Scotland's exports - policy and statistics

This briefing gives an overview of the latest data and the different sources covering Scotland's exports, the recent international context including EU exit, the Covid-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and relevant Scottish Government policy which aims to encourage exports. The briefing also includes a number of case studies.

Key points

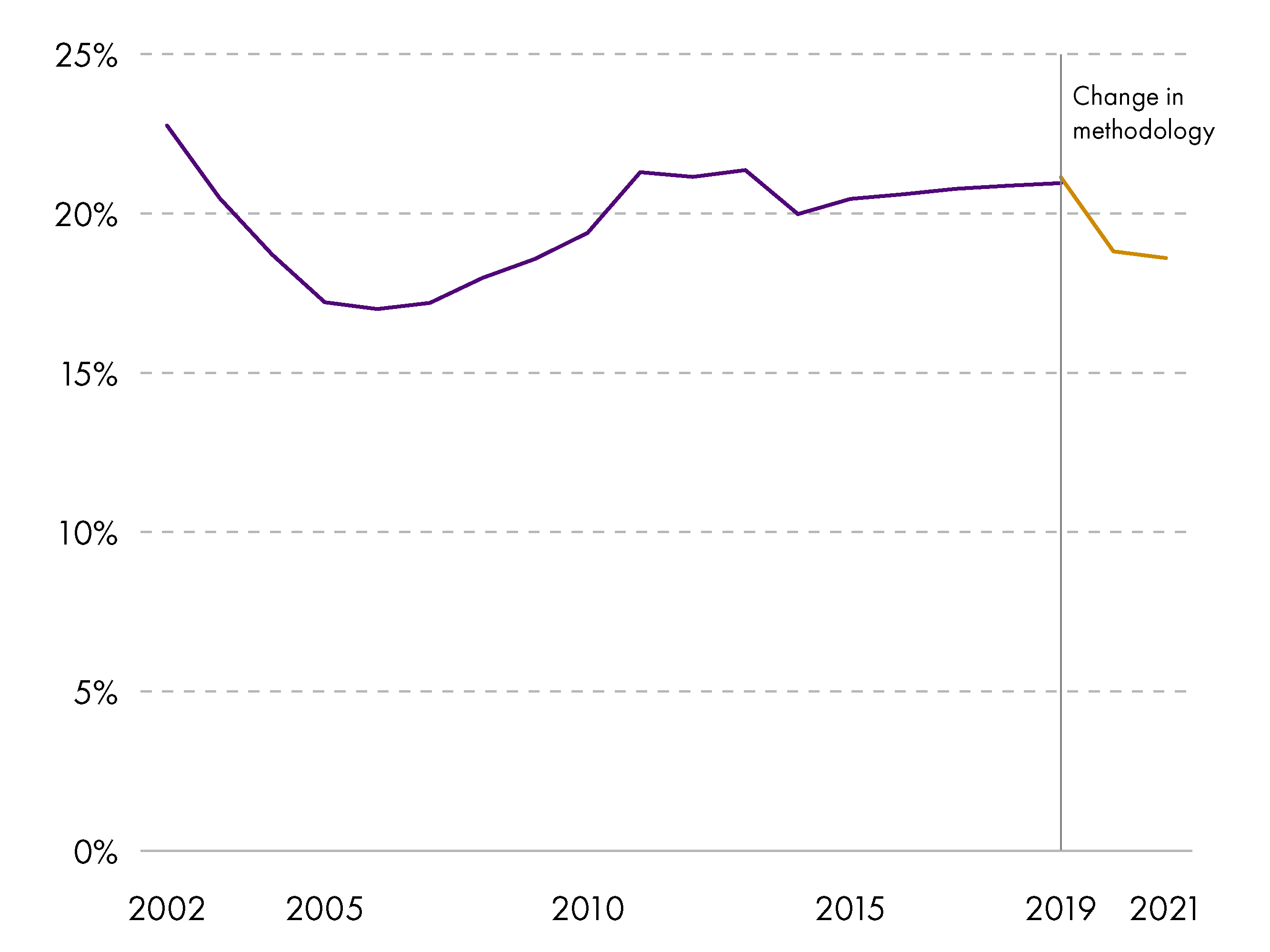

The Scottish Government export growth strategy 'A Trading Nation' has the headline goal of increasing the value of Scotland's international exports from the equivalent of 20% of Scottish GDP to 25% by 2028, but since the strategy was launched in 2019 there has been considerable disruption to international trade through political changes such as the UK's exit from the EU, the impact of the COVID 19 pandemic and geopolitical events such as the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Since 2019, the value of Scotland's exports compared to GDP have followed a downward trend and in 2021 were below the equivalent of 20% of Scottish GDP.

There are two key sources of data which have informed this briefing :

Exports Statistics Scotland (ESS) published by the Scottish Government provides annual data on the value of exports from Scotland to the rest of the UK and internationally. It bases its analysis on the sale of goods and services to customers outside Scotland. The analysis is based on economic activity of the business.

Regional Trade Statistics published by HMRC provides quarterly data on the value and mass of international exports from the UK, broken down by nation and region.

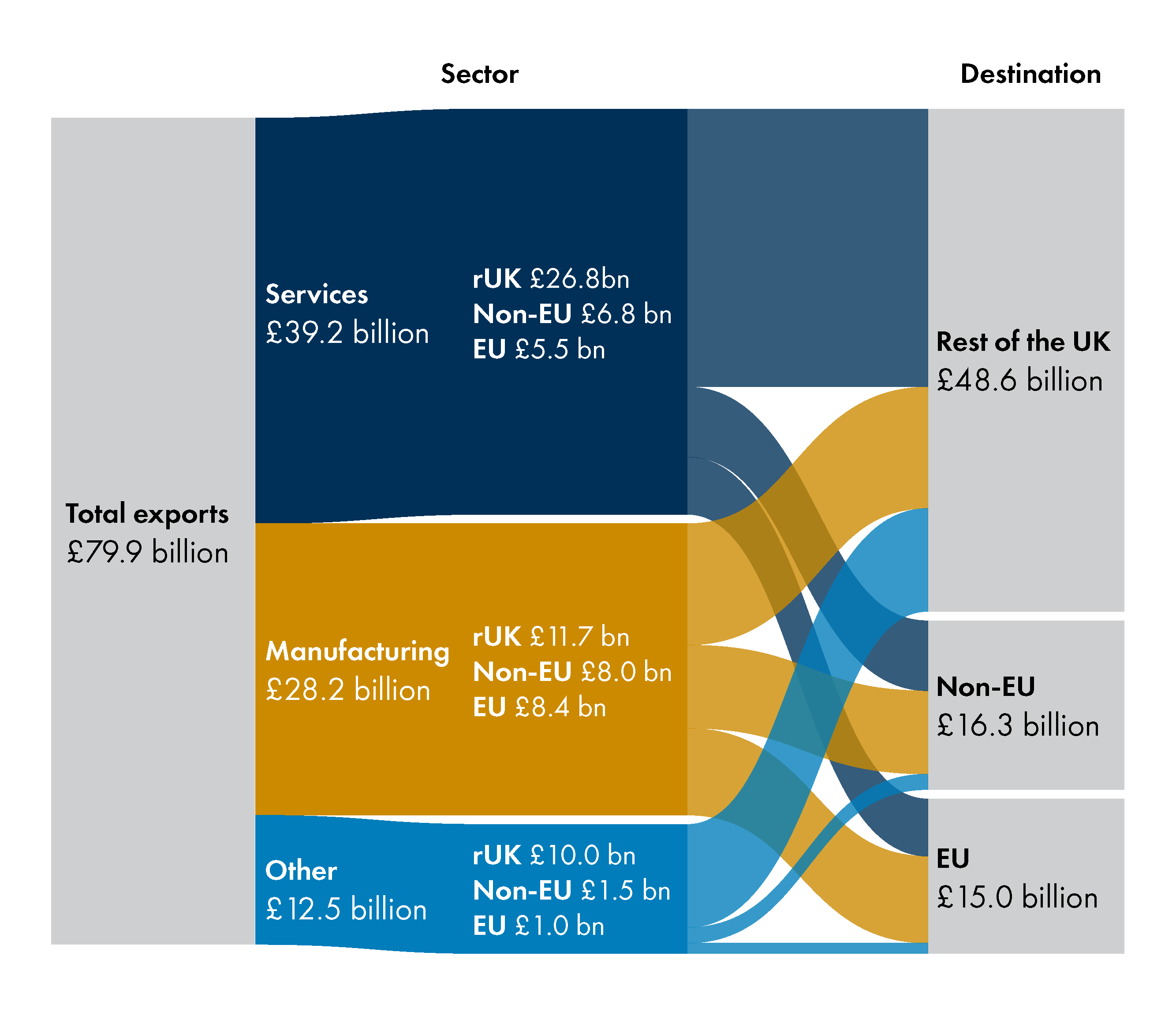

Overall the rest of the UK (rUK) is the main exports destination for Scotland. However, while 69% of Services exports go to rUK, only 42% of the value of manufacturing exports goes to the rest of the UK.

Export Statistics Scotland figures show that in 2021 the value of exports was £80 billion, which is a fall of £2.2 billion (2.6%) compared to 2019. The fall in the value of exports since 2019 was not uniform; exports to the EU reduced by £2 billion (-11.7%), to the rest of the world by £2.1 billion (-11.2%), but exports to the rUK grew by £1.9 billion (4%).

Exports of services were worth a total of £39 billion in 2021. Unlike manufacturing, these are predominately to the rest of the UK which accounted for 69% of service exports in 2021. Service exports to all destinations declined between 2019 and 2021; to the rUK by £0.8 billion (-3%), to the EU by £0.6 billion (-9.7%) and to the rest of the world by £1.5 billion (-18.1%).

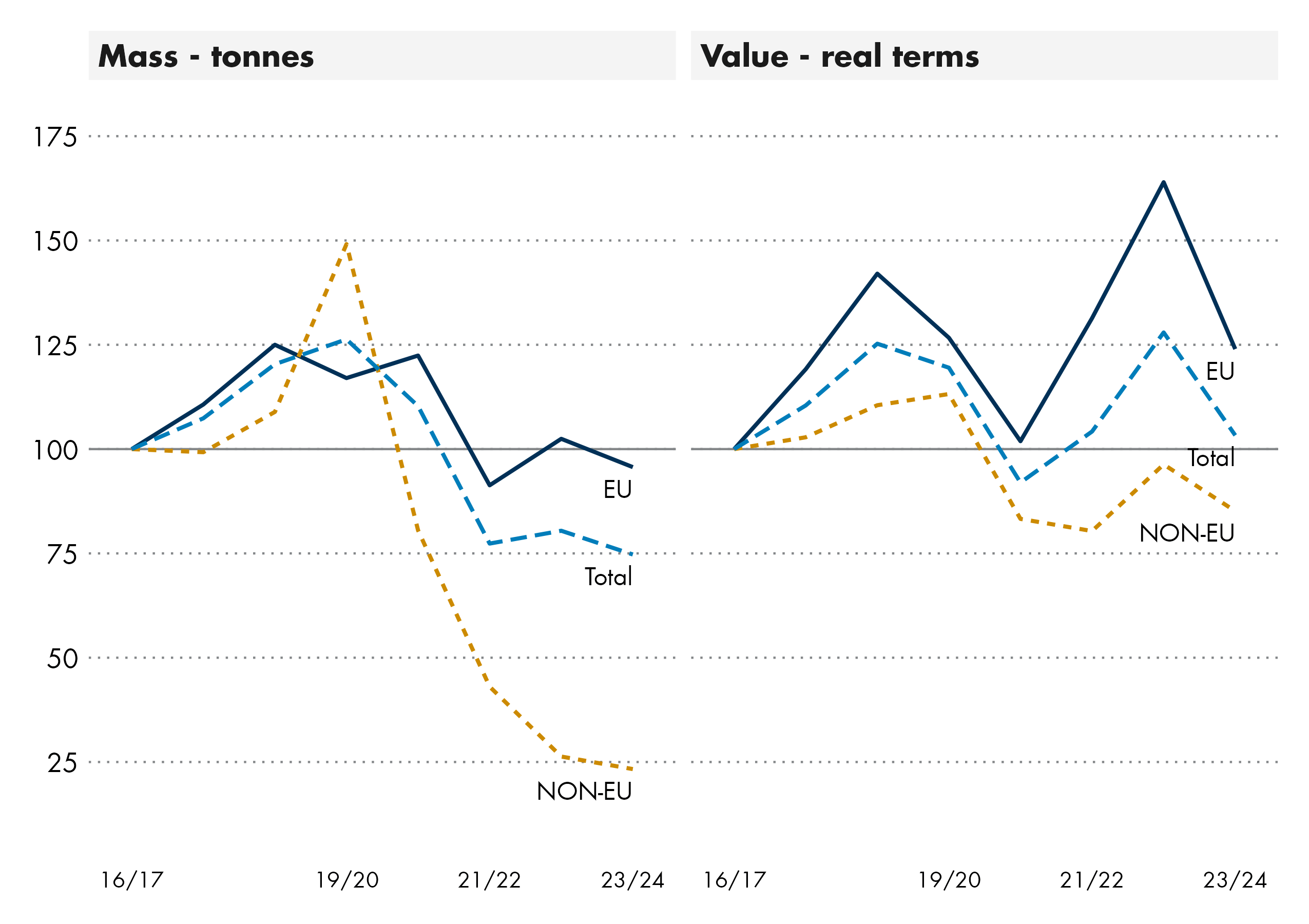

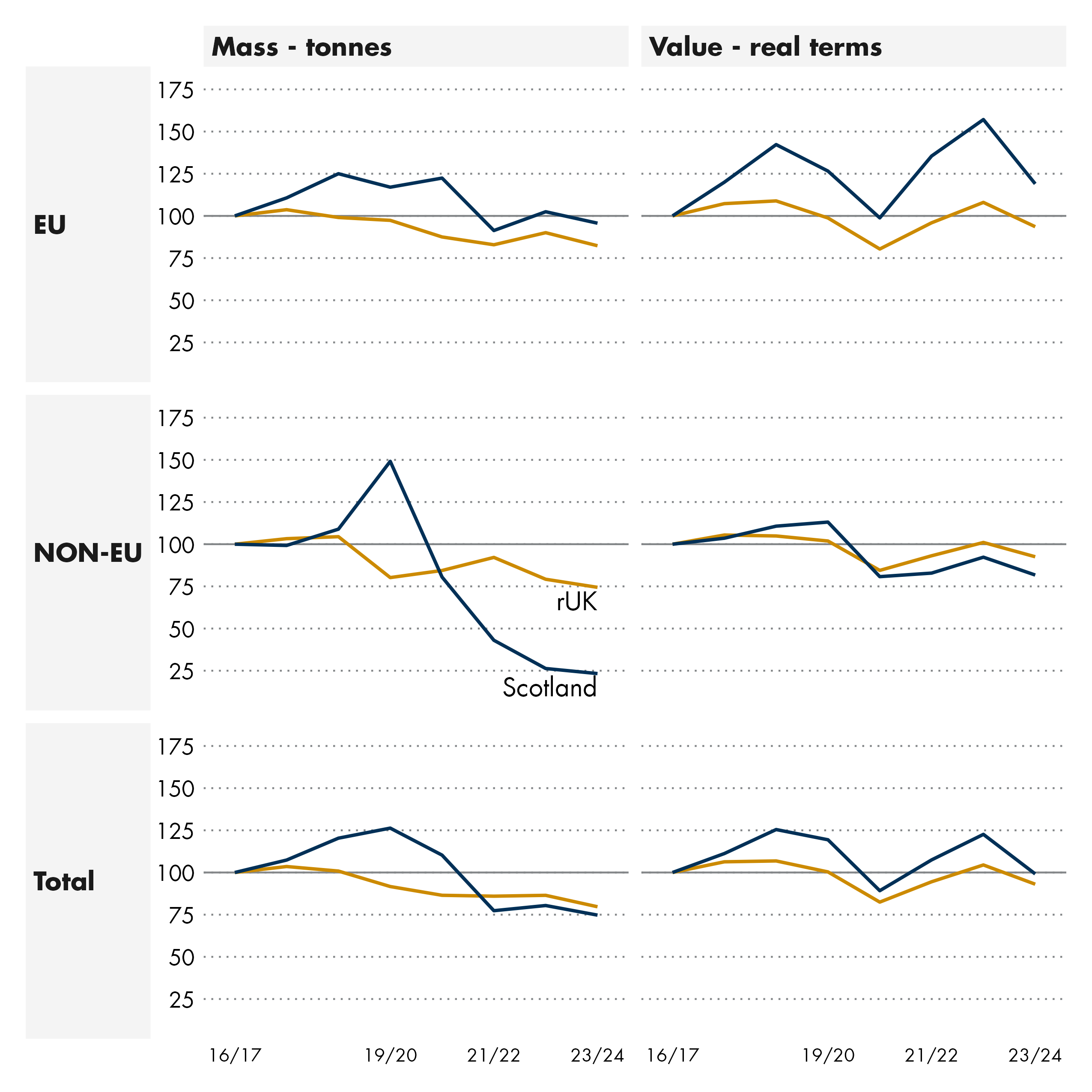

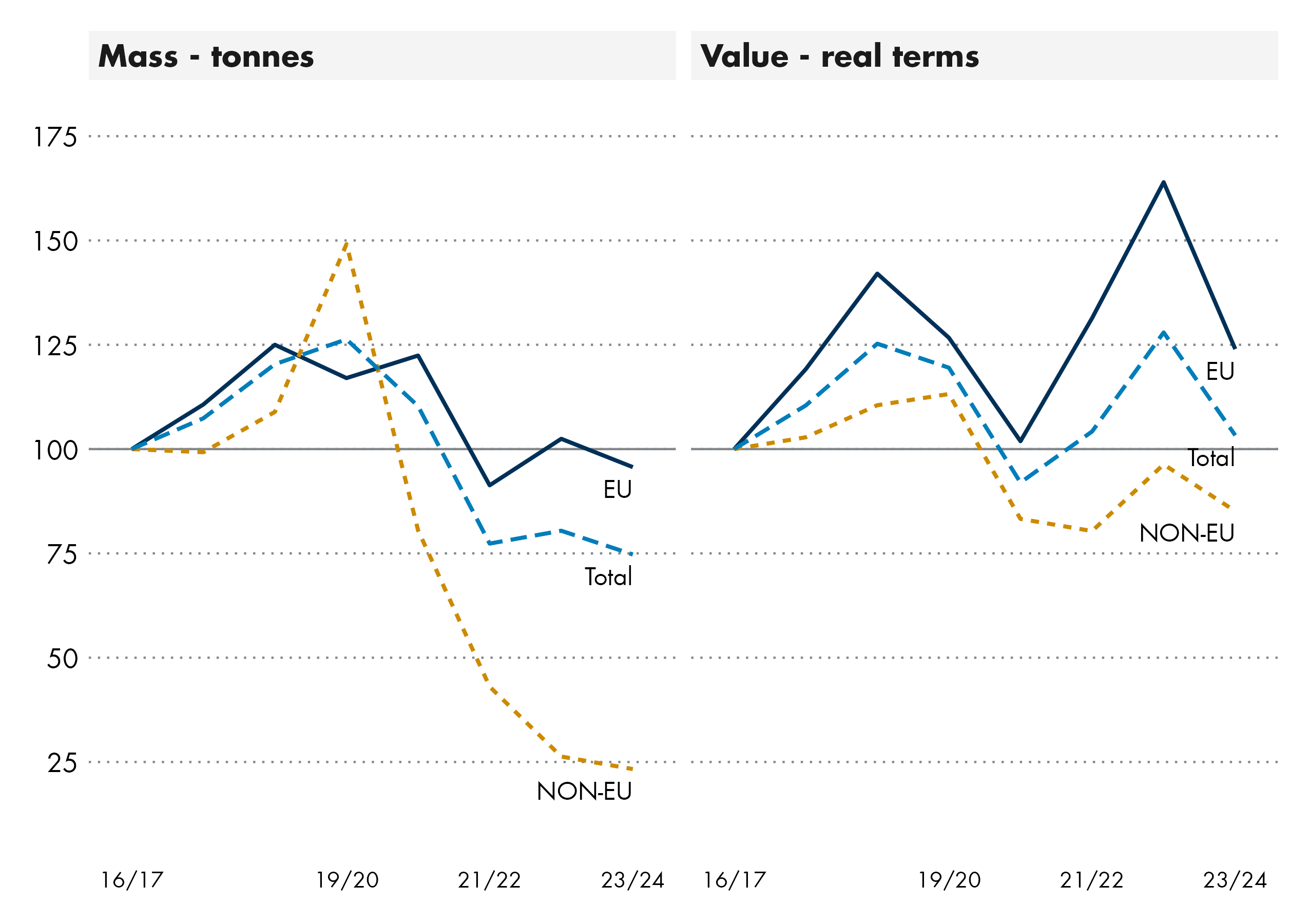

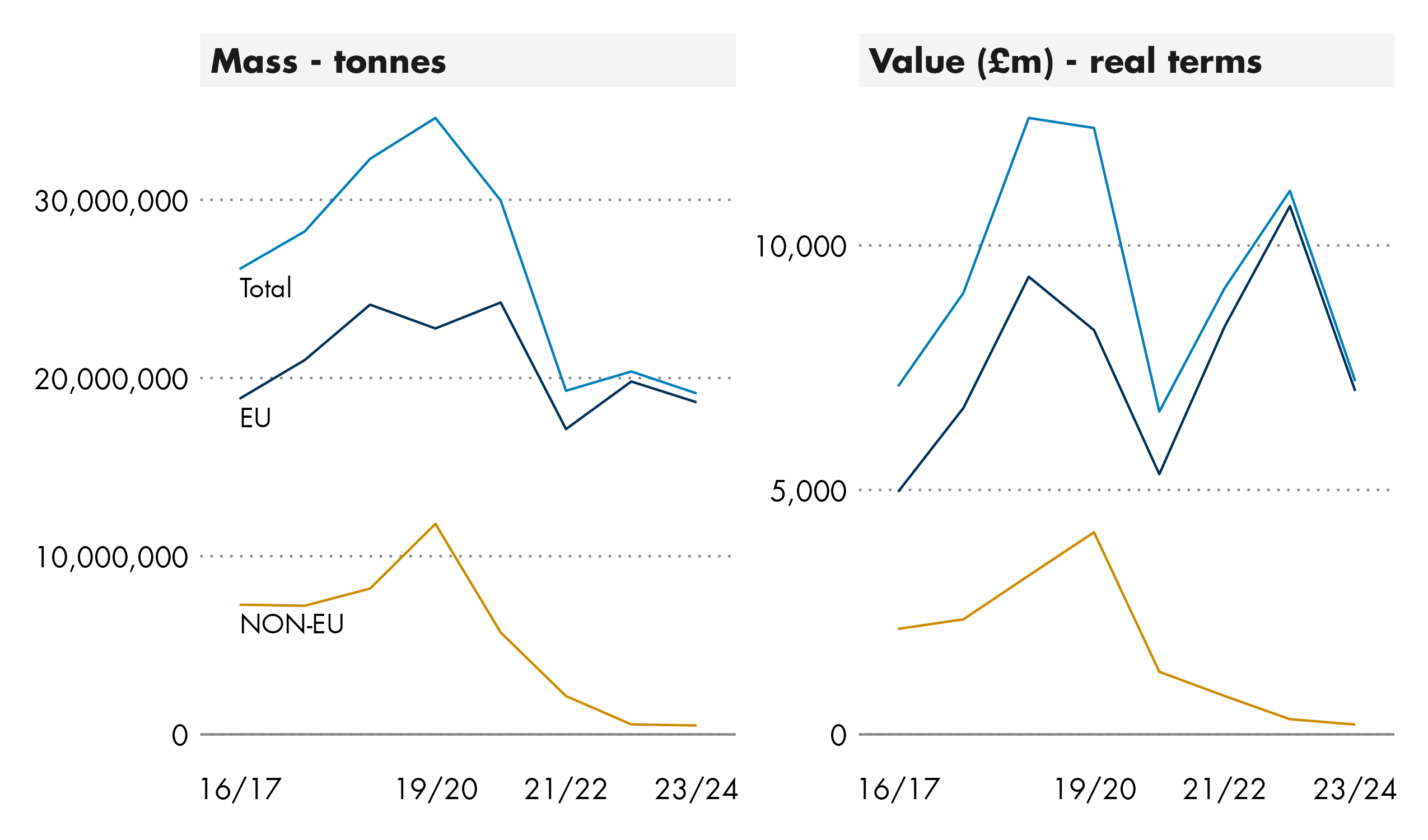

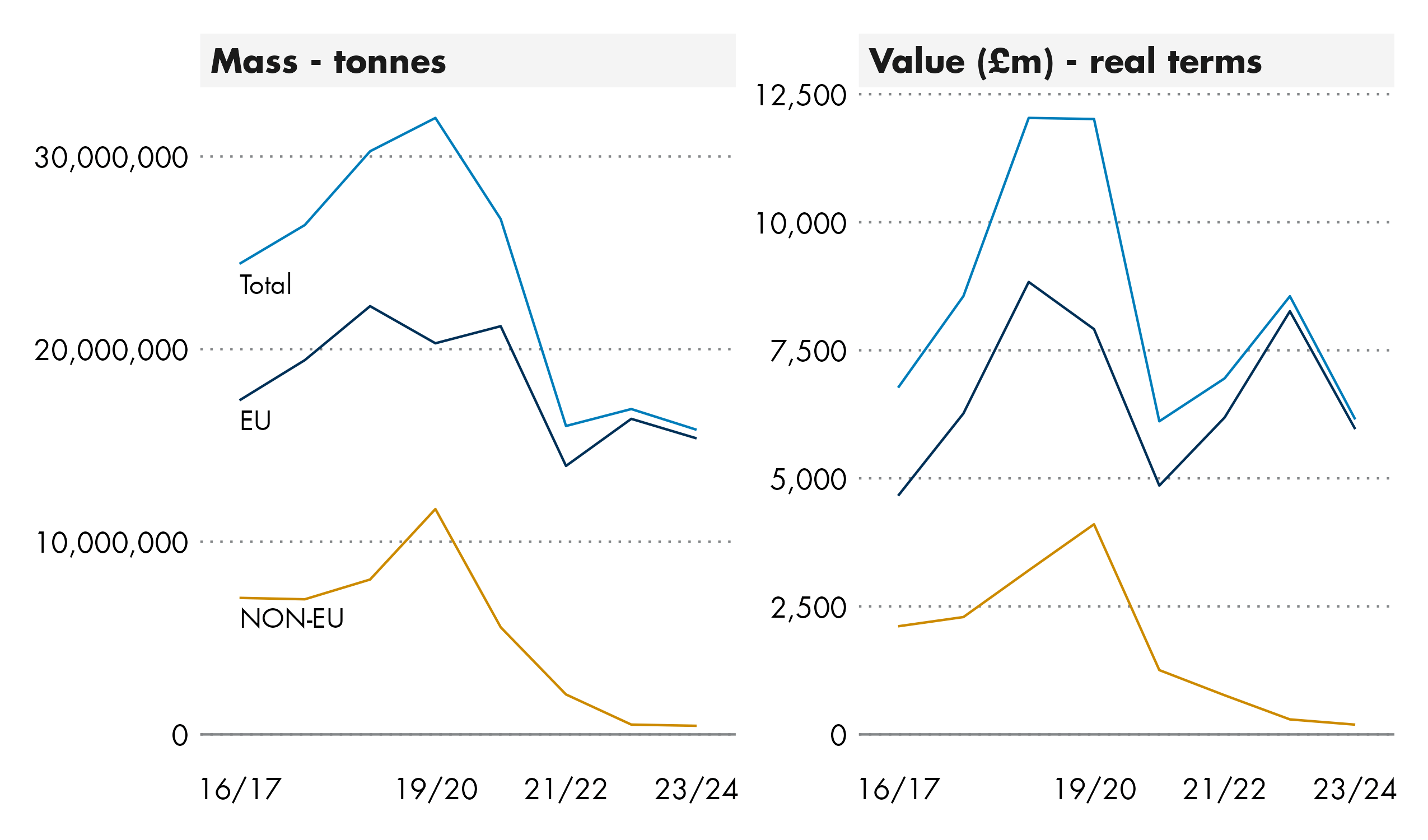

Regional Trade Statistics data illustrates that the mass of exports from Scotland peaked in 2019/20. By 2023/24 the total mass of Scottish exports had reduced by 41% compared with 2019-20, with non-EU exports reducing by 84% and EU exports reducing by 18%.

The value of Scottish international goods exports peaked in 2022/23, with total exports worth £37.3 billion, up from £25.7 billion in 2016/17, representing an increase of 45%. However, when adjusted for inflation, this is an increase of 23%.

Exports to the EU have increased in real terms by 19% between 2016/17 and 2023/24, however they fell by a quarter between 2022/23 and 2023/24 and are now around 2017/18 levels. Exports to non-EU destinations have fallen by 18% in real terms between 2016/17 and 2023/24, with the real term value remaining between £11 and 12.5 billion since 2019/20.

While responsibility for negotiating international agreements, including trade deals, is reserved, the Scottish Government has a number of strategies which aim to support firms exporting. These include A Trading Nation which focused resources on countries and sectors which it stated were most likely to deliver the largest, most sustainable contributions to Scotland's economic growth.

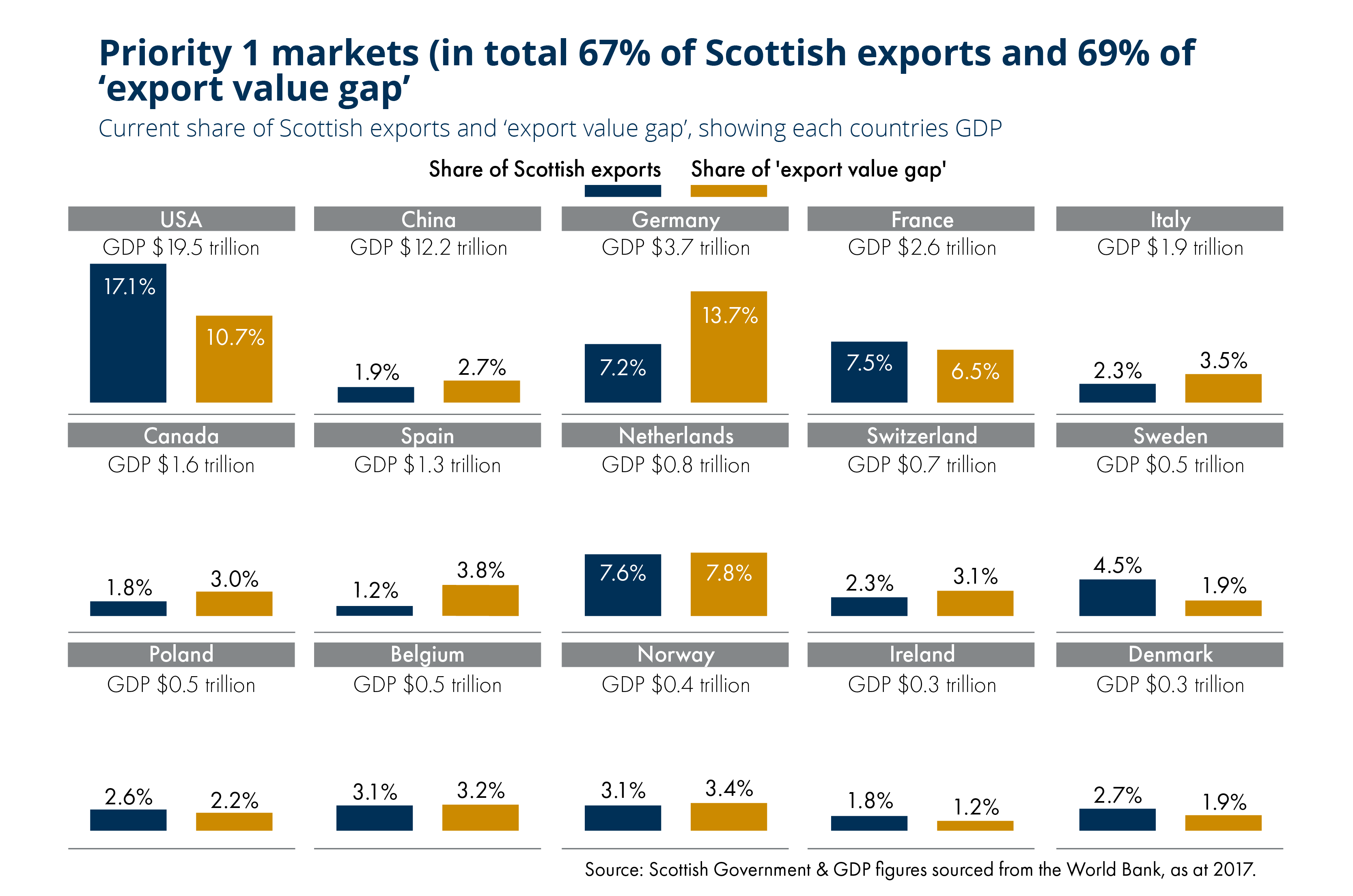

A Trading Nation included £20 million of funding over the first three years of the plan to support businesses engaged in trade and investment. To target this investment, the Scottish Government profiled the 26 countries which accounted for over 80 per cent of current exports, and identified these countries’ share of the ‘export value gap’.

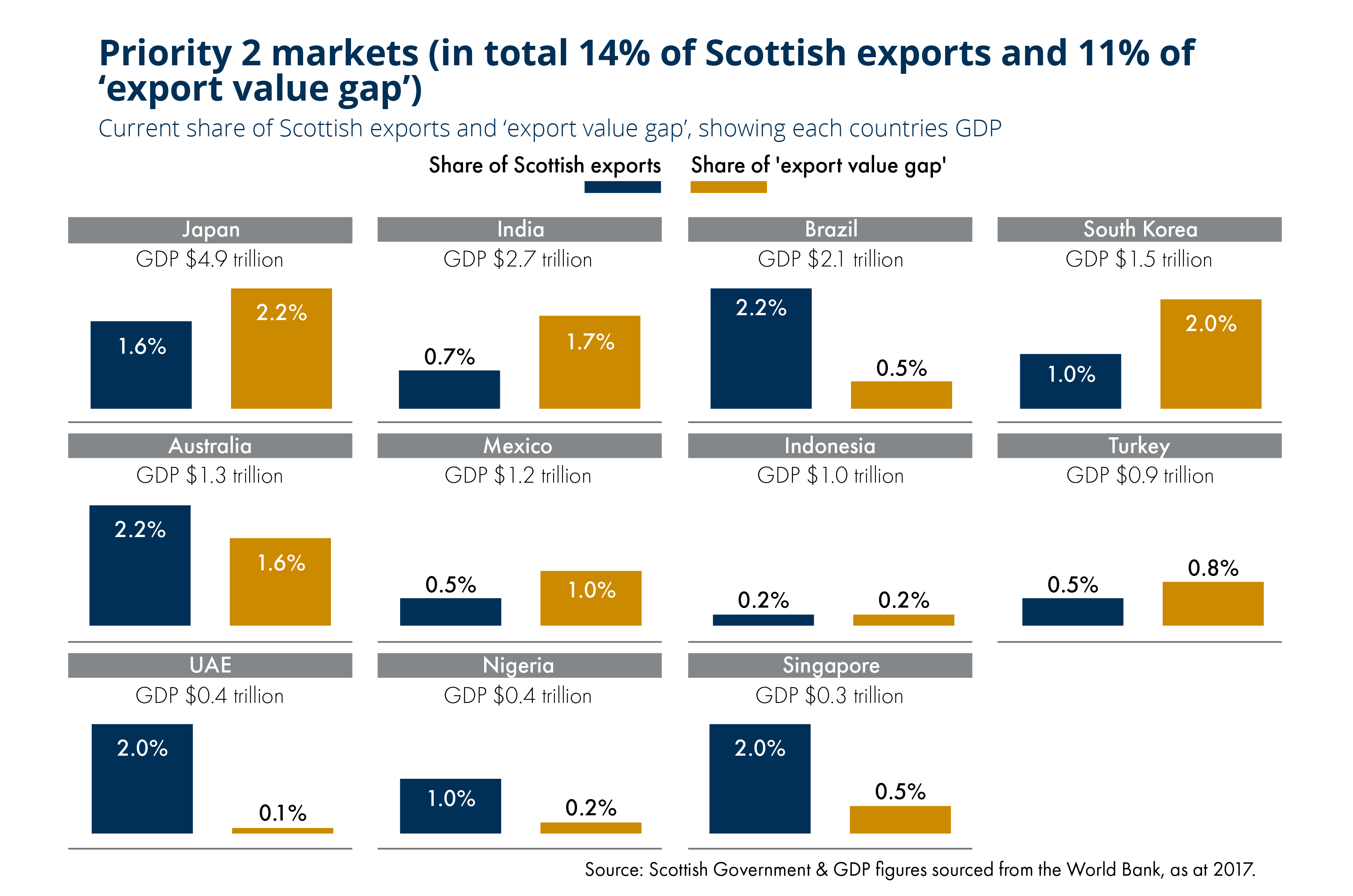

This profiling led to the identification of 15 priority one countries and 11 priority countries.

In September 2022, the Scottish Government published a progress review of the Trading Nation strategy. This reflected on progress since the strategy was published in 2019, and noted the significant shocks which have affected global supply chains such as Brexit and the Covid-19 pandemic.

In January 2021, immediately after the end of the EU transition period, the Scottish Government published its Vision for Trade. This vision set out the five principles that the Scottish Government intended to guide how the Scottish Government would seek and support trading relationships.

The vision linked to three other strategies: A Trading Nation which highlights the priority markets where Scotland should achieve export growth, and the Inward Investment and the Capital Investment plans which highlight the opportunities to invest in Scotland. The vision stated that it aimed "...to build the right trading conditions which facilitate implementation of operational trade and investment plans".

Since 2019, there have been a number of geopolitical shocks and global events which have impacted on world trade flows. From a UK perspective, one of these events, the UK's departure from the European Union was a policy choice of which the main impact - a fundamental change to the trading relationship with its main market - fell on the UK itself. Other events such as the COVID 19 global pandemic and Russia's illegal invasion of Ukraine have impacted on Scotland and the UK along with the rest of the world.

Case studies included at the conclusion of the briefing set out the trading performance in areas such as financial services, food and drink and mineral fuels, lubricants & related materials.

How this briefing is structured

This briefing intends to give a broad overview of exports from Scotland, covering the data we have on what is exported and to where, as well as an overview of recent policy to support exporters, and the international context.

Section 1 sets out why governments are interested in exports

Section 2 looks in more detail at the two main sources of data on exports

Section 3 gives an overview of recent policy to support exporters

Section 4 gives an overview of international developments which have had an impact on Scotland's trade

Section 5 comprises 3 case studies covering significant sectors within Scotland's exports

Why are we interested in exports?

There are a number of reasons why the performance of exporting businesses is important to understand. Economists suggest that increasing the proportion of firms able to export is a key driver of productivity. 1Research by the European Central Bank notes that:

On the export side, the possibility to expand into larger (export) markets provides incentives to improve the efficiency or quality of production, thereby boosting productivity within firms.

In the evidence paper which accompanied the Scottish Government's National Strategy of Economic Transformation (March 2022)2, the Scottish Government note that:

While Scotland has grown its international exports over the past 20 years, their value as a share of GDP has remained broadly static and remains low relative to comparable small advanced economies.

Growing productivity is understood to be an important way of driving improvements to living standards. A House of Lords briefing on Economic growth, inflation and productivity notes that:

A key mechanism through which economic growth is understood to lead to higher living standards is productivity growth. Economic growth can also be the result of increased employment or investment, but these processes do not necessarily lead to rising wages or incomes. Productivity growth, however, means that businesses can produce more output per given labour input, which effectively increases the value of labour in the production process, allowing for higher wages.

The Scottish Government has a ten-year export growth strategy (A Trading Nation, May 2019) which includes the headline goal of increasing the value of exports as a proportion of GDP to 25%3. The years since this strategy was launched have been marked by considerable turmoil affecting international markets and supply chains. Following the UK's exit from the EU Scottish exporters must negotiate different and evolving trading relationships; the Covid-19 pandemic had a considerable impact on international supply chains; and most recently the Russian invasion of Ukraine has had a significant impact on key markets including agricultural produce and oil and gas.

Figure 1 below shows the value of Scottish international exports of goods and services compared with Scotland's onshore GDP since 2001i. This shows the value of Scotland's exports compared to GDP has always been below this 25% target, and has fallen since 2002. Since the launch of the Trading Nation strategy, the value of exports compared to GDP grew to 21% in 2019, but has fallen to 18.6% by 2021 as the value of exports grew more slowly than the size of the economy.

In November 2023, the Scottish Government published Export Statistics Scotland 2021, the most comprehensive dataset on Scotland's exports which had been delayed due to the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on data collection.

Scotland's export performance - main data sources

This section will set out the latest data from the two main sources on Scotland's exports, as well as noting other sources which might be considered.

Exports Statistics Scotland

Overview: Exports Statistics Scotland (ESS) published by the Scottish Government provides annual data on the value of exports from Scotland to the rest of the UK and internationally. It bases its analysis on the sale of goods and services to customers outside Scotland. The analysis is based on economic activity of the business, allowing the data to be broken down by Standard Industrial Classification code.

Exports Statistics Scotland (ESS), published by the Scottish Government, provides estimates of the value of Scotland's international exports and exports to the rest of the UK. This annual publication provides the values of export for all sectors including the manufacturing and service sectors but excluding oil and gas.

ESS defines exports as direct sales of goods or services to customers based outside Scotland. This includes sales to visitors to Scotland - businesses completing the global connections survey are asked to provide their best estimate as to the proportion of their sales to visitors or customers based outside Scotland. The estimated value of goods excludes VAT, freight and insurance costs.

The primary source of data for ESS is the Global Connection Survey (GCS). The GCS is sent to a representative sample of 6,000-10,000 businesses with operations in Scotland. It collects data about businesses sales to customers in different locations. If a business sells goods or services to a customer not based in Scotland, this is counted as an export. Where data is unavailable the Scottish Government uses other sources such as the Office for National Statistics or HMRC. A full list of data sources is available on the Scottish Government website.

The data is classified by sector using the Standard Industrial Classification (SIC). SIC codes provide a framework for classifying economic activity for the collection, tabulation, presentation and analysis of data. Classification is based on the economic activity of the business. This allows it to be compared to other sources which use the SIC codes. However, some codes are excluded from the analysis.

In 2020, the Scottish Government decided to delay the collection of the GCS data. This was because of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and to allow businesses to focus on preparing for the end of the EU Exit Transition Period. Due to this delay the Scottish Government changed the methodology. They switched from using the ONS Inter-Departmental Business Register (IDBR) to using the Scottish Annual Business Statistics (SABS) as their basis for company turnover.

Due to this change in methodology the latest publication provides data for 2019 to 2021. Prior to this the data was available from 2002 onwards.

More information on the ESS methodology can be found on the Scottish Government website.

ESS provides a broad overview of Scotland's exports, covering goods, services and other exports such as utilities. It also provides detail of exports to the rest of the UK, to the European Union and to the rest of the world. The most recent publication, published in November 2023 set out data covering 2019, 2020 and 2021.

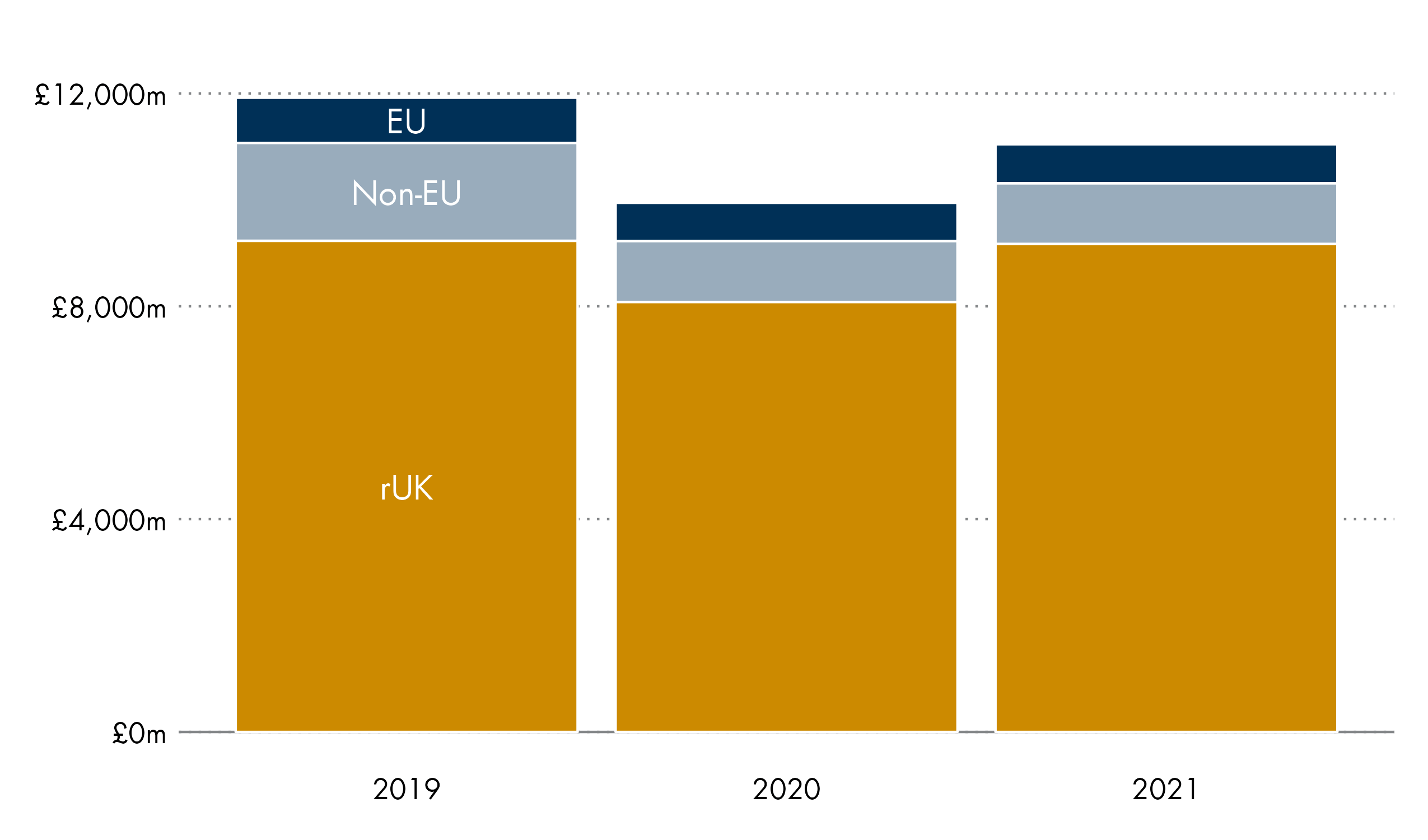

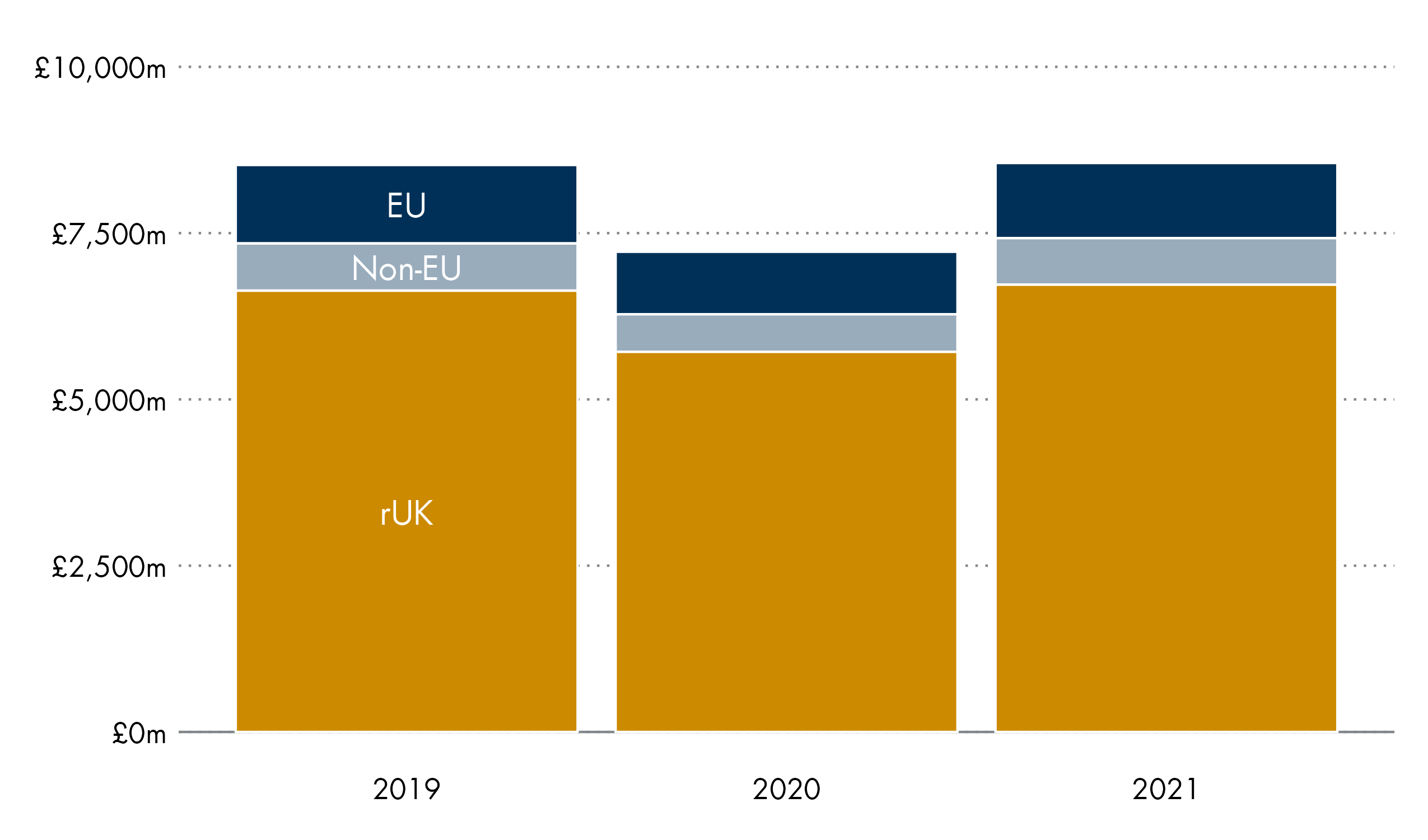

In 2021 the value of exports was £80 billion, which is a fall of £2.2 billion (2.6%) compared to 2019. The fall in the value of exports since 2019 was not uniform; exports to the EU reduced by £2 billion (-11.7%), to the rest of the world by £2.1 billion (-11.2%), but exports to the rUK grew by £1.9 billion (4%).

Looking at the sectors, manufacturing exports in 2021 were worth £28 billion, which was a fall of £0.9 billion (-3.1%) since 2019. Manufacturing exports to the rUK account for 41.7% of the total.

Exports of services were worth a total of £39 billion in 2021. Unlike manufacturing, these are predominately to the rest of the UK which accounted for 69% of service exports in 2021. Service exports to all destinations declined between 2019 and 2021; to the rUK by £0.8 billion (-3%), to the EU by £0.6 billion (-9.7%) and to the rest of the world by £1.5 billion (-18.1%).

Other exports (which include agriculture, mining, utilities and construction) were worth £12.5 billion in 2021, and grew by £1.7 billion (15.5%) since 2019. The rUK is the destination for the vast majority of other exports, accounting for 80% by value in 2021 and driving almost all the growth in value compared to 2019 (an increase of £1.7 billion, 20.4%). Other exports to the EU decreased by £60 million (-5.7%), and other exports to the rest of the world increased by £50 million (3.5%).

Regional Trade Statistics

Overview: Regional Trade Statistics published by HMRC provides quarterly data on the value and mass of international exports from the UK, broken down by nation and region. The analysis is based on movement of goods based on the Standard International Trade Classification (SITC)

The Regional Trade Statistics (RTS), published by HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC), were developed to support the economic decision-making of the devolved administrations and other regional bodies within the UK. This quarterly publication gives detailed information on exports and imports, broken down by nation and region of the UK. It provides data on the value and mass of trade. However, it should be noted that it only provides information on trade in goods and does not cover trade in services.

The RTS data is based on HMRC’s Trade in Goods Statistics (TIGS) dataset. This data covers the UK’s international trade in goods disaggregated to country and product level based on trade declarations. The data is attributed to each UK region and nation based on the distribution of employees of a business across the UK.

Exports are classified using the Standard International Trade Classification (SITC) which is a standardised way of classifying goods. The groupings of SITC reflect:

the production materials;

the processing stage;

market practices and uses of the products;

the importance of the goods in world trade;

technological changes.

More information on the methodology can be found on HMRC's website.

ONS also publish sub-national experimental trade statistics, based on HMRC data, with estimates of the value of exports, imports and balance of goods for International Territorial Levels (ITLs) and city regions, broken down by industry and EU and non-EU split.

This section looks at data from the HMRC regional trade in goods statistics database. HMRC publish quarterly data around 10 weeks after the end of each three month period, and so is much more timely than Export Statistics Scotland (the latest data covers January to March 2024 and was published on 13 June 2024). However, the data covers only exports of goods internationally, and does not cover exports to the rest of the UK. There are some definitional differences between these two sources which are discussed in a later section.

HMRC provide data in terms of value of exports, and also in terms of mass of exports which allows us to account for price differences and inflation.

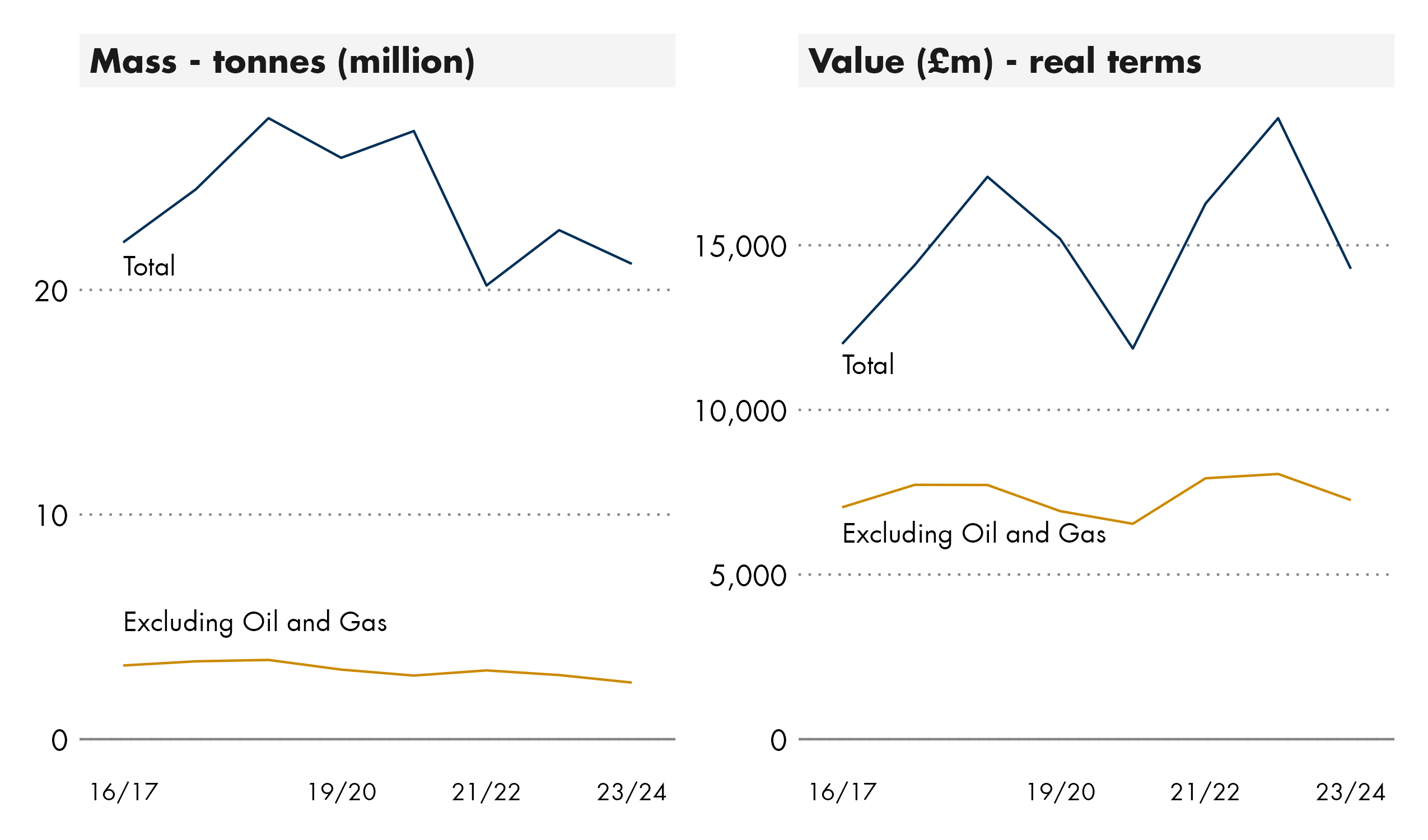

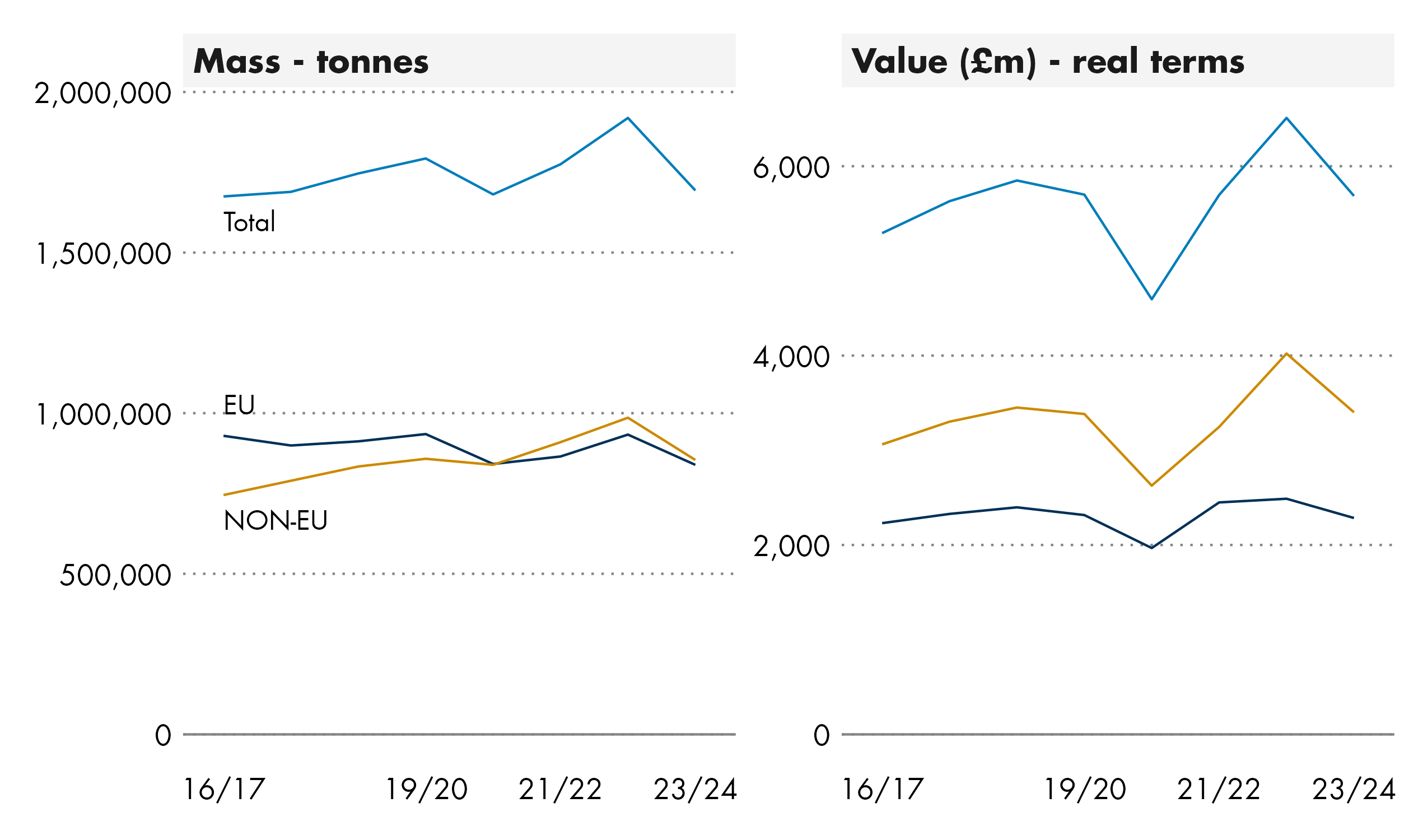

The mass of exports from Scotland peaked in 2019/20; by 2023/24 the total mass of Scottish exports had reduced by 41% compared with 2019-20, with non-EU exports reducing by 84% and EU exports by 18%.

The value of Scottish international goods exports peaked in 2022/23, with total exports worth £37.3 billion, up from £25.7 billion in 2016/17, representing an increase of 45%. However, when we adjust for inflation, as shown in the above chart, this is an increase of 23%. Exports to the EU have increased in real terms by 19% between 2016/17 and 2023/24, however they fell by a quarter between 2022/23 and 2023/24 and are now around 2017/18 levels. Exports to non-EU destinations have fallen by 18% in real terms between 2016/17 and 2023/24, with the real term value remaining between £11 and 12.5 billion since 2019/20.

A key factor in these trends is exports of oil and gas. For example, in 2019/20 China was the second most valuable destination for petroleum products exports, worth £3.6 billion. By 2023/24, they were worth £71,000. Due to the global energy price increase, exports of gas from Scotland increased by 700%, or £2.6 billion, between 2019/20 and 2023/24, with exports to Ireland increasing by 735% or just under £2.5 billion.

Excluding oil and gas, the real terms value of Scotland's exports reduced by 2% between 2016/17 and 2023/24; the value of exports to the EU increased by 3% while non-EU exports reduced by 5%.

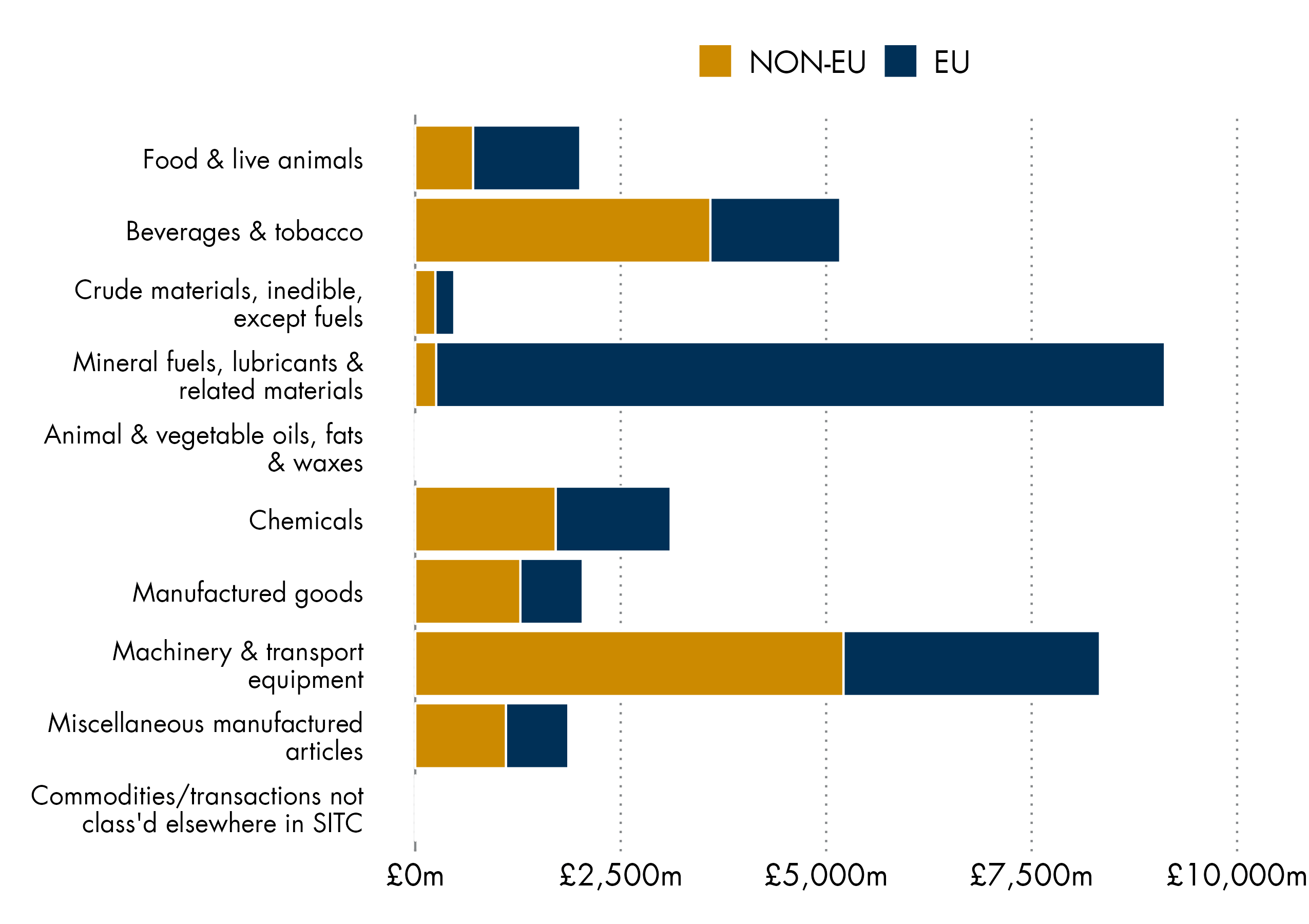

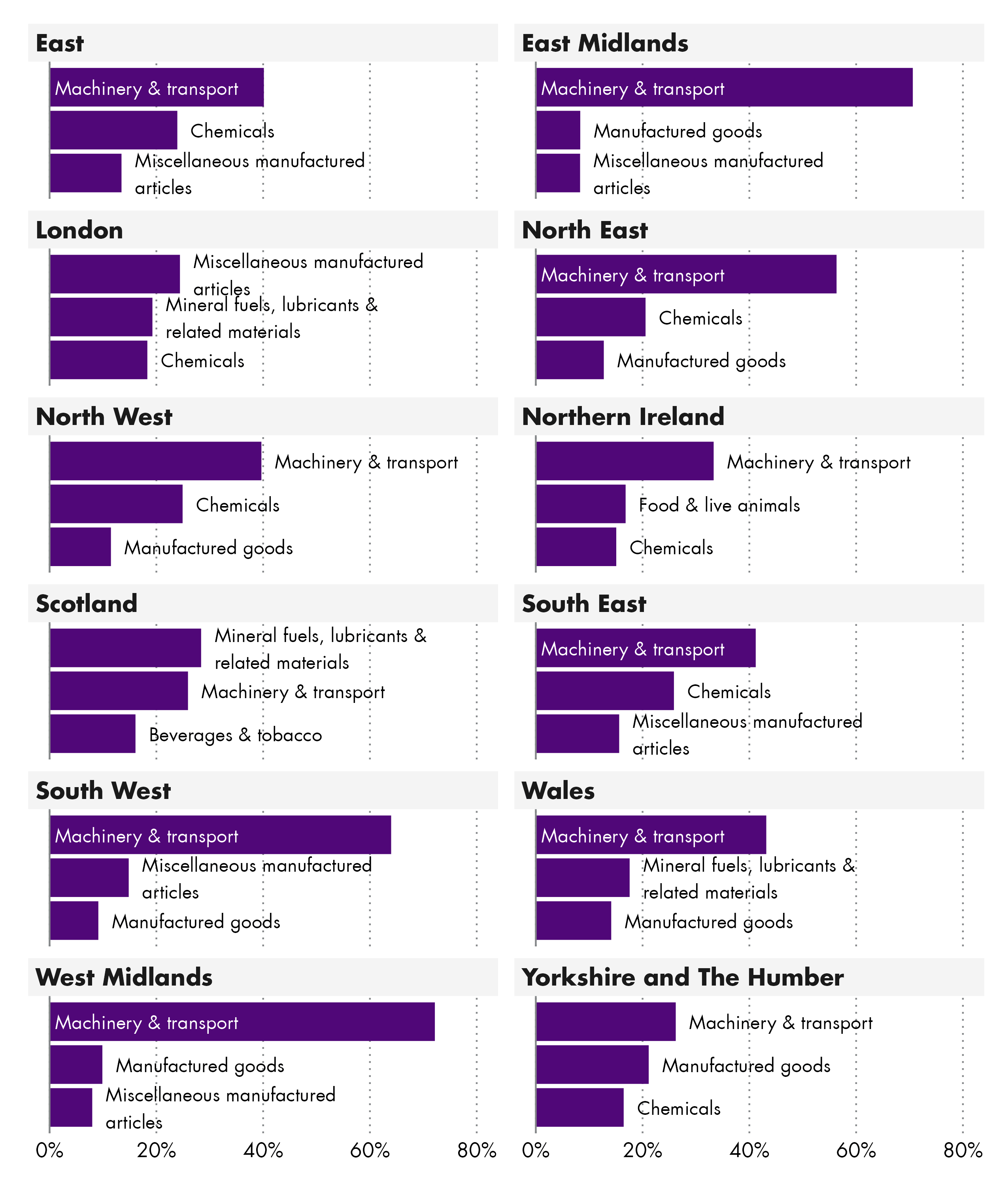

Looking at the full year data for 2023/24, the most significant sectors of exports by value were

'Mineral fuels, lubricants & related materials' worth £9.1 billion, with 97% going to the EU and 3% to the rest of the world

'Machinery & transport equipment' worth £8.3 billion, with 37% going to the EU and 63% to the rest of the world

'Beverages and tobacco' worth £5.1 billion, with 31% going to the EU and 69% to the rest of the world

Figure 4 below sets out the main sectors of good exports, showing the proportion of goods going to the EU or to the rest of the world.

How do Scottish exports compare to exports from the rest of the UK?

The RTS data allows a user to break the data down by UK region, so we have compared Scotland and the rest of the UK (UK excluding Scotland). Overall, the value of exports from Scotland has fallen by 1% in real terms between 2016/17 to 2023/24 while exports from the rest of the UK have fallen by 7% over the same period. However for both, in real terms the value of exports are below pre-pandemic levels, with Scottish exports 17% lower while the rest of the UK has fallen by 7%.

Why is this? For Scotland, the value of exports to non-EU destinations has fallen 28% in real terms, which is linked to the fall in petroleum products exports. The rest of the UK has seen a fall of 9% in real terms.

Scottish exports to the EU have increased by 19% between 2016/17 and 2023/24, but are 6% below pre-pandemic levels. For the rest of the UK they have fallen by 6% from 2016/17 and are 5% below pre-pandemic levels.

How does what Scotland exports compare to the rest of the UK?

Across the UK in 2023/24, all regions except Scotland and London have machinery & transport equipment as the highest value of exports by broad commodity group.

'Mineral fuels, lubricants & related materials' was the most valuable export from Scotland, worth £9.1 billion.

'Beverages & tobacco' is the third most valuable export from Scotland, which is linked to Whisky exports, worth £5.1 billion.

Other data sources

Aside from the main data sources described earlier in this briefing, there are other sources that users may wish to consider.

The Scottish Quarterly National Accounts (QNAS)

The Scottish Quarterly National Accounts (QNAS) produced by the Scottish Government provide estimates of Scotland's exports on a balance of payments basis. This means that exports are counted when there has been a change in economic ownership - where all risk, rewards, and rights and responsibilities of ownership are transferred. In most cases, a change in economic ownership will happen at the same time as a change in legal ownership, but there are some exceptions such as some transactions involving leases. The series provides the total value of 1exports of goods and services to the rest of the UK and to the rest of the world annually and quarterly, as well as imports from the rest of the UK and the rest of the world. Further information is available on the Quarterly National Accounts website.

The Scottish Government also publish Quarterly energy statistics Scotland. The Q4 publications include a summary of Scotland's imports and exports of electricity.

Office for the Internal Market (OIM)

The Office for the Internal Market (OIM) is part of the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA). The OIM independently advises the UK Government and the devolved administrations on how specific laws, rules and regulations impact the UK Internal Market and reports on how well it is working.

The OIM has published plans which note that the ONS is planning to produce experimental estimates for interregional trade covering all four UK nations in 2024. The ONS published a methodology for producing these experimental statistics in July 2023.

In May 2024, the OIM published an update on their data road map which noted that experimental statistics of intra-UK trade covering four nations is expected to be available in Autumn 2024.

Comparability of data sources

Looking across different sources, there are differences in how trade value is attributed to Scotland. ONS begins with a trade value for the UK, and then apportions trade to Scotland using the proportion of employees in each region of the UK. In contrast, ESS finds businesses that have economic activity in Scotland, based on Scottish local units from the Inter-Departmental Business Register (IDBR), and then estimates the export activity of these Scottish companies.

| Measure | RTS | ESS |

|---|---|---|

| Value | Y | Y |

| Mass | Y | N |

| Goods | Y | Y |

| Services | N | Y |

| Frequency | Quarterly | Annual |

Scotland's international exports - the policy approach

While responsibility for negotiating international agreements, including trade deals, is reserved, the Scottish Government has a number of strategies which aim to support firms exporting. This section will look at the policy context both before and after the UK's exit from the European Union.

The Trade Board was established in 2017 to support the then trade and investment strategy. It has met between 2 and 4 times per year. Its remit is to provide the Scottish Government with advice to support the International Trade and Investment Directorate, provide insights on the trading situation for key Scottish sectors, and promote the benefits of exporting to businesses. In 2022 the membership of the board was updated to reflect the priority sectors identified in the Trading Nation strategy. The current membership is:

ABC Bank

Proserv

Scottish Business Network

University of Strathclyde

Nova Innovation

Verlume

Fios Genomic

Summerhall Distillery Ltd

Scottish Engineering

IQVIA

DirectID

Scotland Food and Drink

Policy before Brexit

On 1 May 2019 the Scottish Government published ‘A Trading Nation – a plan for growing Scotland's exports’. This plan set a headline target of growing exports from 20% to 25% of GDP over ten years.

The Scottish Government described ‘A Trading Nation’ as the most detailed examination of Scotland's international exports ever undertaken by the Scottish Government, and at 230 pages it is certainly comprehensive. In preparing the strategy, the Scottish Government posed four key questions;

What are the export strengths we should promote?

Where should we promote these strengths and when should we step up our presence in these markets?

Who should we work with most intensively to boost out export performance?

How do we best configure government and wider support to deliver export goals?

To explore and answer these questions, the plan was put together with engagement from over 30 organisations including the UK Directorate for International Trade (DIT), the Scottish Council for Development and Industry, Chambers of Commerce, the Confederation of British Industry Scotland, the Institute of Directors, the Federation of Small Business, Universities Scotland and the Fraser of Allander Institute.

In contrast to the previous exports strategy, ‘A Trading Nation’ focused resources on countries and sectors which it stated were most likely to deliver the largest, most sustainable contributions to Scotland's economic growth.

The plan included several actions which the Scottish Government and agencies would aim to undertake to achieve the strategy's aims.

Analyse key markets – USA and China – at sub-nation level.

Build on existing academic links in the advanced technology sector to create significant Scottish presence in those markets.

In contrast to traditional export promotion activities (focused on a specific sectoral trade mission), opportunity to pioneer a new approach of identifying specific challenges in target markets and positioning a strategic cross sectoral offering.

Undertake analysis of the sub-sector economic impact – ie how exports in one sector will increase GDP in Scotland.

Given the uncertain political context, it was very likely that the conditions of trade with the countries and sectors identified in the plan would change over time, and there was a commitment to keep the plan under review.

The plan included £20 million of funding over the first three years of the plan to support businesses engaged in trade and investment. To target this investment, the Scottish Government profiled the 26 countries which accounted for over 80 per cent of current exports, and identified these countries’ share of the ‘export value gap’. This gap was calculated by comparing Scotland's 2015-17 exports with those of similar competitors. Details on this calculation are set out in section 4.1 of the analytical methodology note. The top 15 countries were priority 1 markets where the Government expected the bulk of future growth to come from, the chart below lists these.

The Government stated that exporters to these priority 1 markets – representing 66% of international exports – would be supported by the Scottish Government through:

Scottish Development International in-market presence.

Trade envoys, often with a focus on specific sectors (the plan suggests a possible increase from 4 to 12).

GlobalScot expansion (from 600 to 2,000).

Priority for in-market sector specialists.

Priority for trade missions and ministerial visits.

The next 11 countries were designated priority 2 markets (see above). These countries accounted for 14% of current international export value and 11% of the export value gap. The plan stated that these markets would be supported through the expansion of the GlobalScot network and Trade Envoys, close working with DIT, and might also benefit from SDI in-market presence, a scaled back set of the policy responses identified for priority 1 countries.

Trading Nation Progress Review 2022

In September 2022, the Scottish Government published a progress review of the Trading Nation strategy. This reflected on progress since the strategy was published in 2019, and noted the significant shocks which have affected global supply chains such as Brexit and the Covid-19 pandemic (these shocks are covered more later in this briefing).

The Scottish Government quotes analysis of business survey data which highlights that these conditions are challenging for exporting firms in Scotland, but despite these challenges exports remain equivalent to about 21% of GDP (against a target to increase this to 25% by 2028). The Scottish Government notes that:

Scotland's international exports will require significant annual growth over the next eight years to achieve the 25% target

The progress report also set out the key actions that the Scottish Government planned to take to support exporting firms:

Develop 'Skills for Exporting', to set out an assessment of the needs of exporters following EU Exit, and support available from partner organisations.

Ensuring the criteria and definitions within the segmented model of export support continue to capture both existing and emerging export growth potential.

Developing an approach to trade missions and overseas ministerial visits that is consistent with net zero obligations and the Vision for Trade.

Expand business networks, including the GlobalScot network in priority markets and sub-sectors, and increase the number of exporters that can directly access their expertise and advice.

Embed Vision for Trade commitments into the evaluation of priority markets

Use sectoral plans such as the Hydrogen Action Plan and its related Hydrogen Sector Export Plan to find and support new markets for our products and services across the sectors that will drive net zero.

Develop sub-national plans in particular for the USA as resources permit.

Refine the approach to engagement with emerging markets in the 2nd tier of ATN priority markets.

Identify major international events over the next three years to target for major Showcasing Scotland promotional activities, including Osaka Expo 2025

Leverage support from the UK Department of International Trade for companies to ensure it complements existing trade support options

Ensure exporters are aware of the increasing net zero considerations of consumers and businesses.

Work towards addressing key NSET ambitions, such as talent attraction, by using global networks effectively

Since Brexit

Since the UK's exit from the EU, the Scottish Government has published several strategies which touch on exports.

In January 2021, immediately after the end of the transition period, the Scottish Government published its Vision for Trade. This vision set out the five principles that the Scottish Government intended to guide how the Scottish Government would seek and support trading relationships. The five principles were:

Inclusive growth: Trade should drive economic development, provide good quality jobs, improve quality of life and reduce inequality.

Wellbeing: Increased wellbeing is one of the main purposes of the National Performance Framework

Sustainability: Trade decisions should consider sustainability through economic, social and environmental lenses.

Net zero: Trade should be supporting the Scottish Government's transition to net zero.

Good governance: Decisions must be compatible with the international rules-based system at all times.

The vision linked to three other strategies: A Trading Nation which highlights the priority markets where Scotland should achieve export growth, and the Inward Investment and the Capital Investment plans which highlight the opportunities to invest in Scotland. The vision stated that it aimed "...to build the right trading conditions which facilitate implementation of operational trade and investment plans".

The Scottish Government has published two annual reports, the most recent in June 2023. Key activity covered in this report includes1:

The Scottish Government has been exploring how to improve trading conditions and increase market access for Scottish goods and services sectors, including by completing a market access barrier pilot.

Implementing action plans to address top market access barriers.

Establishing the Scottish Services Trade Forum to advise the Scottish Government on trade in services.

The Scottish Government has developed a methodology to identify and prioritise the most significant market access barriers affecting Scottish trade. This year the Scottish Government piloted this methodology with market barrier data from the UK Government's Digital Market Access Service (DMAS). This pilot focused on goods and related regulatory barriers, followed by digital and services trade barriers. The findings of this pilot will inform the allocation of resources to address barriers that most affect Scottish businesses.

Findings from the exercise included:

Gaps in quantitative data on trade in services mean that additional qualitative sources are needed to review service-related market access barriers.

Available detail in DMAS on barriers varies, which can make prioritisation more challenging. For those with limited detail, further consultation with stakeholders, within the Scottish Government and with the UK Government is a necessary step to help determine which barriers are of most interest to Scotland.

The principles set out in the Vision and wider Scottish Government policy were determinate in prioritising barriers, such as our Net Zero ambitions.

The resolution of most barriers will take a long time and cannot be achieved by the Scottish Government alone, so time to resolve a barrier must be central to the prioritisation methodology.

The UK context

International relations (including international trade) are a reserved matter under the Scotland Act 1998. This means that the Scottish Government has no formal role in the development of UK trade policy, nor in negotiating and signing international treaties. The Scottish Parliament also has no formal role in the scrutiny and ratification (i.e. approval) of trade agreements.

This means that Scottish Government or Scottish Parliament input into the negotiation of UK trade agreements may be limited.

In August 2018, the Scottish Government published Scotland's role in the development of future UK trade arrangements. This policy paper set out "the role of the Scottish Government, Scottish Parliament and others in the development of future UK trade arrangements"1. The policy paper was published in the context of the UK leaving the European Union upon which the UK would regain responsibility for negotiating its own trade agreements. The policy paper stated:

The conduct and content of future trade policy, negotiations and agreements will have very important implications for Scotland. The broad and increasing scope of modern trade agreements means that they often deal with and merge a range of reserved and devolved policy areas, and touch on many areas of life. In addition, the Scottish Parliament and Scottish Ministers are responsible for observing and implementing international obligations, and would be responsible for the payment of any compensation costs arising from, for example, claims under investor state dispute settlement, present in many modern trade deals. Given these responsibilities, it is important that Scottish Ministers have full, early and formal involvement in policy formulation and opportunities to influence the development and agreement of international negotiations, including in formulating and negotiating mandates. The UK Government must involve the devolved authorities at each step to ensure any future agreements deliver for the whole of the UK.

Scottish Government. (2018, August 30). Scotland's role in the development of future UK trade arrangements. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/publications/scotlands-role-development-future-uk-trade-arrangments/ [accessed 23 July 2024]

During the negotiation (between 2021 and 2023) of the Comprehensive And Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, the UK Government stated that it had kept the Devolved Administrations involved at every stage of negotiations, and that the Devolved Administrations have provided their views on CPTPP regularly3.

Ahead of the UK General Election on 4 July 2024, the Labour Party manifesto committed to using the Scotland Office to support Scotland internationally:

The Scotland Office will maximise Scotland’s influence, and with Labour it will once again become an advocate for Scotland, both at home and abroad. The Scotland Office will ensure the voice of Scotland is properly heard on issues under the competence of the UK Government. Scotland has an enviable international reputation. Its culture, products and services are internationally renowned – from whisky and salmon to computer game development, bioscience and financial services. Labour will champion ‘Brand Scotland’ across the world through the Scotland Office, and our diplomatic and trade networks.

The Labour Party. (2024, June 13). Labour Party Manifesto 2024. Retrieved from https://labour.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Labour-Party-manifesto-2024.pdf [accessed 23 July 2024]

Following the General Election, how the Scottish Government or Scottish Parliament perspective on international trade will be considered as part of developing a UK Government negotiating strategy for international trade policy is unclear at this stage.

Scotland's international exports - impact of geopolitical events and COVID 19

Since 2019, there have been a number of geopolitical shocks and global events which have impacted on world trade flows.

From a UK perspective, one of these events, the UK's departure from the European Union was a policy choice of which the main impact - a fundamental change to the trading relationship with its main market - fell on the UK itself. Other events such as the COVID 19 global pandemic and Russia's illegal invasion of Ukraine have impacted on Scotland and the UK along with the rest of the world.

This section will summarise the impact on Scotland's exports, based on the data available for the period since the UK's departure from the EU.

The UK's departure from the EU

Following the UK referendum on leaving the EU which took place in June 2016, the UK Government chose to negotiate a Brexit which involved leaving both the EU Single Market and Customs Union.

From a trading perspective, the EU Single Market guarantees the free movement of goods and the freedom to provide services across all EU member states. The Single Market also ensures a common framework of rules, regulations and standards for all goods manufactured and sold across the EU and for all services provided. These rules apply irrespective of whether a business trades across the EU or not.

Single Market membership also provides for the free movement of capital and services, for example, the provision for passporting of financial services. This means that financial services firms authorised in one EU member state can provide their services across the EU without the need for further authorisations.

The Customs Union applies a common tariff to all goods entering from outwith the EU. As a result of this common tariff, individual Member States are unable to adopt their own independent trade policies. Instead, the EU has competence for negotiating trade agreements on behalf of the Member States.

The UK Government chose instead to negotiate a new trade agreement with the EU which formed one element of the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA). The UK formally left the EU on 31 January 2020 and left the EU's legal order, including the Single Market and Customs Union at the end of December 2020.

As a result of the Free Trade Agreement there are zero tariffs and zero quotas on the trade in goods between the UK and the EU. However, the TCA did not include any sort of agreement in terms of Non-Tariff Barriers (NTBs). As the UK in a Changing Europe outlines:

Non-tariff barriers (NTBs) can also make trading difficult. For example, countries want to be confident that imported food is safe, that animals and plants are free from disease or pests, and that other goods meet safety or labelling requirements. Exporters must produce goods that satisfy the requirements of importing countries and provide paperwork to show that those requirements are met. Even after Brexit, UK manufacturers wanting to sell into the EU market will have to produce their goods in accordance with EU standards.

UK in a Changing Europe. (2020). What would ‘trading on WTO terms’ mean?. Retrieved from https://ukandeu.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Revisited-What-would-trading-on-WTO-terms-mean-1.pdf

As well as excluding non-tariff barriers, the TCA does not provide for common regulatory standards for goods. As such, manufacturers who wish to place goods on both the UK and EU markets will need to comply with both the UK and the EU regulatory rules for those goods, even where they are different. In addition, exports from the UK to the EU need to demonstrate that they have been manufactured in line with EU rules and comply with EU rules in their end state. Linked to this, UK exporters of agri-food products are now required to meet the EU’s sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) requirements which are measures designed to protect humans, animals, and plants from diseases, pests, or contaminants.

Whilst the TCA provided a number of measures to facilitate the trade in goods, it was more limited in its coverage of trade in services. As a result of Brexit, UK nationals lost the right to free movement in the EU and the right to freely provide services across the EU.

For financial services this meant that UK based providers lost the right to passporting which facilitates the provision of financial services across the EU without the need for further authorisation. The loss of freedom to provide services has also affected others such as the cultural sector in the UK and legal services providers.

Departure from the EU also meant the UK lost access to the EU's trade agreements with around 50 non-EU countries. Whilst many of these agreements were rolled over , the UK Government has sought to renegotiate some of these whilst negotiating new Trade Agreements such as those with Australia and New Zealand.

The trade impact of leaving the EU

Identifying the impact (either positive or negative) of leaving the EU on trade figures is made more difficult due to the other events that have taken place either alongside Brexit or following it such as the COVID pandemic and Russia's illegal invasion of Ukraine. These issues are explored later in this section.

A further factor which makes comparison difficult is the increased value of exports of "minerals, fuels, lubricants and related materials" from Scotland to the EU. This product group is responsible for about 50% of the value of Scotland's exports to the EU .

As discussed earlier in the briefing, the impact of inflation makes it difficult to make a comparison of the UK's exports figures to the EU by value pre and post Brexit. As a result, above we show Scottish exports to the EU and rest of the world by both value and mass.

HMRC figures show that between 2019 and 2023 the mass of exports from Scotland to the EU fell by 17% whilst non-EU exports fell by 84%, The fall in mass of non-EU exports appears to be driven by a fall in mineral fuels (oil and gas) exports to China.

Whilst the mass of exports fell between 2019/20 and 2023/24, inflation meant that the value of Scotland's exports to the EU fell by just 3% in real terms.

If mineral fuels are excluded, HMRC figures show that between 2019 and 2023 the mass of Scottish exports to the EU fell by 17% whilst the value of Scottish exports to the EU in real terms increased by 4%.

The changing export figures, in particular the fall in mass of Scottish exports to the EU may be down to factors in addition to EU exit, for example, the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia's illegal invasion of Ukraine may also have had an impact. Directly apportioning the impact of EU exit on the changing trade figures is therefore more difficult. A report for the Independent Commission on UK-EU relations set out how UK trade with the EU has been impacted following the UK's departure from the EU:

Although goods trade between the EU and UK recovered most of its previous level in value terms following a sharp fall in the early months of 2021 the current value of trade is well below what would have been expected had the UK performed on a comparable level with other trade partners.

It was initially difficult to separate the effects of Brexit from the pandemic and Russia's invasion of Ukraine, with all major economies suffering dramatic falls in trade due to restrictions on movement and disruption to supply chains. But research released in October 2022 shows reductions in UK to EU goods trade of 16% and of EU to UK trade by 20% relative to a scenario in which Brexit had not occurred. Trade data for April 2023 showed an overall rise in global exports but goods exports to the EU remained weak declining by 0.5%.

The Office for Budget Responsibility has since found that whilst trade in other major economies has rebounded to 3% above pre-pandemic figures, UK exports remain 12% lower than in 2019 . The difference is attributed to the UK Government's decision to depart the EU on the terms set out in the TCA when other, less damaging routes were available.

Independent Commission on UK-EU Relations. (n.d.) Brexit and goods: trade strategy for unlocking UK-EU growth and opportunities. Retrieved from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/6193d9441f87e0447a3f0803/t/652d097a0e91d435123b9816/1697450365790/Brexit+and+Goods+Trade+Strategy+Oct+2023.pdf [accessed 15 May 2024]

Research by the Economic and Social Research Institute from October 2022 found that there had been reductions in UK to EU goods trade by 16% and reductions in trade from the EU to UK by 20%, relative to the scenario in which Brexit had not occurred. It said that “although goods trade between the EU and UK recovered most of its previous level in value terms following the sharp fall in the early months of 2021, this recovery leaves it well below the levels that would have been expected if it had performed on a comparable level with other trade partners.”2

The UK's withdrawal from the European Union and consequently trading with the EU under the Trade and Cooperation Agreement has made exporting to EU markets more challenging and costly for business in Scotland and the UK.

On 10 September 2024, the Scottish Parliament's Constitution, Europe, External Affairs and Culture Committee (CEEAC) published UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement: Barriers to trade in goods and opportunities to improve the UK-EU trading relationship following its inquiry into the review of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement. The Committee received evidence (both written and oral) from organisations representing business and businesses themselves.

In a written submission to CEEAC, the Federation of Small Businesses (FSB) referenced a survey of its members on the impact of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) on their trade activity during the first 8 quarters following the UK's formal exit from the EU. According to the FSB:

The number of small firms that have stopped trading temporarily with the EU fell from two in ten (19%) in early 2021 to one in ten (9%) in Q4 2022 while the number that reported stopping permanently remained around 4-5 per cent.

Feedback gathered through interviews and focus groups with FSB members shows that many small firms still find navigating UK-EU trading rules extremely burdensome.

Federation of Small Businesses. (2024, June 6). Submission to the Constitution, Europe, External Affairs and Culture Committee Inquiry into the Review of the TCA. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/-/media/files/committees/constitution-europe-external-affairs-and-culture-committee/tca-federation-of-small-business.pdf [accessed 26 July 2024]

The Scottish Chambers of Commerce also shared survey data of its members with CEEAC:

Businesses continue to manage the compliance burdens introduced in 2021, for traders in Great Britain sending goods to the EU.

These include, but are not limited to:

customs declarations,

safety and security certificates,

evidence of origin of goods, or inputs into the manufacture of goods,

import VAT requirements,

export health certificates for certain food and plant origin products, and • requirements under the EU’s REACH system (the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals).

For most businesses, this has become part of the everyday task of cross-border trade, but for others, in 2023 as in the previous two years, the burden proved too much, and some stopped exporting to the EU.

Scottish Chambers of Commerce. (2024, June 6). Submission to the Constitution, Europe, External Affairs and Culture Committee inquiry into the review of the TCA. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/-/media/files/committees/constitution-europe-external-affairs-and-culture-committee/tca-scottish-chamber-of-commerce.pdf [accessed 26 July 2024]

Almost two thirds (60%) of firms trading with the EU say it is now more difficult to do so than it was a year ago.

Almost half (49%) of exporters disagree the Brexit deal is helping them grow sales.

Two fifths (41%) of firms exporting under the Brexit deal say they face difficulties adapting to its rules on buying and selling goods.

In a written submission to CEEAC, Scottish Enterprise summarised the impact of EU exit on the businesses it supports in the following way:

Our direct relationship and support for exporters has enabled us to identify themes where companies have faced specific challenges. These include non-Tariff barriers, particularly increased costs of exporting to the EU due to additional paperwork and administration. For smaller exporters, this has been a significant challenge with many exporters deciding to refocus on the UK market or focus their available resources on fewer export markets.

Scottish Enterprise. (2024, June 6). CEEAC committee inquiry into the E-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreemen. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/-/media/files/committees/constitution-europe-external-affairs-and-culture-committee/tca-scottish-enterprie.pdf [accessed 26 July 2024]

This briefing uses the export figures either side of the UK's departure from the EU. Over the next few years, it will be important to monitor whether the initial decline in trade with the EU in some sectors is a blip as a result of EU exit, or whether Scottish trade with the EU will bounce back as businesses adapt to the new trading environment. In addition, it will be important to consider whether Scottish businesses look to target other/new markets to compensate for any loss in value from trade with the EU.

The potential impact of EU exit on different sectors is discussed in more detail in the case studies.

New bilateral trade agreements

As a result of the UK's exit from the EU, trade policy which had been an exclusive competence of the EU was repatriated to the UK leaving the UK Government responsible for negotiating future trade agreements.

In the run up to the UK's departure from the EU's legal order at the end of December 2020, a number of the trade agreements which the UK had been party to as a member of the EU were rolled over to ensure continuity following EU exit. In most cases these agreements were the same or similar to the agreement that the UK was part of when an EU member state.

A list of the UK's trade agreements in addition to the Trade and Cooperation Agreement is provided on the UK Government website.

Since EU exit, the UK has signed three new trade agreements:

Free trade agreement with Australia (entered into force on 31 May 2023)

Free trade agreement with New Zealand (entered into force on 31 May 2023)

Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (not yet in force - expected in the second half of 2024). SPICe published a briefing on CPTPP when the agreement was announced at the end of March 2023.

Evidence provided to CEEAC indicates that following EU exit, Scottish exporters have sought to develop new markets partly in response to the challenges presented in exporting to the EU. For example, Jan Robertson from Scottish Development International told the Committee:

It may be too positive to call it a silver lining, but we have seen some exporters respond to what has happened with the TCA, and particularly to reductions in the freedom of movement of labour, by investing more. That has a short-term impact on costs, but we hope that there will be long-term benefits.

That is incredibly positive, because although the EU will remain a strong partner that most of our companies will want to export to, we are seeing much more ambition and interest moving east, towards the United Arab Emirates in the middle east and towards Indonesia, Singapore and Malaysia.

Scottish Parliament. (2024, May 9). Constitution, Europe, External Affairs and Culture Committee Official Report. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/chamber-and-committees/official-report/search-what-was-said-in-parliament/CEEAC-09-05-2024?meeting=15857&iob=135370 [accessed 26 July 2024]

The COVID 19 pandemic

In the first three months of 2020, the world economy slowed abruptly as a result of the COVID 19 global pandemic. Lockdowns and restrictions contributed to significant trade disruption both to production and supply and also resulted in falling global demand.

Bank of England analysis on the effect of COVID 19 on global trade highlighted three trends1:

The pandemic affected services trade more than goods trade. Services trade fell by more than 20% in 2020, almost four times the decline in goods trade

The impact of the COVID 19 shock on trade was different across countries. In particular, the fall in Chinese trade was much smaller than in other regions.

The pandemic has had a significant impact on shipping costs, which have increased by around 350% since May 2020

Writing in October 2022, the Office of National Statistics (ONS) wrote on the impact of COVID 19 on UK trade2:

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic affected international trade in the nations and regions of the UK in 2020, which all saw decreases in both total exports and total imports from 2019.

Imports decreased in all nations and regions for trade in both goods and services from 2019 to 2020.

According to the ONS:

The impact of coronavirus (COVID 19) on UK trade was first reported in Quarter 1 (Jan to Mar) 2020, when the UK and its trading partners started to implement measures to stop the spread of coronavirus. These measures, which included border restrictions and the closure of non-essential industries, contributed to all UK nations and regions experiencing a decrease in total exports and total imports from 2019 to 2020.

Office of National Statistics. (2022, October 20). International trade in UK nations and regions: the impact of coronavirus (COVID-19): 2020. Retrieved from https://www.ons.gov.uk/businessindustryandtrade/internationaltrade/articles/internationaltradeinuknationsandregionstheimpactofcoronaviruscovid19/2020#:~:text=The%20coronavirus%20(COVID%2D19),services%20from%202019%20to%202020. [accessed 15 March 2024]

ONS figures published at the time suggested Scotland's exports of goods and services fell from £60.6 billion in 2019 to £49.1 billion in 20202. Figures for the exports of goods from Scotland showed they fell from £36.6 billion to £28.2 billion.

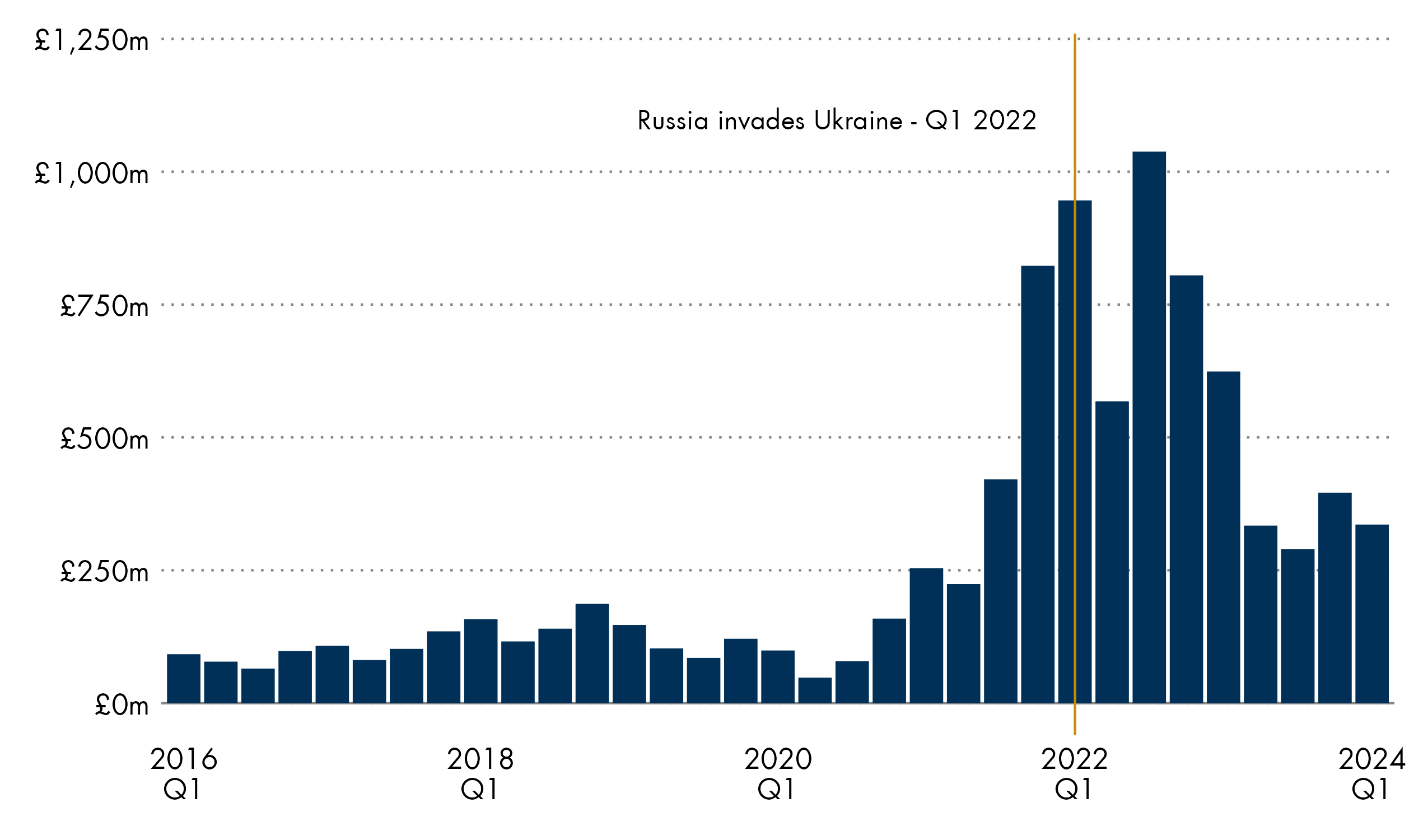

Russia's illegal invasion of Ukraine

Having already occupied the Crimean peninsula in Eastern Ukraine in March 2014, Russia launched a full scale illegal invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

At the time of the invasion Russia was a provider of a significant amount of Europe's energy supplies whilst Ukraine was the source of much of Europe's grain.

Whilst energy prices had been rising during 2021 and the early part of 2022, Russia's invasion of Ukraine exacerbated these issues. Sanctions placed on Russia meant the sale of Russian gas to Europe (including the UK) dried up leading to greater demand for the more limited supplies available. This led to volatility in gas prices and record wholesale prices1.

Ukraine is often referred to as the “breadbasket of Europe”2 with more than 70% of the country made up of agricultural land. Ukraine's main crops include sunflower, corn, soybeans, wheat and barley and it is a key food exporter around the world including to Europe and Africa. Russia's invasion of Ukraine led to difficulties for Ukraine in producing, harvesting and exporting those crops. These factors have led to food shortages and rising food prices.

The Bank of England's Chief Economist Huw Pill identified Russia's invasion of Ukraine as being a key factor in the rise in food prices that the UK has experienced over the last two years. Food price inflation peaked at 19.1% in March 2023, but has since returned to more normal levels with prices increasing by just 1.7% in the year ending May 20243. According to Huw Pill, much of that inflation is as a result of Russia's invasion of Ukraine4 which caused disruption to the supply chain of staples grown in Ukraine such as wheat and sunflower oil, and brought up costs of raw materials and basic food.

Other global supply chain disruption

A further disruption to global trade was caused by the blockage of the Suez Canal in March 2021. According to the BBC's Business Correspondent writing at the time, the Suez Canal sees around 50 vessels per day travelling through it (sometimes many more) and these vessels account for about 12% of global trade. In particular it is an important route for getting oil and liquified natural gas from the Middle East to Europe1.

At the time of the blockage which lasted for six days, it was estimated that around $9.6 billion of trade was delayed each day. The BBC reported that analysis by German insurer Allianz showed the blockage could cost global trade between $6bn to $10bn a week and reduce annual trade growth by 0.2 to 0.4 percentage points2.

Shipping costs have also been impacted by disruption to freight in the Red Sea due to attacks by Houthi rebels. Sky News noted that shipping costs have risen more than 300% since November 2023. Measures to reduce to the risk to shipping meant that journeys can take up to ten days longer and insurance costs have also increased. However, the impact on shipping costs due to these attacks has not been as great as the Suez canal blockage.

Case studies

This section will set out more detail on the export performance of three significant industrial sectors.

The first case study looks at the two largest service exports from Scotland: Financial services and Wholesale and retail trade.

The second looks at food and drink exports, with a detailed overview of seafood and beverages.

The final case study looks at refined petroleum products

Service exports

As outlined previously, Export Statistics Scotland is the best data source for Scotland's service exports. This means that the most recent data we have is for the year 2021 however.

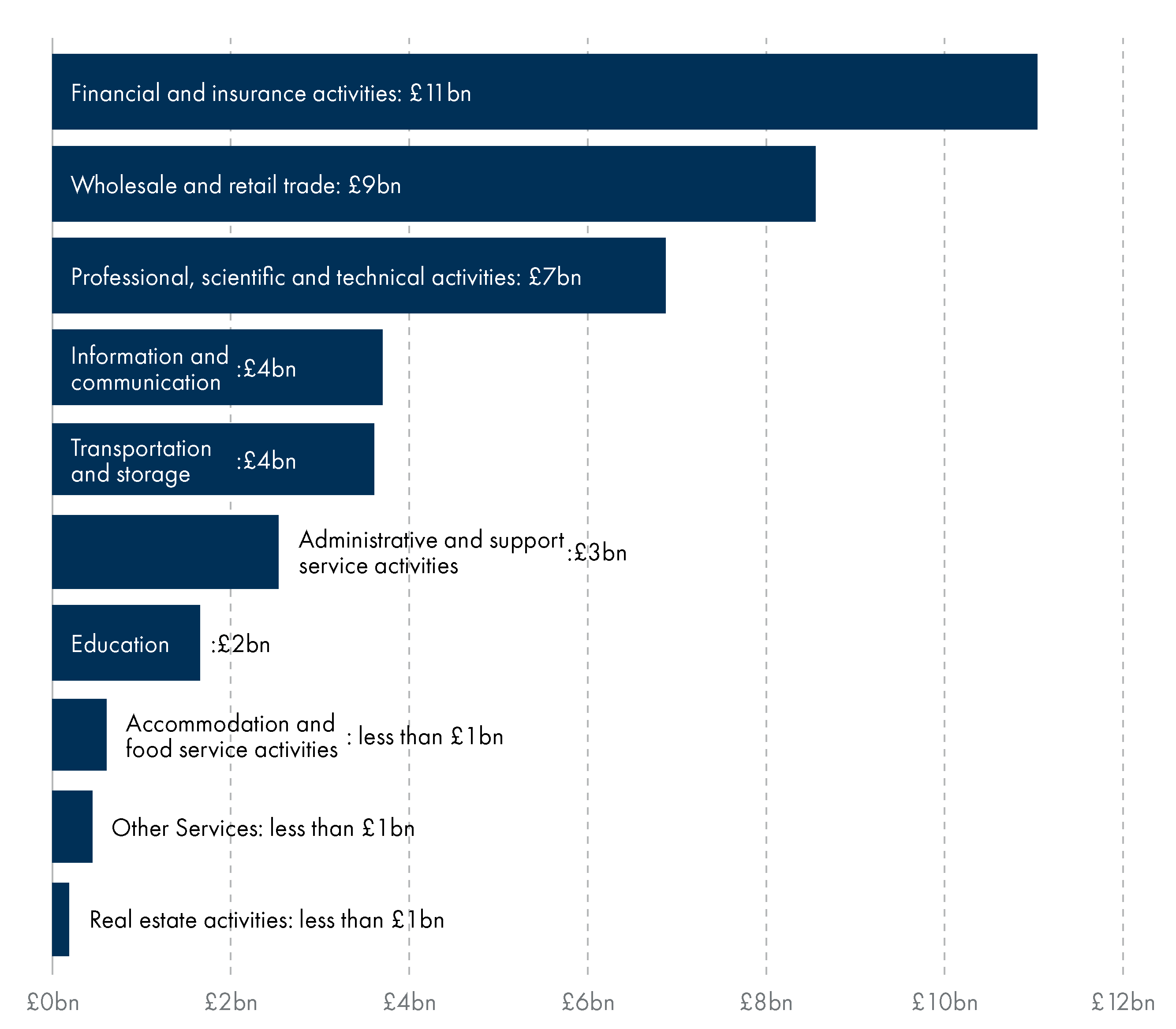

In 2021, 67.5% of all service exports were accounted for by three industrial sectors; financial and insurance activities (28.2%), wholesale and retail trade (21.8%) and professional, scientific and technical activities (17.5%). This proportion is broadly unchanged over the three years of data provided in the 2023 publication of Export Statistics Scotland.

In 2021, service exports accounted for just under half of all Scotland's exports (49% or £39.3 billion). The majority of service exports, 69% or £26.9 billion, went to the rest of the UK, with 14% or £5.5 billion going to the EU and 17% or £6.8 billion going to non-EU destinations. Professional, scientific and technical activities and education are the only sectors where more is exported to international destinations than to the rest of the UK.

Exports of education include the cost of students from outside of Scotland taking courses at Scottish educational settings - in other words UK and international students spending on tuition fees is recorded as an export of education services. When we look at education exports data in more detail it shows that while overall there has been an increase in value, it varies across destination. Exports to the rest of the UK and the EU have reduced by £85 million in total between 2019 and 2021, with the EU reducing by £25 million (8%), and the rUK figure reducing by £60 million (9%.) In real terms the figures show a total reduction of £135 million (13%), while exports to the EU had fallen by £40 million (13%), and £95 million to the rUK, (also 13%). Exports have increased by £130 million (21%), to non-EU destinations over the same period.

Financial services

The Scottish Government's 2015 Economic Strategy identified financial and business services as one of Scotland's growth sectors. While this strategy has been superseded, the Scottish Government continue to publish briefings on the economic contribution of the sector. The most recent briefing (March 2024) notes that key financial services in Scotland include global custody, asset servicing, banking, investment management, corporate finance, general / life assurance and pensions.1

The guidance note for the Global Connections Survey, which is the source of data for Export Statistics Scotland, notes that financial service exports include sales of bank and building society services, earnings on foreign exchange transactions, investment management fees and fees generated from advisory and other related functions, insurance service charges for direct insurance such as health, property and transport insurance, and service charges associated with pension schemes.

Using data from Export Statistics Scotland, we can see that the majority of financial services exports go to the rest of the UK. In 2021, £9.2 billion went to the rest of the UK which is 83% of total financial services exports. Of the rest 7% went to the EU and 10% went to non-EU destination.

In 2021 financial services made up:

15% of services exports to international destinations

13% of services exports to the EU

17% of service exports to non-EU destinations

34% of services exports to the rest of the UK

Overall, the value of exports fell between 2019 and 2021, falling by £880 million or 7%. When we look at the figure in real terms the value fell by £1,472 million or 12%. There is a variation across destinations:

International: -£820 million or 30%. In real terms: -£924 million or -34%

EU: - £115 million or 14%. In real terms: -£157 million or -18%

Non-EU: - £700 million or 38%. In real terms: -£791 million or -41%

Rest of the UK: -£60 million or 1%. In real terms: -£518 million or -12%

In November 2023 The City UK published a report on 'Exporting from across Britain: Financial and related professional services 2023'2. This report looks at international exports of financial and related services from Scotland, so not quite the same basis or geography as ESS, but provides some further detail on Scotland's financial services exports. The report notes that in 2023, Scotland accounted for 7.6% of the UK's international exports of financial services, and 4.2% of related professional service exports. 76% of Scotland's international exports were to the rest of the world, with the remaining 24% going to the EU.

The report draws on ONS data going back to 2021, which shows that international exports of financial services from Scotland increased significantly between 2015 and 2019, growing by 61% over this period from £5.2 billion to £8.4 billion. Exports then reduced to £7.6 billion in 2020 and recovered only slightly in 2021 (to £7.8 billion, £0.6 billion below the 2019 peak).

Wholesale and retail trade

"Wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles" is the second largest sector of Scotland's service exports.

The Scottish Government explains in their guidance note for the Global Connections Survey that exports from retail include all sales to tourists and other visitors to Scotland, as well as online sales, shipped products and sales with reclaimable VAT.

The majority of Scottish exports of wholesale and retail trade are to the rest of the UK, consistent with most service exports. In 2021, £6.7 billion went to the rest of the UK (79%). Of the rest 13% went to the EU and 8% went to non-EU destination.

In 2021 wholesale and retail trade exports accounted for:

15% of services exports to international destinations

20% of services exports to the EU

10% of service exports to non-EU destinations

25% of services exports to the rest of the UK

Overall, the value of exports increased between 2019 and 2021, increasing by £30 million or 0.4%. However when we look at the figure in real terms the value fell by £375 million or 4%. There is a variation across destinations:

International exports reduced by £60 million or 3%. In real terms, this is a reduction of £147 million or 8%.

EU: - £50 million or 4%. In real terms: -£103 million or -9%

Non-EU: - £10 million or 1%. In real terms: -£43 million or -6%

Rest of the UK: +£90 million or 1%. In real terms: -£228 million or -3%

Food and drink

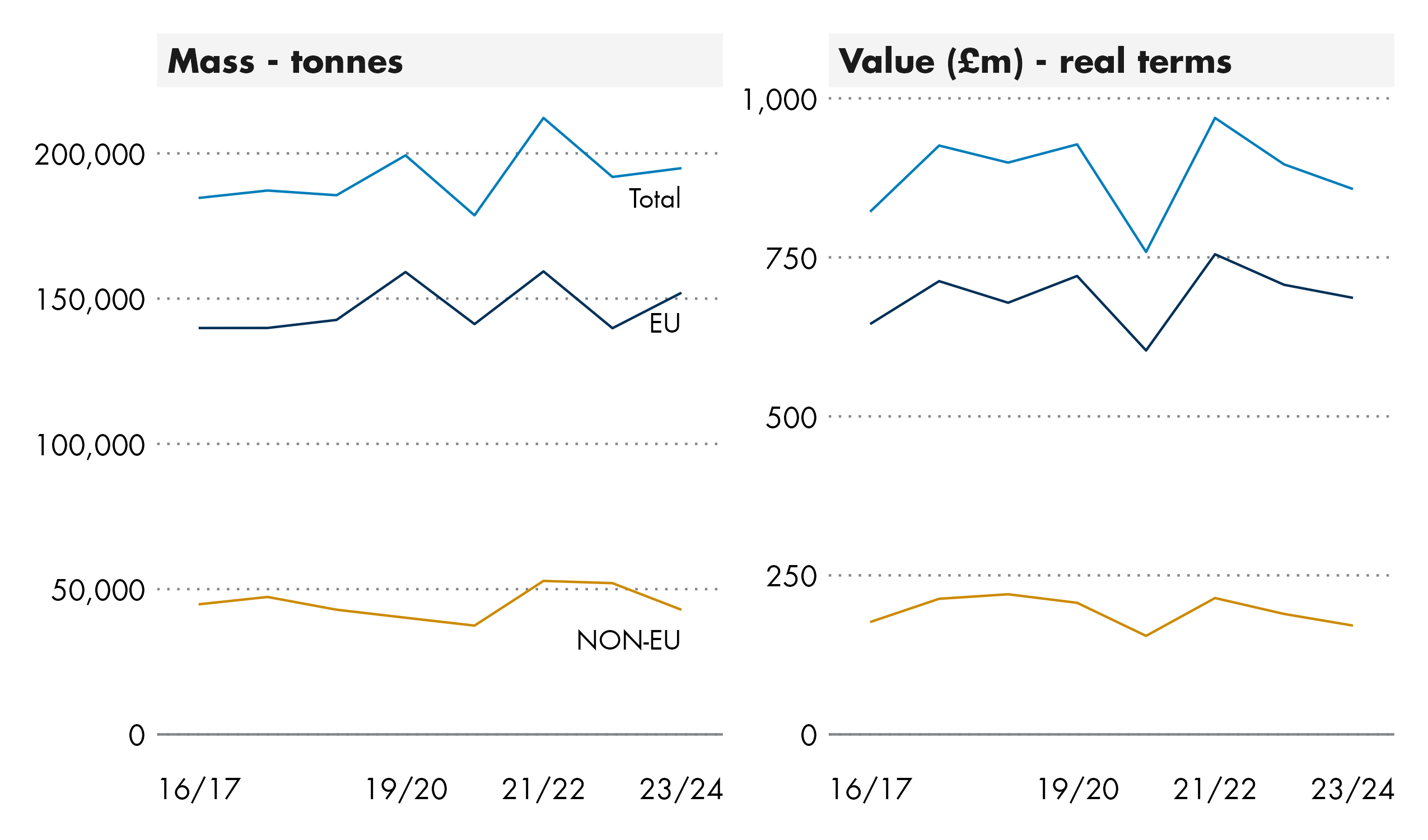

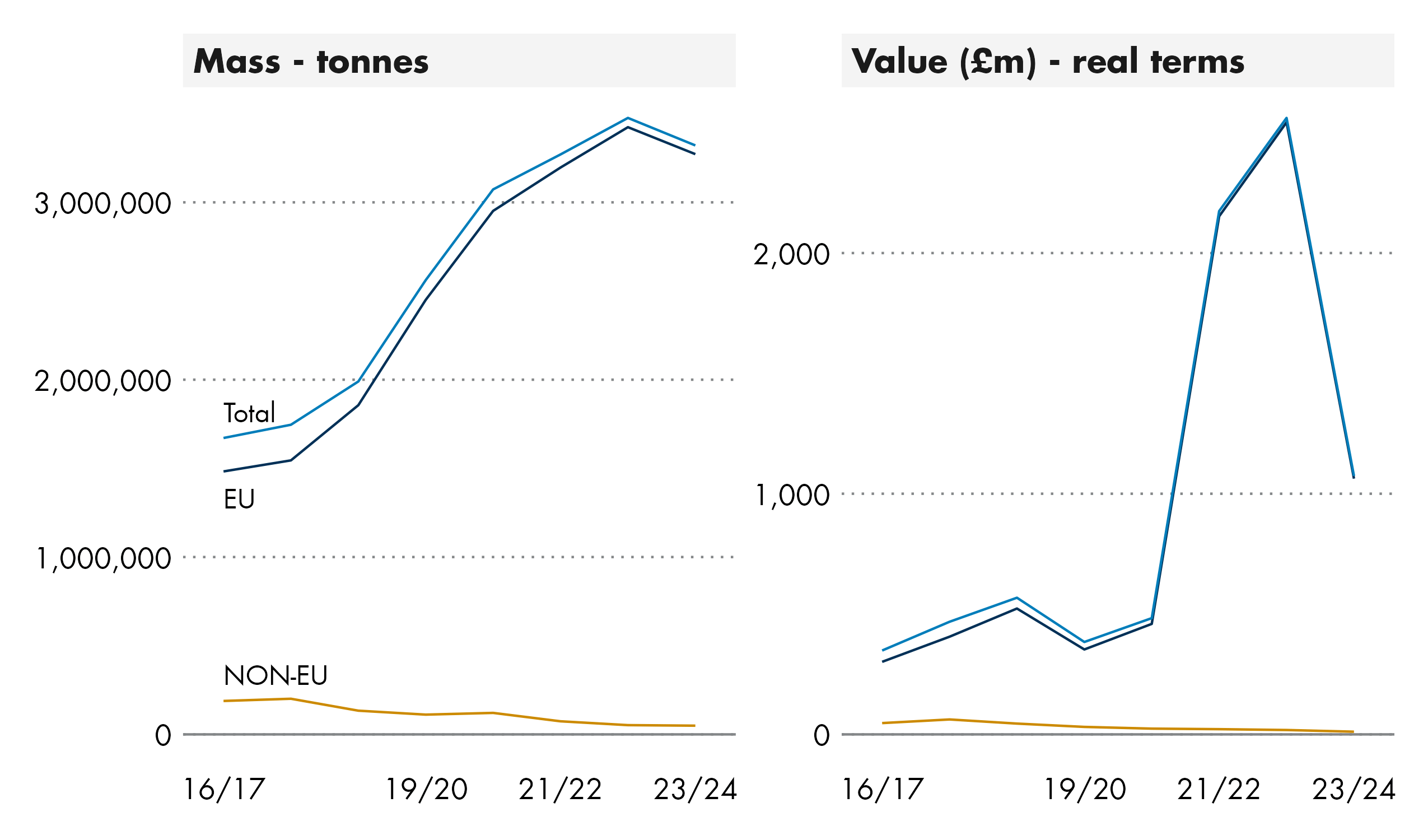

For this section when we talk about food and drink, we have combined the 'Food and live animals' and 'Beverages' classifications used in the Regional Trade Statistics. Overall, between 2016/17 and 2023/24 the value of Scotland's food and drink exports increased by £1.9 billion, or 36%. When we look at the figures in real terms, it is an increase of 7%. However, the increase has not been uniform, for example, in real terms, the 2023/24 figure was 0.2% below the pre-pandemic levels of 2019/20. Alongside being the final year before the COVID pandemic, 2019/20 was also the final full year in which the UK was a member of of the EU Single Market and Customs Union

In 2023/24 Scotland accounted for 30% of the UK's value of food and drinks exports.

Beverages exports, (mainly whisky) worth £5.1 billion and seafood, worth £1.1 billion, were Scotland's two most valuable food and drinks exports in 2023/24. Combined they accounted for 87% of all of Scotland's food and drink exports. The value of both beverages and seafood exports have increased in real terms since 2016/17, however, the increase has not been uniform and while beverages exports are slightly above pre-pandemic levels of 2019/20, seafood exports have fallen by 8% when compared to 2019/20.

The value of exports of 'live animals' has seen the largest percentage increase since the pre-pandemic levels (2019-20), growing by 28%. While exports of 'Vegetables & fruit', 'Coffee, tea, cocoa and spices' and 'Sugar, sugar preparations & honey' have all seen significant falls since 2019/20.

The following table provides a breakdown of the value of food and drink exports by commodity grouping in 2016/17 prices.

| Commodity group | 2016/17 | 2019/20 - real | 2023/24 - real | Change: 2016/17 to 2019/20 | Change: 2016/17 to 2023/24 | Change: 2019/20 to 2023/24 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beverages | 3,803 | 4,067 | 4,096 | 7% | 8% | 1% |

| Seafood | 822 | 928 | 857 | 13% | 4% | -8% |

| Cereals & cereal preparations | 169 | 166 | 192 | -2% | 13% | 15% |

| Feeding stuff for animals | 163 | 181 | 176 | 11% | 8% | -3% |

| Meat & meat preparations | 96 | 100 | 114 | 4% | 19% | 14% |

| Live animals | 56 | 49 | 63 | -13% | 12% | 28% |

| Miscellaneous edible products & preparations | 37 | 48 | 59 | 29% | 60% | 24% |

| Vegetables & fruit | 64 | 75 | 57 | 18% | -10% | -24% |

| Dairy products & birds' eggs | 44 | 49 | 47 | 9% | 5% | -4% |

| Coffee, tea, cocoa and spices | 18 | 19 | 13 | 6% | -23% | -28% |

| Sugar, sugar preparations & honey | 21 | 19 | 13 | -10% | -38% | -32% |

As discussed above, food and drink exports have increased by 7% in real terms when comparing the years 2016/17 and 2023/24. However looking at the breakdown of value of food and drink exports by EU and non-EU destination it shows:

EU: The real terms value of exports increased by 2%, between 2016/17 and 2023/24. However this increase has not been uniform, in 2023/24 the real terms value of exports was 1% below pre-pandemic levels of 2019/20.

Non- EU: The real terms value of exports increased by 11%, between 2016/17 and 2023/24 and 1% above the pre-pandemic figures of 2019/20.

Looking at how the mass of food and drink exports has changed it shows that overall it has increased by 1% between 2016/17 and 2023/24, but it is 6% below pre-pandemic levels of 2019/20. When we look at the breakdown of value by EU and non-EU destination we can see:

EU: The mass of exports has fallen by 10% between 2016/17 and 2023/24. The 2023/24 mass of food and drink exports is 10% below the pre-pandemic figure for 2019/20.

Non- EU: The mass of exports has increased by 15% between 2016/17 and 2023/24 but is 0.4% below the pre-pandemic figure for 2019/20.

As highlighted above, alongside being the final year before the impact of COVID was felt, 2019/20 was also the final full year during which the UK was a member of the EU SIngle Market. Perishable goods exports are at particular risk when there are trade disruptions such as those which followed EU exit. For example the new requirements for checks on Scottish exports to the EU and the need for Export Health Certificates for animal and plant based goods are particular issues for perishable items with shorter shelf lives.

In a written submission to the CEEAC, Scotland Food and Drink highlighted the impact of new procedures on Scottish exporters to the EU following EU exit:

The TCA's provision for zero tariffs and quotas prevented immediate and significant trade barriers with the EU. However, the introduction of non-tariff barriers, such as customs checks and sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) controls, has created logistical challenges and increased costs for Scottish exporters. The complexity of these new requirements has been particularly challenging for smaller producers, who are vital to the diversity and success of Scotland's food and drink sector

Scotland Food and Drink. (2024, March 27). Submission to the Constitution, Europe, External Affairs and Culture Committee about the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA).. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/-/media/files/committees/constitution-europe-external-affairs-and-culture-committee/tca-scotland-food-and-drink.pdf [accessed 26 July 2024]

Scotland Food and Drink set out that the main impact had been on perishable goods such as seafood and meat and dairy which now faced delays and increased costs.

Quality Meat Scotland provided written evidence to CEEAC setting out the experience of Scottish meat exporters to the EU following EU exit:

The introduction of EU border controls on imports of red meat from Great Britain at the beginning of 2021 has had a lasting impact on export activity. Although HMRC trade statistics suggest that overall UK export volumes of beef and lamb to the EU have rebuilt to similar levels to the five-year average from before the Ccovid-19 pandemic, with beef volumes 4.2% lower and lamb shipments down just 0.2% compared to the 2015-19 average for the January to August period, the structure of trade has changed. For beef (HS 0201 & 0202), bone-in products have increased in share at the expense of boneless cuts, while for sheepmeat (HS0204), carcasses have increased their dominance of export volumes from 67.5% in 2015-19 to around 87% in 2023.

Quality Meat Scotland . (2024, June 6). Review of EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreemen. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/-/media/files/committees/constitution-europe-external-affairs-and-culture-committee/tca-qms.pdf [accessed 26 July 2024]

Quality Meat Scotland also highlighted that the challenges have been greater for smaller exporters with larger companies showing more resilience and better able to adapt:

This reflects the greater ability for larger exporters to consolidate a range of products from multiple sites into single export deliveries and to absorb the additional cost and time required for filling out paperwork. For smaller exporters sending smaller loads which need to be grouped with those of other firms, exports continue to face much greater disruption and cost, and some smaller firms have exported significantly less, or even stopped exports altogether due to the level of cost becoming prohibitive.

Quality Meat Scotland . (2024, June 6). Review of EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreemen. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.scot/-/media/files/committees/constitution-europe-external-affairs-and-culture-committee/tca-qms.pdf [accessed 26 July 2024]

Quality Meat Scotland also highlighted a significant effect of EU exit in terms of the type of produce Scottish meat exporters can send to the EU with the export of mince and meat preparations such as sausages prohibited due to the EU's sanitary and phytosanitary rules. This change in type of produce which can be exported to the EU following EU exit is exemplified by the 28% increase in the export of live animals from Scotland to the EU between 2019/20 and 2023/24. This change means that more of the processing of Scottish meat products will be taking place in the EU before being shipped to its final destination.

Seafood

As highlighted in the food and drink case study, perishable goods have been particularly hit by EU exit with new checks and paperwork required on all Scottish animal and plant exports to the EU. The Scottish seafood industry has been significantly hit by the new non-tariff barriers.

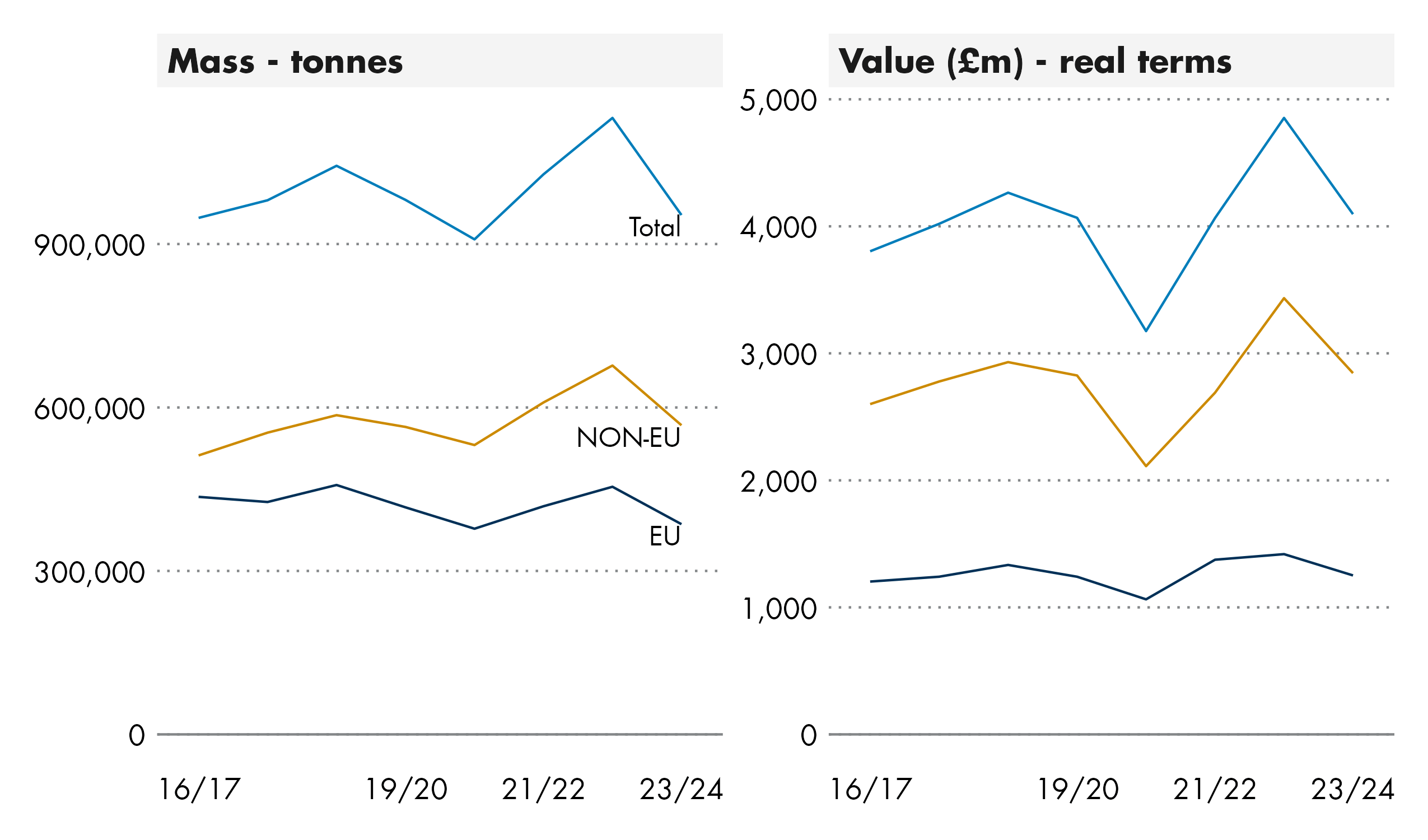

As the table below shows, between 2019/20 and 2023/24 the value of total seafood exports fell by 8% in real terms and the weight of exports fell by 2%. Of these exports, the value of exports to the EU fell by 5% in real terms with the mass exported falling by 4%. Alongside this, the value of exports to non-EU destinations also fell by 17% in real terms but the mass of exports increased by 7% suggesting the price for Scottish seafood in non-EU countries fell dramatically between 2019 and 2023. In 2023/24 Scotland accounted for 61% of the total value of UK Seafood exports.

By 2023/24, France accounted for 58% of the total value of Scotland's seafood exports and 72% of the value of Scotland's total EU seafood exports. The United States accounted for 8% of the total value of Scotland's seafood exports and 40% of the value of seafood exports to non-EU destinations.

What is the state of seafood exports to the EU?

In 2019/20 the value of seafood exports to the EU was £765 million, this has increased to £866 million by 2023/24. However, when we look at this in real terms, the value has fallen by £34 million or 5%.

In 2023/24 the EU accounted for 80% of the total value of Scotland's seafood exports compared to 79% in 2019/20.

The mass of seafood exports to the EU has fallen by 4% between 2019/20 and 2023/24.

In 2023/24 the EU accounted for 78% of the total mass of seafood exports compared to 80% in 201920.

As discussed above, France accounted for the majority of Scottish seafood exports to the EU in 2023/24. While France has seen a significant increase in the value of exports, other valuable markets have seen sharp declines between 2019 and 2023.

In 2019/20, Spain, Italy, Ireland and Germany made up the rest of the top five most valuable destinations for Scotland's seafood exports to the EU and accounted for 29% of the total value of seafood exports to the EU. In 2023/24 the same four countries accounted for 11%.

Between 2019/20 and 2023/24 the real term value of exports fell by:

60% to Spain.

70% to Italy.

51% to Ireland.

74% to Germany.

The top destinations based on value in 2023/24 were France, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain and Ireland.

The Netherlands increased by 170%.

Poland increased by 93%.

In correspondence with SPICe, Seafood Scotland, the national trade and marketing body for the industry in Scotland, explained that the main reasons for the variations in Scotland's seafood exports to the EU were socio economic, and related to four issues:

The majority of exports redirected to Western Europe transport hubs

Departure from the European Union and the subsequent logistical issues redirected exports to the largest European trade hubs such as France and the Netherlands to the detriment of smaller entry ports. Exports are monitored up to their landing in the EU and their intra-EU destination is often unknown; this means that while the value of exports have grown to France and the Netherlands, products could travel further to other European markets.

Local investments in fish processing in Eastern Europe

For more than a decade, Poland’s fish processing sector has gone through a considerable transformation and has become one of the largest in Europe thanks in part to a low-cost workforce, and easy access to other EU markets from a transport and regulatory perspective. Lithuania is also benefiting from a growing interest in its processing industry. These factors have led to a growth in Scottish seafood exports going to Poland for processing before being circulated more widely across the European Union.

Tourism rebound

Post-Covid intra-EU tourism rebound also partially drove hospitality industry demand for products such as seafood from Scotland, especially as tourism numbers got closer to pre-pandemic levels.

Inflation

In the UK, inflation during 2023 impacted negatively on UK demand for seafood products, which are usually more expensive than other food options. This meant more seafood from Scotland was exported, for example to the EU.

In written evidence to the CEEAC, Seafood Scotland described the nature of post-EU exit trade with the EU as sub-optimal:

Trade in seafood between the EU and UK is manageable but sub-optimal at present. There are a number of additional trade barriers as a result of EU exit which hampered trade significantly in the early stages and which still represent costs and challenges for the sector, albeit these have reduced over time.