Health, Social Care and Sport Committee

ADHD and autism pathways and support

Membership changes

The following changes to Committee membership occurred during the course of this inquiry:

On 21 May 2025, Patrick Harvie MSP replaced Gillian Mackay MSP as a member of the Committee.

On 17 December 2025, Gillian Mackay MSP replaced Patrick Harvie MSP as a member of the Committee.

Summary of recommendations

Accessing pathways to support

The Committee notes with concern the evidence it has heard about the lack of pathways to support for adults, and for children without co-occuring mental health conditions in some health board areas, and the confusion inconsistencies in available pathways across Scotland can cause for individuals and their families.

The Committee welcomes the Scottish Government's commitment to accept the recommendations set out in NAIT's Adult Neurodevelopmental Pathways report, including the development and implementation of guidance for adult pathways in all HSCPs across Scotland, and to review the implementation of the National Neurodevelopmental Specification for Children and Young People through its new task force.

At the same time, the Committee calls on the Scottish Government to take urgent action to develop and implement a national plan to give adults and children with autism and ADHD across all health boards in Scotland access to clear and consistent pathways to support. This should include continuing to work with NAIT and health boards to implement the recommendations from the pathfinder pilots and delivering an updated Specification for children's pathways.

Treatment thresholds and gatekeeping

The Committee recognises that the scale of demand for neurodevelopmental assessments has made it necessary to put certain thresholds in place before a referral is made and that this has resulted in gatekeeping access to assessments in some areas.

However, the Committee has been concerned to hear evidence that many people feel those responsible for referrals and gatekeeping do not have an accurate, up to date understanding of neurodevelopmental conditions and how they present, particularly in women, girls and ethnic minority people, meaning that thresholds may not be applied fairly or appropriately in some cases.

The Committee is further concerned that an over-reliance on threshold setting and gatekeeping risks resulting in many individuals being unable to access the support they need at the appropriate time, leading to a situation where these individuals will then present themselves at a later stage having reached a state of crisis, which can be considerably more difficult and costly to treat. The Committee concludes that, although perhaps understandable when trying to deal with consistently high demand, such an approach to managing access to pathways risks being counterproductive in the longer term.

The Committee therefore calls on the Scottish Government, in responding to this report, to set out how it intends to address this challenge and to ensure Health Boards shift their focus to a progressive approach which ensures the provision of treatment and support for autistic people and/or people with ADHD at the earliest opportunity, in line with the principles of its Population Health Framework.

The Committee further recommends that the Scottish Government takes action to ensure improved consistency and timeliness across Scotland of access to treatment and support, including an assessment or diagnosis where appropriate.

To further improve quality and consistency, the Committee calls on the Scottish Government to develop a plan to deliver mandatory training to all those who are involved in making referrals to neurodevelopmental pathways. This training should:

be developed in collaboration with people with neurodevelopmental conditions

draw from existing resources already developed by NES, NAIT and in health board areas where appropriate

be monitored and reported on to determine rates of uptake.

More broadly, the Committee recommends a programme of mandatory training on neurodevelopmental conditions for all health and social care staff in patient-facing roles.

Open referral

The Committee notes concerns from many healthcare practitioners that broader application of an open referrals model for accessing ADHD and autism pathways would create a risk of "opening the floodgates" to even greater demand and a rise in inappropriate referrals that would be liable to overwhelm services.

At the same time, the Committee notes a strong desire from many individuals to have the option of open referral available to them. It further notes evidence from certain areas where an open referral model is already in place which suggests concerns about services being overwhelmed are not borne out by experience on the ground. Instead, there is strong evidence to suggest an open referral model can help pathways and services to operate more efficiently and responsively.

The Committee therefore calls on the Scottish Government, in responding to this report, to set out what further action it is taking or plans to take to gather further data about the practical impact and any specific benefits for pathways and services of allowing open referrals, to learn appropriate lessons from experience of open referrals on the ground and to explore how open referrals can be made more widely available across Scotland in a way that allays workforce fears that this will result in services being overwhelmed.

Beyond this, the Committee would encourage the Scottish Government to explore how, in future, processes for open referral can be better integrated into national standards for ADHD and autism pathways and support.

Waiting times

The Committee has been extremely concerned to hear evidence during this inquiry of many individuals having to wait many years on a waiting list for assessment for ADHD, autism and other neurodevelopmental conditions, as well as evidence from many areas where waiting lists have now been closed. It is firmly of the view that, as well as being detrimental to the individuals affected, such a situation is damaging to wider society to which, for as long as they fail to receive the support and treatment they need, these individuals may be prevented from making an active and positive contribution.

The Committee acknowledges evidence of an unprecedented rise in demand for neurodevelopmental assessments in recent years. It has been persuaded by evidence that this rise is not attributable to a tendency towards over-diagnosis but rather to an historic under-diagnosis of ADHD and autism and an improved understanding of these conditions more recently. The Committee is also sympathetic to the suggestion that promoting a narrative around over-diagnosis is unhelpful and risks further stigmatising those with autism and/or ADHD, with the result that their condition is not believed or understood and they are denied access to the pathways and support they need.

Given the current length of waiting times, the Committee believes it is particularly crucial that the quality of communication with those on waiting lists is consistently high, that available information is accurate, supportive and up-to-date, uses neuro-affirming language and is delivered in a way that is responsive to the specific needs of those with autism and/or ADHD.

For the same reason, the Committee calls on the Scottish Government to give much greater attention, including the commitment of appropriate resources, to the development of "waiting well" initiatives that provide suitably targeted access to good information and local support as a consistent and integral part of the waiting process for those on neurodevelopmental pathways.

The Committee welcomes the Scottish Government's establishment of a task force and its commitment of additional funding to support implementation of the National Neurodevelopmental Specification. As part of this work, the Committee calls on the Scottish Government to produce a roadmap setting out clear timelines for improvement of ADHD and autism pathways and support. This should address improvements to information and communication (including the potential establishment of a 'one stop shop'), improved access to local support while waiting, the roll-out of targeted "waiting well" initiatives and the commitment of funding to develop the multi-disciplinary workforce needed to reduce waiting times in the longer term.

Assessment process

The Committee calls on the Scottish Government, in close collaboration with health boards, to undertake a comprehensive review of the assessment process in all areas with a view to developing a National Standard for assessments that guarantees consistency of access, responsiveness and support throughout Scotland. In particular, this review and the resulting National Standard should address:

ensuring diagnostic criteria used in assessments are appropriate and up-to-date;

a presumption against the use of single condition assessments, given the high rate of co-occurrence of ADHD and autism (as well as other neurodevelopmental conditions and other mental and physical health problems) and the active promotion instead of the use of holistic assessments;

the development of guidelines to establish clear qualification requirements for those carrying out neurodevelopmental assessments;

Promoting the direct involvement of individuals with lived experience of neurodevelopmental conditions in helping and supporting others to navigate the assessment process;

clear guidance for the use of alternative approaches to assessment such as "whole school" approaches, "stepped care" and "consensus diagnosis" - to include details of the circumstances in which such alternative approaches may be more appropriate than traditional approaches to assessment;

promotion of a multi-disciplinary approach to assessment, including requirements for members of multi-disciplinary teams to undergo continuous professional development and training on providing neurodevelopmental assessments, to include regular updates in neuro-affirming practice.

To ensure the review and resulting National Standard are as responsive as possible to the needs of those seeking an assessment, the Committee calls on the Scottish Government to ensure individuals with lived experience of neurodevelopmental conditions and the community groups that support them, are actively involved in the review process.

The Committee also believes there should be a requirement on health boards to work with the National Autism Implementation Team to ensure updated service specifications for provision of services are successfully implemented, both for children and young people and for adults.

Diagnosis

The Committee acknowledges there are a number of valid reasons for seeking a diagnosis for autism and/or ADHD, including:

Giving individuals a sense of validation and understanding about themselves as people, including understanding current and past life experiences

Determining what forms of support, adjustments or treatment would be most helpful and giving individuals and/or parents and carers the ability to advocate for these.

At the same time, the Committee also acknowledges fundamental differences between these conditions which mean the reasons for seeking a diagnosis will vary between autism and ADHD. In particular, the Committee notes that, as a medically treatable condition, there are especially important reasons for receiving a positive diagnosis for ADHD since this will ensure the individuals affected are able to access the correct medication to treat their condition.

While welcoming the Scottish Government's recognition of the importance of diagnosis while committing itself to ensuring receiving a diagnosis is not a prerequisite for accessing support, the Committee remains concerned that, in reality, the lack of a formal diagnosis has become a barrier to accessing support for too many individuals.

The Committee therefore calls on the Scottish Government, in responding to this report, to set out what action it is taking or plans to take to ensure the lack of a formal diagnosis is not used as an artificial barrier to accessing support and to encourage practitioners to fully explore what support can be made available while individuals are waiting to receive a formal diagnosis.

The Committee highlights the particularly urgent need for formal diagnosis for those individuals who require it to be able to access the correct medication to treat their condition. It therefore calls on the Scottish Government to set out what strategies it is pursuing to reduce waiting times for assessment and diagnosis of these individuals.

Private diagnosis and 'shared care'

The Committee has been concerned to hear evidence of many individuals being forced to seek a private diagnosis, often at significant financial cost, due to long waiting times for accessing neurodevelopmental assessment and diagnosis via the NHS. The Committee is particularly concerned that this risks creating a two-tier system where timely access to diagnosis is based on an individual's ability to pay.

The Committee has been similarly concerned to hear evidence that the quality of assessments and diagnoses acquired privately can be variable. The Committee therefore urges the Scottish Government, in responding to this report, to set out what action it is taking or plans to take to promote a level playing field in standards of assessment and diagnosis across the public and private sectors.

The Committee further notes the negative experiences of many individuals, having acquired a private diagnosis, of getting their GP to recognise that diagnosis or to agree to provide "shared care". The Committee recognises that greater reliability of standards for assessment and diagnosis, whether provided privately or through the NHS, are needed to give GPs the confidence to accept "shared care" agreements.

The Commitee also recognises that, until NHS capacity is significantly expanded, individuals seeking private assessment and diagnosis is likely to be an ongoing fact of life. In these circumstances, it calls on the Scottish Government to work with Healthcare Improvement Scotland, health boards and GPs to address problems with shared care agreements and to develop a more consistent approach to their use.

Transitions

The Committee recognises the particular importance of well managed transitions for people with neurodevelopmental conditions but regrets that too many report experiences of poorly managed transitions and a lack of appropriate support during transitional periods in their lives.

The Committee highlights evidence of particular challenges for people with neurodevelopmental conditions in making the transition from child to adult services at a particularly vulnerable stage of their lives - and the crucial importance of maintaining consistent relationships during this period to be able to successfully navigate this transition. The Committee has also heard similarly concerning evidence of poor planning and support for children with neurodevelopmental conditions in making the transition from primary to secondary school and from education to post-education settings.

In light of this evidence, the Committee calls on the Scottish Government, in responding to this report, to set out what action it is taking to ensure proper implementation of its Principles of Transition policy, GIRFEC policy and guidance and the relevant provisions of the National Neurodevelopmental Specification, so that people with neurodevelopmental conditions do not experience any further negative effects from poorly planned and supported transitions.

In so doing, the Committee further calls on the Scottish Government to address an apparent gap in the National Neurodevelopmental Specification for Children and Young People by ensuring there is absolute continuity of care throughout these important transitions and into adulthood.

The Committee pays particular tribute to the work of third sector organisations in supporting people with neurodevelopmental conditions during periods of transition and calls on the Scottish Government, in responding to this report, to set out what it is doing to support third sector organisations operating in this space.

Role of third sector

The Committee pays tribute to the crucial work of third sector organisations in providing support to those people with ADHD and autism who have not received or are yet to receive a formal assessment or diagnosis from statutory services. It notes that, without access to such support, many individuals would be left isolated and unsupported.

The Committee further commends the work of the third sector in involving people with lived experience of neurodevelopmental conditions in delivering the support it provides - and notes how much their involvement is welcomed by individuals using these services.

Given how crucial third sector support can be in this area, the Committee welcomes the Scottish Government's ongoing commitment to supporting third sector organisations through vehicles such as the Autistic Adult Support Fund. It calls on the Scottish Government, in responding to this report, to set out what further actions it plans to take to continue to support the third sector and to place funding for third sector organisations on a more sustainable long-term footing.

Whole society approach

The Committee highlights the broad range of evidence it has heard throughout this inquiry in support of a whole society approach as the most effective means, longer term, of supporting people with neurodevelopmental conditions, improving wider public awareness and combatting stigma.

In this context, the Committee welcomes the Scottish Government's commitment that its new task force will take a whole-systems approach, working across the health and education sectors to implement the National Neurodevelopmental Specification.

Beyond this, the Committee calls on the Scottish Government, in responding to this report, to set out what actions it will take to further promote a whole-systems or whole society approach, including:

learning the requisite lessons and developing associated guidance from examples of best practice in whole systems approaches, such as that seen in NHS Ayrshire and Arran;

what, if any, steps it intends to take towards developing a national workforce plan as an important component of a whole-systems approach;

how distribution of funding will be adapted in future to facilitate a more integrated, cross-sectoral approach to support;

promoting educational settings that are more inclusive of people with neurodevelopmental conditions;

addressing the particular needs of families with multiple family members who are living with neurodevelopmental conditions; and

promoting closer collaboration between the various different public services people with neurodevelopmental conditions come into contact with.

The Committee has heard evidence from many contributors to the inquiry who have expressed regret that the Scottish Government has paused plans for a Learning Disabilities, Autism and Neurodivergence Bill, which it was felt would contribute positively towards promoting a whole systems or whole society approach to supporting people with neurodevelopmental conditions. The Committee notes the Minister's commitment, in the absence of further progress on a Bill, to publish draft provisions. It calls on the Scottish Government, in responding to this report, to set out a timetable for publication and to provide further details of what these might cover.

Data

The Committee highlights the importance of consistent, reliable, high quality data on neurodevelopmental referrals and waiting times across Scotland to be able to plan services effectively and to make ongoing improvements.

In this context, the Committee has been concerned to hear evidence of significant gaps and a lack of standardisation in data gathering, including across NHS Boards.

The Committee therefore calls on the Scottish Government to set out what steps it plans to take to enable routine quarterly reporting of data on referrals and waiting times for autism and ADHD, underpinned by national guidance.

While welcoming that this will be an area of longer term focus for the new Scottish Government task force, the Committee further calls on the Scottish Government to address how it intends to overcome potential barriers to more consistent data collection and reporting, such as use of different software systems and location of data across multiple different systems and services.

The Committee considers that future work to improve data gathering and reporting should culminate in the establishment of a comprehensive dashboard, with the aim of improving transparency, enhancing effectiveness, and reinforcing patient trust.

Introduction

In April 2025, the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee agreed to undertake an inquiry into Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and autism pathways and support.

The agreed scope of the inquiry was to consider key issues including:

Why waiting times for assessment, diagnosis and support for ADHD and autism are reportedly long, including the drivers of increasing demand;

How these conditions are currently diagnosed and managed;

The impact of high demand and delays on individuals and healthcare staff;

Exploring solutions to improve the capacity of services, referral pathways and support.

It was agreed that the inquiry would consider the following in relation to neurodevelopmental pathways for ADHD and autism:

referral pathways

assessment, criteria and treatment thresholds

waiting times

"waiting well" and support pre-diagnosis

transitions between services

funding

workforce

the impact on individuals of receiving a diagnosis or waiting for a diagnosis.

In March 2025, the Committee wrote to each of the fourteen NHS territorial boards requesting information on neurodevelopmental pathways and waiting times. All boards responded and SPICe used the data received to produce a briefing on Neurodevelopmental Pathways and Waiting Times in Scotland.

This briefing reported that, as of March 2025, over 42,000 children were waiting for a neurodevelopmental assessment in Scotland (see Figure 1) and that, in some areas, this figure had increased by over 500% since 2020. Over 23,000 adults were found to be waiting for a neurodevelopmental assessment in Scotland (see Figure 2), an increase of over 2200% since 2020 in some areas.

.png)

.png)

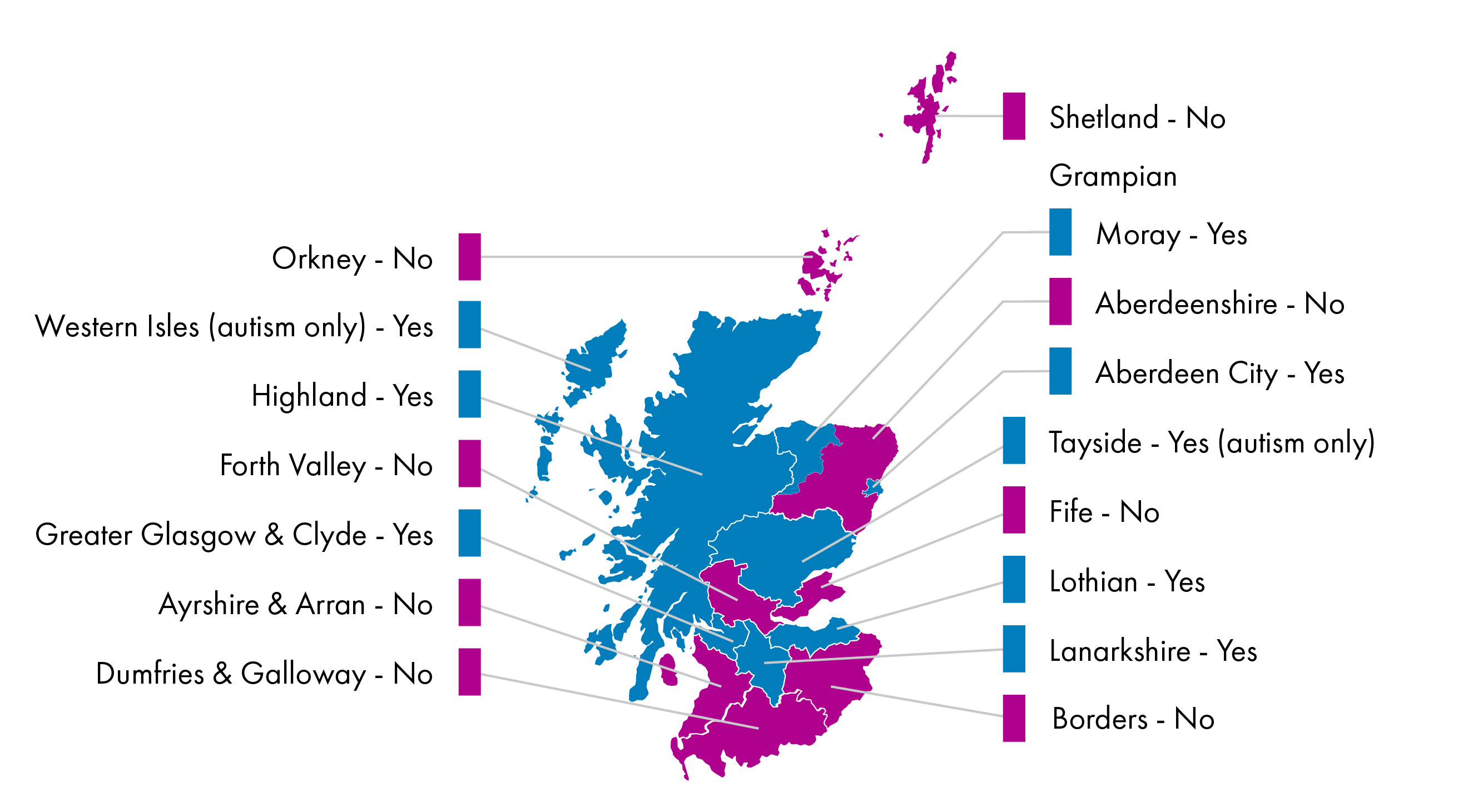

The briefing also reported that pathways for neurodevelopmental assessments vary considerably across Scotland and that, in some areas, no pathway is available through the NHS board for an adult who does not meet the criteria for referral for secondary mental health services (See Figure 3).

At its meeting on 18 June 2025, the Citizen Participation and Public Petitions Committee agreed to refer the following petition to the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee for further consideration as part of the inquiry: Improve access to ADHD diagnosis and treatment across Scotland - Petitions.

In preparation for the inquiry, the Committee wrote to the Minister for Social Care and Mental Wellbeing on 23 June 2025 to request a general update on policy in this area. A response was received from the Minister on 26 August 2025.

As part of the inquiry, the Committee issued a general call for views targeted at organisations on Citizen Space on 23 June 2025.

The call for views asked:

Please tell us your views on the aims of the inquiry, in relation to the people you support, and describe any opportunities for improvement you have identified.

A separate call for views targeted at individuals, families and support workers was issued on the Your Priorities engagement platform on 23 June 2025.

This call for views asked:

Please tell us about your experiences of seeking an Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and/or Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) diagnosis in Scotland.

Why did you seek a diagnosis?

Is there anything that would have made your experience better?

The call for views on Citizen Space received 86 published responses. SPICe produced a summary analysis of these responses. Your Priorities received 1158 unique submissions and SPICe also produced a summary analysis of these submissions. The Committee is grateful to all those who took the time to respond to the call for views, especially those who shared their lived experiences.

At its meeting on 23 September 2025, prior to commencing taking oral evidence as part of the inquiry, the Committee received a private background briefing from the National Autism Implementation Team (NAIT). NAIT provided a written submission in advance of the private briefing. NAIT also provided the Committee with Neuro-affirming Language Guidance on terminology.

Committee Members held two informal engagement sessions on 25 September 2025 to hear directly from people with ADHD and/or autism. These sessions were supported by the National Autistic Society Scotland and a peer support group for people with ADHD. Anonymised summary notes of the sessions have been published on the Committee webpages. The Committee would like to thank those who volunteered to share their experiences during these sessions.

The Committee also took oral evidence as part of the inquiry over the course of five meetings, from witnesses including:

third sector organisations that support people with ADHD and autistic people

professionals involved in providing support to people with ADHD and autism

NHS Boards

the Minister for Mental Wellbeing and Social Care.

At its meeting on 7 October, the Committee agreed to change the title of the inquiry from "ADHD and ASD pathways and support" to "ADHD and autism pathways and support".

Links to the Minutes and the Official Report of Committee meetings can be found in Annexe A and B.

Background

An increasing number of people in Scotland are seeking neurodevelopmental assessments for conditions such as autism and ADHD. Many specialists in this field argue that this surge in demand is driven mostly by increased awareness of neurodivergence and how it presents, rather than an increase in the number of neurodivergent people. As a result of increased demand, some people have faced long waits to be seen and services have been withdrawn in some areas.

Concerning trends in assessment for autism, Mark McDonald from Scottish Autism told the Committee:

Autism was first diagnosed less than 100 years ago, but that is not to say that autistic people did not exist before then ... We just recognise it now—we understand it, and our understanding has grown. Over the time that our understanding has grown, the thresholds for diagnosis have changed. That has meant that people who historically would not have received a diagnosis are now able to achieve one.

More background information to the inquiry can be found in the SPICe briefing Neurodevelopmental Pathways and Waiting Times in Scotland and in the following SPICe blogs:

The Minister for Social Care and Mental Wellbeing made a statement to Parliament on 26 June 2025 entitled Ensuring the Right Support for Young People’s Neurodivergence, Mental Health and Wellbeing. The statement included an announcement of plans for a cross-sector task force to address the provision of neurodevelopmental services for children and young people in Scotland, supported by £500,000 of additional funding to deliver improvements in these services.

This statement accompanied the publication of a review of the implementation of the National Neurodevelopmental Specification. Among the review’s findings were that:

there was a mixture of views as to whether the Specification met the needs of children, young people and families,

while some praised the increased focus on a neurodevelopmental and multidisciplinary approach, the majority of people surveyed felt that the Specification had had limited impact,

there were major challenges to implementation, including increasing demand, limited funding and poor communication between partners in the Specification’s delivery,

the intended move to a needs-based model had not reduced the demand for diagnostic services, and

there was a lack of clarity over who was responsible for different aspects of implementation, including diagnosis and assessment.

In June 2025, four third sector organisations published a co-produced report entitled Experiences of Autism Assessment and Diagnosis in Scotland.

In October 2025, the Royal College of Psychiatrists in Scotland published a report entitled Multi system solutions for meeting the needs of Autistic and ADHD people in Scotland.

Referral pathways

Accessing pathways to support

As part of the current inquiry, the Committee wrote to each of the fourteen NHS territorial boards requesting information on neurodevelopmental pathways for children and adults. The information received showed variation in the pathways available across Scotland. In several areas, there was no adult neurodevelopmental pathway available. Meanwhile, in some areas, pathways for children were only available to those with a co-occurring mental health condition or who met the criteria for referral to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS). For a full breakdown of neurodevelopmental pathways in Scotland, see the SPICe briefing Neurodevelopmental Pathways and Waiting Times in Scotland.

During the inquiry, the Committee heard about the importance of early intervention for people with neurodevelopmental conditions. During oral evidence, Anya Kennedy from the Royal College of Occupational Therapists outlined the benefits of early intervention:

By providing support at an early age, when it is needed during their key developmental years, we help children to understand themselves, and how the world around them works, and to manage the various journeys within that ... By helping a child earlier we also support their parents, grandparents and siblings and the local community ... If we are able to support them in the early part of the process, during their childhood, the hope is that they might be able to rely less on services later in their adolescence— for example, within CAMHS or the adult community mental health teams.1

The importance of early intervention was further highlighted by other witnesses. Dani Cosgrove from Stronger Together for Autism and Neurodivergence (STAND) argued :

When support comes at the right time, the benefits extend far beyond the child. It creates stronger families, calmer classrooms and reduced pressure on services, rather than left to escalate ... For us, the right time for support and assessment is as soon as the first concern is raised, whether that is by the child, a family member, a teacher or another professional ... The clearest wider benefit of acting at the right time is simply the prevention of unnecessary harm.2

Dani Cosgrove went on to highlight the confusion that variation in available pathways across Scotland can create for parents and carers:

The variations cause inconsistency, confusion and inequity ... The support in each area is different and that information is unclear. Transparency for children and parents and carers is also lacking ... it is difficult even for us to give correct advice. We could give a family in East Lothian advice and it would be different from the advice that a family in the Highlands would need.2

Variations in available pathways and services between NHS health boards was also identified as a key issue in written submissions to the Committee's call for views.

In its written submission, the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) Scotland identified:

Inconsistencies in neurodevelopmental pathways and staff makeup within services ... [Noting that] these variations contribute to uneven service delivery, exacerbate workforce pressures, and further extend already lengthy waiting lists.4

NHS Grampian Speech and Language Therapy Service noted:

Within NHS Grampian we do not have defined and equitable neurodevelopmental pathways for any age group/client group but as practitioners [we] recognise the need for this.5

The National Autistic Society Scotland called for:

A nationally consistent approach so that families and autistic adults know what to expect and […] an end to the post-code lottery of access.6

Many individuals with lived experience who responded to the Committee's call for views highlighted the personal impact of a lack of available pathways for adults in some areas. For example, one respondent stated:

I am very sure I have ADHD but have no diagnosis. It has a massive impact on my life and I have recently experience yet another burnout and have been unemployed for almost a year as a result (having previously worked in a full time well paid role). I finally approached the GP to find out options for an assessment and was told that unless I am in crisis there is no waiting list that I can join as they have been closed ... I’ve honestly been shocked that there is no support available to even talk about an assessment through the NHS and have no idea what I can do to access support. I want to work, I want to thrive as an individual, a parent, a citizen, an employee but I honestly feel like I get so paralysed and overwhelmed and burnout due to suspected ADHD that I’m not able to ... I feel totally isolated and disillusioned.7

Several witnesses mentioned the work of the National Autism Implementation Team (NAIT), who have carried out pilot projects in four health board areas to develop and implement adult neurodevelopmental pathways. These witnesses argued that the recommendations from these projects should be implemented across Scotland.

For example, Mark McDonald from Scottish Autism told the Committee:

We must take the learning that we got from the neurodevelopmental pathway pilots that were done by NAIT and implement it across Scotland. Best practice is a bad traveller, but there is no reason why we cannot take the learning from those pilots and apply it elsewhere.2

In its Adult Neurodevelopmental Pathways report, the National Autism Implementation Team (NAIT) made ten recommendations resulting from their assessment of the pilot projects, including:

"An adult neurodevelopmental pathway strategy and planning group to be hosted in all HSCPs"

"Development of Adult Neurodevelopmental Pathway standards and guidelines for assessment, diagnosis and support"

"Build a shared expectation that support should be available at any stage for people who identify as neurodivergent"

In his letter to the Committee providing an update on Scottish Government policy in this area, the Minister for Social Care and Mental Wellbeing stated:

Following the publication of the Adult Neurodevelopmental Pathways report, the Scottish Government accepted all ten of the report’s recommendations, and we are taking work forward to implement these.9

The letter added:

Earlier this year, my officials wrote to all health boards seeking clarification on the neurodevelopmental assessment and support they currently have in place for adults. This information is currently being collated and considered, along with next steps.9

In relation to support for children with neurodevelopmental conditions, the Scottish Government published the National Neurodevelopmental Specification for Children and Young People in 2021. As outlined above, a recent review of the implementation of the National Neurodevelopmental Specification set out a number of key findings.

In oral evidence, the Minister for Mental Wellbeing and Social Care told the Committee:

The Scottish Government is committed to improving access to timely, needs-based support for neurodivergent people ... The National Autism Implementation Team published the pathways report a couple of years ago. The Government accepted the recommendations from that and has been working with health boards to support implementation of those recommendations, but I recognise that there is currently variation. Recognising the day-to-day operational role that health boards have, we are committed to continuing to work constructively with boards to achieve the level of national consistency that people across Scotland expect ... For children and young people, our work is guided by the national neurodevelopmental specification, which promotes the provision of early, needs-led support through the getting it right for every child principles. However, rising demand has made implementation challenging. We have invested in pilots, digital tools and family support, and in our work to take forward recommendations to improve implementation, we are being supported by a newly established cross-sector task force.11

The Committee notes with concern the evidence it has heard about the lack of pathways to support for adults, and for children without co-occuring mental health conditions in some health board areas, and the confusion inconsistencies in available pathways across Scotland can cause for individuals and their families.

The Committee welcomes the Scottish Government's commitment to accept the recommendations set out in NAIT's Adult Neurodevelopmental Pathways report, including the development and implementation of guidance for adult pathways in all HSCPs across Scotland, and to review the implementation of the National Neurodevelopmental Specification for Children and Young People through its new task force.

At the same time, the Committee calls on the Scottish Government to take urgent action to develop and implement a national plan to give adults and children with autism and ADHD across all health boards in Scotland access to clear and consistent pathways to support. This should include continuing to work with NAIT and health boards to implement the recommendations from the pathfinder pilots and delivering an updated Specification for children's pathways.

Treatment thresholds and 'gatekeeping'

A number of written submissions to the Committee’s inquiry highlighted treatment thresholds as one key barrier to accessing neurodevelopmental pathways and support. Treatment thresholds are the criteria that are in place in some areas which must be met before an individual can be referred for a neurodevelopmental assessment. Certain written submissions to the inquiry explained that, in response to increased demand, such thresholds have been raised in certain areas in recent years, meaning triaging must take place before referral to a waiting list for assessment can be made.

In its written submission, NHS Ayrshire and Arran outlined the current situation in its local area:

There are no options for assessment and treatment for children, young people and adults in Ayrshire who have a suspected neurodevelopmental profile but do not meet criteria to access a mental health service.1

Commenting on the use of eligibility criteria to determine access to assessment, auticon argued:

By restricting access in this way, many families may be forced to wait until a child’s condition deteriorates or meets the tighter criteria before entering the system. This risks delaying early identification and intervention, increasing unmet need, and ultimately exacerbating pressure on services in the long term.2

The National Autistic Society Scotland raised concerns that the Scottish Government's focus on a needs-led approach could result in thresholds for assessments being raised, concluding:

We would advise that any new approach should be thoroughly tested and evaluated, involving autistic people, and we would strongly caution against making the threshold for assessment too high.3

Representing the Royal College of Psychiatrists in Scotland, Dr Pavan Srireddy argued that early intervention is important at whatever stage an individual seeks help:

I add that early intervention is not only about intervening early in an individuals' life; it is just as applicable to an adult who is in their 30s or 40s. It is as much about recognising a need and putting modifications in place to prevent someone from developing other mental health disorders, or from presenting in crisis to mental health services with far more significant mental disorders that might require greater intervention ... Putting support in place and having access to such support early on still constitutes early intervention while people are waiting for a diagnosis.4

Dr Chris Williams from the Royal College of General Practitioners in Scotland argued "it is neither appropriate nor feasible for all individuals with mild traits to receive specialist assessment and diagnosis".4 He suggested that the Scottish Government should run a public awareness campaign including guidance on when specialist assessments are necessary, support for self-management and signposting to community based third-sector resources. He went on to say that the burden of managing public expectations in the context of long waiting times was falling to GPs and argued that this "risks undermining the doctor-patient relationship".4

Bill Colley from the Scottish ADHD Coalition argued for a more nuanced approach to determining pathways to treatment:

Quality of life ought to be a major consideration, rather than there being the hard criteria of severity and complexity that are set down at the moment. In the criteria, quality of life ought to be a major consideration, rather than there being the hard criteria on severity and complexity that are set down at the moment. The question, particularly with a condition such as ADHD, which is treatable, is whether treatment could improve the person’s quality of life.7

Several respondents to the Committee's call for views described the experience of being told they did not meet the threshold for assessment as distressing. When asked what could have made their experience better, one respondent said: "Not being dismissed as 'not being bad enough' when I was at the point of life being truly unbearable". Another questioned: "Why must Autistic/ADHD people reach crisis before [being] assessed?"8

Many written submissions to the inquiry described the use of treatment thresholds as a form of 'gatekeeping'. They also argued that some people within the workforce who act as 'gatekeepers' lack appropriate training. In particular, many people with lived experience raised concerns that outdated ideas about how autistic people or people with ADHD present remain prevalent amongst GPs, other healthcare professionals, teachers and other educational staff who are involved in referrals for neurodevelopmental assessments.

During oral evidence, Mark McDonald from Scottish Autism described the challenges autistic people and/or people with ADHD can face:

A gatekeeping process, which often results in them coming up against lack of knowledge, a lack of understanding or outdated understanding. For example, a lot of traits that people might look for in an assessment can be based on outdated thinking. We have heard testimony from people who have said that they were told that they were not getting a referral for an assessment because they were able to maintain eye contact. That is extremely outdated thinking, but it exists out there and it results in people having doors closed to them.7

Many contributors to the inquiry pointed out that certain groups of people such as women, girls and people from ethnic minority backgrounds were less likely to be identified as being autistic or having ADHD and argued this may be because they often do not present in the 'stereotypical' way. As Lyndsay Macadam from SWAN Scotland explained during oral evidence: "Autism can present very differently across genders for a number of reasons".7

One individual who responded to the Committee's call for views, described their own negative experience of gatekeeping:

When I approached my GP about ADHD symptoms, having recognised that what I'd attributed to depression was actually ADHD-related difficulties, her response was sympathetic but ultimately dismissive. She refused NHS referral, stating that because I'm a professional with a degree who holds employment, I wouldn't be seen. This discriminatory gatekeeping ignores how adults, particularly women, develop masking strategies whilst struggling significantly.8

A number of older women who responded to the call for views highlighted the particular struggles they had experienced with accessing support. For instance, one individual commented:

I was told that at 56, I should be able to cope by now—and was even asked if I was just seeking medication. That left me feeling like I was wasting her time ... ADHD doesn’t go away just because we’ve reached a certain age. Everyone deserves to be listened to and supported—especially when they finally find the courage to ask for help.8

During oral evidence, Sofia Farzana, representing Scottish Ethnic Minority Autistics (SEMA), described the particular experiences some ethnic minority women can have when seeking support:

Masking is extremely high if you are black or brown and female, because of the way that, in our communities, the gender roles are so defined. A lot of the autistic women that I speak to say that they have been told since childhood that they are too masculine to be girls ... When we ask for support, the difference in our culture as autistic people is put down to racial culture ... Given how I am dressed, no one can assume when I last brushed my hair. I have it tied up, so who knows? The way I dress is all masked up [Sofia wears a hijab] and that is my culture and I have been brought up in a way to mask everything anyway. It is a complete lack of understanding when a clinician says, “She does not have high support needs” and does not even acknowledge that support needs can fluctuate. They presume things and they do not understand ... We have got to this point for survival’s sake because, as racialised autistics or as racialised people, we have just been told to get on with it.7

In their written submission, SEMA described negative experiences of interacting with health professionals, particularly GPs:

GP’s are gatekeepers. GP’s need more equality, diversity and inclusion training. They need to have more cultural competent training. This training needs to be from professionals with lived experience. For young people, teachers’ lack of understanding can be barrier to assessment referrals and delays diagnosis to even go beyond child to adult transitions. Improvement in teacher training from lived experienced professionals is needed ... experiences with GP’s and psychiatrists have been negative with dismissive remarks, and not progressing referrals. Lack of overall understanding of autism and ADHD in women in is poor […] Lack of believing patients has been a problem for many people.14

Some who responded to the Committee's call for views raised concerns that, due to a lack of suitable training for teachers and other educational professionals, the requirement for a child to be referred by their school to be able to access a neurodevelopmental assessment could be an issue:

Schools have been placed in a position where they are the gatekeepers to assessment. We approached our GP at one point and were advised referral to CAMHS from them would most likely be declined and that indicators from school are essential to acceptance. However, I am unsure if teachers have access to sufficient training to recognise more subtle features of autism. I also think there is a lack of understanding of Autistic Masking. I fear that schools are over-stretched and that there may be a bias against assessment as this places an onus on schools to meet those additional needs.8

Many witnesses also recommended that further training for the workforce involved in providing assessments should be implemented consistently across the country. Recommendations included that the training should be developed in close collaboration with autistic people and people with ADHD and should be mandatory.

Gill Kidd from Child Heads of Psychology Services suggested that an overall competency framework should be developed with different levels of training prescribed depending on the skills needed for particular roles. She argued that this should include training suitable for all roles, from receptionists to GPs to teachers, "right through to what you need if you are diagnosing and doing specialist assessment".4 She suggested that the National Trauma Training Programme, which was developed by NHS Education for Scotland (NES) could be drawn on as an example framework for this purpose.

During an oral evidence session, the Minister for Social Care and Mental Wellbeing highlighted existing training such as the NES Foundations of Neurodiversity Affirming Practice webinar that he argued should be routinely utilised by professionals working with neurodivergent people.

At a separate point, the Minister highlighted the importance of ensuring that gate keeping does not become a barrier to access to support:

Education and local authorities should not be using the need for a diagnosis as a way to gate keep access to services.17

The Committee recognises that the scale of demand for neurodevelopmental assessments has made it necessary to put certain thresholds in place before a referral is made and that this has resulted in gatekeeping access to assessments in some areas.

However, the Committee has been concerned to hear evidence that many people feel those responsible for referrals and gatekeeping do not have an accurate, up to date understanding of neurodevelopmental conditions and how they present, particularly in women, girls and ethnic minority people, meaning that thresholds may not be applied fairly or appropriately in some cases.

The Committee is further concerned that an over-reliance on threshold setting and gatekeeping risks resulting in many individuals being unable to access the support they need at the appropriate time, leading to a situation where these individuals will then present themselves at a later stage having reached a state of crisis, which can be considerably more difficult and costly to treat. The Committee concludes that, although perhaps understandable when trying to deal with consistently high demand, such an approach to managing access to pathways risks being counterproductive in the longer term.

The Committee therefore calls on the Scottish Government, in responding to this report, to set out how it intends to address this challenge and to ensure Health Boards shift their focus to a progressive approach which ensures the provision of treatment and support for autistic people and/or people with ADHD at the earliest opportunity, in line with the principles of its Population Health Framework.

The Committee further recommends that the Scottish Government takes action to ensure improved consistency and timeliness across Scotland of access to treatment and support, including an assessment or diagnosis where appropriate.

To further improve quality and consistency, the Committee calls on the Scottish Government to develop a plan to deliver mandatory training to all those who are involved in making referrals to neurodevelopmental pathways. This training should:

be developed in collaboration with people with neurodevelopmental conditions

draw from existing resources already developed by NES, NAIT and in health board areas where appropriate

be monitored and reported on to determine rates of uptake.

More broadly, the Committee recommends a programme of mandatory training on neurodevelopmental conditions for all health and social care staff in patient-facing roles.

Open referral

Self-referral, open referral or 'requests for assistance' were all suggested in written and oral evidence as alternative ways for people to access specialist support or assessment without the need to obtain a formal referral from their GP or school. In reference to these alternative pathways, Mark McDonald from Scottish Austism told the Committee: "It is helpful to have a pathway that people can refer themselves into without having to go through a gatekeeping process".

In their written submission to the Committee, NAIT highlighted the benefits of open referrals, when provided for in accordance with best practice:

Open referrals or requests for assistance allow families or individuals to self-refer, or schools as well as health professionals to make the request for neurodevelopmental assessment. Where this works well, there is clear guidance and information for those making requests about the information needed to proceed. NHS Dumfries and Galloway is a good example of this practice. Local areas have been concerned that having an open-referral process will ‘open the floodgates’ but the evidence from Dumfries and Galloway and in Grampian adult autism team is that this does not happen. The demand or need is similar to other areas, but the outcome is better conversations earlier, with the right people and a better ‘patient flow’.1

Louise Bussell from NHS Highland cautioned against setting an expectation that self-referral would necessarily enable patients to access support or treatment more quickly, pointing out that resources to deliver such support and treatment would remain finite. Dr Cath Malone from NHS Tayside told the Committee she was concerned that, if an open referral process were adopted in her health board area, the resulting volume of open referrals would be unmanageable. She suggested that improved data and evidence was needed to be able to assess the extent to which open referrals should be encouraged by health boards across Scotland. She went on to argue that, in the absence of an open referral model, "appropriate triage means that the right people are getting assessments in a timelier way".2

Dr Gill Kidd from Child Heads of Psychology Services argued that triage could still take place as part of an open referral approach:

Open referral is a request for assistance for support and understanding of the strategies. In some areas, that is a new way of working that we can build on, spread and expand. To go back to the point about stepped and matched care, that is needed at the point where parents and education are requesting that support. Easy access to that would reduce the need for referrals for a diagnosis when that is not the requirement, but we also need a way of stepping up requests where a diagnosis and a formal assessment are required. NHS Fife is working that kind of model, where there is open access for support but there is also the mechanism to refer in when further assessment is required.2

The Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists were supportive of an open referral model in their written submission:

'Request for assistance’ models, which replace traditional referrals with an open referral system with timely triage, have long been implemented by SLT services across Scotland and are showing great results when used in neurodevelopmental services. Neurodevelopmental assessment pathways in Fife and Dumfries & Galloway, which both have strong SLT representation in the pathway leadership teams, are excellent examples of good multi-disciplinary collaboration and working relationships. They have challenged professional assumptions that an open referral system will open the flood gates to inappropriate referrals, when in fact it means effective conversations happen earlier and individuals get the support they need sooner, including while waiting for an official diagnosis.4

The Committee notes concerns from many healthcare practitioners that broader application of an open referrals model for accessing ADHD and autism pathways would create a risk of "opening the floodgates" to even greater demand and a rise in inappropriate referrals that would be liable to overwhelm services.

At the same time, the Committee notes a strong desire from many individuals to have the option of open referral available to them. It further notes evidence from certain areas where an open referral model is already in place which suggests concerns about services being overwhelmed are not borne out by experience on the ground. Instead, there is strong evidence to suggest an open referral model can help pathways and services to operate more efficiently and responsively.

The Committee therefore calls on the Scottish Government, in responding to this report, to set out what further action it is taking or plans to take to gather further data about the practical impact and any specific benefits for pathways and services of allowing open referrals, to learn appropriate lessons from experience of open referrals on the ground and to explore how open referrals can be made more widely available across Scotland in a way that allays workforce fears that this will result in services being overwhelmed.

Beyond this, the Committee would encourage the Scottish Government to explore how, in future, processes for open referral can be better integrated into national standards for ADHD and autism pathways and support.

Waiting

Waiting lists

In March 2025, the Committee wrote to each of the fourteen NHS territorial boards requesting information on neurodevelopmental pathways and waiting times and received a response from every board. National waiting list data for neurodevelopmental assessments are not routinely published in Scotland. It should be noted that the data provided below only includes those waiting for assessment, not those who may have requested support but did not meet the criteria for referral for an assessment.

As of 31 March 2025, all health boards (with the exception of NHS Tayside, who were not accepting new referrals) had established neurodevelopmental pathways for children who didn't meet the criteria for referral to CAMHS. Thirteen of the fourteen health boards reported the number of patients waiting for this service (except for NHS Grampian, who could not provide this figure as they did not have the ability to separate out the requested data on their patient management system). In general, the data received from NHS boards was not in a uniform or easily comparable format (please see para 216 for the Committee's recommendation in relation to this). The data show that there were 42,530 children waiting for a neurodevelopmental assessment as of that date (see Figure 1).

Eight health boards (Ayrshire and Arran, Fife, Lothian, Tayside, Borders, Forth Valley, Greater Glasgow and Clyde and Highland) were able to provide data on the length of waiting lists in previous years, although only the first four provided data going as far back as 2020. The number of children waiting for a neurodevelopmental assessment in Ayrshire and Arran, Fife, Lothian and Tayside increased from 2,475 to 14,943 between 2020 and 2025 - an increase of over 500%.

Six health boards reported having a neurodevelopmental pathway that is available to adults who do not meet the criteria for referral to secondary mental health services (Greater Glasgow and Clyde, Lanarkshire, Lothian, Tayside, Highland and Western Isles). However, it should be noted that, in the case of Tayside and Western Isles, this pathway was only available for support with or assessment for autism. Provision across the three Health and Social Care Partnerships (HSCPs) covered by NHS Grampian was variable since Aberdeenshire HSCP ceased its adult neurodevelopmental pathway in February 2025.

Nine health boards disclosed the number of adults waiting for a neurodevelopmental assessment in their areas. This included five of the health boards with adult neurodevelopmental pathways in place (Greater Glasgow and Clyde, Highland, Lothian, Tayside and Western Isles but not Lanarkshire) and four of the boards which offered neurodevelopmental assessments only to those who met the criteria for referral to secondary mental health services (Ayrshire and Arran, Fife, Orkney and Shetland).

There were 23,339 adults reported as waiting for a neurodevelopmental assessment as of March 2025 (See Figure 2), and over 97% of these were in areas where adults did not have to meet the criteria for referral to secondary mental health services to access these services. The number of adults waiting for a neurodevelopmental assessment across Forth Valley, Highland, Lothian and the Western Isles increased by more than 2200% in five years, from 543 in 2020 to 12,974 in 2025.

All health boards reported the median and longest current waiting times for children seeking a neurodevelopmental assessment, except for NHS Grampian (which could not provide data specific to neurodevelopmental cases) and NHS Dumfries and Galloway (which provided a longest waiting time only). Median waiting times ranged from 22 weeks (NHS Western Isles) to 141 weeks (NHS Ayrshire and Arran), with an average median waiting time for children across all health boards providing data of 76 weeks. Longest waiting times ranged between 69 weeks (NHS Fife) and 342 weeks (NHS Ayrshire and Arran), with an average longest waiting time for children across all health boards providing data of 196 weeks.

Nine health boards (Lothian, Ayrshire and Arran, Tayside, Forth Valley, Highland, Fife, Shetland, Orkney and Western Isles) reported both the median and longest waiting time for an adult seeking a neurodevelopmental assessment, while Greater Glasgow and Clyde reported the longest waiting time only. Forth Valley, Tayside and Fife reported waiting times for autism assessment only. Ayrshire and Arran and Western Isles reported the combined average from the median waiting times for autism and ADHD individually. Median waiting times ranged from 24 weeks (NHS Orkney) to 146 weeks (NHS Tayside), with an average median waiting time for adults across all health boards providing data of 76 weeks. Longest waiting times for adults ranged between 61 weeks (NHS Fife) and 390 weeks (NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde), with an average longest waiting time for adults across all health boards providing data of 182 weeks.

Speaking to the Committee during an oral evidence session, Dr Pavan Srireddy from the Royal College of Psychiatrists in Scotland highlighted the significant rise in demand for services:

We must recognise the sheer scale of what we are discussing. The increases in referral rates, in demand and in the numbers of young people and adults awaiting diagnosis are beyond anything that we have seen in the recent history of our healthcare systems apart from during the Covid pandemic ... The reality on the ground is that our healthcare model is designed to meet the needs of 1 per cent of the population, but it is trying to meet the needs of more than 20 per cent of the population. That cannot and will not work.1

Impact of waiting times

Oral and written evidence submitted to the inquiry suggests that long waiting periods can be distressing and harmful for individuals and their families. In its written submission, Children's Health Scotland argued that “children's wellbeing deteriorates during long waits for diagnosis, with increased anxiety, school refusal, and social withdrawal”.1

Other responses to the Committee's call for views supported this view, with one respondent describing their daughter's negative experience of waiting for an assessment and support:

My daughter was referred for neurodevelopmental assessment in Primary 5 by her new head teacher ... That was four and a half years ago. She’s now 13 and has just entered S3 in high school, still without a diagnosis or the support she needs. In that time, she has withdrawn socially, been bullied for thinking differently, and repeatedly placed in isolation because staff don’t know how to manage her needs. She was 9 when referred; now she’s navigating adolescence and hormonal changes without the understanding or tailored help she deserves. This delay has had a profound impact on her mental health, education, and self-esteem. We have been left to cope alone, misunderstood and unsupported, while her potential remains untapped. I am deeply concerned about the long-term consequences of this delay and the emotional toll it continues to take.2

Another respondent described their experience of lengthy waiting times as an adult:

I’ve been waiting 3 years. When I first went on the register for assessment I was told about 18 months, then it’s just kept being pushed back. I phone about every 6 months and record the date I phone and the new time they expect me to be seen. It’s ridiculous ... I feel stuck in this limbo and it is very frustrating.2

During an oral evidence session, Dani Cosgrove from STAND described similar experiences of families her organisation supports:

We hear from our families that the longer they wait for the assessment, the longer it is before their child’s needs are fully met and properly understood. Children are losing years of development, families are being left in limbo and support is being delayed or withheld. A parent spoke to me last week and described the waiting period as "physically and emotionally torturous".4

In further correspondence to the Committee, STAND highlighted that children face exclusion from activities while waiting for support:

During this time, many children are excluded from school activities, parents reduce or leave work and mental health deteriorates. The waiting period is not neutral; it is actively damaging.5

Several respondents to the call for views described experiences of children "ageing out" of the children's waiting list before being seen and then having to join the bottom of an adult waiting list. The transition from childhood to adulthood was recognised as a crucial point in a young person's life where a lack of appropriate support could leave them especially vulnerable.

Many contributors to the inquiry suggested that individuals and families waiting for an assessment or further support were not given necessary information and that communication was generally poor.

One respondent to the call for views commented:

Not knowing roughly how long each stage would take was one of the most difficult and frustrating parts of the process. There was a lot of waiting with very little communication.2

Another argued:

If the wait times cannot be changed more open and honest communication would at least [allow] parents to know where they stand in this regard.2

In its written submission, the Autistic Rights Group Highland (ARGH) reported similarly negative experiences from people on waiting lists for assessment:

They are given no support and receive no or very poor communication whilst waiting for an assessment, they feel abandoned and that they are expected to 'just get on with life' but cannot just get on and often feel that their life is falling apart. Once someone finally receives an assessment, even if they are diagnosed the wait is not over: people can wait months for a further appointment to receive medication (ADHD) or just be given a leaflet and told to get on with it (often the materials handed out are out of date and / or far from neuroaffirming).8

One individual with lived experience who participated in an informal engagement session as part of the Committee’s inquiry said that "what helped them during this period was not access to medication but rather rest and exercise – and it would have been beneficial to have received more advice about that".9

Several respondents with lived experience of being on a waiting list for assessment explained that one of the only pieces of communication they received during this time was a letter asking them to confirm if they still wanted to be on the waiting list and telling them they would be removed from the waiting list if they did not respond within a certain time frame. During an informal engagement session as part of the inquiry, one participant described how difficult it can be for people with ADHD, who struggle with executive function, to deal with such a process. On receiving one such letter, this participant described putting it away and forgetting about it and explained this would be typical behaviour for someone with ADHD.

Witnesses reported pockets of good practice such as "waiting well" initiatives but went on to argue that there are no consistent standards across the country. Thelma Bowers from NHS Ayrshire and Arran informed the Committee that her health board has established a Neurodevelopmental Empowerment & Strategy Team (NEST) which has developed a central hub for online resources and information, and also runs workshops. She went on to describe having "worked with the third and independent sector to create alternative supports and options such as physical activities and programmes of therapy while young people are waiting".10

Anya Kennedy from the Royal College of Occupational Therapists told the Committee she was aware of several projects across the country to develop resources for people with neurodevelopmental conditions, including some that have been developed by NAIT. She suggested:

We need to try to work smarter with the resources that we have. A once for Scotland approach allows us to pool resources and skills from across Scotland, and not just work within individual board areas.10

Dr Pavan Srireddy from the Royal College of Psychiatry argued that "curated, good-quality information gives people the ability to access help and support based on what their needs are at that time".10 He suggested there is currently an over-reliance on social media as a source of information and that this can sometimes be inaccurate or harmful.

Some witnesses also mentioned that lengthy waiting lists have had a negative impact on staff wellbeing and morale. Thelma Bowers from NHS Ayrshire and Arran told the Committee:

There are still waits, which create burnout in our team and a sense of moral injury from not being able to support people in the way that clinicians would want to. Because people either cannot get a diagnosis or they have a long wait—which could be two and a half years—we receive a lot of complaints and inquiries, which our team have to deal with at the same time".10

Similarly, Louise Bussell from NHS Highland said:

It is also important to note the number of complaints that come in from families. It is often the people at the front door—the folk on reception and in admin roles—who absolutely bear the impact of people contacting them, asking “What is happening?” and, understandably, being very unhappy.10

In oral evidence to the Committee, the Minister for Social Care and Mental Wellbeing said:

My clear expectation is that anyone who is waiting for assessment should be sensitively signposted to support that is available.15

Reasons for long waiting times

The Committee heard both oral and written evidence that waiting times for ADHD and autism assessments have increased at an unprecedented rate in recent years due to increased awareness and understanding of neurodevelopmental conditions. Several witnesses told the committee that this is partly due to 'historical underdiagnosis' particularly amongst older generations and women.

Several witnesses mentioned that they were aware of a narrative developing that ADHD and autism is being over-diagnosed and were keen to dispel this idea. In this context, Rob Holland from National Autistic Society Scotland expressed the following concern:

Sometimes the debate in this space is focused on reducing referrals rather than making sure that we tackle the issue here. The issue is not a problem of demand; it is a problem of supply and ensuring that we have the right number of assessments and the right level of support.1

Bill Colley from the Scottish ADHD Coalition argued that statistical data points to an under-diagnosis of ADHD in the population. He pointed to research suggesting prevalence of ADHD in children is estimated to be between 5-7%, meaning that between 73-81% of children who have ADHD are not diagnosed. Furthermore, he said that estimates suggest 2-4% of the adult population have ADHD, meaning that 91-96% of this population are not diagnosed. He concluded: "Given that ADHD is a treatable condition, the vast majority of people who have it have not been assessed and diagnosed and are, therefore, not receiving treatment".1

Written evidence submitted to the Committee suggests that healthcare systems are not prepared for the considerable increase in demand for support and assessments currently being experienced. Contributors to the inquiry argued that a lack of funding and an appropriately skilled workforce are two of the main reasons why waiting times are so lengthy.

Louise Bussell from NHS Highland encapsulated this view:

Workforce challenges have a massive impact on our waiting times; they are the most significant factor in why we have the waiting times that we do. There are multi-faceted reasons for that. They are not all about being able to get people for the roles; they also include having the finance in place ... there is a small market for such positions, because only a small number of people can currently do that work. We need to build a much greater workforce, but first we need the finance to enable us to do so.3

Representing Child Heads of Psychology Services, Dr Gill Kidd agreed that there are gaps in the workforce and went on to describe the impact this is having on CAMHS services:

There are workforce bottlenecks, in particular around prescribing. There are insufficient medical and non-medical prescribers to meet the demand. Even if we diagnose ADHD, for example, there will still be a wait for prescribing and treatment. The diagnostic process generally sits with a small number of people so we have bottlenecks there, too. As I said, some of those services sit within CAMHS. Although the workforce and the skills might be there, some services have not been able to direct capacity to neurodevelopmental services because of the need to also address the waits for mental health services, so we are confounding two workforces.3

Witnesses also highlighted short term availability of funding as a particular issue when trying to plan longer term improvements to services. They also reported particular challenges with recruiting qualified staff because temporary posts are generally less attractive than more secure long term or permanent posts. While short term funding for pilots was welcomed, many felt that longer term funding commitments were needed to be able to embed improvements. Dr Gill Kidd advocated a multi-agency approach where the allocation of funding was integrated across "education, social work, children's services and CAMHS" as well as healthcare.3

Giving oral evidence to the Committee, the Minister for Social Care and Mental Wellbeing emphasised the Scottish Government’s commitment to addressing the issue of long waiting lists through a multi-agency approach:

Neurodevelopmental needs span health, education and social care, and they are shaped by a wide range of factors. A traditional national health service waiting list approach is not sufficient. What is needed is a coordinated multi-agency response that focuses on timely, needs-based support and reflects the evolving nature of neurodevelopmental needs and the diversity of individual experiences. The Scottish Government is committed to improving access to timely, needs-based support for neurodivergent people.6

The Committee has been extremely concerned to hear evidence during this inquiry of many individuals having to wait many years on a waiting list for assessment for ADHD, autism and other neurodevelopmental conditions, as well as evidence from many areas where waiting lists have now been closed. It is firmly of the view that, as well as being detrimental to the individuals affected, such a situation is damaging to wider society to which, for as long as they fail to receive the support and treatment they need, these individuals may be prevented from making an active and positive contribution.

The Committee acknowledges evidence of an unprecedented rise in demand for neurodevelopmental assessments in recent years. It has been persuaded by evidence that this rise is not attributable to a tendency towards over-diagnosis but rather to an historic under-diagnosis of ADHD and autism and an improved understanding of these conditions more recently. The Committee is also sympathetic to the suggestion that promoting a narrative around over-diagnosis is unhelpful and risks further stigmatising those with autism and/or ADHD, with the result that their condition is not believed or understood and they are denied access to the pathways and support they need.

Given the current length of waiting times, the Committee believes it is particularly crucial that the quality of communication with those on waiting lists is consistently high, that available information is accurate, supportive and up-to-date, uses neuro-affirming language and is delivered in a way that is responsive to the specific needs of those with autism and/or ADHD.

For the same reason, the Committee calls on the Scottish Government to give much greater attention, including the commitment of appropriate resources, to the development of "waiting well" initiatives that provide suitably targeted access to good information and local support as a consistent and integral part of the waiting process for those on neurodevelopmental pathways.

The Committee welcomes the Scottish Government's establishment of a task force and its commitment of additional funding to support implementation of the National Neurodevelopmental Specification. As part of this work, the Committee calls on the Scottish Government to produce a roadmap setting out clear timelines for improvement of ADHD and autism pathways and support. This should address improvements to information and communication (including the potential establishment of a 'one stop shop'), improved access to local support while waiting, the roll-out of targeted "waiting well" initiatives and the commitment of funding to develop the multi-disciplinary workforce needed to reduce waiting times in the longer term.

Assessment and diagnosis

Assessment process