Finance and Constitution Committee

Stage 1 report on the Referendums (Scotland) Bill

Introduction

The Referendums (Scotland) Bill1 (“the Bill”) was introduced by the Scottish Government on 28 May 2019. The Finance and Constitution Committee (“the Committee”) has been designated lead committee by the Parliamentary Bureau. The role of the Committee at Stage 1 is to consider and report on the general principles of the Bill.

The purpose of the Bill as set out in the policy memorandum is to provide “a legal framework for the holding of referendums on matters that are within the competence of the Scottish Parliament.”2

The Committee received 16 written submissions to its call for evidence and held a number of oral evidence sessions details of which are on our webpages. The Committee also appointed an Adviser, Dr Alistair Clark, to support its scrutiny of the Bill. The Committee would like to thank Dr Clark and everyone who provided written and oral evidence. A glossary of terms used in the report is provided in Annex A.

The evidence the Committee received was strongly supportive of the Bill’s aim to put in place a generic framework for referendums. At the same time the evidence we received also raises significant concerns with some elements of the Bill and especially the extent of the regulatory powers for Ministers and the proposed approach to question testing. A number of suggestions for strengthening the Bill have also been proposed by witnesses and considered by the Committee.

The Committee welcomes the approach taken by the Cabinet Secretary for Government Business and Constitutional Relations (“the Cabinet Secretary”) in his oral evidence at Stage 1. In particular, that he is “open to alternative approaches to all aspects of the Bill” and “how it can be improved in the light of both evidence that we get from stakeholders and experts and the views of individual Members.”3 The Committee also welcomes that the Electoral Commission is continuing to have discussions with Scottish Government officials about the recommendations which it has made to improve the Bill.

The recommendations in this report are intentionally drafted to inform an open discussion on how the Bill can be improved based on the substantial evidence the Committee received including the ongoing discussions between Scottish Government officials and the Electoral Commission.

Policy Objective

The policy objective of the Bill “is to put in place a generic framework for referendums that provides technical arrangements which can be applied for specific referendums.”1 The Bill follows the precedent of Part 7 of the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000 (“PPERA”) which provides a standing framework for UK referendums.

The Bill Team explained to the Committee that the generic framework is intended to be used for referendum questions "within the competence of the Parliament, it would not allow a question about a reserved matter."2

The Electoral Commission’s view is that the framework “would help to provide clarity of the rules for anyone administering or campaigning at a particular referendum.” They also point out that it “would enable Counting Officers (COs), campaigners and the Electoral Commission to begin appropriate planning and preparation at an early stage, rather than wait for detailed legislation to be finalised on each occasion that a referendum is proposed.” They told us that all in all, “we support the direction of travel that is represented in the bill.”3

The Scottish Assessors Association’s (SAA) welcome the Bill on the basis that “there will be one set of legislation to govern all referendums in Scotland” which “allows for consistency—it avoids individual bills being introduced and, therefore, potential variation between one referendum and another.”4

A number of witnesses also welcomed the proposal for a standing framework for referendums as being consistent with international good practice. The Institute for Government (IfG) state that the overall policy objective of the Bill is a “good one” and that a “regulatory framework is necessary to ensure that referendum campaigns are free, fair and can command widespread legitimacy.” Their view is that “standing legislation is preferable for the purposes of consistency and to prevent manipulation of the rules for specific referendums.”

The Electoral Management Board (EMB) for Scotland’s view is that rationalising “existing laws to create a single, consistent framework governing referendums offers many benefits to the voter, to campaigners, the regulator and electoral administrators.” They see this “as a wholly positive policy direction.”

Dr Theresa Reidy, University College Cork, agrees that the principal objective of the Bill is an important one and is consistent with core standards set out by the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IIDEA) and the Council of Europe. Dr Alan Renwick, Deputy Director of the Constitution Unit, shares a similar view. He suggests that the proposal for a standing legislative framework should be “strongly welcomed” and that the absence of such a framework “creates a danger that the rules might be unduly tailored to suit the purposes of the government of the day in a particular vote.” He also notes that the Bill “improves upon the PPERA framework in several respects.”

The IfG recognise that the Bill “improves on UK practice in some ways” and Professor Toby James, University of East Anglia, suggests it “rightly achieves an important principle of legal and technical simplicity.”

The Committee supports the policy objective of the Bill to put in place a generic framework for referendums on the basis that the Bill is amended to reflect the weight of evidence we received as discussed in detail throughout this report.

The Bill can be broken down into three main areas:

the power to provide for referendums;

conduct of polls and counts;

campaign rules.

This report addresses the evidence the Committee received in relation to each of these areas.

The Power to Provide for Referendums

Section 1

Section 1 of the Bill allows for Scottish Ministers to make regulations under the affirmative procedure to provide for the holding of a referendum throughout Scotland. The regulations must specify:

the date on which the referendum will be held;

the form of the ballot paper to be used, including the wording of the question or questions and the possible answers to it or them;

the referendum period.

The Electoral Commission must be consulted on these regulations before they are laid in Parliament.

There are no equivalent powers for UK Ministers within Part 7 of the PPERA and each UK referendum requires primary legislation. Indeed, Dr Alan Renwick states in his written submission that “I have found no well-functioning parliamentary democracy that gives Ministers blanket authority to call a referendum by secondary legislation.”

The Committee asked the Scottish Government’s Bill team to explain why these powers are in the Bill. They responded that it “relates to the certainty of the timetabling” and “will ensure that we have a predictable timetable from the point at which secondary legislation is introduced.” When asked by the Committee to elaborate further, the Bill team explained the “time for considering secondary legislation is set out in parliamentary procedures, whereas there is a lot more flexibility in the time that a bill can take to go through those procedures.” 1

The IfG do not accept that this is “an adequate justification for curtailing scrutiny” and that “the regulation-making power should be removed from the bill.” Their view is that “primary legislation should provide the basis of any future referendums in Scotland.”

Dr Renwick’s view is that the power to call a referendum using secondary legislation violates the core principle that any proposal to hold a referendum should be subject to detailed scrutiny. Such scrutiny “is possible only if a referendum can be called only through primary legislation rather than secondary legislation.”2 He notes that while the regulation would be subject to the affirmative procedure the Parliament would not be able to make amendments and that this approach “sends the wrong signal as to how decisions on referendums will be treated.” He recommends that this power should be removed from the Bill and that the power to call a referendum should be subject to primary legislation.

The Faculty of Advocates point out that Section 3 of the Bill anticipates that some referendums will be initiated by primary legislation. Referring specifically to an independence referendum their view is that it is difficult to envisage circumstances “in which the holding of such a referendum and the framing of the question to be put would be more appropriately initiated under secondary legislation than by the Scottish Parliament considering and debating a Bill.”

The Law Society of Scotland (LSS) are concerned that the powers in Section 1 of the Bill will have the effect of reducing the time for parliamentary or public scrutiny. Their view is that "legislation setting the date for the referendum and the question or questions to be asked should take the form of an act or, at the very least, a Scottish statutory instrument that is subject to the super-affirmative procedure, but that would be a very sub-optimal position."3

The Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee (DPLRC) note that “there may be times where using delegated powers is appropriate but that different referendums may require a different level of parliamentary scrutiny – either primary or secondary legislation.” Their view is therefore that the “one-size-fits-all approach in the Bill does not therefore provide sufficient flexibility to cater for issues of such national significance such as constitutional or moral questions which might be asked in a referendum.”

The Cabinet Secretary’s view is that we “should not see all referenda as the same, therefore, the scrutiny of all referenda should not be the same. We could have a super-affirmative process for some and primary legislation for others.”4 In his evidence to the DPLRC he “introduced the concept of whether there should be a differentiation between types of referendum in relation to how scrutiny should take place” and in his view there “is huge potential there.”

The DPLRC recommend that the Bill should be amended at Stage 2 to provide clear criteria for whether future referendums should be provided for by either primary or secondary legislation. While recognising that further discussion is required in formulating this criterion they recommend that a referendum question which requires an Order made under the delegated power in section 30 of the Scotland Act 1998, as well as questions about significant moral issues, should require primary legislation. The Cabinet Secretary told us that “there is an argument for having primary legislation for issues that are subject to a section 30 order” which he is “not going to resist.”5

The DPLRC also recommend that where secondary legislation is used for a specific referendum that in all instances the super-affirmative procedure is used and that the consideration period for draft regulations should be set at 60 or 90 days.

The Committee recommends that the Bill be amended so that referendums on constitutional issues must require primary legislation and that all other referendums will ordinarily require primary legislation.

The Committee also recommends that if the Cabinet Secretary wishes to identify specific criteria for other referendums which would not ordinarily require primary legislation, he should lodge the necessary amendments at Stage 2.

Timing Issues

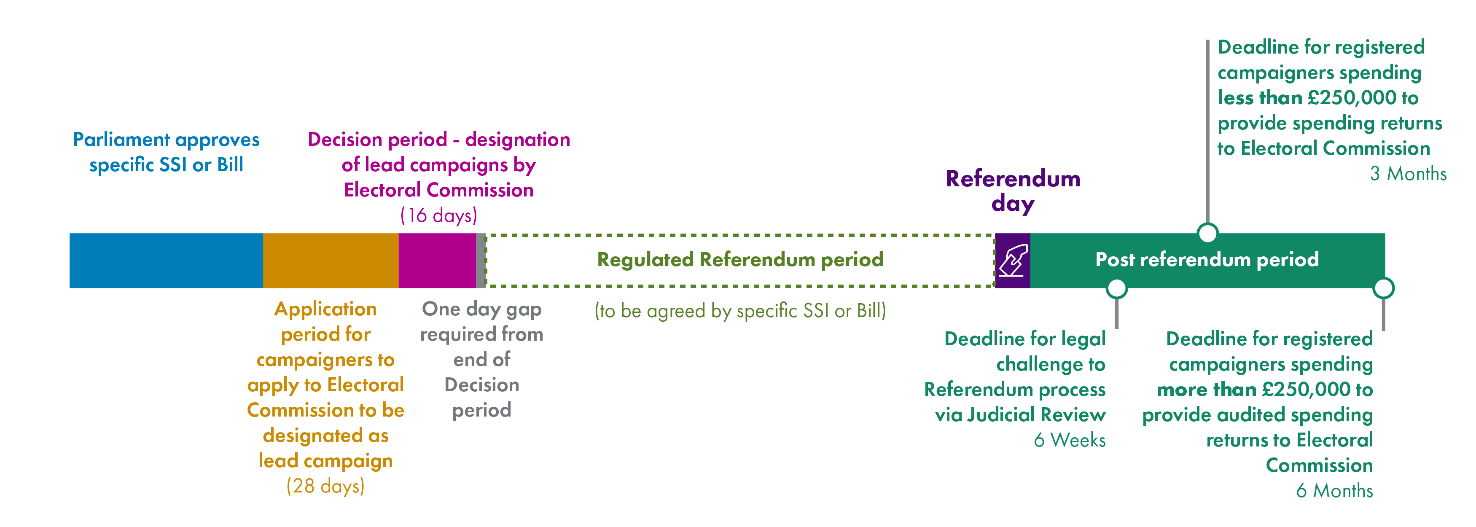

A key theme considered by the Committee is timing issues relating to both the rules for a referendum and the campaign. There are a number of different periods relating to the timing of referendums as follows-

The Gould Principle

Designation Period

Regulated Referendum Period

Figure 1 shows key Referendum phases as set out in the Bill. These are discussed in more detail below.

Figure 1: Key Referendum phases as set out in the Bill (as introduced)  SPICe

SPICe

The Gould Principle

A number of witnesses highlighted the need for a minimum period of at least 6 months between referendum legislation coming into force and being implemented. This is consistent with the Gouldi principle “that electoral legislation cannot be applied to any election held within six months of the new provision coming into force.” The SAA state that it “is important for the effective delivery of a Referendum that the rules surrounding the running of it are clear and in place at least six months prior to the Referendum taking place.” Professor James suggests that the Bill would make that goal more realisable and put Scottish referendums onto firmer ground.1

The EMB states that since the publication of the Gould report “the Scottish Government has always sought to follow this ‘six month rule’ so that administrators, campaigners and electors have sufficient time to plan for the adoption of the new rules.” The EMB’s view is that the Bill “seeks to rationalise the fragmented set of legislation around referendums and in doing so should ensure that the rules are clear well in advance of any referendum.”

The EMB told us that to meet the Gould principle the additional regulations, which will be unique to each referendum, will need to be in place six months ahead of polling day. They explained that we “are talking about what would be ideal and what we would like to be in place in order to deliver the gold standard of an electoral event.” They “want as much notice as possible to ensure that people are fully aware of the rules and what they need to do to take part.”1

The Electoral Commission recommends that “all legislation for any future referendum should be clear (whether by Royal Assent to a Bill or the introduction of regulations to the Scottish Parliament for approval) at least six months before it is required to be implemented.” This is to allow sufficient time to allow campaigners and administrators to “prepare to comply with the rules once they are in force.” But most importantly in the view of the Electoral Commission it “also enables voters to be informed about the issues at stake in the referendum and have confidence in the process leading to a free and fair referendum with a result that has overall legitimacy for the public.” In their report on the Scottish independence referendum in 2014 the Electoral Commission highlighted the benefits of having the legislation being clear nine months before the referendum date.

The Committee explored with witnesses whether the six months minimum period should apply from when the framework legislation is passed or from when the legislation for a specific referendum is passed. Dr Renwick suggested that “if all the rules are in place and the only matters to be decided subsequently are the question and the date, the Gould principle would not be broken by setting a referendum somewhat less than six months in advance of the poll.” At the same time, he also emphasised the importance of allowing voters time to hear from the campaigns, reflect on the arguments and come to their judgment and in his view “doing referendums slowly and carefully is always the better approach to take.”3

Professor Fisher’s view is that “leaving Governments to decide the period between the legislation and the referendum date can cause immense difficulty” and that “Governments will, if they are given the ability to introduce a shorter period between the legislation and the referendum date, use it.” He suggests that “it would be better to be conservative about the time period than to try to rush things through.”4

The Society of Local Authority Lawyers and Administrators in Scotland (SOLAR) told the Committee that “as administrators considering timings, we start from the date of the poll and work backwards” and they “would be looking for that six month period.” 5The SAA agree that “six months from the date of the poll would allow sufficient time for people to be aware that they can register.”6

SOLAR also told us that from “the point of view of an administrator, if the two outstanding matters are the date of the poll and the question, the key issue is the date of the poll.”7 Their view is that as “long as we have the question to go on the ballot paper sufficiently in advance of polling day, the wording of the question is not a concern for us. The decision on that could be made considerably closer to the date of the poll.”6

The Cabinet Secretary was asked by the Committee whether the six month period started with the passing of the relevant primary or secondary legislation. He responded that he is “not absolutely committed to six months. That is the gold standard, but there might be circumstances in which that would change.”9 In his view “the timescales are more to do with the technical ability to deliver than anything else” and he is “not utterly convinced about the time needed.”6

Designation Period

The Bill provides for a period of 44 days for applications to be designated as lead campaigners to be submitted and decided upon before the referendum period begins. Professor Fisher raises concerns about the time allowed between the designation period finishing and the beginning of the regulated referendum period. He suggests that if there is insufficient time between the two periods this can disadvantage some groups particularly if there is competition between groups seeking designation. For example, he highlights the experience of the 2016 EU referendum where there was strong competition for designation on the Leave side, but none on the Remain side. This meant “the designated Leave campaign experienced significant problems attracting donors until was clear that the group would be designated.”

Professor Fisher suggests that to ensure that no side or groups are disadvantaged, it would be prudent to stipulate a minimum period of time between designation and the commencement of the referendum period. He recommends that the designation period should end at least a month before the regulated referendum period.

Regulated Referendum Period

The Bill does not explicitly provide a minimum timescale for the regulated referendum period. PPERA provides for a minimum referendum period of 10 weeks. The designation of lead campaigners is included within this period and is required a minimum of 4 weeks prior to the referendum date. The referendum period for the Scottish independence referendum in 2014 was 16 weeks preceded by 6 weeks for the designation of lead campaigners.

Some of our witnesses raised concerns that the lack of a minimum referendum period in the Bill could result in a truncated campaign period. The IfG’s view is that the lack of a minimum referendum period means that the campaign “could be incredibly short” and this “would have massive impacts on the ability of the campaigners to make their cases, and on public debates about the issue.”1 Dr Renwick points out that although the Bill requires notice of the date of the referendum to be given by Counting Officers at least 5 weeks before polling day “there is nothing to suggest that the referendum period cannot be shorter."

The Electoral Commission supports having the designation period before the start of the referendum period and also supports including a minimum of 10 weeks for the referendum period. Dr Renwick’s view is that while the period for each referendum may be different depending on the topic, the Bill should specify a minimum period between the referendum being called and polling day. He told us that, internationally, “the absolute minimum period that is generally seen as being at the limit of what is acceptable is four weeks”2(consistent with PPERA) but should be considerably longer if the topic has not already been subject to widespread public discussion. His view is that an “absolute minimum of four weeks is fundamentally what is needed, but a minimum of 10 weeks would be better.”3 The IfG recommend that a minimum referendum period should be included in the Bill and cites the Electoral Commission’s support for a minimum period of 10 weeks.

The Cabinet Secretary’s view is that the regulated referendum period “is intended to allow those who are organising the referendum to do so in an efficient and effective manner.” While he “can see no objection to that being specified in secondary legislation” he is “open to having a discussion” and if “the Parliament wants to specify a period in primary legislation…so be it.”4

The Committee agrees with our witnesses that adequate time is required in advance of polling day for two key purposes. First, to allow enough time for the campaign so that voters have sufficient opportunity to be informed about the issues. Second, to allow administrators and regulators enough time to prepare for the referendum.

The approach of using a framework Bill to set out the rules for future referendums is clearly useful in addressing the second of these timing pressures. The provision of generic rules for the conduct of polls and counts gives administrators, regulators and campaigners a high level of certainty and consistency in preparing for each referendum. However, a framework Bill does not, in of itself, address the question of ensuring there is sufficient time for specific referendum campaigns.

The Committee welcomes the Cabinet Secretary’s openness to consideration of having a minimum regulated referendum period in the Bill and recommends that it should be amended to include a minimum period of 10 weeks.

Referendum Questions and Testing

Section 3(7) of the Bill provides for Ministers to specify in subordinate legislation the wording of any question in a referendum without consulting the Electoral Commission if the latter have–

previously published a report setting out their views as to the intelligibility of the question or statement, or

recommended the wording of the question or statement.

The Bill team explained to the Committee that the policy objective of section 3(7) is that “where questions have already been tested and used and are familiar and understandable to voters, there should be no requirement to test again.” This means that the Bill would not require Ministers to consult with the Electoral Commission if they were seeking to use the same question as a previous referendum, for example, the 2014 independence referendum.

Our Adviser points out that International IDEA use the Electoral Commission’s process for question testing as an example of good practice in their handbook on direct democracy. He also highlights the view of the Independent Commission on Referendums that through the role of the Electoral Commission the UK has one of the most rigorous processes for assessing referendum questions.

A number of witnesses raised concerns about section 3(7) of the Bill. The Electoral Commission–

“firmly recommends that it must be required to provide views and advice to the Scottish Parliament on the wording of any referendum question….regardless of whether we have previously published our views on the proposed wording.”

The Electoral Commission advise that their assessment of any proposed question “can take approximately 12 weeks” which includes about 8 weeks for carrying out public opinion research. They suggest that the Parliament “will want to ensure that there is sufficient time to receive and consider our views in order to ensure effective scrutiny of the legislation, whether the question is specified in primary legislation or regulations.”

The Electoral Commission told us that they “strongly believe” that they should be asked to test the question even when that question has been asked before. Their view is that “a formal testing of the question helps to provide confidence and assurance to the voter and to the Parliament that is posing the question and, with regard to the integrity of the process, to establish that the question is clear, transparent and neutral in its setting.”1

The Electoral Commission’s view is that “contexts can change. The context might not have changed, but we will not know that until we do the question testing, whereupon we will give our advice.”2 They also told us that one “of the things that you get from our expertise is confidence in the question” and that “confidence brings acceptance from the voters and campaigners, which allows you to go off and debate the issues rather than the question. That is why we think that question assessment—irrespective of whether we tested the question five, six or 100 years ago—is important.”3

The Committee also discussed with the Commission the implications of their advice not being binding on the Government and Parliament. They responded that “it is fair to say that, if we have given advice, we would hope that it was followed” but “if it was not followed, we would be disappointed but we would respect the democratic outcome and voters would have to make what they could of it. That is the right democratic position.”4

The LSS also have concerns about section 3(7) on the basis that the assumption in the Bill is that “once approved, the wording of the question is suitable for ever.” The IfG point out that if a question is tested multiple times “there will be more experience and more evidence for the Electoral Commission to draw on” and recommend that section 3(7) is removed from the Bill.

Dr Renwick points out that there is no similar provision to section 3(7) within the PPERA and that it “is clear that circumstances change, and the degree to which a question meets the intelligibility test may also change.”5 His view is that fundamentally that has to be allowed for and this provision should be removed or its scope significantly narrowed. Professor Fisher pointed out that “polling companies constantly review their questions because the questions rapidly go out of date in respect of people’s understanding of what they mean.”6 His view is that it “would be sensible to question test on every occasion.”3

Professor Chris Carman told us that “even if the same question is rerun in a relatively short period, some degree of testing is desirable. One might question whether that would require the full 12-week process, but there would be a need for some degree of confirmation or other sort of testing.”8 He also told us that if “a question has been used repeatedly in the polls, we might not require the full 12 weeks, or the full period that Electoral Commission would require to test a full, unique question but we would probably still want to have some independent experts to look at it in order to certify that it was still a fair and reasonable question.”9

The Committee asked the Electoral Commission whether it would always need 12 weeks for the testing of any question in any referendum? They responded that the “short answer is yes” and that one “reason for that is that the bulk of our testing is of public opinion, and that takes time—it takes about eight weeks for the way that we do it.” They added that “they could shave off days or a couple of weeks if we were told beforehand that we were going to do it and we had someone contracted to undertake work on our behalf, but it takes time to give you quality advice.”10

The Committee asked whether having agreement on the question in a referendum is integral to the legitimacy of the process. Dr Andrew Mycock responded that in “principle, yes – I strongly support that position.”11 Dr Toby James’s view is that “the Electoral Commission should be fully involved” and he “cannot see any advantage in limiting its role or the time that it has available to do that.”12

The DPLRC’s view is that their recommendations for the use of either primary legislation or the super-affirmative procedure should allow the Electoral Commission to come to a view on the proposed question.

The Cabinet Secretary told us that he is not against testing referendum questions and that any “new question that arises in a new referendum should, of course, be tested.” But he is “against retesting in circumstances that do not require that” and is “not in favour of confusing people.”

The Committee discussed in detail with the Cabinet Secretary his view that the question used in the 2014 independence referendum is in “current use” and therefore would not need to be tested again by the Electoral Commission in a second independence referendum.

The Cabinet Secretary was asked by the Committee if he was prepared to ignore the weight of evidence which we received including from the Electoral Commission itself which all strongly supports the Commission testing a question even if it has been used in a previous referendum. He responded that he is “entirely in favour of testing the question.”

In relation to the question used in 2014 he told us the “question is current” and “has been asked in more than 200 opinion polls.” His view is that given “it has already been tested by the Electoral Commission and it is in current use, I would want to know why it should be tested again in those circumstances.” He asked the Committee would “that not in itself create confusion?”

The Cabinet Secretary was asked by the Committee whether he was open to amendments to the Bill that would change the criteria for whether or not the Electoral Commission is consulted on the wording of a question. For example, by providing a time limit on the relevance of “a previously published report” in section 3(7)(a). He responded that he is “open to discussion on all aspects of the Bill” including examining whether a definition of a “current” question can be found.

The Committee notes that the policy memorandum states that the Bill takes account of a range of recommendations made by the Electoral Commission in relation to referendums. The Committee also notes that the Scottish Government wants to ensure that all referendums are run to the highest possible international standards and that the results are accepted by all parties. The Committee welcomes this approach and policy objective.

The Committee recommends that the Cabinet Secretary recognises the weight of evidence above in favour of the Electoral Commission testing a previously used referendum question and must come to an agreement, based on this evidence, with the Electoral Commission, prior to Stage 2.

Thresholds

The Committee notes that there are a number of threshold options for establishing the success of a referendum question or proposition which could be used as follows–

Simple Majority – 50% plus 1 of the valid votes cast;

Supermajority - a specified amount higher than 50% of the valid votes cast e.g. two-thirds;

Electorate – a percentage of the total electorate voting in favour of the referendum question;

Turnout – a percentage of the total turnout voting in favour of the referendum question.

An affirmative referendum result may also require more than one threshold, for example, both a turnout and supermajority threshold.

The Bill team explained that “the bill does not set out any provision for additional majority thresholds or other ways of approaching the issue, which means that, according to the bill as drafted, it would be a simple majority.”1 The Bill Team also confirmed that, using the powers in section 2 of the Bill, Ministers could propose threshold requirements or minimum turnout requirements in regulations which would be subject to the affirmative procedure.

Public Petition, PE01754, calls on the Scottish Parliament to urge the Scottish Government to ensure that any referendum advocating constitutional change should have at least a two thirds majority for it to succeed.

Our Adviser states that the convention in recent UK referendums for declaring a winner has been by a simple majority of valid votes cast i.e. 50% +1 vote. This was explicitly stated in the Alternative Vote (AV) referendum legislation although not so in either PPERA or recent referendum legislation such as the 2014 Scottish independence referendum or the 2016 EU referendum.

Dr Renwick and Professor Fisher were asked whether they supported the aims of Public Petition PE01754. Dr Renwick responded that it “would be a very bad idea” and that very “few countries have supermajority requirements for referendums.”2 He also said that to “have a majority vote for a proposition and then be told that that majority does not have any standing inflames passions and does no good to the subsequent political processes.”3 Professor Fisher can “see a case for a supermajority for fundamental constitutional change” but on balance the dual referendum approach proposed by Dr Renwick “is a better safeguard and is more defensible.”4

Our Adviser cites a number of reports5 which address the issue of thresholds. A House of Lords report into referendums in 2010 suggested that there should be a general presumption against electorate or turnout thresholds as a consequence of incomplete electoral registers although recognising that under exceptional circumstances they might be deemed appropriate. The Independent Commission on Referendums indicated that the use of turnout and electorate thresholds was ‘not recommended’ in its recent report. Both also declined to support supermajorities in referendums because of the rarity of their use in UK constitutional politics. The Venice Commission also recommend against both turnout and electorate thresholds.

The Committee does not support the use of thresholds other than a simple majority.

Electoral Registration

Our Adviser points out that there have been some difficulties with the electoral registration process, most recently in the aftermath of the UK-wide introduction of individual electoral registration (IER). In Scotland, this was not implemented until after the independence referendum in 2014.

Dr James told us that it “is widely thought that one of the effects of individual electoral registration has been a reduction in the completeness of the electoral register” and that “research shows that young people and students in particular were negatively affected.”1 The SAA told us that registration “numbers have dropped in the past year but, on the whole, they have remained relatively static since the introduction of IER.”2

Dr James suggests that possibly 8 million people across the UK “are either missing entirely from the electoral register or are incorrectly registered.”3 He points out that this places considerable pressure on electoral officials and that in the run-up to the 2016 EU referendum, the voter registration website crashed because there was such a great volume of traffic.

The Electoral Commission published its findings on the completeness and accuracy of the electoral registers on 26 September 2019.4 The results for Scotland in December 2018 show that parliamentary registers were 84% complete and 87% accurate and local government registers were 83% complete and 86% accurate. In 2015 the Scottish local government registers were 85% complete and 91% accurate. The findings led to an estimate of between 630,000 and 890,000 people in Scotland who were eligible to be on the local government registers but were not correctly registered and between 400,000 and 745,000 inaccurate entries on the local government registers in December 2018.

Our Adviser points out that while electoral registration is crucial to the success of electoral events, the process of individual electoral registration is a reserved matter. He identifies three issues which need to be addressed–

How might we avoid or deal with registration canvass timings conflicting with Scottish referendum periods and their separate registration periods;

If a registration surge collapsed the UK online registration portal during a Scottish referendum, how would such an event be dealt with;

How could Electoral Registration Officers (EROs) avoid having to deal with many duplicate applications to register during a referendum because of how IER is set up?

The SAA explained with regards to the crash of the voter registration system in 2016 that they have been “assured that the UK Government has taken steps to replatform and boost the resilience of the online service.”5 The SAA also pointed out that while local government registration is devolved to the Scottish Parliament, UK parliamentary registration is reserved. They “want to have a system whereby, if people register for local government, they can automatically go on to the parliamentary register as well.”3

Dr Mycock explained to the Committee that the “biggest drop in turnout is actually among 18 to 24 year olds.”7 Options which were discussed with the Committee to address the decline in voter registration included some form of automatic registration, citizenship education and the National Voter Registration Act in the US which requires particular public agencies to ask people to register to vote when they come into contact with them.

The SAA noted that electoral registration in the UK is voluntary unlike in some other countries where it is compulsory. However, they pointed out that “it is not just about the completeness of the register; it is also about accuracy. If we had high registration levels but poor accuracy, we would not have a good register. It is a double-edged thing.”5

The Committee is very concerned about the decline in the completeness and accuracy of Scottish local government registers as recently reported by the Electoral Commission and invites the Scottish Government to respond to the findings of the report.

Political Literacy

A further issue linked to voter registration which the Committee considered is political literacy. The Stevenson Trust for Citizenship note that efforts “by schools in Scotland to ensure political literacy have faced a range of challenges, especially following the adoption of the franchise for 16 and 17 year olds” They highlight “gaps in the availability of Modern Studies programmes across Scotland, lack of clarity about the aims and acceptable approaches in dealing with political questions and political literacy in the classroom, lack of appropriate materials for teaching, concern about professional rules and support from head teachers.”

The Lowering the Voting Age to 16 project team state that voting age reform “in Scotland has had a marked positive effect on youth political interest and activism when compared with young people in the rest of the UK.” However, they also point out that “there is no universal programme of political education to supplement voting age reform, meaning the first cohort of 16-17 year-old voters have not had consistent opportunities to learn about politics and gain the necessary skills to votes.” Dr Mycock from the project told us that about “one third of young Scots take the modern studies curriculum, so they get a good level of political education, but there is clear evidence that sizable numbers of young Scots do not receive appropriate political education.”1

The Lowering the Voting Age to 16 project team recommend that “consideration should be given to how all newly-enfranchised voters in Scotland will have equal opportunities to learn about, engage with and participate in future referenda in Scotland”. They suggest that particular “attention should be given to the provision of political education in schools and colleges, and developing networked opportunities for young people to stand for election in youth councils and represent their peers.”

Professor Carman told us that it “is fairly clear that political literacy is not integrated across the entirety of the curriculum, which means that you have to be careful about how you think about the issue.” He points out that “some 20 per cent of secondary schools in Scotland do not offer modern studies, which means that there is a limit to the extent to which students have access to that subject.”2

The Committee shares the views of many of our witnesses that political literacy is an element of the discussions in relation to modernising our democratic processes. The Committee invites the Scottish Government to respond to the view of one of our witnesses that there is clear evidence that a sizeable number of young Scots do not receive appropriate political education and, if that is the case, what action it is taking to respond especially in light of the possibility of more referendums in the future.

Concurrent Electoral Events

Our Adviser notes that the Bill is silent on whether a referendum might be held on the same day as another electoral event. He also points out that research shows that holding electoral events simultaneously can lead to lower quality electoral processes.1 In his view this was arguably the case in the AV Referendum in 2011 which was held concurrently with devolved and English local elections.

The Association of Electoral Administrators (AEA) explained to us that, for administrators, “having more than one type of event on the same day adds to the pressures and difficulties in relation to resources.” In addition, for voters “there can be some confusion, particularly if the events involve different franchises—people might be able to vote in one poll and not the other, and there are practical issues around how that would be managed.”2

With regards to costs SOLAR told us “the cost of two separate events is higher than the cost of a combined event” but that “the cost of a combined event is significantly higher than the cost of one event.”3

The Cabinet Secretary explained that he is “broadly of the view that there should not be two – or more- electoral events on the same day…but there are sometimes unavoidable circumstances in which it would have to happen.”4

The Committee’s view is that, given referendums are most likely to be called solely on significant issues of major public interest, these should be standalone events. The Committee invites the Scottish Government to seriously consider whether the Bill should be amended to provide for this.

Purdah

The Bill provides for a 28-day purdah period. The Bill team explained to the Committee that this is analogous to PPERA which limit the activities that UK public bodies can undertake in the 28 days before a poll. In relation to the Bill, those provisions legally bind only Scottish public authorities. Any restriction on UK public bodies during a referendum under the provisions of the Bill would need to be done by negotiation with the UK Government, as happened with the 2014 independence referendum.

Our Adviser points out that the issue of purdah has been controversial in recent referendums. This includes the 2014 independence referendum when there was concern that the 28 day period was too short since it permitted government publication for all but the last 4 weeks of the campaign. Our Adviser also points out that there was considerable concern during the 2014 referendum about statements from UK wide public bodies during the campaign including during the purdah period.

Dr Renwick identifies two major problems with the 28 day approach. First, that in a “referendum on a subject as large as independence or Brexit, all sorts of normal government communications may be caught by it.” Second, given that campaigns begin well before the purdah period “the rules do not prevent potentially influential government interventions in the campaign.” He recommends that the current approach is “replaced with a ‘long and thin’ provision, limiting the prohibition only to materials that specifically seek to intervene in the campaign, but extending this to cover the whole of the natural campaign period.” The material covered would be based on the sorts of communication that count towards expenses for registered campaigners while the period covered would be the regulated referendum period.

Professor Fisher takes a different view. He told us that he has “never been entirely comfortable with the idea of excluding Government from the referendum process” and “it seems slightly perverse that a Government that wishes to propose a referendum should not be able to have a say in it.”1

The Electoral Commission raise concerns about voter confidence if there is a perception that the rules on spending do not apply equally during the referendum period. They point out that whereas referendum campaigners must work within statutory spending limits, government and public authorities may spend “potentially significant amounts of public money promoting their preferred outcome as close as four weeks before polling day.” The Electoral Commission recommend that purdah should apply during the whole of the referendum period but that the scope of the restriction could be redrafted to apply to more specific types of activities or issues.

The Cabinet Secretary’s view is that the “purdah period should not be extended lightly or ill-advisedly” given that this would disrupt normal business. He also points out that a referendum is not the same as an election in which a “Government might be tempted to use pork-barrel politics of various types in order to influence the vote.”2

The Electoral Commission also highlighted the inability of the Scottish Parliament to legislate to restrict the activities of other governments in the UK. In their view, in the absence of any statutory limitations, where the subject of any particular referendum is a matter of interest to other governments in the UK, they would expect and encourage voluntary compliance with the same restrictions on the publication of referendum material, as was the case for the 2014 independence referendum.

The Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body (SPCB) provided written views on the impact of the purdah provisions in the Bill on parliamentary business and states that it “accepts and endorses the fundamental importance of prereferendum restrictions to ensure that” it “adheres to its obligation of strict impartiality and does nothing in the immediate run-up to a referendum that might influence the outcome of the vote.”

The SPCB recommends that it would be appropriate for paragraph 27(3)(b) of schedule 3 to the Bill (i) to be brought up to date, and (ii) to be adjusted to ensure, or to provide a mechanism to ensure that the exemption for publications in the normal course of parliamentary business is sufficiently future-proof to allow for future developments which are within the spirit of the provision.

The Committee notes that one of the major challenges in relation to purdah is the restrictions it places on the types of activities UK public bodies can undertake during a referendum under the provisions of the Bill. For example, if there was a referendum on a health issue in Scotland whether there would need to be restrictions on NHS England and other UK and devolved health public bodies. The Committee recommends that the necessary negotiations with the UK Government and, if necessary, other devolved governments should be carried out at the earliest opportunity once the enabling legislation has been passed.

The Committee supports the SPCB’s proposed amendments to the Bill in relation to purdah.

Conduct of Polls and Counts

Chief Counting Officer (CCO)

The CCO would have responsibility for the delivery of the referendum in terms of polling, postal voting and the count. The Electoral Commission also recommend that the Bill should be amended so that–

Scottish Ministers should be required to consult the Electoral Commission before removing a CCO in the circumstances outlined in the Bill or appointing anyone to the CCO role;

The CCO should consult the Electoral Commission before issuing any directions to COs and Electoral Registration Officers (EROs) regarding their functions under the legislation;

Sufficient time should be provided for the CCO to draft guidance ahead of COs needing to comply with it.

The EMB stated that the key concern of CCOs “would be clarity with respect to the designation of permissible participants so that COs are able easily to engage with them as appropriate during the campaign, then at events such as postal vote processing, polling and at the counts.”

Appointment of Counting Officers

The Bill provides that ahead of each referendum the CCO must appoint in writing COs for each local government area. The Electoral Commission’s view is that in order to reduce uncertainty and enable effective planning the Bill should designate the Returning Officer for each local government area as CO in any referendum.

Observers

The Bill requires the Electoral Commission to lay before the Parliament a new Code of Practice on the attendance of observers at the proceedings of each referendum. The Electoral Commission recommend that to ensure consistency the Bill should allow the existing local government election code for observers to apply to referendums.

Our Adviser notes that the Bill provides for Electoral Commission accredited observers to observe various procedures under a code of conduct. However, he points out that in the list of individuals permitted to attend polling stations, attend postal vote issuing and openings, and the count, accredited electoral observers are not explicitly identified. His view is that in order to avoid any confusion, the Bill could explicitly list accredited electoral observers as permitted to attend polling stations, postal vote issuings and openings and the count.

The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government gives careful consideration to the recommendations of the Electoral Commission regarding the conduct of polls and campaigns and sets out its views in its response to this report.

The Committee also recommends that the Scottish Government should give careful consideration to explicitly listing accredited electoral observers as being permitted to attend polling stations, postal vote issuings and openings and the count.

Campaign Rules

The Policy Memorandum states that the aim of the campaign rules in the Bill “is to create a level playing field between campaigns supporting each potential outcome of a referendum.”1

Imprints on Referendum Campaign Material

The Bill requires both printed and non-printed referendum campaign material to include an imprint identifying who is responsible for it. This is consistent with the independence referendum in 2014. The Committee’s adviser points out that during the 2016 EU referendum the imprints on some printed campaign material was vanishingly small and difficult to read. He points out that PPERA includes a provision under such circumstances for the Secretary of State, after consulting the Electoral Commission, to specify what details must be included in any such material in order to comply.

The Electoral Commission welcome the inclusion in the Bill of the requirement to include an imprint on non-printed referendum material but also identify several areas where it could be amended to ensure the scope of the imprint requirement is as intended. First, the Bill should be amended so that individuals advocating or expressing an opinion about a particular referendum online are not unintentionally required to provide an imprint.

Second, the Commission has concerns that the provision within the Bill to include an imprint in non-printed material unless it is not reasonably practical to do so would “give campaigners an easy excuse not to include imprints.”

The Electoral Commission told us that having “the exception is a bad idea, because it creates a hole in the system and means that there is no incentive for the social media companies to include the imprint.” They highlighted their work with some of these companies which “shows that it is absolutely practical in all forms of digital campaigning for there to be imprint information by clicking on it or other means.” They told us it “is our strong recommendation, which we made in our written representations and are repeating today, that there is no need for the exception.”1

Dr Renwick’s view is that while the Bill includes a slight addition to the wording of the 2013 referendum it “still does not make it clear that someone who is expressing a personal view and not being paid for it does not have to provide an imprint.”2His view is that this needs to be clarified in the Bill.

Professor Fisher told us that “the need for digital imprints is quite clear” although online conversation is “something that goes beyond what one could reasonably regulate.” His view is that “it is difficult to capture things like organised Twitter campaigns” and legislation should not seek to do so given that “in many ways it is no different from simply trying to regulate ordinary conversational campaigns.” He cautions that there “is a real risk of regulation falling into disrepute if it tries to cover everything but ends up doing something very badly.”3

The IfG told us that “there is a distinction to be made between paid political advertising and organic advertising” and that the former should definitely contain an imprint and the latter which is “shared peer to peer on social media” should not. They recognise that “there are difficult trade-offs to be made about the regulatory burden” and we should learn as many lessons as we can from the requirement for digital imprints in the 2014 independence referendum. The LSS highlighted the expectation that the UK Government “will make a technical proposal for a regime on digital imprints later this year” and recommend that the Scottish Government takes it into account.

Dr Mycock told us that it “may well be that this is less a question of regulation and more a question of education” and that digital education of young people has “been largely overlooked.”4 Dr Reidy’s view is that, ultimately, “you will have to have direct co-operation with online platforms, and you will have to rely on those platforms adhering to or complying with any regulations, in full awareness that they are transnational by their very nature.” For example, she highlights the agreement between the European Commission and the social media platforms in advance of the European Parliament elections. A code of conduct was agreed with the quid pro quo that if the platforms did not engage with it “ultimately the Commission would legislate.”5

The Cabinet Secretary told us that “it is highly desirable for electronic means of communication to be subject to the same restrictions as print material” and that the Scottish Government “continue to discuss the matter with the Electoral Commission, among others.” Scottish Government officials explained that they are trying to make sure that they do not capture individuals expressing their personal views and that the Bill “is very much about capturing publications that are intended for campaigning.”6

The Committee supports the recommendation of the Electoral Commission that the Bill is amended to remove "unless it is not reasonably practical to do so" from the requirement to include an imprint in non-printed material.

The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government gives careful consideration to the other recommendations of the Electoral Commission in relation to the scope of the imprint requirement and sets out its views in its response to this report. The Committee also recommends that the Scottish Government provides clarification as to the intended scope of the Bill as introduced in relation to non printed referendum campaign material.

The Committee also recommends, as highlighted by one of our witnesses, that the Scottish Government should take account of the UK Government’s technical proposal for a regime on digital imprints.

Donations

Schedule 3, Part 5 of the Bill sets out provisions for the control of donations and includes detailed rules to ensure that they “are declared and administered appropriately to ensure that the campaigns are run with fairness and transparency.”1 The Bill adopts the UK wide definition of permissible donors set out in PPERA which is the same approach as the 2014 independence referendum. Permissible donors are defined in the Bill as-

individuals registered on the electoral register anywhere in the UK;

companies registered under the Companies Act, incorporated in the EU and that conduct business in the UK;

registered parties;

trade unions;

building societies;

limited liability partnerships;

friendly societies;

unincorporated associations carrying on business or other activities wholly or mainly in the UK and having their main office there.

In general terms, the rules in the Bill define what donations are allowed, both by description and monetary value (or a determination of monetary value), who is allowed to make a donation, and what a permitted participant must do to record and report the donations of over £500 which they receive. Donations under £500 are not regarded as donations to a permitted participant.

Outside the UK

The Electoral Commission state that it is important that there are “appropriate safeguards to prevent funding of referendum campaigners from non-UK sources.” They suggest, therefore, that the definition of permissible donors in the Bill should be amended to ensure that a company has to make enough money in the UK to fund its donation or loan. Professor Fisher’s view is that the “essential principle is that donations should be made by persons who are registered to vote in the United Kingdom.” He was asked by the Committee whether there is a case for going further in the Bill in requiring checks on where donations come from. He responded that there may be a case for lowering the threshold for reporting donations, although there is a balance to be struck between effective regulation and overregulation.

The Cabinet Secretary was asked by the Committee whether there is scope for the Bill to go further in preventing the use of overseas donations. He responded that he was not sure and that this “might lead us into dangerous areas” but he “will consider the issue.”1

The Committee recommends that the Scottish Government should give careful consideration to the Electoral Commission’s recommendation on donations from outside the UK and sets out its views in its response to this report.

Checking Permissibility

As noted above permissible donors include individuals registered on the electoral register anywhere in the UK. Our Adviser notes that this raises an important issue in relation to checking permissibility given that campaigners would need to have access to electoral registers across the UK. However, the Bill only provides for access to the Scottish local government registers. This raises the question of how campaigners can ensure access to full UK registers to ensure the permissibility of donations.

The Policy Memorandum states that if campaigners “receive a donation from an individual who is not on the local government register, they will be able to check other electoral registers operating in Scotland and the rest of the UK through the normal public access routes.” Some of our witnesses questioned whether this level of access is sufficient. The Electoral Commission states that the Scottish Government “will need to find a practical solution to this issue in order to enable campaigners to fully comply with their legal duties.”

The Electoral Commission told us that in the 2014 independence referendum the problem in relation to checking permissibility was that campaigners could not get the registers for people from Northern Ireland, Wales or England, who were allowed to donate. This meant that they had to trust that the people who gave them money were on the register. The Commission explained that they “advised people to use a workaround: to go and see the local ERO’s register or to get the donor to give them a letter of comfort from their local registrar saying that the donor was on the register.”1 They recommend that each Government across the UK should work together so that permitted participants can obtain the registers.

Professor Fisher highlights verification difficulties arising from electoral registration data being held in a range of formats at local authority level. His view is that accessing this data presents “significant logistical challenges and costs to campaign groups” and especially new campaign groups as demonstrated in the 2016 EU referendum. He recommends the creation of a “nationally-held database of all those on the electoral register.”

The SAA explained that there are “four electoral management systems in use in Scotland,” the “basic data is the same” and it “is perfectly possible to produce a standard export from them.”2 Their view is that while there is an argument for a more standard format for data export they are not certain that a national database would provide that and a national database would also raise General Data Protection Regulation issues. They would be happy to consider standardising the format at a local level but highlight that this work would require additional funding. The Electoral Commission explained that “three major providers of register software are used in Scotland” and that a “national standard whereby they can all talk to one another would be a good thing.”3

The Committee asked Professor Fisher whether he agreed that there are real problems of perception about how national databases potentially change the relationship between citizens and the state. He responded that he accepted there is a danger of that but as “a minimum, you could ensure that all local authorities keep data in the same format, to enable the merging of that data.”4 As to whether this would be reasonably easily achieved, Professor Fisher’s view is it “would mark a fundamental shift from local authorities effectively doing what they like to the Electoral Commission running elections more centrally.” While he recognises there has been some resistance to this shift, his view is it “does not seem unreasonable to insist that the registers, even if they are kept at local authority level, are in the same format, because they are critical to compliance in relation to donations.”5

The Cabinet Secretary was asked by the Committee whether he supports having a Scotland-wide or UK-wide electoral register. He responded that “it could be done, but, at the present moment, it would not be easy or speedy to achieve, and it might get in the way of a lot of other things that are happening.” He highlighted a number of proposed changes to electoral law currently being considered by the Parliament and he “does not want to add a further burden.”6

The Committee recognises the challenges in providing a Scotland-wide electoral register but asks the Scottish Government what consideration has been given to standardising the data format for electoral registers at a local level so that they can all talk to one another so that a common format might make permissibility checking easier for campaign organisations.

Reporting

The Bill requires registered campaigners to submit donation reports at four points during the referendum period which is the same as the requirements for the 2014 independence referendum. Dr Renwick points out though that this is “strikingly different” from general elections where weekly reporting is required. His view is it “is not obvious why such a difference should exist” and that “weekly reports offer greater transparency than monthly reports.”

The Bill requires permitted participants to report to the Electoral Commission on their finances during the campaign within three months of polling day setting out full details of expenses and donations. For those who spend over £250,000 they are required to submit an auditor’s report on their spending to the Commission within six months of polling day.

The Electoral Commission told us that “the Bill is good and sets out categories for which spending has to be reported, but it does not yet suitably specify the nature of some of the spending in the categories, or digital campaign spending, which is obviously a major activity and spend these days.” In their view “it is perfectly practical for there to be more detail on the spending so that the public can also see what it has been spent on.”1 They recommend amending the Bill so that campaigners would be required to include this information in their spending returns on the basis that this is proportionate and does not impose an unreasonable burden.

The Commission were also asked whether staffing costs should be reported. They responded that “modern campaigning takes place with people sitting at call centre desks and telephoning people, and through digital campaigning, which requires staffing, so it involves considerable expenditure.” In their view it “seems odd that that is not part of the reporting regime, and that we cannot see what money is being spent there.” They suggest that the “staffing costs of campaigning should come in under the rules and be reported.”2

The Commission also raise concerns about the amount of time allowed for those campaigners spending over £250,000 to provide an auditor’s report and point out that once they have carried out compliance checks the information would not be available until around 9 months after polling day. Their view is that this “information needs to be available to voters and us as soon as possible after a referendum, while it is still a live issue.” They recommend amending the Bill to reduce the deadline for those that spend more than £250,000 to less than six months.

The Committee invites the Scottish Government to give serious consideration to the Electoral Commission’s recommendations in relation to reporting requirements and sets out its views in its response to this report.

The Committee asks the Scottish Government to explain in more detail why the proposed reporting requirements for referendums are different from the requirements in general elections where weekly reports are required.

Pre-poll Reporting

The Bill provides for a pre-poll reporting requirement for permitted participants. Donations over £7,500 received in advance of the regulated referendum period or them becoming a permitted participant are required to be reported. Our Adviser points out that well organised campaign groups may be accepting donations and spending well in advance of any regulated referendum period.

The Electoral Commission also state that the rules on donations only apply to campaigners after they have registered with them unlike political parties where the rules apply year-round. The Commission points out that this “means that voters will not have information about who has backed campaigners financially before the start of the regulated [referendum] period.” They recommend an amendment to the Bill which would “ensure that new campaigners should be required to submit a declaration of assets and liabilities over £500 upon registration.”

Our Adviser points out that campaign groups are likely to be spending on data in advance of any major referendum. The Electoral Commission recommend that the declaration of assets at registration should “include an estimate of the costs the campaigner has incurred when buying or developing the data they hold when they register.” Our Adviser suggests that this would be a sensible step to address in the Bill.

The Committee invites the Scottish Government to give serious consideration to the recommendations of the Electoral Commission in relation to campaigners’ declaration of assets at registration and sets out its views in its response to this report.

Campaign Spending Limits

The Bill sets out spending limits for different types of permitted participants as set out in Table 1 below. The Bill also includes provision for secondary legislation to vary specific sums in the Bill, including to increase spending limits in line with inflation.

Table 1: Spending limits

Type of Participant Spending Limit Designated Organisation £1,500,000 Political Party represented in Scottish parliament (based on the 2016 Scottish Parliament election results). SNP £1,332,000Scottish Conservatives £672,000Scottish Labour £630,000Scottish Liberal Democrats £201,000Scottish Greens £150,000 Other permitted participant £150,000 Unregistered campaigners £10,000 Source: Policy Memorandum, Para 65.

Professor Fisher suggests that the spending limits for permitted participants and unregistered campaigners “present significant challenges in ensuring that campaign spending on each side of a referendum is as equitable as possible.” His view is that given the relatively high spending limits for permitted participants and unregistered campaigners “it is arguable that the spending limits for the designated campaigns…are rendered effectively meaningless.” Furthermore, the absence of a limit on the number of participants who can apply to be registered “means that in effect there could be a significantly uneven contest between the two sides.”

Professor Fisher also points out that the limit for unregistered campaigners is the same as for UK-wide referendums despite the significant difference in the size of the electorate. He suggests that there “is therefore a further risk of multiple non-registered campaigns challenging the primacy of the designated ones.” His overall view is that the “spending limits are not fit for purpose.” He recommends that the limits for registered and non-registered participants “should be reduced significantly to ensure that the designated campaigns are paramount in any referendum contest and that spending limits are meaningful.”

However, our Adviser points out that in relation to the 2014 independence referendum the spending of the lead campaigners was considerably more than the combined spend by all other campaigners. The Electoral Commission’s figures show that the lead campaigners both spent around 95% of their limit while the combined spend by all other campaigners was less than half of this on the no side and around a quarter on the yes side.

A further issue raised by the Electoral Commission regarding campaign spending limits is the costs of ensuring that campaign material is also produced in accessible formats. In their view these costs should not be included within spending limits thus making it easier for campaign material and events to be more accessible to voters with disabilities.

The Committee invites the Scottish Government to respond to the view of one of our witnesses that the campaign spending limits are not fit for purpose and should be reduced significantly to ensure that the designated campaigns are paramount in any referendum contest and that spending limits are meaningful.

The Committee supports the recommendation of the Electoral Commission that the costs of producing campaign material in accessible formats for people with disabilities should not be included within spending limits.

Enforcement

The Bill limits the maximum amount the Commission could fine campaigners for breaches of referendum laws to £10,000 for individual offences.

The Electoral Commission’s view is that it “is important that the level of financial penalty for breaches of the law is high enough to have a deterrent effect that encourages compliance by all campaigners.” They explained to the Committee that “by definition, when we investigate and we find breaches, we have to apply proportionate fines” which means they “cannot always apply the maximum fine.”1

They also explained that in other “regulatory fields, for example in the financial world and in the data protection world, the fines that are set to deter people from breaking the rules have gone up” and that “political regulation is now out of line with other regulation.” They draw a parallel with the UK Information Commissioner’s Office whose powers to fine people have increased from £50,000 to £500,000.

The Electoral Commission accept that “fines have to be proportionate, but we think that, where appropriate, it should be possible to set a higher level of fine.” While they propose a maximum fine of £500,000 in their written submission they told us that we “are not saying that it needs to be set that high, but we are definitely saying that the maximum amount needs to be higher than it currently is.”1

The Committee asked the Electoral Commission whether fines were an effective deterrent to campaign groups in a referendum given their transitory nature. They responded that “the responsible person still has the duty to have complied with the law. Although the organisation might disappear, the legal responsibility continues.”3 At the same time they recommend that they should be given more powers so that they “are able to get information more quickly from campaigners and others involved in elections and so forth, so that we can act more quickly.”

The Cabinet Secretary was asked by the Committee whether he thought that a maximum fine of £500,000 was reasonable. He responded “absolutely” and “if the Electoral Commission wants to set a level of £500,000, I am easy about it.”4

The Committee invites the Scottish Government to respond to the evidence from the Electoral Commission in relation to its enforcement powers and sets out its views in its response to this report.

Public Funding

The IfG notes that unlike PPERA the Bill makes no provision for public funding for designated campaigners which while consistent with the legislation for the 2014 independence referendum is “one of the notable differences between the Bill and the UK regulatory framework.”1 They point out that some “referendums might not attract levels of donations that are high as those that, say, an independence referendum would attract.” In their view this “would be particularly problematic if a lot of business groups and political parties were all aligned to one side in a referendum, in which case the other side might struggle to raise funds and put its case to the public.”2

The IfG were asked whether allowing public funding would lead to a negative public reaction. They accepted that this is a risk but that this “needs to be balanced against the potential for having a poor quality of debate in future referendums”1 but they do not have a firm view on the matter.

The Cabinet Secretary was asked whether there should be a provision for public funding for referendum campaigns in the Bill. He responded that he “would be reluctant to commit public money” although he “would not rule out such funding absolutely.”4

The Committee’s view, as noted above in relation to concurrent electoral events, is that referendums are most likely to be called solely on significant issues of major public interest. It is also likely that there will be competing views which is why a referendum would be needed to resolve the issue. On this basis the Committee does not believe that, at this stage, there is sufficient evidence to support amending the Bill to include a provision for public funding.

Role of the Electoral Commission

The Bill provides the Electoral Commission with responsibility for promoting public awareness and understanding of each referendum in Scotland. They explained to the Committee that one “focus is on encouraging people to register, another is on encouraging hard-to-reach groups to register, and another is on getting people to protect their vote against fraud and so on.” They also recognised that there may be a new strand “which is about helping people to think a bit harder about who is trying to influence them.”1

The Committee also considered whether the Electoral Commission could have a role during a referendum campaign in providing impartial information to voters. Dr Reidy explained to us that in “Ireland, the Referendum Commission provides objective, factual information that is not disputed” but that there “are limits to what information it can provide, because there will still be areas where there are substantive elements of contention.” She states that there is a lot of research evidence that shows that the Referendum Commission’s “information is highly valued” and that it “is very much trusted by the voters.”2

Dr Mycock’s view is that in “some senses there is an important requirement for an independent body to provide information for the electorate about the context, issues and consequences of any referendum.” Professor Carman’s view is that if the Electoral Commission “is in charge of providing fair, balanced information, one might separate that from the regulatory function, which has already been separated from the administering function.”3

The Electoral Commission recommends that the duty to encourage participation within the Bill should be extended to cover EROs as well as COs at future referendums. They also recommend that EROs should be exempt from restrictions on central and local government publishing promotional material.

The Cabinet Secretary was asked whether the Electoral Commission should have a wider role in providing objective information during a referendum campaign. He responded that the Commission is “right to be cautious about getting into a situation in which it is the arbiter of truth, because that is not its role.”

The Committee supports the provisions in the Bill which set out the Electoral Commission’s role in promoting awareness and understanding of each referendum in Scotland. The Committee does not support extending this role to include providing objective information during a referendum campaign.

Electoral Commission’s Expenditure

The Bill provides for any expenditure which the Electoral Commission incurs under this legislation to be reimbursed by the SPCB. Under the Bill the SPCB has an obligation to pay whatever expenditure the Commission incurs. This includes where expenses incurred exceed or are otherwise not covered by a budget or revised budget that has been approved by the SPCB. The SPCB explained to the Committee this obligation is different from its equivalent duties to fund other independent bodies where it has a power but not an obligation to pay those expenses. The SPCB’s view is that it would be appropriate for the provisions in the Bill for the Electoral Commission’s expenditure to be in line with the SPCB’s duties for the other independent bodies it funds. The Electoral Commission indicated to the Committee that they “have no problems” with the SPCB’s recommendation.1

The Committee supports the SPCB’s recommendation that the Bill should be amended to provide for SPCB funding of the Electoral Commission’s expenditure to be in line with the SPCB’s duties for the other independent bodies it funds.

Powers to Modify