Neurodevelopmental Pathways and Waiting Times in Scotland

The number of children and adults seeking assessments for conditions such as autism and ADHD has grown dramatically over the last decade. This has led to increased pressure on Scotland's neurodevelopmental services. This briefing examines the current provision for neurodevelopmental assessment in Scotland, with a focus on diagnostic pathways and waiting times across NHS boards.

Summary

It is estimated that 10-15% of the population in Scotland is neurodivergent, meaning that a person's selective neurocognitive functions (such as the ability to learn and use language, or regulate attention, emotions and impulses) fall outside the usual range. Examples of neurodevelopmental conditions include autism, a lifelong condition affecting around 3% of people1, and ADHD, which affects around 5% of children and 2.5 - 4% of adults. These conditions frequently co-occur with each other2.

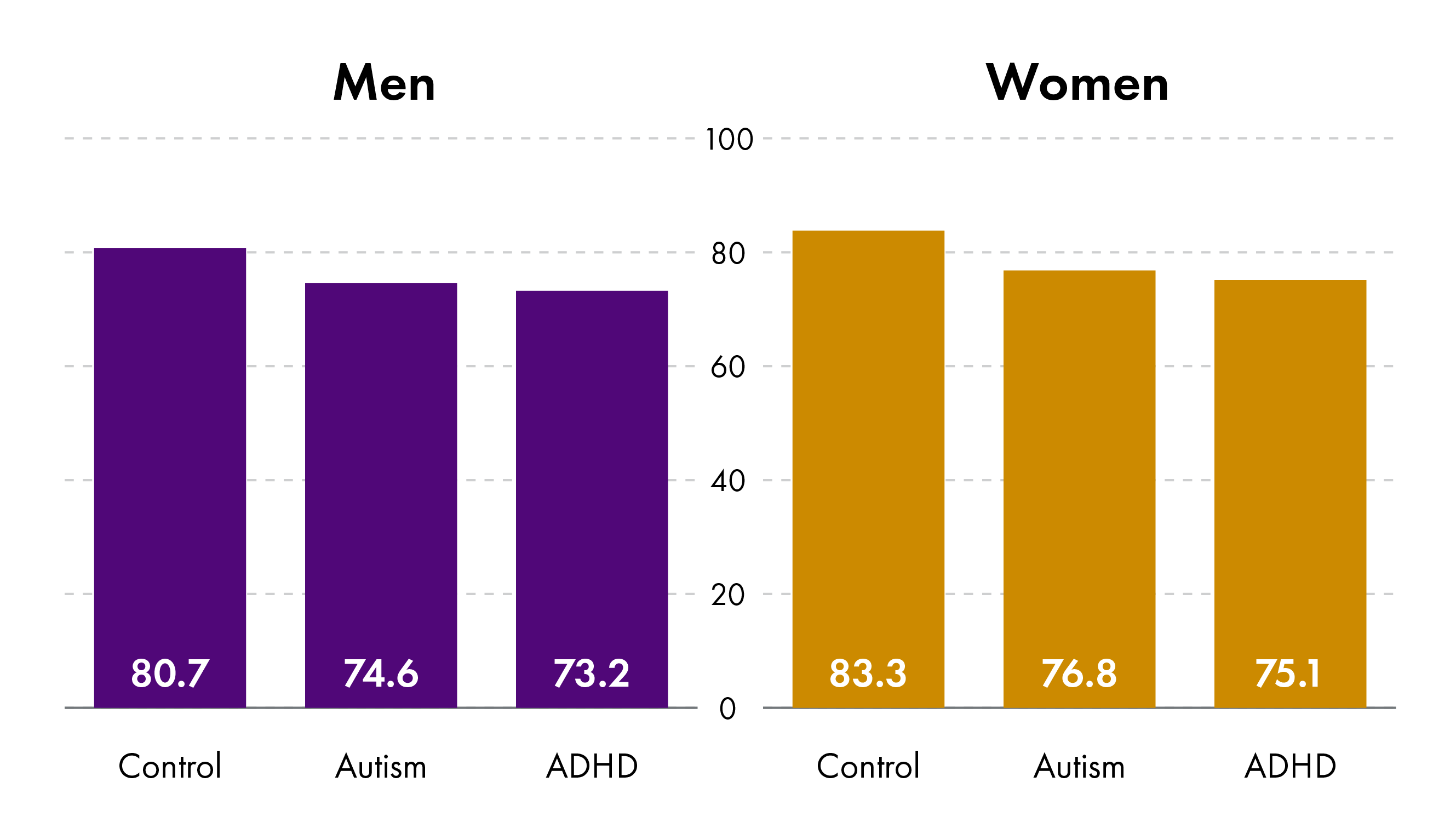

While a range of support services, environmental modifications, medications and therapies are available for people with some neurodevelopmental conditions, neurodivergent people can experience significantly poorer health and social outcomes. These can include discrimination, stigma, worse mental health outcomes and shorter life expectancy. In addition, while autism and ADHD have historically been thought to affect predominantly males, evidence now suggests that neurodivergent womenare systematically under-diagnosed due to a lack of societal understanding of the range of autism and ADHD presentations. Neurodivergent people from minority ethnic groups, who may exhibit different symptoms of neurodivergence, also experience this additional disadvantage and stigma.

While neurodivergence is not a mental health condition, the barriers and difficulties faced by neurodivergent people often lead to mental health conditions3. Neurodivergent children and adults who meet the criteria for secondary mental health services due to co-occurring mental health conditions are diagnosed and treated for those conditions through those services. These services are either Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS), or adult mental health services. They will also receive assessment and support for neurodevelopmental conditions through those services.

The Scottish Government's National Neurodevelopmental Specification sets out standards of care for all children and young people with neurodevelopmental differences, regardless of whether they meet the CAMHS criteria. This has led to the implementation of children's neurodevelopmental pathways in many areas of Scotland, bringing together local services (such as health and social care, education and community support) within a whole-system approach. Much of this work focuses on the creation of multi-disciplinary teams to triage, diagnose and support children with neurodevelopmental conditions. This is in line with guidance from groups such as the National Autism Implementation Team. Successful implementation of these pathways also requires efficient collection and use of data to understand demand and capacity.

The provision of both support and assessment for neurodivergent people varies significantly across Scotland. Pathways for neurodivergent children to obtain a neurodevelopmental assessment have been implemented in every NHS board, although the mode of access and delivery can vary. In addition, NHS Tayside has recently stopped accepting new referrals for neurodevelopmental assessments for children and young people who do not meet the CAMHS referral criteria.

Data presented in this report shows that as of March 2025, over 42,000 children were waiting for a neurodevelopmental assessment, and that in some areas this figure has increased by over 500% since 2020. Across the health boards surveyed, on average, the longest waiting time for a child to receive an assessment was 196 weeks (nearly four years). This is due to the increase in demand for neurodevelopmental assessments massively outstripping the services' capacity to deliver them. However, support is available for neurodivergent children who don't have a diagnosis, most commonly through local authorities and their provision of Additional Support for Learning.

Increased awareness of neurodivergence in adults has also led to a surge in demand for adult neurodevelopmental assessments, and the data in this report suggests that there were over 23,000 adults waiting for a neurodevelopmental assessment in Scotland as of March 2025. In areas for which data is available, the number of adults waiting for an assessment has increased by over 2200% since 2020. Despite this demand, adult neurodevelopmental pathways are not available in many NHS boards across Scotland, and in some areas adult assessment services have been withdrawn in recent months. In areas for which data is available, the average longest waiting time to receive an assessment is 182 weeks (three and a half years).

Long waiting times have resulted in more people using the private sector to obtain a neurodevelopmental assessment, which may lead to financial hardship4. In some cases, patients who have received a private diagnosis enter a shared care agreement, whereby they receive their medication through an NHS prescription. However, in many areas GPs do not accept private diagnoses and do not enter such agreements, meaning that the patient may have to pay for medication themself.

Increased demand for support has also led to increased pressure on thethird sector, which provides a range of pre- and post-diagnostic support for neurodivergent people in Scotland. In areas such as Fife, third sector organisations are formally involved in neurodevelopmental pathways, where they provide support and services in tandem with local authorities. The Royal College of Psychiatrists in Scotland and the Child Heads of Psychology Services in Scotland have called for a restructuring of neurodevelopmental pathways in Scotland, in which the third sector would play a more formalised role nationally. This would build on schemes already funded by the Scottish Government, such as the National Autism Post-Diagnostic Support Service and the Autistic Adult Support Fund.

Neurodivergent people may also receive a range of support outside the NHS and third sector. This can include in employment, where they may be eligible for reasonable adjustments in the workplace under the Equality Act 2010, in education, where they may require additional support needs under Getting It Right For Every Child (GIRFEC) policy, and in social security mechanisms, where they may be eligible for disability payments.

Post-diagnostic support also plays an important role in helping a neurodivergent person to understand their needs and the strategies for addressing them. This should be part of the neurodevelopmental pathway, although it can take highly variable forms including clinical support, education programmes and peer-led support.

The National Neurodevelopmental Specification states that none of this support should be diagnosis-dependent; in all cases, services should provide support on a needs-based, case-by-case basis. However, many neurodivergent people have found that accessing these services can be difficult, particularly without a formal diagnosis.

This briefing presents up-to-date data on the current waiting lists and waiting times for neurodevelopmental assessments across Scotland. It sets out the current and future policy for neurodivergent people in Scotland and surveys the current provision of neurodevelopmental pathways across all fourteen territorial NHS boards. It also explores the issues outlined above, to provide a picture of the major challenges facing both policymakers and neurodivergent people themselves in Scotland.

Cover photo of Scottish Parliament

Neurodevelopmental pathways and waiting times

Neurodivergent children and adults in Scotland are waiting longer than ever to be assessed for neurodevelopmental conditions such as autism or ADHD, to the point that the situation has been labelled by some as a 'crisis'. There are significant bottlenecks in the pathway between referral and assessment, and in some cases this has led to health boards withdrawing diagnostic services altogether. This has created challenges accessing diagnosis and support for many people, and this briefing will explore these issues. It will first present up-to-date information on neurodevelopmental pathways and waiting times across Scotland. It will then examine the present and future policy provisions and the current neurodevelopmental pathways available for children and adults in Scotland. The last section explores other issues impacting neurodivergent people in Scotland, and the next steps to be taken in this area.

Overview

This section introduces neurodevelopmental pathways and waiting times. It begins by defining the key terminology used in this briefing and setting out the language used when discussing these topics. It then discusses the evidence surrounding the prevalence of neurodevelopmental conditions in Scotland.

Definitions and language

This section defines the terms used in this briefing. The meanings of these terms have changed over time, and are not universally agreed, but the definitions in this report align with those used in the Scottish Government's National Neurodevelopmental Specification.

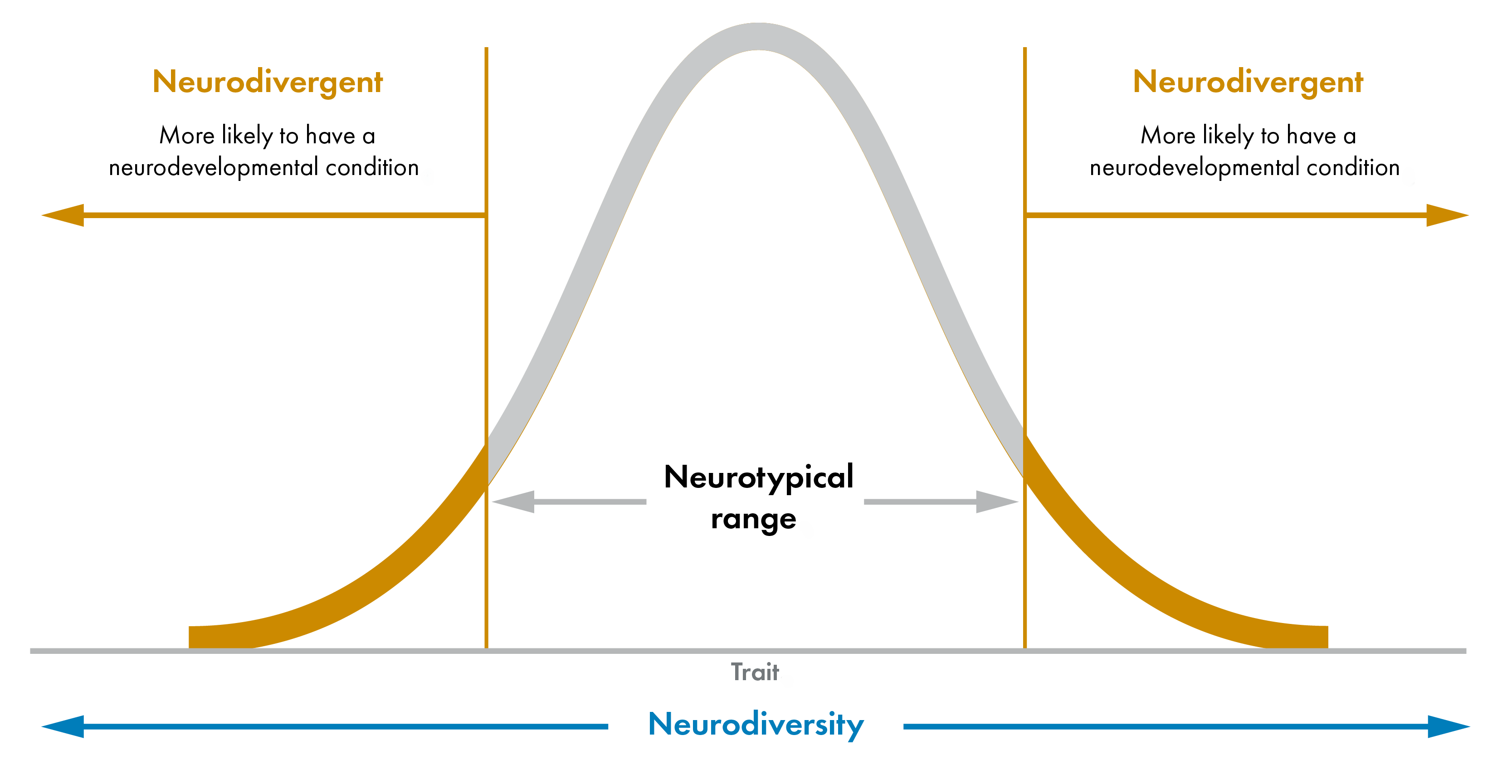

Neurodiversity: The natural variation in brain development in the population as a whole. This is a property of a group, rather than of a single individual, and a person cannot 'be neurodiverse' or 'have neurodiversity'. There is no formal definition of neurodiversity in Scottish law, but this definition aligns with that provided by the Scottish Deanery.

Neurocognitive functions: Selective aspects of brain functions, including:

the ability to learn and use language

the ability to regulate attention, emotions, impulses (including movements and spontaneous utterances)

social behaviours

processing sensory stimuli.

These traits may be significantly genetically influenced1, and are present from birth. The statistical normal range changes, dependant on age.

Neurodivergence: When an individual's selective neurocognitive functions fall outside the typical range. This includes, but is not limited to, conditions such as autism, attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), dyslexia, dyscalculia, developmental co-ordination disorder (DCD), developmental language disorder (DLD), Foetal Alcohol Syndrome Disorder (FASD) and Tourette's syndrome. These specific conditions are also referred to as neurodevelopmental conditions, although conditions such as dyslexia and dyscalculia are also termed learning difficulties by some people. Of the neurodevelopmental conditions listed above, this briefing will mostly focus on autism and ADHD (see below), although not all neurodivergent people have a specific neurodevelopmental condition. A neurotypical person is someone whose variation in brain development falls within the the typical range. This is shown in the figure below.

Autism: A lifelong developmental condition that affects the way a person communicates, interacts, and processes information. It is also known as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), reflecting the wide range of how autism presents in different individuals and the varying levels of support needed. Current estimates indicate about 1 in 34 people are autistic (just under 3% of the population)3. This would suggest there are approximately 160,000 autistic people in Scotland as of 20234. Current thinking advocates for a 'neuro-affirming' paradigm that would not seek to fix or cure autistic people, but rather to take a ‘difference not deficit’ approach5. This recognises different ways of being rather than a focus on impairment and disability, and focuses on adapting the physical and social environment around the autistic person to suit their needs.

Attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): A group of behavioural symptoms that include difficulty in concentrating, hyperactivity, and impulsiveness. Research indicates that ADHD affects around 1 in 20 school aged children (5% of the population), and between 1 in 25 and 1 in 40 adults (2.5-4%). This would suggest that there are between 150,000 and 220,000 people living with ADHD in Scotland as of 2023. While the cause is unknown, medication can help to relieve the symptoms and is often prescribed in combination with a neuro-affirming approach. However, less than 30% of children estimated to have ADHD (and less than 10% of adults) are prescribed medication in Scotland6.

Neurodevelopmental pathway: The framework for assessing a neurodivergent person for a range of conditions and providing support before, during and after this assessment. This briefing will focus on mainly the assessment stage, although the National Neurodevelopmental Specification for Children and Young People outlines the importance of support regardless of diagnosis. Neurodevelopmental pathways are different to single-condition assessments or pathways, such as autism or ADHD pathways, in that they consider the whole profile of the individual patient and may diagnose more than one neurodevelopmental condition. NHS Education for Scotland mentions "increasing support for taking a 'neurodevelopmental' approach to understanding the range of ways children, young people and adults present".

We recognise the importance of the terminology used in reference to the various groups discussed in this briefing. Following the responses to the Scottish Government's consultation on the Learning Disabilities, Autism and Neurodivergence Bill, we use identity-first language (i.e. 'autistic person', 'neurodivergent person') wherever possible when discussing neurodivergence. We also recognise that neurodivergence is not a mental health condition and should not be treated as such, although neurodivergent people are more likely to experience mental and physical health challenges in their lifetimes.

Prevalence of neurodivergence in Scotland

Recent evidence suggests that 10-15% of the population in Scotland are neurodivergent in some way1. This falls in line with estimates made for the UK as a whole2. This number also seems to be roughly consistent across adults and children, with one study suggesting a rate of neurodivergence of roughly 16% in primary school children in 20223.

The most common neurodevelopmental conditions are thought to be dyslexia and dyscalculia, affecting 10% and 6% of the population respectively45. ADHD is estimated to affect 5% of school aged children in Scotland6, while autism affects roughly 3% of this group3. Given the lifelong nature of such conditions, prevalence in adults is similar, with 2.5-4% of adults living with ADHD8 and approximately 2.2% having autism9. The differences are likely due to a lower rate of diagnosis of these conditions in adults.

A person with one neurodevelopmental condition has a much greater chance of also having another. Studies have estimated that nearly 40% of autistic people also have ADHD or other forms of neurodivergence and/or a learning disability, and others put the number even higher1011. As a result, it may be harder to diagnose both conditions accurately. Furthermore, the traits of one may exacerbate the other. Having both autism and ADHD has been found to increase the likelihood of developing conditions such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression and anxiety12.

Diagnosis of these neurodevelopmental conditions varies between sexes. According to the Scottish ADHD Coalition, men are three to four times more likely to be treated for ADHD than women, although this is more likely due to under-diagnosis of females rather than a difference in true prevalence13. This could be because the symptoms of ADHD in females frequently present differently to symptoms in males, and are noticed less often by families and teachers1415. While males are more likely to show impulsive and hyperactive symptoms, females tend to exhibit more inattentive and internal behaviours and are more likely to 'mask' their symptoms. Since these behaviours are less disruptive, they are often missed and can be misdiagnosed as symptoms of anxiety or depression.

Autism is also more prevalent in men than in women, although as with ADHD there is some debate as to whether this is due to a true difference in the underlying prevalence, or whether autism is simply under-diagnosed in women. Current estimates have the ratio of autistic males to females as 3:1. Some feel that autistic women and girls often present different characteristics to autistic men and boys, which don't fit the traditional profile of autism and are therefore missed by many assessments. In addition, autistic women and girls are more likely to successfully mask their symptoms than men and boys16. The difficulties facing autistic women and girls are discussed in more detail in the issues section.

Recent evidence also suggests that the prevalence of people diagnosed with a neurodevelopmental condition and those identifying as neurodivergent has increased over the last decade. One study found an increase of over 10% in neurodivergence - and over 30% in cases of autism - in Scottish primary schools between 2018 and 20223. In other statistics, the increase is far more dramatic. For example, the Salvesen Mindroom Centre in Edinburgh (a charity working with neurodivergent people) reported a 295% increase in the number of neurodivergent people it worked with between 2020 and 2024. In Glasgow, there was a 1000% increase in referrals for assessment of adult ADHD to Community Mental Health Teams between 2018 and 2021. These increases are almost certainly due to an increase in awareness of neurodivergence as a phenomenon, as opposed to an increase in the proportion of people who are neurodivergent, and this is discussed further in the issues section.

Waiting times for neurodevelopmental assessment in Scotland

This section begins by outlining previously available data about waiting times for neurodevelopmental assessment in Scotland, and in the United Kingdom more broadly. Historically, these data have only been available through one-off publications and Freedom of Information requests.

In March 2025, the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee wrote to each of the fourteen NHS territorial boards requesting information on neurodevelopmental pathways and waiting times. All boards responded, and the following sections summarise the responses received.

It is worth noting that data concerning waiting times and waiting lists for neurodevelopmental assessments, while informative in understanding the discrepancy between demand and capacity, does not give information about how long people are waiting for support in each area. The Scottish Government has stated that support should not be dependent on diagnosis, and should be available for those waiting for assessment or not seeking one. The National Neurodevelopmental Specification notes that:

understanding of support needs can be enhanced by diagnosis but should not wait for diagnosis.

Scottish Government, National Neurodevelopmental Specification for Children and Young People, 2021

Nonetheless, neurodivergent people report that the experience of waiting causes significant stress and anxiety, and so the following data is important in understanding and improving their experience1.

Previous data on waiting times for neurodevelopmental assessment in Scotland

Significant interest has surrounded the subject of waiting times for mental health diagnosis in Scotland. Public Health Scotland regularly publishes waiting times data for referrals to Children and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS). The national target is for 90% of patients to start treatment within 18 weeks of referral for all CAMHS treatment. In March 2025, the CAMHS data showed that this target had been met for the first time in the period September-December 2024. The target was met again in the following quarter, January-March 2025. This came after less than 70% of patients were being seen within 18 weeks as recently as 2022.

In the past, neurodevelopmental cases were included in CAMHS waiting time statistics. However, in recent years these have been separated out. This is done in recognitiono of the fact that neurodivergence is not a mental health condition and that, unless they meet the national referral criteria for treatment by CAMHS, neurodivergent children do not need to be 'treated' in a medical sense. As such, they are not recorded as patients requiring mental health support. The removal of neurodevelopmental cases led to some politicians commenting that:

The only way that ministers have been able to meet their target on waiting times for child and adolescent mental health services has been by removing from the waiting times figures young people and children who were waiting for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and autism diagnoses.

Miles Briggs MSP, First Minister's Question Time, 3 April 2025

However, these accusations have been refuted, with the Minister for Social Care, Mental Wellbeing and Sport stating that:

CAMHS is not the correct service for children who are seeking a diagnosis for neurodevelopmental conditions such as ADHD, unless they have a co-existing mental health condition. For many young people, a neurodevelopmental pathway will ensure that the right help and support is provided.

Minister for Social Care, Mental Wellbeing and Sport (Maree Todd), Portfolio Question Time, 7 May 2025

Data concerning waiting times specifically for neurodevelopmental assessment has previously only been made available via Freedom of Information requests and one-off publications. For example, NHS Lothian disclosed the average waiting times for children and adults seeking a neurodevelopmental assessment in May 2024. In the year 2023/2024, adults and children were waiting an average of 101 and 68 weeks, respectively, for assessment. NHS Tayside reported an average waiting time of 37 weeks for the period September 2024-December 2024. These data show only snapshots of the situation at a single moment in time, and no data on the long-term trends in waiting times is routinely published.

One study looked at neurodevelopmental assessments (n:408) completed by ten of the fourteen NHS Scotland territorial boards between October 2021 and May 20221, and compared waiting times to the 36-week standard recommended by the National Autism Implementation Team. It found that the mean time for a patient to undergo the entire assessment process from referral was 52 weeks for adults and 82 weeks for children, both far greater than the recommended standard. While mean values can be skewed by long waiting times, the median wait time was 36 weeks for adults and 75 weeks for children, and only 47% of cases (20% for children) met the 36-week standard.

Elsewhere, NHS England routinely publishes autism assessment waiting times on its dashboard. The National Institute of Care Excellence (NICE) guideline is that patients should have their first appointment for assessment within 13 weeks of referral. In March 2025, less than 5% of both children and adults with a referral met this threshold, down from 12% in December 2019. The Children's Commissioner for England reported in 2024 that the median wait time for a neurodevelopmental assessment was 117 weeks. In October 2023, ADHD UK surveyed various UK NHS Foundation Trusts and found waiting times varying hugely, from 5 to 264 weeks for children, and 12 to 550 weeks for adults. Unlike in Scotland, patients in England may choose a private provider for autism and ADHD diagnosis under the Right to Choose scheme. Under this scheme, the NHS covers the cost of a private diagnosis. This is available to patients who are registered with a GP in England and have received a referral for an ADHD or autism diagnosis.

Number of children and adults on waiting lists

This section will summarise the data received by the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee regarding the number of children and adults waiting for a neurodevelopmental assessment as of 31st March 2025. For more details on the neurodevelopmental pathways in each NHS board, see the neurodevelopmental pathways section.

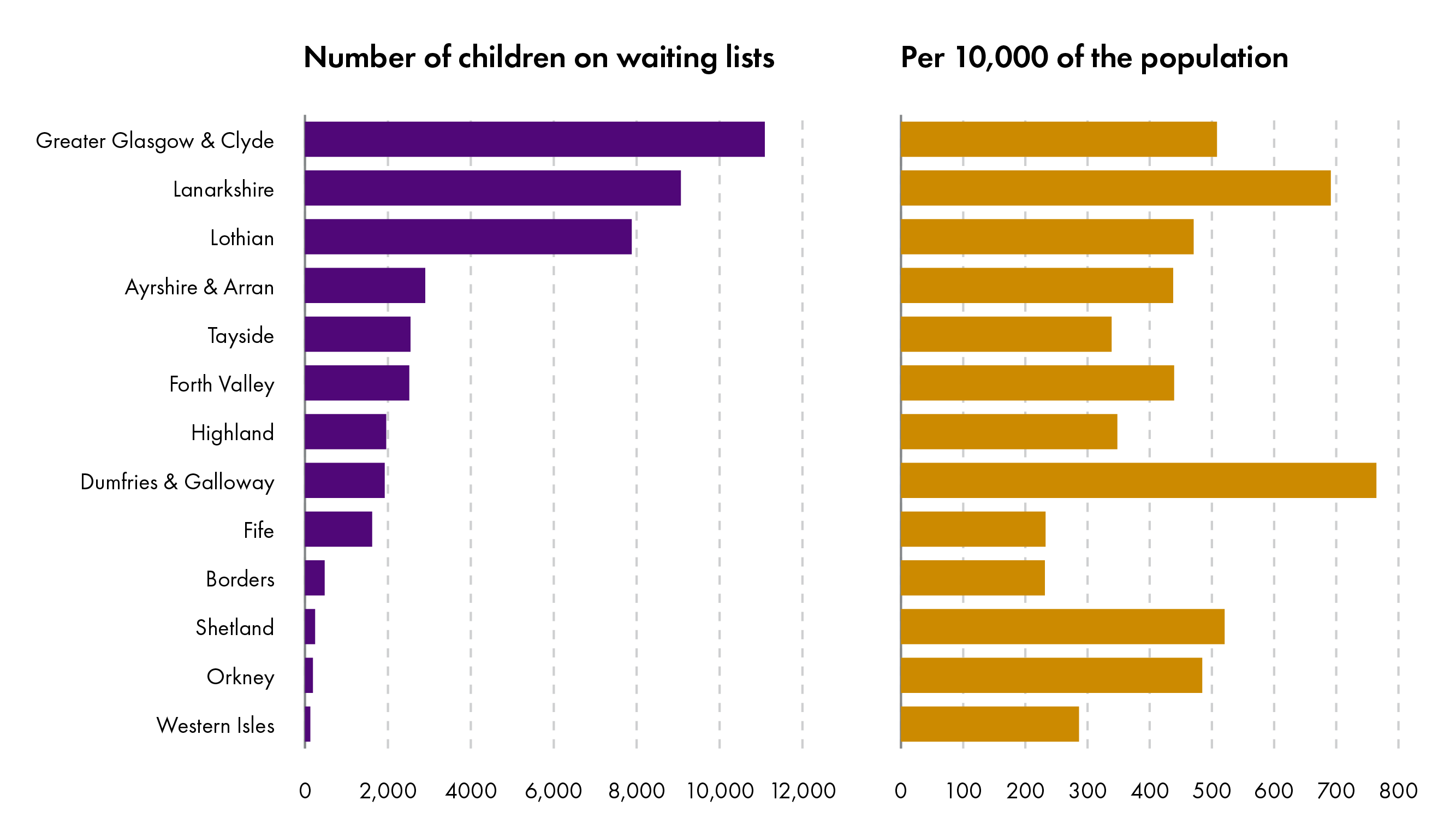

Children

As of 31st March 2025, all health boards (with the exception of NHS Tayside, who were not accepting new referrals) had neurodevelopmental pathways for children who didn't meet the criteria for referral to CAMHS. Thirteen of the fourteen health boards reported the number of patients waiting for this service (except for NHS Grampian, who could not provide this figure). The data show that there were 42,530 children waiting for a neurodevelopmental assessment. This amounts to approximately one in twenty-five children aged 0-18, based on 2023 population estimates1. Figure 2 shows the breakdown of these across health boards.

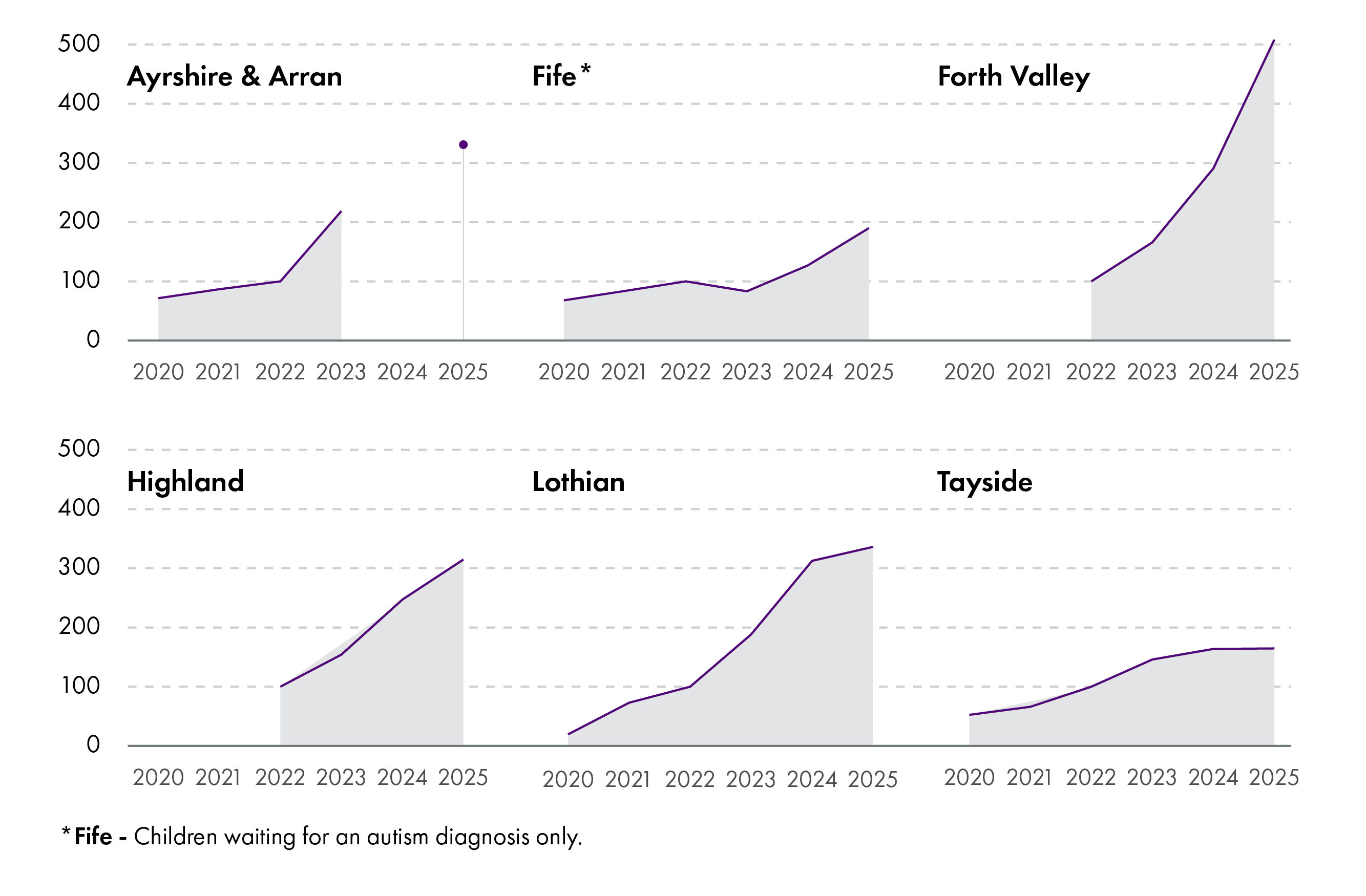

Eight health boards (Ayrshire and Arran, Fife, Lothian, Tayside, Borders, Forth Valley, Greater Glasgow and Clyde and Highland) were able to provide data on the length of waiting lists in previous years, although only the first four provided data going as far back as 2020. This data is shown in figure 3 below, which shows that the number of children waiting for a neurodevelopmental assessment in Ayrshire and Arran, Fife, Lothian and Tayside increased from 2,475 to 14,943 between 2020 and 2025 - an increase of over 500%. This is more likely due to a large increase in the number of people seeking assessments, as opposed to an increase in the number of people with neurodevelopmental conditions.

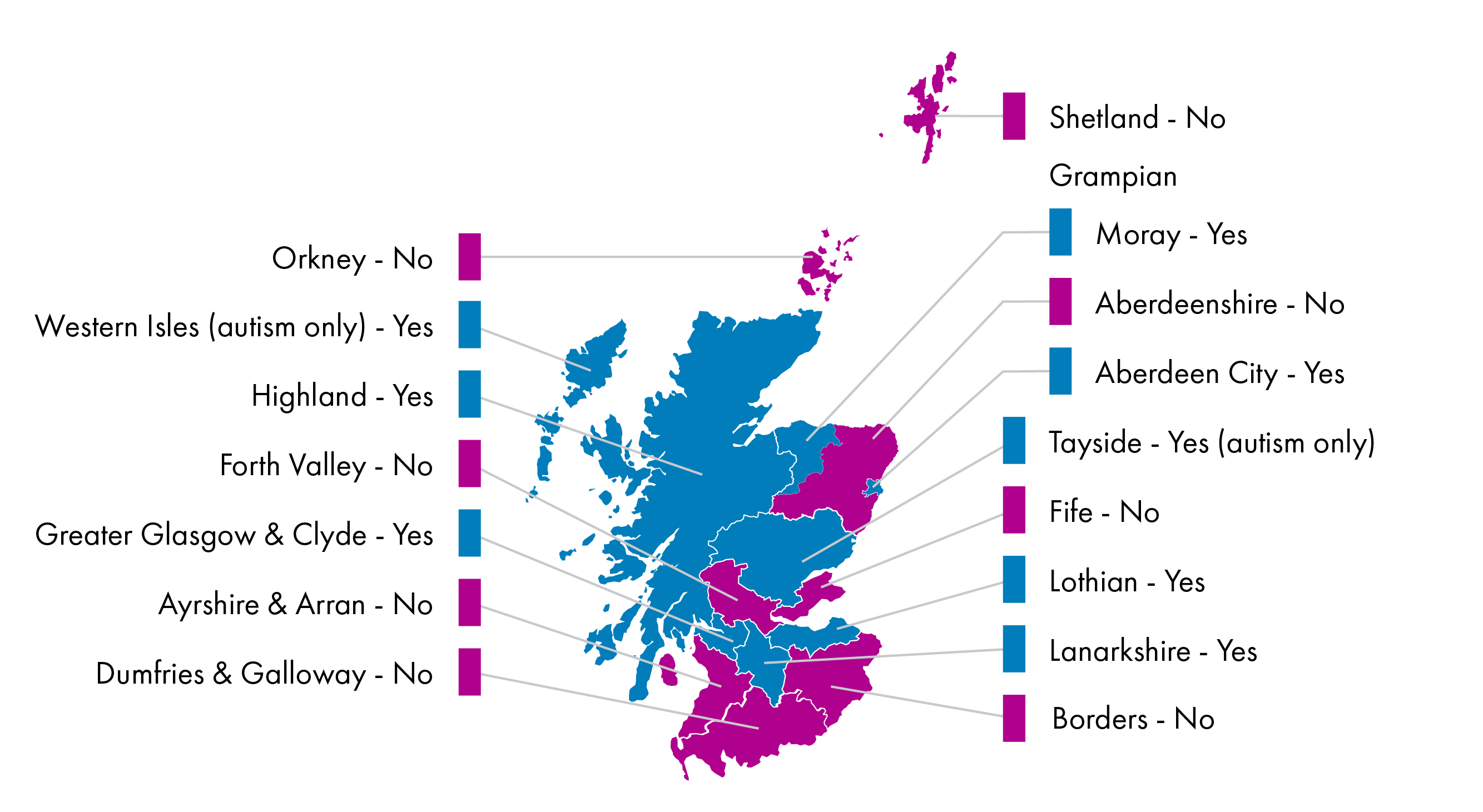

Adults

Health boards reported that a neurodevelopmental pathway was available to adults who did not meet the criteria for referral to secondary mental health services in six health boards (Greater Glasgow and Clyde, Lanarkshire, Lothian, Tayside, Highland and Western Isles), although in Tayside and Western Isles this was for autism only. In NHS Grampian, the provision was different across the three Health and Social Care Partnerships (HSCPs) since Aberdeenshire HSCP ceased its adult neurodevelopmental pathway in February 2025. This is summarised in figure 4.

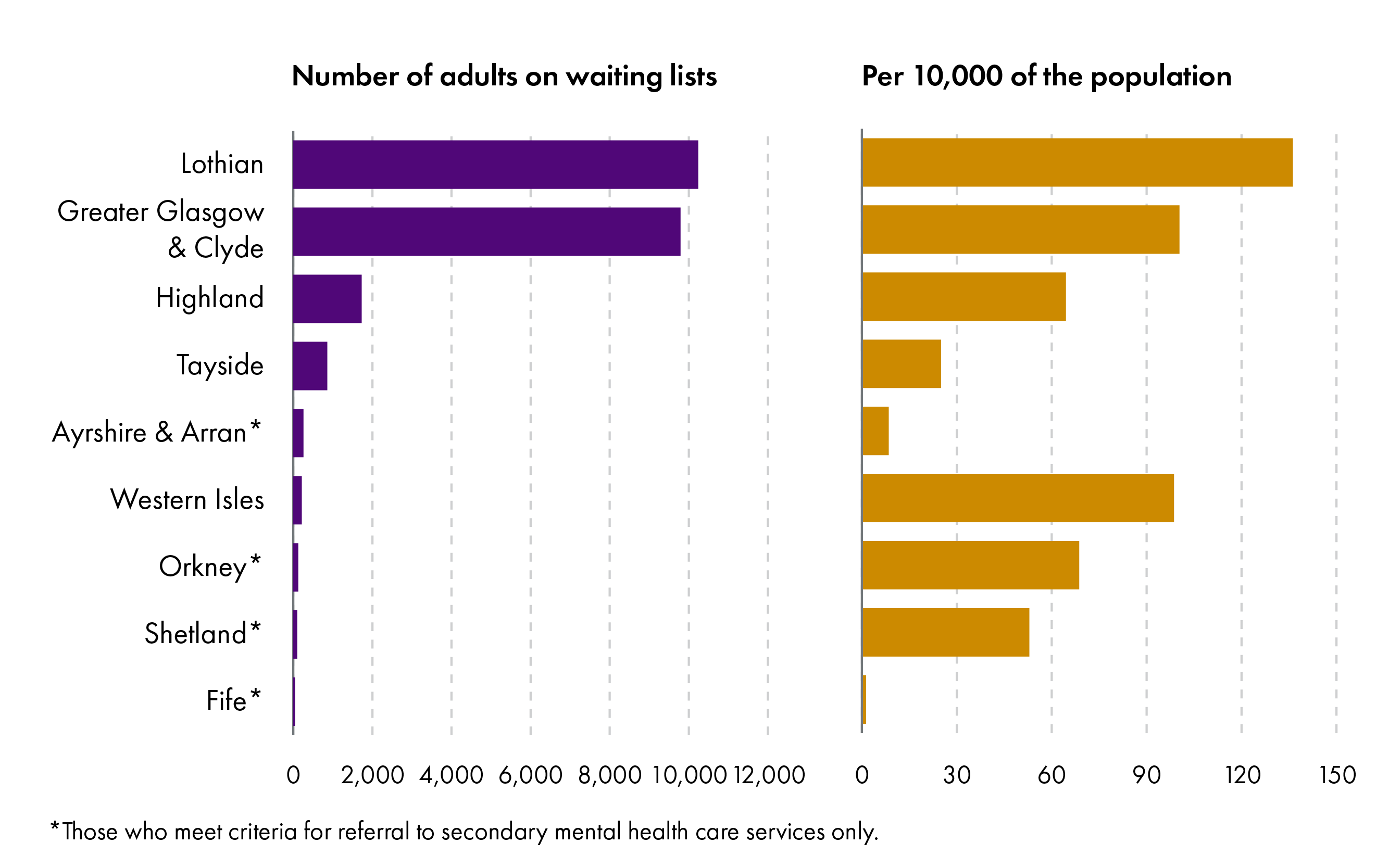

Nine health boards disclosed the number of adults waiting for a neurodevelopmental assessment in their areas. These were five of the health boards with adult neurodevelopmental pathways in place (Greater Glasgow and Clyde, Highland, Lothian, Tayside and Western Isles but not Lanarkshire) and four of the boards which offered neurodevelopmental assessments only to those who met the criteria for referral to secondary mental health services (Ayrshire and Arran, Fife, Orkney and Shetland).

There were 23,339 adults reported as waiting for a neurodevelopmental assessment as of March 2025, and over 97% of these were in areas where adults did not have to meet the criteria for referral to secondary mental health services to access the services. The breakdown by health board is shown in figure 5.

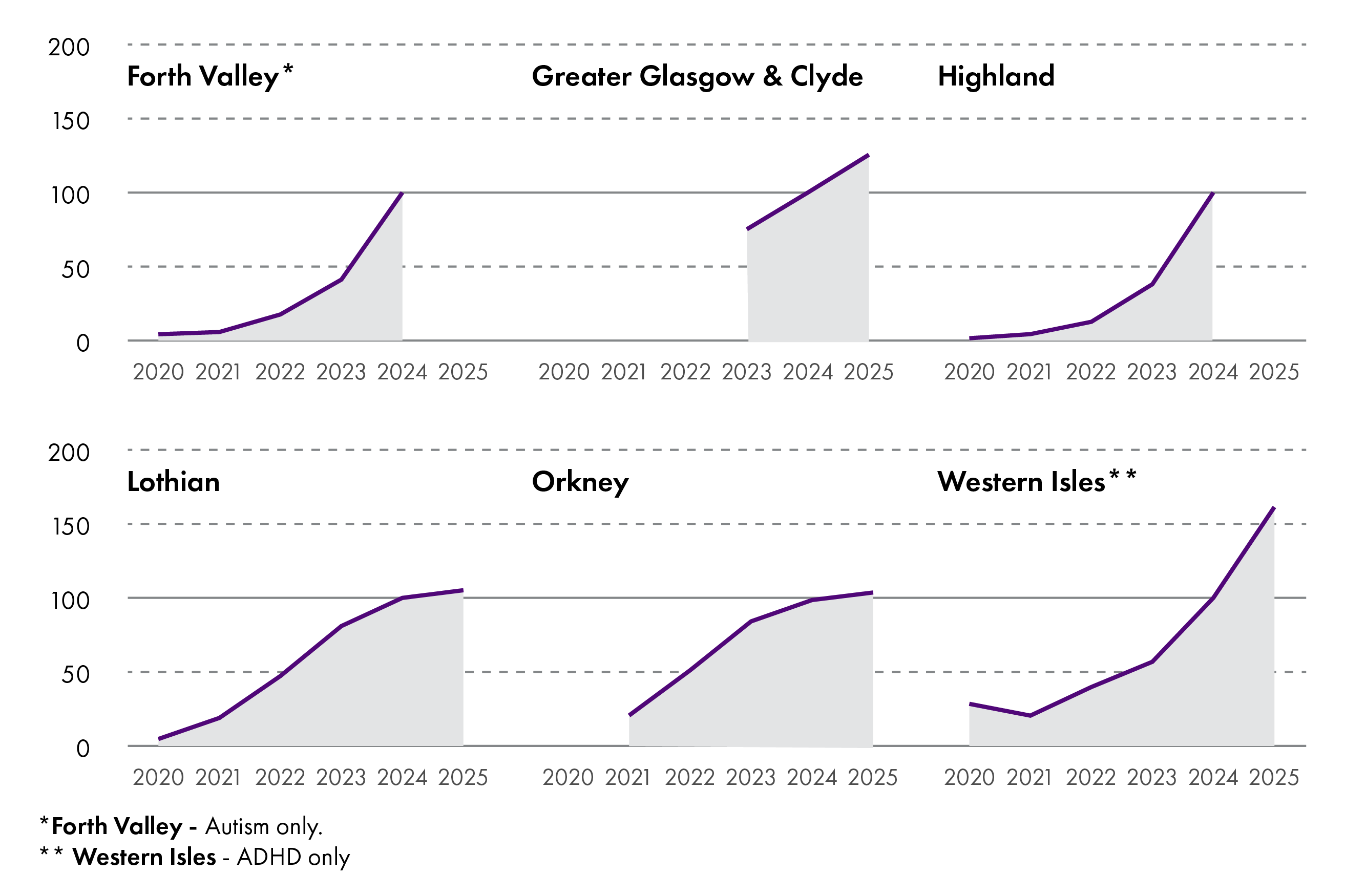

Six health boards (Forth Valley, Highland, Lothian, Western Isles, Greater Glasgow and Clyde and Orkney) were able to provide data on waiting lists lengths for previous years, although only the first four provided data going back to 2020. The figures from Forth Valley include autism assessments only, while those for Western Isles are for ADHD only. These data are shown in figure 6 below, which shows that the number of adults waiting for a neurodevelopmental assessment in Forth Valley, Highland, Lothian and the Western Isles increased from 543 to 12,974 between 2020 and 2025 - a total increase of over 2200%. As with the data for children, this is unlikely to be due to such an increase in the number of people with neurodevelopmental conditions, but is likely to reflect an increased awareness of these conditions and the ways they can present.

Waiting times for children and adults

Children

All health boards reported the median and longest current waiting times for children seeking a neurodevelopmental assessment, except for NHS Grampian (which could not provide data specific to neurodevelopmental cases) and NHS Dumfries and Galloway (which provided a longest waiting time only). These are shown in figure 7 below. Median waiting times ranged between 22 weeks (NHS Western Isles) and 141 weeks (NHS Ayrshire and Arran), with an average median waiting time of 76 weeks. Longest waiting times ranged between 69 weeks (NHS Fife) and 342 weeks (NHS Ayrshire and Arran), with an average longest waiting time of 196 weeks.

In some cases, it is claimed that children are waiting on these lists for long enough that by the time they are seen, they are no longer eligible for neurodevelopmental support through these pathways by virtue of having turned 18.

Adults

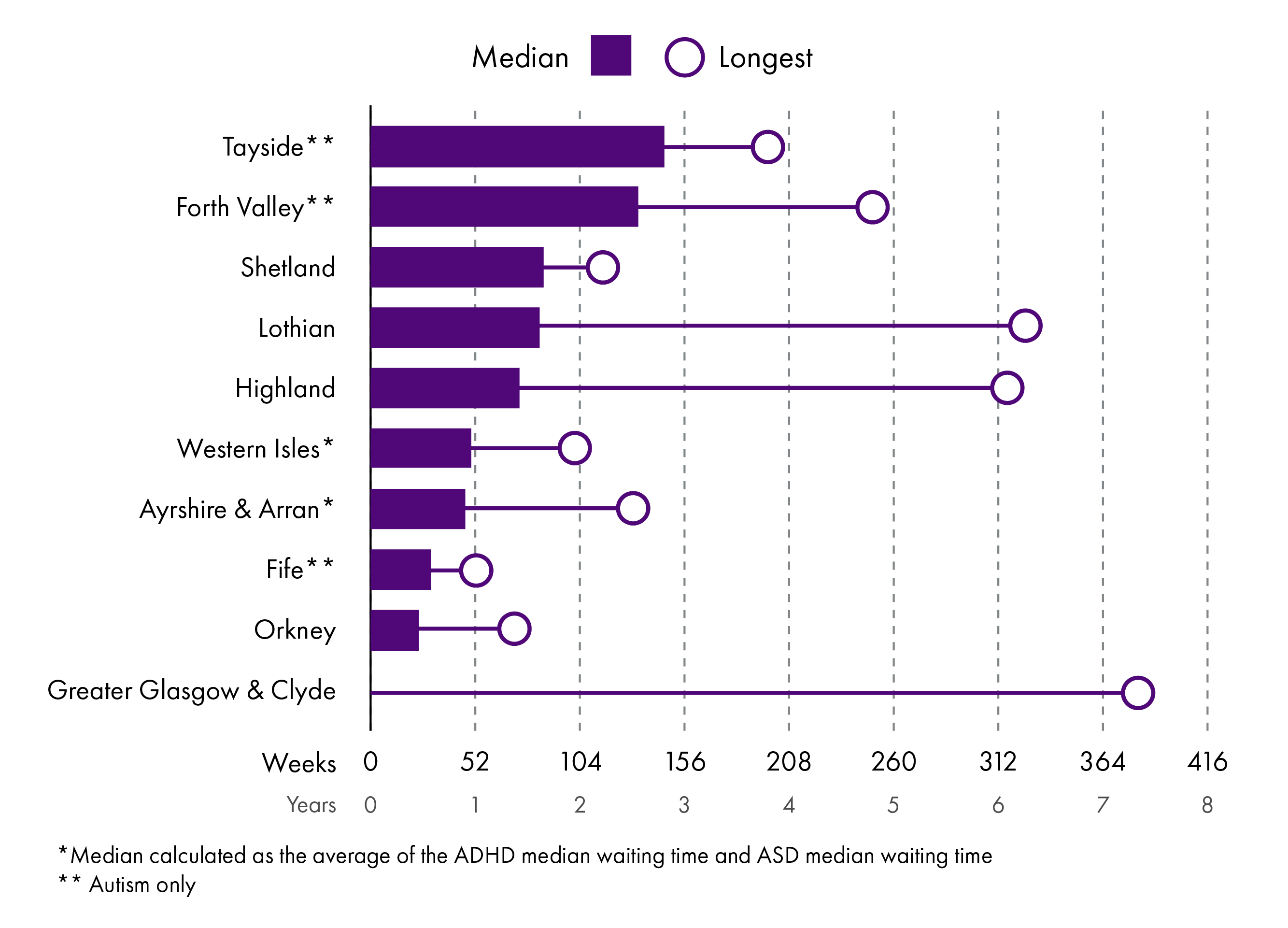

Nine health boards (Lothian, Ayrshire and Arran, Tayside, Forth Valley, Highland, Fife, Shetland, Orkney and Western Isles) reported both the median and longest waiting time for an adult seeking a neurodevelopmental assessment, while Greater Glasgow and Clyde reported the longest waiting time only. Forth Valley, Tayside and Fife reported waiting times for autism assessment only, while the median waiting time for Ayrshire and Arran and Western Isles is the average of the medians for autism and ADHD individually. These are shown in figure 8. Median waiting times ranged between 24 weeks (NHS Orkney) and 146 weeks (NHS Tayside), with an average median waiting time of 76 weeks. Longest waiting times ranged between 61 weeks (NHS Fife) and 390 weeks (NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde), with an average longest waiting time of 182 weeks.

Waiting lists for ADHD medication

If a patient is diagnosed with ADHD, they may be prescribed medication. Six health boards (Ayrshire and Arran, Borders, Forth Valley, Grampian, Lothian and Tayside) operate waiting lists for ADHD medication for children. Five of these (all except for Forth Valley) reported the number of children on the waiting list, and the median and longest waiting times. This is shown in table 1 below.

| Board | Number of children on waiting list | Median waiting time | Longest waiting time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ayrshire and Arran | 114 | 32 weeks | 62 weeks |

| Borders | 4 | 3 weeks | 6 weeks |

| Grampian | 75 | 15 weeks | 22 weeks |

| Lothian | 722 | 72 weeks | 205 weeks |

| Tayside | 257 | Not provided | 148 weeks |

For adults, four health boards reported operating waiting lists for medication, although these were not in operation in all Health and Social Care Partnerships (HSCPs) in some cases. Forth Valley operated a waiting list in Clackmannanshire and Stirling, but not in Falkirk, while Lothian operated waiting lists in East Lothian, Midlothian and Edinburgh City but not in West Lothian. NHS Highland and NHS Orkney operated waiting lists across the whole health board. Waiting list lengths, and median and longest waiting times (where available) are shown in table 2 below:

| Board | Number of adults on waiting list | Median waiting time | Longest waiting time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forth Valley | 24 (Clackmannanshire and Stirling only) | Not provided | Not provided |

| Highland | 174 | 30 weeks | Not provided |

| Lothian | 410 (East Lothian, Midlothian and Edinburgh City only) | 41 weeks | 222 weeks |

| Orkney | 71 | 48 weeks | 112 weeks |

In areas where a waiting list system is not in operation, medication can be prescribed as part of the post-diagnostic service.

Current Policy

This section will start by outlining the current policy provisions for neurodivergent people in Scotland, including a summary of current funding mechanisms to support organisations that work with neurodivergent people. It will then discuss the future of this area in relation to the Scottish Government's proposed Learning Disabilities, Autism and Neurodivergence Bill.

Present and past policy provisions

A number of policy areas have influenced the provision of assessment and support for neurodivergent people in Scotland. This section will outline the key legislative and policy developments relating to neurodivergent people since 1999.

The Equality Act 2010

Equal opportunities is a matter reserved to the UK Parliament, which includes the Equality Act 2010. The Equality Act applies to England, Scotland and Wales.

The Equality Act prohibits discrimination because of a 'protected characteristic' in areas such as employment, education and housing. Disability is one of the nine protected characteristics. It is defined as 'a physical or mental impairment which has a substantial and long-term adverse effect on that person's ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities'. While the Equality Act does not mention autism or neurodivergence explicitly, such conditions may meet the requirements to qualify as a disability under the Act, if they can align their presentations with the definition above. As a result, many autistic and neurodivergent people:

are protected from discrimination, harassment and victimisation

are entitled to 'reasonable adjustments' if they feel they are at a substantial disadvantage compared to someone who is not disabled. This can be in the workplace, in education or when accessing services. Reasonable adjustments may take the form of accessible environments, flexible working hours or additional support during interviews. The employer or service provider must pay for these adjustments.

The public sector equality duty also requires public bodies and organisations carrying out public functions to consider the need to:

eliminate 'discrimination, harassment, victimisation and any other conduct that is prohibited by or under this Act’

‘advance equality of opportunity' and 'foster good relations' between those who have a protected characteristic and those who do not.

This duty applies to public bodies in their role as an employer and as a service provider.

Mental health law and strategies

The Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003, subsequently amended by the Mental Health (Scotland) Act 2015, set out the legal obligation for councils to provide care and support for people with mental disorders. In particular, it established the right of medical professionals to detain and treat patients if they show signs of such mental disorders, but only when the patient poses a significant risk to their own welfare or the welfare of others. Under the Act, mental disorder is defined to include those with learning disabilities, and autism is also included under this definition in practice. However, there is a range of views as to whether mental health law should apply to neurodivergent people, and many neurodivergent people find the classification of autism and other neurodevelopmental conditions as mental health conditions to be stigmatising and offensive.

A number of mental health strategies have also been published by the Scottish Government. The Mental Health Strategy 2017-2027 did not have specific reference to neurodivergent people. Rather, it commissioned a review of whether the 2003 Act adequately fulfilled the needs of autistic people and people with with learning disabilities. This review was scoped in 2017 and addressed in two separate reports.

The Independent Review of Learning Disability and Autism in the Mental Health Act, also known as the Rome Review, was published in December 2019, and addressed the treatment of people with learning disabilities and autism in the Mental Health Act specifically. Among the recommendations of this report were that 'learning disability and autism be removed from the definition of mental disorder in the Mental Health Act' and that 'a new law be created to support access to positive rights'.

The Scottish Mental Health Law Review, published in 2022, carried out a more general review of Mental Health Law in Scotland. Its conclusion was that the framework of any future Mental Health Law 'should apply to all forms of mental or intellectual disability', which includes learning disabilities and autism.

The two reports therefore conflicted on whether mental health law should include autism and learning disabilities. However, the Scottish Mental Health Law Review acknowledged that at the time of its publication, the Scottish Government had committed to taking forward a Learning Disability, Autism and Neurodiversity Bill. This would provide for neurodivergent people specifically, and so follow the recommendation of the Rome Review. However, the Scottish Government broadly agreed with many of the recommendations made by the Scottish Mental Health Law Review as well, and established a new Mental Health and Capacity Reform Programme to implement some of these recommendations.

The updated Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy, published by Scottish Government in 2023, set out an explicit priority to:

strengthen support and care pathways for people requiring neurodevelopmental support, working in partnership with health, social care, education, the third sector and other delivery partners.

Scottish Government, Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy, 2023

The Scottish Strategy for Autism

In 2009, the UK Parliament passed the Autism Act 2009. This requires the UK Government to develop and maintain an Autism Strategy for England. The first of these was published in 2011, with the vision that:

...all adults with autism are able to live fulfilling and rewarding lives within a society that accepts and understands them. They can get a diagnosis and access support if they need it, and they can depend on mainstream public services to treat them fairly as individuals, helping them make the most of their talents.

HM Government, 'Fulfilling and Rewarding Lives': The strategy for adults with autism in England, 2011

The implementation of the Act is being looked at by a House of Lords Select Committee.

Corresponding legislation does not exist in Scotland, but the Scottish Government published a similar Scottish Strategy for Autism in 2011. This was a ten-year plan, with the vision that by 2021:

individuals on the autism spectrum are respected, accepted and valued by their communities and have confidence in services to treat them fairly so that they are able to have meaningful and satisfying lives.

Scottish Government, Scottish Strategy for Autism, 2011

Across the first four years of the plan, £13.4 million was committed by the Scottish Government with the goal of improving the lives of autistic people and their families and carers, and ensuring access to support nationally.

The Strategy was composed of three stages.

The Foundations stage, covering the first two years of the programme. This stage had goals centred around ensuring access. This included access to post-diagnostic services, autism-specific services, and mainstream services where appropriate.

The Whole Life Journey stage, covering the first five years of the programme. This stage considered integrated service provision across a longer timespan to address the multidimensional aspects of autism (such as transition planning, education, health and social care and mainstream services).

The Holistic Personalised Approaches stage, covering the entirety of the ten years. This stage focused on meaningful national-local partnerships, creative use of budgets, and the extension of care and support into older age.

There was a specific focus on the need for local autism strategies, acknowledging that 'the needs of people with autism spectrum disorder and carers [should be] reflected and incorporated within local policies and plans.' Of the £13.4 million pledged between 2011 and 2014, £4.89 million was allocated to individual projects via the Autism Development Fund, and a further £1.12 million was committed to support the development of action plans in local authorities. The Strategy emphasised the need for these strategies to be hosted across multiple agencies (including health, social care, and education), and for those working on them to have the requisite training and knowledge to work with autistic people.

The Strategy was refreshed in 2015 and again in 2018, with additional funding from the Scottish Government of approximately £2.5 million between 2015 and 2021 allocated to individual projects via the Autism Innovation and Development Fund, and the Understanding Autism Fund. The focus was reframed onto four key outcomes.

A Healthy Life: 'Autistic people enjoy the highest attainable standard of living, health and family life and have timely access to diagnostic assessment and integrated support services.'

Choice and Control: 'Autistic people are treated with dignity and respect and services are able to identify their needs and are responsive to meet those needs.'

Independence: 'Autistic people are able to live independently in the community with equal access to all aspects of society. Services have the capacity and awareness to ensure that people are met with recognition and understanding.'

Active Citizenship: 'Autistic people are able to participate in all aspects of community and society by successfully transitioning from school into meaningful educational or employment opportunities.'

Initiatives funded under the Healthy Life strategic outcome included the creation of the National Autism Implementation Team, and the National Post Diagnostic Support Programme. Similarly, the Scottish Women's Autistic Network was established using funding from the Choice and Control strategic outcome.

A review of this phase of the Strategy was conducted in 2021, to mark the end of the ten year programme. It found that:

'most of the commitments in the strategy have been actioned to some extent, some have gained more traction than others and some still need much more focus and investment for real progress to be realised.'

Scottish Government, Scottish Strategy for Autism: evaluation, 2021

However, the review also noted that:

'real change for many autistic people, both in how they engage with services and in how they are supported to live productive lives, is not as evident'.

Scottish Government, Scottish Strategy for Autism: evaluation, 2021

Another review of the Strategy, published by the Cross-Party Group on Autism, also found that there was:

widespread frustration that the aims of the strategy have often not been put into practice or realised at a local level

Cross-Party Group on Autism, The Accountability Gap, 2020

In March 2021, the Scottish Government published a learning/intellectual disability and autism transformation plan, covering 2021-2023. The grouping of autism with learning/intellectual disabilities reflects the high rate of co-occurrence of these conditions, with the plan estimating that over 30% of autistic people also have a learning/intellectual disability. One of the motivators of the new strategy was the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on autistic people and people with learning/intellectual disabilities, particularly in relation to:

mental health

health and social care services

employment

education

digital exclusion

communication.

The plan sets out thirty-two actions to help improve the lives of autistic people and people with learning/intellectual disabilities in these areas. It led to the development of the Learning Disabilities, Autism and Neurodivergence (LDAN) Bill.

National Autism Implementation Team

One of the key outcomes from the final phase of the Scottish Strategy for Autism was the creation of the National Autism Implementation Team (NAIT), a partnership between practitioners and researchers hosted at Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh. The team works to implement evidence-informed practice in the assessment of autism and other neurodevelopmental conditions, and carries out peer-reviewed research in this field. Much of their work involves working with health boards and Health and Social Care Partnerships across Scotland to implement neurodevelopmental services for children and adults. They have also produced an array of resources to assist in the areas of education, inclusive practice, assessment and diagnosis, employment and implementing neurodevelopmental pathways.

One of NAIT's first pieces of work was their National Clinical ADHD Pathway Feasibility Study. This study was commissioned by Scottish Government in order to determine how best to implement a national ADHD pathway. Among its conclusions was the recommendation that:

Scottish Government should endorse the development of adult neurodevelopmental approaches (which would complement children and young people's neurodevelopmental approaches for a coherent national approach to this lifelong condition).

National Autism Implementation Team, National Clinical ADHD Pathway Feasibility Study, 2021

Another key recommendation was that the Scottish Government should endorse a whole-system approach to improving the outcomes for neurodivergent people, including education, employment and the third sector as well as primary, secondary and tertiary care. They also supported the implementation of:

a programme of education, training and research for a) secondary mental health services, b) the multi sector workforce in support of the whole system approach.

National Autism Implementation Team, National Clinical ADHD Pathway Feasibility Study, 2021

NAIT's further work has included the establishment of a children's neurodevelopmental pathway network, set up in 2021. In 2024, they published a guide to the implementation of these pathways across Scotland. They also published an Adult Neurodevelopmental Pathways report in March 2023. This surveyed the provision of neurodevelopmental pathways across the fourteen territorial health boards in Scotland. In this study, NAIT also worked with four 'pathfinder' health board areas (NHS Borders, NHS Lanarkshire, NHS Highland and NHS Fife) and used funding from the Mental Health Recovery and Renewal Fund allocated to those areas to understand the major requirements and barriers to developing adult neurodevelopmental pathways nationally.

The major conclusions drawn from this work are listed below.

Diagnosis is extremely valuable to neurodivergent people. The Adult Pathways report concluded that 'living as a neurodivergent adult without a diagnosis often has a negative impact on mental health and wellbeing and participation in daily life'. However, fundamentally, support should be provided according to need and not diagnosis.

Co-occurrence of neurodevelopmental conditions (such as autism and ADHD) is common, and single condition pathways can lead to wasted resources and longer waiting times for diagnosis and support.

Current provision of adult neurodevelopmental pathways is inadequate. The report found that in 2021, only one of the fourteen Scottish territorial health boards provided both autism and ADHD assessments for adults.

All territorial health boards had child autism and ADHD pathways as of 2021, and either had or were developing overarching neurodevelopmental pathways for children. However, only seven health boards had implemented these pathways as of 2024, and the other seven were still in the process of developing such pathways.

In addition, the report made a set of ten recommendations to improve the provisions for neurodivergent adults in Scotland.

Recommendation 1: An adult neurodevelopmental pathway strategy and planning group to be hosted in all Health and Social Care Partnerships.

Recommendation 2: Support to develop local Neurodevelopmental Pathway action plans.

Recommendation 3: Establish a Neurodiversity Affirming Community of Practice.

Recommendation 4: A focus on ‘Post Diagnostic Support’ or ‘Support before, during and after diagnosis’.

Recommendation 5: Build a Neurodevelopmentally Informed workforce in Scotland.

Recommendation 6: Development of Adult Neurodevelopmental Pathway standards and guidelines for assessment, diagnosis and support.

Recommendation 7: Understand demand and capacity within the system, to meet the needs of neurodivergent adults.

Recommendation 8: Neuroinclusive Further Education and Employment environments.

Recommendation 9: Build a shared expectation that support should be available at any stage for people who identify as neurodivergent.

Recommendation 10: Seek to understand the changes needed to effectively meet the mental health needs of neurodivergent people.

The Scottish Government has since stated that

...we are funding and working with...NAIT to take forward the recommendations of its 2023 report. Support from NAIT is being given directly to health and social care partnerships to develop action plans, introduce adult neurodevelopmental pathways and provide professional learning workshops. We are funding a new neuro-affirming community of practice, which was launched in October 2023, and there has been positive engagement across health boards with that

Minister for Social Care, Mental Wellbeing and Sport, Portfolio Questions, 8 May 2024

NAIT has also published a range of resources for practitioners, which are available on their website.

National Neurodevelopmental Specification for Children and Young People

In 2021, as recommended by the Children and Young Person's Mental Wellbeing Taskforce the Scottish Government published the National Neurodevelopmental Specification for Children and Young People. This document set out the standards of care and service that children and young people with neurodevelopmental requirements should expect to receive in Scotland. This is not limited to health services, and applies to education and community services as well. It also sets out that no diagnosis should be required to access such support. This policy sits alongside the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) NHS Scotland National Service Specification, and aims to enhance the provision for neurodivergent children above and beyond what is set out in the CAMHS specification.

The National Neurodevelopmental Specification lays out seven broad standards of care. These are:

Neurodevelopmental services in Scotland will provide high quality care and support that is right for the patient.

The patient is fully involved in decisions about the patient's care.

The patient will receive high quality assessment, formulation and recommendations that are right for the patient.

The patient's rights are acknowledged, respected and delivered.

The patient is fully involved in planning and agreeing the patient's transitions.

Children, young people and their families and carers are fully involved.

The patient has confidence in the staff that support the patient.

The Specification further breaks down each of these standards into specific sections. No such document exists for adults, although the NAIT have recommended the creation of a corresponding adult neurodevelopmental specification. A review of the implementation of the Specification has been carried out by Scottish Government, and is due to be published in June 2025.

Funding summary

There are a number of funding mechanisms to support neurodivergent people in Scotland.

The Scottish Budget for 2025-26 allocated an additional £270.5 million to mental health services, which will be in addition to spending by individual health boards on mental health services. In 2023-24, a total of £1.5 billion was spent on mental health services, equivalent to 9% of total NHS expenditure.

In the Programme for Government 2025-26, the Scottish Government reiterated a pledge of £123.5 million of recurring funding to improve mental health support for young people, including clearing CAMHS backlogs.

This funding is directed in the first instance to NHS boards, but the mode of delivery of neurodevelopmental pathways varies by area. In some cases, the pathways are hosted within Health and Social Care Partnerships (HSCPs), which are commissioned by the Integrated Joint Boards. This is the case in areas where adult neurodevelopmental pathways are hosted within Community Mental Health Teams (CMHTs), which themselves are part of the HSCPs. On the other hand, in areas where a health board-wide neurodevelopmental pathway exists, this is delivered by the health board directly.

Following the publication of the national neurodevelopmental specification, over £1 million was allocated to five regions (Aberdeen City, East Lothian, Fife, Highland and Stirling) to carry out 'tests of change' designed to explore elements of the specification. A report on this project will be published in the summer of 2025.

In addition, more recent funding totalling almost £250,000 was provided to a number of individual projects aimed at improving support and assessment, including testing of digital assessment tools, and to the Fife and East Lothian 'test of change' sites.

For neurodivergent adults, the Autistic Adult Support Fund allocated £1.5 million from 2023-2025 to fifteen organisations that work with autistic adults in Scotland, and will provide a further £2.5 million in the period 2025-2028. This was a continuation of the National Post-Diagnostic Support Programme that ran from 2020-2023.

The Scottish Government continues to fund the National Autism Implementation Team.

NHS Education for Scotland will receive £648.9 million of funding in 2025-26 and delivers education and training for all people working in NHS Scotland. This includes training of health professionals to diagnose and support people with neurodevelopmental conditions.

Proposed and future policy developments

In addition to existing policies, the Scottish Government has consulted on a new bill to improve the lives of neurodivergent people and people with learning disabilities. This section sets out detail on the proposed Learning Disabilities, Autism and Neurodivergence Bill.

Learning Disabilities, Autism and Neurodivergence Bill

In March 2021, the Scottish Government and Convention of Scottish Local Authorities published the learning/intellectual disability and autism transformation plan. This was in response to the end of the Scottish Strategy for Autism and the Keys to Life strategy, the Scottish Government's strategy to improve the quality of life of people with learning disabilities. The timing of the transformation plan's publication also coincided with increased awareness of the heightened challenges faced by autistic people and people with learning disabilities since the pandemic. These challenges included:

barriers to access to health and social care brought about by the pandemic

deteriorating mental health brought about by isolation due to national lockdowns

digital exclusion

fears of unemployment

lack of support for transitions in education.

The transformation plan set out a list of thirty-two actions, including the consideration of a Commission or Commissioner to help protect people's rights. In response to these proposed actions and extensive campaigning by third sector organisations, the Scottish Government conducted scoping work for the Learning Disabilities, Autism and Neurodivergence (LDAN) Bill in 2022. It was anticipated that this Bill would provide a broad approach to covering learning disabilities and neurodivergence, following on from previous strategies on a national level. It was also the intention of this Bill to broaden these provisions to cover all neurodivergent people, on both a local and national scale. Following the scoping paper, further goals were set out, including to improve awareness and understanding of these conditions, deliver better training, increase the use of inclusive communication, better collect and report data on these groups, and promote independent advocacy.

The scoping phase for this proposed Bill engaged with 18 different organisations across 30 events, and the findings were published in 2023. The key takeaways included the following:

Participants felt that such a bill was needed to primarily address the discrimination facing people with learning disabilities, autism and neurodivergent presentations, and protect them from such discrimination. This should be done through education and training, both for public bodies and for neurodivergent people themselves.

They also felt that the bill should cover a wide range of people, and the definition of what makes a person neurodivergent needed to be made more clear and formal.

There was consensus that any bill should cover people without a formal diagnosis of learning difficulties, autism, or any other neurodevelopmental condition, and that the bill should cover the full range of neurodivergent presentations. However, some participants were concerned that too broad a scope would not effectively target the needs of any individual or group.

The length of waiting times for diagnosis was an issue of major importance.

The next stage in the development of the Bill was consultation, which took place in December 2023-April 2024. The Lived Experience Advisory Panel (LEAP), a group of approximately twenty-five people with conditions such as learning disabilities, autism, ADHD, dyslexia and Down's syndrome, helped to co-design the consultation. Feedback from the consultation was collected and analysed in order to inform the next stages of the Bill's progression. The issue of diagnosis was not included in the consultation.

However, in September 2024, the Minister for Social Care, Mental Wellbeing and Sport announced that the Scottish Government was not planning introduce the LDAN Bill in the parliamentary year 2024-2025. Instead, it intended to develop and publish draft bill provisions, taking on board the feedback from the consultation analysis. The announcement cited three reasons for this delay.

There were 'strong and diverse views' expressed in the consultation analysis on many of the key issues, which the Scottish Government would need to work through before going forward.

There was a need to wait for the results of the Scottish Parliament's inquiry into the Commissioner Landscape in Scotland before proceeding. The report on this inquiry was published in September 2024, and called for a pause on creating any new Commissioner roles until a 'root and branch review' of the existing Commissioner structure is carried out. This would include the creation of any Commissioner via the LDAN Bill. A dedicated committee was subsequently set up to explore the issue further and reported in June 2025. This Committee recommended that no new advocacy-type SPCB supported bodies should be created and set out new criteria for the creation of any new Commissioners.

The legislative landscape in this areas was fast-changing, with the National Care Service (Scotland) Bill (now the Care Reform (Scotland) Bill) and Human Rights Bill both under consideration. However, the National Care Service Bill encountered delays in the parliamentary year 2024-2025 and the scope changed considerably during scrutiny before its approval in June 2025. The Human Rights Bill has also been pushed back a number of times and will no longer be taken forward in the current parliamentary session.

The Equalities, Human Rights and Civil Justice Committee held two evidence sessions on the delay, on 26 November 2024 and 3 December 2024, and also undertook engagement with six autistic disabled people's organisations on 25 March 2025.

Current provision of neurodevelopmental pathways in Scotland

This section outlines the current neurodevelopmental pathways available to adults and children in Scotland. It begins by outlining the key stages of the pathway, from the point of initial contact to the sharing of the diagnosis with the patient. It then goes into the detail of how the process works in each NHS board, and what support and services are available in each area. It finishes with a summary of other support and provision for neurodivergent people, including in social security, social care, education, employment and through the third sector.

Neurodevelopmental pathways for children and adults by health board

The delivery of neurodevelopmental pathways in Scotland is managed by the NHS territorial health boards and the Health and Social Care Partnerships (HSCPs). In particular, the pathways for children should be embedded within the Getting It Right For Every Child (GIRFEC) framework. The exact mode of delivery varies by health board, but the pathways can be divided broadly into the following stages, according to the National Autism Implementation Team (NAIT) and Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) guidelines.

Identification of needs. Once a family member, teacher, GP or the neurodivergent person themself decides that a neurodevelopmental assessment might be useful, they should be offered a first, pre-referral appointment as soon as possible. The National Neurodevelopmental Specification states that this should be within four weeks at most for a child or young person.

Pre-referral appointment. This is usually done by schools, health visitors, allied health professionals or GPs, and determines whether a formal neurodevelopmental assessment is necessary. In these appointments, patients may be screened using questionnaires about their behaviour and family history. NAIT has compiled a list of suitable questionnaires and tools, which include the ESSENCE-Q and DAWBA, that can be administered by a range of people including parents and carers. One pilot study in Lanarkshire suggested that moving towards a model in which these tools are used more widely and earlier in the neurodevelopmental pathway could significantly reduce waiting times and pressures on assessment teams. If the team carrying out this appointment decides that a neurodevelopmental assessment is necessary, they refer the patient to the assessment service. However, if the patient meets the criteria for referral to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) or adult mental health services due to a co-occurring mental health condition, they are referred to these services instead. In some areas (such as NHS Highland, where the children's neurodevelopmental service operates on an open referral system) not all patients are offered a pre-referral appointment.

Triage and allocation. Once the assessment team receives a referral, they check that the referral meets the criteria and put the patient on the waiting list for an appointment. NAIT propose that the time between referral and first appointment should be no longer than 84 days/12 weeks. NAIT also makes a distinction between 'core' cases, for which the local multi-disciplinary team can complete the assessment in 1-2 appointments, and 'complex' cases which require the attention of a specialist team and may take longer to complete. NAIT have published a guide to complexity in neurodevelopmental assessments that covers this issue in more detail.

Assessment appointment(s). The formal assessment process can take many appointments, depending on the complexity of the case. In general, these consist of two key components. The first is information gathering through interview-style discussions with the patient and their family. The second is direct observation of the patient and their behaviours, sometimes in a range of environments. For example, where a child presents differently at school as opposed to at home, it can be appropriate to arrange in-school and at-home observations. Specialist multi-disciplinary assessment teams carry out these observations and discussions.

Diagnosis. Once the multi-disciplinary team has gathered the relevant information, the assessment team will reach a judgement as to the diagnosis of the patient. This is done against a standard set of criteria, such as the DSM-5 or ICD-11. Patients may be diagnosed with one or more neurodevelopmental conditions, or none at all. The team making the assessment may also diagnose co-occurring mental health conditions.

Sharing the diagnosis. Finally, the team shared the diagnosis with the patient, their family and other groups (such as the school, GP, or social care services). The patient may be signposted to further post-diagnostic support, either within the NHS or via the third sector.

More information about the various methods and tools used in the pathway can be found in NAIT's Children's Neurodevelopmental Pathway Practice Framework and Adult Neurodevelopmental Assessment Workbook.

The provision of these services varies between the NHS Scotland territorial health boards. Services such as Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) and Community Mental Health Teams (CMHTs) may be involved, but some health boards have separate neurodevelopmental assessment teams. Table 3 below summarises the information available about neurodevelopmental pathways online, as well as the responses to the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee's letter of March 2025. This may not reflect the full range of services available in each health board. Detailed information about the neurodevelopmental pathways for children and adults in each health board is provided in Annex A.

| Health Board | Child Neurodevelopmental Pathway | Adult Neurodevelopmental Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| NHS Grampian | Neurodevelopmental assessments available through CAMHS (for those meeting criteria) or Community Child Health (Paediatrics). | Adult Autism Assessment team in operation in Moray and Aberdeen City HSCP, but no longer in Aberdeenshire HSCP. This is an autism assessment service only, with plans to move to a broader neurodevelopmental service. A small ADHD assessment team exists in Aberdeen City HSCP. |

| NHS Tayside | As of March 2025, was not accepting new referrals for neurodevelopmental assessments unless the patient had a co-occurring mental health condition and met the criteria for referral to CAMHS. | ADHD referrals made to Community Mental Health Teams but must meet the criteria for referral to secondary mental health services. Tayside Adult Autism Consultancy Team carries out adult autism assessments. |

| NHS Highland | Neurodevelopmental assessments carried out by a Neurodevelopmental Assessment Service (NDAS). | There are separate adult autism and ADHD pathways. Adults do not need to meet the criteria for referral to secondary mental health services to access these. ADHD pathway was not taking new referrals as of October 2023 unless the patient met the criteria for referral to secondary mental health services. |

| NHS Orkney | Neurodevelopmental service exists outside CAMHS, although no information is available about how the pathway works. | Assessments outsourced to a private healthcare provider, although a neurodevelopmental service is under development. |

| NHS Shetland | Assessments available through CAMHS, Community Paediatrics and Speech and Language Therapy services. Patients do not need to meet the criteria for referral to CAMHS to access these services. | Adult Autism Assessment Pathway is managed by Speech and Language Therapy services, currently paused due to funding issues. |

| NHS Western Isles | Overarching neurodevelopmental assessment is available. | Neurodevelopmental service is available, although ADHD assessment not yet incorporated. |

| NHS Lothian | Neurodevelopmental pathway exists in all HSCPs, although mode of delivery varies between individual HSCPs. | Overarching neurodevelopmental pathway within the Community Mental Health Teams. Patients do not need to meet criteria for referral to secondary mental health services to access this. |

| NHS Forth Valley | Neurodevelopmental assessments available through CAMHS or Paediatric Neurodevelopmental Services. | The Adult Autism Assessment Team, which carried out assessments for those who do not meet the criteria for referral to secondary mental health services, was disbanded in March 2025. |

| NHS Borders | There is an overarching neurodevelopmental assessment service (Borders Autism Team) hosted within CAMHS that is available even if patients do not meet the national criteria for referral to CAMHS. | No service available for those seeking diagnosis who do not meet the criteria for referral to secondary mental health services. |

| NHS Fife | Overarching neurodevelopmental assessment is available through the Fife Neurodevelopmental Pathway. | Neurodevelopmental assessments are only available for those that meet the criteria for secondary mental health services. |

| NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde | Overarching neurodevelopmental assessment is available for children who do not meet the criteria for referral to CAMHS. | The Adult Autism Team (AAT) operates within the Community Mental Health Teams, and provides autism assessments for adults who do not meet the criteria for referral to secondary mental health services. ADHD assessments are carried out within each of the six HSCPs. |

| NHS Lanarkshire | Neurodevelopmental assessments come through the NHS Lanarkshire Neurodevelopmental Service, or through CAMHS if the patient meets the referral criteria. | There is a recently established Adult Neurodevelopmental Service, which provides autism assessments to all adults. Unclear whether an adult ADHD pathway exists. |

| NHS Dumfries and Galloway | NHS Dumfries and Galloway operate a Neurodevelopmental Assessment Service for Children and Young People (NDAS) with an open referral system. | No adult neurodevelopmental pathway for those who do not meet the criteria for referral to secondary mental health services. |

| NHS Ayrshire and Arran | Neurodevelopmental assessments are available to those meeting CAMHS or community paediatrics referral criteria only. | No operational pathway for adult neurodevelopmental assessments, and no longer accept referrals. |

Referral to CAMHS or adult mental health services

Specialist neurodevelopmental pathways are not the only route for neurodivergent people to be assessed for neurodevelopmental conditions. If a child meets the criteria for referral to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS), they should be accepted into this service rather than be referred to a neurodevelopmental pathway. CAMHS are for

children and young people age 0 – 18th birthday with clear symptoms of mental ill health which place them or others at risk and/or are having a significant and persistent impact on day-to-day functioning.

Scottish Government, Child And Adolescent Mental Health Services: National Service Specification, 2020

These criteria mean that neurodivergent children with co-occurring mental health conditions should be seen within CAMHS. Specialist CAMHS units routinely carry out neurodevelopmental assessments, and these assessments form part of the broader mental health care services the patient receives. However, these services are not accessible to the majority of children seeking a neurodevelopmental assessment. The children's neurodevelopmental pathways surveyed in the following sections are specifically for children who do not meet the CAMHS referral criteria, and mostly exist outside CAMHS. There is very limited data about the number of children referred within CAMHS, and how long they wait for an assessment.

Similarly, adults with co-occurring mental health conditions will often meet the conditions for referral to secondary mental health care services. In most areas, Community Mental Health Teams (CMHTs) deliver these services. There is no nationally standardised set of criteria for referral to CMHTs. Instead, these are set locally within each NHS board. For example, in NHS Highland the Adult CMHT will consider referrals from primary, secondary and tertiary care of

people presenting with mental disorder of significant clinical severity and complexity associated with significant risk and/or significant functional impairment.

NHS Highland, Community Mental Health Team (CMHT) (Guidelines), 2025

As with the CAMHS criteria, this excludes many of the people seeking a neurodevelopmental assessment, who do not have a co-occurring mental health condition. NHS Highland note explicitly that:

The Adult CMHT cannot provide assessment for new diagnosis of Autistic Spectrum Disorder in the absence of comorbid moderate to severe mental illness / disorder.

NHS Highland, Community Mental Health Team (CMHT) (Guidelines), 2025

As a result, the adult neurodevelopmental pathways surveyed in the following sections are specifically for adults who do not meet the CMHT referral criteria, and mostly exist outside the CMHTs.

Private neurodevelopmental assessment

Due to the long waiting times for neurodevelopmental assessments, there is an increasing demand for private neurodevelopmental assessments for both adults and children. The closure of assessment services in some health boards has led to even more neurodivergent people seeking a private assessment. These are available through a number of organisations in Scotland, and are regulated through Healthcare Improvement Scotland. The main advantage of such assessments is that waiting times are often much shorter. Quantitative data on waiting times is scarce, but one clinic in England that provides both private assessments and assessments on behalf of the NHS suggests waiting times for private assessment can be as little as 8 weeks, while those funded by the NHS take 9-18 months.

Private neurodevelopmental assessments in Scotland cost in the range £1500-£450012345, although costs are slightly lower for condition-specific assessments (e.g. those assessing for ADHD or autism only)6. Many neurodivergent people report that the cost of private assessment causes them to incur significant financial hardship5.

If they meet NHS gold standards, private diagnoses for neurodevelopmental conditions may be accepted as equivalent to an NHS diagnosis. However, the decision to accept such diagnoses lies with the GP. In the case of ADHD, where diagnosis may lead to the prescription of medicines, the patient may wish to enter a shared care agreement, under which the medication may be prescribed by the NHS GP, rather than the private specialist. Whether or not the GP agrees to this arrangement depends on a number of factors including specific health board guidance, quality of diagnosis, the nature of any other medication the patient may be taking, and the GP's own workload. Guidance for such agreements has been issued by the General Medical Council, the Scottish Government and some health boards.Shared care agreements are discussed in more detail in the issues section.

Other support available

A crucial aspect of the experience of neurodivergent people is the support available outside the NHS. A range of support is available for those who have not yet obtained a diagnosis (or are not seeking one), although the provision of this support is highly variable across Scotland. Given the increasing demand for neurodevelopmental support, this is more important than ever. Even for those who have received a diagnosis, support outside the NHS is critical, as post-diagnostic support from NHS services is minimal in some areas. In this section, we will look at support that does not require a formal diagnosis to access.

Therapies

One of the services that does not always require a formal diagnosis to access is therapy. This can include occupational therapy, speech and language therapy and cognitive-behavioural therapy.

Occupational Therapists (OTs) help people overcome physical and mental challenges related to completing everyday tasks. These tasks could be learning activities, leisure activities, or simply the day-to-day process of looking after oneself. They also have an important role in implementing and supporting environmental modifications to make the neurodivergent person more comfortable across a range of settings. This can be at home, in education or in employment. OTs also support the people around a neurodivergent person to understand and adapt to their communication and sensory preferences.

This sort of therapy can be invaluable in helping neurodivergent children and adults. One study found that occupational therapy 'significantly improves sensory skills, relationship-building abilities, body and object usage, language skills and social and self-care skills' in autistic children1, and another concluded that 'occupational therapists have much to offer in providing interventions for adults with ADHD'2. All fourteen NHS boards in Scotland have occupational therapy services for both children and adults, and occupational therapists in Scotland are supported by organisation such as the Royal College of Occupational Therapists.

Speech and Language Therapists (SLTs) work with neurodivergent people in a similar way to improve their verbal, non-verbal and social communication. Autistic people in particular often struggle with speech, and evidence has shown that speech and language therapy is a highly effective method of helping autistic children to improve their communication3. As with occupational therapy, speech and language therapy is available from all NHS boards in Scotland, and private services are also available4.

Guidance suggests that OTs and SLTs should also be core members of the multi-disciplinary teams that carry out neurodevelopmental assessments, and there have been calls for this role to be expanded.

Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) is another tool that can help neurodivergent people learn how their feelings, emotions and thoughts influence each other. It teaches coping skills to deal with difficult and unfamiliar thoughts that neurodivergent people may have. If successful, it can improve the focus and social skills of neurodivergent people in various situations56. However, other research suggests that some neurodivergent people see CBT as unhelpful and damaging7, as it encourages masking of behaviours and doesn't fall within the neuro-affirming paradigm. CBT is less widely available through the NHS in Scotland than SLT and OT, but there are many third sector and private organisations offering these services.

As with neurodevelopmental assessment services, there is a high demand for these services in Scotland. While advice and support is available over the phone in some health boards, waiting times for accessing specialised individual support can be months or years in some cases. Referrals can be made by GPs, schools and health visitors, but self-referrals are also accepted.

Third sector support