Justice Committee

Stage 1 Report on the Vulnerable Witnesses (Criminal Evidence) (Scotland) Bill

Executive summary

This report sets out the Justice Committee's consideration of the Vulnerable Witnesses (Criminal Evidence) (Scotland) Bill ("the Bill") at Stage 1.

The main policy objective of the Bill is to improve how children and vulnerable witnesses participate in the criminal justice system by enabling the greater use of pre-recorded evidence.i It does this by introducing a rule, applying to child witnesses in the most serious cases, which would generally require all of the child's evidence to be given in advance of the trial.

The Committee welcomes the introduction of this rule, which should reduce the distress and trauma caused to child witnesses through giving evidence, as well as improve the quality of justice. However, the Committee recommends that the Bill should be amended to apply the rule requiring pre-recording to child witnesses giving evidence in domestic abuse cases,ii given the trauma that can be caused to children in such cases.

The Scottish Government intends to take a phased approach to the implementation of the rule requiring pre-recording, starting with certain child witnesses giving evidence in the most serious cases in the High Court. The Committee agrees that this approach is sensible, given the significant costs associated with the Bill's reforms as well as the shifts in legal practice and culture which will be required.

On balance, the Committee considers that it is appropriate that the Scottish Government will have the power to extend the application of the rule to other serious offences and/or adult vulnerable witnesses by regulations. However, it is important that there is an opportunity for sufficient parliamentary scrutiny to ensure that any such extension will deliver benefits for witnesses in practice, whilst still protecting the rights of the accused.

The Scottish Government should set out a clear framework for each phase of implementation which can be used to monitor progress. The Scottish Government must also ensure that sufficient resources are in place for each phase, particularly to provide for appropriate facilities and technology for pre-recording witnesses' evidence.

The Committee supports the reforms in the Bill aimed at improving the current court processes for pre-recording evidence. However, as one witness told the Committee, "a bad interview done early is no better than a bad interview done in a trial". The Committee therefore considers that the Bill's provisions could go further, both to safeguard child and vulnerable witnesses against inappropriate questioning and to ensure that they are provided with wider support. Moreover, resources must be in place to ensure that all those involved in questioning child and vulnerable witnesses receive appropriate trauma-informed training.

A sustained effort must be made to expedite the process of pre-recording evidence, particularly for child witnesses. Otherwise there is a real risk that, in practice, a witness's evidence will still be pre-recorded a long time after the reported events have taken place. This will significantly undermine the intended benefits of pre-recording evidence, in terms of enabling the witness to recount events more accurately and to recover from them more quickly.

The Committee considers that there is a compelling case for the implementation of the Barnahus principles - or child's house model - in Scotland, as the most appropriate model for taking the evidence of child witnesses.

Whilst the Bill's aim of increasing the use of pre-recorded evidence is to be welcomed, it is clear that a Barnahus model remains a considerable distance from where things currently stand in Scotland. The Committee therefore recommends that urgent action be taken to adopt elements of the Barnahus principles, whilst continuing to work towards adapting the "one forensic interview" approach for Scotland.

In the Committee’s view, priority should be given to developing an enhanced joint investigative interview process, conducted by highly-trained interviewers in child-friendly facilities with other services to support children and families available "under one roof". Should the case be prosecuted, any further questioning of the child for the purposes of the trial should be pre-recorded within the same facility. This would deliver significant benefits for child witnesses and be a meaningful step forward in implementing the Barnahus principles.

The Committee recommends that the Parliament approve the general principles of the Bill. This report sets out a number of recommendations relating to the more detailed aspects of the Bill, as well as wider reforms that may be necessary to support the Bill's policy objectives. The Committee expects discussion of these matters to continue should the Bill progress further.

Membership changes

Fulton MacGregor and Shona Robison replaced Mairi Gougeon and Ben Macpherson on 6 September 2018. The membership size of the Committee was reduced from 11 to 9 Members on 6 September 2018, and consequently George Adam and Maurice Corry resigned as Members of the Committee.

Introduction

The Vulnerable Witnesses (Criminal Evidence) (Scotland) Bill (“the Bill”) was introduced in the Scottish Parliament on 12 June 2018. It is a Scottish Government Bill.

The Bill and accompanying documents can be found here. The Scottish Government has also published a Child Rights and Wellbeing Impact Assessment and an Equality Impact Assessment for the Bill.

A SPICe briefing on the Bill can be found here.

The Bill sets out reforms relating to the use of special measures in criminal cases.i

The Policy Memorandum accompanying the Bill states:

The main policy objective of the Bill is to improve how children, in the first instance, and vulnerable witnesses participate in our criminal justice system by enabling the much greater use of pre-recording their evidence in advance of a criminal trial.

Policy Memorandum, paragraph 4.

It is currently possible for a vulnerable witness to give evidence in advance of a criminal trial using the following special measures:

prior statement – allowing evidence to be given in the form of a written statement or recorded interview

evidence by commissioner – allowing a recording of evidence taken before a commissioner (a sheriff or High Court judge) to be played at the trial (questioning of the witness at the commission hearing is still carried out by prosecution and defence lawyers)

The main provisions of the Bill create a rule, applying to child witnesses and complainers (i.e. alleged victims) involved in the most serious cases, which would generally require all of the child's evidence to be given in advance of the trial. This would be done using a prior statement and/or taking evidence by a commissioner. The rule would not, however, apply to child accused.

The Scottish Government would have the power to extend the application of the rule in the future, for example, to other offences or to adult deemed vulnerable witnesses (i.e. witnesses who are the complainers in cases involving a sexual offence, human trafficking, domestic abuse or stalking).

The Bill makes other reforms aimed at improving current court processes for taking evidence by a commissioner. It is important to note that the reforms in the Bill will not directly affect how the police currently undertake investigations or interview witnesses.

The Bill also seeks to streamline the process for arranging for the use of standard special measures. Standard special measures are those measures which child witnesses and deemed vulnerable witnesses are automatically entitled to use (a screen, live link or supporter).

Background to the Bill

Evidence and Procedure Review

According to the Policy Memorandum, the Bill builds on the work carried out by the Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service (SCTS) as part of its Evidence and Procedure Review. The Review was set up to consider how criminal court proceedings might be improved by changes to the rules of evidence and procedure. Areas covered have included the treatment of witnesses, including child and other vulnerable witnesses. The work of the Review is discussed in more detail later in this report.

Scottish Government consultation

According to that analysis, there was overwhelming support for the Scottish Government’s longer-term aim of a presumption that child and other vulnerable witnesses should have all of their evidence taken in advance of a criminal trial. Respondents generally favoured the initial focus being on child witnesses in the most serious cases in the High Court. The majority also considered that a child accused should be able to give pre-recorded evidence, although respondents acknowledged that this would require further consideration given the different status and rights of the accused.

There were limited detailed views on the technical changes to the pre-recorded evidence process proposed in the consultation, but those provided indicated general support for the changes.

Overview of the Bill

The Bill amends existing provisions on special measures contained within the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995. It is a relatively short Bill consisting of 12 sections.

Section 1 of the Bill provides for a rule, applying to child witnesses involved in certain solemn cases,i which would generally require the court to make provision for all of the child's evidence to be given in advance of the trial.

This could be done using a prior statement and/or taking evidence by a commissioner. The rule would apply to child witnesses under the age of 18, including child complainers. It would not, however, cover child accused.

The Scottish Government would have the power, by means of regulations subject to the affirmative procedure, to extend the application of the rule to cases involving other offences prosecuted under solemn procedure. This power could, for example, be used to extend the rule to child witnesses in all solemn proceedings.

Where the rule does apply, the Bill allows for limited exceptions to the requirement for all of the child’s evidence to be pre-recorded. Section 1 states that an exception is justified where:

pre-recording all of the child’s evidence would give rise to a significant risk of prejudice to the fairness of the trial or the interests of justice, and that risk significantly outweighs any risk of prejudice to the interests of the child if the child witness were to give evidence at the trial

a child witness aged 12 or more wishes to give evidence at the trial and it would be in the child's best interests to do so

Where an exception applies, the Policy Memorandum envisages that the child’s evidence will be taken using a live television link.1

Section 1 also restricts the existing power of the court to review arrangements already in place for taking a child witness’s evidence. This is to ensure that this power is exercised in a way that is consistent with the requirement to pre-record all of the child’s evidence (subject to limited exceptions).ii

Section 2 of the Bill ensures that existing provisions in the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995 relating to child witnesses under the age of 12 do not apply in cases where the rule in section 1 of the Bill applies.

Section 3 provides Scottish Ministers with a power to extend the rule requiring pre-recording by regulations (subject to the affirmative procedure) to adult deemed vulnerable witnesses in solemn cases. Deemed vulnerable witnesses are complainers in cases involving a sexual offence, human trafficking, domestic abuse or stalking.

Section 4 relates to cases where the rule in section 1 of the Bill does not apply. It limits the court’s power to vary special measures already in place for a child or vulnerable witness if these measures enable the witness’s evidence to be taken in advance of the trial.

Section 5 of the Bill makes various changes to the existing process for taking evidence by a commissioner. In particular, it:

provides a statutory framework for ground rules hearings (pre-trial court hearings used to prepare for taking evidence by a commissioner)

allows commissions to be held prior to the service of the indictment

provides that the same judge should undertake the ground rules hearing and the commission where it is reasonably practicable to do so

These changes will apply to all cases where evidence is taken by a commissioner (i.e. not just to those where the rule requiring the use of pre-recorded evidence applies).

Section 6 of the Bill introduces a simplified procedure for securing the use of standard special measures.

Sections 7 and 8 make adjustments to the timeframe within which a court must consider a vulnerable witness notice and the timeframe within which a vulnerable witness notice must be lodged with the court.

Sections 9 to 12 are general provisions, dealing with consequential amendments, ancillary provision, commencement and the short title. The commencement provisions in section 11 of the Bill would allow for a phased approach to implementation of the rule requiring pre-recording. For example, the rule could initially be brought into force in respect of younger child witnesses involved in cases in the High Court.

A more detailed explanation of the provisions in the Bill can be found in the accompanying Explanatory Notes.

Justice Committee consideration

The Bill was referred to the Justice Committee for Stage 1 scrutiny and the Committee issued a call for evidence on 4 July 2018. The Committee received 30 responses to its call for evidence, as well as six further written submissions during its Stage 1 scrutiny of the Bill. All written submissions can be found here.

The Committee took formal evidence on the Bill at five meetings (see Annex A):

on 20 November 2018 from the Scottish Government Bill Team (the officials responsible for assisting the Cabinet Secretary for Justice in formulating the policy and drafting of the Bill)

on 27 November 2018 from representatives of Barnardo’s Scotland, Children 1st and the Scottish Children’s Reporter Administration; and then from representatives of Action on Elder Abuse, ASSIST, the Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland and Victim Support Scotland

on 4 December 2018 from representatives of the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service, the Faculty of Advocates, the Law Society of Scotland and the Miscarriages of Justice Organisation; and then from representatives of Police Scotland and Social Work Scotland

on 18 December 2018 from the Rt. Hon Lady Dorrian, Lord Justice Clerk, and Tim Barraclough, Executive Director, Judicial Office for Scotland, Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service

on 8 January 2019 from the Cabinet Secretary for Justice and Scottish Government officials

The Committee is grateful to all those who provided evidence which helped to inform its scrutiny of the Bill.

As well as receiving formal evidence, Members of the Committee visited:

Dundee Sheriff Court on 3 September 2018, where Members discussed with Sheriff Alastair Brown current procedures for vulnerable witnesses and the proposals in the Bill

Edinburgh High Court on 19 November and 13 December 2018, where Members viewed current facilities for taking evidence by a commissioner, as well as recordings of commissions. During the 19 November visit, Members met with the Lord Justice Clerk informally to discuss current procedures in the High Court for taking evidence by a commissioner and the changes proposed in the Bill

Statens Barnehusi in Oslo, Norway, on 10 December 2018, where Members discussed the Barnahus principles and their potential application in Scotland. The Barnahus principles, including learning from the Committee’s visit to Oslo, are discussed in more detailed later in this report.

The Committee is grateful to all those who gave their time to organise these visits and meet with Members, which were extremely helpful in informing the Committee’s scrutiny of the Bill.

Consideration by other committees

The Finance and Constitution Committee issued a call for evidence on the Financial Memorandum for the Bill, with a closing date of 28 August 2018. Three responses were received, following which the Finance and Constitution Committee agreed it would give no further consideration to the Financial Memorandum.

The Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee considered the Delegated Powers Memorandum, reporting on 2 October 2018 that it is content with the delegated powers provisions in the Bill.

Both the Financial Memorandum and the delegated powers provisions in the Bill are considered in more detail later in this report.

Current support for vulnerable witnesses

Definition of vulnerable witness

The Victims and Witnesses (Scotland) Act 2014 made changes to the support available for vulnerable witnesses. Relevant provisions were brought into force in September 2015. These included a new definition of vulnerable witness in criminal cases. That definition (inserted into Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995) covers:

child witnesses (under the age of 18)

witnesses who are the complainers in cases involving a sexual offence, human trafficking, domestic abuse or stalking (known as deemed vulnerable witnesses)

witnesses where there is a significant risk that the quality of their evidence will be diminished by reason of mental disorder, or fear or distress in connection with giving evidence

witnesses who are considered to be at significant risk of harm by reason only of the fact that they are to give evidence

It is important to note that the provisions in the Bill would not change this definition of vulnerable witness. The Bill creates a rule in favour of using certain special measures to pre-record a child witness’s evidence. If Scottish Ministers were to use the power in the Bill to extend this rule to adult deemed vulnerable witnesses, this would only apply to those witnesses already covered by the definition of deemed vulnerable witness set out above.

Special measures

The Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995, as amended by various pieces of legislation including the Victims and Witnesses (Scotland) Act 2014, provides for the use of special measures to assist vulnerable witnesses giving evidence in criminal cases.

The following special measures may be available to a vulnerable witness:

a screen in the courtroom stopping the witness from having to see the accused

a live television video link allowing the witness to give evidence from somewhere outside the courtroom

a supporter who can sit with the witness whilst the witness gives evidence

excluding the public from the court whilst the witness gives evidence

allowing the witness's evidence to be given in the form of a prior statement taken before the trial (this may be a written statement or a recorded interview)

a commissioner (a sheriff or High Court judge) taking the evidence of the witness in advance of the trial (questioning of the witness is still carried out by defence and prosecution lawyers), with the evidence being recorded and played during the trial

The first three forms of special measure are known as standard special measures. Both child and deemed vulnerable witnesses have an automatic entitlement to them. Although there is an automatic entitlement, a process for notifying the court of the intention to use a particular special measure must still be followed.

Where there is no automatic entitlement to use a special measure (either because of the type of special measure or category of vulnerable witness) the party seeking its use must apply to the court for approval. The decision on whether to approve its use is taken by the court based on information supplied in the application and any objection made by another party in the case.

One of the reforms made by the Victims and Witnesses (Scotland) Act 2014 requires a number of bodies, including the Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service (SCTS), to set and publish standards of service for victims and witnesses. The standards are monitored, reviewed and reported on annually. The relevant annual report for 2017-18 includes the following figures for special measure applications/notices received during the years 2015 to 2017:

2015 = 13,541 (2,617 in solemn cases and 10,924 in summary cases)

2016 = 34,123 (3,986 in solemn cases and 30,137 in summary cases)

2017 = 33,300 (4,610 in solemn cases and 28,690 in summary cases)

Applications for standard special measures (screen, live link or supporter) accounted for the vast majority of applications (between 98% and 99%).

Pre-recording of evidence

Current law and practice

The use of a prior statement and the taking of evidence by a commissioner are both types of special measure which can currently allow a witness to give evidence prior to any criminal trial.

A prior statement is an interview or statement which was taken before the hearing that is then played or read out in court. A prior statement can be in the form of a:

visually or audio recorded interview between the witness and the police

visually recorded interview of a child witness by a police officer and a social worker as part of a child protection investigation (known as a joint investigative interview)

written statement

A prior statement can be used to cover some or all of the witness’s evidence in chief (i.e. the testimony first given by a witness on behalf of the prosecution or defence, depending on who called the witness, prior to any cross-examination by the other side in the case). The witness still needs to be available for cross-examination at trial.

Taking evidence by a commissioner can, in addition to evidence in chief, cover any cross-examination and re-examination. For example, in the case of a prosecution witness, this could involve the witness being examined in chief by the prosecutor, cross-examined by a defence lawyer and, if necessary, re-examined by the prosecutor.

The party citing the witness must apply for the witness’s evidence to be given using a prior statement and/or evidence by commissioner. As these are not standard special measures, the court must be satisfied that they are appropriate measures to enable the witness to give their evidence.

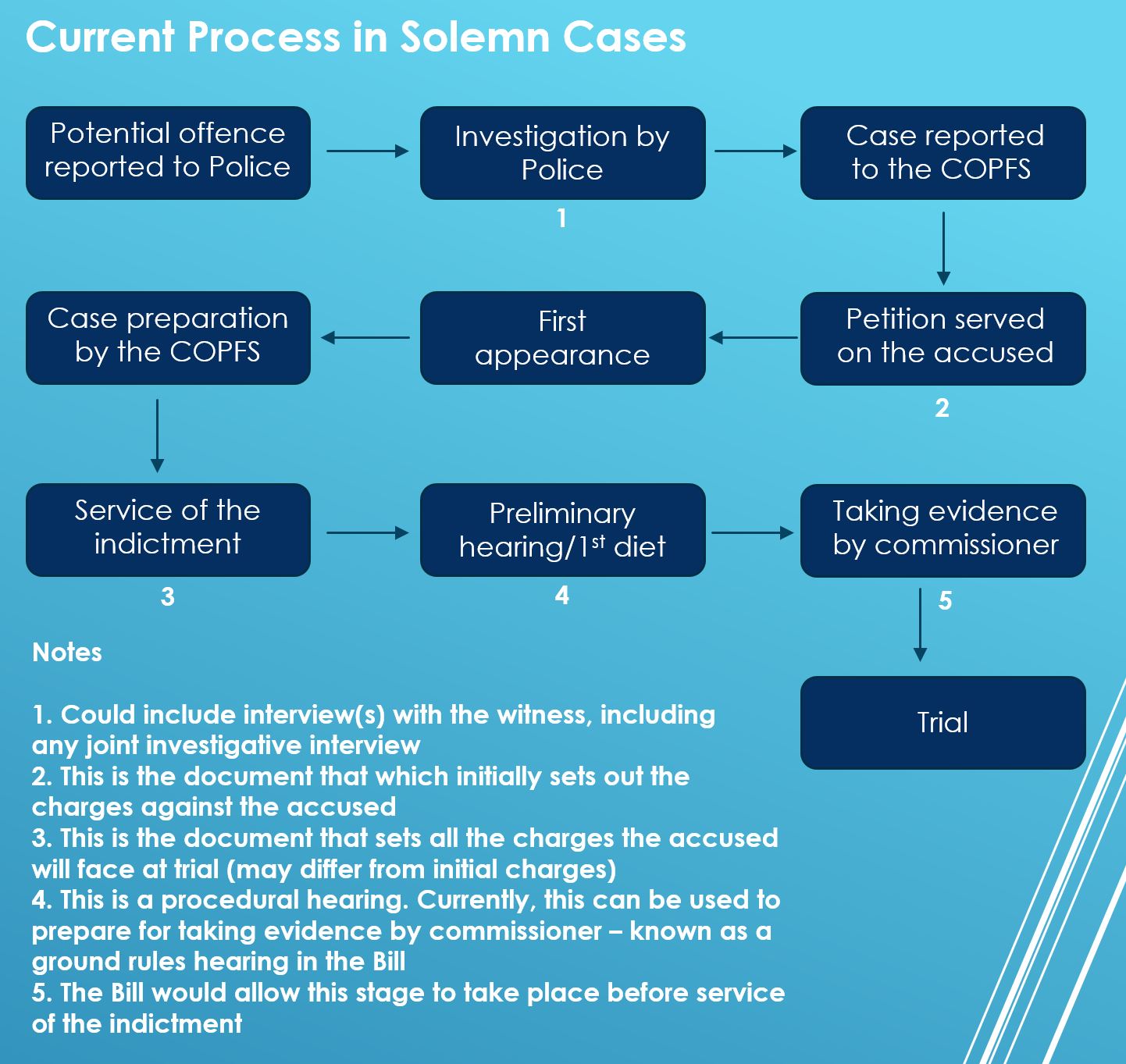

The flowchart below provides a simplified overview of the current process in solemn cases.i

The reforms in the Bill would not directly affect how the police currently undertake investigations or interview witnesses. During its scrutiny of the Bill, the Committee heard that witnesses may have repeated contact with the police at this stage. Daljeet Dagon, representing Barnardo’s Scotland, told the Committee of one case where “a young person had given the police 27 statements and, by the time the case came to court, was deemed to be an unreliable witness”.1

Whilst in some circumstances a witness’s statement to the police could be used as their evidence in chief, the witness may still be required to give further evidence at a commission hearing, in particular to allow for cross-examination. The provisions in the Bill would enable this hearing to take place earlier in the process - before the service of the indictment - although the Committee heard that, in practice, this may happen rarely. The timing of commission hearings is discussed in more detail later in this report.

Taking evidence by a commissioner

The Bill’s Policy Memorandum explains the process for taking evidence by a commissioner as follows:

The court will appoint someone to act as the commissioner (the person who will hear the evidence) and depending on which court is dealing with the case, this will either be a judge or sheriff. The witness will be asked questions in the usual way. The accused involved in the case is entitled to see the witness and hear their evidence, but is not usually allowed to be in the same room as the witness during proceedings. The evidence is recorded and this is then played during the trial or court hearing. Evidence in chief, cross-examination and re-examination can be done in advance using this method.

Policy Memorandum, paragraph 17.

The majority of commission hearings currently take place at in the High Court in Edinburgh.1 As the Committee saw during its visits to the High Court, commission hearings take place in a room situated within the court building in Parliament House. The witness will sit at a table, usually with a supporter, along with the commissioner and the prosecution or defence lawyer who is asking the questions. Also present in the room will be a technician to operate the recording equipment, the court clerk, and the lawyer for the other party. The accused will not be present but usually watches the commission via a live television link.

As noted above, the vast majority of applications for special measures are for standard special measures. Work undertaken as part of the Evidence and Procedure Review considered how current processes for pre-recording evidence could be improved. As a result of this work, a revised High Court practice note on the taking of evidence of a vulnerable witness by a commissioner was developed. This practice note came into effect on 8 May 2017.

The practice note is intended to encourage greater use of taking evidence by a commissioner. It includes guidance on the matters that the High Court will expect to be addressed at a procedural hearing held in advance of any commission, such as:

the form of questions to be asked and lines of inquiry to be pursued at the commission

practical arrangements such as the location and timing of the commission2

The Bill’s Policy Memorandum suggests that the practice note has had a positive impact in terms of increasing the number of applications for taking evidence by a commissioner.3

This view is supported by evaluations of the practice note, published by the SCTS. According to provisional figures set out in the second evaluation (published December 2018), a total of 133 applications for evidence by commissioner were lodged with the High Court in the first 10 months of 2018. That compares with a total of 50 applications for the 2017 calendar year. The majority of applications in both 2017 and 2018 related to child witnesses.

It is worth noting that not all witnesses in respect of whom an application is made for taking their evidence by a commissioner will go on to record their evidence. This can be for a variety of reasons including the accused entering a guilty plea or the Crown deciding not to proceed with the case. The evaluation by the SCTS found that, of the 50 applications in 2017:

66% (33 applications) were called at a procedural hearing

58% (29 witnesses) had their evidence recorded at a commission hearing

50% (25 witnesses) had their pre-recorded evidence played at trial

For those 25 witnesses who had their evidence played at trial, their involvement with the criminal justice system concluded an average of 57 days (8 weeks) earlier than would have been the case if they had given their evidence at trial.

The case for reform

As noted earlier, the Bill builds on the work carried out by the SCTS as part of its Evidence and Procedure Review. The first report of that Review, published in March 2015, stated:

It is now widely accepted that taking the evidence of young and vulnerable witnesses requires special care, and that subjecting them to the traditional adversarial form of examination and cross-examination is no longer acceptable. This is for two main reasons. The first is that, as has been known for some time, the experience of going to court and recounting traumatic events is especially distressing for children, and can cause long-term damage, particularly where the necessary healing process for a victim of abuse is delayed for months, if not years. … The second reason is that, particularly for young and vulnerable witnesses, traditional examination and cross-examination techniques in court are a poor way of eliciting comprehensive, reliable and accurate accounts of their experience.

Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service (March 2015), Evidence and Procedure Review Report, paragraphs 2.1-2.3.

The report concluded that, in respect of measures designed to make the experience of child and vulnerable witnesses less traumatic, “Scotland is still significantly lagging behind those at the forefront in this field”.1

This first report was followed by a Next Steps Report, published in February 2016, which recommended that:

Initially for solemn cases, there should be a systematic approach to the evidence of children or vulnerable witnesses in which it should be presumed that the evidence in chief of such a witness will be captured and presented at trial in pre-recorded form; and that the subsequent cross-examination of that witness will also, on application, be recorded in advance of trial.

Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service (February 2016), Evidence and Procedure Review - Next Steps Report, paragraph 74.

Following publication of the Next Steps Report, two work-streams were established: one focusing on the visual recording of evidence in chief (particularly the use of joint investigative interviews) and one focusing on the pre-recording of further evidence.

The report of the work-stream on pre-recorded further evidence set out a vision which, if implemented in full, “should eventually lead to no child or vulnerable adult witness having to wait until trial to give their evidence in solemn proceedings, or attend court to give evidence at trial unless they choose to do so”. However, the report expressed support for a phased approach, recognising that “realisation of this vision will have resource implications, including a shift in resources to the front end of investigations”.2

The Policy Memorandum accompanying the Bill states that, whilst progress has been made, “more can and should be done to support child and other vulnerable witnesses, whilst protecting the interests of people accused of crimes”.3

A rule requiring the pre-recording of evidence

The principal reform in the Bill is to create a rule, applying to child witnesses involved in the most serious cases, which would generally require all of the child’s evidence to be given in advance of the trial. This could be done by the use of a prior statement and/or taking evidence by a commissioner.

The Scottish Government’s policy justification for this rule is that greater use of pre-recorded evidence will improve the experience of child witnesses. The Policy Memorandum highlights the potential for child witnesses to be “re-traumatised through their participation in the criminal justice process”, and that giving evidence in court long after events have taken place does not support witnesses to give their “best evidence”.1

The Policy Memorandum goes on to state:

Pre-recording evidence does not specifically address the issue of the length of time between events and the ultimate trial. But in certain circumstances it can be an appropriate way to give more certainty to a vulnerable witness that their evidence will be taken at an earlier stage, and it enables the evidence to be taken at a specific time, without the uncertainties which arrive from the programming of trials.

Policy Memorandum, paragraph 8.

The rule in the Bill requiring pre-recording would apply to most child witnesses under the age of 18, including child complainers. It would not, however, cover child accused. According to the Policy Memorandum, applying the rule to child accused would raise “complex issues that require to be further explored in particular that requiring pre-recording could prejudice the child’s right to remain silent and to not give evidence”.2

The rule would apply to prosecutions under solemn procedure (i.e. High Court or sheriff and jury cases) for the following offences:

murder

culpable homicide

assault to the danger of life

abduction

plagium (theft of a child)

various sexual offences (e.g. rape, sexual assault and communicating indecently)

various offences relating to human trafficking and exploitation

various offences relating to female genital mutilation

an attempt to commit the above offences

The Scottish Government would have the power, by means of regulations, to extend the application of the rule to child witnesses in cases involving other offences prosecuted under solemn procedure. This power could be used to extend the rule to all such offences. It would also be possible to remove an offence from the list covered by the rule.

It would not, however, be possible to extend the rule to offences prosecuted under summary procedure.

Although the rule, as provided for in section 1 of the Bill, relates to child witnesses involved in both High Court and sheriff and jury cases, the commencement provisions in section 11 of the Bill allow for a more phased approach. Thus, for example, the rule could initially be brought into force in respect of younger child witnesses involved in High Court cases only.

The Scottish Government’s view is that the introduction of a rule requiring pre-recording will require a substantial shift in criminal practice and it is therefore appropriate to focus initially on child witnesses in the most serious cases. The Policy Memorandum states:

There will be a number of practical and operational implications for justice sector partners in the introduction of the new rule. In order to ensure that any changes to how evidence is taken can be phased in a controlled and achievable way, targeted first at those who are the most vulnerable, a narrow and focussed approach has been taken in the Bill. However, the Bill provides the framework for a progressive extension of the arrangements to other categories of vulnerable witnesses, including, in due course, adult deemed vulnerable witnesses. Over time, the Scottish Government anticipates that it will provide the basis for pre-recording evidence to be used much more regularly in the Scottish criminal justice system.

Policy Memorandum, paragraph 68.

Section 3 of the Bill therefore provides a power for Scottish Ministers to make regulations extending the new rule to adult deemed vulnerable witness giving evidence in solemn proceedings. The Policy Memorandum notes that any extension to adult deemed vulnerable witnesses would likely be commenced on a phased basis (e.g. initially to complainers in sexual offence cases in the High Court).3

Support for the rule requiring pre-recording

Most of the evidence to the Committee supported the introduction of the rule in the Bill, to encourage the greater use of pre-recorded evidence for vulnerable witnesses. This support was particularly strong in relation to child witnesses.

The SCTS, for example, welcomed the Bill “as a critical step in improving both the experience of witnesses and the quality of justice”.1 Referring to the Evidence and Procedure Review, the submission noted:

At the heart of the Review’s proposals and recommendations was the idea that justice would be best served if young and vulnerable witnesses could give evidence in a way that maximised the chances of it being comprehensive, reliable and accurate, and minimised any potential further harm or traumatisation from the evidence-giving process itself. It also recognised that traditional adversarial procedures and techniques did not appear to meet those requirements.

Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service, written submission.

Concerns about existing processes for taking evidence

Echoing the reasoning set out in both the Evidence and Procedure Review and the Bill’s Policy Memorandum, evidence to the Committee emphasised the distress caused to child and vulnerable witnesses through traditional processes for giving evidence. A submission from Children 1st stated:

Over and over again child victims and witnesses have told us that Scotland’s justice system – designed for adults and rooted in the Victorian era – often causes them greater trauma and harm. At the same time, as scientific understanding of child development – and recently our understanding and awareness of the impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences – has grown, it has become overwhelmingly evident that Scotland’s traditional approach to justice is the least effective for eliciting consistent, reliable accounts from child victims and witnesses.

Children 1st, written submission.

Other evidence highlighted that similar concerns applied in relation to adult vulnerable witnesses. For example, a submission from Rape Crisis Scotland stated:

The current approach to taking evidence from rape complainers causes significant additional distress and trauma. There are frequently significant delays in cases coming to trial, with cases often taking two years or longer from the police report to trial. Complainers build themselves up to give what can be very difficult evidence only to get a call the night before to say the trial isn’t going ahead. This can happen many times. This causes considerable distress, and does not assist in complainers being able to give their best evidence.

Rape Crisis Scotland, written submission.

Benefits of pre-recording evidence

The Committee heard that removing child and vulnerable witnesses from the court environment, with its traditional approach to examination in chief and cross-examination, could both reduce the distress caused to witnesses and improve the quality of their evidence.

Witnesses also emphasised that, by reducing the time between events being reported and the evidence being taken, pre-recording could enable the person to recover from the events more quickly and recount them more accurately. As the Lord Justice Clerk told the Committee:

When children, in particular, are asked to give evidence at a time that is remote from the event, not only has their memory diminished, but they are more likely to be confused by general questioning about the incident, and in cross-examination might come across – often wrongly – as being shifty or unreliable. Indeed, they not only find it difficult to deal with questions at that stage, but are more inclined to agree with the questioner when they cannot remember something. Clearly, having a commission much closer to the incidents of which they were complaining would enhance their ability to recall and give accurate and comprehensive evidence and, of course, would reduce the harm to their lives, because they would be able to get on with their lives without having to attend the trial.

Justice Committee, Official Report 18 December 2018, cols. 3-4.

Children 1st similarly argued that it was in the “best interests of the child to give their complete testimony as soon as possible”, noting that:

Avoiding undue delay helps ensure children’s memories are as fresh as possible, reduces the distress children feel because they are having to wait to give evidence and would allow children to start their journey of recovery more quickly. By doing so it will also improve the quality of the child’s evidence which is in the interest of all parties in the proceedings.

Children 1st, written submission.

In oral evidence to the Committee, Daljeet Dagon, representing Barnardo’s Scotland suggested that delays in taking a child’s evidence could impact on how that evidence was perceived by the court:

We know of young people who had offences committed against them when they were 14 but were 16 and a half by the time they presented at court, by which point they were very different people from who they were as 14-year-olds. Because of the trauma that they have experienced, they can be involved in a lot of behaviours that are not seen to be positive. What the court sees is a difficult, belligerent, drug-addicted, alcoholic young person instead of the child they were when the offences happened.

Justice Committee, Official Report 27 November 2018, col. 12.

Evidence from the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service (COPFS) emphasised that pre-recording evidence provided greater certainty for the witness and minimised the distress that could be caused by any future delays in the trial process.1

However, as is discussed further below, some evidence to the Committee expressed concern that, despite the reforms in the Bill, vulnerable witnesses may in practice still be giving their evidence long after the initial allegations were made.

Argument for further reform

Some evidence, whilst supporting the greater use of pre-recording, suggested that the Bill did not go far enough to address the potential distress caused to children and vulnerable witnesses through giving evidence. For example, the Committee heard that simply recording evidence earlier in the process would not necessarily improve the witness’s experience. As Colin McKay of the Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland said, “a bad interview done early is no better than a bad interview done in a trial”.1

This evidence emphasised the need for sufficient resources to implement the Bill, alongside additional measures to support child and vulnerable witnesses. Both these issues are discussed in more detail later in this report.

Evidence from some children’s organisations went further, arguing that the Bill was a missed opportunity to make more fundamental changes to improve children’s experience of the criminal justice process. In oral evidence Mary Glasgow, representing Children 1st, argued that the Bill “does not go as far as it should in realising children’s rights and enabling children to give evidence in a way that is commensurate with their developmental stage, that takes account of the way in which they communicate and which understands the impact of trauma”.2

She went on to say:

The Bill represents progress, but we are still tinkering incrementally with a system that is not and never will be built around children’s needs. That is why we are urging the Committee to think about the Bill as a start rather than a finish and to understand that, although it is better than what we currently have, it is nowhere near good enough for children. We are still squeezing and squashing children into a system that is not built with their needs in mind.

Justice Committee, Official Report 27 November 2018, col. 18.

In her view, the Bill should go much further in working towards the implementation of a Barnahus approach – or child’s house model – in Scotland, which would remove children from the court process entirely.3

Similarly, in its written submission to the Committee, NSPCC called for whole-system change to “move beyond the bolting on of ‘special measures’ to an adult-orientated system, towards a genuinely child-centred justice system”.4 It expressed support for implementing a Barnahus approach in Scotland.

The Barnahus principles are discussed in more detail later in this report.

Concerns about the rule requiring pre-recording

Some evidence to the Committee highlighted the need to balance the rule requiring pre-recording with sufficient protections for the rights of the accused.

For example, a submission from the Faculty of Advocates, whilst expressing support for the proposed rule, also highlighted the importance of being able to test the evidence of the vulnerable witness on an informed basis:

In principle, the Faculty of Advocates has no opposition to the introduction of such a rule. It is now well established that child witnesses benefit significantly from giving evidence in a different environment: away from the antiquated, and sometimes intimidating, environs of the courtroom; by answering questions that are simple and unambiguous; and by doing so as near in time as possible to the events in question. It is also expected that capturing the 'best' evidence of the child is in the wider interests of justice. However, the Faculty considers it vital that sufficient safeguards are in place to enable the rule to operate fairly, and to ensure that there is no scope for an increase in miscarriages of justice. It is therefore essential that the evidence of the child can be tested sufficiently and on an informed basis.

Faculty of Advocates, written submission.

In oral evidence, Dorothy Bain QC, representing the Faculty, expanded on the safeguards required:

The Faculty envisages insurance in the form of full disclosure of evidence at an early stage, a proper opportunity for defence counsel to prepare for the case being presented against their client, and an appropriate opportunity for cross-examination of witnesses, arising from, say, a child’s joint investigative interview to the police being led as evidence in chief. Our position is just a general recognition that change might upset a balanced procedure, so it must be ensured that individuals in that procedure are protected against miscarriages of justice.

Justice Committee, Official Report 4 December 2018, col. 9.

The Faculty’s evidence particularly stressed the need to ensure that the COPFS meets its disclosure obligations, so that defence lawyers are properly informed of the evidence and are able to prepare and present the accused’s case. Its written submission stated:

It is considered essential that there is timeous disclosure of all available and relevant evidence prior to cross-examination. The Faculty believes that a systemic failure to do so represents the single most significant obstacle to the success of this legislation. It is essential that this matter is not overlooked, and that the issue is resolved before the legislation is brought into force. The Crown should be asked to produce clear evidence that its current system of disclosure is fit for purpose and meets its statutory obligations under the Criminal Justice and Licensing (Scotland) Act 2010. Unfortunately, at the present time it is not uncommon for late disclosure, particularly of material such as telephone and computer records, or medical and social work records, to be made available to the defence at a very late stage in the proceedings. This problem is identified as regularly occurring in sexual offence cases. Provision of this late material undoubtedly impacts on the ability to cross examine witnesses, as it often results in the need to instruct expert reports and to make applications under sections 274 and 275 of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995. Such late disclosure would be difficult for any Judge to ignore and would undoubtedly delay any commission.

Faculty of Advocates, written submission.

These concerns were echoed in the written submissions from the Law Society of Scotland and the Miscarriages of Justice Organisation.

Use of prior statements

Evidence from the Faculty of Advocates, Glasgow Bar Association and Sheriffs’ Association expressed concern that the drafting of section 2(4) of the Bill, which provides that a prior statement could be used as “all of the child witness’s evidence”, could preclude the opportunity for cross-examination. The Faculty’s submission argued:

There can be no equivalence between an unchallenged pre-recorded statement and evidence on commission. There must always be scope for cross-examination and the subsection may have to be re-visited to make sure this is clear.

Faculty of Advocates, written submission.

In response to this specific concern, the Bill Team emphasised that it was not the Scottish Government’s intention to limit the scope for cross-examination:

We are 100 per cent clear that that is not the policy intent. … What we have tried to allow for in the Bill - and where concern has sometimes arisen - is that there is a real possibility that a child’s prior statement might be taken and the defence might not have any questions. If that is the case, we do not want a commission to have to be set up and for everybody to be sitting there, only for the defence to say that it has no questions and for the child to be sent away. We have to allow for some circumstances in which the prior statement might be the only evidence. However, if the party that has not called the witness wants to do any questioning, that will still happen.

Justice Committee, Official Report 20 November 2018, col. 17.

Risk of miscarriages of justice

The Miscarriages of Justice Organisation was more critical of the Bill. In its written submission it expressed serious concerns about expanding the use of pre-recorded evidence, arguing that this struck at the essential nature of the adversarial process:

The currently adopted procedure whereby certain witnesses are examined by video link provides the desired protection to the witness but differs fundamentally from the now proposed procedure in that the jury is able to see the contemporaneous examination of the witness. The separation of this process from the trial, by time, would fundamentally strike at the necessary relationship between witness and jury, since the witness would be giving evidence in the absence of the jury both by place and time. In simple terms, the witness would not be speaking to the jury when giving evidence.

Miscarriages of Justice Organisation, written submission.

The submission went on to argue:

Defence counsel and, by extension, accused persons, would be significantly disadvantaged by their inability to cross-examine Crown witnesses on matters arising and information coming to light in the course of a trial. It has long been recognised, in part for this very reason, that the appropriate forum for the examination of witnesses is the trial itself. In this context we place on record our view that the existing provisions for the taking of evidence by commissioner are an inappropriate dilution of the right of an accused to a fair trial.

Miscarriages of Justice Organisation, written submission.

In oral evidence, however, Euan McIlvride, representing the Miscarriages of Justice Organisation, drew a distinction between child witnesses, where he saw a rule in favour of pre-recording as appropriate, and adult deemed vulnerable witnesses. His concerns in relation to adult deemed vulnerable witnesses are discussed in more detail below.

In response to the concerns raised about the potential for miscarriages of justice, the Lord Justice Clerk emphasised that the process would still be subject to judicial oversight:

The safeguards are essentially the same as those that would apply if the child was giving evidence at trial. The commissioner is a High Court judge and is invested with the same powers; they are in control of proceedings and can deal with any difficulties that might arise in questioning. Equally, the commissioner protects the interests of the accused, just as the judge in a trial would.

Justice Committee, Official Report 18 December 2018, col. 4.

A similar point was made by the Cabinet Secretary for Justice in his closing evidence to the Committee, during which he also emphasised that the defence would continue to be able to test the evidence through cross-examination.1 However, he indicated that he would keep an “open mind” on any amendments proposed by the Faculty or others to ensure the fairness of the trial process.2

Phased implementation of the rule requiring pre-recording

As set out earlier, the rule in favour of pre-recording in section 1 of the Bill applies only to child witnesses in the most serious cases. Moreover, the commencement provisions in section 11 of the Bill allow for this rule to be implemented in stages.

Section 1 of the Bill would allow the rule to be extended to child witnesses giving evidence in cases involving other offences prosecuted under solemn procedure. This could include extending the rule to all children (other than child accused) giving evidence in solemn cases. Section 3 of the Bill would allow extension of the rule to adult deemed vulnerable witnesses giving evidence in solemn cases. Any extension of the rule to other child and adult deemed vulnerable witnesses would be done through regulations, subject to the affirmative procedure.

The Bill as currently drafted would not allow the rule to be extended to offences prosecuted under summary procedure, or to other existing categories of vulnerable witness.

The Scottish Government’s intention is to take a phased approach to the implementation of the rule in favour of pre-recording. Towards the end of the Committee’s scrutiny of the Bill, the Government provided an outline draft implementation plan. This envisages the first two phases of implementation being as follows:

from January 2020: for child witnesses (including complainers) aged under 18 in High Court cases involving an offence(s) specified in section 1 of the Bill

from July 2021: child complainers only aged under 16 in sheriff and jury cases involving an offence(s) specified in section 1 of the Bill

The outline plan does not set out intended dates for future phases, but suggests that these phases will be implemented in the following order:

other child witnesses aged under 16 in sheriff and jury cases involving an offence(s) specified in section 1 of the Bill

child witnesses (including complainers) aged 16 and 17 in sheriff and jury cases involving an offence(s) specified in section 1 of the Bill

adult deemed vulnerable witnesses in High Court sexual offence cases

all remaining adult deemed vulnerable witnesses in High Court cases

The implementation plan does not indicate if and when the rule in the Bill will be extended to other offences.

As noted above, the Scottish Government’s justification for this phased approach is that the introduction of a rule requiring pre-recording will be a significant change for the criminal justice system. It considers that the initial focus should be on those witnesses who are the most vulnerable – i.e. child witnesses in the most serious cases – before expanding the rule to other child or adult deemed vulnerable witnesses.

In a letter accompanying the Government’s outline implementation plan, the Cabinet Secretary for Justice stated:

It is crucial that commencement and roll out of provisions in the Bill is undertaken in a managed and effective way to ensure that the intended benefits are delivered to the individuals involved in these most serious cases. … The danger in rolling out too quickly is that it overwhelms the system, commissions do not operate as they should, which in turn means that the aims of the Bill to improve the position for the most vulnerable witnesses will not be met.

Scottish Government, supplementary written submission.

The Cabinet Secretary also emphasised the need to ensure that there is a “suitable period of evaluation and monitoring before moving to commence the next stage of implementation”.1

Overall views on a phased approach

Overall, evidence to the Committee supported a phased approach to implementation of the rule requiring pre-recording, including the initial focus on child witnesses in the most serious cases.

Reasons advanced in favour of this approach included the resource implications of the Bill, as well as the cultural and practical shifts that would be required.

For example, the COPFS supported a phased approach starting with child witnesses in the High Court for offences listed in the Bill. Its written submission stated:

This reform will have a very marked impact on the organisation of the business of the criminal courts. It is inevitable that the rule will require to be implemented in a phased manner. Deliberate decisions should be taken sequentially over time to extend the presumption to additional categories of witnesses. Those decisions can only safely be made once the necessary resources are in place – not merely the facilities to record evidence on the scale envisaged, but also the resources to provide the capacity in the system on the part of the Crown, the court and the defence (via the Scottish Legal Aid Board). Phasing will allow the system to absorb change while minimising risk both to the system and to individual cases. It will also enable any difficulties which arise in the operation of the rule to be identified and addressed before the rule is extended.

Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service, written submission.

Similar sentiments were expressed in other written submissions, including from the Faculty of Advocates, the Law Society of Scotland, Police Scotland, the Senators of the College of Justice and Social Work Scotland.

In supporting a phased approach, the SCTS also emphasised the resource implications of the Bill, as well as other changes that would be required in practice:

The long-term changes envisaged by this Bill will require significant shifts in legal thinking, practice, technology and infrastructure. It is essential that all those participating in the criminal justice system are given the time, support and resource to make the adjustments necessary. It is very sensible to plan for a phased rollout so that the growth in the use of pre-recorded evidence does not simply overwhelm the capacities of our staff, the judiciary and the court estate, as well as the prosecution (COPFS), defence agents and advocates, and associated services such as victim support.

Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service, written submission.

The SCTS suggested a phased approach was necessary for a number of reasons, including the need to:

create specialist venues for pre-recording evidence

develop appropriate technical capabilities to record, store and play such evidence

deliver training for the judiciary, prosecutors, defence agents and court staff

ensure that the new approach is implemented in a way that genuinely improves the experience for witnesses1

This latter point was emphasised by other evidence to the Committee, which stressed the need for appropriate monitoring and evaluation. This was also seen as necessary to learn lessons for extending the rule to other categories of witness, and to ensure that sufficient resources are in place for any such extension.2

Extending the rule requiring pre-recording

Timetable for implementation

Whilst acknowledging the need for a phased approach, some evidence argued that more clarity was needed as to the timetable for extending the rule in favour of pre-recording. Mhairi McGowan, representing ASSIST, told the Committee she was concerned that “if there is no set timetable that Parliament can properly consider, we will lose the benefits of extending the approach”.1

Similarly, Colin McKay of the Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland argued that there needed to be a commitment to extending the rule “within a reasonable timeframe”.2 He went on to say:

There is a danger that, once we get into the difficulties of implementation, some of the energy and commitment will get lost. People get into the mentality of thinking, “Let’s just get this one thing done and then we’ll see where we are”. It is important that the committee and the Parliament continue to hold the Government to account on a clear framework for action.

Justice Committee, Official Report 27 November 2018, col. 44.

Evidence from the COPFS, however, emphasised the need for flexibility in any implementation plan, suggesting that “a fixed implementation timetable would be incompatible with managing unforeseen challenges”.3

As discussed above, the Scottish Government has since provided an outline implementation plan, although this does not set out when the rule will be extended to other offences, or to adult deemed vulnerable witnesses. In oral evidence, the Cabinet Secretary told the Committee:

We need to have a degree of flexibility. In my implementation plan, which I forwarded to the Committee, dates are attached to some of what we are looking to do, but not to everything. The reason for this is that I want to get things right instead of just giving you an arbitrary date. We need to evaluate and monitor.

Justice Committee, Official Report 8 January 2019, col. 5.

Child accused

Under the provisions of the Bill, the proposed rule on pre-recording evidence would not apply to child accused. As noted earlier, the Scottish Government’s view is that pre-recording the evidence of a child accused raises complex issues and could prejudice the accused’s right to remain silent. 1

Evidence from some children’s organisations suggested that the rule should be extended to child accused. Children 1st, for example, emphasised that accused children are “extremely vulnerable”. It argued:

Accused children have the same rights to be heard and to be protected from harm within the criminal justice system as children who are victims or witnesses. What we know about eliciting consistent, reliable accounts from children’s testimony applies equally to children accused of crime as it does to child victims and witnesses.

Children 1st, written submission.

Similar points were made in the written submission from NSPCC, which suggested that the Bill should “include a commitment of a future phase fully considering the need of the child accused”.2

In its evidence, the Miscarriages of Justice Organisation suggested that introducing the provisions in the Bill without similar measures for child accused created an imbalance. Whilst accepting that more work needed to be done on this issue, it argued that the Bill should not be taken forward until measures to ensure appropriate support for vulnerable accused can also be brought forward.3

However, other evidence expressed support for the approach taken in the Bill. For example, the COPFS argued that extending the rule to child accused “could not readily be reconciled with the accused’s right to silence”.4 Similar points were made in evidence from the Faculty of Advocates and the Law Society.

In oral evidence, the Lord Justice Clerk emphasised the different status and rights of the child accused. She told the Committee:

The accused, whether they are a child or otherwise, is not required to give evidence; the decision about whether they give evidence has to be made in the context of what the evidence at the trial has been, which we will not know until the end of the trial. We might anticipate that the evidence will be A, B and C, but frequently that turns out not to be entirely accurate, and the accused has to respond to what the evidence has been at the trial. I cannot see a way in which the evidence of a child accused could be taken in advance of the trial, nor can I see how requiring an accused child somehow to do that would not be in breach of their rights.

Justice Committee, Official Report 18 December 2018, col. 13.

However, she went on to say that existing special measures which could support a child accused, such as giving evidence by live link, were currently underused.5Other witnesses agreed that more use could be made of existing special measures to assist vulnerable accused. The Committee also heard that, whilst there should not be a rule requiring pre-recording for child accused, current legislation would allow for pre-recording if appropriate in the individual circumstances of the case.

The Scottish Government told the Committee it was considering what further support could be given to child accused. On 6 September 2018, the Government and the Centre for Youth and Criminal Justice brought together a range of stakeholders to discuss this issue. A summary of the key themes that emerged from that event can be found here. Stakeholders at this event emphasised that the role of the defence is crucial in ensuring appropriate special measures are requested for child accused.

Conclusions and recommendations on the rule requiring pre-recording of evidence

The rule requiring pre-recording

The Committee welcomes the introduction of the rule in section 1 of the Bill, which would generally require child witnesses in the most serious cases to give all of their evidence in advance of the criminal trial. This is an important step forward in increasing the greater use of pre-recording, which the Committee agrees will reduce the distress and trauma caused to child witnesses as well as improve the quality of justice.

The Committee considers that the introduction of this rule must be balanced with sufficient safeguards to protect the rights of the accused. In particular, the Committee notes the concerns raised by the Faculty of Advocates and others that, unless the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service meets its disclosure obligations in good time, the defence cannot properly prepare for a commission. The Committee asks the Scottish Government to set out what steps it intends to take to address these concerns.

The Committee also heard that the current drafting of section 2(4) of the Bill, which provides that all of the child witness’s evidence may be given by way of a prior statement, might be interpreted as precluding the scope for cross-examination in such cases. The Committee asks the Scottish Government to consider whether the Bill should be amended to make it clear that this is not the intention.

Phased implementation of the rule requiring pre-recording

The Committee recognises the significant costs associated with a rule in favour of pre-recording, which are discussed in more detail later in this report, as well as the shifts in legal practice and culture which will be required. The Committee therefore agrees that a phased approach to implementation is sensible, with the initial focus being on child witnesses in the most serious cases.

Extending the rule requiring pre-recording

However, the Committee considers that section 1 of the Bill should be amended to include domestic abuse in the list of offences covered by the rule requiring pre-recording, given the trauma that children can experience in such cases. The Committee welcomes the indication from the Cabinet Secretary for Justice that he is willing to consider this extension.

The Committee also supports the extension of the rule requiring pre-recording to adult deemed vulnerable witnesses. The Committee is not persuaded that pre-recording the evidence of such witnesses will enhance their credibility with jurors. Moreover, the Committee notes that the Bill’s provisions do not alter the existing statutory definition of a deemed vulnerable witness.

The Committee recognises that the process of giving evidence can be just as distressing for witnesses in summary cases as for solemn cases. This is particularly an issue for child witnesses giving evidence in domestic abuse cases, which are often prosecuted under summary procedure. The Committee therefore recommends that more use should be made of existing provisions which allow evidence to be pre-recorded in summary cases. The Committee, however, acknowledges that extending a rule requiring pre-recording to summary cases would have significant resource implications.

The Committee heard that there would be benefits in the greater use of pre-recording for other categories of vulnerable witness, such as those who are vulnerable by reason of mental disorder. However, there does not seem to be a pressing case for extending the rule requiring pre-recording to these witnesses. Moreover, some evidence suggested that, given the range of vulnerabilities in these categories, there is a need for flexibility in the approach to evidence-taking. Nonetheless, the Committee asks the Scottish Government to consider what steps could be taken to increase the use of pre-recording for other categories of vulnerable witness where appropriate.

On balance, the Committee considers that it is appropriate that the Scottish Government will have the power to extend the rule requiring pre-recording through regulations. This should allow other child and adult deemed vulnerable witnesses to benefit from the provisions without any unnecessary delay caused by requiring further primary legislation.

It is important that there is an opportunity for sufficient parliamentary scrutiny of any extension of the rule in section 1 of the Bill. The Committee agrees that the regulations should therefore be subject to the affirmative procedure. It also recommends that the Scottish Government provide the Scottish Parliament with early notification of its intention to lay any regulations extending the rule to other offences, courts or adult deemed vulnerable witnesses. The Committee welcomes the indication from the Cabinet Secretary for Justice that he would be willing to share information gathered during the monitoring and evaluation of earlier phases of implementation, to inform the Committee’s scrutiny of any regulations extending the application of the rule. This information should be provided at the same time as the Scottish Government gives early notification of its intention to lay regulations. This would not preclude the Committee at that stage from recommending that it would be more appropriate for any extension of the rule to be provided for in primary legislation.

Timetable for implementation

The Scottish Government’s draft implementation plan provides a useful starting point for considering the timetable for extending the rule to other offences, courts and adult deemed vulnerable witness. A more detailed implementation plan should be developed as soon as possible. This should provide a clear framework which can be used to monitor progress and ensure that there is not undue delay in extending the benefits of the rule to other witnesses.

The Committee considers that any plan should build in sufficient time for monitoring and evaluation, as well as potential resulting changes such as enhancements to the technology available for pre-recording. It welcomes that this approach has been suggested in the draft implementation plan provided by the Scottish Government. The Committee heard that this would be necessary to ensure that the rule is delivering improvements in practice and to learn lessons before extending to other categories of witness. The Committee asks the Scottish Government to provide more detail on how each phase will be evaluated and how decisions will be made about future phases of implementation.

Child accused

The Committee understands why, at this stage, the rule requiring pre-recording will not apply to child accused, given the concerns raised that to do so could prejudice the accused’s right to silence and ability to respond to the evidence produced at trial. However, the Committee also heard that more needs to be done to support child accused giving evidence, particularly as these children can often be the most vulnerable. The Committee therefore welcomes the ongoing work by the Scottish Government to consider the position of the child accused and requests an update on its plans for improving the support offered.

In particular, it appears that existing special measures which could be used to support child accused, such as giving their evidence by live television link, are currently underused. The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government work with relevant justice agencies, including the Law Society of Scotland, Faculty of Advocates and the Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service, to consider what steps could be taken to increase the use of such measures for child accused. This could include, for example, enhanced guidance or training for defence solicitors and advocates.

Reforms to the process of taking evidence by a commissioner

As set out earlier, section 5 of the Bill provides for various reforms to the existing process for taking evidence by a commissioner. These provisions would apply in all cases where the evidence of a vulnerable witness is to be taken by a commissioner.

The revised High Court practice note, which came into effect in May 2017, included a requirement for there to be a procedural hearing in advance of taking evidence by a commissioner. Section 5 of the Bill puts this requirement for a procedural hearing – referred to in the Bill as a ground rules hearing – on a statutory footing. The purpose of this provision is to ensure that in all cases where evidence is to be taken by a commissioner, the parties are prepared and the issues set out in the current practice note are considered.1

Section 5 provides that the ground rules hearing can take place separately or at the same time as another procedural hearing in the case, such as the preliminary hearing. The Policy Memorandum notes that it is expected that the ground rules hearing will, in High Court cases, continue to be dealt with at the preliminary hearing, as that approach has been working well under the practice note.2

Section 5 of the Bill also lists matters which must be considered at the ground rules hearing. These include:

the length of time the parties expect to take for questioning, including any breaks that may be required

the form and wording of the questions to be asked of the witness

the use of a supporter

steps that could reasonably be taken to enable the witness to participate more effectively in the proceedings

The Policy Memorandum states:

The Bill does not list all the matters contained in the Practice Note but it requires that (in addition to considering the matters listed in the Bill), consideration must be given to any other matter that could be usefully dealt with before the proceedings before the commissioner take place. This allows some flexibility. If the Practice Note is modified to include new matters, these are likely to be matters that could be usefully dealt with at ground rules hearings.

Policy Memorandum, paragraph 82.

The Bill also provides that, where reasonably practicable, the same judge or sheriff should preside over both the ground rules hearing and the commission hearing.

In relation to the timing of commissions in solemn procedure cases, the Bill allows for the possibility of a commission taking place before an indictment has been served on the accused.i

Views on the requirement for a ground rules hearing

The Committee heard strong support for the provisions in section 5 of the Bill on ground rules hearings, with evidence emphasising the importance of these hearings in ensuring that the process for taking evidence by a commissioner works effectively. The SCTS, for example, noted in its written submission:

There is extensive evidence, particularly from England and Wales, that a “ground rules hearing” is a necessary part of the process, helping to ensure the commission itself is as effective and efficient as possible for all parties.

Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service, written submission.

Similar points were made in many other submissions including those from the COPFS, Faculty of Advocates, Senators of the College of Justice, the Sheriffs’ Association and Victim Support Scotland. This evidence also supported the approach taken in the Bill which would allow the ground rules hearing to take place separately or at the same time as other procedural hearings.

Deciding on the questions to be asked of the witness

The Committee heard that consideration of the form and wording of questions to be asked of the witness is a crucial part of the ground rules hearing.

The SCTS stated:

That type of discussion with the judiciary in advance of a commission is essential so that the nature of questioning is agreed in advance and the right balance can be struck between a) the actual vulnerabilities exhibited by each child or adult vulnerable witness and b) the interests of justice in maintaining the right to a fair trial for the accused.

Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service, written submission.

Victim Support Scotland similarly argued:

The ground rules hearings are an effective way of ensuring that the child’s development, needs and safety are met during questioning. The need for this is clear. Research on how solicitors examine and cross examine children in Scotland shows that solicitors do not alter their questioning technique when questioning a child, regardless of the child’s age. This highlights that more needs to be done to protect children from inappropriate, misleading and/or confusing questions.

Victim Support Scotland, written submission.

Given these benefits, Victim Support Scotland argued that ground rules hearings should be extended to all cases involving child and vulnerable witnesses, regardless of the way in which their evidence is to be taken. This approach was also advocated in the submissions from the Scottish Children’s Reporter Administration and Social Work Scotland.

Other evidence suggested that the provisions on ground rules hearings should go further in promoting scrutiny of the questioning of vulnerable witnesses.

A submission from the Senators of the College of Justice noted that, for ground rules hearings to be effective, “it is essential that the defence communicate the lines of questioning to the court” and that this should be reflected in the Bill.1

Whilst the Scottish Children’s Reporter Administration argued:

The legislation should specifically require the prosecutor and the accused to submit the list of proposed questions to the judge or commissioner in advance. This will promote a practice of judicial scrutiny. This is the norm in English proceedings where pre-recording of evidence is to take place, and has been described as the success of the system. It is difficult to see any argument against proactive judicial scrutiny of questioning other than an unwillingness to change culture and practice. As in England, alternative questions can be suggested depending on possible witness responses.

Scottish Children's Reporter Administration, written submission.

During its visits to the High Court, the Committee explored whether a requirement to provide questions at the ground rules hearing would impact on the ability to deal with any unexpected evidence that emerged at the commission itself. The Committee understands that, under current practice, there is some flexibility to depart from lines of questioning agreed at the ground rules hearing and, if necessary, the commissioner’s permission can be sought to ask additional questions. This approach would not be altered by the provisions in the Bill. The Scottish Government also emphasised that the Bill is not intended in any way to prevent the legitimate questioning of witnesses.2

Other matters to be considered at the ground rules hearing