Justice Committee

Stage 1 report on the Offensive Behaviour at Football and Threatening Communications (Repeal) (Scotland) Bill

Membership changes

Maurice Corry and Liam Kerr replaced Oliver Mundell and Douglas Ross on 29 June 2017.

George Adam replaced Stewart Stevenson on 26 October 2017.

Daniel Johnson replaced Mary Fee on 9 January 2018.

Executive Summary

This report sets out the Justice Committee’s consideration of the Offensive Behaviour at Football and Threatening Communications (Repeal) (Scotland) Bill (“the Bill”) at Stage 1.

The Committee took evidence on the Bill over six meetings in 2017, as well as receiving written evidence from 30 organisations and 256 individuals.

The Bill is seeking to repeal the Offensive Behaviour at Football and Threatening Communications (Scotland) Act 2012 (“the 2012 Act”) in its entirety, as well as providing transitional provisions for those currently charged with offences under the 2012 Act.

The Policy Memorandum states that the Member in charge of the Bill, James Kelly MSP, is keen for the 2012 Act to be repealed at the earliest opportunity. Accordingly, the Bill provides for repeal of the 2012 Act to come into force on the day after Royal Assent. The Bill contains some transitional provisions for those charged under the 2012 Act but not yet prosecuted and the issuing of fixed penalty notices under Section 1 of the 2012 Act.

The 2012 Act contains two offences, one involving "offensive behaviour at regulated football matches" (the Section 1 offence) and one involving "threatening communications" (the Section 6 offence).

Given the narrow purpose of the Bill, there appears to be little scope for amending it – other than the proposed commencement date and transitional provisions – should it reach Stage 2. The Bill is progressing at the same time as Lord Bracadale’s review of hate crime legislation, under which the 2012 Act is also being considered.

The Committee has made the following recommendations in the report:

The Committee notes the views held by a range of stakeholders on both sides of the debate, and appreciates that the 2012 Act evokes strong feelings among both its supporters and opponents. The Committee unanimously condemns sectarianism, hate crime and offensive behaviour and considers it unacceptable. The Committee notes the evidence from some fans' groups that this has led to strained relations between their members and the police.

The Committee also recognises that the number of football fans engaging in criminal behaviour is minimal, and welcomes the context provided by the SFA, Police Scotland and fans’ groups to demonstrate this is the case.

The Committee acknowledges the statement made by the Minister regarding the inherent tension between different freedoms. However, the Committee notes the human rights concerns raised by the Scottish Human Rights Commission and others, and urges the Scottish Government to explore how it can continue to safeguard human rights and minimise the risk of misunderstandings around the legislation and individuals’ rights.

Regardless of whether or not the 2012 Act is repealed, the Committee believes that it would be appropriate for the Scottish Government to clarify what constitutes hate crime once the position on repeal of the 2012 Act is known and Lord Bracadale's review of hate crime legislation is concluded.

The Committee notes the view of some witnesses that the Section 1 offence is not clearly drafted and that its sole focus is on football.

The Committee notes the example outlined by the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service in evidence that a lack of definition is not unusual, but also observes that the lack of a definition of dangerous driving and breach of the peace do not appear to have caused the same difficulties with understanding as is the case with the 2012 Act.

The Committee understands that the Bill seeks to repeal the 2012 Act in its entirety. However, should this repeal Bill not be passed, and the 2012 Act remains in place, the Committee is of the view that the Scottish Government should bring forward amendments to Section 1 of the 2012 Act.

The Committee understands that the Bill seeks to repeal the 2012 Act in its entirety, and notes that the measures contained within Section 6 of the 2012 Act, unlike those in Section 1, are applicable beyond a football context.

The Committee also acknowledges and accepts that repeal of Section 6 would result in no specific offence of incitement to religious hatred in Scotland. However, the Committee also notes concerns that the wording of Section 6 has inadvertently created a high threshold, which has concomitantly led to its limited use and relatively low number of convictions

The Committee notes the view of Police Scotland that the drafting of Section 6 has precluded more widespread use of its provisions to tackle threatening communications.

The Committee therefore believes that, were the 2012 Act to be repealed and in light of the forthcoming recommendations from Lord Bracadale's Review of hate crime legislation, it would be appropriate for the Scottish Government to consider how the provisions within Section 6 could be updated as part of a wider revision of hate crime legislation.

The Committee notes that there are opposing arguments regarding whether or not repeal of the 2012 Act would create gaps in the law.

The Committee concludes that repeal of the 2012 Act would have an effect with regard to extra-territoriality (with regards to Section 6) and the prosecution of certain offences on indictment. However, on balance, the Committee also concludes that repeal would not have a significant impact on the prosecution of the type of offences which the 2012 Act sought to capture in Sections 1 to 5.

Other than the offence of incitement to religious hatred covered by Section 6, the Committee is of the view that repeal would not result in behaviour or actions currently prosecuted under the 2012 Act becoming legal. The Committee is also mindful of the suggestion by Professor Fiona Leverick that sentencing aggravation provisions could be used to capture such offences in the absence of any replacement legislation.

Notwithstanding the above, should the Bill become law and the 2012 Act is repealed, the Committee considers it important that the Scottish Government and relevant stakeholders clearly communicate that offensive behaviour at football and threatening communications can still be tackled and prosecuted using other legislation and the common law. The Committee agrees with the view of Professor Leverick that a strong education campaign is required to ensure that people are aware that behaviour such as sectarian chanting is unacceptable.

Lord Bracadale's review of hate crime legislation

The Committee notes the views of many witnesses that it would be wise to wait until Lord Bracadale's review of hate crime legislation has reported in Spring 2018 before taking definitive action on the Bill (and, in turn, the 2012 Act).

The Committee is mindful that the timing of an independent review should not impinge on the Committee's role to carry out post-legislative scrutiny on any piece of legislation passed by the Scottish Parliament.

However, the Committee is also aware that the scope of Lord Bracadale's review of hate crime legislation extends beyond the 2012 Act, and that the Review itself states that its recommendations will cover both scenarios in relation to the 2012 Act so as to avoid any delay or confusion.

The Committee also accepts that the timescale for consideration and implementation of the review’s recommendations is unknown, and may take years, as has been the case in other reviews, for example, with Sheriff Principal Taylor’s review of civil litigation.

The Committee therefore believes that, while Lord Bracadale's review of hate crime legislation will be of great interest and importance to its future work, it would not be appropriate to delay consideration of this Bill while Lord Bracadale concludes his work.

The Committee notes that the 2012 Act covers many different offences and not just those resulting from sectarianism.

However, the Committee is aware that the public perception of this Act is that it primarily deals with sectarian behaviour. The scrutiny of the Bill to repeal the Act has therefore sparked a new debate on sectarian behaviour, and the Committee believes this presents an opportunity to make progress on tackling sectarianism.

The Committee considers it important that the Scottish Government gives consideration to introducing a definition of sectarianism in Scots Law, which – whether or not the 2012 Act is repealed – would help any future parliaments and governments in taking forward laws to tackle sectarianism.

Other measures for tackling hate crime and sectarianism

Regardless of whether the 2012 Act is repealed, the Committee is of the opinion that education is vital to tackling the root causes of sectarianism and offensive behaviour.

The Committee noted with interest the limited use of diversion schemes, such as that operated by SACRO, which aim to educate offenders on the effect of their behaviour. The Committee considers these schemes to be worthy of more widespread use, potentially as diversion from prosecution.

Whilst problems persist and there is more work to be done the Committee welcomes the work undertaken by football authorities to tackle sectarianism. The Committee asks the Scottish Government for an update on how sectarianism is addressed in schools and how diversion schemes for offenders in these areas can be expanded.

The Committee supports, by division, the general principles of the Billi.

The minority who voted against the general principles of the Bill are of the view that, should the 2012 Act be retained, the Scottish Government should revisit the 2012 Act and bring forward constructive amendments.

Introduction

Background to the 2012 Act

In 2011, a number of incidents during and after football matches (primarily involving Celtic FC and Rangers FC), and in the wider public domain, led to the Scottish Government organising a summit in March 2011 to discuss the impact of sectarianism and other offensive behaviouri on Scottish football and on wider society.

The intention of the summit was to assess and make proposals on certain aspects of the game in order to protect football's reputation in Scotland and beyond. The summit was attended by Scottish Ministers and representatives of the former Strathclyde Police force, Celtic FC, Rangers FC, the Scottish Football Association, the Scottish Football League and the Scottish Premier League.

At that time, the issue of sectarianism and associated behaviour at football matches had been to the fore of the debate. In addition to behaviour during football matches, a number of other serious incidents led to calls for an examination of, and response to, sectarian attitudes which pervade some sections of Scottish society.

Following the summit in March 2011, the Scottish Government issued a joint statement on behalf of those attending the summit:

Football is Scotland's national game and at its best combines pride and passion with a sense of responsibility, respect and discipline. There is absolutely no place in football for those who let the passion become violence, and the pride become bigotry, and we commit to doing all in our power to maintain the good reputation of Scottish football. No football club is directly responsible for the violence, disorder and bigotry seen on our streets and in our homes, and we condemn such acts entirely. However, we accept that as professionals and role models, those who play and coach the game do have a particular duty to ensure that their behaviour on and off the pitch sets a high standard.

We accept that those involved in football can positively influence the behaviour and attitudes of the wider community, and so do have a role in addressing the problems that affect such communities, whether that be violence or bigotry or alcohol misuse. We therefore commit to work together to ensure that however we can contribute to addressing these issues, we will. In particular, we agree on a renewed focus on tackling alcohol misuse.

Scottish Government joint statement, 8 March 2011

Following the summit, a Joint Action Group (JAG) was established to develop proposals and identify ways to deliver on the commitments agreed at the summit. The report of the JAG, published on 11 July, sets out those proposals including one to introduce an Offensive Behaviour at Football and Threatening Communications (Scotland) Bill with the intention that the Bill would be passed by the Parliament before the end of 2011.

The Offensive Behaviour at Football and Threatening Communications (Scotland) Bill ("the Offensive Behaviour Bill") was introduced in the Scottish Parliament on 16 June 2011. The Scottish Government initially indicated that it would like to see the Offensive Behaviour Bill passed and in force in time for the start of the 2011-12 Scottish football season which was due to start in July 2011. In order to achieve this, it was intended that the Offensive Behaviour Bill would be subject to emergency legislation procedure. At that time, concerns were raised about the Scottish Government's intention to progress the Bill without a full consultation and the opportunity for the Scottish Parliament's Justice Committee to take evidence from stakeholders. Bill McVicar, then Convener of the Law Society of Scotland's Criminal Law Committee said:

We understand the importance of tackling sectarianism. This is a very serious issue and one that needs both attention and action from our political leaders. However, it is because of the importance of this issue that the Scottish Government needs to allow adequate time to ensure the legislation can be properly scrutinised. It is particularly vital for sufficient time to be allowed at stage 1, the evidence gathering stage, for proper public consultation. Without this consultation there is the risk that the legislation could be passed which either does not meet its objective or is inconsistent with existing law, making it unworkable. It could also result in legislation that is open to successful challenge.

Law Society of Scotland, 17 June 2011

The then Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, the Right Reverend David Arnott, met with the then Minister for Community Safety and Legal Affairs, Roseanna Cunningham MSP, to discuss the Bill and stated:

We appreciated the opportunity to meet with the Minister on this very important issue but we remain nervous about this haste in which the Bill is being rushed through Parliament, apparently in time for the start of the football season. Whilst we are not against the ideas in this Bill, we remain unconvinced of the wisdom of this approach. The speed at which it is being rushed through means it appears to lack scrutiny and clarity. The government is rightly asking for support from across civic Scotland, but is not giving civic Scotland much time to make sure they are happy with the content.

Church of Scotland, 17 June 2011

In the Policy Memorandum to the Offensive Behaviour Bill, the Scottish Government stated that the measures in the Bill needed to be in place before the start of the 2011-12 football season to, amongst other things, begin to repair the damage done to the reputation of Scottish football and Scotland more generally by recent events and that this had curtailed the opportunity to engage in a standard consultation on the provisions in the Bill. The Government also pointed out that its plans to introduce the legislation had been discussed with a range of partners including the Association of Chief Police Officers in Scotland, Convention of Scottish Local Authorities (COSLA), the Scottish Courts Service, the COPFS and representatives of the Scottish Football Association and the Scottish Premier League.

As pointed out above, the Scottish Government initially intended to fast-track the Offensive Behaviour Bill through Parliament so that it could become law in time for the new football season in late July 2011. To do this, the Government proposed that it should be treated as an emergency bill,ii although it also proposed a gap between stage 1 (to be taken on 23 June 2011) and stages 2 and 3 (to be taken on 29 June 2011). Under the Parliament's standing orders, the procedure for emergency bills is that Parliament normally takes all three stages on the same day.

The Justice Committee took evidence on the Offensive Behaviour Bill from five panels of witnesses at two meetings on 21 June and 22 June 2011. The Committee did so in the knowledge that it would not have time to produce a report on the general principles of the Bill in time for the stage 1 debate (as would normally be the case). The Committee's intention was to take as much evidence as possible in the limited time available so as to help inform the stage 1 debate and any debate on amendments to the Bill at stages 2 and 3. The Committee also issued a call for written evidence on the Bill (necessarily with a very short deadline for responses) which was targeted at key stakeholders. In response, the Committee received 82 written submissions.

On 23 June 2011, the Parliament debated a motion to treat the Bill as an emergency bill. This was agreed to after a division. The Parliament then agreed by division to consider the Bill according to the timetable set out above. Following this, the Parliament debated the Bill at stage 1.

Shortly after the stage 1 debate, and just before the Parliament was to vote on whether to agree the general principles of the Bill at stage 1, the then First Minister Alex Salmond MSP, announced that, if the Parliament agreed to the general principles, he would propose an extended timetable for consideration of the Bill at stages 2 and 3. He indicated that this would, whilst allowing more scrutiny, enable the Bill to be passed by the end of the year. He said that he hoped that providing more time for evidence-taking on the Bill would increase the likelihood of the Parliament and wider Scottish society achieving consensus on the issues raised.

Following the First Minister's comments, the Parliament went on to approve the general principles of the Bill at stage 1 (by a majority of 103 to 5, with 15 abstentions). On 29 June, the Parliament agreed, without division, a motion not to take the remainder of the Bill as an emergency bill; that the Justice Committee be the lead committee on the Bill; and that stage 2 be completed by 11 November. Stage 2 was duly completed on 22 November 2011 and the Bill was passed at Stage 3 on 14 December 2011 with a division of 64 for (SNP), 57 against (all other parties) and no abstentions.

The 2012 Act

The 2012 Act makes provision for two new criminal offences, one involving "offensive behaviour at regulated football matches" ("the Section 1 offence") and one involving "threatening communications" ("the Section 6 offence").

The Section 1 offence

The Section 1 offence includes a number of separate elements. One is that the offending behaviour is "in relation to a regulated football match". Such behaviour can take place in the ground where a match is being held and on the day it is being held. Also covered is behaviour while the person is entering or leaving the ground or on a journey to or from the match. The same is true in relation to non-domestic premises where a match is being televised - so a person can commit the offence in, for example, a pub where the match is being televised.

The second element of the offence is that it involves behaviour that is or would be "likely to incite public disorder". Thirdly, the behaviour must be at least one of the following:

behaviour "expressing hatred of, or stirring up hatred against", a group of persons based on their religious affiliation or a group defined by reference to their colour, race, nationality, ethnic or religious origins, sexual orientation, transgender identity or disability - or against any individual member of such a group;

behaviour motivated by hatred of such a group;

behaviour that is threatening; or

other behaviour that a reasonable person would be likely to consider offensive.

Subject to these requirements, the behaviour may be "behaviour of any kind including, in particular, things said or otherwise communicated as well as things done", and may be behaviour consisting of a single act, as well as behaviour that amounts to "a course of conduct".

The Section 6 offence

The Section 6 offence consists of communicating material to another person if one of two conditions (A or B) is satisfied - although it is a defence to show that communication of the material was reasonable in the circumstances.

Condition A is that the material "consists of, contains or implies a threat, or an incitement, to carry out a seriously violent act" against a person or persons; that the material or communication of it "would be likely to cause a reasonable person to suffer fear or alarm"; and that the person communicating the material intends to cause fear or alarm or is reckless as to whether that is the outcome.

Condition B is that the material is threatening and is communicated with the intention of stirring up hatred on religious grounds. Condition B requires intent (to stir up hatred on religious grounds), in contrast to Condition A where recklessness as to whether the communication concerned would cause fear or alarm can be sufficient for that condition to be met.

Further provision makes clear that the "material" means anything capable of being read, looked at, watched or listened to (for example, photographs and audio or video recordings as well as text); and that material can be communicated by any means other than unrecorded speech.

Committee consideration of the Bill

On 27 July 2016, James Kelly MSP lodged a proposal for a Member's Bill which seeks to repeal the 2012 Act in its entirety. Mr Kelly also published a consultation on his Bill which closed on 23 October 2016. Mr Kelly proposed the repeal to the 2012 Act on the basis that the legislation was flawed on several levels including its illiberal nature, its failure to tackle sectarianism, and the existence of other charges which the police and prosecutors could use to tackle the behaviour in question. The Member's Bill was introduced by James Kelly MSP on 21 June 2017.

The Bill was allocated to the Justice Committee for Stage 1 scrutiny of the general principles. The Committee issued a call for evidence on the Bill shortly after it was introduced. 286 responses (including supplementary submissions) were received, of which 59 were published anonymously. The Committee also received some correspondence during its Stage 1 scrutiny which related to oral and written evidence.

The Committee took public evidence on the Bill at six meetings between September and December 2017. A list of witnesses for those meetings is set out in Annex A.

The Committee is grateful to all those who provided oral and written evidence on the Bill.

Call for written evidence

In total, the Committee received 286 submissions to its call for evidence. Of these 286 submissions, 30 were from organisations and 256 were from individuals, of whom 59 requested anonymityi. Several organisations provided supplementary submissions following oral evidence sessions. A list of those who provided written evidence is provided at Annex B.

Of the 286 submissions, 227 were in favour of repeal of the 2012 Act, one was in favour of repeal of sections 1-5 only, 48 were against repeal, and 10 expressed another view.

Summary of reasons for repealing the 2012 Act

Those who provided written evidence gave a number of reasons for repealing the 2012 Act, these are summarised as follows:

The 2012 Act is not necessary as UK and Scottish legislation already exists which can be used to effectively deal with sectarian behaviour or threatening communications. Examples given include breach of the peace, provisions in the Communications Act 2003 , Section 74 of the Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 2003 and Section 38 of the Criminal Justice and Licensing (Scotland) Act 2010.

An example given is that in 2015-16, the 287 charges which were brought under Section 1 of the 2012 Act could have been prosecuted under pre-existing legislation or at common law (for example, breach of the peace).

A criminal conviction is too extreme a measure to tackle sectarian behaviour which is exhibited by a minority of people attending football matches. Other methods could be more effectively used to change behaviour, for example workshops run by charities such as Nil by Mouth and SACRO.

Football clubs should do more to control how their supporters behave, and be held accountable for what happens when their fans attend matches. A form of strict liability should be introduced for professional football clubs in Scotland.

The low number of prosecutions shows that the legislation is not necessary.

The 2012 Act has not tackled sectarianism or hate crimes. A strategy covering a much broader spectrum is required to tackle the issues of bigotry and sectarianism in society, which includes education and community engagement.

The 2012 Act is unfair and unjust as it discriminates against football supporters, especially young supporters. If behaviour is criminalised, it should be a crime no matter the setting.

It is subjective, as the 2012 Act is unclear about what behaviours are considered 'offensive'. This leaves police officers to determine what is offensivei.

It has had a negative impact on the relationships and trust between football supporters, football clubs, and the police.

Repeal of the 2012 Act should come into force with immediate effect and cases which have not been concluded should be dropped and previous convictions quashed, as a law that only applies to football fans should not have been enacted.

Responding to increases in online threats or hate behaviours is something that extends far beyond football and therefore, if the Communications Act 2003 or Section 38 of the Criminal Justice and Licensing (Scotland) Act 2010 is insufficient, separate legislation should be pursued to deal with this.

The impact of the Act on freedom of speech and political expression.

Summary of reasons for retaining the 2012 Act

Those who provided written evidence gave a number of reasons for retaining the 2012 Act, these are summarised as follows:

Repealing Sections 1-5 would reactivate concerns about alternative legislation covering issues such as offensive behaviour. For example, some of the offensive songs reported by Police Scotland under Section 1 of the 2012 Act have not been tested under the legislation which pre-dates the 2012 Act. With regards to Section 6 there is some behaviour which may not be prosecuted under any other provisions, e.g. the extra-territoriality provisions.i The tests applied and the maximum sentences that could be applied will differ.

Repealing Section 6 would create a gap in criminal law, as unlike the rest of the UK and Ireland, Scotland would not have a specific offence for issuing threats intended to incite religious hatred. This may leave prosecutors less able to secure convictions for certain crimes with a religious element.

The 2012 Act strengthens existing law by removing the requirement for COPFS to prove that the accused’s behaviour would cause fear or alarm to a reasonable person, as required for breach of the peace and Section 38 of the Criminal Justice and Licensing (Scotland) Act 2010.

Section 6 of the 2012 Act should be expanded so that the threatening communications provisions are able to deal with all forms of on-line abuse. Some respondents indicated that hateful on-line communications have increased.

Repealing the 2012 Act without a replacement would send out the wrong message about acceptable behaviour and could impact negatively on public confidence in reporting incidents of hate crime. The 2012 Act has raised awareness of hate crimes and provides an additional tool in prosecuting these of type of offences. Details of what will replace the 2012 Act should be provided before repeal.

Respondents suggested that instead of repeal the 2012 Act should either be: kept; used more and consistently enforced; amended to deal with any flaws; extended to include offensive behaviour in other contexts and extended to cover all of the protected characteristicsii; or replaced.

Sections 1 to 5 of the 2012 Act should be extended to include other settings, such as marches. A number of respondents gave the example of recent marches in Glasgow where it appeared as though the police did not arrest those singing sectarian songs. Another example provided was of protestors holding perceived hateful views attempting to stop artistic performances.

Others suggested that the current Hate Crime Legislation Review might allow the 2012 Act to be considered in the context of all hate crime legislation, and to await its outcome and recommendations, expected in early 2018.

A number of respondents pointed to prosecution and conviction rates as being a reason for retention of the 2012 Act.

The 2012 Act has tackled sectarianism. It has changed public opinion and improved the way people conduct themselves at football matches and the atmosphere at matches, making it more ‘family-friendly’ and less intimidating. For example, there has been a reduction in mass offensive singing.

Legislation is necessary as football fans, clubs, and authorities have not demonstrated that they are able or willing to self-regulate. Fear of prosecution is the only way to deal with sectarian behaviour.

Repealing the 2012 Act will make it more difficult to collect and provide data on football-related crimes.

Oral evidence sessions

The Committee took evidence from eight panels of witnesses across six evidence sessions. Details of these witnesses and the dates they gave evidence can be found in Annex A.

Outreach work

To further inform its scrutiny, the Committee agreed to undertake a number of visits to football matches as part of its information-gathering in relation to this Bill. This was an approach taken in 2011 as part of the Stage 1 scrutiny of the original Bill, as a useful tool to understand the context within which the proposed legislation would operate, and a way for Members to discuss the handling of such events with police officers and to witness how such events are policed.

Members attended three fixtures in September and October 2017 – Rangers v. Celtic on Saturday 23 September 2017, Hibs v. Hearts on Tuesday 24 October 2017, and Hearts v. Rangers on Saturday 28 October 2017. As well as observing the pre- and post-match policing arrangements and speaking with club and league officials, the visits provided an opportunity to understand the crowd dynamics and the challenges faced when policing high-profile matches.

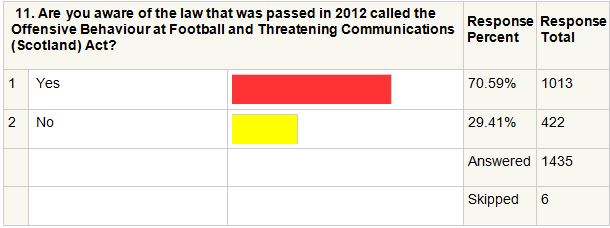

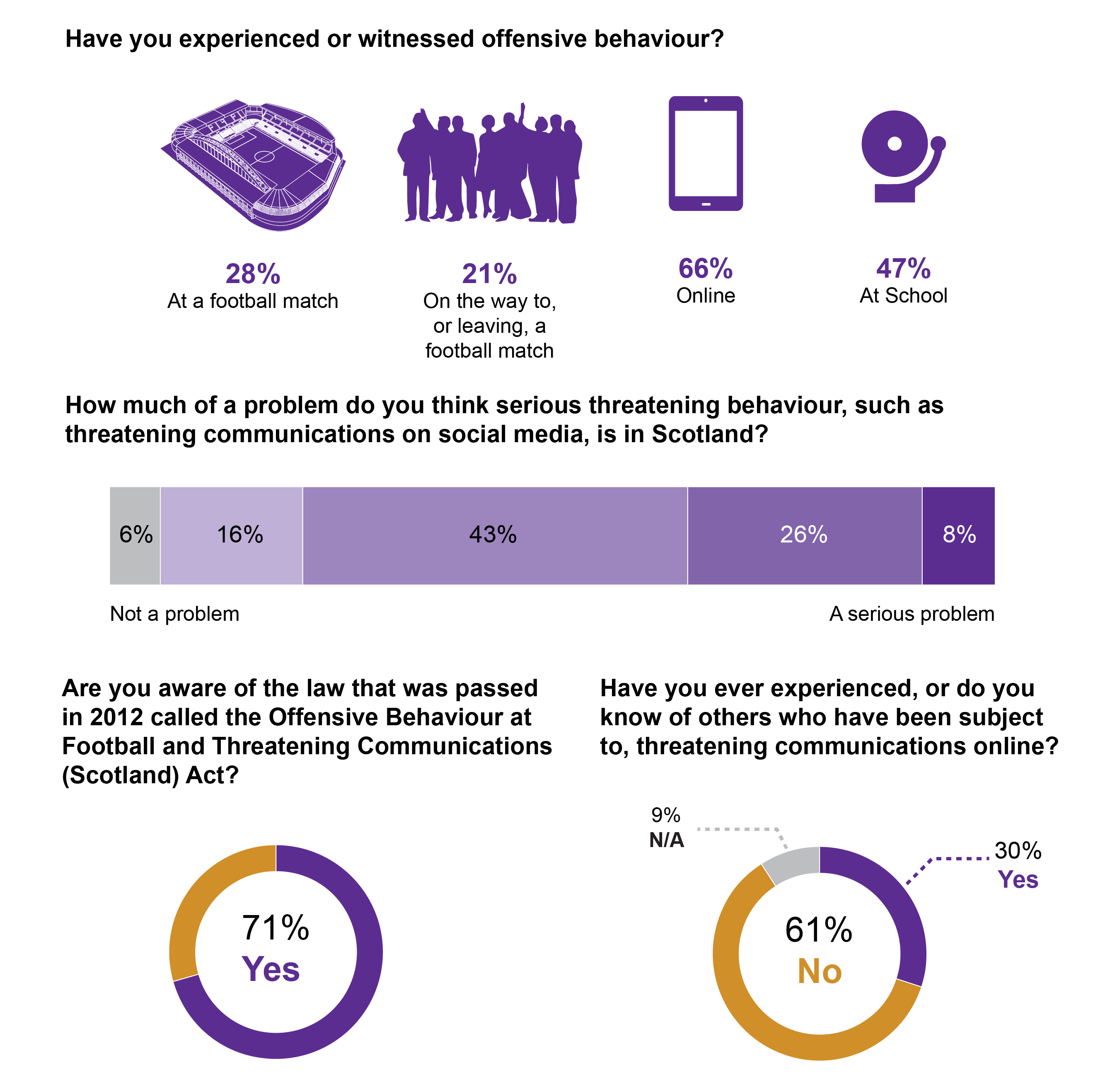

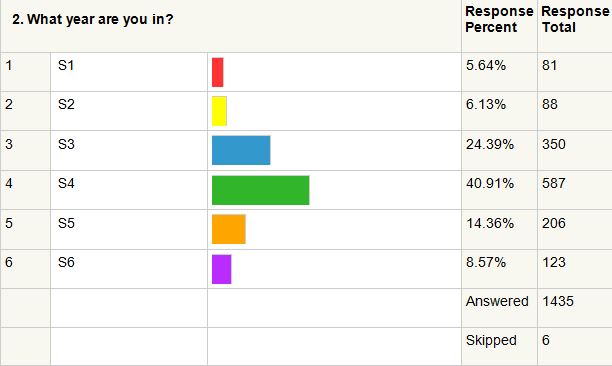

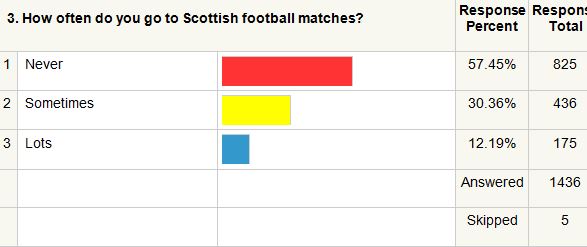

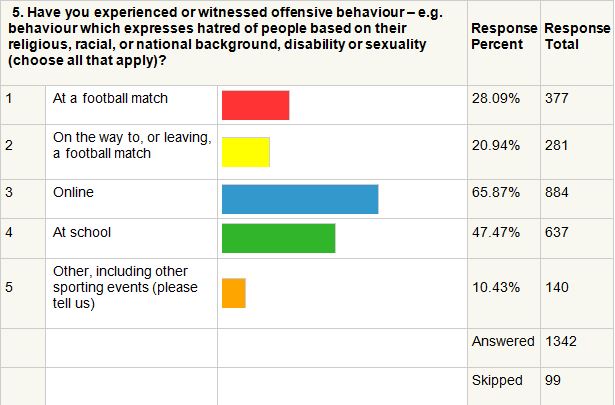

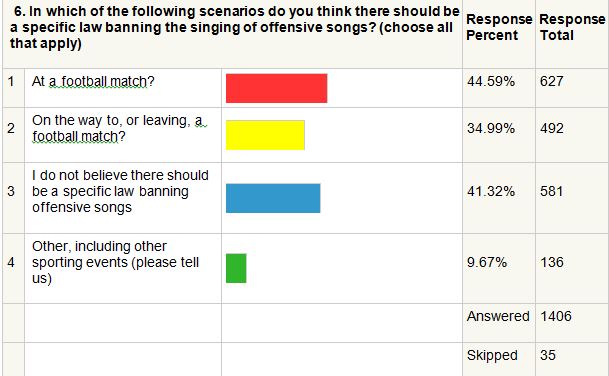

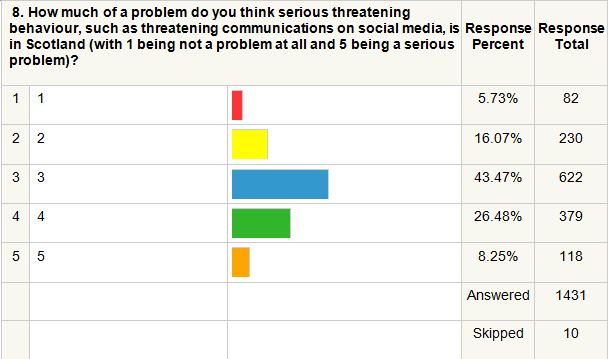

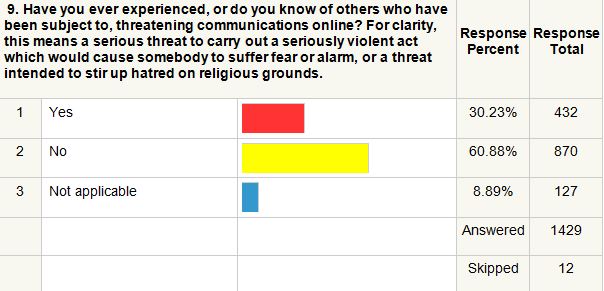

The Committee also agreed to gather the views of young people on issues related to the proposal to repeal the 2012 Act through the use of a school questionnaire. An on-line questionnaire was sent to all 364 secondary schools in Scotland and issued to the 19 secondary schools who visited the Scottish Parliament in September. The pupils were given a short activity which provided them with an overview and context of the Offensive Behaviour at Football and Threatening Communications (Scotland) Act 2012 before being asked to complete the on-line questionnaire.

The questionnaire contained 11 questions and received 1441 responses. A summary of the questionnaire’s findings, as originally provided in public Committee papers, is contained at Annex C.

The Bill

The Bill is in seven sections.

Section 1 - Repeal of the 2012 Act

Section 1 repeals the 2012 Act in its entirety, with effect from the day after the Bill, if passed, receives Royal Assent (see Section 6).

Section 2 - Offences

Section 2 deals with the effect of repeal on the ability of the courts to convict people for offences under the 2012 Act.

Subsection (1) includes provisions for no further convictions of the criminal offences in Sections 1 and 6 of the 2012 Act on or after Royal Assent.

The explanatory notes for the Bill state that:

This involves some departure from the default provision that is set out in Section 17 of the Interpretation and Legislative Reform (Scotland) Act 2010. Section 17 states that repeal of an Act of the Scottish Parliament does not affect liability to a penalty for an offence committed prior to repeal, and that the repealed Act continues to have effect for the purpose of investigating an offence, bringing or completing proceedings and imposing a penalty. Under the default (Section 17) arrangements, in other words, it would continue to be possible to convict people for a 2012 Act offence for an indefinite period after the Act was repealed, so long as the behaviour that constituted the offence took place before the date of its repeal. Under section 2(1), by contrast, a person who carried out behaviour of the sort criminalised by the 2012 Act can, from the date the repeal takes effect, no longer be convicted of a 2012 Act offence. (This does not, however, prevent the person being convicted of another offence constituted by the same behaviour, such as a breach of the peace).

Section 2(1) is subject to subsection (3), which allows for specific exceptions related to appeals. These are explained further below.

Subsection (2) includes provisions for application to new prosecutions brought following appeal, subsection (3) deals with continued possibility of conviction following Crown appeal against acquittal and subsection (4) deals with limitation of subsection (3) to pre-repeal acquittals.

Section 3 - Transitional and savings provisions

Section 3 makes transitional provision in respect of people alleged to have committed such offences but not convicted at the time of repeal, and saves the 2012 Act for a number of purposes, including sentencing of those convicted before repeal, and appeals.

Section 4 - Fixed penalties

Section 4 repeals a provision relating to fixed penalties inserted by the 2012 Act into the Antisocial Behaviour etc. (Scotland) Act 2004 ("the 2004 Act"). The Bill, by repealing the 2012 Act, removes (from the relevant date) the ability to issue any further fixed penalty notices for 2012 Act offences. Section 4 is a consequential provision to repeal the entry in Section 128 of the 2004 Act. This is explained more fully in paragraph 83.

Section 5 - interpretation

Section 5 provides definitions of the key terms "High Court" and "relevant offence" as they appear in the Bill.

Sections 6 and 7 - Commencement and Short title

Sections 6 and 7 deal with commencement and short title.

The Member's intention is for the 2012 Act to be repealed, in its entirety, from the day after the Bill (if passed) receives Royal Assent.

Committee Scrutiny

As the Bill seeks to repeal a previous Act, the Committee’s Stage 1 scrutiny focused to a large extent on the merits of the 2012 Act and could be considered a form of post-legislative scrutiny. This report therefore summarises the views of witnesses and those who responded to the Committee’s call for evidence on the 2012 Act and what effect repeal would have on the law, football fans, and wider society.

When taking evidence from witnesses, the Committee covered the following main issues:

Witnesses' views on repeal of the 2012 Act, and what outcomes would arise from repeal or retention;

The efficacy of the Section 1 offence and its use by police and prosecutors;

The efficacy of the Section 6 offence and its use by police and prosecutors;

Whether repeal would create a gap in the law;

How Lord Bracadale’s review of hate crime legislation would interact with the legislation, whether or not it is repealed; and

Whether the 2012 Act had tackled sectarianism.

Views on repeal

Views of witnesses

The Committee recognises that there are strong and conflicting views on whether the 2012 Act should be repealed, whether it had achieved its intended purpose, and the message that would be conveyed by repeal. These views were clearly expressed in both oral and written evidence.

James Kelly MSP, the Member in charge of the Bill, summarised his view that the Act was “discredited”, adding that:

It unfairly targets football fans, it is not an effective piece of legislation and it is not achieving the outcomes that it set out to achieve.

Justice Committee, Official Report 12 December 2017, Col. 34

In the first evidence session on the Bill, the Committee took evidence from a number of supporters’ groups. When asked about the message that would be sent by repealing the 2012 Act, Paul Quigley of Fans Against Criminalisation reported the following:

Repealing the Bill [sic] would send the message that football fans will no longer unfairly and unduly be criminalised as they have been under the 2012 Act, in a specific way that people in wider society are not… A Rangers fan was arrested for holding a banner that simply said, “Axe the Act.” A Motherwell fan was arrested, held in Greenock prison for four days and then convicted of singing a song that simply included profanity about a rival team. I do not think that that is worthy of a criminal conviction—it is not proportionate.

Justice Committee, Official Report 3 October 2017, cols. 37 - 38

This view was echoed by Paul Goodwin of the Scottish Football Supporters’ Association (SFSA), who told the Committee that:

A lot of the problems with the 2012 Act are down to the horrific public relations right from the start, when we talked about emergency legislation coming in. Fans of many clubs do not understand why the legislation was introduced in the first place, they do not understand the benefit of it, and they feel—rightly or wrongly—targeted.

Justice Committee, Official Report 3 October 2017, col. 38

However, Mr Goodwin’s SFSA colleague, Simon Barrow, cautioned:

We are conscious in presenting our evidence to the committee that fans have different opinions. According to our research, the great majority of fans have severe questions about or are opposed to the Act; others are concerned about the issues that the Act is intended to address. We acknowledge that the Act’s intention is good. The behaviours need to be challenged, and fans have to be central to doing that.

Justice Committee, Official Report 3 October 2017, col. 40

In its written evidence to the Committee the Scottish Government provided details of the YouGov poll that it had commissioned in 2015, which found that:

a clear majority of respondents (82%) agreed sectarian singing or chanting at football matches is offensive and that a similar proportion (83%) supported laws to tackle offensive behaviour at and around football matches. 80% of those surveyed also directly supported the Act.

Scottish Government written submission, Annex B, paragraph 13

Andrew Jenkin of Supporters Direct Scotland (SDS) referred the Committee to a survey of 12,000 supporters undertaken by SDS, to which 71% of respondents supported repeal of the 2012 Acti. He also stated:

Our organisation does not believe in football-specific legislation, so we support the earlier proposal about widening this out not just to sport, which would criminalise sport fans, but to the whole of society. That would be a step forward. You cannot have legislation that applies to one specific sector of society; that is grossly unfair.

Justice Committee, Official Report 3 October 2017, col. 51

The Committee heard a similar argument from the Scottish Football Association (SFA)'s Stewart Regan, who took issue with the specific targeting of football matches:

The key point that I would like to make in this evidence session is that football has been targeted and singled out, and a piece of legislation has been put in place that focuses exclusively on football. No other sport has that, and no other element of society has that. Over the past 24 hours, when I was preparing for this evidence session, I looked back at the music industry and identified that, between 2004 and 2013 at T in the Park, there were 3,600 incidents, three attempted murders, three drug-related deaths, 10 sexual assaults, one abduction and 2,000 drug offences. A summit was not called after T in the Park events and no emergency legislation was put in place. Football has been targeted, and many of the issues that the Act sought to address can be addressed by other legislation.

Justice Committee, Official Report 7 November 2017, col. 26

The only football club to provide written evidence was Celtic Football Club, which supported repeal of Sections 1 to 5 of the 2012 Act on the basis of:

significant concerns in relation to the potential for discrimination against football supporters and for confusion in applying and enforcing the Section 1 offence.

Celtic Football Club written submission, page 4

Dr John Kelly, Lecturer in Sport Policy, Management and International Development, University of Edinburgh reiterated his support for repeal:

I, too, support the repeal of the 2012 Act, because I think that some of the issues that were warned about when the original Bill was considered have come to fruition.

Justice Committee, Official Report 14 November 2017, col. 36

Not all of those who were critical of the 2012 Act supported repeal. Andrew Tickell, Lecturer in Law at Glasgow Caledonian University held the position that the 2012 Act can be amended:

I would argue that striking this Act completely aside is like using a sledgehammer for a task for which a scalpel is better devised, particularly in the context of something that a number of the witnesses from whom you have heard have mentioned, which is Lord Bracadale’s on-going review of hate crime legislation… I am not sure that that Act of Parliament is an unvarnished success from the Scottish Government’s perspective. I am not sure that the Act has been a great triumph but, despite all my reservations, I believe that we can fix it. It is easy for the Scottish Government to do that if it chooses to do so, but thus far there is no evidence that the Scottish Government wants to amend the Act, which I find somewhat disappointing.

Justice Committee, Official Report 14 November 2017, cols. 38 and 46

Some witnesses from groups representing people with protected characteristics opposed repeal of the 2012 Act, with concerns about the message sent by repeal contributing to their position. Colin Macfarlane of Stonewall Scotland made this point repeatedly during evidence, stating:

Repealing the Act without putting anything in place would be damaging—it would send a negative signal to LGBT people. Most LGBT people will not be watching today’s meeting and will not pore over the Official Report or look at the intricacies of the different elements of the Act, but they will see a headline that says that the Act that potentially protects them at football matches has gone. That would lead to a lack of confidence...

As I mentioned, people often do not know about the intricacies of the legislation that does and does not cover them, but they know that, if they go to a football match and hear homophobic chanting or if somebody throws homophobic, biphobic or transphobic abuse at them, the Act will protect them. The bit that we support is the principle of the Act.

Justice Committee, Official Report 24 October 2017, cols. 9 and 13

Rev. Ian Galloway of the Church of Scotland Church and Society Council made a similar point:

We think that there is a danger of sending the message, by the simple repeal of the Act, that we are not taking seriously enough such behaviours and attitudes, or society’s need to say that those behaviours and attitudes are unacceptable.

Justice Committee, Official Report 7 November 2017, col. 3

These views were noted by the Minister for Community Safety and Legal Affairs, Annabelle Ewing MSP (“the Minister”), who stated:

I seriously fear that repealing the Act without a viable alternative would send entirely the wrong signal and, as I have said, a number of organisations have made that point because they are concerned about the risk of that happening—it might be more likely than not. I accept the concern of many organisations, such as Stonewall, the Equality Network, the Scottish Council of Jewish Communities, the Church of Scotland, and Victim Support Scotland, that when the incidence of hate crime has increased in different areas, particularly online, it would send entirely the wrong signal.

Justice Committee, Official Report 5 December 2017, col. 17

However, some other groups, such as Coalition for Racial Equality and Rights (CRER), supported repeal:

We did not offer our support to the Offensive Behaviour at Football and Threatening Communications (Scotland) Act, as we were concerned about the duplication of legislation the Act created and its limited impact outwith football. Five years on, we remain unconvinced that the Act is necessary, and believe that it creates confusion and double-standards within hate crime policy and legislation.

CRER, written submission

Black and Ethnic Minority Infrastructure in Scotland (BEMIS), which provided both written and oral evidence, also supported repeal, stating that it remained:

deeply sceptical that the Act has contributed to challenging hate crime.

BEMIS, written submission

James Kelly MSP made the point that the message being sent by the current legislation could be considered to be mixed:

What we have with the legislation is a disjointed approach. We do not have full support from political parties. We do not have full support from legal organisations. We do not have full support from football supporters and football clubs. The legislation has been called into question by human rights groups. One commentator described it as the worst piece of legislation that has ever been passed by the Scottish Parliament. The fact that opinions on the legislation are so divided reinforces that view. We are not, therefore, sending a strong message.

Justice Committee, Official Report 12 December 2017, col. 37

The Minister provided the Committee with a summary of the Scottish Government’s position:

There are three principles that underpin our position in relation to the Act. The first is acceptance that there is a problem with behaviour at and associated with Scottish football. Offensive singing and chanting are not a feature of any other sporting events. The vast majority of football fans are well behaved, but the fact that we continue to regularly hear offensive singing and chanting clearly tells us that there is a problem that needs to be dealt with. Football is not an island on its own where people are free to do as they choose without any need to consider the wider impact of their behaviours. Aggressive behaviour that is deemed acceptable at football will simply be carried into other areas of life. The second principle is that action and interventions are required to tackle all social problems. Offensive behaviour at football will not simply disappear on its own. Football clubs and authorities have had decades to tackle the issue and have failed to take effective action to bring it under control. The third principle is that although it is not in itself a panacea, legislation is needed. Legislation sets the standards for what is and is not acceptable in society, and it has an important role in tackling offensive behaviour at football. Outright repeal is not favoured by those who represent vulnerable minority communities and it is not favoured by the Scottish Government.

Justice Committee, Official Report 5 December 2017, col. 9

Anthony McGeehan, Procurator Fiscal, Policy and Engagement, for COPFS, also referred to what he saw as a precedent for legislation being used to send a message:

I absolutely agree that legislation can be used to send a message. An example of legislation that has been used for that purpose is the Emergency Workers (Scotland) Act 2005. It could be argued that the offences that that Act describes were already addressed by the common law—by breach of the peace and assault, for example—but it sent a message about the way in which the law would treat offences against emergency workers. It is an entirely appropriate function of legislation to send such a societal message.

Justice Committee, Official Report 3 October 2017, col. 23

The Law Society of Scotland did not take a view on repeal. During evidence, Alan McCreadie, head of research at the Law Society of Scotland, did refer to the position held by some about the message sent out by repeal:

There is a view that repealing the 2012 Act could send out the wrong message. I contend—Professor Leverick has just alluded to this—that the 2012 Act is not just hate crime legislation, albeit that its scope is subject to Lord Bracadale’s review. However, I guess that that would have to be weighed against the content of the Act and how it is working at present in terms of how the courts interpret it and how it can be enforced.

Justice Committee, Official Report 7 November 2017, col. 35

Queen's University Belfast academic Dr Joseph Webster, who is supportive of repeal, did not believe that this was sufficient grounds for opposing repeal:

The wider point is that, just because the faulty legislation—I think that the witnesses generally agree that it has significant problems—is repealed, that does not mean that we are affirming the validity of the types of behaviour that the Act tries to restrict and criminalise. The way in which repeal is perceived is all of our collective responsibility to deal with. To say that the legislation should not be repealed because it might send a problematic message to potential offenders is not a good enough reason not to repeal it.

Justice Committee, Official Report 14 November 2017, col. 45

Another argument put forward by several stakeholders was that it would be wise to wait until Lord Bracadale’s review of hate crime legislation, which included the 2012 Act in its scope, had concluded. Rev Galloway said:

It seems to us that, given that a wider review of hate crime is being undertaken, it would be wise to see society’s response to sectarianism in the context of that wider review.

Justice Committee, Official Report 7 November 2017, col. 3

Both of these two points were made by Chris Oswald, head of policy for the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC), who said:

I very much agree with Ian Galloway that it would be unwise to proceed with repeal of the 2012 Act until the wider review has been progressed and its findings have been discussed and debated. Although the discussions around the Act are predominantly about sectarianism, we must note that protections for disabled people and trans people would be lost if the Act were to be repealed, and there is at this point no prospect of their reintroduction. The threatening religious communications aspect of the Act would also be lost: again, there is no prospect at this point of its being reintroduced.

Justice Committee, Official Report 7 November 2017, col. 4

Assistant Chief Constable Bernard Higgins ("ACC Higgins") provided a view on the impact of the 2012 Act.

The Act has done two things: it has brought to the forefront for the wider Scottish community— not just the football community—what is and is not acceptable behaviour, and it has made it clearer when the police can take action to address behaviour at football matches and when they cannot.

Repealing the Act might be interpreted by some as a lifting of the restrictions on how they can behave in football stadia, or it might not.

The Act has allowed the police to address and challenge specific types of behaviour, and it has raised social consciousness. If the Act were repealed, the police would continue to try to address the behaviour using other legislation.

Justice Committee, Official Report 3 October 2017, col. 3

When asked what effect repeal would have on the policing of matches, ACC Higgins noted that it would not “pose a significant operational change”, telling the Committee that:

… we would continue to discharge our duties in the same manner ... We would seek guidance from the fiscal’s office about which charges we should apply, as opposed to those in the provisions of Section 1 of the 2012 Act … However, regarding boots on the ground and how football matches are policed, little—if anything—would change.

Justice Committee, Official Report 3 October 2017, col. 6

COPFS based its view on how effective it feels the 2012 Act is in prosecuting particular behaviours:

Our position is that use of the 2012 Act ensures that the behaviour can more securely be addressed and prosecution not be subject to the type of challenges that existed before the 2012 Act. When the Bill was first being debated by Parliament, the then Lord Advocate referred to cases in which there had been successful defence arguments that, for example, racist or homophobic abuse did not constitute a breach of the peace because of the peculiar circumstances of football and the potential that sections of a crowd might well be inured to that type of offending behaviour.

Justice Committee, Official Report 3 October 2017, col. 27

However, this view was not shared by SACRO, which stated:

While defining offensive behaviour likely to incite public disorder is helpful, such acts are also addressed in broader public order legislation and experience has shown that the application of the 2012 Act is not common or consistent in enforcement and prosecution action.

SACRO, written submission

Anthony McGeehan of COPFS also picked up on the Bill’s proposed transitional arrangements:

The Bill proposes a slightly unusual approach to repeal. There is almost a guillotine approach at the date of repeal for all live prosecutions. That is not the traditional approach, which is that new prosecutions would not be possible post-repeal but live prosecutions would not be affected. I understand that the policy behind the approach in the Bill is to prevent injustice, but only a minority of the charges and prosecutions relate to offensive behaviour under Section 1(2)(e) of the 2012 Act, which appears to be the subject of the most scrutiny. The remaining charges under Section 1(2)(a) to Section 1(2)(d) relate to behaviour such as hate crime. I ask whether a different type of injustice would be created if those prosecutions were brought to an end as a result of the approach that is adopted to repeal in the Bill.

Justice Committee, Official Report 3 October 2017, col. 24

There was also some disagreement over the impact the 2012 Act has had on offensive singing at football matches. Professor Fiona Leverick, Professor of Criminal Law and Criminal Justice at the University of Glasgow, stated:

If the question was whether the Act has been effective, I do not have any personal experience of that, but I point to the official evaluation of the Act that was undertaken by Niall Hamilton-Smith and some other colleagues, which was referred to in a previous evidence session. The evaluation concluded that there certainly had been a reduction in offensive chanting in football grounds since the Act came into force, but that it was impossible to tell whether that was because of the Act. I do not think that we will ever solve that conundrum, because so many other factors could have had an effect—changes in social attitude or policing strategies and so on. It will always be extremely difficult to attribute improvements to the Act.

Justice Committee, Official Report 7 November 2017, col. 47

Dr John Kelly took a slightly different view:

I would take issue a bit with the assertion that there have been fewer problematic songs at football games. As someone who has been to quite a number of Celtic games over the past few years, in a personal capacity and as an ethnographic observer, I would argue—I think that most Celtic fans would agree—that since the 2012 Act came in there have actually been more of what the Scottish Government might define as problematic songs. At Celtic Park and indeed away from it where Celtic has been playing, there have been more songs of an Irish nationalist and Irish republican nature than was the case before the introduction of the 2012 Act.

Justice Committee, Official Report 14 November 2017, col. 50

Impact on supporters

Another argument made for the repeal of the 2012 Act was regarding the impact on those charged with offences under the Act, and relations between fans and the police. In James Kelly MSP's view:

Football supporters do not like the fact that they are being specifically targeted with legislation that is pretty unique in Europe and that they are filmed going into football grounds. That has resulted in their relationship with the police deteriorating.

Justice Committee, Official Report 12 December 2017, col. 42

Police Scotland’s submissioni indicates that FoCUSii was established before the introduction of the 2012 Act and will remain. The methods of policing football matches are a policing operational matter which will not be affected by repeal of the 2012 Act.

Jeanette Findlay of Fans Against Criminalisation (FAC) laid out her experience of those charged under the Act, who had contacted FAC:

Over the past six years, around 200 people have contacted us ... I do not know whether you are aware of this, but there are usually three appearances at court: the pleading diet, the intermediate diet and the trial. The evidence, from our experience and the Stirling researchiii, is that the process is often extended in football cases and people have to appear in court four or five times for various reasons. Because of the nature of where alleged offences are supposed to have taken place, those appearances often involve people travelling quite long distances and having to take time off work and tell their employers that they have been charged.

Justice Committee, Official Report 3 October 2017, col. 49

Dr Joseph Webster reflected on the findings of his ethnographic researchiv on how the 2012 Act has been viewed by fans and the unintended consequences for how they now relate to the police and to one another:

They see themselves as the victims of the legislation because they see themselves as the ones being policed …

Having done extensive ethnographic work on exactly that question, I would dispute that there has been a dramatic decline in the singing of certain songs. What fans have done is change their behaviour by holding their hands in front of their mouths while singing certain songs in order to prevent CCTV from capturing them singing them. In addition, as we are all aware, they have replaced certain songs and chants with other words in order to try to skirt the law. My sense is therefore that one of the major problems with the 2012 Act is exactly the type of phenomenon that you are putting your finger on. The question therefore is what behavioural change the 2012 Act has brought about. Has the 2012 Act brought about behavioural change? Yes, it has, but it has not changed or discouraged the expression of the types of behaviours that the 2012 Act sought to do away with and it has not made people less offensive; it has made them engage in a different way in behaviour that the 2012 Act regards as offensive. The 2012 Act redirects those types of behaviours rather than prevents them from happening. That is a feature of the legislation because of the way that it was drafted....

The 2012 Act has made the policing of sectarianism more difficult, because fans have got wise to how to circumvent the law, and it has led to a deterioration in relationships between the fan bases and between them and the police.

Justice Committee, Official Report 14 November 2017, cols. 40, 49 and 59

Dr Stuart Waiton of the University of Abertay Dundee believed that the legislation emerged partly from views held of football fans by non-football fans:

There remains a snobbery about football fans except that, today, it takes a more politically correct form. If we are looking at people who are offended by football fans, we can look at prejudice and bigotry towards fans rather than just take it on good faith.

Justice Committee, Official Report 14 November 2017, col. 41

Danny Boyle of BEMIS provided some contextual commentary on the wider engagement with communities undertaken by football fans:

In respect of the 2012 Act, there is a tendency to talk about or assess football fans entirely negatively. I will say something beyond the statistics, which, as I have said, show that there is less hate crime in football than there is in the general populace. Football fans are running food drives and I have attended football games where there have been pro-refugee banners and antiracism banners. A couple of weeks ago, I saw, probably for the first time, some pro-LGBT banners at a game. There is a lot of progressive stuff happening in football clubs and among football supporters and in fan culture, and that should be appropriately acknowledged.

Justice Committee, Official Report 24 October 2017, col. 28

Paul Quigley of Fans Against Criminalisation related his own experiences since the inception of the 2012 Act:

In the past five years, we have not seen an improvement in terms of the behaviour of fans or the lessening of the singing of certain songs and so on. What we have seen is a breakdown in the relationship between fans and the police. That has been caused by this legislation…

The fan experience has been dramatically changed as a result of the 2012 Act. I understand what Mr Barrow said about how those experiences may differ depending on the club, including the size of the club, that a fan supports. In my experience, as a Celtic fan, from the second that fans get off a bus in any city across the country, they are filmed. Fans often feel intimidated from the second that they get off the bus to the second that they get back on it. They are subject to a type of surveillance that did not exist and that they did not have to experience before 2012. It is correct that there is now suspicion between fans and the police; the relationship has broken down, and I do not think that that is in anybody’s interest.

Justice Committee, Official Report 3 October 2017, cols 32 and 45

Responding to the argument that the 2012 Act criminalises young male football fans, Antony McGeehan of COPFS said:

I have read the critique that the 2012 Act focuses on young men. I suggest that the conclusion that the Act focuses on young football fans is incorrect. A conclusion that an Act focuses on young male persons in particular, or even on male persons in particular, might similarly be arrived at if we were to look at those persons who commit other types of criminal offences, such as sexual offences. If we did that, we would see that a significant proportion of people accused of sexual offences are male. In relation to the criminalisation of football fans, I would suggest that the question of whether an accused person is a football fan is irrelevant for the purposes of proving a case under the 2012 Act.

Justice Committee, Official Report 3 October 2017, col. 18

This view was echoed by ACC Higgins:

In the absence of the Act, those same young men would have been arrested but they would have been charged with a different offence, with the exceptions that Anthony McGeehan outlined in relation to the gaps. In the absence of the Act, someone who was arrested for singing an offensive song would almost certainly have been charged with a breach of the peace or a Section 38 offence. I do not accept the argument that the Act has criminalised young men. It has brought the issue to the forefront of people’s minds, but those arrests would still have taken place in the absence of the Act.

Justice Committee, Official Report 3 October 2017, col. 18

This perspective was shared by Chris Oswald, who said:

As to whether people are being brought into the criminal justice system because of the 2012 Act, I would say that that is happening because of their behaviour rather than because of the 2012 Act, which simply sets out behaviour that is felt to be socially damaging.

Justice Committee, Official Report 7 November 2017, col. 21

Andrew Tickell also noted that, for some fans, the specific targeting of the legislation is only part of their objection:

Their argument is that the 2012 Act is discriminatory because it targets only football fans. One way to make it not discriminatory is to make it apply to everyone, but the fans were still against the Act because of the offensiveness provision.

Justice Committee, Official Report 14 November 2017, col. 53

Freedom of speech

Dr Joseph Webster was of the view that “the Act is not justified on free speech grounds”, expanding by saying:

In essence, it says that it makes acts of hatred illegal but does not restrict “antipathy, dislike, ridicule, insult or abuse”. However, Section 6(5) does restrict those behaviours, which are set out in section 7(1)(b). The key problem is that there is insufficient ability to parse the behaviours. That has been evidenced in earlier oral submissions in which the committee has heard that police officers need to be trained on how to interpret different behaviours and on how to classify any given behaviour as hateful or perhaps abusive and where to draw the line.

Justice Committee, Official Report 14 November 2017, col. 36

For Fans Against Criminalisation, this was one of their main objections to the legislation:

We have two primary reasons for opposing it. The first is that it applies only to football fans, as I have said, and we believe that laws should apply universally. The second is that we think that creating an offence that criminalises something as subjective as offensiveness represents a broader danger to freedom of speech and freedom of expression. On that basis, we would oppose legislation that, for example, criminalised certain offensive behaviours outwith hate crime in other arenas.

Justice Committee, Official Report 3 October 2017, col. 37

The Committee also heard opposing views on whether the legislation infringed on free speech. Dr Stuart Waiton believes that it does, observing that, in his view:

We hide behind the public order issue, but essentially it is about the criminalisation of words and thoughts, and the arresting and imprisoning of people because we do not like their words.

Justice Committee, Official Report 14 November 2017, col. 38

However, other witnesses believed that the legislation did not inappropriately suppress freedom of speech. Chris Oswald of the EHRC noted:

Although the EHRC recognises that freedom of speech and freedom of expression are enormously important and are protected by article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights [ECHR], they need to be balanced against the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which says that states need to have in place laws that counter “incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence”. It is the Commission’s position that the international convention overrides the ECHR, in this case.

Justice Committee, Official Report 7 November 2017, col. 4

This position was shared by Ephraim Borowski, Director of the Scottish Council of Jewish Communities, who said:

I am also therefore predisposed against repealing any anti-hate crime legislation, for exactly the reason that Ian Galloway gave: doing so could inadvertently send the wrong message, that somehow some kind of hate crime, speech or action is now acceptable in society.

Justice Committee, Official Report 7 November 2017, col. 5

Responding to those who objected to the 2012 Act on free speech grounds, the Minister stated:

Freedom of speech is, of course, a fundamental right, but it is not an absolute right. There is also the freedom not to be subjected to hateful and prejudicial behaviour.

Justice Committee, Official Report 5 December 2017, col. 13

The Policy Memorandum for the Bill refers to freedom of speech and other human rights concerns:

Arguments have been made that the 2012 Act is incompatible with the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). The Scotland Act 1998 requires legislation of the Scottish Parliament to be compatible with Convention rights. The Section 1 offence has been viewed as restricting Article 10 rights to freedom of expression and creating legal uncertainty through the vagueness and subjectivity of key concepts it employs, such as "behaviour that a reasonable person would be likely to consider offensive".

Policy Memorandum, paragraph 47

This view was shared in a supplementary submission from the Scottish Human Rights Commission (SHRC) regarding the rights implications of the 2012 Act. While remaining “supportive of the overall policy objective of the Act”, the SHRC concluded that “there is a strong likelihood that key provisions of the Act fall short of the principle of legal certainty and the requirement of lawfulness”. The SHRC also stated:

It is important that the Act strikes the right balance between the protection of public order and equality in one hand and freedom of expression on the other. The provisions of the Act must also be considered in terms of whether they are necessary and proportionate to the aim of prevention of offensive behaviour in relation to football matches.

SHRC, written submission

However, the Scottish Government did not agree with the SHRC’s conclusions with the Minister stating:

I remain happy that the Act is compatible with human rights. The Commission’s submission appears to be a statement of its 2011 position, which does not take account of developments such as the Donnelly and Walsh case of 2015i, which did not identify any human rights issues.

Justice Committee, Official Report 5 December 2017, col. 9

The Minister added:

When the Bill was introduced, like any Bill, the Presiding Officer had to certify it as being competent—under the Scotland Act 1998, we have a duty to comply with the Human Rights Act 1998. The Bill was passed by Parliament and, following its passage, the law officers did not seek to raise any action to challenge its compatibility.

Justice Committee, Official Report 5 December 2017, col. 21

Hate crime and offensive behaviour

Another recurring theme in evidence was the extent of the role played by the 2012 Act in tackling hate crime. As has been covered elsewhere in the report, some witnesses referred to Lord Bracadale’s review of hate crime legislation, suggesting it would be worthwhile to wait until this had concluded before repealing the 2012 Act.

The Scottish Council of Jewish Communities stated:

We do not believe it appropriate to make changes to individual pieces of legislation during Lord Bracadale’s review of hate crime legislation, but strongly recommend awaiting his report.

Scottish Council of Jewish Communities, written submission

Victim Support Scotland, who support retaining the 2012 Act, shared this view, stating:

The on-going review of hate crime legislation in Scotland might allow the 2012 Act to be considered in the context of all hate crime legislation, which will help ensure that the overall legal coverage is appropriate and captured without compromising civil liberties.

Victim Support Scotland, written submission

However, as pointed out by Danny Boyle of BEMIS, the proportion of offences under the 2012 Act which were related to hate crime could be considered to be low:

The predominant hate crime charge under the Act has been for religious aggravation, and the predominant characteristic within the religious aggravation is anti-Catholicism, which accounts for over 75 per cent of charges in every reporting year. That being said, in relation to the volume of attendees at Scottish football matches, hate crime charges under the Act actually account for less than 50 per cent of all charges in every year of reporting. Indeed, in the year in which the Act was used most often—2016-17—in which there were 377 charges, only 18 per cent were for hate crimes.

Justice Committee, Official Report 24 October 2017, col. 5

Mr Boyle elaborated on this point later in evidence:

The dissemination of statistics in relation to the 2012 Act further clouds what is ambiguous and offers no illumination on the extent of hate crime issues in Scotland. Over the five-year lifetime of the Act, specifically in relation to hate crime—not a reclassified breach of the peace—we have had 64 race charges, six anti-Semitic charges, four Islamophobic charges, eight homophobic charges and one aggravation where anti-disability was the charge. All those hate crimes would be covered by pre-existing legislation. There is absolutely nothing new in the Act that did not exist before 2011 to deal with hate crime … we think that the most sensible thing is to create a universal approach to tackling hate crime that is preventative and rooted in education but which also has a strong legal remedy when necessary. The most simple way in which we envisage that being taken forward is to have a piece of hate crime legislation that reflects the characteristics in the Equality Act 2010 and which can be evolved and updated as society changes. Some of the contested issues that remain live in the context of the Football Act are about things that do not constitute hate crime and are separate—they are about what would be offensive to a reasonable person. They have to be dealt with outside the legislation.

Justice Committee, Official Report 24 October 2017, cols. 11 and 12

Professor Fiona Leverick also noted this subtlety:

Not everything in the 2012 Act is a hate crime provision; a lot of it relates to hate crime, but not all of it. Some parts are about straightforward public order offences that have no connection to hate crime whatever. At least part of the Section 6 criminal offence is not a hate crime related provision. I said that we should hang on and wait to see what Lord Bracadale says, but that will take us only so far because there are parts of the 2012 Act that do not relate to hate crime.

Justice Committee, Official Report 14 November 2017, col. 35

James Kelly MSP provided further context for the statistics:

The latest statistics on religious hate crime, which have been provided to the committee, show that there were 719 charges relating to religious hate crime in 2016-17. That is the highest that the figure has been in the past four years, which shows that there is a serious problem. However, only 46 of those charges were under the 2012 Act, so less than 7 per cent of the charges related to football. That demonstrates that we have a serious problem with religious hate crime in Scotland, which is something that should concern all of us, but the idea that it all carries on around football has been blown out of the water by the fact that only 7 per cent of those charges relate to football.

Justice Committee, Official Report 12 December 2017, Col. 38

Should the 2012 Act be repealed, COPFS confirmed that:

The Lord Advocate has published guidelines in relation to the operation of the 2012 Act by the police. We would intend to publish similar guidelines in relation to the application of breach of the peace and Section 38 of the Criminal Justice and Licensing (Scotland) Act 2010 should the Parliament decide to repeal the 2012 Act.

Justice Committee, Official Report 3 October 2017, col. 6

The Committee notes the views held by a range of stakeholders on both sides of the debate, and appreciates that the 2012 Act evokes strong feelings among both its supporters and opponents. The Committee unanimously condemns sectarianism, hate crime and offensive behaviour and considers it unacceptable. The Committee notes the evidence from some fans' groups that this has led to strained relations between their members and the police.

The Committee also recognises that the number of football fans engaging in criminal behaviour is minimal, and welcomes the context provided by the SFA, Police Scotland and fans’ groups to demonstrate this is the case.

The Committee acknowledges the statement made by the Minister regarding the inherent tension between different freedoms. However, the Committee notes the human rights concerns raised by the Scottish Human Rights Commission and others, and urges the Scottish Government to explore how it can continue to safeguard human rights and minimise the risk of misunderstandings around the legislation and individuals’ rights.

Regardless of whether or not the 2012 Act is repealed, the Committee believes that it would be appropriate for the Scottish Government to clarify what constitutes hate crime once the position on repeal of the 2012 Act is known and Lord Bracadale's review of hate crime legislation is concluded.

Section 1 offence

Use of Section 1 offence by COPFS/the police

As has been covered earlier in this report, Section 1 of the 2012 Act creates an offence of “offensive behaviour at regulated football matches”. The Section 1 offence includes a number of separate elements. One is that the offending behaviour is "in relation to a regulated football match". Such behaviour can take place in the ground where a match is being held and on the day it is being held. Also covered is behaviour while the person is entering or leaving the ground or on a journey to or from the match. The same is true in relation to non-domestic premises where a match is being televised - so a person can commit the offence in, for example, a pub where the match is being televised.

The second element of the offence is that it involves behaviour that is or would be "likely to incite public disorder". Thirdly, the behaviour must be at least one of the following:

behaviour "expressing hatred of, or stirring up hatred against", a group of persons based on their religious affiliation or a group defined by reference to their colour, race, nationality, ethnic or religious origins, sexual orientation, transgender identity or disability - or against any individual member of such a group;

behaviour motivated by hatred of such a group;

behaviour that is threatening; or