Health, Social Care and Sport Committee

Stage 1 report: Assisted Dying for Terminally Ill Adults (Scotland) Bill

Membership changes

The following changes to Committee membership occurred during the Committee's scrutiny:

On 18 June 2024, Joe FitzPatrick MSP replaced Ivan McKee MSP.

On 10 October 2024, Brian Whittle MSP replaced Tess White MSP.

On 30 October 2024, Elena Whitham MSP replaced Ruth Maguire MSP.

The following declarations of interest were made during the Committee's scrutiny:

Dr Sandesh Gulhane MSP declared an interest as a practising NHS GP and as chair of the Medical Advisory Group set up to advise and inform the Member in Charge of the Bill in advance of its introduction.

Emma Harper MSP declared an interest as a former NHS Scotland and NHS England employee and as a registered nurse.

Clare Haughey MSP declared an interest as holding a bank nurse contract with NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde, as being currently registered with the Nursing and Midwifery Council, and as having commissioned the Scottish Mental Health Law Review when she was a Minister.

Elena Whitham MSP declared an interest as a member of Humanist Society Scotland, as a member of the Cross-party group on End of Life Choices, and as a Canadian citizen.

Executive summary

This report sets out the results of the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee’s scrutiny of the Assisted Dying for Terminally Ill Adults (Scotland) Bill at Stage 1.

The Committee acknowledges strongly held views on all sides of the debate on assisted dying, which it has considered carefully as part of its Stage 1 scrutiny. We are grateful to everyone who has contributed to our scrutiny and acknowledge the considered and respectful way in which individuals and organisations have done so.

There is broad recognition across the Parliament that the proposed legalisation of assisted dying is a matter of conscience. On that basis, the Committee has chosen to make no overall recommendation concerning the general principles of the Bill.

At the same time, the Committee has identified a number of areas which it has concluded would benefit from further consideration as part of formal Stage 2 proceedings, should the Bill be approved at Stage 1.

Palliative care provides physical and emotional support to people at the end of life. The Committee believes that everyone who needs it should be able to access good quality palliative care at the end of their lives. Regardless of the outcome of this Bill, we hope the current debate will provide a catalyst for further improvements to be made to the quality and availability of palliative care services in Scotland.

The Committee has considered those human rights under the European Convention on Human Rights that are engaged by the Bill. We have concluded that the following will be important factors that inform individual members of the Scottish Parliament in deciding how they wish to vote on the general principles of the Bill:

the likelihood and seriousness of a perceived risk that the Bill may be subject to human rights based legal challenge that could result in eligibility for assisted dying being extended over time; and

the extent to which it strikes an appropriate balance between providing a right for terminally ill adults to access assisted dying and the requirement to protect vulnerable groups.

If the Bill progresses to Stage 2, we have also concluded that the safeguards in the Bill and its compliance with human rights requirements could be strengthened via amendments to establish an independent oversight mechanism such as an independent review panel or a potential monitoring role for the Chief Medical Officer.

On balance, we are satisfied with the rationale of Liam McArthur (as the member in charge of the Bill) for not including a timescale for life expectancy in the definition of terminal illness. However, the following areas may require further clarification should the Bill progress to Stage 2, to ensure this definition meets its intended purpose:

the minimum age-related eligibility criterion, currently proposed as 16, where key stakeholders and young people should be consulted as part of that further consideration; and

the residence criterion, where we welcome Mr McArthur’s willingness to consider potential amendments at Stage 2.

We believe the issue of capacity would benefit from further consideration via amendment should the Bill progress to Stage 2, including:

further reflection on the resource implications for the medical professions of assessing capacity of those requesting assisted dying;

ensuring the capacity of people with a mental disorder is assessed in a way that is fair and non-discriminatory while also giving suitable protection for vulnerable individuals; and

defining how eligibility for assisted dying will be determined for those with fluctuating capacity.

In respect of the process through which individuals can make an initial request for assistance, we believe amendments may be needed should the Bill progress to Stage 2 to address the following:

ensuring suitable legal clarity and protections for medical practitioners, whether they choose to raise assisted dying with their patients or not;

exploring additional safeguards against so-called 'doctor shopping'; and

giving healthcare professionals and individuals requesting assisted dying access to tailored psychological support.

We recognise that the period of reflection in the Bill can be reduced to no fewer than 48 hours in certain circumstances. However, we believe further consideration should be given to whether a default 14-day period of reflection is appropriate.

We recognise practical concerns about the provisions of the Bill on signing by proxy. We recommend that these are addressed via amendment should the Bill progress to Stage 2, based on further advice from the legal profession.

We welcome Liam McArthur’s preparedness to consider further those sections of the Bill that relate to the provision of assistance. We have concluded that a combination of Stage 2 amendments and detailed guidance on self-administration and provision of assistance would be needed. These will be crucial to ensuring absolute clarity and appropriate protection for all parties involved, should the Bill become law.

We have also concluded that, should the Bill become law, both the condition which led to a request for assisted dying and the administration of an approved substance to enable an assisted death should be recorded on the death certificate of the individual concerned. This will provide transparency and aid data collection.

We recognise Mr McArthur’s intention that assisted dying should be delivered via a service model that enables integration with existing services rather than being provided as a stand-alone service. If it becomes law, it will be important to monitor the impact of the Bill on existing healthcare services over time. If the Bill progresses to Stage 2, we believe it may also be appropriate to explore via amendments whether specific aspects of assisted dying would be better delivered on a stand-alone basis, in particular to ensure consistent access across the country.

Should the Bill progress to Stage 2, we believe further attention should be given to amending the wording of the conscientious objection clause in the Bill. This is needed to ensure it provides an appropriate level of legal clarity and certainty for all parties involved in the assisted dying process.

Where health practitioners exercise a conscientious objection, we believe there should be a minimum expectation that they will refer patients requesting assisted dying on to a colleague who does not share such an objection. As a bare minimum, they should provide additional information about the process. We note concerns that creating a 'no duty' clause (meaning those exercising a conscientious objection would not be required to refer patients on) could create unreasonable barriers to access to assisted dying.

We believe the potential inclusion of a 'no detriment' clause would merit further investigation via amendment should the Bill progress to Stage 2. The purpose of such a clause would be to protect healthcare staff from workplace discrimination due to their involvement or non-involvement in assisted dying.

We have noted Mr McArthur’s willingness to explore further the possibility of creating an 'opt-in' model of participation in assisted dying for health practitioners. We consider this to be an area that may warrant further debate and amendment if the Bill progresses to Stage 2.

Irrespective of whatever position the Parliament takes on allowing or prohibiting institutional objection, we believe amendments will be needed should the Bill progress to Stage 2 to provide further clarity so institutions understand how they will be permitted to act should the Bill become law.

There are significant discrepancies in estimates of training costs associated with the Bill. These costs may also vary significantly according to a number of factors. Should the Bill become law, we would expect the Scottish Government to set out how it intends to meet the associated costs of training in a way that does not negatively affect available funding for existing services.

We have taken a particular interest in potential alternative models for assessing coercion, such as that created in relation to living donors by the Human Tissue Act 2004. We believe such alternative models should be explored further via amendments should the Bill progress to Stage 2.

We welcome Mr McArthur’s preparedness, should the Bill be approved at Stage 1, to consider mechanisms for reviewing and updating guidance on coercion. This will ensure health practitioners are suitably equipped to assess coercion effectively and to allow the related offence created by the Bill to be appropriately policed.

We note the potential competence-related issues involved in the practical implementation of the Bill. We welcome the Scottish Government’s commitment, should the Bill progress beyond Stage 1, to open dialogue with the UK Government with a view to resolving these. We call on the Scottish Government to keep the Parliament regularly updated on progress.

The Committee believes certain aspects of the information, reporting and review provisions of the Bill may warrant further consideration and amendment should the Bill progress to Stage 2. These include:

additional detail to be included in the forms set out in the Bill’s schedules;

additional information to be collected as part of the review process;

whether five years is an appropriate review period for the legislation; and

potential inclusion of a 'sunset clause', meaning the legislation could not remain in force beyond a defined period without a further vote in the Parliament.

In conclusion, the Committee makes no overall recommendation on the general principles of the Bill. However, we hope this report will be helpful to individual members of the Scottish Parliament in deciding how they wish to vote at Stage 1, and in informing further detailed scrutiny should the Bill progress to Stage 2.

Introduction

A draft proposal for a Member's Bill on Assisted Dying for Terminally Ill Adults was originally lodged in the Scottish Parliament by Liam McArthur MSP on 22 September 2021. A consultation on this proposal ran from 23 September 2021 until 22 December 2021 and received 14,038 responses. Of these, 81 were from organisations. 13,957 were from individuals, including academics, professionals and members of the public.

A summary of responses to the Member's consultation was published along with a final proposal on 8 September 2022. On 10 October 2022, Liam McArthur obtained a right to introduce the Assisted Dying for Terminally Ill Adults (Scotland) Bill in the Scottish Parliament.

After the close of the consultation, the Member in charge of the Bill invited a group of individuals to form a Medical Advisory Group (MAG) to advise and inform him ahead of the Bill being introduced. This was chaired by Dr Sandesh Gulhane MSP and included ten other professionals, experts and academics. The MAG published its report on 12 December 2022 and this was considered as part of the Bill drafting process.

Liam McArthur introduced the Assisted Dying for Terminally Ill Adults (Scotland) Bill1 in the Scottish Parliament on 27 March 2024. In preparing the Bill and its accompanying documents, Mr McArthur was supported by the Parliament's Non-Government Bills Unit.

The Health, Social Care and Sport Committee was designated as lead committee for Stage 1 consideration of the Bill on 16 April 2024.

Under the Parliament's Standing Orders Rule 9.6.3(a), it is for the lead committee to report to the Parliament on the general principles of the Bill. In doing so, it must take account of views submitted to it by any other committee. The lead committee is also required to report on the Financial Memorandum and on its Delegated Powers Memorandum.

Overview of the Bill

The Policy Memorandum1 accompanying the Bill describes the Bill's aim as being:

...to allow mentally competent terminally ill eligible adults in Scotland to voluntarily choose to be provided with assistance by health professionals to end their lives.

The Policy Memorandum further states:

The Bill establishes a lawful process for an eligible person to access assisted dying, which is safe, controlled and transparent, and which the Member believes will enable people to avoid the existential pain, suffering and symptoms associated with terminal illness, which will in turn afford the person autonomy, dignity and control over their end of life.

The Bill contains 33 sections and 5 schedules, which can be broken down as follows:

Sections 1 to 3 establish the lawfulness of the provision of assistance to a terminally ill eligible adult to end their own life, and deal with the criteria which must be met in order for a terminally ill adult to be eligible to request, and be provided with, assistance to end their life in accordance with the provisions of the Bill.

Sections 4 to 14 set out the preliminary procedural steps which must be taken, and how criteria will be assessed and determined, in order for a person to be eligible to be provided with assistance to end their life.

Sections 15 to 20 deal directly with the provision of assistance to an eligible terminally ill adult for them to end their life by self-administered means. This includes provision that there is no duty on anyone, including registered medical practitioners and other health professionals, to participate in the process if they have a conscientious objection to doing so, and also provides that it is not a crime to provide an eligible person with assistance where the requirements of the Bill have been met, and that there is also no equivalent civil liability. These sections also deal with the process after a terminally ill adult has died as a result of taking the substance supplied, including the completion of a final statement and how to record the death on the death certificate.

Sections 21 to 33 deal with general and final provisions which include making it an offence to coerce or pressure a terminally ill adult into requesting an assisted death, provisions relating to the collection and reporting of data, the publication of an annual report, and a requirement to review the Act after five years of operation.

Schedules 1 to 4 contain the forms which are required to be completed, signed and witnessed at various stages of the process. These consist of a first and second declaration form, in which a terminally ill adult asks to be provided with assistance to end their life, two medical assessment statement forms, to be completed by registered medical practitioners, which assess eligibility, and a final statement form, to be completed after a death has taken place.

Schedule 5 sets out criteria that would disqualify a person from being a witness or proxy for the purposes of the Bill.

Further details on the Bill can be found in the Explanatory Notes and Policy Memorandum accompanying the Bill.

Background to the Bill

Legal position

The current legal position differs in Scotland compared to other parts of the United Kingdom in that there is no specific statutory offence of assisting someone’s suicide. By contrast, in England and Wales, under the Suicide Act 1961, and in Northern Ireland, under the Criminal Justice Act 1966, it is not a crime to take your own life, but it is a crime to encourage or assist suicide.

Although assisted dying is not a specific criminal offence in Scotland, a person assisting the death of another person could nonetheless be prosecuted for a range of offences, including murder or culpable homicide.

In England and Wales, all prosecutions for assisting a suicide must have the consent of the Director of Public Prosecutions. The Director of Public Prosecutions has produced specific guidance to outline how the discretion to prosecute will be exercised. There is no similar guidance in Scotland, and the Policy Memorandum concludes that, in Scotland, “...it remains unclear what forms of assistance to die a medic, family member or friend may give to a terminally ill person without fear of being prosecuted”. However, the courts have supported the Lord Advocate’s decision not to produce specific guidance on the basis that the factors outlined in the general Prosecution Code (2023) are sufficiently clear.

Previous attempts to legislate in the UK

There have been multiple previous attempts to legislate on assisted dying in the Scottish Parliament. Jeremy Purvis MSP lodged a proposal for a Member’s Bill in 2005 which failed to gather sufficient support to earn the right to introduce a Bill and subsequently fell. Two proposals lodged by the late Margo Macdonald MSP did secure sufficient support to be introduced as Bills, in 2010 and 2013, but both Bills fell at Stage 1 after failing to secure enough votes from MSPs in support of their general principles.

There have also been a number of attempts to legislate for assisted dying in England and Wales at the UK Parliament via Private Members’ Bills. Bills introduced by Lord Falconer of Thorton in 2014 and by Baroness Meacher in 2021 both fell due to running out of parliamentary time. A Bill introduced by Rob Marris MP in 2015 was defeated at its second reading.

In December 2022, the House of Commons Health and Social Care Committee launched an inquiry into assisted dying/assisted suicide. The Committee published its concluding report on 29 February 2024.

On 5 January 2024, a petition was opened calling for the UK Government “to allocate Parliamentary time for assisted dying to be fully debated in the House of Commons and to give MPs a vote on the issue”. The petition closed for signatures on 5 July 2024. Lord Falconer introduced the Assisted Dying for Terminally Ill Adults Bill in the House of Lords on 26 July 2024.

On 16 October 2024, Kim Leadbeater MP introduced the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill 2024-25 in the House of Commons, having been drawn highest in the private members’ bill ballot for the 2024-25 session. The purpose of the Bill, which would apply to England and Wales, is described as being to “...allow adults who are terminally ill, subject to safeguards and protections, to request and be provided with assistance to end their own life”. Following the introduction of Kim Leadbeater's Bill, Lord Falconer announced he would not progress his own Bill.

The Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill 2024-25 was supported at 2nd Reading on 29 November 2024 by 330 votes to 275. At time of writing, the Bill is currently at Committee Stage in the House of Commons.

Legislation around the world

Around the world, the following countries and jurisdictions are known to have legalised a form of assisted dying or suicide:

Ten American States (Oregon, California, Hawaii, Washington, Colorado, Vermont, Montana, New Jersey, New Mexico, Maine) plus the US district of Washington DC;

All six Australian States (Victoria, Tasmania, Queensland, New South Wales, South Australia, Western Australia) plus Australian Capital Territory;

New Zealand;

Canada;

Colombia;

Belgium;

The Netherlands;

Luxembourg;

Switzerlandi;

Spain;

Portugal.

Meanwhile, a number of other countries and jurisdictions are known to be actively engaged in considerations to legalise forms of assisted dying or suicide.

Within the British Isles, Jersey and the Isle of Man have both recently taken steps towards legislating for forms of assisted dying. On 21 May 2024, the States Assembly of Jersey approved proposals for assisted dying and requested the Minister for Health and Social Services to bring forward primary legislation to permit assisted dying in Jersey for those with a terminal illness; the legislation is expected to be considered by late 2025. On the Isle of Man, a Private Member’s Bill on assisted dying, introduced in 2023, secured support at its second reading and was subsequently scrutinised by an ad hoc Bill committee, which published its report on 28 March 2024. It was subsequently considered by the House of Keys, which voted to approve the Bill at third reading on 23 July 2024, and was then passed (with amendments) by the Legislative Council, the Isle of Man’s upper chamber, on 28 January 2025. On 25 March 2025, the upper chamber approved the Bill at its final reading.

Health, Social Care and Sport Committee consideration

The Committee issued two calls for evidence which were open for submissions between 7 June and 16 August 2024:

a short survey for people who wished to express general views about the Bill as a whole; and

a detailed call for evidence for people, groups, bodies or organisations who wished to comment on specific aspects of the Bill.

The Committee received 13,821 responses to the short survey. Individual responses to this survey were not published. Instead, the Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe) produced a summary analysis of these responses which was published on the Committee's webpage.

The Committee received 7,236 responses to the detailed call for evidence, which were published on Citizen Space. The Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe) also produced a separate summary analysis of these responses.1

On 30 September 2024, the Committee received a letter from the Cabinet Secretary for Health and Social Care including a memorandum setting out the Scottish Government's position on the Bill.2 The letter concludes by stating the Scottish Government's intention to maintain a neutral position on the Bill at this stage while also concluding that "In the Scottish Government’s view, the Bill in its current form is outside the legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament."

The Committee took formal oral evidence on the Bill during November 2024 and in January and early February 2025 (see further Annex A):

On 5 November, the Committee held a private session with representatives of the Non-Government Bills Unit. This was followed by a public evidence session with witnesses in Australia about experiences of implementing assisted dying in that jurisdiction.

On 11 November, the Committee took evidence from witnesses in Canada on experiences of implementing assisted dying in that jurisdiction.

On 12 November, the Committee took evidence from two panels of witnesses, the first comprising legal and human rights experts and the second focusing on mental health considerations related to the Bill.

On 19 November, the Committee took evidence from two further panels of witnesses, the first comprising representatives of healthcare professionals, the second comprising representatives of providers of palliative care.

On 14 January 2025, the Committee took evidence took evidence from two panels of witnesses representing people with long-term conditions and people with disabilities respectively.

On 21 January 2025, the Committee took evidence from two panels of witnesses representing campaign organisations respectively supportive of, and opposed to, the Bill.

On 28 January 2025, the Committee took evidence from the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service and then from the Cabinet Secretary for Health and Social Care (Neil Gray) and supporting officials.

The Committee concluded its oral evidence programme on 4 February 2025 by taking evidence from the Member in Charge of the Bill, Liam McArthur MSP, his adviser and accompanying Scottish Parliament officials.

On 7 January 2025, members of the Committee undertook informal engagement with members of the Scottish Assembly, an organisation that brings together people with a learning disability and autistic people across Scotland and helps them to engage with the political process and a range of support and services. An anonymised note of this informal engagement has been published on the Scottish Parliament website.

To better understand the experiences of individuals living with a terminal illness, the Committee engaged with a number of organisations involved in the provision of frontline care and support to explore options for those that may wish to contribute additional testimony to the Committee’s scrutiny of the Bill. As a result of this further engagement, the Committee received two written testimonies which were published on the Committee website and which members reflected on in public at the Committee's meeting on Tuesday 25 March 2025.

The Committee wishes to thank everyone who contributed evidence to its Stage 1 consideration of the general principles of the Bill.

Consideration by other committees

The Finance and Public Administration Committee issued a call for views on the estimated financial implications of the Bill as set out in its accompanying Financial Memorandum.1 This was open for submissions between 10 June and 16 August 2024 and received 22 responses. On 28 January 2025, the Finance and Public Administration Committee wrote to this Committee setting out the outcome of its scrutiny of the Financial Memorandum:

Our scrutiny of this FM has highlighted potential gaps in the information provided, including underestimates of the direct financial impact as well as of potential wider societal changes. We also found a lack of information on estimated savings that could arise from the Bill. This has led the Committee to conclude that the FM as introduced is not sufficiently comprehensive.

The Delegated Powers and Law Reform (DPLR) Committee considered the Bill at its meetings on 28 May 2024 and 10 September 2024. It published a report on the Bill on 20 September 2024 in which it set out a series of recommendations in relation to the ten powers to make subordinate legislation conferred on Scottish Ministers by the Bill.

Specifically, in relation to the regulation-making powers conferred by section 4(5)(a) (specification of qualifications and experience of the "coordinating registered medical practitioner") and section 6(6)(a) (specification of the qualifications and experience of the "independent registered medical practitioner"), the DPLR Committee recommended that the Bill be amended at Stage 2 to include a statutory requirement for Ministers to consult the Chief Medical Officer for Scotland and the General Medical Council. With respect to the power conferred by section 15(8) (specification of "approved substance"), the DPLR Committee recommended that the Bill be amended at Stage 2 to include a statutory requirement for Ministers to consult the Chief Medical Officer for Scotland.

Views for and against assisted dying

The debate on assisted dying is underpinned by core philosophical concepts such as autonomy, suffering, dignity, and the sanctity of life. Often these concepts are valued by both supporters and those opposed to assisted dying, but the importance placed on each may differ.

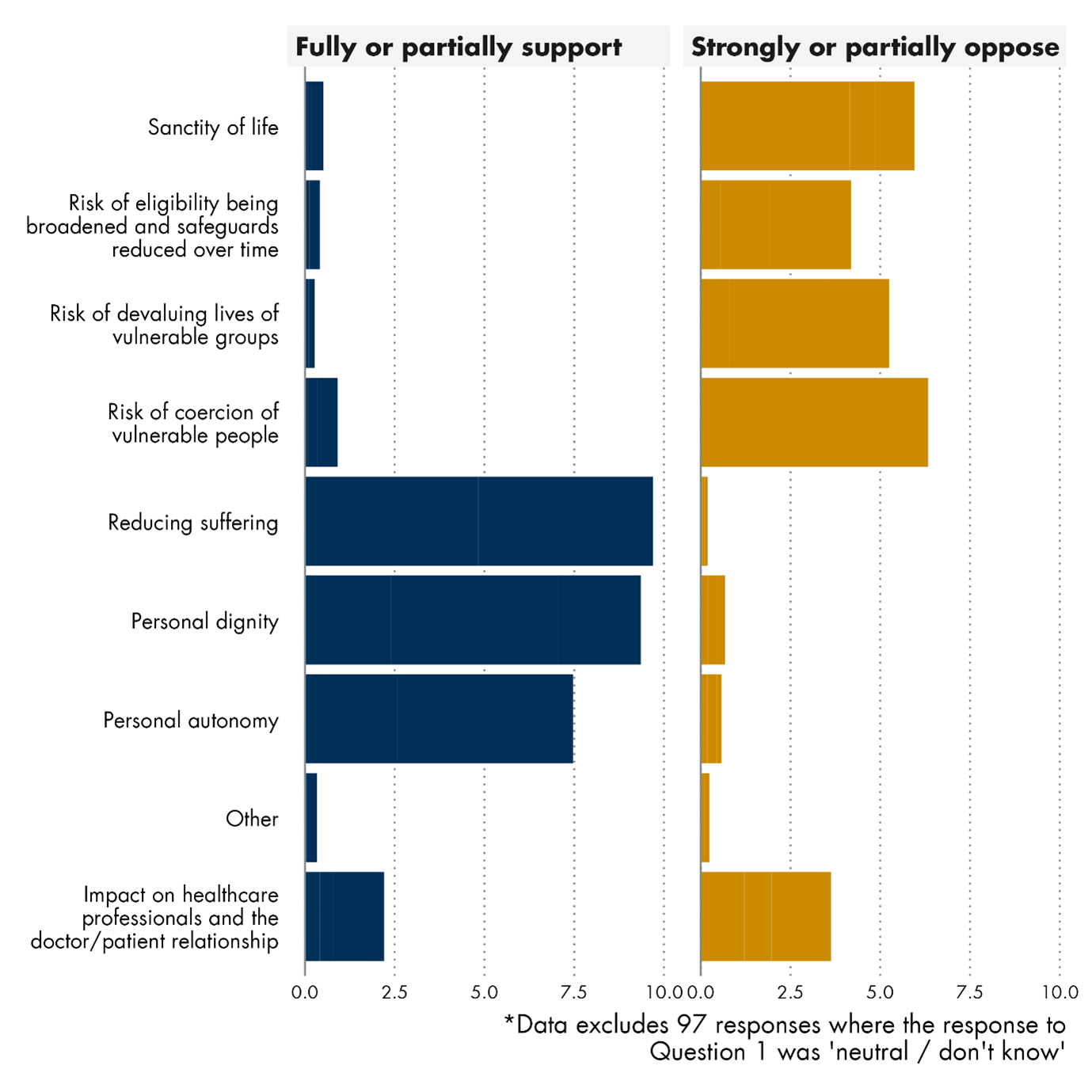

The Committee undertook two calls for views, both of which asked people to rank the three most important considerations which influence their opinion on assisted dying. Respondents were offered the same list of options whatever their stated views on the Bill:

Reducing suffering;

Personal dignity;

Personal autonomy;

Risk of coercion of vulnerable people;

Sanctity of life;

Impact on healthcare professionals and the doctor/patient relationship;

Risk of devaluing lives of vulnerable groups;

Risk of eligibility being broadened and safeguards reduced over time; and

Other – please provide further details in the text box.

The combined ranking showed a noticeable difference between those who support assisted dying and those who oppose it in the level of importance allocated to each of the options.

As summarised in figure 1 (below), the most important factors for those expressing support for assisted dying were:

reducing suffering;

personal dignity; and

personal autonomy.

Those who expressed opposition to assisted dying were most concerned about:

the risk of coercion of vulnerable people;

the sanctity of life; and

devaluing the lives of certain groups.

These themes featured heavily in the written and oral evidence and are explored in more detail in the following sections.

Suffering

In evidence submitted to the Committee, the relief of suffering was one of the key considerations of those in support of the Bill. However, it also featured heavily in the detailed responses of people opposed.

For some, palliative care was seen as the natural way to ease suffering. However, others believed palliative care could not relieve the suffering of everyone and was limited in how it can address forms of suffering beyond physical pain. This argument was often supported in written evidence by personal accounts of having watched a loved one die.

Some also argued that, in and of itself, having the option of an assisted death has a therapeutic value in helping to alleviate suffering by giving greater choice and control at end of life, pointing to an increasing proportion of people in places like Oregon, who are approved for an assisted death but ultimately do not make use of the option.

However, some opposed to the Bill did not accept the suggestion that some suffering cannot be alleviated and emphasised the importance of palliative care. Dr Gillian Wright from Our Duty of Care argued:

We can always do something. We have heard many distressing stories, and we absolutely need to respond to them, but there is much more that we could be doing as a community.

...I am aware that there are many failures of care but it is not a case of asking people to thole it, as you might be implying. There is so much that we can do that is not being done.1

The issue of palliative care is discussed in more detail later in this report.

Dignity

A substantial proportion of those supporting the Bill argued that many people at the end of their lives experience a loss of dignity and a level of dependence that is unacceptable to them. These submissions generally argued that it is inhumane to force a person to suffer when their wish is to die. Many drew upon personal experiences of having witnessed a loved one die.

Those opposed to the Bill also spoke of dignity, insisting that this does not diminish because a person is ill or requires assistance from others. These responses argued that a person's sense of dignity is shaped by societal attitudes and norms and that assisted dying would fundamentally change these norms in a way that would reinforce any perceived loss of dignity.

Autonomy

The ‘right to autonomy’ was cited in arguments from both those supporting and opposing the Bill.

Supporters of the Bill argued that individuals have the right to determine the value and quality of their own lives and to make end-of-life decisions based on that judgement. These arguments were often cited alongside the importance of 'choice' and a belief that individuals should have the right to choose the timing and manner of their death. This was reiterated in oral evidence. For example, Alyson Thomson from Dignity in Dying Scotland told the Committee:

The bill does not give people a choice between living or dying; that choice has already been taken away. The bill gives a choice between two kinds of death.1

In contrast, opponents of the Bill argued that autonomy is not absolute and that, in certain circumstances, it is the role of legislation to restrict individual autonomy for the wider benefit of society. Some respondents argued that respecting individual autonomy ignores the interconnected nature of society and the impact such a decision can have on others. In its written submission, the Scottish Council on Human Bioethics argued that, in supporting individual autonomy, the Bill should be carefully assessed for any unintended consequences it may have for society as a whole:

...in an interactive society, making a choice about the value of a life (even one’s own) means making a decision about the value of other lives.2

Devaluing the lives of certain groups

Some of those opposed to the Bill also took the view that legalising assisted dying would send a message that certain individuals’ lives are less valuable than others and that these individuals are considered to be a burden on society. This was considered by these contributors to be a particular risk for people with disabilities and for older people.

In oral evidence, representatives of disability organisations described their fears that the scope of the Bill would quickly be expanded to include those with disabilities within the eligibility criteria for assisted dying. On the back of this, these witnesses expressed concerns that assisted dying would then be presented to them as a viable alternative to support for living. Tressa Burke from Glasgow Disability Alliance told the Committee:

...we take a very clear stand against assisted dying. We simply believe that it will creep and that disabled people will be at the thin end of the wedge.1

Arguments around the potential expansion of eligibility criteria are addressed in more detail in the 'Slippery slope' section.

At the same time, some questioned the extent to which opposition to assisted dying was as widely shared amongst disabled people as was implied by the representatives of disability organisations who gave oral evidence to the Committee. Alyson Thomson from Dignity in Dying Scotland told the Committee:

We know, from our own polling, that the majority of disabled people support a terminal illness assisted dying law. We speak to many people who are disabled and take a different view. I have a letter from a group of prominent disabled activists, which I believe has been circulated to Parliament. In the letter, they say: “We do not wish disabled people to be cited as a homogenous group in efforts to deny dying people choice.”

In a similar vein, some contributors questioned how comfortably the legalisation of assisted dying could sit alongside an effective suicide prevention strategy and work undertaken in Scotland to date to reduce levels of unassisted suicide. These contributors felt that the Bill was at odds with this work and that legalising assisted dying would effectively mean that the state was sanctioning the idea that some lives are not worth living.

In response to these criticisms, Liam McArthur stressed that, under the terms of the Bill, only those with a terminal illness would be deemed eligible for assisted dying. He further highlighted a statement made by a number of Australian organisations which outlined what they considered to be the critical difference between suicide and assisted dying:

Suicide is when a person tragically and intentionally ends their own life...

Voluntary assisted dying is not a choice between life and death. It is an end-of-life choice available to eligible terminally ill people who are already dying. It offers an element of control and comfort over how they die when death becomes inevitable and imminent...

Both suicide prevention and voluntary assisted dying are as important as they are distinct. Confusing these terms can delay access to suicide prevention services for people in distress, and complicate care for those who are at end of life.2

Risk of coercion

Many respondents to the calls for views argued that no law could ever truly safeguard against coercion and the only effective way to protect people from coercion was not to legalise assisted dying in the first place.1

This issue was also explored in more detail during oral evidence. Julian Gardner from the Voluntary Assisted Dying Review Board in Victoria, Australia, told the Committee that, while he had seen no evidence of people being coerced into assisted dying in that jurisdiction, he had seen evidence of the opposite.2

The only reports that we have had have been the reverse, in that people have experienced coercion—that might be too strong a word—or undue influence not to go ahead with ending their life, generally from relatives who have objections or from faith-based institutions.2

However, during an evidence session with witnesses in Canada, Dr Ramona Coelho gave an opposing view on the potential risk of coercion, arguing that, in her view, coercion to undergo medical assistance in dying in Canada would manifest itself in more subtle ways:

If you look at the Health Canada reports, you will see that fear of being a burden and loneliness are high up among the top five reasons for people choosing MAID. [Medical assistance in dying]4

This same concern was also raised in written evidence and characterised by some respondents as constituting a form of ‘internalised’ coercion.1 This issue is addressed in more detail later in this report (see Coercion).

'Slippery slope'

Many submissions from those opposed to assisted dying contended that the passing of the Bill would be the start of a 'slippery slope'. This contention was underpinned by two principal arguments:

That the law tends to expand eligibility or reduce safeguards over time.

That the number of people having an assisted death inevitably rises over time.

Expanding eligibility criteria / reduced safeguards

Those arguing there would be a high likelihood of eligibility criteria expanding over time tended to make reference to experience in Canada, the Netherlands and Belgium, where it was claimed that eligibility criteria had been widened and safeguards had been progressively relaxed or removed since the legislation in those jurisdictions entered into force.

Conversely, those who supported the Bill tended to highlight other jurisdictions where they claimed eligibility criteria and safeguards had not changed since assisted dying legislation entered into force. For these contributors, Oregon was the most commonly cited example, where contributors argued that the legislation had remained largely unchanged since its introduction in 1997.

The Committee also heard evidence, including from legal and human rights stakeholders, that expansion of eligibility criteria under assisted dying laws was more likely to have taken place in jurisdictions that had amended their constitutions or criminal codes to give effect to legalised assisted dying as a result of court rulings, as opposed to jurisdictions which had passed statute to legalise assisted dying, in the absence of such constitutional pressure. By contrast, it was contended that, due to the constitutional set-up in this country, any such changes in Scotland would have to take place through updated legislation that was subject to Parliamentary scrutiny, meaning that such changes could not be achieved through constitutional challenge and were therefore not inevitable (See The risks of a legal challenge extending the eligibility criteria in the Bill).

Liam McArthur argued:

The Canadian model, which is often cited, has evolved through court process, which is sometimes brought into the debate here as something of a risk, but the constitutional arrangements in Canada are very different from those in Scotland and in the UK. The legislation was introduced as a result of a case that was brought before the supreme court in Canada on the basis that the ban on assisted dying was unconstitutional. The Parliament then introduced legislation, which was not felt to go far enough, so it was then legally challenged on appeal, which was upheld, and the scope of the legislation was expanded.1

However, Dr Mary Neal from the University of Strathclyde argued that the Bill contained many areas that were subject to potential ‘slippage’ and that, irrespective of how tightly the law was felt to have been drafted, there was ultimately no way of preventing people from challenging it.2

Liam McArthur contended that, in jurisdictions where eligibility is based on terminal illness and mental capacity, there was no evidence of those criteria having been subsequently expanded. He also highlighted this as one of the key findings of the House of Commons Health and Social Care Committee inquiry into assisted dying.3

Increasing numbers over time

Evidence submitted to the Committee suggested that, in jurisdictions that had legalised assisted dying, there was a general tendency for the number of assisted deaths as a proportion of overall deaths to increase over time. However, many argued that this tendency was an inevitable result of increased awareness of assisted dying as an option following legalisation, while some contended that such an increase should not necessarily be considered a bad thing. Dr Stefanie Green from the Canadian Association of MAiD Assessors and Providers told the Committee:

I am also compelled to point out that actual numbers are irrelevant, of course, because there is a value judgment being added here. Let us say that we believe that heart attacks are bad. If the rate of heart attacks is increasing, we should be worried about that and try to do something to bring it down, but that is because we have made a somewhat non-controversial value judgment that heart attacks are bad. If you think that assisted dying is bad, there is no good number.4

Fraser Sutherland from the Humanist Society Scotland was in agreement with Dr Green's assessment and concluded:

There is an idea that more people accessing the right to assisted dying is evidence of a slippery slope but, if the eligibility criteria have stayed the same, it is only an issue if you inherently have a moral and ethical problem with the principle in the first place.5

The Committee acknowledges all of the evidence it has received during its scrutiny of this Bill at Stage 1 and the strongly held convictions and good intentions of contributors from all sides of the debate on assisted dying. At the same time, the Committee considers that many of the arguments on the fundamental question of whether assisted dying should or should not be legalised are philosophical in nature. It will be a matter for individual members, in deciding how they wish to vote on the general principles of the Bill, to take these into account and to determine what prioritisation and weight they wish to give them.

On the debate around the potential risks of a 'slippery slope' towards a broadening of eligibility criteria and a relaxation or removal of safeguards over time, the Committee notes the very different ways in which legalisation of assisted dying has come about in different jurisdictions around the world. Should the Bill progress to Stage 2, the Committee believes there could be merit in exploring what suitable mechanisms, if any, might be necessary or desirable to address these potential risks in the specific legal and constitutional context in which the Bill would become law.

The Committee notes evidence from other jurisdictions that there has been a general tendency towards the number of people requesting assisted dying increasing over time following legalisation. Some have argued that such trends are a cause for concern while others take the view that such a trend should not, in and of itself, be considered concerning. Should the Bill progress to become law, the Committee considers it important for such trends to be monitored in conjunction with other factors including the availability of palliative care and social care.

Palliative care

The Committee received substantial evidence on the importance of palliative care as part of the debate on assisted dying. For those in favour of assisted dying, there was a belief that, for some people, no amount of palliative care would alleviate suffering. These contributors tended to view palliative care as complementary to assisted dying.1

Conversely, those opposed to assisted dying expressed concerns on two fronts:

That inadequate palliative care will act as a driver of requests for assisted dying; and

That assisted dying will erode the quality and availability of palliative care.

Palliative care as a driver of assisted dying

The Committee heard concerns that current inadequacies in palliative care provision may lead people to consider assisted dying to be their best or only option. The Committee heard evidence of current shortcomings in services which some contributors argued needed to be addressed before the prospect of legalising assisted dying should be considered.

Contributors on both sides of the debate called for greater resourcing of palliative care and shortcomings in availability of palliative care were highlighted repeatedly in evidence. For example, in her written submission, Rachel Kemp told the Committee: “… there are more MSPs than palliative care consultants in Scotland.”2

Sarah Mills from the University of St Andrews told the Committee that palliative care services have become increasingly stretched since the COVID-19 pandemic and suggested they were unable to keep up with demand:

When everything works—when the planets align and we can provide the services to the patients—palliative care is excellent, but the services are not adequate to meet the need.3

Others argued that, irrespective of whether or not the current Bill were to become law, providing good quality palliative care to all who need it would remain a key challenge. In this context, they suggested that assisted dying and palliative care should not be viewed as being in opposition to one another. Rami Okasha from Children's Hospices Across Scotland said:

There are important questions about access, equity of funding, and ensuring that the appropriate palliative care services are there. Even if this bill were not to proceed and parliamentarians were not to support it, the need for palliative care would remain; and, even if parliamentarians do support it and it becomes law, there would be many people who may wish to access assisted dying, but for whom palliative care would be necessary and would provide significant relief and support for many, many years prior to death.3

Some witnesses who were supportive of the Bill also highlighted evidence that, in jurisdictions where assisted dying had been legalised, a high proportion of those seeking an assisted death were already in receipt of palliative care and that the number of people engaging with palliative care services had increased since assisted dying was legalised.

In his evidence to the Committee, Liam McArthur emphasised his expectation that all care and treatment options, including palliative care, would be discussed with individuals requesting access to assisted dying, to enable them to make a properly informed decision:

One of the safeguards that is built into the process is the discussion that needs to take place between the co-ordinating physician and the patient to ensure that the patient is aware of all the options that are available—palliative care, social care or other types of health and care treatments—so that the decision is informed.5

Effect of assisted dying on palliative care

Some palliative care and hospice professionals who responded to the call for views expressed concerns that the Bill could undermine their work and divert resources from the services they provide.1 These concerns were also explored when the Committee took evidence from witnesses on experiences of assisted dying in Canada.

During this session, Dr Ramona Coelho told the Committee:

...in the words of the [Canadian Society of Palliative Medicine], we are seeing “the diversion of limited palliative care resources to support [medical assistance in dying], and the potential for patients refusing palliative care services for fear it will hasten their death.”7

This viewpoint was disputed by Dr Stefanie Green from the Canadian Association of MAiD Assessors and Providers who pointed to an increase in funding for palliative care services that had been provided by the Canadian Government since assisted dying was legalised:

One simply cannot say that resources have been diverted from palliative care to MAID. In fact, as in every other legal jurisdiction in the world where we see assisted dying provision, the funding and levels of palliative care have increased since that became legal.7

Alyson Thomson from Dignity in Dying Scotland echoed this view and pointed to similar evidence from a number of jurisdictions while also highlighting the additional benefits legalisation of assisted dying could have in improving end-of-life care practices more broadly:

I mentioned the Westminster Health and Social Care Committee inquiry. Another of its findings was that, in jurisdictions that have legalised assisted dying, end-of-life and palliative care can improve. The inquiry can point to a number of jurisdictions where massive investments in palliative care were made at the same time as assisted dying was introduced. A whole host of other end-of-life practices improve as well, as conversations about death and dying and the culture around those things open up, as people have more open and transparent conversations and as more doctors are trained in supporting people at end of life.9

Throughout its scrutiny of the Bill at Stage 1, the Committee has heard compelling evidence of the overarching importance, irrespective of whether or not the Bill becomes law, of ensuring that everyone who needs to is able to access good quality palliative care at the end of their lives. The Committee hopes that, regardless of the outcome, the current debate on assisted dying will provide a catalyst for further attention to be given towards improving the quality and availability of palliative care services in Scotland.

Should the Bill progress beyond Stage 1, the Committee highlights to the Scottish Government the importance of giving ongoing careful consideration to how the Bill, if it becomes law, will interact with all other key aspects of end-of-life care provision, including palliative care.

Legal and human rights considerations

Assisted dying and human rights - legal context

Both the courts in the UK and the European Court of Human Rights have recognised that the right to decide when and how to die is an aspect of the right to respect for private and family life under Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). However, states have wide discretion in relation to how they set the law in this area. This is sometimes referred to as a wide “margin of appreciation”.

There is also a recognised need to ensure protection for vulnerable groups. No country has yet been found in breach of the ECHR on the basis of not providing access to assisted dying.

The law relating to accessing assisted dying has been challenged on human rights grounds on several occasions in England and Wales. In a recent challenge – of R (Nicklinson and another) v Ministry of Justice ([2014] UKSC 38) – a majority of judges declined to declare the law in England and Wales incompatible with Article 8 of the ECHR. Out of a panel of nine justices, two would have made a declaration of incompatibility; three thought the UK Parliament should be given the opportunity to change the law first; and a further four thought that the issue was for Parliament rather than the courts to decide.

Several respondents to the Committee’s call for views addressed the human rights implications of assisted dying. They noted that legislating for assisted dying engages several of the rights set out in the ECHR:

Article 2 – the right to life – the courts have held that the right to life does not include a right to access an assisted death. However, it does include a duty on the state to adequately investigate deaths to ensure the state’s obligations under Article 2 are being met. Where a state has introduced assisted dying, it would also include a requirement for safeguards for vulnerable people.

Article 8 – the right to respect for private life – court decisions have found that this does include a right to choose when and how to die. However, states have wide discretion in the control of this right for the protection of others.

Article 14 – prohibition of discrimination – there must be no discrimination on any grounds in relation to exercising the rights protected by the ECHR.

Eleanor Deeming from the Scottish Human Rights Commission described the human rights context for the Bill as follows:

If legislation is adopted, the key point is that, to be compliant from a human rights perspective, the legislation must have in place appropriate and sufficient safeguards, particularly to ensure free and informed consent of anyone accessing assisted dying. It is especially important to consider the rights of particular groups of people, such as disabled people, in the debate on whether to adopt legislation.1

The risks of a legal challenge extending the eligibility criteria in the Bill

A key concern for many people and bodies who oppose the Bill is that the eligibility criteria for assisted dying will be expanded over time and potentially without parliamentary scrutiny. This 'slippery slope' argument is discussed in more detail in the section above on Views for and against assisted dying.

Under the terms of the Scotland Act 1998, provisions in Acts of the Scottish Parliament can be struck down on the basis that they are outwith the legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament. One of the grounds for doing so is that a provision is not compliant with the rights set out in the ECHR.

Dr Mary Neal from the University of Strathclyde specifically addressed the potential for the Bill to be subject to human rights challenges in her oral evidence to the Committee. She discussed two lines of argument raised in the context of the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill being considered by the UK Parliament:

Under article 14... the argument is that, once assisted dying is allowed within a jurisdiction, questions begin to arise about discrimination and about whether the rules for eligibility will discriminate against some groups who are not eligible. Once you start to allow it for some people, the question that arises is whether human rights require that you allow it for others, too.1

In reference to Article 2 of the ECHR, Dr Neal added:

Under article 2, an argument is being aired to the effect that, although the article does not preclude assisted dying, it might preclude a state providing assisted dying. Obviously, that is as much of an issue in Scotland as it is in England and Wales, because the national health service would be involved in both cases.1

However, other witnesses were less concerned about the potential for the Bill to be subject to human rights challenges. Eleanor Deeming from the Scottish Human Rights Commission argued that decisions of the European Court of Human Rights give states wide discretion in dealing with such cases:

As recently as last year, in the case of Karsai against Hungary, you again see the court at Strasbourg level [the European Court of Human Rights] re-emphasising that this is an area where states are afforded a wide margin of appreciation. That is not to say that it would never intervene under article 2 were it needed to ensure that stringent safeguards were in place to support the right to life, but it was clear that, from the perspective of article 8, the margin extends not just to the decision to intervene or legislate in this area, but, once an intervention has been made, to the detailed rules that are laid down to achieve a balance between different interests.1

Lynda Towers from the Law Society of Scotland agreed with this assessment and added:

…it is worth remembering that the Supreme Court in this country has also indicated that it is pretty unwilling to become involved in cases that are perhaps more to do with social rather than regulatory aspects.1

However, Dr Gordon Macdonald from Care Not Killing challenged the view that the UK courts would continue to take a relaxed attitude in this area:

The fact that, up until now, the courts have said that this is a matter for the Parliament does not mean that they will make the same judgment in future. Once the Parliament has accepted the principle, the question before the courts would not be whether it should be legalised, but whether the law is being implemented fairly and whether there are any discrimination issues.5

The Committee acknowledges that, should it become law, there may be a risk of the Bill being subject to human rights or other court challenges and that this could result in eligibility for assisted dying being extended over time. The Committee further recognises that one's view of the likelihood and seriousness of this risk is likely to vary according to one's overall view of the Bill. The Committee notes that this will be one of a range of factors for individual members to consider in deciding how they wish to vote on the general principles of the Bill.

Views on whether the Bill sufficiently protects vulnerable groups

The Committee received evidence from groups representing people with long-term health conditions as well as from groups representing disabled people. Witnesses from these groups were asked whether, in their view, the Bill provides sufficient protections for vulnerable groups, as required under Article 2 of the ECHR.

Some witnesses expressed a view that the issue was nuanced, reflecting a difficult balance between supporting autonomy and protecting potentially vulnerable people. Vicki Cahill from Alzheimer Scotland said:

The decision to either include people with dementia or exclude them from accessing the bill’s provisions will have significant implications for their human rights, regardless of which way we go and the direction of travel on that. For example, excluding people with dementia from accessing provisions for an assisted death could be seen as an erosion of their rights. However, there also has to be a balance between protecting those human rights and the need for protection and safeguarding, because people with dementia are a particularly vulnerable group and we need to ensure that no harm is done.1

However, those witnesses representing disabled people’s organisations who gave oral evidence to the Committee were strongly of the view that the provisions in the Bill as introduced represented a direct threat to disabled people’s rights. A key concern for these witnesses was the context in which a disabled person might reach a decision to request assisted dying, in light of the structural inequalities disabled people currently face.

Lyn Pornaro from Disability Equality Scotland described the nature of these structural inequalities:

Some disabled people have a fight on their hands from the moment that they are born. They have to fight to get the support that they need, to be heard, to be listened to, to be valued and, sometimes, to be educated. They have to fight to live life and have opportunities in the same way as non-disabled people do—they have to fight for fairness. They are neglected, and they have their human rights taken away from them.1

Marianne Scobie from Glasgow Centre for Inclusive Living went on to describe the impact disabled people experienced as a result of having their lives devalued by society:

Our lives as disabled people are portrayed as tragic and worthless all the time on television, in literature and in the media, and many people start to internalise those feelings and think that they would be better off dead if they cannot walk, talk, feed themselves or go to the toilet.1

Giving evidence to the Committee, Dr Miro Griffiths from Not Dead Yet UK set out how the Bill, in his view, was incompatible with Article 2 of the ECHR and failed to provide the appropriate protections for vulnerable people required by that article in the context of legalising assisted dying:

My view, as someone who is most interested in the implications that the bill has for disabled people’s communities, is that the state has a role and a responsibility to protect disabled people, particularly because of the systemic inequalities that are faced by disabled people’s communities across the country. The state therefore has a role in protecting all life associated with disabled people’s communities. I think that what you are proposing is incompatible not only with disability rights, but with the principle that the state is there to protect disabled people.4

However, this view was challenged by supporters of the Bill. Alyson Thomson from Dignity in Dying Scotland recognised the structural inequalities disabled people face and the urgent need for these to be addressed but argued that this was a separate debate to the one concerning assisted dying:

I can completely understand why we need to make urgent progress on all those fronts, but we do not do that by banning choice for dying people. All that that does is exacerbate the suffering for a group of people who are dying. The bill does not give people a choice between living or dying; that choice has already been taken away. The bill gives a choice between two kinds of death.4

Meanwhile, while similarly recognising the structural inequalities disabled people face and the urgent need for these to be tackled, Liam McArthur told the Committee that anyone who feared that disabled people might be forced into a situation of requesting assisted dying should be reassured that, according to the eligibility criteria set out in the Bill, “...having a disability alone does not make you eligible to access an assisted death—you need an advanced, progressive, terminal illness and mental capacity to be able to do so."6

The Committee notes the compelling evidence it has heard concerning the significant structural inequalities and barriers to services and support disabled people face every day. It recognises that these and the negative societal attitudes that lead disabled people to feel their lives are devalued need to be urgently and systematically addressed.

The Committee notes the concerns raised by organisations representing disabled people and by others about what they perceive to be the risks to vulnerable groups posed by the Bill. It also notes the views expressed by those who support the Bill in arguing that it provides appropriate protections for vulnerable groups, in accordance with the requirements of Article 2 of the ECHR. The question of whether the Bill strikes an appropriate balance between providing a right for terminally ill adults to access assisted dying and the requirement to protect vulnerable groups will be a matter for further consideration by individual members in deciding how they wish to vote on the general principles of the Bill.

Views on oversight of decisions to protect human rights

During the Committee's Stage 1 scrutiny, stakeholders argued that aspects of the Bill could be improved to strengthen human rights compliance. One suggestion in this regard was that the Bill should include stronger oversight mechanisms in relation to decisions to access assisted dying.

In its response to the Committee’s call for views, Edinburgh Napier University Centre for Mental Health Practice, Policy and Law Research raised concerns that the oversight mechanisms included in the Bill as introduced were weak. To strengthen the Bill, it proposed the development of local multi-disciplinary panels to monitor practice and review individual cases.1

The Law Society of Scotland also highlighted stronger oversight mechanisms as a potential means of strengthening human rights compliance within the Bill:

Given the need for robust legal and institutional safeguards to ensure compliance with Article 2 ECHR..., we note that the Bill doesn’t appear to provide oversight provisions beyond collection and reporting of data. We understand that some countries have review boards and review committees to provide oversight, especially when the death certificate will only record the terminal illness and won’t disclose an assisted death. It may be appropriate for consideration to be given to strengthening oversight measures.2

In oral evidence to the Committee, Eleanor Deeming from the Scottish Human Rights Commission emphasised the importance of introducing review options both at the beginning and the end of the assisted dying process outlined in the Bill. She argued that pre-event reviews, carried out in an independent or judicial capacity, could be seen as “...a robust means of reducing concerns about inappropriate use".3 She went on to explain:

Article 2 requires that there is sufficient subsequent review to ensure that there is effective, independent and prompt investigation of deaths. That is why we have recommended that the Parliament considers including a system of judicial or independent oversight, with both prior and subsequent reviews, to comply with human rights standards. That would provide a much higher degree of scrutiny and stronger safeguards around the right to life.3

Other respondents to the call for views raised what is sometimes referred to as a 'civic model' for assisted dying. Under this model, decision-making in relation to assisted dying would sit with the courts rather than with health professionals (although health professionals would still have a role in carrying out assessments). The Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill currently before the UK Parliament would, as originally drafted, require every application for assisted dying to be considered by the High Court for England and Wales.

During his evidence to the Committee, Liam McArthur was asked whether he had considered a role for court oversight in the assisted dying process. He responded:

I did, because I was aware that it had been an aspect of earlier bills that had come before the Westminster Parliament. However, I was not necessarily convinced that I could see what additional safeguard it would put in place. The balance is always to ensure that the safeguards do what they are intended to do, and do not simply act as an unnecessary obstacle while not providing any protection.5

However, Liam McArthur went on to highlight the role of the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service’s (COPFS) Scottish Fatalities Investigation Unit in investigating all deaths in Scotland which are sudden, suspicious or unexplained. He concluded:

That may offer the sort of reassurance that the public might have expected court oversight to provide.6

The Committee took evidence from representatives of COPFS during its meeting on 28 January 2025. Andy Shanks, Head of the Scottish Fatalities Investigation Unit, outlined the role the Unit would ordinarily fulfil with respect to the investigation of fatalities:

Deaths are already investigated independently by the COPFS on behalf of the Lord Advocate, which would bring that degree of independent scrutiny to the circumstances of the death. That is not only done in relation to the potential for criminality but, beyond that, in terms of wider death investigation purposes, it is done to see whether there are systemic issues or issues of public concern that require further investigation— or, indeed, whether it is in the public interest to hold a fatal accident inquiry. Therefore, I think that independent scrutiny would already exist.7

The representatives of COPFS who gave evidence to the Committee confirmed that medical practitioners are already provided with guidance on those deaths that are required to be reported to the COPFS. Andy Shanks concluded:

Ultimately, it is a matter for the Lord Advocate whether that guidance would be changed: I cannot commit to a position on her behalf today. However, were the provisions to come into force, it is likely that deaths using the assisted dying process would require to be reported to the procurator fiscal as a mandatory category of reportable death.7

At the same time, witnesses representing COPFS indicated that, in the event of the Bill becoming law, they would normally expect their involvement in investigating cases of assisted dying to be relatively short and unlikely to uncover any concerns. Andy Shanks went on to argue that, even in circumstances where a process was considered not to have been lawful, this may not automatically mean that a criminal offence had been committed.7

The Committee notes evidence from those contributors to its scrutiny of the Bill who have argued that the safeguards in the Bill, and its compliance with human rights requirements, could be strengthened by the introduction of an independent oversight mechanism. It also notes evidence from COPFS regarding the role it would expect to play in investigating cases of assisted dying if the Bill were to become law. Should the Bill progress beyond Stage 1, the Committee would welcome the opportunity to consider amendments to provide for independent oversight within the Bill at Stage 2. Options include the creation of an independent review panel at a local or national level or a potential role for the Chief Medical Officer in monitoring the Bill's implementation, as has been provided for in the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill, currently under consideration in the UK Parliament.

Views on options for challenging decisions made by doctors

During the Committee's Stage 1 scrutiny, several stakeholders have noted that the Bill as introduced provides no mechanisms for the decisions made by doctors as part of the process outlined in the Bill to be challenged, be that in a court or via another independent forum. According to the Bill as introduced, doctors would be responsible for assessing:

whether someone met the requirements of having a terminal illness as defined in the Bill;

whether someone had capacity to make a decision to access assisted dying at each stage of the process; and

whether someone had been coerced into reaching a decision to access assisted dying.

In its written response to the Committee, Edinburgh Napier University Centre for Mental Health Practice, Policy and Law Research raised the following concerns:

We are concerned at the lack of any accessible mechanism by which the decision of a doctor can be appealed or independently reviewed by the courts. This may raise concerns about compliance with Article 6 of the ECHR and, even if this is not the case, we believe it is a significant gap.1

It went on to draw comparisons with provisions in the Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000 which allow “anyone with an interest” to challenge a decision by a doctor in relation to the treatment of an adult with incapacity. However, it also argued that additional safeguards would be necessary if such a process were to be established, to prevent abuse by campaign groups.

The Equality and Human Rights Commission raised similar concerns in its written submission:

The Bill and accompanying documents are unclear on a process for requesting redeterminations in the situation a registered medical practitioner does not agree that the conditions in relation to provision of assistance have been met, or where different medical practitioners do not agree that they’ve been met.2

Liam McArthur discussed his expectations of what would happen in the event that an individual wished to challenge the view of a doctor who had concluded that they did not qualify for assisted dying:

If the patient does not meet those criteria to the satisfaction of both medics, the option to go to another medical practitioner remains open to them...3

However, in terms of introducing a more formal mechanism for reviewing or challenging decisions, Mr McArthur went on to say:

There is the option for an individual to seek a diagnosis, but medical professionals will make these assessments. If the patient does not meet the criteria, it is important for the patient, the medics and public confidence that the law, as it stands, remains extant.3

The Committee notes concerns from certain contributors to its scrutiny that the Bill lacks clear provision for the decisions of medical practitioners, as part of the assisted dying process, to be independently challenged or reviewed. Should the Bill progress beyond Stage 1, the Committee would welcome the opportunity to consider amendments to the Bill that would allow such decisions to be subject to an independent review or appeals process. The Committee notes from evidence that this need not be a formal process, such as via a court, but could equally be fulfilled by a more informal process, such as via an independent review panel, as referenced above. In this context, it further suggests that consideration would need to be given to who would be entitled to access any such review process to ensure it is protected against potential risks of being abused.

Eligibility and capacity

Section 1 of the Bill sets out that an "...eligible terminally ill adult may, on request, be lawfully provided with assistance to end their life" as long as that assistance is provided in accordance with its provisions.1 Section 2 provides a definition of terminal illness for the purposes of the Bill and Section 3 sets out additional eligibility criteria for access to assisted dying.

Definition of terminal illness

Section 2 defines terminal illness, for the purposes of the Bill, as follows:

a person is terminally ill if they have an advanced and progressive disease, illness or condition from which they are unable to recover and that can reasonably be expected to cause their premature death.1

The definition in the Bill follows that set out in the Social Security (Scotland) Act 2018, which was intended to widen access to disability benefits for those living with terminal illnesses. The definition in the 2018 Act does not include a prognostic timescale, as it was determined that for many terminal illnesses, particularly non-cancer conditions like motor neurone disease (MND), chronic heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), accurate prognosis can be difficult because of the unpredictable trajectories of these conditions. This definition moved away from prognostic timescales to allow registered medical practitioners and registered nurses to use their clinical judgement to determine if an individual meets this eligibility criterion, using guidance issued by the Chief Medical Officer.

As a comparison, the definition used by the UK Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) for determining eligibility for disability benefits under terminal illness rules contains a 12 month prognostic timescalei and the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill introduced in the House of Commons in November 2024 determines eligibility for access to assisted dying on the basis of a 6 month prognostic timescale.

The Policy Memorandum accompanying the current Bill notes that the definition of terminal illness does not include reference to a period of life expectancy. However, it states that "...the definition requires a person to be in an advanced stage of terminal illness (i.e. close to death)."2

Many respondents to the Committee's calls for evidence on the Bill raised concerns about the breadth of the definition of terminal illness on the basis that there would be potential for the definition to include a wide range of long-term conditions. Some proposed the inclusion of a prognostic timescale, such as 6 or 12 months, as a means of narrowing the definition. Conversely, others have raised concerns that the definition is already too narrow and discriminates against people experiencing other conditions that, although they may not meet the definition of terminal illness, nonetheless bring "unbearable suffering".

When taking evidence from representatives of organisations that provide palliative care and support at the end of life in Scotland, the Committee heard concerns that the definition and language proposed in the Bill could lead to inconsistency of application. Mark Hazelwood from the Scottish Partnership for Palliative Care told the Committee:

...the key terms "advanced and progressive" disease and "premature" mortality are not precise and do not have agreed definitions, so the definition in the bill does not deliver the clearly defined and quite narrow cohort that seems to be the policy intent as set out in the policy memorandum. That will result in variation in interpretation, with the public and practitioners being confused about who might be eligible, and there will be inconsistency.3

During a separate evidence session, Vicki Cahill from Alzheimer Scotland also argued that the terminology used in the definition of terminal illness should be more descriptive, as the current lack of specificity could be problematic:

It is not specific enough or clear enough to make sure that we are not missing out those individuals who either might be able to or who should not be able to access those provisions.4

Witnesses representing medical professions were not in a position to indicate a particular collective view of their members regarding the definition of terminal illness set out in the Bill. However, Dr Chris Provan from the Royal College of General Practitioners Scotland expressed his support for the definition contained in the Bill and for the decision of Liam McArthur not to include a prognostic timescale within that definition:

The definition is not one of the areas that we have significant concerns about, because it appears to cover much of what is relevant and is relatively narrow, without giving a timescale.3