Criminal Justice Committee

Police (Ethics, Conduct and Scrutiny) (Scotland) Bill Stage 1 Report

INTRODUCTION

Proposals in the Bill

The Police (Ethics, Conduct and Scrutiny) (Scotland) Bill (“the Bill”) was introduced on 6 June 2023 by the Scottish Government.

The Criminal Justice Committee was designated as the lead committee on the Bill.

The Bill makes provision about the ethical standards of the Police Service of Scotland, procedures for dealing with and the consequences of certain conduct by constables, and how policing in Scotland is scrutinised.

It is an entirely amending Bill, which seeks to amend the following two Acts, and two associated Conduct Regulations—

Part one of the Bill provides references to these Acts.

The Bill has 20 sections, organised under four subject headings, which propose changes in the following areas—

ethics of the police

police conduct

functions of the Police Investigations and Review Commissioner (PIRC)

governance of the PIRC.

According to the Policy Memorandum published by the Scottish Government, the overarching policy objective of the Bill is to—

“…ensure that there are robust, clear and transparent mechanisms in place for investigating complaints, allegations of misconduct, or other issues of concern in relation to the conduct of police officers in Scotland. The legislation will embed good practice, and underline the importance of maintaining the high standards expected of Scotland’s police officers.”

Independent Review of Complaints Handling, Investigations and Misconduct in Relation to Policing

In 2018, the Scottish Government and the Lord Advocate jointly commissioned the Rt. Hon. Dame Elish Angiolini DBE QC, a former Lord Advocate, now Lady Angiolini, to carry out an independent Review of Complaints Handling, Investigations and Misconduct in Relation to Policing (“the Angiolini review”).

The Angiolini review’s remit was to—

consider the current law and practice in relation to complaints handling, investigations and misconduct issues, as set out in relevant primary and secondary legislation;

assess and report on the effectiveness of the current law and practice; and

make recommendations to the Cabinet Secretary for Justice and the Lord Advocate for improvements to ensure the system is fair, transparent, accountable and proportionate, in order to strengthen public confidence in policing in Scotland.

The review encompassed the investigation of criminal allegations against the police. It did not address the separate role of the Lord Advocate in investigating criminal complaints against the police or the role of His Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary in Scotland (HMICS) in scrutinising the state, effectiveness and efficiency of both the Police Service of Scotland (Police Scotland) and the Scottish Police Authority (SPA).

The Angiolini review published a Preliminary Report in June 2019,i which made 30 recommendations. A Final Report was published in November 2020,i which included a further 81 recommendations. The 111 recommendations in total included proposals for both legislative and non-legislative change.

On 5 February 2021, the Scottish Government and the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service (COPFS) published their joint response to the Angiolini review.i The response indicated an intention to “accept the majority of your recommendations”. With regards to the legislative changes, the response stated an intention “to take forward as many of these in a single Bill with associated secondary legislation”.

Between June 2021 and May 2023, five thematic reports were published by the Scottish Government. These provided updates on the actions taken to implement the non-legislative recommendations made by the Angiolini review.[4]iv

At the Scottish Police Authority Board meeting of 25 May 2023, the then Chief Constable of Police Scotland, Sir Iain Livingstone QPM, stated that “Police Scotland is institutionally racist and discriminatory”. In October 2023, Chief Constable Jo Farrell confirmed that she agreed with that statement, saying that “Police Scotland is institutionally discriminatory”. The Chief Constable indicated her intention to drive forward "an anti-discriminatory agenda”.

As part of its Stage 1 scrutiny of the Bill, the Committee heard evidence about the impact of the implementation of the non-legislative recommendations on the police complaints system.

Approach to scrutiny

Our role was to consider the merits of each of the proposals, in turn and on their own terms, with reference to the specific wording of the Bill. This principle has underpinned the approach to our scrutiny.

The voices of those with experience of the police complaints system

It was important for us to hear from people with personal experience of the police complaints system. From those who had made complaints, as well as those who had complaints made about them. We appreciated the opportunity to hear personal testimonies from those with direct experience of the police complaints system.

We are grateful to Stephanie Bonner, Bill Johnstone, Magdalene Robertson, Ian Clarke and Margaret Gribbon for taking the time to give their insightful evidence.

We are also grateful to have met, privately and informally, with one individual who provided evidence anonymously. In this report, we refer to him as Witness A.i

We issued a call for written views on the provisions in the Bill, between 26 September and 8 December 2023. The Committee received 45 written submissions.i

We wish to thank all those individuals and organisations who took the time to engage with us on the Bill and to provide their views. The evidence received has informed the Committee’s scrutiny of the Bill.

We would like to thank the Justice Committee clerks from the Northern Ireland Assembly for providing a comprehensive briefing on the reform to police complaints in Scotland and the experience and practice in a number of other jurisdictions internationally.

Finance and Public Administration Committee

The Finance and Public Administration Committee has a role in scrutinising the financial provisions in the Bill.

That Committee received 4 submissions in response to its call for views on the Bill’s Financial Memorandum.

The Finance and Public Administration Committee wrote to us, following its evidence sessions with the Scottish Government’s Bill team and the Cabinet Secretary for Justice and Home Affairs.

In the letter, the Convener of the Finance Committee highlighted that the cost estimates in the Financial Memorandum required to be revised from £1,414,474 to £5,800,069. This is to reflect the increase in estimated costs provided by Police Scotland to the Finance and Public Administration Committee. The letter indicated that—

“The updated overall total revised costs are estimated to be £5,800,069. Updated total one-off costs are estimated to be £2,356,134, compared to £801,134 in the original FM, and updated total recurring costs are estimated to be £3,443,935, compared to £613,340 in the FM”.

A significant increase in the estimated costs is to enable the Chief Constable to meet the statutory duty to ensure that all constables and police staff have read and understood the statutory Code of ethics. This cost and other resourcing issues are dealt with in the relevant sections in our own report.

In her letter to the Committee, the Cabinet Secretary for Justice and Home Affairs indicated that costs may increase further, saying that “at the point of revising the Financial Memorandum (FM) at stage 2 the Scottish Government will have regard to any pay settlements since the FM’s original publication and ensure any increased staffing costs are reflected”.

The Committee notes the position outlined above and the importance to committees of having up-to-date costs for this Bill. Whilst we welcome the letter provided to this Committee by the Scottish Government setting out revised costs, the Committee still wishes to see a revised Financial Memorandum provided at stage 2 or sooner. In any case, the Committee requests that it is kept updated if there are further significant changes in the expected costs of this Bill.

Delegated Powers and Law Reform Committee

The Scottish Government prepared a Delegated Powers Memorandum. It describes the purpose of each of the subordinate legislation provisions in the Bill and outlines the reasons for seeking the proposed powers.

This Committee received a report on the Bill from the Delegated Powers and Law Reform (DPLR) Committee on the delegated powers in the Bill.

The DPLR Committee stated it was content with the delegated powers in the Bill.

We refer to the recommendations of the DPLR Committee in the relevant sections of our report.

Policy Memorandum

Under Standing Orders Rule 9.6.1, the lead committee scrutinising a Government Bill is required to consider and report on its Policy Memorandum.

The Committee does not have any specific points to raise on the Policy Memorandum itself. The Committee does, however, comment on the policy objectives of the Bill throughout the report.

Overall views on the Police (Ethics, Conduct and Scrutiny) (Scotland) Bill

The Committee appreciates that the measures in this Bill seek to introduce robust mechanisms to address the unacceptable conduct and behaviours of a minority of police officers and staff. We recognise that the vast majority of police officers and staff are dedicated, honest and hard working, and do an incredibly difficult job.

The evidence that we have received on the Bill demonstrates the need for the police complaints system to improve, both for those who make complaints, as well as for those who find themselves the subject of a complaint.

Many of the personal experiences that we heard about pre-date the Angiolini review, and the work done by policing bodies and others within the criminal justice system to implement the review’s non-legislative recommendations, but not all.

We have found it difficult to reconcile the conflicting views we have heard about the police complaints and conduct systems and come to a definitive view on whether all the necessary improvements have been made, are in train, or whether there is much left to do. In particular, we are unsure whether the provisions in the Bill will sufficiently improve the experience of officers and members of the public.

We appreciate that this Bill cannot be viewed in isolation and is part of much wider work that has, and is, being done to improve the police complaints and conduct systems. However, our role is to scrutinise and come to a view on whether the provisions in the Bill meet the Scottish Government’s intention that “there are robust, clear and transparent mechanisms in place for investigating complaints, allegations of misconduct, or other issues of concern in relation to the conduct of police officers in Scotland”.

There are measures in the Bill which will improve the robustness, transparency and fairness of some of the processes. In particular, greater powers for various bodies, requirements on Police Scotland and the SPA to respond to PIRC’s recommendations and provide the Commissioner with direct access to relevant information, as well as the commencement or conclusion of gross misconduct proceedings, regardless of whether the person leaves the police service, and the introduction of Scottish advisory and barred lists.

However, the systems also need to be proportionate, efficient and effective. The evidence we received clearly indicates that the Bill, as introduced, will have little impact on the length of time taken to consider and conclude police complaints. This is a key issue for all those who are involved in the police complaints system, which remains largely unresolved.

Questions also remain about the robustness of the oversight mechanisms in place within policing and whether the culture within policing has changed. We heard evidence of unacceptable behaviours and practices within Police Scotland, which had devastating impacts on those involved. It is unclear how those behaviours and practices were not identified and addressed by the SPA in its oversight role. This does not provide us with the necessary reassurance that those who make complaints, or who are the subject of complaints, will not have the same experience today.

PARTS 2 AND 3: ETHICS OF THE POLICE

Proposals in the Bill

All of the provisions under this heading concern the ethics of the police and seek to amend the Police and Fire Reform (Scotland) Act 2012, (“2012 Act”) and associated conduct regulations.

Police Scotland currently has a non-statutory Code of ethics which sets out the standards of those who contribute to policing in Scotland. The Code of ethics for Policing in Scotland sits alongside the standards of professional behaviour, which are set out in schedule 1 of the conduct regulations for officers and senior officers. The standards of professional behaviour outline the expectations of police officers, whether on or off duty.

The Bill creates a duty on the Chief Constable of Police Scotland, with the assistance of the SPA, to prepare and review periodically a statutory Code of ethics. The Chief Constable will have a duty to consult upon the Code, publish it, and take all necessary steps to ensure that every constable and member of police staff have read and understood the Code. Constables are to make the following commitment to follow the Code in the constable’s declaration—

“… that I will follow the Code of ethics for Policing in Scotland”.

The Bill introduces an individual duty of candour on constables by amending the conduct regulations for all officers to add the following duty of candour into the standards of professional behaviour—

“Constables act with candour and are open and truthful in their dealings, without favour to their own interests or the interests of the Police Service.

Constables attend interviews and assist and participate in proceedings (including investigations against constables) openly, promptly and professionally, in line with the expectations of a police constable”.

It also introduces an organisational duty of candour by adding the following policing principle to the 2012 Act “that the Police Service should be candid and co-operative in proceedings, including investigations against constables”.

The Bill also amends section 10 of the 2012 Act to include “candour” after “fairness” in the following constable’s declaration—

“I, do solemnly, sincerely and truly declare and affirm that I will faithfully discharge the duties of the office of constable with fairness, integrity, diligence and impartiality, and that I will uphold fundamental human rights and accord equal respect to all people, according to law”.

The Policy Memorandum explains that these provisions “makes clear on a legislative basis the need for police officers to be open and transparent”.

Code of ethics

Section 2 of the Bill seeks to put Police Scotland’s existing Code of ethics (“the Code”) on a statutory footing. It confers a duty on the Chief Constable of Police Scotland, with the assistance of the SPA, to prepare the Code of ethics.

In doing so, the Chief Constable, also has a duty to consult and share a draft of the Code with persons specified in the Bill, publish it, take all steps necessary to ensure that all constables and police staff have read and understood the Code, and make provisions for reviewing it once every five years.

Impact

The Committee considered how the introduction of a statutory Code of ethics might impact on the behaviour of police officers and staff, and how it might improve public confidence in policing.

In the written and oral evidence received by the Committee most people agreed with the introduction of a statutory Code of ethics. A minority view was that Police Scotland’s non-statutory Code of ethics, as well as the conduct regulations, were sufficient. Some people expressed reservations about whether a statutory Code of ethics would have much, if any, impact on improving the police complaints system.

In her evidence to the Committee, the Rt. Hon. Lady Elish Angiolini KC, said that she was “particularly pleased about the inclusion of the Code of ethics and the duty of candour, as it is important that “right from the beginning of the process, the police service recruits the right people for the right reasons”. Lady Elish explained that “more than anything, the culture in policing is what keeps the police off the disciplinary aspect or produces a cynical, difficult environment for police officers”.i

A statutory code is supported by the SPA and Police Scotland. Police Scotland indicated in its written evidence that it will provide “greater legal weight and, in practical terms, greater prominence in the minds of serving officers and staff”. The SPA confirmed in an email to the Committee that it “does not have its own Code of Ethics applicable to its own staff”. In response to a question about whether the current non-statutory Code of ethics applies to any SPA staff, the Authority stated that “Although the code isn’t explicit as to who it covers, the Code of Ethics was developed by Police Scotland, against its own values”.ii

Craig Naylor, HMICS, told the Committee that a statutory code will set out what is expected of police officers and staff, so that “there is no dubiety”. The Chief Inspector added that—

“The issue for me is how that is used in the conduct process at some point in the future. Whether that becomes regulation or whether it becomes practice within Police Scotland”.iii

Chief Superintendent Rob Hay told the Committee that a statutory code “would be well supported” by the Association of Scottish Police Superintendents’ (ASPS) membership, as it is an opportunity to improve Police Scotland’s internal culture. He added that, there is also a requirement for the provision of equality, diversity and inclusion training and refresher training to all officers. Chief Superintendent Hay said that—

“The service has had to react to some of the cases that I know the committee will have heard about … There is a greater level of examination of how we can change the culture of the organisation and move on by, for example, making that Code of ethics come to life within the organisation and highlighting the standards of professional behaviour”.iv

Stephanie Griffin from the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) recommended that training be provided “to make officers aware of their obligations in relation to equalities and human rights”, and that the training is reviewed regularly. Ms Griffin said that this is to ensure that police officers have—

“… knowledge of the current law around protected characteristics and what is and is not acceptable, the risk of ignoring or seeming to approve inappropriate behaviour and personal liability”.v

In its written response to the Finance and Public Administration Committee’s call for views on the Financial Memorandum, Police Scotland indicated that “A robust regime of ‘training’ is essential” for the Chief Constable to demonstrate statutory compliance with ensuring that all constables and police staff have read and understood the Code, and that a record is made and kept by the Chief Constable of the steps taken in relation to each constable and member of staff”.

Former police officer, Ian Clarke, told the Committee that the Bill should also codify exactly how an investigation is conducted, to ensure that police officers can have confidence that investigations are fair, thorough and less able to be influenced by the opinion of the investigating officer. Mr Clarke explained that this might avoid the experience that he had, when he was the subject of a complaint, saying that—

“My experience of the investigation into the allegation against me was that reasonable lines of inquiry were not followed, exculpatory evidence was not disclosed, my case was not subject to any review, and the code [of practice, under section 164 of the Criminal Justice and Licensing (Scotland) Act 2010] had been breached on multiple occasions. My complaints to Police Scotland, COPFS and PIRC were all about that but, with the code being voluntary, it was easy to excuse those breaches”.vi

In its written evidence to the Committee, the Scottish Police Federation (SPF), stated that officers are held accountable by the standard of professional behaviour in the conduct regulations and that the “formalisation of a Code of ethics will have no noticeable effect as 99.9% of all officers have already been abiding to these standards”.

David Malcolm told the Committee that Unison Police Staff Scotland Branch (“Unison”), was not initially consulted by the Scottish Government on police staff being included in the Code of ethics provisions, as that was not the original intention of the legislation. Mr Malcolm said that this provision, and any extension of the duty of candour to police staff will require Unison to take legal advice, as “The situation could lead to changes to contracts. Does that proposal infringe on employment rights?”. Mr Malcolm added that there may also be costs associated should police staff become a regulated workforce, saying “we would expect remuneration in comparison with other public sectors for that”.vii

Compliance and accountability

The Explanatory Notes that accompany the Bill confirm that there will not be any sanctions for officers or staff for not following the Code, it states that—

“The Code will not have any particular legal effect. A failure to comply with the Code will not of itself give rise to grounds for any legal action. Neither will a breach necessarily constitute misconduct, which will continue to be measured by the standards of professional behaviour alone”.

The Committee heard differing views on whether a statutory Code is necessary and, if so, whether it should be a disciplinary code with sanctions for breaches or a set of values for Police Scotland’s officers and staff to aspire to.

Dr Genevieve Lennon, Scottish Institute of Policing Research (SIPR) told the Committee that whilst a statutory code “is symbolically important”, it would be strengthened by being a discipline code, which would require some reworking of the current code. Dr Lennon said that “Without making it a disciplinary code, I am not sure how much difference it will make day to day”.i

Dr Lennon added that it is important that data is gathered on whether the code is being adhered to, and that this role should be done by the SPA, saying that—

“… the policing board should be responsible for gathering and disseminating a review of adherence to the Code of ethics, whether in terms of breaches or whatever else. That is comparable to the approach that is taken, for example, in Northern Ireland, where the Northern Ireland Policing Board is responsible for monitoring adherence to the Code of ethics”.ii

Mr Bill Johnstone told the Committee there should be a sanction for breaching the Code of ethics, however, this would depend on breaches being reported. Mr Johnstone said “Absolutely, but the problem is how you decide when they have breached the Code of ethics when nobody will co-operate”.iii

Magdalene Robertson told the Committee that there is no reason to create another code, saying that consideration should be given to “what would happen if there were a breach of the Code of ethics that the police are already sworn to”. Ms Robertson said—

“I cannot express how much I disagree with doing that. There should definitely be clear information on what the minimum is that it [Police Scotland] would suffer if it committed an offence … or does not uphold its duties”.iv

Kate Wallace said that people who are supported by Victim Support Scotland expect the Code to be “transparent and publicly available” and that it “will hold people to account” when not adhered to. Ms Wallace added that training alone would not be sufficient to ensure compliance, and highlighted the following three things that need to be in place—

“The first is about using it as a positive tool to promote improvements in the way that people behave and things are done. The other is to ensure that, when there are breaches, they are monitored, addressed and dealt with properly in every instance. Another aspect is public awareness of the code”.v

In its written evidence to the Committee, the Coalition for Racial Equalities and Rights (CRER), recommended a requirement for officers and staff to have to comply with the Code, saying that—

“The Code of ethics should be given the same statutory status as the current standards of professional behaviour, in that failure to respond may result in a finding of misconduct. This could potentially be remedied by adding compliance with the Code of ethics to the standards of professional behaviour on a statutory basis. Compliance with the Code of ethics should be reported publicly on an annual basis”.

Witness A made a similar point in evidence to the Committee about the importance of accountability, as well as transparency—

“The Code of ethics is a good idea, as everyone will know how to proceed in good faith. Police officers who are guilty of misconduct should be disciplined. It should be a transparent process, with the findings of misconduct proceedings published”.

Robin Johnston of the SPA, said that the purpose of the Code is to reflect the expected standards and values of officers and staff, and it is the conduct regulations which contain the professional standards that officers must adhere to. Mr Johnston thought this was the correct approach, saying—

“To some extent, then, the Code of ethics is trying to achieve a different thing from the discipline code. Essentially, it is a guide that, if followed, will mean that officers can avoid ever having to enter the misconduct regime … If properly implemented, the code can be used successfully to avoid anyone ever entering the conduct regime.”vi

Responsibility for the Code of ethics

The Policy Memorandum states that, as the Code “relates to mostly operational matters, the Chief Constable will bear ultimate responsibility for it”.

The Angiolini review recommended that the Chief Constable and the SPA should have joint responsibility to prepare, consult on, publish and revise the Code—

“Police Scotland’s Code of ethics should be given a basis in statute. The Scottish Police Authority and the Chief Constable should have a duty jointly to prepare, consult widely on, and publish the Code of ethics, and have a power to revise the Code when necessary”.i

In its written evidence to the Committee, Amnesty International UK agreed with Lady Angiolini’s recommendation that the SPA and the Chief Constable should have joint responsibility. Their view is that this approach will “offer greater public reassurance of independence and accountability”. It will also bring Police Scotland’s Code into line with the Council of Europe Code of Police Ethics.

In its written evidence to the Committee, EHRC recommended that “The Bill should reflect the need to consider the public sector equality duty (PSED) in preparing a Code of ethics”. Stephanie Griffin told the Committee that the provision for consulting, reviewing and collecting data is “a huge part of meeting the requirements of the Scottish specific duties” of the Equality Act 2010.ii

Consultation

The Bill inserts section 36B into the 2012 Act. It contains a list those who the Chief Constable should consult and share a draft of the Code with. This is set out in schedule 2ZA.

In its written evidence to the Committee, Amnesty International UK highlighted that the proposed statutory list of consultees does “not include any person or organisation external to policing bodies or the Scottish Government”. They recommend that it “should include the Scottish Human Rights Commission and relevant civil society organisations, including those representing the interests of people with lived experience of police interventions, including those with negative experiences of policing as identified in Dame Angiolini’s report”.

Dr Genevieve Lennon told the Committee that the Scottish Human Rights Commission and possibly the Equality and Human Rights Commission should be added as persons to be consulted in respect to the Code.i

There is already a non-statutory Code of ethics for police officers and staff. The Committee welcomes the provisions in the Bill to introduce a statutory Code of ethics for officers and staff.

The new Code of ethics needs to be robust and reflect the challenges of modern policing. The Bill does not include details of what is to be included in the new Code and we therefore recommend that the Criminal Justice Committee is able to review the draft Code. The Committee asks the Scottish Government to clarify how the Code of ethics and duty of candour will impact on police staff.

The Committee asks the Scottish Government to confirm whether the intention is that the statutory Code of ethics will apply to any SPA staff. For example, those who work in forensic services.

The Committee agrees that the Chief Constable should have responsibility to prepare, consult widely on, publish and revise the Code, with the assistance of the SPA.

Duty of candour

It also places a duty on the SPA to promote the principle that the Police Service should be candid and co-operative in proceedings.

The Policy Memorandum describes the intention of these provisions, as follows:

“By embodying the duty of candour in a separate standard, it emphasises that the requirement to assist in investigations is not only the same as following any other duty or order, but is of a different, more serious and more fundamental nature”.

Impact

The Committee sought views on the impact of introducing a duty for individual police officers to be candid and co-operative, as well as an organisational duty for Police Scotland to be candid and co-operative in proceedings, including investigations against constables.

Margaret Gribbon told the Committee that she did not think that a statutory duty of candour or Code of ethics “will make a massive amount of difference in practice”. Ms Gribbon explained that—

“My understanding is that the oath given by all police officers should be inherent in what they do day to day. If that is codified, I do not suppose that it will do any harm, but in the context of police complaints handling, I do not think that a duty of candour or a Code of ethics on their own will be enough, I am afraid”.i

Stephanie Bonner told the Committee that she did not believe that a statutory duty of candour, without any consequences for those who choose not to co-operate, will bring about the required changes to the behaviour of police officers. Mrs Bonner said that—

“You are asking police officers who stand shoulder to shoulder with each other and may literally protect each other’s backs in dangerous situations to be truthful and co-operative, which could lead to their colleagues being disciplined and punished. They protect each other every working day, so they are most likely going to protect each other in these types of situations. Perhaps giving evidence under oath, with a perjury-type system in place, might make officers more willing to co-operate. There have to be consequences in place if officers do not co-operate or are proven to be untruthful.ii

Bill Johnstone agreed, telling the Committee that the only way the public will get complete candour from police officers “is if they are under oath and if, before that, they are presented with evidence to show that, if they go in there and just spin a story for their pals, they are gonnae go to jail”.iii

Witness A held a similar view, saying that the duty of candour needs to be broad enough to be enforceable, there should be clarity about what it means, and consequences for not adhering to it.

Magdalene Robertson highlighted that police officers are already required to be honest, telling the Committee that—

“Why do we need another set of rules? If I were in the police or the PIRC and someone said, “Would you like to create another set of duties?”, I would say, “Yes, I will take that on and I will write as many lists as you want.” It does not matter; it makes no difference. Just scrap it and stick with the duty that we already have”.iv

Ian Clarke recommended that the duty of candour, as well as the Code of ethics, should apply more widely, and that there should be sanctions for failure to comply. Mr Clarke said—

“The code and duty should not apply only to police officers who are under investigation; they should also apply to COPFS and the PIRC—the people doing the investigations. There is widespread mistrust within the police of the present misconduct system and of the behaviour of the PSD, the PIRC and CAAPD”.v

Kate Wallace told the Committee that Victim Support Scotland’s experience is that “officers are not forthcoming” if they have made a mistake, which “can lead to bigger problems”. Ms Wallace said, therefore, that a statutory duty of candour could “make a big difference”.vi

Dr Genevieve Lennon from SIPR said that the duty of candour should “be expanded to apply to retired officers and their conduct as officers”. Kate Wallace confirmed that Victim Support Scotland shared that view.vii

In her written evidence, Professor Denise Martin stated that while the duty of candour is a starting point “it will not be successful unless other broader organisational culture shifts to allow staff to feel secure in being open and honest”, are in place. Professor Martin said that Police Scotland needs to “shift towards a more open and transparent organisation”, to enable staff to feel “safe to speak out and being open, without being ostracised by other peers and colleagues”.

The Committee heard evidence that a culture exists within Police Scotland, where police officers do not feel supported to admit they have made a mistake or to call out inappropriate behaviour.

Stephanie Bonner told the Committee that Police Scotland did not admit at the start that they had made errors during the investigation into her son’s disappearance and unexplained death, and did not apologise, saying that—

“They could have been open and said, “We did this wrong at the very start. We’re so sorry, but we’re going to rectify this right now, at the very start and find things out”; I believe that they knew from the start that it was wrong”. viii

Magdalene Robertson said that enabling police officers to be able to admit a mistake and apologise is essential, saying that, “You have to allow the police to apologise at the offset, too. That might solve a lot of issues without having to go into full, big, complaints that go on and on”.ix

Witness A told the Committee that there is a refusal to admit when an officer has done something wrong. He added that “There are good people within Police Scotland who should be able to make recommendations to improve the service”.

Margaret Gribbon said that, in her experience of representing former police officers, she has observed that “The difficulty is the culture and the psyche. It seems to be an instinctive defence mechanism”.x

Nicky Page explained to the Committee that Police Scotland’s Policing Together programme aims “to create an environment where people can come forward and learn”. Ms Page said that changing the culture and providing wraparound support to officers has been the focus over the last three years, stating that—

“A lot of the work that we are doing in policing together is to create an environment where people can notice things as they are going wrong and come forward before the situation escalates or behaviours escalate, because we then have a better opportunity to step in and assist people before things get worse”.xi

Deputy Chief Constable Speirs acknowledged that Police Scotland must change its culture and be a more open and transparent organisation. DCC Speirs explained that the Policing Together programme aims to prevent misconduct occurring, by providing leadership, equality, diversity and inclusion training. DCC Speirs added that—

“We recognise that we have a lot of work to do, and some of the lived experiences that the committee has heard about will have reflected that … Through the committees at the SPA, we will clearly be held to account. We have a range of performance measures against which we will try to assess whether we are making progress in that direction”. xii

HM Chief Inspector of Constabulary, Craig Naylor told the Committee that giving officers and staff a Code of ethics to rely upon and a duty of candour will mean that “when things are really difficult, they will know what they are entitled to do and what they are expected to do”. Mr Naylor added that HMICS is satisfied that the duty of candour provides clarity to officers, as well as the necessary protections. The Chief Inspector said that—

“… where it is clear that an individual is a witness in a criminal matter, there should be a duty of candour that means that they should provide a statement as soon as is reasonably practical to the Police Investigation and Review Commissioner, or whoever is doing the investigation ... we also see the need to have protections of people who are under criminal investigation as either suspects or accused persons … The legislation covers that well”.xiii

Deputy Chief Constable Speirs highlighted that police officers do an incredibly difficult job and can be asked to provide information on really difficult circumstances. DCC Speirs said that in his experience “officers and staff, when required, co-operate fully”. He added that a statutory duty of candour will be helpful for “public inquiries, fatal accident inquiries and more interaction with the PIRC”. xiv

The Cabinet Secretary for Justice and Home Affairs told the Committee that she is beginning to see culture change within Police Scotland. This is in part through the acceptance and implementation of the Angiolini review’s non-legislative recommendations, as well as the oversight work of the Ministerial Group. The Cabinet Secretary said—

“That is in part because of the work that Police Scotland does on diversity and inclusion and because of how the organisation is moving forward to actively tackle racism and misogyny. Monitoring, accountability and auditing processes have improved in the PIRC, Police Scotland and the Scottish Police Federation”.xv

The Cabinet Secretary explained that the duty of candour is being introduced for police officers as “Those who hold the office of constable and the powers of that office have a higher duty than others to account for their actions and record what they did or saw in the execution of their duties”.xvi

The Cabinet Secretary added that a statutory duty will make the expectations “clear around that culture of co-operation … Raising the significance of that by locating it in legislation would allow case law in and around this area to grow”.xvii

The Committee considered whether the duty of candour should apply to police officers who are off-duty, and whether it should be extended to police staff.

Applicable to off-duty officers

Robin Johnston explained that the Policy Memorandum records that most respondents to the Scottish Government’s consultation on the Bill were in favour of the duty applying to off-duty officers. However, as the Bill does not contain any explicit provision addressing this issue, the SPA is seeking clarity, “so that there is no dubiety about it in practice".i

Deputy Chief Constable Speirs said that Police Scotland’s view is that “Care needs to be taken in considering whether the duty of candour extends to circumstances that happen off duty”.ii

The Cabinet Secretary confirmed to the Committee that the duty of candour “does apply to off-duty officers”.iii

Applicable to police staff

The Policy Memorandum provides the following explanation for the Bill not including an individual duty of candour for police staff, stating that—

“… those staff are not afforded the same powers and responsibilities as officers, and so it could be argued that they should not be subject to the same degree of scrutiny. However, in applying an organisational duty of candour through the Policing Principles, police staff can be covered under this wider umbrella”.

David Malcolm, Unison, told the Committee that as police staff “are contractual employees of the Scottish Police Authority”, any proposal to extend the duty of candour to them would require an amendment to their contracts and “remuneration in comparison with other public sectors”. Mr Malcolm confirmed that Police Scotland’s staff do not wish the duty to extend to them, and have expressed concerns that they do not have the right to silence in conduct proceedings. Mr Malcom said—

“Our members tell us that they are being treated like police officers, but they are not police officers. They do not swear an oath of office. Why should they be considered in the same way?”.i

In its written evidence, PIRC recommended extending an individual duty of candour to police custody and security officers, as they have direct responsibility for persons in custody, stating that—

“… consideration should be given to extending any specific statutory duty of candour to those members of police staff who undertake operational roles and have statutory powers and duties such as Police Custody and Security Officers [‘PCSOs’]. While PCSOs are staff and, therefore, not subject to the various conduct regulations, Section 28(5) of the 2012 Act does make them subject to certain duties in the same way as police officers (criminal of neglect of duty)”.

The Commissioner, Ms Macleod, told the Committee that she does not share the Scottish Government’s view that police staff “do not have the same powers and responsibilities as police officers”.ii

Robin Johnston confirmed that the SPA agrees with PIRC that the duty of candour should apply to police custody and security officers, as “police staff in those capacities are much more likely to be witnesses to the kinds of incident that the PIRC is investigating”, and this “might impact on the effectiveness of investigations in the future”.iii

Nicky Page said that whilst Police Scotland’s front-line staff are more likely to be involved in investigations, to ensure public trust and confidence, it is her view that the duty of candour should apply to all police staff. Ms Page said that—

“My position is that that should be a duty on all who work in policing, and it should be for the PIRC and others to say, “It is you who can assist.”iv

HM Chief Inspector of Constabulary, Craig Naylor, said that his personal view is that the duty of candour should apply to all staff, and that it should not be linked to additional pay. Mr Naylor told the Committee that—

“My personal view is that that should apply to everyone: every member of staff and police officer in Scotland should have that duty of candour, with the appropriate protections around criminal matters …To ask for more money to have a duty of candour rubs the wrong way for me, as a public servant”.v

Kate Wallace told the Committee that Victim Support Scotland would like to see the duty of candour extended to police staff.vi

The Cabinet Secretary highlighted to the Committee that police staff are employed on a different basis to police constables, who “are office-holders who have very particular rights and responsibilities and they are in a heightened position of trust”. The Cabinet Secretary confirmed that there is in place “an ethics and values framework that applies to police staff”.vii

The Cabinet Secretary added that “Where there is an organisational duty, it applies to everybody collectively”.viii

Caroline Kubala, Scottish Government, stated that police staff have a “code of conduct, which is part of their terms and conditions of employment”, which sits outside legislation. Ms Kubala clarified that—

“It is possible that some duties with regard to conduct could be added by the SPA through the terms and conditions of staff, but that would have to be discussed further and it would have to decide whether it thought that that was appropriate, fair and proportionate”.ix

In correspondence to the Committee following the evidence session, the Cabinet Secretary for Justice and Home Affairs clarified that “The SPA and Chief Constable should carry out their own consideration as to whether candour should be reflected in the staff code”.

Duty of co-operation

The Committee heard conflicting evidence about whether the Bill should be amended to introduce a duty of co-operation for police officers.

The Angiolini review concluded that the co-operation of police officers should be put beyond doubt in primary legislation, recommending that—

“The Scottish Government should consult on a statutory duty of co-operation to be included in both sets, or any future combined set, of conduct regulations as follows: “Constables have a duty to assist during investigations, inquiries and formal proceedings, participating openly, promptly and professionally in line with the expectations of a police officer when identified as a witness”.i

The Policy Memorandum, which accompanies the Bill, provides the following explanation for the Scottish Government’s decision not to include a duty of co-operation in the Bill—

“The Scottish Government when analysing the recommendations concluded that, while the Bill would set out what was required by way of co-operation, it is a facet of the duty of candour and not a freestanding duty”.

In its written evidence to the Committee, HMICS stated that the organisational duty of candour puts beyond doubt that police officers and staff will co-operate with investigations, saying that—

“HMICS concurs with Lady Elish Angiolini's contention that whilst there is currently an assumption of co-operation, that this requires to be put beyond doubt. This element of the Bill is further strengthened by the inclusion of an organisational duty of candour”.

In PIRC’s written evidence, the Commissioner takes the opposite view, saying that “In PIRC's view, the duty of candour does not satisfy the requirement for a duty of cooperation”. The Commissioner stated that a duty of co-operation should be introduced for police officers and staff with witness status, saying that—

“A legislative duty of co-operation for police officers - and police staff - would compel police officers to provide operational statements and attend within a reasonable timescale for interview. Taking into account the right not to self-incriminate, the duty should apply only to officers and staff whose status has already been confirmed as that of a witness”.

Michelle Macleod, Police Investigations and Review Commissioner (“the Commissioner”), explained to the Committee that the duty to co-operate in interviews and investigations into constables and police staff should be statutory, as there is not a remedy in the circumstances where a police officer or member of staff who has been confirmed as a witness, refuses to provide a statement. The Commissioner said that—

“The issue is that, although it is a policing principle and there is therefore an obligation on officers to provide a statement, we do not know what the sanction would be if an officer chose not to do so in certain circumstances”.ii

In the circumstances that an officer’s status changed during the investigation from a witness to a suspect, Ms Macleod confirmed that this is kept under review, and that should court proceedings commence “issues of admissibility and fairness are taken into account, because of the rights of the officer or members of the public under article 6 of the European convention on human rights”.iii

Lady Elish Angiolini told the Committee that she recommended a statutory duty of co-operation to “ensure that such evidence is preserved and is the evidence of each individual— not what might impliedly be the groupthink”. Lady Angiolini questioned what would happen if an officer did not co-operate and provide a statement, saying that “would have to be dealt with by the chief constable”.iv

Justin Farrell from the Criminal Allegations Against the Police Division in the Crown Office (CAAPD), told the Committee that he would be in favour of a duty of co-operation if there was a way to make it compliant with the European Convention on Human Rights Article 6, the right to a fair trial. Mr Farrell explained that this would be difficult to achieve, as—

“Once you get into compelling someone to attend for an interview and attach potentially punitive consequences for not doing so, you could get into difficulties, if they incriminate themselves, in using that product in any event”.v

Chief Superintendent Rob Hay indicated that the view of the ASPS members is that a statutory duty of candour “will largely achieve” the intention of police officer co-operation. He added that a concern is how the duty would impact on an officer’s right to a fair trial and their right “not to self-incriminate in criminal inquiries”. Chief Superintendent Hay questioned the fairness of introducing a process where an officer who chose “to exercise their right to silence”, is then “sanctioned for failing to adhere to a duty of candour”.vi

David Kennedy told the Committee that the SPF does not believe that a duty of candour is necessary for police officers, as they provide a statement “99.9 per cent of the time”. Mr Kennedy explained that an officer will make that decision based on their status—

“An officer has to understand whether they are a suspect, an accused or a witness. Once they know their status, they will provide the necessary statement. When that status is clarified, that is exactly what happens”.vii

Robin Johnston, SPA, suggested that the legislation could adopt the same approach to the standards of professional behaviour in England and Wales, by making it clear that “the duty of candour applies only to police witnesses, rather than to anyone who has been suspected of a crime or misconduct”.viii

Robin Johnston told the Committee that the SPA’s view is that “the bill probably does not go far enough in providing a proper remedy in the very small number of cases, if any, where police officers do not adhere to that duty of candour”. Mr Johnston added that there “are ways and means” of including in the Bill a power to compel police officers to attend interview and to provide information to PIRC once identified as a witness, as there are similar powers in place in England, Wales and the Republic of Ireland.ix

In its written evidence, Police Scotland noted that the provision in place in England and Wales “only imposes the duty of candour (and co-operation) when the officer has been identified as a witness and not when identified as a suspect”. Police Scotland indicates that “This is to reflect that a police officer enjoys the right against self-incrimination, both in conduct and criminal proceedings”, and state that further consideration is required on “the extent to which the said proposed new Duty can be properly reconciled with officers’ existing legal entitlements – of which the right against self-incrimination is clearly one carrying strong protection”.

The standards of professional behaviour in The Police (Conduct) Regulations 2020 for police officers in England and Wales includes the following responsibility—

“Police officers have a responsibility to give appropriate cooperation during investigations, inquiries and formal proceedings, participating openly and professionally in line with the expectations of a police officer when identified as a witness”.

The Policy Memorandum states that the duty of candour does not infringe on the right to silence or privilege against self-incrimination, explaining that—

“As is clear from the way in which the duty is expressed and implemented, it is subject to the specific protections of the general law, which includes the right to silence and the privilege against self-incrimination”.

The Committee supports the aims and objectives of the introduction of the provisions in the ethics of policing sections of the Bill. In particular, to improve the culture within policing and public confidence in its ability to deal effectively with police complaints. However, the Committee considers that their impact could be largely symbolic and is unable to assess what tangible impact they will have.

The introduction of an individual duty of candour for police officers, as well as the organisational duty of candour are important mechanisms for demonstrating the values and culture of Police Scotland to its officers and staff, and to members of the public. The Committee notes that these changes are part of wider measures that have been introduced to change the culture within policing.

The Committee welcomes the inclusion of the individual duty of candour for police officers in the conduct regulations, as this means that disciplinary proceedings can be implemented against those officers who do not comply with the duty.

The Committee notes the evidence received that the proposed statutory duty of candour will not necessarily ensure that police officers and staff who are identified as witnesses will provide full statements to PIRC.

The Committee appreciates that the overwhelming majority of police officers already adhere to the principles set out in the proposed duty of candour. For the small minority of officers who do not, Police Scotland should pursue the relevant disciplinary proceedings when it is demonstrated that officers are not adhering to the new duty.

The Committee asks the Scottish Government to clarify the reasons for not introducing a duty of co-operation in the Bill and to respond to the Angiolini review recommendation and PIRC’s evidence to the Committee supporting the introduction of a duty of co-operation.

The Committee is content that the introduction of an individual duty of candour for police officers and an organisational duty of candour, does not affect the right to silence and the privilege against self-incrimination of anyone working for Police Scotland who is suspected of a crime.

The Committee asks the Scottish Government to clarify whether the individual duty of candour will only apply to police officers, and that the organisational duty of candour will only apply to police staff, who have witness status, rather than to anyone working for Police Scotland who is suspected of a crime or misconduct.

The Committee recommends that the individual duty of candour should also apply to police staff who undertake operational roles which provide them with statutory powers and duties, such as police custody and security officers.

The Committee asks the Scottish Government to consider whether SPA staff who undertake relevant policing roles, such as those who work in forensic services, should also be covered by the duty of candour.

The Bill introduces an individual duty of candour on constables by adding the duty to the standards of professional behaviour within the conduct regulations for all officers. The standards of professional behaviour apply to officers whether they are on or off duty. The Committee asks Police Scotland to clarify its reasons for asking that care be taken when extending the duty of candour to circumstances that happen off duty.

Financial costs - sections 2 and 3

The Financial Memorandum, that accompanied the Bill, estimated that the costs for Police Scotland to implement the ethics of the police provisions “are likely to be below £10,000” and therefore could be “absorbed” by Police Scotland.

In its written response to the Finance and Public Administration Committee’s call for views on the Financial Memorandum, Police Scotland stated that the costs attributed to Police Scotland are “significantly underestimated”.

This is in large part due to the statutory responsibility on the Chief Constable to ‘secure that all such steps are taken as the Chief Constable considers necessary to ensure that all constables and police staff have read and understood it (the Code of ethics); and that a record is made and kept by the Chief Constable of the steps taken in relation to each constable and member of staff’.

Police Scotland confirmed in its submission that this will require funding of a “robust regime of training”, to ensure officers and staff understand the police ethics provisions, as currently there is no mandatory training covering the standards of professional behaviour.

Police Scotland estimated that there will be one-off costs of £1,517,000, and £758,500 recurring costs, for training. There is also a recurring cost of £35,000 to maintain training of support specialists. In her evidence to the Finance and Public Administration Committee, the Cabinet Secretary confirmed that she accepted these revised costs as accurate.

In response to a question about why the Scottish Government did not publish a revised Financial Memorandum at the time of Police Scotland providing the revised costs, the Cabinet Secretary explained to the Committee that—

“I do not just accept what people tell me something is going to cost; I expect my officials to robustly examine it. In March of this year, we got to the point at which the Government accepted the revised costs. The financial memorandum was the best estimate based on the information that I and my officials had at the time”.i

PARTS 4 TO 8: POLICE CONDUCT

Proposals in the Bill

All of the provisions under this heading are concerned with procedures for dealing with, and the consequences of, certain conduct on behalf of police constables. They amend the 2012 Act.

Section 4 addresses a perceived gap in existing legislation by clarifying that liability for any unlawful conduct on the part of the Chief Constable sits with the SPA.

Section 5 gives PIRC a greater role in relation to misconduct proceedings for senior officers. The Bill widens the functions that can be conferred on PIRC in secondary legislation, such as the statutory preliminary assessment function, consideration of whether the allegation is vexatious or malicious, a statutory function to present cases at a senior officer misconduct hearing and the power to recommend suspension of a senior officer.

Section 6 enables gross misconduct proceedings to continue or commence in respect of persons who have ceased to be constables. The procedures are to apply where a preliminary assessment of the misconduct allegation finds that the conduct of the person while they were a constable would, if proved, amount to gross misconduct. The Policy Memorandum, which accompanies the Bill, indicates that PIRC is to carry out the preliminary assessment. The Bill also includes a power to state a period of time from the date of an officer resigning or retiring, after which no steps or only certain steps in the procedures can be applied unless additional criteria are met. The Policy Memorandum indicates that the criteria will include a proportionality test carried out by PIRC. The details are to be set out in secondary legislation.

Section 7 enables the SPA to establish and maintain a Scottish police advisory list and Scottish police barred list and sets out the criteria for entering a police officer on to the lists.

Section 8 allows an independent panel to determine a conduct case against a senior officer, instead of the SPA. It gives an additional right to senior officers to appeal to the Police Appeals Tribunal (PAT)i against any decision to take disciplinary action short of dismissal or demotion against them in pursuance of conduct.

Liability of the Scottish Police Authority for unlawful conduct of the chief constable

The Bill provides that the SPA is liable in respect of any unlawful conduct on the part of the Chief Constable, or in the event that the office of Chief Constable is empty, is liable for whoever is acting as Chief Constable, in the carrying out (or purported carrying out) of their functions. This is in the same manner as an employer is liable in respect of any unlawful conduct on the part of an employee in the course of employment. The intention of this provision is to protect the victims of unlawful conduct by the Chief Constable.

The Policy Memorandum, that accompanies the Bill, explains that these provisions intend to address a “perceived gap in existing legislation”. This change “aligns the treatment of unlawful conduct by the Chief Constable with the existing treatment of unlawful conduct by other police officers”.

There was general agreement to this proposed change by those who provided evidence to the Committee.

In its written evidence, CRER recommended that any report on the misconduct of the Chief Constable be published. This is to ensure parity with senior officers, should the Bill introduce public gross misconduct hearings.

The Committee welcomes clarification that the SPA is liable for any unlawful conduct on the part of the Chief Constable.

The Committee asks the Scottish Government to clarify whether the intention is that any report on the misconduct of the Chief Constable will be published.

Procedures for misconduct: functions of the Police Investigations and Review Commissioner

PIRC is independent from the police. One of its key roles is to provide independent and impartial oversight of investigations. PIRC independently investigates incidents involving policing bodies in Scotland. These include incidents such as serious injuries or death following police contact, allegations of criminality by on-duty officers, and senior officer misconduct cases.

Section 5 of the Bill amends the 2012 Act to widen the functions that can be conferred on PIRC in secondary legislation, to include any aspect of the regulatory disciplinary procedures for senior officers, and not just misconduct investigations.

The Policy Memorandum explains that the regulatory changes enabled by the Bill in relation to senior officer conduct, will include PIRC having responsibility for “the assessment, investigation and presentation of cases”.

Misconduct investigations into the conduct of officers below the rank of Assistant Chief Constable will continue to be undertaken by Police Scotland.

The Angiolini review recommended that the preliminary assessment of a misconduct allegation about a senior officer “should be transferred from the SPA to PIRC in order to enhance independent scrutiny of allegations, remove any perception of familiarity, avoid any duplication of functions or associated delay, and give greater clarity around the process”. i

The current police misconduct procedures

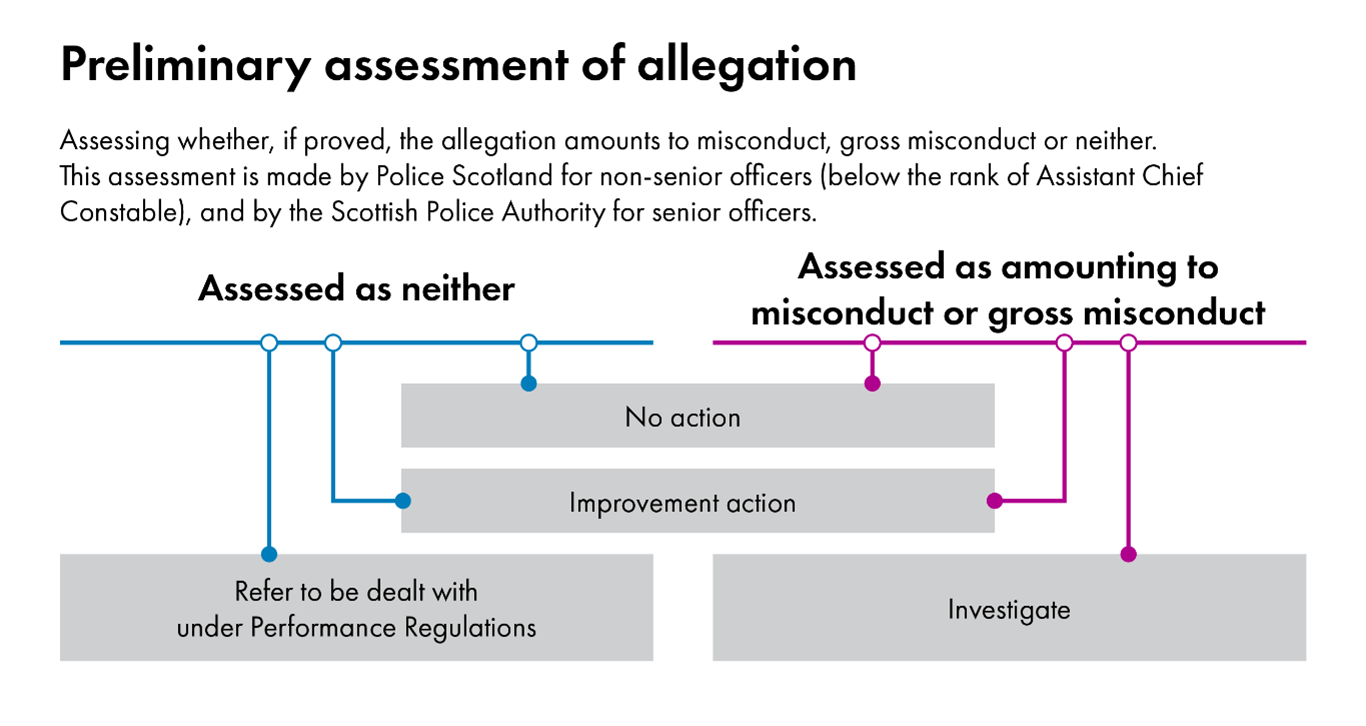

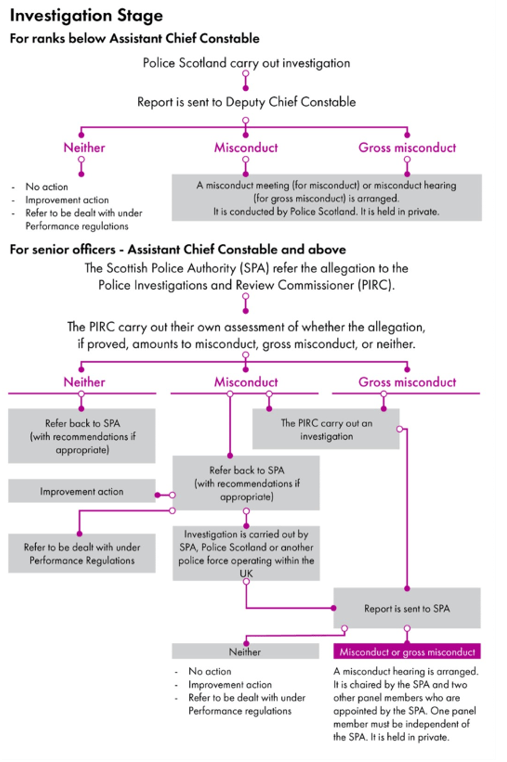

In scrutinising the proposed changes to the police misconduct procedures, the Committee considered the current procedures for misconduct and gross misconduct allegations against a senior officer, Assistant Chief Constable (ACC) or above, and police officers below that rank. The images below show these processes, and the current roles of the different organisations within them.

Image 1 provides an overview of the preliminary assessment stage of the police misconduct process, whilst Image 2 shows the process and the organisations involved in the investigation stage.

In scrutinising the proposed changes to the police conduct and complaints processes, the Committee considered the current roles of Police Scotland, the SPA, PIRC, and CAAPD and how the introduction of the provisions in the Bill would change them.

The tables below provide details of the current roles of each organisation and their proposed new roles in the complaints and conduct processes.

| Current Role | New Role | |

|---|---|---|

| Complaints | Receive all complaints for officers below the rank of Assistant Chief Constable (ACC) | NO CHANGE |

| Assess and investigate all complaints for officers below the rank of ACC | NO CHANGE | |

| Conduct | Carry out the preliminary assessment for all misconduct allegations for officers below the rank of ACC (to assess whether, if proved, the allegation amounts to misconduct, gross misconduct or neither) | Expands this role to include former officers. The intention would be that this would be up to a period of 12 months after the person ceased to be an officer. (PIRC have requested clarity on whether they or Police Scotland have to carry this assessment out during this period.) |

| Carry out the investigation into misconduct allegations for all officers below the rank of ACC | NO CHANGE | |

| Carry out misconduct meetings or hearings for all officers below the rank of ACC | NO CHANGE |

| Current Role | New Role | |

|---|---|---|

| Complaints | Receive all complaints for senior officers (ACC and above) | NO CHANGE |

| Receive all complaints for SPA and forensics staff | NO CHANGE | |

| Conduct | Carry out an assessment of whether, if proved, the allegation would amount to misconduct, gross misconduct or neither for senior officers | The ability to extend the functions of the PIRC will be introduced by the Bill which would allow this role to be moved to the PIRC. |

| Present the case at a misconduct hearing for senior officers | The ability to extend the functions of the PIRC will be introduced by the Bill which would allow this role to be moved to the PIRC. | |

| Chair the misconduct hearing and appoint the other two panel members (one panel member must be independent of the SPA) | The Bill enables regulations to be amended to provide for an independent panel to determine any conduct case against a senior officer. | |

| Current Role | New Role | |

|---|---|---|

| Complaints | Assess and investigate (if required) all on-duty allegations of assault (Article 3 breaches) and unlawful detention (Article 5 breaches) against police officers and staff | NO CHANGE |

| Carry out complaint handling reviews | Expands this role to enable PIRC to carry this out without a request from the complainer or the appropriate authority. | |

| Call-in and take over the consideration of complaints themselves. | ||

| Make recommendations following a complaint handling review | Expands this role so that these must be responded to by Police Scotland or the SPA setting out what they plan to do, have done, or explaining why nothing has been done. (This will also apply where they call in complaints or carry out an audit of the handling of arrangements for the information provided in whistleblowing complaints). | |

| Investigate deaths involving police officers | Expands this role to include officers from other UK forces carrying out policing functions in Scotland. | |

| Investigate serious incidents (includes serious injuries in police custody and the use of firearms by police officers) | Expands this role to include officers from other UK forces carrying out policing functions in Scotland. | |

| Investigate allegations of criminality by on-duty police officers and staff | The Bill clarifies that this includes any circumstances involving someone who is, or has been, a person serving with the police.Expands this role to include officers from other UK forces carrying out policing functions in Scotland. | |

| Carry out audit of the handling of Police Scotland and the SPA’s arrangements for the information provided in whistleblowing complaints. | ||

| Conduct | Carry out a further assessment of conduct allegations for senior officers to see if the allegation, if proved, would amount to misconduct, gross misconduct or neither (following the SPA’s preliminary assessment) | Carry out the preliminary assessment of conduct allegations for senior officers (instead of the SPA). Expands this role to cover former officers. The intention would be that this would be up to a period of 12 months after the person ceased to be an officer. |

| Carry out a preliminary assessment of allegations received for former officers where the allegation is received more than 12 months after the person ceased to be an officer. PIRC will determine if it is reasonable and proportionate to pursue proceedings after this period. | ||

| Investigate misconduct allegations for senior officers | NO CHANGE | |

| The Bill will introduce an enabling power that would allow the Scottish Government to confer further functions on to the PIRC – including the presentation of cases at senior officer misconduct hearings. |

| Current Role | New Role | |

|---|---|---|

| Complaints | Responsible for the investigation of criminal complaints against on-duty police officers | Clarifies that this includes allegations which include any circumstances involving someone who is, or has been, a person serving with the police.Expands this role to include officers from other UK forces carrying out policing functions in Scotland. |

| Conduct | No involvement in conduct proceedings | NO CHANGE |

The Committee also considered the types of conduct by police officers that would be found to be misconduct, gross misconduct or a performance issue.

Gross misconduct is defined in Regulation 2 of the Police Service of Scotland (Conduct) Regulations 2014 and the Police Service of Scotland (Senior Officers) (Conduct) Regulations 2013 as:

“a breach of the Standards of Professional Behaviour so serious that demotion in rank or dismissal may be justified.”

Examples of the outcomes of gross misconduct cases are shared publicly by Police Scotland through the SPA’s Complaints and Conduct Committee. The most recent report can be accessed here.

Police Scotland provided the Committee with some examples of behaviour that may fall within the categories of gross misconduct, misconduct and performance. Police Scotland clarified that each case is assessed based on the circumstances of the case and there is no prescribed list.

Gross Misconduct (Off Duty):

Allegations of serious criminality whether convicted or not (e.g. domestic / sexual offending)

Criminal conviction for serious matter (e.g. domestic offending, sexual offending, assault, drink driving, disorder offence with significant aggravator)

Controlled drug misuse

Gross Misconduct (On Duty):

Sexualised behaviour towards others (sexualised comments / behaviours)

Criminal Conviction for serious matter (e.g. neglect of duty, perjury, assault, theft)

Discriminatory behaviour (including inappropriate social media messaging)

Misconduct (Off Duty):

Criminal conviction for less serious matter (e.g. low level disorder with mitigation)

Inappropriate use of social media (not involving discriminatory behaviour)

Disorderly behaviour not leading to criminal charge

Misconduct (On Duty):

Absence without genuine reason

Oppressive type behaviour towards colleagues

Driving offence

Inappropriate use of language

Performance:

Repeated low level incivility / failure to take direction

Failure to adequately manage workload / investigate reports.

Views on the proposals in the Bill

In the evidence received by the Committee there was general agreement to remove this function from the SPA. However, questions were raised about whether the provisions are necessary and, if so, whether PIRC is sufficiently independent to ensure there is public confidence in it taking on these new responsibilities. A key area of concern for some is the number of former police officers who are employed by PIRC and their roles within the organisation.

Chief Superintendent Rob Hay told the Committee that ASPS does not think that legislation is required to deal with the issues of gross misconduct in the police service. He indicated that if the current regulations were applied, issues of performance would be dealt with more effectively. Chief Superintendent Hay acknowledged that—

“There is a question about what is sufficient to satisfy the Parliament and our oversight bodies that we are taking the necessary steps and about what is sufficient to embed public trust and confidence”.i

David Kennedy said that the SPF shares this view, telling the Committee that the legislation and regulations that are currently in place “must be adopted properly”. Mr Kennedy explained that a lot of low-level performance issues could be dealt with at source, without requiring the view of the Crown Office about whether or not a crime has been committed, adding that many officers leave the service “not because they have been found guilty of misconduct but because what the system puts them through absolutely destroys them”.i

Lady Elish Angiolini told the Committee that she does not agree with this view, saying that whilst she accepted “there should not be an automatic reference to discipline” for management and welfare issues, there is a need for a legislative framework. Lady Angiolini said that—

“I do not think that having a voluntary version is good enough for an organisation that has so much power. It is really important that there is a structure to that”.iii

Preliminary assessment and investigation of senior officer misconduct allegations

The Committee heard conflicting views on the proposal to transfer responsibility for the preliminary assessment and investigation of allegations of misconduct against senior officers from the SPA to PIRC.

The Commissioner, Michelle Macleod, told the Committee that she had received confirmation that for the section 5 misconduct provisions: “our role will remain in relation only to senior officers”, and stated that she was content for PIRC to take on the preliminary assessment and investigation roles for senior officers.i

The Angiolini review heard concerns from members of the public about the degree of impartiality of PIRC’s investigations as, at that time, former police officers made up 51% of PIRC’s investigators. Lady Angiolini recommended that—

“Following the retirement of former police officers PIRC policy should be to replace them with non-police officers. The PIRC should also adopt a similar policy to the IOPC’s in England and Wales by recruiting non-police officers when recruiting to the most senior posts”.ii

The most recent data available to the Committee indicates that the number of former police officers working for PIRC has reduced to 39, or 41% of its staffing complement.iii

In correspondence to the Committee, the Cabinet Secretary for Justice and Home Affairs confirmed that “The PIRC have told the Scottish Government that only 13% of PIRC staff involved in the complaint review side have a policing background”.

In its written evidence, the CRER said that the number of former officers employed by PIRC, “means that it would be difficult to trust the impartiality of the organisation” They recommended that the “PIRC be reformed to ensure its independence from Police Scotland and SPA”.

Dr Genevieve Lennon, SIPR, told the Committee that it is “the norm internationally, that police officers are excluded from senior positions”, in police complaints bodies. Dr Lennon explained that—

“By law, none of the current complaints bodies across the UK—the Independent Office for Police Conduct in England or Wales, the Northern Ireland ombudsman or indeed PIRC—can have serving officers in such roles. They have lists of people who are excluded from the most senior leadership, and they include senior officers. That is standard now”.iv

Magdalene Robertson told the Committee that she was concerned that those within PIRC who were investigating her complaints might have relationships with the senior officers under investigation. Ms Robertson’s request seeking clarification on this issue from PIRC was denied. She said that—

“I would like clear freedom of information, given before the PIRC even does the investigation. It should provide a statement of fact that PIRC officers either know or do not know the officers who have been complained about”. v

HM Chief Inspector of Constabulary, Craig Naylor told the Committee that HMICS is aware of difficulties with PIRC, such as “deference being paid to senior officers during various investigations” and “declaring conflicts of interests”. The Chief Inspector said that “people who have worked together should be prevented from investigating one another. That is key”. He suggested that something “be built in about declaring conflicts and preventing people who have worked together, or for someone else, from being involved in such an investigation”.vi

In its written evidence to the Committee, CRER questioned whether PIRC is the right organisation to carry out a preliminary assessment of allegations against senior officers, as the Policy Memorandum acknowledges that—

“While this alone does not meet the policy aim to enhance independent scrutiny and remove any perception of familiarity in the conduct process, it will allow Scottish Ministers to confer functions on the PIRC in relation to procedures for misconduct, which should in turn lead to a fairer and more transparent process”.

The Cabinet Secretary confirmed to the Committee that PIRC has adapted its recruiting practices, and there is “an acceptance that broader diversity among the people coming into the organisation is needed and that policing is not the only area in which people develop experience and skills in investigation”.vii

The Committee welcomes the new powers set out in the Bill for secondary legislation to enable PIRC to carry out the initial assessment and investigation of misconduct allegations about senior officers, as this will enhance independent scrutiny of allegations and remove any perception of familiarity between senior officers and the SPA.

The Committee recommends that PIRC should continue its policy to reduce the reliance on the employment of former police officers and introduce procedures to ensure that people who have worked together previously must declare an interest and are prevented from investigating one another.

Should the PIRC assess and investigate misconduct allegations against all officers?

The Committee considered whether responsibility for the assessment and investigation of all misconduct allegations should be undertaken by PIRC, or whether this should remain the responsibility of Police Scotland’s professional standards department for non-senior officers.

In correspondence to the Committee, the Cabinet Secretary for Justice and Home Affairs clarified that sections 5, 6 and 8 of the Bill make various changes to the disciplinary procedures, and outlined the legislative basis for dealing with conduct issues, as follows—