes to local development plans we are content with the proposals to move to a 10 year cycle (which accords with the NPF cycle). We welcome the proposals to provide for greater connection between the LDP and local outcome improvement plans which should provide for a more coherent vision for communities.

We note the concerns expressed that the savings identified from the LDP and NPF moving to a 10 year cycle could be "unrealistic" and we therefore recommend that the Scottish Government and COSLA monitors and report on the costs of LDP and NPF plan preparation (should the Bill become an Act) to confirm that such savings do then materialise.

The requirement for planning authorities to review LDPs, in order to address newly emerging issues (or as a consequence of NPF reviews), may also give rise to additional costs. Our recommendations for enhanced Parliamentary scrutiny should ensure that NPF reviews (with their consequent impact on LDPs) are only undertaken when necessary and following robust consultation and engagement.

We remain to be convinced that removing statutory supplementary guidance will simplify LDPs and improve scrutiny and accessibility to any great extent. The removal of such guidance through the Bill could lead to increasingly complex and lengthy LDPs, as authorities include detail that would have previously formed supplementary guidance in the plan itself. This goes against the aims of streamlining plan making processes and producing concise, easily understood plans.

The removal of statutory supplementary guidance may also result in greater use of local guidance which, without statutory weight, could result in more confusion for developers and communities about the types and nature of developments that are permissible locally.

We therefore seek further clarification from the Scottish Government on how matters which were previously the subject to statutory supplementary guidance should now be articulated and given sufficient weight to ensure development is in accordance with an authority’s plans.

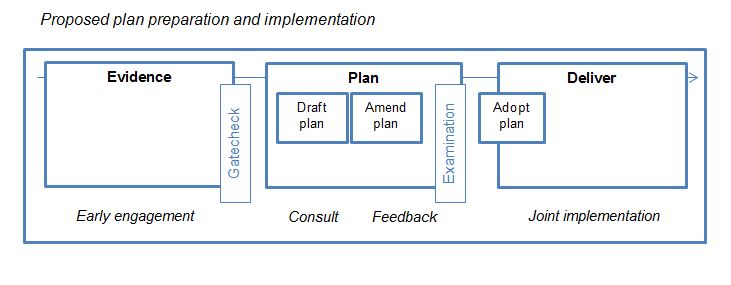

We agree with witnesses that removing the main issues report could reduce the opportunities for engagement with stakeholders and communities. We consider however that the new evidence report and gatecheck provides a mechanism to address these concerns. We welcome the Minister's commitment to consider amendments at stage 2 to provide for greater community engagement for development planning.

We recommend that those amendments should seek to ensure that evidence reports from authorities set out the quality and impact of their engagement with communities and stakeholders and in particular their engagement with disadvantaged communities.

We also consider that the gatecheck mechanism should provide for greater involvement with stakeholders so that their views are gathered by the Reporter as evidence on the robustness of evidence underpining the draft LDP. We recommend that regulations provide for this requirement.

We also note the calls for greater innovation on how views are gathered to inform LDP preparation and the gatecheck mechanism, including from public hearings and more deliberative approaches. We request further information from the Scottish Government on how it will encourage these and other more meaningful engagement approaches.

Later in this report we also make further recommendations about other aspects of the evidence report and gatecheck which should be amended in the Bill (see the section on Local Place Plans).

Local Place Plans

Local Place Plans (LPPs) will provide a statutory role for communities to bring forward plans that reflect their aspirations for the future of the places they live in. LPPs are not, however, a replacement for high quality, meaningful community engagement on the local development plan nor does this Bill propose that they should be. We therefore welcome the Minister's confirmation that—

As part of the wider planning review, we will bring forward proposals to ensure that planning authorities consult more widely on their development plans, including with children and young people. (Local Government and Communities Committee 21 March 2018, Kevin Stewart, contrib. 92 [95])

We also welcome the Scottish Government's commitment to amend the Bill to ensure that authorities must 'take account of' LPPs, placing them on a par with the status currently afforded to the NPF. It remains the case, however, that if minded to an authority can chose not to take account of any LPP it receives. As currently framed there is a risk that communities spend considerable time and effort on an exercise which may or may not be taken any account of by the planning authority.

Whilst we acknowledge the funding identified by the Minister to support capacity building and to fund the preparation of LPPs, we are not convinced that this will be sufficient to deliver the number of plans envisaged in the Financial Memorandum (92 per year). We remain to be persuaded that the resources that are necessary to support the delivery of LPPs are best expended on a process that might lead to no meaningful outcome for communities.

We are concerned that the powers available to create LPPs will disproportionately be taken up by communities with the capacity, time and resources to devote to preparing plans. More disadvantaged communities who stand to gain most from an effective, accountable and participatory planning system, by contrast, will be considerably less likely to take advantage of the opportunities due to a comparative lack of capacity, time and resources. This will widen inequality.

We welcome the statutory underpinning of LPPs as proposed in the Bill. However, what is unclear is the extent to which that statutory underpinning will mean that the time, effort and resources required to produce LPPs will result in them playing a "positive role in delivering development requirements" as originally envisaged by the Independent Review Group.

As things stand the proposals for LPPs run the risk of being disregarded or ineffective. The Committee firmly believes that communities should be supported to help develop plans for their areas. We suggest that councils, at the start of the Local Development Plan process, should put out a call for people to help them develop local place plans and show how this has been done in the Evidence Report. Once the LDP is in place then we are content that communities can bring forward their own plans that councils should take account of, providing communities are adequately supported to do so.

Equalities and planning

Whilst we welcome the Minister's offer to meet with ENGENDER to discuss their concerns, we request that the Minister respond to us before the Stage 1 debate on:

the specific "limited evidence" available that informed its views on the impact of the Bill on gender, sexual orientation and gender reassignment

the views it received (and that were echoed in our event in Skye) that access panels (or similar representative body) should become statutory consultees as identified within its EQIA

what specific evidence, broken down by protected characteristic, led it to conclude that "the overall Bill provisions will have a positive impact on equalities issues."

Third party/equal right of appeal

Whether rights of appeal in the planning system should be equalised has been a long standing issue on which a wide range of individuals and organisations hold passionate views either for or against. The reasons cited as supporting ERA or for not supporting it are well established as are the views as to whether those reasons are evidence based or robust.

The evidence we heard on ERA very much replicated this long standing debate about whether ERA would:

lead to a more robust, plan-led system which encouraged more meaningful up front engagement and agreement between communities, developers and authorities on what development should take place in local areas; or

lead to delays, uncertainty, reduce early engagement and investment in the housing and developments necessary to support people to live and work in their local area.

It is clear to the Committee that many communities feel frustrated by the planning system. Previous attempts to front-load the system have not been successful. The Committee is not persuaded that proposals in this Bill go far enough to address that. There is an imbalance in a system whereby the applicant can appeal decisions that have been taken in clear accordance with the development plan.

The Committee is conscious that the availability of appeals to applicants undermines confidence in a plan-led system. Appeals can be lodged free of charge and irrespective of whether an application is in accordance with the Development Plan. The Committee believes that in a plan-led system appeals should only be allowed in certain circumstances.

The Committee has heard evidence from both sides of the argument in relation to equal rights of appeal. We want people to feel involved in the planning system at all stages and we urge the Scottish Government to look at these issues before Stage 2.

Agent of change

Music venues make an important contribution to the cultural life and economy of Scotland. We agree that it is, therefore, unreasonable for those moving into a new development to lodge complaints about pre-existing noise levels that can ultimately result in the closure of such businesses.

We therefore welcome the Scottish Government's commitment to include the agent of change principle in the next National Planning Framework and that in the meantime the Scottish Government's Chief Planner has provided guidance to planning authorities asking them to ensure decisions reflect this principle.

That said, we note that the Chief Planner's letter to Planning Authorities suggests that current Planning Advice Note (PAN) 1/2011: Planning and Noise addresses this issue to some extent. Given that this existing advice required reinforcement by the Chief Planner, we question whether guidance alone or inclusion within the NPF will sufficiently safeguard this principle from subsequent changes in guidance or policy.

We also note that the advice in the Chief Planner's letter relates the agent of change principle to music venues, rather than other sources of existing noise such as those we heard about in evidence (e.g. sports venues, theatres).We recommend therefore that the Agent of Change principle should be applied more widely to, for example, theatres.

Given these concerns, we recommend that the Agent of Change principle be included within the Bill.

We also recommend that the Scottish Government considers widening the statutory consultees on planning applications to include an appropriate representative body of music venues (as already exists in relation to the Theatres Trust).

We also seek further information from the Scottish Government on whether:

the definition of cultural spaces should be amended to include grass-roots Music Venues;

a designation of "areas of cultural significance" should be created to provide greater protection to areas where creative industries, including music venues, have collectively created a cultural hub.

Part 2: Simplified Development plans

Simplified Development Zones (SDZs) in the context of a plan-led system could potentially make a positive contribution to place-making or delivering infrastructure. In considering the mixed views on the value of introducing SDZs we note that their predecessor - Simplified Planning Zones (SPZs) - have not met with much success since their introduction. Whilst we recognise SDZs are an improvement, providing greater flexibility and incentives for development to take place where it is needed, we remain to be convinced that they will lead to a sea change in proactive purposeful development.

We agree with witnesses that SDZs represent a "discretionary tool in the tool box authorities may use" if they consider it appropriate. As such we are supportive of their inclusion within the Bill. We would, however, wish to see some changes made in order to ensure that they more closely align with the proposals in the Bill to ensure meaningful engagement is undertaken early on.

We consider that, as part of the regulation making powers, proposals for SDZs should require to be included within the NPF or LDP to ensure that they are fully consulted on and form part of a wider plan for the area.

SDZs could play an important role in master planning and redevelopment, but we believe that only Scottish Ministers and planning authorities should have a statutory right to bring forward proposals for an SDZ.

We welcome the Minister's commitment to amend the Bill at Stage 2 to identify the types of land that may not be included in an SDZ scheme, with a power included to add or remove entries by regulations subject to the affirmative procedure. We also welcome the Scottish Government's commitment, in its letter dated 25 April 2018, to bring forward amendments to clarify its intention regarding advertising consent in SDZs and to remove the reference to disapplying regulations.

Part 3: Development Management

The evidence we received on the changes to pre-application consultation, delegation of decisions, the duration of planning permission and completion notices (Part 3 of the Bill) was broadly supportive. Overall the changes proposed seek to strengthen engagement through pre-application consultation, seek to have more decisions taken at an appropriate level and provide greater certainty to communities and developers that when planning permission is granted it leads to delivery on the ground in a timeous fashion.

As such we are broadly content with Part 3 of the Bill although we seek further clarification from the Scottish Government of whether those who lose permission for incomplete works will have a duty to restore the land to its original state, which will provide further encouragement to deliver the development on time.

We recognise that planning authorities currently can "decline to determine" repeat applications in some circumstances. We recommend, however, that the Scottish Government should further limit or deter repeat applications which have been previously refused and where there has been no significant change in that application. We call on the Scottish Government to bring forward amendments to the Bill to give effect to this recommendation.

We also recommend that the Scottish Government should limit or deter the ability of applicants to proceed with multiple appeals for the same site and should amend the Bill accordingly.

Part 4: Other matters

Fees

We welcome the provisions in the Bill that, subject to further regulations, may in time permit planning authorities to move to full cost recovery for development management. We note that the Scottish Government will consult on how the powers relating to fees will be used. As the Bill seeks an enabling power, we are limited in the extent that we can comment on the detail of the level and type of fees which authorities and the Scottish Government will be able to charge and their resulting impact on applicants and on the resources of planning authorities.

In relation to the provisions which would enable the Scottish Government to charge others for its services, we request clarification of what services would fall within "facilitates, is conductive or incidental to the performance of those planning functions".

We welcome the Scottish Government commitment that, in responding to the Delegated Powers and Law Reform (DPLR) Committee recommendations, it will bring forward amendments to provide for Scottish Ministers to have a power to waive or reduce a fee that they charge.

We note that in its response to the DPLR Committee report the Scottish Government does not consider there should be additional restriction and greater scrutiny of the surcharge provisions in section 21 of the Bill but that it would consider this recommendation further. We therefore seek confirmation of the outcome of the Scottish Government's deliberations on this matter.

We request a timetable from the Scottish Government of when it anticipates bringing forward the final fees structure.

Performance of planning authorities

We note that planning authorities have for a number of years voluntarily reported on their planning performance. We received no evidence that this approach has been flawed.

Indeed as COSLA explained in its written evidence "The decision by Scottish Government to legislate on reporting came as a surprise" and that it was "not expecting" the inclusion of the national planning performance co-ordinator in the Bill as discussions with the Scottish Government were ongoing. COSLA comment that "It is the proposals on assessment which give us most concern. As far as we are aware, the appointment of an assessor for local government performance has never recently been discussed."

The Committee sees no need or justification for the Bill's proposals on performance and recommends that section 26 of the Bill be removed. We consider that the Scottish Government should continue to work collaboratively with COSLA.

There is scope, however, to further enhance the measures reported on by the current Planning Performance Framework and we recommend that the Scottish Government, COSLA and HOPS consider whether to include measures on:

the quality of support and engagement with communities by planning authorities (given it is a key purpose for this Bill)

aspects of the entire planning system and not just those aspects under the control of the planning authority (this will give a more balanced view of what influences planning outcomes)

stakeholder satisfaction

the quality of planning outcomes and

recognition of the different planning environments and focus of planning authorities.

We also request a copy of the Ironside Farrar report on the reasons for delay in planning applications in housing at the time it is provided to the Scottish Government (end of May 2018) in order to inform our Stage 2 consideration of the Bill (should the Bill be agreed at Stage 1).

Enforcement

We are content with the enhanced enforcement provisions in the Bill as a potential deterrent mechanism. However, it will only be effective if planning authorities have the resources to pursue such actions. Not withstanding the proposals in the Bill for increases in the maximum fines that can be imposed by a court for breaches of planning control and for the pursuit of legal expenses associated with enforcement action, the Committee is concerned that there is insufficient investment in the planning service within planning authorities. This has implications for enforcement as lack of resources (including access to appropriate legal advice) could stop planning authorities pursuing enforcement action when it is in the public interest. Another consequence of this is that people's trust in the planning system is also undermined as they see applicants not penalised for failing to adhere to planning conditions.

We therefore request that the Scottish Government ensure planning authorities are properly resourced to take enforcement action. We also seek clarification of who retains any fines that planning authorities secure as a result of enforcement action.

Training for taking planning decisions

We agree that in undertaking their functions on a Planning Committee it is important that Councillors are clear about the matters upon which they should base their decisions. We consider therefore that Councillors should attend training on key aspects of the planning system. We do not agree, however, that it should be mandatory and accordingly we recommend that the Scottish Government amends the Bill to remove this provision.

We consider any training in planning should be considered as part of a continuous professional development programme for Councillors. We invite COSLA and the Improvement Service to consider broadening the range of training available to Councillors on planning to include—

best practice in community engagement in planning

equalities and human rights duties

challenges in urban and rural settings

environmental and sustainability duties

If the amendments we recommend are not made then we consider that all decision- takers in planning should be subject to the same training requirements. This includes all relevant Councillors and Scottish Ministers.

Tree Preservation Orders

We seek the Scottish Government's views on the concerns raised with us on the protection of trees in conservation areas and on whether it proposes to amend the Bill to address the concerns raised in written evidence.

Part 5: Infrastructure levy

As we heard the infrastructure levy as proposed will not be a "game changer that will fundamentally alter and remove blockages from the system." We agree and consider that, if it is introduced, it will likely be more effective in some circumstances and in some places than others. This is because of differences in the volume and nature of development and the potential impact of the infrastructure levy on the financial viability of developments.

As such, we agree with HOPS that—

it is another tool in the box and it is useful to have it, although we expect to have another two rounds of research before we start to think about using it again. I hope that it works, but it has a long way to go yet. (Local Government and Communities Committee 14 March 2018 [Draft], Robert Gray, contrib. 348 [177])

That said, we note the Scottish Government's statement that "no decisions have yet been made on the use of this power". Given this, plus the evidence we received that greater clarity is required as to how the Infrastructure Levy will work and the Minister's own comments that more work is needed before it can be used, we agree with the DPLR Committee that the powers in schedule 1 should be subject to the super-affirmative power. This high level scrutiny approach should ensure that the draft regulations are more likely to come forward as package which can be scrutinised and consulted on in more detail by Parliament and at a much earlier stage than an affirmative SSI procedure affords.

The Committee also seeks further information on the timetable for conducting the further work on the Infrastructure Levy and a commitment that the necessary draft regulations will all be laid in Parliament at the same time (to facilitate more meaningful scrutiny).

Finally, we remain concerned about the powers in the Bill that enable Scottish Ministers to collect and redistribute all the levy funds to local authorities as they wish. This wider redistribution power seems counter to the Scottish Government's intention, as set out in the Policy Memorandum, for the levy to be "both collected and spent locally, with the potential for authorities to pool resources for joint-funding of regional-level projects." We support the principle that money raised locally should be spent locally and therefore request that the Minister sets out the reasons why this power is necessary and the circumstances when it would be used.

Land Value Capture

We have some sympathy with those we heard from who are disappointed that the Bill proposes an infrastructure levy, when other potentially more effective approaches to funding infrastructure are being actively considered by the Scottish Government and others.

We note the Minister's explanation that the Scottish Government has not yet consulted on these other approaches and recommend that this work is taken forward quickly. We request clarification from the Minister of the timetable and key milestones for completing this work.

The balance between national and local decision taking

Whether or not the Bill appropriately balances decision taking at national or local level will depend upon how often, why, when and by whom its powers are then used. We have commented throughout our report on those circumstances where we consider the balance of decision making is appropriate (or not).

We welcome the Scottish Government's commitment to amend the Bill at Stage 2 to ensure that all directions issued as a consequence of this Bill and the Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997 are published.

We recommend, however, that the Scottish Government ensures those directions are provided to the Scottish Parliament at the time of issue to support greater transparency and scrutiny by MSPs of the circumstances when National Government directs Local Government to act in a specific way. Given the Minister's assurances that these powers would not be frequently used (such as his comments in relation to imposing SDZs) this requirement should not be unduly burdensome on the Scottish Government.

Regulation making powers

We note the concerns that a number of the enabling powers sought in this Bill mean that it is not yet clear how (or in the case of the Infrastructure Levy, if) those powers will be used. It is not good legislative practice for powers to be granted only for them to either lie on the statute books unused or for subsequent governments to seek to use them many years later, potentially in ways not originally envisaged.

Throughout our report we have referenced the technical paper provided by the Scottish Government which describes its "current thinking" on how some of the powers it seeks in this Bill will then be used. The Technical Paper is not, however, a guarantee that powers will be used in the way it specifies.

Whilst we note that in many areas of the Bill subsequent regulations will enable the Parliament to accept or reject the detail of the proposals, we remain concerned that the Infrastructure Levy provisions may never be enacted - given the work required before Ministers decide whether to use this power, as well as the work underway on other approaches. We therefore invite the Scottish Government to consider amending the Bill to provide a sunset clause for part 5 of the Bill, so that if the power is not enacted within an appropriate period of time (such as 10 years) then it lapses.

Conclusion

The Committee recommends that Parliament agrees the general principles of the Bill.

Introduction

The Scottish Government introduced the Planning (Scotland) Bill on 4 December 2017. In the Policy Memorandum to the Bill, the Scottish Government explains that the Bill's provisions "will improve the system of development planning, give people a greater say in the future of their places and support delivery of planned developments".1

The Bill aims to update aspects of the Scottish town planning system, by amending legislation that governs the operation of the system - the Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997.

As we learned during our scrutiny, planning has its own terminology some of which is not used in everyday discussions. Annexe A therefore contains a glossary of the most commonly used terms, and acronyms, in this report.

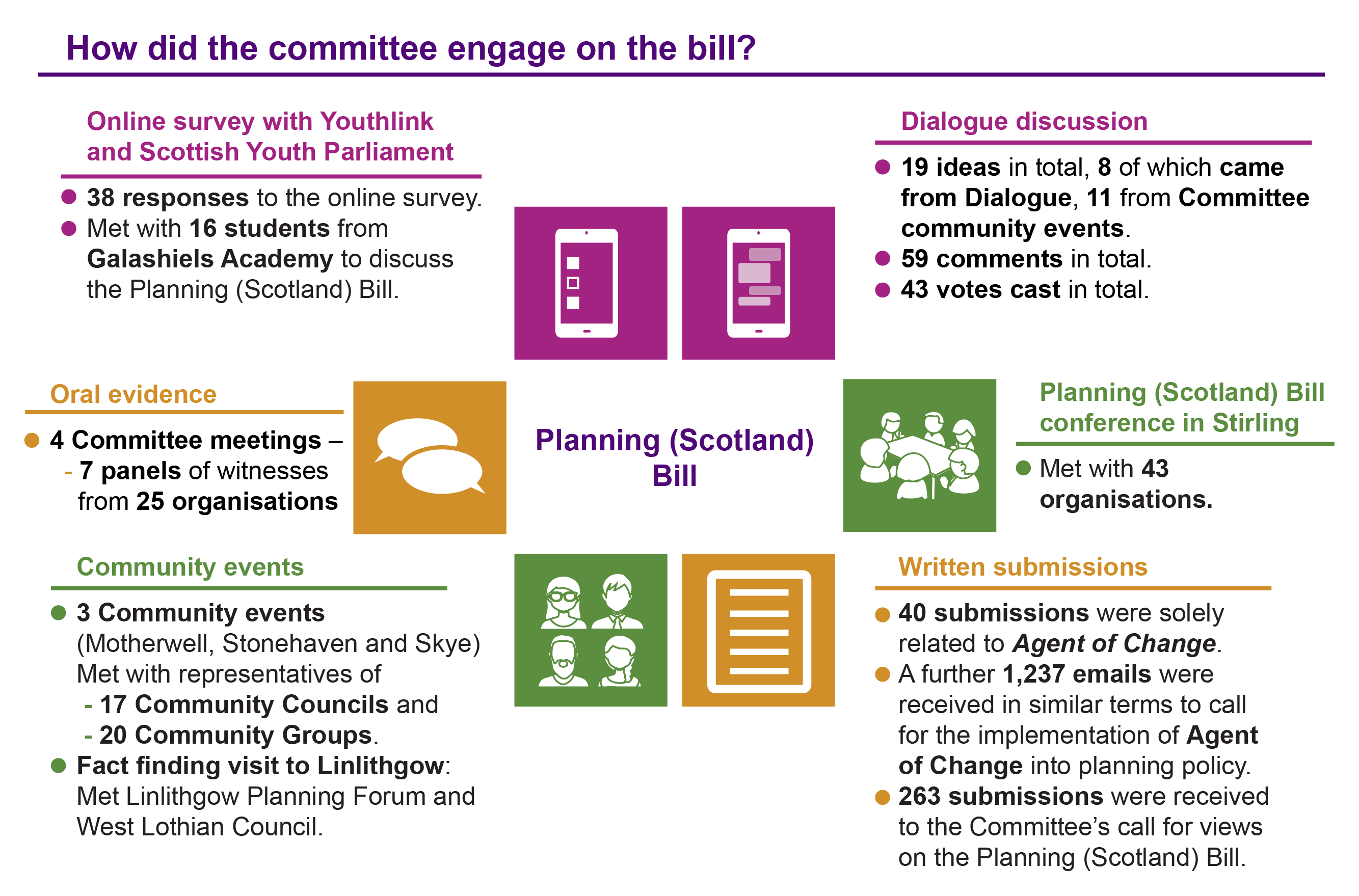

Approach

At its meeting on 13 December 2017 the Committee agreed its approach to Stage 1 scrutiny of the Bill. Mindful of the high level of interest in the Bill the Committee agreed a multifaceted approach to seeking views on the Bill including:

Issuing a call for written views

Holding community events in Motherwell, Skye and Stonehaven

Holding a conference for public, private and third sector organisations

Piloting the use of Dialogue (an online discussion forum)

An online survey of young people's views principally promoted within the Scottish Youth Parliament and Youthlink as well as meeting with students from Galashiels Academy

Meeting with Linlithgow Planning Forum and West Lothian Council officers to discuss their experience of local place planning

Seeking oral evidence at Committee meetings

The Committee received a great response from individuals, small and large organisations (voluntary, charitable, public and private, businesses and others). We thank them for the time and effort taken to provide us with their views which have enhanced our scrutiny and this report.

All of the evidence we have considered can be found on our webpage including the names of all those who have contributed to our work (a summary of which is also contained in Annexe B). Figure 1 below provides details of the Committee's engagement 'in numbers'. Also important to the Committee, however, was the good quality of these contributions.

This report sets out our views, conclusions and recommendations at Stage 1 of the Planning (Scotland) Bill.

The Finance and Constitution Committee and the Delegated Powers and Law Reform (DPLR) Committee also provided their views and recommendations to us. We thank them for their contributions and have included their views and recommendations throughout this report as appropriate.

The Scottish Government's review of planning

In April 2015, the Scottish Government began its review of the Scottish planning system with the appointment of an independent review panel, chaired by Crawford Beveridge (chair of the Scottish Government’s Council of Economic Advisors), working with Petra Biberbach of Planning Aid Scotland (PAS) and John Hamilton of the Scottish Property Federation.

The independent review panel published its final report entitled Empowering planning to deliver great places in May 2016. The Scottish Government responded to that report in July 2016 before then undertaking further consultation, including through six working groups.

In January 2017, the Scottish Government published a consultation paper, Places, People and Planning which set out 20 proposals under four key areas of change. Following further consultation and engagement, the Scottish Government published an analysis report in June 2017 alongside its Position Statement. Alongside that position statement, the Scottish Government published a Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) Environmental Report on the environmental impact of those proposals.

The Scottish Government then consulted further on its position statement, and published a further report in October 2017 following analysis of those responses. In December 2017, the Scottish Government published "Review of the Scottish Planning System: Technical Paper" (hereafter referred to as the 'technical paper') which set out its "current thinking" on how key aspects of the Bill could work in practice.

We acknowledge the range of approaches and timescales over which the Scottish Government has consulted on its proposals for inclusion within the Planning (Scotland) Bill.

The purpose of planning

The Scottish Planning Policy (SPP) 2014, which sets out national planning policies which reflect Scottish Ministers’ priorities for operation of the planning system and for the development and use of land, states that—

NPF3 and this SPP share a single vision for the planning system in Scotland:

We live in a Scotland with a growing, low-carbon economy with progressively narrowing disparities in well-being and opportunity. It is growth that can be achieved whilst reducing emissions and which respects the quality of environment, place and life which makes our country so special. It is growth which increases solidarity – reducing inequalities between our regions. We live in sustainable, well-designed places and homes which meet our needs. We enjoy excellent transport and digital connections, internally and with the rest of the world.

The National Planning Framework (NPF) sets the context for development planning in Scotland and provides a framework for the spatial development of Scotland as a whole. It states that—

Key Planning outcomes for Scotland

- A successful sustainable place – supporting economic growth, regeneration and the creation of well-designed places

- A low carbon place – reducing our carbon emissions and adapting to climate change

- A natural resilient place – helping to protect and enhance our natural cultural assets and facilitating their sustainable use

- A connected place – supporting better transport and digital connectivity

Section 3D of the Town and Country Planning (Scotland) 1997 Act requires that functions relating to the preparation of the National Planning Framework by Scottish Ministers and development plans by planning authorities must be exercised with the objective of contributing to sustainable development.

The Scottish Planning system currently has no specific purpose established in legislation. We heard that when the planning system was introduced in 1947 it was assumed that there was a common purpose so it was never included in the legislation. There were calls for a statutory purpose for the planning system to be included within the Planning etc. (Scotland) Act 2006 (hereafter referred to as "the 2006 Act") which the then Scottish Government explained would "...be too great a risk to introduce a provision in relation to individual planning applications, as it would be too difficult to determine with legal certainty, where or not the developments were sustainable."1

As we heard these calls have not diminished since the 2006 Act with a number of respondees again calling for a statutory purpose for planning to be included within the Bill. We heard of examples of other jurisdictions where a purpose for planning had been included within their planning legislation. As Professor Hague explained—

What is the alternative to having a purpose? There are presumably two possibilities. One is that there is no purpose, in which case why are we doing it? The other is that there is a purpose but we are not prepared to say what it is, and that is not a great piece of administration.

Local Government and Communities Committee 07 March 2018, Professor Hague, contrib. 204, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11405&c=2070891

Some recommended that the purpose should reflect environmental and climate change priorities to ensure that planning supported the delivery of these Scottish Government commitments. The John Muir Trust stated—

The Trust believes there should be a Purpose for Planning Statement within the Bill, identifying the overarching aims of the planning policy and process. That Purpose should explain how the process will achieve protection and enhancement of the natural and cultural environment.3

Others such as Community Land Scotland, PAS and Planning Democracy proposed that providing a statutory purpose of planning could shift the perception of planning from a regulatory function to providing more positive engagement, creating better local places. Planning Democracy explained that—

A statutory purpose for planning would provide clarity about the public interest outcomes the system should both work towards and be assessed against, moving away from process-dominated debates about planning being a regulatory burden towards a positive focus on creating high quality places.4

Professor Hague highlighted examples from South Africa and Zambia where a purpose for planning had been included within legislation. The National Trust for Scotland also provided extracts of legislation from Denmark (Planning Act 2007), Finland (Land Use and Building Act 2003), Germany (Federal Planning Act 2009), France (Code of Urbanism 2018), Norway (Building and Planning Act 2005) and—

Netherlands - Environment and Planning Act, 2016

Article 1.3 (objectives of the Act in relation to society)

With a view to ensuring sustainable development, the habitability of the country and the protection and improvement of the living environment, this Act aims to achieve the following interrelated objectives:

a. to achieve and maintain a safe and healthy physical environment and good environmental quality, and

b. to effectively manage, use and develop the physical environment in order to perform societal needs.5

A number of those we heard from called for a purpose for planning to be set out in the Bill to reflect the United Nation's Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDG). The Royal Incorporation of Architects in Scotland (RIAS) called for the purpose to—

…align the planning system with international obligations, specifically the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) which provide a global definitive statement on what sustainable development means and present a clear, unified message.6

Homes for Scotland, however, cautioned against the practicalities of including a purpose within the Bill to ensure that the current plan-led planning system retains flexibility and remains deliverable—

Trying to frame a purpose that describes all that without alienating people who perhaps do not want that to be the purpose of planning could be quite an endeavour.

Local Government and Communities Committee 07 March 2018, Tammy Swift-Adams, contrib. 181, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11405&c=2070868

Housing delivery was one of the six key themes Ministers asked the Independent Review panel to consider. It remains a key driver of the Scottish Government's planning reform agenda, featuring in the Minister for Local Government and Housing’s statement to Parliament on Planning and Inclusive Growth, on 5 December 2017. The Committee therefore explored the likelihood of the proposals in the Bill to meet the Government’s housing ambitions.

Several local authorities and others such as Architecture and Design Scotland, and Culter Community Council highlighted the fact that planning legislation, and the planning system more generally, is only one factor in housing delivery. Angus Council in its written submission summarised the range of factors highlighted to us asserting that—

…the planning system is not the primary factor for the lack of housing delivery in recent years. A range of factors have contributed to a reduction in house building activity, stemming largely from the impacts of the economic recession, continued restriction on development finance, lack of construction labour, reduction in the number of small and medium housebuilding and in some cases, the reluctance of landowners and developers to release land or commence development until local market conditions improve.8

Developers and housing stakeholders, such as Homes for Scotland, Scottish Federation of Housing Associations (SFHA) and the Federation of Master Builders Scotland, agreed that the Bill in itself won't deliver more homes. Some developers and housing providers, e.g. McCarthy and Stone, also argued that there needs to be stronger link between the range of housing needs that need to be met, e.g. housing for older people, and the planning process - allowing land to be specifically allocated in development plans for new housing to meet those needs. Similar calls for housing which better meets the needs of older people and those with additional access needs were also made at our community events such as in Skye.

Homes for Scotland explained that in relation to building more and better homes—

Success will be heavily reliant on the secondary legislation, guidance and updated national policy that will follow.9

Some house builders and developers were also keen to stress that delivering more homes was not really dependent on legislative or policy change – rather it would require a culture change towards development within policy and political circles. Stewart Milne Homes stated that—

We remain to be convinced that this Bill, or any variant of this Bill, in itself will result in an increase in housebuilding. Legislative changes through the Planning etc (Scotland) Act 2006 failed to deliver this and we are of the opinion that this Bill still will not deliver homes, unless there is a major change in the mindset of policy makers and decision takers including the Scottish Government and the Reporters’ Unit.10

Finally, a number of respondees highlighted what they see as fundamental problems with the operation of the current system of land purchase and house building, suggesting possible solutions based on experience elsewhere in Europe. The Centre for Progressive Capitalism considered that—

If the Scottish government wishes to increase the level of housebuilding then it will have to reform the land market to remove the speculative element of bidding for land at very high costs upfront. In our view this will require the 1963 Land Compensation Act (Scotland) to be amended to remove prospective planning permission from the compensation arrangements. It is this clause that generates the incentives to speculative in land given the potentially very high profits. Residential land in Edinburgh is estimated to be valued at around £3.2m [million] per hectare versus £800k[thousand] for industrial land and £18k [thousand] for agricultural land. Acquiring residential land at such high prices and which requires firms to manage the risk of these assets through the business cycle remains at the core of the issue. 11

We comment more fully on the proposals for a land value capture at the end of this report in relation to Part 5 of the Bill which seeks to provide Scottish Ministers with the power to introduce an infrastructure levy.

The Minister for Local Government and Housing (hereafter referred to as "the Minister") explained that although the planning system is not broken the need for planning reform came from a number of different sources including—

the need to deliver more housing, the need to improve the experience and influence of our communities, the effectiveness of development planning and leading positive change in our places, the need for more proactive management of development, and the need for strong leadership and better management of skills and resources.

Local Government and Communities Committee 21 March 2018, Kevin Stewart (Minister for Local Government and Housing), contrib. 2, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11441&c=2078002

The Minister confirmed that the Bill as only one part of that reform, although it has an important role to play in setting the framework for the system as a whole. It is—

certainly more than just tinkering—it will lead an essential shift in our planning services away from a largely regulatory function, and it will strip back unnecessary process to facilitate delivery of good-quality development and the great places that our communities deserve.

Local Government and Communities Committee 21 March 2018, Kevin Stewart (Minister for Local Government and Housing), contrib. 2, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11441&c=2078002

The Minister explained that the core purpose of planning was to create great places—

It is about ensuring that we serve Scotland’s communities, that we achieve sustainable economic growth and that we have the housing that we need and the jobs that we need for our economy to thrive.

Local Government and Communities Committee 21 March 2018, Kevin Stewart, contrib. 12, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11441&c=2078012

Whilst the Minister considered that the UN Sustainable Development Goals are a useful starting point for considering a purpose for planning, he observed that under the 2006 Act planning authorities already have a duty to contribute to sustainable development in the exercise of their development plan related functions. In that regard he considered that the UN Sustainable Development Goals and the purpose of planning would be more relevant in subsequent policy rather than in the Bill. 15

Given the different purposes people consider planning should support, the Minister considered that "reaching a definition and getting agreement on it is always going to be difficult." Scottish Government officials also highlighted that in setting out a purpose in the Bill—

it would have legal effect. If it were to have legal effect, it could be used—and people would want it to be used—to challenge decisions and alter how things are processed at all levels of the planning system. We would therefore need to be very clear that that purpose of planning was what we want it to be. It would be much harder to amend a purpose in legislation than to amend a purpose in a policy document.

Local Government and Communities Committee 21 March 2018, Norman Macleod (Scottish Government), contrib. 16, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11441&c=2078016

The Minister commented on the work of the Law Commission in Wales—

The Law Commission is currently undertaking a review of planning law in Wales, with a view to providing recommendations for consolidating and simplifying it. Its consideration of the appropriate section of the Planning (Wales) Act 2015 and the proposal on the need for a statutory purpose is set out in a detailed consultation paper that was issued in November last year. The commission suggests that setting out a purpose in law could cause unnecessary and unhelpful duplication as well as conflict.

The last thing that I, and others, want is conflict; a huge part of what we are embarking on is about trying to remove conflict from the system.

Local Government and Communities Committee 21 March 2018, Kevin Stewart, contrib. 18, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11441&c=2078018

The planning system is uniquely placed to deliver a wide range of public benefits including a high quality environment, social development, cultural and artistic opportunities, connectivity and economic prosperity. We consider that it is important to have a clear and shared view of what the planning system is designed to achieve.

Since 1947, the purpose of planning has simply been (as reflected in the long title of the Bill), to make provision about how land is developed and used. The purpose to which land is developed and used has been left to policy and practice. It is well understood now, however, that the planning system is central to delivering not only outputs such as high quality environment, warm and secure homes and national infrastructure but also to helping fulfil climate change obligations, sustainable development goals, and wider human rights.

We note that by stating a purpose to planning there is a risk that it is so all-encompassing that it is ends up saying nothing at all. However, we are aware of examples from the Netherlands, Finland, Denmark and Germany where such a purpose has been effectively and succinctly articulated to provide an over-arching purpose of what a planning system should be seeking to achieve.

We also consider that a clear vision of what planning is to achieve will provide greater certainty to communities and developers supporting more meaningful engagement on planning applications, local place plans and local development plans.

We therefore recommend that a purpose of planning is included within the Bill. Such a purpose should reflect the ambition to create high quality places, to protect and enhance the environment, to meet human rights to housing, health and livelihoods, to create economic prosperity and to meet Scotland’s climate change goals and international obligations.

Part 1: Development Planning

The National Planning Framework (NPF)

The National Planning Framework (NPF) sets out Scottish Ministers' long-term land use strategy for Scotland for the next 20-30 years. It is the spatial expression of the Government's Economic Strategy and infrastructure investment plan. The NPF also identifies national developments and other strategically important development opportunities in Scotland. The NPF is accompanied by an action programme which identifies how it should be implemented, by whom, and when. Statutory development plans must take account of the NPF, and Scottish Ministers expect planning decisions to support its delivery.

This Bill proposes that the NPF would be amended to include the content of the Scottish Planning Policy (SPP). The Scottish Government explains that-

the purpose of the SPP is to set out national planning policies which reflect Scottish Ministers’ priorities for operation of the planning system and for the development and use of land. The SPP promotes consistency in the application of policy across Scotland whilst allowing sufficient flexibility to reflect local circumstances. It directly relates to:

the preparation of development plans;

the design of development, from initial concept through to delivery; and

the determination of planning applications and appeals.1

The Bill also proposes that

the NPF would become part of the development plan for every area, alongside the local development plan (creating the 'statutory development plan' for each area);

the NPF would be reviewed every 10 years (currently every five years) with provision for amendments during that 10 years to be set out in future regulations; and

Parliamentary consideration of the NPF would be increased to 90 days (currently 60 days).

In its technical paper the Scottish Government confirms that NPF4 should be adopted in 2020 and that it will be aligned with the next Strategic Transport Projects Review. The approach taken with NPF3 will be built on, with extensive public engagement undertaken and that working with regional partnerships and local authorities will help achieve this. This paper also sets out the parameters for collaborative working, including that Ministers would be responsible for decisions on nationally significant issues and for the adoption of NPF but that they would be transparent about the grounds for deciding not to incorporate regional proposals. They also make clear that the NPF is not a spending document, but would take into account and be informed by wider Government policies and programmes and would therefore "have clear read across to funding arrangements". 2

In its policy memorandum the Scottish Government explains that-

the enhanced status of the NPF and SPP will play a key role in streamlining the planning process by removing the need for local development plans to restate national policy instead focussing on places and development delivery;

the move to a 10 year review of the NPF will provide for "greater stability and certainty as the future direction for growth, enabling investment choices by developers and infrastructure providers to be made with confidence."

in addition, the previous experience of parliamentary scrutiny of the NPF over 60 days has found it to be 'testing' hence the extension to 90 days for parliamentary consideration.

Content of the NPF

We heard that an enhanced NPF could provide a mechanism to set clear specific national house building targets.1 Whilst Scottish Environment LINK stressed that the NPF could provide "clear links across to other sectors of spatial planning in Scotland, particularly marine planning and agriculture, forestry and other areas of land use, through the land use strategy." 2

Scottish Water also supported some Scottish planning policies such as flooding being decided at a national level as this would allow LDPs to focus on more specific issues within an area. 3

Some witnesses, including Heads of Planning Scotland (HOPS) and Scottish Environment LINK, were supportive of a stronger NPF - particularly through its merger with the Scottish Planning Policy. However, they had concerns about how the proposals in the Bill might work in practice. Scottish Environment LINK summarised some of the concerns we heard from a range of organisations as follows—

We think that including Scottish planning policy in the national planning framework risks overloading it. At the moment, Scottish planning policy sets out different sorts of specific criteria-based policies, whereas the national planning framework is much more spatial... There is a risk of making the document quite heavy and burdensome.

The other disadvantage of including Scottish planning policy in the national planning framework is that it would mean that it is likely that there would be only one consultation on SPP and the NPF together, whereas, at the moment, they are consulted on separately, which gives communities and others an opportunity to get involved in thinking about what the criteria policies mean, separate from what the spatial strategy means. There is also, at the moment, an opportunity for an environmental assessment of those.

Local Government and Communities Committee 14 March 2018 [Draft], Aedán Smith (Scottish Environment LINK), contrib. 4, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11423&c=2074095

Clydeplan questioned whether the enhanced status of the NPF would require better budgetary alignment. They sought greater clarification on what information the Scottish Government would require from planning authorities, including regional collaborations, in drafting the next NPF. Professor Hague had concerns about the change in status of the NPF from a spatial strategy to a policy document, stating that this might—

restrict the capacity of the NPF to range widely and address matters that might fall outwith the scope of the statutory system at the moment—especially if we do not have a declared purpose of planning that takes on the points that we were talking about earlier this morning.

Local Government and Communities Committee 07 March 2018, Professor Hague, contrib. 310, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11405&c=2070997

The NPF and Local Development Plans

A number of local authorities expressed concerns about the Bill's proposals to make the NPF a formal part of each local development plan (LDP). As COSLA explained—

it is important that the planning process is kept under local democratic control. Given the move towards incorporating the regional aspirations within the national planning framework, sitting alongside the local aspirations in the local development plan, there is a risk that it could lead to more direction from above and so the withdrawal of local democratic control.

Local Government and Communities Committee 14 March 2018 [Draft], Councillor Heddle, contrib. 268, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11423&c=2074359

Local authorities were concerned that this change in the status of the NPF, along with other changes elsewhere in the Bill, centralised policy making powers. South Lanarkshire Council in its written evidence explained its concerns—

…that a number of the proposals may lead to the control of some planning matters pass from Councils to the Scottish Government. These include the preparation and approval [of] regional strategies through the National Planning Framework, the increased role of Scottish Planning Policy in setting policies formerly set out in Council approved LDPs; and the opportunity for Ministers to require Councils to prepare Simplified Development Zone schemes, and to direct how performance improvements are to be made by Councils. 2

We explore the balance between local and national accountability in the Bill in more detail later in this report.

City of Edinburgh Council also expressed some concerns about the impact of an enhanced NPF on LDPs—

Edinburgh, by its nature as the capital city, has a number of national interests in its development. The way in which we manage those developments should be left to the area’s planning authority to deal with in detail. It is important that the local experience is recognised when the national planning framework is prepared. It is a matter of how we input to that process.

Local Government and Communities Committee 14 March 2018 [Draft], David Leslie, contrib. 270, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11423&c=2074361

Parliamentary scrutiny of the NPF

Whilst some such as RTPI Scotland welcomed the enhanced status of the NPF, they considered that greater Parliamentary scrutiny was therefore necessary (additional to the proposed extension of the time for Parliamentary scrutiny from 60 to 90 days)—

In particular, we are exploring the possibility that the NPF could be subject to parliamentary approval. An alternative, or additional, form of scrutiny would be to require the minister to report on the NPF and its implementation perhaps annually or biennially.

Local Government and Communities Committee 07 March 2018, Kate Houghton, contrib. 305, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11405&c=2070992

The National Trust for Scotland also called for greater parliamentary scrutiny, particularly in relation to the national developments, stating "National Developments all happen in local places, so it is a concern if people are not aware of that the developments will impact on them." Scottish Environment LINK echoed the views of RTPI Scotland calling for the NPF to be owned and approved by Parliament especially given they consider that the Bill shifts the balance of decision-making "towards the Scottish Government and away from local levels."2

Graeme Purves of Built Environment Forum (BEF) Scotland, however, explained that in a previous role as a Scottish Government civil servant his experience of Parliamentary scrutiny by Committees and the Parliament was that it resulted in meaningful changes to NPF2—

On the process of parliamentary scrutiny, there is an important provision in the existing legislation that ministers are required to report back to Parliament on how they have taken account of the national planning framework, and that is not a perfunctory process...Significant changes were made to the second national planning framework in the light of the Parliament’s views. Two new national developments were added and a couple of others were adjusted.

Local Government and Communities Committee 14 March 2018 [Draft], Graeme Purves, contrib. 11, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11423&c=2074102

The Scottish Young Planners Network highlighted the challenges about the process for public consultation during the drafting of the NPF and also amending it during its proposed 10 year lifespan—

We have to be careful about the point at which we consider the national planning framework, particularly if it can be amended at any stage. Decisions made at that point might lead to a local development plan being incompatible with the national planning framework, given that whatever document is decided on will be the prevailing document. Consultation, particularly on the national planning framework, is important to ensure that there is a robust engagement process and that all opportunities for people to participate are taken.

Local Government and Communities Committee 14 March 2018 [Draft], Ailsa Anderson, contrib. 277, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11423&c=2074368

In the circumstances of changes to the NPF during the 10 year cycle the Bill provides that subsequent regulations will set out the process for revisions. Scottish Environment LINK called for those amendments to the NPF to go through the same procedures as the NPF in relation to strategic environmental assessment and approval by Parliament. 5

The DPLR Committee also expressed concerns about how changes to the NPF during its 10 year cycle might be considered by Parliament. It recommended that the Government amend the Bill so that significant amendments to the NPF that change the overall policy become subject to specific public and parliamentary consultation requirements set out in the Bill. On the basis that these amendments were made, it is content that the negative procedure applies to setting the procedure for minor amendments to the NPF. However, its preference would be that any provision for periodic parliamentary consideration of such minor issues was set out on the face of the Bill.6

The Minister explained that one of the reasons for the NPF becoming part of the statutory development plan is to reduce duplication, as policies won't require to be repeated in each LDP (unless they depart from the NPF). In addition—

We also intend to use the NPF to provide greater clarity in requirements for housing land, to reduce some of the conflict in the system. Development plan status will help in that regard. Instead of working as they do in the current situation, local development plans will be able to focus on achieving outcomes in places where future development should actually happen. We believe that, by reducing duplication, that could significantly reduce the amount of time that people in organisations have to spend contributing to development plans.

Local Government and Communities Committee 21 March 2018, Kevin Stewart, contrib. 138, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11441&c=2078138

Commenting on parliamentary scrutiny, the Minister confirmed that he was considering the recommendations for amendments called for by the DPLR Committee. The Minister highlighted that Committee recommendations arising from NPF3 were already being considered as part of NPF 4, which is due in 2020—

For example, the report on NPF3 asked that we build into the process early debate by Parliament on the national developments. That would be extremely helpful.

Local Government and Communities Committee 21 March 2018, Kevin Stewart, contrib. 142, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11441&c=2078142

The proposal to incorporate Scottish Planning Policy (SPP) into the National Planning Framework (NPF) is, on balance, a sensible idea and puts the SPP onto a statutory footing. We note, however, that there is no explicit statutory reference to the SPP in the Billi and the intention to merge the two documents could be made more explicit.

The Bill provides that the new NPF would become part of the development plan for each planning authority, along with the Local Development Plan. This substantially increases the status of the NPF and concerns have been expressed that this creates greater central control and influence in the planning system.

The move to a 10 year cycle for reviewing the NPF better accords with development timescales, reducing the amount of time spent on preparing plans. It also means, however, that there is an increased likelihood of significant reviews needing to be made to reflect emerging policy issues and challenges.

We welcome the steps taken by the Scottish Government in this Bill to increase the time available for Parliament to scrutinise this Bill. Given the enhanced role to be accorded to the NPF, however, the Committee takes the view that the process of Parliamentary scrutiny must be significantly enhanced to include time for substantive engagement with the public. Provision for such enhanced scrutiny should be incorporated in the Bill and amendments brought forward to—

- require Parliament to be consulted on changes to the NPF

- remove limits to the timescales for Parliamentary scrutiny of the draft NPF (and any revisions) and give Parliament the power to establish such timescales as appropriate to the scope of the proposals according to normal Parliamentary business planning procedures

- require the draft NPF to be accompanied by a statement as to the process of engagement and consultation undertaken by Scottish Ministers in preparing the draft NPF as well as information on the impacts on equalities, human rights, children and young people, island communities and sustainable development (reflecting current reporting requirements for Scottish Parliament Bills)

- ensure that the final NPF reflects the views of Parliament as a whole rather than Scottish Ministers and has the standing to endure across successive governments. We recommend that the Scottish Government amends the Bill to enable the final NPF laid in Parliament to be amended by Parliament and, following any agreed changes, for the final NPF to be subject to Parliamentary approval.

We welcome the Scottish Government's commitment to bring forward amendments to the Bill at Stage 2 "to place procedures for significant amendments to the NPF on the face of the Bill" and its consideration of how to make appropriate arrangements for minor amendments. 9

We request further information on how the Scottish Government will ensure that the NPF has "clear read across to funding arrangements".

Subject to the above amendments being brought forward we are content with the proposals to strengthen the NPF.

Finally, we suggest that the NPF should provide an opportunity to create greater coherence between a range of national policy areas such as climate change, energy, marine planning and transport. We recommend that Scottish Ministers consider how such greater coherence might be established within the NPF and be reflected in the Bill.

Removal of strategic development plans

Section 2 of the Bill proposes to remove the requirement to prepare strategic development plans (SDPs). This, the Scottish Government explains, will ensure time and cost savings for those authorities involved in the production and delivery of SDPs, which have become too prescriptive, overly complex, costly and lengthy to produce.

The Policy Memorandum notes that the removal of SDPs is closely linked to the duty in the Bill for planning authorities to co-operate in relation to the provision of information to Ministers to inform the NPF. The technical paper suggests that the following might be activities that could be undertaken under this new duty:

joint working to gather evidence and address cross boundary issues as required;

bringing together the output from regional level evidence gathering to help inform and influence a single spatial strategy; and

supporting the preparation and implementation of a delivery programme for the NPF.1

Modern strategic, or regional, planning in Scotland began with the publication of the Clyde Valley Regional Plan 1946 and continued on a non-statutory basis until local government reorganisation in 1975 (introduced by the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973) and the creation of structure plans by the Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1972. Structure plans, which were produced for the whole of Scotland - initially by the nine regional councils and (following a further round of local government reorganisation in 1996) local authority joint boards, remained a feature of the Scottish Planning system until the passage of the Planning etc. (Scotland) Act 2006. The 2006 Act abolished structure plans and introduced strategic development plans.

Currently strategic development plans set out a vision for the long-term development of Scotland’s four main city regions (these are regions centred on Aberdeen, Dundee, Edinburgh and Glasgow), focusing on cross-boundary issues such as the amount and areas for housing, major business and retail developments, infrastructure provision and green belts/networks.

A strategic development plan is drafted by a Strategic Development Planning Authority (SDPA), the membership of which is defined in statutory designation orders. SDPAs are required to publish, and update, a development plan scheme which outlines its programme for preparing and reviewing the strategic development plan and for engaging the public. The scheme must also contain a participation statement setting out the ways in which local people and other stakeholders will be involved in the preparation of the plan. Each strategic development plan must be accompanied by an action programme, which must be updated at least once every two years.

Under the Bill, authorities would have flexibility and scope to determine the best ways to work together as a bespoke partnership (such as the regional working that already occurs in relation to enterprise and skills, and city region deals). In its technical paper the Scottish Government explains that—

It is intended that all local authorities will be part of a regional partnership but that it would be open to any authority to contribute their views on regional priorities for the National Planning Framework to address on an individual basis through the normal consultation process.1

The Bill proposes that Ministers have the power to direct planning authorities and key agencies to provide information to them on matters relevant to the preparation of the NPF. The policy aim of this part of the Bill is to "ensure that cross-boundary issues are properly addressed and used to inform the NPF". The Bill then sets out a range of planning authority matters that the power of direction might include such as the purposes for which land in the area is used and infrastructure in the area. The power of direction also includes a power to require two or more planning authorities to co-operate with one another in the provision of information to Ministers to inform the NPF.

In 2014 Kevin Murray Associates undertook research on SDPs for the Scottish Government on whether the SDP system in Scotland was fit for purpose. That research concluded that "The answer is that the system is still bedding in, it is not broken, nor is its potential yet fully optimised."3

Views on the removal of SDPs were mixed. Opponents of the proposals included organisations such as Clydeplan, which with its predecessor organisations have developed strategic plans for the Glasgow city-region for 70 years. Clydeplan argued that—

as our economic, land use and transportation patterns have evolved, it has become increasingly important to think about delivering economic growth across city regions. Even the independent panel acknowledged the value of planning at the city region scale, and the Scottish Government recognises that strategic planning is an essential element of the overall planning system.

Taking that in context, the question is how that is delivered. Obviously, the bill seeks to remove the statutory duty to prepare a strategic development plan. Clydeplan does not wish that to happen. We think that there is still a role for the statutory nature of the plan, although processes around it could be changed to expand and enhance it. However, if things are going to change and the preparation of an SDP is to be removed from the system, we firmly believe that a regional spatial strategy is critical to economic delivery and that any role in that regard as part of a regional partnership should be a statutory duty.

Local Government and Communities Committee 07 March 2018, Stuart Tait (Clydeplan), contrib. 199, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=11405&c=2070886

The City of Edinburgh Council (and others) also observed that some form of regional spatial planning will be required to underpin regional working in other circumstances such as the city region deals but questioned whether the tone in the Bill might weaken the resolve of local authorities to work together. COSLA observed that—