Finance and Public Administration Committee

Report on the Cost-effectiveness of Scottish Public Inquiries

Introduction

Statutory public inquiries are a powerful mechanism of accountability within Scotland and the UK. Established under statute, with the power to compel evidence, they investigate issues of major public concern, often triggered by disasters, systemic failures, or issues that can erode public trust.

This is the first time that a Scottish Parliament Committee has examined this matter in depth. Our scrutiny aims to foster a greater understanding of the current position with public inquiries in Scotland, including their number, timescales, extensions to terms of reference, costs, categories of spend and outstanding recommendations. The full remit can be found in Annexe A.

We launched a call for views which ran from 4 April to 9 May 2025. Fifteen submissions were received and are available on the Committee’s webpages. In addition, six written submissions were received after the call for views closed. A summary of responses has also been published1. In total we held ten oral evidence sessions, as well as two informal engagement sessions. These informal sessions provided an opportunity to hear from people with lived experience of public inquiries and to explore the practical experiences of civil servants and public inquiry staff. We thank all those who provided evidence, which has helped shape our conclusions and recommendations found at the end of this report.

On 22 April 2025, the Committee wrote to the Scottish Government2 to ask for baseline information on Scottish statutory public inquiries held under The Inquiries Act 2005 (the “2005 Act”) and the subsequent Inquiries (Scotland) Rules 2007 (the “2007 Rules”).

This information has shown that over the past 18 years, Scottish Ministers have commissioned 11 statutory public inquiries, spanning issues, from the ICL Stockline gas explosion in Glasgow, to a major transport project in Edinburgh, as well as several investigations into health and criminal justice matters. This reflects the breadth and gravity of the matters that the Scottish Government has decided warrant investigation by a statutory public inquiry.

Some inquiries have been conducted jointly with the UK Government, such as the ICL Stockline gas explosion, underscoring the relevance to UK responsibilities and policies and to those directly affected in Scotland. In some other cases, Scotland has pursued its own inquiries on subjects also examined at the UK level, most notably the Penrose Inquiry (contaminated blood) and the Scottish Covid-19 inquiry.

There are currently six public inquiries examining issues of public concern. Two of these have been recently instigated (Eljamel and Emma Caldwell) and calls have been made for more during the course of our investigation. Our report explores the possible drivers of this increased demand.

What is evident from this early information provided is that the cost of public inquiries can spiral quickly, particularly as inquiries can last for many years. Of the current six inquiries, four have been running for over four years, with the Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry ongoing for 10 years.

The SPICe briefing and updated cost table shows that in September 2025, the total ‘direct’ cost of statutory public inquiries since 2007 was £258.8 million, this is an almost £30 million increase since the Committee started tracking public inquiry costs from December 2024.

Background

Unless otherwise specified, references in this report to public inquiries should be taken to be references to public inquires established under the 2005 Act and operated in accordance with the 2007 Rules. This is the scope of our scrutiny.

UK statutory inquiries have separate rules, The Inquiry Rules 2006, which apply to inquiries established by UK Government Ministers. There are small differences to the 2007 Rules, these relate to legal representation, written statements, and some records management provisions.

There are other types of statutory inquiries, for example, in the case of fatalities, a mandatory Fatal Accident Inquiry (FAI) is required in certain circumstances under the Fatal Accidents and Sudden Deaths etc. (Scotland) Act 2016. Some evidence has suggested that aspects of the FAI process could be replicated for public inquiries held under the 2005 Act, to improve their efficiency and cost-effectiveness.

Public inquiries are independent entities set up and funded by the Scottish Government to investigate serious matters of public concern, specifically:

particular events that have caused, or are capable of causing, public concern, or

there is public concern that particular events may have occurred.

There is no duty on Ministers to establish a statutory public inquiry under the 2005 Act.

The purpose of a public inquiry is not to determine civil or criminal liability.

There are alternatives to a public inquiry. The Scottish Government has the option to hold, for example, a discretionary FAI or a non-statutory review depending on its consideration of the circumstances. The Scottish Government can also carry out an investigation or commission an independent review.

The key difference between a public inquiry under the 2005 Act and a non-statutory inquiry is that the chair of a public inquiry has the power to compel the production of documents. A public inquiry is independent of government. This is of particular importance in those public inquiries where the government's own actions are being investigated.

Scottish Ministers appoint a chair, and any panel members. The chair is supported by an inquiry team which would ordinarily comprise counsel to the inquiry. Counsel to the inquiry is responsible for providing legal advice to the chair (and the inquiry) and, if the inquiry holds hearings, would cross-examine witnesses on behalf of the inquiry. There would also be a solicitor to the inquiry who would for example, assist with drafting inquiry protocols and statements of approach, liaise with core participants (see paragraph 21 below) and assist counsel in preparing for oral hearings and with legal advice to the chair.

There will usually be a secretary (sometimes referred to as “chief executive”) to the inquiry, who will administer the inquiry, managing its budget and progress. This is typically a civil servant who is seconded or on loan from the ‘sponsor department’ but who would work independently for the inquiry.

The sponsoring department in the Scottish Government has responsibility for funding and monitoring the budget of the inquiry, in liaison with the inquiry itself.

Core participants are people with a direct interest in a statutory inquiry, who have special rights in the inquiry process. Core participants can include victims and their families as well as ministers and government officials. Interested parties can apply for core participant status and, under Rule 4 of the Rules 2007, it is for the chair to decide who to designate as a core participant.

Public inquiries are expected to report on their findings and make recommendations for improvement.

The Scottish Government has produced guidance comprising of three documents—

Relevant UK House of Lords Reports

The UK House of Lords published two reports on the operation of the 2005 Act. The first report, The Inquiries Act 2005: Post-legislative scrutiny, was published on 11 March 2014 (the “2014 Report”) and considered “the law and practice relating to inquiries into matters of public concern, in particular the Inquiries Act 2005”.

A further report on “the efficacy of the law and practice relating to statutory inquiries under the Inquiries Act 2005”, was published by the House of Lords Statutory Inquiries Committee on 16 September 2024 (the “2024 Report”1). As well as making several new recommendations, the 2024 report also followed up on some of the recommendations made in the 2014 report.

The UK Government’s response to the 2024 Report was issued on 10 February 2025. In that response, the UK Government recognised that “there is serious and growing criticism of their cost, duration and effectiveness” and agreed that the “wider governance structure of public inquiries must be improved”. Specifically, the UK Government has said it will “examine whether there are further changes that could enable inquiries (whether statutory or not) to deliver outcomes for those directly affected and enable lessons to be learnt more swiftly and at lower cost, while preserving the vital public trust that has built up since the introduction of the Inquiries Act 2005.”2

When we asked about potential changes to the 2005 Act, the Deputy First Minister confirmed “there is very much an openness to considering the committee’s recommendations and what changes could be made. That is unlikely to happen before dissolution; such consideration will take place in the next session of Parliament. My strong desire is to see that done on a cross-party basis”3.

Establishing a statutory public inquiry

Public preference for statutory public inquiries

In her submission to the Committee, Dr Emma Ireton, Associate Professor of Law at Nottingham Law School, Nottingham Trent University, specialising in public inquiry law and procedure, stated that—

The Scottish public inquiry process plays a vital role in addressing serious matters of public concern. The role of public inquiries is to establish facts, analyse those facts, and publish a report to address a matter of public concern. They scrutinise the actions of those in authority, shine a public light on events, and drive institutional and policy change in ways that other accountability processes cannot.1

Dr Ireton noted that “the Inquiries Act 2005 has been the subject of post-legislative scrutiny by the House of Lords on two occasions, both concluding that it is generally regarded as good legislation and provides a suitable framework for statutory inquiries. It grants powers to compel the giving of evidence. It does not preclude ministers from convening inquiries outside the Act, without those powers (‘non-statutory inquiries’) […] a core strength of the current model is its flexibility”.1

In her submission, Dr Ireton highlighted that statutory inquiries, with their powers of compulsion, are increasingly seen as the ‘gold standard’, with non-statutory inquiries viewed “with suspicion and as an attempt to avoid scrutiny or accountability”1. This view was shared by several witnesses, including the Institute for Government, who added that “this status created high expectations of inquiries, both for those affected and for the wider public”4.

The Committee heard directly from people with lived experience of public inquiries, who told us that inquiries are fundamental to Scottish society. They are seen as the only viable route to change, when issues are not acknowledged by governments or public institutions. A perception of lack of accountability in the public sector appears to have led to an increase in demand for statutory public inquiries, which some people with lived experience told us come “at great personal costs”—

It feels like there is an industry around public inquiries, there’s always another one coming.5

Growing demand for public inquiries

There is currently no central record of all inquiries held. From individual statutory public inquiry websites, it is known that there have been 11 statutory public inquiries held in Scotland since 2007. In response to an FOI request in 2024, the Scottish Government confirmed that since January 2020, “a number of [non-statutory] reviews have been conducted, ranging from small-scale assessments of policy to substantial investigations akin to a public inquiry”, although “these [non-statutory reviews] are not recorded in a form that would allow us to collate them”1.

John Sturrock KC attributed the growing demand for public inquiries to—

a general move towards “an even greater culture of blame seeking and fault finding”

“an increasing loss of trust in public institutions, which the evidence suggests is manifest”

“a lack of understanding of the purpose and nature of public inquiries, perhaps not least among those who commission them”

a perception of inquiries as “an easy and reflexive way of dealing with a difficult problem”.2

Professor Sandy Cameron CBE, chair of the Centre for Youth and Criminal Justice at Strathclyde University and former Panel member for the Independent Jersey Care Inquiry, noted that public inquiries have “almost become the automatic response to an issue”3. He explained that, when issues arise, “people say, ‘We need a public inquiry’—which, often, becomes a demand for a judge-led inquiry—instead of their saying, ‘Yes, we need to find out what went wrong, but is there another way to do that?’ Often, because these things happen a long time after the event, it can take a long time to argue that corner. Public authorities need to be open about the issues that they have got wrong and they need to be able to say so.”3

The evidence we received suggests that victims do not feel that there is sufficient accountability in public authorities. This lack of trust and dissatisfaction is correlated with an increase in the public’s expectation of public services. The Scottish Police Federation (SPF) pointed to “dissatisfaction among the public about the services that they are receiving. In the case of the police, for example, people are not receiving what they should be receiving from the police service.”5 The Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service (COPFS) agreed that public demands of public organisations have increased and, “to a large extent, that is right”5. While NHS National Services Scotland (NHS NSS) noted that “people are generally much better informed about what they should and can expect. They are, quite rightly, more demanding of the public service […] and perhaps more aware of what the right thing to do is and what their rights are, and they are much better organised.”7

The apparent increase in public inquiries is not solely linked to growing public demand, but also to ministerial decision-making. Some of the participants to the Committee’s engagement event on 7 October stated that public bodies may have an interest in an inquiry not taking place8. It was also suggested that establishing a statutory public inquiry may be used by governments as a way of avoiding responsibility or postponing dealing with a particular issue. As noted by Patrick McGuire of Thompsons Solicitors, “A minister may set up an inquiry cynically, for politically expedient reasons [...] That is where the issue lies. Should they be able to do that?”9

This view was echoed by Professor Cameron, who noted there is a public suspicion around government motivation for public inquiries. He explained that “Once an inquiry has been announced, it allows central or local government to say, ‘I cannot say anything about that, because it is the subject of an inquiry.’ If that inquiry goes on for years, it moves the matter away altogether. […] That is where you must be sure that whatever process is followed is seen to be credible and to have integrity, so that the public can have faith in the expertise and integrity of the people leading it.”3

This suggestion was rejected by the Deputy First Minister, who noted that the subjects of most public inquiries are historical matters. On the reason for growth in the number of public inquiries more generally, the Deputy First Minister commented that this relates to “a lack of knowledge of and confidence in the alternatives”11.

Decision to establish a statutory public inquiry

The Institute for Government noted that—

There are multiple reasons why there is a lot of public and political pressure to hold a public inquiry […] One problem is the lack of guidance and instructions to support ministers to choose the right option. […] If there is a better process for that early decision making in which a minister can more transparently get across the justification and the narrative for the inquiry and exactly what it is meant to do, it is easier to make a case for changing the terms of reference later on, as and when new information comes to light, because that process is clearer.1

According to the Scottish Government Guidance for Ministers and officials on whether an inquiry should be established, the following factors are to be considered in deciding whether to hold an inquiry, and whether this should be statutory or otherwise—

the likely duration and cost;

whether it will need to compel witnesses and the release of documents;

whether it will need witnesses to give evidence on oath;

whether Ministers will need to exclude documents or require evidence;

gathering sessions to be in private (for example, for national security reasons);

the level of formality that is needed; and

whether a particular type of inquiry is likely to satisfy those affected by the issues in question.2

The guidance clarifies there is no duty on Ministers to establish an inquiry on any specific issue, “simply because there are requests for an inquiry”, however, “there may be a duty on the State to conduct an effective investigation or inquiry under one of the articles of the European Convention on Human Rights”2. The decision to hold or not hold a statutory inquiry can be challenged legally through judicial review.

Once a decision has been made to establish a statutory inquiry, under section 6 of the Inquiries Act 2005, a Minister must make a statement to the relevant devolved legislature “as soon as is reasonably practicable”4. The statement must include the name of the chair and members of the inquiry panel (if any) as well as the inquiry’s terms of reference.

The Deputy First Minister emphasised, during evidence, that “Decisions to hold public inquiries are never taken lightly. We always consider alternatives, such as non-statutory reviews, independent panels or other mechanisms that might be quicker, more flexible and less costly. Those options are then carefully assessed [...] and as part of that we try to engage directly with affected parties.”5

It was further explained by Scottish Government officials that these are normally cabinet decisions, and follow consultation with the Lord Advocate, relevant portfolio Minister, Permanent Secretary and the Executive Team at a minimum. Ministers receive advice on different forms of inquiry and their implications, including in terms of costs, time and impact on authorities. However, by the time advice is given, “there is usually a lot of momentum and intense campaigning for a public inquiry”.6

Campaigning for public inquiries often sees the involvement of lawyers and the media. Patrick McGuire explained Thompsons Solicitors’ approach to campaigning, which involves engagement with individual MSPs, who can ask questions in the Chamber, or with the Citizen Participation and Public Petitions Committee. He noted, however, that “Ultimately, and inevitably, that type of campaigning has led to press interest, and it would be foolish not to utilise that as part of the campaign to hold a public inquiry”7. He added, “it is surely up to the Minister who decides to determine whether the case has been made, if the campaign groups have made their best fist of it”.7

The Committee explored the potential for conflicts of interest to arise during such campaigns, particularly where they are carried out directly through the media. We also discussed the potential for conflict of interests’ issues to arise around calls to amend terms of references (ToRs). A theoretical example was put to witnesses where a legal firm, with a potential pecuniary interest in an inquiry, made representations through the media for an inquiry’s ToR to be extended.

It was noted that conflicts of interest may apply to both campaigners and Ministers. With regard to lawyers campaigning for the establishment (or extension) of public inquiries through the media, the Law Society of Scotland said it was not clear whether such campaigning would simply be a case of lawyers exercising their freedom of speech, while highlighting existing requirements to declare lobbying activity9. Compass Chambers argued that there is no relevant conflict of interests if lawyers are advancing their clients’ position9. Thompsons Solicitors stated that such situations would not represent a breach of the Law Society of Scotland rules7.

Thompsons Solicitors highlighted that Ministers would be subject to the ministerial code of conduct in relation to Ministerial decisions on whether to establish public inquiries.7 The Committee wrote to the Deputy First Minister to seek further information regarding Ministerial declarations13. Her reply set out the following obligations―

It is the personal responsibility of each Minister to decide whether and what action is needed to avoid a conflict or the perception of a conflict, taking account of advice received from the Permanent Secretary and the Cabinet Secretariat. [...] Where there is doubt, it will almost always be better to relinquish or dispose of the interest in question.14

Lord Hardie noted that “There is not always an actual conflict, but there can be a perception”9. He argued that setting up a public inquiries unit within the justice department of the Scottish Government would help remove such a perception.

As explained in the House of Commons research briefing on public inquiries16, a Minister must be able to show that it was reasonable to establish a statutory inquiry bearing in mind the nature of the issue being investigated and level of public concern in relation to that issue. A Minister should also be able to show that they did not take irrelevant factors into account when deciding to hold a statutory inquiry.

On the potential for conflicts of interest arising later in a public inquiry, the Deputy First Minister referred to her decision to reject the recent request to extend the ToR of the Sheku Bayoh Inquiry—

I encourage the Committee to look at that recent example and take some confidence from the process that we undertook and our decision, despite there being very conflicting views in the public domain as to whether we should or should not extend the terms of reference. We followed our process and I am confident in the decision that we came to.5

She stressed, “I have to make decisions on the basis of the evidence that is before me and the advice that my officials give me, and on the basis of engagement”.5

Some witnesses called for clearer criteria to be set for Ministers to follow when considering the establishment of statutory public inquiries, though it was highlighted that this would remove the current flexibility afforded to Ministers. Flexibility was highlighted by Dr Ireton as “a core strength of the current model”19.

As noted by John Campbell KC, any such criteria “would necessarily be somewhat nebulous”20. The Faculty of Advocates noted that setting a threshold for the triggering of a public inquiry is challenging due to the same public distrust that leads to calls for an inquiry in the first place— “There is a significant presentational problem in that regard”9. John Sturrock KC explained that—

There should certainly be a rationale for a public inquiry and an understanding of the purpose of that inquiry and of why it is necessary in that particular situation. A more articulate set of criteria could perhaps be applied. I do not know whether that exists now, but what we are craving is explanation, clarity and an understanding of why certain things are, or are not, being done. There seems to be a bit of a vacuum, in a number of respects, in the context of public inquiries in this country.20

It was highlighted by the Law Society that there is a need for better guidance for Ministers’ exercising their discretion to commission an inquiry, not only to enhance transparency around the decision-making process, but also to ensure that decisions are made in a consistent and considered manner, regardless of ministerial turnover9.

Thompsons Solicitors and the Law Society also suggested that Ministers should be required to set out in writing their decision and motivation to not hold a specific public inquiry, to bring more openness to the process. It was noted, however, that the build-up to establishing a public inquiry is already under significant scrutiny, and such issues are normally addressed in Parliament via Members’ business debates7.

Purpose and suitability of inquiries

Before deciding to hold a public inquiry, Scottish Government guidance asks Ministers to consider, alongside length, costs, and legal powers, matters such as—

Are the events of the case in question giving rise to serious and widespread public concern? Is that concern justified?

Is it likely that a public inquiry, its report and recommendations, will satisfy that public concern?

Are there any other forms of inquiry or investigation under way, or expected, which are likely to address or satisfy the same public concerns?1

The guidance does not consider the categorisation of different types of statutory inquiries by purpose.

In her submission to the Committee, Dr Ireton categorised inquiries into three types of ‘core’ purpose, with many inquiries taking a hybrid form, requiring different approaches across different tasks or phases:

(a) policy inquiries (macro/thematic) - Focus on systemic, administrative and regulatory failures (the failings in the ‘checks and balances’) and making recommendations to inform policy reform,

(b) forensic inquiries (incident-specific) - Examine specific events in detail to determine what went wrong and how, and are often required to make recommendations to prevent recurrence, and

(c) truth-telling inquiries - Less common. Focus on public acknowledgement of past harms, promoting understanding and creating or correcting the historical record. Recommendations may not be required.2

The Faculty of Advocates also divided inquiries “into those which relate to a specific incident or incidents (such as the Piper Alpha explosion, the shootings in Dunblane and the activities of Professor El Jamel) and those which relate to how a negative or harmful state of affairs arose and/or was handled by individuals and bodies with relevant responsibilities (the Edinburgh trams project, the Covid-19 Inquiries).”3 Others described two main categories: “a bricks and mortar” inquiry, requiring a more audit like approach, and “service delivery failure” inquiries, requiring a more forensic approach.

Thompsons Solicitors questioned whether “bricks and mortar” inquiries, such as on the Edinburgh trams project or on the Scottish Parliament building, should ever have been established. Patrick McGuire argued that inquiries should only be set up where “there is a real lack of public confidence and there are real victims and real wrongs”4.

Dr Ireton explained that there is currently poor public understanding around the focus and purpose of a public inquiry—

The focus that I am talking about is not theoretical; it is used in other jurisdictions and it works. […] For various reasons, our focuses have drifted and we have allowed expectations of inquiries to become huge—that is, it is expected that they will deliver everything and that, when everything else has failed, an inquiry will come in and solve it all. However, a public inquiry is not the solution to something; it is convened to inform the Government in addressing a matter of public concern. There is poor understanding in that respect.5

Dr Ireton particularly highlighted discrepancies between some inquiries’ terms of reference, which may focus on policy changes, and the political and media narrative around them, which promises justice to victims, therefore setting expectations for full forensic inquiries instead. She argued that decisions have to be made early on by Ministers on the category and purpose of an inquiry, considering public benefit and acknowledging that not all parties will be satisfied with the decision. Dr Ireton provided the examples of Australia and New Zealand, where such an approach has been successfully employed.

She further argued that—

Public statements promising an inquiry will ‘leave no stone unturned’ or deliver justice and individual accountability ‘where other processes have failed’ are unhelpful and risk misrepresenting an inquiry’s remit and terms of reference. Media coverage, statements by the minister, and advice from participants’ legal representative can create or reinforce unrealistic expectations, even where an inquiry itself has made a very clear statement of its purpose.5

Clarity of purpose and expectation management were also highlighted by others, including Professor Cameron, NHS NSS, John Sturrock KC, and Gillian Mawdsley, a practising Scottish qualified solicitor and author of 'Sudden Deaths and Fatal Accident Inquiries in Scotland: Law, Policy and Practice' (Bloomsbury, 2023), who stressed that “recognition that the inquiry is not going to be a panacea for all wrongs is vital”7.

Discussions with witnesses revealed that there is a general public misconception that public inquiries will apportion blame, despite Scottish Government guidance clearly stating, “it is not the purpose of a public inquiry to determine civil or criminal liability. Rather inquiries can investigate issues and make findings and recommendations.”1 John Sturrock KC suggested there is a need for education about “what public inquiries are intended to do and to be […] they are designed to find out what happened and why, what could have been done differently and, very importantly, what can be done differently in the future”9. He added, they are not designed to find fault.

Building up the alternative

According to Cabinet Office guidance, inquiries should only be considered “where other available investigatory mechanisms would not be sufficient”1. An overview of other mechanisms available to Scottish Ministers is provided in the Scottish Government guidance, and includes Fatal Accident Inquiries (FAIs), inquiries under other legislation, non-statutory inquiries, non-statutory committees or commissions, royal commissions, independent reviews with a public hearing element, regulatory investigations, police investigations and truth and reconciliation commissions.

During evidence, we heard examples of non-statutory inquiries that were delivered expediently and at a fraction of the cost of statutory public inquiries, including the review into bullying and harassment in NHS Highland and the Bonomy Report of the Infant Cremation Commission.

As discussed earlier in this report, the appeal of statutory inquiries lies in their independence and power to compel. The Scottish Government guidance notes that independence can also apply to non-statutory inquiries, but stresses that “establishing a 2005 Act inquiry can put it beyond doubt”2.

Our engagement with civil servants revealed that the Scottish Government’s starting point is to not launch a statutory public inquiry, and that alternatives are generally considered first and explored exhaustively before an inquiry is launched. This includes engagement with those affected and discussions around the considerable length and cost of public inquiries.3

People with lived experience also told us that public inquiries should be “the final option”4. They highlighted a need for “other options first”, for organisations to be open and transparent and, in some cases, a need for regulators. One of the participants at the Committee’s engagement event on 7 October recounted that they would have preferred a court process, but this was not possible due to financial risks. Even though they had counsel who was willing to take the case pro bono, they were advised they would need several hundred thousand pounds to cover the Government’s costs if a judicial review did not find in the participant’s favour4. Other witnesses pointed to the need to build the public’s confidence in the alternatives, in their value and credibility.

We heard that, in some cases, non-statutory alternatives were tried, but they failed to remove the appetite for a public inquiry, or to obtain the evidence requested, in the absence of statutory powers. The Edinburgh Tram inquiry started out as a non-statutory inquiry and its former chair, the Rt. Hon. Lord Hardie, explained that he was restricted by the inability to command evidence, both from commercial firms, and from the City of Edinburgh Council, due to data protection legislation: “The only way around that was to have statutory powers to require the City of Edinburgh Council to give me the data about former employees, whom the inquiry could then pursue and interview. Even when we had that power, it was sometimes quite difficult to get hold of them.”6

The COPFS, on the other hand, stated that assistance to an inquiry is not always provided “because it has the force of law and can compel evidence from us; we do so because we welcome the transparency and accountability that inquiries bring”, while noting that some inquiries “involve balancing other rights, so powers of compulsion might be required”7.

Dr Ireton explained that having statutory powers and the power to compel are important for public inquiries, particularly in terms of public perception. She stated that it is often sufficient for those powers to be available to an inquiry, even if they are rarely used, while noting that such powers may not always be appropriate6.

A duty of candour may be a way of addressing some of these issues. The Public Office (Accountability) Bill, which was introduced by the UK Government in the House of Commons on 16 September 2025, includes, amongst others, provisions for a “duty of candour and assistance” (a legal obligation to act transparently) for public authorities and officials when engaging with inquiries, inquests and similar investigations. The Bill also aims to—

create a framework to ensure ethical conduct in public authorities including mandatory codes of conduct,

create new criminal offences of failing to uphold the duty of candour and assistance and misleading the public,

create two new statutory offences to replace the common law offence of misconduct in public office, and

introduce “parity of representation” for bereaved families at inquests involving public authorities.”

Speaking to the Bill, the Deputy First Minister stated that “The reforms aim to ensure that inquiries, whether statutory or non-statutory, are supported by clear duties on public bodies to provide full and accurate information, while giving chairs additional powers to compel evidence and enforce candour without the need for a full statutory process. That could make non-statutory inquiries a more viable and cost-effective option in some cases.”9 She added that the Scottish Government is working constructively with the UK Government on the Bill. The Committee will consider a Legislative Consent Memorandum on the Bill in the coming weeks.

Public inquiries are an essential mechanism for holding public bodies to account, reviewing past wrongs, identifying solutions and recommending changes to policy. The Scottish public inquiry system, however, is overstretched and poorly defined. It aims to cover forensic investigations, policy reform, and truth-telling, without a clear separation or definition of a ‘core’ objective.

While we acknowledge that each inquiry is unique, the current one-size-fits-all approach is no longer appropriate. Our evidence shows that inquiries would benefit from setting a clearer ‘core’ purpose at the point of establishment. We therefore ask that the Scottish Government updates its guidance to reflect the ‘core’ purpose, scope and limitations of public inquiries.

Alongside this, we recommend that the Scottish Government sets up a dedicated webpage with clear information on the establishment of public inquiries, their role, the different categories of ‘core’ purpose and limitations. This information should be clear and easily accessible to the public, including anyone campaigning for a public inquiry, to manage public expectations around their purpose.

There remains a lack of clarity and openness around the decision-making process leading up to the announcement of a public inquiry. We seek further development of the Scottish Government guidance for Ministers, to provide a clear framework for decision-making and bring much needed transparency and consistency to the process. This should include a clear requirement for a statutory public inquiry to be considered only when all alternatives have been exhausted.

The Committee notes the issues about potential conflicts of interest when establishing public inquiries or amending their Terms of Reference. To safeguard independence and public trust, we recommend that the Scottish Government publishes comprehensive guidance covering all aspects of potential conflicts of interest. The updated guidance should set out clear expectations for the conduct and actions of Ministers, inquiry chairs, inquiry staff, legal professionals, and sponsoring department staff.

The Committee believes that all statements to Parliament announcing the setting up of a public inquiry should fully explain Ministers’ decisions and the reasoning for launching a public inquiry, including the factors that were taken into account in the decision-making process and the alternatives considered.

During this statement, the relevant Minister should also declare any personal or professional relationships pertaining to the inquiry.

Delivering public inquiries

Appointment of chairs

Under section 3 of the 2005 Act1, the Minister who has set up the inquiry is also responsible for appointing the chair and the members of the panel (if any). An inquiry can be undertaken by a chair sitting alone or with an inquiry panel.

All Scottish public inquiries have been chaired by a current or retired judge (the Child Abuse Inquiry was initially chaired by a QC but then replaced by a judge).

There were a variety of views provided on the appointment of chairs, their skill set, and on the appointment of judges as chairs.

Professor Cameron shared his experience as a panel member on the Independent Jersey Care Inquiry (IJCI). He told the Committee that the IJCI was chaired by a defence barrister who also had experience of sitting as a judge, assisted by a panel of two with a social work background, including him. He also highlighted the UK inquiry into child sexual abuse, which had been chaired by a social work professional, as a further example of a non-judge led inquiry, stating “they will bring a different perspective”2.

Some participants with lived experience, who attended the Committee’s informal engagement session, regarded the use of a panel of experts as positive and a better alternative to groups of lawyers having to get acquainted with very specialised information (for example, the requirements of hospital ventilation)3.

Professor Cameron told the Committee “there is now a public—or media—perception in Scotland that an inquiry should be judge led”2. When we explored further whether a judge needs to be in the chair due to their experience of using powers to compel evidence, Professor Cameron acknowledged there needs to be some legal involvement in the process, “but that does not mean that a judge needs to chair the inquiry”2.

Wendy McGuinness, who is an expert in New Zealand inquiries, considered that inquiries do not need to be judge-led as you can “train people to chair processes”6. She referred to training undertaken in New Zealand by the Institute of Directors as an example of what training might be available in Scotland.

Others felt there are benefits to judges being chairs, particularly those from the legal profession, but not exclusively. For example, the COPFS said “judges tend to be chosen because […] they are seen as independent, and […] have a background in ensuring fairness and in making and writing up complex decisions”7.

John Sturrock KC suggested what should be considered is whether chairs have the “skills and competencies that are required to run an effective public inquiry in the modern era, with all that that entails”8. In his written submission, he listed some of these skills: subject-matter expertise; ability to cut through detail and identify key points; delegation; management of time; facilitation or inquisitorial skills; the ability to draw out the real underlying issues, key differences and common ground quickly, in a non-confrontational environment9.

Dr Ireton suggested the decision on whether to appoint a judge should be more aligned to the ‘core’ purpose of the inquiry, saying “a more forensic inquiry or a huge volume of information […] plays to the skill set that judges have […]. If the inquiry is more policy focused, it will often be better to have an expert in the subject matter and the implementation of policy changes”10.

Thompsons Solicitors felt that where there are groups of victims involved in a public inquiry these should be judge-led, unlike ‘bricks-and-mortar-inquiries’ (e.g. the Edinburgh Tram type of inquiry)11.

There was broad agreement around whomever is appointed as chair, they should command public confidence. Professor Cameron summed this up when he said, it is important that “whatever process is followed is seen to be credible and to have integrity, so that the public can have faith in the expertise and integrity of the people leading it”2.

International evidence suggests non-judge led inquiry models can be just as credible and effective. Under the Swedish model, public inquiries are not judge led, and do not have power of compulsion13. We heard from Professor Carl Dählstrom, professor of political science at the University of Gothenburg, that “people generally bear witness and that they feel the pressure to do so. That is how it generally works.”6

Impact of appointing a serving judge

The Scottish Government guidance states—

In most inquiries the chair will be legally qualified, often a retired judge, however this is not always appropriate and very much depends on the circumstances of the particular inquiry.1

It goes on to provide a list of questions for Scottish Minister to consider, including—

If it is proposed to appoint a judge or legal officer (e.g., a Scottish Law Commissioner) to a public inquiry, has the Lord Advocate been consultedi

If the inquiry chair is to be a serving judge, sheriff principal, sheriff, or summary sheriff, has the Lord President been consulted on their appointment?

If requested by Scottish Ministers, the Lord President will invite expressions of interest from serving and retired judges. The decision to accept an appointment as chair is for the individual judge themselves.

Both Lord Pentland, the Lord President, and Lord Carloway, the former Lord President, explained in their letters to the Committee the impact on judicial resources of appointing serving judges. The Lord President stated—

If the judge is a senior judge – i.e. a judge of the Court of Session and High Court of Justiciary - then there are only 36 of those in the country, due to a statutory cap on numbers. In a typical year, such a judge would sit for 205 days. That translates to approximately 34 criminal trials. There are currently three serving senior judges chairing public inquiries. That amounts to nearly 10% of the sitting days available to deal with civil and criminal cases of the more serious kind; cases which the public has every right to expect will be dealt with reasonably promptly.2

By way of comparison, we note that in Australia, royal commissions are usually chaired by a former judge. Sitting judges tend not to be appointed to such commissions as they would have to stand down from judicial office3.

The Deputy First Minister said, “I often hear demands for a judge from those who are supportive of an inquiry being established”, but she stressed there is no requirement for the proposed chair to be a judge. When pressed by the Committee as to why judges have been chosen for all Scottish inquiries, she confirmed she is “open to non-judge-led public inquiries” and is conscious of “just how extensive the workload on judges is”. She considered “belief that only a judge can bring gravity to the situation” in her view to be “slightly flawed”4.

It was put to the Deputy First Minister that continuing to appoint judges, reinforces the view that is conveyed to the public by the media and others that only a judge-led inquiry is valid, an approach that can be more expensive and time consuming. In response, the Deputy First Minister argued “that there are certainly inquiries that have benefited from being judge led. I have no current plans to establish another inquiry”4.

The Committee is concerned that appointing serving judges to chair public inquiries places significant strain on Scotland’s civil and criminal courts, a pressure amplified by long-running inquiries. Evidence shows that trusted policy experts have successfully chaired inquiries in the UK and internationally. We welcome the Deputy First Minister’s openness to appointing expert chairs, however we are disappointed that in practice the Scottish Government has failed to appoint any non-judge chairs.

The Committee recognises the need for flexibility under the Inquiries Act 2005 when appointing chairs, given the varied purposes of public inquiries. We recommend that the Scottish Government strengthen its guidance to ensure all options: legal chairs, expert chairs, and expert panels are actively considered and aligned to the inquiry’s ‘core’ purpose. Guidance should set out successful examples of each approach, including the relevant chair skillset and related best practice. Officials must provide robust, detailed advice to support Ministers in making these appointments.

The Committee notes that guidance refers to consulting with the Lord Advocate and the Lord President where ‘legal’ appointments are being considered. The Committee recommends the Scottish Government guidance factors in the implications for judicial resources at an early stage, so this can be incorporated into the advice provided by officials.

The Committee recommends that all future Scottish Government statements announcing a public inquiry, under section 6 of the Inquiries 2005 Act, clearly set out the decision to appoint the chair (and any panel), the reasoning behind that choice, including the chair’s skillset, and the alternatives evaluated.

Drafting and agreeing the Terms of Reference

Under section 5 of the Act1, the Minister who has set up the inquiry is also responsible for setting the terms of reference (ToR). Scottish Government guidance states, the “ToR should always make clear:

to whom the inquiry should report;

the purpose of the inquiry; and

whether the inquiry is being invited to review policy in a given area, consider the facts of a particular case, and/or make recommendations.”2

The inquiry chair must be given an opportunity to discuss the proposed ToR with Ministers before it is finalised and published. A ToR must be finalised before an inquiry can start. A public inquiry has no power to act outside its ToR, but the inquiry chair (and panel, if any) are responsible for interpreting the ToR themselves. A public inquiry ToR may be subject to judicial review.

ToRs are not required to include details of likely costs or time deadlines. We understand from the Explanatory Notes accompanying the 2005 Act that in some cases it might be appropriate to specify a date by which the inquiry is asked to report, or the level of urgency3. The duration of inquires is considered below. It is noted that longer inquiries routinely cost more. Detailed consideration of associated costs is set out later under the section on Resourcing public inquiries.

Terms of Reference and a clear purpose

There was general agreement amongst witnesses that the purpose of the inquiry needs to be clear and that this should inform ToRs.

Dr Ireton argued the focus on the ‘core’ purpose of an individual inquiry has been drifting, stating “we have had massive mission creep”. She considered all three types of inquiries “forensic inquiries to understand what went wrong, systemic inquiries to inform policy reform or truth-telling inquiries” are being conflated into single inquiries—

If you are going to have inquiries that take a very forensic approach as well as looking at the systemic macro failings and producing a record of testimonies about what went wrong, you will inevitably have long, expensive inquiries.1

She stressed a “core focus and purpose” should be identified “if you want a cheaper, more efficient, cost-effective inquiry”1.

In terms of drafting ToRs, it was identified that ToRs vary greatly in length and detail and were thought to be getting longer, to which the Faculty of Advocates noted longer ToRs “probably reflects greater specification of the work to be undertaken”3.

The Faculty of Advocates commended the ToRs for the Piper Alpha and the Dunblane shootings Inquiries which had “succinct, general statements of purpose and were not subject to significant cost or overrun.” Though, it was noted that these were “largely pre-internet inquiries” and there was “not nearly so much by way of other regulatory requirement as there is nowadays”1.

On determining a clear approach to drafting ToRs, the Faculty of Advocates stated that “crafting broad terms may be more likely to avoid the need for extension; whilst updating terms of reference may be necessary, ‘too much revision creates a drag on an inquiry’. It is likely that the most effective terms of reference are somewhere between the brief early remits and the opposite exercise of trying to produce an exhaustive list, in advance, of every sub-topic the inquiry may need to examine.”3

There have been different approaches taken to drafting ToRs, for example the Scottish Covid-19 inquiry’s ToR was drafted through public engagement and consultation.

Thompsons Solicitors said there should be liaison between the Minister and the recognised victims while the ToR is in draft form and referred to the strong representations made to the Vale of Leven Inquiry and the Scottish Hospitals Inquiry that victims should be at the heart of those service-failure type of inquiries6.

The 2024 House of Lords Report concluded that “In order for an inquiry to be properly established from the start, its terms of reference must be written carefully in order to give the chair the necessary direction to achieve its aims, recognise the expectations of the public, victims, survivors and other interested parties and to avoid unnecessary cost.”7

The UK Government accepted the House of Lords 2024 Report recommendation that Ministers should meet and consult victims and survivors’ groups before publishing the ToR8.

Many witnesses argued that assessing value and cost-effectiveness should be tied to the specific ToR set for each inquiry. The Law Society stated in its submission that “it is difficult to assess the effectiveness of the current model unless parameters or goals are set in the ToR which provide for a means to make such an assessment”9.

The Deputy First Minister agreed that “the terms of reference are the primary area where a Minister can set the direction of a public inquiry”. She emphasised that—

Once they have established the public inquiry and set the terms of reference, the chair alone is then responsible for deciding how the inquiry should operate. The importance of the terms of reference therefore cannot be overstated, so I agree with you on that.10

Amending Terms of Reference mid-inquiry

There may be times when the ToR set at the beginning of an inquiry need revision.

Dr Ireton stated in her submission that “inquiries are often convened quickly, under significant public and political pressure for action. Insufficient attention to defining their purpose and scope can result in poor management of expectations and pressure to expand remits.1”

When asked about amending ToRs, Lord Hardie explained he did not have direct experience but commented that it is “important to get the terms of reference right at the beginning”. He discussed the practical implications once the ToR is extended—

Does that open the floodgates to another chapter of evidence that has not been anticipated? Do you then send your inquiry team out to see whether there is any further evidence within the extended terms of reference? That would, of course, extend the time taken for the inquiry.2

Laura Dunlop, Faculty of Advocates, recalled two past occasions where a chair requested the ToR be changed, one where something was removed and another which was an expansion—

That was because we realised, as we got deeper into the subject, that we had neglected something. The chairman in the […] Penrose inquiry, had made a lot of contribution to the framing of the terms of reference, but […] there was something that we had all overlooked, because we were all ignorant of the subject matter of the area.2

John Campbell KC said, “it may be not that the terms of reference were not tight enough but that [it needs to be expanded due to something that …] is wholly unexpected”4.

The Deputy First Minister considers the ToRs and scope that are set in her engagement with chairs is clear. She did reflect “however, we perhaps need to be clearer with the public about the purpose. I think that the purpose is very clearly defined in the terms of reference, and most people who are intimately involved in the inquiry will know what it is. If there is a challenge with the wider public, we can always do more to communicate.”5

One of the most effective steps the Scottish Government can take to prevent overly lengthy inquiries is to define a clear ‘core’ purpose, whether forensic, systemic, or truth-telling etc. This would set expectations for the inquiry’s scope, inform the drafting of the Terms of Reference, guide decisions on any extensions, and ensure clarity in Ministerial and inquiry communications.

We recommend the Scottish Government aligns its guidance on ToRs more closely to a public inquiry’s ‘core’ purpose as discussed earlier in this report. The guidance should set out a framework for each ‘core’ purpose option, including an inquiry’s appropriate length and budget.

Retaining institutional knowledge on drafting ToRs is challenging as inquiry subjects, chairs, governments, Ministers, and officials change. Evidence shows that ToRs vary in effectiveness, making it clear that further work is needed to strengthen this process.

The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government undertakes a short, focused research project on best practice for drafting and amending ToRs ahead of the next Parliamentary session. This research should inform detailed guidance aimed at improving transparency and consistency. The research should specifically include drafting measurable aims in ToRs and include any lessons learned on the revision of ToRs mid-inquiry.

Duration of public inquiries

Timescales for inquiries can vary significantly based on the scale of the harm being considered and the scope of the issues. Several factors during the inquiry process can contribute to more lengthy public inquiries.

In his written submission, Lord Gill referred to his experience as Chair of the ‘Stockline’ ICL Inquiry and what he identified as “the general principles of efficiency on which an inquiry should be run”, he stated—

The onus is on the chairman of the inquiry to conduct it with thoroughness and efficiency. In doing so he should be subject to clear and precise terms of reference. The preparation for, and the detailed orders made during, any inquiry vitally affect the length and the public cost of even the simplest inquiries. Treating the inquiry as though it were a full-blown adversarial litigation is not the way forward.1

Dr Ireton agreed with this view, she stated, “improvements in efficiency and in the length of time taken must happen at every step of the inquiry”. She argued that “there must be an induction process for the chair so that they understand the nature of what they have become involved with”2.

Delays between announcement and start of an inquiry

In addition to the time taken to finalise ToRs, the most substantial cause of delay identified by our investigation between the Ministerial announcement to hold an inquiry and the inquiry starting, are the practicalities of setting up an inquiry.

Lord Hardie recounted his experience of setting up the Edinburgh Tram Inquiry—

There was also an expectation that, immediately after that [the Ministerial announcement], I would walk into an office that was fully equipped and fully staffed and start work. I did start work, but the work involved finding an office. When we found an office, it was one that the Government was already paying rent for but was unused. It was in a good location for witnesses because it was near the station, so it seemed ideal. It also had portals in the floor for IT […] so the assumption was that everything was hunky-dory, […]. However, once we got started, it became clear that the IT system did not work. We had to rely on Creative Scotland, which had been the original tenant, to assist us with IT.1

He described his frustration with the experience and commented “what happens each time there is an inquiry is that the chair has to start from scratch. That is a waste of money and also a waste of experience, because the chair—unless he or she has conducted an inquiry previously—will have no experience of setting up an inquiry”1. Other witnesses, like Compass Chambers, also commented on the situation saying it is “certainly suboptimal” and “should be sorted”1.

Scottish Government officials, who participated in the Committee’s informal session, said there is an established practice for running public inquiries. They explained the Scottish Government provides guidance and support at the establishment of a public inquiry, particularly in relation to securing premises and providing IT equipment4.

Procedural delays

Evidence to the Committee highlighted that once an inquiry is up and running one of the main factors that contributes to longer public inquiries is the legalistic and procedural approach taken to the inquiry.

John Sturrock KC reflected that time and cost are inherent in the adversarial system, as it “requires a certain approach to process”. He acknowledged that “in some ways, lawyers who are doing their jobs need to follow it”1.

Rebecca McKee, of the Institute for Government, told the Committee that “public inquiries have become incredibly legalistic in their culture. They have become a lot more like courtrooms”. She noted that this approach has “bled into non-statutory inquiries” too, though they are often seen as a shorter, sharper method. On the reasons for this, she said—

We often look at the high-level, forensic inquiries such as the Covid inquiries as a comparator, but the same legal firms work on both types and they have started to dictate that culture.2

Those legal professionals who had worked as part of a public inquiry team explained that being involved in a lengthy inquiry is very demanding with long working hours. Laura Dunlop, Faculty of Advocates, said of long-running inquiries, it is a “very demanding gig”. She explained—

You are working huge numbers of hours and working every evening. If you are doing hearings, you are working every night. It does not take terribly long before you hope that it will not last too much longer.3

Lord Hardie argued that there are opportunities to manage the legalistic process using the existing 2007 Rules. For example, he issued a notice early in the inquiry he was chairing confirming there would be no opening statements, including by counsel to the inquiry. This enabled the inquiry to go straight to evidence taking. It is noted that the UK 2006 Rules do not give the chair that discretion. He also did not allow cross-examination as he considered that to be an adversarial approach. He stated—

The chair has the power and the ability to control time spent by lawyers on the inquiry, at least in the public hearings.3

Delays associated with warning letters

Under Rule 12 of the 2007 Rules, a procedure that is commonly referred to as Maxwellisation prescribes that the inquiry panel must not include any significant or explicit criticism of a person in the report (and in any interim report) unless that person is given a warning letter; and the person has been given a reasonable opportunity to respond to the warning letter.

Roger Mullin, former MP, stated in his submission that ensuring inquiries’ independence is vital, but it “is being compromised by current processes and in particular, their adoption of the Maxwellisation process”—

My concern about independence is because Maxwellisation allows those being criticised in a report, to see the criticism in full and be able to respond in detail. This immediately means the opportunity to play a part in the final review of a report prior to publication is afforded to those criticised. I became particularly concerned in the wake of the much delayed Chilcot Inquiry where Maxwellisation is estimated to have taken around two years, with no effective limit on how long people were allowed to respond. This, to me compromises the independence of reports, causes significant delays and is therefore costly. It also lacks balance.1

The Faculty of Advocates said it is “puzzled” by the wording of the Rule in that the “criticism can be explicit but still insignificant”2.

Regarding the procedure in practice Lord Hardie, said those criticised “must be given a fair opportunity to respond. You might allow a month, or even two, depending on the extent of the criticism”. He went on to say, “the responses that I got were substantial—one was several hundred pages long”2.

Lord Hardie and Dr Ireton consider that this ‘mandatory’ power should become ‘discretionary’. Dr Ireton added there is confusion about the operation of the powers, which she stressed is why we “need a centre that understands what is going on in different inquiries and shares that learning”2.

Impact of long-running inquiries

Professor Sandy Cameron stressed the importance of public inquiries in “giving a voice to victims/survivors in some cases and in all cases identifying what went wrong and learning lessons”. He reasoned that very lengthy timescales to reach their conclusions may mitigate against that however, stating—

Inquiries which run for many years risk losing public interest and may add pressure to witnesses who are desperate for an outcome. There is also a risk of compassion fatigue for participants.1

Similarly, the Faculty of Advocates outlined—

At the most basic level, people may die, or there may be a loss of faith or trust. It does not seem right to use the expression “sweet spot”, but there must be an optimal point at which an inquiry should finish its report and wind up.2

NHS NSS, which is a core participant in both the Scottish and UK Covid-19 inquiries, noted that with lengthy inquiries core participants are expected to talk about events that happened five years ago3.

To manage long-running inquiries, some have taken a modular approach to their inquiry, such as the Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry and the Scottish Covid-19 Inquiry. This was generally welcomed. NHS NSS said clear timetables for ‘modules’ and detailed ToRs for each module are effective in keeping public inquires to timetable and remit. It also allows core participants to prioritise resources4.

International comparison of Covid-19 inquiries shows that many other countries were able to conclude their inquiries within a two-year period. Looking at the Swedish system, public inquiries are initiated by the Cabinet by issuing a commission directive, which sets out the delivery date and budget for the inquiry. All inquiries are normally completed within two years, with the average length currently at 15 months. Like the Swedish system, New Zealand inquiries have budgets and timeframes set in the terms of reference, which can be extended if needed5.

Dr Ireton suggested there is a strong case for greater use of shorter, focused, statutory inquiries, which deliver thematic learning and policy recommendations within 12 to 24 months. This would allow lessons to be acted on before policy priorities shift, or events recur, but—

You have to make sure that the task that is being set for the inquiry can be done properly, thoroughly and well within the timeframe. That means that, inevitably, you must make the task much smaller and more focused.2

The Institute for Government raised the issue of delays caused by the government or other public bodies involved in the inquiry due to them “not being ready and not having their papers and documentation in order”. Rebecca McKee, said—

Sometimes that has caused big delays, which then creates a very uncomfortable situation when it comes to negotiating with Government on extending timescales, as it might have been the Government that has caused some of the delays […] it can add several months to the length of an inquiry.3

As further explored in the next section of this report, protracted inquiries directly impact on the provision of public services. Evidence received from the Scottish Police Federation and NHS NSS reflects the deflection of human and financial resources into public inquires, often at the expense of public service delivery.

The Committee notes that a duty of candour as currently proposed in UK legislation has the potential to minimise delays to public inquiries caused by public authorities’ lack of readiness to provide documentation.

The Inquiries Act 2005 Explanatory Notes acknowledge that Ministers are free to set a timescale or refer to the urgency of an inquiry. From the evidence we gathered, setting a deadline for an inquiry is not, however, routinely happening. The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government should in future set a defined timescale based on an inquiry’s ‘core’ purpose.

The Committee is concerned about the lack of support for inquiry chairs, particularly as public inquiries have become a more frequent choice for the Scottish Government. It is of concern that chairs sometimes 'reinvent the wheel', undermining efficiency. Many of these challenges could be addressed through proper induction and training, adoption of best practice, and adequate support during the inquiry’s establishment. We explore these issues later in this report.

The procedure of warning letters under Rule 12 of the Inquiries (Scotland) Rules 2007 can cause significant delay. The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government brings forward amending regulations to ensure inquiry chairs can use their discretion to issue warning letters.

Resourcing public inquiries

Costs of a public inquiry

Public inquiries have become expensive exercises. Scottish Government guidance states, that, when considering an inquiry, “Ministers will need to judge whether the circumstances of the matter in question justify the considerable expense”. Costs expected to be incurred include—

“the salary of the chair (unless the chair is a serving judge who remains on their judicial salary) and other members of the panel (if any);

the salaries of the solicitor and secretary (and, if appointed, counsel) to the inquiry;

the salaries of other inquiry support staff, either employed by the inquiry or services bought in (including lawyers);

fees for subject experts;

the expenses of core participants and witnesses, etc. attending the inquiry;

the cost of office accommodation for the inquiry team and accommodation for the public hearings;

IT equipment (including document management and reporting on hearings) and other support services;

website, communications and public relations; and, above all,

the legal costs of the core participants at the inquiry which are always met by the Government unless the core participant is a corporate body”.1

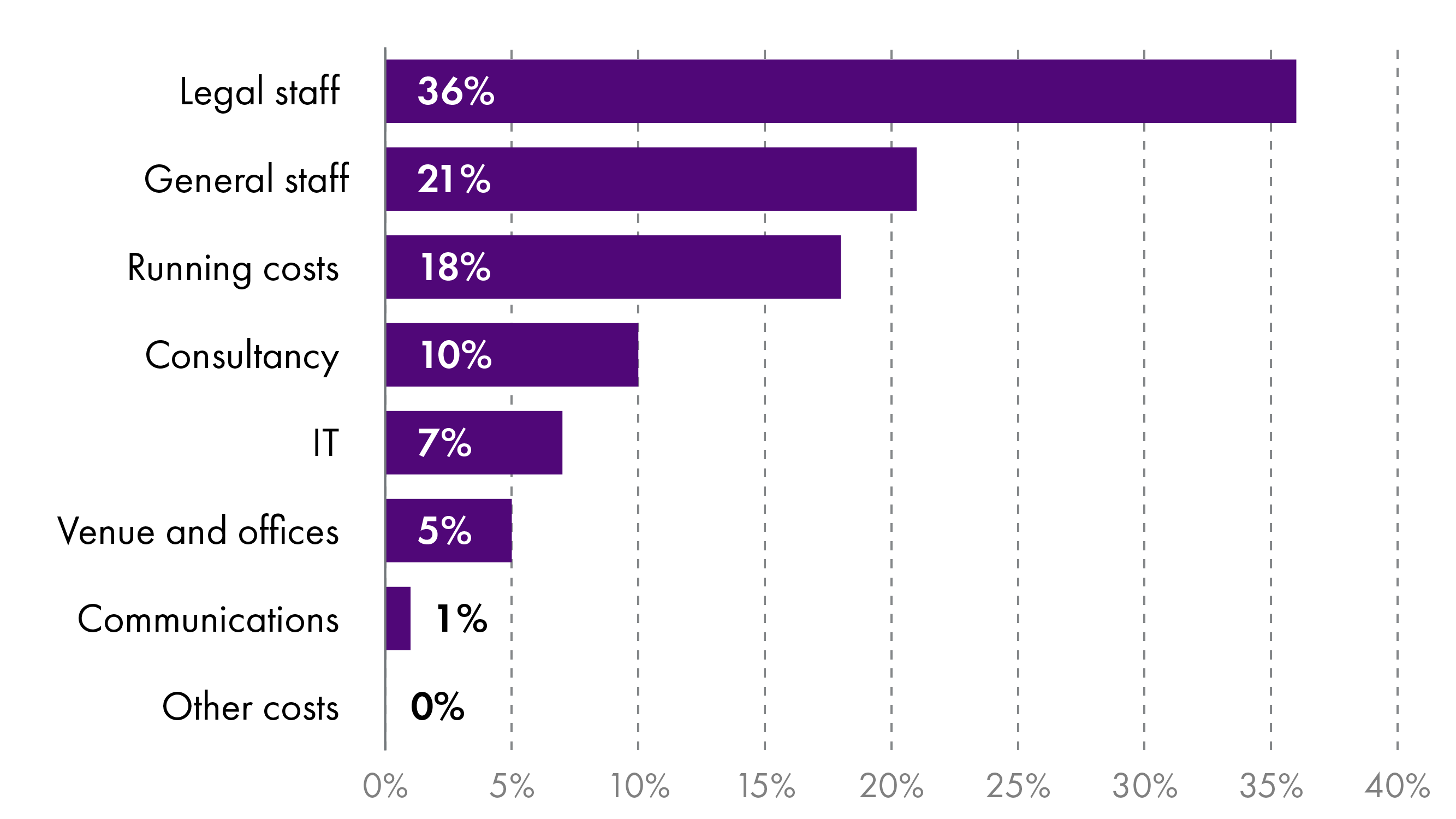

Research by the Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe), shows that the total cost of Scottish public inquiries since 2007, when completed inquiry costs are put into 2024-25 prices, amounts to £258.8 million (Annexe C). The most expensive inquiry so far, the Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry, which started in December 2014, has incurred costs of over £102 million and is still ongoing.

A quick overview of Scottish inquiries’ costs reveals an exponential increase in both costs and timescales. The Faculty of Advocates highlighted that public inquiries are now subject to increasingly higher requirements and, therefore, costs2.

It was generally acknowledged during evidence taking that current inquiry costs are out of control. John Sturrock KC correlated this issue with a generally suboptimal approach to decision-making, complex issues, negotiation and addressing tougher issues: “There is a paradox here: public inquiries are often about those situations, but they reflect the same underlying suboptimal approach that I would identify as being problematic in Scottish decision making.”3

The Committee heard there is limited project management in the delivery of public inquiries. Some witnesses compared this with the business environment or even academia, where such an approach would not be possible or acceptable. Roger Mullin explained, in his submission, that—

inquiries appear to operate on what construction companies would understand as a ‘time-on-line’ contract, where the contractor is paid based on the time spent on the project and the cost of materials used. But where companies would usually have very detailed reporting, negotiating and agreement required as part of such a contract, inquiries lack such rigour. The unintended consequence of this is that individuals and legal firms, paid on the basis of their time involved in an inquiry, have no incentive to be as efficient as possible and indeed will get rewarded from the public purse by maximising their time involved.4

The Law Society, however, argued that “inquiries are not-for-profit bodies. […] Accordingly, they should not be judged on rules which apply to business enterprises.”5 Thompsons Solicitors further argued that costs “cannot […] be diminished in any way, if public inquiries are to achieve what they need to achieve for the victims of mass wrongs.”6

A brief comparison with public inquiries in other countries, however, reveals the magnitude of the problem. Many democracies across the world hold government-initiated, independent investigations into matters of public concern. COVID inquiries/commissions present a unique opportunity for comparison. SPICe research shows that, for example, an Australian Commonwealth inquiry reported in 13 months at a cost of approximately £4 million, the New Zealand Royal Commission (Phases 1 and 2), which is still ongoing, is expected to cost the equivalent of £13 million, while Denmark held an inquiry that reported in seven months and cost £500,000. The Scottish Covid-19 inquiry, by contrast, has so far cost £45.5 million (as of September 2025)7.

This points to the issue discussed earlier in this report regarding clarity around an inquiry’s ‘core’ purpose. As described by Dr Ireton, “We have created a problem that is not seen at the same scale elsewhere”2. There is a need, as the Institute for Government highlighted, “to be clear up front on what the mechanism of an inquiry is for, and that political decision should be made early on, as other places have been able to do.”9

Chairs' duty and discretion in managing costs

An inquiry chair is responsible for both discharging the terms of reference and avoiding unnecessary costs. Terms of reference are not required to include details of likely costs or deadlines. However, under Section 17 of the Inquiries Act 2005, “the chairman must act with fairness and with regard also to the need to avoid any unnecessary cost.”1

Section 40(4) of the 2005 Act permits Scottish Ministers to set additional conditions for the chair when exercising the power to make awards, including in respect of legal representation. The Scottish Government has set such conditions for the Covid-19 inquiry and the Sheku Bayoh inquiry. While “legal costs of participants often constitute the most significant part of the total cost of an inquiry” (Explanatory Notes to the 2005 Act2), a section 40 determination however cannot control overall costs. These remain under the responsibility and discretion of the chair.

Lord Hardie explained the process as starting with discussions between the secretariat and the sponsor department, with an annual budget fixed that is later reviewed during the year. The process is repeated yearly and the budget adjusted, which “has the risk of cost creep unless the department is exercising significant control over the budget and asking the secretariat sufficient questions”3. He added that, in his experience as chair of the Edinburgh Tram Inquiry, he “was not aware of any serious challenge of our budget or of our timescale.”3

During our scrutiny, we explored the tension between the effective running of an independent inquiry and fixing budgets and timescales at the outset. It was noted by Professor Cameron and others that inquiries “can be almost certain” to last longer and cost more than envisaged, and that the system lacks a mechanism for striking a balance between ensuring the independence of inquiries and containing costs5.

John Sturrock KC suggested that Ministers should discuss expected costs with the chairman at the outset of an inquiry, as would be the case in any other public endeavour, “The minister should then expect the figure to go up […and they should] take responsibility for that, because he or she commissioned the inquiry. A chairman can rightly expect the minister to speak up on his or her behalf if cost overruns happen.”6

We heard mixed views on the impact of tight timescales and costs on the independence of the chair. Some witnesses, including the Faculty of Advocates, agreed that a “sort of control at the outset for either cost or budget is indicated”3. Others were more reluctant and argued that setting limits on an inquiry will reduce its independence and affect public confidence. If inquiries are seen to be pressured by Government, victims may feel that justice has not been done. Different approaches will also be suitable to different types of inquiries, as discussed earlier in this report.

Throughout our investigation, witnesses were asked whether they had encountered any other process, whether in the public or private sector, that is not subject to project management, time deadlines or cost constraints. Witnesses consistently responded that they had not.

The Committee explored whether a possible solution to the delicate tension between set budgets and independence of inquiries could be setting a budget with the opportunity for it to be increased. Professor Cameron, who was involved in the Independent Jersey Care Inquiry (IJCI) described the inquiry as having an initial budget of £6 million, which was increased once the scope and range of evidence required became clearer – “We had to go back, make representations as to why more was needed and get that agreed”5. The IJCI panel final cost came to £23 million.

We heard that in wider scope inquiries, it is impossible to know at the outset the extent of necessary investigations, and limitations on budget or timescales could open up the risk of judicial review. Lord Hardie stressed that any indicative budget or timescale should be an informed decision, which, he argued, is impossible at the outset of an inquiry. He suggested that, when the Edinburgh Tram Inquiry was established, neither him as chair, nor the then First Minister had "any knowledge of what was involved or of how many documents, witnesses and so on we were talking about"3.

Some witnesses claimed that if budgets and timescales were set at the point of establishment and then had to be revised upwards, this could undermine public confidence in the inquiry, therefore impacting its effectiveness.

We note, however, that a similar approach has successfully been adopted in other jurisdictions. In New Zealand, for example, a budget and timeline are agreed at the outset of an inquiry, in conjunction with the different bodies involved, setting clear expectations of inquiries. If they require extensions to either timescales or budget, chairs must justify any request to the appropriate minister. The Institute for Government argued that this approach ensures accountability and efficiency, however, as explained by Rebecca McKee, “When I have been testing that recommendation in the UK context, there has been a lot more pushback, some of which I think is valid. Some of the delays are to do with Government or other bodies that are involved in the inquiry not being ready and not having their papers and documentation in order.”10

As summarised by the Deputy First Minister, Ministers set the parameters within which chairs make decisions. Those decisions will shape inquiry costs11. Discussions with witnesses revealed a “time-cost-quality triumvirate”6, which cannot be easily solved, and which also points to Dr Ireton’s recommendation of clearly defining an inquiry’s objectives at the outset. Dr Ireton argued that the discretion of the chair must be maintained, and that cost-effectiveness can instead be achieved with—

clarity of purpose and proportionate design,

flexible procedural framework,

transparent cost and timetable management, and

system-wide learning and oversight.13

Impact on public sector bodies

The headline Scottish public inquiries’ costs set out earlier, while high, outline only “the tip of the iceberg” (Gillian Mawdsley’s submission1). These figures do not include the costs to government departments or other public bodies, which will have to bear their own expenses, including instructing counsel, solicitors and officials. They also do not include overlap with business as usual and the impact on services.

As highlighted by NHS NSS in its written submission, “inquiries are resource intensive for participants, both financially and in terms of the time and resource required to assemble and share documentation and in attending to give evidence.”2 Mary Morgan of NHS NSS explained that costs could be categorised into—

costs of the inquiry that are visible, that are reported against and that can be accounted for in Parliament,