Equalities and Human Rights Committee

Looking ahead to the Scottish Government’s Draft Budget 2020-21: Valuing the Third Sector

Introduction

Equalities and human rights budget work

Throughout this Parliamentary session the Equalities and Human Rights Committee has continued its focus on the key themes identified in its 2017 budget report Looking Ahead to the Scottish Government's Draft Budget 2018-19: Making the Most of Equalities and Human Rights Leversi:

Progress on developing equality and human rights budgeting

Improving equality data

Mainstreaming of equalities

The role of the Equality Budget Advisory Group

The National Performance Framework and Equality Outcomes

Public authority implementation of national equality and human rights priorities, and

Linking budget scrutiny to the Public Sector Equality Duty. The general duty requires public authorities to—

Eliminate discrimination, harassment and victimisation

Advance equality of opportunity between different groups

Foster good relations between different groups

Allocation of resources.

The Committee’s subsequent budget report enquired into how national and local priorities are delivered by public bodies through gathering evidence from local authorities about equalities and human rights decision-making and budget setting, as well as looking at the cumulative impact of budget setting (2018). During 2016, it also undertook a thematic inquiry Universities and disability: 2017-18 draft budget scrutiny.

Inquiry into third sector funding and accountability

This year the Committee has examined the delivery of national equalities and human rights outcomes more broadly. From its inquiry into Human Rights and the Scottish Parliament the Committee identified a clear need to investigate how the third sector is coping under tougher financial conditions. Reducing budgets impact both public service provision and availability of statutory funding for third sector organisations. The ability of the third sector to provide support to the most vulnerable in our society in uncertain economic times is crucial.

Uncertainty over the potential impact of Brexit on the Scottish economy, society, on equalities and human rights and the availability of funding, makes this inquiry into the third sector timely. The Committee notes the Finance and Constitution Committee’s Report on Funding of European Union Structural Fund priorities in Scotland, post-Brexit, and its focus on the UK Shared Prosperity fund proposed by the UK Government to fill the space left by EU Structural Funds post-Brexit.

Also, the third sector has a role in holding public bodies, including the Scottish Government, to account. The Getting Rights Right Report observed there was a need for civic society organisations to participate more fully with the treaty monitoring processes to increase accountability of the Scottish Government and its international human rights obligations. As such it recommended the Scottish Government and public authorities include resources for engagement with United Nations treaty monitoring in their funding to civic society organisations and for the Scottish Government to explore ways in which it could up-skill civic society around engagement with international treaty monitoring.

Moreover, the Scottish Government has stated the third sector has a vital role to play in progressing and realising the Scottish Government’s ambitions for people and communities across Scotland. Amongst other third sector priorities, the Scottish Government has committed to maximise the impact of the sector in reducing inequality, working with communities to tackle tough social issues at source.iv

Inquiry remit

In recognising the third sector as a key partner in delivering national equalities and human rights outcomes, and that public bodies need to be held accountable for their spending decisions, the Committee agreed a remit for this year’s budget scrutiny—

“To explore public sector funding to third sector organisations that deliver national equalities and human rights priorities, and to assess the accountability of public bodies partnering with the third sector in achieving better outcomes for those groups who have equality needs or require support to access their rights.”

To further support the inquiry, the Committee identified some key questions to investigate—

What are the key public policy areas where individuals and protected groups are struggling to access their rights?

Which groups of people are most likely to be affected and why?

What type of public sector funding (European, national or local) is provided to organisations to support vulnerable groups and those with protected characteristics to access public services?

Is the level of public sector funding provided enough to deliver national priorities and better outcomes for people and communities?

Are there public funding challenges for the third sector; if so what would be the implications for delivering equalities and human rights outcomes?

What type of administrative systems are in place to monitor the impact on equalities and human rights outcomes from public sector funding to the third sector?

What changes could be made to improve accountability for national priorities being delivered by the public sector in partnership with the third sector?

Engagement

Through follow-up work on Hidden Lives - New Beginnings: Destitution, asylum and insecure immigration status in Scotland. Report and the focus groups held as part of the inquiry into Human Rights and the Scottish Parliament, the Committee heard from third sector organisations that they were continually being required to fill service delivery gaps. It also heard from many individuals about the barriers they faced in accessing their rights to health treatment, an adequate standard of housing, and benefits payments, as well as their reliance on the third sector to advocate for them.

Call for views

Building on this evidence, the Committee launched a call for views on 14 June 2019. The closing date for submissions was Friday 23 August 2019 . The Committee received 41 responses and produced a summary of written evidence. The key themes emerging from the submissions were—

Increased demand for services, but reduced funding

Short-term funding

Perception of priority given to certain groups over others

Public funding of advocacy organisations and possible conflicts

Challenges aligning national ambitions to local delivery

Scottish Government budget information and access to equalities and human rights data

More public participation required in the budget process

How budgets are devised and scrutinised across the Scottish policy landscape

The effective use of equality impact assessments

This report looks at these themes in more detail.

Roundtable discussions

To provide the third sector with the opportunity to speak to us about the issues and challenges they face, the Committee worked with Glasgow Council for the Voluntary Sector (GCVS)i, Glasgow’s Third Sector Interface (TSI), and the Forth Valley TSIs (Falkirk, Stirling and Clackmannanshire) to hold events on 16 and 20 September 2019 respectively. These informed oral evidence sessions and this report. The Committee would like to thank the approximately 60 representatives who participated for sharing their views with us and to the TSIs who helped make the events happen. Notes of these events can be found on our website.

Oral evidence sessions

The Committee took oral evidence at its meetings on 26 September 2019 and 3 October 2019 where it heard from regulatory, audit and third sector representative organisations, as well as groups representing equalities and human rights views, and from public bodies covering health, social care and local government areas. A full list of those who gave evidence can be found at Annex A: Minutes of Committee Meetings.

Background

The third sector in Scotland

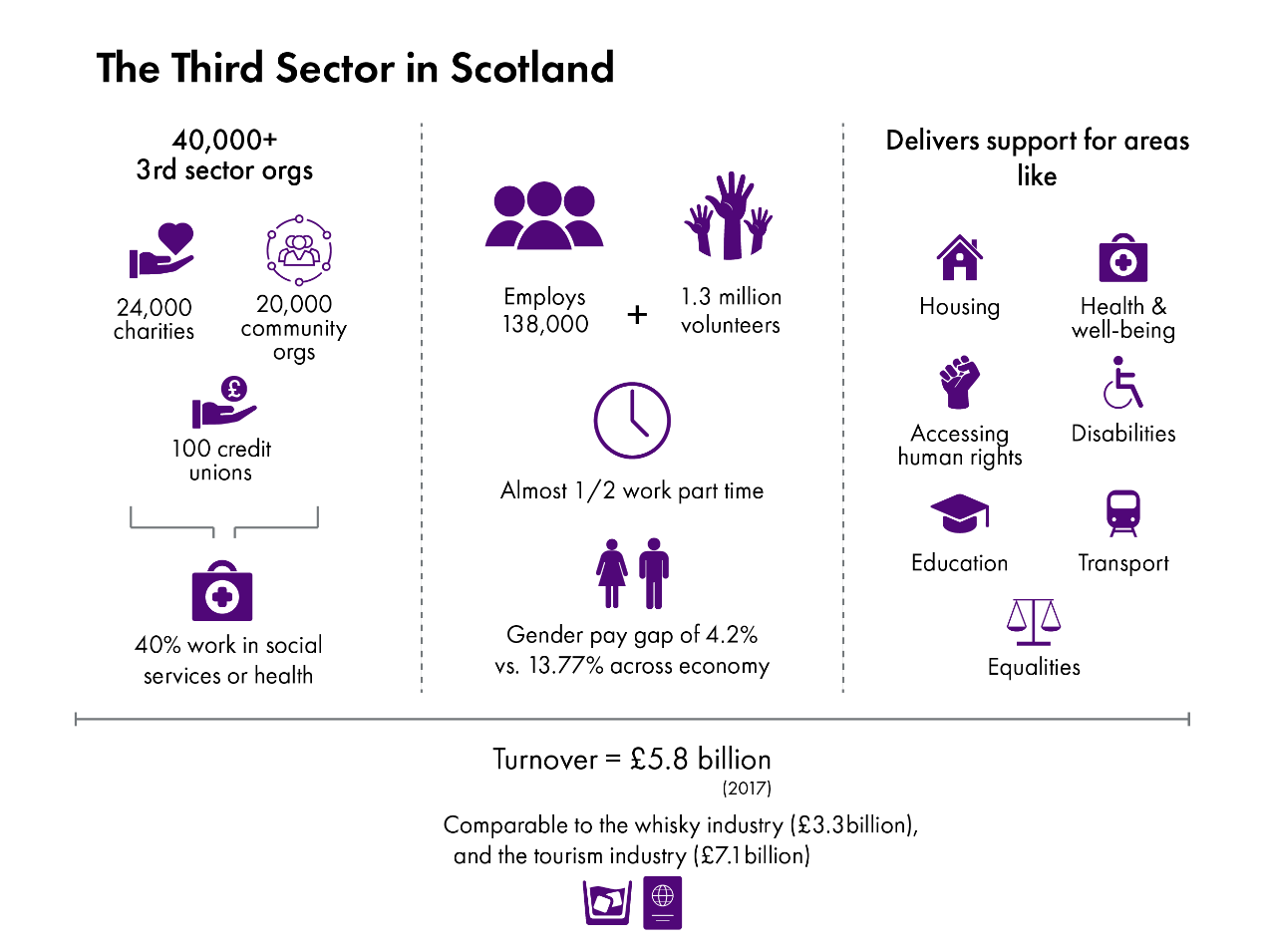

The “third sector” is made up of non-governmental and non-profit organisations, including charities, social enterprises, voluntary and community groups, credit unions and development trusts. Scottish Council for Voluntary Organisations (SCVO) estimates there are over 40,000 third sector organisations in Scotland. This includes approximately 24,000 charities, 20,000 community organisations and 100 credit unions. Over 40% of organisations work in either social services or health.

The third sector in Scotland had a turnover of £5.8 billion in 2017 (the most recent figures available). SCVO states that this is higher than the whisky industry, and not far behind the Scottish tourism sector.

According to Annual Population Survey (APS) figures analysed by the Scottish Government, the third sector in Scotland employed 86,500 people in 2018. SCVO cautions that this is an undercount, as the APS relies on respondents self-identifying as being employed by the sector. In a briefing published earlier this year, SCVO states that the sector has over 138,000 paid staff and approximately 1.3 million volunteers.

Almost half of all employees in the third sector (46%) work part-time, a significantly higher proportion than either the private sector (26%) or the public sector (28%). There is also a higher proportion of women working in the sector than in the workforce generally. Furthermore, almost 19% of employees in the third sector have a disability. This compares to 12% in the private sector and 13% in the public sector.

Analysis by SCVO shows that the gender pay gap is narrower in third sector organisations. Looking at some of the larger charities in Scotland, SCVO estimate that the pay gap in 2018 was 4.2% compared to 13.7% across the economy as a whole.

Median hourly pay in the third sector is slightly higher than in the private sector; £10.92 compared to £10.47. However, it is considerably lower than the median hourly pay in the public sector, which stood at £13.98 in 2018.iv

The Scottish Government budget and support for the third sector

The Scottish Government’s Promoting Equality and Human Rights budget is £24.6 million for this current financial year (2019/20), an increase of £1.9 million from 2018/19 (a real-terms increase of 6.2%). Over a ten-year period, however, this budget line has seen a real-terms cut of £2.6m (based on 18-19 prices), which equates to 10%.

| Cash, £m | Real terms (£m)* | Real terms % change on previous year | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2008-09 | 22.3 | 26.3 | |

| 2009-10 | 22.9 | 26.7 | 1.3% |

| 2010-11 | 20.1 | 22.9 | -13.8% |

| 2011-12 | 19.1 | 21.5 | -6.2% |

| 2012-13 | 19.7 | 21.7 | 1.1% |

| 2013-14 | 18.8 | 20.4 | -6.3% |

| 2014-15 | 21.7 | 23.2 | 14.0% |

| 2015-16 | 22.5 | 23.9 | 2.9% |

| 2016-17 | 23.8 | 24.7 | 3.4% |

| 2017-18 | 25.1 | 25.5 | 3.4% |

| 2018-19 (Budget) | 22.7 | 22.7 | -11.1% |

| 2019-20 (Budget) | 24.6 | 24.1 | 6.2% |

*2018-19 prices

This funding is aimed at supporting the equality infrastructure and the capacity of equality organisations. It also funds frontline activities to address violence against women and to support activities to promote equality, foster community cohesion, and address discrimination, hate crime and inequality.

The Scottish Government also has a specific third sector budget, which sits within the Communities and Local Government portfolio. This £24.9 million budget mainly supports local and national third sector infrastructure (including the third sector interface network), as well as helping the growth of the social enterprise sector.

Statutory funders

Public bodies that fund the third sector are commonly referred to as statutory funders. Statutory funders include the Scottish Government, local authorities, health boards, non-departmental public bodies and the EU through European Structural and Investment Funds.

Around 25% of third sector income comes from public sector contracts to carry out certain services, much with local authorities. Local authorities receive around 40% of their total revenue income from the Scottish Government each year in the form of the General Revenue Grant.

Contracts for the third sector are often accompanied by a Service Level Agreement. This is an agreement, in addition to the standard terms of the contract, that sets out the minimum quality standards that need to be met when delivering the service. COSLA provided specific examples of the type of services that would be contracted e.g. the provision of counselling for young people, community capacity building for older people and the provision of advice services to tackle poverty and financial exclusion. Much of the written evidence the Committee received highlighted social care, advocacy services, employability, housing and health as the main areas where the third sector was delivering services and projects on behalf of central government, local authorities and health boards.

Making contracts accessible to third sector organisations is part of the Scottish Government’s current Procurement Strategy and Community Benefit Clauses, established by the Procurement Reform (Scotland) Act 2014. This requires contracting authorities (under certain circumstances) to create the conditions for the third sector to deliver services. For example, since 2016 public bodies have been encouraged to ensure community benefit requirements are reflected throughout their procurement processes. They are also required to consider whether a contract can be divided into smaller contracts, thus improving the chances for smaller third sector organisations.

Public sector grants also provide significant funding to the third sector. Grants can come from local authorities, the NHS, Scottish Government, etc. and fund a range of national or local projects often linked to policy objectives. These could include specific projects for children or older people, advice services for particular groups, environmental projects or one-off trial projects.

Accessing rights

As the Committee learned from its previous human rights and budget work, fundamentally important areas of public policy, often aimed at supporting society’s most vulnerable and excluded people and communities, remain inaccessible to some individuals and groups. Groups found most likely to disengage or not seek access to services were marginalised groups such as asylum seekers or people with multiple protected characteristics.

Communication barriers still exist for people accessing key public services. People who are deaf, deafblind, hard of hearing or who do not have English as their first language were particularly affected. At the Glasgow TSI event the Committee heard examples of people being expected to source their own interpreters or not being provided with information in a way that worked for them. This made them wary about approaching services.

In addition (although the Committee notes learning about rights and citizenship is taking place in schools), it was reported that children in general were not aware of their rights, so could be excluded from planning decisions about how places like play areas are designed. Also highlighted was the right to education which the Committee was told was denied to some groups e.g. those with Autistic Spectrum Disorders or learning disabilities and deaf young people, because education services were not “geared up” to ensure that these children had the same opportunities as other children.

Older people often faced barriers to accessing the support they needed to have a good quality of life and to stay connected with their communities. The Committee heard that older people thought their views wouldn’t be listened to and were at times treated with disrespect, and that poor literacy, anxiety and poor mental health made them less likely to engage with public services.

The Committee heard of times when families or individuals did have an awareness of their human rights, but were told by professionals that they were not entitled to support. Several of the group discussions at the Glasgow TSI event described how individuals and families felt “downtrodden” having been continually told they were not entitled to support – despite the existence of legislation which stated the contrary.

Moreover, the Committee heard of times when public bodies’ complaints procedures were viewed as being loaded against families. Participants at the Glasgow TSI event described how people who did challenge such bodies were treated as, and branded as, being “difficult” and “combative”.

Conclusion

The issues highlighted in this inquiry are similar to those raised at the Committee’s earliest stakeholder evidence sessions in 2016 and limited progress has been made. To effectively provide for their communities’ needs, public bodies must better understand their communities and continue to innovate.

Funding challenges

Increasing demand for services, reduced funding

Almost all written submissions highlighted some funding challenges or expressed the view that public funding for the third sector should be increased. Age Scotland believed that the voluntary sector was often left to “plug the gap” for services that were previously publicly funded, whilst other groups faced increasing demand at the same time as their budgets were reduced. The Health and Social Care Alliance (HSCAS) reported a growing trend for local authorities to demand that “third sector organisations deliver services ever more cheaply”.

Other organisations, such as Equate Scotland, highlighted the impact reduced funding had on the services and activities they provided: “we can no longer provide one to one career clinics which support women seeking work or experiencing difficulties at work…as costs of delivery, staffing and operations have increased, and funding has remained static”. They mentioned other third sector organisations that had experienced even tighter budget situations, with services and activities either being limited or stopped.

There is a concern that people in need could be turned away from the services that were meant to help them. HSCAS argued that tighter local authority budgets had affected third sector provision, resulting in poorer experiences for those accessing services. For example, service users faced more restrictive eligibility criteria, increased charges, and growing infringements of their human rights.

Shaben Begum, Scottish Independent Advocacy Alliance (SIAA), reported that her organisation was experiencing increased demand because people had not been able to access the services that they had a right to access. She added people were unaware of their rights until in crisis and explained the “threshold to access some services is quite high, and that is reflected in people’s access of independent advocacy”.

COSLA argued funding of third sector organisations fell predominantly within the “unprotected” portion of council budgets. In the 2019/20 budget, 61% of local authority budgets were protected as a result of national priorities and demand on services e.g. social care. Only 39% were unprotected.Therefore when savings had to be made, COSLA said “councils have no choice but to take any necessary savings from service areas that fall within the non-protected area” i.e. wellbeing, infrastructure, the economy and the creation of sustainable communities. Cuts were therefore amplified in these areas, as a 2% cut in overall budgets became at least a 5% saving from non-protected areas. COSLA called for investment in local government, because it was “fundamental to specific consideration about funding to third sector organisations that deliver national equalities and human rights priorities”.

Funding is not the only issue that could affect the delivery of services. Linda Owen, Dumfries and Galloway Health and Social Care Partnership, explained Dumfries and Galloway had an increasing older population as the number of young people decreased. She said “even if we had more money, at times, we do not have the bodies. Part of the challenge is to do with our rurality. We are finding it very difficult to fill packages in our more rural areas”.

At the Glasgow TSI event, participants said funding reductions affected their ability to be a true voice for the sector and to defend the sector’s work or challenge poor treatment. Indeed, it was questioned whether it was the role of the third sector to deliver public services. In response, however, Jude Turbyne, Office of the Scottish Charity Regulator (OSCR) said that charities were “very well placed to deliver services” and that they definitely had a role to play, although how that role should be structured was a different question. Paul Bradley, Scottish Council for Voluntary Organisations (SCVO) agreed, saying they should “absolutely” be delivering public services, but he cautioned “if our values keep being chipped away at, that could lead to contracts being given back to local authorities”.

Short-term funding for third sector organisations

Short-term public funding, sometimes for one year or less, means that organisations can struggle to deliver projects and plan their workforces. According to the Scottish Independent Advocacy Alliance (SIAA), this situation could lead to job insecurity, high staff turnover and a resulting loss of knowledge and expertise. The Parliament has repeatedly heard concerns about this issue over the period of devolution; however, it is still a substantial concern for the sector.

For these organisations, the resulting time and money devoted to recruitment and training adds a further burden, diverting resources away from frontline delivery. The Scottish Commission for Learning Disability stated that short term year-on-year funding means that some of their projects are “often very precarious”, thus making “long term planning to progressively realise greater equality and human rights impossible”.

The negative consequences of short-term funding include:

A struggle to maintain momentum and engagement with clients and communities

Driving away talent to better paid and more secure sectors

A struggle to ensure an inclusive, fair work environment.

Participants at the Glasgow TSI event spoke about the tough funding situation for the third sector, particularly smaller organisations. Many spent their time “running around looking for funding”, which had an impact on staff morale, resources and service delivery. Participants at the Forth Valley TSI event suggested the optimum length of funded contracts should be five years. Funding over a five-year period, they said, would allow organisations to employ experienced staff and would free up time for managers to focus on the operational service aspects of the organisation.

COSLA argued that councils were simply passing on the pressures and impacts they themselves were experiencing due to cuts in the funding they received from the Scottish Government, and the single-year nature of their funding—

Councils are not in the position to guarantee longer-term budgets for partners. The impact of cuts can, therefore, cause unpredictability of short-term funding arrangements and make it difficult for these organisations to plan for the longer term which can impact on our ability to deliver locally in relation to CPP Local Outcome Improvement plans, on the NPF and other equalities and human rights priorities.

Jude Turbyne, OSCR, emphasised, “even with a three-year budget cycle, we would have only about 12 to 15 months in which we were not coming out of a cycle or going into another one” but recognised having a budget cycle of that length would still make a “massive difference”. She challenged funders to look at different models of funding, for example, a five-to-10-year working model that could be reviewed at regular points. The benefits of this approach, she explained, were that it would be better to deal with intersectional needs and longer-term outcomes.

Antony Clark, Audit Scotland, stressed that although long-term funding is good for dealing with long-term outcomes, it needs to be balanced against flexibility and strategic commissioning.

Competition for funding

Complexity of application/bidding processes

At the Forth Valley TSI event Committee Members heard that organisations must complete quite complex application processes for grant funding or spend a lot of time preparing tender bids for public contracts. This, participants believed, favoured larger organisations with dedicated staff to prepare applications, whereas some participants considered smaller organisations were often better placed to support vulnerable people and groups but fail to win contracts.

Jude Turbyne, OSCR, argued, “if we want to work with smaller organisations, we have to build a different model of partnership—a different way of working with them—to allow them to get to that stage”.

Helen Forrest, Children’s Health Scotland, called for greater transparency of the funding application process. She highlighted the difficulty in describing outcomes on application forms and explained funders looked at the numbers not at the outcome for the individual. This point was also raised at the Glasgow TSI event. Participants said soft outcomes for people and communities supported by charities in the city of Glasgow needed to be recognised e.g. the ability to use transport, the ability to continue caring or developing increased confidence because such outcomes can be transformative.

In relation to the health improvement agenda, Professor Alison McCallum, Director of Public Health and Health Policy, NHS Lothian, said of the funding and procurement mechanisms, “they need to enable full participation of the third sector and not lead us down a route where we end up with organisations that are more commercially focused than care and support focused”.

The accessibility of application processes is also an area of concern. Elric Honoré, Fife Centre for Equalities, provided examples of how challenging it was for smaller equality groups to access funding—

For example, the form for a £10,000 pot will not be in British Sign Language, and the native language of those in the deaf club is not English. Third sector interfaces do not write policies or make applications on behalf of other organisations, and the English of the people in those organisations might not be good enough for the forms, because that is not their native language.

Partnership working

There is an acknowledgement that third sector organisations should be looking towards collaboration. For example, co-location of third sector organisations could be beneficial, as it could cut overhead costs, make working together to address shared issues easier, enable information sharing and help build trust.

While there was a real desire and enthusiasm for partnership working, participants at the Forth Valley TSI event said that competition can prevent it from happening. Participants questioned how partnership could take place between third sector organisations when they were competing for the same pot of money. One organisation commented “it’s like a war”. Fighting over funding had led to distrust in the sector.

GCVS also cautioned that any move by public bodies and other funders to combine a variety of funds into one pot could have the unintended effect of cutting the total amount of funding available to organisations and highlighted the People in Communities fund as an example of this.

Conclusion

The stretched nature of third sector funding and short-term funding cycles is causing “fragility” in some third sector organisations. Reductions in local government budgets, and a lack of flexibility in where savings can be made, is also contributing to reduced funding for the third sector.

Competition for funding to survive and continue supporting people could lead organisations to stray away from their purpose, leading to an erosion of third sector values. Also, equalities groups are being pitted against each other in funding streams and the tendering and procurement process leaves equalities and rights “to the market”.

The competitive funding environment also puts smaller third sector organisations at a disadvantage. Competition between organisations seems to be disincentivising partnership working, despite the apparent enthusiasm of all parties for closer and more trusting relationships.

The Committee calls on the Scottish Government to work with other statutory funders to consider how partnership working can be encouraged in a competitive funding environment. The Committee asks the Scottish Government to set out how it is doing this currently, and its plans for future improvement.

Short term funding impacts on third sector organisations’ ability to retain and develop staff. Some staff are being employed as supply workers on zero hours contracts creating a constant churn that affects organisations’ ability to plan ahead. Third sector organisations consider five years to be optimum length of funding. As far back as 2011, the Christie Commission heard evidence “on the benefits of multi-year contracts for service providers to provide stability, and underpin quality and innovation. The Fairer Funding Statement, signed by the STUC, SCVO, CCPS, UNITE and UNISON, calls for five-year contracts for third sector providers".

The Committee acknowledges that statutory funders are themselves mostly funded on a yearly basis and this places some restrictions on their flexibility to fund longer-term. In relation to flexibility, the Committee notes COSLA’s position that local authorities have less flexibility because the non-protected part of their budget is reducing. Balanced against this, however, is the 2017 Scottish Government announcement that its Equality Budget would move from one-year to three-year cycles, “providing vital reassurance to organisations that prevent violence against women and girls, as well as those who work to tackle hate crime and discrimination, increase representation and enhance community cohesion".

The Committee welcomes the Scottish Government’s move to a three-year funding model and the example this sets to other statutory funders. There are a number of clear benefits to be achieved for both organisations and commissioners from having longer-term funding, not least better outcomes for those being supported through projects and services. The Committee recognises that longer term strategic funding is difficult to achieve, but nonetheless there is scope to develop more flexible models of funding, as highlighted by OSCR.

The Committee asks the Scottish Government to set up a working group, involving key stakeholders, to examine the longer-term funding models available to statutory funders and for its conclusions to be made available before the end of this Parliamentary session.

In the meantime, the Committee believes there are actions that can be taken now to redress the balance for smaller third sector organisations providing support to their communities and those organisations that require assistance to make applications.

The Committee asks the Scottish Government and other statutory funders to alert organisations well in advance of seeking applications, and to work together to consider best practice around notification of funding applications. Sufficient time should be given to allow organisations to prepare their applications, particularly if they require language assistance, and to facilitate opportunities for third sector organisations to come together and apply as partnerships.

Fife Centre for Equalities reported how challenging it was for smaller equality groups to access funding, particularly when English wasn’t their first language or where those applying were, for example, deaf and needed application forms translated. Janis McDonald, deafscotland, described the scale of the task, she stated “it is almost as if there are two populations in Scotland—the hearing population and those who have challenges”. BEMIS argued there was a lack of understanding of race, equality and human rights among public bodies and agencies, which could deprive a significant number of diverse groups from benefiting or acquiring relevant funding to support their respective communities.

One of the key messages from the Glasgow TSI event on statutory funders applications was “they are off-putting, difficult and ask the wrong questions”.

The Committee considers more can be done to make funders’ application processes more accessible to more diverse groups.

The Committee agrees that the application process for statutory funds must meet inclusive communications standards and as a matter of urgency, statutory funders should review their processes to ensure that all third sector groups, irrespective of their language or other systemic barriers, have an equal opportunity to apply for funding.

National Priorities

Gap between national priorities and local delivery

Reduced budgets and short-term funding could be contributing to a gap between national policy aims and the experiences of the third sector and service users “on the ground”. Participants at the Glasgow TSI event emphasised that they understood the Government’s message and priorities about equalities and human rights, but said implementation was difficult due to insecurity and inadequacy of funding. GCVS commented that the Scottish Government would not meet its strategic objectives on health, inequalities etc. without an adequately resourced third sector.

Paul Bradley, SCVO, remarked that “Scotland has world-leading legislation and fantastic frameworks, programmes and policies, but delivery requires resourcing”. He cited Scotland’s national action plan for human rights (SNAP), launched in 2013, as a good example, but advised that it had no dedicated resource and budget. He added there were similar examples, “we have world-leading legislation on homelessness, last year, more than 3,000 people had their requests for temporary accommodation declined”. Additional factors that contributed to the gap were, he explained, a lack of cohesion between policy development, delivery and implementation.

Janis McDonald, deafscotland, echoed SCVO’s concerns about the funding of SNAP, saying, “we know for sure that there has been a gap in SNAP funding. It is important that the second phase of SNAP is properly supported and resourced by the Government”.

Several examples of the failure of the system to protect rights were provided by those who attended the Glasgow TSI event—

A number of participants described those they support as being “afraid” of public services – housing, immigration, social security, criminal justice and social care were mentioned specifically;

Disabled women not having access to key health services/screening;

Women fleeing violence not being able to access housing or other key services;

Disabled people losing critical overnight support;

Social care being deemed too costly and therefore increasing institutionalisation, which goes against wishes of people/families to stay together;

People not being fed properly as paid carers have limited time in their homes;

Poorer outcomes in education for disabled children and those with complex additional support needs;

The poor experience of children and young people in the justice system;

The continued existence of poverty and deprivation in Scotland – how that erodes access to rights for women, children, refugees/asylum seekers and others;

The specific experience of asylum seekers was mentioned particularly in relation to those affected by lockouts when their claim for asylum is denied.

In last year’s audit of Glasgow City Council, Audit Scotland noted some “challenges” in the relationship between the council and the third sector—

Some third sector groups have not always felt themselves to be an equal partner in the CPP [Community Planning Partnership], for example they did not feel as included in the development of the Community Plan as other partners. Both the council and third sector partners consider that the third sector’s potential is not being tapped into.

Bernadette Monaghan, Glasgow City Council, confirmed action was taking place on community planning and that community engagement was at the heart of everything the council and it arms-length organisations, like Glasgow Life, was doing. The mainstreaming of participatory budgeting, she advised, was the next phase.

Equality impact assessments

GCVS believed decisions on social care could have a significant impact on those with disabilities, as well as on unpaid carers; however, they claimed that cuts at local authority level were sometimes proposed and considered without full equality impact assessments. They believed that the Glasgow Health and Social Care Partnership “is gradually improving on this front, but often provides partial EQIAs with no in-depth assessment of what changes to services might mean for individuals on the ground”.

Linda Owens, Dumfries and Galloway Health and Social Care Partnership, talked about action taken by their integration joint board, which did not accept papers without an impact assessment because the “board was finding that sometimes it was getting impact assessments and sometimes it was not”.

More generally, Tim Kendrick, Fife Community Planning Partnership, commented equality should be part of the process, “not just tagged on at the end. When officers are asked to explore potential mitigation measures, for example, they should actually do that”.

Professor Alison McCallum, NHS Lothian, said it was important to ensure that public bodies were starting from an integrated impact assessment looking at protected groups, including the fairer Scotland duty, children’s rights, climate change and sustainability, “having considered what the likely outcomes are and redesigned things at the outset”.

The Scottish Independent Advocacy Alliance also called for “increased robustness in the requirements for the public sector to have effective, current and co-produced Equality Impact Assessments in place for all elements of the delivery of public services”.

Other organisations and individuals submitting written evidence argued that third sector organisations are providing front line services, funded by public money, so should be subject to the same public sector equality duties as public bodies. This should include requirements to undertake full equality impact assessments.

Data and evidence-based policy

Several organisations participating in the Forth Valley TSI event questioned whether any of the monitoring undertaken by the third sector was being checked or made use of by statutory funders to inform policy and/or services. It seemed significant amounts of data were collected locally but were not used to inform local or central equalities or human rights policies.

In the experience of Elric Honoré, Fife Centre for Equalities, there was inadequate provision of detailed equality evidence on the delivery of services from both the public sector and the third sector in relation to the protected characteristics. He suggested both sectors needed to look at what “right” was being sought and the characteristics of the person, otherwise you couldn’t gauge what was happening in the public sector or the third sector.

On the type of data required by statutory funders and the resources needed to collect the data, participants at the Forth Valley TSI event suggested there were alternative ways to evaluate the third sector’s work e.g. annual reports, videos, and service users’ views. It was emphasised that as third sector organisations worked with communities, they produced rich data, but were scared to share it with other organisations because of competition for funding. They also suggested the Scottish Government could take a broader view of data. Concern was expressed over how the Scottish Government viewed data submitted by third sector organisations.

In terms of national policy development, there were calls for the Scottish Government to consider how it consulted with the third sector. Forth Valley TSI event participants believed organisations should be funded to participate or undertake capacity-building work to inform the consultation processes and to enrich the participants’ experience.

Social care and the third sector

Delivery of social care services is a policy area where the third sector is central. Indeed, more than half of all third sector employees work in social care or health organisations, in roles such as care assistants, support workers, nursing, social work, nursery and childcare workers, and health and mental health support.

In recent years the social care system has been redesigned with the intention of moving towards a more outcomes - and human rights - focused agenda. This was driven by the desire to support older people, disabled people and other service users to participate actively in their communities and their care needs.

Reforms included the development of more integrated health and social care and the introduction of self-directed support (SDS). The Coalition of Care and Support Providers in Scotland (CCSPS) helpfully summarised SDS—

The Social Care (Self-Directed Support) Scotland Act of 2013 placed a statutory duty on local authorities to present four options of care to individuals with social care needs: Option 1 where the individual/carer arranges the support and manages the budget; Option 2 where the individual chooses the support and the local authority or other organisation arranges support and manages the budget; Option 3 where authority chooses and arranges support; and Option 4 which is a mixture of one or more of the 3 options. The legislation sets out to fundamentally change how social care is planned and provided within Scotland.

SDS was designed so service users were equal partners (alongside relevant professionals) in determining their own social care needs and controlling how those needs were met.

The intentions behind these reforms were mostly welcomed. The Scottish Human Rights Commission (SHRC) considered SDS a “good model of person-centred empowerment” – however, implementation and local delivery have had their challenges. Audit Scotland, in its progress report on SDS in 2017, identified both budget constraints and approaches to commissioning as restricting how much choice and control service users actually had. Likewise, the Care Inspectorate found that more needed to be done to fully realise the potential of “supporting the transformation of social care delivery in Scotland” .

Reforms to the structure of Scotland’s social care system, namely the move towards health and social care integration, had also encountered criticism from some sources. While there were some examples of good practice, in its progress report published last November, Audit Scotland called for integration authorities, councils and NHS boards to work more closely with the third sector. They also reported that some third sector providers often felt their views were not sought or were not valued, despite having innovative ideas on how to improve local services.

Concerns about the provision of respite for carers under SDS were raised at the Forth Valley TSI event. Carers were entitled to respite; however, participants said the system made it difficult to obtain respite because the options available were too expensive. When carers asked for less expensive alternatives these were deemed not acceptable under the system.

Participants also reflected that SDS was difficult to navigate. Individuals didn’t know their personal budget under the system, so it made choosing care support difficult. The system was inaccessible for people with mental health issues and there was inconsistency across authorities; each took a different approach to their charging policy. Some participants believed that certain authorities had introduced a charge because it reduced demand for services, as authorities couldn’t afford to provide them.

Participants at the Glasgow TSI event commented that legislation was great, but practice less so. Participants described lengthy waiting lists (six months plus) for accessing self-directed support.

Third sector organisations at the Forth Valley TSI event argued they needed to be “not just at the table, but to have a meaningful say in designing and developing solutions for communities”.

In relation to health and social care, Linda Owens, Dumfries and Galloway Health and Social Care Partnership, confirmed that third sector representatives do not have voting rights, as the Public Bodies (Joint Working) (Scotland) Act 2014 stipulated who should be on the strategic planning group and the integration joint board.

Liz McEntee, GCVS, argued it was not helpful to have just one non-voting third sector representative on an integration joint board. She said, “if the third sector does not have voting rights, it clearly limits our ability to influence decision making”. Furthermore, she explained there was an issue about third sector representation on local government and health board committees as “third sector organisations are having to give up time, but not on a resourced basis, and that represents a real challenge."

Fair work concerns

Third sector organisations told us that short-term funding and budget reductions were leading to insecure employment, as well as other working conditions which did not meet the Scottish Government’s definition of “fair work”.

According to participants at the Forth Valley TSI, funding on the whole did not include a proportion for the organisational running costs—

It was identified that roughly 20% of costs went to paying wages, staff training or undertaking recruitment. UK policy changes had also had an impact on costs, for example, provision of workplace pensions had increased costs to some third sector organisations. There had been no change to funding to reflect this cost. Also, the public sector had received a 3% pay increase, but third sector organisations noted it was difficult for them to do the same for their staff.

Talat Yaqoob, Equate Scotland, said staff development opportunities and growth opportunities were stifled by insecurity of funding. She added that as “an equalities organisation, we should provide those opportunities, given that equalities organisations are about the workplace”.Paul Bradley, SCVO was also concerned about fair work. He stated “if our organisations are calling for the living wage but they have people on zero hours contracts whom they are not paying the living wage” then that represented an erosion of the sector’s values.

Social care

HSCAS described the challenges faced by employers and employees in social care, where staff often performed roles that were low paid, carried low status and attracted too little support. At the Glasgow TSI event Committee Members heard several stories about insecure employment and people often working extremely long hours.

The Fair Work Convention, set-up by the Scottish Government in 2015, noted significant challenges experienced by many frontline staff in the social care sector. They identified a lack of security for social care staff; poor terms and conditions; significant difficulties in staff recruitment and retention, and “commissioning / procurement practices which seem to work against both fair work and person-centred care”.

Henry Simmons, co-chair of the Fair Work Convention Social Care Inquiry and chief executive of Alzheimer’s Scotland, argued in Third Force News that the current method of competitive tendering for social care contracts has “created a model of employment that transfers the burden of risk of unpredictable social care demand and cost almost entirely onto the workforce”.

In 2016 the Scottish Government announced that all social care staff providing publicly-funded services should be paid (at least) the “real living wage”. According to Third Force News (TFN), the Scottish Government made £255 million available over three years to help public, private and third sector social care bodies increase wages, including covering increased National Insurance and pension contributions.

However, TFN also reported concerns from the Coalition of Care and Support Providers in Scotland (CCPS) that local authorities weren’t paying care providers enough for the adult social care living wage policy to be successfully implemented. Research conducted by Strathclyde University for CCPS found that most local authorities were not proactively monitoring whether providers were paying the Living Wage to workers, and there was no evidence that the Scottish Government or Integrated Joint Boards were monitoring whether local authorities were adequately funding providers to pay the Living Wage.

Preventative spending

The Scottish Government has committed to reforming how public services use resources to address demographic and resource pressures to improve outcomes, especially for those whose wellbeing and life chances are poorest. According to its Medium-Term Financial Strategy: May 2018, this commitment is rooted in the Christie Commission's four key principles of prevention, performance, partnership and people. This recognises that public services can improve outcomes and work more efficiently when they work together to shape joined-up services around the distinctive needs of communities, including building preventative approaches to strengthen positive outcomes and tackle persistent inequalities.

Advocacy support has increasingly becoming a firefighting, damage control service. Shaben Begum, SIAA, said people only became aware of the service “when they are seriously unwell or when they are in danger of losing their tenancy, home or children. We cannot do the preventative work that we are supposed to be doing because we are too busy fighting for people to hold on to their liberty”.

Also, sometimes a preventative approach could “uncover unmet and urgent need”, as raised at the Forth Valley TSI event by one participant working in addictions support and counselling. They advised preventative spending could, for example, be directed towards early childhood experience, poverty or mental health issues to address addictions, but these were complex areas requiring substantial investment and resources did not appear to be available. Other participants recognised that with already limited resources and with being kept busy by being responsive there was not time to develop and deliver the more preventative services they desired.

Conclusion

Scotland has “world-leading” legislation, policies and frameworks but the evidence received shows there are areas of public policy that seem to consistently fall short of the policy intention.

Reduced budgets and short-term funding are contributing to the gap between national policy aims and the experiences of the third sector and service users “on the ground”.

Also, equality impact assessments must be taken forward consistently across all public services. It is imperative financial decisions, including service redesign or service cuts, are not taken without an impact assessment. This is an area where the Committee has repeatedly heard progress is not being made. The third sector has lots of information on the communities they serve. This should inform the impact assessment process and the third sector have said they are willing to help co-produce impact assessments.

In relation to the Public Sector Equality Duties, the Scottish Government introduced the Scottish duties in 2013, with the aim of helping public bodies to work on equality. The Equality and Human Rights Commission produced a report, Effectiveness of the PSED Specific Duties in Scotland, which they envisaged would inform the Scottish Government’s review which was announced for 2019.

The Committee asks the Scottish Government what leadership it is showing to other public bodies on undertaking impact assessments and for a progress report on its review of the Public Sector Equality Duty specific duties in Scotland.

Audits have shown varied performance when it comes to health and social care integration, particularly relating to partnership with the third sector. It is concerning that parts of the system that should be best at rights don’t seem to be. People, communities and the third sector need to be able to hold these systems to account to meet the rights of, amongst others, disabled and older people and unpaid carers.

The third sector said its ability to influence decision-making is impacted by not having voting rights in relation to, for example, integration of health and care. This, they believe, represents a “democratic deficit”. The Committee notes there are examples where other representatives like trade unions and religious representatives, under certain circumstances have voting rights.

The Committee asks the Scottish Government to investigate how the third sector’s role in decision-making can be strengthened. This should include examining legislation, such as the Public Bodies (Joint Working) (Scotland) Act 2014, which excludes the third sector from having voting rights.

A key theme from this inquiry is the erosion of third sector values. This is demonstrated most clearly through the third sectors’ fair work concerns. Issues include low pay, difficult working conditions, insecure and temporary employment. It is not acceptable for the employees, the employers and the sustainability of the third sector organisations for this situation to continue. Particularly as the sector is the principal employer of women and people with a disability. The Committee believes the third sector, alongside Scotland’s public sector, should be a leading example of what fair work looks like and what it can achieve.

The Scottish Government has frequently highlighted the importance of prevention and the third sector’s role in supporting a more preventative approach to policy delivery. However, the Committee heard organisations can spend much of their time dealing with “acute cases”, i.e. providing immediate and reactive support to people in crisis. It is clear from the experiences of the people working in the third sector that there is no shortage of energy and enthusiasm to help people deal with their circumstances; however, organisations would like to do more preventative work, but cannot due to more pressing demands. Cross cutting approaches seem to be rare, but necessary to achieve the systems and approaches outlined by the Christie Commission. This is a shared challenge between the Scottish Government, other statutory funders and the third sector to reform the implementation of services in partnership, with users at the heart of the process.

The Committee asks the Scottish Government what plans it has to take action to address the gap between national priorities and local delivery.

According to the Scottish Government, its equalities and human rights budget “supports the drive for social justice, economic and inclusive growth, and community resilience and empowerment”. However, it is only 0.07% of the total Scottish Government discretionary budget.

If budgets are the most concrete demonstration of a government’s priorities, then this low level of funding for equalities and human rights needs to be reviewed. The three-year nature of the equalities budget is welcome; however, the Committee would like to see more equalities organisations benefitting from this funding. As such, the Scottish Government should increase this budget and invest more in Scotland’s equality infrastructure and equalities organisations.

Likewise, the Committee has seen the importance of the third sector to communities and vulnerable people across Scotland. The Committee has heard the competitive environment for grant funding and contracts harms the interests of third sector organisations and the communities they exist to support.

More support should be available for smaller organisations, as many are currently struggling with insecure funding, fair work issues and service continuity. Scotland’s third sector interfaces have a key role to play in encouraging more collaboration between smaller organisations, as well as helping them discover, apply for and win public sector contracts. Again, the dedicated third sector budget line for the third sector is small compared to the overall Scottish Government budget (£25m, or 0.07% of total SG budget). The Committee would like to see a real drive to strengthen the third sector in Scotland with additional funding available to promote and facilitate co-operation and collaboration.

The Committee asks the Scottish Government to increase the funding it provides directly to the third sector and equalities budget lines.

The Budget Process Review Group encourages the Parliament’s committees to be more outcomes-focussed in their budget scrutiny. One outcome consistently heard through this inquiry is that reduced Scottish Government funding for local government has a significant and detrimental impact on many third sector organisations.

Councils are under pressure to make savings and this influences how they approach the commissioning of services in their areas. There is a limit to “more for less”, and the Committee found third sector organisations across many sectors – not least the social care sector – are feeling the brunt of these budget pressures. They are struggling to provide adequate services for the prices councils are able/willing to pay. This situation needs to be reviewed urgently.

The Committee seeks an assurance from the Scottish Government that as a matter of urgency, it will review with its partners (including local government), how the third sector is funded, in order to minimise any negative impact on the third sector and its service users.

The Budget Process

Participation in budget processes

The Scottish Budget

In relation to the Scottish budget, SCVO argued that there were few opportunities for the public to engage in the process. They called for “appropriate mechanisms and inclusive processes” to allow the third sector and the public to have a meaningful say in all stages of the budget process. Paul Bradley, SCVO, said “we do not measure the process around the Scottish budget” although he acknowledged some progress on human rights indicators. He added that understanding the budget is not only important for members of the public but also for the third sector, clarifying if the sector doesn’t understand the budget, then following the money is hard. He urged the Scottish Government to look at international models.

Antony Clark, Audit Scotland, drew parallels with community empowerment and the opportunity for participatory budgeting, which was an important area for both them and the Scottish Government. He was aware of local authorities using new approaches, like holding day sessions and working with community groups. The third sector were often involved in such discussions, although he appreciated that it was not easy to find the right way to have conversations that created meaningful and concrete proposals for change, but local authorities were trying.

Local authority – participatory budgeting

The issue of how local authority participatory budgeting was working was raised at both the Glasgow and Forth Valley TSI events. A Forth Valley participant described the process as subjective and a “horrible experience”, noting it should be a supportive environment not competitive. Experience had shown that the method used was key and effort had to be put into preparing people for the process. It was acknowledged that local government wanted lived experience, but they needed to invest in supporting people to share their experience, particularly if they wanted the experiences of the hardest to reach people as opposed to the professional service user.

Participants at the Glasgow TSI event said that in Glasgow, concern centred around the challenges for equality/under-represented groups to participate. They had no voice or choice in how money was spent locally. Participants stated if disabled people or older people in particular were losing social care support, how could they then take part in participatory budgeting discussions? Also, people were “dislocated from wider budgeting processes”, so pushing surveys and budget debates online excluded those who didn’t have internet connections or who couldn’t use computers.

Conclusion

It is recognised that the Scottish Budget process can be opaque to the public and key stakeholders, such as third sector organisations. Clearly, to assist with scrutiny, the Scottish Parliament has a role in making the budget process more accessible through the work of Parliamentary committees. The Committee is hopeful that work undertaken this year will have encouraged more people to get involved in scrutiny of the Scottish budget. However, the Scottish Government needs to do more to make public money more visible to stakeholders, so individuals can participate in the process.

The inclusion of the human rights indicators in the National Performance Framework is encouraging. While it will take time for these to be embedded in the process, it must be ensured that the valuable data held in communities is informing the budget process and that the third sector is able to share these views with policy-makers.

The Committee notes that a burden is being placed on the third sector to participate in the development of public policy by asking them to be involved in various committees for health and social care, community planning etc. while also facilitating service users to share their views. A further key message from this inquiry is “volunteers aren’t free”. At the individual level, they need time and resources to be trained and developed. At an organisational level, organisations contribute to the many policy working groups and committees, but are perhaps not valued highly enough to be recompensed for their time and knowledge.

The Committee asks the Scottish Government what action it will take to facilitate greater public and third sector participation in the Scottish Budget process.

The Committee asks the Scottish Government to direct or encourage a greater focus on human rights and partnerships with the third sector within the budget allocation process. For example, could this be done when public bodies find out their funding settlement through budget letters/guidance.

The Committee recognises a participative approach to public policy development will place an additional pressure on the third sector. It therefore asks the Scottish Government, in undertaking its review of resourcing of the third sector, to include consideration of this issue.

Human rights budgeting and equality budgeting

A significant number of written submissions call for changes to be made to the way budgets are devised and scrutinised across the Scottish policy landscape. The Scottish Human Rights Commission in particular argued that the budget is rarely viewed through a human rights lens, and it was their belief that the Scottish Government should adopt a human rights-based approach to budgeting “in order to ensure that rights on paper become rights in practice”.

HSCAS defined human rights-based budgeting as—

the questioning of assumptions about the budget setting processes – moving the overall goals away from simply being focused on GDP, for example, and towards the realisation of rights as well as active participation of rights holders in the process.

In the area of social care, for example, HSCAS said this could extend to exploring the impact budget decisions have on the rights of workers and unpaid carers, as well as on service users.

GCVS believed some public bodies saw human rights as a risk. For example, it could result in higher costs to them, yet GCVS considered ensuring services start from an inclusive, rights-based approach could be a “game changer”. They called on MSPs to use the intelligence from their casework to better hold Ministers and public bodies to account. An overview of the experience of MSPs and the key issues that emerge consistently from constituents could provide useful information about human rights in Scotland.

Following the money from principle to outcome was currently impossible, according to GCVS. They commented small pots of money given out to try to change the experience of marginalised groups e.g. homeless people, were not always conducive to system and culture change. GCVS said there needed to be real investment in areas such as social care, housing, family support, and community services.

BEMIS argued that despite the Scottish Government’s commitments in relation to race, equality and human rights, including the “International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination” – there remained a critical void in the implementation of the treaties’ basic functions. This was despite them already being incorporated into UK Human Rights and Equalities law and Scots criminal law.

Engender called for a full gender analysis of the Scottish Budget, where the cumulative impact of spending decisions on women’s equality is considered. This was echoed by Scottish Women’s Aid who wanted to see gender budget analysis at every stage of the budget process. They believed the Parliament should have a key role in scrutinising the process, ensuring competent gender equality analysis is carried out across policy portfolios to hold the Scottish Government to account.

Conclusion

A strong focus on rights from the Scottish Government is welcome. The Committee received a clear message, however, that talk about rights at national level had to translate into infrastructure and investment to help people realise their rights. The Committee's inquiry into human rights demonstrated that knowledge about rights is pointless if a person cannot realise them.

Some public bodies do not have enough awareness and understanding of human rights to put rights into practice. The Scottish Government’s intention to bring forward a Bill which sets out a framework for human rights in Scotland is welcome but there is a risk that public bodies will not be ready for the changes this would bring.

The Committee welcomes an update from the Scottish Government on the new human rights taskforce and asks for detail about how the taskforce intends to include the public sector and the third sector in its deliberations.

The Committee’s previous budget work shows the Scottish Government has been undertaking distributional analysis of income tax changes, providing analysis by income group, age and disability, and that the Scottish Government is looking into doing meaningful distributional analysis in Scotland. The Scottish Government also committed to explore cumulative distributional analysis during this year. The Committee welcomes the Scottish Government’s movement on distributional analysis and is keen to see progress being made on gender analysis, as it has featured in all its budget reports. The impact of the Scottish budget on gender equality needs to be known so it can inform the Scottish Government’s policies.

The Committee would welcome an update from the Scottish Government on its work on distributional analysis (including cumulative analysis) and whether this work has included any consideration of gender equality analysis.

Budgets and the National Performance Framework (NPF)

The Scottish Government has stated that the NPF is “a single framework to which all public services in Scotland are aligned.” As such, it—

Provides a strategic direction for policy-making in the public sector, and provides a clear direction to move towards outcomes-based policy making. It provides the platform for wider engagement with the Scottish Government’s delivery partners including local government, other public bodies, Third Sector and private sector organisations.

The NPF includes an explicit human rights “national outcome”, and four related “national indicators” and is linked to the UN Sustainability Goals. The human rights outcome all organisations should be working towards is—

We recognise and protect the intrinsic value of all people and are a society founded on fairness, dignity, equality and respect. We demonstrate our commitment to these principles through the way we behave with and treat each other, in the rights, freedoms and protections we provide, and in the democratic, institutional and legal frameworks through which we exercise power

Paul Bradley, SCVO, considered there to be a “lack of awareness and understanding about, and deployment of, the national performance framework”. On its effectiveness, he said “it looks nice—it has the right words in it and it has the right feel about it, but what does it mean in relation to commissioning, to services, to organisations and to local authorities. Although there is a recommendation for local authorities to ensure that they look at how local outcomes link to national outcomes, there is no duty to report on that”.

Richard Robinson, Audit Scotland, said this issue was “at the heart of the difficulties of aligning services towards outcomes”. He referred to Scotland’s Wellbeing—Delivering the National Outcomes, which accompanies the Medium Term Financial Strategy in May and sets out the baseline position. He advised the issue was how to marry the Local Outcomes Improvement Plans and the national plans together and how the different plans align.

Tim Kendrick, Fife Community Planning Partnership, spoke about how Fife Council had approached linking local outcomes with the national priorities of fairness and inclusion. He advised that instead of having an anti-poverty, financial inclusion and fairness plan alongside the overall council and community plan, they now had a single plan. The key was “not to look at fairness and equalities outcomes as an add-on but to integrate those into the whole monitoring and evaluation framework”. Bernadette Monaghan, Glasgow City Council, talked about her Council’s new performance management framework, which linked to the Council’s community plan. She stressed this would, however, include stories from communities and feedback, as well as information from community planning partners.

From the voluntary organisational perspective, Jude Turbyne, OSCR, acknowledged there was a question as to how charities operationalise what they were doing, and how that fitted within the national performance framework.

Glasgow Council for Voluntary Services stated that “equality and rights are part of the third sector’s DNA”; however, monitoring at local level did not always link to national outcomes or the national policy direction of travel. They called for the Scottish Government to explore how they could use their letters of allocation to public bodies to reference key messages on human rights and request public bodies to set-out “how they engage with the third sector as a defender of rights and as advocates.”

Conclusion

It is unclear to the Committee the extent to which the National Performance Framework is driving public spending decisions, especially at the local level. The Committee notes there is no formal requirement for local government to demonstrate how they are contributing to the Scotland’s National Outcomes.

While local authorities are autonomous bodies and should have freedom to operate independently as long as they fulfil their statutory duties, the Committee is interested in what mechanisms are open to the Scottish Government to encourage local authorities to engage more effectively with the third sector.

The Committee would welcome the Scottish Government’s views on the options available to it to strengthen the links between Scotland’s National Performance Framework and public bodies and how it can encourage local authorities to engage effectively with the third sector as human rights defenders and advocates for people accessing services.

Accountability

Public funding of advocacy organisations and possible conflicts

Submissions from the Scottish Independent Advocacy Alliance (SIAA), Glasgow Council for the Voluntary Sector (GCVS) and Women’s Aid Scotland (WAS) underlined the importance of advocacy organisations’ independence from the organisations they were there to challenge. WAS, for example, described the situation whereby third sector organisations were funded by the same public authorities that they – as “human rights defenders” - had to hold to account on behalf of the people they represented. According to WAS, this could create “particular challenges for smaller local services where there is a significant imbalance of power, funding is precarious and there is a lack of long-term contractual arrangements.”

At the national level, Paul Bradley commented SCVO’s relationship with the Scottish Government, “like many other national organisations, embodies the idea that a good positive relationship is about being a critical friend. Yes, we get funding from the Government, but we have a voice in relation to how we work collaboratively”. Likewise, Adam Stachura, Age Scotland, did not feel prevented from standing up for the interests of older people, saying “We are not just sitting in a silo; we help to channel the voices, views and needs of older people”. Engender explained that Scottish Government funding required them to work towards broad outcomes, but the grant making process did not direct or deflect their focus to or from particular policy areas, or require them to support any position that the Scottish Government may take. Engender advised that this is in contrast to their pan-UK advocacy work in consortium with other women’s organisations, they are prevented from lobbying UK Government and criticising its policymaking because the UK Government does impose conditions.”

At the Glasgow TSI event, however, some participants representing smaller organisations described an increasingly hostile environment which could leave them “in the cold” or had an implicit threat of funding changes or cuts when they challenged public bodies where action, or inaction, had threatened the basic rights of their service users.

GCVS reported hearing worries that some contracts between public services and the third sector may contain conditions requiring them not to challenge the services or authorities which fund them. They were therefore concerned “that the need to maintain positive relationships with funders may prevent charities from supporting legal action in cases where individual/family rights have clearly been breached”. Liz McEntee, GCVS, emphasised, “what has been described is happening, and we know that organisations feel that funding decisions … will be impacted if they speak out”.

Mhairi Snowden, Human Rights Consortium Scotland (HRC Scotland), explained work they had undertaken to inform a report on strategic litigation, and whether charities and non-governmental organisations should get involved in taking cases to court, which showed organisations were concerned about their funding being impacted. She said it was “entirely appropriate and correct that the public sector and local and national Government should fund civil society”, but that the Government should “repeat often and clearly that civil society has an absolutely appropriate role in being critical of Government”.

Perception of priority given to certain groups over others

Some organisations and individuals were concerned that the way public funding is allocated may act as a barrier to promoting the rights of the people they are trying to help. This issue was raised in several submissions, which argued that the Scottish Government, and other public bodies, prioritise gender self-identification over biological sex in policy-making. According to policy consultants MurrayBlackburnMackenzie (MBM) this was “reinforced by Scottish Government funding arrangements for third sector equalities organisations”. MBM were unaware of public funding in Scotland going to any organisation “that explicitly advocates for the interests and rights of women and girls on the basis of the protected characteristic of sex”.

Susan Smith, Forwomen.scot, referred to the application process for the Scottish Government’s equally safe fund, where according to a Freedom of Information request, applicants had to prove that they had a fully inclusive policy in place to meet the eligibility criteria—

To be eligible for funding, applicants are required to demonstrate the following in their application...Ensure that your service is inclusive to lesbian, bisexual, trans and intersex (LBTI) women. An LBTI Inclusion Plan should be submitted along with your application.

While no organisation has been turned down for Equally Safe funding on the basis of being single-sex, this is simply because any such application would be deemed ineligible in the first instance. The Equality Act provides for single-sex services which may also exclude those in possession of a GRC. By setting out the condition that applicants must have a policy which includes trans women, who are legally and biologically male, the criteria set by the Scottish Government for funding precludes applicants to this fund invoking the single-sex exceptions.

Furthermore, Forwomen.scot’s submission argued that prioritisation of groups promoting gender self-identification had taken place without any consultation with “a wider range of those who they claim to represent”. Others, such as Melissa Titus argued that—

There needs to be a mechanism for independent reviews across all the protected characteristics. It appears in many cases that funding and influence is given to one area with no consideration for how policies will impact on other vulnerable groups.

Christina McKelvie, Minister for Older People and Equalities (the Minister) rebutted the suggestion that the Scottish Government only funds third sector organisations on the basis that they share or promote certain policy positions or do not fund organisations that undertake work in relation to the protected characteristic of sex, the Minister stated “these suggestions are entirely wrong” and pointed to the evidence of SCVO.

On the suggestion that the Equally Safe (Violence Against Women and Girls) funding conditions required organisations providing services to women not to use the single-sex exemptions available through the Equality Act 2010 or that the Government made it impossible for them to do so, the Minister stated—