Equalities and Human Rights Committee

Stage 1 Report on United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (Incorporation) (Scotland) Bill

Summary of conclusions and recommendations

Recommendation on the general principles of the Bill

The Committee unanimously recommends to the Parliament that the general principles of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (Incorporation) (Scotland) Bill be agreed to.

Support for the Bill

The Committee gathered evidence from individuals and groups who would benefit or be impacted by the legislation, for example, children and young people’s groups, human rights experts, public authorities, equality organisations, academics, legal experts and legal practitioners. Evidence received by the Committee shows widespread support across the range of stakeholders for the incorporation of UNCRC into Scots law and the strengthening of children’s rights in Scotland.

Evidence did however highlight some specific areas of the Bill where the Scottish Government could improve upon or strengthen.

The Committee asks the Scottish Government to set out how it intends to work with stakeholders, including children and young people, to develop the guidance to accompany implementation of the Bill. Also, the Committee asks the Scottish Government for its views on how it will address in guidance the transition from childhood into adulthood.

Part 1 of the Bill

Method of incorporation of the UNCRC requirements

In considering the method of incorporation taken by the Bill, the Committee has considered all the information at its disposal, including the Scottish Government’s consultation. On balance the Committee believes the Bill’s approach is appropriate. However, as the Committee responsible for scrutinising the age of criminal responsibility legislation at Stage 1, we have some sympathy with the point being made about the potential risk of incorporation being seen as having achieved the minimum UNCRC standards.

In our human rights report, Getting Rights Right, the Committee emphasises the need to also identify opportunities to advance rights. The Committee therefore recommends the Scottish Government should, in i) its guidance to public authorities on the Bill, ii) any supporting documentation for conducting Child Rights and Wellbeing Impact Assessments and, iii) when preparing and reviewing its Children’s Rights Scheme, make it clear that opportunities to advance children’s rights should form part of the process.

Interpretation of the UNCRC Requirements

Section 4 of the Bill sets out that a court or tribunal may take into account the texts of the UNCRC and the two optional protocols that have not been incorporated (e.g. Preambles), when they are determining a case.

The Committee heard strong views from many witnesses that section 4 should be amended to include additional sources.

The Committee understands that sometimes too much information could restrict practical implementation and make the Bill less effective. In this case however, the Committee is persuaded by the arguments that other sources of interpretation should be included on the face of the Bill, as these sources would not be determinative, and the list of sources would be non-exhaustive. This approach is attractive to the Committee because of its transparency and because it demonstrates to public authorities tasked with implementing the Bill the variety of sources that may be used by courts and tribunals. This, the Committee considers, would lead to a better understanding of the culture change required, where UNCRC rights are understood to be ever developing, inter-related and indivisible.

The Committee recommends the Scottish Government amends the Bill so that courts and tribunals ‘must’, rather than ‘may’, take into account the whole of the text of the UNCRC and the two optional protocols, when they are determining a case.

In addition, the Committee recommends the Scottish Government brings forward amendments at Stage 2, so that courts and tribunals ‘may’ look at a range of other UN materials, as listed: treaty body decisions; other relevant optional protocols (including opinions under the third protocol); general comments, concluding observations, and recommendations (UNCRC and other relevant international treaties); comparative law; and reports resulting from Days of General Discussion.

Part 2 of the Bill

Need for a ‘due regard’ duty

It was argued by some that introducing a ‘due regard’ duty on public authorities, in addition to the compliance duty, would strengthen the Bill.

The Committee notes the good arguments for inclusion of a ‘due regard’ duty. Nevertheless, it is not convinced this would be the best approach. We believe the duty to not act incompatibly is clear and robust. Adding a further layer of complexity, to what is already a novel Bill, runs the risk of diluting the Bill’s impact through lack of clarity. The Committee does, however, acknowledge the need for further stimulus around public authorities taking a proactive approach and this is addressed throughout this report.

Inclusion of the Scottish Parliament as a public authority

While there has been support for the inclusion of the Scottish Parliament as a public authority, detailed discussion on the matter has been limited. In principle, the Committee would like to see the Scottish Parliament included within the definition of a public authority and therefore subject to the duty not to act in a way which is incompatible with the UNCRC requirements. Currently however, there appears to be insufficient evidence on the matter to take a definitive view. We are also conscious it would be unhelpful for the Bill to be judicially reviewed, potentially delaying commencement.

The Committee asks the Scottish Government for an update on the officials’ discussions to inform Stage 2.

A ‘hybrid’ public authority

The Committee has heard significant evidence that the definition of a public authority, as set out in the Human Rights Act 1998, on which this Bill’s provisions are based, is being interpreted by the courts in a way that would be contrary to the spirit and intention of this Bill. We recognise this issue could either be addressed by amending the definition in the Bill or by providing absolute clarity on this point in the guidance issued to public authorities. The latter option, the Committee notes, does not stop the courts from interpreting the definition more narrowly over time.

The Committee recommends the Scottish Government undertakes a further investigation, with the involvement of the main stakeholders, as to how the definition could be tightened to avoid similar issues arising as those experienced with the Human Rights Act 1998 and provide an update to the Committee in advance of Stage 2 proceedings.

Court processes and remedies for breach of the duty on public authorities

The approach in Part 2 of the Bill means that existing courts and tribunals (as opposed to a new court or tribunal) would be used, and, for the most part, no new judicial remedies are created by the Bill. Several submissions raised issues around the ability of children to obtain access to justice within existing systems, which were described as “designed by adults, for adults”.

The Committee asks the Scottish Government how it intends to take account of the implications of the Bill for legal aid and for this information to be made available to the Committee in advance of Stage 2.

The Committee asks the Lord President in advance of Stage 2 to reflect on this evidence and to provide further details on progress being made on a child-friendly court system in preparation for the Bill.

Effective Remedies

It is not clear to the Committee that Part 2 of the Bill does enough to ensure that the judicial remedies that can be provided by courts and tribunals will be effective in practice. For example, will they focus on what a child or young person might want, or ensure changes in the public authority concerned for the benefit of other rights holders in future.

The Committee asks the Scottish Government to amend the Bill to ensure the rights holder has a right, under section 8 of the Bill, to an effective remedy. For example, section 8 could be amended to require courts to issue a remedy which is ‘just, effective and appropriate’. Furthermore, the Committee asks the Scottish Government to amend the Bill to define what constitutes an effective remedy.

As part of its consideration of what constitutes an effective remedy, the Committee asks the Scottish Government for its views on the use of structural interdicts to address systemic rights breaches in advance of Stage 2.

Also, the Committee asks the Scottish Government to amend the Bill to require courts and tribunals to ask for the child’s views on what would constitute an effective remedy in their case. The Committee is aware of precedent in other legislation e.g. section 11 of the Children (Scotland) Act 1995 (as amended by the Children (Scotland) Act 2020 (when it comes into force)).

Who can bring court proceedings?

Section 7 of the Bill says that a person, defined as an individual or organisation, can bring court proceedings in respect of an alleged breach of the (section 6) duty on public authorities. The Scottish Government intends that section would interact with existing law which can require the individual or organisation to have ‘standing’. In other words, that that individual or organisation has satisfied a specific test which determines whether they can bring a court action in the individual case.

The Committee understands that the Scottish Government’s policy intention is that, in judicial review proceedings on the UNCRC requirements, the test of ‘sufficient interest’ would determine which individuals and organisations have standing to raise court proceedings. The Committee asks the Scottish Government to provide greater clarity on its policy intention on the face of the Bill. In particular, the Committee asks the Scottish Government to bring forward an amendment at Stage 2, so that section 7 refers explicitly to the test of ‘sufficient interest’.

Time limits for bringing court proceedings

The Committee notes there have been mixed views on whether it is correct to exclude the period when a young person is under 18 when calculating the time limits for raising court proceedings under section 7 of the Bill. The principal view is that the approach is beneficial, and child focused. As such, the Committee is content with the time limits as drafted in section 7. The Scottish Government’s commitment to consider any arising issues is welcomed by the Committee.

Part 3 of the Bill

Children’s Rights Scheme (the Scheme)

Ministerial discretion and the contents of the Scheme

Sections 11-13 of the Bill require Scottish Ministers to publish a Children's Rights Scheme (the Scheme) to report on compliance with the UNCRC requirements, to be reviewed and reported on annually.

Several of the responses to the call for views and oral evidence suggest that the language at section 11(3) of the Bill needs to be strengthened. While the Bill states the Scheme “may” include certain arrangements around children’s rights, stakeholders have called for this to be changed to “must”.

The Committee asks the Scottish Government to strengthen section 11(3) by amending the wording from ‘may’ to ‘must’ in the Bill.

Additional Scheme requirements

The Committee has heard there should be changes to the content of the Scheme on the face of the Bill, including, for example, the addition of the protected characteristics and vulnerable groups, access to advocacy, legal aid, human rights education and a child-friendly complaints mechanism. Also, arrangements for reporting and the involvement of children and young people in the Scheme.

The Committee asks the Scottish Government, in advance of Stage 2, to set out whether the Children’s Rights Scheme will be strengthened to include any of the additional requirements identified by stakeholders as set out above.

Child Rights and Wellbeing Impact Assessments (CRWIAs)

A number of witnesses raised concerns that Ministers have discretion in relation to decisions of a strategic nature. The Committee recognises there may be a need to retain some discretion around CRWIAs and strategic decision making, however we do not consider the case for this has been fully set out by the Scottish Government and a lack of transparency around how this would be used in practice remains.

The Committee has deliberated over stakeholder concerns regarding Ministerial discretion around carrying out CRWIAs in relation to decisions of a strategic nature. The Committee therefore asks the Scottish Government to remove Ministerial discretion at section 14(3) of the Bill. If this is not removed, then the Scottish Government must provide clear information around what decisions of a strategic nature would and would not be considered appropriate for a CRWIA to be carried out.

Mandatory CRWIA duty on all public authorities

The Committee has given very careful consideration to the suggestion to make the duty to carry out CRWIAs mandatory for all public authorities. We know there are already issues with public authorities implementing the Public Sector Equality Duty, this is compounded by a cluttered impact assessment landscape. At this time, we do not therefore consider taking this approach would have the desired impact and may, in fact, be counterproductive by making the process bureaucratic and potentially “tick box”.

Reporting duty of listed authorities

Section 15 requires public authorities listed in section 16 to publish a report every three years on actions taken to ensure compliance with UNCRC requirements set out in section 6 of the Bill.

The Committee however recommends the Scottish Government amends section 15(1) to include future actions public authorities have identified for the coming three-year reporting period. The Committee believes this would support the desired culture shift anticipated by the Bill.

Participation and child-friendly reports

The Committee agrees with the Deputy First Minister that public authorities must ensure their staff are trained to undertake CRWIAs, including the participation of children and young people, and to understand how to take a human rights-based approach to their role. Our human rights work has shown that by taking a human rights-based approach, savings in resources can be achieved as needs are met.

In relation to requiring public authorities to produce child-friendly CRWIAs, the Committee asks the Scottish Government to bring forward an amendment at Stage 2 to give effect to this proposal.

Part 4 of the Bill

Court powers to determine compatibility; court powers to deal with incompatible legislation and legislative powers to make remedial legislation

Compatibility with UNCRC requirements statement

Other than Government Bills, there are a few other types of Bills that can be introduced into the Scottish Parliament. These are Member’s Bills, Committee Bills, Private Bills and Hybrid Bills. The Committee notes that Member’s Bills and Committee Bills are types of Public Bills. Public Bills can change the public and general law. This is law that affects people right across Scotland.

In principle, the Committee can see merit in extending a statement of compatibility with UNCRC requirements to Member’s Bills and Committee Bills as these are Public Bills. We note, however, the Committee has not had an opportunity to explore what this would mean in practice with the Parliamentary Authorities. The Committee will therefore seek written evidence to inform Stage 2 proceedings.

Power to strike down future legislation

Where legislation is incompatible with the UNCRC requirements, a court can (depending on the type of legislation in question) make a ‘strike down declarator’ or an ‘incompatibility declarator’ (sections 20-22).

Views were received that the ‘strike down’ power could be extended to future legislation. Although legal and human rights’ witnesses, including the Law Society, JustRight, Faculty of Advocates, SHRC and Children’s Commissioner were happy to accept what the Scottish Government has said on legislative competence, academics offered a more nuanced view.

The Committee recognises that the majority view welcomes the power for courts to ‘strike down’ old incompatible legislation (legislation which pre-dates the Bill), or make a declaration that new legislation is incompatible with the UNCRC (legislation which post-dates the Bill). However, we ask the Scottish Government to respond to the points raised by Dr Boyle, Professor Norrie and Professor McHarg and consider whether the Bill’s approach to future legislation could include ‘strike down’ powers while remaining within the competence of the Parliament.

Reports in response to declarators

Section 23 of the Bill provides that where either type of declarator is made, Scottish Ministers must, within six months, take steps including publishing a report setting out what steps (if any) they intend to take in response to the declarator and laying it before the Scottish Parliament.

Several stakeholders commented unfavourably on the fact that Scottish Ministers were under a duty to report to the Parliament (under section 23) but not a duty to take action to remedy the issue.

It is concerning to the Committee that there is a significant gap in views around the requirement to report and the obligation to act. The Committee would find it helpful to receive more detailed information on how this duty is intended to meet the threshold of an ‘effective remedy’ in advance of Stage 2 proceedings.

The Committee welcomes the Deputy First Minister’s commitment to investigate expanding the duty to include a requirement for the report to be produced in a child-friendly way. The Committee would find it helpful to receive an update on the outcome of the Scottish Government’s considerations on this matter in advance of Stage 2.

Part 7 of the Bill

Commencement

Section 40 of the Bill sets out how the Bill will be commenced, with some provisions coming into force the day after Royal Assent, for example, around regulation making powers. The main commencement provision of the Bill enables Scottish Ministers to set the coming into force date by regulation.

Despite strong support for the Bill, some witnesses and respondents to the call for views have commented that there is no commencement date for the Bill and are frustrated by this.

The Committee acknowledges the need for public authorities to prepare for the Bill coming into force. Public authorities, however, should already have many of the mechanisms in place through other legislation and therefore the Committee is not convinced of the argument that significant additional preparation time is required.

This year has been hard on children and young people who have been significantly impacted by the pandemic. Children need to have their rights protected, respected and fulfilled as a matter of urgency. It is vital to ensure a generation of children and young people do not suffer the long-term impacts of the crisis. The Bill presents an opportunity to give young people greater protection and put them at the centre.

The Committee therefore recommends the Scottish Government amends the commencement provision at Stage 2 to ensure the Bill commences 6 months after Royal Assent.

Costs and demand

The Financial Memorandum to the Bill focuses on the implementation costs of the Bill over three years.

It estimates costs to empower children to claim their rights. This would include children’s rights awareness-raising and participation with children, young children and families and a social marketing campaign. There are also costs estimated to embed children’s rights in public services. This would include funding to help support the public sector to deliver on respecting, protecting and fulfilling children and young people’s rights. The fund will be used in capacity-building and awareness raising activities with practitioners in public services in Scotland.

The total estimated cost is £2,085,000.

Some concerns have been raised with the Committee about resourcing to implement the Bill. However, in the absence of any costed evidence from stakeholders on any additional resource needed, the Committee does not wish to make recommendations at this time. We encourage stakeholders to keep working with the Scottish Government and the Committee will monitor whether resources become a barrier to the Bill’s implementation.

Introduction

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (Incorporation) (Scotland) Bill is a Scottish Government Bill. It was introduced by the Deputy First Minister and Cabinet Secretary for Education and Skills, John Swinney MSP in the Scottish Parliament on 1 September 2020 and referred to the Equalities and Human Rights Committee (“the Committee”) as lead committee at Stage 1. The Committee is required to report to the Scottish Parliament on the general principles of the Bill.

Accompanying documents for the Bill can be found here.

The Scottish Government has produced the following impact assessments for the Bill:

The Scottish Parliament Information Centre has prepared a briefing for the Bill. This contains further information on the Bill’s provisions and information on international rights system, human rights in Scotland, and children’s rights policy and legislation in Scotland.

Equalities and Human Rights Committee consideration of the Bill

In order to inform scrutiny of the Bill, the Committee issued a call for evidence on 7 September 2020, which closed on 16 October 2020. The Committee received 153 written submissions on the Bill, about two thirds of these were from a range of organisations in the public and third sector. Where permission has been granted, these submissions are available on our website along with a summary of written evidence.

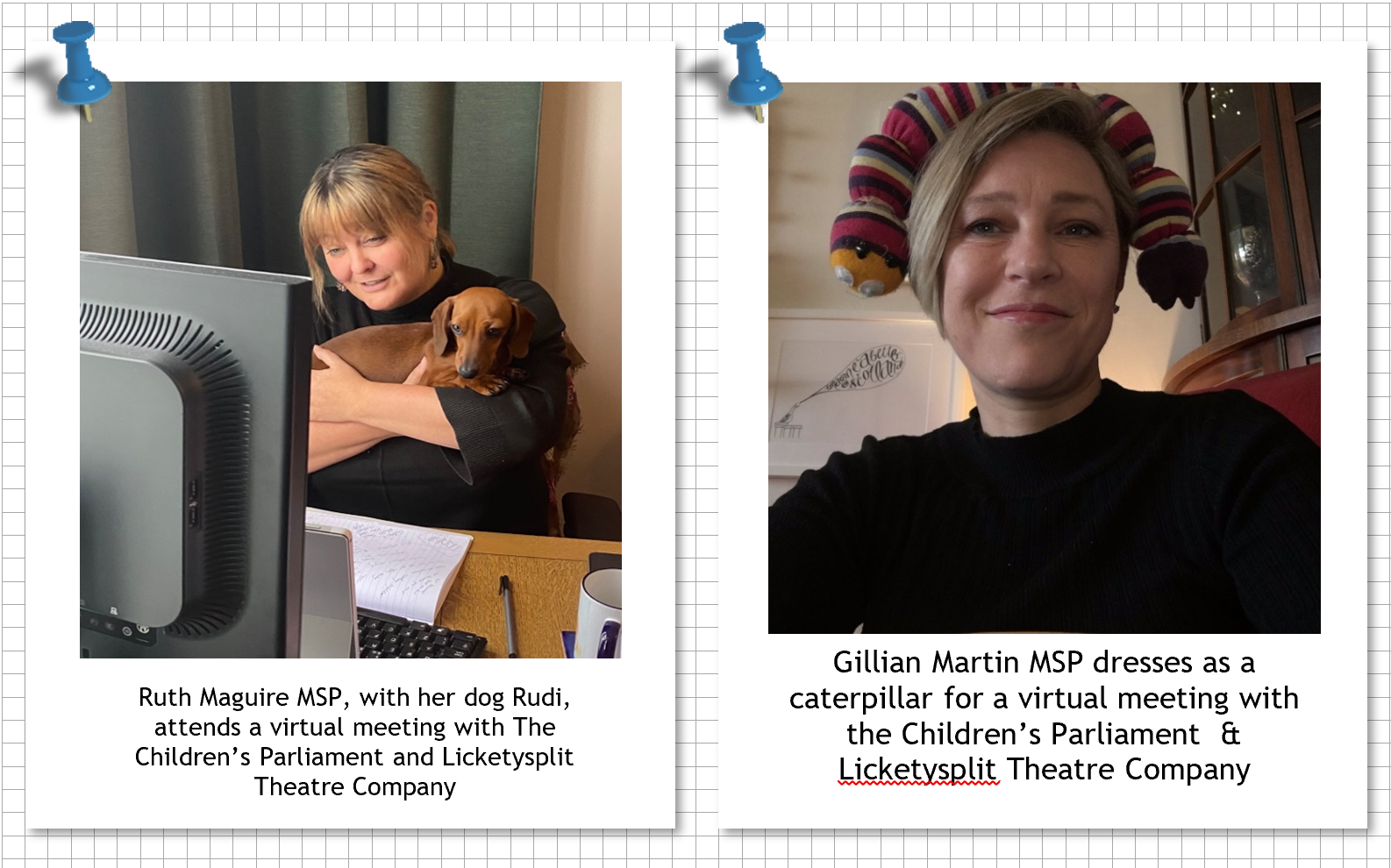

Engagement with children and young people

In addition to this consultation work, the Committee was keen to hear views from as many children and young people as possible. As such, the Committee developed several resources with the assistance of the Children’s Parliament, Children in Scotland and Together Scotland (Scottish Alliance for Children’s Rights) and the Parliament’s Outreach, Public Information Services and the Gaelic team—

Leaflet and Gaelic leaflet on how to submit your views

Easy read booklet on how to submit your views

Facilitators pack and Gaelic Facilitators for adults working with children and young people (including schools)

Additional PowerPoint presentation for schools

How to submit your views in BSL video and video transcript.

These resources helped children and young people respond to a dedicated call for views. The Committee received more than 50 written responses. This is a significant and encouraging rate of response as it is the first time any parliamentary committee has issued such a call for views.

Submissions were received from children and young people as individuals, or as part of a group such as a primary school, high school, modern apprentices, and through activities with other children’s organisations.

The time and thought the children and young people had given to their responses was clearly reflected in the wide and very interesting ways in which they gave their views to the Committee, including reflective writing and drawings, as well as stop motion videos.

This demonstrates how engaged our young people are, and can be, when given the opportunity. and, where permission has been granted, the submissions are available on our website along with a summary of the responses received.

Additionally, the Committee undertook seven engagement calls with a range of children and young people who would not ordinarily provide their views directly to Parliament as detailed below.

28 October 2020: session with 12 to 18 year olds hosted by Together (Scottish Alliance for Children’s Rights)

3 November 2020: session hosted by the Scottish Commission for People with Learning Disabilities (SCLD)

4 November 2020: session hosted by Who Cares? Scotland

7 November 2020: session with children under 12 hosted by Together (Scottish Alliance for Children’s Rights)

11 November 2020: session with unaccompanied asylum-seeking children and young people who have been victims of trafficking, hosted by Aberlour Guardianship

17 November 2020: session hosted by Children and Young People’s Centre for Justice (CYCJ) and Scottish Throughcare and Aftercare Forum (Staf)

18 November 2020: session with young black and people of colour (PoC), hosted by Intercultural Youth Scotland.

A session scheduled for 3 November 2020, hosted by LGBT Youth Scotland for young LGBTI people had to be cancelled at short notice, but LGBT Youth Scotland provided a note of subsequent discussions.

The Committee took oral evidence on the Bill at four meetings during November and December 2020. Links to official reports of those meetings are available at Annexe A.

The Committee appreciates all those individuals and organisations who provided written and oral evidence. We would especially like to thank those children and young people who shared their views through the video calls, artwork, stop motion videos and creative writing. The Committee would also like to express its gratitude to the interpreters, youth organisations, and schools that helped children respond to the children and young people’s call for views and take part in the engagement activities.

Consideration by other committees

The Finance and Constitution Committee issued a call for evidence on the Financial Memorandum for the Bill and received two responses. The Finance and Constitution Committee forwarded these submissions to the Committee. These are considered in more detail later in this report.

The Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee (DPLR) considered the Bill on 8 and 15 December 2020. The Committee notes DPLR’s report and that it is content with the delegated powers provisions contained in the Bill and with the choice of procedure applicable in each case.

Background to the Bill

Purpose of the Bill

The Bill aims to incorporate the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) and the first two optional protocols to the UNCRC into Scots law.

The rights in the UNCRC are guaranteed to every child whatever their ethnicity, gender, religion, language, abilities or any other status. The UNCRC consists of 54 articles. Articles 1-42 contain the substantive rights and obligations which State Parties must uphold and give effect to. For example, the right to education (Article 28), and the right to be protected from violence (Articles 19 and 34). Articles 43-52 concern procedural arrangements for the signature, ratification and amendment of the UNCRC and establish the Committee of the Rights of the Childi. The rights of the child are interdependent and indivisible, meaning they must be seen as a whole, and no right is more important than another.

The Scottish Government ran a consultation on the proposed legislation from 22 May to 28 August 2019. It focused on three themes:

legal mechanisms for incorporating the UNCRC into domestic law

embedding children’s rights in public services

enabling compatibility and remedies.

The consultation analysis published on 19 November 2019, shows there was widespread support for the incorporation of the UNCRC, with only 4 out of 134 respondents expressing general opposition.

According to the Policy Memorandum, the Scottish Government is taking a ‘maximalist’ approach which means the rights and obligations in the UNCRC and optional protocols are being incorporated to the maximum extent possible within the powers of the Scottish Parliament. The intention is that the Bill will result in the highest protection for children’s rights within the boundaries of the devolved settlement as provided for in the Scotland Act 1998ii.

As referred to in the Policy Memorandum there have been a number of Acts that give effect to rights and obligations in the UNCRC in Scotland, for example the Children (Scotland) Act 1995 on child welfare and protection, the Commissioner for Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2003, the Protection of Vulnerable Groups (Scotland) Act 2007 that relates to people working with children, and the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014, amongst othersii.

In evidence to the Committee, John Swinney, the Deputy First Minister and Cabinet Secretary for Education and Skills (the Deputy First Minister) said—

The bill will deliver a revolution in children’s rights, requiring that children’s rights must be respected, protected and fulfilled. It will drive a culture of everyday accountability for children’s rights and will require public authorities to act consistently to uphold those rightsiv.

International and the UK context

Scotland would be the first country in the UK to incorporate the UNCRC.

In 2004, the Welsh Government formally adopted the UNCRC as the basis of policy making relating to children and young people. Subsequently, it legislated to place a duty on Ministers to have ‘due regard’ to the UNCRC when developing or reviewing legislation and policy under the Rights of Children and Young Persons (Wales) Measure 2011. This means Ministers must give appropriate weight to the requirements of the UNCRC, balancing them against all other factors relevant to the decision in question. It also makes provision for a Children’s Rights Scheme at Section 2.

The Scottish Human Rights Commission (SHRC) stated that “Incorporating international human rights treaties into domestic law is a critical component of securing their realisation”. It also reflected on international practice on incorporation of the UNCRC: “In doing so it will follow in the footsteps of many other jurisdictions around the world including Norway, Belgium, Spain and most recently Sweden”i.

Elin Saga Kjørholt (UNICEF (Norway)), told the Committee how it is important to incorporate all the rights together so that you don’t have a fragmented approach. UNCRC incorporation in Norway had been very successful in helping to raise awareness of children as rights holders, including the legal sector. Public authorities became more committed to upholding children’s rights than before; it has “changed the culture on how we view children and children’s rights”ii.

UNICEF commissioned a report that looked at the implementation of the UNCRC in countries beyond the UK, compiling evidence on the most effective, practical and impactful ways of embedding children’s rights into domestic law and policy development processes. Twelve countries were examinediii to demonstrate the various ways different countries have chosen to legislate for children’s rights and to implement the different articles of the Convention.

From an international perspective, Dragan Nastic (UNICEF UK) said the Bill is unique because no other country has gone that far in their process of incorporation and that UNICEF has promoted and publicised the Bill in other countries and he hoped that it will lead the way in the UK and around the worldii.

Support for the Bill

Nearly all the respondents to the Committee’s call for views support the objective of the Bill, to incorporate the UNCRC into Scots law.

Bruce Adamson, (The Children and Young People’s Commissioner Scotland) (the Children’s Commissioner) explained that “fully and directly incorporating the UNCRC into domestic law is the most important thing that we can do to ensure that children’s rights are respected, protected and upheld”.i He added—

The bill is really strong. It builds on an understood framework that we already know through the Human Rights Act 1998 and, importantly, it strengthens it. It has not only the legal compatibility obligation, but the scheme and the additional measures of implementation that are very useful in making rights real.i

Juliet Harris (Together (Scottish Alliance for Children’s Rights) (Together Scotland)) said that the very process of incorporation brings about a culture change in which children and young people are better recognised as rights holders. She reflected on the passage of the Children and Young People Act 2014, seven years ago, and said “we’re living that culture change.”iii

Dragan Nastic (UNICEF UK) congratulated Scotland on an excellent Bill that would lead to better and effective realisation of children’s rights. He noted that as well as directly incorporating the UNCRC, the Bill includes a package of active and reactive implementation measures.

A member of the Children’s Parliament said—

We need our rights so that bad things don’t happen to us.iv

A former Member of the Scottish Youth Parliament for LGBT Youth Scotland told them—

Incorporation will mean protections that need to be guaranteed and safety for children and young people. It is easier to look at a written document that says that these are the things I should have, rather than kind of guessing what you think you should have. This is empowering for me as a young person.v

Our engagement activities and responses to the Committee’s dedicated young persons’ call for views showed children and young people are excited about the incorporation of the UNCRC into Scots law. Children and young people recognised how important it is for their voices to be heard, and for their rights to be respected. They emphasised too, the importance of awareness of the UNCRC, not just among children and young people but also among adults.

For example, one young person who talked with LGBT Youth Scotland said—

I think as with everything it would take a while for the culture to seep in - legislation is the first step. Once that’s legalised – then it goes into popular culture - the more the effect of a thing being seen or experiences - LEAD TO CULTURE CHANGE.vi

An engagement participant from Children in Scotland told the Committee—

COVID has meant there have been big discrepancies - depending on [children’s] background, age and where they live and the school they go to. If the UNCRC had already been incorporated into law, it would have helped to address these discrepancies.vii

Police Scotland, COSLA, Glasgow City Health and Social Care Partnership (GCHSCP) all supported the general principals of the Bill.

Mike Burns (GCHSCP) said “the bill builds on the bedrock of the Children (Scotland) Act 1995, which encapsulates quite a number of the UNCRC’s articles, and the getting it right for every child policy direction, which we have been implementing in Scotland since 2006”.viii

Comprehensive, co-produced guidance was highlighted by public authorities as key to implementation of the Bill.

Eddie Follan (COSLA) said we need guidance that is “developed in partnership with us, that builds on best practice and that looks at what is in place and works at the moment. We also need to make sure that that guidance is fully consulted on and fully informed by the views of children and young people”.ix

Similarly, Mike Burns (GCHSCP) considered the issue of guidance significant and said there needs to be to “alignment, coordination and cohesion”.viii

Rosemary Agnew (Scottish Public Services Ombudsman (SPSO)) welcomed the Bill, but she warned there needed to be a cohesive approach to the transition from childhood to adulthood, as the Bill refers to a child up to the age of 18, but often those who need the support of public services need it beyond the age of 18.xi

The Committee asks the Scottish Government to set out how it intends to work with stakeholders, including children and young people, to develop the guidance to accompany implementation of the Bill. Also, the Committee asks the Scottish Government for its views on how it will address in guidance the transition from childhood into adulthood.

The evidence received by the Committee shows widespread support across a range of stakeholders for the incorporation of UNCRC into Scots law and the strengthening of children’s rights in Scotland.

Evidence did however highlight some specific areas of the Bill where the Scottish Government could improve upon or strengthen. This report therefore focuses on these areas and the related sections of the Bill (in chronological order). Consequently, not all provisions are covered by the Report.

Part 1 of the Bill

Incorporation of the UNCRC requirements

Part 1, sections 1-5, incorporates the UNCRC requirements into Scots law in so far as possible within the Scottish Parliament's powers. The incorporated provisions are defined in the schedule of the Bill as the 'UNCRC requirements'.

Method of incorporation

Direct incorporation, i.e. directly transferring the Convention into Scots law was the favoured approach.

Josh Kennedy (The Scottish Youth Parliament (the SYP)) told the Committee how the SYP had campaigned for several years on UNCRC incorporation. In their 2016-21 ‘Lead the Way’ manifesto, 76% of young people supported direct incorporation of the UNCRC. He said—

UNCRC rights are universal and equal. Scotland can set a leading example for the world by not cherry picking which UNCRC rights should apply and keeping intact the principles of universality, indivisibility and interdependence on human rights, which is extremely important.i

Together Scotland considered it an extremely strong Bill that has been drafted in a very inclusive way—

The drafters have listened to children and young people who said that they wanted full and direct incorporation because they wanted to know that the rights in the bill were the same rights as those in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, which other children across the world also enjoy. From education, health and social work through to transport, policing and the environment, full and direct incorporation provides clarity that children and young people have the rights in the UNCRC. It means that those rights are not just something that we need to think about but are embedded in everything that we do.ii

On the other hand, Professor Kenneth Norrie (University of Strathclyde) would have preferred the Bill to convert the substantive rights of the UNCRC into specific Scottish rights as he believed this would make the law more accessible. He referred to recent legislation to raise the age of criminal responsibility from 8 to 12 years and argued it would have been easier to legislate that “children below a certain age have a right to have their behaviour dealt with in a welfare-based system rather than by the general courts”.iii

Professor Norrie also expressed concern direct incorporation might create a lack of motivation to advance children’s rights: “We must remember that the UN convention ticks minimum standards”.iii

UNICEF however, noted—

Scotland is the first country in the UK to fully and directly incorporate the UNCRC into its domestic law. This model of incorporation is very rare in common law countries where the majority tend to amend existing legislation rather than incorporate the UNCRC into the national legal framework. Thus, this Bill acquires an additional significance and provides a strong model of incorporation with the potential to be world-leading if supported by effective implementation.v

The Committee acknowledges the concerns raised by Professor Norrie. In considering the method of incorporation taken by the Bill, the Committee has considered all the information at its disposal, including the Scottish Government’s consultation. On balance the Committee believes the Bill’s approach is appropriate. However, as the Committee responsible for scrutinising the age of criminal responsibility legislation at Stage 1, we have some sympathy with the point being made about the potential risk of incorporation being seen as having achieved the minimum UNCRC standards.

In our human rights report, Getting Rights Right, the Committee emphasises the need to also identify opportunities to advance rights. The Committee therefore recommends the Scottish Government should, in i) its guidance to public authorities on the Bill, ii) any supporting documentation for conducting Child Rights and Wellbeing Impact Assessments and, iii) when preparing and reviewing its Children’s Rights Scheme, make it clear that opportunities to advance children’s rights should form part of the process.

Section 4: Interpretation of the UNCRC requirements

Section 4 sets out that a court or tribunal may take into account the texts of the UNCRC and the two optional protocols that have not been incorporated (e.g. Preambles), when they are determining a case. The Explanatory Notes to the Bill state that—

Since some treaty text, or preamble text, not included in the schedule may have a bearing on the interpretation of text that is included in the schedule, section 4 confirms that a court or tribunal that is determining a question about the UNCRC requirements may take into account any text of the treaty that is not currently set out in the schedule, as well as the treaty's preamble, so far as it is relevant to the interpretation of the UNCRC requirements in a case.i

Unlike the Human Rights Act 1998, where courts can rely on case law from the European Court of Human Rights, there is no body of case law on the UNCRC from an international court.

The Committee heard strong views from many witnesses including academics, legal professionals, National Human Rights Institutions (the Children’s Commissioner and the Scottish Human Rights Commission (SHRC)) and children and young people’s and equality organisations, that section 4 of the Bill should be amended to include additional sources.

Dr Katie Boyle (Stirling University) said—

We need to have reference to other bodies in order to fully understand how the UNCRC has been developed and interpreted over time, particularly in relation to children’s economic and social rights. I recommend that the interpretation clause be expanded to include treaty body decisions, optional protocols, general comments, recommendations and comparative law.ii

In relation to any unintended consequences, Dr Boyle said—

…there might be a fear that that would make all those decisions binding, but that is not what an interpretation clause does. It asks the interpreter to have regard to the other instruments in order to help them to understand the meaning of the rights.ii

Janys Scott (Faculty of Advocates) and other legal practitioners welcomed additional interpretative sources “as long as that element is not determinative”.ii

Further reasons for the inclusion of additional sources of interpretation were provided by Together Scotland and the Scottish Youth Parliament.

Juliet Harris (Together Scotland) reminded the Committee that the UNCRC is 30 years old and should be viewed as a living document, and as such section 4 needs to be amended—

to provide that the courts may also consider General Comments, Concluding Observations, opinions under the third optional protocol and reports resulting from Days of General Discussion as well as comparative law and future advances.v

She gave examples of general comments on the right to inclusive education, and on women and girls with disabilities.vi

While, Josh Kennedy (Scottish Youth Parliament) echoed the points raised by Juliet Harris (Together) and talked about inclusion of other sources providing an important level of accountability for decision makers.vii

Susie Fitton (Inclusion Scotland) argued that direct reference should be made to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) to provide for the courts “to take account of those critical sources and take the widest approach possible to ensuring that disabled children’s rights are upheld”.viii

On a technical point, Professor Elaine Sutherland (Stirling University) suggested wording at section 4 should be amended from “the court may take into account the convention and the two ratified optional protocols”, to ‘must’ or ‘shall’, as it “would seem odd, when looking at convention rights, not to look at the convention and, where relevant, the optional protocols”.ix

John Swinney, Deputy First Minister and Cabinet Secretary for Education and Skills, advised the issue is under active consideration–

We are looking at a range of issues that have emerged around the drafting of the bill and the reactions from different interested parties, which get into the issue of what degree of detail it would be advisable, or not advisable, to have in the bill.x

The Deputy First Minister committed to look carefully at what the Committee says on this matter and confirmed he is keen to proceed with the objective of “maximum agreement” on the Bill’s provisions. x

The Committee understands that sometimes too much information could restrict practical implementation and make the Bill less effective. In this case however, the Committee is persuaded by the arguments that other sources of interpretation should be included on the face of the Bill, as these sources would not be determinative, and the list of sources would be non-exhaustive. This approach is attractive to the Committee because of its transparency and because it demonstrates to public authorities tasked with implementing the Bill the variety of sources that may be used by courts and tribunals. This, the Committee considers, would lead to a better understanding of the culture change required, where UNCRC rights are understood to be ever developing, inter-related and indivisible.

The Committee recommends the Scottish Government amends the Bill so that courts and tribunals ‘must’, rather than ‘may’, take into account the whole of the text of the UNCRC and the two optional protocols, when they are determining a case.

In addition, the Committee recommends the Scottish Government brings forward amendments at Stage 2, so that courts and tribunals ‘may’ look at a range of other UN materials, as listed: treaty body decisions; other relevant optional protocols (including opinions under the third protocol); general comments, concluding observations, and recommendations (UNCRC and other relevant international treaties); comparative law; and reports resulting from Days of General Discussion.

Part 2 of the Bill

Need for a ‘due regard’ duty

Section 6 of the Bill would place a duty on public authorities, such as local authorities and health boards, not to act in a way which is incompatible with the UNCRC requirements (as set out in the schedule of the Bill).

In response to the Scottish Government committing to incorporate the UNCRC in 2018, the Independent Advisory Group (convened by Together and the Children’s Commissioner) drafted their own Children’s Rights (Scotland) Bill. This was presented to the Deputy First Minister and Minister for Children and Young People on 20 November 2018 – Universal Children’s Day. It had a dual duties approach – to provide both a duty to not act incompatibly and a duty to have due regard.

The Scottish Government consulted on this approach. The Policy Memorandum states that many respondents were attracted to this idea on the basis that it would provide both a ‘proactive’ and ‘reactive’ protection for children’s rights.i

The Scottish Government considers that a proactive approach is inherent in acting compatibly with human rights and was concerned that such an approach risked causing unnecessary duplication and confusion. As is the case under the HRA, the compatibility duty in the Bill is a continuing obligation.i

There was debate about whether introducing a ‘due regard’ duty on public authorities, in addition to the compliance duty, would strengthen the Bill.

Kavita Chetty (Scottish Human Rights Commission) (SHRC) argued that it was important to add a duty to have ‘due regard’. She said this approach "would provide clarity on the obligation of conduct or process and would ensure that there was rights-based decision making as part of the “due regard” duty”.iii

The Human Rights Consortium Scotland shared this view and likened the approach to “the public sector equality duty that requires public bodies to have due regard to promote equality of opportunity between different disadvantaged groups”.iv

Other human rights experts were less enthusiastic.

Bruce Adamson, (the Children’s Commissioner) considered that although the duty to have ‘due regard’ might be a helpful addition, the key duty was not to act incompatibly and that would drive change.v

Although Wales had opted for a ‘due regard’ duty, Dragan Nastic (UNICEF) explained this was because incorporating the UNCRC is outwith its powers.vi

Young people’s organisations, Together and the Scottish Youth Parliament thought the policy intent behind the inclusion of the ‘due regard’ duty in the draft Bill, i.e. promoting a proactive approach to children’s rights, remained important, but they along with Who Cares? Scotland, suggested an alternative approach would be to strengthen Part 3 of the Bill as a way of delivering that original policy intention.

The Deputy First Minister explained that the Scottish Government had not legislated for dual duties because the Bill establishes the highest standard—

Essentially, we are saying to public authorities that they must satisfy themselves that their approaches are fundamentally compatible with the expectations of the UNCRC.vii

He added—

A duty to have “due regard to” the UNCRC would perhaps be more arguable territory, whereas a duty to “act compatibly with” it will place on public authorities an obligation that will—to be blunt—be more difficult for them to wriggle out of. My judgment is that we should establish a clear approach in trying to secure the highest standard of action.vii

The Committee notes the good arguments for inclusion of a ‘due regard’ duty. Nevertheless, it is not convinced this would be the best approach. We believe the duty to not act incompatibly is clear and robust. Adding a further layer of complexity, to what is already a novel Bill, runs the risk of diluting the Bill’s impact through lack of clarity. The Committee does however acknowledge the need for further stimulus around public authorities taking a proactive approach and this is addressed throughout this report.

The definition of a public authority

Under section 6 of the Bill, the definition of a ‘public authority’ is not exhaustively defined, although its meaning has been considered before the UK courts in relation to the equivalent definition in the Human Rights Act 1998.

Inclusion of the Scottish Parliament as a public authority

Section 6 says a public authority would include Scottish Ministers, but not the Scottish Parliament.

Dr Boyle (Stirling University)i, Professor Tisdall (The University of Edinburgh)ii and Professor Sutherland (Stirling University)iii suggested that the Parliament should be included in the definition. Andy Sirel, (JustRight Scotland), wondered if its inclusion would raise any issues of legislative competence under the Bill and suggested it may be worth exploring further to understand the implications.iv Dr Boyle considered this issue and stated—

Indeed, the Policy Memorandum suggests that a provision requiring future Acts of the Scottish Parliament to be compatible with UNCRC would effectively change the power of the Parliament and is, therefore, beyond its current powers (para.107). This in itself is a contested position. Ideally the Scottish Parliament would also be under a duty to comply.i

The Deputy First Minister said the Parliament needs to reflect carefully as there are some complex issues to be resolved—

The Scottish Parliament is a product of the Scotland Act 1998—it does not have the ability to amend that act and we have to act compatibly with it. It may well be that, if the Parliament was to decide to pursue that particular approach, it would have to be careful to act within its legislative competence in respect of which obligations it could take on. The committee will be familiar with the fact that we have had to craft the bill carefully to ensure that we do not move into areas where we would transgress on legislative competence on any issues around the application of the bill.vi

He added that he had written to the Parliament’s Presiding Officer to encourage dialogue between Scottish Parliament and Government officials on the question.

While there has been support for the inclusion of the Scottish Parliament as a public authority, detailed discussion on the matter has been limited. In principle, the Committee would like to see the Scottish Parliament included within the definition of a public authority and therefore subject to the duty not to act in a way which is incompatible with the UNCRC requirements. Currently however, there appears to be insufficient evidence on the matter to take a definitive view. We are also conscious it would be unhelpful for the Bill to be judicially reviewed, potentially delaying commencement.

The Committee asks the Scottish Government for an update on the officials’ discussions to inform Stage 2.

A ‘hybrid’ public authority

Section 6 also recognises the possibility of a 'hybrid' authority, in other words where a ‘public authority’ might, depending on the circumstances, include a private sector or voluntary sector body carrying out public functions.

Susie Fitton (Inclusion Scotland) explained that the definition of a public authority is very important for disabled children, as they can be “impacted by the decisions and actions of private housing providers, residential care providers, private childcare providers, private foster carers and public schools”. She listed the type of rights breaches that might arise, such as negligent practice in relation to seclusion and restraint in private childcare provision, provision of adaptations in private rented housing, and poor physical access in schools.i

Who Cares? Scotland also raised concerns about private sector bodies in the context of its work—

Particularly in the care and protection system, there are a great variety of private providers who carry out essentials services for Care Experienced children and young people – from the operation of children’s homes, to the provision of mental health services. Many of these private providers have a great deal of power to impact on Care Experienced children’s rights being upheld and protected, therefore they must come within the scope of the duties on public authorities.ii

Several stakeholders including academics and legal practitioners argued that the current human rights case law on which private sector bodies are included in the definition of a public authority is unsatisfactory.

Also, they considered relying on this case law runs the risk of excluding certain private sector bodies that carry out important public sector functions. Dr Boyle had a major concern that “when children interact with any form of public service that has been outsourced to a private body, they may ultimately not have the human rights protection that they deserve”,iii citing the Ali v Serco Ltd case in Scotland, where she said, “the motivation of the private provider currently supersedes the protection of the rights holder”.iv

Legal practitioners also sought clarity on this point. Janys Scott (Faculty of Advocates), considered it important to clarify if a private organisation is exercising a public function.v Andy Sirel (JustRight Scotland) spoke about the need for local authorities and private parties to be certain about their obligations when entering into a procurement exercise.vi

In tackling this issue, Professor McHarg suggested the Australian example of the Victorian Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilitiesmight offer a better approach to defining a public authority in this context.iv

Bruce Adamson, the Children’s Commissioner, also believed the definition should be strengthened.viii

Rosemary Agnew (Scottish Public Services Ombudsman) said it was important to focus on the function, but equally on the obligation which needs to follow the child and that the crucial question to ask is “whether the child’s rights and the protection of them are as strong now as they would be if a public service had been delivering the service directly”.ix

While Kavita Chetty (SHRC) advised—

[…] it is a well-established principle of international law, including explicitly in the UNCRC general comment 16, that the state cannot divest itself of its human rights responsibilities by outsourcing or delegating them. If Scotland is to fulfil its international obligations in the way that the bill intends, it must ensure that those accountability gaps do not persist through the contracting-out of services that are not caught by the definition in the bill.x

Public authority witnesses were mostly content with the definition of a ‘public authority’ as drafted, although a few were open-minded about extending the definition.

Alistair Hogg (Scottish Children Reporters Administration (SCRA)) was supportive of expanding the definition saying, “if you were carrying out a public function, you should be covered by the expectation to observe the UNCRC”.xi

Eddie Follan (COSLA) considered any issues could be addressed in guidance on the legal duties of public bodies, however, he said COSLA would be open to a discussion on how it could be extended.xii

The Deputy First Minister was very clear that a public authority “cannot divest itself of, or escape, its obligations under the UNCRC and pass them on to some other body”. He considered it “important that any public authority that asks any other body to act on its behalf must satisfy itself that that body is acting in a fashion that is compliant with the UNCRC” and was anxious to ensure the Bill’s provisions “are sufficiently restrictive to ensure that no arrangements enable that to happen”.xiii

The Committee has heard significant evidence that the definition of a public authority, as set out in the Human Rights Act 1998, on which this Bill’s provisions are based, is being interpreted by the courts in a way that would be contrary to the spirit and intention of this Bill. We recognise this issue could either be addressed by amending the definition in the Bill or by providing absolute clarity on this point in the guidance issued to public authorities. The latter option, the Committee notes, does not stop the courts from interpreting the definition more narrowly over time.

The Committee recommends the Scottish Government undertakes a further investigation, with the involvement of the main stakeholders, as to how the definition could be tightened to avoid similar issues arising as those experienced with the Human Rights Act 1998 and provide an update to the Committee in advance of Stage 2 proceedings.

Court processes and remedies for breach of the duty on public authorities

A key component of Part 2 of the Bill is that if there is an alleged breach of the duty on public authorities (contained in section 6) an individual or organisation can raise court proceedings seeking “judicial remedies” in respect of that alleged breach of the UNCRC requirements (section 7). Separately, section 7 of the Bill envisages that UNCRC issues could arise as part of ongoing court proceedings on another matter.

The approach in Part 2 of the Bill means that existing courts and tribunals (as opposed to a new court or tribunal) would be used, and, for the most part, no new judicial remedies are created by the Bill.

Several submissions raised issues around the ability of children to obtain access to justice within existing systems. UNICEF UK, SHRC and the Children’s Commissioner argued that improving access to justice for children was required in the context of the Bill. Kavita Chetty (SHRC) referred to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, General Comment 5, that for children to access justice they need child-friendly information, advice, advocacy, support for advocacy, access to complaints procedures and access to assistance.i

Child-friendly court system

While Professors Norrie and McHarg emphasised the positive features of the Bill that improved the accessibility of the court system to children, such as the role of the Children’s Commissioner in raising court proceedings, others considered accessibility of the court system to children and young people in practice presented difficulties.

Oonagh Brown (SCLD), told the Committee courts are not accessible in relation to the needs of many children and young people or adults with disabilities. For example, “there is a lack of accessible information on taking legal cases, there are attitudinal barriers to do with their ability to take such cases and there is a lack of specialist awareness of learning disability among legal professionals and within the courts”.i

Andy Sirel (JustRight Scotland) talked about the practicalities of a child pursuing a case, for example, against a corporate parent. He said they would need to be able to instruct a lawyer, qualify for and obtain legal aid and engage an advocate. As such he considered—“The real burden therefore lies with the child and not the public authority.”ii

Professor Sutherland said the court system was “designed by adults for adults. In fact, it is intimidating to a lot of adults, so how much more so must it be to a child?”.iii She said, nonetheless, being able to seek remedy in courts and tribunals is essential in influencing how public authorities exercise their functions but, along with Dr Boyle, The Law Society, and Professor Tisdall, she agreed it should be a last resort, as did several respondents to the call for views.iv

Some witnesses highlighted examples of good practice. Professor Tisdall referred to the Additional Support Needs Tribunal for Scotland.v Also highlighted, was the children’s hearings system, which the Children’s Commissioner said shows very good practice.vi In addition, YouthLink Scotland referred to the Barnahus model, a specific legal approach, well-developed in Scandinavian countries, which aims to respond to the needs of children when gathering their evidence for the purpose of court proceedings.

Advocacy services

It was stressed by a range of witnesses, including Professors Sutherland and Tisdall, that advocacy services are necessary to help make courts and tribunals more accessible to children and young people.

Professor Sutherland said parents may advocate on behalf of their child, but there are children who may be in foster or residential care who need to know that there is someone independent of the organisation who can help if their rights are not being respected.i She said—

We must consider developing a child advocacy service.ii

Members of the Committee heard how important advocacy was from the young unaccompanied asylum seekers they spoke to with Aberlour Guardianship about Article 25 of the UNCRC, which says someone who works for the government should check up on the care, protection and health of children and young people when they’re away from their families—

Yes, I’m really happy I’ve got a home like other children and I’m okay. Really happy even though my family is not here. I have a Guardian and a social worker who checks up on me and I’m really thankful for that.iii

On the need for independent advocacy, Susie Fitton (Inclusion Scotland) urged the Committee to consider how provisions on that can be strengthened in the Bill, for example, through an amendment that adds a requirement on the Scottish Ministers to set out a process for child-friendly and accessible complaints in the children’s rights scheme.iv

The Royal College of Psychiatrists in Scotland wrote that “While the ability to seek action in this way can act as a powerful incentive for change, (…) this needs to be backed up by support and guidance for families who feel forced to take this measure. This includes access to free independent advisors”.v

Carly Elliot, (Who Cares? Scotland) talked about the benefits of advocacy services—

The role of advocacy services is incredibly important in that regard. If the bill was able to focus more robustly on the provision of services such as advocacy, children and young people could be supported to challenge rights abuses without having to step into the legal sphere. I do not think that any of us wants children to have to go to court, either directly or with other organisations through the sufficient interest test. We want to keep them out of that space.vi

Legal aid system

Problems with the legal aid system as it applied to children, such as the eligibility criteria, were highlighted by Professor Tisdall, JustRight Scotland, and the Faculty of Advocates.

Witnesses noted the legal aid system, which was currently under review by the Scottish Government. Professor Tisdall considered children’s rights to legal aid should be addressed through the Bill, as did Andy Sirel (JustRight Scotland) who suggested the Committee should consider “whether there should be something in the Bill that relates to free access to legal advice or other legal instruments, such as there is in the South African directive”.i YouthLink Scotland referred to research suggesting there was a “social return” for the money invested.

The Committee asks the Scottish Government how it intends to take account of the implications of the Bill for legal aid and for this information to be made available to the Committee in advance of Stage 2.

When asked about the accessibility of the existing court system, the Deputy First Minister emphasised a range of arrangements are already in place. He highlighted the main such mechanism, by which the voice of children and young people can be heard, is through the Children and Young People’s Commissioner Scotland.ii

The Deputy First Minister was resolute in his thinking that creating another element of court or tribunal infrastructure is not a solution. His preference would be to ensure that the arrangements of the court and tribunal system in Scotland today are accessible and compatible with addressing the interests of children and young people.ii

The Committee asks the Lord President in advance of Stage 2 to reflect on this evidence and to provide further details on progress being made on a child-friendly court system in preparation for the Bill.

Effective Remedies

Depending on the court or tribunal, and on the court procedure involved, available remedies might include, for example—

a court order to stop an act which is threatened or is ongoing

a court order requiring a person or organisation to do something they are legally required to do

damages, an order to pay a sum of money

a court order overturning the original decision and giving the issue back to the decision maker to look at again.

Dr Boyle, supported by SHRC and Together Scotland, said that the requirement for an effective remedy should appear on the face of the Bill. Dr Boyle advised that while the Policy Memorandum states that the Bill includes ‘effective remedies’ for violations of the UNCRC—

The Bill does not provide a definition of what constitutes an ‘effective remedy’ nor does it compel the court to ensure the remedy deployed meets the threshold of an ‘effective remedy’.i

She recommended that the Bill should include the right to an effective remedy, or that the courts should have to strike the balance of ensuring that remedies are “just, effective and appropriate”.ii

Dr Boyle further explained there is an opportunity to refocus on what an effective remedy means by asking what the threshold is for it to be effective. She advised there is case law on this—

The courts were used to doing that under European Union law, but we have now lost the right to an effective remedy under EU law as a result of Brexit. We have the right to an effective remedy under the ECHR but, again, that was not incorporated as part of the Human Rights Act 1998, so there is a gap in provision there. The UNCRC bill presents an opportunity to address that gap for children.iii

Together Scotland said remedies need to be considered in line with principles 19-23 of the UN Basic Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Remedy, such as—

Restitution: as required to restore the situation before the breach occurred - for example restoration of liberty, return to place of residence, restoration of family life or other measures as appropriate.

Rehabilitation: including medical and psychological care, as well as legal and social services.

Satisfaction: may include public disclosure of an accurate account of the violation, public apology, investigation or other measures as appropriate.

Guarantee of non-repetition: including measures to protect human rights defenders, providing human rights education as a priority to all sectors of society, promoting mechanisms for preventing and resolving conflicts, reviewing and reforming laws which have contributed to the violation or other measures as appropriate.iv

Furthermore, Rosemary Agnew (SPSO) considered it important that remedies should drive organisational change and, vitally, should consider what children might want as a remedy.

Remedies for systemic issues

An example of a serious rights violation was drawn to the Committee’s attention. Who Cares? Scotland said—

Child abuse has long featured in the history of Care Experienced people’s lives in Scotland…We encourage the committee to consider this response, with a particular focus on our assessment of what effective redress can include in both financial and non-financial terms. Importantly, for many Care Experienced people, non-financial redress must include varied options including apologies from the state and the offer of free therapeutic support. This combination of non-financial redress is important in leading out reparative justice which seeks to reverse the feeling of self-blame that many individuals experience when the subject of systemic rights failures.i

Dr Boyle said that remedies like individual awards of damages were often not the best way of fixing systemic issues affecting multiple individuals.ii

Kavita Chetty (SHRC) expanded on this saying consideration should be given to empowering the courts to grant so-called ‘structural interdicts’. These would involve a direction to public authorities to implement a certain change, with their success in this regard then being potentially monitored by the courts.iii Dr Boyle advised that the national task force on human rights leadership is looking at ‘structural interdicts’.ii

In response to whether the Bill does enough to ensure that the judicial remedies that courts and tribunals can provide would be effective in practice, the Deputy First Minister said—

The mechanisms are there, but the earlier part of that process is more important. I would consider it a bit of a failure, frankly, if the remedy route had to be pursued.v

By way of further explanation, the Deputy First Minister said—

I see it as an opportunity for us to make significant progress on changing the way in which public authorities act and operate. If a remedy is sought through a court or tribunal, we will have to face that, but I would rather have the cultural change than rely on a series of remedies to change the way in which we go about addressing these issues.v

It is not clear to the Committee that Part 2 of the Bill does enough to ensure that the judicial remedies that can be provided by courts and tribunals will be effective in practice. For example, will they focus on what a child or young person might want, or ensure changes in the public authority concerned for the benefit of other rights holders in future.

The Committee asks the Scottish Government to amend the Bill to ensure the rights holder has a right, under section 8 of the Bill, to an effective remedy. For example, section 8 could be amended to require courts to issue a remedy which is ‘just, effective and appropriate’. Furthermore, the Committee asks the Scottish Government to amend the Bill to define what constitutes an effective remedy.

As part of its consideration of what constitutes an effective remedy, the Committee asks the Scottish Government for its views on the use of structural interdicts to address systemic rights breaches in advance of Stage 2.

Also, the Committee asks the Scottish Government to amend the Bill to require courts and tribunals to ask for the child’s views on what would constitute an effective remedy in their case. The Committee is aware of precedent in other legislation e.g. section 11 of the Children (Scotland) Act 1995 (as amended by the Children (Scotland) Act 2020 (when it comes into force)).

Who can bring court proceedings?

Section 7 of the Bill says that a person, defined as an individual or organisation, can bring court proceedings in respect of an alleged breach of the (section 6) duty on public authorities.

Section 10 of the Bill would specifically allow the Children’s Commissioner to raise court proceedings.

Witnesses were generally positive about the proposed approach. Bruce Adamson, the Children’s Commissioner, advised he had made a number of interventions at the Court of Session and recently at the Supreme Court, relying on the rules of court. However, he considered it useful to have the power set out specifically in the Bill, as it is essential to be able to intervene in cases before the court, and to initiate cases where there is a strategic need to do so.i

The SHRC argued that it should be in the same position as the Children’s Commissioner under section 10. It commented—

This would allow for different issues to be brought before the courts depending on the strategic priorities and differing interests of the two institutions.ii

Judicial review is an existing type of court procedure which, in practice, would be one of the key court procedures which is likely to be used. The Government has said that, for court actions for judicial review, organisations can represent children in court actions if they satisfy the test of ‘standing’, which requires them to have ‘sufficient interest’ in the subject matter of the case.iii However, this is not explicitly stated in the Bill.

On section 7, witnesses including Professor McHarg, JustRight Scotland and the Faculty of Advocates said they were pleased that the test of ‘sufficient interest’ envisaged for judicial review actions, as opposed to the (more restrictive) victim test appearing in the Human Rights Act. They highlighted the potential role this test gave organisations in raising court proceedings on behalf of children.

Several witnesses including JustRight Scotland, Together, the Scottish Youth Parliament and Inclusion Scotland said that, while they supported the Scottish Government’s policy intention in relation to this aspect, they thought the drafting could be improved to provide greater clarity on the face of the Bill.

The SYP wrote, “MSYPs have told us they would like to see a wide variety of individuals and bodies granted the ability to bring forward proceedings”. They supported this approach as they believed it would help ensure that vulnerable children and young people can be represented in cases. SYP echoed Together’s view that the legislation could be further enhanced by including some clarity on the “sufficient interest” approach on the face of the Bill.

Andy Sirel (JustRight Scotland) explained his concern is that at a UK policy level, there is some negativity towards the role of third sector organisations in judicial review actions. An explicit requirement in section 7 might “future proof” the role of organisations in raising court proceedings under the UNCRC legislation. Although, Andy Sirel recognised that as ‘sufficient interest’ was a test interpreted by the courts, there was still a risk, regardless of what was said in the legislation, courts would start to interpret the test to take a more restrictive approach to the role for representative organisations.iv

Several witnesses including Who Cares? Scotland, Inclusion Scotland and the SCLD, highlighted that public interest organisations would need training on how to bring legal cases on behalf of children. Oonagh Brown (SCLD) for example, said it thought its sector had been left behind in this regard and needed ‘upskilling’.v

In response to calls to amend section 7 to provide greater clarity for organisations that might wish to challenge a public authority, the Deputy First Minister said, “what we have in the Bill is sufficiently workable to enable that opportunity to be taken”. He however confirmed that he would revisit the provision to ensure there is nothing inherent in the drafting of the Bill that would prevent the facility from being utilised.vi

The Committee understands that the Scottish Government’s policy intention is that, in judicial review proceedings on the UNCRC requirements, the test of ‘sufficient interest’ would determine which individuals and organisations have standing to raise court proceedings. The Committee asks the Scottish Government to provide greater clarity on its policy intention on the face of the Bill. In particular, the Committee asks the Scottish Government to bring forward an amendment at Stage 2, so that section 7 refers explicitly to the test of ‘sufficient interest’.

Time limits for bringing court proceedings

Section 7 of the Bill also sets out time limits for bringing court proceedings under the Bill in respect of an alleged breach of the public authority duty.

There is a default rule of one year (with the possibility of an extension) applying if there are not more stringent requirements associated with the court procedure being used.

For judicial review proceedings, the effect of section 7 is that the procedure's usual (short) three-month time limit would apply, unless the court extends the deadline.

When calculating the one-year time limit under section 7 of the Bill, any period for which a person is under 18 is to be excluded. This also applies to the three-month time limit for judicial review claims.

This means that, for example, if a child has his or her rights breached at the age of 5, he or she could wait until the age of 18 to challenge that breach in court. As under 18s are the rights holders in the UNCRC, this seems likely to impact on the relevant time limits in a significant number of cases.