Health and Sport Committee

Stage 1 Report on the Human Tissue (Authorisation) (Scotland) Bill

Introduction

Membership changes

There has been one occasion where the membership of the Committee changed in the reporting period.

George Adam MSP replaced Keith Brown MSP on 18 December 2018.

Overview of scrutiny

As part of the Scottish Government’s Programme for Government 2017- 2018, the First Minister, Nicola Sturgeon stated, “The Organ and Tissue Donation Bill will establish – with appropriate safeguards – a 'soft' opt-out system for the authorisation of organ and tissue donation, to allow even more lives to be saved by the precious gift of organ donation".

Subsequently, the Human Tissue (Authorisation) (Scotland) Bill was introduced by the Cabinet Secretary for Health and Sport, Shona Robison MSP on 8 June 2018. The Health and Sport Committee was designated as the lead Committee by the Parliamentary Bureau for the Stage 1 scrutiny of the Bill.

We issued a call for written views on the Bill on 28 June 2018. This call for views ran until 4 September and 35 submissions were received. We also carried out an online survey for members of the public on the main provisions of the Bill between 28 June 2018 to 4 September 2018. A total of 747 responses were received.

We heard formal evidence on the Bill over four committee meetings in November 2018. On 6 and 13 November, we took oral evidence from patient public groups, stakeholders representing front-line staff in the NHS and a witness attending in a personal capacity as a lung transplant recipient. On 20 November, we focussed on evidence from Wales. We heard from the lead researcher on the Evaluation of the Human Transplant (Wales) Act 2015 Report, the Chief Medical Officer from NHS Wales and the clinical lead for organ donation in Wales. This provided us with valuable insight into the opt-out system and its impact on transplantation rates in Wales. On 27 November, we focussed on the ethical and legal aspects of the Bill, taking evidence from the Law Society, the Mason Institute for Medicine, Life Sciences and the Law and the Scottish Council on Human Bioethics. In addition, the Minister for Public Health, Sport and Wellbeing, Joe FitzPatrick gave evidence to us on 27 November 2018.

In addition to the formal evidence sessions, we also held an informal meeting on 23 October 2018 with the regional manager for organ donation in Scotland and members of her team. This session provided an opportunity for us to observe the authorisation process for organ donation. We also held three informal meetings on 13 November 2018 with the following groups: people who have received donated organs, family members who have authorised the donation of organs and people currently on the organ transplant waiting list. A summary of the key themes and issues from the informal sessions at the Health and Sport Committee meeting on 13 November 2018.

We also received written evidence from the National Transplant Organization of Spain.

We would like to thank everyone who provided written and oral evidence as part of our consideration of the general principles of this Bill. We would particularly like to thank those who attended the three group meetings on 13 November 2018, providing insight into their personal experience of the organ donation process in Scotland.

A full list of witnesses and written submissions can be found in Annex B.

Background to the Bill

Donation and transplantation in Scotland is underpinned by the Human Tissue (Scotland) Act 2006 (the 2006 Act). This legislation sets out the legal basis for authorisation of donation for transplantation. The legislation states that organs and tissue can only be donated from someone if either the person themselves authorised donation before they died or if their nearest relative, or person with parental rights and responsibilities in the case of a child, authorises the donation on their behalf at the point of death. This is known as an opt-in system.

This Bill contains proposals to introduce a system of ‘deemed authorisation’ for organ and tissue donation for transplantation (often known as ‘presumed consent’). Deemed authorisation would apply when someone dies without making their decision on donation known, with their consent to donation being presumed unless their next of kin provided information to confirm this was against their wishes.

There have been previous attempts to legislate in this area. The most recent being a Members' Bill draft proposal from Mark Griffin MSP in December 2016. Mark Griffin MSP advised in February 2017 that he would purse a Members' Bill if the Scottish Government did not proceed with legislation on a soft opt-out system. Prior to this proposal, Ann McTaggart introduced a Members' Bill in 2015 entitled, The Transplantation (Authorisation and Removal of Organs etc) (Scotland) Bill. The Bill did not proceed past Stage 1. Following completion of the Stage 1 scrutiny, the Health and Sport Committee provided the following conclusion —

A majority of the Committee is not persuaded that the Bill is an effective means to increase organ donation rates in Scotland due to serious concerns over the practical implications of the Bill. A majority of Members consider that there is not enough clear evidence to demonstrate that specifically changing to an opt-out system of organ donation as proposed in the Bill, would, in itself result in an increase in donations. As a result, a majority of the committee cannot recommend the general principles of the Bill.

However, that Committee requested the Scottish Government consult on a 'workable' soft opt-out system for Scotland, alongside other measures to increase donation and transplantation. The Scottish Government duly consulted in December 2016. The consultation sought views about ways in which to increase the number of deceased organ and tissue donors; the number of referrals and the number of times donation is authorised.

The Scottish Government was keen to learn lessons from the evaluation of the Human Transplantation (Wales) (Act) 2013 which came into force in December 2015 and introduced an opt-out system for organ donation.

The Minister for Health, Sport and Wellbeing set out the need for this Bill at the committee meeting on 27 November. He highlighted that, whilst there has been an increase in donor number over the past 10 years, at any one time in Scotland there are over 500 people waiting for a transplant. He argued, “the international evidence is that, if we do this [legislate] correctly as part of a package of measures, it will lead to an increase in donations".

Purpose of the Bill

The Bill establishes three options in relation to donation. Members of the public would be able to opt-in, opt-out or do nothing. If a person dies without having registered their decision on the organ donor register, they will be deemed to have consented to having their organs donated. This is known as presumed consent or deemed authorisation. The last option would be a significant change to the current legislation and has been a source of debate throughout the scrutiny of the Bill.

The Human Tissue (Authorisation) (Scotland) Bill is structured as follows —

Part 1 provides an overview of the Bill structure;

Part 2 adds to the existing duties of Scottish Ministers under the 2006 Act to promote information and awareness about authorisation of transplantation and pre-death procedures; and to establish and maintain a register of information relating to decisions to authorise, or not authorise, donation;

Part 3 includes provisions which amend the 2006 Act in relation to authorisation of removal and use of part of a body by deceased persons, including providing for “deemed authorisation” of organ and tissue donation for adults for the purposes of transplantation of common types of organ and tissue; specific provisions regarding authorisation by or on behalf of a child; a framework for authorisation for pre-death procedures in order to allow successful transplantation; and setting out duties to inquire into the views of the potential donor; and

Part 4 sets out various general and final provisions, including adding an interpretation section, and makes consequential amendments.

The overarching aim of the Bill is to increase the organ and tissue donation rate and as a consequence, the number of transplants carried out. The Policy Memorandum highlights the way in which attitudes to the opt-out system have changed throughout the UK over the past two decades:

“Before 2000 a majority of people in the UK did not support an opt-out system of organ donation, but since then support has increased to an average of 60%."

A Scottish survey run in 2016, found 58% agreed “everyone should be presumed to be willing to be a donor unless they register a wish otherwise."

Furthermore, “when the Welsh Government consulted on moving to an opt-out system in 2012, there was 52% support for such a move, with 39% against. This compares to the public consultation in Scotland in 2017 where 82% of respondents were in favour of an opt-out system, with 18% against."

In line with the 2006 Act, this Bill aims to provide a framework where the views of the potential donor will take precedence. This will mean that in all circumstances it should be the views of the potential donor, where they are known, which determine whether donation goes ahead.

The Bill also aims to introduce more flexibility in the timing of the authorisation process, in addition to more clarity on authorisation for ‘pre-death procedures’, which may be carried out to increase the likelihood of a successful transplant.

The Scottish Government argues that, “moving to a soft opt-out system of donation will add to the package of measures already in place to increase donation and will be part of the on-going long-term culture change to encourage people to support donation".

Overall views on the Bill

Opinion polls tend to indicate public support for presumed consent with safeguards in place. We issued a call for written evidence in addition to a survey on the Bill’s proposals. Our survey found 68.8% of respondents agreed with a move to deemed authorisation, 29.2 % disagreed and 2% were neutral.

Respondents to the survey reported that they found the current message on deemed authorisation is confusing. This was also reiterated by Gillian Hollis, a lung transplant recipient and witness to the Committee. Ms Hollis advised —

Tell us if you want to donate, tell us if you don’t want to donate, and if you don’t tell us anything, we’ll presume you have authorised donation.

'Deemed authorisation' is not an intuitive description, and the use of the phrases opt-in and opt-out invites double negatives.

The main objection from survey respondents opposed to the Bill, related to the rights of the individual and the role of the state with regards to deemed authorisation. In written evidence, Christian Action Research and Education for Scotland, (CARE) summarised this concern —

Our primary ethical concern is that the proposal disrespects the personhood of people by considering their bodies to be commodities which the state can acquire without prior consent having been obtained from the individual involved.

Another key point raised in the written and oral evidence was the notion of donation being a special gift from one person to another. Some respondents and witnesses argued that deemed authorisation would undermine this relationship.

In addition, 22.5% of survey respondents were strongly opposed to deemed authorisation and indicated they would opt-out of donation if the Bill became law.

Recurring themes from respondents included —

Whether deemed authorisation would increase the number of donations;

The role of the family and whether their wishes would also be taken into account when deemed authorisation applies;

Whether deemed authorisation would have a negative effect on the number of people choosing to opt-out of organ donation if the Bill is passed;

Whether there would be adequate opportunities for people to opt-out if they wish;

Confusion over the options available under the Bill, including the retention of the opportunity to opt-in;

Confusion over the term ‘pre-death procedures’, what this would entail and when it would take place.

Increase in donation rates?

The Policy Memorandum outlines the case for deemed authorisation, noting that,“despite the real benefits of transplantation, there is still a shortage of organs, and over 500 people in Scotland are waiting for a transplant at any one point”. The Scottish Government is therefore keen to “maximise the number of donors, particularly as only around 1% of people die in circumstances where they can become a deceased donor".

Currently, organs and tissue for transplantation can be made available in the following ways —

1. Through deceased donation (donation after death), specifically by two methods;

Donation after brain-stem death (DBD) - from individuals who have been pronounced dead in an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) using the neurological criteria known as ‘brain stem death testing’. The technical term is now 'donation after diagnosis of death by neurological criteria' (DNC ).

Donation after circulatory death (DCD) - from individuals (who also usually die in ICU) as a result of heart or circulatory failure and who are pronounced dead following observation of cessation of heart and respiratory activity.

2. Through living donation, for example in the case of kidneys or parts of a liver.

The primary aim of the Human Tissue (Authorisation) (Scotland) Bill is to increase the organ and tissue donation rate and as a consequence, the number of organs and tissues donated for transplant. This aspect was crucial to our scrutiny of the Bill and central to many of the key themes which follow.

Deemed authorisation

In addition to the two options currently available, this Bill would establish a third option for the public in relation to donation of parts of their body after death. The three options become —

Opt-in: A person can express a wish to donate their organs or tissue via the NHS organ donor register.

Opt-out: A person can express a wish not to donate their organs or tissue via the NHS organ donor register.

Deemed authorisation: This option would be a significant change to the current legislation. If a person dies without having registered their decision on the organ donor register, they would be deemed to have consented to having their organs taken. This is known as presumed consent or deemed authorisation.

It is argued that, by amending the 2006 Act and adding an additional category of deemed authorisation, the Bill would ensure that individuals who want to donate their organs after death but have not yet registered their wish, would be able to do so. It will be deemed they have consented to having their organs taken.

The Policy Memorandum states that, “deemed authorisation will apply to commonly donated types of organ and tissue e.g. heart, lungs, kidneys, liver, eyes, pancreas, small bowel, heart valves, tendons".

Deemed authorisation would not apply to the following people —

Those under 16;

Those without the capacity to understand deemed authorisation; and

Those who have been resident in Scotland for less than 12 months.

However, the excepted groups above could potentially donate an organ by opting-in to the organ donor register or donation could be authorised by their nearest relative or someone with parental rights and responsibilities for a child.

It is important to note that in all three scenarios above; if the nearest relative, next of kin, or a longstanding friend is in possession of information regarding the deceased wishes on donation, this information could be taken into account at the time of death and potentially change the planned course of action.

The Bill is therefore classed as a ‘soft opt-out’ system as it “incorporates additional safeguards and conditions which might include seeking authorisation from the person's nearest relative, for certain groups of people, or in certain circumstances.

A number of witnesses agreed deemed authorisation was a positive move in the right direction but were not convinced this change alone, would increase transplantation rates in Scotland.

We took evidence in relation to transplantation rates in Wales and Spain and this is set out later in paragraphs 70-86 of the report.

We heard evidence from Gillian Hollis, a lung transplant recipient. Ms Hollis was “not convinced that moving to an opt-out system is the right means of increasing the number of organ transplants” and was of the view that the “situation is far more nuanced".

Furthermore, Dr Sue Robertson, deputy chair of The British Medical Association Scotland (BMA), stated —

We have long supported a move to the opt-out system as part of a package to deliver more transplants for patients who need them. We do not think that such a system can be a stand-alone thing. It will not help our patients unless it is part of an investment in infrastructure to support delivery of that ethos, and to make available more organs for donation.

One of the key arguments in favour of deemed authorisation is that it would appeal to many people in Scotland who support organ donation but have not yet recorded their wishes on the donor register. Dr Robertson argued —

We know that at the moment about 50 per cent of the Scottish population have opted in but that if you ask people, nine in 10 will say that they would wish their organs to be donated. We are looking for that 40 per cent who have not opted in but who actually want their organs to be donated. Those are the people who we want to have that conversation with their families, because we know that they actually want their organs to be donated.

Professor Marc Turner, medical director and designated individual on tissues and cells with the Scottish National Blood Transfusion Service (SNBTS) provided a similar argument, stating that, whilst it would be better to encourage people to make an informed choice on donation and discuss their decision with their families, “some people might never get round to it, some people might not want to make a decision because their own mortality is too unpleasant to think about. I think we absolutely should try to encourage people to make a choice one way or the other, but having deemed authorisation as well covers the gap."

We also heard evidence from Fiona Loud, policy director at Kidney Care UK, who said —

we absolutely believe that changing the rules so that it is presumed that a person will be a donor unless they have said otherwise in life is the right thing to do. However, she also stressed the need for clarity on education and promotion of the Bill. A continuous and consistent message is needed across the country about what the Bill aims to do, what it means and people’s rights under it.

On 13 November, the Health and Sport Committee held an informal meeting with recipients of organ donation. Several of the attendees supported a move to deemed authorisation because they felt it would encourage individuals to think about organ donation and to take a decision on their preferences. It would encourage people to be more proactive and spark a debate.

Our survey provided a contrasting view with some respondents stating consent cannot be presumed where the decision on donation is unknown. In the survey, 29.3% of the respondents had not recorded their wishes on the register. Of these people, 65% did not wish to be an organ donor while 35% did approve.

Gordon Macdonald, parliamentary officer for Scotland at Christian Action Research and Education, also provided an opposing view —

The evidence from Spain suggests that what matters is not legislative change that introduces presumed consent, but improvements to the administrative system and in particular, specialist organ donation nurses. We suggest it would be better to invest money in that. The Nuffield Council on Bioethics found that where specialist organ donation nurses exist, the donation rates increased from 27.5 percent to 68.7 percent.

During the evidence sessions, there was also discussion about whether the Bill provides sufficient clarity on all three options and also equal opportunities to opt-in or opt-out. Rachel Cackett, policy advisor at the Royal College of Nursing addressed this concern in her oral evidence. She stated, "clarity is absolutely key. If the Bill goes ahead, the most important point is that people have to make an informed choice-whatever choice they make- and we have to be 100 percent clear about what they are making a choice about".

Is there a need for 'opt-in'?

Given the introduction of deemed authorisation, we considered why the option to opt-in was being retained in this Bill. Our public survey highlighted some confusion regarding this issue.

Dr Frank Atherton, Chief Medical Officer in Wales, stated, “there is something about aligning with the register. Having an opt-in–a conscious decision – is really important to help provoke conversations within families".

Dr Katya Empson, regional clinical lead for organ donation in South Wales, also expressed her concern about limiting active choice to registering a decision to opt-out, stating, "it would only allow people to make a negative choice. In that situation, the education and publicity campaign that you would have to launch would be about making the choice not to donate and to register your choice not to be a donor. The negativity in such publicity might go against the popularity of organ donation".

The committee also considered whether retaining the opt-in option, in addition to the default deemed authorisation option, would create a two-tier system for organ donation. Referring to the public awareness campaign in Wales following the 2013 Act, Dr Empson said —

In the first year or two after implementation, there was a feeling that there was a two-tiered option. If someone opted in on the register, that was seen as a stronger opt-in than deemed consent. Gradually, over time, the healthcare professionals who are working with the families of patients are seeing those two types of consent as being on the same level and they present them as such to the families who they are working with.

Mandated choice

One further area we considered, although no formal evidence was taken, was that of mandated choice. Under mandated choice, all adults are required to express their preferences regarding organ donation. We considered examples of this from the USA, namely; the states of Texas, Virginia, California and Illinois, noting the first two states have abandoned this system whilst the numbers agreeing to opt-in are low despite the system being in force since 2010 and 2006 respectively.

We agree with the views of the Scottish Government as set out in the Policy Memorandum, that such a system raises significant issues by forcing people to choose a decision on donation. We also recognise the practical difficulties of establishing and enforcing a system to collect this information.

Rights of the individual

Under the 2006 Act, organs and tissues can only be donated by someone if either the person has authorised donation before death or if their nearest relative authorises the donation on their behalf.

The introduction of a new category in this Bill, ‘deemed authorisation', refers to circumstances where a deceased person has no recorded decision. In this instance, their authorisation may be deemed and organ and tissue retrieval may proceed, subject to family/next of kin authorisation. We heard legal and ethical questions relating to this aspect of the Bill.

In our public survey, the most commonly expressed opinion on deemed authorisation was in relation to human rights and bodies being owned by the state. Many people also argued that presumed consent is not consent at all and there is a risk that organs could be taken from the deceased against their wishes. One individual responding to our survey stated —

I am a donor, my family are donors. I registered my son as a child (with his consent). My issue is with presumed consent, turning my choice and therefore my body into yet another chattel of the state. I know that sounds and looks obscure and obtuse, but I feel that very strongly. It would be nice to be asked.

On 27 November, witnesses discussed whether “deceased people have rights and who owns the body of a deceased person”. Dr Emily Postan, deputy director of the Mason Institute for Medicine, Life Science and Law at the University of Edinburgh, suggested “a deceased person does not have interests, but the person they were before they died certainly did, and respect for those interests is an essential concern alongside family interests".

In addition, Dr Callum McKellar, director of research at the Scottish Council on Human Bioethics stated, "nobody owns a body. People have responsibilities to a body, but there is no ownership".

At our meeting on 27 November, the Minister for Public Health, Sport and Wellbeing confirmed, “the current legislation and the proposed legislation are clear that the right to authorisation rests with the potential donor".

Gift element

Whether deemed authorisation will remove the element of ‘gift’ in donation was also a contentious issue for some respondents.

On 11 June 2018, Aileen Campbell, previous Minister for Public Health and Sport stated, “Organ and tissue donation is an incredible gift".

The notion that donation is an active gift and the introduction of deemed authorisation could undermine this special relationship between donor and recipient, caused concern for some witnesses.

Gillian Hollis, a lung transplant recipient, expressed her sincere gratitude to her donor and their family for taking an active choice to donate. She stated, "should the Bill go through, it is very important that the element of gift is retained as much as possible, because it is people helping other people. A donation is a true gift".

Providing a similar argument, Harpreet Brrang, information and hub research manager with the Children’s Liver Disease Foundation, gave an example of a Scottish child who had recently received a liver transplant. The mother of the child said "she viewed the donation as a gift- that someone chose to donate. She would have felt slightly more uncomfortable if she thought it had not been an active choice".

Several faith groups in Scotland expressed concern regarding deemed authorisation and the ability to retain the element of gift. Whilst the Catholic Church acknowledges there is a need for more organs to be donated, they view donation as a gift which “must be freely given”. Adding, “it is not morally acceptable if the donor or his/her proxy has not given explicit consent".

The Christian Institute argued —

When consent is presumed, the whole ethos of donation is lost. Instead of being a gift, it almost becomes an obligation. Although the Government’s aim to save lives is laudable, it must not take advantage of people’s inaction. That is unethical.

Dr Macdonald from CARE for Scotland highlighted what he saw as an unintended consequence of deemed authorisation – a potential increase in the number of people actively choosing to opt-out of the system. He argued, “if there is a perception that donation is no longer a gift and the state is claiming a right, there is a danger that people will choose to opt-out of the system which seems to have happened in Wales".

These views were not echoed by patients currently on the transplant waiting list. Attendees to our informal meeting argued that any organ is welcome regardless of whether it is retrieved via presumed consent or opt-in and the gift element is not an issue for them. They advised that few details of the donor are passed on to the recipient so they would be unaware of how the organ was retrieved

Dr Katya Empson Regional Clinical Lead for Organ Donation, suggested that in Wales, "the concern has not been borne out in implementation. There is no sense that people no longer see a donation as a gift; donor organs are still valued as a wonderful gift by the public and by people who are involved directly and closely with the process".

Wales

Prior to the introduction of the Human Tissue (Authorisation) Bill in Scotland, the Scottish Government were keen to review the evaluation of The Human Transplantation (Wales) (Act) 2013 which came into force on 1 December 2015.

An impact Evaluation of the first years of the Human Transplantation (Wales) Act was published on 1 December 2017.

The Welsh Government initially estimated that the legislation would “result in a 25 to 30 per cent increase in the number of donors". However the evaluation found that, whilst some progress has been made, the opt-out system of presumed consent has not provided the anticipated increase. The lead researcher, Richard Glendinning advised us that"there were a lot of positive signs on some of the softer measures to do with attitudes of the public and of national health service staff, but during the formal evaluation period that we reported on a year ago, there had been no significant change in donor levels".

However, in the past 12 months since the publication of the report, there has been a marked increase in donation rates, which it was suggested to us, is due to a build-up of knowledge, public awareness and support over a period of time.

When asked if the Human Transplantation (Wales) (Act) 2013 has met or is beginning to meet its fundamental purpose of increasing the number of organs available for transplantation, Dr Frank Atherton, Chief Medical Officer for Wales stated, “we are still in a learning process but generally, we believe that it has been a positive move. we feel that donation is going in the right direction”. Dr Frank Atherton also argued —

My overarching point would be that the legislation has been really important part of our process to improve organ donation rates in Wales but it is not the whole story. We know that a range of things need to happen – we need to get infrastructure for organ donation right, and we need to get the public engaged.

The Minister for Public Health, Sport and Wellbeing was realistic in his expectations at our Committee meeting on 27 November. He stated, “opt-out on its own would not result in a significant increase in donations". He argued that an opt-out system is part of a package of measures developing over several years.

Spain

We were aware that Spain has the world’s highest rate of organ donation from deceased donors (approximately 34-35 per million of population), more than twice that of the UK (approximately 15 per million of population).i We wanted to gain insight into the reasons for this difference.

We received evidence to suggest that moving to an opt-out system of presumed consent is not the panacea and a range of measures, combined with cultural differences within the country have contributed to the number of donations available.

Spain introduced presumed consent in 1979 and was therefore classified as operating an opt-out system. However, a year after implementation, a royal decree clarified that “opposition to organ donation could be expressed in any way, without formal procedures. The Spanish legal system’s interpretation of this decree was that the best way to establish the potential donor’s wishes was by asking the family. The family is always asked for consent, and the family’s wishes are always final". i Spain does not operate an organ donor register and the option to opt-out is not promoted.

In 1989, Spain set up a nationwide transplantation co-ordination system. This system includes co-ordinators in each of the 17 regions and a local co-ordinator in every hospital. These professionals identify potential organ donors by closely monitoring emergency departments and tactfully discussing the donation process with families of the deceased.

Former Director of the National Transplant Organization of Spain, Dr Rafael Matesanz and colleagues wrote —

the presumed consent legislation in Spain was in place for 10 years, from 1979, with little effect on organ donation rates. It was the introduction of the comprehensive transplant coordination system in 1989 that was coincident with the progressive rise in organ donation in Spain to its current enviable levels.

In addition to written evidence from Spain, Lesley Logan, regional manager for organ donation in Scotland also noted that “in the Spanish system, families are approached up to six times" to seek authorisation to donate organs from a deceased relative. This method is followed in Spain’s intensive care system which helps to increase transplantation rates.

Lesley Logan also noted the importance of the Roman Catholic Church in Spain. The Church “supports organ donation, and people have extended families, so there are demographic, cultural and religious reasons why donation might be better placed there".

We also heard evidence regarding a high number of intensive care beds available in the country. Lesley Logan provided information on a new initiative for Spain which has created a surge in donation rates, but raised concern about a similar approach being adopted in Scotland —

Families of individuals in hospital wards who are not ventilated are being asked, whether, following the individual’s catastrophic event – for example, a stroke - and their having entered a pathway of care in which they are likely to die, donation may be possible; if so they are electively ventilated. That causes significant ethical concern.

Spain can retrieve organs in all of their hospitals. This compares to the UK where retrieval of organs is undertaken by specialised doctors in fewer locations. The model of healthcare also differs between the two countries.

Dr Steven Cole, consultant in intensive care medicine at Ninewells Hospital, Dundee, stated,“Scotland has fewer intensive care beds per thousand population than the rest of the UK. Intensive care is a very scarce resource. He went on to sugges that, “one of the ways through which we could effect change, would be to invest more in intensive care capacity around the country. Donation would be a by-product of that".

We asked the Minister for Public Health, Sport and Wellbeing to look at the issue of intensive care beds across Scotland and he indicated the existing strategic forecast which runs until 2020 provided no expectation the Bill will increase donation rates above existing capacity. "even if we increased donation to the levels that we hope for, it is unlikely that would lead to the number of transplant units exceeding the forecast in the current strategy Commissioning Transplantation to 2020". He recognised however this was an organisational issue which could be addressed outwith the Bill.

We acknowledge the need for absolute clarity in this Bill. It is essential individuals feel able to make an informed choice about organ donation whether by opting-in, opting-out or understanding the implications of deemed authorisation. We support the proposed approach to introduce presumed consent alongside retention of opt-in.

We recognise some groups have concerns about the potential impact on donation rates should people consider their rights as individuals are affected. Overall, we do not expect this to become a significant problem although we recommend the Scottish Government take steps to monitor public attitudes after a period of time of perhaps five years after the Act comes into force.

The Committee received evidence to suggest that the link between an increase in donation rates and presumed consent in Wales is inconclusive. Like Wales, we consider a longer period of time to evaluate the impact of the Act is required. It is not possible to make direct comparisons between Scotland and Spain due to the cultural differences and different health care models.

We note the creation of the trauma centres across Scotland and we seek confirmation each has the capacity to support the aims of this Bill.

We further recommend the Scottish Government reviews the infrastructure across the country for organ donation.

Authorisation process

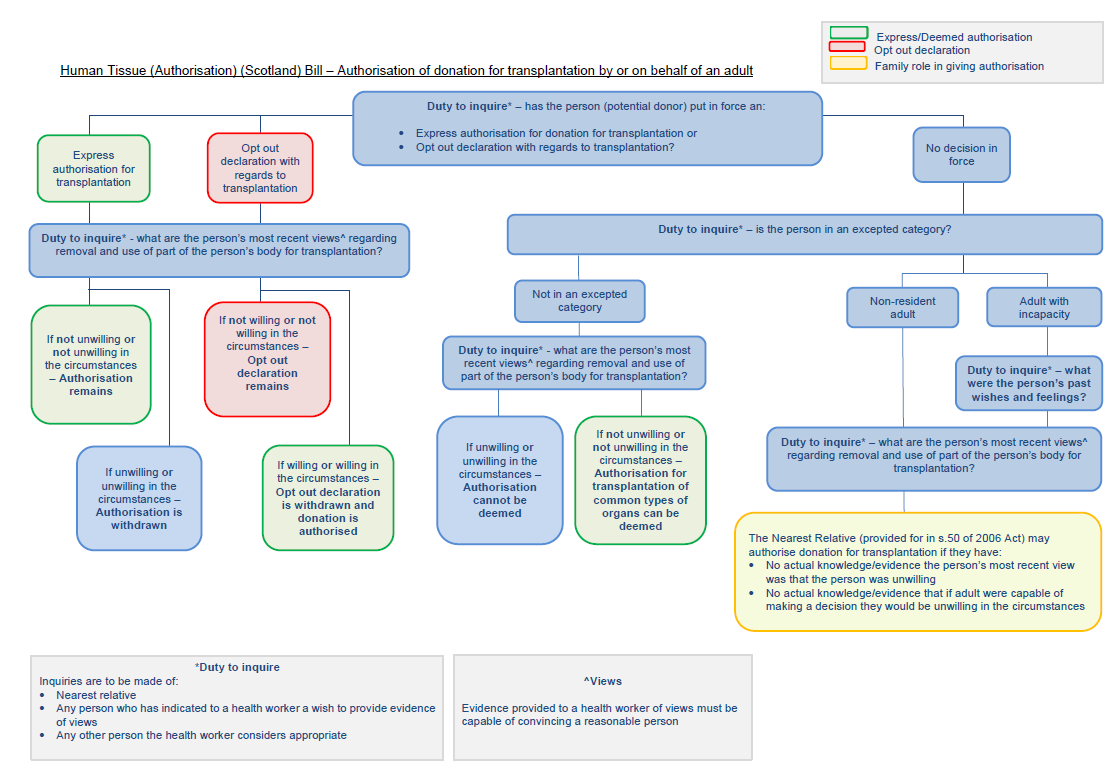

The Scottish Government provided us with the following flowchart to illustrate the authorisation process for organ donation should the Bill be enacted.

The Scottish Government

Organ donation and the allocation of organs to transplant recipients is managed across the UK by NHS Blood and Transplant (NHSBT), a Special Health Authority established under the NHS Act 1977. NHSBT employs specialist nurses:organ donation (SNODs) who are specially trained to approach families about donation in a sensitive way. The specialist nurses are “skilled communicators who routinely discuss donation with families in crisis, families in conflict and families with complex dynamics". They are trained to work with families for several hours, often late in the evening, to come to a consensus view on donation.

The Bill places a ‘duty to inquire’ on health workers. In practice, this role will be undertaken by ‘SNODS’. Under the current system, when a person dies in an intensive care unit and are deemed eligible for donation, SNODs will check the organ donor register to ascertain if the person has recorded a decision to donate or not to donate. The family will also be asked if there was any known change to the decisions made by the potential donor. The Bill is proposing a continuation of this approach. Additional information would also be requested in the following circumstances should they arise —

To authorise donation for those to whom deemed authorisation would not apply to i.e. those without capacity and people resident in Scotland for less than 12 months (for children this would be the person(s) with parental rights and responsibilities;

To authorise the donation of organs and tissues for purposes other than transplantation i.e. education, training, research and audit, or quality assurance; and

To authorise the donation of excepted body parts.

In order to understand the importance of the authorisation process, we held an informal meeting with Lesley Logan, regional manager for organ donation in Scotland and three of her colleagues on 23 October 2018. The session was informative with a presentation and role play demonstration illustrating the way in which families are approached by the SNODS and the types of questions asked both in the authorisation form and the medical and social history questionnaire.

A key point from this meeting , and which was subsequently raised in oral evidence sessions, was the sheer volume of information required from families at an incredibly difficult and distressing time. Subsequent written evidence illustrated there can be up to 350 questions for the family to answer, depending in the individual’s medical history or lifestyle choices. The questions are asked over a three to four hour period, often late in the evening and following the loss of a relative in tragic circumstances. We ascertained the number of questions is comparable to other countries but some witnesses argued this lengthy process was acting as a deterrent to families providing consent of organs from their deceased relative.

When asked about the authorisation process, Gillian Hollis, a lung transplant recipient stated, “I am not sure of the extent to which bureaucracy is giving a better understanding of what can and cannot be transplanted”.

Harpreet Brrang, information and research hub manager with the Children’s Liver Disease Foundation also commentated on the process arguing that “it would be fantastic if the Bill could be used as an opportunity to cut down on the bureaucracy and the number of questions that people are asked at such a difficult and sensitive time".

We pursued this aspect of the Bill during our informal meeting with families who have authorised the donation of an organ from their relative. They recognised there were numerous questions on the questionnaire and authorisation form, some quite difficult, but they appreciated they were asked sensitively. They recognised the questions were designed to minimise risk for the recipient but some attendees wondered if a better balance could be achieved. Attendees questioned whether medical records could be used and mention was made of Canada and its on-line records system.

Lesley Logan explained the purpose of the questions in her oral evidence to the Committee, stating, “the questions are absolutely necessary because our job is to ensure that transplantation is safe, first and foremost for the recipients”.

This view was also echoed by Dr Frank Atherton, Chief Medical Director in Wales. He confirmed the need for safeguards and information, highlighting this aspect was not about the legislation but about policy and practice.

During the course of our inquiry, the need to mitigate risk and ensure transplantation is safe for each recipient was brought into sharp focus by the publicity surrounding a transplant patient who developed terminal cancer from a donor kidney.

The Minister for Public Health and Wellbeing acknowledged this tragic case and confirmed any lessons to be learned will be applied across the whole donation and transplantation system. With regards to the number of questions on the medical and social history questionnaire, he stated “our specialist nurses ask the questions in a very sensitive way – they are trained to do that. We need to take the lead from clinicians to ensure we get the balance right in assessing safety in the donation process".

Rights of the family and their consent

The role of the family was highlighted to us throughout our inquiry as being fundamental to the success of this Bill. It was a recurring theme throughout each oral session and in written evidence. In particular, we heard concerns over how much influence the family would continue to hold under the proposed legislation and if the rights of the donor would also be upheld. Families would not be able to override the decision of the deceased but they would continue to play a pivotal role in the organ donation process.

It also became clear to us the family have a dual role in relation to consent and providing information on the medical and social history of the donor.

We questioned whether the family consent rate was a barrier to donation. David McColgan, senior policy and public affairs manager for devolved nations with he British Heart Foundation, argued a culture change is needed in Scotland with regards to donation. He advised —

countries that have high donation rates have high family consent rates. Scotland has the highest percentage of the population who are opted in to organ donation but we are the lowest when it comes to family consent rate.

Lesley Logan regional manager for organ donation in Scotland, advised that whilst it is rare, approximately six families per year will override the decision of the donor.

The most common reasons for family refusal in 2016/17 include —

family member had not expressed an interest to donate;

unsure the family member would have agreed to donate;

felt the process is too long;

didn’t want the family member to have surgery to the body; and

felt family member had suffered enough.

Dr Stephen Cole, consultant in intensive care medicine, Ninewells Hospital indicated, “having dealt with this situation on a daily and weekly basis, I would find it difficult in my profession to override the wishes that are expressed by those patients’ relatives. I do not think we can push families into a situation in which donation is forced through against their wishes”.

Professor Marc Turner, Medical Director and designated individual on tissues and cells with the Scottish National Blood Transfusion Service (SNBTS), highlighted the potential dilemma when he said —

from an ethical perspective one should give primacy to the views of the donor. In reality the family could have a defacto veto simply by refusing to answer the donor selection questions, in which case we could not proceed with the donation in any case."

He also confirmed he does not believe a legal requirement for relatives to answer the questions could be written into the law.

Providing a different view in written evidence to the Committee, Professor Alison Britton, Convener of the Health and Medical Law Sub-committee of the Law Society of Scotland, argued —

we are placing the rights of the relative far above the integrity of the deceased and the need of a possible recipient. The last autonomous wish of the donor is potentially being thwarted simply because he or she is in no position to object.

Referring to deemed authorisation specifically, Professor Britton explained it is incredibly difficult for families to replicate consent, they can only give permission for organ donation.

In agreement, Dr Emily Postan, deputy director of the Mason Institute for Medicine, Life Science and Law at the University of Edinburgh noted, “if it genuinely is the case that no one knows the deceased person’s wishes it is misleading to say that the wishes of the family somehow give better access to those wishes and are the preferred option".

It was suggested that if health care professionals can continue to work closely with families, this may provide the opportunity to increase the number or transplants available for donation.

On 13 November, Lesley Logan, discussed the way in which her team would adapt the conversation to the last known wishes of the donor, in particular where the intention is to proceed using deemed authorisation. She said that, “deemed authorisation allows us to start the conversation with something tangible”. She also also argued that it allows the nurses to be more "culturally presumptive" with language as the donor has not specifically made the decision to opt-out before their death, meaning donation is a possibility.

Evidence from Dr Katya Empson, regional clinical lead for organ donation in South Wales, reinforced this point. She advised, “there was a significant shift in practice [in Wales following the 2013 Act] from what had previously been a family and relative-centred approach to one that was more to do with presumptive facilitation of the deceased’s decision".

With regards to the authorisation process and the number of questions asked to families prior to donation, the Minister confirmed this is a clinical decision to ensure the safety of the donor and the recipient. He did not think anything could be added to the Bill to force the family to co-operate.

Referring to rights of the individual, the Minister reiterated, “the right to authorisation rests with the potential donor. Clearly the decision to proceed with a donation is a clinical one, and that is a different aspect”. He also clarified,“when the family are asked [about donation], they will not be asked for their views; they will be asked about what they believe were the views of their deceased relative who is the potential donor".

It is clear the way in which families are approached following the death of a relative will be critical to the success of this Bill. If, as the Minister states, the decision to proceed with a donation is a clinical one, it will be the responsibility of the SNODs to continue to ascertain and give primacy to the final wishes of the deceased and utilise deemed authorisation in circumstances were the decision of the deceased is unknown.

The need for families to be aware of their relative’s decision cannot be underestimated in this Bill. Communication is vital to ensure the individual’s wishes are given priority at their time of death.

We note the vital role of the SNODs in supporting families throughout the organ donation process and the approach taken to ascertain the final wishes of the deceased.

We recommend a review of the authorisation process in Scotland to ensure each and every question is of clinical importance. As organ donation is a UK wide framework, we recognise this requires joint collaboration with England, Wales and Northern Ireland. It is imperative this review involves patients and families who have authorised the donation of an organ.

We support the views of Dr Cole that in practical terms it would not ultimately be possible for the medical profession to proceed with donation against the wishes expressed by patient relatives.

We also recommend investigating the use of an online medical system similar to Canada, which could be used to assist the authorisation process.

Pre-death procedures

The 2006 Act currently allows authorisation for donation to be given after the death of the potential donor. This Bill contains provisions about when certain medical procedures can be undertaken before a person dies in order to help facilitate transplantation. Theses would be known as pre-death procedures. (PDP)

Currently, some PDPs are undertaken but only where the person has previously made clear a wish to donate, or where their family has authorised donation. However, the Bill seeks to clarify the circumstances in which PDPs may go ahead, and this includes where authorisation for donation is deemed.

The Bill creates two types of procedure (type A and B) with further details which to be contained in regulations. It is anticipated that type A procedures would be more routine (e.g. blood/urine tests) and these would be allowed to proceed under deemed authorisation or when the person has opted-in.

Type B procedures are anticipated to be less routine including the administration of medication or more invasive tests. Regulations could also specify what requirements would apply to type B procedures and how they could be authorised. Deemed authorisation would not automatically apply to type B procedures.

The Policy Memorandum for the Bill states, “in all cases where pre-death procedures may be undertaken, a decision will have been taken that the person is likely to die imminently and that if the person is receiving life sustaining treatment this will be withdrawn”.

It is also emphasised that procedures cannot be carried out “if it is known that the person would not have consented and, in line with the general approach in the Bill, if they are contrary to the person’s wishes and feelings, as far as these are ascertainable.

During our informal meeting with families who have authorised donation, we asked their opinion on pre-death procedures. They expressed their discomfort of any invasive tests on relatives but accepted the notion of blood tests and other routine tests.

Dr Empson confirmed that whilst health professionals would not go through specifics with families for every blood test taken, families would be involved with tests which help to certify death by neurological criteria, for example to observe the brainstem death test taking place. She explained —

When a potential donor is proceeding with donation, appropriate information is shared sensitively and compassionately with families. Families are provided with the opportunity to observe and understand processes.

The families we met at our informal meeting echoed this point, with one describing the experience of observing a brain test of a deceased relative. Viewing this procedure provided reassurance about their decision to donate.

Further concern relating to pre-death procedures was the possibility they would accelerate death in order for donation to take place. Professor Alison Britton, convener of the Health and medical law sub-committee of the Law Society of Scotland, queried whether, “if there has been an expression of the intention to donate organs those caring for a person might not go the extra mile to preserve life”.

Professor Britton expressed the need for communication with families authorising donation. She stated that “people are frightened” and greater clarification is required due to the different definitions of death; ethical, legal and brain stem death.

Some respondents to our survey also expressed concern about a potential conflict of interest for the Doctor. One respondent stated, "Doctors should be concerned with prolonging the life of the patient, rather than viewing them as a source of organs".

The Law Society highlighted this issue in written evidence to us noting that careful consideration must be given to process and ethics otherwise this may be perceived as contradictory to the Hippocratic Oath, where the first consideration is for the health and wellbeing of the patient.

When he gave evidence, the Minister reiterated the need for transparency to maintain a high degree of trust in donation.

We acknowledge the strong concerns expressed from members of the public and witnesses to the committee with regards to pre-death procedures and the health and well being of the patient prior to organ donation.

We understand pre-death procedures are considered to be accepted practices essentially undertaken to support and facilitate a potential donor. Procedures are agreed at UK level by the UK donation ethics Committee.

We have noted the work undertaken by the SNODs in explaining the procedures and reasons to relatives. They are skilled communicators and their role in working with families is vital to alleviate concerns.

We recognise the careful steps taken to inform and involve families in pre-death procedures and we accept the proposals in this Bill. We recommend the procedures be reviewed in 5 years.

Post-transplant care

During our consideration of evidence, we heard about the support provided to families who have donated an organ from their deceased relative. Following donation, families are provided with a variety of items of appreciation, ranging from a card and organ donor family gold heart pin for each family member to a St John’s Scotland medal, presented on behalf of The Queen.

When we met with families who have authorised donation at our informal meeting, they told us how much they appreciated the items, particularly the certificate and badge. All appreciated the information received post transplant which advised whether the donation(s) had been successful.

We applaud the actions taken to ensure families feel valued and appreciated following the organ donation process. We recommend this continues even if there is an increase in the number of organs and tissues donated.

We recommend the support given to families is included in the evaluation of the Bill, five years from the date of implementation of the Act.

Mental health

Mental Health was also raised in relation to those who have experience of the organ donation process. Members heard from three groups: people who have received donated organs, family members who have authorised the donation of organs and people currently on the organ transplant waiting list.

Attendees at our informal meeting provided valuable insight into their experiences.We heard about a variety of issues affecting their mental health. One attendee described it as a "lonely experience" and others discussed the financial and emotional distress when waiting for an organ to become available. We heard that even when an organ is found, 40% of transplants do not proceed due to complications on the day of surgery. Returning to the transplant waiting list causes further delay, disappointment and anxiety.

Whilst some attendees welcomed the introduction of the Donor Family Network and post-transplant support groups set up in some hospitals, others felt there was a need to increase the number of counsellors available.

It was suggested there is limited support for patients on the transplant waiting list, for recipients post-surgery and for families who have authorised the donation of an organ. These needs were acknowledged by Lesley Logan, particularly with the number of transplants expected to increase.

We were advised that in Wales, no such support is provided. It was emphasised that for many families, organ donation has been a positive experience and it has helped them come to terms with their loss.

By contrast, we understand that for those donating blood stem cells or bone marrow to people with blood cancer and blood disorders, a Clinical Nurse Specialist provides post-transplant support from Queen Elizabeth University Hospital, Glasgow. Transplant patients also receive personalised care relating to all aspects of their recovery including physical, emotional, psychological and social care.

Having heard first-hand evidence suggesting there is a gap in mental health funding relating to pre and post-transplant care, there should be no difference in the approach between those donating blood stem cell or bone marrow and those making donations under this Bill. We recommend the Scottish Government improves the services available for patients on the transplant waiting list, recipients of organ donation and families who have authorised the donation of an organ from a relative.

Adults with incapacity

The Bill recognises that a person who lacks capacity over a significant period of time, for example, someone suffering from dementia, cannot reasonably be expected to have made a choice in favour of donation by not opting out. The Policy Memorandum states the Bill is not prescriptive on the period of time as it is likely to vary from case to case.

When asked whether the Bill should be more prescriptive in relation to the length of incapacity for an individual, Dr Katya Empson discussed the Welsh legislation. Dr Empson confirmed, “The situation is not clear, there is no specific time period in our legislation. In some ways, it is safer to allow the healthcare professionals who are involved to make that decision, based on their understanding of who that person was and for how long they had not had capacity”.

However, people without capacity could also be considered as potential donors if the necessary authorisation was in place. Either through a wish they had recorded when they did have capacity, or with the approval of their nearest relative. The nearest relative would be required to consider the past wishes and feelings of the person, as far as they were known.

This was an issue which caused some concern for witnesses. Shaben Begum, director of the Scottish Independent Advocacy Alliance argued, “I would not want to see the legislation discriminating against a group of people and saying they cannot donate their organs”. Ms Begum also argued that capacity is not a “black and white issue” and believed there should be consideration of power of attorney covering organ donation.

There needs to be somebody there who is independent and does not have an agenda within the situation but is there to safeguard an individual’s wishes and reinforce their rights and ensure their rights and wishes are being listened to appropriately.

Stephanie Virlogeux, Solicitor at the Scottish Government, confirmed the definition of an adult who has been incapable of understanding deemed authorisation, has intentionally been left flexible. “A more rigid definition could lead to unintended consequences and difficulties in fulfilling the wishes of people who want to become donors".

We are content with the provisions in the Bill relating to adults with incapacity.

Engagement strategy

The Human Tissue (Authorisation) (Scotland) Bill adds to the existing duties of Scottish Ministers under the 2006 Act to promote information and awareness about authorisation of transplantation and pre-death procedures, and to establish and maintain a register of information relating to decisions to authorise, or not authorise, donation.

We heard evidence to suggest there was a need for clarity around the terminology and message of the Bill in relation to deemed authorisation. David McColgan, senior policy and public affairs manager for devolved nations at The British Heart Foundation argued, “we should learn from the experience in Wales, where there was an 18 month campaign and the vast majority- over 80 per cent of the population – understood the legislation”.

Dr Frank Atherton highlighted the need to invest in resources and to engage with hard-to-reach, minority groups by providing outreach opportunities with the SNODs and producing materials in numerous formats including BSL, braille and several languages. He explained that extensive public information campaigns have been running for the past two years in order to provide clear and factual information about the legislative change in Wales and the implications of the Act. Dr Atherton confirmed, “the budget for all organ donation communications activity in 2017-18 increased to £350k to accommodate the advertising campaign (increased from £200k in 2015-16)”.

Evidence from Wales also highlighted the need to ensure publicity of the law is maintained. Dr Frank Atherton argued that public awareness is “not something that we can do and forget; it is not a one-off thing. We have to continually drip-feed that information as part of our communications message".

Dr McKellar echoed this point with a requirement for the process of consent to be “continual" and for people to be reminded of their choice but also reminded of their right to withdraw consent at a later date if they wish.

The Minister for Public Health, Sport and Wellbeing confirmed the Scottish Government will work with partners NHS Blood and Transplant (NHSBT) and Scottish National Blood Transfusion Services (SNBTS) to ensure the “message is able to reach the widest possible group of people”.

Engagement with children

Deemed authorisation would apply to children over the age of 16. This point was of interest during the scrutiny of the Bill as the age of consent differs across the UK, with Wales unable to retrieve organs from children (where the recorded wish on donation is unknown) until the age of 18.

When asked if different ages for deemed authorisation across the UK could cause legal problems for transplants, Lesley Logan, regional manager for organ donation in Scotland, confirmed, “we would still accept an organ from a child who died in Wales". In agreement, Dr Atherton provided written evidence to us confirming the position in Wales. He confirmed, “there would be no impediment to this as it is covered by section 3 of our Act. Section 3(3) makes the storage and use of relevant material lawful where organs and tissues have been imported into Wales from outside Wales”.

We heard evidence to suggest a robust engagement programme is required for children, prior to their 16th birthday to ensure they are well informed of the three options available to them; opt-in, opt-out or default to deemed authorisation. Fiona Loud, policy director, Kidney Care UK, highlighted the use of social media platforms to engage with children before they reach the age of consent and the need for children to have crucial conversations with their families, suggesting, “children are the change makers”.

Dr Gordon Macdonald from Scotland Action Research and Education also noted “there are opportunities in the system to engage young people, for example when they sit their driving test or apply for their driving licence".

Dr Frank Atherton discussed the ways in which the Welsh Government engages with young people on the issue of deemed authorisation. In his written evidence he confirmed —

We were able to utilise UCAS to communicate with new students. We were also able to arrange for NHS Wales systems to generate a letter to all ‘rising 18s’ advising them that deemed consent will apply, and linking this decision to other important life changes such as leaving school, starting work, going to university.

We understand the Anthony Nolan Trust has been linked with the Scottish Fire and Rescue Service (SFRS) since 2009. SFRS volunteers deliver presentations in secondary schools across Scotland, raising awareness on leukaemia and other blood cancers. They also operate promotional events to encourage students to join the stem cell donor register.

The Scottish Government's Bill Team Leader confirmed, “there is a duty on Ministers regarding information and awareness; that is led by the Scottish Government and it follows the general marketing principles. The prospective costs of the work have been included in the financial memorandum. The schools pack has been developed and it could be further developed in the future".

The schools pack is described in the Policy Memorandum as an "internationally-recognised educational resource used to increase awareness amongst pupils about organ and tissue donation".

We welcome a high profile public information campaign for at least 12 months before commencement of the system but suggest the Scottish Government reviews the engagement strategy in Wales following the implementation of the Human Transplantation (Wales) Act 2013. We recommend reviewing their methods of reaching new residents to the country, different demographics, various cultural backgrounds and ethnic minority groups to ensure the law is upheld and maintained with public awareness at the highest level.

Following the strategy applied in Wales, we also recommend undertaking outreach sessions with minority groups in order to explain the implications of the Bill with regards to deemed authorisation (presumed consent).

In relation to engaging with children specifically, we welcome the work undertaken by the Anthony Nolan Trust and their collaboration with Fire and Rescue Service (SFRS). SFRS volunteers have delivered presentations and events in secondary schools and colleges, raising awareness of blood cancers and the stem cell donor register. This has increased the number of donors available to save the lives of others, including children.

We recommend a collaboration with the Anthony Nolan Trust and Fire and Rescue Service (SFRS), adding organ donation to their programme in secondary schools and colleges. An umbrella of information covering blood cancers, stem cell donation and organ donation could raise awareness but also utilise resources in Scotland. The secondary school and college curriculum should include equal information on the three options available; how to opt-in, how to opt-out and the meaning of deemed authorisation. This programme should begin 12 months prior to the implementation of the Act and be sustained to ensure universal coverage.

We also recommend utilising social media platforms to engage with children before they reach the age of consent and continuing the campaign for future years to include application for a driving licence and entrance to University (UCAS).

Finance Committee and Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee Consideration

The Finance Committee issued a call for views on the Financial Memorandum of the Bill and received 3 responses. The issues raised included additional funding for transplantation, staffing, new technologies and a digital health strategy

The Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee considered the Bill on 4 September and 6 November 2018. The Committee published its report on the Bill on 11 June 2018 and we have nothing further to add to their report.

Overall conclusions

The Committee supports the general principles of this Bill.

We have received evidence to suggest this Bill alone will not achieve an increase in donation rates. We consider an ongoing, targeted engagement strategy which encourages greater awareness of the benefits and requirements of organ donation, is required. The role of the specialist nurses and the way in which they communicate with relatives prior to donation is also key to the success of this Bill.

We have endeavoured to raise constructive suggestions throughout this report and seek further detail and information to strengthen the Bill. We look forward to receipt of the Scottish Government’s response to the issues we have raised.

Annexe A - Minutes of Meeting

20th Meeting, 2018 (Session 5) Tuesday 26 June 2018

4. Human Tissue (Authorisation) (Scotland) Bill (in private): The Committee considered and agreed its approach to the scrutiny of the Bill at Stage 1.

25th Meeting, 2018 (Session 5) Tuesday 2 October 2018

4. Human Tissue (Authorisation) (Scotland) Bill (in private): The Committee considered and agreed its approach to the scrutiny of the Bill at Stage 1.

26th Meeting, 2018 (Session 5) Tuesday 23 October 2018

2. Human Tissue (Authorisation) (Scotland) Bill (in private): The Committee received an informal background briefing to inform their scrutiny of the Human Tissue (Authorisation) (Scotland) Bill at Stage 1.

28th Meeting, 2018 (Session 5) Tuesday 6 November 2018

5. Human Tissue (Authorisation) (Scotland) Bill: The Committee took evidence on the Bill at Stage 1 from—

David McColgan, Senior Policy and Public Affairs Manager (Devolved Nations), British Heart Foundation Scotland;

Harpreet Brrang, Information and Research Hub Manager, Children's Liver Disease Foundation;

Gillian Hollis, attending in personal capacity as a lung transplant recipient (2004);

and then from—

Shaben Begum, Director, Scottish Independent Advocacy Alliance;

Fiona Loud, Policy Director, Kidney Care UK; and

Dr Gordon Macdonald, Parliamentary Officer, CARE for Scotland.

7. Human Tissue (Authorisation) (Scotland) Bill (in private): The Committee considered the evidence heard earlier in the meeting.

29th Meeting, 2018 (Session 5) Tuesday 13 November 2018

1. Human Tissue (Authorisation) (Scotland) Bill: Members of the Committee reported back on the informal evidence sessions they attended this morning prior to the public meeting commencing. Members heard evidence from one of three groups: people who have received donated organs, family members who have authorised the donation of organs, and people currently on the transplant waiting list.

2. Human Tissue (Authorisation) (Scotland) Bill: The Committee took evidence on the Bill at Stage 1 from—

Dr Sue Robertson, Deputy Chair, BMA Scotland;

Rachel Cackett, Policy Adviser, Royal College of Nursing Scotland;

Mary Agnew, Assistant Director - Standards and Ethics, General Medical Council;

and then from—

Dr Stephen Cole, Consultant in Intensive Care Medicine, Ninewells Hospital, Dundee, representing the Scottish Intensive Care Society;

Lesley Logan, Regional Manager, Organ Donation: Scotland, NHS Blood and Transplant; and

Professor Marc Turner, Medical Director and Designated Individual (Tissues and Cells), Scottish National Blood Transfusion Service.

4. Human Tissue (Authorisation) (Scotland) Bill (in private): The Committee considered the evidence heard earlier in the meeting.

30th Meeting, 2018 (Session 5) Tuesday 20 November 2018

1. Human Tissue (Authorisation) (Scotland) Bill: The Committee took evidence on the Bill at Stage 1 from—

Richard Glendinning, now with Ipsos Mori and former Director of Social Research and Lead Researcher on the Evaluation of the Human Transplantation (Wales) Act, Growth from Knowledge (GfK UK);

Dr Frank Atherton, Chief Medical Officer/Medical Director, NHS Wales, Welsh Government;

Dr Katja Empson, Regional Clinical Lead for Organ Donation South Wales, Cardiff and Vale University Health Board.

4. Human Tissue (Authorisation) (Scotland) Bill (in private): The Committee considered the evidence heard earlier in the meeting.

31st Meeting, 2018 (Session 5) Tuesday 27 November 2018

1. Human Tissue (Authorisation) (Scotland) Bill: The Committee took evidence on the Bill at Stage 1 from—

Professor Alison Britton, Convenor to the Society's Health and Medical Law Committee, the Law Society of Scotland;

Dr Emily Postan, Early Career Fellow in Bioethics and Deputy Director, Mason Institute for Medicine, Life Sciences and the Law, The University of Edinburgh;

Dr Calum MacKellar, Director of Research, the Scottish Council on Human Bioethics;

and then from—

Joe FitzPatrick, Minister for Public Health, Sport and Wellbeing;

Claire Tosh, Bill Team;

Fern Morris, Bill Team; and

Stephanie Virlogeux, Legal Directorate, all Scottish Government.

Emma Harper made a declaration of interest, the full details of which can be viewed in the Official Report of the meeting.

3. Human Tissue (Authorisation) (Scotland) Bill (in private): The Committee considered the evidence heard earlier in the meeting.

2nd Meeting, 2019 (Session 5) Tuesday 22 January 2019

6. Human Tissue (Authorisation) (Scotland) Bill (in private): The Committee considered a draft Stage 1 report and agreed to consider a revised draft at its next meeting.

3rd Meeting, 2019 (Session 5) Tuesday 29 January 2019

3. Human Tissue (Authorisation) (Scotland) Bill (in private): The Committee considered and agreed a revised draft Stage 1 report.

Annex B - Evidence

Written evidence

HS/S5/18/HTAS/01 Professor Steven D Heys, University of Aberdeen

HS/S5/18/HTAS/03 Dr Iain Lang, Clinical Lead Organ Donation, NHS Lanarkshire

HS/S5/18/HTAS/04 South Lanarkshire Health and Social Care Partnership

HS/S5/18/HTAS/05 Scottish National Blood Transfusion Service

HS/S5/18/HTAS/07 The Mission Board of the General Synod of the Scottish Episcopal Church

HS/S5/18/HTAS/17 The Catholic Parliamentary Office of the Bishops' Conference of Scotland

HS/S5/18/HTAS/21 Glasgow City Health and Social Care Partnership

HS/S5/18/HTAS/24 Mason Institute for Medicine, Life Sciences and the Law , University of Edinburgh

HS/S5/18/HTAS/32 Church of Scotland Church and Society Council

HS/S5/18/HTAS/33 Society for the Protection of Unborn Children (SPUC) Scotland

HS/S5/18/HTAS/35 Dr Frank Atherton, Chief Medical Officer for Wales, Welsh Government

HS/S5/18/HTAS/36 Professor David Albert Jones, Anscombe Bioethics Centre

Additional written evidence

Official Reports of Meetings

Tuesday 6 November 2018 - evidence from stakeholders

Tuesday 13 November 2018 - evidence from stakeholders

Tuesday 20 November 2018 - evidence from stakeholders

Tuesday 27 November 2018 - evidence from stakeholders and then from the Scottish Government