Justice Committee

Domestic Abuse (Protection) (Scotland) Bill: Stage 1 Report

Introduction

The Domestic Abuse (Protection) (Scotland) Bill (“the Bill”) was introduced in the Parliament, by the Cabinet Secretary for Justice, Humza Yousaf MSP, ("the Cabinet Secretary') on 2 October 2020. The Parliament designated the Justice Committee as the lead committee for Stage 1 consideration of the Bill.

Under the Parliament’s Standing Orders Rule 9.6.3(a), it is for the lead committee to report to the Parliament on the general principles of the Bill. In doing so, it must take account of views submitted to it by any other committee. The lead committee is also required to report on the Financial Memorandum and Policy Memorandum, which accompany the Bill.

The Presiding Officer has decided under Rule 9.12 of Standing Orders that a financial resolution is required for this Bill.

General policy objectives

According to the Scottish Government the provisions of the Bill are intended to improve the protections available for people who are at risk of domestic abuse, particularly where they are living with the perpetrator of the abuse.

The Policy Memorandum states that the Bill will do this by providing courts with a new power to make a Domestic Abuse Protection Order (“DAPO”) which can impose requirements and prohibitions on a suspected perpetrator of domestic abuse. This includes removing them from a home they share with a person at risk and prohibiting them from contacting or otherwise abusing the person at risk while the order is in effect.

The Bill also provides a power for the police, where necessary, to impose a very short-term Domestic Abuse Protection Notice (“DAPN”) ahead of applying to the court for a DAPO.

The Bill is also intended to help improve the immediate and longer-term housing outcomes of domestic abuse victims who live in social housing, including by helping victims to avoid homelessness.

The Bill will do this by creating a new ground on which a social landlord can apply to the court to end the tenancy of a perpetrator of abusive behaviour, with a view to transferring the tenancy to the victim. Alternatively, an application can be made to end the perpetrator’s interest in the tenancy where the perpetrator and victim are joint tenants, and enable the victim to remain in the family home.

Structure of the Bill

The Bill consists of 3 parts and 20 sections.

Part 1 of the Bill provides the courts with a new power to make a Domestic Abuse Protection Order (“DAPO”) which can impose restrictions and prohibitions on a suspected perpetrator of domestic abuse. This includes removing a suspected perpetrator from a home they share with a person at risk of abuse, and prohibiting them from contacting or otherwise abusing the person at risk while the order is in effect.

The Bill also provides a power for the police to impose a very short-term Domestic Abuse Protection Notice (“DAPN”) ahead of applying to the court for a DAPO in circumstances where such a notice is considered necessary to protect a person at risk from abusive behaviour by suspected perpetrator. The purpose of the DAPN would be to provide immediate protection to a person at risk in the short time period before an interim or full DAPO can be made by the court. The Bill requires the police to apply to a court for a DAPO no later than the first court day after they have imposed a DAPN.

Part 2 of the Bill creates a new ground on which a social landlord can apply to the court for recovery of possession of a house from a perpetrator of domestic abuse with a view to transferring it to the victim or, where the perpetrator and victim are joint tenants, to end the perpetrator’s interest in the tenancy and enable the victim to remain in the family home.

Part 3 of the Bill makes provision concerning powers to make ancillary provision and commencement.

Justice Committee's consideration

The Committee undertook a call for written evidence between 10 November and 4 December 2020. The Committee received 37 submissions in response to its call for evidence, and these are available online here.

The Committee began taking oral evidence on the Bill at its meeting on 15 December 2020 when it took evidence from the following members of the Scottish Government's Bill Team:

Patrick Down, Criminal Law & Practice Team Leader;

Anne Cook, Head of Social Housing Services;

Katherine McGarvey, Solicitor, Scottish Government Legal Directorate;

Rachel Nicholson, Solicitor, Scottish Government Legal Directorate.

On 22 December 2020, the Committee took oral evidence from three panels of witnesses. The Committee heard from:

Tam Baillie, Vice Chair, CPCScotland;

Dr Marsha Scott, Chief Executive Officer, Scottish Women's Aid;

Lyndsay Monaghan, Solicitor, Scottish Women's Rights Centre;

And then from:

Gillian Mawdsley, Secretary to the Criminal law Committee, Law Society of Scotland;

Detective Chief Superintendent Samantha McCluskey, Head of Public Protection, Specialist Crime Division, Police Scotland;

Joan Tranent, Vice-chair of the Social Work Scotland Children and Families Standing Committee, Social Work Scotland;

Professor Mandy Burton, Professor of Socio-Legal Studies, University of Leicester.

And then from:

Paul Short, Homelessness Manager, Fife Council, Association of Local Authority Chief Housing Officers;

Callum Chomczuk, Director, Chartered Institute of Housing

Garry Burns, Communication and Engagement Manager, Homeless Action Scotland;

Stacey Dingwall, Senior Policy Manager, Scottish Federation of Housing Associations.

Finally, on 12 January 2021, the Committee concluded its oral evidence taking on the Bill by hearing from Humza Yousaf MSP, Cabinet Secretary for Justice .

Consideration by other Committees

The Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee ("the DPLR Committee") considered the delegated powers in the Bill at its meeting on 3 November 2020.

The DPLR Committee considered each of the delegated powers in the Bill and published the report on its consideration on 6 November 2020. It determined that it did not need to draw the attention of the Committee or the Parliament to the delegated powers set out in the Bill.

The Finance and Constitution Committee issued a call for evidence on the Financial Memorandum for the Bill and received two responses.

The Finance and Constitution Committee agreed to take no further action in relation to the Bill.

Membership changes

During the Committee's consideration of the Bill at Stage 1, the membership of the Committee changed. James Kelly MSP left the Committee on 25 November 2020 and was replaced by Rhoda Grant MSP on 1 December 2020.

Background

Calls for the reforms now contained in Part 1 of the Bill began in during the parliamentary passage of what became the Domestic Abuse (Scotland) Act 2018 ("the 2018 Act"). The 2018 Act overhauled the criminal law in Scotland, creating a specific stand-alone criminal offence of domestic abuse. The new offence covers not just physical abuse but other forms of psychological abuse and coercive and controlling behaviour that were previously difficult to prosecute.

In 2017, during the Justice Committee's stage 1 consideration of the Bill which became the 2018 Act, a number of third sector organisations argued there was a serious shortcoming in the existing criminal law which that Bill failed to remedy. They said a person wishing to obtain protection from domestic abuse, particularly in relation to keeping a perpetrator away from their home, could only do so in two sets of circumstances. Firstly, where the perpetrator enters the criminal justice system, and secondly, if the person at risk applies for a civil court order against the perpetrator.

Following a committee evidence session on this topic at Stage 2 consideration of that Bill in 2017, the then Cabinet Secretary for Justice, Michael Matheson MSP, wrote to the Justice Committee. He confirmed that the Scottish Government intended to publish a consultation on what additional protections (if any) might be necessary to address this issue.

The Scottish Government consultation followed in late 2018 and an analysis of the consultation responses was then published in July 2020. Individual consultation responses, where permission has been given for them to be published, also appear on the Scottish Government's consultation webpage.

In September 2020, the Programme for Government for 2020-21 was published. In it, the Government commented:

“ The experience of lockdown reiterated the importance of protecting women and girls who are isolated and vulnerable during unprecedented times, and facing domestic abuse.”

As a result, the Scottish Government introduced the Bill now under consideration, describing it in its Programme for Government as "part of a suite of measures which would continue to implement the Scottish Government's Equally Safe Strategy" in the 2020-21 parliamentary year.

Key issues arising from the Stage 1 scrutiny of the Bill

Part 1 of the Bill

Domestic Abuse Protection Notices and Orders

Are further protective measures required?

The Scottish Government has indicated in its Policy Memorandum which accompanies this Bill that there is a “gap” in the existing civil justice system that requires this Bill to be passed. It said that the new powers in this Bill are therefore required to fill this gap in that, where someone is in a coercive and controlling relationship and experiencing domestic abuse, they are likely to lack the freedom of action to pursue, for example, a civil court process to remove a suspected perpetrator from a shared home.

The Cabinet Secretary told us that the proposed scheme of domestic abuse protection notices and orders is intended to “provide protection and breathing space for people who are experiencing domestic abuse while will enable them to take steps to address their longer-term safety and their longer-term housing situation”. He said that the scheme was not intended to replace existing criminal and longer-term civil measures but to address a very specific situation in which it is not possible to use criminal justice measures and the police consider measures are necessary to protect a person at risk.

Evidence received by the Committee offered mixed views on whether there is a need for new powers for the police and the civil and criminal courts, such as the proposed DAPN and DAPOs.

Witnesses including Scottish Women’s Aid, the Scottish Women’s Rights Centre and Professor Mandy Burton of the University of Leicester believe that there is a need for new powers as, in their view, a gap does exist currently in the protection afforded to women under existing powers. In written evidence, Scottish Women’s Aid stated, “A DAPN in intended to address those situations where the level of risk to the victim survivor is such that it is necessary for protective action to be taken. However, the police are, for whatever reason, unable to charge an abuser with a criminal offence. A DAPN would be used to bridge that protective gap”. They considered that the introduction of a DAPN could complement the police use of investigative liberation powers under the Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act.2016.

Dr Marsha Scott of Scottish Women’s Aid explained that, in her view, a legislative gap exists, firstly between the prevalence of domestic abuse and what is reported to Police Scotland which suggests that women do not feel sufficiently protected under current legislation to report their experiences and, secondly, that without emergency barring orders, the ability of the police to protect women and children is hampered.

In their written evidence, Barnardo’s Scotland said they welcomed the measures contained in the Bill and that the new legislation would protect and safeguard victims and their families. They stated that “Often abuse victims don’t want to move out of the home because they don’t want their children to experience upheaval. It is imperative that, where possible, the perpetrator is held to account and removed from the family home”. However, they voiced concerns that many situations arise where perpetrators do not care if there are bail conditions or other protective orders in place and considered that “it is not certain that the DAPN/DAPO will prevent this”.

Other witnesses were less convinced that there was a need for these new provisions. In its written submission, Police Scotland stated the proposed emergency powers would “address an identified gap where there is an insufficiency of evidence to criminally charge the perpetrator of domestic abuse and ongoing risk of abuse by them is identified”. In oral evidence, however, Detective Chief Superintendent McCluskey of Police Scotland told us that better use could be made of existing powers. Following delivery of training, she described a “shift in attitudes” to how police approach domestic abuse and that they had not previously used existing powers to their full extent but that was changing. She said, “We view the Bill as providing an exceptional tool for use in exceptional circumstances, but it should not constitute the routine response.”

In its written submission, the Law Society of Scotland highlighted its concerns about “a proliferation of potentially overlapping measures” particularly in respect of the Bill’s interaction with the police powers under the Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 2016 including those of investigative liberation. The Law Society stated “We suggest that evaluation of such measures is needed to avoid duplication or complications in the process when what we want to achieve is effective protection for the victims of domestic abuse”.

Gillian Mawdsley of The Law Society of Scotland told us she did not see a substantial gap in the current legislation and that the new notices would be used in very limited circumstances where there was an immediacy or short-term measure required. She said “How often and exactly where that would occur needs to be resolved, and there is a lack of clarity in the Bill”.

Dr Scott agreed that notices may be put in place for a relatively small proportion of cases and did not see them being routinely issued by police. She said, “We hope that there will routinely be evidence for arrest and criminal charge”. She explained, however, that in situations where evidence has been put to the Crown, but it chooses not to prosecute yet the police have strong concerns about the safety of the family, a notice “will be a critical tool that is not currently available”.x

The Cabinet Secretary told us that current civil measures place the onus on the victim to apply for orders and that could be “exceptionally difficult”. The scheme under the Bill would, in his view, offer an alternative as the police will apply for a DAPN and then a DAPO. He said, “This is where I think the biggest gap is” and “a number of other protective measures that are in place require the investigation of a criminal offence” therefore DAPNs and DAPOs were very different. In his view, they are unique in that they do not rely on a criminal offence having to have taken place.

Mr Yousaf rejected the idea that there would be duplication of powers but acknowledged that an overlap could occur if a criminal investigation or investigative liberation took place. He said, “There will, I hope, be a seamless transition between investigative liberation and a protection notice being put in place which should mean that there will be no gap in protection for the victim”. In response to how often he anticipated the new powers being used, he told us that this would be determined by the operational approach taken by Police Scotland, and while designed to be used in exceptional cases, even if used in five percent of cases “thousands of families will be helped and protected from harm”.

Existing civil protective orders

Witnesses discussed the drawbacks of existing civil protective orders (such as non-harassment orders, interim interdict or exclusion orders) citing the current, relatively lengthy, timescales in which they can be obtained, the costs associated with them and the availability of legal aid. One of the major barriers identified was that existing civil orders require to be sought and paid for by the applicanti and that the process of obtaining protective orders can generally take three weeks or longer from instructing a solicitor to a hearing. If bail conditions are not put in place, the potential victim of domestic abuse is left without protection and at risk of harm.

Tam Baillie of Child Protection Committees Scotland (CPCScotland) described existing measures as “insufficient”. He told us “the facility of exclusion orders which came in under the Children (Scotland) act 1995 was well intentioned, but it is hardly used and difficult for women and children to exercise that option”.

Lyndsay Monaghan of the Scottish Women’s Rights Centre explained that, where a report is made, but there is insufficient evidence to further engage in a criminal process, women are advised by police to seek civil protective orders. She said, “There will be a gap in protection between the reporting of the abuse or the ending of the relationship and trying to put in place one of those civil protective measures”. She added that civil orders could be “notoriously difficult” to put in place depending on the circumstances of the case.

Other witnesses acknowledged the risk of overcomplicating existing measures by introducing more legislation. In weighing up the risk, Dr Marsha Scott, Tam Baillie and Lyndsay Monaghan stressed that the safety of women was paramount. Tam Baillie told the Committee that “I see the order as a short-term measure whereas we are aiming for a longer-term stability for women and children”, adding, “Anything that can stabilise the situation including in the longer term is important”. Lyndsay Monaghan agreed, stating “The intention is that the orders and the notices will complement the civil protective orders that are currently in place”.

Referring specifically to exclusion orders, the Cabinet Secretary told us that one issue that came out of the 2018 Scottish Government consultation was that there was not great awareness that exclusion orders exist and are a remedy that people can seek. He said the Government were working on raising awareness. He emphasised the difference he hoped having the police apply for an order could make. He said, “We can perfectly well envisage how difficult applying for an exclusion order might be for a victim especially if they are in a toxic and controlling relationship. We hope that it will make a big difference that the DAPO can be applied for by Police Scotland”.

Operational challenges of using DAPNs

Practical and operational details on how the issuing of a DAPN will be assessed when a police officer attends a complaint

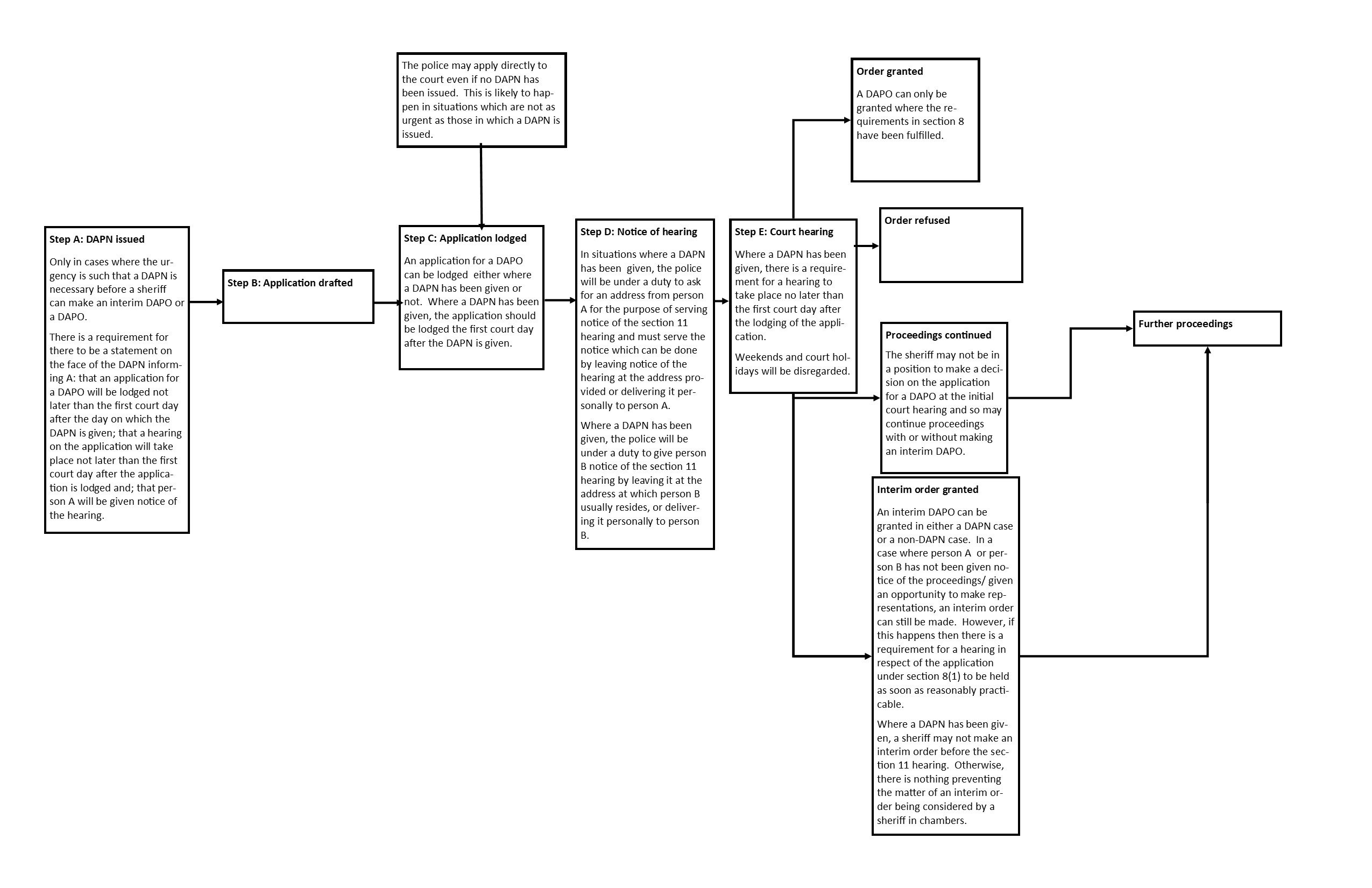

A number of witnesses expressed concerns about the practical and operational challenges of issuing DAPNs and called for further consultation and clarity. To aid understanding, the Scottish Government provided additional information on how the process is expected to work; see Appendix 1.

In her evidence to the Committee, DCS McCluskey of Police Scotland described to us the circumstances that Police Scotland envisaged in issuing a notice and thereafter applying for an order. This was where domestic abuse was reported and the perpetrator was removed by the police from the house in order to investigate but there is insufficient evidence to charge and the police were obliged to release them even though they considered, following assessment, that they posed a significant risk in the home. She said, “Statistics show that we have 6,000 such cases a year. That is why I am saying that there has to be an exceptional tool that is used in exceptional circumstances. We need to be able to take action. We can train officers but that takes significant investment so we need resources”.

Evidential threshold (section 4)

Section 4 of the Bill sets out a three point test relating to the imposition of a DAPN. At Section 4(1) it provides that a senior constable may make a domestic abuse protection notice in relation to person A if the constable “has reasonable grounds for believing that” person A has engaged in behaviour which is abusive to person B; that it is “necessary “ for a DAPO to be made to protect person B and; it is “necessary” to make the DAPN to protect person B from abuse before the sheriff can make a DAPO. The Scottish Government’s Bill Team confirmed the civil standard of proof would apply (i.e. “on the balance of probabilities”).

A DAPN may be imposed only by a senior police officer at the rank of inspector or above and several witnesses questioned how this would work in practice. In its written submission, the Law Society of Scotland questioned how the issuing of DAPNs by senior officers would work given they are typically desk-based and do not routinely attend at the scene. The Bill does not appear to have a specific power available to the police to remove a suspected perpetrator to the police station relating to a DAPN. The Law Society of Scotland questioned “What may be envisaged here by the policy is to permit a DAPN to be issued in circumstances where any action of removal to a police station would not be justified in terms of the Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 2016”.

DCS McCluskey echoed these concerns, stating “There is a lack of clarity and direction for us”. She told us that an inspector would rarely be on the ground at a domestic incident and officers would therefore be expected to conduct a risk assessment based on what they were faced with. If there was no evidence to charge, they would have to approach an inspector and convince them. She added that “The thresholds are different, one is criminal. If they have reasonable grounds to suspect, they can bring that person into custody to facilitate an investigation and then convince the inspector that there are reasonable grounds to believe. We might have some challenges to get people to understand the true thresholds. As I understand it, the legislation makes the inspector hold that belief rather than the officers, so they will have to convince that person”.

On this point, the Faculty of Advocates said that “For the avoidance of doubt, the Bill should make clear that it is the senior constable proposing to make the order who requires to have the reasonable grounds for belief which the Bill requires, rather than a police officer of the rank of constable (who may, for example, be attending the incident giving rise to concern).”

The Cabinet Secretary told us that in the majority of cases for similar orders in England (where there is insufficient evidence to charge an individual) the person would be in police detention as they are able to do where there are reasonable grounds to suspect that a crime has been committed. He said that the police might decide on further investigation that there is not enough evidence to determine that a crime has been committed but “if the test in section 4 is met, the police will go to someone with the rank of inspector or above to apply for a DAPN”. He explained where the police did not have reasonable grounds and the perpetrator had left the locus police could return to the station, determine whether the test in section 4 had been met and return to the locus or use normal procedures to track down the person and issue a DAPN.

The Committee received mixed views about the proposed test contained within Section 4. Social Work Scotland was content with the test. However, a number of other organisations including members of the judiciary such as the Sheriff’s Association, the Summary Sheriff’s Association and the Law Society expressed concerns both about the threshold imposed by the test in Section 4 and whether a DAPN would be a proportionate measure in the context of relevant rights under the ECHR. These organisations questioned the evidence which would be required before the test would be met. The Law Society commented that “the threshold seems to be that the senior officer has “reasonable grounds” to believe that there has been abusive behaviour. What does that mean in practice? Does that mean the police could serve a notice on an anonymous tip off from a neighbour even where the victim disputes the claim?”.

The Summary Sheriff’s Association said:

“… the evidential threshold for a senior police officer to conclude that the relevant test is met must be carefully considered. In comparison to existing protections and processes, discussed below, it is envisaged that a lesser evidential burden is required in order for a senior police officer to have reasonable grounds to believe that person A has engaged in the defined behaviour towards person B - such as ex parte statements from person B with no other supporting evidence.

Given the very serious consequences of a DAPN, the test for a DAPN must be carefully considered. In this context it may be appropriate to consider the statutory test for the comparable remedy available to person B in terms of section 4 of the Matrimonial Homes (Family Protection) (Scotland) Act 1981 – an interim exclusion order.”

Gillian Mawdsley and DCS McCluskey were of the view that the standard of proof required clarification. DCS McCluskey said:

“There is no component of risk in section 4. That is really important. People use the term “emergency order”, the police officer’s decisions on such an order will be risk-based. That is absolutely correct but what we see now has morphed slightly from what the intention was for emergency barring orders. At the start, the focus was on couples who co-habit but it now goes much wider. Furthermore, the Bill covers a single instance whereas the Domestic Abuse (Scotland) Act 2018 covers a course of conduct which enables the police to make a holistic assessment of the circumstances and, of course, to identify primary perpetrators.”

In written evidence, Police Scotland said that “Further clarity and guidance is necessary to enable straight forward and effective instructions and training to be delivered to frontline officers who will be attending domestic incidents and issuing DAPNs.” They added that:

“The proposed three point test at Section 4 offers no explanation of the term “reasonable grounds to believe” and whilst officers are familiar with the term, it is most commonly used as an objective test where criminality is suspected and a criminal investigation is undertaken” and “we feel that the language in the Bill should more strongly reflect the intention specifically in terms of DAPN’s being emergency measures taken as a precursor to longer term protective measures being implemented”.

Gillian Mawdsley agreed highlighting the, in her view, enormous discretion the Bill gives to the police particularly in light of someone being deprived of their home. She questioned what would constitute sufficient grounds for the making of a notice and exactly what kind of evidence would be required. She asked “What kind of evidence would be sufficient to trigger a notice and therefore deprive a person of their home for 24 or 48 hours or up to 4 days?”

The Scottish Government’s Bill Team in oral evidence stated that there are two elements to the test, stating “The senior constable who is making the decision has to hold a genuine belief and there must be reasonable grounds for that belief. The reasonable grounds part of it imports an element of objectivity into the test. That is important because it means the officer who is imposing the notice cannot act simply on their subjective belief”.

The Cabinet Secretary stated that he believed Section 4 to be pretty clear about when a notice should be applied and what the tests were. However, he told us “if there are concerns about areas that we could make clearer or strengthen I will take those concerns away and look at them”.

With regard to compliance with convention rights, the Bill Team did not see a conflict in situations where a notice would be required. Scottish Government officials stated that “Convention jurisprudence recognises that in some exceptional circumstances where the object of any given measure requires efficient and quick decision making not all the protections in article 6 can be afforded in the time if the objective might be undermined”.

This was echoed by the Cabinet Secretary who said, “We are talking about restricting somebody’s liberty in some way, quite severely, without a criminal offence having been committed. Therefore proportionality and necessity are absolutely imperative”. He offered assurance that ECHR compliance is a key consideration for any Bill brought forward and the proposed Bill complied with ECHR and human rights obligations. That consideration he said was why, in the Scottish Government’s view, a DAPN should only last for 48 hours as any longer would have “serious ECHR implications”.

Managing counter complaints

One of the prospective challenges a police officer may face at the scene is the suspected perpetrator of the abuse making a counter claim against the person making the allegation of abuse.

DCS McCluskey told us that where there is a counter accusation there is a lot of risk assessment and professional judgement required. She said “The Bill is quite difficult for us because action can be based on a single incident rather than a holistic view being taken of all the circumstances and any behaviour that has gone before. It is very challenging for officers in relation to counteraccusations”.

On where provisions interact with other elements/sanctions i.e. electronic tag/curfew

Police Scotland also called for clarity around where orders would sit in relation to other court imposed orders or restrictions such as bail and special bail conditions and other ongoing processes.

In a letter to the Committee, the Scottish Government’s Bill Team explained that where an offender is released on Home Detention Curfew (HDC), the powers of recall available to the Scottish Prison Service (SPS) allow for a broader range of considerations than just whether the specific licence conditions have been met. As well as taking account of practical considerations around the ability of that person to be monitored they allow a decision maker to consider anything that is in the public interest or anything which gives them concern for public safety. The police could therefore consider the application of a DAPN/DAPO to prompt action to consider the recall of an individual from their release or varying the conditions of that release. The Bill Team emphasised that the Scottish Government continued to work with justice agencies and the Scottish Prison Service and Police Scotland to examine the practical implications of the new system of protective orders where such a situation is likely to arise.

In response to calls that the Bill should be clearer about the interaction of part 1 with pre-existing requirements in the criminal justice system, the Cabinet Secretary told us that he would not close his mind to having that in the Bill but did not see the challenge as “particularly unique”. He set out how he envisaged the process working in that if somebody on home detention curfew (HDC) with electronic tagging is issued with a DAPN, it would be for Police Scotland to communicate that to the Scottish Prison Service. Ultimately he told us, it would be up to them to make a judgement call taking into consideration, firstly if the person had to move to another address and, if so, whether the HDC could continue and, secondly, whether the person who is subject to a DAPN is in breach of their conditions and should remain in the community or be recalled to custody. He said, “Where HDC is involved, those conversations will have to happen between Police Scotland and the SPS”. He added that it was “pretty routine” for Police Scotland to have such conversations with SPS but if a specific provision was called for he would consider it.

Liability on police if they fail to issue a DAPN

One of the other prospective challenges on Police Scotland suggested to the Committee is that of potential liability on them if they fail to issue a DAPN and then the allegation of domestic abuse is subsequently proven and/or the person is subjected to further abuse after they have left the scene.

DCS McCluskey said Police Scotland also had “legitimate concerns” about being held liable for taking action which was perceived to be wrong, or if there was inaction on their part when steps should have been taken. She said this could be addressed “If we apply a little more scrutiny, get more clarification on the threshold and are very clear about the circumstances in which we would apply it, that will build a bit of confidence among police officers who will be expected to make decisions and build the public’s confidence in our response.” She added, “I would like clarity in the Bill and perhaps time being taken to learn from England and Wales where the previous process has been repealed because of issues”.

Professor Burton agreed, stating “Rolling out the training and updating it to align with the process and procedural issues with protection notices will be crucial”. She explained that the way in which the police enforce or do not enforce protection notices will reflect their potential liability under human rights legislation as victims have rights under articles 2 and 3 on the right to life and the right to be free from inhuman and degrading treatment. She added that “The Bill is a very positive step towards meeting the obligation that the Scottish Government and the police have under human rights law to have in place appropriate levels and protective orders for victims of domestic abuse”.

Training required

The Scottish Government’s Financial Memorandum suggests that police training on the Bill might be delivered through a two-hour course making use of an e-learning package. Concerns were raised as to whether this would be sufficient for frontline officers.

Both Police Scotland and the Law Society emphasised an important role for further training and guidance for police officers. Police Scotland stated:

“a single nationally agreed and endorsed model of risk assessment which encourages common language and understanding of risk in domestic abuse across all sectors is needed. This would assist in improving the awareness and understanding of the public and other services of the proportionate measures taken by the police to manage and mitigate identified risk including the issuing of DAPNs. It would also ensure that DAPNs are issued where every case is judged on its merit and offers a degree of proportionality and necessity, i.e. where emergency and immediate measures are necessary rather than at every domestic incident attended where application could, in fact, be harmful to the overall situation.”

The Cabinet Secretary emphasised that, in recent years, Police Scotland have received extensive training on domestic abuse and coercive control in relation to the Domestic Abuse (Scotland) Act 2018. The matter of e-learning was based on information Police Scotland had provided as it pertained to the legislation. However, he said that the Government would “continue to discuss such matters with Police Scotland as the Bill progresses through the parliamentary process”.

Multi-agency involvement in decision making (sections 4-7)

In its written evidence, Police Scotland expressed concerns that they could issue a DAPN without any consultation with any other body, such as social work, and that this “is not in step with the established partnership approach currently taken across Public Protection to address risk.”

In oral evidence, the Scottish Government’s Bill Team responded that it was not the Government’s view and that, just because the Bill was silent on multi-agency approaches in the context of DAPNs, this did not mean that the Government did not think these approaches should happen in practice. The Bill Team suggested that the Scottish Government wanted to leave some flexibility for Police Scotland to determine how arrangements should operate in practice.

Dr Scott said she was “surprised” that Police Scotland had expressed such concerns, stating, “Our experience is that the police rarely engage with multi-agency structures for an initial call or in situations in which a notice would be served”. She explained that multi-agency working is valuable as it brings more information to decision making but that it takes time and the notice process was a short-term intervention which would thereafter be scrutinised by the court. She added “That subsequent scrutiny can be informed by multi-agency information”.

Tam Baillie agreed, saying “The police are first responders in the vast majority of protection cases in Scotland. There is nothing unusual about the police having to act singly as an agency”. In relation to child protection, he told us that where there are concerns about children, initial referral discussions (IRDs) take place very quickly and in the case of a notice being issued he would “expect that to be brought to the attention of the IRD process”.

The Cabinet Secretary acknowledged the concerns raised by the police that a two day window would make multi-agency working difficult. However, he explained that the court would be able to provide an interim order for a three-week period which could assist with multi-agency working and give Police Scotland more time. He emphasised that it was not unusual for Police Scotland to take a multi-agency approach and he would have concerns if operational practice was mandated in the Bill. He said he would “listen to the concerns that Police Scotland has and will try to work through them as we approach stage 2”.

Serving of a DAPN on an individual still living in a family home

In her evidence to the Committee, DCS McCluskey told us that Police Scotland “… cannot actually envisage a set of circumstances in which we would serve a notice on an individual who was still living in the family home. To my mind, that would significantly increase the risk to the victim and any children, as well as any other person in the home”. She added in subsequent correspondence that “If an individual (Person A) was still resident/cohabiting with Person B in the family home we would issue a notice (where it was assessed as required), however we wouldn't issue on an individual who was still physically present in the home. That is, we would not issue in the presence of the victim as it would increase risk.” She also told the Committee that the evidential threshold needs to be clear and the circumstances in which a notice should be issued “needs to be explicit”."

Duration of a DAPN (section 5 and section 11)

Section 5 of the Bill in conjunction with Section 11 proposes that a DAPN lasts until a DAPO or interim DAPO is made or, if no such order is made, until the associated court hearing ends.

One effect is that a DAPN could last as little as two days. In England and Wales, police imposed notices ordinarily last 48 hours but this approach has faced criticism from some that it does not leave enough time to prepare the legal case for any follow up court order. Notwithstanding this, the 48 hour time limit has been largely replicated in the current UK Domestic Abuse Bill that is being considered in the UK Parliament at present.

Police Scotland acknowledged the need for a short timescale given the prohibitions and restrictions conferred by a DAPN but expressed concerns that it created substantial challenges for the police in requiring to make an application for a DAPO shortly thereafter. Specifically, they highlighted the necessary ICT, information sharing and process development to enable applications to be delivered to the court within the stated timescales; the additional demand for a finite number of officers who already spend an average of nine hours dealing with each domestic incident they attend and the logistical and resource issues of ensuring legal representation at multiple hearings in different sheriffdoms across Scotland.

Gillian Mawdsley stressed the importance of timescales being restricted to absolute immediacy and voiced concerns about an extension of the notice period. She said, “There is an immediacy in the power being exercised by the police. The matter needs to go before a judicial authority at the earliest opportunity. That seems to me to be the proportionality and absolute substance of the Bill”. She added, “I understand the practical resourcing implications, but a notice should be used only in an emergency. It is entirely appropriate for the period to be until the first court day. I would be very resistant to any extension beyond that”.

Police Scotland expressed specific concern about the timescale between the notice and applying for the order and described this as “prohibitive”. They considered it should be extended to 7 days. DCS McCluskey told us the time limits on the notice probably raised the most significant practical concerns for the police not only in terms of the demand on resources but that it would also prevent them from taking a multi-agency approach.

Joan Tranent of Social Work Scotland and Professor Burton agreed that one day was a very short time and suggested that a four to seven day period may be better in enabling circumstances to be fully assessed.

The duration of emergency barring notices varies from country to country with some EU countries stipulating a longer period of than England and Wales and what is proposed for Scotland. A collection of papers published by the Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence provides a number of comparative case studies.

The Cabinet Secretary was of the view that it is serious to legislate on a restriction for 48 hours on somebody’s liberty in a way that excludes them from the family home and takes them away from their children without having been charged with a criminal offence. He told us “It is important, as a state, to have judicial oversight of that restriction of liberty and of the interference with their privacy and their right to a family life as soon as is practically possible, Any extension causes me concern”. He commented that, despite concerns relating to the 48 hours being a barrier to the police, for similar orders in England and Wales the 48 hour period had not been extended. He said, “I suspect that that was because there were similar ECHR concerns to those that we have”. Mr Yousaf stressed that the courts would be able to grant interim orders of three weeks which would give more time for the police to liaise with other agencies, for reports to be provided to the court and full assessment of other civil orders made.

Duration of a DAPO (sections 9 and 13)

Sections 9 and 13 of the Bill provide that a DAPO can last up to two months and can be extended to a maximum of three months. Section 13 of the Bill provides that an interim DAPO must not exceed three weeks including any extension.

The proposed policy approach contrasts with that for DAPOs in England and Wales. Under the UK Government’s proposed Domestic Abuse Bill, there is no general maximum time limit proposed. Consequently, DAPOs in England and Wales could function as an indefinite or long-term order as well as a short to medium-term one.

Proposed maximum time period for a DAPO

The Committee received mixed responses on what the maximum duration of a DAPO should be. Some respondents including the Scottish Women’s Rights Centre, Scottish Women’s Aid and Child Committee’s Protection Scotland expressed concerns that the currently proposed three month period was too short. The Scottish Women’s Right Centre said:

“The victim requires more comprehensive and long-standing protection than that of three months. It is often mistakenly thought that abuse will stop once the relationship ends. However, it has been found that post separation, abuse often persists or intensifies for women and children particularly in child contact negotiations, which can be prolonged, often lasting for well over three months and are used by perpetrators to continue the abuse”.

In their written submission, Scottish Women’s Aid stated “obtaining an exclusion order, interdict or non- harassment order can take considerably longer than two months. The court process is often further protracted, particularly in relation to exclusion orders, where perpetrators of abuse manipulate the court process to delay and continue the action. Some women’s aid groups report that applications for exclusion orders can take six months”.

The Scottish Government’s Bill Team referred to unpublished data from the Scottish Legal Aid Board on the average length of time that child contact and residence cases take to be determined, which showed that, in general terms, only 15% of contact and residence cases are determined within 6 months and a majority take more than 12 months. They concluded that “It is therefore unlikely that it would be possible for a case to be determined within the maximum time period for which a DAPO can have effect”.

In relation to obtaining views of the child, Tam Baillie considered that the length of the order was too short for the courts to be able to come to a reasonable view. He told us “it takes time to get alongside a child so that they can have the confidence to express their views to you and so that you are confident in what the child is saying”. He added “the prize is stability for the woman affected, her children and her family. That would satisfy one of the main policy objectives which is that the family should stay put while the perpetrator is moved on. A longer duration would more clearly fit with the policy intention”.

Dr Scott agreed, citing safety as being the paramount consideration. She said, “The system needs to be based on safety. It is important that we do not encourage courts to think that just because a perpetrator has not reoffended in the three months that an order has been in place it can be assumed they are no longer a risk to women. We have so much evidence that that would not be true”.

DCS McCluskey and Joan Tranent shared that view. DCS McCluskey told us that it can take a long time to build a victim’s confidence and resolve all the complex issues including those around housing. She said, “I am not convinced that two months is long enough to allow for meaningful intervention that is as effective as it could be”. Joan Tranent highlighted that systems in housing and social work do not move quickly and that three months is a very short time in which to get to know people and build up trust.

Gillian Mawdsley, however, took a different view. She thought the proposed period was too long and that there were other measures which could be put in place within that time. She said the Bill was not clear either as to the grounds for extension and what would be required. In response, Professor Burton highlighted that the remedies referred to by the Law Society had to be sought and paid for by victims themselves whereas a DAPO would not put the financial and administrative burden on the victim.

In its written evidence, the Faculty of Advocates said that any “maximum period should not be arbitrary, but rather should be based on evidence that such a period is required” if it was to be compliant with Article 8 of the ECHR. The Faculty also said it was unclear about the drafting of section 11 of the Bill.

The Cabinet Secretary told us that he found the evidence that a two or three month period was too short “persuasive”, but again cited ECHR considerations. He told us the evidence had reminded him that eviction and transfer of tenancy proceedings could exceed three months and that, albeit the individual could apply for alternative civil orders during that time, the onus would be on the victim to do so. He concluded that “there is a persuasive argument for us to revisit whether DAPOs could be extended in specific circumstances”. He also said he would consider the issue of stalking as part of the consideration of any extension.

Interim DAPOs (Section 10)

Section 10 of the Bill provides that an application can be sought for an interim DAPO which can last for a period of up to three weeks In oral evidence, the Bill Team considered that, in practice, interim DAPOs may prove popular as they would allow police time to properly prepare a case for a DAPO.

Section 10 enables the sheriff to make an interim DAPO “only if the sheriff considers, on the balance of convenience that it is just to do so”. One of the issues which the sheriff must consider is the risk that if such an order is not made, the suspected perpetrator will cause harm to the person at risk.

The Law Society commented that “Given that such an order can involve serious deprivation of a person’s rights in relation to their place of residence and/or their child, the test in the legislation is “on the balance of convenience. It will be interesting to note the evidential requirements expected by courts before granting such an important interim order”.

The Summary Sheriff’s Association questioned how evidence in support of the application will be recorded and presented in court. Given that section 10(5) provides that the sheriff can make an interim order even if person A and person B have not been given notice of the proceedings nor been given the chance to make representations, the Summary Sheriff’s Association stated that “there is real concern about whether such a provision is compliant with articles 6 and 8 or the ECHR”.

Whereas, there are specific provisions in Sections 8 and 12 for taking victims’ or children’s views into account in an application for a DAPO, there do not appear to be equivalent provisions in Section 10.

The relationship between Part 1 of the Bill and other court orders particularly those relating to children

A range of other legal measures can be imposed in respect of children under the existing law and which may require to interact with the powers in Part 1 of this Bill. These may include court orders to settle disputes between parents under the Children (Scotland) Act 1995 or child protection orders including those imposed under the children’s hearing system.

A number of organisations expressed concerns that the relationship between DAPNs and DAPOs and other court orders relating to children is not sufficiently clear in the Bill.

For example, the Faculty of Advocates said “We do not think the Bill is clear about what should happen. We cannot see any provisions within the Bill that address the question of what order should take precedence where there is conflict between a DAPN/DAPO and a family law order.”

Police Scotland said “there does not appear to be any practical guidance on how such conflicts will be managed. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the challenges of dealing with such conflicts and effectively navigating civil and criminal law accordingly. Further guidance and consultation is required”. Social Work Scotland called for the legal relationship between the different measures to be made explicit. Whereas, in oral evidence, the Scottish Government’s Bill Team said that, in its view, DAPNs and DAPOs will take priority over legal measures relating to children but this is not explicitly stated in the Bill.

Witnesses generally agreed that more clarity was required. Dr Scott told us she would like the Bill to “indicate clearly that domestic abuse protection notices and orders will supersede the arrangements under existing contact orders” and that there would be plenty of time to put contact arrangements back in place it the court deemed that to be appropriate. She told us “It is absolutely critical that children and their mothers are not forced into dangerous situations as an unintended consequence of enforcement of contact”. This view was shared by Lyndsay Monaghan who considered it was crucial that the position is clear in the Bill and in the guidance of what was expected of women in respect of facilitating contact and whether they are required to do so.

Professor Burton considered it was important that there was provision for which orders take priority particularly where there is conflict. DCS McCluskey was of the view that guidance would not be sufficient and said Police Scotland would welcome clarity in the legislation as they would be held accountable for how the legislation was applied. She said “It needs to be really clear what takes primacy there and that is not for us to decide. It needs to be explicit in the legislation”. Professor Burton agreed. She told us a large body of evidence suggested the risk of harm that results from pro-contact presumptions in domestic abuse cases is an international problem. She said, “We have to remember that emergency barring orders are a short-term remedy. If there is a conflict between a child arrangement order and an emergency barring order, the priority should be given to the latter because it is a short-term remedy for the protection of the family. After that, revisiting the child contact arrangements would be appropriate”.

The Cabinet Secretary said “My clear opinion is, given a breach of a DAPN or a DAPO will be a criminal offence, that there would be no legitimacy in a person simply expressing that their having a civil order allows them to see their children and that that takes primacy, that would not be the case.” He told us that he would be happy to consider whether that could be clarified in the Bill and that Members were equally welcome to lodge stage 2 amendments on this specific issue.

Consent of a person at risk

Neither Section 4 of the Bill (setting out the test for the making of a DAPN) nor Section 8 of the Bill (setting out the test for the making of a DAPO) require the consent of the person at risk for the provisions to be used.

Section 4(3)(b) of the Bill provides that the senior constable must take into account “any views of person B in relation to the notice” and at (c) “the welfare of any child whose interests the senior constable considers to be relevant”. Section 8(6) makes similar provisions which must be taken into account by the Sheriff ahead of making a DAPO and in addition at Section 8(6)(d) “any views of the child of which the Sheriff is aware”.

Witnesses acknowledged potential challenges in obtaining consent in relation to notices but were strongly of the view that women’s’ views and, where possible, consent should be sought in relation to orders.

The Bill Team recognised that the issue of consent was a difficult one in policy terms, particularly in relation to DAPOs. In practice, they thought that consent would usually be obtained from the person at risk. They thought that the Government’s approach could be useful for exceptional cases where a person at risk is too scared to offer consent or did not appreciate the danger they were in.

In relation to DAPNs, Dr Scott told us that Scottish Women’s Aid would like the police to seek the views of women and children but obtaining consent would not necessarily be a feature. In relation to DAPOs however, she told us “we have strong concerns about orders that are made without the consent or even directly opposing the will and wishes of women” She said we need “flexibility” in the system particularly if the court is convinced that, for example, the woman has been coerced or that there is imminent danger. She said we need to “change the language to make it stronger and to make it clear that we expect all elements of the justice system to seek the views of both the women and the children. That should be the default so that if the court does not have their views it should be asked why not”.

She added that “Consent of the victim-survivor to a DAPO is essential”, saying, “The problem with issuing orders without consent is non-consensual intervention not only disempowers, it reflects abusers’ tactics of controlling victim-survivors and it may well have the unintended consequence of placing them in more danger”.

In relation to DAPOs, similar concerns about the removal of autonomy from the victim were raised by the Scottish Women’s Rights Centre. In relation to DAPNs, Lyndsay Monaghan told us “our position is that views should be taken but it is accepted that consent might just not be possible at that stage”. As the DAPO is a longer-term order, she added that “it makes more sense to take consent at that point because it will have longer and wider reaching impacts on the woman”. She further stated that “one of the biggest complaints that we hear through our helplines, surgeries and other outreach is that women do not feel as though they are involved in the process or that they are heard. It is an access to justice issue when you do not feel as though the process is involving you. We would hate for that to be reflected in the Bill”.

She thought the language in the Bill needed to be clearer, stating “The Bill says that consent is not required to make a DAPN so it would have to be made clear that views must be taken to inform the process”. She echoed Dr Scott’s position on orders and considered that the woman’s view should “inform the whole process” and that rather than views being taken into account they “must be taken”. If that is a question of timing, then, in her view, the order must last longer in order to allow that process to happen whether it be through a victim impact statement or a woman appearing at a hearing.

Tam Baillie agreed. In relation to orders he said, “the system is basically unworkable unless there is consent. The longer the order lasts, the more we will need consent and the person’s views to be consistent with the imposition of the order”. He also considered that a provision should be included on contact arrangements if for example views of children over the age of 12 had not been taken.

DCS McCluskey emphasised that police officers already seek victims’ views every time they engage with them. She explained that there is a difference between seeking a victim’s views in relation to a notice and in relation to an order. She said, “The order is court imposed and consent is probably required to allow us to police any breaches, There is a clear line between the two”. She added that her “concern is about who would be tasked to if were required to obtain consent from individuals. Would there be an additional demand on the police, who would have to evidence all that for the application for an order, an interim order or an extension?” Gillian Mawdsley agreed that there must be a requirement that the victim’s views are sought and a requirement to ask for consent.

Professor Burton told us there are a variety of approaches across different European jurisdictions in relation to consent. Some require it and some do not. Her view was that as far as possible the victims wishes should be ascertained. She considered the legislation to be “a bit passive in saying that the victim’s views, when they have been sought, should be taken into account. Perhaps there needs to be a stronger requirement to actively seek the views of the victim”.

Joan Tranent stressed that when police attend a domestic abuse incident if the mother says that they do not consent to further information sharing but the police think there is significant risk to children, Social Work Scotland can take other routes and an automatic referral to children’s services would be made either immediately or the next day.

The Cabinet Secretary said he was not dismissive of the concerns raised in relation to consent and “was probably less minded to consider such a requirement for a DAPN”. He said “The DAPN comes in effect in the heat of an incident and in particular where coercive control is involved. If consent was required, that could be manipulated by a perpetrator”.

In relation to the DAPO, he thought the issue was more “finely balanced and more challenging” but that he would have the “same overriding concern”. He said, “From everything that we know about coercive control, in particular, a perpetrator could continue to perpetrate their abuse by manipulating the victim to ensure she does not give her consent”. In response to the evidence from Scottish Women’s Aid that there should be a requirement for consent but that flexibility was needed where coercive control was at play, Mr Yousaf said he found it difficult to understand how the Government could legislate for that. He told us he would consider the issue of consent for DAPOs but had concerns about how individuals might be manipulated into not giving their consent.

A duty to refer a person at risk to support organisations

Should there be a presumption in favour of referral?

The Scottish Government’s consultation asked for views on whether there should be a statutory duty on the police to refer a person at risk to support services. A majority were in favour of this approach. In their written submission, Police Scotland stated “As a single agency we do not have the skills and resources to provide the crucial long term support offered by our valued statutory and third sector partners who offer such specialist provision”.

The Committee explored whether a presumption to refer might be a worthy addition to the Bill. If such a presumption was included the police would be required to explain why such a referral was not made. The Scottish Government’s Bill Team told us they believed referrals were routinely happening in practice.

Dr Scott considered it was not so much whether a referral is made but how and when a referral is made. She told us Scottish Women’s Aid would support an “opt out arrangement” rather than a presumption similar to the current system of referral to women’s aid services. Currently, she said the police advise women of the service but they can choose not to be referred. This approach she said, “gives a strong message that the support services will welcome contact without taking the control out of the hands of women”. She told us this would be preferable as evidence shows that women are the best predictors of future harm and therefore the decision must be within their control. She explained that evidence suggests if a survivor is offered a referral within 24 hours of contact with police, she is around 90 percent more likely to take it up than if she is given the option after the fact. The timing of the referral is therefore crucial in her view.

Lyndsay Monaghan agreed with the “opt out” approach. She told us that, where women have been referred to Victim Support Scotland they have a lot more information about the process but where that fails and women do not get the information they usually do not engage as much. Tam Baillie told us that we should be careful about having a presumption but that “the assessment of needs and provision of support services should be for all parties, the women, the children and the perpetrator.”

DCS McCluskey stressed that police officers already share information quickly with their statutory and non-statutory partners when officers attend a domestic incident. Professor Burton thought a presumption of referral to support could be helpful as this is a crucial aspect of the success of emergency barring orders and that those with the greatest success are those that offer wraparound provision and referral to support. Services would require to be properly resourced to back that up. She agreed that victims should also be able to opt out as “referral must be consensual if it is to be beneficial”.

Joan Tranent of Social Work Scotland told us that she fully endorsed a multi-agency approach and that “sharing of information supports victims and their children”. She said that once an order is made future planning needs to be looked at which could also include the perpetrator’s behaviour and their capacity for change. In relation to referral pathways for perpetrators, DCS McCluskey told us that it would be welcome if there were resources there. She said, “There is a lack of resources there so the question is, “Who would we refer them to?” It would be welcome if there were resources there but there are not – not nationally”.

Which individuals are covered by a DAPN or DAPO?

Section 1 of the Bill requires a suspected perpetrator (Person A) to be 18 years or over and the person at risk (Person B) to be 16 years or over before they can be the subject of a DAPN or DAPO. This mirrors the approach in the proposed UK Domestic Abuse Bill for England and Wales.

The Scottish Government’s Bill Team argued that a very small number of 16 and 17 year olds would be living with an older partner. In that case, other child protection measures, for example, those imposed under the children’s hearing system would apply.

In his written submission, the Children’s Commissioner supported the Scottish Government’s proposed approach. He said, “Where either the person who is the subject of an order (Person A) or for whom it is intended to protect (Person B) is under the age of 18, it is important to recognise the additional protections all children under 18 are entitled to under the UNCRC. We therefore believe it is proportionate that Person A must be at least 18 years of age”.

The Shetland Domestic Abuse Partnership disagreed suggesting the relevant age limit for the perpetrator should be 16. It said, “It is perfectly possible to have a 17 year old perpetrator living with a 20+ year old partner and these orders could not be used to protect the victim or any children living in the household”.

The Scottish Women’s Rights Centre had similar concerns. It said, “We consider that this remains a grey area in terms of whether appropriate measures will be put in place for young perpetrators aged 16-18. Avoiding such a gap in access to protection is especially pressing, given that young women aged 16-19 experience domestic abuse at a higher rate than any other age demographic, and the abuse itself is no less severe”.

The obligations which can be imposed by a DAPN and a DAPO (sections 5 and 9)

Sections 5 and 9 of the Bill state which obligations a DAPN and a DAPO can include. Section 5 of the Bill sets out what a DAPN can require the suspected perpetrator to do, or refrain from doing.

The Scottish Government’s Bill Team confirmed that, as a DAPN and a DAPO can only cover partners and ex partners, stalking by an ex-partner is within the scope of the Bill but stalking by a stranger is not.

A DAPN and DAPO can impose obligations relating to a child usually living with a person at risk. However, all other obligations which can be imposed under a DAPN relate to the person at risk directly.

In its written submission, the Scottish Women’s Rights Centre argued that obligations should be able to be imposed under a DAPN which relate to friends or family members of the person at risk. The Bill Team argued that it was acceptable in policy terms to restrict the scope of a DAPO to the person at risk and children. The reason given was that the DAPN is a short-term measure and measures relating to the family and friends were possible under DAPOs.

Both Scottish Women’s Aid and the Scottish Women’s Rights Centre argued that obligations under a DAPN should also be able to specifically relate to a person at risk’s place of work or study and a child’s nursery, school or other childcare setting. In supplementary evidence, Scottish Women’s Aid said that the court may include any protections it deemed necessary in a DAPO or interim DAPO including provisions relating to family members, friends or colleagues of the victim. They stated, “Where an abuser poses an imminent risk of harm to the victim and/or the victim’s family or friends, arrest would be the appropriate response, not a DAPN in our view”.

The Scottish Women’s Rights Centre supported an extension of section 5(1) and did not consider it would reduce their effectiveness. They said:

“It should be possible to impose conditions on the perpetrator prohibiting them from entering other specified locations and approaching the victim/survivor such as places of work or study and close family or friends homes. We have two main reasons. Firstly the Council of Europe’s position is that “any regulation that is limited only to banning the perpetrator from the residence of the victim but allows him/her to contact the victim at risk in other places would fall short of fulfilling the obligation under the Istanbul Convention. Secondly, and critically, we frequently hear from women that they are continuing to be stalked and harassed by ex-partners following the breakdown of an abusive relationship. The women mention that the perpetrator will sit outside places the victim frequents in order to threaten and intimidate. In the current proposals, this behaviour would not be considered a breach of a DAPN”.

The Committee understands that the last point made here by the Scottish Women’s Rights Centre is not correct and that under section 5.1(f) of the Bill prohibits person A (the suspected perpetrator) from approaching, contacting, or attempting to approach of contact, person B (the alleged victim).

They also considered that it should be possible to impose conditions on the perpetrator prohibiting them from approaching the child’s place of education and that measures should extend to the perpetrator contacting the victim through a third party. They said, “We would submit that the effectiveness of the DAPN/DAPO may be significantly reduced if the measures do not cover these proposals and may leave the victim at risk of further abuse, stalking or harassment.

With specific reference to stalking behaviour by an ex-partner, the Scottish Government’s Bill team clarified that, in circumstances where a suspected perpetrator is subject to a DAPO and has been ordered to leave the home but continues to stalk the person at risk (such as sending unwanted or abusive communications), the Bill contains a power to make provision prohibiting that behaviour. They told us “Breach of a provision in a DAPO is a criminal offence”.

In relation to extending the obligations provided in section 5, the Cabinet Secretary told us that he sympathised with the position but that the challenge lay in the question of proportionality. He said that “the balance must be between empowering the police to protect the person at risk from domestic abuse and any children who might be involved and respecting the rights of a person against whom a DAPN has been issued but who has not committed a criminal offence”.

He added, “I would have to take legal advice on the matter in relation to ECHR implications because it would be quite challenging to impose that level of restriction without any judicial oversight”. A further challenge, he told us, would be how wide that circle of people with whom the individual would be prevented from communicating be and what would be the definition of a “family member”. However, he gave assurance that he would give consideration to concerns ahead of stage 2 and that consideration in that regard would be the protection of the victim but that equally important would be getting the balance right between proportionality and protection in terms of ECHR.

In response to concerns raised by Police Scotland as to what would happen if a perpetrator refused to provide an address so they could be provided with notice of a hearing, the Cabinet Secretary told us he did see some advantage in extending the list of requirements to include provision of an address. He explained that under Section 6(4) the police must ask the perpetrator for an address so the notice of a hearing can be provided. He said “You would think that it would be in the interests of the person on whom a DAPN has been served to provide an address. If they refuse to provide an address, that means they would not receive any notice of a DAPO hearing”. However, as there is no legal requirement to provide an address, he said “I can see some merit in our considering additions to the list of requirements and prohibitions contained in notices under Section 5. That is a good point and I would welcome the Committee’s views on it. Technically what people must provide is not set out in the Bill and I will examine it in further detail. Perhaps we can clarify the matter”.

Taking children’s views into account

Under Section 4 of the Bill, when considering whether to impose a DAPN, the senior police officer must take into account the welfare of any child whose interests that officer considers to be relevant to the making of the notice. Under Section 8(6))(d) and Section 12(4)(d) of the Bill, when determining an application for a DAPO, a sheriff must take into account “any views of the child of which the sheriff is aware”.

An obligation for the court to take children’s views is provided for in The Children (Scotland) Act 1995 and the Children (Scotland) Act 2020 (not yet in force) but only in relation to specific types of court proceedings which include court proceedings to resolve private disputes between two parents; proceedings under the Adoption and Children (Scotland) Act 2007 and proceedings under the children’s hearing system provided for by the Children’s Hearings (Scotland) Act 2011.

Some stakeholders raised concerns that the wording in Section 8 of the Bill appeared weaker than the formulation in the 2020 Act, specifically in its reference to views “of which a Sheriff is aware”. In its written submission, Scottish Women’s Aid said that the Bill should follow the drafting of the Children (Scotland) Act 2020 when discussing the welfare of the child and the requirement to take a child’s views into account.

DCS McCluskey told us that where possible, officers are encouraged to seek the views of children but that this could be difficult in emergency situations. She expressed concern at the length of time that police have to seek views between the notice and the order and commented that she did not think it was practically possible to take views into account on every occasion.

Professor Burton agreed, noting that there are time pressures in taking children’s views into account, particularly in relation to the notices. She told us that the short period for the notices would make it impossible to gather all the information and evidence that is needed. In her opinion, taking the views of children into account was therefore more relevant for the orders.

Tam Baillie told us there were challenges in obtaining the views of children and while progress is being made, we have a “long way to go” before we can be assured that we are taking the views of children into account appropriately. In his view, consideration must also be given to the age and stage of the children. He added that “We should not presume that children under the age of 12 do not have a view” and “there are real difficulties in getting the views of children under the age of five who attempt to act out their views through their behaviour”.

He believed that the length of the orders is too short for the court to be able to come to a reasonable view. He said, “I have no doubt that the wording could be strengthened regarding a requirement to take views into account but consideration of the age and stage of the children and the length of time that it might take to get alongside those children so that they are confidently able to express their views, is key”.

In supplementary evidence, CPCScotland provided the Committee with examples of good practice where children’s views had been given in court in relation to existing legislation including provisions in the Vulnerable Witnesses (Criminal Evidence) (Scotland) Act 2019 which aims to improve how children and vulnerable witnesses participate in criminal proceedings (by making more use of pre-recorded evidence in advance of a criminal trial) and funding for justice and social work agencies to improve the quality and process for Joint Investigative Interviews with vulnerable child witnesses.

They also cited a model developed in Nordic countries called Barnahus (child’s house) which combines elements of joint investigative interviewing within a child centred environment. They told us that “progressive steps have been taken towards the establishment of Barnahus in Scotland with work suspended due to COVID-19 re-start in January 2021. Other good practice examples included the Consulting Children service in the North East of Scotlandvii; the Children’s Rights Officerviii and the Children’s Advisory Worker at Edinburgh Domestic Abuse Advocacy Court Support (EDAACS)ix.

The Cabinet Secretary said it would be up to the judiciary to decide how children’s views were taken in a child-friendly manner and that judges as a part of their work received training on the handling of those matters. He told us he was happy to consider how views could be taken in relation to a DAPO and emphasised that, as part of the work being done by the Government through incorporation of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, such issues were “at the forefront of our mind”.

The criminal offence of breaching a DAPN or DAPO (sections 7 and 16)

Sections 7 and 16 of the Bill make it a criminal offence to breach either a DAPN or a DAPO without “reasonable excuse”. Police Scotland called for further discussion and detail on the practical application of what the Bill says on breaches. It put forward examples of challenges it may face:

“Where an officer issues a DAPN where an arrest has not been made, the officer has no powers to require the perpetrator to remain with them while the process is completed. If the perpetrator refuses to remain should they be arrested for a breach even though the DAPN has not been issued?

Where a perpetrator refuses or is unable to provide an address at which they may be given a notice of a DAPO hearing. Should that be considered a breach although it is not a requirement of the notice.

Where an arrest for breach is made immediately at or shortly after the time a DAPN is issued what impact will that have on the DAPO court hearing as a criminal offence will also have been committed and required to be reported to COPFS for consideration.”

In its evidence, the Faculty of Advocates said: