Finance and Constitution Committee

Pre-budget scrutiny 2020-21

Introduction

At our meeting on 5 June the Committee agreed to focus its pre-budget scrutiny (2020-21) on the operation of the Fiscal Framework, building on its previous work in this parliamentary session. Since the publication of the Committee’s report on Budget 2019-20, a number of documents have been published which are relevant to the operation of the Fiscal Framework and which have been useful in informing this pre-budget report—

Scotland’s Fiscal Outlook: The Scottish Government’s Medium Term Financial Strategy1

Scottish Fiscal Commission Economic and Fiscal Forecasts2

HMRC Scottish Income Tax Outturn (2017-18)3

Fiscal Framework Data Update4

Scottish Fiscal Commission Forecast Evaluation Report5

Fiscal Framework Outturn Report6

In July 2019, HMRC published outturn figures for Scottish income tax for 2017-18. This is the first time a full year of outturn data for Scottish income tax has been available since the power to set rates and bands for non-saving, non-dividend income tax was devolved to the Scottish Parliament. It is, therefore, also the first year of the operation of the reconciliation process for income tax. This report focuses on the operation of this process.

As part of the new budget process, the Committee has continued its full year approach to budget scrutiny including the following areas—

Earnings in Scotland;

Additional Dwelling Supplement;

VAT assignation;

Policy spillover provisions within the Fiscal Framework.

This report also provides an update on the Committee’s work in these areas.

Economic Performance

The Committee notes that a key element of the Fiscal Framework is that it is intended to incentivise the Scottish Government to increase economic growth relative to the UK economy.1 There is an expectation that if the Scottish economy outperforms the UK economy that this will benefit the size of the Scottish Budget through a higher increase in devolved tax revenues relative to the rest of the UK. Audit Scotland explain that—

The Fiscal Framework is intended to incentivise the Scottish Government to increase economic growth. Where the Scottish economy is performing relatively well, tax revenues will be higher and pressures on spending will ease. Where it performs relatively less well the effect will be to squeeze the budget, reducing available funding and increasing spending demands.

The SFC told us in June 2019 that the “Scottish economy has been particularly strong over the past two years. In the main that has been driven by a strong net trade performance, which, in part, has been driven by the depreciation in sterling.”2

The Scottish Government’s Medium Term Financial Strategy (MTFS) states that “2018 was a positive year for the Scottish economy, with growth relatively broad-based across the economy; the labour market delivering record levels of performance; and further growth in exports.”3 The Cabinet Secretary told us in June 2019—

our exports are on the rise, outperforming exports from the rest of the United Kingdom, and our foreign direct investment is second only to London and the south-east of England. Income tax is rising and earnings growth is on the up in real terms. Those are strong economic indicators and foundations.

Finance and Constitution Committee 12 June 2019, Derek Mackay, contrib. 12, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=12186&c=2186504

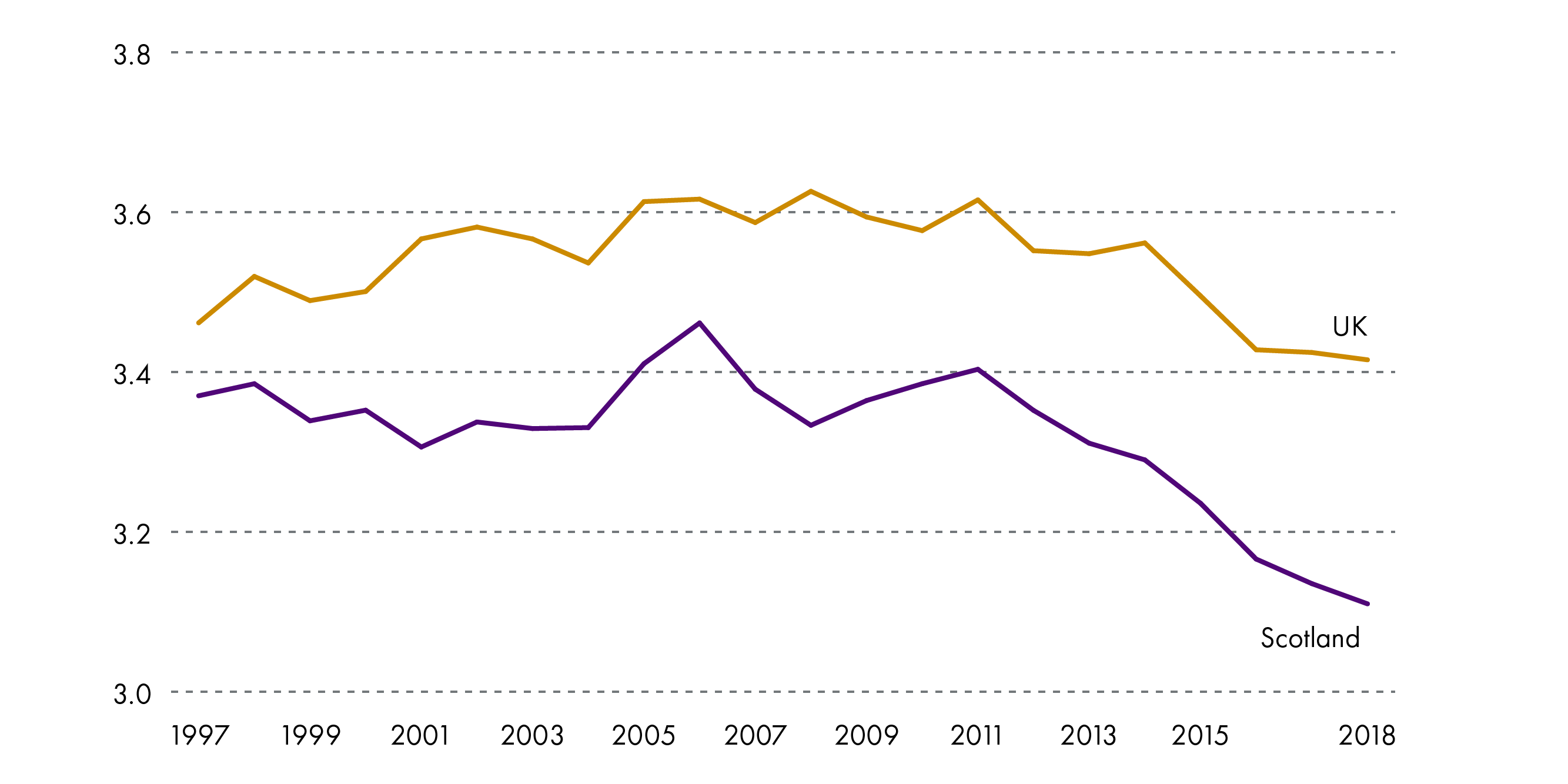

Table 1 below provides the outturn figures for GDP growth in Scotland and the UK for 2017/18 and 2018/19.

Table 1 - GDP Growth Outturn Figures  SPICe

SPICe

Table 1 shows that UK GDP growth outperformed Scottish GDP growth in 2017/18 both in overall terms and per capita. However, in 2018/19 the Scottish economy matched the overall performance of the UK economy and was stronger per capita. There may be some expectation, given the economic growth incentive built into the Fiscal Framework, that the Scottish Budget would to some extent be worse off in 2017/18 but would be better off in 2018/19.

However, this is not the case. As this report demonstrates, it is too simplistic to assume that faster relative economic growth will result in an increase to the size of the Scottish Government’s budget. While we would expect a positive relationship between GDP per capita growth and tax revenues over a period of several years, the relationship depends on a number of variables and some of these are discussed in more detail below.

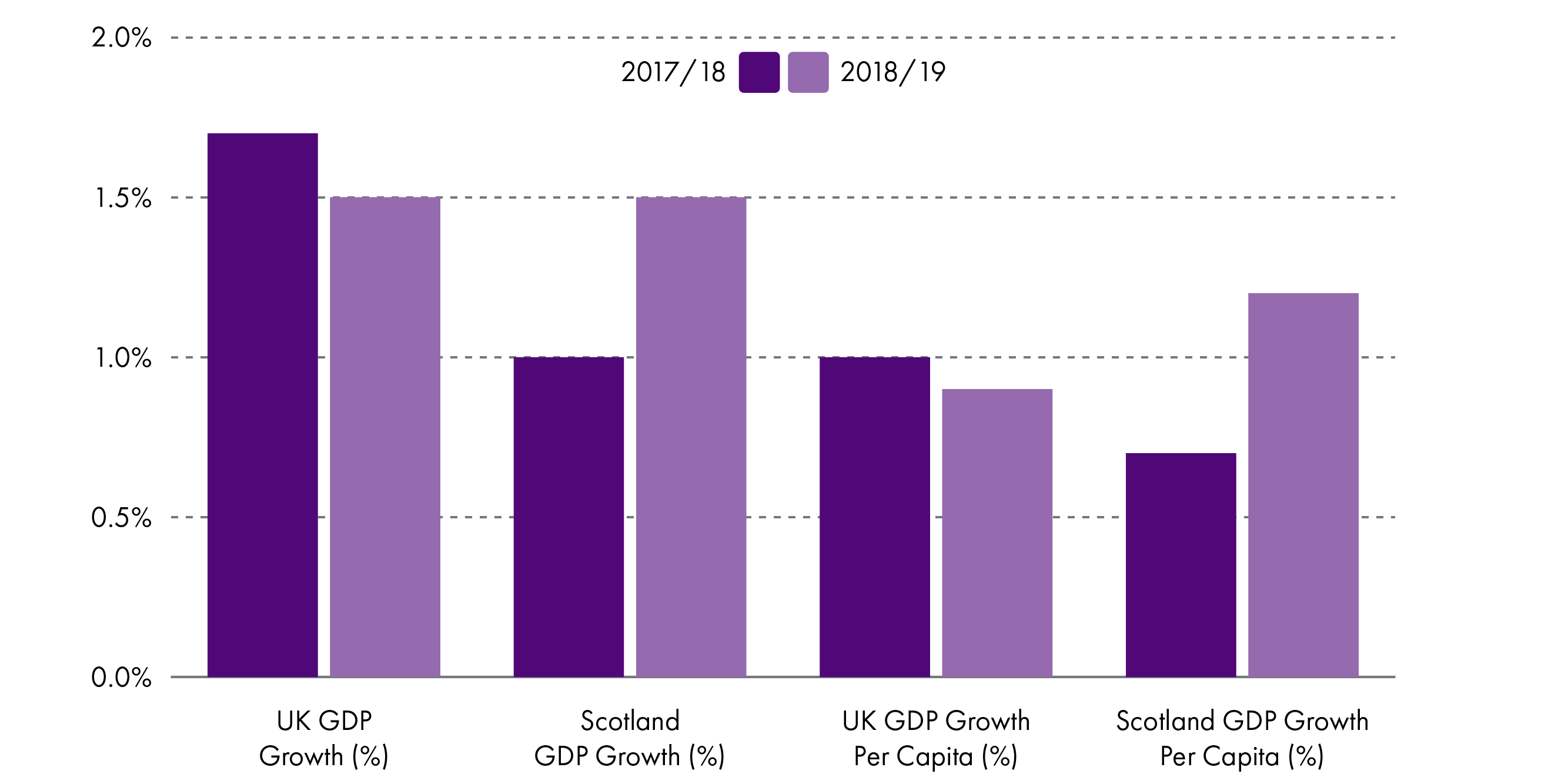

Table 2 shows the SFC’s forecast reconciliation figures for income tax for 2017/18, 2018/19 and 2019/20.

| Outturn Data Available | Budget Affected | Reconciliation (£m) | |

| 2017-18 | Summer 2019 | 2020-21 | -204 |

| 2018-19 | Summer 2020 | 2021-22 | -608 |

| 2019-20 | Summer 2021 | 2022-23 | -188 |

The SFC explain that—

In the UK, growth in tax revenues, and particularly income tax, has been more positive than expected over the last two years. When compared to slower growth in Scottish income tax revenues over the last two years, this means negative reconciliations in the years ahead.5

The size of the reconciliations is a consequence of forecast error in not foreseeing the differential performance of the growth in UK and Scottish income tax receipts. The key point is that higher per capita growth in income tax receipts in the UK compared to Scotland for 2017/18 and 2018/19 has a negative impact on the size of the Scottish Budget. This negative impact would occur even if the forecasts were correct; if the forecasts at the time when the Scottish Budget was introduced for 2017/18 and 2018/19 were more accurate then the Scottish Government would have had less funding to allocate for both of those financial years.

The Cabinet Secretary told us that it “does feel perverse that, when income tax is rising, overall tax take is up, gross domestic product is performing positively, unemployment is low and earnings growth has been increasing, we will have negative reconciliations over three years.”6

The Committee’s primary concern is the extent to which the risks and opportunities for the Scottish Government’s budget arising from tax devolution and the operation of the Fiscal Framework are as intended or whether there are unintended consequences which need to be more closely examined. The publication of outturn data for income tax for 2017-18 provides the first opportunity for more detailed examination of these risks and opportunities and this is discussed below.

Scottish Income Tax 2017/18 – Reconciliation Process

As the Committee has highlighted in previous budget and pre-budget reports, the Scottish budget is exposed to broadly two types of budget risk through the Fiscal Framework—

The first is the risk that the Scottish income tax base grows relatively more slowly than the equivalent income tax base in rUK. If this happens, then Scottish revenues are likely to be lower than the block grant adjustment. The implication of this is that the Scottish budget is worse off than it would have been had tax devolution not occurred;

The second is the risk of forecast error. This is the risk that a Scottish budget is based on a set of forecasts that turn out to have overestimated the level of funding available to the Scottish Government. If this happens, then a subsequent budget will need to address any shortfall.

It is important to note how these two risks interact. The first risk relates to the actual annual per capita growth in the level of Scottish income tax receipts relative to the level of per capita growth in the rest of the UK. The extent of this risk, therefore, does not become fully apparent until the outturn figures for income tax are published by HMRC.

The level of the second risk depends on the extent to which both the OBR and the SFC are able to accurately anticipate the extent of the first risk. This is explained by the SFC as follows—

If, for structural reasons, Scottish income tax revenue is going to grow more slowly than UK income tax revenue, that is a problem for the Scottish budget. At the moment, it is showing up as reconciliations because the forecasters did not anticipate it. Once we start anticipating it, it will be built into the budget and the forecasts. That does not mean that it will go away; it will just pop up in the budget instead of in reconciliations.

Finance and Constitution Committee 05 June 2019, Professor Smith, contrib. 90, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=12177&c=2184539

This means that, even though the forecasts may become more accurate over time and the size of the reconciliations become therefore smaller, the risk for the public finances does not necessarily reduce. Rather, any continuing risk arising from slower Scottish income tax growth relative to the rest of the UK would need to addressed by the Scottish Government when setting its budget rather than through the reconciliation process.

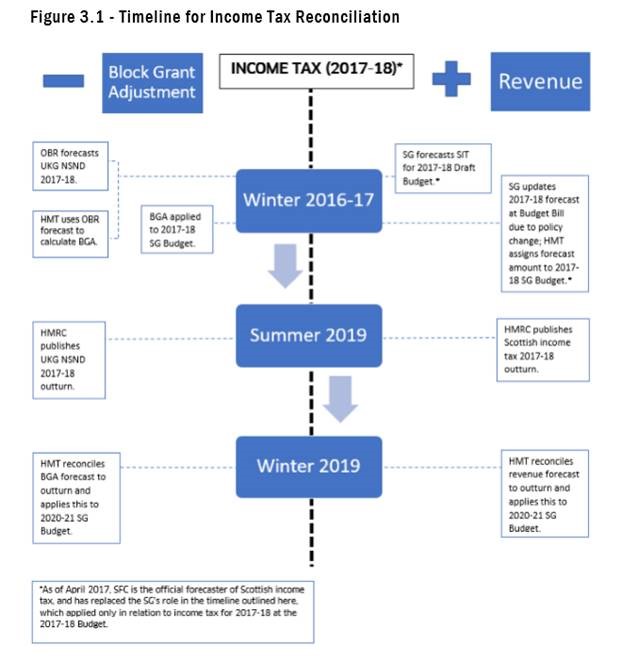

The income tax outturn data for 2017-18 provides the first opportunity for the Committee to examine in detail the extent of these risks. The timeline for the reconciliation process for 2017/18 is set out below.

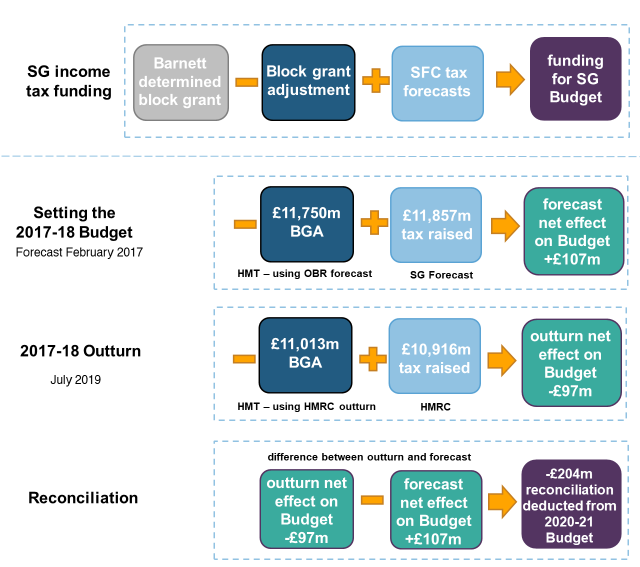

Following HMRC’s publication of the outturn figures in July 2019, the impact on the Scottish Budget can be calculated as set out below.

When the 2017-18 budget was agreed by the Scottish Parliament in February 2017, the level of Scottish income tax receipts was forecast to be £107m higher than the forecast Block Grant Adjustment (BGA). However, the outturn figures published by HMRC in July 2019 show that in fact Scottish income tax receipts were £97m lower than the BGA. This means that, based on the outturn figures, the 2017/18 budget should have been reduced by £97m rather than increased by £107m. The reconciliation figure is, therefore, £204m. This will be deducted from the 2020-21 budget.

The 2017/18 budget is now £97m lower than if income tax had not been partly devolved as a consequence of the first risk discussed at paragraph 16 above. This is despite the higher rate threshold being frozen in 2017/18. The second risk discussed above, which is forecast error, results in the 2017/18 budget being a further £107m lower.

The Fraser of Allander Institute state that “it’s important to not lose sight of the underlying driver of these errors on this occasion – that is the implication from Scotland’s tax base performing less well than the equivalent tax base in the rest of the UK.”2 Our Fiscal Framework Adviser points out that this is largely explained by slightly faster growth in average earnings in rUK than Scotland. This is discussed below.

Earnings Growth

Table 3 below shows the forecast and outturn growth in income tax determinants in Scotland and the UK for 2017-18.

Per cent growth Determinant Forecast Outturn Error (%) Scotland (SG) Employment 0.3 1.5 -1.2 Average earnings 2.3 1.0 1.3 Total earnings 2.6 2.4 0.2 UK (OBR) Employment 0.1 1.0 -0.9 Average earnings 2.4 2.7 -0.3 Total earnings 2.5 4.0 -1.4 Scottish Fiscal Commission

The SFC explained to the Committee that the “important thing is the growth rates of total earnings.” As shown in Table 3 the outturn in Scotland was 2.4 per cent and in the UK it was 4%. The SFC state in their evaluation report that the “reconciliation of -£204 million can be explained by slightly faster than expected growth in earnings in the rest of the UK and slightly slower than expected growth in earnings in Scotland.”1

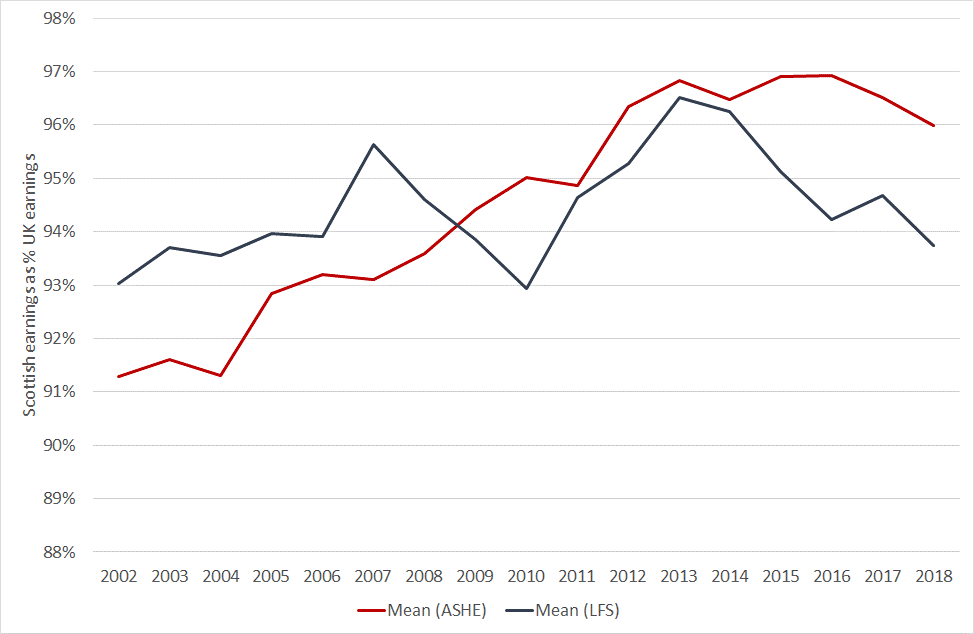

Our Adviser points out that average Scottish earnings growth – the key determinant of growth in income tax revenues – has been slightly slower than average UK earnings growth for several years now and that the magnitude of this differential varies depending on the data source considered.

Chart 1 shows that, according to the two major labour market surveys, Scottish earnings growth exceeded UK earnings growth throughout the 2000s and early 2010s, but that this has gone into reverse in more recent years. The exact extent of weaker Scottish earnings growth differs according to the two surveys, but the general observation is common to both.

Our Adviser points out that between 2002 and 2013 there was a remarkable convergence of Scottish earnings to the UK – average Scottish earnings were 91.5% of the UK average in 2002 (i.e. 8.5% below UK earnings) but were just 3% below UK earnings by 2013. In other words, Scottish wages grew more quickly than UK wages during this period, although remain slightly lower than the UK on average.

Between 2013 and 2016 there was no further convergence of Scottish earnings to the UK average. Moreover, in 2017 and 2018 Scottish average wages grew less quickly than in the UK. This relative slowdown in Scottish wage growth is also reflected in a relative slowdown in ‘real time’ PAYE tax data published by HMRC. Our Adviser suggests that understanding the causes of the relative Scottish earnings slowdown is an ongoing priority – as is determining what the Scottish Government’s policy response should be.

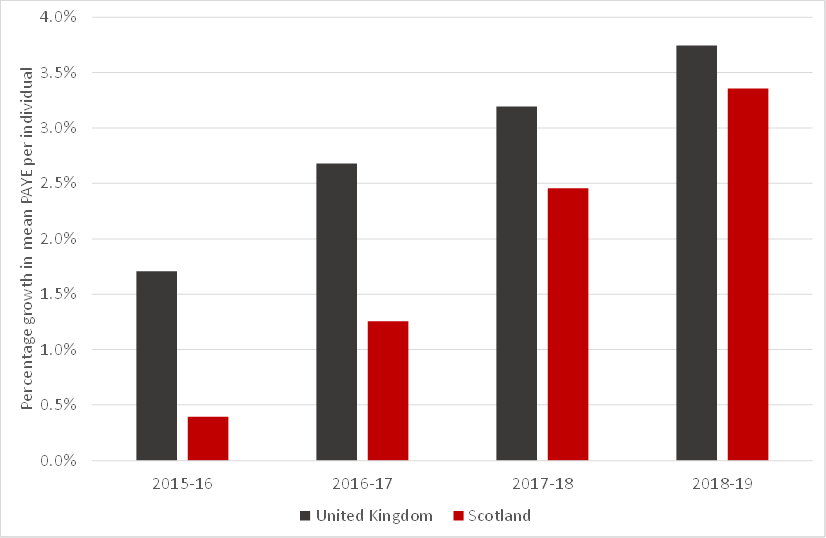

Another data source that has become available more recently is HMRC data on average PAYE earnings growth from taxpayer returns (Chart 2). This data shows that Scottish earnings growth has been weaker than rUK earnings growth consistently since 2015/16 (although the gap is narrowing year on year).

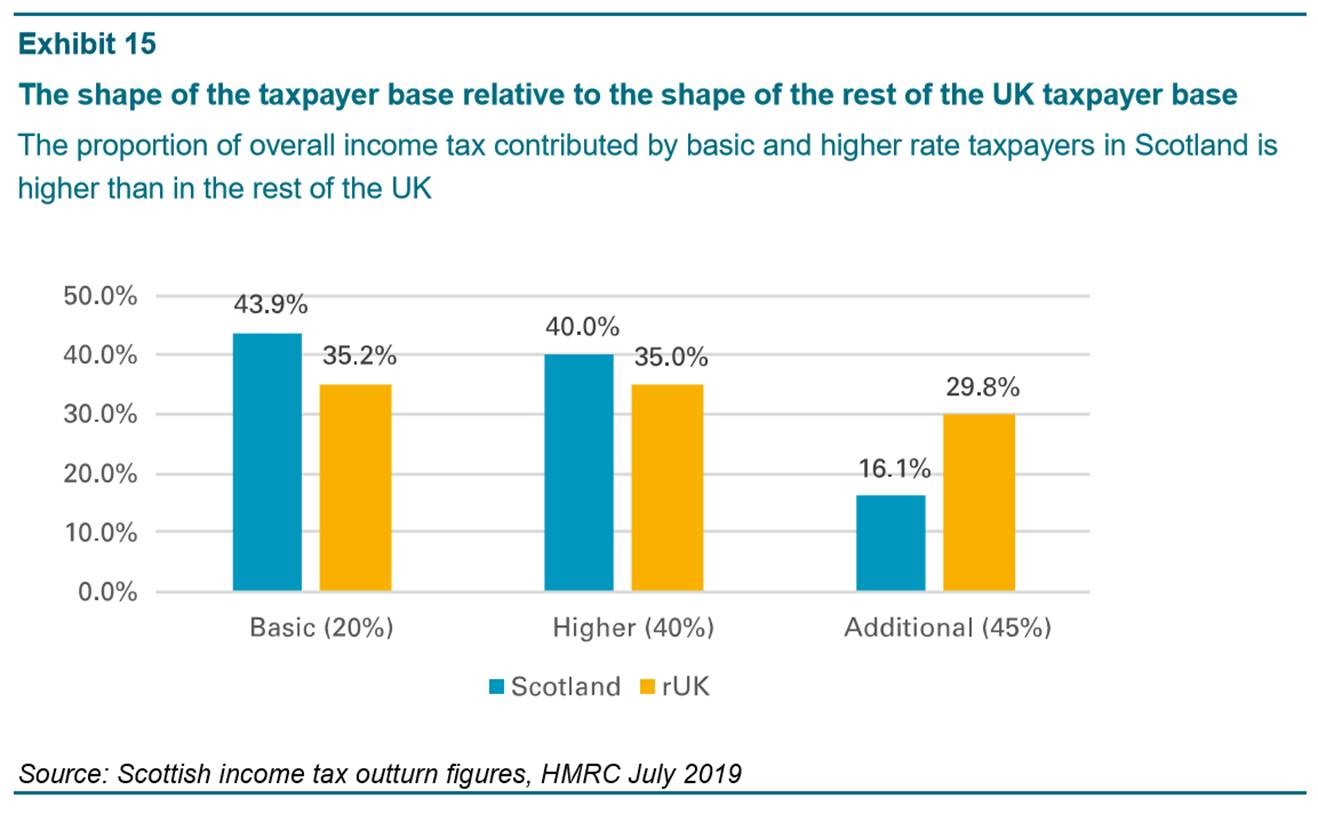

In the Committee’s report on the Budget 2019/20 we noted that the SFC had suggested that there is some evidence that slower earnings growth in Scotland is “due to the disproportionate level of higher taxpayers in the rest of the UK relative to Scotland.”2 The Committee explored this further in evidence with the SFC and the Cabinet Secretary as part of our all year round budget scrutiny.

The SFC told us in June 2019 that the “likeliest single explanation” of the recent difference in earnings growth between Scotland and the rest of the UK is that the latter “has a higher concentration of higher-rate taxpayers and the recent growth in UK income tax revenue has been concentrated among them.”3 They explained that neither they or the OBR were aware that the recent growth in income tax revenues “would be so strongly affected by distributional issues” and that had they been aware “Scotland would have had a smaller budget two years ago and we would not need a reconciliation now.”4

A key question for the Committee is whether these distributional issues are structural and may therefore continue to have a negative impact on the size of the Scottish budget. The SFC told us that “there is perhaps a structural issue with regard to the labour market in Scotland and that in the rest of the UK”5 and that it “seems to be a feature of the structure of the Scottish economy that Scotland has fewer higher rate taxpayers.6

Audit Scotland (Exhibit 157 below) point out that the Scottish income tax outturn statistics for 2017/18 show that as a proportion of its income tax receipts—

the Scottish Government has a higher proportion of its receipts from basic and higher rate tax payers;

the UK government has a higher proportion of its receipts from additional rate taxpayers.

Audit Scotland also point out that “additional rate taxpayers in the rest of the UK account for 1.1 per cent of taxpayers (308,000 taxpayers) compared to 0.5 per cent (13,800 taxpayers) in Scotland.” This means that if “growth in the economy leads to tax receipts more heavily linked to the incomes of people in a particular tax band, this would affect Scottish and rest of the UK tax receipts differently.”8

The Resolution Foundation told us that “Scotland has a less unequal pay distribution because it does not have as much at the very top. It has about the same as the rest of the UK, minus London and the south-east.”9 Professor David Bell explained—

Like it or not, we have very unequal income distribution, with the people at the top tending to pay a lot of the income tax. We are, nevertheless, less unequal than the rest of the UK. The difference in average earnings between Scotland and the rest of the UK is not really a great indication of income tax revenues, because people who are being paid the average will not actually pay that much income tax—it is the high earners who contribute a lot of the overall revenue.

Finance and Constitution Committee 24 April 2019, Professor Bell, contrib. 42, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=12061&c=2170199

The Resolution Foundation explained that if “you want higher income tax revenues, you need pay growth at the top."11

Chart 3 shows the ratio of those whose earnings are greater than 90% of other workers to someone whose earnings are only greater than 10% of other workers. Thus, in 2018 in Scotland, the worker at the 90th percentile earned 3.1 times more than the worker at the 10th percentile.

Chart 3: Wage Inequality: Ratio of 90th to 10th Percentile for Full-Time Workers ASHE

Professor Bell stated in written evidence to the Committee that “the figure shows that on this measure, income inequality in Scotland is lower than in the UK as a whole and has been falling since 2012.” He explained that the “difference between Scotland and the UK as a whole largely stems from the relative scarcity of very high earners in Scotland” and that “the fall in this ratio over this period is likely to have been partly driven by above inflation increases in the minimum wage.” He also states that although “there may have been a recent decline, compared to other European countries the UK has very high levels of inequality.”12

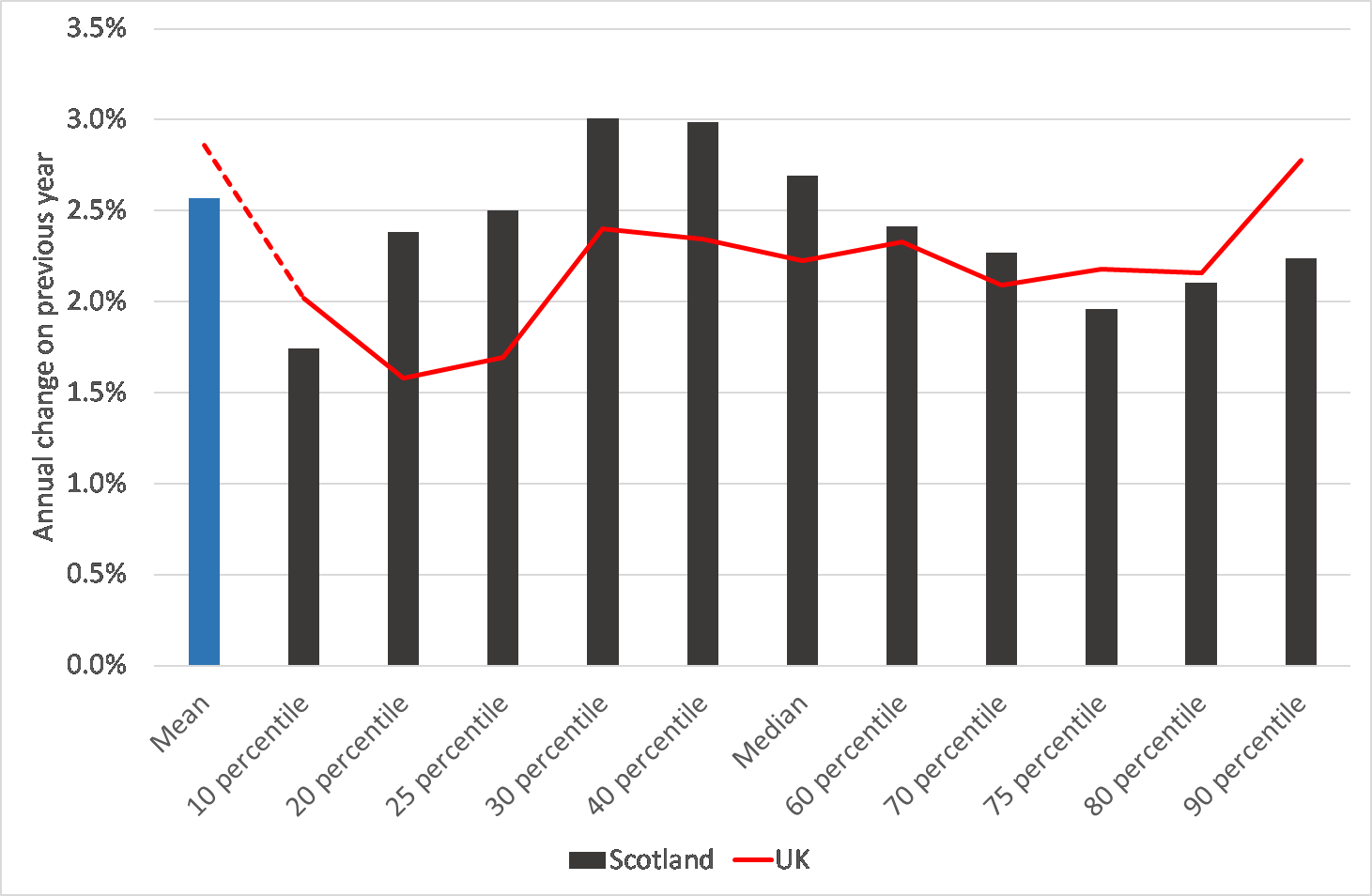

Chart 4 shows the growth in annual earnings across the income distribution in 2017-18 in Scotland compared to the UK.

The chart shows that while average earnings growth is slightly lower in Scotland, earnings growth in Scotland was higher from the 20th percentile to the 70th percentile, whilst earnings growth in the UK is higher at the bottom decile and in the top 30% of the distribution. This provides some evidence therefore that the relative growth of income tax revenues per capita in 2017/18 may be partially the result of relatively faster growth in the incomes of the higher paid in rUK, rather than simply being an issue of relatively faster earnings growth across the distribution. However, it is worth pointing out that more recently published earnings data shows the position between 2018 and 2019 to be the reverse of this – Scottish earnings at the top of the earnings distribution grew more quickly than in the UK. The Committee will examine closely the impact of this data on the outturn data for income tax for 2018/19 when it is published in July 2020 and the subsequent reconciliation figure.

The Cabinet Secretary’s view is that there “might be a structural issue around higher-rate taxpayers and deepening inequality in the rest of the UK.” 13 In his view “inequality in the rest of the UK is deepening as the top earners are earning more proportionately and as a quantum.” On this basis he suggests that “there is a case for the for the UK Government to reflect and acknowledge that the issue is not about economic performance, but about increasing inequality in the UK.”14

Welsh Fiscal Framework

An important difference between the Scottish Fiscal Framework and the subsequent Fiscal Framework agreed for Wales was the creation of a separate BGA for each band of income tax in Wales (the basic, higher and additional rates). On applying the adjustment to each band of income tax, the Welsh Fiscal Framework states—

As the composition of the income tax base in Wales is significantly different from the UK average, the two governments have agreed that the Comparable model will be applied separately to each band of income tax (basic, higher and additional rate). This ensures the new funding arrangements will deal with any UK government decisions to change the UK-wide income tax base (for example changes to the personal allowance) entirely mechanically. It will ensure the Welsh Government’s tax revenues are broadly unaffected by UK government policy decisions.1

This recognises the significant difference in the Welsh income tax base compared with the rest of the UK. A much greater share of Welsh taxable income is earned at the basic rate of income tax, compared with the rest of the UK. The implication of this different distribution is described by the Welsh Governance Centre thus—

This means that UK-wide factors which disproportionately impact taxable income at the basic rate band have much more of an impact on total tax revenues in Wales compared with the rest of the UK. For example, above inflationary increases in the personal allowance in recent years have significantly reduced taxable income at the basic rate, resulting in a much more pronounced impact on total Welsh revenues than in the rest of the UK.

“Conversely, the much greater share of taxable income earned at the additional rate in the rest of the UK means that UK-wide factors which influence taxable income at the additional rate will have a much greater impact on total revenues in the rest of the UK than is true for Wales.2

Our Adviser points out that creating separate BGAs for each income tax band means that the BGA is likely to match the trends in devolved Welsh revenues more closely than it would have using a single BGA for income tax as a whole.

The Committee asks that the Cabinet Secretary provides the data which supports his view that "inequality in the rest of the UK is deepening as the top earners are earning more proportionately and as a quantum."

The Committee, while mindful that we only have the first year of outturn data for Scottish income tax, notes that there are two potential structural issues relating to the operation of the fiscal framework arising from that data and from earnings data as follows—

The extent to which the distribution of the tax base is more unequal in rUK relative to Scotland;

The extent to which annual earnings growth is more unequal in rUK relative to Scotland.

This raises two further questions—

If economic growth in rUK disproportionately benefits higher-rate and additional-rate taxpayers relative to the distribution of the benefits of economic growth in Scotland, what does this mean for Scotland’s public finances;

What policy responses are available to the Scottish Government to address this impact.

The Committee recommends that the OBR and the SFC reflect on these distributional issues in advance of the next round of income tax forecasts. The Committee also recommends that the SFC examines whether these distributional issues are observed in the SPI data for 2018/19 data when that becomes available and writes to the Committee with its findings.

The Committee also notes that the Fiscal Framework agreement for Wales includes separate BGAs for each band of income tax to reflect differences in the Welsh tax base compared to rUK. The Committee recommends that the review of Scotland’s Fiscal Framework should consider the impact of differences in the Scottish income tax base relative to rUK.

Managing the Risk

The Committee has consistently called for the risks arising from the operation of the reconciliation process to be closely monitored and to be effectively and transparently managed. However, we note that despite the size of the forecast negative reconciliation, the MTFS does not address how the Scottish Government intends to manage this risk. The Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe) point out that it is surprising that there is “a lack of detail as to how the Scottish Government might meet the challenge presented by a possible £1 billion reconciliation over the next three financial years.”1

The Fraser of Allander Institute also note the—

lack of assessment as to what – in the government’s view – explains the recent differences in tax performance between Scotland and rUK. And crucially, SFC’s £1bn worth of income tax reconciliations between 2017-18 and 2019-20. You might also think that a medium term financial strategy document might detail how it will manage such a hit to revenues. But it doesn’t.2

The Auditor General for Scotland highlights that there is no detail in the MTFS “on how the Scottish Government would address a possible £1 billion shortfall due to forecast errors” and “little evidence to demonstrate that the strategy is a key component of the government's financial decision-making.” 3Audit Scotland point out that the “absence of high-level financial plans, priorities and scenarios will make the Parliament’s scrutiny of the forthcoming 2020/21 budget more difficult.”4

The SFC’s view is that—

These negative reconciliations mean less money will be available for future Scottish Budgets. The Scottish Government will be able to manage some of this through borrowing or use of the Scotland Reserve. However, the borrowing powers available to the Scottish Government and the rules about withdrawing funds from the Scotland Reserve mean that these will not cover all of the expected reconciliations. The Scottish Government would have to adjust its spending plans or increase taxes, and this should be borne in mind when formulating current policy.5

The Committee questioned the Cabinet Secretary on the lack of any information within the MTFS relating to how the Scottish Government intends to manage the risk arising from the reconciliation process. The Cabinet Secretary told the Committee that the Scottish Government assume that the forecast reconciliation figures “are correct for the purpose of having a plan to work our way through the reconciliations with the various tools at our disposal” and that the MTFS sets out “the approach that we will take to tackle the reconciliation.”6 The MTFS states that—

Once outturn data is published a reconciliation and a budget adjustment are agreed for the financial year thereafter. The Scottish Government will subsequently manage any negative or positive variance from the initially agreed budget position. The Scottish Government will closely monitor any risks arising from the net BGAs.7

The Cabinet Secretary was also asked by the Committee whether he would have to adjust his spending plans or increase taxes to address the forecast negative reconciliations. He responded that the main driver of the Scottish Government’s budget “continues to be the block grant” and therefore “it is not true that it will require just spending and tax adjustments.”8 The Cabinet Secretary also emphasised the “inadequacy of the fiscal framework in dealing with that scale of reconciliation” and, in particular, the “inadequacy of the resource borrowing powers.”6

While recognising the Scottish Government faces the challenge of not knowing the quantum of the block grant, we are somewhat disappointed in the lack of information in the MTFS regarding the forecast £1 billion negative reconciliation. The Committee invites the Cabinet Secretary to—

Identify whether the expectation of the Scottish Government is that sufficient money to fund the negative reconciliations will be available through:

-resource borrowing;

-the Scotland Reserve;

-increases to the block grant.

Provide an assessment of the likelihood of a structural risk to the Scottish Government’s budget arising from distributional issues in the tax base in Scotland relative to rUK;

Provide some scenario planning relating to the extent of this risk including potential policy responses to address the risk.

The Committee will also write to the subject committees asking them to provide details of the utility of the MTFS in informing their budget scrutiny and we will report on this in our report on the 2020-21 Budget.

Transparency

The Committee has repeatedly stated that full transparency is an essential element in securing public confidence in the operation of the Fiscal Framework. The Committee has also previously noted that there is no agreed scrutiny process for the reconciliation of outturn figures with forecasts. The challenges which this poses are illustrated by the reconciliation of the 2017-18 income tax forecasts with the outturn figures published by HMRC in July 2019.

The Committee notes that, in particular, no official document has been published by either the UK or the Scottish Government setting out the reconciliation process for income tax for 2017-18 and how the figure has been calculated. Rather, we had competing accounts of the reconciliation process in news releases published by both the UK and Scottish Governments. The HM Treasury press release stated that under the reconciliation process, the block grant will be increased by £737m and the Scottish Government’s income tax will be reduced by £941m.”1 The headline of the press release is “Scottish Income Tax shortfall offset by UK funding.”

The Scottish Government’s news release states that “the number of Scottish Higher and Additional Rate taxpayers combined, and the revenue paid by them, grew more quickly in Scotland than in the rest of the UK”, and that this “demonstrates that concerns taxpayers would relocate as a result of our tax policy choices were unfounded.”2 The headline of the press release is “Scottish income tax revenues grew by 1.8% in 2017-18.”

Our Adviser points out that HM Treasury’s interpretation is somewhat disingenuous. First, Scottish revenues were not £941m lower because of slower economic growth, but because outturn Scottish revenues in 2016/17 (which were not available at the time the 2017/18 forecasts were made) were lower than anticipated. In other words, most of the explanation for the lower than forecast outturn data in 2017/18 reflects that revenues turned out to be lower than expected before income tax was transferred.

Secondly, the UK Government did not offset this lower outturn with increased funding to reflect some risk-sharing mechanism; rather, the block grant adjustment was lower than forecast (i.e. less was deducted from the block grant) to reflect the lower 2016/17 outturn. The implication of this is that the UK Government had been collecting less income tax revenue from Scotland than had been thought, and as a result was implicitly foregoing less revenue by transferring income tax to Scotland. The Fiscal Framework contains no ‘risk-sharing mechanism’ that protects the Scottish budget from slower than rUK growth – the Scottish budget is exposed in full to any such divergence.

The Fraser of Allander Institute state that we’re “puzzled why the UKG chose such language, particularly given the way it has been subsequently interpreted.”3

The Scottish Government requested that the UK Statistics Authority (UKSA) consider that HM Treasury’s view that there was a “£941m shortfall in Scottish tax revenues due to lower growth in Scotland” in 2017/18 was inaccurate. They responded that—

We agree with you that this is incorrect. The principal reasons for the block grant adjustment were in fact an initial overestimate of the Scottish tax base and faster growth of tax receipts than expected in the rest of the UK.4

The UKSA subsequently wrote to HM Treasury recommending—

future HM Treasury press statements based on these statistics provide better explanations of the causes of changes to the Scottish income tax revenues and the associated Block Grant Adjustment. This will reduce the risk that users draw misleading conclusions from the statistics and the statements that draw on them.5

They also suggested that “to fully inform the public it would be helpful to present this framework in line with our Code of Practice for Statistics, considering how the statistics can be best presented in a clear and unambiguous way.5

With regards to the Scottish Government’s news release, our Adviser points out that, given that the higher rate threshold was frozen in Scotland but increased by more than inflation in rUK, we would expect the number of higher rate taxpayers to grow more quickly in Scotland than rUK. Moreover this in itself tells us nothing about whether there was or wasn’t some taxpayer response to the tax changes.

The Fraser of Allander Institute argue that, given the complexity of the fiscal framework, “the onus must be on both governments to articulate how the framework is operating, the various changes from year-to-year and any risks, in a straightforward and transparent manner.” In their view, “the risk of not doing so – and seeking to score political points at every turn – is that confidence in the underlying process of fiscal devolution could be eroded.7

The Committee recommends that HM Treasury and the Scottish Government work together to agree an approach to the reconciliation process which is transparent and which will increase public understanding of the Fiscal Framework. The Committee recommends that consideration should be given to the following—

A document jointly agreed by HM Treasury and the Scottish Government should be published annually setting out the income tax reconciliation process including a detailed explanation of the reconciliation figure;

This document should be published and sent to the Committee in early June and provide a provisional reconciliation figure based on the most recent set of OBR and SFC forecasts so as to allow Scottish Parliament scrutiny prior to our summer recess;

Any adjustments to the final reconciliation figure following HMRC’s publication of the audited outturn figures can be provided in writing to the Committee.

Data

The SFC explained that quite small errors in the earnings forecasts are driving quite a lot of the reconciliation errors and that they have been asking for better and more timely earnings data for Scotland. They suggest that one “of the things which could help is pressure from the Committee on the Office for National Statistics (ONS) and the Scottish Government to start thinking about and working on improving the quality of earnings data in Scotland.1

The Committee asks the Scottish Government and ONS to provide an update on what progress has been made in improving the quality of earnings data in Scotland.

Policy spillovers

The Smith Commission stated that there should be no detriment as a result of UK government or Scottish Government policy decisions post-devolution. Financial consequences of policy decisions are known as policy spillovers and are covered under the Fiscal Framework agreement1 which states that—

where either government makes a policy decision that affects the tax receipts or expenditure of the other, the decision-making government will either reimburse the other if there is an additional cost, or receive a transfer from the other if there is a saving.

The Fiscal Framework divides these policy spillovers into 2 categories—

Direct effects – these are the financial effects that will directly and mechanically exist as a result of the policy change (before any associated change in behaviours);

Behavioural effects – these are the financial effects that result from people changing behaviour following a policy change.

The Committee also notes that the Fiscal Framework only applies to the direct effects of policy change.

Personal Allowance

The Committee noted the Scottish Government’s request that a “policy spillover” be considered in relation to the increase of the Personal Allowance for 2018-19 and 2019-20 and agreed to write to the Chief Secretary to the Treasury (CST) asking her view as to whether the policy spillover provisions within the Fiscal Framework had indeed been triggered by the decision of the UK Government's decision to increase the Personal Allowance for 2018-19 and 2019-20.1

In her response,2 the CST said that the UK Government's position was that Consumer Price Index (CPI) linked increases to the Personal Allowance in April 2018 did not constitute a change in UK Government policy however, the UK Government did accept that the above inflation increases to the Personal Allowance in April 2019 and the freeze to Personal Allowance in 2020 does constitute a change in policy. She said that HM Treasury officials are currently considering the Scottish Government's analysis of this issue and that—

If the Scottish Government and HM treasury agree on the methodological approach, we will consider if any transfer of funding (in either direction) is due for these years.

The Cabinet Secretary wrote to the Committee on 25 October 2019 3, stating that he has been unable to make progress with HM Treasury on the issue. He reiterated his view that he disagrees with the previous CST that inflationary increases to the personal allowance do not constitute a spillover effect. He points out that joint UK and Scottish Government guidance notes that “policy decisions in relation to personal tax that are not fully captured by the block grant adjustment mechanism” would be considered direct effect spillovers. He also points out that the Welsh Government’s fiscal framework explicitly cites increases in the personal allowance as an example of a direct spillover effect.

The Committee will write to HM Treasury seeking a written update on this issue and will invite the CST to give oral evidence on this issue and other aspects of the operation of the Fiscal Framework including the reconciliation process.

Additional Dwelling Supplement

The Committee held two evidence sessions on the Additional Dwelling Supplement (ADS), a roundtable discussion 0n 29 May1 and evidence from the Minister for Public Finance and Digital Economy on 12 June 2019.2 The Committee was interested in how ADS had been operating in practice and whether unintended consequences had arisen with the introduction of ADS. The Committee was also interested in the impact of ADS on Scotland’s housing market.

Context

Since the introduction of Land and Buildings Transaction Tax (LBTT) in 2013, the Scottish Government has introduced both primary and secondary legislation with the purpose of amending the parent Act. It was amended by the Land and Buildings Transaction Tax (Amendment) (Scotland) Act 2016 which introduced a 3% surcharge on the purchase of additional properties for £40,000 or more (ADS) from 1 April 2016.

One of the policy objectives of the 2016 Act was that married couples, those in a civil partnership and cohabitants (those living as if a married couple) are treated for the purposes of ADS as one economic unit in order to address the risk of properties being moved between individuals for the purposes of tax avoidance.

The intention was that the ADS could be reclaimed when purchasing a main residence where the sale of the former main residence took place within 18 months. However, the legislation required the additional amount to be chargeable if spouses, civil partners or co-habitants were jointly buying a home to replace a home that was owned by only one of them. As a result, the relief could not be claimed in this scenario as only one name appeared on the title deeds.

This meant that “the couple is being treated as one economic unit when determining if the ADS applies, but not when it comes to determining whether ADS should be repaid.” In June 2017, the Scottish Government addressed this anomaly via secondary legislation.

The Land and Buildings Transaction Tax (Additional Amount-Second Homes Main Residence Relief) (Scotland) Order 2017 ("the 2017 Order") was laid to provide that the ADS was not chargeable if the buyer was replacing the buyer’s only or main residence however, prior to this 2017 Order coming into force, it was chargeable if couples were jointly buying a home to replace a home that was only owned by one of them. The 2017 Order allowed that in these circumstances, the ADS paid as two dwellings were owned, could now be reclaimed despite only one name being on the title deeds to the former main residence.

The Land and Buildings Transaction Tax (Relief from Additional Amount) (Scotland) Bill was introduced by the Scottish Government on 13 November 2017. Its purpose was to give retrospective effect to the amendments made by the 2017 Order.

The Committee issued a call for views on the Bill and took evidence from the then Cabinet Secretary for Finance and the Constitution at its meeting on 7 February 2018. In its Stage 1 report, the Committee supported the general principles of the Bill and also raised a number of issues which were outwith scope of the Bill but raised during its scrutiny concerning unintended consequences of tax legislation.

Operation of ADS

During the roundtable session in May 2019, witnesses told us that ADS was complicated to administer and it was difficult for people to understand when it applies to them or if they qualified for relief.

We were told that this is further complicated by some unintended consequences of the legislation. Witnesses said that there have been cases raised whereby individuals have claimed their payment of the tax has been unjust and against the spirit of the legislation. The Law Society of Scotland (LSS) highlighted the following anomalies which they believe needs to be addressed—

couples who are planning to get married but who do not live together before they do and who have to sell a house that only one of them owns before they buy a house in joint names;

people living together but not in the house that they are going to sell, they live in another other house.

Divorcing couples who have to pay ADS if one of them departs and buys a new residence;

ADS being payable on main properties and on any ‘granny flat’ or annexe.;

A lack of clarity regarding at what point inherited dwelling is treated as owned by the beneficiary;

ADS being payable on low value shares in inherited dwelling;

ADS being payable where someone’s old residence is rented not owned.

During evidence, the Minister said she was sympathetic to a number of these issues however she would need a deeper understanding of the extent of the problems before considering any changes to the legislation. Regarding the calls to change the legislation, she told the Committee—

First, they highlight the need for us to think more generally about how we make changes to devolved taxes. Secondly, in terms of the changes that are called for, we need to think about how we balance specific individual situations with the potential for unintended consequences in a complex tax.

Finance and Constitution Committee 12 June 2019, The Minister for Public Finance and Digital Economy (Kate Forbes), contrib. 183, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=12186&c=2186675

Following the evidence session, the Committee wrote2 to the Minister asking the Scottish Government to work with Revenue Scotland to gather data regarding the number of people affected by each of these anomalies and, once collated, provide this information to the Committee.

In addition, the Committee requested that the analysis of responses to the Scottish Government’s consultation on the future of devolved taxes is sent to the Committee.

In her response3, the Minister confirmed that she would provide the Committee with the analysis of responses to the Scottish Government’s consultation on the future of devolved taxes when it is published.

She stated that the LBTT return does not allow for any detailed assessment as to the reasons why taxpayers are due to pay the ADS, whether it be in relation to various joint buyer scenarios, purchases follow divorce or separation or because a property is being used as a holiday home or a buy to let. She said—

My officials will however work together with Revenue Scotland to explore whether there are other sources of evidence which could be drawn on to offer the Committee some commentary on the extent to which the various highlighted scenarios occur...I will also ask my officials to analyse the official correspondence received since the introduction of the ADS in order to provide some supporting evidence.

The Minister wrote to the Committee on 28 October 20194 providing an analysis of all the correspondence to the Scottish Government related to LBTT since 1 April 2016 when ADS was introduced. During this period the Scottish Government has dealt with 162 cases which focused on ADS. During the same period ADS was paid in just under 75,000 transactions. Of the 162 cases, 31 involved cases relating to the potential anomalies highlighted by the LSS above.

The Minister notes that this analysis, while recognising that it captures only correspondence with the Scottish Government, does not suggest that the issues identified by LSS are widespread. At the same time the Minister recognises that challenging circumstances can occur in individual cases and she has asked her officials to undertake further work on this matter. The Minister also encourages relevant organisations to come forward with any evidence they can provide to support further consideration of this matter.

Revenue Scotland received 859 queries relating to ADS between April and September 2019 but they have written to the Committee explaining that these queries “are not held and recorded in the sort of detail that allows for a detailed analysis of the issues that the Committee are seeking to explore."5

The Committee notes from the available evidence, the potential anomalies identified by the LSS do not appear to be widespread. The Committee welcomes the Minister’s acknowledgement that challenging circumstances can occur in individual cases and that she has asked her officials to undertake further work on this matter. The Committee requests that it is kept updated with the progress of this work.

VAT assignment

The Scotland Act 2016 provided for the first 10 pence of the Standard Rate of Value Added Tax (VAT), and the first 2.5 pence of the Reduced Rate, to be assigned to the Scottish Government. The Fiscal Framework set out that VAT assignment would be implemented in 2019-20 with a one-year transitional period during which VAT assignment will be calculated, but with no impact on the Scottish Government’s budget.

The assignment of VAT will be based on a methodology that will estimate expenditure in Scotland on goods and services that are liable for VAT. The draft model for calculating Scottish VAT receipts was published in November 2018 and was expected to be finalised by the Joint Exchequer Committee in spring 2019. Ongoing discussions between the UK and Scottish Governments on the methodology has meant that this has not yet been finalised so the initial plan for determining the Scottish Government's budget in part by forecast and final estimated VAT receipts in Scotland from 2020-21 has been delayed.

Last year, during the Committee's budget and pre-budget scrutiny, the Committee considered the methodology for VAT assignment for Scotland and noted that basing VAT assignments for Scotland on estimated figures could introduce further volatility into Scotland's public finances.

The Committee asked the Scottish Government to keep the Committee updated on the development of the methodology used for assigning VAT to Scotland in advance of it being finalised by the Joint Exchequer Committee in spring 2019.

Given the impact that VAT assignment will have on the Scottish Budget, the Committee explored the issue further with stakeholders in a roundtable discussion on Wednesday 13 March 2019.1 Following this session, the Committee agreed to write to the Scottish Government on the issues raised during discussion.2

The Committee asked the Cabinet Secretary to respond to points made that the main challenge in assigning VAT was in how to calculate a robust estimate and the questions which also arose around the data sources being used in the model, such as the annual survey in hours and earnings, as opposed to real time information from HMRC. The Cabinet Secretary welcomed the Committee's consideration of VAT assignment3 and gave evidence on 8 May 2019 on these issues4.

During evidence, the Cabinet Secretary explained his concerns centred on the fact that VAT assignment is based on survey data and estimates. He said—

We will never have outturn data; we will always be comparing one set of estimates with another set of estimates. Unlike what happens with income tax, there will be no reconciliation... I am concerned about the accuracy of the assignation approach, given that we are talking about almost £6 billion of revenue. There is a lack of certainty about its accuracy.

Finance and Constitution Committee 08 May 2019, Derek Mackay, contrib. 57, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=12087&c=2173999

In addition, he said that the potential impact of Brexit could affect the economy, consumption and VAT receipts and the Scottish Government did not know whether the impact of this on Scotland would be disproportionate. He explained that this uncertainty and lack of data carries a disproportionate risk. He told us—

At the moment, we face uncertainty with Brexit, which could have an impact on the economy. Given that we face volatility, added uncertainty and concerns about the level of accuracy of the assignation process, it does not feel as though we are in a position to sign off the proposal.

Finance and Constitution Committee 08 May 2019, Derek Mackay, contrib. 59, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=12087&c=2174001

The Cabinet Secretary was asked about what level of risk would be tolerable and had this been discussed with HM Treasury. He said the work undertaken to date on the methodology has resulted in a high level of risk due to the inherent uncertainty associated with basing assignment on estimates. When asked about mitigation, the Cabinet Secretary said—

The UK Government might propose things that I would be open to, such as no financial detriment, recognising that we cannot push and pull levers here to fix the VAT issue. If the UK Government wants to respond with some sort of protection or mitigation, of course, I will engage with it constructively.

My point right now is that, short of that, not implementing VAT assignation until we have more data and a deeper understanding of what the model produces feels like the right thing to do.

Finance and Constitution Committee 08 May 2019, Derek Mackay, contrib. 125, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=12087&c=2174067

Following the evidence session, on 15 May the Cabinet Secretary wrote to the CST8 setting out his concerns about the proposed approach to assigning VAT in Scotland confirming that—

As a result, the only appropriate course of action at present is to seriously consider the case for a delay to the implementation of VAT assignment and review the case at the time of the Fiscal Framework review.

On 2 October 2019 during pre-budget scrutiny evidence, the Cabinet Secretary was asked what the current situation was regarding VAT assignment in Scotland. He told the Committee that he had written to the new CST expressing his concerns and that he expects a reply 'fairly imminently' and will update the Committee. He said—

...if the UK Government can provide further solutions and remedies to those challenges, we can engage further. I am advised that a response to my request is imminent, which I will share with the committee as quickly as I can.

Finance and Constitution Committee 02 October 2019 [Draft], Derek Mackay, contrib. 68, http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/parliamentarybusiness/report.aspx?r=12298&c=2205768

The Cabinet Secretary wrote to the Committee on 25 October10 stating that a reply from the CST is expected in advance of the UK Government budget and that he will update the Committee once this has been received.

The CST has written to the Committee11 stating that the transition period for Scottish VAT assignment will be extended by one year with full implementation now in April 2021. He states that while he considers the VAT assignment methodology to be “fundamentally sound” he has “listened to the concerns raised” and in particular, “it is also necessary to identify and manage potential uncertainty in the underlying survey data."

The Cabinet Secretary has written to the Committee12 confirming that he is happy to agree to the delay of the implementation of VAT assignment. He also reiterates his concerns about the robustness of the assignment methodology and states that the delay gives more time to consider those concerns and seek solutions.

The Committee invites the Cabinet Secretary to keep the Committee updated on progress in seeking solutions and will invite Scottish Government and UK Government officials to give evidence once the further work they are undertaking is completed.

Conclusion

The publication of outturn data for Scottish income tax for 2017-18 is the first opportunity to consider the real impact of income tax devolution on the Scottish budget. This report has sought to highlight a number of lessons which can be learned from how the inaugural reconciliation process for income tax has worked. These can be summarised as follows—

There is a potential structural risk to the Scottish budget arising from differences in the distribution of the tax base in Scotland and rUK;

There needs to be much more detail in the MTFS on the Scottish Government’s assessment of that risk and some scenario planning of potential policy responses to that risk;

There needs to be a joint approach between the UK Government and the Scottish Government to the reconciliation process which is transparent and increases public understanding.